User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Considerations for CAM use

I thoroughly enjoyed the article on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for depression (“CAM for your depressed patient: 6 recommended options,” Current Psychiatry, October 2009) and have seen patients benefit from these treatments. I wish the authors had included information about the use of valerian root for anxiety, as this is common among some CAM users.

I think our use or discussion of CAM can show our patients we are flexible and will consider various treatments. I believe if you dismiss all CAM treatments as not as effective as prescription medications—which may be true—you will lose patients. We know how popular CAM is with the American public, despite lack of evidence and poor oversight.

In depression treatment, exercise is as effective as sertraline in some studies,1,2 but I would think the high dropout rate for exercise would make sertraline more likely to be effective in the long run. In 1 study, participants received a phone call if they missed an exercise session. This doesn’t mimic real life at all. Also St. John’s wort is administered 300 mg tid, while many antidepressants are once a day. Efficacy aside, we can guess that compliance with a medication taken 3 times a day will be less than 1 taken once daily.

I believe we need to examine our patients’ thoughts about CAM vs traditional treatment. Do they feel CAM is safer because it is natural? Do they feel less stigma if they use CAM? What are their “automatic thoughts” about this?

I disagree with the conclusion that bibliotherapy can’t hurt. Bibliotherapy does have a cost: the cost of the book, the time spent reading it, and minimal benefit. There are people making millions of dollars on self-help books that may be having little, if any, impact on our patients’ lives.

Corey Yilmaz, MD

Southwest Behavioral Health Rural Services

Tolleson, AZ

References

1. Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2349-2356.

2. Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):633-638.

Dr. Saeed responds

Despite the common belief that valerian root is effective in reducing stress and anxiety, it has not been tested for depressive disorders and is not supported by studies on anxiety disorders. Our paper did not review CAM treatments for anxiety disorders, so we did not point out that a recent Cochrane review1 of valerian for anxiety disorders included only 1 randomized controlled trial2 and found no differences between valerian and placebo.

We also agree that treatment discontinuation is a serious problem, but this is a universal concern for treating many chronic disorders. There is evidence that patient reports of treatment adherence can be unreliable. Research has shown that periodic monitoring,3 even by automated systems, can maintain compliance longer.

We disagree with Dr. Yilmaz’ comments about bibliotherapy. A meta-analysis of 29 bibliotherapy studies found bibliotherapy using cognitive and behavioral techniques superior to wait-list comparison groups.4 We feel there is ample evidence supporting bibliotherapy as a low-risk, low-cost alternative or complementary treatment for mild-to-moderate depressive disorder.

Sy Atezaz Saeed, MD

Department of psychiatric medicine

Brody School of Medicine at

East Carolina University

1. Miyasaka LS, Atallah AN, Soares BG. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004515.-

2. Andreatini R, Sartori VA, Seabra ML, et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Phytother Res. 2002;16(7):650-654.

3. Gensichen J, von Korff M, Peitz M, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(6):369-378.

4. Gregory RJ, Schwer Canning S, Lee TW, et al. Cognitive bibliotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(3):275-280.

I thoroughly enjoyed the article on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for depression (“CAM for your depressed patient: 6 recommended options,” Current Psychiatry, October 2009) and have seen patients benefit from these treatments. I wish the authors had included information about the use of valerian root for anxiety, as this is common among some CAM users.

I think our use or discussion of CAM can show our patients we are flexible and will consider various treatments. I believe if you dismiss all CAM treatments as not as effective as prescription medications—which may be true—you will lose patients. We know how popular CAM is with the American public, despite lack of evidence and poor oversight.

In depression treatment, exercise is as effective as sertraline in some studies,1,2 but I would think the high dropout rate for exercise would make sertraline more likely to be effective in the long run. In 1 study, participants received a phone call if they missed an exercise session. This doesn’t mimic real life at all. Also St. John’s wort is administered 300 mg tid, while many antidepressants are once a day. Efficacy aside, we can guess that compliance with a medication taken 3 times a day will be less than 1 taken once daily.

I believe we need to examine our patients’ thoughts about CAM vs traditional treatment. Do they feel CAM is safer because it is natural? Do they feel less stigma if they use CAM? What are their “automatic thoughts” about this?

I disagree with the conclusion that bibliotherapy can’t hurt. Bibliotherapy does have a cost: the cost of the book, the time spent reading it, and minimal benefit. There are people making millions of dollars on self-help books that may be having little, if any, impact on our patients’ lives.

Corey Yilmaz, MD

Southwest Behavioral Health Rural Services

Tolleson, AZ

References

1. Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2349-2356.

2. Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):633-638.

Dr. Saeed responds

Despite the common belief that valerian root is effective in reducing stress and anxiety, it has not been tested for depressive disorders and is not supported by studies on anxiety disorders. Our paper did not review CAM treatments for anxiety disorders, so we did not point out that a recent Cochrane review1 of valerian for anxiety disorders included only 1 randomized controlled trial2 and found no differences between valerian and placebo.

We also agree that treatment discontinuation is a serious problem, but this is a universal concern for treating many chronic disorders. There is evidence that patient reports of treatment adherence can be unreliable. Research has shown that periodic monitoring,3 even by automated systems, can maintain compliance longer.

We disagree with Dr. Yilmaz’ comments about bibliotherapy. A meta-analysis of 29 bibliotherapy studies found bibliotherapy using cognitive and behavioral techniques superior to wait-list comparison groups.4 We feel there is ample evidence supporting bibliotherapy as a low-risk, low-cost alternative or complementary treatment for mild-to-moderate depressive disorder.

Sy Atezaz Saeed, MD

Department of psychiatric medicine

Brody School of Medicine at

East Carolina University

I thoroughly enjoyed the article on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for depression (“CAM for your depressed patient: 6 recommended options,” Current Psychiatry, October 2009) and have seen patients benefit from these treatments. I wish the authors had included information about the use of valerian root for anxiety, as this is common among some CAM users.

I think our use or discussion of CAM can show our patients we are flexible and will consider various treatments. I believe if you dismiss all CAM treatments as not as effective as prescription medications—which may be true—you will lose patients. We know how popular CAM is with the American public, despite lack of evidence and poor oversight.

In depression treatment, exercise is as effective as sertraline in some studies,1,2 but I would think the high dropout rate for exercise would make sertraline more likely to be effective in the long run. In 1 study, participants received a phone call if they missed an exercise session. This doesn’t mimic real life at all. Also St. John’s wort is administered 300 mg tid, while many antidepressants are once a day. Efficacy aside, we can guess that compliance with a medication taken 3 times a day will be less than 1 taken once daily.

I believe we need to examine our patients’ thoughts about CAM vs traditional treatment. Do they feel CAM is safer because it is natural? Do they feel less stigma if they use CAM? What are their “automatic thoughts” about this?

I disagree with the conclusion that bibliotherapy can’t hurt. Bibliotherapy does have a cost: the cost of the book, the time spent reading it, and minimal benefit. There are people making millions of dollars on self-help books that may be having little, if any, impact on our patients’ lives.

Corey Yilmaz, MD

Southwest Behavioral Health Rural Services

Tolleson, AZ

References

1. Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2349-2356.

2. Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):633-638.

Dr. Saeed responds

Despite the common belief that valerian root is effective in reducing stress and anxiety, it has not been tested for depressive disorders and is not supported by studies on anxiety disorders. Our paper did not review CAM treatments for anxiety disorders, so we did not point out that a recent Cochrane review1 of valerian for anxiety disorders included only 1 randomized controlled trial2 and found no differences between valerian and placebo.

We also agree that treatment discontinuation is a serious problem, but this is a universal concern for treating many chronic disorders. There is evidence that patient reports of treatment adherence can be unreliable. Research has shown that periodic monitoring,3 even by automated systems, can maintain compliance longer.

We disagree with Dr. Yilmaz’ comments about bibliotherapy. A meta-analysis of 29 bibliotherapy studies found bibliotherapy using cognitive and behavioral techniques superior to wait-list comparison groups.4 We feel there is ample evidence supporting bibliotherapy as a low-risk, low-cost alternative or complementary treatment for mild-to-moderate depressive disorder.

Sy Atezaz Saeed, MD

Department of psychiatric medicine

Brody School of Medicine at

East Carolina University

1. Miyasaka LS, Atallah AN, Soares BG. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004515.-

2. Andreatini R, Sartori VA, Seabra ML, et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Phytother Res. 2002;16(7):650-654.

3. Gensichen J, von Korff M, Peitz M, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(6):369-378.

4. Gregory RJ, Schwer Canning S, Lee TW, et al. Cognitive bibliotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(3):275-280.

1. Miyasaka LS, Atallah AN, Soares BG. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004515.-

2. Andreatini R, Sartori VA, Seabra ML, et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Phytother Res. 2002;16(7):650-654.

3. Gensichen J, von Korff M, Peitz M, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(6):369-378.

4. Gregory RJ, Schwer Canning S, Lee TW, et al. Cognitive bibliotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(3):275-280.

Are psychiatrists more evidence-based than psychologists?

A recent psychology journal article lambasted clinical psychologists for not using evidence-based psychotherapeutic modalities when treating their patients.1 The authors pointed out that many psychologists were ignoring efficacious and cost-effective psychotherapy interventions or using approaches that lack sufficient evidence.

An accompanying editorial2 was equally scathing—calling the disconnect between clinical psychology practice and advances in psychological science “an unconscionable embarrassment”—and warned that the profession “will increasingly discredit and marginalize itself” if it persists in neglecting evidence-based practices. The author quoted the respected late psychologist Paul Meehl as saying “most clinical psychologists select their methods like kids make choices in a candy store” and added that the comment is heart-breaking because it is true. A Newsweek column—“Ignoring the evidence: Why do psychologists reject science?”3—elicited little agreement and mostly howls of protest from psychologists.

So, are psychiatrists more evidence-based than psychologists? We manage patients who are more severely ill than those seen by psychologists, and we use both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to stabilize neurobiologic disorders. Because only 15% of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic categories have an evidence-based, FDA-approved drug treatment,4 we practice by necessity a substantial amount of non-evidenced-based (off-label) pharmacotherapy. But what about psychiatric conditions for which evidence-based treatments exist? Do studies show that we follow the evidence?

Psychiatrists’ track record

The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team5 assessed how the treatment of 719 patients with schizophrenia conformed to 12 evidence-based treatment recommendations. Overall, <50% of treatments conformed to the recommendations, with higher conformance rates seen for rural than urban patients and for Caucasian patients than minorities.

A study using data from the National Comorbidity Survey6 found that only 40% of respondents with serious psychiatric disorders had received treatment in the previous 12 months, and only 15% received care considered at least minimally adequate. Four predictors of not receiving minimally adequate treatment included being a young adult or African-American, living in the South, suffering from a psychotic disorder, and being treated by physicians other than psychiatrists.

Finally, a recent survey of psychiatrists’ adherence to evidence-based antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia7 showed: 1) mid-career psychiatrists more adherent than early or late-career counterparts; 2) male psychiatrists more adherent than female; 3) those carrying a large workload of schizophrenia patients more likely to adhere to scientific literature.

Who is evidence-based: A self-assessment

Are YOU an evidence-based psychiatric clinician? Ask yourself:

- Can I correctly define evidence-based psychopharmacology?

- Do I regularly read systematic reviews (such as Cochrane reviews) or meta-analytic articles about the medications I prescribe?

- Can I cite at least 1 randomized controlled trial supporting my use of each medication I prescribe?

- Do I know what “effect size” means?

- Do I usually or sometimes select a psychotherapeutic agent based on number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH)?

- Do I routinely use clinical rating scales employed in FDA controlled trials to quantify the severity of my patients’ illness and determine whether they achieve “remission” or just a “response”?

Psychiatric practice should be evidence-based and continuously adapt to incorporate the wealth of evidence being generated. Psychiatrists who do not keep up with the evidence run the risk of practicing psychopharmacology of the previous millennium.

1. Baker TB, McFall RM, Shoham V. Current status and future prospects of clinical psychology: toward a scientifically principled approach to mental and behavioral health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2):67-103. Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

2. Mischel W. Connecting clinical practice with scientific progress. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2). Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

3. Begley S. Ignoring the evidence: why do psychologists reject science? Newsweek. October 12, 2009. Available at: http://www.newsweek.com/id/216506. Accessed November 10, 2009.

4. Devalupalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):11-20.

6. Wang PS, Delmer O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):92-98.

7. Young GJ, Mohr DC, Meterko M, et al. Psychiatrists’ self-reported adherence to evidence-based prescribing practices in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):130-132.

A recent psychology journal article lambasted clinical psychologists for not using evidence-based psychotherapeutic modalities when treating their patients.1 The authors pointed out that many psychologists were ignoring efficacious and cost-effective psychotherapy interventions or using approaches that lack sufficient evidence.

An accompanying editorial2 was equally scathing—calling the disconnect between clinical psychology practice and advances in psychological science “an unconscionable embarrassment”—and warned that the profession “will increasingly discredit and marginalize itself” if it persists in neglecting evidence-based practices. The author quoted the respected late psychologist Paul Meehl as saying “most clinical psychologists select their methods like kids make choices in a candy store” and added that the comment is heart-breaking because it is true. A Newsweek column—“Ignoring the evidence: Why do psychologists reject science?”3—elicited little agreement and mostly howls of protest from psychologists.

So, are psychiatrists more evidence-based than psychologists? We manage patients who are more severely ill than those seen by psychologists, and we use both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to stabilize neurobiologic disorders. Because only 15% of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic categories have an evidence-based, FDA-approved drug treatment,4 we practice by necessity a substantial amount of non-evidenced-based (off-label) pharmacotherapy. But what about psychiatric conditions for which evidence-based treatments exist? Do studies show that we follow the evidence?

Psychiatrists’ track record

The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team5 assessed how the treatment of 719 patients with schizophrenia conformed to 12 evidence-based treatment recommendations. Overall, <50% of treatments conformed to the recommendations, with higher conformance rates seen for rural than urban patients and for Caucasian patients than minorities.

