User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

What do you call a general medicine hospitalist who focuses on comanaging with a single medical subspecialty?

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

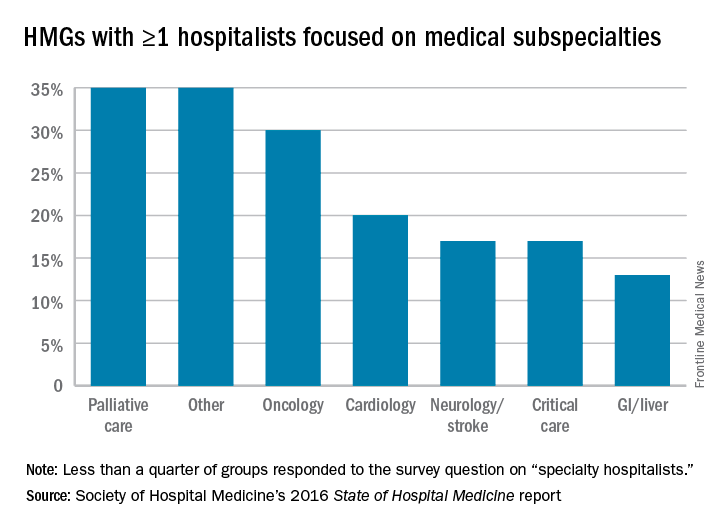

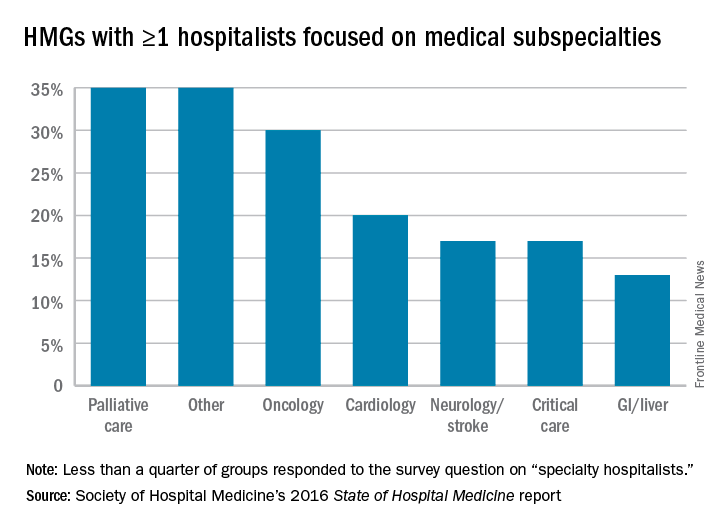

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

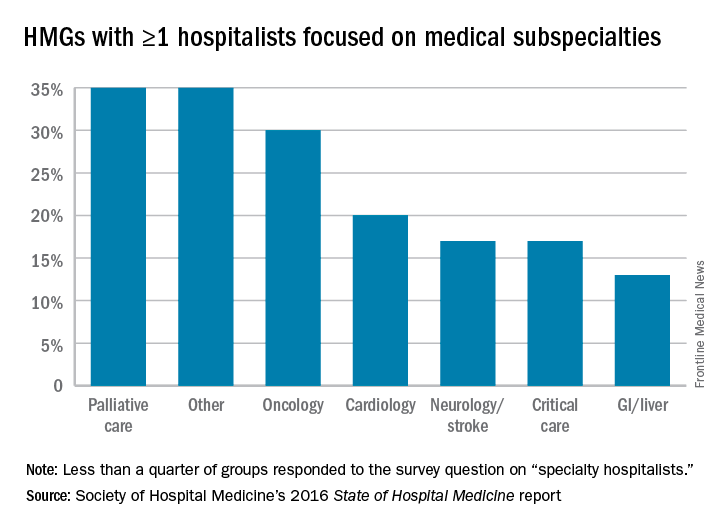

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

HM17’s ‘must-see sessions’

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Fellows and Awards of Excellence

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Adapting to change: Dr. Robert Wachter

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Networking: A skill worth learning

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Everything We Say and Do: Discussing advance care planning

