User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Building owners, managers must do more to prevent Legionnaires’ disease

Building owners, managers, and administrators of hospitals and other health care facilities around the country are being urged to shore up their water system management facilities to prevent further outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease, which is the focus of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Vital Signs report.

“Almost all Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks are preventable with improvements in water system management,” explained CDC Director Tom Frieden, adding that “At the end of the day, building owners and managers need to take steps to reduce the risk of Legionnaires’ disease [and] work together to reduce this risk and limit the number of people exposed, infected, and hospitalized or, potentially, fatally infected.”

For the report, the CDC investigated 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States from 2000 through 2014, which involved a total of 415 cases and 65 fatalities. In each outbreak analysis, the location, source of exposure, and problems with environmental controls of Legionella – the bacterium that causes the disease – were evaluated.

Hotels and resorts accounted for 44% of all outbreaks over the 15-year period, followed by long-term care facilities (19%) and hospitals (15%). However, outbreaks at the latter two location types accounted for 85% of all deaths, while outbreaks at hotels and resorts accounted for only 6%. Potable water was the most common direct cause of Legionella infections, followed by water from cooling towers, hot tubs, industrial equipment, and decorative fountains.

Additionally, 23 of the investigations yielded enough information to determine the exact cause of the outbreak, all of which were caused by at least one of 4 issues. The first was process failures, such as not having a proper water system management program in place to handle Legionella; this was found in two-thirds of the outbreaks. The second major cause was human error, such as not replacing filters or tubing as recommended by manufacturers, which was a cause in half of the outbreaks. The third was equipment breakdown, which was found in one-third of the outbreaks. Finally, reasons external to the buildings themselves – such as water main breaks or disruptions caused by nearby construction – factored into one-third of the outbreaks.

“Large, recent outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in New York City and Flint, Michigan, have brought attention to the disease and highlight the need for us to understand why these outbreaks happen and how best to prevent them, [which is] why this Vital Signs is targeted to a specific audience that we in public health don’t talk [to] often enough: building owners and managers,” Dr. Frieden said. “It’s not a traditional public health audience, [but] they are the key to environmental controls in buildings that we live in, get our health care in, and work in everyday.”

To that end, Dr. Frieden announced the release of a new CDC toolkit entitled “Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth & Spread in Buildings: A Practical Guide to Implementing Industry Standards,” which building owners, managers, and administrators can turn to for guidance on how to implement effective water system management protocols in their buildings.

Legionnaires’ disease is a serious lung infection caused by inhalation of the bacteria Legionella, which can be found in water and inhaled as airborne mist. Elderly individuals, as well as those with suppressed immune systems because of underlying illnesses, are at a heightened risk for Legionnaires’ disease, which would explain the higher death rates observed at hospitals and long-term care facilities. Dr. Frieden stated that outbreaks and cases of Legionnaires’ disease are on the rise nationally, with about 5,000 infections and 20 outbreaks occurring annually; roughly 10% of infections result in death.

The uptick in recent cases is likely because of “the aging of the population, the increase in chronic illness, [an] increase in immunosuppression through use of medication to treat a variety of conditions [and] an aging plumbing infrastructure and that makes maintenance all the more challenging,” according to Dr. Frieden. “It is also possible that increased use of diagnostic tests and more reliable reporting are contributing to some of the rising rates.”

Building owners, managers, and administrators of hospitals and other health care facilities around the country are being urged to shore up their water system management facilities to prevent further outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease, which is the focus of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Vital Signs report.

“Almost all Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks are preventable with improvements in water system management,” explained CDC Director Tom Frieden, adding that “At the end of the day, building owners and managers need to take steps to reduce the risk of Legionnaires’ disease [and] work together to reduce this risk and limit the number of people exposed, infected, and hospitalized or, potentially, fatally infected.”

For the report, the CDC investigated 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States from 2000 through 2014, which involved a total of 415 cases and 65 fatalities. In each outbreak analysis, the location, source of exposure, and problems with environmental controls of Legionella – the bacterium that causes the disease – were evaluated.

Hotels and resorts accounted for 44% of all outbreaks over the 15-year period, followed by long-term care facilities (19%) and hospitals (15%). However, outbreaks at the latter two location types accounted for 85% of all deaths, while outbreaks at hotels and resorts accounted for only 6%. Potable water was the most common direct cause of Legionella infections, followed by water from cooling towers, hot tubs, industrial equipment, and decorative fountains.

Additionally, 23 of the investigations yielded enough information to determine the exact cause of the outbreak, all of which were caused by at least one of 4 issues. The first was process failures, such as not having a proper water system management program in place to handle Legionella; this was found in two-thirds of the outbreaks. The second major cause was human error, such as not replacing filters or tubing as recommended by manufacturers, which was a cause in half of the outbreaks. The third was equipment breakdown, which was found in one-third of the outbreaks. Finally, reasons external to the buildings themselves – such as water main breaks or disruptions caused by nearby construction – factored into one-third of the outbreaks.

“Large, recent outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in New York City and Flint, Michigan, have brought attention to the disease and highlight the need for us to understand why these outbreaks happen and how best to prevent them, [which is] why this Vital Signs is targeted to a specific audience that we in public health don’t talk [to] often enough: building owners and managers,” Dr. Frieden said. “It’s not a traditional public health audience, [but] they are the key to environmental controls in buildings that we live in, get our health care in, and work in everyday.”

To that end, Dr. Frieden announced the release of a new CDC toolkit entitled “Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth & Spread in Buildings: A Practical Guide to Implementing Industry Standards,” which building owners, managers, and administrators can turn to for guidance on how to implement effective water system management protocols in their buildings.

Legionnaires’ disease is a serious lung infection caused by inhalation of the bacteria Legionella, which can be found in water and inhaled as airborne mist. Elderly individuals, as well as those with suppressed immune systems because of underlying illnesses, are at a heightened risk for Legionnaires’ disease, which would explain the higher death rates observed at hospitals and long-term care facilities. Dr. Frieden stated that outbreaks and cases of Legionnaires’ disease are on the rise nationally, with about 5,000 infections and 20 outbreaks occurring annually; roughly 10% of infections result in death.

