User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

CANVAS: Canagliflozin improved renal outcomes in diabetes

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

REPORTING FROM SCM 18

Key clinical point: Canagliflozin improved kidney function and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Reduction in risk of a composite endpoint (end-stage kidney disease, renal death, or at least 40% decline in eGFR) was 47% for patients with preserved baseline kidney function and 24% for patients with reduced baseline function.

Study details: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of 10,140 patients (CANVAS and CANVAS-R).

Disclosures: Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials.

Source: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

VIDEO: Real-world findings on hybrid closed-loop insulin system

BOSTON – Real-world experience with the Medtronic MiniMed 670G, a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system, showed the device was associated with improved average glucose readings and more time in euglycemia in 26 patients with type 1 diabetes.

The findings go beyond the safety data from the clinical trial of the MiniMed 670G system, Kathryn Weaver, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her colleagues reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The clinical trial included a 2-week run-in period during which the system was used in manual mode before it was switched to automated mode. Mean sensor glucose readings for participants went from 150.2 mg/dL during run-in to 150.8 mg/dL at the end of 3 months, which was not a statistically significant difference (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1407-8).

In the real-world study, average sensor glucose readings dropped from a mean 169.46 mg/dL at baseline to 157.08 mg/dL at the end of the 3-month study period (P = .05). Also, the time spent with blood glucose levels greater than 180 mg/dL fell from 26.5% to 20% (P = .007), while the amount of time with glucose readings between 70 and 180 mg/dL increased from 61.7% to 71.1% (P = .02). Periods of hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia were already low at baseline and did not change, Dr. Weaver said.

“It is important to note that the initial pivotal trial was a study designed to evaluate safety not a study designed to evaluate effectiveness. And the [trial] group did demonstrate safety; they had a very significant reduction in the amount of hypoglycemia” with the pump, said Dr. Weaver. “We did not show a significant reduction in hypoglycemia in our [real-world] group, likely because we had a very low rate of hypoglycemia going into the study.”

Two of the study coauthors are employees of Medtronic, which manufactures the MiniMed 670G insulin pump/continuous glucose monitor. Medtronic did not provide funding support for the study or provide the closed-loop systems, and Dr. Weaver reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Weaver K et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 210.

BOSTON – Real-world experience with the Medtronic MiniMed 670G, a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system, showed the device was associated with improved average glucose readings and more time in euglycemia in 26 patients with type 1 diabetes.

The findings go beyond the safety data from the clinical trial of the MiniMed 670G system, Kathryn Weaver, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her colleagues reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The clinical trial included a 2-week run-in period during which the system was used in manual mode before it was switched to automated mode. Mean sensor glucose readings for participants went from 150.2 mg/dL during run-in to 150.8 mg/dL at the end of 3 months, which was not a statistically significant difference (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1407-8).

In the real-world study, average sensor glucose readings dropped from a mean 169.46 mg/dL at baseline to 157.08 mg/dL at the end of the 3-month study period (P = .05). Also, the time spent with blood glucose levels greater than 180 mg/dL fell from 26.5% to 20% (P = .007), while the amount of time with glucose readings between 70 and 180 mg/dL increased from 61.7% to 71.1% (P = .02). Periods of hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia were already low at baseline and did not change, Dr. Weaver said.

“It is important to note that the initial pivotal trial was a study designed to evaluate safety not a study designed to evaluate effectiveness. And the [trial] group did demonstrate safety; they had a very significant reduction in the amount of hypoglycemia” with the pump, said Dr. Weaver. “We did not show a significant reduction in hypoglycemia in our [real-world] group, likely because we had a very low rate of hypoglycemia going into the study.”

Two of the study coauthors are employees of Medtronic, which manufactures the MiniMed 670G insulin pump/continuous glucose monitor. Medtronic did not provide funding support for the study or provide the closed-loop systems, and Dr. Weaver reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Weaver K et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 210.

BOSTON – Real-world experience with the Medtronic MiniMed 670G, a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system, showed the device was associated with improved average glucose readings and more time in euglycemia in 26 patients with type 1 diabetes.

The findings go beyond the safety data from the clinical trial of the MiniMed 670G system, Kathryn Weaver, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her colleagues reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The clinical trial included a 2-week run-in period during which the system was used in manual mode before it was switched to automated mode. Mean sensor glucose readings for participants went from 150.2 mg/dL during run-in to 150.8 mg/dL at the end of 3 months, which was not a statistically significant difference (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1407-8).

In the real-world study, average sensor glucose readings dropped from a mean 169.46 mg/dL at baseline to 157.08 mg/dL at the end of the 3-month study period (P = .05). Also, the time spent with blood glucose levels greater than 180 mg/dL fell from 26.5% to 20% (P = .007), while the amount of time with glucose readings between 70 and 180 mg/dL increased from 61.7% to 71.1% (P = .02). Periods of hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia were already low at baseline and did not change, Dr. Weaver said.

“It is important to note that the initial pivotal trial was a study designed to evaluate safety not a study designed to evaluate effectiveness. And the [trial] group did demonstrate safety; they had a very significant reduction in the amount of hypoglycemia” with the pump, said Dr. Weaver. “We did not show a significant reduction in hypoglycemia in our [real-world] group, likely because we had a very low rate of hypoglycemia going into the study.”

Two of the study coauthors are employees of Medtronic, which manufactures the MiniMed 670G insulin pump/continuous glucose monitor. Medtronic did not provide funding support for the study or provide the closed-loop systems, and Dr. Weaver reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Weaver K et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 210.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2018

Trends in teen consumption of sports drinks are up and down

Although daily consumption of sports drinks decreased from 2010 to 2015 among teenagers, sugar-sweetened sports drinks still are popular, with numerous high school students drinking them at least weekly, said Kyla Cordery of the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, Lake Success, N.Y., and her associates.

Yet sports drink consumption in the previous week increased from 58% in 2010 to 60% in 2015 (P = .0002). And daily consumption of sports drinks also increased among teenagers watching television for more than 2 hours per day and among obese teens.

