User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Drs. Tandon and Constantine reply

We thank Dr. Helmuth and the principal investigators of CATIE for their interest in our article and the opportunity to further clarify a key learning point from CATIE.

Dr. Helmuth acknowledges our balanced review but suggests that cost and metabolic side effects should be considered along with lower EPS liability in selecting antipsychotic therapy. We agree. Avoiding EPS while obtaining a good antipsychotic effect is one key consideration in providing optimal antipsychotic therapy. Other adverse effects, patient preference, cost, and other factors are all important considerations in this complex process of individually optimizing antipsychotic treatment.

The CATIE investigators agree with our interpretation of the study’s principal findings. They take exception, however, to our suggestion that CATIE’s finding of no FGA-SGA difference in EPS and TD may be related to its relatively low assay sensitivity to detect such differences because the sample studied was at low risk for EPS and TD.

While accepting our description of the study sample as accurate, they disagree that it was at low risk for EPS and TD. Patients who have been ill for 16 years and received antipsychotic treatment for an average of 14 years without developing TD or severe EPS (as in CATIE) are by definition at low risk for EPS and TD.

We agree that patients without current TD and who are at risk for developing it comprise the best study population to investigate differential risk for TD; however, patients who have not developed it, despite 14 years of antipsychotic therapy, are at very low risk for developing it at all. First-episode patients without prior antipsychotic exposure would be an optimal study population, but such patients were excluded from CATIE.

Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues do not disagree with any of the other assertions in our article; they are, however, critical of “numerous factual errors in other published critiques of CATIE.” We cannot address such supposed inaccuracies, which are best taken up with authors of those commentaries.

To extract maximum value from this important initiative, we must better understand CATIE’s findings in the context of its study design and the results of other relevant studies. Neither mischaracterization nor overinterpretation of CATIE’s findings helps clinicians, patients, and policy-makers.

The essence of our article was that avoiding motor, cognitive, and affective EPS due to unmodulated dopamine blockade is the key to realizing the “atypical benefits” of a broader spectrum of efficacy and lower risk of TD during antipsychotic therapy. Neither Dr. Helmuth nor Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues appear to disagree with this assertion. Avoiding broadly defined EPS appears to be critical to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with SGAs and FGAs. The lower risk of TD observed with SGAs also appears to be related to the greater ease with which they can provide an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS.

Rajiv Tandon, MD

Adjunct professor of psychiatry

University of Florida, Tallahassee

Robert Constantine, PhD

Research associate professor

University of South Florida, Tampa

We thank Dr. Helmuth and the principal investigators of CATIE for their interest in our article and the opportunity to further clarify a key learning point from CATIE.

Dr. Helmuth acknowledges our balanced review but suggests that cost and metabolic side effects should be considered along with lower EPS liability in selecting antipsychotic therapy. We agree. Avoiding EPS while obtaining a good antipsychotic effect is one key consideration in providing optimal antipsychotic therapy. Other adverse effects, patient preference, cost, and other factors are all important considerations in this complex process of individually optimizing antipsychotic treatment.

The CATIE investigators agree with our interpretation of the study’s principal findings. They take exception, however, to our suggestion that CATIE’s finding of no FGA-SGA difference in EPS and TD may be related to its relatively low assay sensitivity to detect such differences because the sample studied was at low risk for EPS and TD.

While accepting our description of the study sample as accurate, they disagree that it was at low risk for EPS and TD. Patients who have been ill for 16 years and received antipsychotic treatment for an average of 14 years without developing TD or severe EPS (as in CATIE) are by definition at low risk for EPS and TD.

We agree that patients without current TD and who are at risk for developing it comprise the best study population to investigate differential risk for TD; however, patients who have not developed it, despite 14 years of antipsychotic therapy, are at very low risk for developing it at all. First-episode patients without prior antipsychotic exposure would be an optimal study population, but such patients were excluded from CATIE.

Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues do not disagree with any of the other assertions in our article; they are, however, critical of “numerous factual errors in other published critiques of CATIE.” We cannot address such supposed inaccuracies, which are best taken up with authors of those commentaries.

To extract maximum value from this important initiative, we must better understand CATIE’s findings in the context of its study design and the results of other relevant studies. Neither mischaracterization nor overinterpretation of CATIE’s findings helps clinicians, patients, and policy-makers.

The essence of our article was that avoiding motor, cognitive, and affective EPS due to unmodulated dopamine blockade is the key to realizing the “atypical benefits” of a broader spectrum of efficacy and lower risk of TD during antipsychotic therapy. Neither Dr. Helmuth nor Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues appear to disagree with this assertion. Avoiding broadly defined EPS appears to be critical to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with SGAs and FGAs. The lower risk of TD observed with SGAs also appears to be related to the greater ease with which they can provide an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS.

Rajiv Tandon, MD

Adjunct professor of psychiatry

University of Florida, Tallahassee

Robert Constantine, PhD

Research associate professor

University of South Florida, Tampa

We thank Dr. Helmuth and the principal investigators of CATIE for their interest in our article and the opportunity to further clarify a key learning point from CATIE.

Dr. Helmuth acknowledges our balanced review but suggests that cost and metabolic side effects should be considered along with lower EPS liability in selecting antipsychotic therapy. We agree. Avoiding EPS while obtaining a good antipsychotic effect is one key consideration in providing optimal antipsychotic therapy. Other adverse effects, patient preference, cost, and other factors are all important considerations in this complex process of individually optimizing antipsychotic treatment.

The CATIE investigators agree with our interpretation of the study’s principal findings. They take exception, however, to our suggestion that CATIE’s finding of no FGA-SGA difference in EPS and TD may be related to its relatively low assay sensitivity to detect such differences because the sample studied was at low risk for EPS and TD.

While accepting our description of the study sample as accurate, they disagree that it was at low risk for EPS and TD. Patients who have been ill for 16 years and received antipsychotic treatment for an average of 14 years without developing TD or severe EPS (as in CATIE) are by definition at low risk for EPS and TD.

