User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

New SHM Members – August 2016

J. Nicholson, Alabama

N. Tangutur, MD, Alabama

E. Ali, MD, Arizona

B. Cabrera, MD, Arizona

J. Castrolondono, MD, Arizona

T. Djurisic, MD, Arizona

R. Ernst, MD, Arizona

A. M. Mendez, Arizona

B. Mozaffari, DO, Arizona

A. Sharma, MD, Arizona

R. Soni, MD, Arizona

G. Neaville, MD, Arkansas

D. Sidhu, PA-C, British Columbia

S. Sidhu, EMBA, British Columbia

G. Bean, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAP, California

K. Bechler, MD, California

K. Chauhan, MPH, MD, California

N. Dave, MD, California

G. Dhanoa, California

A. Fisher, California

Y. Youssef, MD, California

S. De La Garza, MD, Colorado

V. Gundu, MD, Colorado

B. McCoy, DO, Colorado

J. Costanzo-Brown, FNP, Delaware

G. Siu, MD, Delaware

Y. Tal, MD, Delaware

J. Browning, NP-BC, DCNP, Florida

A. Chamseddin, MD, Florida

J. Florindez, MD, Florida

I. Gadalla, PA-C, Florida

G. Guess, Florida

M. E. Huckestein, ANP, Florida

D. Keerty, Florida

M. Mayo, DO, Florida

H. Nasser, MD, Florida

S. Rothstein, MSc, Florida

L. Succari, MD, Florida

S. Zimmer, MD, Florida

C. Ezigbo, Georgia

A. Mann, MD, Georgia

D. Wilmoth, Georgia

A. M. Sanchez Varela, MD, Guam

S. Cline, PhD, MBA, RN, Idaho

K. Abe, PA-C, Illinois

S. Chaudhry-Khan, MD, Illinois

K. Gallagher, Illinois

S. Kuhns, RN, Illinois

S. Pulimi, MD, Illinois

A. Urbonas, MD, Illinois

J. Chounramany, Iowa

B. Daniel, MD, Iowa

S. Joy, ARNP, Iowa

E. Kuperman, MD, Iowa

E. Shinozaki, MD, Iowa

S. Velur, MBBS, Iowa

L. Amos, MD, Kansas

L. Olson, MD, Kansas

M. Schultz, ANP, Kansas

M. Sharma, MD, Kansas

C. Castellanos, Kentucky

B. Mauldin, Louisiana

A. Thompson Soileau, MD, Louisiana

K. Hartman, MD, Maine

K. Carr, MD, Maryland

M. J. Dales, Maryland

K. Jansen, MPAS, PA-C, Maryland

A. Jubon, PA-C, Maryland

O. Schwartz, MD, Maryland

J. Withey, MD, Maryland

J. Louloudes, PA-C, Massachusetts

A. Susheelo, Massachusetts

T. Vu, Massachusetts

K. Bhatti, PA-C, Manitoba

R. Akram, Michigan

S. Federico, APRN-BC, Michigan

A. Mohammed, MBBS, Michigan

Q. Salamah, MD, Michigan

M. Schmuker, DO, Michigan

J. Dressen, Minnesota

G. Larson, MHA, Minnesota

T. Starkey, MD, Minnesota

V. Adike, MBBS, Mississippi

A. Collins, MD, Mississippi

J. Foreman, AGNP, Mississippi

J. Grady, MD, Mississippi

K. Heintzelman, DO, Mississippi

M. Moon, MD, Mississippi

A. Pamarthy, MD, Mississippi

J. Shores, Mississippi

J. Halsey, MD, MA, Missouri

M. Hendrix, MD, Missouri

U. Inampudi, MD, Missouri

C. Paris, APRN, FNP, Missouri

D. Payton, MD, Missouri

N. Crump, MD, Nebraska

T. Langenhan, MD, Nebraska

S. Garrett, MD, Nevada

C. Szot, MD, New Hampshire

D. Abbasi, MD, MBBS, New Jersey

S. M. Abel, ACNP, New Jersey

K. Alban, New Jersey

R. Amarini, New Jersey

J. Bauer, New Jersey

M. Branca, New Jersey

A. Hamarich, DO, New Jersey

S. Jaleel, MD, New Jersey

J. Knight, New Jersey

C. Lucchese, New Jersey

J. Peterson, New Jersey

M. Sohaib, MD, New Jersey

A. Azhar, MD, New York

B. Changlai, MD, New York

D. Gerling, New York

Y. Jin, New York

E. Palermo, ACNP, New York

V. Phillips, FNP, New York

P. Shi, DO, New York

B. Wertheimer, MD, New York

M. Yarowsky, MD, New York

C. Yates, MD, New York

J. Adams, MD, North Carolina

S. Akkaladevi, North Carolina

M. Arapian, MD, North Carolina

J. Cunningham, MD, North Carolina

K. Desronvil, ACNP, North Carolina

M. Dittmer, PA-C, North Carolina

Z. Edinger, ANP, North Carolina

T. Elswick, PA-C, North Carolina

D. Goble, MD, North Carolina

O. Jeelani, MD, MBBS, North Carolina

S. Lateef, North Carolina

G. Shalhoub, MD, North Carolina

J. Townsend, North Carolina

T. Turbett, North Carolina

K. Broderick-Forsgren, MD, Ohio

D. Foote, ACNP, Ohio

R. Muriithi, MBchB, Ohio

K. Patel, MD, Ohio

P. Veeramreddy, MBBS, Ohio

Y. Chen, MD, Oklahoma

M. Langmacher, BS, MD, Oklahoma

R. Mourh, MD, Oklahoma

M. Lukban, MD, Oregon

B. Ongole, MD, Oregon

J. Brunner, BS, MBA, Pennsylvania

M. Butala, Pennsylvania

B. Y. Chen, Pennsylvania

Z. Chen, MD, Pennsylvania

R. House, CRNP, Pennsylvania

M. Mar Fan, MD, Pennsylvania

E. McCamant, Pennsylvania

O. Okonkwo, MD, FACP, Pennsylvania

A. Savini, PA-C, Pennsylvania

A. Singh, MD, Pennsylvania

B. Smith, Pennsylvania

A. Tarique, MD, Pennsylvania

A. Whitsel, CRNP, Pennsylvania

P. Woods, MD, Pennsylvania

R. Ball, MHA, South Carolina

D. Burns, South Carolina

A. Kachalia, MD, South Carolina

L. Teague, South Carolina

D. Kindelspire, South Dakota

J. Bynum, Tennessee

A. Davidson, APRN-BC, Tennessee

P. Goleb, Tennessee

P. McCain, FNP, Tennessee

S. Patel, MD, Tennessee

A. Proffitt, ACNP, ANP, APRN, MSN, Tennessee

J. Tompkins, MD, Tennessee

F. Cardona, MD, Texas

N. Civunigunta, Texas

S. Khan, Texas

M. Mann, Texas

J. Muntz, MD, Texas

L. Swift, Texas

M. Abbott, FACHE, MBA, PharmD, Virginia

M. Alfaris, MD, Virginia

H. Aros, MD, Virginia

S. Naidu, MD, Virginia

M. Shaub, Virginia

O. Adeyeri, West Virginia

F. Farahmand, MD, West Virginia

J. Guinto, ARNP, West Virginia

S. Shiveley, MD, West Virginia

J. Singh, MBBch, West Virginia

G. Johnson, DO, Wisconsin

V. McFadden, MD, PhD, Wisconsin

S. Alam, Dhaka, Bangladesh

A. Fathala, MD, Saudi Arabia

J. Nicholson, Alabama

N. Tangutur, MD, Alabama