Boys were more than twice as likely as girls to drink one of more sports drinks daily (19% vs. 9%), as were more athletic/active children than those weren’t very athletic/active (18% vs. 10%).

“ Like many sugar-sweetened beverages, the excessive consumption of sports drinks is associated with weight gain, dental erosion, obesity, poor nutrition, and diabetes,” Ms. Cordery and her associates wrote. “The America Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Nutrition and Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness stated that the level of physical activity of the average child does not require the electrolyte replenishment offered by sports drinks.” Rehydration with water should be encouraged for most sports-related activities.

SOURCE: Cordery K et al. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2784.

Although daily consumption of sports drinks decreased from 2010 to 2015 among teenagers, sugar-sweetened sports drinks still are popular, with numerous high school students drinking them at least weekly, said Kyla Cordery of the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, Lake Success, N.Y., and her associates.

Yet sports drink consumption in the previous week increased from 58% in 2010 to 60% in 2015 (P = .0002). And daily consumption of sports drinks also increased among teenagers watching television for more than 2 hours per day and among obese teens.

Boys were more than twice as likely as girls to drink one of more sports drinks daily (19% vs. 9%), as were more athletic/active children than those weren’t very athletic/active (18% vs. 10%).

“ Like many sugar-sweetened beverages, the excessive consumption of sports drinks is associated with weight gain, dental erosion, obesity, poor nutrition, and diabetes,” Ms. Cordery and her associates wrote. “The America Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Nutrition and Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness stated that the level of physical activity of the average child does not require the electrolyte replenishment offered by sports drinks.” Rehydration with water should be encouraged for most sports-related activities.

SOURCE: Cordery K et al. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2784.

Although daily consumption of sports drinks decreased from 2010 to 2015 among teenagers, sugar-sweetened sports drinks still are popular, with numerous high school students drinking them at least weekly, said Kyla Cordery of the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, Lake Success, N.Y., and her associates.

Yet sports drink consumption in the previous week increased from 58% in 2010 to 60% in 2015 (P = .0002). And daily consumption of sports drinks also increased among teenagers watching television for more than 2 hours per day and among obese teens.

Boys were more than twice as likely as girls to drink one of more sports drinks daily (19% vs. 9%), as were more athletic/active children than those weren’t very athletic/active (18% vs. 10%).

“ Like many sugar-sweetened beverages, the excessive consumption of sports drinks is associated with weight gain, dental erosion, obesity, poor nutrition, and diabetes,” Ms. Cordery and her associates wrote. “The America Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Nutrition and Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness stated that the level of physical activity of the average child does not require the electrolyte replenishment offered by sports drinks.” Rehydration with water should be encouraged for most sports-related activities.

SOURCE: Cordery K et al. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2784.

FROM PEDIATRICS

VIDEO: First year after bariatric surgery critical for HbA1c improvement

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

REPORTING FROM AACE 18

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Change in weight within the first year was significantly correlated with lower HbA1c levels at 5 years (P = .0003).

Study details: Ancillary study of 96 patients who underwent either bariatric surgery or sleeve gastrectomy and participated in the STAMPEDE study.