We agree that patients without current TD and who are at risk for developing it comprise the best study population to investigate differential risk for TD; however, patients who have not developed it, despite 14 years of antipsychotic therapy, are at very low risk for developing it at all. First-episode patients without prior antipsychotic exposure would be an optimal study population, but such patients were excluded from CATIE.

Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues do not disagree with any of the other assertions in our article; they are, however, critical of “numerous factual errors in other published critiques of CATIE.” We cannot address such supposed inaccuracies, which are best taken up with authors of those commentaries.

To extract maximum value from this important initiative, we must better understand CATIE’s findings in the context of its study design and the results of other relevant studies. Neither mischaracterization nor overinterpretation of CATIE’s findings helps clinicians, patients, and policy-makers.

The essence of our article was that avoiding motor, cognitive, and affective EPS due to unmodulated dopamine blockade is the key to realizing the “atypical benefits” of a broader spectrum of efficacy and lower risk of TD during antipsychotic therapy. Neither Dr. Helmuth nor Drs. Rosenheck and colleagues appear to disagree with this assertion. Avoiding broadly defined EPS appears to be critical to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with SGAs and FGAs. The lower risk of TD observed with SGAs also appears to be related to the greater ease with which they can provide an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS.

Rajiv Tandon, MD

Adjunct professor of psychiatry

University of Florida, Tallahassee

Robert Constantine, PhD

Research associate professor

University of South Florida, Tampa

Study samples key to assessing risk

We agree with Drs. Tandon’s and Constantine’s explanation of the difference between the results of the CATIE trial1 and previous studies—specifically that CATIE showed no differences between 4 SGAs and an intermediate potency FGA on EPS and tardive dyskinesia (TD). As the authors suggest, these results are best explained by the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the comparator in pre-CATIE studies, which magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs. A recent study has further suggested that in most of these trials the doses of haloperidol were above FDA-approved levels,2 and few, if any, used prophylactic anticholinergics, further biasing the comparisons.

Drs. Tandon and Constantine further assert that the CATIE sample was at less risk of EPS or TD than previous samples because it excluded first-episode patients and those with TD and addressed a population that had used medications for 14 years without a history of adverse effects. CATIE—like any other ethical human investigation—excluded patients if they had well-documented, drug-related, adverse reactions to any of the proposed treatments.

Many, if not most, FDA registration trials (the source of most data on EPS with SGAs) excluded all patients with previous exposure to the new SGA drugs they tested but did not apply this criterion to patients exposed to older drugs. Thus the trials were more likely to include patients who would have responded poorly to FGAs than those who would have responded poorly to SGAs. Others have recognized that this reduces the validity of such FGA-SGA comparisons.3

Table

Study populations of SGA-FGA comparison trials

| Age | Age at onset | Duration of illness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATIE (Lieberman et al, 2005) | 40 | 24 | 16 |

| Olanzapine (Beasley et al, 1998) | 38.6 | 23.9 | 14.7 |

| Risperidone (Csernansky et al, 2002) | 40.3 | 24.4 | 15.9 |

| Amisulpride (Rein and L’Heritier, 1999) | 36 | na | na |

| Ziprasidone (Arato et al, 2002) | 50 | na | na |

| Risperidone (Marder et al, 1994) | 37.4 | 21.7 | 15.7 |

| Risperidone (Marder, 2003) | 43.5 | na | na |

| Aripiprazole (Kane et al, 2002) | 38.6 | 22.3 | 16.3 |

In the Table we present data comparing population characteristics from CATIE, from a meta-analysis that identified all 4 published controlled trials that have examined TD outcomes in FGA and SGAs,4 and from several other well-known comparable trials. The CATIE sample was similar to patients who participated in the other trials in average age, age of onset, and duration of illness.

Beasley et al5 similarly presented an analysis that excluded patients without TD at baseline, which we believe is the optimal population to use when evaluating medication-related risk for TD. CATIE is the only study that conducted a sound randomization comparing FGAs and SGAs in patients without current TD who are at risk for it, and—more than other studies—used an unbiased and thus more informative comparator.

Unfortunately there have been numerous factual errors in published critiques of CATIE. In one, CATIE was deemed disappointing6 because it had “a large percentage of discontinuations for all causes,” but the data presented for comparison were from a 28-week study7—less than half as long as the 72-week CATIE trial. CATIE, in fact, had better overall follow-up rates than the cited study at 28 weeks and also had better long-term follow-up rates than either the paper by Beasley et al5 or by Csernansky et al8—the most often cited “long-term” studies comparing FGAs and SGAs on TD.

Another commentary, like that of Drs. Tandon and Constantine, described CATIE patients as having more chronic illness that those in other trials, with “24 years since first treatment,”9 a misreading of the average age of first onset (which was 24) as if it was the average duration of illness (which was 16 years).

Many commentators have further asserted that because patients with TD at baseline “were not randomly assigned to conventional drugs” the comparison of either outcomes or TD risk was invalid.6,9 As noted above, comparison of side effect risk is properly tested by trials involving patients without that risk at onset.

CATIE represented a major investment of public dollars to learn more about antipsychotic medications. Erroneous critiques needlessly mislead the professional community about what can be learned from this initiative.

The CATIE investigators

Robert Rosenheck, MD, New Haven, CT

T. Scott Stroup, MD, MPH, Chapel Hill, NC

Richard SE Keefe, PhD, Durham, NC

Joseph McEvoy, MD, Durham, NC

Marvin Swartz, MD, Durham, NC

Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, New York, NY

1. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

2. Hugenholtz GWK, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparitor in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(6):897-903.

3. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:255-62.

4. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

5. Beasley CM, Dellva MA, Tamura RN, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of the incidence of tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during long-term treatment with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:23-30.

6. Meltzer HY, Bobo WV. Interpreting the efficacy findings in the CATIE study: what clinicians should know. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):14-24.

