User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

A mysterious case of mania

CASE: First-episode mania

Mrs. P, age 47, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because her family is concerned about her behavioral changes over the last week. Her husband reports that Mrs. P has become hyper-religious and talkative. She has been perseverating on numbers and dates and incessantly calling people. Mrs. P reports increased energy and decreased need for sleep. On examination, she has pressured speech. She has no psychiatric history; however, for the past year, she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg/d, and desipramine, 25 mg/d, which her primary care physician prescribed for unknown reasons.

Mrs. P has struggled with chronic back pain for years, but an MRI of her spine is negative. Her family strongly believes that for the past 3 years Mrs. P has been receiving too many medications from her pain management specialist. Six weeks before her current presentation, she was receiving methadone, 40 mg/d, hydrocodone, at least 20 mg/d, and tramadol, 400 mg/d in divided doses. She also was taking an unknown dose of at least 1 benzodiazepine.

Mrs. P’s husband notes she stopped taking methadone abruptly approximately 5 weeks ago. However, about 3 weeks ago, Mrs. P accidentally overdosed on opioids and was hospitalized for several days. Urine drug screen at the time was positive for acetaminophen, salicylate, propoxyphene, opiate, benzodiazepine, and tricyclic antidepressant.

Mrs. P’s medical history includes auditory nerve loss from birth; her mother had German measles (rubella). Mrs. P never learned American Sign Language. She underwent cochlear implant surgery 1 year ago and now has only mild difficulties speaking.

The authors’ observations

Manic symptoms are common in patients with comorbid medical disorders and present a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining an accurate history from the patient may be difficult. Such evaluations often require extensive investigation and collection of data from multiple sources, including:

- medical records

- family members

- patient observation.

Mrs. P’s history is marked by contradicting data from these sources. For example, her family says she stopped taking “pain medications” 5 weeks ago, but 2 weeks later her urine drug screen showed opioids.

Both illicit drugs and prescribed medications can precipitate manic symptoms. From medical records and drug testing, it was evident that Mrs. P had a history of medication abuse/overdose/misuse.

Mania also has been associated with substance withdrawal. Mrs. P allegedly stopped taking methadone 4 weeks before the onset of manic symptoms. Methadone is a synthetic opioid with a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile that presents clinical challenges, including:

- large interindividual variability in methadone pharmacokinetics

- lack of reliable equianalgesic conversion ratio to and from other opioids

- potential for multiple drug interactions and complex pharmacodynamics.

An opioid’s half-life determines the onset and duration of withdrawal syndrome symptoms.1 Methadone metabolism is predominantly mediated by CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, and to some extent by CYP2C19.1 We performed genetic testing to help evaluate how Mrs. P metabolized medications. Mrs. P had a normal genotype for CYP2D6, which meant that she should process opioids at a normal rate; however, she was heterozygous for CYP2C19*2 polymorphism, so it is possible that methadone stayed in her system longer than average.

Evidence documenting methadone drug interactions is limited (Table 1).1 Mrs. P was taking sertraline and desipramine; both have potent effects via 2D6 inhibition that could increase plasma methadone concentration. Other evidence indicates that benzodiazepines and methadone may have synergistic interactions that could increase opioid sedation or respiratory depression.1

Table 1

Is a drug interaction with methadone causing Mrs. P’s mania?

| Medication class/agent | Effect on methadone level | Effect on methadone metabolism | Additional effects of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Fluvoxamine | Increase | Inhibition | Opioid toxicity |

| Fluoxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Decreased hepatic metabolism |

| Sertraline* | Increase | Autoinduction | Torsades de pointes |

| Citalopram | — | — | Torsades de pointes |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |||

| Desipramine* | — | Inhibition | Increased desipramine levels/inhibition of desipramine metabolism |

| Amitriptyline | Increase methadone clearance | — | Torsades de pointes/prolonged QT interval |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| NSAIDs* | — | — | Enhanced analgesia/opioid-sparing effect |

| Aspirin* | — | — | Paradoxical activation of platelet receptors |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Alprazolam | — | — | CNS depression/sedation/overdose |

| Diazepam* | — | Inhibition | Additive depressant effects |

| Opioid agonists | |||

| Dextromethorphan | — | Inhibition (not significant) | Increased side effects, especially sleepiness and drowsiness |

| Tramadol* | — | — | Well tolerated |

| Nicotine | Decrease | Can increase smoking rate | |

| *Medications taken by Mrs. P | |||

| NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| Source: Reference 1 | |||

EVALUATION: Few clues

In our ED, Mrs. P’s urine drug abuse screen is positive for salicylate and benzodiazepine only. Findings from physical examination, vital signs, ECG, and chest radiography are within normal limits. Internal medicine consultation is unremarkable. Mrs. P’s laboratory investigation is notable for an elevated white blood cell count, but this normalizes over a week.

Mrs. P shows no evidence of infection and is normoglycemic. B12 and folate are within normal limits. Serum electrolytes, liver function testing, sensitive thyroid stimulating hormone, and C-reactive protein are within normal limits. Urinalysis is negative except for a small amount of hemoglobin. Her creatine kinase (CK) is in the upper normal range. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis testing is negative. Ceruloplasmin level also is normal. Heavy metal screen is negative. Head MRI and CT from previous hospitalizations were unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

Our first step was to clarify Mrs. P’s diagnosis. In reviewing differential diagnoses, we considered:

- serotonin syndrome

- benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- antidepressant-induced mania

- adrenergic toxicity

- malignant hyperthermia

- heat stroke

- infectious causes.

Our index of suspicion for serotonin syndrome was low because Mrs. P didn’t meet criteria required for diagnosis. Relevant signs and symptoms included confusion, elevated mood (major) and agitation, nervousness, insomnia, and low blood pressure (minor).

Based on concerns about medication interactions, we discontinued sertraline and desipramine. According to the patient’s sister, Mrs. P’s manic symptoms markedly responded to PRN doses of lorazepam. We prescribed lorazepam, 1 mg every 6 hours, and observed Mrs. P for signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal.

HISTORY: OTC drug use

According to Mrs. P’s mother, after her daughter abruptly discontinued methadone, she began to have very strong headaches, which she treated with Excedrin or Excedrin Sinus. The mother said that 4 days before Mrs. P came to the ED, she found her daughter holding 4 tablets of Excedrin and an empty bottle. Unfortunately her mother was unable to say what type of Excedrin it was. When the treatment team asks Mrs. P how many pills she usually takes, she says she doesn’t know but usually until the pain stops.

The authors’ observations

Management of secondary mania should focus on treating the underlying condition (Algorithm). Neurology categorizes mania into 3 categories:2

- confusional-delirious states

- manic symptoms associated with focal or multifocal cerebral lesions

- affective disorders (manic-depressive and depressive psychoses).

Medical workup ruled out common secondary causes of psychosis. Collaborative information from relatives revealed no family history of mental illness.

Patients with hearing loss and deafness have been shown to be at increased risk for psychotic disorders compared with the general population. Severe sensory deficits early in Mrs. P’s life may have influenced the orderly development of neural connections in her sensory cortex and association areas.3 Mrs. P was deaf for the first 45 years of life. It could be hypothesized that her sensory deficits significantly influenced her ability to reality test. After receiving a cochlear implant, Mrs. P rapidly went from no auditory stimulation to marked improvement. This stressor might precipitate psychotic symptoms. However, her presentation seemed to be characterized more by manic symptoms or an agitated delirium. It also did not fit temporally with her presentation.