E. Ali, MD, Arizona

B. Cabrera, MD, Arizona

J. Castrolondono, MD, Arizona

T. Djurisic, MD, Arizona

R. Ernst, MD, Arizona

A. M. Mendez, Arizona

B. Mozaffari, DO, Arizona

A. Sharma, MD, Arizona

R. Soni, MD, Arizona

G. Neaville, MD, Arkansas

D. Sidhu, PA-C, British Columbia

S. Sidhu, EMBA, British Columbia

G. Bean, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAP, California

K. Bechler, MD, California

K. Chauhan, MPH, MD, California

N. Dave, MD, California

G. Dhanoa, California

A. Fisher, California

Y. Youssef, MD, California

S. De La Garza, MD, Colorado

V. Gundu, MD, Colorado

B. McCoy, DO, Colorado

J. Costanzo-Brown, FNP, Delaware

G. Siu, MD, Delaware

Y. Tal, MD, Delaware

J. Browning, NP-BC, DCNP, Florida

A. Chamseddin, MD, Florida

J. Florindez, MD, Florida

I. Gadalla, PA-C, Florida

G. Guess, Florida

M. E. Huckestein, ANP, Florida

D. Keerty, Florida

M. Mayo, DO, Florida

H. Nasser, MD, Florida

S. Rothstein, MSc, Florida

L. Succari, MD, Florida

S. Zimmer, MD, Florida

C. Ezigbo, Georgia

A. Mann, MD, Georgia

D. Wilmoth, Georgia

A. M. Sanchez Varela, MD, Guam

S. Cline, PhD, MBA, RN, Idaho

K. Abe, PA-C, Illinois

S. Chaudhry-Khan, MD, Illinois

K. Gallagher, Illinois

S. Kuhns, RN, Illinois

S. Pulimi, MD, Illinois

A. Urbonas, MD, Illinois

J. Chounramany, Iowa

B. Daniel, MD, Iowa

S. Joy, ARNP, Iowa

E. Kuperman, MD, Iowa

E. Shinozaki, MD, Iowa

S. Velur, MBBS, Iowa

L. Amos, MD, Kansas

L. Olson, MD, Kansas

M. Schultz, ANP, Kansas

M. Sharma, MD, Kansas

C. Castellanos, Kentucky

B. Mauldin, Louisiana

A. Thompson Soileau, MD, Louisiana

K. Hartman, MD, Maine

K. Carr, MD, Maryland

M. J. Dales, Maryland

K. Jansen, MPAS, PA-C, Maryland

A. Jubon, PA-C, Maryland

O. Schwartz, MD, Maryland

J. Withey, MD, Maryland

J. Louloudes, PA-C, Massachusetts

A. Susheelo, Massachusetts

T. Vu, Massachusetts

K. Bhatti, PA-C, Manitoba

R. Akram, Michigan

S. Federico, APRN-BC, Michigan

A. Mohammed, MBBS, Michigan

Q. Salamah, MD, Michigan

M. Schmuker, DO, Michigan

J. Dressen, Minnesota

G. Larson, MHA, Minnesota

T. Starkey, MD, Minnesota

V. Adike, MBBS, Mississippi

A. Collins, MD, Mississippi

J. Foreman, AGNP, Mississippi

J. Grady, MD, Mississippi

K. Heintzelman, DO, Mississippi

M. Moon, MD, Mississippi

A. Pamarthy, MD, Mississippi

J. Shores, Mississippi

J. Halsey, MD, MA, Missouri

M. Hendrix, MD, Missouri

U. Inampudi, MD, Missouri

C. Paris, APRN, FNP, Missouri

D. Payton, MD, Missouri

N. Crump, MD, Nebraska

T. Langenhan, MD, Nebraska

S. Garrett, MD, Nevada

C. Szot, MD, New Hampshire

D. Abbasi, MD, MBBS, New Jersey

S. M. Abel, ACNP, New Jersey

K. Alban, New Jersey

R. Amarini, New Jersey

J. Bauer, New Jersey

M. Branca, New Jersey

A. Hamarich, DO, New Jersey

S. Jaleel, MD, New Jersey

J. Knight, New Jersey

C. Lucchese, New Jersey

J. Peterson, New Jersey

M. Sohaib, MD, New Jersey

A. Azhar, MD, New York

B. Changlai, MD, New York

D. Gerling, New York

Y. Jin, New York

E. Palermo, ACNP, New York

V. Phillips, FNP, New York

P. Shi, DO, New York

B. Wertheimer, MD, New York

M. Yarowsky, MD, New York

C. Yates, MD, New York

J. Adams, MD, North Carolina

S. Akkaladevi, North Carolina

M. Arapian, MD, North Carolina

J. Cunningham, MD, North Carolina

K. Desronvil, ACNP, North Carolina

M. Dittmer, PA-C, North Carolina

Z. Edinger, ANP, North Carolina

T. Elswick, PA-C, North Carolina

D. Goble, MD, North Carolina

O. Jeelani, MD, MBBS, North Carolina

S. Lateef, North Carolina

G. Shalhoub, MD, North Carolina

J. Townsend, North Carolina

T. Turbett, North Carolina

K. Broderick-Forsgren, MD, Ohio

D. Foote, ACNP, Ohio

R. Muriithi, MBchB, Ohio

K. Patel, MD, Ohio

P. Veeramreddy, MBBS, Ohio

Y. Chen, MD, Oklahoma

M. Langmacher, BS, MD, Oklahoma

R. Mourh, MD, Oklahoma

M. Lukban, MD, Oregon

B. Ongole, MD, Oregon

J. Brunner, BS, MBA, Pennsylvania

M. Butala, Pennsylvania

B. Y. Chen, Pennsylvania

Z. Chen, MD, Pennsylvania

R. House, CRNP, Pennsylvania

M. Mar Fan, MD, Pennsylvania

E. McCamant, Pennsylvania

O. Okonkwo, MD, FACP, Pennsylvania

A. Savini, PA-C, Pennsylvania

A. Singh, MD, Pennsylvania

B. Smith, Pennsylvania

A. Tarique, MD, Pennsylvania

A. Whitsel, CRNP, Pennsylvania

P. Woods, MD, Pennsylvania

R. Ball, MHA, South Carolina

D. Burns, South Carolina

A. Kachalia, MD, South Carolina

L. Teague, South Carolina

D. Kindelspire, South Dakota

J. Bynum, Tennessee

A. Davidson, APRN-BC, Tennessee

P. Goleb, Tennessee

P. McCain, FNP, Tennessee

S. Patel, MD, Tennessee

A. Proffitt, ACNP, ANP, APRN, MSN, Tennessee

J. Tompkins, MD, Tennessee

F. Cardona, MD, Texas

N. Civunigunta, Texas

S. Khan, Texas

M. Mann, Texas

J. Muntz, MD, Texas

L. Swift, Texas

M. Abbott, FACHE, MBA, PharmD, Virginia

M. Alfaris, MD, Virginia

H. Aros, MD, Virginia

S. Naidu, MD, Virginia

M. Shaub, Virginia

O. Adeyeri, West Virginia

F. Farahmand, MD, West Virginia

J. Guinto, ARNP, West Virginia

S. Shiveley, MD, West Virginia

J. Singh, MBBch, West Virginia

G. Johnson, DO, Wisconsin

V. McFadden, MD, PhD, Wisconsin

S. Alam, Dhaka, Bangladesh

A. Fathala, MD, Saudi Arabia

J. Nicholson, Alabama

N. Tangutur, MD, Alabama

E. Ali, MD, Arizona

B. Cabrera, MD, Arizona

J. Castrolondono, MD, Arizona

T. Djurisic, MD, Arizona

R. Ernst, MD, Arizona

A. M. Mendez, Arizona