Disclosures: Presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

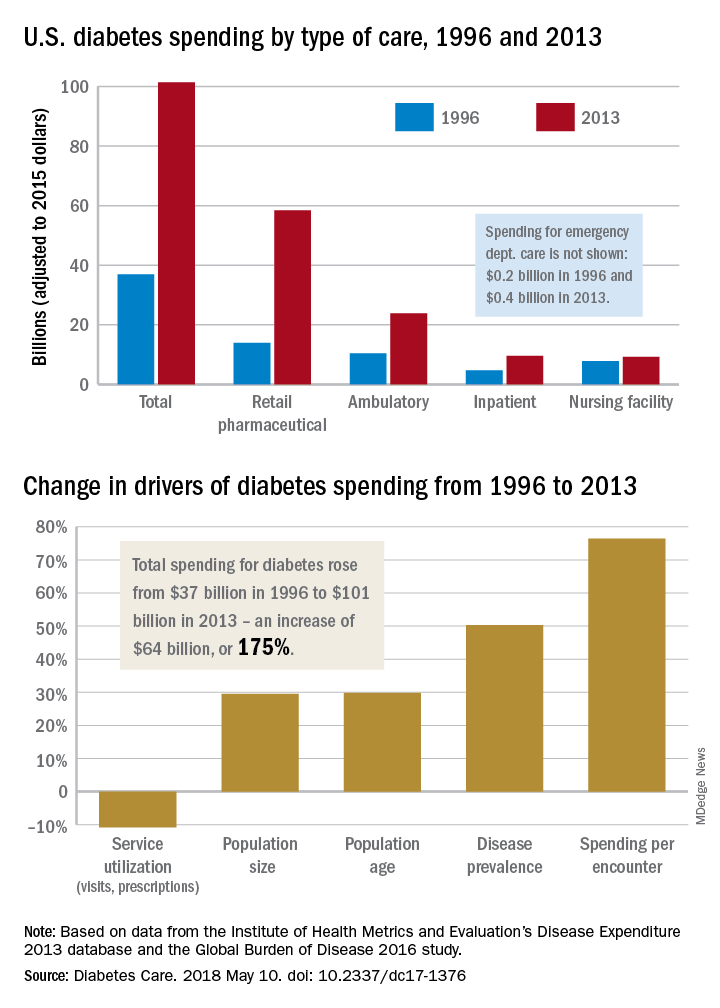

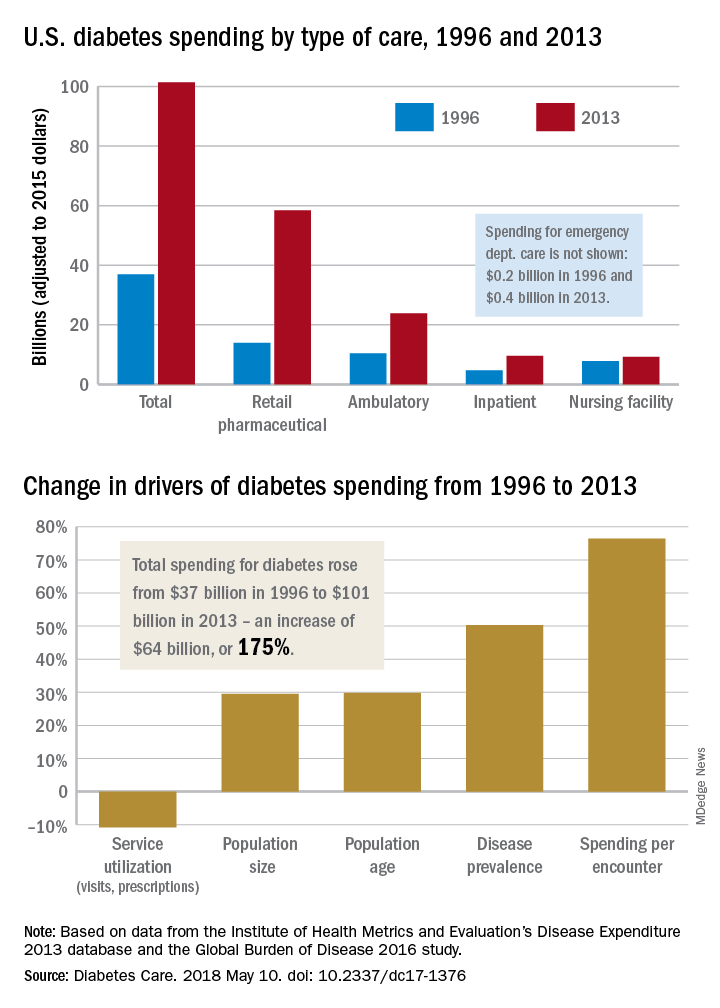

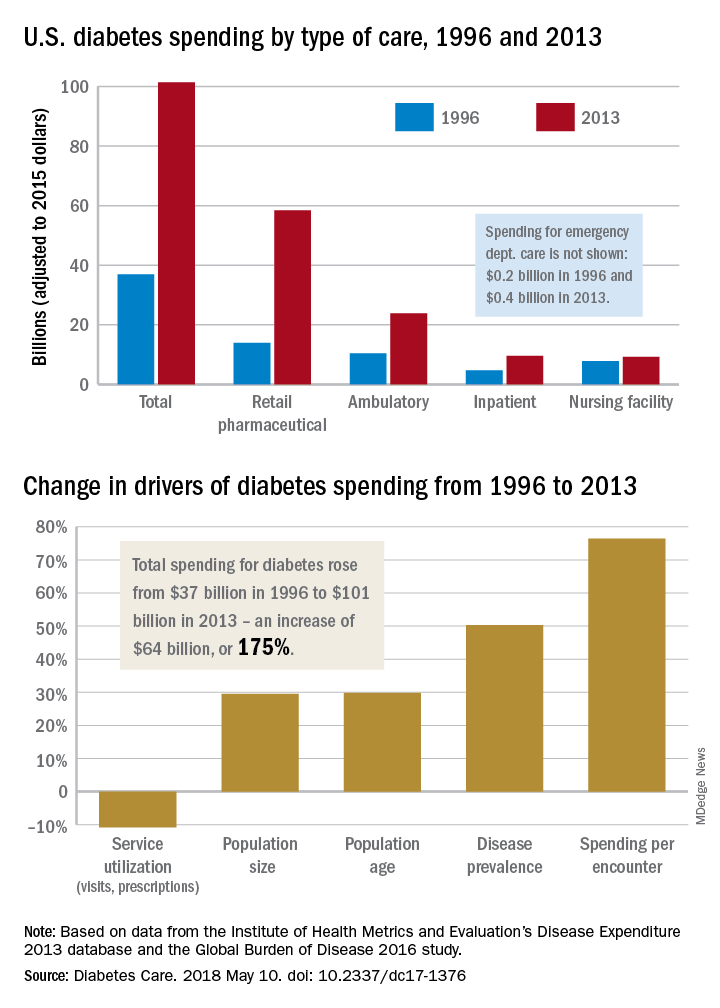

Diabetes spending topped $101 billion in 2013

according to investigators from the University of Washington, Seattle.

The largest share of personal health spending on diabetes in 2013 went for prescribed retail pharmaceuticals, which tallied over $58 billion. That was followed by ambulatory care at $24 billion, inpatient care at just under $10 billion, nursing home care at $9 billion, and emergency department care at $0.4 billion, Ellen Squires and her associates said in Diabetes Care.

“The rate of increase in pharmaceutical spending was especially drastic from 2008 to 2013, and research suggests that these upward trends have continued in more recent years,” Ms. Squires and her associates wrote.

The analysis used data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Disease Expenditure 2013 database and the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study. The current study was funded by the Peterson Center on Healthcare and the National Institute on Aging. One investigator receives research support from Medtronic Diabetes and is a consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, Bigfoot Biomedical, Adocia, and Roche. No other relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Squires E et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1376.

according to investigators from the University of Washington, Seattle.

The largest share of personal health spending on diabetes in 2013 went for prescribed retail pharmaceuticals, which tallied over $58 billion. That was followed by ambulatory care at $24 billion, inpatient care at just under $10 billion, nursing home care at $9 billion, and emergency department care at $0.4 billion, Ellen Squires and her associates said in Diabetes Care.

“The rate of increase in pharmaceutical spending was especially drastic from 2008 to 2013, and research suggests that these upward trends have continued in more recent years,” Ms. Squires and her associates wrote.

The analysis used data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Disease Expenditure 2013 database and the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study. The current study was funded by the Peterson Center on Healthcare and the National Institute on Aging. One investigator receives research support from Medtronic Diabetes and is a consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, Bigfoot Biomedical, Adocia, and Roche. No other relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Squires E et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1376.

according to investigators from the University of Washington, Seattle.

The largest share of personal health spending on diabetes in 2013 went for prescribed retail pharmaceuticals, which tallied over $58 billion. That was followed by ambulatory care at $24 billion, inpatient care at just under $10 billion, nursing home care at $9 billion, and emergency department care at $0.4 billion, Ellen Squires and her associates said in Diabetes Care.

