User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Methotrexate is a safe and efficacious alternative to ciclosporin in children with severe AD

Key clinical point: Both ciclosporin and methotrexate were effective against severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in children, but ciclosporin resulted in a more rapid response whereas methotrexate led to more sustained disease control even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: At 12 weeks, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved 50% improvement in Objective Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis scores (o-SCORAD-50) with ciclosporin vs methotrexate (P = .012). However, at 60 weeks, the proportion of patients who achieved o-SCORAD-50 was higher with methotrexate vs ciclosporin (P = .022). Adverse event rates were comparable in both groups.

Study details: The TREatment of severe Atopic Eczema Trial included 103 children with severe AD (age 2-16 years) who were unresponsive to topical treatments and were randomly assigned to receive ciclosporin or methotrexate.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Some authors, including the lead author, declared receiving consulting fees, advisory fees, or research funding from various sources, including UK NIHR.

Source: Flohr C et al and the TREAT Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of ciclosporin versus methotrexate in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children and young people (TREAT): A multicentre, parallel group, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Sep 19). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad281

Key clinical point: Both ciclosporin and methotrexate were effective against severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in children, but ciclosporin resulted in a more rapid response whereas methotrexate led to more sustained disease control even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: At 12 weeks, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved 50% improvement in Objective Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis scores (o-SCORAD-50) with ciclosporin vs methotrexate (P = .012). However, at 60 weeks, the proportion of patients who achieved o-SCORAD-50 was higher with methotrexate vs ciclosporin (P = .022). Adverse event rates were comparable in both groups.

Study details: The TREatment of severe Atopic Eczema Trial included 103 children with severe AD (age 2-16 years) who were unresponsive to topical treatments and were randomly assigned to receive ciclosporin or methotrexate.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Some authors, including the lead author, declared receiving consulting fees, advisory fees, or research funding from various sources, including UK NIHR.

Source: Flohr C et al and the TREAT Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of ciclosporin versus methotrexate in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children and young people (TREAT): A multicentre, parallel group, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Sep 19). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad281

Key clinical point: Both ciclosporin and methotrexate were effective against severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in children, but ciclosporin resulted in a more rapid response whereas methotrexate led to more sustained disease control even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: At 12 weeks, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved 50% improvement in Objective Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis scores (o-SCORAD-50) with ciclosporin vs methotrexate (P = .012). However, at 60 weeks, the proportion of patients who achieved o-SCORAD-50 was higher with methotrexate vs ciclosporin (P = .022). Adverse event rates were comparable in both groups.

Study details: The TREatment of severe Atopic Eczema Trial included 103 children with severe AD (age 2-16 years) who were unresponsive to topical treatments and were randomly assigned to receive ciclosporin or methotrexate.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Some authors, including the lead author, declared receiving consulting fees, advisory fees, or research funding from various sources, including UK NIHR.

Source: Flohr C et al and the TREAT Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of ciclosporin versus methotrexate in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children and young people (TREAT): A multicentre, parallel group, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Sep 19). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad281

Children with atopic dermatitis more prone to allergic contact dermatitis

Key clinical point: Compared with children without atopic dermatitis (AD), those with AD are significantly more likely to have positive patch tests (PPT) and respond to ≥1 allergen on patch testing.

Major finding: Children with vs without AD were significantly more likely to have a longer duration of dermatitis (P < .0001), >1 PPT result (P = .005), a greater number of PPT overall (P = .012), and a more generalized distribution of dermatitis (P = .001) as well as PPT to bacitracin (P = .030), carba mix (diphenylguanidine, zinc dibutyldithiocarbamate, and zinc diethyldithiocarbamate) (P = .025), and cocamidopropyl betaine (P = .0007).

Study details: This retrospective case-control study included 615 children with AD and 297 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation, Evanston, IL. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Johnson H et al. Prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis in children with and without atopic dermatitis: A multicenter retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(5):1007-1014 (Sep 25). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.048

Key clinical point: Compared with children without atopic dermatitis (AD), those with AD are significantly more likely to have positive patch tests (PPT) and respond to ≥1 allergen on patch testing.

Major finding: Children with vs without AD were significantly more likely to have a longer duration of dermatitis (P < .0001), >1 PPT result (P = .005), a greater number of PPT overall (P = .012), and a more generalized distribution of dermatitis (P = .001) as well as PPT to bacitracin (P = .030), carba mix (diphenylguanidine, zinc dibutyldithiocarbamate, and zinc diethyldithiocarbamate) (P = .025), and cocamidopropyl betaine (P = .0007).

Study details: This retrospective case-control study included 615 children with AD and 297 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation, Evanston, IL. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Johnson H et al. Prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis in children with and without atopic dermatitis: A multicenter retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(5):1007-1014 (Sep 25). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.048

Key clinical point: Compared with children without atopic dermatitis (AD), those with AD are significantly more likely to have positive patch tests (PPT) and respond to ≥1 allergen on patch testing.

Major finding: Children with vs without AD were significantly more likely to have a longer duration of dermatitis (P < .0001), >1 PPT result (P = .005), a greater number of PPT overall (P = .012), and a more generalized distribution of dermatitis (P = .001) as well as PPT to bacitracin (P = .030), carba mix (diphenylguanidine, zinc dibutyldithiocarbamate, and zinc diethyldithiocarbamate) (P = .025), and cocamidopropyl betaine (P = .0007).

Study details: This retrospective case-control study included 615 children with AD and 297 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation, Evanston, IL. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Johnson H et al. Prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis in children with and without atopic dermatitis: A multicenter retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(5):1007-1014 (Sep 25). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.048

What’s Eating You? Phlebotomine Sandflies and Leishmania Parasites

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4 Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