B. Mozaffari, DO, Arizona

A. Sharma, MD, Arizona

R. Soni, MD, Arizona

G. Neaville, MD, Arkansas

D. Sidhu, PA-C, British Columbia

S. Sidhu, EMBA, British Columbia

G. Bean, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAP, California

K. Bechler, MD, California

K. Chauhan, MPH, MD, California

N. Dave, MD, California

G. Dhanoa, California

A. Fisher, California

Y. Youssef, MD, California

S. De La Garza, MD, Colorado

V. Gundu, MD, Colorado

B. McCoy, DO, Colorado

J. Costanzo-Brown, FNP, Delaware

G. Siu, MD, Delaware

Y. Tal, MD, Delaware

J. Browning, NP-BC, DCNP, Florida

A. Chamseddin, MD, Florida

J. Florindez, MD, Florida

I. Gadalla, PA-C, Florida

G. Guess, Florida

M. E. Huckestein, ANP, Florida

D. Keerty, Florida

M. Mayo, DO, Florida

H. Nasser, MD, Florida

S. Rothstein, MSc, Florida

L. Succari, MD, Florida

S. Zimmer, MD, Florida

C. Ezigbo, Georgia

A. Mann, MD, Georgia

D. Wilmoth, Georgia

A. M. Sanchez Varela, MD, Guam

S. Cline, PhD, MBA, RN, Idaho

K. Abe, PA-C, Illinois

S. Chaudhry-Khan, MD, Illinois

K. Gallagher, Illinois

S. Kuhns, RN, Illinois

S. Pulimi, MD, Illinois

A. Urbonas, MD, Illinois

J. Chounramany, Iowa

B. Daniel, MD, Iowa

S. Joy, ARNP, Iowa

E. Kuperman, MD, Iowa

E. Shinozaki, MD, Iowa

S. Velur, MBBS, Iowa

L. Amos, MD, Kansas

L. Olson, MD, Kansas

M. Schultz, ANP, Kansas

M. Sharma, MD, Kansas

C. Castellanos, Kentucky

B. Mauldin, Louisiana

A. Thompson Soileau, MD, Louisiana

K. Hartman, MD, Maine

K. Carr, MD, Maryland

M. J. Dales, Maryland

K. Jansen, MPAS, PA-C, Maryland

A. Jubon, PA-C, Maryland

O. Schwartz, MD, Maryland

J. Withey, MD, Maryland

J. Louloudes, PA-C, Massachusetts

A. Susheelo, Massachusetts

T. Vu, Massachusetts

K. Bhatti, PA-C, Manitoba

R. Akram, Michigan

S. Federico, APRN-BC, Michigan

A. Mohammed, MBBS, Michigan

Q. Salamah, MD, Michigan

M. Schmuker, DO, Michigan

J. Dressen, Minnesota

G. Larson, MHA, Minnesota

T. Starkey, MD, Minnesota

V. Adike, MBBS, Mississippi

A. Collins, MD, Mississippi

J. Foreman, AGNP, Mississippi

J. Grady, MD, Mississippi

K. Heintzelman, DO, Mississippi

M. Moon, MD, Mississippi

A. Pamarthy, MD, Mississippi

J. Shores, Mississippi

J. Halsey, MD, MA, Missouri

M. Hendrix, MD, Missouri

U. Inampudi, MD, Missouri

C. Paris, APRN, FNP, Missouri

D. Payton, MD, Missouri

N. Crump, MD, Nebraska

T. Langenhan, MD, Nebraska

S. Garrett, MD, Nevada

C. Szot, MD, New Hampshire

D. Abbasi, MD, MBBS, New Jersey

S. M. Abel, ACNP, New Jersey

K. Alban, New Jersey

R. Amarini, New Jersey

J. Bauer, New Jersey

M. Branca, New Jersey

A. Hamarich, DO, New Jersey

S. Jaleel, MD, New Jersey

J. Knight, New Jersey

C. Lucchese, New Jersey

J. Peterson, New Jersey

M. Sohaib, MD, New Jersey

A. Azhar, MD, New York

B. Changlai, MD, New York

D. Gerling, New York

Y. Jin, New York

E. Palermo, ACNP, New York

V. Phillips, FNP, New York

P. Shi, DO, New York

B. Wertheimer, MD, New York

M. Yarowsky, MD, New York

C. Yates, MD, New York

J. Adams, MD, North Carolina

S. Akkaladevi, North Carolina

M. Arapian, MD, North Carolina

J. Cunningham, MD, North Carolina

K. Desronvil, ACNP, North Carolina

M. Dittmer, PA-C, North Carolina

Z. Edinger, ANP, North Carolina

T. Elswick, PA-C, North Carolina

D. Goble, MD, North Carolina

O. Jeelani, MD, MBBS, North Carolina

S. Lateef, North Carolina

G. Shalhoub, MD, North Carolina

J. Townsend, North Carolina

T. Turbett, North Carolina

K. Broderick-Forsgren, MD, Ohio

D. Foote, ACNP, Ohio

R. Muriithi, MBchB, Ohio

K. Patel, MD, Ohio

P. Veeramreddy, MBBS, Ohio

Y. Chen, MD, Oklahoma

M. Langmacher, BS, MD, Oklahoma

R. Mourh, MD, Oklahoma

M. Lukban, MD, Oregon

B. Ongole, MD, Oregon

J. Brunner, BS, MBA, Pennsylvania

M. Butala, Pennsylvania

B. Y. Chen, Pennsylvania

Z. Chen, MD, Pennsylvania

R. House, CRNP, Pennsylvania

M. Mar Fan, MD, Pennsylvania

E. McCamant, Pennsylvania

O. Okonkwo, MD, FACP, Pennsylvania

A. Savini, PA-C, Pennsylvania

A. Singh, MD, Pennsylvania

B. Smith, Pennsylvania

A. Tarique, MD, Pennsylvania

A. Whitsel, CRNP, Pennsylvania

P. Woods, MD, Pennsylvania

R. Ball, MHA, South Carolina

D. Burns, South Carolina

A. Kachalia, MD, South Carolina

L. Teague, South Carolina

D. Kindelspire, South Dakota

J. Bynum, Tennessee

A. Davidson, APRN-BC, Tennessee

P. Goleb, Tennessee

P. McCain, FNP, Tennessee

S. Patel, MD, Tennessee

A. Proffitt, ACNP, ANP, APRN, MSN, Tennessee

J. Tompkins, MD, Tennessee

F. Cardona, MD, Texas

N. Civunigunta, Texas

S. Khan, Texas

M. Mann, Texas

J. Muntz, MD, Texas

L. Swift, Texas

M. Abbott, FACHE, MBA, PharmD, Virginia

M. Alfaris, MD, Virginia

H. Aros, MD, Virginia

S. Naidu, MD, Virginia

M. Shaub, Virginia

O. Adeyeri, West Virginia

F. Farahmand, MD, West Virginia

J. Guinto, ARNP, West Virginia

S. Shiveley, MD, West Virginia

J. Singh, MBBch, West Virginia

G. Johnson, DO, Wisconsin

V. McFadden, MD, PhD, Wisconsin

S. Alam, Dhaka, Bangladesh

A. Fathala, MD, Saudi Arabia

Register for Academic Hospitalist Academy

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 12–15, at the scenic Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. You will experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercises, and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1-to-10 faculty-to-student ratio.