A study using data from the National Comorbidity Survey6 found that only 40% of respondents with serious psychiatric disorders had received treatment in the previous 12 months, and only 15% received care considered at least minimally adequate. Four predictors of not receiving minimally adequate treatment included being a young adult or African-American, living in the South, suffering from a psychotic disorder, and being treated by physicians other than psychiatrists.

Finally, a recent survey of psychiatrists’ adherence to evidence-based antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia7 showed: 1) mid-career psychiatrists more adherent than early or late-career counterparts; 2) male psychiatrists more adherent than female; 3) those carrying a large workload of schizophrenia patients more likely to adhere to scientific literature.

Who is evidence-based: A self-assessment

Are YOU an evidence-based psychiatric clinician? Ask yourself:

- Can I correctly define evidence-based psychopharmacology?

- Do I regularly read systematic reviews (such as Cochrane reviews) or meta-analytic articles about the medications I prescribe?

- Can I cite at least 1 randomized controlled trial supporting my use of each medication I prescribe?

- Do I know what “effect size” means?

- Do I usually or sometimes select a psychotherapeutic agent based on number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH)?

- Do I routinely use clinical rating scales employed in FDA controlled trials to quantify the severity of my patients’ illness and determine whether they achieve “remission” or just a “response”?

Psychiatric practice should be evidence-based and continuously adapt to incorporate the wealth of evidence being generated. Psychiatrists who do not keep up with the evidence run the risk of practicing psychopharmacology of the previous millennium.

A recent psychology journal article lambasted clinical psychologists for not using evidence-based psychotherapeutic modalities when treating their patients.1 The authors pointed out that many psychologists were ignoring efficacious and cost-effective psychotherapy interventions or using approaches that lack sufficient evidence.

An accompanying editorial2 was equally scathing—calling the disconnect between clinical psychology practice and advances in psychological science “an unconscionable embarrassment”—and warned that the profession “will increasingly discredit and marginalize itself” if it persists in neglecting evidence-based practices. The author quoted the respected late psychologist Paul Meehl as saying “most clinical psychologists select their methods like kids make choices in a candy store” and added that the comment is heart-breaking because it is true. A Newsweek column—“Ignoring the evidence: Why do psychologists reject science?”3—elicited little agreement and mostly howls of protest from psychologists.

So, are psychiatrists more evidence-based than psychologists? We manage patients who are more severely ill than those seen by psychologists, and we use both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to stabilize neurobiologic disorders. Because only 15% of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic categories have an evidence-based, FDA-approved drug treatment,4 we practice by necessity a substantial amount of non-evidenced-based (off-label) pharmacotherapy. But what about psychiatric conditions for which evidence-based treatments exist? Do studies show that we follow the evidence?

Psychiatrists’ track record

The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team5 assessed how the treatment of 719 patients with schizophrenia conformed to 12 evidence-based treatment recommendations. Overall, <50% of treatments conformed to the recommendations, with higher conformance rates seen for rural than urban patients and for Caucasian patients than minorities.

A study using data from the National Comorbidity Survey6 found that only 40% of respondents with serious psychiatric disorders had received treatment in the previous 12 months, and only 15% received care considered at least minimally adequate. Four predictors of not receiving minimally adequate treatment included being a young adult or African-American, living in the South, suffering from a psychotic disorder, and being treated by physicians other than psychiatrists.

Finally, a recent survey of psychiatrists’ adherence to evidence-based antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia7 showed: 1) mid-career psychiatrists more adherent than early or late-career counterparts; 2) male psychiatrists more adherent than female; 3) those carrying a large workload of schizophrenia patients more likely to adhere to scientific literature.

Who is evidence-based: A self-assessment

Are YOU an evidence-based psychiatric clinician? Ask yourself:

- Can I correctly define evidence-based psychopharmacology?

- Do I regularly read systematic reviews (such as Cochrane reviews) or meta-analytic articles about the medications I prescribe?

- Can I cite at least 1 randomized controlled trial supporting my use of each medication I prescribe?

- Do I know what “effect size” means?

- Do I usually or sometimes select a psychotherapeutic agent based on number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH)?

- Do I routinely use clinical rating scales employed in FDA controlled trials to quantify the severity of my patients’ illness and determine whether they achieve “remission” or just a “response”?

Psychiatric practice should be evidence-based and continuously adapt to incorporate the wealth of evidence being generated. Psychiatrists who do not keep up with the evidence run the risk of practicing psychopharmacology of the previous millennium.

1. Baker TB, McFall RM, Shoham V. Current status and future prospects of clinical psychology: toward a scientifically principled approach to mental and behavioral health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2):67-103. Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

2. Mischel W. Connecting clinical practice with scientific progress. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2). Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

3. Begley S. Ignoring the evidence: why do psychologists reject science? Newsweek. October 12, 2009. Available at: http://www.newsweek.com/id/216506. Accessed November 10, 2009.

4. Devalupalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):11-20.

6. Wang PS, Delmer O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):92-98.

7. Young GJ, Mohr DC, Meterko M, et al. Psychiatrists’ self-reported adherence to evidence-based prescribing practices in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):130-132.

1. Baker TB, McFall RM, Shoham V. Current status and future prospects of clinical psychology: toward a scientifically principled approach to mental and behavioral health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2):67-103. Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

2. Mischel W. Connecting clinical practice with scientific progress. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;9(2). Available at: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/inpress/baker.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2009.

3. Begley S. Ignoring the evidence: why do psychologists reject science? Newsweek. October 12, 2009. Available at: http://www.newsweek.com/id/216506. Accessed November 10, 2009.

4. Devalupalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):11-20.

6. Wang PS, Delmer O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):92-98.

7. Young GJ, Mohr DC, Meterko M, et al. Psychiatrists’ self-reported adherence to evidence-based prescribing practices in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):130-132.

The bedtime solution

CASE: Refractory depression

Ms. W, age 38, is brought to the emergency department after her son finds her unresponsive and calls 911. Suffering from worsening depression, she wrote a note telling her children goodbye, and overdosed on zolpidem from an old prescription and her daughter’s opioids. After being evaluated and medically cleared in the emergency department, Ms. W was admitted to the psychiatric unit.

Ms. W has a history of recurrent major depressive disorder that developed after she was sexually abused by a relative as a teen. She also has bulimia nervosa, alcohol dependence, and posttraumatic stress disorder. She was hospitalized twice for depression and suicidality but had not previously attempted suicide. In the mid-to-late 1990s, she had trials of paroxetine, clomipramine, lithium, and bupropion.

She was seen regularly in our outpatient psychiatry clinic for medication management and supportive psychotherapy. Since being followed in our clinic starting in early 2005, she has had the following medication trials:

- fluoxetine, citalopram, venlafaxine XR, and duloxetine for depression

- atomoxetine, buspirone, liothyronine, risperidone, and aripiprazole for antidepressant augmentation

- lorazepam, clonazepam, and gabapentin for anxiety

- zolpidem and trazodone for insomnia

- nortriptyline for migraine headache prophylaxis.

