User login

HCV Hub

AbbVie

acid

addicted

addiction

adolescent

adult sites

Advocacy

advocacy

agitated states

AJO, postsurgical analgesic, knee, replacement, surgery

alcohol

amphetamine

androgen

antibody

apple cider vinegar

assistance

Assistance

association

at home

attorney

audit

ayurvedic

baby

ban

baricitinib

bed bugs

best

bible

bisexual

black

bleach

blog

bulimia nervosa

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cervical cancer, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, IVIM, diffusion-weighted MRI, DWI

charlie sheen

cheap

cheapest

child

childhood

childlike

children

chronic fatigue syndrome

Cladribine Tablets

cocaine

cock

combination therapies, synergistic antitumor efficacy, pertuzumab, trastuzumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, palbociclib, letrozole, lapatinib, docetaxel, trametinib, dabrafenib, carflzomib, lenalidomide

contagious

Cortical Lesions

cream

creams

crime

criminal

cure

dangerous

dangers

dasabuvir

Dasabuvir

dead

deadly

death

dementia

dependence

dependent

depression

dermatillomania

die

diet

direct-acting antivirals

Disability

Discount

discount

dog

drink

drug abuse

drug-induced

dying

eastern medicine

eat

ect

eczema

electroconvulsive therapy

electromagnetic therapy

electrotherapy

epa

epilepsy

erectile dysfunction

explosive disorder

fake

Fake-ovir

fatal

fatalities

fatality

fibromyalgia

financial

Financial

fish oil

food

foods

foundation

free

Gabriel Pardo

gaston

general hospital

genetic

geriatric

Giancarlo Comi

gilead

Gilead

glaucoma

Glenn S. Williams

Glenn Williams

Gloria Dalla Costa

gonorrhea

Greedy

greedy

guns

hallucinations

harvoni

Harvoni

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

Hidradenitis Suppurativa,

holistic

home

home remedies

home remedy

homeopathic

homeopathy

hydrocortisone

ice

image

images

job

kid

kids

kill

killer

laser

lawsuit

lawyer

ledipasvir

Ledipasvir

lesbian

lesions

lights

liver

lupus

marijuana

melancholic

memory loss

menopausal

mental retardation

military

milk

moisturizers

monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs

MRI

MS

murder

national

natural

natural cure

natural cures

natural medications

natural medicine

natural medicines

natural remedies

natural remedy

natural treatment

natural treatments

naturally

Needy

needy

Neurology Reviews

neuropathic

nightclub massacre

nightclub shooting

nude

nudity

nutraceuticals

OASIS

oasis

off label

ombitasvir

Ombitasvir

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir

orlando shooting

overactive thyroid gland

overdose

overdosed

Paolo Preziosa

paritaprevir

Paritaprevir

pediatric

pedophile

photo

photos

picture

post partum

postnatal

pregnancy

pregnant

prenatal

prepartum

prison

program

Program

Protest

protest

psychedelics

pulse nightclub

puppy

purchase

purchasing

rape

recall

recreational drug

Rehabilitation

Retinal Measurements

retrograde ejaculation

risperdal

ritonavir

Ritonavir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

robin williams

sales

sasquatch

schizophrenia

seizure

seizures

sex

sexual

sexy

shock treatment

silver

sleep disorders

smoking

sociopath

sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir

sovaldi

ssri

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

support

Support

Support Path

teen

teenage

teenagers

Telerehabilitation

testosterone

Th17

Th17:FoxP3+Treg cell ratio

Th22

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treatment resistant

V Pak

vagina

velpatasvir

Viekira Pa

Viekira Pak

viekira pak

violence

virgin

vitamin

VPak

weight loss

withdrawal

wrinkles

xxx

young adult

young adults

zoloft

financial

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

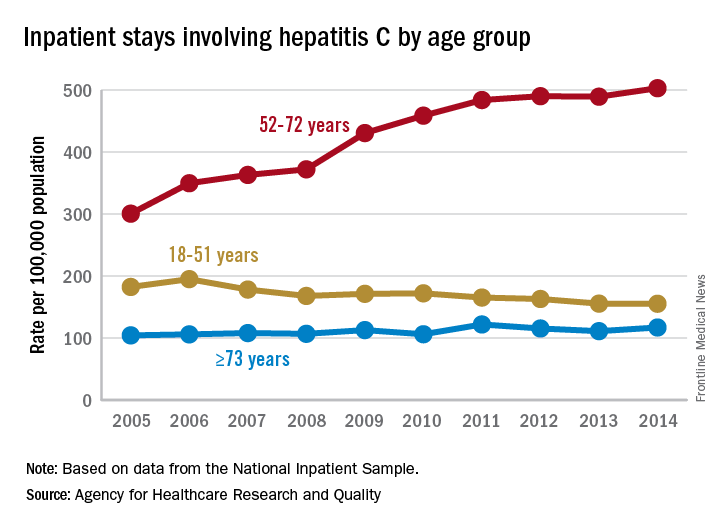

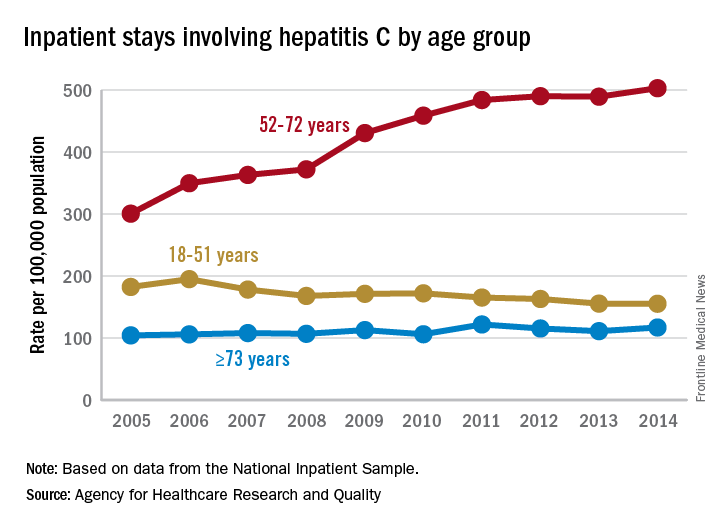

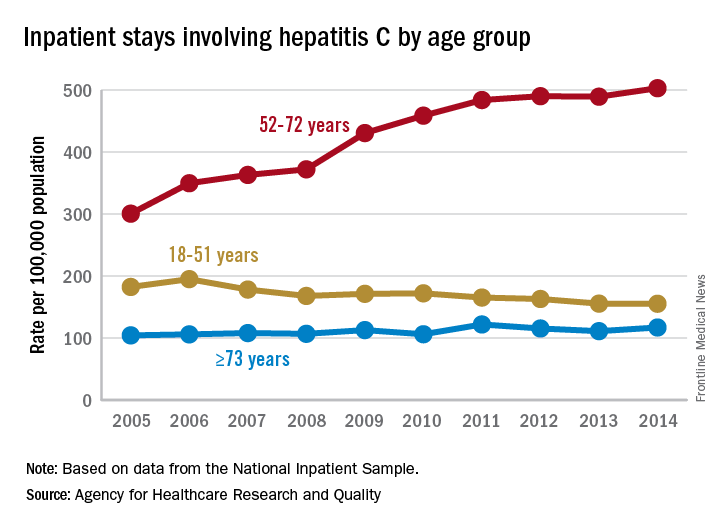

Baby boomers are the hepatitis C generation

Increases in hepatitis C–related inpatient stays for baby boomers from 2005 to 2014 far outpaced those of older adults, while younger adults saw their admissions drop over that period, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For the baby boomers (adults aged 52-72 years), the rate of inpatient stays involving hepatitis C with or without hepatitis B, HIV, or alcoholic liver disease rose from 300.7 per 100,000 population in 2005 to 503.1 per 100,000 in 2014 – an increase of over 67%. For patients aged 73 years and older, that rate went from 104.4 in 2005 to 117.1 in 2014, which translates to a 12% increase, and for patients aged 18-51 years, it dropped 15%, from 182.5 to 155.4, the AHRQ said in a statistical brief.