7. Breier A, Berg PH, Thakore JH, et al. Olanzapine versus ziprasidone: results of a 28-week double blind study in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(10):1879-87.

8. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:16-22.

9. Kane JM. Commentary on the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(5):831-2.

We agree with Drs. Tandon’s and Constantine’s explanation of the difference between the results of the CATIE trial1 and previous studies—specifically that CATIE showed no differences between 4 SGAs and an intermediate potency FGA on EPS and tardive dyskinesia (TD). As the authors suggest, these results are best explained by the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the comparator in pre-CATIE studies, which magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs. A recent study has further suggested that in most of these trials the doses of haloperidol were above FDA-approved levels,2 and few, if any, used prophylactic anticholinergics, further biasing the comparisons.

Drs. Tandon and Constantine further assert that the CATIE sample was at less risk of EPS or TD than previous samples because it excluded first-episode patients and those with TD and addressed a population that had used medications for 14 years without a history of adverse effects. CATIE—like any other ethical human investigation—excluded patients if they had well-documented, drug-related, adverse reactions to any of the proposed treatments.

Many, if not most, FDA registration trials (the source of most data on EPS with SGAs) excluded all patients with previous exposure to the new SGA drugs they tested but did not apply this criterion to patients exposed to older drugs. Thus the trials were more likely to include patients who would have responded poorly to FGAs than those who would have responded poorly to SGAs. Others have recognized that this reduces the validity of such FGA-SGA comparisons.3

Table

Study populations of SGA-FGA comparison trials

| Age | Age at onset | Duration of illness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATIE (Lieberman et al, 2005) | 40 | 24 | 16 |

| Olanzapine (Beasley et al, 1998) | 38.6 | 23.9 | 14.7 |

| Risperidone (Csernansky et al, 2002) | 40.3 | 24.4 | 15.9 |

| Amisulpride (Rein and L’Heritier, 1999) | 36 | na | na |

| Ziprasidone (Arato et al, 2002) | 50 | na | na |

| Risperidone (Marder et al, 1994) | 37.4 | 21.7 | 15.7 |

| Risperidone (Marder, 2003) | 43.5 | na | na |

| Aripiprazole (Kane et al, 2002) | 38.6 | 22.3 | 16.3 |

In the Table we present data comparing population characteristics from CATIE, from a meta-analysis that identified all 4 published controlled trials that have examined TD outcomes in FGA and SGAs,4 and from several other well-known comparable trials. The CATIE sample was similar to patients who participated in the other trials in average age, age of onset, and duration of illness.

Beasley et al5 similarly presented an analysis that excluded patients without TD at baseline, which we believe is the optimal population to use when evaluating medication-related risk for TD. CATIE is the only study that conducted a sound randomization comparing FGAs and SGAs in patients without current TD who are at risk for it, and—more than other studies—used an unbiased and thus more informative comparator.

Unfortunately there have been numerous factual errors in published critiques of CATIE. In one, CATIE was deemed disappointing6 because it had “a large percentage of discontinuations for all causes,” but the data presented for comparison were from a 28-week study7—less than half as long as the 72-week CATIE trial. CATIE, in fact, had better overall follow-up rates than the cited study at 28 weeks and also had better long-term follow-up rates than either the paper by Beasley et al5 or by Csernansky et al8—the most often cited “long-term” studies comparing FGAs and SGAs on TD.

Another commentary, like that of Drs. Tandon and Constantine, described CATIE patients as having more chronic illness that those in other trials, with “24 years since first treatment,”9 a misreading of the average age of first onset (which was 24) as if it was the average duration of illness (which was 16 years).

Many commentators have further asserted that because patients with TD at baseline “were not randomly assigned to conventional drugs” the comparison of either outcomes or TD risk was invalid.6,9 As noted above, comparison of side effect risk is properly tested by trials involving patients without that risk at onset.

CATIE represented a major investment of public dollars to learn more about antipsychotic medications. Erroneous critiques needlessly mislead the professional community about what can be learned from this initiative.

The CATIE investigators

Robert Rosenheck, MD, New Haven, CT

T. Scott Stroup, MD, MPH, Chapel Hill, NC

Richard SE Keefe, PhD, Durham, NC

Joseph McEvoy, MD, Durham, NC

Marvin Swartz, MD, Durham, NC

Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, New York, NY

We agree with Drs. Tandon’s and Constantine’s explanation of the difference between the results of the CATIE trial1 and previous studies—specifically that CATIE showed no differences between 4 SGAs and an intermediate potency FGA on EPS and tardive dyskinesia (TD). As the authors suggest, these results are best explained by the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the comparator in pre-CATIE studies, which magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs. A recent study has further suggested that in most of these trials the doses of haloperidol were above FDA-approved levels,2 and few, if any, used prophylactic anticholinergics, further biasing the comparisons.

Drs. Tandon and Constantine further assert that the CATIE sample was at less risk of EPS or TD than previous samples because it excluded first-episode patients and those with TD and addressed a population that had used medications for 14 years without a history of adverse effects. CATIE—like any other ethical human investigation—excluded patients if they had well-documented, drug-related, adverse reactions to any of the proposed treatments.

Many, if not most, FDA registration trials (the source of most data on EPS with SGAs) excluded all patients with previous exposure to the new SGA drugs they tested but did not apply this criterion to patients exposed to older drugs. Thus the trials were more likely to include patients who would have responded poorly to FGAs than those who would have responded poorly to SGAs. Others have recognized that this reduces the validity of such FGA-SGA comparisons.3

Table

Study populations of SGA-FGA comparison trials

| Age | Age at onset | Duration of illness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATIE (Lieberman et al, 2005) | 40 | 24 | 16 |

| Olanzapine (Beasley et al, 1998) | 38.6 | 23.9 | 14.7 |

| Risperidone (Csernansky et al, 2002) | 40.3 | 24.4 | 15.9 |

| Amisulpride (Rein and L’Heritier, 1999) | 36 | na | na |

| Ziprasidone (Arato et al, 2002) | 50 | na | na |

| Risperidone (Marder et al, 1994) | 37.4 | 21.7 | 15.7 |

| Risperidone (Marder, 2003) | 43.5 | na | na |

| Aripiprazole (Kane et al, 2002) | 38.6 | 22.3 | 16.3 |

In the Table we present data comparing population characteristics from CATIE, from a meta-analysis that identified all 4 published controlled trials that have examined TD outcomes in FGA and SGAs,4 and from several other well-known comparable trials. The CATIE sample was similar to patients who participated in the other trials in average age, age of onset, and duration of illness.