Some medications were not tolerated, primarily because of increased anxiety. Those that were tolerated were adequate trials in terms of dose titration and length. High-dose fluoxetine (80 mg/d) augmented by risperidone (0.375 to 0.5 mg/d) produced the most reliable and significant improvement.

Ms. W had 2 courses of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) totaling 30 treatments—most recently in 2007—that resulted in significant memory loss with limited benefit. Premenstrual worsening of depression and suicidality were noted. In collaboration with her gynecologist, Ms. W was treated with a 3-month trial of leuprolide to suppress her ovarian axis, which was helpful. In 2008 she underwent bilateral oophorectomy. She has not had symptoms of mood elevation or psychosis. Family history includes schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and alcoholism.

In the months before hospitalization, Ms. W had been increasingly depressed and intermittently suicidal, although she did not endorse a specific plan or intention to harm herself because she was concerned about the impact suicide would have on her children. Weight gain with risperidone had reactivated body image issues, so Ms. W stopped taking this medication 2 weeks before hospitalization. Her depression became worse, and she began using her husband’s hydrocodone/acetaminophen prescription.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of patients with major depression fail to respond to an initial antidepressant trial.1 An additional 50% of these patients will be treatment-resistant to a subsequent antidepressant.1 Patients may be progressively less likely to respond to additional medication trials.2

One of the most rapid-acting and effective treatments for unipolar and bipolar depression is sleep deprivation. Wirz-Justice et al3 found total or partial sleep deprivation during the second half of the night induced rapid depression remission. Response rates range from 40% to 60% over hours to days.4 Sleep deprivation also can reduce suicidality in patients with seasonal depression.5 This treatment has not been widely employed, however, because up to 80% of patients who undergo sleep deprivation experience rapid and significant depressive relapse.4

Sleep deprivation usually is well tolerated. Potential side effects include:

- headache

- gastrointestinal upset

- fatigue

- cognitive impairment.

Less often, patients report worsening of depressive symptoms and, rarely, suicidal ideation or psychosis.4 Mania or hypomania are potential complications of sleep loss for patients with bipolar or unipolar depression. In a review, Oliwenstein6 suggested that rates of total sleep deprivation-induced mania are likely to be similar to or less than those reported for antidepressants. Because sleep deprivation can induce seizures, this therapy is contraindicated for patients with epilepsy or those at risk for seizures.4

Researchers have successfully explored strategies to reduce the rate of depressive relapse after sleep deprivation, including coadministering light therapy, antidepressants, lithium (particularly for bipolar depression), and sleep-phase advance.4 Sleep-phase advance involves shifting the sleep-wake schedule to a very early sleep time and wake-up time (such as 5 PM to midnight) for 1 day, and then pushing back this schedule by 1 or 2 hours each day until the patient is returned to a “normal” sleep schedule (such as 10 PM to 5 AM). Researchers have demonstrated that sleep-phase advance can have antidepressant effects.7

TREATMENT: Sleep manipulation

Ms. W is continued on fluoxetine, 80 mg/d. We opt for a trial of partial sleep deprivation and sleep-phase advance for Ms. W because of the severity of her depression, her multiple ineffective or poorly tolerated medication trials, and limited benefit from ECT. This treatment involves instituting partial sleep deprivation the first night and subsequently advancing her sleep phase over the next several days (Table 1).

Although she is sleepy the morning after partial sleep deprivation, Ms. W reports a marked improvement in her mood, decline in hopelessness, and absence of suicidal ideation. She continues the sleep-phase advance protocol for the next 3 nights and participates in cognitive-behavioral therapy groups and ward activities. Psychiatric unit staff support her continued wakefulness during sleep manipulation. Because Ms. W had previously responded to antidepressant augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic we add aripiprazole and titrate the dosage to 7.5 mg/d. We also continue fluoxetine, 80 mg/d, and add trazodone, 100 mg at bedtime, and hydroxyzine, 25 mg as needed.

Table 1

Ms. W’s chronotherapy protocol: Hours permitted for sleep*

| Day number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Sleep deprivation | 9 PM to2 AM | ||||

| Sleep-phase advance | 5 PM to midnight | 7 PM to 2 AM | 9 PM to 4 AM | 10 PM to 5 AM | |

| *Treatment was implemented while Ms. W was hospitalized | |||||

The authors’ observations

Chronotherapy incorporates manipulations of the sleep/wake cycle such as sleep deprivation and dark or light therapy. It may use combinations of interventions to generate and sustain a response in patients with depression. In a 4-week pilot study, Moscovici et al8 employed a regimen of late partial sleep deprivation, light, and sleep-phase advance to generate and maintain an anti depressant response in 12 patients. Benedetti et al9 used a similar regimen plus lithium to successfully treat bipolar depression and sleep-phase advance to continue that response in 50% of patients for 3 months.

Circadian rhythms affect the function of serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine, and dopamine.9,10 In a manner similar to antidepressant medications, sleep deprivation may up-regulate or otherwise alter these neurotransmitters’ function. In animals, sleep deprivation increases serotonin function.11 Several hypothetical mechanisms of action for sleep deprivation and other types of chronotherapies have been suggested (Table 2).11-14

Chronotherapies may affect function in brain pathways, as demonstrated by neuroimaging with positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Depression has been associated with increased or decreased brain activity measured by PET or fMRI in regions of the limbic cortex (cingulate and anterior cingulate) and frontal cortex.12

Wu et al13 examined patients treated for depression with medication and total sleep deprivation therapy. Response to treatment was associated with increased function in the cingulate, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex as measured by PET. In contrast, mood improvement was associated with reduced baseline activity in the left medial prefrontal cortex, left frontal pole, and right lateral prefrontal cortex.

Researchers have noted the convergence of sleep-wake rhythms and abnormalities seen in depression and the subsequent link with improved sleep-wake cycles related to depression remission. Bunney and Potkin14 note the powerful effect of zeitgebers—environmental agents that reset the body’s internal clock. They suggested that sleep deprivation may affect the function of “master clock” genes involved in controlling the biological clock. These effects on the suprachiasmatic nucleus hypothalamic pacemaker may improve mood by altering control of genetic expression through chromatin remodeling of this master clock circuit.

Certain factors may increase the likelihood that a patient may respond to chronotherapy (Table 3).9,15-17

Table 2

Sleep deprivation for depression: Possible mechanisms

| Mechanism | Components |

|---|---|

| Alterations to neurotransmitter function | Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine11 |

| Alterations to endogenous circadian pacemaker function | Increased gene expression14 |

| Changes in perfusion/activity of brain regions | Anterior cingulate, frontal cortex regions12,13 |

Table 3

Factors that suggest a patient might respond to chronotherapy

| Diurnal mood variation15 |

| Endogenous depression including insomnia and anorexia16 |

| Abnormal dexamethasone suppression17 |

| High motivation for treatment |

| Bipolar depression (possibly)9 |

OUTCOME: Lasting improvement

Ms. W’s mood improvement is sustained during her week-long hospitalization. At discharge she is hopeful about the future and does not have thoughts of suicide.