Along with the increased hospitalizations, “acute hepatitis C cases nearly tripled from 2010 through 2015,” the report noted, which was “likely the result of increasing injection drug use due to the growing opioid epidemic.”

Increases in hepatitis C–related inpatient stays for baby boomers from 2005 to 2014 far outpaced those of older adults, while younger adults saw their admissions drop over that period, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For the baby boomers (adults aged 52-72 years), the rate of inpatient stays involving hepatitis C with or without hepatitis B, HIV, or alcoholic liver disease rose from 300.7 per 100,000 population in 2005 to 503.1 per 100,000 in 2014 – an increase of over 67%. For patients aged 73 years and older, that rate went from 104.4 in 2005 to 117.1 in 2014, which translates to a 12% increase, and for patients aged 18-51 years, it dropped 15%, from 182.5 to 155.4, the AHRQ said in a statistical brief.

Along with the increased hospitalizations, “acute hepatitis C cases nearly tripled from 2010 through 2015,” the report noted, which was “likely the result of increasing injection drug use due to the growing opioid epidemic.”

Increases in hepatitis C–related inpatient stays for baby boomers from 2005 to 2014 far outpaced those of older adults, while younger adults saw their admissions drop over that period, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For the baby boomers (adults aged 52-72 years), the rate of inpatient stays involving hepatitis C with or without hepatitis B, HIV, or alcoholic liver disease rose from 300.7 per 100,000 population in 2005 to 503.1 per 100,000 in 2014 – an increase of over 67%. For patients aged 73 years and older, that rate went from 104.4 in 2005 to 117.1 in 2014, which translates to a 12% increase, and for patients aged 18-51 years, it dropped 15%, from 182.5 to 155.4, the AHRQ said in a statistical brief.

Along with the increased hospitalizations, “acute hepatitis C cases nearly tripled from 2010 through 2015,” the report noted, which was “likely the result of increasing injection drug use due to the growing opioid epidemic.”

Eradicating HCV significantly improved liver stiffness in meta-analysis

Eradicating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection led to significant decreases in liver stiffness in a systematic review and meta-analysis of nearly 3,000 patients.

Mean liver stiffness fell by 4.1 kPa (kilopascals) (95% confidence interval, 3.3-4.9 kPa) 12 or more months after patients achieved sustained virologic response to treatment, but did not significantly change in patients who did not achieve SVR, reported Siddharth Singh, MD, of the University of San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and his associates in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.038). The results were especially striking among patients who received direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) or who had high baseline levels of inflammation, the investigators added.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Based on these findings, about 47% of patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis at baseline will drop below 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR, they reported. “With this decline in liver stiffness, it is conceivable that risk of liver-related complications would decrease, particularly in patients without cirrhosis,” they added. “Future research is warranted on the impact of magnitude and kinetics of decline in liver stiffness on improvement in liver-related outcomes.”

Eradicating HCV infection was known to decrease liver stiffness, but the magnitude of decline was not well understood. Therefore, the reviewers searched the literature through October 2016 for studies of HCV-infected adults who underwent liver stiffness measurement by vibration-controlled transient elastography before and at least once after completing HCV treatment. All studies also included data on median liver stiffness among patients who did and did not achieve SVR. The search identified 23 observational studies and one post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, for a total of 2,934 patients, of whom 2,214 achieved SVR.

Among patients who achieved SVR, mean liver stiffness dropped by 2.4 kPa at the end of treatment (95% CI, 1.7-3.0 kPa), by 3.1 kPa 1-6 months later (95% CI, 1.6-4.7 kPa), and by 3.2 kPa 6-12 months after completing treatment (90% CI, 2.6-3.9 kPa). A year or more after finishing treatment, patients who achieved SVR had a 28% median decrease in liver stiffness (interquartile range, 22%-35%). However, liver stiffness did not significantly change among patients who did not achieve SVR, the reviewers reported.