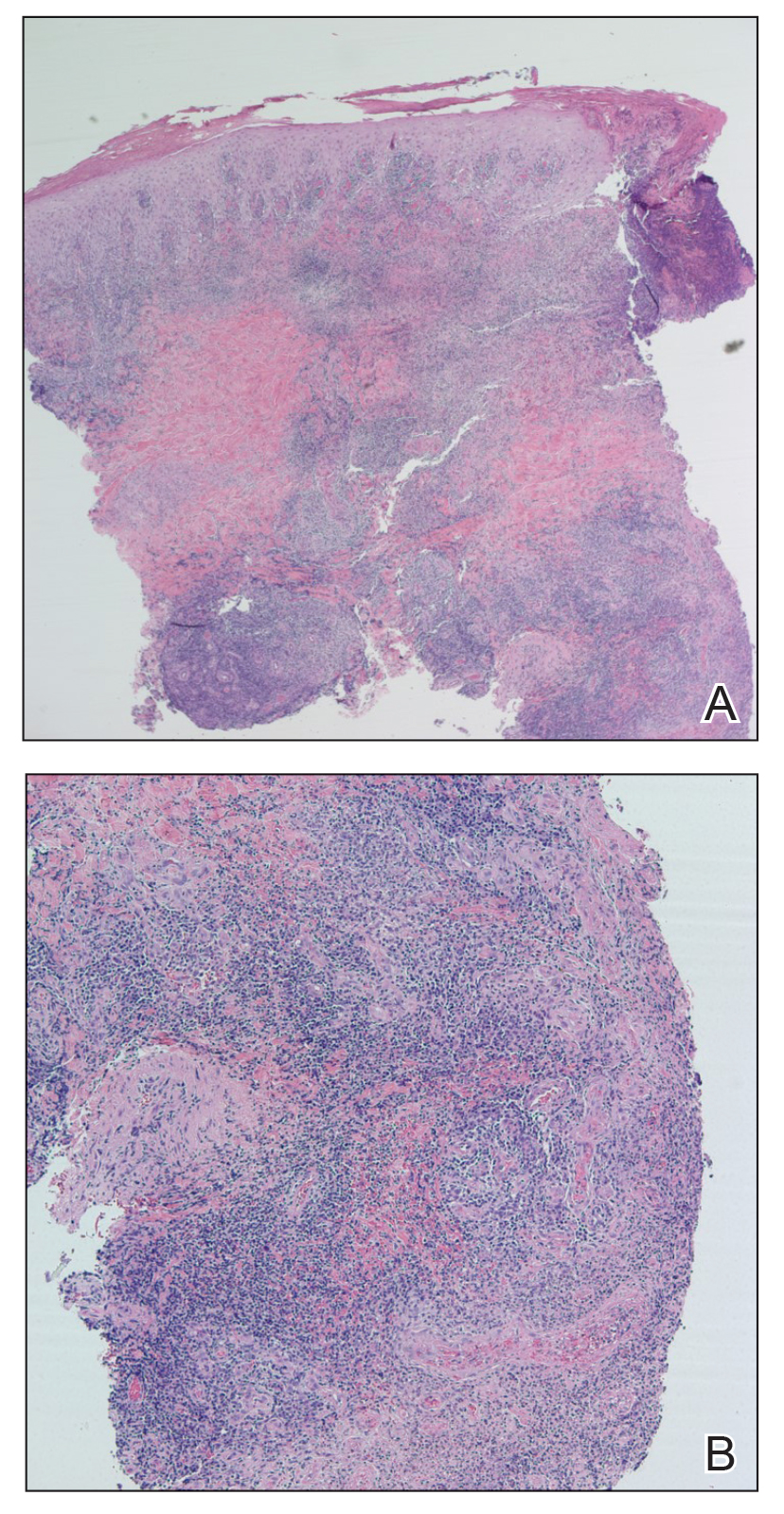

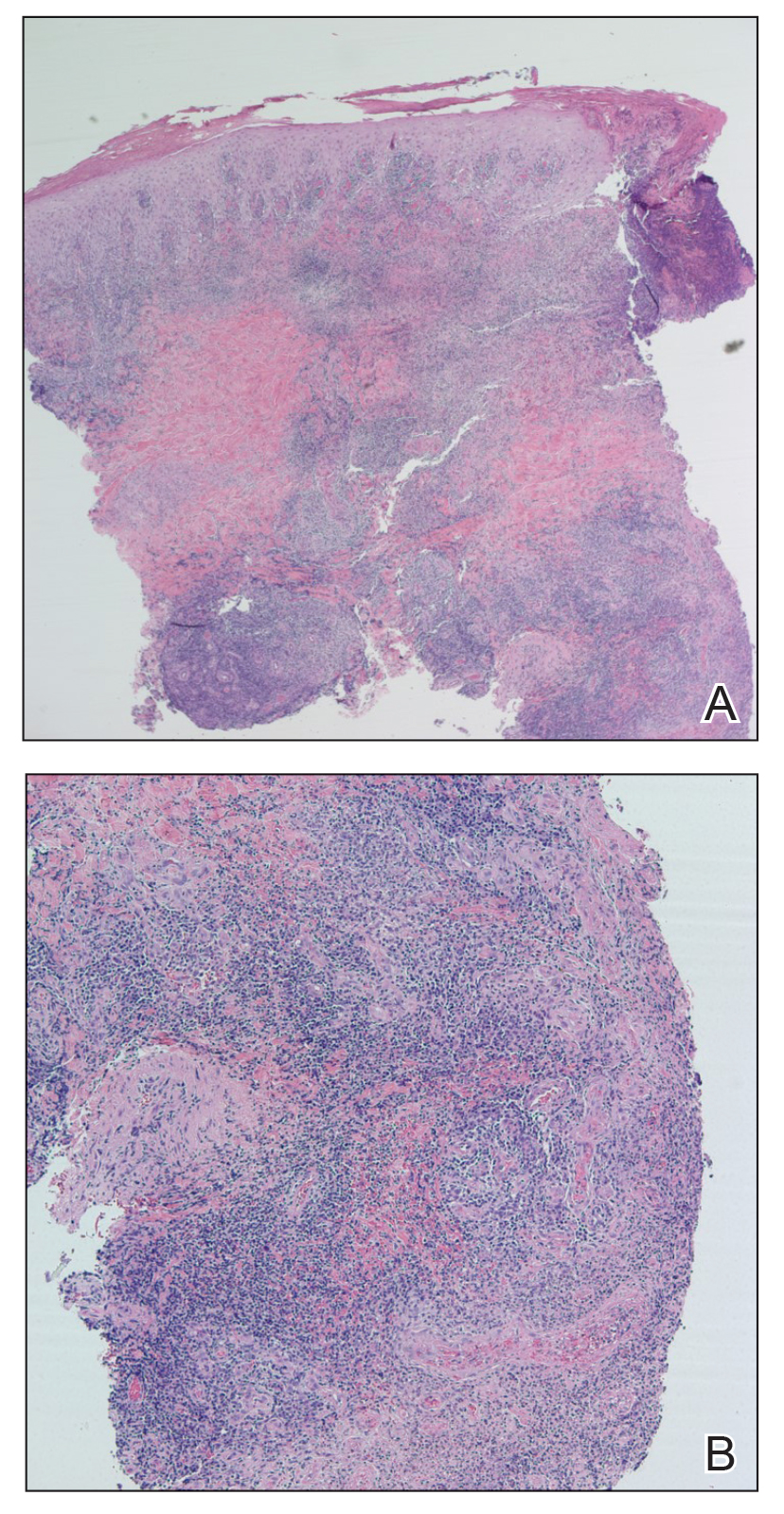

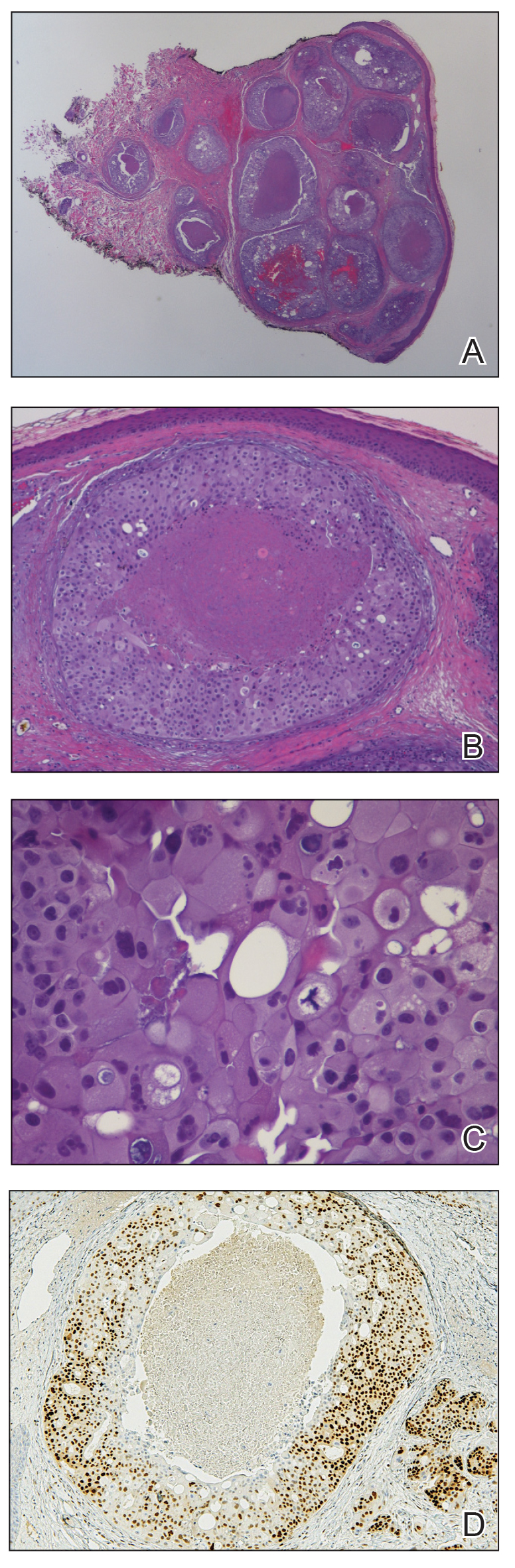

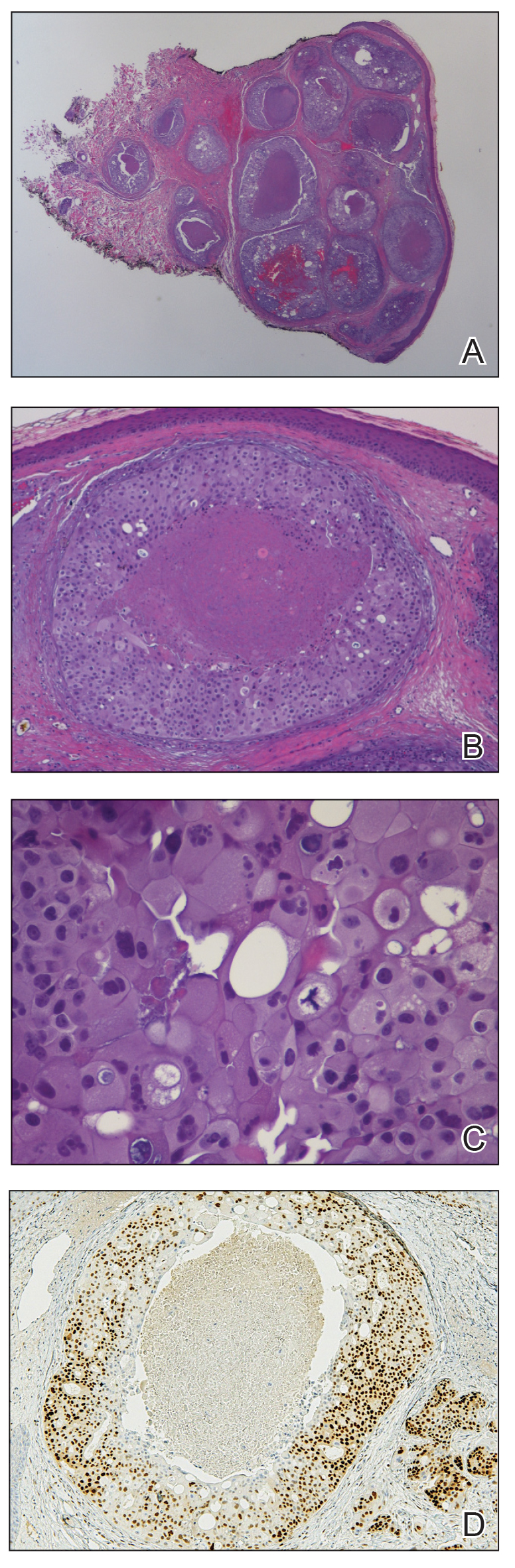

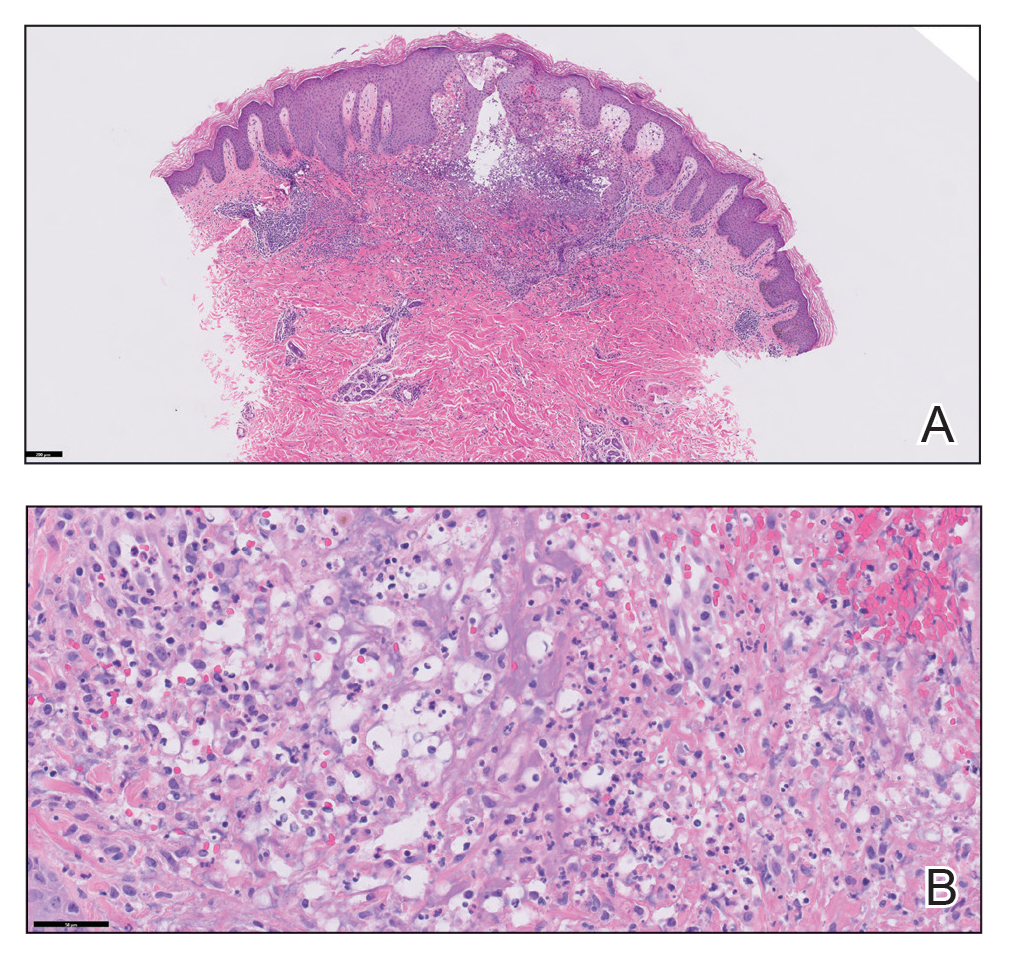

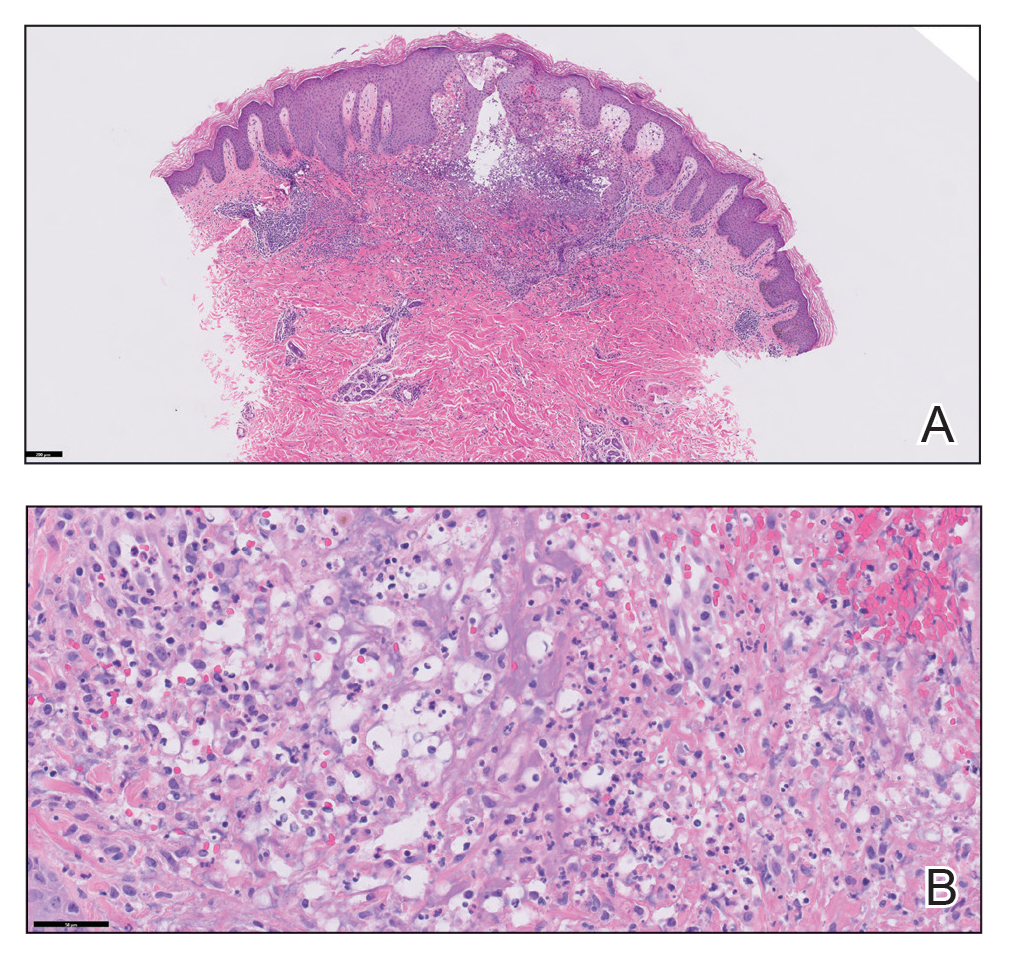

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4 Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

