User login

What’s on the dermatopathologist’s wish list

NEW YORK – If dermatopathologists had a wish list they could give their dermatologist colleagues, what might it include? High up on the list for many, said Robert Phelps, MD, might be to have them share the clinical picture, treat the specimen gently, and give the best landmarks possible.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Phelps, director of the dermatopathology service at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, led off the dermatopathologist-run session – appropriately titled “Help Me Help You” – by asking, “How can the clinician provide the optimal biopsy?”

It’s always helpful to have as much clinical information as possible, said Dr. Phelps, whose discussion focused on tips for neoplastic lesions. This might include prior history of malignancy, autoimmune disease, pathergy, or other relevant medical history, but clinical pictures can also be a big help, although there can be technical and patient privacy issues to overcome, he noted. If, for example, a larger lesion or rash is being biopsied rather than excised, it can be very helpful to see the larger field and full area of distribution of the lesion in question. Submitting multiple specimens for rashes and larger lesions is always a good idea too, he added.

Although curettage can be a great way to biopsy – and perhaps even definitively treat some lesions – problems can arise on the dermatopathologist’s side when melanocytic lesions are curetted for biopsy, according to Dr. Phelps, a practicing dermatologist and a dermatopathologist. “By virtue of the force of the biopsy, the specimen is often fragmented, and histology can be distorted,” he said. One element of that distortion can be that melanocytes can appear to be free floating, which is a problem. “Dyshesion of melanocytes is usually an indication of atypia … It is an important histologic clue as to the possibility of a malignancy supervening.”

These factors can make it tough for a dermatopathologist to make an accurate call. “If there are free-floating melanocytes from a curetted specimen, I can’t rule out invasive melanoma,” explained Dr. Phelps, since he can’t tell if he is seeing true atypia or disruption that’s an artifact of the collection technique.

In this instance, he said, a dermatopathologist would be “obligated to overcall, because one couldn’t really determine the pathology.” The bottom line? “Don’t curette biopsies of melanocytic lesions.”

Another technique that can interfere with the ability to read a tissue specimen accurately is electrodesiccation. Although it’s often performed in conjunction with curettage, electrodesiccation can cause changes in tissue consistent with thermal injury. “Essentially, the tissue has been burned,” Dr. Phelps pointed out. This can result in a characteristic streaming pattern of nuclei, and the dermis can acquire a “peculiar homogenized appearance,” he said.

Although electrodesiccation can be a useful technique to make sure margins are controlled, “when you do this, just be aware that the interpretation is difficult,” he noted. “It’s difficult to tell where the margins are and if they are the appropriate and correct margins,” he said.

When possible, try to avoid squeezing the tumor, Dr. Phelps advised. Excessive pressure on the specimen can distort cell architecture and make pathological diagnosis really challenging, particularly in lymphoid tumors, he said.

“Often, the tumor is not recognizable,” he added. Crush artifact can result in an appearance of small bluish clumps and smearing of collagen fibers. The effect, he said, can be particularly pronounced with small cell carcinoma and lymphoma, and with rapidly proliferating tumors.

Dr. Phelps said that during his training, he was taught not to use forceps to extract a stubborn punch biopsy specimen; rather, he was trained to use a needle to tease out the specimen. Fear of a self-inflicted needle stick with this technique may be a deterrent, he acknowledged. If forceps are used, he suggested being as gentle as possible and using the finest forceps available.

When pathologists receive an intact excised lesion – one not obtained using a Mohs technique, “delineation of the margin is essential,” Dr. Phelps said. Further, accurate mapping is critical to helping the examiner understand the anatomic orientation of the specimen, a key prerequisite that enables accurate communication from the dermatopathologist back to the clinician if there’s a question regarding the need for retreatment, he added.

For an elliptical excision, ideally, both poles of the ellipse would be suture-tagged, and at least one tag is essential, he said. Then superior and inferior borders can be inked with contrasting colors, and the epidermal borders of the lesion should be marked as well. When the specimen is submitted, it should be accompanied by an accurate map that clearly indicates the coding for medial, lateral, inferior, and superior aspects of the specimen. “Always prepare a specimen diagram for oriented specimens,” Dr. Phelps noted.

Don’t forget to make sure that the left-right orientation on the diagram corresponds to the specimen’s orientation on the patient, he added. Some facilities use a clock face system to indicate orientation and positioning, which may be the clearest method of all.

Sometimes, it’s difficult for the dermatopathologist to visualize whether the specimen is aligned in true medial-lateral fashion, or along skin tension lines, which tend to run diagonally, so “the more clinical information, the better,” he said. “With good mapping, precise retreatment can be optimal,” he said.

