User login

HCV Hub

AbbVie

acid

addicted

addiction

adolescent

adult sites

Advocacy

advocacy

agitated states

AJO, postsurgical analgesic, knee, replacement, surgery

alcohol

amphetamine

androgen

antibody

apple cider vinegar

assistance

Assistance

association

at home

attorney

audit

ayurvedic

baby

ban

baricitinib

bed bugs

best

bible

bisexual

black

bleach

blog

bulimia nervosa

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cervical cancer, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, IVIM, diffusion-weighted MRI, DWI

charlie sheen

cheap

cheapest

child

childhood

childlike

children

chronic fatigue syndrome

Cladribine Tablets

cocaine

cock

combination therapies, synergistic antitumor efficacy, pertuzumab, trastuzumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, palbociclib, letrozole, lapatinib, docetaxel, trametinib, dabrafenib, carflzomib, lenalidomide

contagious

Cortical Lesions

cream

creams

crime

criminal

cure

dangerous

dangers

dasabuvir

Dasabuvir

dead

deadly

death

dementia

dependence

dependent

depression

dermatillomania

die

diet

direct-acting antivirals

Disability

Discount

discount

dog

drink

drug abuse

drug-induced

dying

eastern medicine

eat

ect

eczema

electroconvulsive therapy

electromagnetic therapy

electrotherapy

epa

epilepsy

erectile dysfunction

explosive disorder

fake

Fake-ovir

fatal

fatalities

fatality

fibromyalgia

financial

Financial

fish oil

food

foods

foundation

free

Gabriel Pardo

gaston

general hospital

genetic

geriatric

Giancarlo Comi

gilead

Gilead

glaucoma

Glenn S. Williams

Glenn Williams

Gloria Dalla Costa

gonorrhea

Greedy

greedy

guns

hallucinations

harvoni

Harvoni

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

Hidradenitis Suppurativa,

holistic

home

home remedies

home remedy

homeopathic

homeopathy

hydrocortisone

ice

image

images

job

kid

kids

kill

killer

laser

lawsuit

lawyer

ledipasvir

Ledipasvir

lesbian

lesions

lights

liver

lupus

marijuana

melancholic

memory loss

menopausal

mental retardation

military

milk

moisturizers

monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs

MRI

MS

murder

national

natural

natural cure

natural cures

natural medications

natural medicine

natural medicines

natural remedies

natural remedy

natural treatment

natural treatments

naturally

Needy

needy

Neurology Reviews

neuropathic

nightclub massacre

nightclub shooting

nude

nudity

nutraceuticals

OASIS

oasis

off label

ombitasvir

Ombitasvir

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir

orlando shooting

overactive thyroid gland

overdose

overdosed

Paolo Preziosa

paritaprevir

Paritaprevir

pediatric

pedophile

photo

photos

picture

post partum

postnatal

pregnancy

pregnant

prenatal

prepartum

prison

program

Program

Protest

protest

psychedelics

pulse nightclub

puppy

purchase

purchasing

rape

recall

recreational drug

Rehabilitation

Retinal Measurements

retrograde ejaculation

risperdal

ritonavir

Ritonavir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

robin williams

sales

sasquatch

schizophrenia

seizure

seizures

sex

sexual

sexy

shock treatment

silver

sleep disorders

smoking

sociopath

sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir

sovaldi

ssri

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

support

Support

Support Path

teen

teenage

teenagers

Telerehabilitation

testosterone

Th17

Th17:FoxP3+Treg cell ratio

Th22

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treatment resistant

V Pak

vagina

velpatasvir

Viekira Pa

Viekira Pak

viekira pak

violence

virgin

vitamin

VPak

weight loss

withdrawal

wrinkles

xxx

young adult

young adults

zoloft

financial

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

Liver cancer risk lower after sustained response to DAAs

Individuals with hepatitis C infection who achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR) to treatment with direct-acting antivirals had a significantly lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a new study suggests.

A retrospective cohort study of 22,500 U.S. veterans with hepatitis C who had been treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) found those with an SVR had a 72% lower risk of HCC, compared with those who did not achieve that response (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36; P less than .0001), even after adjusting for demographics as well as clinical and health utilization factors.

“These data show that successful eradication of HCV [hepatitis C virus] confers a benefit in DAA-treated patients,” wrote Fasiha Kanwal, MD, from the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston and her coauthors. “Although a few recent studies have raised concerns that DAA might accelerate the risk of HCC in some patients early in the course of treatment, we did not find any factors that differentiated patients with HCC that developed during DAA treatment.”

The results highlighted the importance of early treatment with antivirals, beginning well before the patients showed signs of progressing to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, the investigators noted.

“Delaying treatment until patients progress to cirrhosis might be associated with substantial downstream costs incurred as part of lifelong HCC surveillance and/or management of HCC,” they wrote.

Sustained virologic response to DAAs also was associated with a longer time to diagnosis, and patients who didn’t achieve it showed higher rates of cancer much earlier. The most common antivirals used were sofosbuvir (75.2%; 51.1% in combination with ledipasvir), the combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir (23.3%), daclatasvir-based treatments (0.8%), and simeprevir (0.7%).

While the patients achieved SVR that showed similarly beneficial effects on HCC risk in patients with or without cirrhosis, the authors also noted that patients with cirrhosis had a nearly fivefold greater risk of developing cancer than did those without (HR, 4.73; 95% CI, 3.34-6.68). Similarly, patients with a fibrosis score (FIB-4) greater than 3.25 had a sixfold higher risk of HCC, compared with those with a value of 1.45 or lower.

Researchers commented that, at this level of risk, surveillance for HCC in these patients may be cost effective.

“Based on these data, HCC surveillance or risk modification may be needed for all patients who have progressed to cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis (as indicated by high FIB-4) at the time of SVR,” they wrote.

Alcohol use was also associated with a significantly higher annual incidence of HCC (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.11-2.18).

Among the study cohort, 39% had cirrhosis, 29.7% had advanced fibrosis, and nearly one-quarter had previously been treated for hepatitis C infection. More than 40% also had diabetes, 61.4% reported alcohol use, and 54.2% had a history of drug use.

“DAAs offer a chance of cure for all patients with HCV, including patients with advanced cirrhosis, older patients, and those with alcohol use – all characteristics independently associated with risk of HCC in HCV,” the authors explained. “These data show the treated population has changed significantly in the DAA era to include many patients with other HCC risk factors; these differences likely explain why the newer cohorts of DAA-treated patients face higher absolute HCC risk than expected, based on historic data.”