We begin to suspect that Mrs. P’s mania is substance-induced. Excedrin, an over-the-counter medication, contains aspirin and caffeine. Excedrin Sinus also contains phenylephrine. Amphetamines, caffeine, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine have all been linked to manic-like psychotic episodes.

Concerns about the illicit conversion of pseudoephedrine into methamphetamine obliged pharmaceutical companies in the United States to switch product formulations to phenylephrine in 2005,4 although some “behind-the-counter” medications may contain pseudoephedrine. Phenylephrine is a relatively selective α1 agonist with weak α2 adrenoceptor agonist activity and low β agonist activity. It is very similar to pseudo-ephedrine, which is known to be implicated in the development of manic symptoms.5,6

Pseudoephedrine can raise CK levels and cause rhabdomyolysis.7,8 Mrs. P’s CK level was 176 (normal range 36 to 176 U/L) 4 days after her initial presentation, and she had a moderate amount of myoglobin in her urine. Her creatinine was normal. The patient was taking excessive amounts of caffeine and—if she was using Excedrin Sinus—pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. We were unable to determine whether her Excedrin contained pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. In addition, she was going through opioid withdrawal and reported problems with her sleep. There was also a question of Mrs. P’s unknown methadone use combined with its decreased clearance secondary to medication interactions.

While previously hospitalized for overdose, Mrs. P tested positive for propoxyphene. Excessive use of propoxyphene also can cause numerous adverse reactions. Some of that could have explained why Mrs. P’s presentation includes nervousness, CNS stimulation, excitement, insomnia, and restlessness.5

Based on multiple factors, we believe Mrs. P meets DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder (Table 2).9 This diagnosis is supported by Mrs. P’s history of complex polypharmacy, excessive caffeine use, sleep deprivation, and possible opioid withdrawal.

Algorithm: Managing substance-induced manic disorder

CK: creatine kinase; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; EEG: electroencephalogram; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratoryTable 2

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder*

| A. A prominent and persistent disturbance in mood predominates in the clinical picture and is characterized by either (or both) of the following: 1. depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities 2. elevated, expansive, or irritable mood |

| B. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings of: 1. the symptoms in Criterion A developed during, or within 1 month of, substance intoxication or withdrawal, or 2. medication use is etiologically related to the disturbance |

| C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by a mood disorder that is not substance-induced |

| D. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium |

| E. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Minimal criteria are A plus B plus E |

| *Make this diagnosis only when mood symptoms are in excess of those usually associated with substance intoxication or substance withdrawal syndrome and when symptoms are sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention |

| Source: Reference 9 |

TREATMENT: Escalating symptoms

While hospitalized, Mrs. P focuses solely on receiving pain medication. She does not know why she is in the hospital. She is easily distractible, intermittently intrusive, and disorganized and tangential in her thought process.

Two days after admission, her uncontrolled behavior escalates and she has marked psychomotor agitation. She is confused but remains oriented to time, place, and person. We start treatment with risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, because this agent is well tolerated, efficacious, and easily titrated to symptom response. Mrs. P’s symptoms improve, but she does not return to her reported baseline. Two days later, we increase risperidone to 1 mg every morning and 2 mg at bedtime. On the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. P is more organized and able to follow simple commands. She denies auditory or visual hallucinations. On the 10th day, she improves markedly and is back to her baseline level of functioning.

We perform psychological testing, including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III) and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS, Form A). The results show global neurocognitive deficits. Mrs. P’s intellectual skill is significantly below average, with verbal abilities reflecting functioning in the mildly retarded range. Nonverbal skills were stronger but still below average. Mrs. P’s capacity to learn and retain new information and to understand even modestly complex concepts is quite limited.

Because of Mrs. P’s long history of poly-substance abuse, inability to process information, and chronic back pain, we judge her to be at high risk for relapse. However, Mrs. P and her family are not interested in chemical dependence treatment.

This left us facing a difficult clinical situation. Mrs. P had a pattern of presenting to multiple physicians and eventually receiving narcotics. Her family provided transportation for her to these appointments but also was concerned about her drug use. With the patient and her family, we carefully outline Mrs. P’s treatment needs, including:

- medication monitoring by a psychiatrist after discharge

- a single, consistent primary care physician to manage her care

- a treatment plan shared by all clinicians involved in her care.

We review with Mrs. P and her family the benefits of behavioral approaches to chronic pain management. They agree to our recommendation that the family control Mrs. P’s medication supply. We discharge her on risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and she is scheduled for follow-up with a local psychiatrist.

Related resource

- Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Vicodin, Lortab, others

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propoxyphene • Darvon, Darvocet, others

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. De Fazio S, Gallelli L, De Siena A, et al. Role of CYP3A5 in abnormal clearance methadone. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(6):893-897.

2. Ropper AH, Brown RH. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005.

3. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(1):99-103.

4. Eccles R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(1):10-14.

5. Wilson H, Woods D. Pseudoephedrine causing mania-like symptoms. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1148):86.-

6. Dalton R. Mixed bipolar disorder precipitated by pseudoephedrine hydrochloride. South Med J. 1990;83(1):64-65.

7. Mansi IA, Huang J. Rhabdomyolysis in response to weight-loss herbal medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:356-357.

8. Sandhu RS, Como JJ, Scalea TS. Renal failure and exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients taking performance-enhancing compounds. J Trauma. 2002;53:761-764.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

CASE: First-episode mania

Mrs. P, age 47, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because her family is concerned about her behavioral changes over the last week. Her husband reports that Mrs. P has become hyper-religious and talkative. She has been perseverating on numbers and dates and incessantly calling people. Mrs. P reports increased energy and decreased need for sleep. On examination, she has pressured speech. She has no psychiatric history; however, for the past year, she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg/d, and desipramine, 25 mg/d, which her primary care physician prescribed for unknown reasons.

Mrs. P has struggled with chronic back pain for years, but an MRI of her spine is negative. Her family strongly believes that for the past 3 years Mrs. P has been receiving too many medications from her pain management specialist. Six weeks before her current presentation, she was receiving methadone, 40 mg/d, hydrocodone, at least 20 mg/d, and tramadol, 400 mg/d in divided doses. She also was taking an unknown dose of at least 1 benzodiazepine.

Mrs. P’s husband notes she stopped taking methadone abruptly approximately 5 weeks ago. However, about 3 weeks ago, Mrs. P accidentally overdosed on opioids and was hospitalized for several days. Urine drug screen at the time was positive for acetaminophen, salicylate, propoxyphene, opiate, benzodiazepine, and tricyclic antidepressant.

Mrs. P’s medical history includes auditory nerve loss from birth; her mother had German measles (rubella). Mrs. P never learned American Sign Language. She underwent cochlear implant surgery 1 year ago and now has only mild difficulties speaking.

The authors’ observations

Manic symptoms are common in patients with comorbid medical disorders and present a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining an accurate history from the patient may be difficult. Such evaluations often require extensive investigation and collection of data from multiple sources, including:

- medical records

- family members

- patient observation.

Mrs. P’s history is marked by contradicting data from these sources. For example, her family says she stopped taking “pain medications” 5 weeks ago, but 2 weeks later her urine drug screen showed opioids.

