User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Nonischemic cardiomyopathy does not benefit from prophylactic ICDs

Clinical question: Do prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) reduce long-term mortality in patients with symptomatic nonischemic systolic heart failure (NISHF)?

Study design: Multicenter, nonblinded, randomized controlled prospective trial.

Setting: Danish ICD centers.

Synopsis: A total of 1,116 patients with symptomatic NISHF (left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35%) were randomized to either receive an ICD or usual clinical care. The primary outcome, death from any cause, occurred in 120 patients (21.6%) in the ICD group (4.4 events/100 person-years) and in 131 patients (23.4%) in the control group. The hazard ratio for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI , 0.68-1.12; P = .28). The HR for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.68-1.12; P = .28)

Bottom line: Prophylactic ICD implantation in patients with symptomatic NISHF does not reduce long-term mortality.

Citation: Kober L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221-1230.

Clinical question: Do prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) reduce long-term mortality in patients with symptomatic nonischemic systolic heart failure (NISHF)?

Study design: Multicenter, nonblinded, randomized controlled prospective trial.

Setting: Danish ICD centers.

Synopsis: A total of 1,116 patients with symptomatic NISHF (left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35%) were randomized to either receive an ICD or usual clinical care. The primary outcome, death from any cause, occurred in 120 patients (21.6%) in the ICD group (4.4 events/100 person-years) and in 131 patients (23.4%) in the control group. The hazard ratio for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI , 0.68-1.12; P = .28). The HR for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.68-1.12; P = .28)

Bottom line: Prophylactic ICD implantation in patients with symptomatic NISHF does not reduce long-term mortality.

Citation: Kober L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221-1230.

Clinical question: Do prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) reduce long-term mortality in patients with symptomatic nonischemic systolic heart failure (NISHF)?

Study design: Multicenter, nonblinded, randomized controlled prospective trial.

Setting: Danish ICD centers.

Synopsis: A total of 1,116 patients with symptomatic NISHF (left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35%) were randomized to either receive an ICD or usual clinical care. The primary outcome, death from any cause, occurred in 120 patients (21.6%) in the ICD group (4.4 events/100 person-years) and in 131 patients (23.4%) in the control group. The hazard ratio for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI , 0.68-1.12; P = .28). The HR for death from any cause in the ICD group, as compared with the control group, was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.68-1.12; P = .28)

Bottom line: Prophylactic ICD implantation in patients with symptomatic NISHF does not reduce long-term mortality.

Citation: Kober L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221-1230.

Bundled payments reduce costs in joint patients

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Pleth Variability Index shows promise for asthma assessments

Clinical question: Does pulse variability on plethysmography, or the Pleth Variability Index (PVI), correlate with disease severity in obstructive airway disease in children?

Background: Asthma is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United S. for children 3-12 years old. Asthma accounts for a quarter of ED visits for children aged 1-9 years old.1 Although systems have been developed to assess asthma exacerbation severity and the need for hospitalization, many of these depend on reassessments over time or have been proven to be invalid in larger studies.2,3,4 Pulsus paradoxus (PP), which is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg, correlates with the severity of obstruction in asthma exacerbations, but it is not practical in the children being evaluated in the ED or hospital.5,6 PP measurement using plethysmography has been found to correlate with measurement by sphygmomanometry.7 Furthermore, PVI, which is derived from amplitude variability in the pulse oximeter waveform, has been found to correlate with fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients. To this date, no study has assessed the correlation between PVI and exacerbation severity in asthma.

Setting: A 137-bed, tertiary-care children’s hospital.

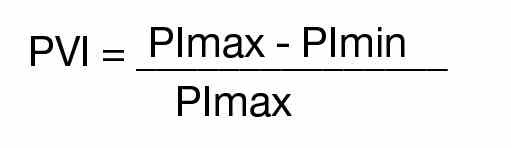

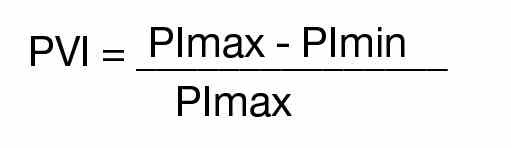

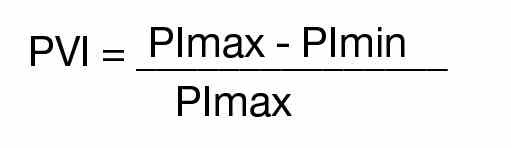

Synopsis: Over a 6-month period on weekdays, researchers enrolled patients aged 1-18 years evaluated in the ED for asthma exacerbations or reactive airway disease. ED staff diagnosed patients clinically, and other patients with conditions known to affect PP – such as dehydration, croup, and cardiac disease – were excluded. PVI was calculated by measuring the minimum perfusion index (PImin) and the maximum perfusion index (PImax) using the following formula:

A printout of the first ED pulse oximetry reading was used to obtain the PImax and PImin as below:

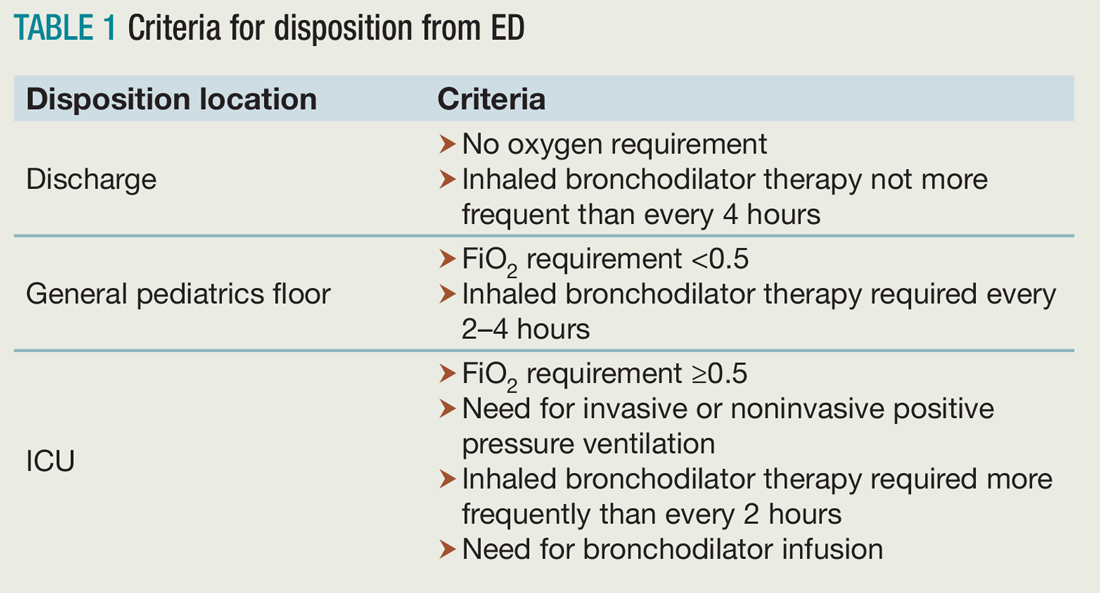

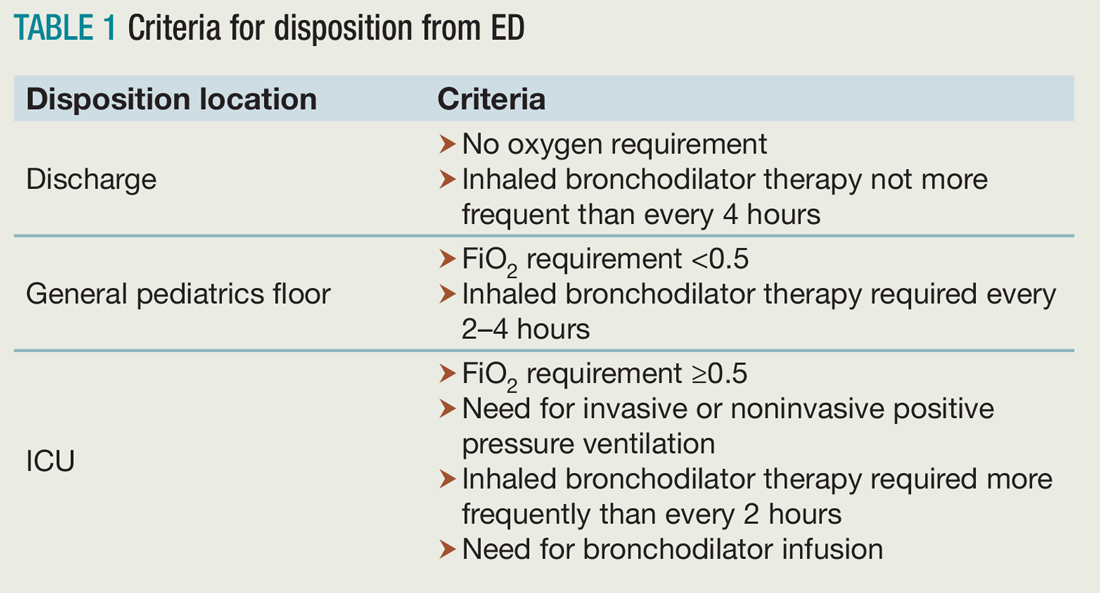

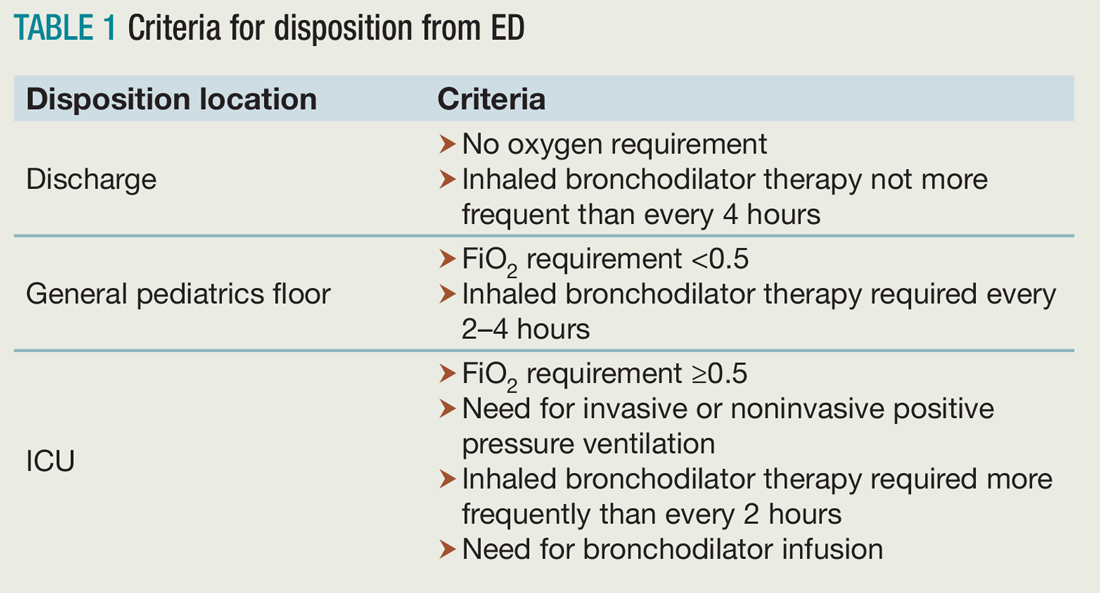

Researchers followed patients after the initial evaluation to determine disposition from the ED, which included either discharge to home, admission to a general pediatrics floor, or admission to the PICU. The hospital utilized specific criteria for disposition from the ED (see Table 1).

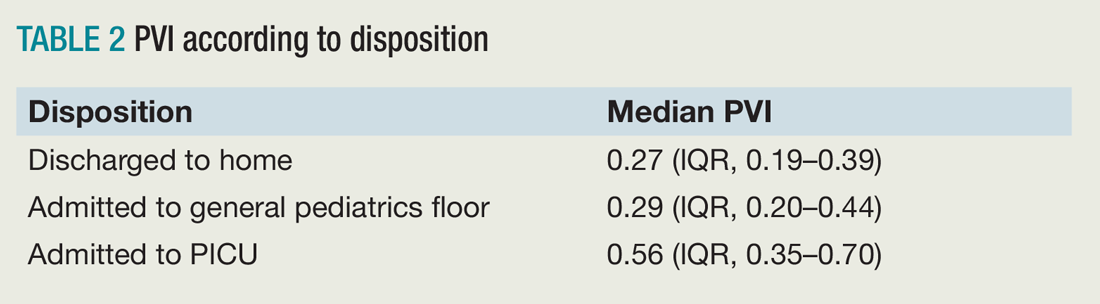

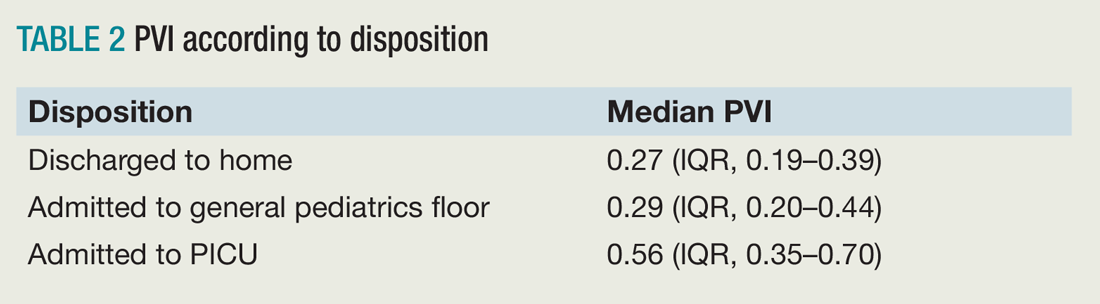

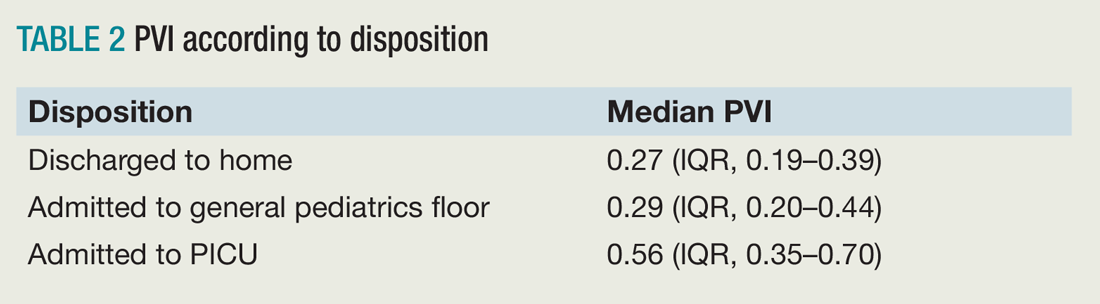

Of the 117 patients who were analyzed after application of exclusion criteria, 48 were discharged to home, 61 were admitted to a general pediatrics floor, and eight were admitted to the PICU. The three groups were found to be demographically similar. Researchers found a significant difference between the PVI of the three groups, but pairwise analysis showed no significant difference between the PVI of patients admitted to the general pediatrics floor versus discharged to home (see Table 2).

Bottom line: PVI shows promise as a tool to rapidly assess disease severity in pediatric patients being evaluated and treated for asthma, but further studies are needed to validate this in the ED and hospital setting.

Citation: Brandwein A, Patel K, Kline M, Silver P, Gangadharan S. Using pleth variability as a triage tool for children with obstructive airway disease in a pediatric emergency department [published online ahead of print Oct. 6, 2016]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000887.

References

1. Care of children and adolescents in U.S. hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbk4/factbk4.htm. Accessed Nov. 18, 2016.

2. Kelly AM, Kerr D, Powell C. Is severity assessment after one hour of treatment better for predicting the need for admission in acute asthma? Respir Med. 2004;98(8):777-781.