The study was partly supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs’ Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The availability of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of hepatitis C. Sustained virologic response (SVR) can be routinely achieved in more than 95% of patients – except in those with decompensated cirrhosis – with a 12-week course of these oral drugs, which have minimal adverse effects. Thus, guidelines recommend that all patients with hepatitis C should be treated with DAAs.1 It was a shock to the medical community when the recent Cochrane review concluded there was insufficient evidence to confirm or reject an effect of DAA therapy on HCV-related morbidity or all-cause mortality.2 The authors cautioned that the lack of valid evidence for DAAs’ effectiveness and the possibility of potential harm should be considered before treating people with hepatitis C with DAAs. Their conclusion was in part based on their rejection of SVR as a valid surrogate for clinical outcome. Previous studies of interferon-based therapies showed that SVR was associated with improvement in liver histology, decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mortality.

Treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs represents one out of a handful of cases in which we can claim that a cure for a chronic disease is possible; however, treatment must be initiated early before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis to prevent a persistent, though greatly reduced, risk of HCC. Physicians managing patients with hepatitis C should make treatment decisions based on evidence from the entire literature – which supports claims of the DAA treatment’s benefits and refutes allegations of its harmfulness – and should not be swayed by the misguided conclusions of the Cochrane review.

References

1. AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed on July 2, 2017.

2. Jakobsen J.C., Nielsen E.E., Feinberg J., et al. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 6;6:CD012143.

3. Curry M.P., O’Leary J.G., Bzowej N., et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2618-28.

4. Kanwal F., Kramer J., Asch S.M., et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 19. pii: S0016-5085(17)35797.

Anna S. Lok, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. She has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead through the University of Michigan.

The availability of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of hepatitis C. Sustained virologic response (SVR) can be routinely achieved in more than 95% of patients – except in those with decompensated cirrhosis – with a 12-week course of these oral drugs, which have minimal adverse effects. Thus, guidelines recommend that all patients with hepatitis C should be treated with DAAs.1 It was a shock to the medical community when the recent Cochrane review concluded there was insufficient evidence to confirm or reject an effect of DAA therapy on HCV-related morbidity or all-cause mortality.2 The authors cautioned that the lack of valid evidence for DAAs’ effectiveness and the possibility of potential harm should be considered before treating people with hepatitis C with DAAs. Their conclusion was in part based on their rejection of SVR as a valid surrogate for clinical outcome. Previous studies of interferon-based therapies showed that SVR was associated with improvement in liver histology, decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mortality.

Treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs represents one out of a handful of cases in which we can claim that a cure for a chronic disease is possible; however, treatment must be initiated early before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis to prevent a persistent, though greatly reduced, risk of HCC. Physicians managing patients with hepatitis C should make treatment decisions based on evidence from the entire literature – which supports claims of the DAA treatment’s benefits and refutes allegations of its harmfulness – and should not be swayed by the misguided conclusions of the Cochrane review.

References

1. AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed on July 2, 2017.

2. Jakobsen J.C., Nielsen E.E., Feinberg J., et al. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 6;6:CD012143.

3. Curry M.P., O’Leary J.G., Bzowej N., et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2618-28.

4. Kanwal F., Kramer J., Asch S.M., et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 19. pii: S0016-5085(17)35797.

Anna S. Lok, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. She has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead through the University of Michigan.

The availability of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of hepatitis C. Sustained virologic response (SVR) can be routinely achieved in more than 95% of patients – except in those with decompensated cirrhosis – with a 12-week course of these oral drugs, which have minimal adverse effects. Thus, guidelines recommend that all patients with hepatitis C should be treated with DAAs.1 It was a shock to the medical community when the recent Cochrane review concluded there was insufficient evidence to confirm or reject an effect of DAA therapy on HCV-related morbidity or all-cause mortality.2 The authors cautioned that the lack of valid evidence for DAAs’ effectiveness and the possibility of potential harm should be considered before treating people with hepatitis C with DAAs. Their conclusion was in part based on their rejection of SVR as a valid surrogate for clinical outcome. Previous studies of interferon-based therapies showed that SVR was associated with improvement in liver histology, decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mortality.

Treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs represents one out of a handful of cases in which we can claim that a cure for a chronic disease is possible; however, treatment must be initiated early before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis to prevent a persistent, though greatly reduced, risk of HCC. Physicians managing patients with hepatitis C should make treatment decisions based on evidence from the entire literature – which supports claims of the DAA treatment’s benefits and refutes allegations of its harmfulness – and should not be swayed by the misguided conclusions of the Cochrane review.

References

1. AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed on July 2, 2017.

2. Jakobsen J.C., Nielsen E.E., Feinberg J., et al. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 6;6:CD012143.

3. Curry M.P., O’Leary J.G., Bzowej N., et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2618-28.

4. Kanwal F., Kramer J., Asch S.M., et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 19. pii: S0016-5085(17)35797.

Anna S. Lok, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. She has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead through the University of Michigan.

Individuals with hepatitis C infection who achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR) to treatment with direct-acting antivirals had a significantly lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a new study suggests.

A retrospective cohort study of 22,500 U.S. veterans with hepatitis C who had been treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) found those with an SVR had a 72% lower risk of HCC, compared with those who did not achieve that response (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36; P less than .0001), even after adjusting for demographics as well as clinical and health utilization factors.

“These data show that successful eradication of HCV [hepatitis C virus] confers a benefit in DAA-treated patients,” wrote Fasiha Kanwal, MD, from the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston and her coauthors. “Although a few recent studies have raised concerns that DAA might accelerate the risk of HCC in some patients early in the course of treatment, we did not find any factors that differentiated patients with HCC that developed during DAA treatment.”

The results highlighted the importance of early treatment with antivirals, beginning well before the patients showed signs of progressing to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, the investigators noted.

“Delaying treatment until patients progress to cirrhosis might be associated with substantial downstream costs incurred as part of lifelong HCC surveillance and/or management of HCC,” they wrote.

Sustained virologic response to DAAs also was associated with a longer time to diagnosis, and patients who didn’t achieve it showed higher rates of cancer much earlier. The most common antivirals used were sofosbuvir (75.2%; 51.1% in combination with ledipasvir), the combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir (23.3%), daclatasvir-based treatments (0.8%), and simeprevir (0.7%).

While the patients achieved SVR that showed similarly beneficial effects on HCC risk in patients with or without cirrhosis, the authors also noted that patients with cirrhosis had a nearly fivefold greater risk of developing cancer than did those without (HR, 4.73; 95% CI, 3.34-6.68). Similarly, patients with a fibrosis score (FIB-4) greater than 3.25 had a sixfold higher risk of HCC, compared with those with a value of 1.45 or lower.

Researchers commented that, at this level of risk, surveillance for HCC in these patients may be cost effective.