Beasley et al5 similarly presented an analysis that excluded patients without TD at baseline, which we believe is the optimal population to use when evaluating medication-related risk for TD. CATIE is the only study that conducted a sound randomization comparing FGAs and SGAs in patients without current TD who are at risk for it, and—more than other studies—used an unbiased and thus more informative comparator.

Unfortunately there have been numerous factual errors in published critiques of CATIE. In one, CATIE was deemed disappointing6 because it had “a large percentage of discontinuations for all causes,” but the data presented for comparison were from a 28-week study7—less than half as long as the 72-week CATIE trial. CATIE, in fact, had better overall follow-up rates than the cited study at 28 weeks and also had better long-term follow-up rates than either the paper by Beasley et al5 or by Csernansky et al8—the most often cited “long-term” studies comparing FGAs and SGAs on TD.

Another commentary, like that of Drs. Tandon and Constantine, described CATIE patients as having more chronic illness that those in other trials, with “24 years since first treatment,”9 a misreading of the average age of first onset (which was 24) as if it was the average duration of illness (which was 16 years).

Many commentators have further asserted that because patients with TD at baseline “were not randomly assigned to conventional drugs” the comparison of either outcomes or TD risk was invalid.6,9 As noted above, comparison of side effect risk is properly tested by trials involving patients without that risk at onset.

CATIE represented a major investment of public dollars to learn more about antipsychotic medications. Erroneous critiques needlessly mislead the professional community about what can be learned from this initiative.

The CATIE investigators

Robert Rosenheck, MD, New Haven, CT

T. Scott Stroup, MD, MPH, Chapel Hill, NC

Richard SE Keefe, PhD, Durham, NC

Joseph McEvoy, MD, Durham, NC

Marvin Swartz, MD, Durham, NC

Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, New York, NY

1. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

2. Hugenholtz GWK, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparitor in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(6):897-903.

3. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:255-62.

4. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

5. Beasley CM, Dellva MA, Tamura RN, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of the incidence of tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during long-term treatment with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:23-30.

6. Meltzer HY, Bobo WV. Interpreting the efficacy findings in the CATIE study: what clinicians should know. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):14-24.

7. Breier A, Berg PH, Thakore JH, et al. Olanzapine versus ziprasidone: results of a 28-week double blind study in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(10):1879-87.

8. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:16-22.

9. Kane JM. Commentary on the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(5):831-2.

1. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

2. Hugenholtz GWK, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparitor in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(6):897-903.

3. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:255-62.

4. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

5. Beasley CM, Dellva MA, Tamura RN, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of the incidence of tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during long-term treatment with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:23-30.

6. Meltzer HY, Bobo WV. Interpreting the efficacy findings in the CATIE study: what clinicians should know. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):14-24.

7. Breier A, Berg PH, Thakore JH, et al. Olanzapine versus ziprasidone: results of a 28-week double blind study in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(10):1879-87.

8. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:16-22.

9. Kane JM. Commentary on the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(5):831-2.

Continued concerns about SGAs

Although the article “Avoiding EPS is key to realizing ‘atypical’ benefits,” by Drs. Rajiv Tandon and Robert J. Constantine (Current Psychiatry, November 2006), is more balanced than some reviews of the CATIE findings, it emphasized avoiding extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) while ignoring two other features that are important when choosing an antipsychotic.

The first is the propensity for causing weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. The CATIE phase 1 investigation showed that second-generation antipsychotics (SGA)—especially olanzapine—are much more likely to cause these health-threatening complications compared with the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) perphenazine.

The second consideration is cost. I am aware of economic arguments in favor of SGAs, especially if they prevent hospitalizations. However, in light of CATIE and the British CUtLASS 1 studies, it is unconscionable to not consider the huge difference in cost between SGAs and FGAs. Recent reports indicate that SGAs continue to outpace almost all other medications in price increases. This adds to society’s health-cost burden and creates a cruel inequity for those without prescription coverage.

It is an oversimplification of our clinical duty to refer to avoiding EPS as the “key” to antipsychotic treatment. We can only wish it were that simple.

Dennis Helmuth, MD, PhD

Clinical associate professor of psychiatry

Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine,

Wooster, OH

Although the article “Avoiding EPS is key to realizing ‘atypical’ benefits,” by Drs. Rajiv Tandon and Robert J. Constantine (Current Psychiatry, November 2006), is more balanced than some reviews of the CATIE findings, it emphasized avoiding extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) while ignoring two other features that are important when choosing an antipsychotic.

The first is the propensity for causing weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. The CATIE phase 1 investigation showed that second-generation antipsychotics (SGA)—especially olanzapine—are much more likely to cause these health-threatening complications compared with the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) perphenazine.

The second consideration is cost. I am aware of economic arguments in favor of SGAs, especially if they prevent hospitalizations. However, in light of CATIE and the British CUtLASS 1 studies, it is unconscionable to not consider the huge difference in cost between SGAs and FGAs. Recent reports indicate that SGAs continue to outpace almost all other medications in price increases. This adds to society’s health-cost burden and creates a cruel inequity for those without prescription coverage.

It is an oversimplification of our clinical duty to refer to avoiding EPS as the “key” to antipsychotic treatment. We can only wish it were that simple.