Both illicit drugs and prescribed medications can precipitate manic symptoms. From medical records and drug testing, it was evident that Mrs. P had a history of medication abuse/overdose/misuse.

Mania also has been associated with substance withdrawal. Mrs. P allegedly stopped taking methadone 4 weeks before the onset of manic symptoms. Methadone is a synthetic opioid with a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile that presents clinical challenges, including:

- large interindividual variability in methadone pharmacokinetics

- lack of reliable equianalgesic conversion ratio to and from other opioids

- potential for multiple drug interactions and complex pharmacodynamics.

An opioid’s half-life determines the onset and duration of withdrawal syndrome symptoms.1 Methadone metabolism is predominantly mediated by CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, and to some extent by CYP2C19.1 We performed genetic testing to help evaluate how Mrs. P metabolized medications. Mrs. P had a normal genotype for CYP2D6, which meant that she should process opioids at a normal rate; however, she was heterozygous for CYP2C19*2 polymorphism, so it is possible that methadone stayed in her system longer than average.

Evidence documenting methadone drug interactions is limited (Table 1).1 Mrs. P was taking sertraline and desipramine; both have potent effects via 2D6 inhibition that could increase plasma methadone concentration. Other evidence indicates that benzodiazepines and methadone may have synergistic interactions that could increase opioid sedation or respiratory depression.1

Table 1

Is a drug interaction with methadone causing Mrs. P’s mania?

| Medication class/agent | Effect on methadone level | Effect on methadone metabolism | Additional effects of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Fluvoxamine | Increase | Inhibition | Opioid toxicity |

| Fluoxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Decreased hepatic metabolism |

| Sertraline* | Increase | Autoinduction | Torsades de pointes |

| Citalopram | — | — | Torsades de pointes |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |||

| Desipramine* | — | Inhibition | Increased desipramine levels/inhibition of desipramine metabolism |

| Amitriptyline | Increase methadone clearance | — | Torsades de pointes/prolonged QT interval |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| NSAIDs* | — | — | Enhanced analgesia/opioid-sparing effect |

| Aspirin* | — | — | Paradoxical activation of platelet receptors |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Alprazolam | — | — | CNS depression/sedation/overdose |

| Diazepam* | — | Inhibition | Additive depressant effects |

| Opioid agonists | |||

| Dextromethorphan | — | Inhibition (not significant) | Increased side effects, especially sleepiness and drowsiness |

| Tramadol* | — | — | Well tolerated |

| Nicotine | Decrease | Can increase smoking rate | |

| *Medications taken by Mrs. P | |||

| NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| Source: Reference 1 | |||

EVALUATION: Few clues

In our ED, Mrs. P’s urine drug abuse screen is positive for salicylate and benzodiazepine only. Findings from physical examination, vital signs, ECG, and chest radiography are within normal limits. Internal medicine consultation is unremarkable. Mrs. P’s laboratory investigation is notable for an elevated white blood cell count, but this normalizes over a week.

Mrs. P shows no evidence of infection and is normoglycemic. B12 and folate are within normal limits. Serum electrolytes, liver function testing, sensitive thyroid stimulating hormone, and C-reactive protein are within normal limits. Urinalysis is negative except for a small amount of hemoglobin. Her creatine kinase (CK) is in the upper normal range. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis testing is negative. Ceruloplasmin level also is normal. Heavy metal screen is negative. Head MRI and CT from previous hospitalizations were unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

Our first step was to clarify Mrs. P’s diagnosis. In reviewing differential diagnoses, we considered:

- serotonin syndrome

- benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- antidepressant-induced mania

- adrenergic toxicity

- malignant hyperthermia

- heat stroke

- infectious causes.

Our index of suspicion for serotonin syndrome was low because Mrs. P didn’t meet criteria required for diagnosis. Relevant signs and symptoms included confusion, elevated mood (major) and agitation, nervousness, insomnia, and low blood pressure (minor).

Based on concerns about medication interactions, we discontinued sertraline and desipramine. According to the patient’s sister, Mrs. P’s manic symptoms markedly responded to PRN doses of lorazepam. We prescribed lorazepam, 1 mg every 6 hours, and observed Mrs. P for signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal.

HISTORY: OTC drug use

According to Mrs. P’s mother, after her daughter abruptly discontinued methadone, she began to have very strong headaches, which she treated with Excedrin or Excedrin Sinus. The mother said that 4 days before Mrs. P came to the ED, she found her daughter holding 4 tablets of Excedrin and an empty bottle. Unfortunately her mother was unable to say what type of Excedrin it was. When the treatment team asks Mrs. P how many pills she usually takes, she says she doesn’t know but usually until the pain stops.

The authors’ observations

Management of secondary mania should focus on treating the underlying condition (Algorithm). Neurology categorizes mania into 3 categories:2

- confusional-delirious states

- manic symptoms associated with focal or multifocal cerebral lesions

- affective disorders (manic-depressive and depressive psychoses).

Medical workup ruled out common secondary causes of psychosis. Collaborative information from relatives revealed no family history of mental illness.

Patients with hearing loss and deafness have been shown to be at increased risk for psychotic disorders compared with the general population. Severe sensory deficits early in Mrs. P’s life may have influenced the orderly development of neural connections in her sensory cortex and association areas.3 Mrs. P was deaf for the first 45 years of life. It could be hypothesized that her sensory deficits significantly influenced her ability to reality test. After receiving a cochlear implant, Mrs. P rapidly went from no auditory stimulation to marked improvement. This stressor might precipitate psychotic symptoms. However, her presentation seemed to be characterized more by manic symptoms or an agitated delirium. It also did not fit temporally with her presentation.

We begin to suspect that Mrs. P’s mania is substance-induced. Excedrin, an over-the-counter medication, contains aspirin and caffeine. Excedrin Sinus also contains phenylephrine. Amphetamines, caffeine, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine have all been linked to manic-like psychotic episodes.

Concerns about the illicit conversion of pseudoephedrine into methamphetamine obliged pharmaceutical companies in the United States to switch product formulations to phenylephrine in 2005,4 although some “behind-the-counter” medications may contain pseudoephedrine. Phenylephrine is a relatively selective α1 agonist with weak α2 adrenoceptor agonist activity and low β agonist activity. It is very similar to pseudo-ephedrine, which is known to be implicated in the development of manic symptoms.5,6

Pseudoephedrine can raise CK levels and cause rhabdomyolysis.7,8 Mrs. P’s CK level was 176 (normal range 36 to 176 U/L) 4 days after her initial presentation, and she had a moderate amount of myoglobin in her urine. Her creatinine was normal. The patient was taking excessive amounts of caffeine and—if she was using Excedrin Sinus—pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. We were unable to determine whether her Excedrin contained pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. In addition, she was going through opioid withdrawal and reported problems with her sleep. There was also a question of Mrs. P’s unknown methadone use combined with its decreased clearance secondary to medication interactions.

While previously hospitalized for overdose, Mrs. P tested positive for propoxyphene. Excessive use of propoxyphene also can cause numerous adverse reactions. Some of that could have explained why Mrs. P’s presentation includes nervousness, CNS stimulation, excitement, insomnia, and restlessness.5

Based on multiple factors, we believe Mrs. P meets DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder (Table 2).9 This diagnosis is supported by Mrs. P’s history of complex polypharmacy, excessive caffeine use, sleep deprivation, and possible opioid withdrawal.