AHA’s principal goals are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Register now at www.academichospitalist.org.

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 12–15, at the scenic Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. You will experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercises, and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1-to-10 faculty-to-student ratio.

AHA’s principal goals are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Register now at www.academichospitalist.org.

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 12–15, at the scenic Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. You will experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercises, and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1-to-10 faculty-to-student ratio.

AHA’s principal goals are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Register now at www.academichospitalist.org.

PHM16: How to Design, Improve Educational Programs at Community Hospitals

Facilitators: Christopher Russo, MD, FAAP, Laura Hodo, MD, and Lauren Wilson, MD

This session discussed ways to design and improve education within community hospital settings. It was done via a didactic session, breakout groups, and an electronic assessment tool that can be used beyond the session. Facilitators included the workshop leaders and co-leaders along with current PHM fellows and educators from community and academic settings.

During the didactic session a general background of importance of education during times of increasing academic and community site affiliations was discussed. This included the strengths of community hospitals for learners such as “appropriate learner autonomy”, “exposure to different career paths”, and “transfer decision-making”.

Some of the challenges discussed in regards to developing an educational structure in community settings included:

- Logistics

- Making the case for education

- Legal framework (i.e. Affiliation agreements, Liability)

- Finances (i.e. GME funding)

- Paperwork burden (ex. Licensing, Credentialing)

- Learning Environment

- Complementing clinical work with materials

- Autonomy/Supervision balancing

- Developing Clinical teachers

The didactic session also reviewed the 6 steps for curriculum development: General Needs Assessment, Targeted Needs Assessment, Goals and Objectives, Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. Each of these was described in further detail with relevant examples.

Groups were broken out into small groups based on four learner types: Medical Students, Family Medicine Residents, Pediatric Residents, and PHM Fellows. Within each group a “Program Development Matrix” was distributed to assess the support from leadership and logistics within each setting. Each one of these was separated into subgroups such as credentialing, financial support, housing/travel, and preceptor recruitment.

A separate “Curriculum Development Matrix” was utilized during breakout groups that focused on curriculum development. This matrix was broken into 3 areas: Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. These were broken down into subgroups such as content, identifying resources, and remediation planning. The group was asked to determine short and long term goals with action steps for both of these matrix subgroups.

Overall the session presented a structured way of assessing the educational environment for learners in community settings. It gave tangible tools to develop a needs assessment and planning to achieve the defined goals that can be readily used by sites who wish to develop or improve their current educational framework.

Dr. Francisco Alvarez, MD, FAAP, is a pediatric hospitalist and director of the Children's National Health System Community Hospital Services in Washington, D.C.

Facilitators: Christopher Russo, MD, FAAP, Laura Hodo, MD, and Lauren Wilson, MD

This session discussed ways to design and improve education within community hospital settings. It was done via a didactic session, breakout groups, and an electronic assessment tool that can be used beyond the session. Facilitators included the workshop leaders and co-leaders along with current PHM fellows and educators from community and academic settings.

During the didactic session a general background of importance of education during times of increasing academic and community site affiliations was discussed. This included the strengths of community hospitals for learners such as “appropriate learner autonomy”, “exposure to different career paths”, and “transfer decision-making”.

Some of the challenges discussed in regards to developing an educational structure in community settings included:

- Logistics

- Making the case for education

- Legal framework (i.e. Affiliation agreements, Liability)

- Finances (i.e. GME funding)

- Paperwork burden (ex. Licensing, Credentialing)

- Learning Environment

- Complementing clinical work with materials

- Autonomy/Supervision balancing

- Developing Clinical teachers

The didactic session also reviewed the 6 steps for curriculum development: General Needs Assessment, Targeted Needs Assessment, Goals and Objectives, Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. Each of these was described in further detail with relevant examples.

Groups were broken out into small groups based on four learner types: Medical Students, Family Medicine Residents, Pediatric Residents, and PHM Fellows. Within each group a “Program Development Matrix” was distributed to assess the support from leadership and logistics within each setting. Each one of these was separated into subgroups such as credentialing, financial support, housing/travel, and preceptor recruitment.

A separate “Curriculum Development Matrix” was utilized during breakout groups that focused on curriculum development. This matrix was broken into 3 areas: Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. These were broken down into subgroups such as content, identifying resources, and remediation planning. The group was asked to determine short and long term goals with action steps for both of these matrix subgroups.

Overall the session presented a structured way of assessing the educational environment for learners in community settings. It gave tangible tools to develop a needs assessment and planning to achieve the defined goals that can be readily used by sites who wish to develop or improve their current educational framework.

Dr. Francisco Alvarez, MD, FAAP, is a pediatric hospitalist and director of the Children's National Health System Community Hospital Services in Washington, D.C.

Facilitators: Christopher Russo, MD, FAAP, Laura Hodo, MD, and Lauren Wilson, MD

This session discussed ways to design and improve education within community hospital settings. It was done via a didactic session, breakout groups, and an electronic assessment tool that can be used beyond the session. Facilitators included the workshop leaders and co-leaders along with current PHM fellows and educators from community and academic settings.

During the didactic session a general background of importance of education during times of increasing academic and community site affiliations was discussed. This included the strengths of community hospitals for learners such as “appropriate learner autonomy”, “exposure to different career paths”, and “transfer decision-making”.

Some of the challenges discussed in regards to developing an educational structure in community settings included:

- Logistics

- Making the case for education

- Legal framework (i.e. Affiliation agreements, Liability)

- Finances (i.e. GME funding)

- Paperwork burden (ex. Licensing, Credentialing)

- Learning Environment

- Complementing clinical work with materials

- Autonomy/Supervision balancing

- Developing Clinical teachers

The didactic session also reviewed the 6 steps for curriculum development: General Needs Assessment, Targeted Needs Assessment, Goals and Objectives, Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. Each of these was described in further detail with relevant examples.

Groups were broken out into small groups based on four learner types: Medical Students, Family Medicine Residents, Pediatric Residents, and PHM Fellows. Within each group a “Program Development Matrix” was distributed to assess the support from leadership and logistics within each setting. Each one of these was separated into subgroups such as credentialing, financial support, housing/travel, and preceptor recruitment.

A separate “Curriculum Development Matrix” was utilized during breakout groups that focused on curriculum development. This matrix was broken into 3 areas: Educational Strategies, Implementation, and Evaluation/Feedback. These were broken down into subgroups such as content, identifying resources, and remediation planning. The group was asked to determine short and long term goals with action steps for both of these matrix subgroups.

Overall the session presented a structured way of assessing the educational environment for learners in community settings. It gave tangible tools to develop a needs assessment and planning to achieve the defined goals that can be readily used by sites who wish to develop or improve their current educational framework.