Dennis Helmuth, MD, PhD

Clinical associate professor of psychiatry

Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine,

Wooster, OH

Although the article “Avoiding EPS is key to realizing ‘atypical’ benefits,” by Drs. Rajiv Tandon and Robert J. Constantine (Current Psychiatry, November 2006), is more balanced than some reviews of the CATIE findings, it emphasized avoiding extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) while ignoring two other features that are important when choosing an antipsychotic.

The first is the propensity for causing weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. The CATIE phase 1 investigation showed that second-generation antipsychotics (SGA)—especially olanzapine—are much more likely to cause these health-threatening complications compared with the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) perphenazine.

The second consideration is cost. I am aware of economic arguments in favor of SGAs, especially if they prevent hospitalizations. However, in light of CATIE and the British CUtLASS 1 studies, it is unconscionable to not consider the huge difference in cost between SGAs and FGAs. Recent reports indicate that SGAs continue to outpace almost all other medications in price increases. This adds to society’s health-cost burden and creates a cruel inequity for those without prescription coverage.

It is an oversimplification of our clinical duty to refer to avoiding EPS as the “key” to antipsychotic treatment. We can only wish it were that simple.

Dennis Helmuth, MD, PhD

Clinical associate professor of psychiatry

Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine,

Wooster, OH

Safety first

Thank you for the interview, “Protect yourself against patient assault,” and the accompanying reprint of Dr. John Battaglia’s article “Is this patient dangerous?” (Current Psychiatry, November 2006). Both give sound clinical guidelines for psychiatrist safety without being insensitive or “blaming the victim” in the case of Dr. Wayne Fenton’s tragic death allegedly at the hands of a patient. Although implicit, however, the need to develop and maintain appropriate boundaries needs to be more explicit and discussed.

From what we know, Dr. Fenton saw the patient in his office on a weekend with no one else present other than the patient’s father, who waited outside. One eulogy said that Dr. Fenton helped install a carpet in a different patient’s residence after the patient was released from the hospital. Both examples surely are instances of going “the extra mile” to help troubled patients, and Dr. Fenton was known as a master clinician who received some of the most difficult cases.

On the other hand, customary boundaries regarding how and where to see patients were not taken. Perhaps Dr. Fenton thought the rewards of breaking these boundaries outweighed the risks. Nevertheless, development and maintenance of boundaries should be undertaken as one way to ensure safety. When making exceptions, extra precaution should be taken.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee

Dr. Battaglia responds

I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Moffic’s points about the need to take extra precautions when going outside customary boundaries. However, our discipline treads in muddy waters on the issue of what is appropriate when working outside such boundaries.

The extremes of sexual or financial exploitation are clear, but otherwise the entire spectrum of interaction between patient and clinician can be appropriate under certain circumstances. For example, in my work with the Madison (WI) Program of Assertive Community Treatment, I often see patients in their homes, help them with grocery shopping, or assist them with other daily tasks. Although these behaviors do not fit an office model, they are not uncommon in community work and do not necessarily break boundaries.

John Battaglia, MD

Program of Assertive Community Treatment

Associate clinical professor of psychiatry

University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School

Thank you for the interview, “Protect yourself against patient assault,” and the accompanying reprint of Dr. John Battaglia’s article “Is this patient dangerous?” (Current Psychiatry, November 2006). Both give sound clinical guidelines for psychiatrist safety without being insensitive or “blaming the victim” in the case of Dr. Wayne Fenton’s tragic death allegedly at the hands of a patient. Although implicit, however, the need to develop and maintain appropriate boundaries needs to be more explicit and discussed.

From what we know, Dr. Fenton saw the patient in his office on a weekend with no one else present other than the patient’s father, who waited outside. One eulogy said that Dr. Fenton helped install a carpet in a different patient’s residence after the patient was released from the hospital. Both examples surely are instances of going “the extra mile” to help troubled patients, and Dr. Fenton was known as a master clinician who received some of the most difficult cases.

On the other hand, customary boundaries regarding how and where to see patients were not taken. Perhaps Dr. Fenton thought the rewards of breaking these boundaries outweighed the risks. Nevertheless, development and maintenance of boundaries should be undertaken as one way to ensure safety. When making exceptions, extra precaution should be taken.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee

Dr. Battaglia responds

I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Moffic’s points about the need to take extra precautions when going outside customary boundaries. However, our discipline treads in muddy waters on the issue of what is appropriate when working outside such boundaries.

The extremes of sexual or financial exploitation are clear, but otherwise the entire spectrum of interaction between patient and clinician can be appropriate under certain circumstances. For example, in my work with the Madison (WI) Program of Assertive Community Treatment, I often see patients in their homes, help them with grocery shopping, or assist them with other daily tasks. Although these behaviors do not fit an office model, they are not uncommon in community work and do not necessarily break boundaries.

John Battaglia, MD

Program of Assertive Community Treatment

Associate clinical professor of psychiatry

University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School

Thank you for the interview, “Protect yourself against patient assault,” and the accompanying reprint of Dr. John Battaglia’s article “Is this patient dangerous?” (Current Psychiatry, November 2006). Both give sound clinical guidelines for psychiatrist safety without being insensitive or “blaming the victim” in the case of Dr. Wayne Fenton’s tragic death allegedly at the hands of a patient. Although implicit, however, the need to develop and maintain appropriate boundaries needs to be more explicit and discussed.

From what we know, Dr. Fenton saw the patient in his office on a weekend with no one else present other than the patient’s father, who waited outside. One eulogy said that Dr. Fenton helped install a carpet in a different patient’s residence after the patient was released from the hospital. Both examples surely are instances of going “the extra mile” to help troubled patients, and Dr. Fenton was known as a master clinician who received some of the most difficult cases.

On the other hand, customary boundaries regarding how and where to see patients were not taken. Perhaps Dr. Fenton thought the rewards of breaking these boundaries outweighed the risks. Nevertheless, development and maintenance of boundaries should be undertaken as one way to ensure safety. When making exceptions, extra precaution should be taken.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee

Dr. Battaglia responds

I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Moffic’s points about the need to take extra precautions when going outside customary boundaries. However, our discipline treads in muddy waters on the issue of what is appropriate when working outside such boundaries.

