User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Getting patients to talk about priapism

CHIEF COMPLAINT: Anxiety and disordered sleep

Mr. Q, a college sophomore, reported symptoms of insomnia, anxiety, and sadness to the university health service. When in bed, he said, he would ruminate about whether he had studied adequately and would ultimately qualify for a graduate program. He exhibited no pervasive sadness, loss of interest or motivation, suicidal ideation, or loss of self-esteem. His medical history revealed no serious illness.

The student health psychiatrist diagnosed Mr. Q as having generalized anxiety disorder. She prescribed trazodone, up to 100 mg/d as needed, for the insomnia. For the next 3 weeks, he took one 25 mg dose each night. After that time, Mr. Q reported that the trazodone alleviated the insomnia and that he felt more rested and could study more effectively. He had stopped taking the medication.

Mr. Q, however, did not tell the health service psychiatrist that he had also experienced an uncomfortable erection that lasted about 4 hours and was not precipitated or accompanied by sexual activity. He finally experienced detumescence after several cold showers. He did not inform her of the episode because he felt embarrassed to discuss “such a thing” with a female physician.

After his anxiety and insomnia resurfaced, Mr. Q was referred to one of the authors.

Why did Mr. Q. develop priapism? How would you counsel him at this point?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

Priapism refers to a prolonged and painful erection that results from sustained blood flow into the corpora cavernosa. In contrast to a normal erection, both the corpus spongiosum and glans penis remain flaccid. Medical complications and reactions to drugs are well-documented causes.

Table 1

Drugs reported to cause priapism

| Antidepressants |

| Trazodone and, in rare cases, phenelzine and sertraline; bupropion has been associated with clitoral priapism3 |

| Antihypertensives that act via alpha blockade Labetalol, prazosin3-5 |

| Metoclopramide when taken with thioridazine3,4 |

| Sildenafil citrate6 (rare case reports) |

| Substances of abuse |

| Alcohol, marijuana, crack cocaine |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics |

| Chlorpromazine, clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, mesoridazine, molindone, levomepromazine, perphenazine, promazine, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene3-5 |

An erection in priapism may result from sexual stimulation/activity, although this is not typical. Sexually stimulated erections in priapism persist hours after the stimulation ceases.

High-flow priapism is rare, painless, and occurs when well-oxygenated blood stays in the corpora cavernosa. It may result from perineal trauma creating a fistula between an artery and the cavernosa. Because the blood is oxygenated, there is no tissue damage, intervention is not urgent, and the prognosis usually is good.

Low-flow priapism, the more prevalent type, is painful and occurs when venous blood remains in the corpora, resulting in hypoxia and ischemia. Approximately 50% of low-flow priapism cases can result in impotence.1

Because men often are embarrassed by priapism, they may not seek medical attention or mention a prior episode to their physicians. This neglect can be dangerous: Painful erections that persist for more than 4 hours can lead to impotence if left untreated.

The physician must surmount the patient’s reluctance to discuss the symptom. Inquiring about past priapism episodes as part of a complete patient history is essential. We suggest routinely asking patients taking priapism-causing psychotropics (Table 1) if they’ve had a recent erectile problem. Mentioning that a medication can cause uncomfortable and serious sexual side effects may prompt the patient to discuss such problems.

Above all, be direct. A straightforward inquiry about a sensitive medical condition usually draws an honest answer; the patient then realizes the subject is important and should not be embarrassed about it.

After the patient discloses a priapism episode, ask him:

- Was the erection related to sexual activity or desire?

- Were you using any other medications or illicit drugs when the erection occurred?

- Do you have a systemic blood disorder?

- Did you feel any pain during your erection? If so, how long did it persist?

Men who present during a priapism episode should immediately be sent to the ER for urologic treatment. Patients reporting a recent sustained erection should be referred to a urologist if they need to keep taking the priapism-causing drug. Urologic treatment is not necessary if the patient stops the medication and the priapism resolves.

Men who have had at least one past priapism episode and those taking alpha-adrenergic blockers should be instructed to visit the ER immediately if a painful, persistent erection develops. Patients also should be warned not to induce detumescence (such as by taking cold showers, drinking alcohol, or engaging in sexual activity) if the erection persists for more than 2 hours. Any delay in emergency care could lead to impotence.

HISTORY: A probable side effect

Because Mr. Q had no other past erectile problems, we strongly suspected his priapism was medication-induced. He reported he had neither been drinking nor taking illicit drugs or other medications when the erection occurred.

Mr. Q also was convinced that the trazodone had caused the sustained erection. He said, however, he was never informed that priapism was a potential side effect of that medication.

Would you resume trazodone, switch to another sleep-promoting or antianxiety medication, or consider other therapy?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

The prevalence of priapism is not known, although yearly estimates range from 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 patients who take trazodone.2

Trazodone, an alpha-adrenergic blocker, is most commonly implicated among psychotropics in causing priapism.2 Blockade of alpha-adrenergic receptors in the corpora cavernosa creates a parasympathetic imbalance favoring erection and prevents sympathetic-mediated detumescence. Histaminic, beta-adrenergic, and adrenergic/cholinergic components may also contribute to priapism.

Other medications associated with priapism include antipsychotics, antihypertensives, anticoagulants, some antidepressants, and antiimpotence medications injected into the penis.

Low-flow priapism can also be caused by systemic disorders (Table 2), including malignancies—particularly when a tumor has infiltrated the penis—and carcinoma of the bladder or prostate. Prostatitis has been implicated in some cases.

Table 2

Systemic illnesses and conditions that can cause priapism

|

Because Mr. Q has had at least one priapism episode, we would avoid prescribing any agent with alpha-adrenergic blocking properties.

Could Mr. Q’s response to trazodone have been dose-related? How would you ensure that the patient understands a medication’s risks?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

No findings indicate that trazodone-related priapism is dose-related. Several cases of men developing sustained priapism—resulting in permanent injury and impotence—have been reported after initial dosages of 25 and 50 mg/d.1,4,7 In a study using the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System, Warner et al found that priapism with trazodone was most likely to occur within the first month of treatment and at dosages 150 mg/d.7 Still other reports indicate that new-onset priapism may occur after years of treatment.3

Priapism refers to a painful, prolonged erection that occurs in the absence of sexual stimulation or does not remit after sexual activity.

Several psychotropic drugs, most often trazodone (Desyrel), can cause priapism. This can occur even if the medication is taken at a low dosage or taken only once.

Individuals who have had prior prolonged erections are more susceptible to priapism. Certain medical conditions, many medications, and substance abuse can also increase the risk of priapism. This effect may be additive.

If the erection lasts more than 2 hours, the patient must obtain emergency care. Impotence has been reported after erections lasting 4 hours or longer.

Mr. Z filed suit in Pennsylvania state court against his pharmacy and emergency room doctor. He alleged that he developed priapism after taking one dose of trazodone for disordered sleep. He subsequently became impotent.

Christopher T. Rhodes, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at the University of Rhode Island, was an expert witness in that 2000 trial. According to Dr. Rhodes, court testimony revealed that the ER physician had not informed the patient about the possibility of priapism or about the need to obtain emergency treatment for a sustained erection. Dr. Rhodes adds that the pharmacy handout for trazodone did not list priapism as a possible adverse effect.