Algorithm: Managing substance-induced manic disorder

CK: creatine kinase; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; EEG: electroencephalogram; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratoryTable 2

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder*

| A. A prominent and persistent disturbance in mood predominates in the clinical picture and is characterized by either (or both) of the following: 1. depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities 2. elevated, expansive, or irritable mood |

| B. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings of: 1. the symptoms in Criterion A developed during, or within 1 month of, substance intoxication or withdrawal, or 2. medication use is etiologically related to the disturbance |

| C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by a mood disorder that is not substance-induced |

| D. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium |

| E. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Minimal criteria are A plus B plus E |

| *Make this diagnosis only when mood symptoms are in excess of those usually associated with substance intoxication or substance withdrawal syndrome and when symptoms are sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention |

| Source: Reference 9 |

TREATMENT: Escalating symptoms

While hospitalized, Mrs. P focuses solely on receiving pain medication. She does not know why she is in the hospital. She is easily distractible, intermittently intrusive, and disorganized and tangential in her thought process.

Two days after admission, her uncontrolled behavior escalates and she has marked psychomotor agitation. She is confused but remains oriented to time, place, and person. We start treatment with risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, because this agent is well tolerated, efficacious, and easily titrated to symptom response. Mrs. P’s symptoms improve, but she does not return to her reported baseline. Two days later, we increase risperidone to 1 mg every morning and 2 mg at bedtime. On the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. P is more organized and able to follow simple commands. She denies auditory or visual hallucinations. On the 10th day, she improves markedly and is back to her baseline level of functioning.

We perform psychological testing, including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III) and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS, Form A). The results show global neurocognitive deficits. Mrs. P’s intellectual skill is significantly below average, with verbal abilities reflecting functioning in the mildly retarded range. Nonverbal skills were stronger but still below average. Mrs. P’s capacity to learn and retain new information and to understand even modestly complex concepts is quite limited.

Because of Mrs. P’s long history of poly-substance abuse, inability to process information, and chronic back pain, we judge her to be at high risk for relapse. However, Mrs. P and her family are not interested in chemical dependence treatment.

This left us facing a difficult clinical situation. Mrs. P had a pattern of presenting to multiple physicians and eventually receiving narcotics. Her family provided transportation for her to these appointments but also was concerned about her drug use. With the patient and her family, we carefully outline Mrs. P’s treatment needs, including:

- medication monitoring by a psychiatrist after discharge

- a single, consistent primary care physician to manage her care

- a treatment plan shared by all clinicians involved in her care.

We review with Mrs. P and her family the benefits of behavioral approaches to chronic pain management. They agree to our recommendation that the family control Mrs. P’s medication supply. We discharge her on risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and she is scheduled for follow-up with a local psychiatrist.

Related resource

- Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Vicodin, Lortab, others

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propoxyphene • Darvon, Darvocet, others

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: First-episode mania

Mrs. P, age 47, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because her family is concerned about her behavioral changes over the last week. Her husband reports that Mrs. P has become hyper-religious and talkative. She has been perseverating on numbers and dates and incessantly calling people. Mrs. P reports increased energy and decreased need for sleep. On examination, she has pressured speech. She has no psychiatric history; however, for the past year, she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg/d, and desipramine, 25 mg/d, which her primary care physician prescribed for unknown reasons.

Mrs. P has struggled with chronic back pain for years, but an MRI of her spine is negative. Her family strongly believes that for the past 3 years Mrs. P has been receiving too many medications from her pain management specialist. Six weeks before her current presentation, she was receiving methadone, 40 mg/d, hydrocodone, at least 20 mg/d, and tramadol, 400 mg/d in divided doses. She also was taking an unknown dose of at least 1 benzodiazepine.

Mrs. P’s husband notes she stopped taking methadone abruptly approximately 5 weeks ago. However, about 3 weeks ago, Mrs. P accidentally overdosed on opioids and was hospitalized for several days. Urine drug screen at the time was positive for acetaminophen, salicylate, propoxyphene, opiate, benzodiazepine, and tricyclic antidepressant.

Mrs. P’s medical history includes auditory nerve loss from birth; her mother had German measles (rubella). Mrs. P never learned American Sign Language. She underwent cochlear implant surgery 1 year ago and now has only mild difficulties speaking.

The authors’ observations

Manic symptoms are common in patients with comorbid medical disorders and present a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining an accurate history from the patient may be difficult. Such evaluations often require extensive investigation and collection of data from multiple sources, including:

- medical records

- family members

- patient observation.

Mrs. P’s history is marked by contradicting data from these sources. For example, her family says she stopped taking “pain medications” 5 weeks ago, but 2 weeks later her urine drug screen showed opioids.

Both illicit drugs and prescribed medications can precipitate manic symptoms. From medical records and drug testing, it was evident that Mrs. P had a history of medication abuse/overdose/misuse.

Mania also has been associated with substance withdrawal. Mrs. P allegedly stopped taking methadone 4 weeks before the onset of manic symptoms. Methadone is a synthetic opioid with a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile that presents clinical challenges, including:

- large interindividual variability in methadone pharmacokinetics

- lack of reliable equianalgesic conversion ratio to and from other opioids

- potential for multiple drug interactions and complex pharmacodynamics.

An opioid’s half-life determines the onset and duration of withdrawal syndrome symptoms.1 Methadone metabolism is predominantly mediated by CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, and to some extent by CYP2C19.1 We performed genetic testing to help evaluate how Mrs. P metabolized medications. Mrs. P had a normal genotype for CYP2D6, which meant that she should process opioids at a normal rate; however, she was heterozygous for CYP2C19*2 polymorphism, so it is possible that methadone stayed in her system longer than average.

Evidence documenting methadone drug interactions is limited (Table 1).1 Mrs. P was taking sertraline and desipramine; both have potent effects via 2D6 inhibition that could increase plasma methadone concentration. Other evidence indicates that benzodiazepines and methadone may have synergistic interactions that could increase opioid sedation or respiratory depression.1

Table 1

Is a drug interaction with methadone causing Mrs. P’s mania?

| Medication class/agent | Effect on methadone level | Effect on methadone metabolism | Additional effects of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Fluvoxamine | Increase | Inhibition | Opioid toxicity |

| Fluoxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxetine | Increase | Inhibition | Decreased hepatic metabolism |

| Sertraline* | Increase | Autoinduction | Torsades de pointes |

| Citalopram | — | — | Torsades de pointes |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |||

| Desipramine* | — | Inhibition | Increased desipramine levels/inhibition of desipramine metabolism |

| Amitriptyline | Increase methadone clearance | — | Torsades de pointes/prolonged QT interval |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| NSAIDs* | — | — | Enhanced analgesia/opioid-sparing effect |

| Aspirin* | — | — | Paradoxical activation of platelet receptors |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Alprazolam | — | — | CNS depression/sedation/overdose |

| Diazepam* | — | Inhibition | Additive depressant effects |

| Opioid agonists | |||

| Dextromethorphan | — | Inhibition (not significant) | Increased side effects, especially sleepiness and drowsiness |

| Tramadol* | — | — | Well tolerated |

| Nicotine | Decrease | Can increase smoking rate | |

| *Medications taken by Mrs. P | |||

| NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| Source: Reference 1 | |||

EVALUATION: Few clues

In our ED, Mrs. P’s urine drug abuse screen is positive for salicylate and benzodiazepine only. Findings from physical examination, vital signs, ECG, and chest radiography are within normal limits. Internal medicine consultation is unremarkable. Mrs. P’s laboratory investigation is notable for an elevated white blood cell count, but this normalizes over a week.