The extremes of sexual or financial exploitation are clear, but otherwise the entire spectrum of interaction between patient and clinician can be appropriate under certain circumstances. For example, in my work with the Madison (WI) Program of Assertive Community Treatment, I often see patients in their homes, help them with grocery shopping, or assist them with other daily tasks. Although these behaviors do not fit an office model, they are not uncommon in community work and do not necessarily break boundaries.

John Battaglia, MD

Program of Assertive Community Treatment

Associate clinical professor of psychiatry

University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School

Dying too young

The life span of the seriously mentally ill is even shorter than we had thought. Earlier studies showed a loss of 20% of the average life span or 15 to 16 years.1 Recent figures are alarmingly higher, however, and vary from state to state.

Virginia has the "best" mortality rate among the seriously mentally ill with a loss of "only" 13.5 years of potential life, according to the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 Perhaps persons who suffer from schizophrenia should move to Virgina because the loss of potential life years in other states is much worse:

• Arizona: 31.8 years

• Texas: 29.3 years

• Missouri: 27.9 years

• Utah: 26.9 years

• Oklahoma: 26.3 years.

A recent Ohio study of mortality and medical illness found an average loss of 32 years of life among persons with schizophrenia.3

Why is the life span of mentally ill persons so short? Apart from their high rates of death from unnatural causes (suicide, homicide, and accidents), the most frequent killer is cardiovascular disease. High mortality rates are well-documented in schizophrenia from various ailments but especially heart disease.4 Bipolar disorder and major depression are also associated with high death rates from cardiovascular disease.5

The sad truth is that a “dual neglect” contributes to premature mortality of the seriously mentally ill: the system fails to provide ongoing basic primary healthcare, and patients neglect to seek or adhere to medical care.

Persons with serious mental illness often have risk factors associated with preventable causes of heart disease and stroke, including smoking, obesity, sedentary life styles, and poor nutrition. In addition, the metabolic syndrome—obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia—is highly associated with schizophrenia,6 bipolar disorder,7 and unipolar depression.8

Cardiovascular risk associated with metabolic syndrome requires ongoing medical follow-up, which many mentally ill patients do not receive. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found shockingly low treatment rates for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperglycemia among outpatients with schizophrenia around the country.9

Let us mobilize to correct this shameful health disparity, one patient at a time. The message to mental health professionals is clear:

• In addition to controlling symptoms of psychosis, mania, depression, or anxiety, routinely screen patients for weight gain, hypertension, high fasting serum glucose, and elevated lipid levels.

• Refer overweight and obese patients to primary care providers, dietitians, and exercise counselors to reduce their cardiovascular risks.

Psychiatrists and nurse practitioners must address both mental and medical health needs when formulating assessments, treatment plans, and patient education. For practical recommendations on managing medical comorbidities, see “7-point checkup for stable schizophrenia outpatients,” by Britton Ashley Arey, MD, and Stephen R. Marder, MD. The public mental health system also could help the seriously mentally ill by integrating primary healthcare with mental healthcare in community settings across the nation. There are no excuses to do anything less.

1. Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:239-45.

2. Cotton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates years of potential life lost and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 2006;3:1-14.

3. Miller B, Paschall CB. Svendsen DP. Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1482-7.

4. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington DC; 2003.

5. Angst F, Stassen FF, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. J Affect Disord 2002;68:167-81.

6. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

7. Taylor V, MacQueen G. Associations between bipolar disorder and the metabolic syndrome: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1034-41.

8. Heiskamn TH, Niskanen LK, Hintikka JJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome and depression: a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1422-7.

9. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 2006;80:15-22.

The life span of the seriously mentally ill is even shorter than we had thought. Earlier studies showed a loss of 20% of the average life span or 15 to 16 years.1 Recent figures are alarmingly higher, however, and vary from state to state.

Virginia has the "best" mortality rate among the seriously mentally ill with a loss of "only" 13.5 years of potential life, according to the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 Perhaps persons who suffer from schizophrenia should move to Virgina because the loss of potential life years in other states is much worse:

• Arizona: 31.8 years

• Texas: 29.3 years

• Missouri: 27.9 years

• Utah: 26.9 years

• Oklahoma: 26.3 years.

A recent Ohio study of mortality and medical illness found an average loss of 32 years of life among persons with schizophrenia.3

Why is the life span of mentally ill persons so short? Apart from their high rates of death from unnatural causes (suicide, homicide, and accidents), the most frequent killer is cardiovascular disease. High mortality rates are well-documented in schizophrenia from various ailments but especially heart disease.4 Bipolar disorder and major depression are also associated with high death rates from cardiovascular disease.5

The sad truth is that a “dual neglect” contributes to premature mortality of the seriously mentally ill: the system fails to provide ongoing basic primary healthcare, and patients neglect to seek or adhere to medical care.

Persons with serious mental illness often have risk factors associated with preventable causes of heart disease and stroke, including smoking, obesity, sedentary life styles, and poor nutrition. In addition, the metabolic syndrome—obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia—is highly associated with schizophrenia,6 bipolar disorder,7 and unipolar depression.8

Cardiovascular risk associated with metabolic syndrome requires ongoing medical follow-up, which many mentally ill patients do not receive. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found shockingly low treatment rates for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperglycemia among outpatients with schizophrenia around the country.9

Let us mobilize to correct this shameful health disparity, one patient at a time. The message to mental health professionals is clear:

• In addition to controlling symptoms of psychosis, mania, depression, or anxiety, routinely screen patients for weight gain, hypertension, high fasting serum glucose, and elevated lipid levels.

• Refer overweight and obese patients to primary care providers, dietitians, and exercise counselors to reduce their cardiovascular risks.