The court ruled in favor of the patient, judging that the “quality of advice” was inadequate. The patient was awarded an unspecified sum.

Despite its association with priapism, trazodone is used frequently in men and is a popular medication for disordered sleep. Nierenberg et al demonstrated improved sleep in 67% of depressed patients with insomnia who received trazodone either for depression or disordered sleep.8

When prescribing a priapism-causing agent, make sure the patient understands that erectile effects—though rare—can occur. Consider giving patients an informed consent form explaining the association between psychotropics and priapism and the potential long-term health implications (Box 1). Include the form in the patient’s record for documentation in the event of a malpractice lawsuit (Box 2).

FURTHER TREATMENT: Learning how to cope

Self-hypnosis/relaxation therapy was initiated to address Mr. Q’s anxiety and insomnia. The patient quickly learned the hypnosis techniques and his anxiety/insomnia symptoms began to resolve almost immediately.

Mr. Q’s priapism resolved spontaneously with no apparent erectile dysfunction. He was referred back to the university health service and has been in apparent good health since.

Related resources

- Sleepnet.com. Information on sleep disorders and sleep hygiene. http://www.sleepnet.com/

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncsdr/

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Prolixin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Labetalol • Trandate

- Levomepromazine • Nozinan

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Metoclopramide • Reglan

- Molindone • Lidone

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Promazine • Sparine

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil citrate • Viagra

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Thiothixene • Navane

- Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

Dr. Freed reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Muskin receives research/grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., is a speaker for and consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc.; and is a speaker for Cephalon Inc. and Eli Lilly and Co.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. CNS Drugs 1998;9:371-9.

2. Rhodes CT. Trazodone and priapism—implications for responses to adverse events. Clin Res Regulatory Affairs 2001;18:47-52.

3. Compton MT, Miller AH. Priapism associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:362-6.

4. Thompson JW, Ware MR, Blashfield RK. Psychotropic medication and priapism: a comprehensive review. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:430-3.

5. Reeves RR, Kimble R. Prolonged erections associated with ziprasidone treatment: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:97-8.

6. Sur RL, Kane CJ. Sildenafil citrate-associated priapism. Urology 2000;55:950.-

7. Warner MD, Peabody CA, Whiteford HA, Hollister LE. Trazodone and priapism. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:244-5.

8. Nierenberg AA, Adler LA, Peselow E, et al. Trazodone for antidepressant-associated insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1069-72.

CHIEF COMPLAINT: Anxiety and disordered sleep

Mr. Q, a college sophomore, reported symptoms of insomnia, anxiety, and sadness to the university health service. When in bed, he said, he would ruminate about whether he had studied adequately and would ultimately qualify for a graduate program. He exhibited no pervasive sadness, loss of interest or motivation, suicidal ideation, or loss of self-esteem. His medical history revealed no serious illness.

The student health psychiatrist diagnosed Mr. Q as having generalized anxiety disorder. She prescribed trazodone, up to 100 mg/d as needed, for the insomnia. For the next 3 weeks, he took one 25 mg dose each night. After that time, Mr. Q reported that the trazodone alleviated the insomnia and that he felt more rested and could study more effectively. He had stopped taking the medication.

Mr. Q, however, did not tell the health service psychiatrist that he had also experienced an uncomfortable erection that lasted about 4 hours and was not precipitated or accompanied by sexual activity. He finally experienced detumescence after several cold showers. He did not inform her of the episode because he felt embarrassed to discuss “such a thing” with a female physician.

After his anxiety and insomnia resurfaced, Mr. Q was referred to one of the authors.

Why did Mr. Q. develop priapism? How would you counsel him at this point?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

Priapism refers to a prolonged and painful erection that results from sustained blood flow into the corpora cavernosa. In contrast to a normal erection, both the corpus spongiosum and glans penis remain flaccid. Medical complications and reactions to drugs are well-documented causes.

Table 1

Drugs reported to cause priapism

| Antidepressants |

| Trazodone and, in rare cases, phenelzine and sertraline; bupropion has been associated with clitoral priapism3 |

| Antihypertensives that act via alpha blockade Labetalol, prazosin3-5 |

| Metoclopramide when taken with thioridazine3,4 |

| Sildenafil citrate6 (rare case reports) |

| Substances of abuse |

| Alcohol, marijuana, crack cocaine |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics |

| Chlorpromazine, clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, mesoridazine, molindone, levomepromazine, perphenazine, promazine, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene3-5 |

An erection in priapism may result from sexual stimulation/activity, although this is not typical. Sexually stimulated erections in priapism persist hours after the stimulation ceases.

High-flow priapism is rare, painless, and occurs when well-oxygenated blood stays in the corpora cavernosa. It may result from perineal trauma creating a fistula between an artery and the cavernosa. Because the blood is oxygenated, there is no tissue damage, intervention is not urgent, and the prognosis usually is good.

Low-flow priapism, the more prevalent type, is painful and occurs when venous blood remains in the corpora, resulting in hypoxia and ischemia. Approximately 50% of low-flow priapism cases can result in impotence.1

Because men often are embarrassed by priapism, they may not seek medical attention or mention a prior episode to their physicians. This neglect can be dangerous: Painful erections that persist for more than 4 hours can lead to impotence if left untreated.

The physician must surmount the patient’s reluctance to discuss the symptom. Inquiring about past priapism episodes as part of a complete patient history is essential. We suggest routinely asking patients taking priapism-causing psychotropics (Table 1) if they’ve had a recent erectile problem. Mentioning that a medication can cause uncomfortable and serious sexual side effects may prompt the patient to discuss such problems.

Above all, be direct. A straightforward inquiry about a sensitive medical condition usually draws an honest answer; the patient then realizes the subject is important and should not be embarrassed about it.

After the patient discloses a priapism episode, ask him:

- Was the erection related to sexual activity or desire?

- Were you using any other medications or illicit drugs when the erection occurred?

- Do you have a systemic blood disorder?

- Did you feel any pain during your erection? If so, how long did it persist?

Men who present during a priapism episode should immediately be sent to the ER for urologic treatment. Patients reporting a recent sustained erection should be referred to a urologist if they need to keep taking the priapism-causing drug. Urologic treatment is not necessary if the patient stops the medication and the priapism resolves.

Men who have had at least one past priapism episode and those taking alpha-adrenergic blockers should be instructed to visit the ER immediately if a painful, persistent erection develops. Patients also should be warned not to induce detumescence (such as by taking cold showers, drinking alcohol, or engaging in sexual activity) if the erection persists for more than 2 hours. Any delay in emergency care could lead to impotence.

HISTORY: A probable side effect

Because Mr. Q had no other past erectile problems, we strongly suspected his priapism was medication-induced. He reported he had neither been drinking nor taking illicit drugs or other medications when the erection occurred.

Mr. Q also was convinced that the trazodone had caused the sustained erection. He said, however, he was never informed that priapism was a potential side effect of that medication.