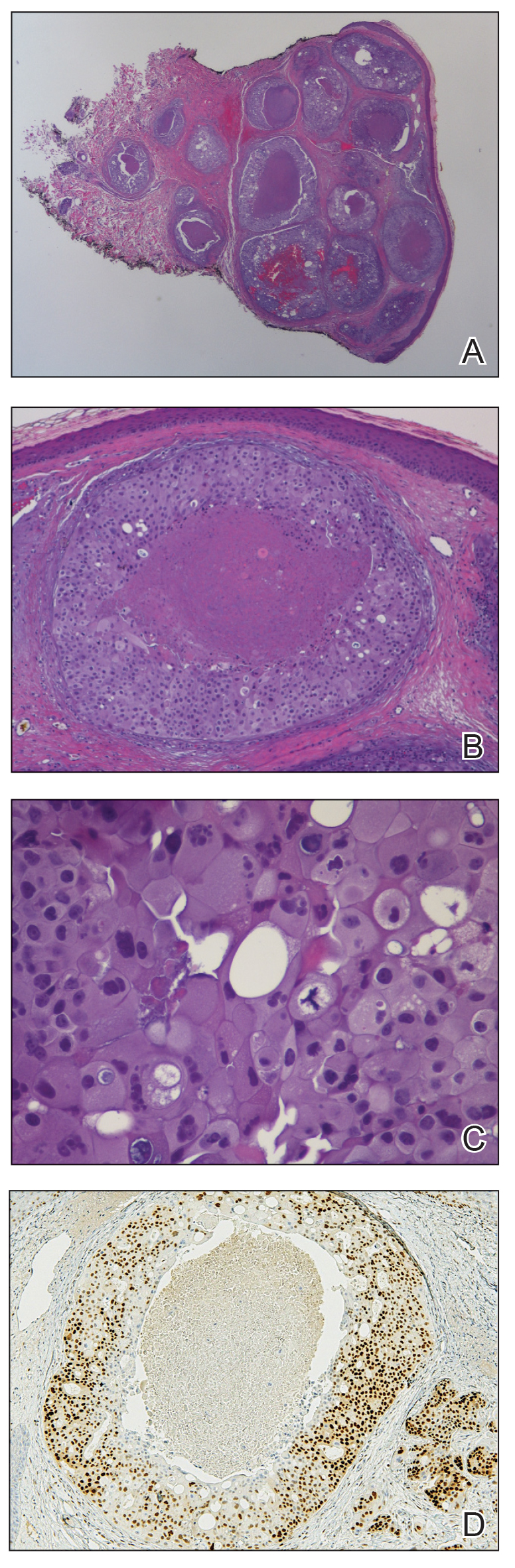

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4 Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

Practice Points

- The Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia genera of sandflies are vectors of Leishmania parasites, which can result in an array of clinical findings associated with leishmaniasis.