“The rate of increase in pharmaceutical spending was especially drastic from 2008 to 2013, and research suggests that these upward trends have continued in more recent years,” Ms. Squires and her associates wrote.

The analysis used data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Disease Expenditure 2013 database and the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study. The current study was funded by the Peterson Center on Healthcare and the National Institute on Aging. One investigator receives research support from Medtronic Diabetes and is a consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, Bigfoot Biomedical, Adocia, and Roche. No other relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Squires E et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1376.

FROM DIABETES CARE

New BP guidelines synergize with transformed primary care

In mid-November, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and nine other collaborating societies released a new and long-anticipated guideline for diagnosing and managing hypertension. The top-line, seismic change that the new guidelines called for – treating many patients with hypertension to a blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg – rubbed the primary care community the wrong way, as described in Part 1 of this feature.

But the novel steps the guideline calls for, from including more careful and methodical measurement of BP, both in and out of the office, to increased reliance on lifestyle interventions, running a formal calculation to identify patients who warrant drug treatment, to a team approach to management, seem to dovetail nicely with the broader goals of primary care.

Part 2 of this feature explores how the approach to diagnosis and management of hypertension spelled out in the ACC/AHA guidelines fits into the protocol-driven, data-monitored, team-delivered primary care model that has come to dominate U.S. primary care in the decade following passage of the Affordable Care Act.

The importance of performance metrics

Regardless of what individual primary care physicians (PCPs) and other physicians and clinicians decide about the appropriate BP treatment target for hypertensive patients, their decisions these days are often strongly influenced by the standards set for population levels of BP control by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. In a trend traced by experts to the Affordable Care Act of 2009, many payers now emphasize value-based reimbursements and incentives based on health care organizations meeting performance-metric goals. One of the most common goals measured today in primary care is the percentage of patients with hypertension treated to a particular BP target that today is most commonly set as less than 140/90 mm Hg.

The “vast majority” of PCPs now work in practices that are subject to performance targets including levels of BP control, said Romsai T. Boonyasai, MD, an internist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore who specializes in quality improvement research in hypertension and other chronic diseases and also works as a PCP.

Adoption of BP control to less than 130/80 mm Hg by groups such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) “would add more pressure to comply, especially in an environment where there already is division of opinion between the ACC/AHA and American Association of Family Physicians,” agreed John P.A. Ioannidis, MD, professor of medicine and a preventive medicine specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“The AHA is looking for endorsement from the metric groups,” noted Brent M. Egan, MD, vice president for research at the Care Coordination Institute in Greenville, S.C., and a consultant to the AHA.

But a new performance metric that reflects the ACC/AHA BP target won’t appear immediately. Step one is crafting performance measures based on the ACC/AHA guideline to submit to the NQF and similar groups, a process that will soon start, said Donald E. Casey Jr., MD, a member of the guideline-writing panel and chief clinical affairs officer at Medecision in Wayne, Pa.. He will chair a committee that will review existing hypertension management performance measures and as needed also write new measures based on the guideline, a process he expects to have completed by the end of 2018. After that comes field testing the measures, and if they prove effective and workable, the next step is to submit them to the performance metric groups for review and potential adoption, steps that may take another year. In short, performance metrics for hypertension management that call for a large segment of U.S. patients to be treated to a BP below 130/80 mm Hg likely won’t be in place until the end of 2019 or sometime in 2020 at the earliest, and of course only if the metric-setting groups decide to adopt the new measures as part of their standards.

“It takes a while for guidelines to go from publication to practice. Once [the new guideline] is systematized into performance measures it will help” adoption of what the new guideline recommends, Dr. Casey said in an interview.

Target:BP

Performance metrics are not the only path that could take U.S. medicine toward lower BP targets. Another active player is the Target:BP program, a voluntary quality-improvement program for increased U.S. hypertension awareness and better management launched in late 2015 as a collaboration between the AHA and the American Medical Association.

Given that both the new guideline and Target:BP were developed through partnerships involving the AHA, “it’s logical to connect [the guideline] to Target:BP, said Dr. Egan, an AHA spokesman for Target:BP and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Target:BP’s participants are health care organizations, including health systems, medical groups, community health centers, and physician practices. The program has two primary threads.

First, it functions as a recognition program that cites participating organizations if they achieve a prespecified level of BP control.

In 2017, the program released its initial list of successful participants, organizations that maintained at least 70% of their patients diagnosed with hypertension at a BP of less than 140/90 mm Hg. According to data reported by Willie E. Lawrence Jr., MD, during the AHA scientific sessions in November in Anaheim, Calif., 191 participating programs reached this level and won a “gold” designation from the program for their level of BP control during 2016, out of 310 participating organizations that submitted 2016 data to the program.

Dr. Lawrence also reported that nearly 1,200 total health care organizations were participating in Target:BP as of his presentation, and that the 310 programs that reported 2016 data cared for roughly 12 million people, numbers that extrapolate to more than 45 million Americans cared for in all 1,200 organizations now participating in Target:BP. Among all 310 organizations reporting 2016 data, the average level of hypertension control (patients with BPs maintained at less than 140/90 mm Hg) was 66%, said Dr. Lawrence, chief of cardiology at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, Mo. The cited “gold” programs averaged 76% of their hypertensive patients treated to less than 140/90 mm Hg.

The second thread of Target:BP’s program is to supply participating organizations with training and practice tools aimed at improving hypertension diagnosis and management. The core element of the tools the program currently promotes is the MAP checklists, which stands for Measure accurately, Act rapidly, and Partner with patients, families, and communities (J Clin Hypertens. 2017 Jul;19[7]:684-94).

Target:BP’s focus on a recognition program for organizational success in BP management is very reminiscent of the Get With the Guidelines programs that the AHA previously launched for the management of various cardiovascular diseases such as ischemic stroke. Get With the Guidelines–Stroke, begun in the early 2000s, helped achieve recent success in improving the rates at which U.S. stroke patients receive timely intervention with tissue plasminogen activator, demonstrating the power a recognition program can have for improving patient care.