Dr. Francisco Alvarez, MD, FAAP, is a pediatric hospitalist and director of the Children's National Health System Community Hospital Services in Washington, D.C.

PHM16: Promoting, Teaching Pediatric High Value Care

As we embark on Choosing Wisely, pediatric hospitalists gathered to attend this fruitful discussion on not only how to change our way of thinking but also how to feed it forward to our trainees. The barriers to promoting and teaching high value care are plenty and essentially universal to academic and community sites: we have had no formal teaching, there is cultural resistance and there is lack of transparency on costs and charges.

Perhaps the questions we should be asking ourselves, our trainees and our families are:

- Instead of “What’s the matter?” ask “What matters?”

- Instead of asking “Will that test change our management?” ask “Does that test benefit the patient? What are the harms of the test?”

Thinking about effects of tests downstream, the “testing cascade” can be a great mental exercise for the higher-level learner to understand the value, the unknowns we face in our daily decisions and simultaneously improving our understanding of best practices.

A toolkit was provided to help bring back resources and methods to teach high value care in morning report/ case conference settings, bedside teaching and family discussions.

One point is clear though—there is still a long way to go to move the pendulum to the side of value based practice and teaching. There is still controversy on how and whether cost should be discussed with the family. Cost is more than just monetary values—family anxiety and patient harm may resonate more with families as we perfect our skills in shared decision making.

This serves as an exciting time to unite and better our understanding on why we do what we do and deliberately think about downstream effects. High value care curriculum for medical students, residents, fellows and even faculty is an area ripe for further educational and clinical research.

When asking for the Pediatric Value Meal, this is one where I will not Super size it!

Dr. Akshata Hopkins, MD FAAP, is an academic hospitalist at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

As we embark on Choosing Wisely, pediatric hospitalists gathered to attend this fruitful discussion on not only how to change our way of thinking but also how to feed it forward to our trainees. The barriers to promoting and teaching high value care are plenty and essentially universal to academic and community sites: we have had no formal teaching, there is cultural resistance and there is lack of transparency on costs and charges.

Perhaps the questions we should be asking ourselves, our trainees and our families are:

- Instead of “What’s the matter?” ask “What matters?”

- Instead of asking “Will that test change our management?” ask “Does that test benefit the patient? What are the harms of the test?”

Thinking about effects of tests downstream, the “testing cascade” can be a great mental exercise for the higher-level learner to understand the value, the unknowns we face in our daily decisions and simultaneously improving our understanding of best practices.

A toolkit was provided to help bring back resources and methods to teach high value care in morning report/ case conference settings, bedside teaching and family discussions.

One point is clear though—there is still a long way to go to move the pendulum to the side of value based practice and teaching. There is still controversy on how and whether cost should be discussed with the family. Cost is more than just monetary values—family anxiety and patient harm may resonate more with families as we perfect our skills in shared decision making.

This serves as an exciting time to unite and better our understanding on why we do what we do and deliberately think about downstream effects. High value care curriculum for medical students, residents, fellows and even faculty is an area ripe for further educational and clinical research.

When asking for the Pediatric Value Meal, this is one where I will not Super size it!

Dr. Akshata Hopkins, MD FAAP, is an academic hospitalist at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

As we embark on Choosing Wisely, pediatric hospitalists gathered to attend this fruitful discussion on not only how to change our way of thinking but also how to feed it forward to our trainees. The barriers to promoting and teaching high value care are plenty and essentially universal to academic and community sites: we have had no formal teaching, there is cultural resistance and there is lack of transparency on costs and charges.

Perhaps the questions we should be asking ourselves, our trainees and our families are:

- Instead of “What’s the matter?” ask “What matters?”

- Instead of asking “Will that test change our management?” ask “Does that test benefit the patient? What are the harms of the test?”

Thinking about effects of tests downstream, the “testing cascade” can be a great mental exercise for the higher-level learner to understand the value, the unknowns we face in our daily decisions and simultaneously improving our understanding of best practices.

A toolkit was provided to help bring back resources and methods to teach high value care in morning report/ case conference settings, bedside teaching and family discussions.

One point is clear though—there is still a long way to go to move the pendulum to the side of value based practice and teaching. There is still controversy on how and whether cost should be discussed with the family. Cost is more than just monetary values—family anxiety and patient harm may resonate more with families as we perfect our skills in shared decision making.

This serves as an exciting time to unite and better our understanding on why we do what we do and deliberately think about downstream effects. High value care curriculum for medical students, residents, fellows and even faculty is an area ripe for further educational and clinical research.

When asking for the Pediatric Value Meal, this is one where I will not Super size it!

Dr. Akshata Hopkins, MD FAAP, is an academic hospitalist at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

Sarah Stella, MD, Has a Heart for Safety-Net Hospital Medicine

The best advice Sarah Stella, MD, ever received was simple: “You can’t cure everyone, but you can help everyone.” Why has the adage stuck with her?

Because the advice came from her dad, “and he’s been right about a lot of things before,” she says with a smile.

Dr. Stella got into medicine—clearly with her father’s blessing—to satisfy her “intense curiosity about my fellow human beings and to try to ease suffering.” She has risen to be an academic hospitalist at Denver Health and is one of eight new members of Team Hospitalist, The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board.

Question: Tell us about your training. What did you like most/dislike during the process?

Answer: I attended medical school at Michigan State College of Human Medicine. I appreciated their humanistic approach to medical education. I chose the University of Colorado for my internal medicine residency because I love the sunshine and the mountains and because I thought the large academic program would complement my community-based medical school training. I loved being able to easily access nature on my days off.

Q: What do you like most about working as a hospitalist?

A: Spending time with incredible patients and working to solve difficult problems alongside amazing colleagues. I also love the diversity of the work, being involved in direct patient care, teaching students and residents, being a part of committees, performing quality improvement research. I love the flexibility of the job, which allows me to spend time with my family and travel fairly frequently to far-flung places.

Q: Did you have a mentor during your training or early career?

A: My earliest mentor was my father, also a physician [an oncologist]. Some of my earliest medical memories are of going to the hospital with my dad, who also brought home petri dishes from the lab, which my brother and I then used to perform household science experiments. My dad taught me my first lessons about the scientific method and about the importance of a strong work ethic and mentorship. Since then, I have had many outstanding mentors and role models for various aspects of my training/career. During my time at Denver Health, Drs. Richard K. Albert and Marisha Burden have provided me with invaluable mentorship in my scholarly pursuits.

Q: Have you tried to mentor others? Why or why not?

A: I have really loved mentoring students and residents. It is among the most meaningful experiences of my career. Presently, I am a mentor for undergraduate students from underrepresented minority groups. The maturity, passion, and drive these students possess inspires me.

Q: Why is your mentoring focused on minorities? What is the appeal of that to you?

A: I mentor students and residents from all backgrounds. However, mentoring students from underrepresented minority groups is especially important to me. Ethnic minorities continue to have decreased access to healthcare and disproportionately high morbidity and mortality. In order to improve these disparities, we need to have more healthcare providers from these groups. Yet such students, while they may initially be attracted to a career in medicine, are much less likely to maintain their interest. The reasons for this are complicated but may be explained by differences in access to mentors to help guide and inspire them, write letters, etc.

Q: As a hospitalist, seeing most of your patients for the very first time, what aspect of patient care is most challenging?