- Treatment options for leishmaniasis differ based on whether the infection is considered uncomplicated or complicated, which depends on the species of Leishmania; the number, size, and location of the lesion(s); and host immune status.

- All US practitioners should be aware of this pathogen, especially with regard to patients who have a history of travel to other countries. Health care professionals in states such as Texas and Oklahoma should be especially cognizant because these constitute one of the few areas in the United States where locally acquired cases of leishmaniasis have been reported.

Atopic Dermatitis Triggered by Omalizumab and Treated With Dupilumab

To the Editor:

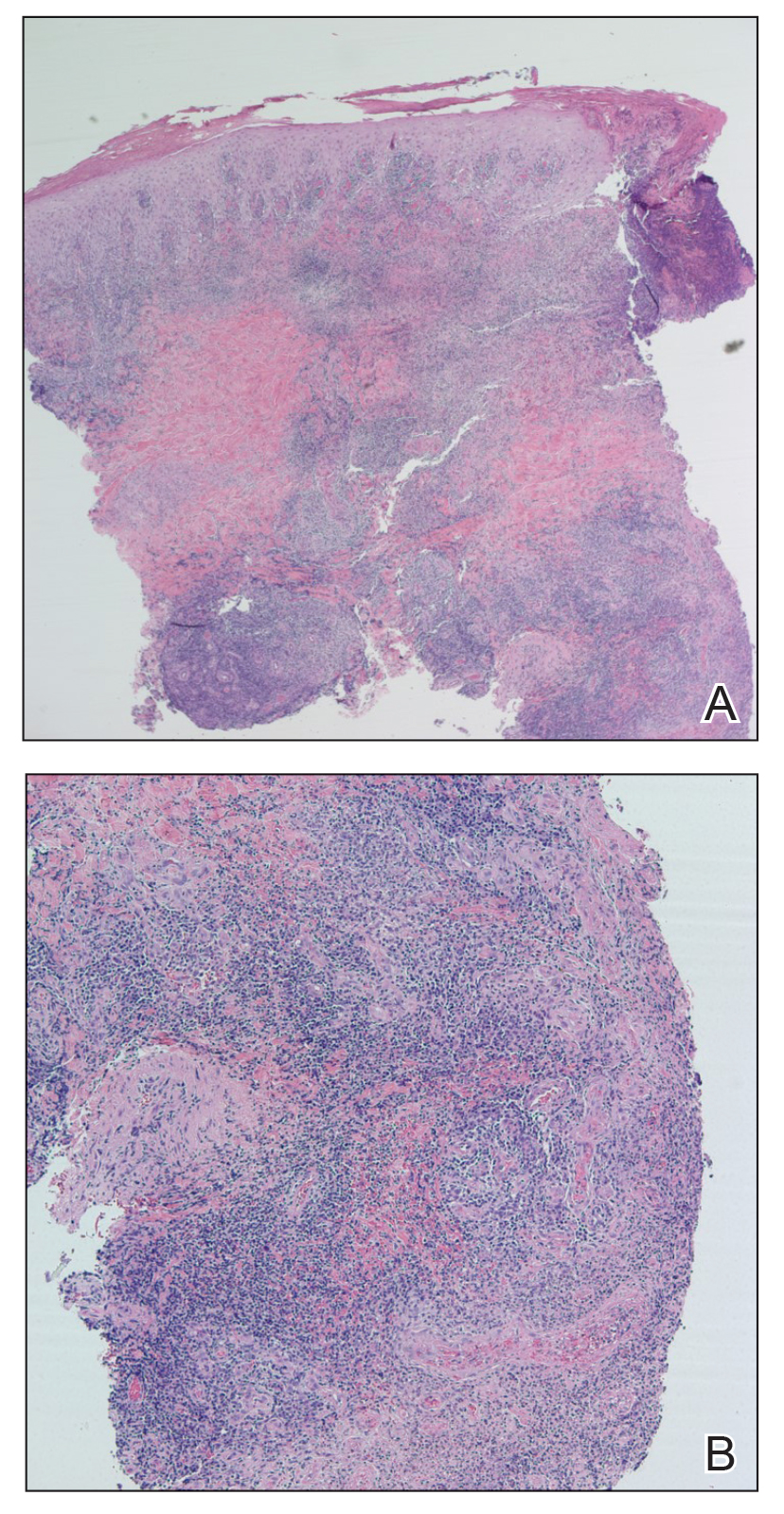

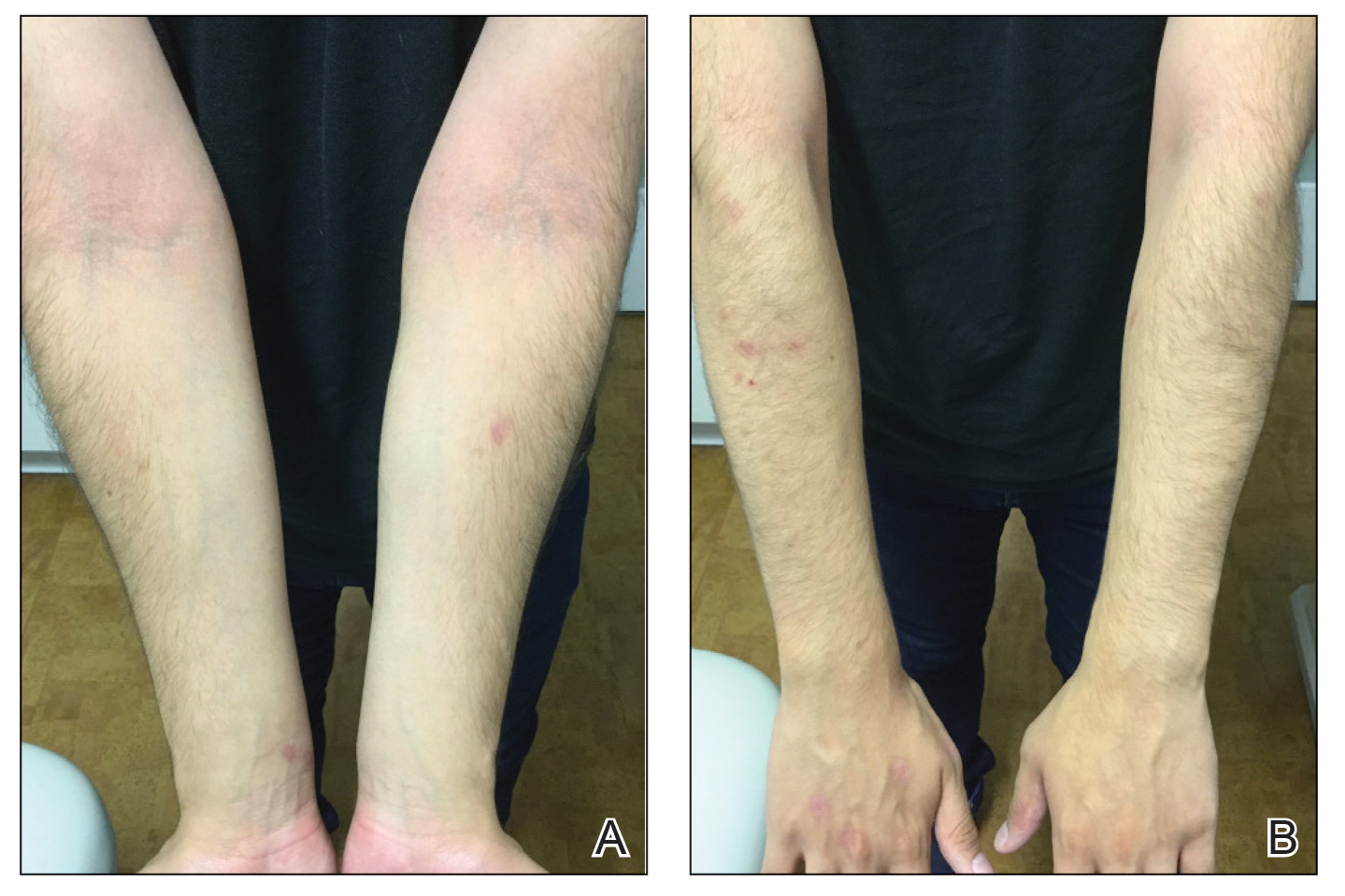

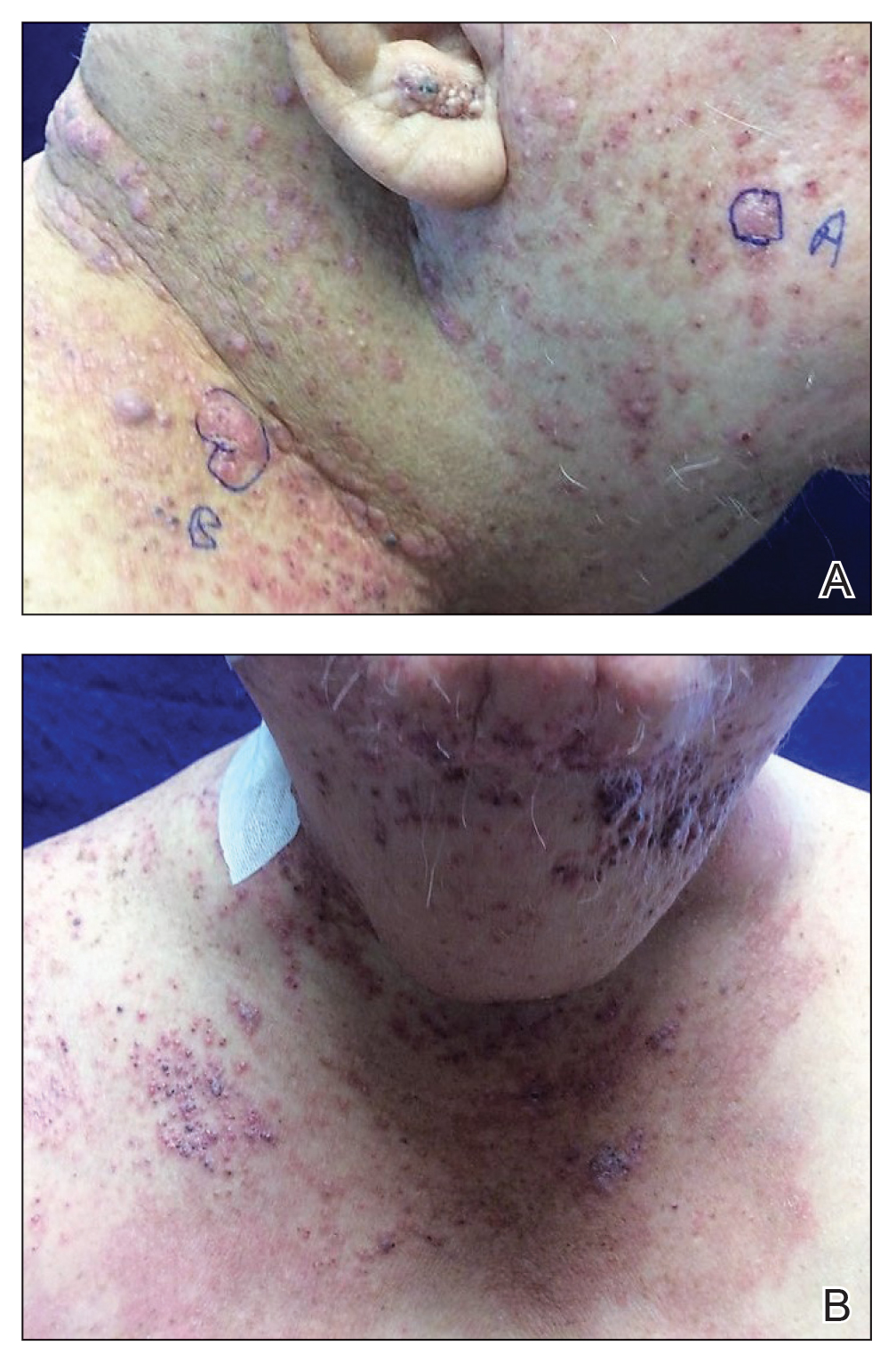

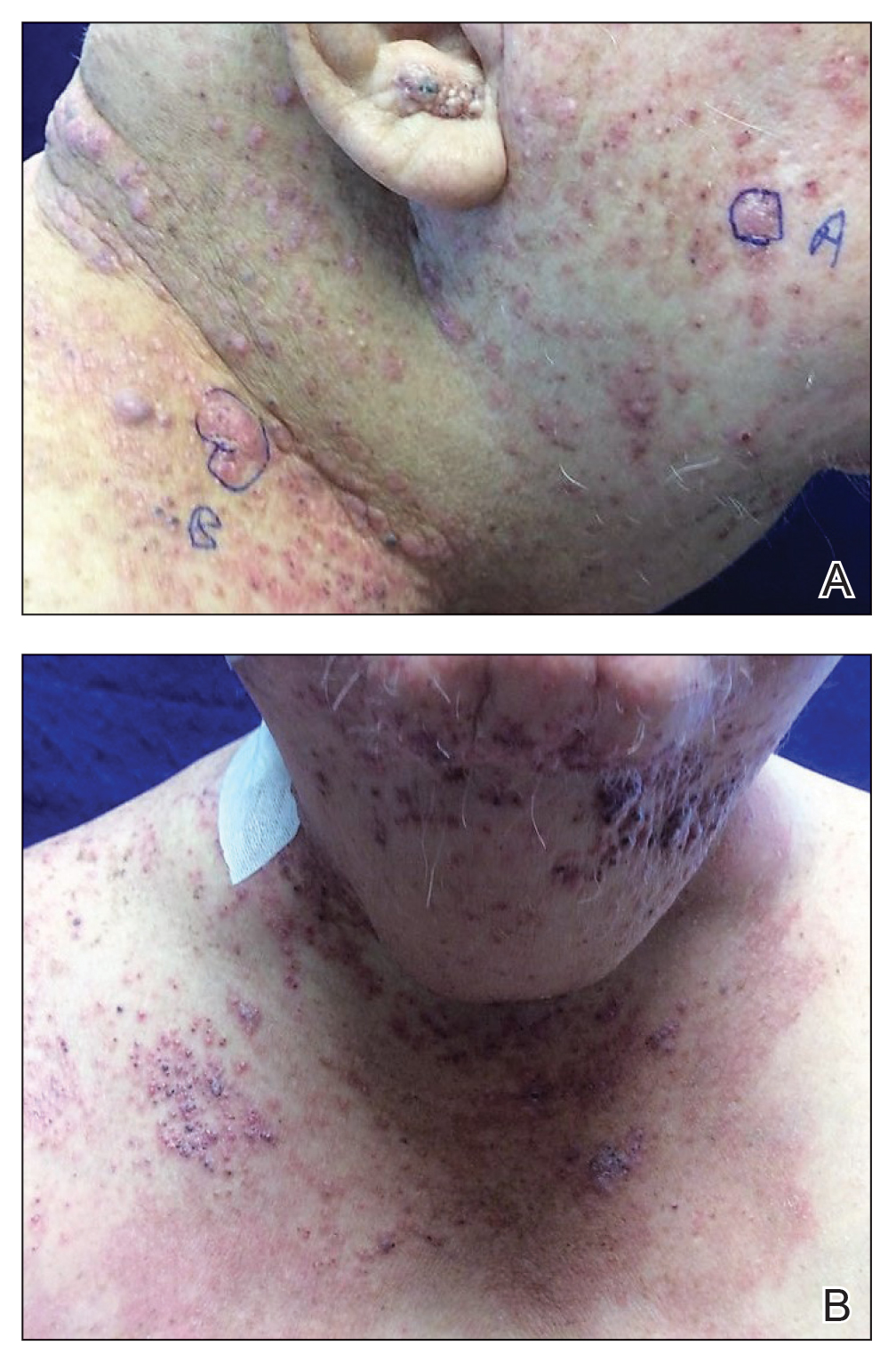