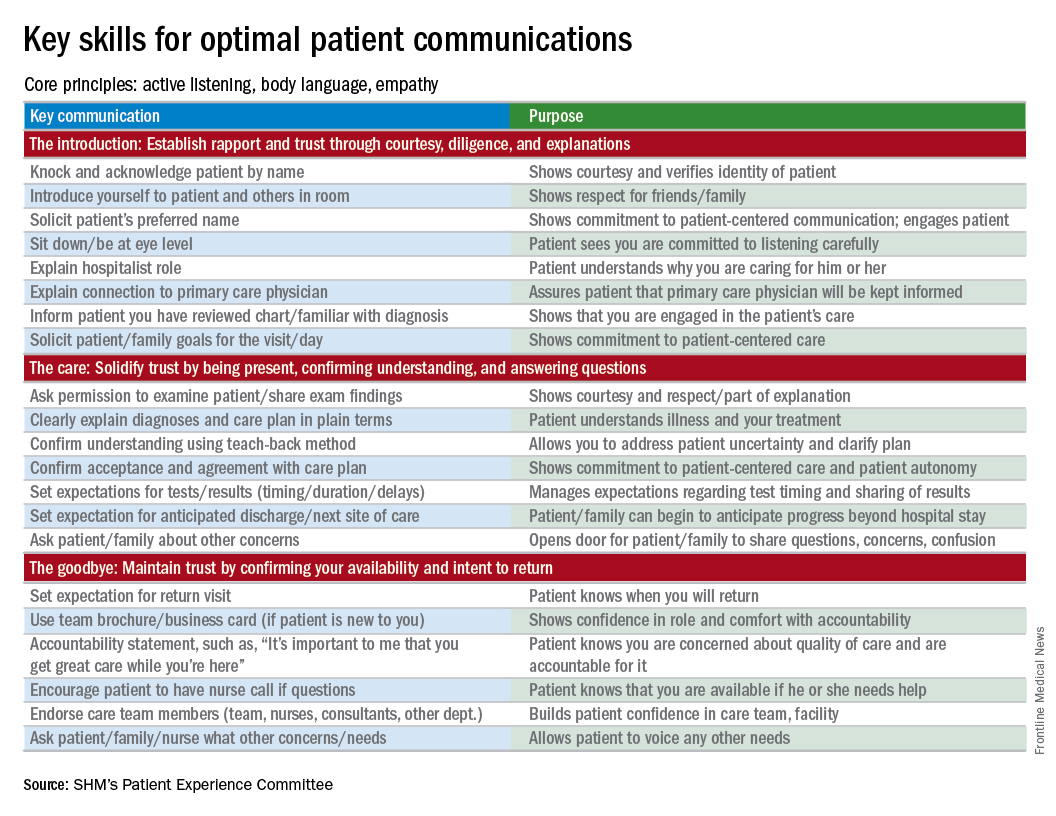

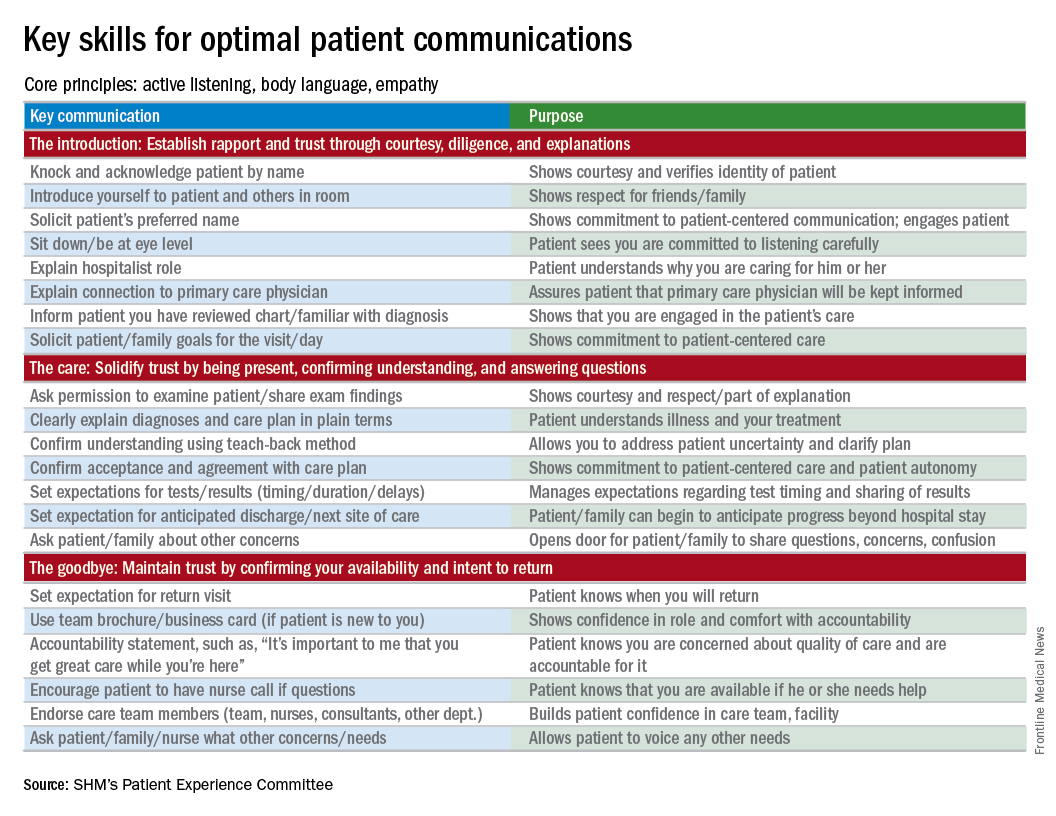

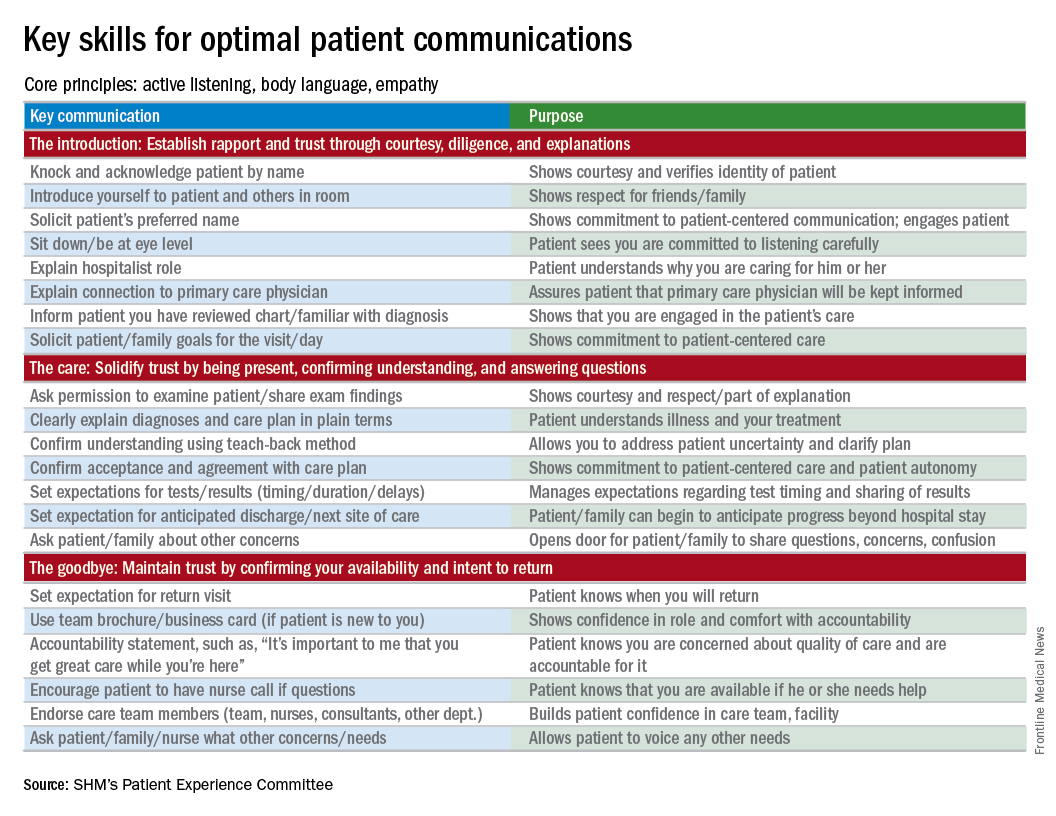

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

QI enthusiast turns QI leader

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.