Mean liver stiffness declined significantly more among patients who received DAAs (4.5 kPa) than among recipients of interferon-based regimens (2.6 kPa; P = .03). However, studies of DAAs included patients with greater liver stiffness at baseline, which could at least partially explain this discrepancy, the investigators said. Baseline cirrhosis also was associated with a greater decline in liver stiffness (mean, 5.1 kPa, vs. 2.8 kPa in patients without cirrhosis; P = .02), as was high baseline alanine aminotransferase level (P less than .01). Among patients whose baseline liver stiffness measurement exceeded 9.5 kPa, 47% had their liver stiffness drop to less than 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR.

Coinfection with HIV did not significantly alter the magnitude of decline in liver stiffness 6-12 months after treatment in patients who achieved SVR, the reviewers noted. “[Follow-up] assessment after SVR was relatively short; hence, long-term evolution of liver stiffness after antiviral therapy and impact of decline in liver stiffness on patient clinical outcomes could not be ascertained,” they wrote. The studies also did not consistently assess potential confounders such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, and alcohol consumption.

One reviewer disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine. None had conflicts of interest.

The current era of new-generation direct-acting antiviral agents have revolutionized the treatment landscape of chronic hepatitis C virus infection, providing short-duration, safe, and consistently effective regimens that achieve SVR or cure in nearly 100% of patients. While achieving SVR is important, even more important is the long-term impact of SVR and whether cure translates into outcomes such as improved mortality or a reduced risk of disease progression. Although improved mortality after SVR has been demonstrated, one of the main drivers of risk of disease progression is the severity of hepatic fibrosis.

Robert J. Wong, MD, MS, is with the department of medicine and is director of research and education, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Alameda Health System – Highland Hospital, Oakland, Calif. He has received a 2017-2019 Clinical Translational Research Award from AASLD, has received research funding from Gilead and AbbVie, and is on the speakers bureau of Gilead, Salix, and Bayer. He has also done consulting for and been an advisory board member for Gilead.

The current era of new-generation direct-acting antiviral agents have revolutionized the treatment landscape of chronic hepatitis C virus infection, providing short-duration, safe, and consistently effective regimens that achieve SVR or cure in nearly 100% of patients. While achieving SVR is important, even more important is the long-term impact of SVR and whether cure translates into outcomes such as improved mortality or a reduced risk of disease progression. Although improved mortality after SVR has been demonstrated, one of the main drivers of risk of disease progression is the severity of hepatic fibrosis.

Robert J. Wong, MD, MS, is with the department of medicine and is director of research and education, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Alameda Health System – Highland Hospital, Oakland, Calif. He has received a 2017-2019 Clinical Translational Research Award from AASLD, has received research funding from Gilead and AbbVie, and is on the speakers bureau of Gilead, Salix, and Bayer. He has also done consulting for and been an advisory board member for Gilead.

The current era of new-generation direct-acting antiviral agents have revolutionized the treatment landscape of chronic hepatitis C virus infection, providing short-duration, safe, and consistently effective regimens that achieve SVR or cure in nearly 100% of patients. While achieving SVR is important, even more important is the long-term impact of SVR and whether cure translates into outcomes such as improved mortality or a reduced risk of disease progression. Although improved mortality after SVR has been demonstrated, one of the main drivers of risk of disease progression is the severity of hepatic fibrosis.

Robert J. Wong, MD, MS, is with the department of medicine and is director of research and education, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Alameda Health System – Highland Hospital, Oakland, Calif. He has received a 2017-2019 Clinical Translational Research Award from AASLD, has received research funding from Gilead and AbbVie, and is on the speakers bureau of Gilead, Salix, and Bayer. He has also done consulting for and been an advisory board member for Gilead.

Eradicating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection led to significant decreases in liver stiffness in a systematic review and meta-analysis of nearly 3,000 patients.

Mean liver stiffness fell by 4.1 kPa (kilopascals) (95% confidence interval, 3.3-4.9 kPa) 12 or more months after patients achieved sustained virologic response to treatment, but did not significantly change in patients who did not achieve SVR, reported Siddharth Singh, MD, of the University of San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and his associates in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.038). The results were especially striking among patients who received direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) or who had high baseline levels of inflammation, the investigators added.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Based on these findings, about 47% of patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis at baseline will drop below 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR, they reported. “With this decline in liver stiffness, it is conceivable that risk of liver-related complications would decrease, particularly in patients without cirrhosis,” they added. “Future research is warranted on the impact of magnitude and kinetics of decline in liver stiffness on improvement in liver-related outcomes.”

Eradicating HCV infection was known to decrease liver stiffness, but the magnitude of decline was not well understood. Therefore, the reviewers searched the literature through October 2016 for studies of HCV-infected adults who underwent liver stiffness measurement by vibration-controlled transient elastography before and at least once after completing HCV treatment. All studies also included data on median liver stiffness among patients who did and did not achieve SVR. The search identified 23 observational studies and one post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, for a total of 2,934 patients, of whom 2,214 achieved SVR.

Among patients who achieved SVR, mean liver stiffness dropped by 2.4 kPa at the end of treatment (95% CI, 1.7-3.0 kPa), by 3.1 kPa 1-6 months later (95% CI, 1.6-4.7 kPa), and by 3.2 kPa 6-12 months after completing treatment (90% CI, 2.6-3.9 kPa). A year or more after finishing treatment, patients who achieved SVR had a 28% median decrease in liver stiffness (interquartile range, 22%-35%). However, liver stiffness did not significantly change among patients who did not achieve SVR, the reviewers reported.

Mean liver stiffness declined significantly more among patients who received DAAs (4.5 kPa) than among recipients of interferon-based regimens (2.6 kPa; P = .03). However, studies of DAAs included patients with greater liver stiffness at baseline, which could at least partially explain this discrepancy, the investigators said. Baseline cirrhosis also was associated with a greater decline in liver stiffness (mean, 5.1 kPa, vs. 2.8 kPa in patients without cirrhosis; P = .02), as was high baseline alanine aminotransferase level (P less than .01). Among patients whose baseline liver stiffness measurement exceeded 9.5 kPa, 47% had their liver stiffness drop to less than 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR.