Target:BP moved quickly to embrace the new ACC/AHA guideline BP targets, posting a treatment target of less than 130/80 mm Hg on its website by December 2017, scant weeks after the guideline’s release in mid-November. But for the time being, Target:BP will continue to use the NQF BP quality metric as the basis for its recognition program, according to an AMA spokesperson for the program. “While the AHA and AMA will keep our joint recognition program in accordance with the NQF measure, we will simultaneously build resources, including an updated treatment algorithm, that align with the new blood pressure guideline,” according to an AMA statement.

Part of the thinking about the timing for revising the BP recognition goal in Target:BP is that it would be too confusing and challenging for participating organizations to attend to two different treatment goals at once, one for Target:BP recognition and a different one for NQF compliance, Dr. Egan explained.

Development of the MAP checklists and several other tools promoted by Target:BP came into existence through a research program sponsored by the AMA in collaboration with researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine (led by Dr. Boonyasai), and with Dr. Egan and the Care Coordination Institute. Some of these tools also received endorsement in the ACC/AHA guideline, such as the call for more accurate BP measurement. This link means that the experiences physicians have had implementing the Target:BP program provides a degree of foreshadowing for what U.S. physicians might face if they attempt to follow what the ACC/AHA guideline calls for.

Dr. Amofah and his colleagues at Community Health of South Florida, which serves about 76,000 patients with some 90 practitioners, started implementing Target:BP in the Spring of 2016. “Step one was adopting our own, customized algorithm that our entire staff could accept. Many of our clinicians practiced differently, so developing an algorithm yielded a lot of results. We gave clinicians a flow sheet for a hypertension visit,” Dr. Amofah said in an interview.

“We also pushed a program to measure BP accurately. Target:BP provided the training. Patient self-measurement of blood pressure is another key part of Target:BP. We pushed patient self-measurement, accurate measurement, and nurse-run blood pressure clinics. All these made a big difference in our success. Having a structured approach to blood pressure measurement was a major change for us.” Other “major changes” were quickly responding to uncontrolled BP, and empowering patients, he said. All of these also appear as practice recommendations in the new guideline.

When Community Health began participating in Target:BP, it had a 59% hypertension control rate (less than 140/90 mm Hg). By September 2017, roughly 18 months after starting with Target:BP, this had risen to 65%: a significant improvement, but still short of the program’s goal of 70%. Community Health had hoped to reach 70% by the end of 2017 – though as of January 2018 it remained unclear whether this had been achieved – and 80% control by the end of 2018. Reaching these goals is not completely unrealistic, but it’s challenging, Dr. Amofah said, because many of the patients at Community Health of South Florida are underserved, have poor access to medicine, have other survival priorities in their life, and have comorbidities that require attention and complicate their lives.

Dr. Amofah also serves as medical director for Health Choice Network, which includes 44 health organizations in 21 states with about 1 million patients. Of these 44 organizations, 16 have decided to participate in Target:BP, he said. The nonparticipating organizations decided to not be part of a structured program such as Target:BP and many also lacked the infrastructure that implementing Target:BP requires. But he has still tried to sell his colleagues at the nonparticipating organizations on the Target:BP approach, even if they don’t formally participate.

“Not having the support that Target:BP provides can prevent an organization from achieving its best potential,” he said. With Target:BP you get support and reinforcement. “It makes a difference; it creates a focus” Dr. Amofah said.

“Target:BP provides a lot of important guidance and tools that can help providers implement necessary changes” to aid BP control, said Jordana B. Cohen, MD, a nephrologist and hypertension researcher at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Her practice does not participate in Target:BP, but she said that she is planning to look into joining.

Systematizing blood pressure management

“Hypertension is a microcosm of the changes that are already happening in U.S. medicine. A lot of what is now going on [in U.S. medicine] is reflected in the guideline,” said Dr. Casey. “Population medicine is now a big deal.”

Several experts trace the start of systematized U.S. primary care medicine to the advent of patient-centered medical homes, which date to 2007 (JAMA. 2009 May 20;301[19]:2038-40) and rapidly expanded with the quality demands of the Affordable Care Act (Health Aff [Millwood]. 2014 Oct;33[10]:1823-31).

These days, the systematization of U.S. primary care transcends the patient-centered medical home model and appears in several forms. Some of the unifying themes are health care organizations that monitor care through quality metrics, apply quality improvement methods, and provide integrated care through multidisciplinary teams of PCPs, various physician specialists, and an array of nonphysician clinicians, The new ACC/AHA guideline, with its call for new methods of BP measurement, home measurement, lifestyle interventions, team-based care, and use of telemedicine when needed both fits into the patient-centered medical home model and provides an added impetus for primary care medicine to move further down this road.

“The patient-centered medical home has been focused on managing diabetes, so I believe that a patient-centered medical home could be easily designed to deliver better hypertension care,” Dr. Casey noted.

When Paul K. Whelton, MD, chair of the ACC/AHA guideline panel, introduced the guideline during the AHA scientific sessions in November, he cited Kaiser Permanente Northern California and the VA Health System as examples of health care organizations that have already achieved high levels of BP control (at the less than 140/90 mm Hg level) in hypertensive patients. Clinicians at Kaiser Permanente Northern California reported that by 2013 they had reached 90% control in their hypertensive patients (J Clin Hypertens. 2016 Apr;18[4]:260-1).

“Primary care systems like Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger have had the most success in controlling hypertension due to their underlying infrastructures and multidisciplinary, team-based approach to blood pressure measurement and management,” noted Dr. Cohen of the University of Pennsylvania. “I am not certain that these [ACC/AHA] guidelines are enough to drive PCPs into different health systems from where they are now established to achieve these measures. Such a shift in practice would potentially leave certain high-risk populations with a greater dearth of care providers that already exists. Ideally, there needs to be more support from Medicare and Medicaid and for those who care for uninsured patients to aid them in implementing these changes broadly into practice.”

But other experts envision the guidelines either promoting further tweaks to existing systems, or providing a further push on PCP practices into more organized systems that can marshal greater resources.