3. Keogh KA, Macarthur C, Parkin PC, et al. Predictors of hospitalization in children with acute asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):273-277.

4. Keahey L, Bulloch B, Becker AB, et al. Initial oxygen saturation as a predictor of admission in children presenting to the emergency department with acute asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(3):300-307.

5. Guntheroth WG, Morgan BC, Mullins GL. Effect of respiration on venous return and stroke volume in cardiac tamponade. Mechanism of pulsus paradoxus. Circ Res. 1967;20(4):381-390.

6. Frey B, Freezer N. Diagnostic value and pathophysiologic basis of pulsus paradoxus in infants and children with respiratory disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31(2):138-143.

7. Clark JA, Lieh-Lai M, Thomas R, Raghavan K, Sarnaik AP. Comparison of traditional and plethysmographic methods for measuring pulsus paradoxus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(1):48-51.

Clinical question: Does pulse variability on plethysmography, or the Pleth Variability Index (PVI), correlate with disease severity in obstructive airway disease in children?

Background: Asthma is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United S. for children 3-12 years old. Asthma accounts for a quarter of ED visits for children aged 1-9 years old.1 Although systems have been developed to assess asthma exacerbation severity and the need for hospitalization, many of these depend on reassessments over time or have been proven to be invalid in larger studies.2,3,4 Pulsus paradoxus (PP), which is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg, correlates with the severity of obstruction in asthma exacerbations, but it is not practical in the children being evaluated in the ED or hospital.5,6 PP measurement using plethysmography has been found to correlate with measurement by sphygmomanometry.7 Furthermore, PVI, which is derived from amplitude variability in the pulse oximeter waveform, has been found to correlate with fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients. To this date, no study has assessed the correlation between PVI and exacerbation severity in asthma.

Setting: A 137-bed, tertiary-care children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Over a 6-month period on weekdays, researchers enrolled patients aged 1-18 years evaluated in the ED for asthma exacerbations or reactive airway disease. ED staff diagnosed patients clinically, and other patients with conditions known to affect PP – such as dehydration, croup, and cardiac disease – were excluded. PVI was calculated by measuring the minimum perfusion index (PImin) and the maximum perfusion index (PImax) using the following formula:

A printout of the first ED pulse oximetry reading was used to obtain the PImax and PImin as below:

Researchers followed patients after the initial evaluation to determine disposition from the ED, which included either discharge to home, admission to a general pediatrics floor, or admission to the PICU. The hospital utilized specific criteria for disposition from the ED (see Table 1).

Of the 117 patients who were analyzed after application of exclusion criteria, 48 were discharged to home, 61 were admitted to a general pediatrics floor, and eight were admitted to the PICU. The three groups were found to be demographically similar. Researchers found a significant difference between the PVI of the three groups, but pairwise analysis showed no significant difference between the PVI of patients admitted to the general pediatrics floor versus discharged to home (see Table 2).

Bottom line: PVI shows promise as a tool to rapidly assess disease severity in pediatric patients being evaluated and treated for asthma, but further studies are needed to validate this in the ED and hospital setting.

Citation: Brandwein A, Patel K, Kline M, Silver P, Gangadharan S. Using pleth variability as a triage tool for children with obstructive airway disease in a pediatric emergency department [published online ahead of print Oct. 6, 2016]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000887.

References

1. Care of children and adolescents in U.S. hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbk4/factbk4.htm. Accessed Nov. 18, 2016.

2. Kelly AM, Kerr D, Powell C. Is severity assessment after one hour of treatment better for predicting the need for admission in acute asthma? Respir Med. 2004;98(8):777-781.

3. Keogh KA, Macarthur C, Parkin PC, et al. Predictors of hospitalization in children with acute asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):273-277.

4. Keahey L, Bulloch B, Becker AB, et al. Initial oxygen saturation as a predictor of admission in children presenting to the emergency department with acute asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(3):300-307.

5. Guntheroth WG, Morgan BC, Mullins GL. Effect of respiration on venous return and stroke volume in cardiac tamponade. Mechanism of pulsus paradoxus. Circ Res. 1967;20(4):381-390.

6. Frey B, Freezer N. Diagnostic value and pathophysiologic basis of pulsus paradoxus in infants and children with respiratory disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31(2):138-143.

7. Clark JA, Lieh-Lai M, Thomas R, Raghavan K, Sarnaik AP. Comparison of traditional and plethysmographic methods for measuring pulsus paradoxus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(1):48-51.

Clinical question: Does pulse variability on plethysmography, or the Pleth Variability Index (PVI), correlate with disease severity in obstructive airway disease in children?

Background: Asthma is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United S. for children 3-12 years old. Asthma accounts for a quarter of ED visits for children aged 1-9 years old.1 Although systems have been developed to assess asthma exacerbation severity and the need for hospitalization, many of these depend on reassessments over time or have been proven to be invalid in larger studies.2,3,4 Pulsus paradoxus (PP), which is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg, correlates with the severity of obstruction in asthma exacerbations, but it is not practical in the children being evaluated in the ED or hospital.5,6 PP measurement using plethysmography has been found to correlate with measurement by sphygmomanometry.7 Furthermore, PVI, which is derived from amplitude variability in the pulse oximeter waveform, has been found to correlate with fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients. To this date, no study has assessed the correlation between PVI and exacerbation severity in asthma.