The uptick in recent cases is likely because of “the aging of the population, the increase in chronic illness, [an] increase in immunosuppression through use of medication to treat a variety of conditions [and] an aging plumbing infrastructure and that makes maintenance all the more challenging,” according to Dr. Frieden. “It is also possible that increased use of diagnostic tests and more reliable reporting are contributing to some of the rising rates.”

Building owners, managers, and administrators of hospitals and other health care facilities around the country are being urged to shore up their water system management facilities to prevent further outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease, which is the focus of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Vital Signs report.

“Almost all Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks are preventable with improvements in water system management,” explained CDC Director Tom Frieden, adding that “At the end of the day, building owners and managers need to take steps to reduce the risk of Legionnaires’ disease [and] work together to reduce this risk and limit the number of people exposed, infected, and hospitalized or, potentially, fatally infected.”

For the report, the CDC investigated 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States from 2000 through 2014, which involved a total of 415 cases and 65 fatalities. In each outbreak analysis, the location, source of exposure, and problems with environmental controls of Legionella – the bacterium that causes the disease – were evaluated.

Hotels and resorts accounted for 44% of all outbreaks over the 15-year period, followed by long-term care facilities (19%) and hospitals (15%). However, outbreaks at the latter two location types accounted for 85% of all deaths, while outbreaks at hotels and resorts accounted for only 6%. Potable water was the most common direct cause of Legionella infections, followed by water from cooling towers, hot tubs, industrial equipment, and decorative fountains.

Additionally, 23 of the investigations yielded enough information to determine the exact cause of the outbreak, all of which were caused by at least one of 4 issues. The first was process failures, such as not having a proper water system management program in place to handle Legionella; this was found in two-thirds of the outbreaks. The second major cause was human error, such as not replacing filters or tubing as recommended by manufacturers, which was a cause in half of the outbreaks. The third was equipment breakdown, which was found in one-third of the outbreaks. Finally, reasons external to the buildings themselves – such as water main breaks or disruptions caused by nearby construction – factored into one-third of the outbreaks.

“Large, recent outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in New York City and Flint, Michigan, have brought attention to the disease and highlight the need for us to understand why these outbreaks happen and how best to prevent them, [which is] why this Vital Signs is targeted to a specific audience that we in public health don’t talk [to] often enough: building owners and managers,” Dr. Frieden said. “It’s not a traditional public health audience, [but] they are the key to environmental controls in buildings that we live in, get our health care in, and work in everyday.”

To that end, Dr. Frieden announced the release of a new CDC toolkit entitled “Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth & Spread in Buildings: A Practical Guide to Implementing Industry Standards,” which building owners, managers, and administrators can turn to for guidance on how to implement effective water system management protocols in their buildings.

Legionnaires’ disease is a serious lung infection caused by inhalation of the bacteria Legionella, which can be found in water and inhaled as airborne mist. Elderly individuals, as well as those with suppressed immune systems because of underlying illnesses, are at a heightened risk for Legionnaires’ disease, which would explain the higher death rates observed at hospitals and long-term care facilities. Dr. Frieden stated that outbreaks and cases of Legionnaires’ disease are on the rise nationally, with about 5,000 infections and 20 outbreaks occurring annually; roughly 10% of infections result in death.

The uptick in recent cases is likely because of “the aging of the population, the increase in chronic illness, [an] increase in immunosuppression through use of medication to treat a variety of conditions [and] an aging plumbing infrastructure and that makes maintenance all the more challenging,” according to Dr. Frieden. “It is also possible that increased use of diagnostic tests and more reliable reporting are contributing to some of the rising rates.”

FROM CDC VITAL SIGNS

Low hematocrit in elderly portends increased bleeding post PCI

PARIS – A low hematocrit in an elderly patient who’s going to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention signals a markedly increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days of the procedure, according to Dr. David Marti.

“Analysis of hematocrit in elderly patients can guide important procedural characteristics, such as access site and antithrombotic regimen,” he said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

For example, studies have established that transradial artery access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) results in significantly less bleeding than the transfemoral route, said Dr. Marti, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

He presented a prospective study of 212 consecutive patients aged 75 or older who underwent PCI at a single university hospital. Their mean age was 81.4 years, and slightly over half of them presented with an acute coronary syndrome.

All patients received dual-antiplatelet therapy in accord with current guidelines. Stent type and procedural anticoagulant regimen were left to the discretion of the cardiologist; 80% of the subjects received bivalirudin-based anticoagulation.

The primary study outcome was the 30-day incidence of major bleeding, as defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 event. The overall rate in this elderly PCI population was 5.5%. However, the rate varied markedly by baseline hematocrit tertile, in accord with the investigators’ study hypothesis.

Major bleeding occurred in 2.9% of patients with an Hct greater than 42% and 3.1% in those with an Hct of 38%-52%, and jumped to 10.6% in the one-third of subjects whose baseline Hct was below 38%, Dr. Marti reported.

Thus, a preprocedural Hct below 38% was associated with a 4.1-fold increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days following PCI. An Hct in this range was a stronger predictor of BARC type 3-5 bleeding risk than were other factors better known as being important, including advanced age, greater body weight, female sex, or an elevated serum creatinine indicative of chronic kidney disease. Indeed, an Hct below 38% was the only statistically significant predictor of major bleeding in this elderly population.

The likely explanation for the observed results is that a low Hct level in elderly patients usually reflects subclinical blood loss that can be worsened by antithrombotic therapies, the cardiologist explained.

The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted without commercial support.

PARIS – A low hematocrit in an elderly patient who’s going to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention signals a markedly increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days of the procedure, according to Dr. David Marti.

“Analysis of hematocrit in elderly patients can guide important procedural characteristics, such as access site and antithrombotic regimen,” he said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

For example, studies have established that transradial artery access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) results in significantly less bleeding than the transfemoral route, said Dr. Marti, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

He presented a prospective study of 212 consecutive patients aged 75 or older who underwent PCI at a single university hospital. Their mean age was 81.4 years, and slightly over half of them presented with an acute coronary syndrome.

All patients received dual-antiplatelet therapy in accord with current guidelines. Stent type and procedural anticoagulant regimen were left to the discretion of the cardiologist; 80% of the subjects received bivalirudin-based anticoagulation.

The primary study outcome was the 30-day incidence of major bleeding, as defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 event. The overall rate in this elderly PCI population was 5.5%. However, the rate varied markedly by baseline hematocrit tertile, in accord with the investigators’ study hypothesis.