Would you resume trazodone, switch to another sleep-promoting or antianxiety medication, or consider other therapy?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

The prevalence of priapism is not known, although yearly estimates range from 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 patients who take trazodone.2

Trazodone, an alpha-adrenergic blocker, is most commonly implicated among psychotropics in causing priapism.2 Blockade of alpha-adrenergic receptors in the corpora cavernosa creates a parasympathetic imbalance favoring erection and prevents sympathetic-mediated detumescence. Histaminic, beta-adrenergic, and adrenergic/cholinergic components may also contribute to priapism.

Other medications associated with priapism include antipsychotics, antihypertensives, anticoagulants, some antidepressants, and antiimpotence medications injected into the penis.

Low-flow priapism can also be caused by systemic disorders (Table 2), including malignancies—particularly when a tumor has infiltrated the penis—and carcinoma of the bladder or prostate. Prostatitis has been implicated in some cases.

Table 2

Systemic illnesses and conditions that can cause priapism

|

Because Mr. Q has had at least one priapism episode, we would avoid prescribing any agent with alpha-adrenergic blocking properties.

Could Mr. Q’s response to trazodone have been dose-related? How would you ensure that the patient understands a medication’s risks?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

No findings indicate that trazodone-related priapism is dose-related. Several cases of men developing sustained priapism—resulting in permanent injury and impotence—have been reported after initial dosages of 25 and 50 mg/d.1,4,7 In a study using the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System, Warner et al found that priapism with trazodone was most likely to occur within the first month of treatment and at dosages 150 mg/d.7 Still other reports indicate that new-onset priapism may occur after years of treatment.3

Priapism refers to a painful, prolonged erection that occurs in the absence of sexual stimulation or does not remit after sexual activity.

Several psychotropic drugs, most often trazodone (Desyrel), can cause priapism. This can occur even if the medication is taken at a low dosage or taken only once.

Individuals who have had prior prolonged erections are more susceptible to priapism. Certain medical conditions, many medications, and substance abuse can also increase the risk of priapism. This effect may be additive.

If the erection lasts more than 2 hours, the patient must obtain emergency care. Impotence has been reported after erections lasting 4 hours or longer.

Mr. Z filed suit in Pennsylvania state court against his pharmacy and emergency room doctor. He alleged that he developed priapism after taking one dose of trazodone for disordered sleep. He subsequently became impotent.

Christopher T. Rhodes, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at the University of Rhode Island, was an expert witness in that 2000 trial. According to Dr. Rhodes, court testimony revealed that the ER physician had not informed the patient about the possibility of priapism or about the need to obtain emergency treatment for a sustained erection. Dr. Rhodes adds that the pharmacy handout for trazodone did not list priapism as a possible adverse effect.

The court ruled in favor of the patient, judging that the “quality of advice” was inadequate. The patient was awarded an unspecified sum.

Despite its association with priapism, trazodone is used frequently in men and is a popular medication for disordered sleep. Nierenberg et al demonstrated improved sleep in 67% of depressed patients with insomnia who received trazodone either for depression or disordered sleep.8

When prescribing a priapism-causing agent, make sure the patient understands that erectile effects—though rare—can occur. Consider giving patients an informed consent form explaining the association between psychotropics and priapism and the potential long-term health implications (Box 1). Include the form in the patient’s record for documentation in the event of a malpractice lawsuit (Box 2).

FURTHER TREATMENT: Learning how to cope

Self-hypnosis/relaxation therapy was initiated to address Mr. Q’s anxiety and insomnia. The patient quickly learned the hypnosis techniques and his anxiety/insomnia symptoms began to resolve almost immediately.

Mr. Q’s priapism resolved spontaneously with no apparent erectile dysfunction. He was referred back to the university health service and has been in apparent good health since.

Related resources

- Sleepnet.com. Information on sleep disorders and sleep hygiene. http://www.sleepnet.com/

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncsdr/

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Prolixin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Labetalol • Trandate

- Levomepromazine • Nozinan

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Metoclopramide • Reglan

- Molindone • Lidone

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Promazine • Sparine

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil citrate • Viagra

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Thiothixene • Navane

- Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

Dr. Freed reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Muskin receives research/grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., is a speaker for and consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc.; and is a speaker for Cephalon Inc. and Eli Lilly and Co.

CHIEF COMPLAINT: Anxiety and disordered sleep

Mr. Q, a college sophomore, reported symptoms of insomnia, anxiety, and sadness to the university health service. When in bed, he said, he would ruminate about whether he had studied adequately and would ultimately qualify for a graduate program. He exhibited no pervasive sadness, loss of interest or motivation, suicidal ideation, or loss of self-esteem. His medical history revealed no serious illness.

The student health psychiatrist diagnosed Mr. Q as having generalized anxiety disorder. She prescribed trazodone, up to 100 mg/d as needed, for the insomnia. For the next 3 weeks, he took one 25 mg dose each night. After that time, Mr. Q reported that the trazodone alleviated the insomnia and that he felt more rested and could study more effectively. He had stopped taking the medication.

Mr. Q, however, did not tell the health service psychiatrist that he had also experienced an uncomfortable erection that lasted about 4 hours and was not precipitated or accompanied by sexual activity. He finally experienced detumescence after several cold showers. He did not inform her of the episode because he felt embarrassed to discuss “such a thing” with a female physician.

After his anxiety and insomnia resurfaced, Mr. Q was referred to one of the authors.

Why did Mr. Q. develop priapism? How would you counsel him at this point?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

Priapism refers to a prolonged and painful erection that results from sustained blood flow into the corpora cavernosa. In contrast to a normal erection, both the corpus spongiosum and glans penis remain flaccid. Medical complications and reactions to drugs are well-documented causes.

Table 1

Drugs reported to cause priapism

| Antidepressants |

| Trazodone and, in rare cases, phenelzine and sertraline; bupropion has been associated with clitoral priapism3 |

| Antihypertensives that act via alpha blockade Labetalol, prazosin3-5 |

| Metoclopramide when taken with thioridazine3,4 |

| Sildenafil citrate6 (rare case reports) |

| Substances of abuse |

| Alcohol, marijuana, crack cocaine |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics |

| Chlorpromazine, clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, mesoridazine, molindone, levomepromazine, perphenazine, promazine, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene3-5 |

An erection in priapism may result from sexual stimulation/activity, although this is not typical. Sexually stimulated erections in priapism persist hours after the stimulation ceases.

High-flow priapism is rare, painless, and occurs when well-oxygenated blood stays in the corpora cavernosa. It may result from perineal trauma creating a fistula between an artery and the cavernosa. Because the blood is oxygenated, there is no tissue damage, intervention is not urgent, and the prognosis usually is good.

Low-flow priapism, the more prevalent type, is painful and occurs when venous blood remains in the corpora, resulting in hypoxia and ischemia. Approximately 50% of low-flow priapism cases can result in impotence.1

Because men often are embarrassed by priapism, they may not seek medical attention or mention a prior episode to their physicians. This neglect can be dangerous: Painful erections that persist for more than 4 hours can lead to impotence if left untreated.