Setting: A 137-bed, tertiary-care children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Over a 6-month period on weekdays, researchers enrolled patients aged 1-18 years evaluated in the ED for asthma exacerbations or reactive airway disease. ED staff diagnosed patients clinically, and other patients with conditions known to affect PP – such as dehydration, croup, and cardiac disease – were excluded. PVI was calculated by measuring the minimum perfusion index (PImin) and the maximum perfusion index (PImax) using the following formula:

A printout of the first ED pulse oximetry reading was used to obtain the PImax and PImin as below:

Researchers followed patients after the initial evaluation to determine disposition from the ED, which included either discharge to home, admission to a general pediatrics floor, or admission to the PICU. The hospital utilized specific criteria for disposition from the ED (see Table 1).

Of the 117 patients who were analyzed after application of exclusion criteria, 48 were discharged to home, 61 were admitted to a general pediatrics floor, and eight were admitted to the PICU. The three groups were found to be demographically similar. Researchers found a significant difference between the PVI of the three groups, but pairwise analysis showed no significant difference between the PVI of patients admitted to the general pediatrics floor versus discharged to home (see Table 2).

Bottom line: PVI shows promise as a tool to rapidly assess disease severity in pediatric patients being evaluated and treated for asthma, but further studies are needed to validate this in the ED and hospital setting.

Citation: Brandwein A, Patel K, Kline M, Silver P, Gangadharan S. Using pleth variability as a triage tool for children with obstructive airway disease in a pediatric emergency department [published online ahead of print Oct. 6, 2016]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000887.

References

1. Care of children and adolescents in U.S. hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbk4/factbk4.htm. Accessed Nov. 18, 2016.

2. Kelly AM, Kerr D, Powell C. Is severity assessment after one hour of treatment better for predicting the need for admission in acute asthma? Respir Med. 2004;98(8):777-781.

3. Keogh KA, Macarthur C, Parkin PC, et al. Predictors of hospitalization in children with acute asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):273-277.

4. Keahey L, Bulloch B, Becker AB, et al. Initial oxygen saturation as a predictor of admission in children presenting to the emergency department with acute asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(3):300-307.

5. Guntheroth WG, Morgan BC, Mullins GL. Effect of respiration on venous return and stroke volume in cardiac tamponade. Mechanism of pulsus paradoxus. Circ Res. 1967;20(4):381-390.

6. Frey B, Freezer N. Diagnostic value and pathophysiologic basis of pulsus paradoxus in infants and children with respiratory disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31(2):138-143.

7. Clark JA, Lieh-Lai M, Thomas R, Raghavan K, Sarnaik AP. Comparison of traditional and plethysmographic methods for measuring pulsus paradoxus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(1):48-51.

Embrace change as a hospitalist leader

We work in complex environments and in a flawed and rapidly changing health care system. Caregivers, patients, and communities will be led through this complexity by those who embrace change. Last October, I had the privilege of attending and facilitating the SHM Leadership Academy in Orlando, which allowed me the opportunity to meet a group of people who embrace change, including the benefits and challenges that often accompany it.

SHM board member Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, taught one of the first lessons at Leadership Academy, focusing on the importance of meaningful, difficult change. With comparisons to companies that have embraced change, like Apple, and some that have not, like Sears, Jeff summed up how complacency with “good” and a reluctance to tackle the difficulty of change keeps organizations – and people – from becoming great.

“Good is the enemy of great,” Jeff preached.

He largely focused on hospitalists leading organizational change, but the concepts can apply to personal change, too. He explained that “people generally want things to be different, but they don’t want to change.”

Leaders in training

Ten emerging hospitalist leaders sat at my table, soaking in the message. Several of them, like me 8 years ago, had the responsibilities of leadership unexpectedly thrust upon them. Some carried with them the heavy expectations of their colleagues or hospital administration (or both) that by being elevated into a role such as medical director, they would abruptly be able to make improvements in patient care and hospital operations. They had accepted the challenge to change – to move out of purely clinical roles and take on new ones in leadership despite having little or no experience. Doing so, they gingerly but willingly were following in the footsteps of leaders before them, growing their skills, improving their hospitals, and laying a path for future leaders to follow.

A few weeks prior, I had taken a new leadership position myself. The Cleveland Clinic recently acquired a hospital and health system in Akron, Ohio, about 40 miles away from the city. I assumed the role of president of this acquisition, embracing the complex challenge of leading the process of integrating two health systems. After 3 years overseeing a different hospital in the health system, I finally felt I had developed the people, processes, and culture that I had been striving to build. But like the young leaders at Leadership Academy, I had the opportunity to change, grow, develop, take on new risk, and become a stronger leader in this new role. A significant part of the experience of the Leadership Academy involves table exercises. For the first few exercises, the group was quiet, uncertain, tentative. I was struck both by how early these individuals were in their development and by how so much of what is happening today in hospitals and health care is dependent upon the development and success of individuals like these who are enthusiastic and talented but young and overwhelmed.

I believe that successful hospitalists are, through experience, training, and nature, rapid assimilators into their environments. By the third day, the dynamic at my table had gone from tentative and uncertain to much more confident and assertive. To experience this transformation in person at SHM’s Leadership Academy, we welcome you to Scottsdale, Ariz., later this year. Learn more about the program at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

At Leadership Academy and beyond, I implore hospitalists to look for opportunities to change during this time of New Year’s resolutions and to take the opposite posture and want to change – change how we think, act, and respond; change our roles to take on new, uncomfortable responsibilities; and change how we view change itself.