“Based on these data, HCC surveillance or risk modification may be needed for all patients who have progressed to cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis (as indicated by high FIB-4) at the time of SVR,” they wrote.

Alcohol use was also associated with a significantly higher annual incidence of HCC (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.11-2.18).

Among the study cohort, 39% had cirrhosis, 29.7% had advanced fibrosis, and nearly one-quarter had previously been treated for hepatitis C infection. More than 40% also had diabetes, 61.4% reported alcohol use, and 54.2% had a history of drug use.

“DAAs offer a chance of cure for all patients with HCV, including patients with advanced cirrhosis, older patients, and those with alcohol use – all characteristics independently associated with risk of HCC in HCV,” the authors explained. “These data show the treated population has changed significantly in the DAA era to include many patients with other HCC risk factors; these differences likely explain why the newer cohorts of DAA-treated patients face higher absolute HCC risk than expected, based on historic data.”

The study was partly supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs’ Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Individuals with hepatitis C infection who achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR) to treatment with direct-acting antivirals had a significantly lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a new study suggests.

A retrospective cohort study of 22,500 U.S. veterans with hepatitis C who had been treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) found those with an SVR had a 72% lower risk of HCC, compared with those who did not achieve that response (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36; P less than .0001), even after adjusting for demographics as well as clinical and health utilization factors.

“These data show that successful eradication of HCV [hepatitis C virus] confers a benefit in DAA-treated patients,” wrote Fasiha Kanwal, MD, from the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston and her coauthors. “Although a few recent studies have raised concerns that DAA might accelerate the risk of HCC in some patients early in the course of treatment, we did not find any factors that differentiated patients with HCC that developed during DAA treatment.”

The results highlighted the importance of early treatment with antivirals, beginning well before the patients showed signs of progressing to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, the investigators noted.

“Delaying treatment until patients progress to cirrhosis might be associated with substantial downstream costs incurred as part of lifelong HCC surveillance and/or management of HCC,” they wrote.

Sustained virologic response to DAAs also was associated with a longer time to diagnosis, and patients who didn’t achieve it showed higher rates of cancer much earlier. The most common antivirals used were sofosbuvir (75.2%; 51.1% in combination with ledipasvir), the combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir (23.3%), daclatasvir-based treatments (0.8%), and simeprevir (0.7%).

While the patients achieved SVR that showed similarly beneficial effects on HCC risk in patients with or without cirrhosis, the authors also noted that patients with cirrhosis had a nearly fivefold greater risk of developing cancer than did those without (HR, 4.73; 95% CI, 3.34-6.68). Similarly, patients with a fibrosis score (FIB-4) greater than 3.25 had a sixfold higher risk of HCC, compared with those with a value of 1.45 or lower.

Researchers commented that, at this level of risk, surveillance for HCC in these patients may be cost effective.

“Based on these data, HCC surveillance or risk modification may be needed for all patients who have progressed to cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis (as indicated by high FIB-4) at the time of SVR,” they wrote.

Alcohol use was also associated with a significantly higher annual incidence of HCC (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.11-2.18).

Among the study cohort, 39% had cirrhosis, 29.7% had advanced fibrosis, and nearly one-quarter had previously been treated for hepatitis C infection. More than 40% also had diabetes, 61.4% reported alcohol use, and 54.2% had a history of drug use.

“DAAs offer a chance of cure for all patients with HCV, including patients with advanced cirrhosis, older patients, and those with alcohol use – all characteristics independently associated with risk of HCC in HCV,” the authors explained. “These data show the treated population has changed significantly in the DAA era to include many patients with other HCC risk factors; these differences likely explain why the newer cohorts of DAA-treated patients face higher absolute HCC risk than expected, based on historic data.”

The study was partly supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs’ Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Individuals who achieved an SVR to antiviral treatment for hepatitis C infection had a 72% lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma than those who do not show a sustained response.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study in 22,500 U.S. veterans with hepatitis C.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Hepatitis C is a pediatric disease now

The baby looked perfect: healthy term male, weight at the 60th percentile, normal exam. The mother, a 26-year-old diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during her pregnancy, looked alternately hopeful and horrified as I explained what implications her infection could have for her baby.

“Most babies will be fine,” I explained. “Of all mothers with hepatitis C infection, just under 6% will pass the infection on to their babies.” Transmission rates are twice as high in infants born to women with high HCV viral loads or those coinfected with HIV. The risk of transmission from women with undetectable HCV RNA is almost zero. Unfortunately, this mother did not fall into that category.

At that moment, however, I didn’t have time to be concerned about the numbers. My focus was one mother and her newborn baby.

“What if my baby is one of the unlucky ones who gets infected?” the mother asked, cuddling her infant. “What then?”

We know a lot about the course of hepatitis C in adults. An estimated 75%-86% of those infected will go on to develop chronic infection. Long-term sequelae include cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The course of HCV in children appears to be different. Twenty-five percent to 40% of vertically infected children will spontaneously clear their infection, most by 2 years of age. Occasionally, that might not happen until 7 years of age. Most who are chronically infected experience few symptoms, and fortunately cirrhosis and liver failure rarely present in childhood. In a large cohort of Italian children, half of whom were thought to be infected perinatally, less than 2% progressed to decompensated cirrhosis after 10 years of infection. According to the CDC, most children infected at birth “do well during childhood,” but more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of perinatal hepatitis C in children.

New antivirals have revolutionized the care of HCV-infected adults and now offer the hope of cure for up to 90%. None of these drugs are currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, although clinical trials are underway. Because most cases of HCV in children are indolent, some children may not require treatment until adulthood.

July 28th was World Hepatitis Day and this year’s theme was Eliminate Hepatitis. To eliminate the problem of hepatitis C in children, pediatricians and others involved in the care of children need to get involved.

We need to know the scope of the problem

Since 2015, Kentucky has mandated reporting of all HCV-infected pregnant women and children through age 60 months, as well as all infants born to all HCV-infected women. At present though, there is substantial variability in state reporting requirements. We likely need a standardized case definition for perinatal HCV and national reporting criteria.

We need some clear guidance about testing during pregnancy

This should come from public health authorities, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Jonathan Mermin, MD, director of CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, has said, “Women are screened throughout pregnancy for many conditions that threaten their health. An expectant mother at risk for hepatitis C deserves to be tested. Knowing her status is the only way she can access the best hepatitis care and treatment – both for herself and her baby.” Yet, routine hepatitis C testing is not recommended during pregnancy, in part because there are no established interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HCV. Instead, women are to be screened for risk factors and tested if they are present. As we learned with hepatitis B and HIV, risk factor screening is hard and misses individuals who are infected.

We need to ensure that HCV-exposed infants are identified and followed appropriately.