Coinfection with HIV did not significantly alter the magnitude of decline in liver stiffness 6-12 months after treatment in patients who achieved SVR, the reviewers noted. “[Follow-up] assessment after SVR was relatively short; hence, long-term evolution of liver stiffness after antiviral therapy and impact of decline in liver stiffness on patient clinical outcomes could not be ascertained,” they wrote. The studies also did not consistently assess potential confounders such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, and alcohol consumption.

One reviewer disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine. None had conflicts of interest.

Eradicating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection led to significant decreases in liver stiffness in a systematic review and meta-analysis of nearly 3,000 patients.

Mean liver stiffness fell by 4.1 kPa (kilopascals) (95% confidence interval, 3.3-4.9 kPa) 12 or more months after patients achieved sustained virologic response to treatment, but did not significantly change in patients who did not achieve SVR, reported Siddharth Singh, MD, of the University of San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and his associates in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.038). The results were especially striking among patients who received direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) or who had high baseline levels of inflammation, the investigators added.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Based on these findings, about 47% of patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis at baseline will drop below 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR, they reported. “With this decline in liver stiffness, it is conceivable that risk of liver-related complications would decrease, particularly in patients without cirrhosis,” they added. “Future research is warranted on the impact of magnitude and kinetics of decline in liver stiffness on improvement in liver-related outcomes.”

Eradicating HCV infection was known to decrease liver stiffness, but the magnitude of decline was not well understood. Therefore, the reviewers searched the literature through October 2016 for studies of HCV-infected adults who underwent liver stiffness measurement by vibration-controlled transient elastography before and at least once after completing HCV treatment. All studies also included data on median liver stiffness among patients who did and did not achieve SVR. The search identified 23 observational studies and one post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, for a total of 2,934 patients, of whom 2,214 achieved SVR.

Among patients who achieved SVR, mean liver stiffness dropped by 2.4 kPa at the end of treatment (95% CI, 1.7-3.0 kPa), by 3.1 kPa 1-6 months later (95% CI, 1.6-4.7 kPa), and by 3.2 kPa 6-12 months after completing treatment (90% CI, 2.6-3.9 kPa). A year or more after finishing treatment, patients who achieved SVR had a 28% median decrease in liver stiffness (interquartile range, 22%-35%). However, liver stiffness did not significantly change among patients who did not achieve SVR, the reviewers reported.

Mean liver stiffness declined significantly more among patients who received DAAs (4.5 kPa) than among recipients of interferon-based regimens (2.6 kPa; P = .03). However, studies of DAAs included patients with greater liver stiffness at baseline, which could at least partially explain this discrepancy, the investigators said. Baseline cirrhosis also was associated with a greater decline in liver stiffness (mean, 5.1 kPa, vs. 2.8 kPa in patients without cirrhosis; P = .02), as was high baseline alanine aminotransferase level (P less than .01). Among patients whose baseline liver stiffness measurement exceeded 9.5 kPa, 47% had their liver stiffness drop to less than 9.5 kPa after achieving SVR.

Coinfection with HIV did not significantly alter the magnitude of decline in liver stiffness 6-12 months after treatment in patients who achieved SVR, the reviewers noted. “[Follow-up] assessment after SVR was relatively short; hence, long-term evolution of liver stiffness after antiviral therapy and impact of decline in liver stiffness on patient clinical outcomes could not be ascertained,” they wrote. The studies also did not consistently assess potential confounders such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, and alcohol consumption.

One reviewer disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine. None had conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Eradicating chronic hepatitis C virus infection led to significant decreases in liver stiffness.

Major finding: Mean liver stiffness decreased by 4.1 kPa 12 or more months after patients achieved sustained virologic response to treatment, but did not significantly improve in patients who lacked SVR.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 2,934 patients from 23 observational studies and one post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial.

Disclosures: One reviewer disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Model validates use of HCV+ livers for transplant

As the evidence supporting the idea of transplanting livers infected with hepatitis C into patients who do not have the disease continues to mount, a multi-institutional team of researchers has developed a mathematical model that shows when hepatitis C–positive-to-negative transplant may improve survival for patients who might otherwise die awaiting a disease-free liver.

In a report published in the journal Hepatology (doi: 10.1002/hep.29723), the researchers noted how direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have changed the calculus of hepatitis C (HCV) status in liver transplant by reducing the number of HCV-positive patients on the wait list and providing treatment for HCV-negative patients who receive HCV-positive livers. “It is important that further research in this area continues, as we expect that the supply of HCV-positive organs may continue to increase in light of the growing opioid epidemic,” said lead author Jagpreet Chhatwal, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Institute for Technology Assessment in Boston.

Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors claimed their study provides some of the first empirical data for transplanting livers from patients with HCV into patients who do not have the disease.

The researchers performed their analysis using a Markov-based mathematical model known as Simulation of Liver Transplant Candidates (SIM-LT). The model had been validated in previous studies that Dr. Chhatwal and some coauthors had published (Hepatology. 2017;65:777-88; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:115-22). Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors revised the SIM-LT model to simulate a virtual trial of HCV-negative patients on the liver transplant waiting list to compare outcomes in patients willing to accept any liver to those willing to accept only HCV-negative livers.

The patients willing to receive HCV-positive livers were given 12 weeks of DAA therapy preemptively and had a higher risk of graft failure. The model incorporated data from published studies using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and used reported outcomes of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to validate the findings.

The study showed that the clinical benefits of an HCV-negative patient receiving an HCV-positive liver depend on the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. Using the measured change in life-years, the researchers found that patients with a MELD score below 20 actually witnessed reduction in life-years when accepting any liver, but that the benefits of accepting any liver started to accrue at MELD score 20. The benefit topped out at MELD 28, with 0.172 life years gained, but even sustained at 0.06 life years gained at MELD 40.

The effectiveness of using HCV-positive livers may also depend on region. UNOS Region 1 – essentially New England minus western Vermont – has the highest rate of HCV-positive organs, and a patient there with MELD 28 would gain 0.36 life-years by accepting any liver regardless of HCV status. However, Region 7 – the Dakotas and upper Midwest plus Illinois – has the lowest HCV-positive organ rate, and a MELD 28 patient there would gain only 0.1 life-year accepting any liver.