A: Developing a rapport with patients. I try to use some techniques from social psychology to help me more easily. The hospital is a particularly depersonalizing place, so trying to see the person behind the patient does help.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Really connecting with patients and seeing them thrive. Working at a safety-net hospital, I have the privilege of caring for some of the most underserved but some of the most gracious and beautiful people.

Q: Are you on teaching service? If so, what aspect of teaching in the 21st century is most difficult? And what is most enjoyable?

A: I do enjoy supervising medical students and residents at all levels and attend frequently on the medical wards. I particularly love teaching medical students because of their enthusiasm and curiosity. I love being reminded of basic pathophysiology by a thoughtfully asked question from a medical student. I am a big advocate of bedside rounding. Finding a way to do this efficiently and while teaching to all the levels on the team is challenging. Also, I still enjoy my own direct patient care activities and feel that they challenge me in a different way and make me a better teacher.

Q: Outside of patient care, tell us about your career interests.

A: My research has focused on understanding problems experienced by patients following hospital discharge and designing systems to help ameliorate them. On an institutional level, I serve on several committees, including the Utilization Review Committee, and a group aiming to improve collaboration between hospitalists and primary care physicians and improve discharge transitions. I have participated in several LEAN events aimed at understanding and improving various systems issues.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family and friends, sunshine, and travel. My husband grew up in Papua, New Guinea, and Australia, and both of his parents are physicians, so he is very understanding and not the least bit grossed out when I regale him with stories involving bodily fluids. We have a beautiful, inquisitive 3-year-old daughter and her furry older sister, Ginger Wasabi Ninja. As the oldest of seven, I also love hanging out with my siblings.

Q: What SHM event has made the most lasting impression on you?

A: I really enjoyed HM16, particularly the keynote address by our U.S. Surgeon General and fellow hospitalist, Vivek Murthy, MD, who discussed the role hospitalists can play in public health. His message that we hospitalists should put as much of an effort into trying to improve health outside the walls of the hospital as we do within the walls really resonated with me and has encouraged me to get more involved in the community. TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The best advice Sarah Stella, MD, ever received was simple: “You can’t cure everyone, but you can help everyone.” Why has the adage stuck with her?

Because the advice came from her dad, “and he’s been right about a lot of things before,” she says with a smile.

Dr. Stella got into medicine—clearly with her father’s blessing—to satisfy her “intense curiosity about my fellow human beings and to try to ease suffering.” She has risen to be an academic hospitalist at Denver Health and is one of eight new members of Team Hospitalist, The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board.

Question: Tell us about your training. What did you like most/dislike during the process?

Answer: I attended medical school at Michigan State College of Human Medicine. I appreciated their humanistic approach to medical education. I chose the University of Colorado for my internal medicine residency because I love the sunshine and the mountains and because I thought the large academic program would complement my community-based medical school training. I loved being able to easily access nature on my days off.

Q: What do you like most about working as a hospitalist?

A: Spending time with incredible patients and working to solve difficult problems alongside amazing colleagues. I also love the diversity of the work, being involved in direct patient care, teaching students and residents, being a part of committees, performing quality improvement research. I love the flexibility of the job, which allows me to spend time with my family and travel fairly frequently to far-flung places.

Q: Did you have a mentor during your training or early career?

A: My earliest mentor was my father, also a physician [an oncologist]. Some of my earliest medical memories are of going to the hospital with my dad, who also brought home petri dishes from the lab, which my brother and I then used to perform household science experiments. My dad taught me my first lessons about the scientific method and about the importance of a strong work ethic and mentorship. Since then, I have had many outstanding mentors and role models for various aspects of my training/career. During my time at Denver Health, Drs. Richard K. Albert and Marisha Burden have provided me with invaluable mentorship in my scholarly pursuits.

Q: Have you tried to mentor others? Why or why not?

A: I have really loved mentoring students and residents. It is among the most meaningful experiences of my career. Presently, I am a mentor for undergraduate students from underrepresented minority groups. The maturity, passion, and drive these students possess inspires me.

Q: Why is your mentoring focused on minorities? What is the appeal of that to you?

A: I mentor students and residents from all backgrounds. However, mentoring students from underrepresented minority groups is especially important to me. Ethnic minorities continue to have decreased access to healthcare and disproportionately high morbidity and mortality. In order to improve these disparities, we need to have more healthcare providers from these groups. Yet such students, while they may initially be attracted to a career in medicine, are much less likely to maintain their interest. The reasons for this are complicated but may be explained by differences in access to mentors to help guide and inspire them, write letters, etc.

Q: As a hospitalist, seeing most of your patients for the very first time, what aspect of patient care is most challenging?

A: Developing a rapport with patients. I try to use some techniques from social psychology to help me more easily. The hospital is a particularly depersonalizing place, so trying to see the person behind the patient does help.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Really connecting with patients and seeing them thrive. Working at a safety-net hospital, I have the privilege of caring for some of the most underserved but some of the most gracious and beautiful people.

Q: Are you on teaching service? If so, what aspect of teaching in the 21st century is most difficult? And what is most enjoyable?

A: I do enjoy supervising medical students and residents at all levels and attend frequently on the medical wards. I particularly love teaching medical students because of their enthusiasm and curiosity. I love being reminded of basic pathophysiology by a thoughtfully asked question from a medical student. I am a big advocate of bedside rounding. Finding a way to do this efficiently and while teaching to all the levels on the team is challenging. Also, I still enjoy my own direct patient care activities and feel that they challenge me in a different way and make me a better teacher.

Q: Outside of patient care, tell us about your career interests.

A: My research has focused on understanding problems experienced by patients following hospital discharge and designing systems to help ameliorate them. On an institutional level, I serve on several committees, including the Utilization Review Committee, and a group aiming to improve collaboration between hospitalists and primary care physicians and improve discharge transitions. I have participated in several LEAN events aimed at understanding and improving various systems issues.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family and friends, sunshine, and travel. My husband grew up in Papua, New Guinea, and Australia, and both of his parents are physicians, so he is very understanding and not the least bit grossed out when I regale him with stories involving bodily fluids. We have a beautiful, inquisitive 3-year-old daughter and her furry older sister, Ginger Wasabi Ninja. As the oldest of seven, I also love hanging out with my siblings.

Q: What SHM event has made the most lasting impression on you?

A: I really enjoyed HM16, particularly the keynote address by our U.S. Surgeon General and fellow hospitalist, Vivek Murthy, MD, who discussed the role hospitalists can play in public health. His message that we hospitalists should put as much of an effort into trying to improve health outside the walls of the hospital as we do within the walls really resonated with me and has encouraged me to get more involved in the community. TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The best advice Sarah Stella, MD, ever received was simple: “You can’t cure everyone, but you can help everyone.” Why has the adage stuck with her?

Because the advice came from her dad, “and he’s been right about a lot of things before,” she says with a smile.

Dr. Stella got into medicine—clearly with her father’s blessing—to satisfy her “intense curiosity about my fellow human beings and to try to ease suffering.” She has risen to be an academic hospitalist at Denver Health and is one of eight new members of Team Hospitalist, The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board.

Question: Tell us about your training. What did you like most/dislike during the process?

Answer: I attended medical school at Michigan State College of Human Medicine. I appreciated their humanistic approach to medical education. I chose the University of Colorado for my internal medicine residency because I love the sunshine and the mountains and because I thought the large academic program would complement my community-based medical school training. I loved being able to easily access nature on my days off.