In a study of HCV-exposed infants born to women in Philadelphia, 84% did not receive adequate testing for HCV infection. In human terms, 537 children were born to HCV-positive mothers during the study period and 4 of 84 (5%) children tested were found to be infected. Assuming that 5% of HCV-exposed infants will develop chronic infection, 23 additional children were undiagnosed and, therefore, were not being followed for potential sequelae.

HCV-infected mothers in this study were more likely than non-infected mothers to be socioeconomically disadvantaged – specifically, unmarried, less educated, and publicly insured – suggesting that access to care may have played a role. When you add in drug use as a common risk factor for HCV infection, it is easy to understand why some at-risk infants are lost to follow-up.

Investigators in the Philadelphia study suggested that there might be more to the story. They proposed that pediatricians might be unaware of the need for testing because they had not been alerted to the mother’s HCV status by the obstetrician, the birthing hospital, or the mother herself. Finally, they theorized that many pediatricians “may be unaware or skeptical of the guidelines for testing children exposed to HCV.” This is a problem that we can solve.

I finished the visit with this mother by reassuring her that she could breastfeed her infant as planned as long as she did not have cracked or bleeding nipples. I also explained the schedule for testing. A 2002 National Institutes of Health consensus statement recommends that infants perinatally exposed to HCV have two HCV RNA tests between 2 and 6 months of age and/or be tested for HCV antibodies after 15 months. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis C Infection in Infants, Children, and Adolescents recommend testing for HCV antibodies at 18 months of age (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Jun;54[6]:838-55). If a family requests earlier testing, a serum HCV RNA test can be done as early as 2 months of age. If positive, NASPGHAN recommends testing after 12 months of age to evaluate for chronic infection.

My practice has adopted the National Institutes of Health consensus statement approach because many of the families we see experience significant anxiety about the diagnosis, and this mother was no exception. As noted in the expert guidelines, this was a situation in which “early exclusion of HCV infection is reassuring and may be worth the added expense.”

“So first test at 2 months?” she asked. “Until then, we can’t do anything but wait?”

It is estimated that there are 23,000 to 46,000 U.S. children living with HCV. The wait for pediatricians is over. , and we need to educate ourselves about diagnosis and management. A first step might be to begin asking expectant mothers and the mothers of newborns if they know their HCV status.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

The baby looked perfect: healthy term male, weight at the 60th percentile, normal exam. The mother, a 26-year-old diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during her pregnancy, looked alternately hopeful and horrified as I explained what implications her infection could have for her baby.

“Most babies will be fine,” I explained. “Of all mothers with hepatitis C infection, just under 6% will pass the infection on to their babies.” Transmission rates are twice as high in infants born to women with high HCV viral loads or those coinfected with HIV. The risk of transmission from women with undetectable HCV RNA is almost zero. Unfortunately, this mother did not fall into that category.

At that moment, however, I didn’t have time to be concerned about the numbers. My focus was one mother and her newborn baby.

“What if my baby is one of the unlucky ones who gets infected?” the mother asked, cuddling her infant. “What then?”

We know a lot about the course of hepatitis C in adults. An estimated 75%-86% of those infected will go on to develop chronic infection. Long-term sequelae include cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The course of HCV in children appears to be different. Twenty-five percent to 40% of vertically infected children will spontaneously clear their infection, most by 2 years of age. Occasionally, that might not happen until 7 years of age. Most who are chronically infected experience few symptoms, and fortunately cirrhosis and liver failure rarely present in childhood. In a large cohort of Italian children, half of whom were thought to be infected perinatally, less than 2% progressed to decompensated cirrhosis after 10 years of infection. According to the CDC, most children infected at birth “do well during childhood,” but more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of perinatal hepatitis C in children.

New antivirals have revolutionized the care of HCV-infected adults and now offer the hope of cure for up to 90%. None of these drugs are currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, although clinical trials are underway. Because most cases of HCV in children are indolent, some children may not require treatment until adulthood.

July 28th was World Hepatitis Day and this year’s theme was Eliminate Hepatitis. To eliminate the problem of hepatitis C in children, pediatricians and others involved in the care of children need to get involved.

We need to know the scope of the problem

Since 2015, Kentucky has mandated reporting of all HCV-infected pregnant women and children through age 60 months, as well as all infants born to all HCV-infected women. At present though, there is substantial variability in state reporting requirements. We likely need a standardized case definition for perinatal HCV and national reporting criteria.

We need some clear guidance about testing during pregnancy

This should come from public health authorities, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Jonathan Mermin, MD, director of CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, has said, “Women are screened throughout pregnancy for many conditions that threaten their health. An expectant mother at risk for hepatitis C deserves to be tested. Knowing her status is the only way she can access the best hepatitis care and treatment – both for herself and her baby.” Yet, routine hepatitis C testing is not recommended during pregnancy, in part because there are no established interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HCV. Instead, women are to be screened for risk factors and tested if they are present. As we learned with hepatitis B and HIV, risk factor screening is hard and misses individuals who are infected.

We need to ensure that HCV-exposed infants are identified and followed appropriately.

In a study of HCV-exposed infants born to women in Philadelphia, 84% did not receive adequate testing for HCV infection. In human terms, 537 children were born to HCV-positive mothers during the study period and 4 of 84 (5%) children tested were found to be infected. Assuming that 5% of HCV-exposed infants will develop chronic infection, 23 additional children were undiagnosed and, therefore, were not being followed for potential sequelae.

HCV-infected mothers in this study were more likely than non-infected mothers to be socioeconomically disadvantaged – specifically, unmarried, less educated, and publicly insured – suggesting that access to care may have played a role. When you add in drug use as a common risk factor for HCV infection, it is easy to understand why some at-risk infants are lost to follow-up.

Investigators in the Philadelphia study suggested that there might be more to the story. They proposed that pediatricians might be unaware of the need for testing because they had not been alerted to the mother’s HCV status by the obstetrician, the birthing hospital, or the mother herself. Finally, they theorized that many pediatricians “may be unaware or skeptical of the guidelines for testing children exposed to HCV.” This is a problem that we can solve.

I finished the visit with this mother by reassuring her that she could breastfeed her infant as planned as long as she did not have cracked or bleeding nipples. I also explained the schedule for testing. A 2002 National Institutes of Health consensus statement recommends that infants perinatally exposed to HCV have two HCV RNA tests between 2 and 6 months of age and/or be tested for HCV antibodies after 15 months. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis C Infection in Infants, Children, and Adolescents recommend testing for HCV antibodies at 18 months of age (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Jun;54[6]:838-55). If a family requests earlier testing, a serum HCV RNA test can be done as early as 2 months of age. If positive, NASPGHAN recommends testing after 12 months of age to evaluate for chronic infection.