Major bleeding occurred in 2.9% of patients with an Hct greater than 42% and 3.1% in those with an Hct of 38%-52%, and jumped to 10.6% in the one-third of subjects whose baseline Hct was below 38%, Dr. Marti reported.

Thus, a preprocedural Hct below 38% was associated with a 4.1-fold increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days following PCI. An Hct in this range was a stronger predictor of BARC type 3-5 bleeding risk than were other factors better known as being important, including advanced age, greater body weight, female sex, or an elevated serum creatinine indicative of chronic kidney disease. Indeed, an Hct below 38% was the only statistically significant predictor of major bleeding in this elderly population.

The likely explanation for the observed results is that a low Hct level in elderly patients usually reflects subclinical blood loss that can be worsened by antithrombotic therapies, the cardiologist explained.

The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted without commercial support.

PARIS – A low hematocrit in an elderly patient who’s going to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention signals a markedly increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days of the procedure, according to Dr. David Marti.

“Analysis of hematocrit in elderly patients can guide important procedural characteristics, such as access site and antithrombotic regimen,” he said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

For example, studies have established that transradial artery access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) results in significantly less bleeding than the transfemoral route, said Dr. Marti, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

He presented a prospective study of 212 consecutive patients aged 75 or older who underwent PCI at a single university hospital. Their mean age was 81.4 years, and slightly over half of them presented with an acute coronary syndrome.

All patients received dual-antiplatelet therapy in accord with current guidelines. Stent type and procedural anticoagulant regimen were left to the discretion of the cardiologist; 80% of the subjects received bivalirudin-based anticoagulation.

The primary study outcome was the 30-day incidence of major bleeding, as defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 event. The overall rate in this elderly PCI population was 5.5%. However, the rate varied markedly by baseline hematocrit tertile, in accord with the investigators’ study hypothesis.

Major bleeding occurred in 2.9% of patients with an Hct greater than 42% and 3.1% in those with an Hct of 38%-52%, and jumped to 10.6% in the one-third of subjects whose baseline Hct was below 38%, Dr. Marti reported.

Thus, a preprocedural Hct below 38% was associated with a 4.1-fold increased risk of major bleeding within 30 days following PCI. An Hct in this range was a stronger predictor of BARC type 3-5 bleeding risk than were other factors better known as being important, including advanced age, greater body weight, female sex, or an elevated serum creatinine indicative of chronic kidney disease. Indeed, an Hct below 38% was the only statistically significant predictor of major bleeding in this elderly population.

The likely explanation for the observed results is that a low Hct level in elderly patients usually reflects subclinical blood loss that can be worsened by antithrombotic therapies, the cardiologist explained.

The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted without commercial support.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: Elderly patients scheduled for PCI have a fourfold greater risk of major bleeding within 30 days if their Hct is less than 38%.

Major finding: The 30-day incidence of BARC types 3-5 major bleeding was 10.9% in elderly patients with a pre-PCI Hct below 38%, compared with 2.9% in those in the top Hct tertile.

Data source: A prospective study of 212 consecutive patients aged 75 or older who underwent PCI at a single university hospital.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted without commercial support.

New heart failure interventions face outcomes test

A history of trials where a well-reasoned heart failure intervention did not have the expected results is now coloring the way some clinicians view potential new treatments.

A couple of examples of this cautious, skeptical mindset cropped up during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in Florence, Italy, in May.

I previously reported on one of the major talks at the sessions, results from a pivotal trial of a phrenic nerve stimulation device in 151 patients with some type of cardiovascular disease (more than half had heart failure) and central sleep apnea. These patients generally had significant improvement in their apnea-hypopnea index while on active treatment with the phrenic nerve stimulator, designed to produce rhythmic contractions of the diaphragm to create negative chest pressure and enhance breathing in a way that mimics natural respiration and avoids the apparent danger from a positive-pressure intervention in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The positive-pressure danger in such patients occurred unexpectedly and dramatically in the form of significantly increased mortality among HFrEF patients with central sleep apnea enrolled in the SERVE-HF trial. Based on that chilling experience, “our understanding of central sleep apnea is imperfect,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, lead investigator of SERVE-HF, who rehashed his experience with that study during the recent meeting. “A really important message was that just because patients say they feel better [with the adaptive servo-ventilation tested in SERVE-HF], that doesn’t necessarily translate into benefit,” Dr. Cowie noted.

Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, a leading U.S. heart failure expert, had a similar reaction when I spoke with her during the meeting.

“A lot of things made a lot of sense, including treating central sleep apnea in a patient with HFrEF with positive air pressure that made them feel better,” she said, also invoking the specter of SERVE-HF. “We have to now demand that sleep trials show benefit in clinical outcomes,” such as reduced mortality or a cut in heart failure hospitalizations, and certainly no increase in mortality. Until that’s shown for phrenic nerve stimulation she’ll stay a skeptic, she told me.

Another intervention recently available for U.S. heart failure patients that seems on track to confront this “show-me-the-outcomes” attitude involves new drugs that cut serum potassium levels by binding to potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. This class includes patiromer (Veltassa), approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2015. Another potassium binder, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9), seems on track to soon receive FDA approval.

Several speakers at the meeting spoke of the potential to use these drugs to control the hyperkalemia that often complicates treatment of heart failure patients with an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, especially heart failure patients with concomitant renal disease. Study results showed treatment with patiromer or ZS-9 reversed hyperkalemia, thereby allowing patients to remain on these drugs that are known to significantly cut rates of mortality and heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients.

“Right now, a lot of patients don’t get these lifesaving drugs” because of hyperkalemia, noted Dr. Bertram Pitt, a University of Michigan cardiologist who has been involved in several patiromer trials (and is a consultant to Relypsa, the company that markets patiromer).

The problem is that no studies of patiromer or ZS-9 treatment have so far shown that these drugs lead to reduced mortality or heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients. All that’s been shown is that patiromer and ZS-9 are effective at lowering potassium levels in patients with hyperkalemia out of the danger zone, levels above 5 mEq/L.

“I want to see outcome trials,” said Dr. Jessup.

Dr. Pitt agreed that outcomes data would be ideal, but also noted that currently no studies aimed at collecting these data are underway.