At subsequent outpatient visits up to 4 months after discharge, her depressive symptoms remain improved. Patient Health Questionnaire scores indicate mild depression, but Ms. W is not suicidal. She maintains a sleep schedule of 10 PM to 6:30 AM and undergoes 10,000 lux bright light therapy, which she began shortly after discharge, for 30 minutes every morning. She works more productively in psychotherapy, focusing on her eating disorder and anxiety.

Related resource

- Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009; 66(3): 298-301.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydrocodone/APAP • Vicodin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Leuprolide • Lupron

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. AHCPR Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline number 5. Depression in primary care. Volume 2: Treatment of major depression. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. AHCPR publication 93-0550.

2. Fava M, Rush JA, Wisniewski SR, et al. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1161-1172.

3. Wirz-Justice A, Benedetti F, Berger M. Chronotherapeutics (light and wake therapy) in affective disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(7):939-944.

4. Giedke H, Schwärzler F. Therapeutic use of sleep deprivation in depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(5):361-377.

5. Lam RW, Tam EM, Shiah IS, et al. Effects of light therapy on suicidal ideation in patients with winter depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(1):30-32.

6. Oliwenstein L. Lifting moods by losing sleep: an adjunct therapy for treating depression. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2006;12(2):66-70.

7. Wehr TA, Wirz-Justice A, Goodwin FK, et al. Phase advance of the circadian sleep-wake cycle as an antidepressant. Science. 1979;206(4419):710-713.

8. Moscovici L, Kotler M. A multistage chronobiologic intervention for the treatment of depression: a pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):201-217.

9. Benedetti F, Colombo C, Barbini B, et al. Morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;62(3):221-223.

10. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, et al. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(6):509-522.

11. Lopez-Rodriguez F, Wilson CL, Maidment NT, et al. Total sleep deprivation increases extracellular serotonin in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2003;121(2):523-530.

12. Mayberg HS. Defining the neural circuitry of depression: toward a new nosology with therapeutic implications. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):729-730.

13. Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, et al. Sleep deprivation PET correlations of Hamilton symptom improvement ratings with changes in relative glucose metabolism in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):181-186.

14. Bunney JN, Potkin SG. Circadian abnormalities, molecular clock genes and chronobiological treatments in depression. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:23-32.

15. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Lucca A, et al. Sleep deprivation hastens the antidepressant action of fluoxetine. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247(2):100-103.

16. Vogel GW, Thurmond A, Gibbons P, et al. REM sleep reduction effects on depression syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(6):765-777.

17. King D, Dowdy S, Jack R, et al. The dexamethasone suppression test as a predictor of sleep deprivation antidepressant effect. Psychiatry Res. 1982;7(1):93-99.

CASE: Refractory depression

Ms. W, age 38, is brought to the emergency department after her son finds her unresponsive and calls 911. Suffering from worsening depression, she wrote a note telling her children goodbye, and overdosed on zolpidem from an old prescription and her daughter’s opioids. After being evaluated and medically cleared in the emergency department, Ms. W was admitted to the psychiatric unit.

Ms. W has a history of recurrent major depressive disorder that developed after she was sexually abused by a relative as a teen. She also has bulimia nervosa, alcohol dependence, and posttraumatic stress disorder. She was hospitalized twice for depression and suicidality but had not previously attempted suicide. In the mid-to-late 1990s, she had trials of paroxetine, clomipramine, lithium, and bupropion.

She was seen regularly in our outpatient psychiatry clinic for medication management and supportive psychotherapy. Since being followed in our clinic starting in early 2005, she has had the following medication trials:

- fluoxetine, citalopram, venlafaxine XR, and duloxetine for depression

- atomoxetine, buspirone, liothyronine, risperidone, and aripiprazole for antidepressant augmentation

- lorazepam, clonazepam, and gabapentin for anxiety

- zolpidem and trazodone for insomnia

- nortriptyline for migraine headache prophylaxis.

Some medications were not tolerated, primarily because of increased anxiety. Those that were tolerated were adequate trials in terms of dose titration and length. High-dose fluoxetine (80 mg/d) augmented by risperidone (0.375 to 0.5 mg/d) produced the most reliable and significant improvement.

Ms. W had 2 courses of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) totaling 30 treatments—most recently in 2007—that resulted in significant memory loss with limited benefit. Premenstrual worsening of depression and suicidality were noted. In collaboration with her gynecologist, Ms. W was treated with a 3-month trial of leuprolide to suppress her ovarian axis, which was helpful. In 2008 she underwent bilateral oophorectomy. She has not had symptoms of mood elevation or psychosis. Family history includes schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and alcoholism.

In the months before hospitalization, Ms. W had been increasingly depressed and intermittently suicidal, although she did not endorse a specific plan or intention to harm herself because she was concerned about the impact suicide would have on her children. Weight gain with risperidone had reactivated body image issues, so Ms. W stopped taking this medication 2 weeks before hospitalization. Her depression became worse, and she began using her husband’s hydrocodone/acetaminophen prescription.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of patients with major depression fail to respond to an initial antidepressant trial.1 An additional 50% of these patients will be treatment-resistant to a subsequent antidepressant.1 Patients may be progressively less likely to respond to additional medication trials.2

One of the most rapid-acting and effective treatments for unipolar and bipolar depression is sleep deprivation. Wirz-Justice et al3 found total or partial sleep deprivation during the second half of the night induced rapid depression remission. Response rates range from 40% to 60% over hours to days.4 Sleep deprivation also can reduce suicidality in patients with seasonal depression.5 This treatment has not been widely employed, however, because up to 80% of patients who undergo sleep deprivation experience rapid and significant depressive relapse.4

Sleep deprivation usually is well tolerated. Potential side effects include:

- headache

- gastrointestinal upset

- fatigue

- cognitive impairment.

Less often, patients report worsening of depressive symptoms and, rarely, suicidal ideation or psychosis.4 Mania or hypomania are potential complications of sleep loss for patients with bipolar or unipolar depression. In a review, Oliwenstein6 suggested that rates of total sleep deprivation-induced mania are likely to be similar to or less than those reported for antidepressants. Because sleep deprivation can induce seizures, this therapy is contraindicated for patients with epilepsy or those at risk for seizures.4

Researchers have successfully explored strategies to reduce the rate of depressive relapse after sleep deprivation, including coadministering light therapy, antidepressants, lithium (particularly for bipolar depression), and sleep-phase advance.4 Sleep-phase advance involves shifting the sleep-wake schedule to a very early sleep time and wake-up time (such as 5 PM to midnight) for 1 day, and then pushing back this schedule by 1 or 2 hours each day until the patient is returned to a “normal” sleep schedule (such as 10 PM to 5 AM). Researchers have demonstrated that sleep-phase advance can have antidepressant effects.7

TREATMENT: Sleep manipulation

Ms. W is continued on fluoxetine, 80 mg/d. We opt for a trial of partial sleep deprivation and sleep-phase advance for Ms. W because of the severity of her depression, her multiple ineffective or poorly tolerated medication trials, and limited benefit from ECT. This treatment involves instituting partial sleep deprivation the first night and subsequently advancing her sleep phase over the next several days (Table 1).