My practice has adopted the National Institutes of Health consensus statement approach because many of the families we see experience significant anxiety about the diagnosis, and this mother was no exception. As noted in the expert guidelines, this was a situation in which “early exclusion of HCV infection is reassuring and may be worth the added expense.”

“So first test at 2 months?” she asked. “Until then, we can’t do anything but wait?”

It is estimated that there are 23,000 to 46,000 U.S. children living with HCV. The wait for pediatricians is over. , and we need to educate ourselves about diagnosis and management. A first step might be to begin asking expectant mothers and the mothers of newborns if they know their HCV status.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

The baby looked perfect: healthy term male, weight at the 60th percentile, normal exam. The mother, a 26-year-old diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during her pregnancy, looked alternately hopeful and horrified as I explained what implications her infection could have for her baby.

“Most babies will be fine,” I explained. “Of all mothers with hepatitis C infection, just under 6% will pass the infection on to their babies.” Transmission rates are twice as high in infants born to women with high HCV viral loads or those coinfected with HIV. The risk of transmission from women with undetectable HCV RNA is almost zero. Unfortunately, this mother did not fall into that category.

At that moment, however, I didn’t have time to be concerned about the numbers. My focus was one mother and her newborn baby.

“What if my baby is one of the unlucky ones who gets infected?” the mother asked, cuddling her infant. “What then?”

We know a lot about the course of hepatitis C in adults. An estimated 75%-86% of those infected will go on to develop chronic infection. Long-term sequelae include cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The course of HCV in children appears to be different. Twenty-five percent to 40% of vertically infected children will spontaneously clear their infection, most by 2 years of age. Occasionally, that might not happen until 7 years of age. Most who are chronically infected experience few symptoms, and fortunately cirrhosis and liver failure rarely present in childhood. In a large cohort of Italian children, half of whom were thought to be infected perinatally, less than 2% progressed to decompensated cirrhosis after 10 years of infection. According to the CDC, most children infected at birth “do well during childhood,” but more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of perinatal hepatitis C in children.

New antivirals have revolutionized the care of HCV-infected adults and now offer the hope of cure for up to 90%. None of these drugs are currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, although clinical trials are underway. Because most cases of HCV in children are indolent, some children may not require treatment until adulthood.

July 28th was World Hepatitis Day and this year’s theme was Eliminate Hepatitis. To eliminate the problem of hepatitis C in children, pediatricians and others involved in the care of children need to get involved.

We need to know the scope of the problem

Since 2015, Kentucky has mandated reporting of all HCV-infected pregnant women and children through age 60 months, as well as all infants born to all HCV-infected women. At present though, there is substantial variability in state reporting requirements. We likely need a standardized case definition for perinatal HCV and national reporting criteria.

We need some clear guidance about testing during pregnancy

This should come from public health authorities, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Jonathan Mermin, MD, director of CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, has said, “Women are screened throughout pregnancy for many conditions that threaten their health. An expectant mother at risk for hepatitis C deserves to be tested. Knowing her status is the only way she can access the best hepatitis care and treatment – both for herself and her baby.” Yet, routine hepatitis C testing is not recommended during pregnancy, in part because there are no established interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HCV. Instead, women are to be screened for risk factors and tested if they are present. As we learned with hepatitis B and HIV, risk factor screening is hard and misses individuals who are infected.

We need to ensure that HCV-exposed infants are identified and followed appropriately.

In a study of HCV-exposed infants born to women in Philadelphia, 84% did not receive adequate testing for HCV infection. In human terms, 537 children were born to HCV-positive mothers during the study period and 4 of 84 (5%) children tested were found to be infected. Assuming that 5% of HCV-exposed infants will develop chronic infection, 23 additional children were undiagnosed and, therefore, were not being followed for potential sequelae.

HCV-infected mothers in this study were more likely than non-infected mothers to be socioeconomically disadvantaged – specifically, unmarried, less educated, and publicly insured – suggesting that access to care may have played a role. When you add in drug use as a common risk factor for HCV infection, it is easy to understand why some at-risk infants are lost to follow-up.

Investigators in the Philadelphia study suggested that there might be more to the story. They proposed that pediatricians might be unaware of the need for testing because they had not been alerted to the mother’s HCV status by the obstetrician, the birthing hospital, or the mother herself. Finally, they theorized that many pediatricians “may be unaware or skeptical of the guidelines for testing children exposed to HCV.” This is a problem that we can solve.

I finished the visit with this mother by reassuring her that she could breastfeed her infant as planned as long as she did not have cracked or bleeding nipples. I also explained the schedule for testing. A 2002 National Institutes of Health consensus statement recommends that infants perinatally exposed to HCV have two HCV RNA tests between 2 and 6 months of age and/or be tested for HCV antibodies after 15 months. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis C Infection in Infants, Children, and Adolescents recommend testing for HCV antibodies at 18 months of age (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Jun;54[6]:838-55). If a family requests earlier testing, a serum HCV RNA test can be done as early as 2 months of age. If positive, NASPGHAN recommends testing after 12 months of age to evaluate for chronic infection.

My practice has adopted the National Institutes of Health consensus statement approach because many of the families we see experience significant anxiety about the diagnosis, and this mother was no exception. As noted in the expert guidelines, this was a situation in which “early exclusion of HCV infection is reassuring and may be worth the added expense.”

“So first test at 2 months?” she asked. “Until then, we can’t do anything but wait?”

It is estimated that there are 23,000 to 46,000 U.S. children living with HCV. The wait for pediatricians is over. , and we need to educate ourselves about diagnosis and management. A first step might be to begin asking expectant mothers and the mothers of newborns if they know their HCV status.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

HCV/HIV-coinfected teens rapidly progress to advanced liver disease

MADRID – Roughly one in four children with vertically transmitted hepatitis C virus (HCV)/HIV coinfection will progress to advanced hepatic fibrosis by age 20 years despite treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, Carolina Fernández McPhee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This rate was nearly five times higher than in matched children with vertically acquired HCV monoinfection in a multicenter retrospective study, according to Dr. McPhee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid.

She presented a multicenter retrospective study of liver disease progression in 71 HCV/HIV coinfected children and 71 age- and sex-matched HCV-monoinfected children. The coinfected children are being followed in CORISPES (the Spanish Cohort of HIV-infected Children), where they receive state-of-the-art care.

All was quiet through age 9 years, with no progression to liver fibrosis in either patient group. Among patients followed to age 20 years, however, 9 (24%) of 38 HCV/HIV-coinfected patients showed progression to advanced fibrosis, compared with just 3 (6%) of 54 patients with HCV only.

Of HCV/HIV coinfected patients, 73% were infected with the hard to treat viral genotypes 1 or 4, compared with 93% of patients with HCV-only.