Without these data, clinicians need to decide whether they believe proven potassium lowering alone is a good enough reason to prescribe patiromer or ZS-9, or whether they need to see proof that these drugs give patients clinically meaningful benefits.

If they demand outcomes evidence they may need to wait quite a while.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A history of trials where a well-reasoned heart failure intervention did not have the expected results is now coloring the way some clinicians view potential new treatments.

A couple of examples of this cautious, skeptical mindset cropped up during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in Florence, Italy, in May.

I previously reported on one of the major talks at the sessions, results from a pivotal trial of a phrenic nerve stimulation device in 151 patients with some type of cardiovascular disease (more than half had heart failure) and central sleep apnea. These patients generally had significant improvement in their apnea-hypopnea index while on active treatment with the phrenic nerve stimulator, designed to produce rhythmic contractions of the diaphragm to create negative chest pressure and enhance breathing in a way that mimics natural respiration and avoids the apparent danger from a positive-pressure intervention in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The positive-pressure danger in such patients occurred unexpectedly and dramatically in the form of significantly increased mortality among HFrEF patients with central sleep apnea enrolled in the SERVE-HF trial. Based on that chilling experience, “our understanding of central sleep apnea is imperfect,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, lead investigator of SERVE-HF, who rehashed his experience with that study during the recent meeting. “A really important message was that just because patients say they feel better [with the adaptive servo-ventilation tested in SERVE-HF], that doesn’t necessarily translate into benefit,” Dr. Cowie noted.

Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, a leading U.S. heart failure expert, had a similar reaction when I spoke with her during the meeting.

“A lot of things made a lot of sense, including treating central sleep apnea in a patient with HFrEF with positive air pressure that made them feel better,” she said, also invoking the specter of SERVE-HF. “We have to now demand that sleep trials show benefit in clinical outcomes,” such as reduced mortality or a cut in heart failure hospitalizations, and certainly no increase in mortality. Until that’s shown for phrenic nerve stimulation she’ll stay a skeptic, she told me.

Another intervention recently available for U.S. heart failure patients that seems on track to confront this “show-me-the-outcomes” attitude involves new drugs that cut serum potassium levels by binding to potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. This class includes patiromer (Veltassa), approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2015. Another potassium binder, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9), seems on track to soon receive FDA approval.

Several speakers at the meeting spoke of the potential to use these drugs to control the hyperkalemia that often complicates treatment of heart failure patients with an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, especially heart failure patients with concomitant renal disease. Study results showed treatment with patiromer or ZS-9 reversed hyperkalemia, thereby allowing patients to remain on these drugs that are known to significantly cut rates of mortality and heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients.

“Right now, a lot of patients don’t get these lifesaving drugs” because of hyperkalemia, noted Dr. Bertram Pitt, a University of Michigan cardiologist who has been involved in several patiromer trials (and is a consultant to Relypsa, the company that markets patiromer).

The problem is that no studies of patiromer or ZS-9 treatment have so far shown that these drugs lead to reduced mortality or heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients. All that’s been shown is that patiromer and ZS-9 are effective at lowering potassium levels in patients with hyperkalemia out of the danger zone, levels above 5 mEq/L.

“I want to see outcome trials,” said Dr. Jessup.

Dr. Pitt agreed that outcomes data would be ideal, but also noted that currently no studies aimed at collecting these data are underway.

Without these data, clinicians need to decide whether they believe proven potassium lowering alone is a good enough reason to prescribe patiromer or ZS-9, or whether they need to see proof that these drugs give patients clinically meaningful benefits.

If they demand outcomes evidence they may need to wait quite a while.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A history of trials where a well-reasoned heart failure intervention did not have the expected results is now coloring the way some clinicians view potential new treatments.

A couple of examples of this cautious, skeptical mindset cropped up during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in Florence, Italy, in May.

I previously reported on one of the major talks at the sessions, results from a pivotal trial of a phrenic nerve stimulation device in 151 patients with some type of cardiovascular disease (more than half had heart failure) and central sleep apnea. These patients generally had significant improvement in their apnea-hypopnea index while on active treatment with the phrenic nerve stimulator, designed to produce rhythmic contractions of the diaphragm to create negative chest pressure and enhance breathing in a way that mimics natural respiration and avoids the apparent danger from a positive-pressure intervention in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The positive-pressure danger in such patients occurred unexpectedly and dramatically in the form of significantly increased mortality among HFrEF patients with central sleep apnea enrolled in the SERVE-HF trial. Based on that chilling experience, “our understanding of central sleep apnea is imperfect,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, lead investigator of SERVE-HF, who rehashed his experience with that study during the recent meeting. “A really important message was that just because patients say they feel better [with the adaptive servo-ventilation tested in SERVE-HF], that doesn’t necessarily translate into benefit,” Dr. Cowie noted.

Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, a leading U.S. heart failure expert, had a similar reaction when I spoke with her during the meeting.

“A lot of things made a lot of sense, including treating central sleep apnea in a patient with HFrEF with positive air pressure that made them feel better,” she said, also invoking the specter of SERVE-HF. “We have to now demand that sleep trials show benefit in clinical outcomes,” such as reduced mortality or a cut in heart failure hospitalizations, and certainly no increase in mortality. Until that’s shown for phrenic nerve stimulation she’ll stay a skeptic, she told me.

Another intervention recently available for U.S. heart failure patients that seems on track to confront this “show-me-the-outcomes” attitude involves new drugs that cut serum potassium levels by binding to potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. This class includes patiromer (Veltassa), approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2015. Another potassium binder, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9), seems on track to soon receive FDA approval.

Several speakers at the meeting spoke of the potential to use these drugs to control the hyperkalemia that often complicates treatment of heart failure patients with an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, especially heart failure patients with concomitant renal disease. Study results showed treatment with patiromer or ZS-9 reversed hyperkalemia, thereby allowing patients to remain on these drugs that are known to significantly cut rates of mortality and heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients.

“Right now, a lot of patients don’t get these lifesaving drugs” because of hyperkalemia, noted Dr. Bertram Pitt, a University of Michigan cardiologist who has been involved in several patiromer trials (and is a consultant to Relypsa, the company that markets patiromer).