Mrs. P shows no evidence of infection and is normoglycemic. B12 and folate are within normal limits. Serum electrolytes, liver function testing, sensitive thyroid stimulating hormone, and C-reactive protein are within normal limits. Urinalysis is negative except for a small amount of hemoglobin. Her creatine kinase (CK) is in the upper normal range. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis testing is negative. Ceruloplasmin level also is normal. Heavy metal screen is negative. Head MRI and CT from previous hospitalizations were unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

Our first step was to clarify Mrs. P’s diagnosis. In reviewing differential diagnoses, we considered:

- serotonin syndrome

- benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- antidepressant-induced mania

- adrenergic toxicity

- malignant hyperthermia

- heat stroke

- infectious causes.

Our index of suspicion for serotonin syndrome was low because Mrs. P didn’t meet criteria required for diagnosis. Relevant signs and symptoms included confusion, elevated mood (major) and agitation, nervousness, insomnia, and low blood pressure (minor).

Based on concerns about medication interactions, we discontinued sertraline and desipramine. According to the patient’s sister, Mrs. P’s manic symptoms markedly responded to PRN doses of lorazepam. We prescribed lorazepam, 1 mg every 6 hours, and observed Mrs. P for signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal.

HISTORY: OTC drug use

According to Mrs. P’s mother, after her daughter abruptly discontinued methadone, she began to have very strong headaches, which she treated with Excedrin or Excedrin Sinus. The mother said that 4 days before Mrs. P came to the ED, she found her daughter holding 4 tablets of Excedrin and an empty bottle. Unfortunately her mother was unable to say what type of Excedrin it was. When the treatment team asks Mrs. P how many pills she usually takes, she says she doesn’t know but usually until the pain stops.

The authors’ observations

Management of secondary mania should focus on treating the underlying condition (Algorithm). Neurology categorizes mania into 3 categories:2

- confusional-delirious states

- manic symptoms associated with focal or multifocal cerebral lesions

- affective disorders (manic-depressive and depressive psychoses).

Medical workup ruled out common secondary causes of psychosis. Collaborative information from relatives revealed no family history of mental illness.

Patients with hearing loss and deafness have been shown to be at increased risk for psychotic disorders compared with the general population. Severe sensory deficits early in Mrs. P’s life may have influenced the orderly development of neural connections in her sensory cortex and association areas.3 Mrs. P was deaf for the first 45 years of life. It could be hypothesized that her sensory deficits significantly influenced her ability to reality test. After receiving a cochlear implant, Mrs. P rapidly went from no auditory stimulation to marked improvement. This stressor might precipitate psychotic symptoms. However, her presentation seemed to be characterized more by manic symptoms or an agitated delirium. It also did not fit temporally with her presentation.

We begin to suspect that Mrs. P’s mania is substance-induced. Excedrin, an over-the-counter medication, contains aspirin and caffeine. Excedrin Sinus also contains phenylephrine. Amphetamines, caffeine, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine have all been linked to manic-like psychotic episodes.

Concerns about the illicit conversion of pseudoephedrine into methamphetamine obliged pharmaceutical companies in the United States to switch product formulations to phenylephrine in 2005,4 although some “behind-the-counter” medications may contain pseudoephedrine. Phenylephrine is a relatively selective α1 agonist with weak α2 adrenoceptor agonist activity and low β agonist activity. It is very similar to pseudo-ephedrine, which is known to be implicated in the development of manic symptoms.5,6

Pseudoephedrine can raise CK levels and cause rhabdomyolysis.7,8 Mrs. P’s CK level was 176 (normal range 36 to 176 U/L) 4 days after her initial presentation, and she had a moderate amount of myoglobin in her urine. Her creatinine was normal. The patient was taking excessive amounts of caffeine and—if she was using Excedrin Sinus—pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. We were unable to determine whether her Excedrin contained pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. In addition, she was going through opioid withdrawal and reported problems with her sleep. There was also a question of Mrs. P’s unknown methadone use combined with its decreased clearance secondary to medication interactions.

While previously hospitalized for overdose, Mrs. P tested positive for propoxyphene. Excessive use of propoxyphene also can cause numerous adverse reactions. Some of that could have explained why Mrs. P’s presentation includes nervousness, CNS stimulation, excitement, insomnia, and restlessness.5

Based on multiple factors, we believe Mrs. P meets DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder (Table 2).9 This diagnosis is supported by Mrs. P’s history of complex polypharmacy, excessive caffeine use, sleep deprivation, and possible opioid withdrawal.

Algorithm: Managing substance-induced manic disorder

CK: creatine kinase; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; EEG: electroencephalogram; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratoryTable 2

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced mood disorder*

| A. A prominent and persistent disturbance in mood predominates in the clinical picture and is characterized by either (or both) of the following: 1. depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities 2. elevated, expansive, or irritable mood |

| B. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings of: 1. the symptoms in Criterion A developed during, or within 1 month of, substance intoxication or withdrawal, or 2. medication use is etiologically related to the disturbance |

| C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by a mood disorder that is not substance-induced |

| D. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium |

| E. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Minimal criteria are A plus B plus E |

| *Make this diagnosis only when mood symptoms are in excess of those usually associated with substance intoxication or substance withdrawal syndrome and when symptoms are sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention |

| Source: Reference 9 |

TREATMENT: Escalating symptoms

While hospitalized, Mrs. P focuses solely on receiving pain medication. She does not know why she is in the hospital. She is easily distractible, intermittently intrusive, and disorganized and tangential in her thought process.

Two days after admission, her uncontrolled behavior escalates and she has marked psychomotor agitation. She is confused but remains oriented to time, place, and person. We start treatment with risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, because this agent is well tolerated, efficacious, and easily titrated to symptom response. Mrs. P’s symptoms improve, but she does not return to her reported baseline. Two days later, we increase risperidone to 1 mg every morning and 2 mg at bedtime. On the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. P is more organized and able to follow simple commands. She denies auditory or visual hallucinations. On the 10th day, she improves markedly and is back to her baseline level of functioning.

We perform psychological testing, including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III) and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS, Form A). The results show global neurocognitive deficits. Mrs. P’s intellectual skill is significantly below average, with verbal abilities reflecting functioning in the mildly retarded range. Nonverbal skills were stronger but still below average. Mrs. P’s capacity to learn and retain new information and to understand even modestly complex concepts is quite limited.

Because of Mrs. P’s long history of poly-substance abuse, inability to process information, and chronic back pain, we judge her to be at high risk for relapse. However, Mrs. P and her family are not interested in chemical dependence treatment.

This left us facing a difficult clinical situation. Mrs. P had a pattern of presenting to multiple physicians and eventually receiving narcotics. Her family provided transportation for her to these appointments but also was concerned about her drug use. With the patient and her family, we carefully outline Mrs. P’s treatment needs, including:

- medication monitoring by a psychiatrist after discharge

- a single, consistent primary care physician to manage her care

- a treatment plan shared by all clinicians involved in her care.

We review with Mrs. P and her family the benefits of behavioral approaches to chronic pain management. They agree to our recommendation that the family control Mrs. P’s medication supply. We discharge her on risperidone, 0.5 mg each morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and she is scheduled for follow-up with a local psychiatrist.