Q: What do you like most about working as a hospitalist?

A: Spending time with incredible patients and working to solve difficult problems alongside amazing colleagues. I also love the diversity of the work, being involved in direct patient care, teaching students and residents, being a part of committees, performing quality improvement research. I love the flexibility of the job, which allows me to spend time with my family and travel fairly frequently to far-flung places.

Q: Did you have a mentor during your training or early career?

A: My earliest mentor was my father, also a physician [an oncologist]. Some of my earliest medical memories are of going to the hospital with my dad, who also brought home petri dishes from the lab, which my brother and I then used to perform household science experiments. My dad taught me my first lessons about the scientific method and about the importance of a strong work ethic and mentorship. Since then, I have had many outstanding mentors and role models for various aspects of my training/career. During my time at Denver Health, Drs. Richard K. Albert and Marisha Burden have provided me with invaluable mentorship in my scholarly pursuits.

Q: Have you tried to mentor others? Why or why not?

A: I have really loved mentoring students and residents. It is among the most meaningful experiences of my career. Presently, I am a mentor for undergraduate students from underrepresented minority groups. The maturity, passion, and drive these students possess inspires me.

Q: Why is your mentoring focused on minorities? What is the appeal of that to you?

A: I mentor students and residents from all backgrounds. However, mentoring students from underrepresented minority groups is especially important to me. Ethnic minorities continue to have decreased access to healthcare and disproportionately high morbidity and mortality. In order to improve these disparities, we need to have more healthcare providers from these groups. Yet such students, while they may initially be attracted to a career in medicine, are much less likely to maintain their interest. The reasons for this are complicated but may be explained by differences in access to mentors to help guide and inspire them, write letters, etc.

Q: As a hospitalist, seeing most of your patients for the very first time, what aspect of patient care is most challenging?

A: Developing a rapport with patients. I try to use some techniques from social psychology to help me more easily. The hospital is a particularly depersonalizing place, so trying to see the person behind the patient does help.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Really connecting with patients and seeing them thrive. Working at a safety-net hospital, I have the privilege of caring for some of the most underserved but some of the most gracious and beautiful people.

Q: Are you on teaching service? If so, what aspect of teaching in the 21st century is most difficult? And what is most enjoyable?

A: I do enjoy supervising medical students and residents at all levels and attend frequently on the medical wards. I particularly love teaching medical students because of their enthusiasm and curiosity. I love being reminded of basic pathophysiology by a thoughtfully asked question from a medical student. I am a big advocate of bedside rounding. Finding a way to do this efficiently and while teaching to all the levels on the team is challenging. Also, I still enjoy my own direct patient care activities and feel that they challenge me in a different way and make me a better teacher.

Q: Outside of patient care, tell us about your career interests.

A: My research has focused on understanding problems experienced by patients following hospital discharge and designing systems to help ameliorate them. On an institutional level, I serve on several committees, including the Utilization Review Committee, and a group aiming to improve collaboration between hospitalists and primary care physicians and improve discharge transitions. I have participated in several LEAN events aimed at understanding and improving various systems issues.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

A: My family and friends, sunshine, and travel. My husband grew up in Papua, New Guinea, and Australia, and both of his parents are physicians, so he is very understanding and not the least bit grossed out when I regale him with stories involving bodily fluids. We have a beautiful, inquisitive 3-year-old daughter and her furry older sister, Ginger Wasabi Ninja. As the oldest of seven, I also love hanging out with my siblings.

Q: What SHM event has made the most lasting impression on you?

A: I really enjoyed HM16, particularly the keynote address by our U.S. Surgeon General and fellow hospitalist, Vivek Murthy, MD, who discussed the role hospitalists can play in public health. His message that we hospitalists should put as much of an effort into trying to improve health outside the walls of the hospital as we do within the walls really resonated with me and has encouraged me to get more involved in the community. TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Tips for Communicating with Empathy

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

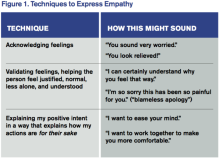

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Should Physicians Care about Costs?

The healthcare industry is under major stress from steady declines in all sources of revenue. The drivers are multifactorial but include declining reimbursement from payors, a shift from fee-for-service to pay-for-performance, and state-by-state variability in patients covered by Medicaid, by high-deductible plans, or by being uninsured. In academic medical centers, rising overhead costs coupled with a reticence to raise student tuition and declining research funding streams have further compounded the situation.

Regardless of the actual numbers, all healthcare institutions are feeling the financial pinch. Most are intensely focused on cost-reduction efforts. The question is, what do physicians think about their role in these efforts, and what efforts will be most effective?

A recent survey of a large physician group practice found that many physicians do not know what their cost drivers are or do not think it is their role to participate in cost-reduction efforts.1 Of note, the group practice in the survey is a Pioneer Medicare accountable care organization (ACO) and participates in a combination of fee-for-service and capitated contracts.

Within the survey, the researchers embedded a cost-consciousness scale, which is a validated survey tool designed to assess daily cost consciousness. They also embedded other survey items to determine the physicians’ concerns for malpractice, comfort with diagnostic uncertainty, and perception of patient-family pressure for utilization of services. The average overall cost-consciousness score was 29 out of 44, with higher scores indicating more cost consciousness.

Almost all physicians agreed that they need to reduce unnecessary testing (97%), need to adhere to guidelines (98%), and have a responsibility to control costs (92%). However, 33% felt it was unfair for them to have to be both cost-conscious and concerned with the welfare of their patients.

Approximately a third of respondents also felt that there was too much emphasis on cost and that physicians are too busy to worry about costs.

More than a third (37%) said they did not have good knowledge about test-procedure cost within their system.

More than half of physicians felt pressure from patients to perform tests and procedures (from 68% of primary-care physicians, 58% of medical specialists, and 56% of surgical specialists) and felt pressure to refer to consultants (from 65% of primary-care physicians, 35% of medical specialists, and 34% of surgical specialists).

Based on this survey and other literature about physicians’ perceptions of their role and their ability to control costs, it is clear that the first step in understanding how to engage physicians in cost-reducing efforts is to understand what the drivers are for utilization and what the concerns are for reducing cost. Many hypothesize that the drivers to support the status quo include a fear of litigation, fear of missing a diagnosis, and patient demands for services. Another major driver of current utilization is that there is ongoing support for the status quo, as the majority of reimbursement for providers is still based on fee-for-service.

Change Efforts

One cost-reducing effort that has gained widespread enthusiasm from medical societies is the Choosing Wisely campaign. This campaign is an effort originally driven by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation to help physicians become aware of and reduce unnecessary utilization of resources. Each Choosing Wisely list is generated and endorsed by the relevant medical society and widely advertised to physicians via a variety of mechanisms. More than 70 medical societies have participated in the effort to date.

The recommendations are often widely accepted by those in the specialty since they are evidence-based and derived and advertised by their own specialty societies. In the survey mentioned above, almost all physicians agreed that their Choosing Wisely was a good source of guidance (ranging from 92% of surgical specialties to 97% of primary-care physicians). In order to drive the movement from the patient perspective, Consumer Reports has developed educational materials aimed at the consumer side of healthcare (ie, patients and families).