The problem is that no studies of patiromer or ZS-9 treatment have so far shown that these drugs lead to reduced mortality or heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure patients. All that’s been shown is that patiromer and ZS-9 are effective at lowering potassium levels in patients with hyperkalemia out of the danger zone, levels above 5 mEq/L.

“I want to see outcome trials,” said Dr. Jessup.

Dr. Pitt agreed that outcomes data would be ideal, but also noted that currently no studies aimed at collecting these data are underway.

Without these data, clinicians need to decide whether they believe proven potassium lowering alone is a good enough reason to prescribe patiromer or ZS-9, or whether they need to see proof that these drugs give patients clinically meaningful benefits.

If they demand outcomes evidence they may need to wait quite a while.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Infliximab fails as salvage treatment for severe ulcerative colitis

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Infliximab was not effective as inpatient salvage therapy for severe ulcerative colitis.

Major finding: Of patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

Data source: A study of 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center.

Disclosures: Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

Study eyes impact of surgical safety checklists on mortality

After implementation of surgical safety checklists in a tertiary care hospital, researchers observed a 27% reduction of risk-adjusted all-cause 90-day mortality, but adjusted all-cause 30-day mortality remained unchanged.

In addition, length of stay was reduced but 30-day readmission rate was not, according to the study published online in JAMA Surgery. Those key findings are from an effort to assess the association between the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) and rates of all-cause 90- and 30-day mortality.

Previous studies have analyzed in-hospital mortality or 30-day mortality “but not intermediate-term outcome variables,” said lead author Dr. Matthias Bock of the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Merano Hospital, Merano, Italy. “Almost one-quarter (23.6%) of the deaths within 30 days after surgery occurred after discharge, and 39.7% of patients undergoing surgery experienced only post-discharge complications. Ninety-day mortality often doubles 30-day mortality. In-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality might therefore underreport the real risk to these patients, especially after tumor surgery or among the elderly. Studies of the effect or the association of the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) on 90-day mortality are lacking.”

Dr. Bock and his associates retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of surgical procedures performed during the six months before and six months after implementation of SSCs at the 715-bed Central Hospital of Bolzano (CHB) in Italy (Jan. 1-June 30, 2010, and Jan. 1-June 30, 2013, respectively). The key outcome measures were risk-adjusted rates of 90- and 30-day mortality, readmission rate, and LOS (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5490).

The study sample consisted of 10,741 patients, including 5,444 pre-intervention and 5,297 post-intervention patients. Of these, 53% were female and their mean age was 53 years.

The researchers reported that 90-day all-cause mortality was 2.4% before SSC implementation, compared with 2.2% after implementation, for an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.73 (P = .02). However, 30-day all-cause mortality was 1.36% before SSC implementation, compared with 1.32% after implementation, for an AOR of 0.79 (P = .17), remaining essentially unchanged.

Dr. Bock and his associates also found that 30-day readmission rates were similar in the pre-implementation and post-implementation groups (14.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively: P = .90), but the adjusted length of stay favored the post-implementation group (a mean of 9.6 days, compared with a mean of 10.4 days in the in the pre-implementation group; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and the lack of a control group. “The study design highly reduces the risk for observation bias (Hawthorne effect),” they wrote. “Furthermore, we did not inform the staff about the purpose of our study. We analyzed only objective outcome data to reduce reporting bias as much as possible.”

The finding of a decline in LOS “suggests potential cost savings after the implementation of SSCs,” they concluded. “Further trials should address this hypothesis and the effect on quality of care owing to a reduction of the costs of complications or unplanned reoperations.”

The study was supported by the Public Health Care Company of South Tyrol, Italy, and by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Italy. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

We commend the authors for choosing to focus on the 90-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate, and we are reassured that they saw a statistically significant decrease. However, we should also consider why no statistically significant change in the 30-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate was observed. This finding could be attributable to inherent differences in the population studied, to the case mix, or to insufficient power to detect change related to sample size.

This article also highlights the ongoing challenges of checklist implementation and measurement of the impact of the SSC. First, whether SSC performance underwent direct observation during implementation and whether that observation compared with reported performance are unclear. Checklist performance appears to be measured primarily by checking whether a form was completed. Significant discordance between paper checklist completion and actual completion has been described. Second, 80% completion was considered the threshold for complete implementation in this study, whereas recent literature supports that full rather than partial checklist completion provides an opportunity for significant improvement of the effect of the SSC on the quality of patient care and surgical safety. With more effective implementation and full SSC use in every case, the improvement in outcomes seen could have been even. If the SSC is not used, it cannot help.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared online in JAMA Surgery (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5551). Dr. William Berry is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; Dr. Alex Haynes is with the department of surgical oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Dr. Janaka Lagoo is with the Harvard School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

We commend the authors for choosing to focus on the 90-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate, and we are reassured that they saw a statistically significant decrease. However, we should also consider why no statistically significant change in the 30-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate was observed. This finding could be attributable to inherent differences in the population studied, to the case mix, or to insufficient power to detect change related to sample size.

This article also highlights the ongoing challenges of checklist implementation and measurement of the impact of the SSC. First, whether SSC performance underwent direct observation during implementation and whether that observation compared with reported performance are unclear. Checklist performance appears to be measured primarily by checking whether a form was completed. Significant discordance between paper checklist completion and actual completion has been described. Second, 80% completion was considered the threshold for complete implementation in this study, whereas recent literature supports that full rather than partial checklist completion provides an opportunity for significant improvement of the effect of the SSC on the quality of patient care and surgical safety. With more effective implementation and full SSC use in every case, the improvement in outcomes seen could have been even. If the SSC is not used, it cannot help.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared online in JAMA Surgery (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5551). Dr. William Berry is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; Dr. Alex Haynes is with the department of surgical oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Dr. Janaka Lagoo is with the Harvard School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

We commend the authors for choosing to focus on the 90-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate, and we are reassured that they saw a statistically significant decrease. However, we should also consider why no statistically significant change in the 30-day postoperative all-cause mortality rate was observed. This finding could be attributable to inherent differences in the population studied, to the case mix, or to insufficient power to detect change related to sample size.