Related resource

- Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Vicodin, Lortab, others

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propoxyphene • Darvon, Darvocet, others

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. De Fazio S, Gallelli L, De Siena A, et al. Role of CYP3A5 in abnormal clearance methadone. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(6):893-897.

2. Ropper AH, Brown RH. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005.

3. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(1):99-103.

4. Eccles R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(1):10-14.

5. Wilson H, Woods D. Pseudoephedrine causing mania-like symptoms. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1148):86.-

6. Dalton R. Mixed bipolar disorder precipitated by pseudoephedrine hydrochloride. South Med J. 1990;83(1):64-65.

7. Mansi IA, Huang J. Rhabdomyolysis in response to weight-loss herbal medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:356-357.

8. Sandhu RS, Como JJ, Scalea TS. Renal failure and exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients taking performance-enhancing compounds. J Trauma. 2002;53:761-764.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

1. De Fazio S, Gallelli L, De Siena A, et al. Role of CYP3A5 in abnormal clearance methadone. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(6):893-897.

2. Ropper AH, Brown RH. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005.

3. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(1):99-103.

4. Eccles R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(1):10-14.

5. Wilson H, Woods D. Pseudoephedrine causing mania-like symptoms. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1148):86.-

6. Dalton R. Mixed bipolar disorder precipitated by pseudoephedrine hydrochloride. South Med J. 1990;83(1):64-65.

7. Mansi IA, Huang J. Rhabdomyolysis in response to weight-loss herbal medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:356-357.

8. Sandhu RS, Como JJ, Scalea TS. Renal failure and exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients taking performance-enhancing compounds. J Trauma. 2002;53:761-764.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

How to select pharmacologic treatments to manage recidivism risk in sex offenders

Sex offenders traditionally are managed by the criminal justice system, but psychiatrists are frequently called on to assess and treat these individuals. Part of the reason is the overlap of paraphilias (disorders of sexual preference) and sexual offending. Many sexual offenders do not meet DSM criteria for paraphilias,1 however, and individuals with paraphilias do not necessarily commit offenses or come into contact with the legal system.

As clinicians, we may need to assess and treat a wide range of sexual issues, from persons with paraphilias who are self-referred and have no legal involvement, to recurrent sexual offenders who are at a high risk of repeat offending. Successfully managing sex offenders includes psychological and pharmacologic interventions and possibly incarceration and post-incarceration surveillance. This article focuses on pharmacologic interventions for male sexual offenders.

Reducing sexual drive

Sex offending likely is the result of a complex interplay of environment and psychological and biologic factors. The biology of sexual function provides numerous targets for pharmacologic intervention, including:2

- endocrine factors, such as testosterone

- neurotransmitters, such as serotonin.

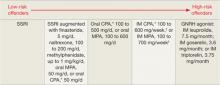

The use of pharmacologic treatments for sex offenders is off-label, and evidence is limited. In general, pharmacologic treatments are geared toward reducing sexual drive through nonhormonal or hormonal means (Table 1).3-5

Table 1: Pharmacologic treatment of male sex offenders: A risk-based approach

*Not available in the United States

†Some authors suggest administering this dosage once every 2 weeks

CPA: cyproterone acetate; GNRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone; IM: intramuscular; MPA: medroxyprogesterone acetate; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Source: References 3-5

Nonhormonal treatments

SSRIs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors act by blocking serotonin reuptake in the synaptic cleft. Soon after the first SSRIs were approved in 1988, reports appeared of SSRIs interfering with sexual functioning.6 This side effect quickly was exploited to assist the treatment of sexual offenders.7

The mechanism of action may include:8

- direct effects, such as general inhibition of sexual activity, reduced impulsiveness, and an effect on the hypothesized “obsessive-compulsive” nature of paraphilias9

- indirect reduction of testosterone.

A growing body of literature supports SSRIs’ effectiveness in treating paraphilias and sexual offenders. Greenberg7 reviewed case studies and open drug trials of nearly 200 patients receiving fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, or sertraline. Most studies showed response rates of 50% to 90%.10 Positive effects included decreases in:

- paraphiliac fantasies, urges, and sexual acts

- masturbation

- hypersexual activity.

Some studies reported a preferential decrease in paraphiliac interests with an increase in conventional sexual interests, although this may be related to placebo or halo effects—patients may have reported an increase in conventional interests because they noticed a decrease in paraphiliac interests. Negative side effects included decreased sexual desires, delayed ejaculation, decreased libido, and anorgasmia.

Adi et al11 completed a more rigorous literature evaluation that included 9 studies with a total of 225 patients receiving fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, or paroxetine. Eight studies showed benefits; however, Adi noted that this preliminary evidence was “far from conclusive.”

SSRIs generally are well tolerated and may be more appealing to patients than the “chemical castration” of hormonal treatments. Dosing is similar to that used in depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although most patients notice beneficial effects in 2 to 4 weeks, some notice the effect nearly immediately.

Naltrexone. An opioid antagonist thought to affect the CNS processes of pleasure and pain, naltrexone has been used to treat alcohol dependence and pathologic gambling. A few case studies12-14 and 1 study of 21 adolescent sex offenders15 have shown benefits in treating sexual offenders or paraphiliacs. Benefits were seen at 50 mg/d, with suggested dosing of 100 to 200 mg/d. Because data are very limited, consider naltrexone only on an individual basis or as a possible adjunctive treatment.

Psychostimulants. Methylphenidate was added to augment SSRI treatment in a study of 26 men with paraphilias or paraphilia-related disorders.16 Results included further significant decreases in total sexual outlets (orgasms per week) and average time spent per day in paraphilia and paraphilia-related behavior. These gains appeared to be independent of the presence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Again, because data are very limited, consider this strategy only on an individual basis or as a possible adjunctive treatment. Because sexual offenders have high rates of substance abuse,17 consider the potential for stimulant abuse.

Hormonal treatments

Because testosterone is required for healthy bone metabolism, the antiandrogen medications used in hormonal treatment can cause osteoporosis.18,19 Therefore, long-term antiandrogen treatment should include bone scans to monitor for osteopenia and osteoporosis. Some authors have suggested that monthly doses of 25 to 50 mg of testosterone could minimize this risk.20 Bisphosphonates, vitamin D, and calcium supplements at osteoporosis treatment levels might be helpful.18 Other common side effects of antiandrogen medications are listed in Table 2.

Finasteride is approved for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia and androgenetic alopecia. It works by preventing conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the type II isoenzyme.21 Serum DHT contributes to male sexual behavior and predicts frequency of orgasms in healthy volunteers.22 Although there have been no studies of finasteride in sex offenders, it may be more acceptable to patients than other hormonal treatments and have a theoretical benefit in reducing sexual drive. Clinically, some patients describe increased control over urges without substantial side effects. Because there is no evidence supporting finasteride use in sex offenders, consider this medication only on an individual basis or as a possible adjunctive treatment.