The physician must surmount the patient’s reluctance to discuss the symptom. Inquiring about past priapism episodes as part of a complete patient history is essential. We suggest routinely asking patients taking priapism-causing psychotropics (Table 1) if they’ve had a recent erectile problem. Mentioning that a medication can cause uncomfortable and serious sexual side effects may prompt the patient to discuss such problems.

Above all, be direct. A straightforward inquiry about a sensitive medical condition usually draws an honest answer; the patient then realizes the subject is important and should not be embarrassed about it.

After the patient discloses a priapism episode, ask him:

- Was the erection related to sexual activity or desire?

- Were you using any other medications or illicit drugs when the erection occurred?

- Do you have a systemic blood disorder?

- Did you feel any pain during your erection? If so, how long did it persist?

Men who present during a priapism episode should immediately be sent to the ER for urologic treatment. Patients reporting a recent sustained erection should be referred to a urologist if they need to keep taking the priapism-causing drug. Urologic treatment is not necessary if the patient stops the medication and the priapism resolves.

Men who have had at least one past priapism episode and those taking alpha-adrenergic blockers should be instructed to visit the ER immediately if a painful, persistent erection develops. Patients also should be warned not to induce detumescence (such as by taking cold showers, drinking alcohol, or engaging in sexual activity) if the erection persists for more than 2 hours. Any delay in emergency care could lead to impotence.

HISTORY: A probable side effect

Because Mr. Q had no other past erectile problems, we strongly suspected his priapism was medication-induced. He reported he had neither been drinking nor taking illicit drugs or other medications when the erection occurred.

Mr. Q also was convinced that the trazodone had caused the sustained erection. He said, however, he was never informed that priapism was a potential side effect of that medication.

Would you resume trazodone, switch to another sleep-promoting or antianxiety medication, or consider other therapy?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

The prevalence of priapism is not known, although yearly estimates range from 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 patients who take trazodone.2

Trazodone, an alpha-adrenergic blocker, is most commonly implicated among psychotropics in causing priapism.2 Blockade of alpha-adrenergic receptors in the corpora cavernosa creates a parasympathetic imbalance favoring erection and prevents sympathetic-mediated detumescence. Histaminic, beta-adrenergic, and adrenergic/cholinergic components may also contribute to priapism.

Other medications associated with priapism include antipsychotics, antihypertensives, anticoagulants, some antidepressants, and antiimpotence medications injected into the penis.

Low-flow priapism can also be caused by systemic disorders (Table 2), including malignancies—particularly when a tumor has infiltrated the penis—and carcinoma of the bladder or prostate. Prostatitis has been implicated in some cases.

Table 2

Systemic illnesses and conditions that can cause priapism

|

Because Mr. Q has had at least one priapism episode, we would avoid prescribing any agent with alpha-adrenergic blocking properties.

Could Mr. Q’s response to trazodone have been dose-related? How would you ensure that the patient understands a medication’s risks?

Dr. Freed’s and Dr. Muskin’s observations

No findings indicate that trazodone-related priapism is dose-related. Several cases of men developing sustained priapism—resulting in permanent injury and impotence—have been reported after initial dosages of 25 and 50 mg/d.1,4,7 In a study using the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System, Warner et al found that priapism with trazodone was most likely to occur within the first month of treatment and at dosages 150 mg/d.7 Still other reports indicate that new-onset priapism may occur after years of treatment.3

Priapism refers to a painful, prolonged erection that occurs in the absence of sexual stimulation or does not remit after sexual activity.

Several psychotropic drugs, most often trazodone (Desyrel), can cause priapism. This can occur even if the medication is taken at a low dosage or taken only once.

Individuals who have had prior prolonged erections are more susceptible to priapism. Certain medical conditions, many medications, and substance abuse can also increase the risk of priapism. This effect may be additive.

If the erection lasts more than 2 hours, the patient must obtain emergency care. Impotence has been reported after erections lasting 4 hours or longer.

Mr. Z filed suit in Pennsylvania state court against his pharmacy and emergency room doctor. He alleged that he developed priapism after taking one dose of trazodone for disordered sleep. He subsequently became impotent.

Christopher T. Rhodes, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at the University of Rhode Island, was an expert witness in that 2000 trial. According to Dr. Rhodes, court testimony revealed that the ER physician had not informed the patient about the possibility of priapism or about the need to obtain emergency treatment for a sustained erection. Dr. Rhodes adds that the pharmacy handout for trazodone did not list priapism as a possible adverse effect.

The court ruled in favor of the patient, judging that the “quality of advice” was inadequate. The patient was awarded an unspecified sum.

Despite its association with priapism, trazodone is used frequently in men and is a popular medication for disordered sleep. Nierenberg et al demonstrated improved sleep in 67% of depressed patients with insomnia who received trazodone either for depression or disordered sleep.8

When prescribing a priapism-causing agent, make sure the patient understands that erectile effects—though rare—can occur. Consider giving patients an informed consent form explaining the association between psychotropics and priapism and the potential long-term health implications (Box 1). Include the form in the patient’s record for documentation in the event of a malpractice lawsuit (Box 2).

FURTHER TREATMENT: Learning how to cope

Self-hypnosis/relaxation therapy was initiated to address Mr. Q’s anxiety and insomnia. The patient quickly learned the hypnosis techniques and his anxiety/insomnia symptoms began to resolve almost immediately.

Mr. Q’s priapism resolved spontaneously with no apparent erectile dysfunction. He was referred back to the university health service and has been in apparent good health since.

Related resources

- Sleepnet.com. Information on sleep disorders and sleep hygiene. http://www.sleepnet.com/

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncsdr/

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Prolixin

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Labetalol • Trandate

- Levomepromazine • Nozinan

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Metoclopramide • Reglan

- Molindone • Lidone

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Promazine • Sparine

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil citrate • Viagra

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Thiothixene • Navane

- Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

Dr. Freed reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Muskin receives research/grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., is a speaker for and consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Inc.; and is a speaker for Cephalon Inc. and Eli Lilly and Co.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. CNS Drugs 1998;9:371-9.

2. Rhodes CT. Trazodone and priapism—implications for responses to adverse events. Clin Res Regulatory Affairs 2001;18:47-52.

3. Compton MT, Miller AH. Priapism associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:362-6.

4. Thompson JW, Ware MR, Blashfield RK. Psychotropic medication and priapism: a comprehensive review. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:430-3.

5. Reeves RR, Kimble R. Prolonged erections associated with ziprasidone treatment: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:97-8.

6. Sur RL, Kane CJ. Sildenafil citrate-associated priapism. Urology 2000;55:950.-

7. Warner MD, Peabody CA, Whiteford HA, Hollister LE. Trazodone and priapism. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:244-5.

8. Nierenberg AA, Adler LA, Peselow E, et al. Trazodone for antidepressant-associated insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1069-72.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. CNS Drugs 1998;9:371-9.

2. Rhodes CT. Trazodone and priapism—implications for responses to adverse events. Clin Res Regulatory Affairs 2001;18:47-52.