This article also highlights the ongoing challenges of checklist implementation and measurement of the impact of the SSC. First, whether SSC performance underwent direct observation during implementation and whether that observation compared with reported performance are unclear. Checklist performance appears to be measured primarily by checking whether a form was completed. Significant discordance between paper checklist completion and actual completion has been described. Second, 80% completion was considered the threshold for complete implementation in this study, whereas recent literature supports that full rather than partial checklist completion provides an opportunity for significant improvement of the effect of the SSC on the quality of patient care and surgical safety. With more effective implementation and full SSC use in every case, the improvement in outcomes seen could have been even. If the SSC is not used, it cannot help.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared online in JAMA Surgery (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5551). Dr. William Berry is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; Dr. Alex Haynes is with the department of surgical oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Dr. Janaka Lagoo is with the Harvard School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

After implementation of surgical safety checklists in a tertiary care hospital, researchers observed a 27% reduction of risk-adjusted all-cause 90-day mortality, but adjusted all-cause 30-day mortality remained unchanged.

In addition, length of stay was reduced but 30-day readmission rate was not, according to the study published online in JAMA Surgery. Those key findings are from an effort to assess the association between the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) and rates of all-cause 90- and 30-day mortality.

Previous studies have analyzed in-hospital mortality or 30-day mortality “but not intermediate-term outcome variables,” said lead author Dr. Matthias Bock of the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Merano Hospital, Merano, Italy. “Almost one-quarter (23.6%) of the deaths within 30 days after surgery occurred after discharge, and 39.7% of patients undergoing surgery experienced only post-discharge complications. Ninety-day mortality often doubles 30-day mortality. In-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality might therefore underreport the real risk to these patients, especially after tumor surgery or among the elderly. Studies of the effect or the association of the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) on 90-day mortality are lacking.”

Dr. Bock and his associates retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of surgical procedures performed during the six months before and six months after implementation of SSCs at the 715-bed Central Hospital of Bolzano (CHB) in Italy (Jan. 1-June 30, 2010, and Jan. 1-June 30, 2013, respectively). The key outcome measures were risk-adjusted rates of 90- and 30-day mortality, readmission rate, and LOS (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5490).

The study sample consisted of 10,741 patients, including 5,444 pre-intervention and 5,297 post-intervention patients. Of these, 53% were female and their mean age was 53 years.

The researchers reported that 90-day all-cause mortality was 2.4% before SSC implementation, compared with 2.2% after implementation, for an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.73 (P = .02). However, 30-day all-cause mortality was 1.36% before SSC implementation, compared with 1.32% after implementation, for an AOR of 0.79 (P = .17), remaining essentially unchanged.

Dr. Bock and his associates also found that 30-day readmission rates were similar in the pre-implementation and post-implementation groups (14.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively: P = .90), but the adjusted length of stay favored the post-implementation group (a mean of 9.6 days, compared with a mean of 10.4 days in the in the pre-implementation group; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and the lack of a control group. “The study design highly reduces the risk for observation bias (Hawthorne effect),” they wrote. “Furthermore, we did not inform the staff about the purpose of our study. We analyzed only objective outcome data to reduce reporting bias as much as possible.”

The finding of a decline in LOS “suggests potential cost savings after the implementation of SSCs,” they concluded. “Further trials should address this hypothesis and the effect on quality of care owing to a reduction of the costs of complications or unplanned reoperations.”

The study was supported by the Public Health Care Company of South Tyrol, Italy, and by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Italy. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

After implementation of surgical safety checklists in a tertiary care hospital, researchers observed a 27% reduction of risk-adjusted all-cause 90-day mortality, but adjusted all-cause 30-day mortality remained unchanged.

In addition, length of stay was reduced but 30-day readmission rate was not, according to the study published online in JAMA Surgery. Those key findings are from an effort to assess the association between the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) and rates of all-cause 90- and 30-day mortality.

Previous studies have analyzed in-hospital mortality or 30-day mortality “but not intermediate-term outcome variables,” said lead author Dr. Matthias Bock of the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Merano Hospital, Merano, Italy. “Almost one-quarter (23.6%) of the deaths within 30 days after surgery occurred after discharge, and 39.7% of patients undergoing surgery experienced only post-discharge complications. Ninety-day mortality often doubles 30-day mortality. In-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality might therefore underreport the real risk to these patients, especially after tumor surgery or among the elderly. Studies of the effect or the association of the implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) on 90-day mortality are lacking.”

Dr. Bock and his associates retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of surgical procedures performed during the six months before and six months after implementation of SSCs at the 715-bed Central Hospital of Bolzano (CHB) in Italy (Jan. 1-June 30, 2010, and Jan. 1-June 30, 2013, respectively). The key outcome measures were risk-adjusted rates of 90- and 30-day mortality, readmission rate, and LOS (JAMA Surg. 2016 Feb 3. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5490).

The study sample consisted of 10,741 patients, including 5,444 pre-intervention and 5,297 post-intervention patients. Of these, 53% were female and their mean age was 53 years.

The researchers reported that 90-day all-cause mortality was 2.4% before SSC implementation, compared with 2.2% after implementation, for an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.73 (P = .02). However, 30-day all-cause mortality was 1.36% before SSC implementation, compared with 1.32% after implementation, for an AOR of 0.79 (P = .17), remaining essentially unchanged.

Dr. Bock and his associates also found that 30-day readmission rates were similar in the pre-implementation and post-implementation groups (14.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively: P = .90), but the adjusted length of stay favored the post-implementation group (a mean of 9.6 days, compared with a mean of 10.4 days in the in the pre-implementation group; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and the lack of a control group. “The study design highly reduces the risk for observation bias (Hawthorne effect),” they wrote. “Furthermore, we did not inform the staff about the purpose of our study. We analyzed only objective outcome data to reduce reporting bias as much as possible.”

The finding of a decline in LOS “suggests potential cost savings after the implementation of SSCs,” they concluded. “Further trials should address this hypothesis and the effect on quality of care owing to a reduction of the costs of complications or unplanned reoperations.”

The study was supported by the Public Health Care Company of South Tyrol, Italy, and by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Italy. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Implementation of surgical safety checklists (SSCs) at a hospital led to reduced risk of mortality at 90 days, but not at 30 days.

Major finding: Ninety-day all-cause mortality was 2.4% before implementation of SSCs, compared with 2.2% after implementation, for an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.73 (P = .02).