“Transplanting HCV-positive livers into HCV-negative patients receiving preemptive DAA therapy could be a viable option for improving patient survival on the LT waiting list, especially in UNOS regions with high HCV-positive donor organ rates,” said Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors. They concluded that their analysis could help direct future clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of DAA therapy in liver transplant by recognizing patients who could benefit most from accepting HCV-positive donor organs.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and Massachusetts General Hospital Research Scholars Program. Coauthor Fasiha Kanwal, MD, received support from the Veterans Administration Health Services, Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety and Public Health Service.

SOURCE: Chhatwal J et al. Hepatology. doi:10.1002/hep.29723.

As the evidence supporting the idea of transplanting livers infected with hepatitis C into patients who do not have the disease continues to mount, a multi-institutional team of researchers has developed a mathematical model that shows when hepatitis C–positive-to-negative transplant may improve survival for patients who might otherwise die awaiting a disease-free liver.

In a report published in the journal Hepatology (doi: 10.1002/hep.29723), the researchers noted how direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have changed the calculus of hepatitis C (HCV) status in liver transplant by reducing the number of HCV-positive patients on the wait list and providing treatment for HCV-negative patients who receive HCV-positive livers. “It is important that further research in this area continues, as we expect that the supply of HCV-positive organs may continue to increase in light of the growing opioid epidemic,” said lead author Jagpreet Chhatwal, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Institute for Technology Assessment in Boston.

Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors claimed their study provides some of the first empirical data for transplanting livers from patients with HCV into patients who do not have the disease.

The researchers performed their analysis using a Markov-based mathematical model known as Simulation of Liver Transplant Candidates (SIM-LT). The model had been validated in previous studies that Dr. Chhatwal and some coauthors had published (Hepatology. 2017;65:777-88; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:115-22). Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors revised the SIM-LT model to simulate a virtual trial of HCV-negative patients on the liver transplant waiting list to compare outcomes in patients willing to accept any liver to those willing to accept only HCV-negative livers.

The patients willing to receive HCV-positive livers were given 12 weeks of DAA therapy preemptively and had a higher risk of graft failure. The model incorporated data from published studies using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and used reported outcomes of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to validate the findings.

The study showed that the clinical benefits of an HCV-negative patient receiving an HCV-positive liver depend on the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. Using the measured change in life-years, the researchers found that patients with a MELD score below 20 actually witnessed reduction in life-years when accepting any liver, but that the benefits of accepting any liver started to accrue at MELD score 20. The benefit topped out at MELD 28, with 0.172 life years gained, but even sustained at 0.06 life years gained at MELD 40.

The effectiveness of using HCV-positive livers may also depend on region. UNOS Region 1 – essentially New England minus western Vermont – has the highest rate of HCV-positive organs, and a patient there with MELD 28 would gain 0.36 life-years by accepting any liver regardless of HCV status. However, Region 7 – the Dakotas and upper Midwest plus Illinois – has the lowest HCV-positive organ rate, and a MELD 28 patient there would gain only 0.1 life-year accepting any liver.

“Transplanting HCV-positive livers into HCV-negative patients receiving preemptive DAA therapy could be a viable option for improving patient survival on the LT waiting list, especially in UNOS regions with high HCV-positive donor organ rates,” said Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors. They concluded that their analysis could help direct future clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of DAA therapy in liver transplant by recognizing patients who could benefit most from accepting HCV-positive donor organs.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and Massachusetts General Hospital Research Scholars Program. Coauthor Fasiha Kanwal, MD, received support from the Veterans Administration Health Services, Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety and Public Health Service.

SOURCE: Chhatwal J et al. Hepatology. doi:10.1002/hep.29723.

As the evidence supporting the idea of transplanting livers infected with hepatitis C into patients who do not have the disease continues to mount, a multi-institutional team of researchers has developed a mathematical model that shows when hepatitis C–positive-to-negative transplant may improve survival for patients who might otherwise die awaiting a disease-free liver.

In a report published in the journal Hepatology (doi: 10.1002/hep.29723), the researchers noted how direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have changed the calculus of hepatitis C (HCV) status in liver transplant by reducing the number of HCV-positive patients on the wait list and providing treatment for HCV-negative patients who receive HCV-positive livers. “It is important that further research in this area continues, as we expect that the supply of HCV-positive organs may continue to increase in light of the growing opioid epidemic,” said lead author Jagpreet Chhatwal, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Institute for Technology Assessment in Boston.

Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors claimed their study provides some of the first empirical data for transplanting livers from patients with HCV into patients who do not have the disease.

The researchers performed their analysis using a Markov-based mathematical model known as Simulation of Liver Transplant Candidates (SIM-LT). The model had been validated in previous studies that Dr. Chhatwal and some coauthors had published (Hepatology. 2017;65:777-88; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:115-22). Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors revised the SIM-LT model to simulate a virtual trial of HCV-negative patients on the liver transplant waiting list to compare outcomes in patients willing to accept any liver to those willing to accept only HCV-negative livers.

The patients willing to receive HCV-positive livers were given 12 weeks of DAA therapy preemptively and had a higher risk of graft failure. The model incorporated data from published studies using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and used reported outcomes of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to validate the findings.

The study showed that the clinical benefits of an HCV-negative patient receiving an HCV-positive liver depend on the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. Using the measured change in life-years, the researchers found that patients with a MELD score below 20 actually witnessed reduction in life-years when accepting any liver, but that the benefits of accepting any liver started to accrue at MELD score 20. The benefit topped out at MELD 28, with 0.172 life years gained, but even sustained at 0.06 life years gained at MELD 40.

The effectiveness of using HCV-positive livers may also depend on region. UNOS Region 1 – essentially New England minus western Vermont – has the highest rate of HCV-positive organs, and a patient there with MELD 28 would gain 0.36 life-years by accepting any liver regardless of HCV status. However, Region 7 – the Dakotas and upper Midwest plus Illinois – has the lowest HCV-positive organ rate, and a MELD 28 patient there would gain only 0.1 life-year accepting any liver.