3. Compton MT, Miller AH. Priapism associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:362-6.

4. Thompson JW, Ware MR, Blashfield RK. Psychotropic medication and priapism: a comprehensive review. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:430-3.

5. Reeves RR, Kimble R. Prolonged erections associated with ziprasidone treatment: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:97-8.

6. Sur RL, Kane CJ. Sildenafil citrate-associated priapism. Urology 2000;55:950.-

7. Warner MD, Peabody CA, Whiteford HA, Hollister LE. Trazodone and priapism. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:244-5.

8. Nierenberg AA, Adler LA, Peselow E, et al. Trazodone for antidepressant-associated insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1069-72.

Cyber self-help

Patients who dread the stigma of in-person psychotherapy are substituting traditional “couch trips” with computer sessions.

Computer-based therapy programs, either online or on CD-ROM or DVD, have become popular adjuncts to traditional therapy for patients with mild depression or anxiety. For example, more than 17,000 users visited the MoodGYM site within 6 months, and more than 20% of these users stayed on the site for 16 minutes or more.1

Computerized psychotherapy has demonstrated numerous benefits in clinical studies and may reduce the time a therapist needs to spend with the patient.

How computer therapy works

Computer-based psychotherapy has its roots in the ELIZA2 program developed in 1966 to study natural language communication between man and machine.3 Users simply write a normal sentence, and ELIZA responds appropriately.

The original ELIZA program, which works via text parsing, is limited in its ability to respond. For example, a user who types in “I feel depressed every day” may repeatedly get a response such as “Are you sure?”

Today’s programs are more sophisticated, utilizing specialized heuristic techniques and semantic databases to produce more natural responses to various expressions. Some programs even have audio and video features.

Most computer-based therapy programs employ a cognitive-behavioral treatment model, similar to that used in print workbooks. Several key concepts are presented, such as the relationship between automatic thoughts and feelings; techniques to control these thoughts are highlighted.

Many programs also use common scales to determine depression or anxiety ratings, thus helping the user choose an appropriate module.

Advantages of computer psychotherapy

Computer-based programs offer patients advantages such as:

- Increased comfort. Without the social cues and dynamics that characterize traditional psychotherapy, some patients may disclose feelings online they would feel uncomfortable sharing in person. Online therapy also is immune to the fatigue, illness, boredom, or exploitation that may occur in a relationship with a therapist.

- Flexibility. Users can work the program at home, at their convenience and pace. Responses to exercises also can be stored for future reference.

- Speed of care. Treatment is accessed with minimal delay.

- A greater sense of empowerment. Whereas patients in traditional therapy often feel dependent upon their therapist for direction, computer-based therapy encourages users to take a more active learning role by choosing where to click and how to respond. Patients feel more in control because they are helping themselves.

- Cost-effectiveness. Although price varies, some programs cost about the same as one in-person session. Most programs are sold directly to medical practices.

Disadvantages

Some patients will not benefit from self-help. Those with moderate to severe depression or anxiety may be unable to focus on the material, and inability to navigate the program can increase the patent’s despondency or anxiety. Personality type also may predict lack of response to self-help treatment.4

Patients with poor eyesight, deficient reading skills, and limited computer proficiency are not good candidates for online or CD-ROM-based therapy. Also, some computers may not be sufficiently powerful to run some programs, and not all Internet connections are fast enough to post multimedia features.

Clinical effectiveness

In 1990, Selmi et al5 compared a six-session, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) course in CD-ROM with six therapist-administered CBT sessions and a control group. An experimenter assisted with computer operation, and both courses followed an identical treatment model and required homework. Patients in both treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement based on Beck Depression Inventory and Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire scores.

Each group comprised only 12 patients, most of whom were young and well-educated. Still, Selmi et al provided initial evidence of computer-based therapy’s effectiveness and these findings have been replicated in subsequent studies. A meta-analysis of 16 studies6 found that CD-ROM-based and therapist-administered CBT work equally well in clinically depressed and anxious outpatients. More studies are needed to determine optimal levels of therapist involvement.

More research also is needed to gauge the effectiveness of Internet-based therapy programs (Table). Clarke et al randomized 144 out of 299 patients in a nonprofit health maintenance organization to online therapy with the Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) program or to treatment as usual. The study demonstrated no effect for ODIN, perhaps because of severity of depression or infrequent access to the site.7

Table

Samples of computer-based psychotherapy programs

| Beating the Blues http://www.ultrasis.co.uk/products/btb/btb.html |

| BT STEPS http://www.healthtechsys.com/ivr/btsteps/btsteps.html |

| Behavioral Self-Control |

| Program for Windows http://www.behaviortherapy.com/software.htm#software |

| Calipso http://www.calipso.co.uk/mainframe.htm |

| FearFighter http://www.fearfighter.com |

| Good Days Ahead http://www.mindstreet.com |

| MoodGYM http://moodgym.anu.edu.au |

| Overcoming Depression http://www.maiw.com/main.html |

| Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) https://www.kpchr.org/feelbetter/ |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

1. Christensen H, Griffiths K, Korten A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(1):e3. Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/1/e3/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

2. ELIZA. Available at: http://www-ai.ijs.si/eliza/eliza.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

3. ELIZA- a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the Association for Computing Machinery 1966;9(1):35-6.Available at: http://i5.nyu.edu/~mm64/x52.9265/january1966.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

4. Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, et al. Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential, and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:333-40.

5. Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:51-6.

6. Kaltenthaler E, Shackley P, Stevens K, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety. Health Technol Assess 2002;6(22):1-89.

7. Clarke G, Reid E, Eubanks D, et al. Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN): a randomized trial of an Internet depression skills intervention program. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(3):e14.-Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/3/e14/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

Patients who dread the stigma of in-person psychotherapy are substituting traditional “couch trips” with computer sessions.

Computer-based therapy programs, either online or on CD-ROM or DVD, have become popular adjuncts to traditional therapy for patients with mild depression or anxiety. For example, more than 17,000 users visited the MoodGYM site within 6 months, and more than 20% of these users stayed on the site for 16 minutes or more.1

Computerized psychotherapy has demonstrated numerous benefits in clinical studies and may reduce the time a therapist needs to spend with the patient.

How computer therapy works

Computer-based psychotherapy has its roots in the ELIZA2 program developed in 1966 to study natural language communication between man and machine.3 Users simply write a normal sentence, and ELIZA responds appropriately.

The original ELIZA program, which works via text parsing, is limited in its ability to respond. For example, a user who types in “I feel depressed every day” may repeatedly get a response such as “Are you sure?”

Today’s programs are more sophisticated, utilizing specialized heuristic techniques and semantic databases to produce more natural responses to various expressions. Some programs even have audio and video features.

Most computer-based therapy programs employ a cognitive-behavioral treatment model, similar to that used in print workbooks. Several key concepts are presented, such as the relationship between automatic thoughts and feelings; techniques to control these thoughts are highlighted.

Many programs also use common scales to determine depression or anxiety ratings, thus helping the user choose an appropriate module.