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

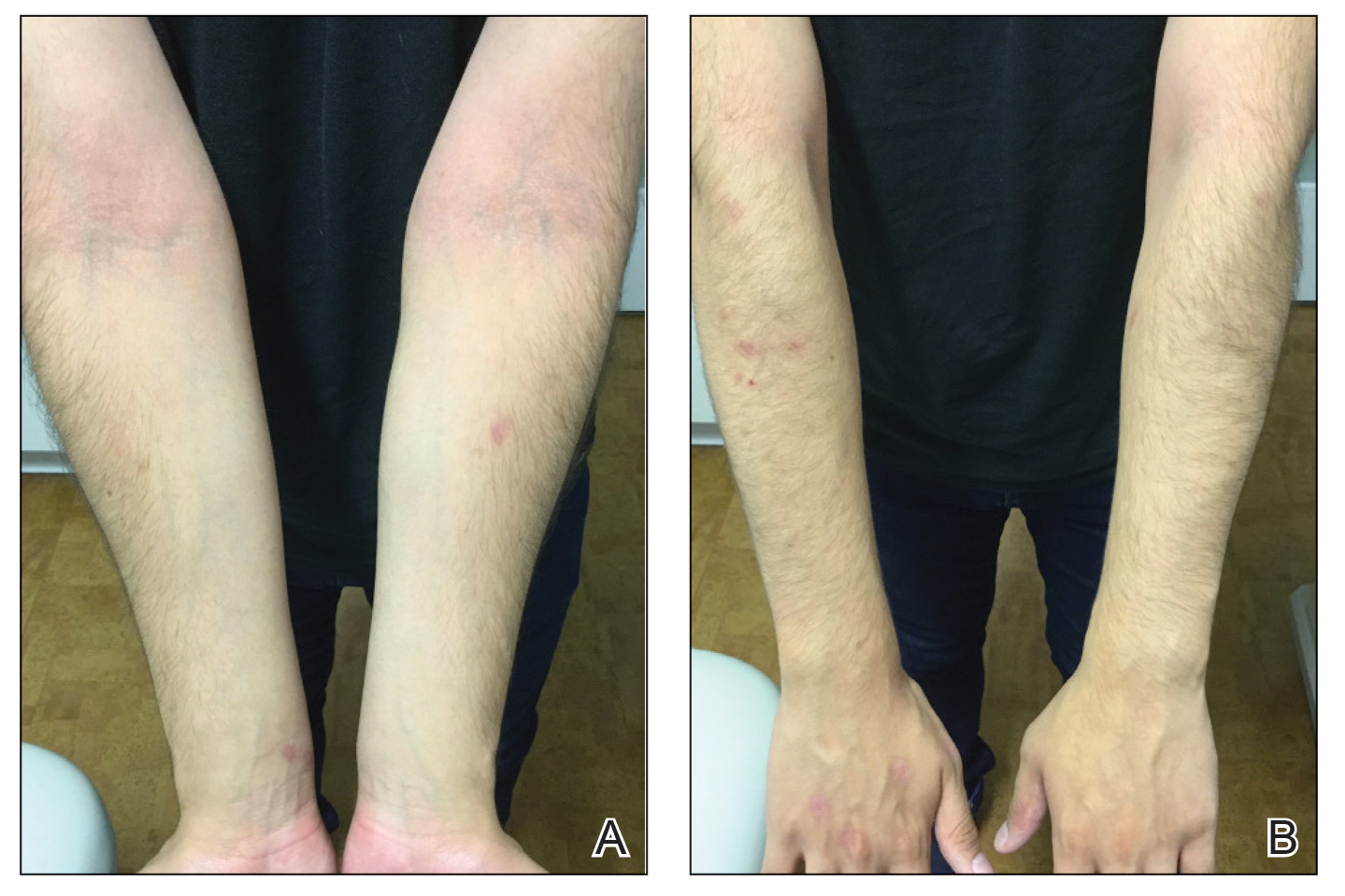

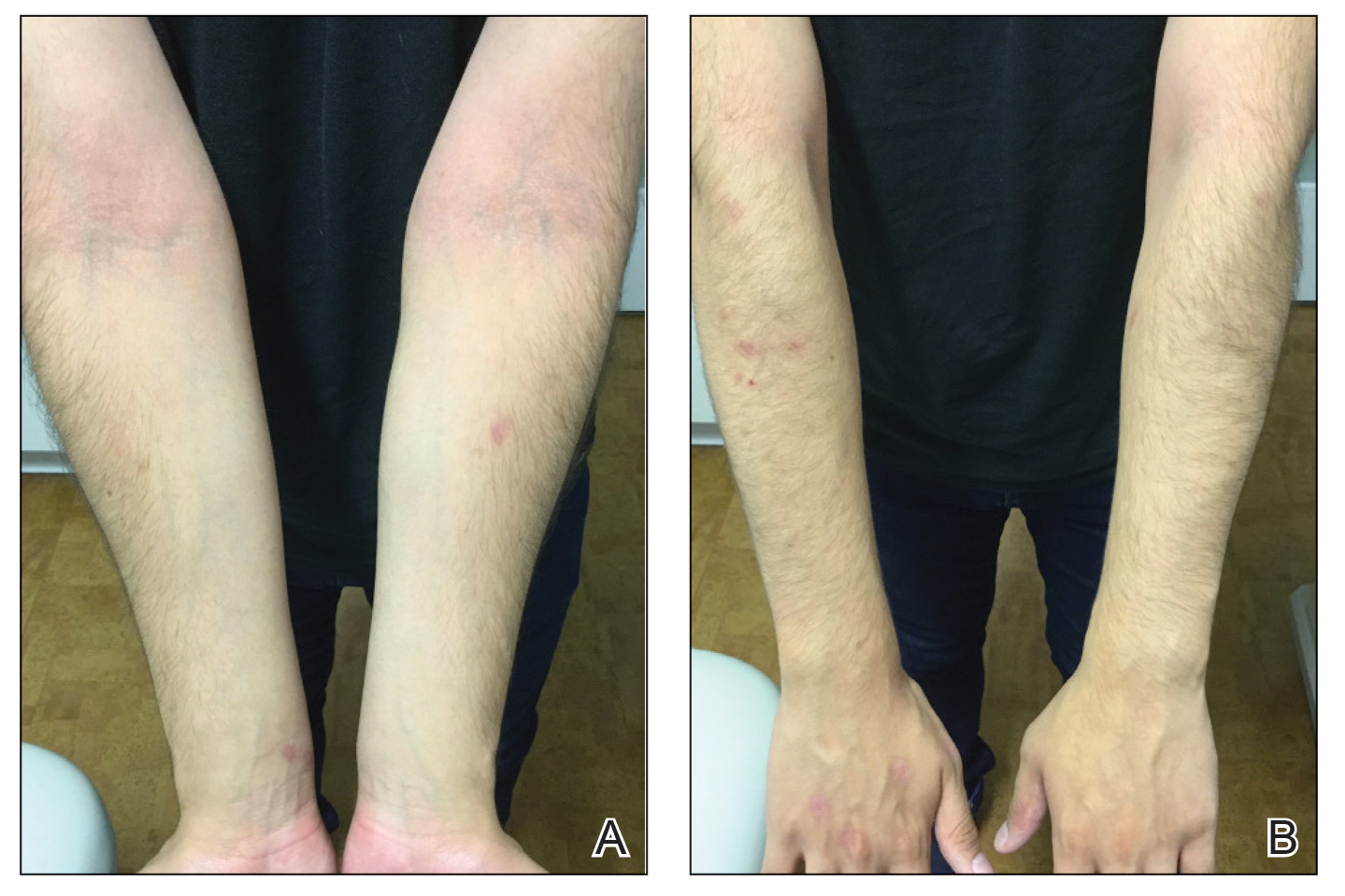

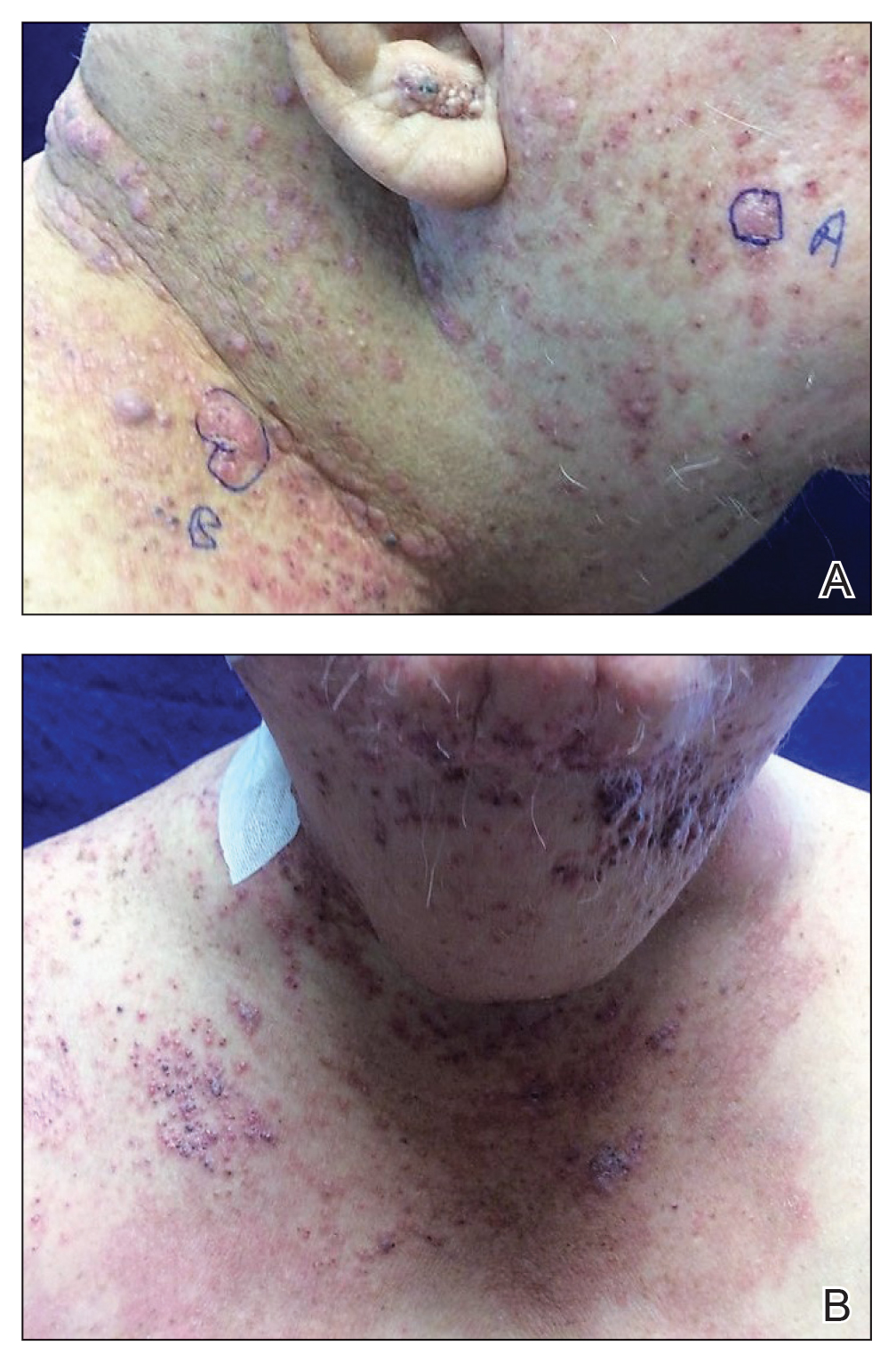

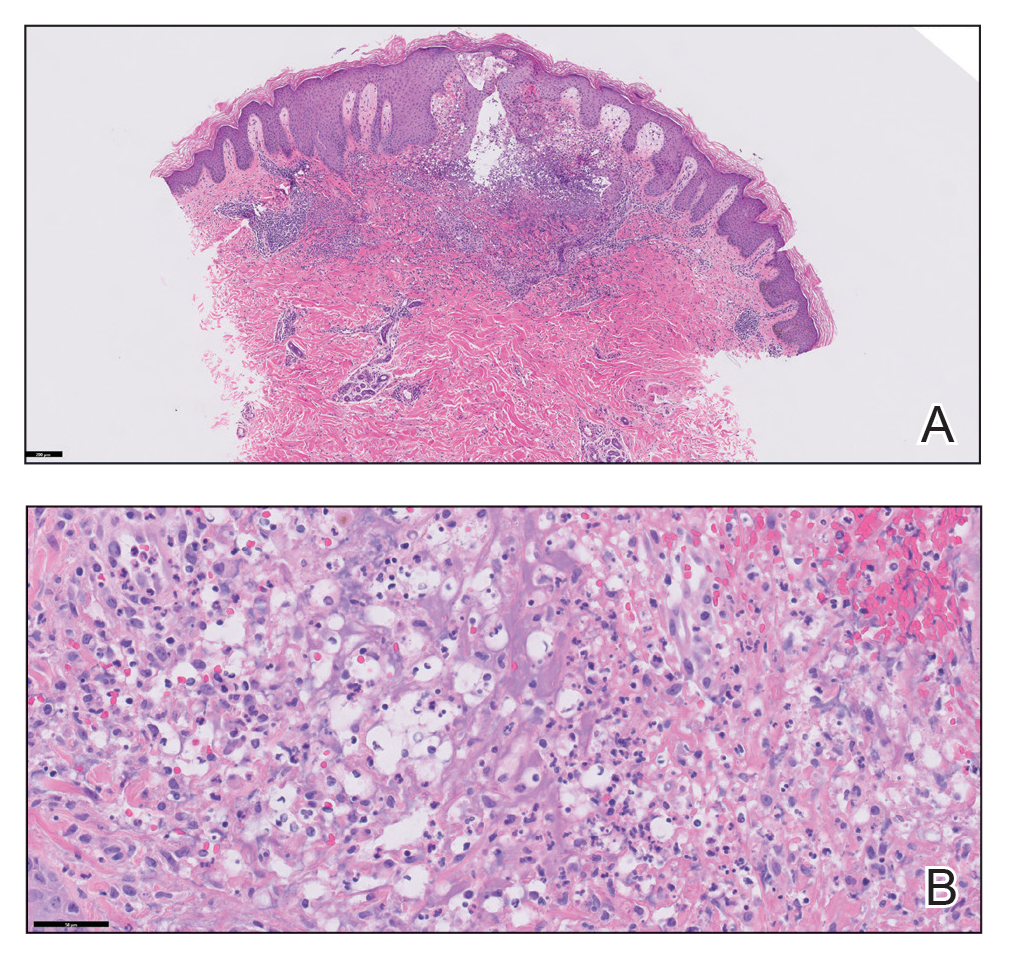

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

Practice Points

- Monoclonal antibodies are promising therapies for atopic conditions, although its efficacy for atopic dermatitis (AD) is debated and the side-effect profile is not entirely known.

- Omalizumab may cause a paradoxical exacerbation of AD in select patients analogous to tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis.

Suits or joggers? A doctor’s dress code

Look at this guy – NFL Chargers jersey and shorts with a RVCA hat on backward. And next to him, a woman wearing her spin-class-Lulu gear. There’s also a guy sporting a 2016 San Diego Rock ‘n Roll