Data source: A retrospective evaluation of surgical procedures performed on 10,741 patients during the 6 months before and 6 months after implementation of SSCs at the 715-bed Central Hospital of Bolzano in Italy.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Public Health Care Company of South Tyrol, Italy, and by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Italy. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

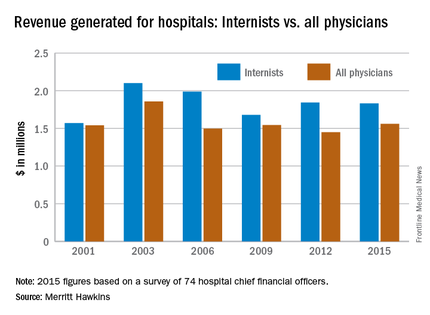

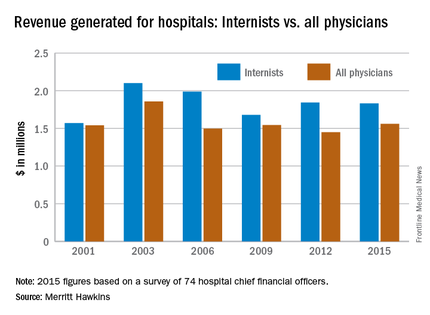

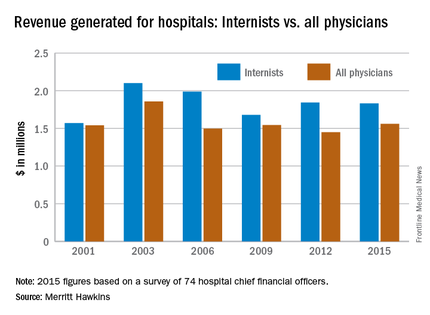

Internists’ hospital revenue steady as primary care drops

The average net revenue internists generated for hospitals held steady from 2012 to 2015, unlike that of primary care physicians in general, according to a survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

Internists generated average net revenue of almost $1.83 million for their affiliated hospitals in 2015, down by less than 1% from the $1.84 million generated in 2012, when Merritt Hawkins last conducted its Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey of hospital chief financial officers. For primary care physicians more broadly – defined as family physicians, general internal medicine physicians, and pediatricians – the 2015 figure was $1.40 million, compared with $1.56 million in 2012 – a drop of 10.5%.

“Declining revenues generated by family physicians (and flat revenues generated by general internists) may be a result of risk-bearing reimbursement models, where primary care physicians and their employers are penalized for exceeding budgets,” the report suggested. Another factor in the decline among primary care physicians may be decreased productivity among physicians employed by hospitals. A survey of over 20,000 physicians conducted in 2014 by Merritt Hawkins indicated that employed physicians saw 8.5% fewer patients per day than did independent physicians.

Average net revenue generated by physicians in all 18 specialties measured almost $1.56 million in 2015, which was up 7.7% over the $1.45 million generated in 2012. Average net revenue for specialists was up 12.8%, going from $1.42 million in 2012 to $1.61 million in 2015.

The survey (available for download here) was completed by 74 hospital chief financial officers. Despite the small number, Merritt Hawkins said that the “results are reliable and accurate, in large part because the overall number for average annual revenue generated by all physician specialties for their affiliated hospitals has remained virtually unchanged” over the course of six surveys spanning 14 years.

The average net revenue internists generated for hospitals held steady from 2012 to 2015, unlike that of primary care physicians in general, according to a survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

Internists generated average net revenue of almost $1.83 million for their affiliated hospitals in 2015, down by less than 1% from the $1.84 million generated in 2012, when Merritt Hawkins last conducted its Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey of hospital chief financial officers. For primary care physicians more broadly – defined as family physicians, general internal medicine physicians, and pediatricians – the 2015 figure was $1.40 million, compared with $1.56 million in 2012 – a drop of 10.5%.

“Declining revenues generated by family physicians (and flat revenues generated by general internists) may be a result of risk-bearing reimbursement models, where primary care physicians and their employers are penalized for exceeding budgets,” the report suggested. Another factor in the decline among primary care physicians may be decreased productivity among physicians employed by hospitals. A survey of over 20,000 physicians conducted in 2014 by Merritt Hawkins indicated that employed physicians saw 8.5% fewer patients per day than did independent physicians.

Average net revenue generated by physicians in all 18 specialties measured almost $1.56 million in 2015, which was up 7.7% over the $1.45 million generated in 2012. Average net revenue for specialists was up 12.8%, going from $1.42 million in 2012 to $1.61 million in 2015.

The survey (available for download here) was completed by 74 hospital chief financial officers. Despite the small number, Merritt Hawkins said that the “results are reliable and accurate, in large part because the overall number for average annual revenue generated by all physician specialties for their affiliated hospitals has remained virtually unchanged” over the course of six surveys spanning 14 years.

The average net revenue internists generated for hospitals held steady from 2012 to 2015, unlike that of primary care physicians in general, according to a survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

Internists generated average net revenue of almost $1.83 million for their affiliated hospitals in 2015, down by less than 1% from the $1.84 million generated in 2012, when Merritt Hawkins last conducted its Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey of hospital chief financial officers. For primary care physicians more broadly – defined as family physicians, general internal medicine physicians, and pediatricians – the 2015 figure was $1.40 million, compared with $1.56 million in 2012 – a drop of 10.5%.

“Declining revenues generated by family physicians (and flat revenues generated by general internists) may be a result of risk-bearing reimbursement models, where primary care physicians and their employers are penalized for exceeding budgets,” the report suggested. Another factor in the decline among primary care physicians may be decreased productivity among physicians employed by hospitals. A survey of over 20,000 physicians conducted in 2014 by Merritt Hawkins indicated that employed physicians saw 8.5% fewer patients per day than did independent physicians.

Average net revenue generated by physicians in all 18 specialties measured almost $1.56 million in 2015, which was up 7.7% over the $1.45 million generated in 2012. Average net revenue for specialists was up 12.8%, going from $1.42 million in 2012 to $1.61 million in 2015.

The survey (available for download here) was completed by 74 hospital chief financial officers. Despite the small number, Merritt Hawkins said that the “results are reliable and accurate, in large part because the overall number for average annual revenue generated by all physician specialties for their affiliated hospitals has remained virtually unchanged” over the course of six surveys spanning 14 years.