In the study group, 22 patients with HCV/HIV and 52 patients with HCV-only underwent treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. At the time of treatment, three coinfected patients already had cirrhosis, another eight had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and half had no or mild fibrosis. In contrast, only one patient with HCV monoinfection had cirrhosis, four had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and the rest – nearly 90% of the total group – had no or mild fibrosis.

At treatment initiation, 96% of the HCV/HIV group were on antiretroviral therapy, 86% showed suppression of HIV RNA, 44% had AIDS, and 32% had a CD4 count below 500 cells/mm3.

The sustained viral response rate was similar in the two groups of patients – 41% in the HCV/HIV group and 42% in HCV-only patients – despite the fact that the HCV monoinfected patients had a higher prevalence of the tough to treat genotypes.

Roughly 12 million people worldwide are coinfected with HCV and HIV.

Dr. McPhee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MADRID – Roughly one in four children with vertically transmitted hepatitis C virus (HCV)/HIV coinfection will progress to advanced hepatic fibrosis by age 20 years despite treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, Carolina Fernández McPhee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This rate was nearly five times higher than in matched children with vertically acquired HCV monoinfection in a multicenter retrospective study, according to Dr. McPhee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid.

She presented a multicenter retrospective study of liver disease progression in 71 HCV/HIV coinfected children and 71 age- and sex-matched HCV-monoinfected children. The coinfected children are being followed in CORISPES (the Spanish Cohort of HIV-infected Children), where they receive state-of-the-art care.

All was quiet through age 9 years, with no progression to liver fibrosis in either patient group. Among patients followed to age 20 years, however, 9 (24%) of 38 HCV/HIV-coinfected patients showed progression to advanced fibrosis, compared with just 3 (6%) of 54 patients with HCV only.

Of HCV/HIV coinfected patients, 73% were infected with the hard to treat viral genotypes 1 or 4, compared with 93% of patients with HCV-only.

In the study group, 22 patients with HCV/HIV and 52 patients with HCV-only underwent treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. At the time of treatment, three coinfected patients already had cirrhosis, another eight had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and half had no or mild fibrosis. In contrast, only one patient with HCV monoinfection had cirrhosis, four had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and the rest – nearly 90% of the total group – had no or mild fibrosis.

At treatment initiation, 96% of the HCV/HIV group were on antiretroviral therapy, 86% showed suppression of HIV RNA, 44% had AIDS, and 32% had a CD4 count below 500 cells/mm3.

The sustained viral response rate was similar in the two groups of patients – 41% in the HCV/HIV group and 42% in HCV-only patients – despite the fact that the HCV monoinfected patients had a higher prevalence of the tough to treat genotypes.

Roughly 12 million people worldwide are coinfected with HCV and HIV.

Dr. McPhee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MADRID – Roughly one in four children with vertically transmitted hepatitis C virus (HCV)/HIV coinfection will progress to advanced hepatic fibrosis by age 20 years despite treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, Carolina Fernández McPhee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This rate was nearly five times higher than in matched children with vertically acquired HCV monoinfection in a multicenter retrospective study, according to Dr. McPhee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid.

She presented a multicenter retrospective study of liver disease progression in 71 HCV/HIV coinfected children and 71 age- and sex-matched HCV-monoinfected children. The coinfected children are being followed in CORISPES (the Spanish Cohort of HIV-infected Children), where they receive state-of-the-art care.

All was quiet through age 9 years, with no progression to liver fibrosis in either patient group. Among patients followed to age 20 years, however, 9 (24%) of 38 HCV/HIV-coinfected patients showed progression to advanced fibrosis, compared with just 3 (6%) of 54 patients with HCV only.

Of HCV/HIV coinfected patients, 73% were infected with the hard to treat viral genotypes 1 or 4, compared with 93% of patients with HCV-only.

In the study group, 22 patients with HCV/HIV and 52 patients with HCV-only underwent treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. At the time of treatment, three coinfected patients already had cirrhosis, another eight had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and half had no or mild fibrosis. In contrast, only one patient with HCV monoinfection had cirrhosis, four had moderate to advanced fibrosis, and the rest – nearly 90% of the total group – had no or mild fibrosis.

At treatment initiation, 96% of the HCV/HIV group were on antiretroviral therapy, 86% showed suppression of HIV RNA, 44% had AIDS, and 32% had a CD4 count below 500 cells/mm3.

The sustained viral response rate was similar in the two groups of patients – 41% in the HCV/HIV group and 42% in HCV-only patients – despite the fact that the HCV monoinfected patients had a higher prevalence of the tough to treat genotypes.

Roughly 12 million people worldwide are coinfected with HCV and HIV.

Dr. McPhee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ESPID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: By age 20 years, 24% of a group of patients with vertically transmitted HCV/HIV coinfection had progressed to advanced hepatic fibrosis, compared with 6% of patients with vertically transmitted HCV monoinfection.

Data source: This retrospective, multicenter, observational Spanish study included 71 children with vertically transmitted HCV/HIV coinfection and 71 with vertically transmitted HCV monoinfection.

Disclosures: Dr. McPhee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Few states fully back HCV prevention, treatment