Advantages of computer psychotherapy

Computer-based programs offer patients advantages such as:

- Increased comfort. Without the social cues and dynamics that characterize traditional psychotherapy, some patients may disclose feelings online they would feel uncomfortable sharing in person. Online therapy also is immune to the fatigue, illness, boredom, or exploitation that may occur in a relationship with a therapist.

- Flexibility. Users can work the program at home, at their convenience and pace. Responses to exercises also can be stored for future reference.

- Speed of care. Treatment is accessed with minimal delay.

- A greater sense of empowerment. Whereas patients in traditional therapy often feel dependent upon their therapist for direction, computer-based therapy encourages users to take a more active learning role by choosing where to click and how to respond. Patients feel more in control because they are helping themselves.

- Cost-effectiveness. Although price varies, some programs cost about the same as one in-person session. Most programs are sold directly to medical practices.

Disadvantages

Some patients will not benefit from self-help. Those with moderate to severe depression or anxiety may be unable to focus on the material, and inability to navigate the program can increase the patent’s despondency or anxiety. Personality type also may predict lack of response to self-help treatment.4

Patients with poor eyesight, deficient reading skills, and limited computer proficiency are not good candidates for online or CD-ROM-based therapy. Also, some computers may not be sufficiently powerful to run some programs, and not all Internet connections are fast enough to post multimedia features.

Clinical effectiveness

In 1990, Selmi et al5 compared a six-session, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) course in CD-ROM with six therapist-administered CBT sessions and a control group. An experimenter assisted with computer operation, and both courses followed an identical treatment model and required homework. Patients in both treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement based on Beck Depression Inventory and Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire scores.

Each group comprised only 12 patients, most of whom were young and well-educated. Still, Selmi et al provided initial evidence of computer-based therapy’s effectiveness and these findings have been replicated in subsequent studies. A meta-analysis of 16 studies6 found that CD-ROM-based and therapist-administered CBT work equally well in clinically depressed and anxious outpatients. More studies are needed to determine optimal levels of therapist involvement.

More research also is needed to gauge the effectiveness of Internet-based therapy programs (Table). Clarke et al randomized 144 out of 299 patients in a nonprofit health maintenance organization to online therapy with the Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) program or to treatment as usual. The study demonstrated no effect for ODIN, perhaps because of severity of depression or infrequent access to the site.7

Table

Samples of computer-based psychotherapy programs

| Beating the Blues http://www.ultrasis.co.uk/products/btb/btb.html |

| BT STEPS http://www.healthtechsys.com/ivr/btsteps/btsteps.html |

| Behavioral Self-Control |

| Program for Windows http://www.behaviortherapy.com/software.htm#software |

| Calipso http://www.calipso.co.uk/mainframe.htm |

| FearFighter http://www.fearfighter.com |

| Good Days Ahead http://www.mindstreet.com |

| MoodGYM http://moodgym.anu.edu.au |

| Overcoming Depression http://www.maiw.com/main.html |

| Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) https://www.kpchr.org/feelbetter/ |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Patients who dread the stigma of in-person psychotherapy are substituting traditional “couch trips” with computer sessions.

Computer-based therapy programs, either online or on CD-ROM or DVD, have become popular adjuncts to traditional therapy for patients with mild depression or anxiety. For example, more than 17,000 users visited the MoodGYM site within 6 months, and more than 20% of these users stayed on the site for 16 minutes or more.1

Computerized psychotherapy has demonstrated numerous benefits in clinical studies and may reduce the time a therapist needs to spend with the patient.

How computer therapy works

Computer-based psychotherapy has its roots in the ELIZA2 program developed in 1966 to study natural language communication between man and machine.3 Users simply write a normal sentence, and ELIZA responds appropriately.

The original ELIZA program, which works via text parsing, is limited in its ability to respond. For example, a user who types in “I feel depressed every day” may repeatedly get a response such as “Are you sure?”

Today’s programs are more sophisticated, utilizing specialized heuristic techniques and semantic databases to produce more natural responses to various expressions. Some programs even have audio and video features.

Most computer-based therapy programs employ a cognitive-behavioral treatment model, similar to that used in print workbooks. Several key concepts are presented, such as the relationship between automatic thoughts and feelings; techniques to control these thoughts are highlighted.

Many programs also use common scales to determine depression or anxiety ratings, thus helping the user choose an appropriate module.

Advantages of computer psychotherapy

Computer-based programs offer patients advantages such as:

- Increased comfort. Without the social cues and dynamics that characterize traditional psychotherapy, some patients may disclose feelings online they would feel uncomfortable sharing in person. Online therapy also is immune to the fatigue, illness, boredom, or exploitation that may occur in a relationship with a therapist.

- Flexibility. Users can work the program at home, at their convenience and pace. Responses to exercises also can be stored for future reference.

- Speed of care. Treatment is accessed with minimal delay.

- A greater sense of empowerment. Whereas patients in traditional therapy often feel dependent upon their therapist for direction, computer-based therapy encourages users to take a more active learning role by choosing where to click and how to respond. Patients feel more in control because they are helping themselves.

- Cost-effectiveness. Although price varies, some programs cost about the same as one in-person session. Most programs are sold directly to medical practices.

Disadvantages

Some patients will not benefit from self-help. Those with moderate to severe depression or anxiety may be unable to focus on the material, and inability to navigate the program can increase the patent’s despondency or anxiety. Personality type also may predict lack of response to self-help treatment.4

Patients with poor eyesight, deficient reading skills, and limited computer proficiency are not good candidates for online or CD-ROM-based therapy. Also, some computers may not be sufficiently powerful to run some programs, and not all Internet connections are fast enough to post multimedia features.

Clinical effectiveness

In 1990, Selmi et al5 compared a six-session, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) course in CD-ROM with six therapist-administered CBT sessions and a control group. An experimenter assisted with computer operation, and both courses followed an identical treatment model and required homework. Patients in both treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement based on Beck Depression Inventory and Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire scores.

Each group comprised only 12 patients, most of whom were young and well-educated. Still, Selmi et al provided initial evidence of computer-based therapy’s effectiveness and these findings have been replicated in subsequent studies. A meta-analysis of 16 studies6 found that CD-ROM-based and therapist-administered CBT work equally well in clinically depressed and anxious outpatients. More studies are needed to determine optimal levels of therapist involvement.

More research also is needed to gauge the effectiveness of Internet-based therapy programs (Table). Clarke et al randomized 144 out of 299 patients in a nonprofit health maintenance organization to online therapy with the Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) program or to treatment as usual. The study demonstrated no effect for ODIN, perhaps because of severity of depression or infrequent access to the site.7

Table

Samples of computer-based psychotherapy programs

| Beating the Blues http://www.ultrasis.co.uk/products/btb/btb.html |

| BT STEPS http://www.healthtechsys.com/ivr/btsteps/btsteps.html |

| Behavioral Self-Control |

| Program for Windows http://www.behaviortherapy.com/software.htm#software |

| Calipso http://www.calipso.co.uk/mainframe.htm |

| FearFighter http://www.fearfighter.com |

| Good Days Ahead http://www.mindstreet.com |

| MoodGYM http://moodgym.anu.edu.au |

| Overcoming Depression http://www.maiw.com/main.html |

| Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) https://www.kpchr.org/feelbetter/ |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

1. Christensen H, Griffiths K, Korten A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(1):e3. Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/1/e3/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

2. ELIZA. Available at: http://www-ai.ijs.si/eliza/eliza.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

3. ELIZA- a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the Association for Computing Machinery 1966;9(1):35-6.Available at: http://i5.nyu.edu/~mm64/x52.9265/january1966.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

4. Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, et al. Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential, and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:333-40.

5. Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:51-6.

6. Kaltenthaler E, Shackley P, Stevens K, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety. Health Technol Assess 2002;6(22):1-89.

7. Clarke G, Reid E, Eubanks D, et al. Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN): a randomized trial of an Internet depression skills intervention program. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(3):e14.-Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/3/e14/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

1. Christensen H, Griffiths K, Korten A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(1):e3. Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/1/e3/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

2. ELIZA. Available at: http://www-ai.ijs.si/eliza/eliza.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

3. ELIZA- a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the Association for Computing Machinery 1966;9(1):35-6.Available at: http://i5.nyu.edu/~mm64/x52.9265/january1966.html. Accessed July 1, 2003.

4. Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, et al. Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential, and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:333-40.

5. Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:51-6.

6. Kaltenthaler E, Shackley P, Stevens K, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety. Health Technol Assess 2002;6(22):1-89.

7. Clarke G, Reid E, Eubanks D, et al. Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN): a randomized trial of an Internet depression skills intervention program. J Med Internet Res 2002;4(3):e14.-Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2002/3/e14/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2003.

5 fundamentals of managing adult ADHD

As a psychiatrist specializing in college health, I see 40 to 50 young adults yearly with undiagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). I have found that understanding five fundamentals of ADHD is key to recognizing this disorder in adults.

- There is no “adult onset” ADHD. Although ADHD may manifest itself differently in adults than in children, studies indicate that the disorder is a continuation of childhood ADHD rather than a discrete adult disorder. Clinicians thus need to establish that adult patients exhibited symptomatic and functional impairment before age 7 (as per DSM-IV), although some experts suggest preadolescence as a cutoff.1

- Most people do not “outgrow” ADHD. We once assumed that most patients with ADHD became asymptomatic as they matured from adolescence into adulthood. Research reveals that hyperactivity and impulsivity decline over time but inattention and executive dysfunction usually persist into adulthood.2 These residual deficits cause continued vocational, academic, and interpersonal difficulties.

- ADHD can mimic other psychiatric disorders. The hyperkinesis, impulsivity, and inattention that are the essence of ADHD are also commonly observed in adults with anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance abuse problems, and learning disorders. Patients who present with atypical affective or anxiety symptoms or learning problems, or who do not respond to conventional treatments, should be screened for ADHD.

- The genetic apple does not fall far from the tree in ADHD. Many adults with ADHD are identified in middle age after their children are diagnosed. Adoption data and multiple twin studies have placed the heritability of ADHD at approximately 75%,3 putting first-degree relatives at fairly high predisposition.

- Stimulant medications do not promote substance abuse in ADHD patients. Stimulant medication is more likely to reduce the risk of substance abuse in ADHD than enhance it.4 For patients at high-risk for substance abuse disorders, however, atomoxetine and bupropion offer nonstimulant alternatives. Also, the newer, longer-acting dextroamphetamine/amphetamine and methylphenidate preparations are more difficult to abuse because of their slow-release mechanisms.

1. Barkley RA, Biederman J. Toward a broader definition of the age-of-onset criteria for attention deficit disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1204-10.

2. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood as a function of reporting sources and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002;111:279-89.

3. Sprich S, Biederman J, Crawford MH, et al. Adoptive and biological families of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Am Acad. Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;143:1432-7.

4. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 1999;104:e20.-

Dr. Anders is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry, University Health Services, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

As a psychiatrist specializing in college health, I see 40 to 50 young adults yearly with undiagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). I have found that understanding five fundamentals of ADHD is key to recognizing this disorder in adults.

- There is no “adult onset” ADHD. Although ADHD may manifest itself differently in adults than in children, studies indicate that the disorder is a continuation of childhood ADHD rather than a discrete adult disorder. Clinicians thus need to establish that adult patients exhibited symptomatic and functional impairment before age 7 (as per DSM-IV), although some experts suggest preadolescence as a cutoff.1

- Most people do not “outgrow” ADHD. We once assumed that most patients with ADHD became asymptomatic as they matured from adolescence into adulthood. Research reveals that hyperactivity and impulsivity decline over time but inattention and executive dysfunction usually persist into adulthood.2 These residual deficits cause continued vocational, academic, and interpersonal difficulties.

- ADHD can mimic other psychiatric disorders. The hyperkinesis, impulsivity, and inattention that are the essence of ADHD are also commonly observed in adults with anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance abuse problems, and learning disorders. Patients who present with atypical affective or anxiety symptoms or learning problems, or who do not respond to conventional treatments, should be screened for ADHD.

- The genetic apple does not fall far from the tree in ADHD. Many adults with ADHD are identified in middle age after their children are diagnosed. Adoption data and multiple twin studies have placed the heritability of ADHD at approximately 75%,3 putting first-degree relatives at fairly high predisposition.

- Stimulant medications do not promote substance abuse in ADHD patients. Stimulant medication is more likely to reduce the risk of substance abuse in ADHD than enhance it.4 For patients at high-risk for substance abuse disorders, however, atomoxetine and bupropion offer nonstimulant alternatives. Also, the newer, longer-acting dextroamphetamine/amphetamine and methylphenidate preparations are more difficult to abuse because of their slow-release mechanisms.

As a psychiatrist specializing in college health, I see 40 to 50 young adults yearly with undiagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). I have found that understanding five fundamentals of ADHD is key to recognizing this disorder in adults.

- There is no “adult onset” ADHD. Although ADHD may manifest itself differently in adults than in children, studies indicate that the disorder is a continuation of childhood ADHD rather than a discrete adult disorder. Clinicians thus need to establish that adult patients exhibited symptomatic and functional impairment before age 7 (as per DSM-IV), although some experts suggest preadolescence as a cutoff.1

- Most people do not “outgrow” ADHD. We once assumed that most patients with ADHD became asymptomatic as they matured from adolescence into adulthood. Research reveals that hyperactivity and impulsivity decline over time but inattention and executive dysfunction usually persist into adulthood.2 These residual deficits cause continued vocational, academic, and interpersonal difficulties.

- ADHD can mimic other psychiatric disorders. The hyperkinesis, impulsivity, and inattention that are the essence of ADHD are also commonly observed in adults with anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance abuse problems, and learning disorders. Patients who present with atypical affective or anxiety symptoms or learning problems, or who do not respond to conventional treatments, should be screened for ADHD.

- The genetic apple does not fall far from the tree in ADHD. Many adults with ADHD are identified in middle age after their children are diagnosed. Adoption data and multiple twin studies have placed the heritability of ADHD at approximately 75%,3 putting first-degree relatives at fairly high predisposition.