“At the most recent meeting of the clinical practice committee of the Johns Hopkins Community Physicians [which includes about 200 PCPs], I presented the new guideline, and I expected some pushback. I was shocked” by the uniform acceptance the guideline received, said Dr. Boonyasai. “The consensus of our physicians was that the only way to do this is to keep building out our team-based care models, because we can’t do it all ourselves.

“The physicians were brainstorming ways to do it. The guidelines are a discussion point around this general trend toward team-based care that has been going on for a while. We’re trying to figure out how to make it work, at Hopkins and at primary care practices everywhere. The principles of team care also work for diabetes, chronic kidney disease, etc. What we struggle to figure out is how to engage patients so that they take an active role. We can prescribe medications, but if patients don’t take them their blood pressure won’t change. They also need to eat a DASH diet and lose weight. But we need to do more than just tell patients to lose weight. We need to help them do it and we’re looking for ways to help them do this, and that means involving our medical systems with education, follow-up, and patient involvement,” Dr. Boonyasai explained.

“The question is, how does a small practice do team care with their staffing? Where do you get the staff and how do you train them? The guideline spurs us to think more creatively about how we can take better care of more patients,” he said.

“A transition is occurring in U.S. medicine,” noted Dr. Egan. “What we are generally seeing is integration of small practices into larger groups. Larger groups have quality improvement specialists who help redesign the practice to have more efficient delivery of integrated care. Recognition that our health care system was not optimal for a lot of people in terms of results led us to a different model in which the health care system pays attention to a lot of social determinant of health. Not every practice has all the people to deliver this care, but collectively a system does,” noted Dr. Egan.

“Health care systems are reimbursed for quality; that provides some of the money to ensure that extra resources exist” to improve the quality and breadth of care, he said. Introduction of new technologies means “it does not require face-to-face visits to assist in lifestyle changes. The transition in health care is making it easier to do this. Succeeding in managing patients with multiple chronic diseases requires better integration of support services. Part of the barrier to success in implementing evidence-based guidelines is they involve too much work for one person to do. Even practices in remote locations are combining into groups so that their ability to get these resources through scaling is improving.”

Dr. Egan described his own experience consulting with variously sized local practices. “I’ve worked with practices in South Carolina for 18 years, and I’ve seen the majority now become part of health care systems. When a small practice is in a rural area, it shares electronic health records with a larger group, and they get access to a network of specialists and a broader range of resources. That’s the advantage to larger networks. They get access to treatment for medical and behavioral problems in pretty close to real time. The technology is spreading rapidly and is being used. I’ve seen groups with 20 practices that have the resources to hire three PharmDs, who then rotate to meet with patients [from all the practices] to do drug reconciliation and education. An individual practice couldn’t afford something like this. This is happening to treat things like depression and opioid addiction.”

“Hypertension management is no longer a patient going to see a doctor for 15 minutes, getting their blood pressure checked, and then leaving with a prescription,” said Dr. Casey. “We are not doing a good enough job measuring, diagnosing, and treating high blood pressure. We have to come up with better ways to do it. We think that the guideline provides the pathway forward for this.”

Just after the ACC/AHA guidelines had their introduction in November, Target:BP in collaboration with TEDMED organized a panel discussion of the new guideline that included Thomas H. Lee, MD, chief medical officer of Press Ganey in Boston and a practicing internal medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

During the webcast discussion, Dr. Lee delivered this message to U.S. PCPs and other physicians and health care providers about the future of U.S. hypertension management:

“Physicians and other providers will need to adapt, even those in systems. If we don’t adapt, someone else will fill the space. Patients will find someone else who can help them.

“If providers really are about the health of their patients, then they have a responsibility to try to do better. We need to measure our outcomes and put it out there.” If a health care provider responds, ‘I can’t do it in my current practice model,’ then they should think about how their model must change.”

Dr. Egan has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Medtronic, and Valencia, has received honoraria from Merck Serono and Emcore, received royalties from UpToDate, and received research support from Medtronic and Quintiles. Dr. Lawrence has an ownership interest in Heka Health. Dr. Casey, Dr. Cohen, Dr. Ioannidis, Dr. Boonyasai, and Dr. Amofah had no disclosures.

In mid-November, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and nine other collaborating societies released a new and long-anticipated guideline for diagnosing and managing hypertension. The top-line, seismic change that the new guidelines called for – treating many patients with hypertension to a blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg – rubbed the primary care community the wrong way, as described in Part 1 of this feature.

But the novel steps the guideline calls for, from including more careful and methodical measurement of BP, both in and out of the office, to increased reliance on lifestyle interventions, running a formal calculation to identify patients who warrant drug treatment, to a team approach to management, seem to dovetail nicely with the broader goals of primary care.

Part 2 of this feature explores how the approach to diagnosis and management of hypertension spelled out in the ACC/AHA guidelines fits into the protocol-driven, data-monitored, team-delivered primary care model that has come to dominate U.S. primary care in the decade following passage of the Affordable Care Act.

The importance of performance metrics

Regardless of what individual primary care physicians (PCPs) and other physicians and clinicians decide about the appropriate BP treatment target for hypertensive patients, their decisions these days are often strongly influenced by the standards set for population levels of BP control by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. In a trend traced by experts to the Affordable Care Act of 2009, many payers now emphasize value-based reimbursements and incentives based on health care organizations meeting performance-metric goals. One of the most common goals measured today in primary care is the percentage of patients with hypertension treated to a particular BP target that today is most commonly set as less than 140/90 mm Hg.

The “vast majority” of PCPs now work in practices that are subject to performance targets including levels of BP control, said Romsai T. Boonyasai, MD, an internist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore who specializes in quality improvement research in hypertension and other chronic diseases and also works as a PCP.

Adoption of BP control to less than 130/80 mm Hg by groups such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) “would add more pressure to comply, especially in an environment where there already is division of opinion between the ACC/AHA and American Association of Family Physicians,” agreed John P.A. Ioannidis, MD, professor of medicine and a preventive medicine specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“The AHA is looking for endorsement from the metric groups,” noted Brent M. Egan, MD, vice president for research at the Care Coordination Institute in Greenville, S.C., and a consultant to the AHA.