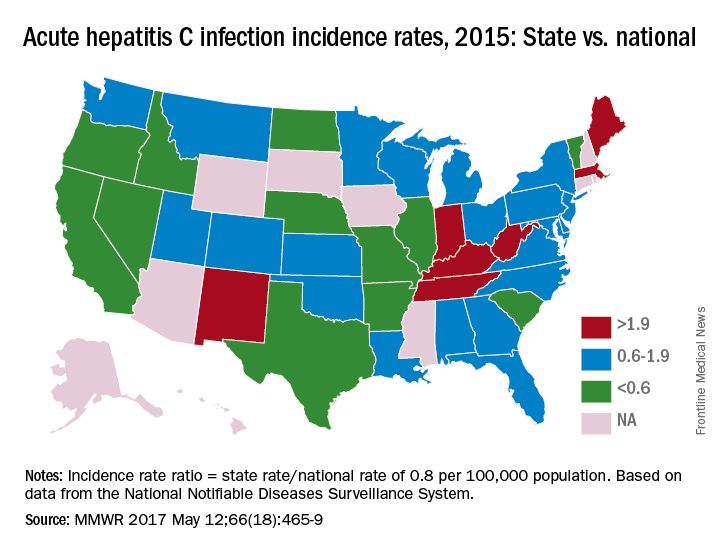

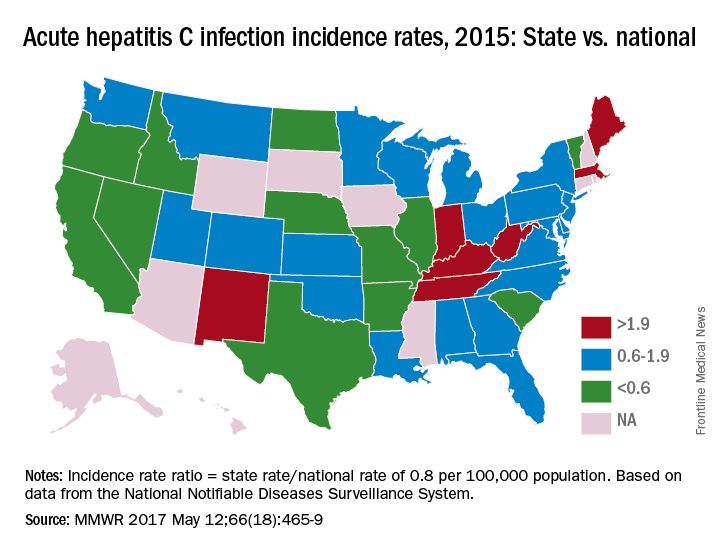

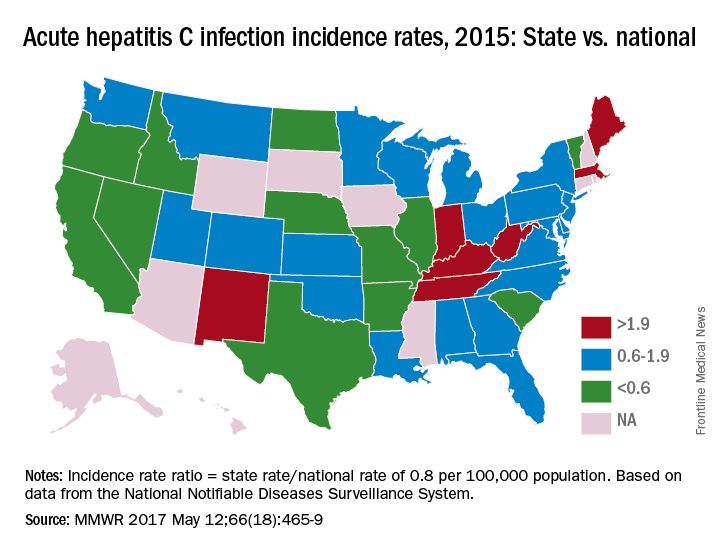

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

FROM MMWR

HCV incidence in young women doubled from 2006 to 2014

The incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in reproductive-age women has doubled between 2006 and 2014 while the number of acute cases increased more than threefold, according to data published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) from 2006 to 2014 and the Quest Diagnostics Health Trends national database from 2011 to 2014, finding 425,322 women with confirmed HCV infection, 40.4% of whom were aged 15 to 44 years.

Around half of all acute infections were in non-Hispanic white women, and of the 2,069 women with available risk information, 63% acknowledged injection drug use (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M16-2350).

The analysis also found 1,859 cases of hepatitis C infection in children aged 2-13 years. According to the Quest data, the proportion of children with current hepatitis C infection was 3.2-fold higher in children aged 2-3 years than in those aged 12-13 years.

Commenting on this age difference, Kathleen N. Ly, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors noted that it may have been the result of decreased testing over time in children already known to have chronic hepatitis C infection, or could be caused by spontaneous remission of infection, which is more common in infants and children than in adults.

The rate of infection among pregnant women tested for hepatitis C virus between 2011 and 2014 was 0.73%, which the authors calculated would mean that overall, 29,000 women with hepatitis C virus infection gave birth during that period across the United States. Based on data from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which found a likely mother-to-child transmission rate of 5.8/100 live births, they estimated that 1,700 infants were born with hepatitis C infection during that period.

“In contrast, only about 200 childhood cases per year are reported to the NNDSS, which may suggest a need for wider screening for HCV in pregnant women and their infants, as is recommended for HIV and hepatitis B virus,” the authors wrote. “However, recommendations for screening in pregnant women and clearer testing guidelines for infants born to HCV-infected mothers do not exist at this time.”

The study was supported by the CDC. One author was an employee of Quest Diagnostics, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Recognizing hepatitis C infection in pregnant women and neonates is possible, and clinical trials of antiviral therapy may show safety and efficacy in pregnant women and in children. Rather than silence, HCV infection calls out for public health action directed at all aspects of the epidemic, including consideration of screening pregnant women. At the very least, screening of pregnant women for HCV infection risk factors, as well as risk-based testing, requires more emphasis. Another issue in need of attention is the lack of authoritative, consensus-based recommendations for the identification, testing, and case management of newborns of infected mothers.

Much work lies ahead to eradicate HCV, starting with resources for public health surveillance to monitor incidence and prevalence and to fully characterize the infection in the population. Strategies to effectively prevent or cure infection in reproductive-aged women and their sexual and needle-sharing partners are critical.

Alfred DeMaria Jr., MD, is from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M17-0927). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Recognizing hepatitis C infection in pregnant women and neonates is possible, and clinical trials of antiviral therapy may show safety and efficacy in pregnant women and in children. Rather than silence, HCV infection calls out for public health action directed at all aspects of the epidemic, including consideration of screening pregnant women. At the very least, screening of pregnant women for HCV infection risk factors, as well as risk-based testing, requires more emphasis. Another issue in need of attention is the lack of authoritative, consensus-based recommendations for the identification, testing, and case management of newborns of infected mothers.

Much work lies ahead to eradicate HCV, starting with resources for public health surveillance to monitor incidence and prevalence and to fully characterize the infection in the population. Strategies to effectively prevent or cure infection in reproductive-aged women and their sexual and needle-sharing partners are critical.

Alfred DeMaria Jr., MD, is from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M17-0927). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Recognizing hepatitis C infection in pregnant women and neonates is possible, and clinical trials of antiviral therapy may show safety and efficacy in pregnant women and in children. Rather than silence, HCV infection calls out for public health action directed at all aspects of the epidemic, including consideration of screening pregnant women. At the very least, screening of pregnant women for HCV infection risk factors, as well as risk-based testing, requires more emphasis. Another issue in need of attention is the lack of authoritative, consensus-based recommendations for the identification, testing, and case management of newborns of infected mothers.

Much work lies ahead to eradicate HCV, starting with resources for public health surveillance to monitor incidence and prevalence and to fully characterize the infection in the population. Strategies to effectively prevent or cure infection in reproductive-aged women and their sexual and needle-sharing partners are critical.

Alfred DeMaria Jr., MD, is from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M17-0927). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in reproductive-age women has doubled between 2006 and 2014 while the number of acute cases increased more than threefold, according to data published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) from 2006 to 2014 and the Quest Diagnostics Health Trends national database from 2011 to 2014, finding 425,322 women with confirmed HCV infection, 40.4% of whom were aged 15 to 44 years.