Marathon Tee. And that young woman is actually wearing slippers. A visitor from the 1950s would be thunderstruck to see such casual wear on people waiting to board a plane. Photos from that era show men buttoned up in white shirt and tie and women wearing Chanel with hats and white gloves. This dramatic transformation from formal to unfussy wear cuts through all social situations, including in my office. As a new doc out of residency, I used to wear a tie and shoes that could hold a shine. Now I wear jogger scrubs and sneakers. Rather than be offended by the lack of formality though, patients seem to appreciate it. Should they?

At first glance this seems to be a modern phenomenon. The reasons for casual wear today are manifold: about one-third of people work from home, Millennials are taking over with their TikTok values and general irreverence, COVID made us all fat and lazy. Heck, even the U.S. Senate briefly abolished the requirement to wear suits on the Senate floor. But getting dressed up was never to signal that you are elite or superior to others. It’s the opposite. To get dressed is a signal that you are serving others, a tradition that is as old as society.

Think of Downton Abbey as an example. The servants were always required to be smartly dressed when working, whereas members of the family could be dressed up or not. It’s clear who is serving whom. This tradition lives today in the hospitality industry. When you mosey into the lobby of a luxury hotel in your Rainbow sandals you can expect everyone who greets you will be in finery, signaling that they put in effort to serve you. You’ll find the same for all staff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which is no coincidence.