“Transplanting HCV-positive livers into HCV-negative patients receiving preemptive DAA therapy could be a viable option for improving patient survival on the LT waiting list, especially in UNOS regions with high HCV-positive donor organ rates,” said Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors. They concluded that their analysis could help direct future clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of DAA therapy in liver transplant by recognizing patients who could benefit most from accepting HCV-positive donor organs.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and Massachusetts General Hospital Research Scholars Program. Coauthor Fasiha Kanwal, MD, received support from the Veterans Administration Health Services, Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety and Public Health Service.

SOURCE: Chhatwal J et al. Hepatology. doi:10.1002/hep.29723.

FROM HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Making hepatitis C virus–positive livers available to HCV-negative patients awaiting liver transplant could improve survival of patients on the liver transplant waiting list.

Major finding: Patients with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 28 willing to receive any liver gained 0.172 life-years.

Data source: Simulated trial using Markov-based mathematical model and data from published studies and the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Disclosures: Dr. Chhatwal and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and Massachusetts General Hospital Research Scholars Program. Coauthor Fasiha Kanwal, MD, received support from the Veterans Administration Health Services, Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety and Public Health Service.

Source: Chhatwal J et al. Hepatology. doi:10.1002/hep.29723.

Hep C screening falling short in neonatal abstinence syndrome infants

SAN DIEGO – A review of care for neonates born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) found that screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is low, based on Medicaid data from the state of Kentucky.

“These children are at high risk for HCV, and the screening rate should really be 100%. We think that it is important to get the message out there,” said Michael Smith, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Duke University, Durham, N.C.

According to the Kentucky Medicaid data, the rates of NAS are not evenly distributed in the state. Stratifying the incidence rates by eight regions, Dr. Smith reported that 33% of the NAS births in 2016 were in region 8. Although region 8 is a rural Appalachian section on the eastern border of the state, the proportion in this region was more than 50% greater than any other region, including the more populated regions containing Louisville, the largest city, and Lexington, the capital.

Statewide, approximately one in three newborns with NAS were screened for HCV, but the rate was as low as 5% in some areas, and low rates were more common in those counties with the highest rates of opioid use and NAS, Dr. Smith said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. Although he acknowledged that rates of HCV screening in newborns with NAS appeared to be increasing when 2015 and 2012 data were compared, “there is still a long way to go.”

“Why is this important? There are a couple of reasons. One is that, if you get children into care early, you are more likely to have follow-up,” Dr. Smith said. Follow-up will be important if, as Dr. Smith predicted, HCV therapies become available for children. When providers know which children are infected, treatment can be initiated more efficiently, and this has implications for risk of transmission and, potentially, for outcomes.

At the University of Louisville, children with NAS are typically screened for HCV, HIV, and other transmissible infections that “travel together,” such as syphilis. The evaluation of the Medicaid data suggested that there were no differences in likelihood of HCV testing for sex and race, but Dr. Smith noted that children placed in foster care were significantly more likely to be tested, likely a reflection of processing regulations.

Overall, there are striking differences in the rates of opioid use, rates of NAS, and likelihood of HCV testing in NAS neonates in eastern Appalachian regions of Kentucky and those in regions in the center of the state closer to academic medical centers. The three regions near the University of Louisville, University of Kentucky in Lexington, and the Ohio River border with Cincinnati are known as “the Golden Triangle,” according to Dr. Smith; these regions are where HCV testing rates in neonates with NAS are higher, but testing still is not uniform.

Currently, HCV testing is mandated for adults in several states, but Dr. Smith emphasized that children with NAS are particularly “vulnerable.” He called for policy changes that would require testing in these children and urged HCV screening regardless of whether official policies are established.

SAN DIEGO – A review of care for neonates born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) found that screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is low, based on Medicaid data from the state of Kentucky.

“These children are at high risk for HCV, and the screening rate should really be 100%. We think that it is important to get the message out there,” said Michael Smith, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Duke University, Durham, N.C.

According to the Kentucky Medicaid data, the rates of NAS are not evenly distributed in the state. Stratifying the incidence rates by eight regions, Dr. Smith reported that 33% of the NAS births in 2016 were in region 8. Although region 8 is a rural Appalachian section on the eastern border of the state, the proportion in this region was more than 50% greater than any other region, including the more populated regions containing Louisville, the largest city, and Lexington, the capital.

Statewide, approximately one in three newborns with NAS were screened for HCV, but the rate was as low as 5% in some areas, and low rates were more common in those counties with the highest rates of opioid use and NAS, Dr. Smith said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. Although he acknowledged that rates of HCV screening in newborns with NAS appeared to be increasing when 2015 and 2012 data were compared, “there is still a long way to go.”

“Why is this important? There are a couple of reasons. One is that, if you get children into care early, you are more likely to have follow-up,” Dr. Smith said. Follow-up will be important if, as Dr. Smith predicted, HCV therapies become available for children. When providers know which children are infected, treatment can be initiated more efficiently, and this has implications for risk of transmission and, potentially, for outcomes.

At the University of Louisville, children with NAS are typically screened for HCV, HIV, and other transmissible infections that “travel together,” such as syphilis. The evaluation of the Medicaid data suggested that there were no differences in likelihood of HCV testing for sex and race, but Dr. Smith noted that children placed in foster care were significantly more likely to be tested, likely a reflection of processing regulations.

Overall, there are striking differences in the rates of opioid use, rates of NAS, and likelihood of HCV testing in NAS neonates in eastern Appalachian regions of Kentucky and those in regions in the center of the state closer to academic medical centers. The three regions near the University of Louisville, University of Kentucky in Lexington, and the Ohio River border with Cincinnati are known as “the Golden Triangle,” according to Dr. Smith; these regions are where HCV testing rates in neonates with NAS are higher, but testing still is not uniform.

Currently, HCV testing is mandated for adults in several states, but Dr. Smith emphasized that children with NAS are particularly “vulnerable.” He called for policy changes that would require testing in these children and urged HCV screening regardless of whether official policies are established.