We will be better for it both personally and professionally, and we will stand out as role models for our colleagues, coworkers, and hospitalists who follow in our footsteps.

Dr. Harte is a practicing hospitalist, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, and president of Hillcrest Hospital in Mayfield Heights, Ohio, part of the Cleveland Clinic Health System. He is associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, Lerner College of Medicine in Cleveland.

We work in complex environments and in a flawed and rapidly changing health care system. Caregivers, patients, and communities will be led through this complexity by those who embrace change. Last October, I had the privilege of attending and facilitating the SHM Leadership Academy in Orlando, which allowed me the opportunity to meet a group of people who embrace change, including the benefits and challenges that often accompany it.

SHM board member Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, taught one of the first lessons at Leadership Academy, focusing on the importance of meaningful, difficult change. With comparisons to companies that have embraced change, like Apple, and some that have not, like Sears, Jeff summed up how complacency with “good” and a reluctance to tackle the difficulty of change keeps organizations – and people – from becoming great.

“Good is the enemy of great,” Jeff preached.

He largely focused on hospitalists leading organizational change, but the concepts can apply to personal change, too. He explained that “people generally want things to be different, but they don’t want to change.”

Leaders in training

Ten emerging hospitalist leaders sat at my table, soaking in the message. Several of them, like me 8 years ago, had the responsibilities of leadership unexpectedly thrust upon them. Some carried with them the heavy expectations of their colleagues or hospital administration (or both) that by being elevated into a role such as medical director, they would abruptly be able to make improvements in patient care and hospital operations. They had accepted the challenge to change – to move out of purely clinical roles and take on new ones in leadership despite having little or no experience. Doing so, they gingerly but willingly were following in the footsteps of leaders before them, growing their skills, improving their hospitals, and laying a path for future leaders to follow.

A few weeks prior, I had taken a new leadership position myself. The Cleveland Clinic recently acquired a hospital and health system in Akron, Ohio, about 40 miles away from the city. I assumed the role of president of this acquisition, embracing the complex challenge of leading the process of integrating two health systems. After 3 years overseeing a different hospital in the health system, I finally felt I had developed the people, processes, and culture that I had been striving to build. But like the young leaders at Leadership Academy, I had the opportunity to change, grow, develop, take on new risk, and become a stronger leader in this new role. A significant part of the experience of the Leadership Academy involves table exercises. For the first few exercises, the group was quiet, uncertain, tentative. I was struck both by how early these individuals were in their development and by how so much of what is happening today in hospitals and health care is dependent upon the development and success of individuals like these who are enthusiastic and talented but young and overwhelmed.

I believe that successful hospitalists are, through experience, training, and nature, rapid assimilators into their environments. By the third day, the dynamic at my table had gone from tentative and uncertain to much more confident and assertive. To experience this transformation in person at SHM’s Leadership Academy, we welcome you to Scottsdale, Ariz., later this year. Learn more about the program at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

At Leadership Academy and beyond, I implore hospitalists to look for opportunities to change during this time of New Year’s resolutions and to take the opposite posture and want to change – change how we think, act, and respond; change our roles to take on new, uncomfortable responsibilities; and change how we view change itself.

We will be better for it both personally and professionally, and we will stand out as role models for our colleagues, coworkers, and hospitalists who follow in our footsteps.

Dr. Harte is a practicing hospitalist, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, and president of Hillcrest Hospital in Mayfield Heights, Ohio, part of the Cleveland Clinic Health System. He is associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, Lerner College of Medicine in Cleveland.

We work in complex environments and in a flawed and rapidly changing health care system. Caregivers, patients, and communities will be led through this complexity by those who embrace change. Last October, I had the privilege of attending and facilitating the SHM Leadership Academy in Orlando, which allowed me the opportunity to meet a group of people who embrace change, including the benefits and challenges that often accompany it.

SHM board member Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, taught one of the first lessons at Leadership Academy, focusing on the importance of meaningful, difficult change. With comparisons to companies that have embraced change, like Apple, and some that have not, like Sears, Jeff summed up how complacency with “good” and a reluctance to tackle the difficulty of change keeps organizations – and people – from becoming great.

“Good is the enemy of great,” Jeff preached.

He largely focused on hospitalists leading organizational change, but the concepts can apply to personal change, too. He explained that “people generally want things to be different, but they don’t want to change.”

Leaders in training

Ten emerging hospitalist leaders sat at my table, soaking in the message. Several of them, like me 8 years ago, had the responsibilities of leadership unexpectedly thrust upon them. Some carried with them the heavy expectations of their colleagues or hospital administration (or both) that by being elevated into a role such as medical director, they would abruptly be able to make improvements in patient care and hospital operations. They had accepted the challenge to change – to move out of purely clinical roles and take on new ones in leadership despite having little or no experience. Doing so, they gingerly but willingly were following in the footsteps of leaders before them, growing their skills, improving their hospitals, and laying a path for future leaders to follow.

A few weeks prior, I had taken a new leadership position myself. The Cleveland Clinic recently acquired a hospital and health system in Akron, Ohio, about 40 miles away from the city. I assumed the role of president of this acquisition, embracing the complex challenge of leading the process of integrating two health systems. After 3 years overseeing a different hospital in the health system, I finally felt I had developed the people, processes, and culture that I had been striving to build. But like the young leaders at Leadership Academy, I had the opportunity to change, grow, develop, take on new risk, and become a stronger leader in this new role. A significant part of the experience of the Leadership Academy involves table exercises. For the first few exercises, the group was quiet, uncertain, tentative. I was struck both by how early these individuals were in their development and by how so much of what is happening today in hospitals and health care is dependent upon the development and success of individuals like these who are enthusiastic and talented but young and overwhelmed.