Cyproterone acetate (CPA) is a synthetic steroid that blocks androgen receptors.3,23 Some evidence supports its use in treating sex offenders,24 although this agent is not available in the United States. For more information about CPA, see Box.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), a derivative of progesterone, lowers serum testosterone by inhibiting its production through reducing pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH).24 The typical dose range for use in sex offenders is 100 to 600 mg/d orally or 100 to 700 mg IM every week,3 although some authors suggest giving similar doses every 2 weeks.4

Side effects of MPA include hypersomnia; neurasthenia; weight gain; hot flashes; gynecomastia; increased scalp hair; and decreased erections, ejaculate volume, spermatogenesis, and body and facial hair. The drug decreases testosterone levels by about 50%. Positive effects include reduced interest in and energy spent on pursuing sexual goals, but preservation of nondeviant sexual arousal.4

MPA has been shown to effectively decrease deviant sexual arousal and recidivism. In a study of 100 patients receiving MPA (average 250 mg IM every 2 weeks) for an average of 3 years, only 1 re-offended while taking MPA.4

In a 5-year follow-up study25 of 275 men, subjects were classified into high risk/treatment with MPA, 200 to 400 mg IM every 2 weeks, and low risk/nontreatment groups. A portion of the high risk/treatment group did not receive MPA. No sexual re-offenses occurred among high-risk subjects who received MPA, whereas the recidivism rate was 18% among high-risk subjects who did not receive MPA. Subjects in the low risk/nontreatment group had a recidivism rate of 15%, which suggests the need for more liberal use of antiandrogens. One major confounding factor was that subjects in the high risk/treatment group had to report every 2 weeks for injections; this may have resulted in closer follow-up, monitoring, and support, which may have contributed to lower recidivism.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) agonists. The terms gonadotropin-releasing hormone and luteinizing-releasing hormone are used interchangeably. Most body testosterone is produced and released by Leydig cells in the testes in response to stimulation by LH released by the pituitary gland. LH release is controlled by the pulsatile release of GNRH from the hypothalamus. GNRH agonists are high-potency analogs of GNRH that work by causing an initial surge of LH followed by down-regulation of gonadotroph cells, a drop in LH, and a drop in testosterone to castration levels.

The GNRH analogs leuprolide, goserelin, and triptorelin are used to treat paraphiliacs and sexual offenders.20 Leuprolide typically is dosed at 7.5 mg IM every month, 22.5 mg IM every 3 months, or 30 mg IM every 4 months. Goserelin is provided as a subcutaneous implant/depot injected as 3.6 mg every month or 10.8 mg every 3 months.

Triptorelin is FDA-approved as treatment for advanced prostate cancer. Triptorelin is given in depot formulation as 3.75 mg IM every month or in a long-acting form as 11.25 mg IM every 3 months.

When starting these medications, an initial surge of LH and testosterone can last up to 3 weeks.26 Theoretically, this could worsen paraphiliac interests. Many practitioners will use a testosterone blocker such as flutamide, 250 mg tid, for the initial weeks of treatment.

Side effects of the GNRH agonists are similar. Most patients initially experience hot flashes. A systemic literature review27 reported:

- weight gain

- perspiration

- gynecomastia

- urinary incontinence

- hot flashes

- decreased growth of facial and body hair

- asthenia

- erectile failure

- muscle tenderness

- frequent bone demineralization.

Rare cases of pituitary apoplexy (a clinical syndrome secondary to infarction of the pituitary gland) have been reported, possibly related to an underlying pituitary adenoma.28

In a literature review that totalled 118 patients,27 GNRH agonists significantly decreased erections, ejaculations, paraphiliac fantasies, and paraphiliac behavior. Patients also reported feeling more relaxed, and recidivism rates were low. Some patients who failed to respond to CPA and MPA responded to GNRH agonists. Subsequent studies found similar results.29,30

Cyproterone acetate (CPA), which is available in Canada and Europe, is a synthetic steroid with structure similar to that of progesterone. CPA blocks androgen receptors, which makes it antiandrogenic, progestational, and antigonadotrophic.a

Dosages for paraphilias range from 100 to 500 mg/d orally or 100 to 600 mg intramuscularly every 1 or 2 weeks. b

Once stabilized, some individuals can be maintained on very low doses, such as 12.5 to 50 mg/d. a Lower doses may be appropriate for individuals who are self-motivated for treatment and who reliably report their sexual interests.

CPA reduces testosterone by approximately 50%. Side effects include decreases in:

- erections

- ejaculate volume

- spermatogenesis.

Some patients experience hypersomnia, neurasthenia, weight gain, hot flashes, decreased body and facial hair, and increased scalp hair. About 20% of patients may experience gynecomastia, particularly at higher doses.

Evidence shows CPA reduces sexual arousal, activity, fantasy, and masturbation.a In a systematic review of 7 studies that included 127 patients, the re-offense rate averaged 6%.c This is significantly lower than the expected recidivism of approximately 13.4%.d

References

a. Rösler A, Witztum E. Pharmacotherapy of paraphilias in the next millennium. Behav Sci Law. 2000;18:43-56.

b. Finn DA, Beadles-Bohling AS, Beckley EH, et al. A new look at the 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12(1):53-76.

c. Mantzoros CS, Georgiadis EI, Trichopoulos D. Contribution of dihydrotestosterone to male sexual behaviour. BMJ. 1995;310(6990):1289-1291.

d. Hanson R, Bussiere MT. Predicting relapse: A meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1998;66:348-362.

Table 2

Common side effects of antiandrogen therapy

| Depression |

| Erectile dysfunction |

| Fatigue |

| Gynecomastia |

| Hot flashes |

| Hypertension |

| Low libido |

| Myalgia |

| Osteopenia |

| Osteoporosis |

| Sweating |

| Thromboembolism |

| Weight gain |

Monitoring

Laboratory investigations are recommended to monitor for side effects of antiandrogen medications (Table 3).19,27,31 Medical contraindications to rule out before initiating antiandrogen medications include:

- thromboembolic diseases

- liver disease

- bone demineralization disorders

- hypersensitivity to the drug.

Measure prolactin to rule out pituitary adenomas. Monitor serum testosterone because some patients will not experience testosterone suppression from GNRH agonists or other antiandrogens. Noncompliant patients could potentially reverse the effects of MPA and GNRH agonists by taking exogenous testosterone.

Table 3

Monitoring patients receiving antiandrogen medications

| Pre-therapy workup | Periodic monitoring |

|---|---|

| Endocrinology or internist consultation Bone scan Weight Blood pressure Electrocardiogram CBC, renal function, liver function, fasting glucose, and lipids LH, FSH, testosterone, prolactin | Monthly: testosterone for the first 6 months Every 6 months: testosterone, LH, FSH, prolactin, CBC, renal function, liver function, fasting glucose and lipids, weight, blood pressure Yearly: bone scan |

| CBC: complete blood count; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; LH: luteinizing hormone | |

| Source: References 19,27,31 | |

Medication selection

The goals of pharmacologic treatment of sex offenders are to:

- reduce sexual offending and victimization

- suppress sexual drive to a controllable level

- possibly preferentially eliminate deviant arousal/thoughts

- allow normal sexual relationships.

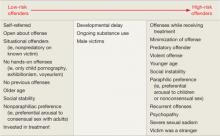

Gauging risk. In determining which pharmacologic treatment to offer a patient, first evaluate the individual’s risk for recidivism. Actuarial scales32,33 suggest that recidivism risk can be categorized, based on clinical factors (Table 4).4,25,34

In addition to statistical risk factors, several other factors affect medication selection. Self-referred individuals may be more reliable in taking oral medications than those referred by the courts. A developmentally delayed individual may be a poor candidate for oral medication, unless he resides in a group home setting where compliance can be assured. Efficacy also guides medication choice. Finally, some patients will be legally required to provide proof of compliance, which only IM medications provide.