But a new performance metric that reflects the ACC/AHA BP target won’t appear immediately. Step one is crafting performance measures based on the ACC/AHA guideline to submit to the NQF and similar groups, a process that will soon start, said Donald E. Casey Jr., MD, a member of the guideline-writing panel and chief clinical affairs officer at Medecision in Wayne, Pa.. He will chair a committee that will review existing hypertension management performance measures and as needed also write new measures based on the guideline, a process he expects to have completed by the end of 2018. After that comes field testing the measures, and if they prove effective and workable, the next step is to submit them to the performance metric groups for review and potential adoption, steps that may take another year. In short, performance metrics for hypertension management that call for a large segment of U.S. patients to be treated to a BP below 130/80 mm Hg likely won’t be in place until the end of 2019 or sometime in 2020 at the earliest, and of course only if the metric-setting groups decide to adopt the new measures as part of their standards.

“It takes a while for guidelines to go from publication to practice. Once [the new guideline] is systematized into performance measures it will help” adoption of what the new guideline recommends, Dr. Casey said in an interview.

Target:BP

Performance metrics are not the only path that could take U.S. medicine toward lower BP targets. Another active player is the Target:BP program, a voluntary quality-improvement program for increased U.S. hypertension awareness and better management launched in late 2015 as a collaboration between the AHA and the American Medical Association.

Given that both the new guideline and Target:BP were developed through partnerships involving the AHA, “it’s logical to connect [the guideline] to Target:BP, said Dr. Egan, an AHA spokesman for Target:BP and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Target:BP’s participants are health care organizations, including health systems, medical groups, community health centers, and physician practices. The program has two primary threads.

First, it functions as a recognition program that cites participating organizations if they achieve a prespecified level of BP control.

In 2017, the program released its initial list of successful participants, organizations that maintained at least 70% of their patients diagnosed with hypertension at a BP of less than 140/90 mm Hg. According to data reported by Willie E. Lawrence Jr., MD, during the AHA scientific sessions in November in Anaheim, Calif., 191 participating programs reached this level and won a “gold” designation from the program for their level of BP control during 2016, out of 310 participating organizations that submitted 2016 data to the program.

Dr. Lawrence also reported that nearly 1,200 total health care organizations were participating in Target:BP as of his presentation, and that the 310 programs that reported 2016 data cared for roughly 12 million people, numbers that extrapolate to more than 45 million Americans cared for in all 1,200 organizations now participating in Target:BP. Among all 310 organizations reporting 2016 data, the average level of hypertension control (patients with BPs maintained at less than 140/90 mm Hg) was 66%, said Dr. Lawrence, chief of cardiology at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, Mo. The cited “gold” programs averaged 76% of their hypertensive patients treated to less than 140/90 mm Hg.

The second thread of Target:BP’s program is to supply participating organizations with training and practice tools aimed at improving hypertension diagnosis and management. The core element of the tools the program currently promotes is the MAP checklists, which stands for Measure accurately, Act rapidly, and Partner with patients, families, and communities (J Clin Hypertens. 2017 Jul;19[7]:684-94).

Target:BP’s focus on a recognition program for organizational success in BP management is very reminiscent of the Get With the Guidelines programs that the AHA previously launched for the management of various cardiovascular diseases such as ischemic stroke. Get With the Guidelines–Stroke, begun in the early 2000s, helped achieve recent success in improving the rates at which U.S. stroke patients receive timely intervention with tissue plasminogen activator, demonstrating the power a recognition program can have for improving patient care.

Target:BP moved quickly to embrace the new ACC/AHA guideline BP targets, posting a treatment target of less than 130/80 mm Hg on its website by December 2017, scant weeks after the guideline’s release in mid-November. But for the time being, Target:BP will continue to use the NQF BP quality metric as the basis for its recognition program, according to an AMA spokesperson for the program. “While the AHA and AMA will keep our joint recognition program in accordance with the NQF measure, we will simultaneously build resources, including an updated treatment algorithm, that align with the new blood pressure guideline,” according to an AMA statement.

Part of the thinking about the timing for revising the BP recognition goal in Target:BP is that it would be too confusing and challenging for participating organizations to attend to two different treatment goals at once, one for Target:BP recognition and a different one for NQF compliance, Dr. Egan explained.

Development of the MAP checklists and several other tools promoted by Target:BP came into existence through a research program sponsored by the AMA in collaboration with researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine (led by Dr. Boonyasai), and with Dr. Egan and the Care Coordination Institute. Some of these tools also received endorsement in the ACC/AHA guideline, such as the call for more accurate BP measurement. This link means that the experiences physicians have had implementing the Target:BP program provides a degree of foreshadowing for what U.S. physicians might face if they attempt to follow what the ACC/AHA guideline calls for.

Dr. Amofah and his colleagues at Community Health of South Florida, which serves about 76,000 patients with some 90 practitioners, started implementing Target:BP in the Spring of 2016. “Step one was adopting our own, customized algorithm that our entire staff could accept. Many of our clinicians practiced differently, so developing an algorithm yielded a lot of results. We gave clinicians a flow sheet for a hypertension visit,” Dr. Amofah said in an interview.

“We also pushed a program to measure BP accurately. Target:BP provided the training. Patient self-measurement of blood pressure is another key part of Target:BP. We pushed patient self-measurement, accurate measurement, and nurse-run blood pressure clinics. All these made a big difference in our success. Having a structured approach to blood pressure measurement was a major change for us.” Other “major changes” were quickly responding to uncontrolled BP, and empowering patients, he said. All of these also appear as practice recommendations in the new guideline.

When Community Health began participating in Target:BP, it had a 59% hypertension control rate (less than 140/90 mm Hg). By September 2017, roughly 18 months after starting with Target:BP, this had risen to 65%: a significant improvement, but still short of the program’s goal of 70%. Community Health had hoped to reach 70% by the end of 2017 – though as of January 2018 it remained unclear whether this had been achieved – and 80% control by the end of 2018. Reaching these goals is not completely unrealistic, but it’s challenging, Dr. Amofah said, because many of the patients at Community Health of South Florida are underserved, have poor access to medicine, have other survival priorities in their life, and have comorbidities that require attention and complicate their lives.