I believe that successful hospitalists are, through experience, training, and nature, rapid assimilators into their environments. By the third day, the dynamic at my table had gone from tentative and uncertain to much more confident and assertive. To experience this transformation in person at SHM’s Leadership Academy, we welcome you to Scottsdale, Ariz., later this year. Learn more about the program at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

At Leadership Academy and beyond, I implore hospitalists to look for opportunities to change during this time of New Year’s resolutions and to take the opposite posture and want to change – change how we think, act, and respond; change our roles to take on new, uncomfortable responsibilities; and change how we view change itself.

We will be better for it both personally and professionally, and we will stand out as role models for our colleagues, coworkers, and hospitalists who follow in our footsteps.

Dr. Harte is a practicing hospitalist, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, and president of Hillcrest Hospital in Mayfield Heights, Ohio, part of the Cleveland Clinic Health System. He is associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, Lerner College of Medicine in Cleveland.

Trending at SHM

Unveiling the hospitalist specialty code

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in November the official implementation date for the Medicare physician specialty code for hospitalists. On April 3, “hospitalist” will be an official specialty designation under Medicare; the code will be C6. Starting on that date, hospitalists can change their specialty designation on the Medicare enrollment application (Form CMS-855I) or through CMS’ online portal (Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System, or PECOS).

Appropriate use of specialty codes helps distinguish differences among providers and improves the quality of utilization data. SHM applied for a specialty code for hospitalists nearly 3 years ago, and CMS approved the application in February 2016.

Stand with your fellow hospitalists and make sure to declare, “I’m a C6.”

Develop curricula to educate, engage medical students and residents

The ACGME requirements for training in quality and safety are changing – it is no longer an elective. As sponsoring institutions’ residency and fellowship programs mobilize to meet these requirements, leaders may find few faculty members are comfortable enough with the material to teach and create educational content for trainees. These faculty need further development.

Sponsored by SHM, the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) responds to that demand by providing medical educators with the knowledge and tools to integrate quality improvement and safety concepts into their curricula. The 2017 meeting is Feb. 26-28 at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Arizona.

This 2½ day meeting aims to fill the current gaps for faculty by offering basic concepts and educational tools in quality improvement and patient safety. Material is presented in an interactive way, providing guidance on career and curriculum development and establishing a national network of quality and safety educators.

For more information and to register, visit www.shmqsea.org.

EHRs: blessing or curse?

SHM’s Health Information Technology (HIT) Committee invited you to participate in a brief survey to inform your experiences with inpatient electronic health record (EHR) systems. The results will serve as a foundation for a white paper to be written by the HIT Committee addressing hospitalists’ attitudes toward EHR systems. It will be released next month, so stay tuned then to view the final paper.

SHM chapters: Your connection to local education, networking, leadership opportunities

SHM offers various opportunities to grow professionally, expand your CV, and engage with other hospitalists. With more than 50 chapters across the country, you can network, learn, teach, and continue to improve patient care at a local level. Find a chapter in your area or start a chapter today by visiting www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapters.

Enhance opioid safety for inpatients

SHM enrolled 10 hospitals into a second mentored implementation cohort around Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids (RADEO). The program is now in its second month as the sites work with their mentors to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications by:

- Developing a needs assessment.

- Putting in place formal selections of data collection measures.

- Beginning to take outcomes and process data collection on intervention units.

- Starting to design and implement key interventions.

Even if you’re not in this mentored implementation cohort, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO and view the online toolkit or download the implementation guide.

Earn recognition for your research with SHM’s Junior Investigator Award

The SHM Junior Investigator Award was created for junior/early-stage investigators, defined as faculty in the first 5 years of their most recent position/appointment. Applicants must be a hospitalist or clinician-investigators whose research interests focus on the care of hospitalized patients, the organization of hospitals, or the practice of hospitalists. Applicants must be members of SHM in good standing. Nominations from mentors and self-nominations are both welcome.

The winner will be invited to receive the award during SHM’s annual meeting, HM17, May 1-4, at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. The winner will receive complimentary registration for this meeting as well as a complimentary 1-year membership to SHM.

For more information on the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/juniorinvestigator.

Unveiling the hospitalist specialty code

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in November the official implementation date for the Medicare physician specialty code for hospitalists. On April 3, “hospitalist” will be an official specialty designation under Medicare; the code will be C6. Starting on that date, hospitalists can change their specialty designation on the Medicare enrollment application (Form CMS-855I) or through CMS’ online portal (Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System, or PECOS).

Appropriate use of specialty codes helps distinguish differences among providers and improves the quality of utilization data. SHM applied for a specialty code for hospitalists nearly 3 years ago, and CMS approved the application in February 2016.

Stand with your fellow hospitalists and make sure to declare, “I’m a C6.”

Develop curricula to educate, engage medical students and residents

The ACGME requirements for training in quality and safety are changing – it is no longer an elective. As sponsoring institutions’ residency and fellowship programs mobilize to meet these requirements, leaders may find few faculty members are comfortable enough with the material to teach and create educational content for trainees. These faculty need further development.