Treatment. Based on clinical experience and available literature, Bradford5 created an algorithm to help clinicians select appropriate pharmacologic interventions. Although it has not been validated, this algorithm provides a reasonable starting place.

In general, start treatment with an SSRI for low-risk individuals (Table 1).3-5 If this strategy is insufficient, consider augmentation with methylphenidate, naltrexone, or finasteride.

The next step would be to add oral MPA or CPA, 50 mg/d, which would partially inhibit testosterone and may allow some normal sexual functioning.4,23 Higher-dose oral MPA or CPA would be tried next. For higher-risk individuals or treatment failures, IM MPA or CPA would be offered next, followed by a GNRH agonist. For individuals at highest risk for re-offending, combinations of agents may be indicated.

This simple strategy is appealing, but in reality, treatment should be individualized. Choose medications based on the patient’s risk, wishes, and the previously mentioned clinical factors.

Table 4: Will my patient commit another sexual offense? Evaluating risk

Source: References 4,25,34Related resources

- Krueger RB, Kaplan MS. The paraphilic and hypersexual disorders: an overview. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7:391-403.

- Krueger RB, Kaplan MS. Behavioral and psychopharmacological treatment of the paraphilic and hypersexual disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2002;8:21-32.

- Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers. www.atsa.com.

Drug brand names

- Cyproterone acetate • Androcur

- Finasteride • Propecia, Proscar

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Flutamide • Eulexin

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Goserelin • Zoladex

- Leuprolide • Eligard, Lupron

- Medroxyprogesterone acetate • Depo-Provera, Provera

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Triptorelin • Trelstar Depot

Disclosure

Dr. Booth reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnoses in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

2. Meston CM, Frohlich PF. The neurobiology of sexual function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1012-1030.

3. Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ, eds. Clinical handbook of psychotropic drugs. 16th ed. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; 2006:222–225.

4. Maletzky B. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to assist in the treatment of sexual offenders. Annals of Sex Research. 1991;4:117-129.

5. Bradford JM. The neurobiology, neuropharmacology, and pharmacological treatment of the paraphilias and compulsive sexual behaviour. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(1):26-34.

6. Baldwin DS. Sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3(5):457-470.

7. Greenberg DM, Bradford JMW. Treatment of the paraphilic disorders: a review of the role of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Sex Abuse. 1997;9(4):349-360.

8. Hill A, Briken P, Kraus C, et al. Differential pharmacological treatment of paraphilias and sex offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2003;47(4):407-421.

9. Bradford JMW. The paraphilias, obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder, and the treatment of sexually deviant behaviour. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(3):209-219.

10. Krueger RB, Kaplan MS. Behavioral and psychopharmacological treatment of the paraphilic and hypersexual disorders. J Psychiatr Prac. 2002;8(1):21-32.

11. Adi Y, Ashcroft D, Browne K, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-consequences of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of sex offenders. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(28):1-66.

12. Raymond NC, Grant JE, Kim SW, et al. Treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour with naltrexone and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: two case studies. Int Clin Psychopharm. 2002;17(4):201-205.

13. Grant JE, Kim SW. A case of kleptomania and compulsive sexual behavior treated with naltrexone. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13(4):229-231.

14. Sandyk R. Naltrexone suppresses abnormal sexual behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. Int J Neurosci. 1988;43(1-2):107-110.

15. Ryback RS. Naltrexone in the treatment of adolescent sexual offenders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):982-986.

16. Kafka M, Hennen J. Psychostimulant augmentation during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in men with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders: a case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(9):664-670.

17. Langstrom N, Sjostedt G, Grann M. Psychiatric disorders and recidivism in sexual offenders. Sex Abuse. 2004;16(2):139-150.

18. Smith MR. Osteoporosis during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;60(3 suppl 1):79-85.

19. Grasswick LJ, Bradford JM. Osteoporosis associated with the treatment of paraphilias: a clinical review of seven case reports. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48:849-855.

20. Rösler A, Witztum E. Pharmacotherapy of paraphilias in the next millennium. Behav Sci Law. 2000;18:43-56.

21. Finn DA, Beadles-Bohling AS, Beckley EH, et al. A new look at the 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12(1):53-76.

22. Mantzoros CS, Georgiadis EI, Trichopoulos D. Contribution of dihydrotestosterone to male sexual behaviour. BMJ. 1995;310(6990):1289-1291.

23. Bradford JMW, Pawlak A. Double-blind placebo crossover study of cyproterone acetate in the treatment of the paraphilias. Arch Sex Behav. 1993;22(5):383-402.

24. Meyer WJ, Cole CM. Physical and chemical castration of sex offenders: a review. J Offender Rehab. 1997;25(3/4):1-18.

25. Maletzky BM, Tolan A, McFarland B. The Oregon depoProvera program: a five-year follow-up. Sex Abuse. 2006;18:303-316.

26. van Poppel H, Nilsson S. Testosterone surge: rationale for gonadotropin-releasing hormone blockers? Urology. 2008;71:1001-1006.

27. Briken P, Hill A, Berner W. Pharmacotherapy of paraphilias with long-acting agonists of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:890-897.

28. Blaut K, Winiewski P, Syrenicz A, et al. Apoplexy of clinically silent pituitary adenoma during prostate cancer treatment with LHRH analog. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27(5):569-572.

29. Schober JM, Kuhn PJ, Kovacs P, et al. Leuprolide acetate suppresses pedophilic urges and arousability. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34(6):691-705.

30. Ösler A, Witztum E. Treatment of men with paraphilia with a long-acting analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:416-422.

31. Reilly DR, Delva NJ, Hudson RW. Protocols for the use of cyproterone, medroxyprogesterone, and leuprolide in the treatment of paraphilia. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:559-563.

32. Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998.

33. Epperson DL, Kaul JD, Huot SJ, et al. Minnesota Sex Offender Screening Tool–revised (MnSOST-R). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Corrections; 1998.

34. Bradford JMW. The treatment of sexual deviation using a pharmacological approach. J Sex Res. 2000;37(3):248-257.

Sex offenders traditionally are managed by the criminal justice system, but psychiatrists are frequently called on to assess and treat these individuals. Part of the reason is the overlap of paraphilias (disorders of sexual preference) and sexual offending. Many sexual offenders do not meet DSM criteria for paraphilias,1 however, and individuals with paraphilias do not necessarily commit offenses or come into contact with the legal system.

As clinicians, we may need to assess and treat a wide range of sexual issues, from persons with paraphilias who are self-referred and have no legal involvement, to recurrent sexual offenders who are at a high risk of repeat offending. Successfully managing sex offenders includes psychological and pharmacologic interventions and possibly incarceration and post-incarceration surveillance. This article focuses on pharmacologic interventions for male sexual offenders.

Reducing sexual drive

Sex offending likely is the result of a complex interplay of environment and psychological and biologic factors. The biology of sexual function provides numerous targets for pharmacologic intervention, including:2

- endocrine factors, such as testosterone

- neurotransmitters, such as serotonin.

The use of pharmacologic treatments for sex offenders is off-label, and evidence is limited. In general, pharmacologic treatments are geared toward reducing sexual drive through nonhormonal or hormonal means (Table 1).3-5

Table 1: Pharmacologic treatment of male sex offenders: A risk-based approach