Although she is sleepy the morning after partial sleep deprivation, Ms. W reports a marked improvement in her mood, decline in hopelessness, and absence of suicidal ideation. She continues the sleep-phase advance protocol for the next 3 nights and participates in cognitive-behavioral therapy groups and ward activities. Psychiatric unit staff support her continued wakefulness during sleep manipulation. Because Ms. W had previously responded to antidepressant augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic we add aripiprazole and titrate the dosage to 7.5 mg/d. We also continue fluoxetine, 80 mg/d, and add trazodone, 100 mg at bedtime, and hydroxyzine, 25 mg as needed.

Table 1

Ms. W’s chronotherapy protocol: Hours permitted for sleep*

| Day number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Sleep deprivation | 9 PM to2 AM | ||||

| Sleep-phase advance | 5 PM to midnight | 7 PM to 2 AM | 9 PM to 4 AM | 10 PM to 5 AM | |

| *Treatment was implemented while Ms. W was hospitalized | |||||

The authors’ observations

Chronotherapy incorporates manipulations of the sleep/wake cycle such as sleep deprivation and dark or light therapy. It may use combinations of interventions to generate and sustain a response in patients with depression. In a 4-week pilot study, Moscovici et al8 employed a regimen of late partial sleep deprivation, light, and sleep-phase advance to generate and maintain an anti depressant response in 12 patients. Benedetti et al9 used a similar regimen plus lithium to successfully treat bipolar depression and sleep-phase advance to continue that response in 50% of patients for 3 months.

Circadian rhythms affect the function of serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine, and dopamine.9,10 In a manner similar to antidepressant medications, sleep deprivation may up-regulate or otherwise alter these neurotransmitters’ function. In animals, sleep deprivation increases serotonin function.11 Several hypothetical mechanisms of action for sleep deprivation and other types of chronotherapies have been suggested (Table 2).11-14

Chronotherapies may affect function in brain pathways, as demonstrated by neuroimaging with positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Depression has been associated with increased or decreased brain activity measured by PET or fMRI in regions of the limbic cortex (cingulate and anterior cingulate) and frontal cortex.12

Wu et al13 examined patients treated for depression with medication and total sleep deprivation therapy. Response to treatment was associated with increased function in the cingulate, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex as measured by PET. In contrast, mood improvement was associated with reduced baseline activity in the left medial prefrontal cortex, left frontal pole, and right lateral prefrontal cortex.

Researchers have noted the convergence of sleep-wake rhythms and abnormalities seen in depression and the subsequent link with improved sleep-wake cycles related to depression remission. Bunney and Potkin14 note the powerful effect of zeitgebers—environmental agents that reset the body’s internal clock. They suggested that sleep deprivation may affect the function of “master clock” genes involved in controlling the biological clock. These effects on the suprachiasmatic nucleus hypothalamic pacemaker may improve mood by altering control of genetic expression through chromatin remodeling of this master clock circuit.

Certain factors may increase the likelihood that a patient may respond to chronotherapy (Table 3).9,15-17

Table 2

Sleep deprivation for depression: Possible mechanisms

| Mechanism | Components |

|---|---|

| Alterations to neurotransmitter function | Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine11 |

| Alterations to endogenous circadian pacemaker function | Increased gene expression14 |

| Changes in perfusion/activity of brain regions | Anterior cingulate, frontal cortex regions12,13 |

Table 3

Factors that suggest a patient might respond to chronotherapy

| Diurnal mood variation15 |

| Endogenous depression including insomnia and anorexia16 |

| Abnormal dexamethasone suppression17 |

| High motivation for treatment |

| Bipolar depression (possibly)9 |

OUTCOME: Lasting improvement

Ms. W’s mood improvement is sustained during her week-long hospitalization. At discharge she is hopeful about the future and does not have thoughts of suicide.

At subsequent outpatient visits up to 4 months after discharge, her depressive symptoms remain improved. Patient Health Questionnaire scores indicate mild depression, but Ms. W is not suicidal. She maintains a sleep schedule of 10 PM to 6:30 AM and undergoes 10,000 lux bright light therapy, which she began shortly after discharge, for 30 minutes every morning. She works more productively in psychotherapy, focusing on her eating disorder and anxiety.

Related resource

- Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009; 66(3): 298-301.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydrocodone/APAP • Vicodin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Leuprolide • Lupron

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Refractory depression

Ms. W, age 38, is brought to the emergency department after her son finds her unresponsive and calls 911. Suffering from worsening depression, she wrote a note telling her children goodbye, and overdosed on zolpidem from an old prescription and her daughter’s opioids. After being evaluated and medically cleared in the emergency department, Ms. W was admitted to the psychiatric unit.

Ms. W has a history of recurrent major depressive disorder that developed after she was sexually abused by a relative as a teen. She also has bulimia nervosa, alcohol dependence, and posttraumatic stress disorder. She was hospitalized twice for depression and suicidality but had not previously attempted suicide. In the mid-to-late 1990s, she had trials of paroxetine, clomipramine, lithium, and bupropion.

She was seen regularly in our outpatient psychiatry clinic for medication management and supportive psychotherapy. Since being followed in our clinic starting in early 2005, she has had the following medication trials:

- fluoxetine, citalopram, venlafaxine XR, and duloxetine for depression

- atomoxetine, buspirone, liothyronine, risperidone, and aripiprazole for antidepressant augmentation

- lorazepam, clonazepam, and gabapentin for anxiety

- zolpidem and trazodone for insomnia

- nortriptyline for migraine headache prophylaxis.

Some medications were not tolerated, primarily because of increased anxiety. Those that were tolerated were adequate trials in terms of dose titration and length. High-dose fluoxetine (80 mg/d) augmented by risperidone (0.375 to 0.5 mg/d) produced the most reliable and significant improvement.

Ms. W had 2 courses of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) totaling 30 treatments—most recently in 2007—that resulted in significant memory loss with limited benefit. Premenstrual worsening of depression and suicidality were noted. In collaboration with her gynecologist, Ms. W was treated with a 3-month trial of leuprolide to suppress her ovarian axis, which was helpful. In 2008 she underwent bilateral oophorectomy. She has not had symptoms of mood elevation or psychosis. Family history includes schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and alcoholism.

In the months before hospitalization, Ms. W had been increasingly depressed and intermittently suicidal, although she did not endorse a specific plan or intention to harm herself because she was concerned about the impact suicide would have on her children. Weight gain with risperidone had reactivated body image issues, so Ms. W stopped taking this medication 2 weeks before hospitalization. Her depression became worse, and she began using her husband’s hydrocodone/acetaminophen prescription.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of patients with major depression fail to respond to an initial antidepressant trial.1 An additional 50% of these patients will be treatment-resistant to a subsequent antidepressant.1 Patients may be progressively less likely to respond to additional medication trials.2

One of the most rapid-acting and effective treatments for unipolar and bipolar depression is sleep deprivation. Wirz-Justice et al3 found total or partial sleep deprivation during the second half of the night induced rapid depression remission. Response rates range from 40% to 60% over hours to days.4 Sleep deprivation also can reduce suicidality in patients with seasonal depression.5 This treatment has not been widely employed, however, because up to 80% of patients who undergo sleep deprivation experience rapid and significant depressive relapse.4

Sleep deprivation usually is well tolerated. Potential side effects include:

- headache

- gastrointestinal upset

- fatigue

- cognitive impairment.