SAN DIEGO – A review of care for neonates born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) found that screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is low, based on Medicaid data from the state of Kentucky.

“These children are at high risk for HCV, and the screening rate should really be 100%. We think that it is important to get the message out there,” said Michael Smith, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Duke University, Durham, N.C.

According to the Kentucky Medicaid data, the rates of NAS are not evenly distributed in the state. Stratifying the incidence rates by eight regions, Dr. Smith reported that 33% of the NAS births in 2016 were in region 8. Although region 8 is a rural Appalachian section on the eastern border of the state, the proportion in this region was more than 50% greater than any other region, including the more populated regions containing Louisville, the largest city, and Lexington, the capital.

Statewide, approximately one in three newborns with NAS were screened for HCV, but the rate was as low as 5% in some areas, and low rates were more common in those counties with the highest rates of opioid use and NAS, Dr. Smith said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. Although he acknowledged that rates of HCV screening in newborns with NAS appeared to be increasing when 2015 and 2012 data were compared, “there is still a long way to go.”

“Why is this important? There are a couple of reasons. One is that, if you get children into care early, you are more likely to have follow-up,” Dr. Smith said. Follow-up will be important if, as Dr. Smith predicted, HCV therapies become available for children. When providers know which children are infected, treatment can be initiated more efficiently, and this has implications for risk of transmission and, potentially, for outcomes.

At the University of Louisville, children with NAS are typically screened for HCV, HIV, and other transmissible infections that “travel together,” such as syphilis. The evaluation of the Medicaid data suggested that there were no differences in likelihood of HCV testing for sex and race, but Dr. Smith noted that children placed in foster care were significantly more likely to be tested, likely a reflection of processing regulations.

Overall, there are striking differences in the rates of opioid use, rates of NAS, and likelihood of HCV testing in NAS neonates in eastern Appalachian regions of Kentucky and those in regions in the center of the state closer to academic medical centers. The three regions near the University of Louisville, University of Kentucky in Lexington, and the Ohio River border with Cincinnati are known as “the Golden Triangle,” according to Dr. Smith; these regions are where HCV testing rates in neonates with NAS are higher, but testing still is not uniform.

Currently, HCV testing is mandated for adults in several states, but Dr. Smith emphasized that children with NAS are particularly “vulnerable.” He called for policy changes that would require testing in these children and urged HCV screening regardless of whether official policies are established.

AT ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point: In Kentucky, which has one of the highest rates of neonates with NAS, screening rates for HCV remain low.

Major finding:

Data source: Retrospective data analysis of Kentucky Medicaid data.

Disclosures: Dr. Smith reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Study supports routine rapid HCV testing for at-risk youth

Routine finger-stick testing for hepatitis C virus infection is the best screening strategy for 15- to 30-year-olds, provided that at least 6 in every 1,000 have injected drugs, according to the results of a modeling study.

“Currently, nearly all hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission in the United States occurs among young persons who inject drugs,” wrote Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of Boston Medical Center and Boston University and her associates. “We show that routine testing provides the most clinical benefit and best value for money in an urban community health setting where HCV prevalence is high.”

Rapid routine testing consistently yielded more quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at a lower cost than did the current practice of reflexive, risk-based venipuncture testing, the researchers said. They recommended that urban health centers either replace venipuncture diagnostics with routine finger-stick testing or that they ensure follow-up RNA testing when needed so they can link HCV-positive patients to treatment (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix798).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended risk-based HCV testing, but studies indicate that primary care providers often miss the chance to test and have trouble identifying high-risk patients, Dr. Assoumou and her associates said. The standard HCV test is a blood draw for antibody testing followed by confirmatory RNA testing, but a two-step process complicates follow-up.

To compare one-time HCV screening strategies in high-risk settings, the researchers created a decision analytic model using TreeAge Pro 2014 software and input data on prevalence, mortality, treatment costs, and efficacy from an extensive literature review.

Compared with targeted risk-based HCV testing, routine rapid testing performed by dedicated counselors yielded an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year unless the prevalence of injection drug use was less than 0.59%, the prevalence of HCV infection among injection drug users was less than 16%, the reinfection rate exceeded 26 cases per 100 person-years, or all venipuncture antibody tests were followed by confirmatory testing. Routine rapid testing identified 20% of HCV infections in the model, which is four times the rate under current practice. Rates of sustained virologic response were 18% with routine rapid testing and 2% with standard practice.

Routine rapid testing did not dramatically boost QALYs at a population level, the researchers acknowledged, but diagnosing and treating an injection drug user increased life span by an average of 2 years and saved $214,000 per patient in additional costs.

“Rapid testing always provided greater life expectancy than venipuncture testing at either a lower lifetime medical cost or a lower cost/QALY gained,” the investigators concluded. “Future studies are needed to define the programmatic effectiveness of HCV treatment among youth, and testing and treatment acceptability in this population.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Routine finger-stick testing for hepatitis C virus infection is the best screening strategy for 15- to 30-year-olds, provided that at least 6 in every 1,000 have injected drugs, according to the results of a modeling study.

“Currently, nearly all hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission in the United States occurs among young persons who inject drugs,” wrote Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of Boston Medical Center and Boston University and her associates. “We show that routine testing provides the most clinical benefit and best value for money in an urban community health setting where HCV prevalence is high.”

Rapid routine testing consistently yielded more quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at a lower cost than did the current practice of reflexive, risk-based venipuncture testing, the researchers said. They recommended that urban health centers either replace venipuncture diagnostics with routine finger-stick testing or that they ensure follow-up RNA testing when needed so they can link HCV-positive patients to treatment (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix798).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended risk-based HCV testing, but studies indicate that primary care providers often miss the chance to test and have trouble identifying high-risk patients, Dr. Assoumou and her associates said. The standard HCV test is a blood draw for antibody testing followed by confirmatory RNA testing, but a two-step process complicates follow-up.

To compare one-time HCV screening strategies in high-risk settings, the researchers created a decision analytic model using TreeAge Pro 2014 software and input data on prevalence, mortality, treatment costs, and efficacy from an extensive literature review.