Around half of all acute infections were in non-Hispanic white women, and of the 2,069 women with available risk information, 63% acknowledged injection drug use (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M16-2350).

The analysis also found 1,859 cases of hepatitis C infection in children aged 2-13 years. According to the Quest data, the proportion of children with current hepatitis C infection was 3.2-fold higher in children aged 2-3 years than in those aged 12-13 years.

Commenting on this age difference, Kathleen N. Ly, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors noted that it may have been the result of decreased testing over time in children already known to have chronic hepatitis C infection, or could be caused by spontaneous remission of infection, which is more common in infants and children than in adults.

The rate of infection among pregnant women tested for hepatitis C virus between 2011 and 2014 was 0.73%, which the authors calculated would mean that overall, 29,000 women with hepatitis C virus infection gave birth during that period across the United States. Based on data from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which found a likely mother-to-child transmission rate of 5.8/100 live births, they estimated that 1,700 infants were born with hepatitis C infection during that period.

“In contrast, only about 200 childhood cases per year are reported to the NNDSS, which may suggest a need for wider screening for HCV in pregnant women and their infants, as is recommended for HIV and hepatitis B virus,” the authors wrote. “However, recommendations for screening in pregnant women and clearer testing guidelines for infants born to HCV-infected mothers do not exist at this time.”

The study was supported by the CDC. One author was an employee of Quest Diagnostics, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

The incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in reproductive-age women has doubled between 2006 and 2014 while the number of acute cases increased more than threefold, according to data published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) from 2006 to 2014 and the Quest Diagnostics Health Trends national database from 2011 to 2014, finding 425,322 women with confirmed HCV infection, 40.4% of whom were aged 15 to 44 years.

Around half of all acute infections were in non-Hispanic white women, and of the 2,069 women with available risk information, 63% acknowledged injection drug use (Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 8. doi:10.7326/M16-2350).

The analysis also found 1,859 cases of hepatitis C infection in children aged 2-13 years. According to the Quest data, the proportion of children with current hepatitis C infection was 3.2-fold higher in children aged 2-3 years than in those aged 12-13 years.

Commenting on this age difference, Kathleen N. Ly, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her coauthors noted that it may have been the result of decreased testing over time in children already known to have chronic hepatitis C infection, or could be caused by spontaneous remission of infection, which is more common in infants and children than in adults.

The rate of infection among pregnant women tested for hepatitis C virus between 2011 and 2014 was 0.73%, which the authors calculated would mean that overall, 29,000 women with hepatitis C virus infection gave birth during that period across the United States. Based on data from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which found a likely mother-to-child transmission rate of 5.8/100 live births, they estimated that 1,700 infants were born with hepatitis C infection during that period.

“In contrast, only about 200 childhood cases per year are reported to the NNDSS, which may suggest a need for wider screening for HCV in pregnant women and their infants, as is recommended for HIV and hepatitis B virus,” the authors wrote. “However, recommendations for screening in pregnant women and clearer testing guidelines for infants born to HCV-infected mothers do not exist at this time.”

The study was supported by the CDC. One author was an employee of Quest Diagnostics, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The incidence of hepatitis C infection increased significantly in reproductive age women during 2006-2014.

Major finding: The incidence of hepatitis C infection in reproductive-age women doubled during 2006-2014 while the number of acute cases increased more than threefold.

Data source: Analysis of data from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System from 2006 to 2014 and the Quest Diagnostics Health Trends national database from 2011 to 2014.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One author was an employee of Quest Diagnostics, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

HCV treatment program achieves 97% SVR among homeless

A community-based primary care treatment program achieved a 97% sustained virologic response rate at 12 weeks among homeless adults with hepatitis C, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

An estimated 44% of homeless adults have hepatitis C and face many barriers to effective treatment. Investigators described their experience with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless program during an 18-month period in which 64 such patients received oral direct-acting antivirals as part of integrated primary care services. Most were men, and the mean age was 55 years, said Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of the division of infectious diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

Patients were selected for the therapy by clinicians – primary care physicians and nurse practitioners – based in part on their adherence to previous medical appointments. They received weekly phone calls from a care coordinator, and they were not required to maintain sobriety to remain eligible for Medicare or Medicaid coverage for the treatment.

Among the study participants, 62 of 64 (97%) achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks. Only 13% reported missing more than three doses of oral antivirals. Viral testing showed genetic mutations conferring resistance to treatment in one of the two patients who did not achieve SVR, the investigators said (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0358).

“These findings demonstrate that with a dedicated program for treating HCV in homeless and marginally housed adults in a primary care setting, it is possible to achieve outcomes similar to those of clinical trials and other cohorts, despite significant additional barriers and competing priorities to health care faced by this population,” Dr. Barocas and his associates said.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the study. Dr. Barocas and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

A community-based primary care treatment program achieved a 97% sustained virologic response rate at 12 weeks among homeless adults with hepatitis C, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

An estimated 44% of homeless adults have hepatitis C and face many barriers to effective treatment. Investigators described their experience with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless program during an 18-month period in which 64 such patients received oral direct-acting antivirals as part of integrated primary care services. Most were men, and the mean age was 55 years, said Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of the division of infectious diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

Patients were selected for the therapy by clinicians – primary care physicians and nurse practitioners – based in part on their adherence to previous medical appointments. They received weekly phone calls from a care coordinator, and they were not required to maintain sobriety to remain eligible for Medicare or Medicaid coverage for the treatment.

Among the study participants, 62 of 64 (97%) achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks. Only 13% reported missing more than three doses of oral antivirals. Viral testing showed genetic mutations conferring resistance to treatment in one of the two patients who did not achieve SVR, the investigators said (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0358).

“These findings demonstrate that with a dedicated program for treating HCV in homeless and marginally housed adults in a primary care setting, it is possible to achieve outcomes similar to those of clinical trials and other cohorts, despite significant additional barriers and competing priorities to health care faced by this population,” Dr. Barocas and his associates said.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the study. Dr. Barocas and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

A community-based primary care treatment program achieved a 97% sustained virologic response rate at 12 weeks among homeless adults with hepatitis C, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

An estimated 44% of homeless adults have hepatitis C and face many barriers to effective treatment. Investigators described their experience with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless program during an 18-month period in which 64 such patients received oral direct-acting antivirals as part of integrated primary care services. Most were men, and the mean age was 55 years, said Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of the division of infectious diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

Patients were selected for the therapy by clinicians – primary care physicians and nurse practitioners – based in part on their adherence to previous medical appointments. They received weekly phone calls from a care coordinator, and they were not required to maintain sobriety to remain eligible for Medicare or Medicaid coverage for the treatment.