Less often, patients report worsening of depressive symptoms and, rarely, suicidal ideation or psychosis.4 Mania or hypomania are potential complications of sleep loss for patients with bipolar or unipolar depression. In a review, Oliwenstein6 suggested that rates of total sleep deprivation-induced mania are likely to be similar to or less than those reported for antidepressants. Because sleep deprivation can induce seizures, this therapy is contraindicated for patients with epilepsy or those at risk for seizures.4

Researchers have successfully explored strategies to reduce the rate of depressive relapse after sleep deprivation, including coadministering light therapy, antidepressants, lithium (particularly for bipolar depression), and sleep-phase advance.4 Sleep-phase advance involves shifting the sleep-wake schedule to a very early sleep time and wake-up time (such as 5 PM to midnight) for 1 day, and then pushing back this schedule by 1 or 2 hours each day until the patient is returned to a “normal” sleep schedule (such as 10 PM to 5 AM). Researchers have demonstrated that sleep-phase advance can have antidepressant effects.7

TREATMENT: Sleep manipulation

Ms. W is continued on fluoxetine, 80 mg/d. We opt for a trial of partial sleep deprivation and sleep-phase advance for Ms. W because of the severity of her depression, her multiple ineffective or poorly tolerated medication trials, and limited benefit from ECT. This treatment involves instituting partial sleep deprivation the first night and subsequently advancing her sleep phase over the next several days (Table 1).

Although she is sleepy the morning after partial sleep deprivation, Ms. W reports a marked improvement in her mood, decline in hopelessness, and absence of suicidal ideation. She continues the sleep-phase advance protocol for the next 3 nights and participates in cognitive-behavioral therapy groups and ward activities. Psychiatric unit staff support her continued wakefulness during sleep manipulation. Because Ms. W had previously responded to antidepressant augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic we add aripiprazole and titrate the dosage to 7.5 mg/d. We also continue fluoxetine, 80 mg/d, and add trazodone, 100 mg at bedtime, and hydroxyzine, 25 mg as needed.

Table 1

Ms. W’s chronotherapy protocol: Hours permitted for sleep*

| Day number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Sleep deprivation | 9 PM to2 AM | ||||

| Sleep-phase advance | 5 PM to midnight | 7 PM to 2 AM | 9 PM to 4 AM | 10 PM to 5 AM | |

| *Treatment was implemented while Ms. W was hospitalized | |||||

The authors’ observations

Chronotherapy incorporates manipulations of the sleep/wake cycle such as sleep deprivation and dark or light therapy. It may use combinations of interventions to generate and sustain a response in patients with depression. In a 4-week pilot study, Moscovici et al8 employed a regimen of late partial sleep deprivation, light, and sleep-phase advance to generate and maintain an anti depressant response in 12 patients. Benedetti et al9 used a similar regimen plus lithium to successfully treat bipolar depression and sleep-phase advance to continue that response in 50% of patients for 3 months.

Circadian rhythms affect the function of serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine, and dopamine.9,10 In a manner similar to antidepressant medications, sleep deprivation may up-regulate or otherwise alter these neurotransmitters’ function. In animals, sleep deprivation increases serotonin function.11 Several hypothetical mechanisms of action for sleep deprivation and other types of chronotherapies have been suggested (Table 2).11-14

Chronotherapies may affect function in brain pathways, as demonstrated by neuroimaging with positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Depression has been associated with increased or decreased brain activity measured by PET or fMRI in regions of the limbic cortex (cingulate and anterior cingulate) and frontal cortex.12

Wu et al13 examined patients treated for depression with medication and total sleep deprivation therapy. Response to treatment was associated with increased function in the cingulate, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex as measured by PET. In contrast, mood improvement was associated with reduced baseline activity in the left medial prefrontal cortex, left frontal pole, and right lateral prefrontal cortex.

Researchers have noted the convergence of sleep-wake rhythms and abnormalities seen in depression and the subsequent link with improved sleep-wake cycles related to depression remission. Bunney and Potkin14 note the powerful effect of zeitgebers—environmental agents that reset the body’s internal clock. They suggested that sleep deprivation may affect the function of “master clock” genes involved in controlling the biological clock. These effects on the suprachiasmatic nucleus hypothalamic pacemaker may improve mood by altering control of genetic expression through chromatin remodeling of this master clock circuit.

Certain factors may increase the likelihood that a patient may respond to chronotherapy (Table 3).9,15-17

Table 2

Sleep deprivation for depression: Possible mechanisms

| Mechanism | Components |

|---|---|

| Alterations to neurotransmitter function | Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine11 |

| Alterations to endogenous circadian pacemaker function | Increased gene expression14 |

| Changes in perfusion/activity of brain regions | Anterior cingulate, frontal cortex regions12,13 |

Table 3

Factors that suggest a patient might respond to chronotherapy

| Diurnal mood variation15 |

| Endogenous depression including insomnia and anorexia16 |

| Abnormal dexamethasone suppression17 |

| High motivation for treatment |

| Bipolar depression (possibly)9 |

OUTCOME: Lasting improvement

Ms. W’s mood improvement is sustained during her week-long hospitalization. At discharge she is hopeful about the future and does not have thoughts of suicide.

At subsequent outpatient visits up to 4 months after discharge, her depressive symptoms remain improved. Patient Health Questionnaire scores indicate mild depression, but Ms. W is not suicidal. She maintains a sleep schedule of 10 PM to 6:30 AM and undergoes 10,000 lux bright light therapy, which she began shortly after discharge, for 30 minutes every morning. She works more productively in psychotherapy, focusing on her eating disorder and anxiety.

Related resource

- Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009; 66(3): 298-301.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydrocodone/APAP • Vicodin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Leuprolide • Lupron

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. AHCPR Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline number 5. Depression in primary care. Volume 2: Treatment of major depression. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. AHCPR publication 93-0550.

2. Fava M, Rush JA, Wisniewski SR, et al. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1161-1172.

3. Wirz-Justice A, Benedetti F, Berger M. Chronotherapeutics (light and wake therapy) in affective disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(7):939-944.

4. Giedke H, Schwärzler F. Therapeutic use of sleep deprivation in depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(5):361-377.

5. Lam RW, Tam EM, Shiah IS, et al. Effects of light therapy on suicidal ideation in patients with winter depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(1):30-32.

6. Oliwenstein L. Lifting moods by losing sleep: an adjunct therapy for treating depression. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2006;12(2):66-70.

7. Wehr TA, Wirz-Justice A, Goodwin FK, et al. Phase advance of the circadian sleep-wake cycle as an antidepressant. Science. 1979;206(4419):710-713.

8. Moscovici L, Kotler M. A multistage chronobiologic intervention for the treatment of depression: a pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):201-217.