- Stimulant medications do not promote substance abuse in ADHD patients. Stimulant medication is more likely to reduce the risk of substance abuse in ADHD than enhance it.4 For patients at high-risk for substance abuse disorders, however, atomoxetine and bupropion offer nonstimulant alternatives. Also, the newer, longer-acting dextroamphetamine/amphetamine and methylphenidate preparations are more difficult to abuse because of their slow-release mechanisms.

1. Barkley RA, Biederman J. Toward a broader definition of the age-of-onset criteria for attention deficit disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1204-10.

2. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood as a function of reporting sources and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002;111:279-89.

3. Sprich S, Biederman J, Crawford MH, et al. Adoptive and biological families of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Am Acad. Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;143:1432-7.

4. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 1999;104:e20.-

Dr. Anders is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry, University Health Services, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

1. Barkley RA, Biederman J. Toward a broader definition of the age-of-onset criteria for attention deficit disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1204-10.

2. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood as a function of reporting sources and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002;111:279-89.

3. Sprich S, Biederman J, Crawford MH, et al. Adoptive and biological families of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Am Acad. Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;143:1432-7.

4. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 1999;104:e20.-

Dr. Anders is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry, University Health Services, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Treating bipolar disorder during pregnancy: No time for endless debate

To me, the main difference between MDs and PhDs* is that MDs—at some point—must stop gathering data and make decisions.

I once heard Dr. Albert (Mickey) Stunkard say that when he was a physician fellow at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences he was at first energized—and a little intimidated—by the scintillating conversations taking place around him. Eventually, though, all the discourse reminded him of those long, philosophical discussions he and his classmates had had in their college dorms (“Well, on one hand you have communism, and on the other hand you have fascism… ”).

Physicians do not have the luxury of endless debate. At some point, we need to do something or else let our patients die of old age while waiting. One issue about which I have had to make decisions over the years—and which has troubled me the most—is whether to treat pregnant patients with psychotropics. Generally, I try to avoid using drugs in these cases, but sometimes I decide that the mother’s need for drug therapy outweighs the potential risks to her offspring.

Dr. Lori Altshuler and colleagues’ article in this issue is the best summary I have seen of what is known about the risks of using psychotropics in pregnant bipolar women. Each time I treat a woman with bipolar disorder, I will remember this discussion and the algorithm these authors suggest for making therapeutic decisions.

This excellent article may not be the final word on the subject. It can, however, help us with an important clinical decision we often have to make—and that is what Current Psychiatry is all about.

To me, the main difference between MDs and PhDs* is that MDs—at some point—must stop gathering data and make decisions.

I once heard Dr. Albert (Mickey) Stunkard say that when he was a physician fellow at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences he was at first energized—and a little intimidated—by the scintillating conversations taking place around him. Eventually, though, all the discourse reminded him of those long, philosophical discussions he and his classmates had had in their college dorms (“Well, on one hand you have communism, and on the other hand you have fascism… ”).

Physicians do not have the luxury of endless debate. At some point, we need to do something or else let our patients die of old age while waiting. One issue about which I have had to make decisions over the years—and which has troubled me the most—is whether to treat pregnant patients with psychotropics. Generally, I try to avoid using drugs in these cases, but sometimes I decide that the mother’s need for drug therapy outweighs the potential risks to her offspring.

Dr. Lori Altshuler and colleagues’ article in this issue is the best summary I have seen of what is known about the risks of using psychotropics in pregnant bipolar women. Each time I treat a woman with bipolar disorder, I will remember this discussion and the algorithm these authors suggest for making therapeutic decisions.

This excellent article may not be the final word on the subject. It can, however, help us with an important clinical decision we often have to make—and that is what Current Psychiatry is all about.

To me, the main difference between MDs and PhDs* is that MDs—at some point—must stop gathering data and make decisions.

I once heard Dr. Albert (Mickey) Stunkard say that when he was a physician fellow at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences he was at first energized—and a little intimidated—by the scintillating conversations taking place around him. Eventually, though, all the discourse reminded him of those long, philosophical discussions he and his classmates had had in their college dorms (“Well, on one hand you have communism, and on the other hand you have fascism… ”).

Physicians do not have the luxury of endless debate. At some point, we need to do something or else let our patients die of old age while waiting. One issue about which I have had to make decisions over the years—and which has troubled me the most—is whether to treat pregnant patients with psychotropics. Generally, I try to avoid using drugs in these cases, but sometimes I decide that the mother’s need for drug therapy outweighs the potential risks to her offspring.

Dr. Lori Altshuler and colleagues’ article in this issue is the best summary I have seen of what is known about the risks of using psychotropics in pregnant bipolar women. Each time I treat a woman with bipolar disorder, I will remember this discussion and the algorithm these authors suggest for making therapeutic decisions.

This excellent article may not be the final word on the subject. It can, however, help us with an important clinical decision we often have to make—and that is what Current Psychiatry is all about.

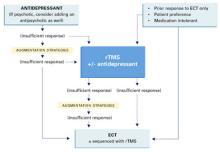

Therapy-resistant major depression The attraction of magnetism: How effective—and safe—is rTMS?

Using magnets to improve health is sometimes hawked in dubious classified ads and “infomercials.” However, a legitimate use of magnetism—repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)—is showing promise in treating severe depression (Box) 1-4 and other psychiatric disorders.

Patients or their families are likely to ask psychiatrists about rTMS as more becomes known about this investigational technology. Drawing from our experience and the evidence, we offer an update on whether rTMS may be an alternative for treating depression and address issues that must be resolved before it could be used in clinical practice.

WHAT IS RTMS?

rTMS consists of a series of magnetic pulses produced by a stimulator, which can be adjusted for:

- coil type and placement

- stimulation site, intensity, frequency, and number

- amount of time between stimulations

- treatment duration.

In 1985, Barker and colleagues developed single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation to examine motor cortex function.1 The single-pulse mechanism they discovered was subsequently adapted to deliver repetitive pulses and is referred to as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

How rTMS works. Transcranial magnetic stimulation uses an electromagnetic coil applied to the head to produce an intense, localized, fluctuating magnetic field that passes unimpeded into a small area of the brain, inducing an electrical current. This results in neuronal depolarization in a localized area under the coil, and possibly distal effects as well.2 During the neurophysiological studies, it was discovered that subjects also experienced a change in mood.

Antidepressant effects. Similar physiologic effects induced by rTMS, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and antidepressants on the endocrine system, sleep parameters, and biochemical measures suggest antidepressant properties.3 In 1993, the first published study examining rTMS in psychiatric patients reported reduced depressive symptoms in two subjects.4 Since then, several clinical trials have examined rTMS’ antidepressive effects. In 2001, Canada’s Health Ministry approved rTMS for treating major depression. In the United States, rTMS remains investigational and is FDA-approved only for clinical trials.

Coil type and placement. Initial studies involved stimulation—typically low-frequency—over the vertex, but most subsequent rTMS trials in depression have stimulated the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroimaging studies have shown prefrontal functioning abnormalities in depressed subjects, and it is hypothesized that stimulating this area (plus possible distal effects) may produce an antidepressant effect.5