As Consumer Reports suggests, the first step to implementing cost-conscious care is to measure awareness of cost and causes of overutilization. By first understanding behaviors, a group can then work to impact such behaviors. It is highly likely that the drivers are different based on the specialty of the physician, the patient population being served, and the local healthcare market drivers. As such, there will not be a single, across-the-board solution to reducing unnecessary utilization of services (and therefore cost), but interventions will need to be tailored to different groups depending on the drivers of cost locally.

Depending on the issues within a group, successful interventions could include:

- Decision support tools (for appropriate use of consultants and diagnostic tests)

- Display of testing costs (not just at the time of ordering)

- Efforts aimed at patient education (both as general consumers as well as at the point of care)

- Malpractice reform to support physicians trying to balance cost consciousness with patient welfare

In Sum

We have a long way to go in engaging physicians in efforts to reduce unnecessary utilization and cost. I recommend that hospitalist practices utilize the survey tool used in this study to understand the perceived barriers and drivers of cost within their practice and work with their local administrative teams to better understand patterns of overutilization among their group. Then interventions can be designed to be evidence-based, tailored to local workflow, and both reliable and sustainable.

If done well, hospitalists can have a huge impact on utilization and cost and position their groups and their hospitals well to succeed in this cost-constrained era of healthcare. TH

References

- Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perception of Choosing Wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337-343.

The healthcare industry is under major stress from steady declines in all sources of revenue. The drivers are multifactorial but include declining reimbursement from payors, a shift from fee-for-service to pay-for-performance, and state-by-state variability in patients covered by Medicaid, by high-deductible plans, or by being uninsured. In academic medical centers, rising overhead costs coupled with a reticence to raise student tuition and declining research funding streams have further compounded the situation.

Regardless of the actual numbers, all healthcare institutions are feeling the financial pinch. Most are intensely focused on cost-reduction efforts. The question is, what do physicians think about their role in these efforts, and what efforts will be most effective?

A recent survey of a large physician group practice found that many physicians do not know what their cost drivers are or do not think it is their role to participate in cost-reduction efforts.1 Of note, the group practice in the survey is a Pioneer Medicare accountable care organization (ACO) and participates in a combination of fee-for-service and capitated contracts.

Within the survey, the researchers embedded a cost-consciousness scale, which is a validated survey tool designed to assess daily cost consciousness. They also embedded other survey items to determine the physicians’ concerns for malpractice, comfort with diagnostic uncertainty, and perception of patient-family pressure for utilization of services. The average overall cost-consciousness score was 29 out of 44, with higher scores indicating more cost consciousness.

Almost all physicians agreed that they need to reduce unnecessary testing (97%), need to adhere to guidelines (98%), and have a responsibility to control costs (92%). However, 33% felt it was unfair for them to have to be both cost-conscious and concerned with the welfare of their patients.

Approximately a third of respondents also felt that there was too much emphasis on cost and that physicians are too busy to worry about costs.

More than a third (37%) said they did not have good knowledge about test-procedure cost within their system.

More than half of physicians felt pressure from patients to perform tests and procedures (from 68% of primary-care physicians, 58% of medical specialists, and 56% of surgical specialists) and felt pressure to refer to consultants (from 65% of primary-care physicians, 35% of medical specialists, and 34% of surgical specialists).

Based on this survey and other literature about physicians’ perceptions of their role and their ability to control costs, it is clear that the first step in understanding how to engage physicians in cost-reducing efforts is to understand what the drivers are for utilization and what the concerns are for reducing cost. Many hypothesize that the drivers to support the status quo include a fear of litigation, fear of missing a diagnosis, and patient demands for services. Another major driver of current utilization is that there is ongoing support for the status quo, as the majority of reimbursement for providers is still based on fee-for-service.

Change Efforts

One cost-reducing effort that has gained widespread enthusiasm from medical societies is the Choosing Wisely campaign. This campaign is an effort originally driven by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation to help physicians become aware of and reduce unnecessary utilization of resources. Each Choosing Wisely list is generated and endorsed by the relevant medical society and widely advertised to physicians via a variety of mechanisms. More than 70 medical societies have participated in the effort to date.

The recommendations are often widely accepted by those in the specialty since they are evidence-based and derived and advertised by their own specialty societies. In the survey mentioned above, almost all physicians agreed that their Choosing Wisely was a good source of guidance (ranging from 92% of surgical specialties to 97% of primary-care physicians). In order to drive the movement from the patient perspective, Consumer Reports has developed educational materials aimed at the consumer side of healthcare (ie, patients and families).

As Consumer Reports suggests, the first step to implementing cost-conscious care is to measure awareness of cost and causes of overutilization. By first understanding behaviors, a group can then work to impact such behaviors. It is highly likely that the drivers are different based on the specialty of the physician, the patient population being served, and the local healthcare market drivers. As such, there will not be a single, across-the-board solution to reducing unnecessary utilization of services (and therefore cost), but interventions will need to be tailored to different groups depending on the drivers of cost locally.

Depending on the issues within a group, successful interventions could include:

- Decision support tools (for appropriate use of consultants and diagnostic tests)

- Display of testing costs (not just at the time of ordering)

- Efforts aimed at patient education (both as general consumers as well as at the point of care)

- Malpractice reform to support physicians trying to balance cost consciousness with patient welfare

In Sum

We have a long way to go in engaging physicians in efforts to reduce unnecessary utilization and cost. I recommend that hospitalist practices utilize the survey tool used in this study to understand the perceived barriers and drivers of cost within their practice and work with their local administrative teams to better understand patterns of overutilization among their group. Then interventions can be designed to be evidence-based, tailored to local workflow, and both reliable and sustainable.

If done well, hospitalists can have a huge impact on utilization and cost and position their groups and their hospitals well to succeed in this cost-constrained era of healthcare. TH

References

- Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perception of Choosing Wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337-343.

The healthcare industry is under major stress from steady declines in all sources of revenue. The drivers are multifactorial but include declining reimbursement from payors, a shift from fee-for-service to pay-for-performance, and state-by-state variability in patients covered by Medicaid, by high-deductible plans, or by being uninsured. In academic medical centers, rising overhead costs coupled with a reticence to raise student tuition and declining research funding streams have further compounded the situation.

Regardless of the actual numbers, all healthcare institutions are feeling the financial pinch. Most are intensely focused on cost-reduction efforts. The question is, what do physicians think about their role in these efforts, and what efforts will be most effective?

A recent survey of a large physician group practice found that many physicians do not know what their cost drivers are or do not think it is their role to participate in cost-reduction efforts.1 Of note, the group practice in the survey is a Pioneer Medicare accountable care organization (ACO) and participates in a combination of fee-for-service and capitated contracts.

Within the survey, the researchers embedded a cost-consciousness scale, which is a validated survey tool designed to assess daily cost consciousness. They also embedded other survey items to determine the physicians’ concerns for malpractice, comfort with diagnostic uncertainty, and perception of patient-family pressure for utilization of services. The average overall cost-consciousness score was 29 out of 44, with higher scores indicating more cost consciousness.

Almost all physicians agreed that they need to reduce unnecessary testing (97%), need to adhere to guidelines (98%), and have a responsibility to control costs (92%). However, 33% felt it was unfair for them to have to be both cost-conscious and concerned with the welfare of their patients.

Approximately a third of respondents also felt that there was too much emphasis on cost and that physicians are too busy to worry about costs.

More than a third (37%) said they did not have good knowledge about test-procedure cost within their system.