Dr. Amofah also serves as medical director for Health Choice Network, which includes 44 health organizations in 21 states with about 1 million patients. Of these 44 organizations, 16 have decided to participate in Target:BP, he said. The nonparticipating organizations decided to not be part of a structured program such as Target:BP and many also lacked the infrastructure that implementing Target:BP requires. But he has still tried to sell his colleagues at the nonparticipating organizations on the Target:BP approach, even if they don’t formally participate.

“Not having the support that Target:BP provides can prevent an organization from achieving its best potential,” he said. With Target:BP you get support and reinforcement. “It makes a difference; it creates a focus” Dr. Amofah said.

“Target:BP provides a lot of important guidance and tools that can help providers implement necessary changes” to aid BP control, said Jordana B. Cohen, MD, a nephrologist and hypertension researcher at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Her practice does not participate in Target:BP, but she said that she is planning to look into joining.

Systematizing blood pressure management

“Hypertension is a microcosm of the changes that are already happening in U.S. medicine. A lot of what is now going on [in U.S. medicine] is reflected in the guideline,” said Dr. Casey. “Population medicine is now a big deal.”

Several experts trace the start of systematized U.S. primary care medicine to the advent of patient-centered medical homes, which date to 2007 (JAMA. 2009 May 20;301[19]:2038-40) and rapidly expanded with the quality demands of the Affordable Care Act (Health Aff [Millwood]. 2014 Oct;33[10]:1823-31).

These days, the systematization of U.S. primary care transcends the patient-centered medical home model and appears in several forms. Some of the unifying themes are health care organizations that monitor care through quality metrics, apply quality improvement methods, and provide integrated care through multidisciplinary teams of PCPs, various physician specialists, and an array of nonphysician clinicians, The new ACC/AHA guideline, with its call for new methods of BP measurement, home measurement, lifestyle interventions, team-based care, and use of telemedicine when needed both fits into the patient-centered medical home model and provides an added impetus for primary care medicine to move further down this road.

“The patient-centered medical home has been focused on managing diabetes, so I believe that a patient-centered medical home could be easily designed to deliver better hypertension care,” Dr. Casey noted.

When Paul K. Whelton, MD, chair of the ACC/AHA guideline panel, introduced the guideline during the AHA scientific sessions in November, he cited Kaiser Permanente Northern California and the VA Health System as examples of health care organizations that have already achieved high levels of BP control (at the less than 140/90 mm Hg level) in hypertensive patients. Clinicians at Kaiser Permanente Northern California reported that by 2013 they had reached 90% control in their hypertensive patients (J Clin Hypertens. 2016 Apr;18[4]:260-1).

“Primary care systems like Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger have had the most success in controlling hypertension due to their underlying infrastructures and multidisciplinary, team-based approach to blood pressure measurement and management,” noted Dr. Cohen of the University of Pennsylvania. “I am not certain that these [ACC/AHA] guidelines are enough to drive PCPs into different health systems from where they are now established to achieve these measures. Such a shift in practice would potentially leave certain high-risk populations with a greater dearth of care providers that already exists. Ideally, there needs to be more support from Medicare and Medicaid and for those who care for uninsured patients to aid them in implementing these changes broadly into practice.”

But other experts envision the guidelines either promoting further tweaks to existing systems, or providing a further push on PCP practices into more organized systems that can marshal greater resources.

“At the most recent meeting of the clinical practice committee of the Johns Hopkins Community Physicians [which includes about 200 PCPs], I presented the new guideline, and I expected some pushback. I was shocked” by the uniform acceptance the guideline received, said Dr. Boonyasai. “The consensus of our physicians was that the only way to do this is to keep building out our team-based care models, because we can’t do it all ourselves.

“The physicians were brainstorming ways to do it. The guidelines are a discussion point around this general trend toward team-based care that has been going on for a while. We’re trying to figure out how to make it work, at Hopkins and at primary care practices everywhere. The principles of team care also work for diabetes, chronic kidney disease, etc. What we struggle to figure out is how to engage patients so that they take an active role. We can prescribe medications, but if patients don’t take them their blood pressure won’t change. They also need to eat a DASH diet and lose weight. But we need to do more than just tell patients to lose weight. We need to help them do it and we’re looking for ways to help them do this, and that means involving our medical systems with education, follow-up, and patient involvement,” Dr. Boonyasai explained.

“The question is, how does a small practice do team care with their staffing? Where do you get the staff and how do you train them? The guideline spurs us to think more creatively about how we can take better care of more patients,” he said.

“A transition is occurring in U.S. medicine,” noted Dr. Egan. “What we are generally seeing is integration of small practices into larger groups. Larger groups have quality improvement specialists who help redesign the practice to have more efficient delivery of integrated care. Recognition that our health care system was not optimal for a lot of people in terms of results led us to a different model in which the health care system pays attention to a lot of social determinant of health. Not every practice has all the people to deliver this care, but collectively a system does,” noted Dr. Egan.

“Health care systems are reimbursed for quality; that provides some of the money to ensure that extra resources exist” to improve the quality and breadth of care, he said. Introduction of new technologies means “it does not require face-to-face visits to assist in lifestyle changes. The transition in health care is making it easier to do this. Succeeding in managing patients with multiple chronic diseases requires better integration of support services. Part of the barrier to success in implementing evidence-based guidelines is they involve too much work for one person to do. Even practices in remote locations are combining into groups so that their ability to get these resources through scaling is improving.”

Dr. Egan described his own experience consulting with variously sized local practices. “I’ve worked with practices in South Carolina for 18 years, and I’ve seen the majority now become part of health care systems. When a small practice is in a rural area, it shares electronic health records with a larger group, and they get access to a network of specialists and a broader range of resources. That’s the advantage to larger networks. They get access to treatment for medical and behavioral problems in pretty close to real time. The technology is spreading rapidly and is being used. I’ve seen groups with 20 practices that have the resources to hire three PharmDs, who then rotate to meet with patients [from all the practices] to do drug reconciliation and education. An individual practice couldn’t afford something like this. This is happening to treat things like depression and opioid addiction.”