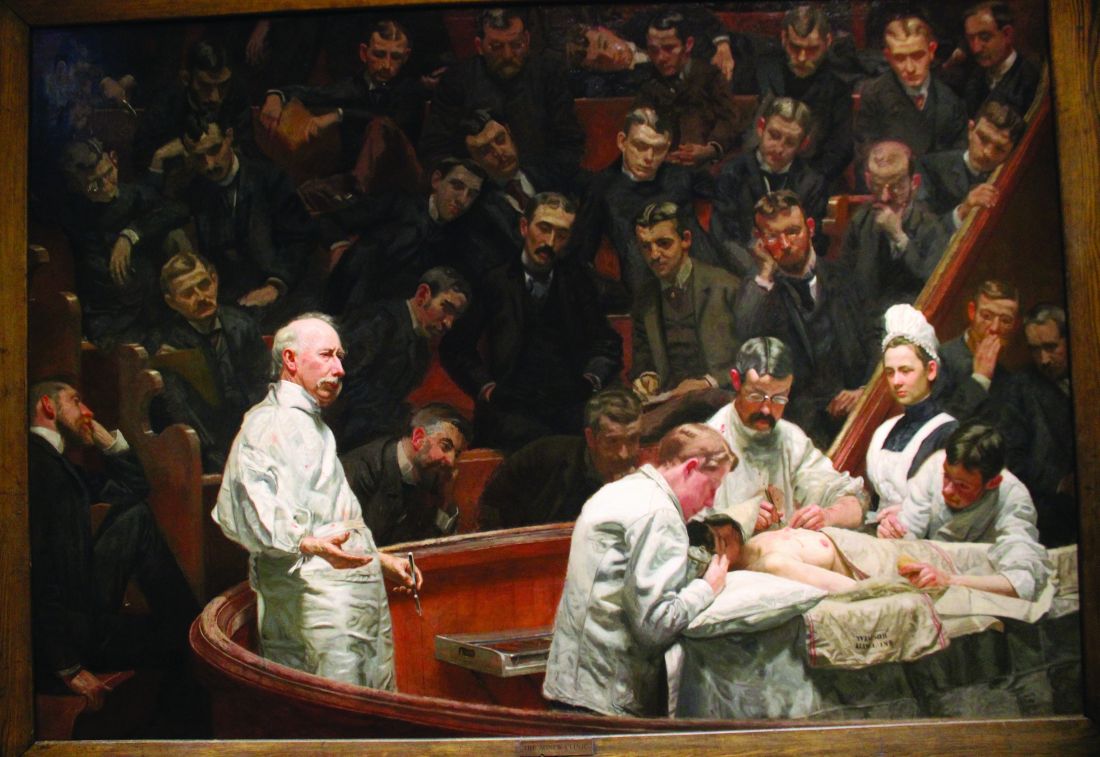

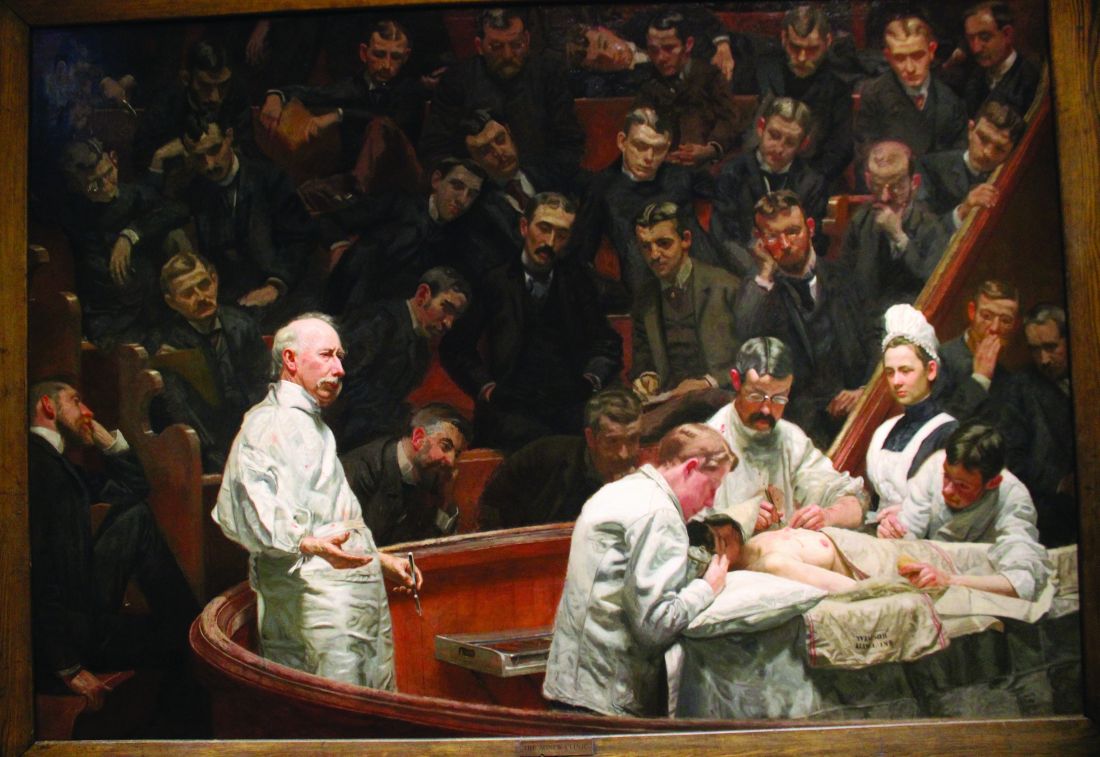

Suits used to be standard in medicine. In the 19th century, physicians wore formal black-tie when seeing patients. Unlike hospitality however, we had good reason to eschew the tradition: germs. Once we figured out that our pus-stained ties and jackets were doing harm, we switched to wearing sanitized uniforms. Casual wear for doctors isn’t a modern phenomenon after all, then. For proof, compare Thomas Eakins painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) with his later “The Agnew Clinic” (1889). In the former, Dr. Gross is portrayed in formal black wear, bloody hand and all. In the latter, Dr. Agnew is wearing white FIGS (or the 1890’s equivalent anyway). Similarly, nurses uniforms traditionally resembled kitchen servants, with criss-cross aprons and floor length skirts. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that nurses stopped wearing dresses and white caps.

In the operating theater it’s obviously critical that we wear sanitized scrubs to mitigate the risk of infection. Originally white to signal cleanliness, scrubs were changed to blue-green because surgeons were blinded by the lights bouncing off the uniforms. (Green is also opposite red on the color wheel, supposedly enhancing the ability to distinguish shades of red).

But Over time we’ve lost significant autonomy in our practice and lost a little respect from our patients. Payers tell us what to do. Patients question our expertise. Choosing what we wear is one of the few bits of medicine we still have agency. Pewter or pink, joggers or cargo pants, we get to choose.

The last time I flew British Airways everyone was in lounge wear, except the flight crew, of course. They were all smartly dressed. Recently British Airways rolled out updated, slightly more relaxed dress codes. Very modern, but I wonder if in a way we’re not all just a bit worse off.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

Look at this guy – NFL Chargers jersey and shorts with a RVCA hat on backward. And next to him, a woman wearing her spin-class-Lulu gear. There’s also a guy sporting a 2016 San Diego Rock ‘n Roll Marathon Tee. And that young woman is actually wearing slippers. A visitor from the 1950s would be thunderstruck to see such casual wear on people waiting to board a plane. Photos from that era show men buttoned up in white shirt and tie and women wearing Chanel with hats and white gloves. This dramatic transformation from formal to unfussy wear cuts through all social situations, including in my office. As a new doc out of residency, I used to wear a tie and shoes that could hold a shine. Now I wear jogger scrubs and sneakers. Rather than be offended by the lack of formality though, patients seem to appreciate it. Should they?

At first glance this seems to be a modern phenomenon. The reasons for casual wear today are manifold: about one-third of people work from home, Millennials are taking over with their TikTok values and general irreverence, COVID made us all fat and lazy. Heck, even the U.S. Senate briefly abolished the requirement to wear suits on the Senate floor. But getting dressed up was never to signal that you are elite or superior to others. It’s the opposite. To get dressed is a signal that you are serving others, a tradition that is as old as society.

Think of Downton Abbey as an example. The servants were always required to be smartly dressed when working, whereas members of the family could be dressed up or not. It’s clear who is serving whom. This tradition lives today in the hospitality industry. When you mosey into the lobby of a luxury hotel in your Rainbow sandals you can expect everyone who greets you will be in finery, signaling that they put in effort to serve you. You’ll find the same for all staff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which is no coincidence.

Suits used to be standard in medicine. In the 19th century, physicians wore formal black-tie when seeing patients. Unlike hospitality however, we had good reason to eschew the tradition: germs. Once we figured out that our pus-stained ties and jackets were doing harm, we switched to wearing sanitized uniforms. Casual wear for doctors isn’t a modern phenomenon after all, then. For proof, compare Thomas Eakins painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) with his later “The Agnew Clinic” (1889). In the former, Dr. Gross is portrayed in formal black wear, bloody hand and all. In the latter, Dr. Agnew is wearing white FIGS (or the 1890’s equivalent anyway). Similarly, nurses uniforms traditionally resembled kitchen servants, with criss-cross aprons and floor length skirts. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that nurses stopped wearing dresses and white caps.

In the operating theater it’s obviously critical that we wear sanitized scrubs to mitigate the risk of infection. Originally white to signal cleanliness, scrubs were changed to blue-green because surgeons were blinded by the lights bouncing off the uniforms. (Green is also opposite red on the color wheel, supposedly enhancing the ability to distinguish shades of red).

But Over time we’ve lost significant autonomy in our practice and lost a little respect from our patients. Payers tell us what to do. Patients question our expertise. Choosing what we wear is one of the few bits of medicine we still have agency. Pewter or pink, joggers or cargo pants, we get to choose.

The last time I flew British Airways everyone was in lounge wear, except the flight crew, of course. They were all smartly dressed. Recently British Airways rolled out updated, slightly more relaxed dress codes. Very modern, but I wonder if in a way we’re not all just a bit worse off.