9. Benedetti F, Colombo C, Barbini B, et al. Morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;62(3):221-223.

10. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, et al. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(6):509-522.

11. Lopez-Rodriguez F, Wilson CL, Maidment NT, et al. Total sleep deprivation increases extracellular serotonin in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2003;121(2):523-530.

12. Mayberg HS. Defining the neural circuitry of depression: toward a new nosology with therapeutic implications. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):729-730.

13. Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, et al. Sleep deprivation PET correlations of Hamilton symptom improvement ratings with changes in relative glucose metabolism in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):181-186.

14. Bunney JN, Potkin SG. Circadian abnormalities, molecular clock genes and chronobiological treatments in depression. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:23-32.

15. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Lucca A, et al. Sleep deprivation hastens the antidepressant action of fluoxetine. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247(2):100-103.

16. Vogel GW, Thurmond A, Gibbons P, et al. REM sleep reduction effects on depression syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(6):765-777.

17. King D, Dowdy S, Jack R, et al. The dexamethasone suppression test as a predictor of sleep deprivation antidepressant effect. Psychiatry Res. 1982;7(1):93-99.

1. AHCPR Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline number 5. Depression in primary care. Volume 2: Treatment of major depression. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. AHCPR publication 93-0550.

2. Fava M, Rush JA, Wisniewski SR, et al. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1161-1172.

3. Wirz-Justice A, Benedetti F, Berger M. Chronotherapeutics (light and wake therapy) in affective disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(7):939-944.

4. Giedke H, Schwärzler F. Therapeutic use of sleep deprivation in depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(5):361-377.

5. Lam RW, Tam EM, Shiah IS, et al. Effects of light therapy on suicidal ideation in patients with winter depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(1):30-32.

6. Oliwenstein L. Lifting moods by losing sleep: an adjunct therapy for treating depression. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2006;12(2):66-70.

7. Wehr TA, Wirz-Justice A, Goodwin FK, et al. Phase advance of the circadian sleep-wake cycle as an antidepressant. Science. 1979;206(4419):710-713.

8. Moscovici L, Kotler M. A multistage chronobiologic intervention for the treatment of depression: a pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):201-217.

9. Benedetti F, Colombo C, Barbini B, et al. Morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;62(3):221-223.

10. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, et al. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(6):509-522.

11. Lopez-Rodriguez F, Wilson CL, Maidment NT, et al. Total sleep deprivation increases extracellular serotonin in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2003;121(2):523-530.

12. Mayberg HS. Defining the neural circuitry of depression: toward a new nosology with therapeutic implications. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):729-730.

13. Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, et al. Sleep deprivation PET correlations of Hamilton symptom improvement ratings with changes in relative glucose metabolism in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):181-186.

14. Bunney JN, Potkin SG. Circadian abnormalities, molecular clock genes and chronobiological treatments in depression. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:23-32.

15. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Lucca A, et al. Sleep deprivation hastens the antidepressant action of fluoxetine. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247(2):100-103.

16. Vogel GW, Thurmond A, Gibbons P, et al. REM sleep reduction effects on depression syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(6):765-777.

17. King D, Dowdy S, Jack R, et al. The dexamethasone suppression test as a predictor of sleep deprivation antidepressant effect. Psychiatry Res. 1982;7(1):93-99.

Late-life depression: Managing mood in patients with vascular disease

Newly diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD) in patients age ≥65 often has a vascular component. Concomitant cerebrovascular disease (CVD) does not substantially alter the management of late-life depression, but it may affect presenting symptoms, complicate the diagnosis, and influence treatment outcomes.

The relationship between depression and CVD progression remains to be fully explained, and no disease-specific interventions exist to address vascular depression’s pathophysiology. When planning treatment, however, one can draw inferences from existing studies. This article reviews the evidence on late-life depression accompanied by CVD and vascular risk factors, the “vascular depression” concept, and approaches to primary and secondary prevention and treatment.

CVD etiology of depression

Vascular depression constitutes a subgroup of late-life depression, usually associated with neuroimaging abnormalities in the basal ganglia and white matter on MRI.1 The cause of the structural brain changes is thought to be sclerosis in the small arterioles.2 These end-artery vessels may be particularly susceptible to pulse-wave changes caused by arterial rigidity or hypertension.

Alexopoulos et al1 and Krishnan et al3 proposed the concept of vascular depression on the premise that CVD may be etiologically related to geriatric depressive syndromes. Krishnan et al3 examined clinical and demographic characteristics of depressed elderly patients with vascular lesions on brain MRI. Those with clinically defined vascular depression experienced greater cognitive dysfunction, disability, and psychomotor retardation but less agitation and guilt feelings than patients with nonvascular depression.

Clinically, vascular depression resembles a medial frontal lobe syndrome, with prominent psychomotor retardation, apathy, and pronounced disability.4 Depression with vascular stigmata or cerebrovascular lesions on neuroimaging is characterized by poor outcomes, including persistent depressive symptoms, unstable remission, and increased risk for dementia.5,6 Patients with depression and subcortical vascular lesions have been shown to respond poorly to antidepressants.6

Impaired brain function also may predispose to geriatric depression, described by Alexopoulos as “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome of late life.”7 This common syndrome’s presentation—psychomotor retardation, lack of interest, limited depressive ideation and insight, and prominent disability—is consistent with its underlying abnormalities.5 Executive dysfunction also predicts limited response to antidepressants.8 Thus, the presentation and course of depression-executive dysfunction syndrome are consistent with those of subcortical ischemic depression.

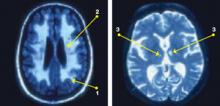

Neuroimaging support

The vascular depression hypothesis is supported by observations related to MRI hyperintensities (HI):

- CT and MRI studies identify HI in persons with late-life depression.

- HI are associated with age and cerebrovascular risk factors.

- Pathophysiologic evidence indicates that HI are associated with widespread diminution in cerebral perfusion.9

Neuropathologic correlates of HI are diverse and represent ischemic changes, together with demyelination, edema, and gliosis.9-11 The putative link between HI and vascular disease is central to the vascular theory of depression.

In a study of 56 patients age ≥50 meeting DSM-III-R criteria for MDD, Fujikawa et al12 reported “silent cerebral infarctions” on MRI in 60% of patients. High rates of abnormalities consistently have been observed on MRIs of older adults with MDD,10,11 and these can be classified into 3 types (Figure):

- Periventricular HI are halos or rims adjacent to ventricles that in severe forms may invade surrounding deep white matter.

- Deep white matter HI are single, patchy, or confluent foci observed in subcortical white matter.

- Deep gray matter HI may be found, particularly in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and pons.9

These leukoaraiosis (or encephalomalacia) occur more frequently in patients with geriatric depression than in normal controls13 or patients with Alzheimer’s disease14 and may be comparable to the rate associated with vascular dementia.15 Observations in older adults11 suggest that diminished brain volume (especially in frontal regions) and HI may provide additive, albeit autonomous, pathways to late-life MDD. Vascular and nonvascular medical comorbidity contribute to HI, which in turn facilitate MDD.

Figure: Subcortical cerebrovascular disease in late-life depression