Psychiatrists and nurse practitioners must address both mental and medical health needs when formulating assessments, treatment plans, and patient education. For practical recommendations on managing medical comorbidities, see “7-point checkup for stable schizophrenia outpatients,” by Britton Ashley Arey, MD, and Stephen R. Marder, MD. The public mental health system also could help the seriously mentally ill by integrating primary healthcare with mental healthcare in community settings across the nation. There are no excuses to do anything less.

The life span of the seriously mentally ill is even shorter than we had thought. Earlier studies showed a loss of 20% of the average life span or 15 to 16 years.1 Recent figures are alarmingly higher, however, and vary from state to state.

Virginia has the "best" mortality rate among the seriously mentally ill with a loss of "only" 13.5 years of potential life, according to the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 Perhaps persons who suffer from schizophrenia should move to Virgina because the loss of potential life years in other states is much worse:

• Arizona: 31.8 years

• Texas: 29.3 years

• Missouri: 27.9 years

• Utah: 26.9 years

• Oklahoma: 26.3 years.

A recent Ohio study of mortality and medical illness found an average loss of 32 years of life among persons with schizophrenia.3

Why is the life span of mentally ill persons so short? Apart from their high rates of death from unnatural causes (suicide, homicide, and accidents), the most frequent killer is cardiovascular disease. High mortality rates are well-documented in schizophrenia from various ailments but especially heart disease.4 Bipolar disorder and major depression are also associated with high death rates from cardiovascular disease.5

The sad truth is that a “dual neglect” contributes to premature mortality of the seriously mentally ill: the system fails to provide ongoing basic primary healthcare, and patients neglect to seek or adhere to medical care.

Persons with serious mental illness often have risk factors associated with preventable causes of heart disease and stroke, including smoking, obesity, sedentary life styles, and poor nutrition. In addition, the metabolic syndrome—obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia—is highly associated with schizophrenia,6 bipolar disorder,7 and unipolar depression.8

Cardiovascular risk associated with metabolic syndrome requires ongoing medical follow-up, which many mentally ill patients do not receive. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found shockingly low treatment rates for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperglycemia among outpatients with schizophrenia around the country.9

Let us mobilize to correct this shameful health disparity, one patient at a time. The message to mental health professionals is clear:

• In addition to controlling symptoms of psychosis, mania, depression, or anxiety, routinely screen patients for weight gain, hypertension, high fasting serum glucose, and elevated lipid levels.

• Refer overweight and obese patients to primary care providers, dietitians, and exercise counselors to reduce their cardiovascular risks.

Psychiatrists and nurse practitioners must address both mental and medical health needs when formulating assessments, treatment plans, and patient education. For practical recommendations on managing medical comorbidities, see “7-point checkup for stable schizophrenia outpatients,” by Britton Ashley Arey, MD, and Stephen R. Marder, MD. The public mental health system also could help the seriously mentally ill by integrating primary healthcare with mental healthcare in community settings across the nation. There are no excuses to do anything less.

1. Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:239-45.

2. Cotton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates years of potential life lost and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 2006;3:1-14.

3. Miller B, Paschall CB. Svendsen DP. Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1482-7.

4. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington DC; 2003.

5. Angst F, Stassen FF, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. J Affect Disord 2002;68:167-81.

6. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

7. Taylor V, MacQueen G. Associations between bipolar disorder and the metabolic syndrome: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1034-41.

8. Heiskamn TH, Niskanen LK, Hintikka JJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome and depression: a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1422-7.

9. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 2006;80:15-22.

1. Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:239-45.

2. Cotton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates years of potential life lost and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 2006;3:1-14.

3. Miller B, Paschall CB. Svendsen DP. Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1482-7.

4. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington DC; 2003.

5. Angst F, Stassen FF, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. J Affect Disord 2002;68:167-81.

6. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

7. Taylor V, MacQueen G. Associations between bipolar disorder and the metabolic syndrome: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1034-41.

8. Heiskamn TH, Niskanen LK, Hintikka JJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome and depression: a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1422-7.

9. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 2006;80:15-22.

Psychosis: Is it a medical problem?

History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

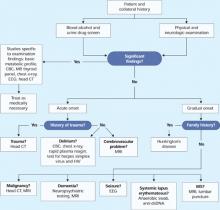

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.

Within 4 days of starting risperidone, Ms. B’s auditory hallucinations and paranoia have lessened and her insight is improved. We recommend increasing the dosage to 2 mg/d because we feel that 1 mg/d will not sufficiently control her symptoms. She remains paranoid but is reluctant to increase the dosage for fear of adverse effects, though she has reported none so far.

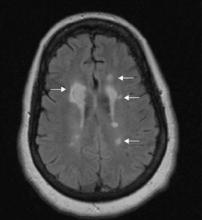

Brain MRI taken the night Ms. B was admitted shows:

- multiple focal, well-defined hyperintense periventricular lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)- and T2-weighted images (Figure 2). Some lesions are flame-shaped.

- a 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to the right frontal horn showing a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images without contrast enhancement. White-matter edema surrounds this lesion.

- no gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Two radiologists confirm possible demyelination, suggesting multiple sclerosis (MS). Final report of initial brain CT shows lowdensity, periventricular white matter changes consistent with the MRI findings.

Results of subsequent laboratory tests are normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is slightly elevated at 35 mm/hr, suggesting a possible autoimmune disorder. ECG shows sinus bradycardia, and chest x-ray and MR angiogram are unremarkable, as are EEG and visual evoked potential results.

Lumbar puncture and CSF studies show increased immunoglobulin G to albumin ratio. CSF fluid is clear, blood counts and protein are normal, Gram’s stain and culture are negative, and cytologic findings show a marked increase in mature lymphocytes. These results suggest inflammation, but follow-up neurologic exam is unremarkable.

Figure 2 FLAIR-weighted image after Ms. B’s brain MRI

Right 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to right frontal horn and multiple left hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted image.