Sponsored by SHM, the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) responds to that demand by providing medical educators with the knowledge and tools to integrate quality improvement and safety concepts into their curricula. The 2017 meeting is Feb. 26-28 at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Arizona.

This 2½ day meeting aims to fill the current gaps for faculty by offering basic concepts and educational tools in quality improvement and patient safety. Material is presented in an interactive way, providing guidance on career and curriculum development and establishing a national network of quality and safety educators.

For more information and to register, visit www.shmqsea.org.

EHRs: blessing or curse?

SHM’s Health Information Technology (HIT) Committee invited you to participate in a brief survey to inform your experiences with inpatient electronic health record (EHR) systems. The results will serve as a foundation for a white paper to be written by the HIT Committee addressing hospitalists’ attitudes toward EHR systems. It will be released next month, so stay tuned then to view the final paper.

SHM chapters: Your connection to local education, networking, leadership opportunities

SHM offers various opportunities to grow professionally, expand your CV, and engage with other hospitalists. With more than 50 chapters across the country, you can network, learn, teach, and continue to improve patient care at a local level. Find a chapter in your area or start a chapter today by visiting www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapters.

Enhance opioid safety for inpatients

SHM enrolled 10 hospitals into a second mentored implementation cohort around Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids (RADEO). The program is now in its second month as the sites work with their mentors to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications by:

- Developing a needs assessment.

- Putting in place formal selections of data collection measures.

- Beginning to take outcomes and process data collection on intervention units.

- Starting to design and implement key interventions.

Even if you’re not in this mentored implementation cohort, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO and view the online toolkit or download the implementation guide.

Earn recognition for your research with SHM’s Junior Investigator Award

The SHM Junior Investigator Award was created for junior/early-stage investigators, defined as faculty in the first 5 years of their most recent position/appointment. Applicants must be a hospitalist or clinician-investigators whose research interests focus on the care of hospitalized patients, the organization of hospitals, or the practice of hospitalists. Applicants must be members of SHM in good standing. Nominations from mentors and self-nominations are both welcome.

The winner will be invited to receive the award during SHM’s annual meeting, HM17, May 1-4, at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. The winner will receive complimentary registration for this meeting as well as a complimentary 1-year membership to SHM.

For more information on the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/juniorinvestigator.

Unveiling the hospitalist specialty code

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in November the official implementation date for the Medicare physician specialty code for hospitalists. On April 3, “hospitalist” will be an official specialty designation under Medicare; the code will be C6. Starting on that date, hospitalists can change their specialty designation on the Medicare enrollment application (Form CMS-855I) or through CMS’ online portal (Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System, or PECOS).

Appropriate use of specialty codes helps distinguish differences among providers and improves the quality of utilization data. SHM applied for a specialty code for hospitalists nearly 3 years ago, and CMS approved the application in February 2016.

Stand with your fellow hospitalists and make sure to declare, “I’m a C6.”

Develop curricula to educate, engage medical students and residents

The ACGME requirements for training in quality and safety are changing – it is no longer an elective. As sponsoring institutions’ residency and fellowship programs mobilize to meet these requirements, leaders may find few faculty members are comfortable enough with the material to teach and create educational content for trainees. These faculty need further development.

Sponsored by SHM, the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) responds to that demand by providing medical educators with the knowledge and tools to integrate quality improvement and safety concepts into their curricula. The 2017 meeting is Feb. 26-28 at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Arizona.

This 2½ day meeting aims to fill the current gaps for faculty by offering basic concepts and educational tools in quality improvement and patient safety. Material is presented in an interactive way, providing guidance on career and curriculum development and establishing a national network of quality and safety educators.

For more information and to register, visit www.shmqsea.org.

EHRs: blessing or curse?

SHM’s Health Information Technology (HIT) Committee invited you to participate in a brief survey to inform your experiences with inpatient electronic health record (EHR) systems. The results will serve as a foundation for a white paper to be written by the HIT Committee addressing hospitalists’ attitudes toward EHR systems. It will be released next month, so stay tuned then to view the final paper.

SHM chapters: Your connection to local education, networking, leadership opportunities

SHM offers various opportunities to grow professionally, expand your CV, and engage with other hospitalists. With more than 50 chapters across the country, you can network, learn, teach, and continue to improve patient care at a local level. Find a chapter in your area or start a chapter today by visiting www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapters.

Enhance opioid safety for inpatients

SHM enrolled 10 hospitals into a second mentored implementation cohort around Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids (RADEO). The program is now in its second month as the sites work with their mentors to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications by:

- Developing a needs assessment.

- Putting in place formal selections of data collection measures.

- Beginning to take outcomes and process data collection on intervention units.

- Starting to design and implement key interventions.

Even if you’re not in this mentored implementation cohort, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO and view the online toolkit or download the implementation guide.

Earn recognition for your research with SHM’s Junior Investigator Award

The SHM Junior Investigator Award was created for junior/early-stage investigators, defined as faculty in the first 5 years of their most recent position/appointment. Applicants must be a hospitalist or clinician-investigators whose research interests focus on the care of hospitalized patients, the organization of hospitals, or the practice of hospitalists. Applicants must be members of SHM in good standing. Nominations from mentors and self-nominations are both welcome.

The winner will be invited to receive the award during SHM’s annual meeting, HM17, May 1-4, at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. The winner will receive complimentary registration for this meeting as well as a complimentary 1-year membership to SHM.

For more information on the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/juniorinvestigator.