Compared with targeted risk-based HCV testing, routine rapid testing performed by dedicated counselors yielded an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year unless the prevalence of injection drug use was less than 0.59%, the prevalence of HCV infection among injection drug users was less than 16%, the reinfection rate exceeded 26 cases per 100 person-years, or all venipuncture antibody tests were followed by confirmatory testing. Routine rapid testing identified 20% of HCV infections in the model, which is four times the rate under current practice. Rates of sustained virologic response were 18% with routine rapid testing and 2% with standard practice.

Routine rapid testing did not dramatically boost QALYs at a population level, the researchers acknowledged, but diagnosing and treating an injection drug user increased life span by an average of 2 years and saved $214,000 per patient in additional costs.

“Rapid testing always provided greater life expectancy than venipuncture testing at either a lower lifetime medical cost or a lower cost/QALY gained,” the investigators concluded. “Future studies are needed to define the programmatic effectiveness of HCV treatment among youth, and testing and treatment acceptability in this population.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Routine finger-stick testing for hepatitis C virus infection is the best screening strategy for 15- to 30-year-olds, provided that at least 6 in every 1,000 have injected drugs, according to the results of a modeling study.

“Currently, nearly all hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission in the United States occurs among young persons who inject drugs,” wrote Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of Boston Medical Center and Boston University and her associates. “We show that routine testing provides the most clinical benefit and best value for money in an urban community health setting where HCV prevalence is high.”

Rapid routine testing consistently yielded more quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at a lower cost than did the current practice of reflexive, risk-based venipuncture testing, the researchers said. They recommended that urban health centers either replace venipuncture diagnostics with routine finger-stick testing or that they ensure follow-up RNA testing when needed so they can link HCV-positive patients to treatment (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix798).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended risk-based HCV testing, but studies indicate that primary care providers often miss the chance to test and have trouble identifying high-risk patients, Dr. Assoumou and her associates said. The standard HCV test is a blood draw for antibody testing followed by confirmatory RNA testing, but a two-step process complicates follow-up.

To compare one-time HCV screening strategies in high-risk settings, the researchers created a decision analytic model using TreeAge Pro 2014 software and input data on prevalence, mortality, treatment costs, and efficacy from an extensive literature review.

Compared with targeted risk-based HCV testing, routine rapid testing performed by dedicated counselors yielded an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year unless the prevalence of injection drug use was less than 0.59%, the prevalence of HCV infection among injection drug users was less than 16%, the reinfection rate exceeded 26 cases per 100 person-years, or all venipuncture antibody tests were followed by confirmatory testing. Routine rapid testing identified 20% of HCV infections in the model, which is four times the rate under current practice. Rates of sustained virologic response were 18% with routine rapid testing and 2% with standard practice.

Routine rapid testing did not dramatically boost QALYs at a population level, the researchers acknowledged, but diagnosing and treating an injection drug user increased life span by an average of 2 years and saved $214,000 per patient in additional costs.

“Rapid testing always provided greater life expectancy than venipuncture testing at either a lower lifetime medical cost or a lower cost/QALY gained,” the investigators concluded. “Future studies are needed to define the programmatic effectiveness of HCV treatment among youth, and testing and treatment acceptability in this population.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Routine finger-stick testing was the most cost-effective way to screen urban adolescents and young adults for hepatitis C virus infection.

Major finding: The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was less than $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year unless prevalence of injection drug use was less than 0.59%, less than 16% of injection drug users had HCV infection, the reinfection rate exceeded 26 cases per 100 person-years, or all venipuncture antibody tests were followed by confirmatory testing.

Data source: A decision analytic model created with TreeAge Pro 2014 and data from an extensive literature review.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Biophysical properties of HCV evolve over course of infection

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The biophysical properties of the hepatitis C virus evolve during the course of infection and shift with dietary changes.

Major finding: Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum showed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, but heterogeneity subsequently increased while infectivity decreased. A 5-week diet of 10% sucrose produced a minor shift toward infectivity that correlated with redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol.

Data source: A study of 13 human liver chimeric mice.

Disclosures: Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

Making Practice Perfect Download

Please click either of the links below to download your free eBook

Onecount Call To Arms

FDA approves new treatment for adults with HCV

The Food and Drug Administration announced on July 18 the approval of Vosevi to treat adults with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1-6 without cirrhosis or with mild cirrhosis.

Vosevi is now the first treatment for patients who have been previously treated with the direct-acting antiviral drug sofosbuvir or other drugs for HCV that inhibit a protein called NS5A. The new drug is a fixed-dose, combination tablet containing sofosbuvir and velpatasvir (both approved before) and a new drug – voxilaprevir.

It is noted that treatment recommendations for Vosevi are different depending on viral genotype and prior treatment history. Vosevi is contraindicated in patients taking the drug rifampin.

“Direct-acting antiviral drugs prevent the virus from multiplying and often cure HCV. Vosevi provides a treatment option for some patients who were not successfully treated with other HCV drugs in the past,” Edward Cox, MD, director of the Office of Antimicrobial Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

Read the full press release on the FDA’s website.

The Food and Drug Administration announced on July 18 the approval of Vosevi to treat adults with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1-6 without cirrhosis or with mild cirrhosis.

Vosevi is now the first treatment for patients who have been previously treated with the direct-acting antiviral drug sofosbuvir or other drugs for HCV that inhibit a protein called NS5A. The new drug is a fixed-dose, combination tablet containing sofosbuvir and velpatasvir (both approved before) and a new drug – voxilaprevir.

It is noted that treatment recommendations for Vosevi are different depending on viral genotype and prior treatment history. Vosevi is contraindicated in patients taking the drug rifampin.

“Direct-acting antiviral drugs prevent the virus from multiplying and often cure HCV. Vosevi provides a treatment option for some patients who were not successfully treated with other HCV drugs in the past,” Edward Cox, MD, director of the Office of Antimicrobial Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

Read the full press release on the FDA’s website.

The Food and Drug Administration announced on July 18 the approval of Vosevi to treat adults with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1-6 without cirrhosis or with mild cirrhosis.