The authors’ observations

Determining disease dissemination in time and space is key to diagnosing MS. Clinical presentation or MRI can determine both criteria (Table 1). Ms. B’s lesions and CSF results suggest that MS has disseminated throughout her body, but neurologic examination shows no objective clinical evidence of lesions.

Neuropsychological testing might help evaluate Ms. B’s cognition and executive functioning, but these deficits do not specifically suggest MS. The cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, is believed to coordinate organization, planning, and socially appropriate behavior. MS typically involves white matter rather than the cortex, but researchers have suggested that MS-related demyelination might disrupt the axonal circuits that connect the cortex to other brain areas.18

Increased lesion load has been correlated with decreased cognitive function. Neuropsychological testing could indirectly point to a lesion load increase by recording decreased cognitive function, but this decline cannot be attributed to MS without an MRI.

Ms. B’s psychotic symptoms could be clinical evidence of MS, but we cannot solidify the diagnosis until we establish dissemination in time. To do that, we need a second MRI 3 months after the first one. Concurrent late-onset paraphrenia and MS is possible but rare.

Table 1

Findings needed to determine MS diagnosis based on clinical presentation

| Clinical presentation | Findings needed for MS diagnosis |

|---|---|

| >2 clinical attacks* Objective clinical evidence of >2 lesions | None |

| >2 clinical attacks Objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| or | |

| Await further attack implicating a different site | |

| 1 clinical attack >2 objective clinical lesions | Dissemination in time by MRI |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| 1 clinical attack 1 objective clinical lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| and | |

| Dissemination in time by MRI | |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| * Clinical attack: neurologic disturbance defined by subjective report or objective observation lasting at least 24 hours. | |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

Follow-up: where is she?

Ms. B is discharged after 10 days. She denies hallucinations, and staff notices decreased paranoia, brighter affect, and improved insight. We tell her to continue taking risperidone, 1 mg/d.

Three weeks later, Ms. B sees an outpatient psychiatrist. She is paranoid, guarded, and has not been taking risperidone.

Because Ms. B’s previous MRI results are suspect, we ask the hospital’s neurology service to examine her. Findings are unremarkable, but the neurologist recommends a followup brain MRI in 3 months or sooner if symptoms emerge. More than 2 years later, she has not completed a second MRI or contacted her psychiatrist or neurologist.

The authors’ observations

Ms. B’s case highlights the importance of:

- recognizing an atypical presentation of a primary psychotic disorder

- checking for a medical cause of psychosis (Table 2)

- knowing which psychiatric symptoms are common in MS.

Despite absence of neurologic symptoms, Ms. B’s psychosis could have been the initial presentation of MS, which is more prevalent among psychiatric inpatients than in the general population.6,7 In a prospective study,8 95% of patients with MS had neuropsychiatric symptoms, and 79% had depressive symptoms. Hallucinations and delusions were reported in 10% and 7% of MS patients, respectively. These findings suggest that mood disturbances are considerably more common than psychosis among patients with MS.

Diagnosis of MSrelated psychosis has been addressed only in case reports or small studies, most of which have not clearly defined psychosis or adequately described the symptoms or confounding factors such as medications. Findings on prevalence of psychosis as the initial presentation in MS are more limited and confounded by instances in which neurologic symptoms might have been overlooked.9,11

Few studies have investigated whether lesion location correlates with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms. In one study,8 brain MRI taken within 9 months of presenting symptoms showed that MS was not significantly more severe among patients with psychosis compared with nonpsychotic MS patients. These data support psychosis as a possible early finding in MS.

At least two studies12,13 suggest a correlation between temporal lobe lesions and psychosis, but both study samples were small (8 and 10 patients) and used a combination of diagnoses. One case report also supports this correlation.14

Table 2

Medical conditions that can cause psychotic symptoms

| Cerebral malignancy (primary and metastases) | |

| Cerebral trauma | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | |

| Delirium | |

| Dementia | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Huntington's disease | |

| Infection | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Parkinson's disease | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

Treating ms-related psychosis

MS-related psychosis should abate with MS treatment, but no systematized studies have verified this or determined which antipsychotics would be suitable. Single case reports suggest successful treatment with risperidone,13 haloperidol,15 clozapine,16 or ziprasidone.17 Ms. B showed initial improvement with risperidone, but because she was lost to follow-up we cannot say if this medication would work long-term.

Related resources

- Feinstein A. The clinical neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. www.nationalmssociety.org.

Drug brand name

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosures

Dr. Higgins reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rafeyan is a speaker for AstraZeneca, BristolMyers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth. He is also an advisor to Abbott Laboratories and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Kaplan B, Sadock V, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:1107,1299.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Howard R, Rabins P, Seeman M, Jeste D. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172-8.

4. Lautenschlager NT, Forstl H. Organic psychosis: insight into the biology of psychosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2001;3:319-25.

5. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121-7.

6. Pine D, Douglas C, Charles E, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis presenting to psychiatric hospitals. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:297-306.

7. Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, Renshaw PF. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:54-9.

8. Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, Garcia de la Cadena C. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:51-7.

9. Felgenhauer K. Psychiatric disorders in the encephalitic form of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 1990;237:11-8.

10. Skegg K, Corwin P, Skegg D. How often is multiple sclerosis mistaken for a psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med 1988;18:733-6.

11. Kohler J, Heilmeyer H, Volk B. Multiple sclerosis presenting as chronic atypical psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:281-4.

12. Honer G, Hurwitz T, Li D, et al. Temporal lobe involvement in multiple sclerosis patients with psychiatric disorders. Arch Neurol 1987;44:187-90.

13. Feinstein A, du Boulay G, Ron M. Psychotic illness in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry 1992;161:680-5.

14. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:27-33.

15. Drake ME. Acute paranoid psychosis in multiple sclerosis. Psychosomatics 1984;25:60-3.

16. Chong SA, Ko SM. Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:90-1.

17. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004;28:743-4.

18. Asghar-Ali A, Taber K, Hurley R, Hayman L. Pure neuropsychiatric presentation of multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:226-31.

History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.