VIDEO: Accelerated infliximab dosing halved colectomy rate in severe ulcerative colitis

SAN DIEGO – Inpatient infliximab rescue for severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is more likely to work if patients receive a second infusion 3 days after the first, according to a review of 55 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, patients.

The traditional approach is one inpatient 5-mg/kg infusion, followed by either colectomy or subsequent outpatient infusions, depending on response. In 2013, physicians at the university began offering a second infusion at 72 hours to patients whose C-reactive protein (CRP) levels did not drop below 0.7 mg/dL after their first infusion, and they also began opting more often for 10-mg/kg dosing.

The review found that 90-day colectomy-free survival was 50% in the 16 accelerated-dosing patients, up from 10.2% in the 36 patients treated with the traditional approach (P less than .001). The finding has led to a new, more aggressive infliximab protocol for inpatient ulcerative colitis.

Among patients who did undergo colectomies, postoperative complications were similar between the two groups. But for reasons that are not clear, 30-day postoperative readmission rates were higher in accelerated patients (58% vs. 25%).

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, lead investigator Dr. Shail Govani of the University of Michigan explained the thinking behind the new approach, how CRP/albumin ratios come into play, and how to counsel patients in light of the findings.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Inpatient infliximab rescue for severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is more likely to work if patients receive a second infusion 3 days after the first, according to a review of 55 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, patients.

The traditional approach is one inpatient 5-mg/kg infusion, followed by either colectomy or subsequent outpatient infusions, depending on response. In 2013, physicians at the university began offering a second infusion at 72 hours to patients whose C-reactive protein (CRP) levels did not drop below 0.7 mg/dL after their first infusion, and they also began opting more often for 10-mg/kg dosing.

The review found that 90-day colectomy-free survival was 50% in the 16 accelerated-dosing patients, up from 10.2% in the 36 patients treated with the traditional approach (P less than .001). The finding has led to a new, more aggressive infliximab protocol for inpatient ulcerative colitis.

Among patients who did undergo colectomies, postoperative complications were similar between the two groups. But for reasons that are not clear, 30-day postoperative readmission rates were higher in accelerated patients (58% vs. 25%).

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, lead investigator Dr. Shail Govani of the University of Michigan explained the thinking behind the new approach, how CRP/albumin ratios come into play, and how to counsel patients in light of the findings.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Inpatient infliximab rescue for severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is more likely to work if patients receive a second infusion 3 days after the first, according to a review of 55 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, patients.

The traditional approach is one inpatient 5-mg/kg infusion, followed by either colectomy or subsequent outpatient infusions, depending on response. In 2013, physicians at the university began offering a second infusion at 72 hours to patients whose C-reactive protein (CRP) levels did not drop below 0.7 mg/dL after their first infusion, and they also began opting more often for 10-mg/kg dosing.

The review found that 90-day colectomy-free survival was 50% in the 16 accelerated-dosing patients, up from 10.2% in the 36 patients treated with the traditional approach (P less than .001). The finding has led to a new, more aggressive infliximab protocol for inpatient ulcerative colitis.

Among patients who did undergo colectomies, postoperative complications were similar between the two groups. But for reasons that are not clear, 30-day postoperative readmission rates were higher in accelerated patients (58% vs. 25%).

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, lead investigator Dr. Shail Govani of the University of Michigan explained the thinking behind the new approach, how CRP/albumin ratios come into play, and how to counsel patients in light of the findings.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT DDW 2016

Improvement needed for U.S. acute care hospitals implementing ASPs

There is more room for improving U.S. acute care hospitals’ antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) and implementing the seven core elements, according to findings from the 2014 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Annual Hospital Survey.

In univariate analyses, Dr. Lori A. Pollack, of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates looked at 4,184 acute care hospitals. Of those acute care hospitals, 1,642 (39%) reported implementing all seven CDC-defined core elements – leadership commitment, a single program leader responsible for outcomes, a pharmacy leader, specific interventions to improve prescribing, tracking antibiotic use and resistance, reporting data back to provider, and education – for hospital ASPs. In the hospitals with more than 200 beds, 775 (56%) were more likely to report all seven core elements, compared with 672 (39%) hospitals with 51-200 beds, and 328 (22%) of hospitals with 50 or fewer beds.

The hospitals with 50 or fewer beds were less likely to report leadership support (40%) or antibiotic stewardship education (46%), compared with facilities with greater than 50 beds (69% leadership, 69% education). Also, the major teaching hospitals were more likely to report all seven core elements (54%) than were hospitals that had only undergraduate education or no teaching affiliation (34%).

The study also conducted a final multivariate model and found that the strongest predictor for meeting all seven core elements was support from the facility administration (adjusted relative risk, 7.2; P less than .0001).

“Our findings suggest that many hospitals need to add infrastructure and measurement support to their current actions to improve antibiotic use,” the researchers concluded. “CDC is committed to on-going work with partners to help all hospitals implement effective antibiotic stewardship programs, and future years of this survey will help monitor progress toward that goal.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw323).

There is more room for improving U.S. acute care hospitals’ antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) and implementing the seven core elements, according to findings from the 2014 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Annual Hospital Survey.

In univariate analyses, Dr. Lori A. Pollack, of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates looked at 4,184 acute care hospitals. Of those acute care hospitals, 1,642 (39%) reported implementing all seven CDC-defined core elements – leadership commitment, a single program leader responsible for outcomes, a pharmacy leader, specific interventions to improve prescribing, tracking antibiotic use and resistance, reporting data back to provider, and education – for hospital ASPs. In the hospitals with more than 200 beds, 775 (56%) were more likely to report all seven core elements, compared with 672 (39%) hospitals with 51-200 beds, and 328 (22%) of hospitals with 50 or fewer beds.

The hospitals with 50 or fewer beds were less likely to report leadership support (40%) or antibiotic stewardship education (46%), compared with facilities with greater than 50 beds (69% leadership, 69% education). Also, the major teaching hospitals were more likely to report all seven core elements (54%) than were hospitals that had only undergraduate education or no teaching affiliation (34%).

The study also conducted a final multivariate model and found that the strongest predictor for meeting all seven core elements was support from the facility administration (adjusted relative risk, 7.2; P less than .0001).