Dr. Phelps reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – If dermatopathologists had a wish list they could give their dermatologist colleagues, what might it include? High up on the list for many, said Robert Phelps, MD, might be to have them share the clinical picture, treat the specimen gently, and give the best landmarks possible.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Phelps, director of the dermatopathology service at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, led off the dermatopathologist-run session – appropriately titled “Help Me Help You” – by asking, “How can the clinician provide the optimal biopsy?”

It’s always helpful to have as much clinical information as possible, said Dr. Phelps, whose discussion focused on tips for neoplastic lesions. This might include prior history of malignancy, autoimmune disease, pathergy, or other relevant medical history, but clinical pictures can also be a big help, although there can be technical and patient privacy issues to overcome, he noted. If, for example, a larger lesion or rash is being biopsied rather than excised, it can be very helpful to see the larger field and full area of distribution of the lesion in question. Submitting multiple specimens for rashes and larger lesions is always a good idea too, he added.

Although curettage can be a great way to biopsy – and perhaps even definitively treat some lesions – problems can arise on the dermatopathologist’s side when melanocytic lesions are curetted for biopsy, according to Dr. Phelps, a practicing dermatologist and a dermatopathologist. “By virtue of the force of the biopsy, the specimen is often fragmented, and histology can be distorted,” he said. One element of that distortion can be that melanocytes can appear to be free floating, which is a problem. “Dyshesion of melanocytes is usually an indication of atypia … It is an important histologic clue as to the possibility of a malignancy supervening.”

These factors can make it tough for a dermatopathologist to make an accurate call. “If there are free-floating melanocytes from a curetted specimen, I can’t rule out invasive melanoma,” explained Dr. Phelps, since he can’t tell if he is seeing true atypia or disruption that’s an artifact of the collection technique.

In this instance, he said, a dermatopathologist would be “obligated to overcall, because one couldn’t really determine the pathology.” The bottom line? “Don’t curette biopsies of melanocytic lesions.”

Another technique that can interfere with the ability to read a tissue specimen accurately is electrodesiccation. Although it’s often performed in conjunction with curettage, electrodesiccation can cause changes in tissue consistent with thermal injury. “Essentially, the tissue has been burned,” Dr. Phelps pointed out. This can result in a characteristic streaming pattern of nuclei, and the dermis can acquire a “peculiar homogenized appearance,” he said.

Although electrodesiccation can be a useful technique to make sure margins are controlled, “when you do this, just be aware that the interpretation is difficult,” he noted. “It’s difficult to tell where the margins are and if they are the appropriate and correct margins,” he said.

When possible, try to avoid squeezing the tumor, Dr. Phelps advised. Excessive pressure on the specimen can distort cell architecture and make pathological diagnosis really challenging, particularly in lymphoid tumors, he said.

“Often, the tumor is not recognizable,” he added. Crush artifact can result in an appearance of small bluish clumps and smearing of collagen fibers. The effect, he said, can be particularly pronounced with small cell carcinoma and lymphoma, and with rapidly proliferating tumors.

Dr. Phelps said that during his training, he was taught not to use forceps to extract a stubborn punch biopsy specimen; rather, he was trained to use a needle to tease out the specimen. Fear of a self-inflicted needle stick with this technique may be a deterrent, he acknowledged. If forceps are used, he suggested being as gentle as possible and using the finest forceps available.

When pathologists receive an intact excised lesion – one not obtained using a Mohs technique, “delineation of the margin is essential,” Dr. Phelps said. Further, accurate mapping is critical to helping the examiner understand the anatomic orientation of the specimen, a key prerequisite that enables accurate communication from the dermatopathologist back to the clinician if there’s a question regarding the need for retreatment, he added.

For an elliptical excision, ideally, both poles of the ellipse would be suture-tagged, and at least one tag is essential, he said. Then superior and inferior borders can be inked with contrasting colors, and the epidermal borders of the lesion should be marked as well. When the specimen is submitted, it should be accompanied by an accurate map that clearly indicates the coding for medial, lateral, inferior, and superior aspects of the specimen. “Always prepare a specimen diagram for oriented specimens,” Dr. Phelps noted.

Don’t forget to make sure that the left-right orientation on the diagram corresponds to the specimen’s orientation on the patient, he added. Some facilities use a clock face system to indicate orientation and positioning, which may be the clearest method of all.

Sometimes, it’s difficult for the dermatopathologist to visualize whether the specimen is aligned in true medial-lateral fashion, or along skin tension lines, which tend to run diagonally, so “the more clinical information, the better,” he said. “With good mapping, precise retreatment can be optimal,” he said.

Dr. Phelps reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – If dermatopathologists had a wish list they could give their dermatologist colleagues, what might it include? High up on the list for many, said Robert Phelps, MD, might be to have them share the clinical picture, treat the specimen gently, and give the best landmarks possible.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Phelps, director of the dermatopathology service at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, led off the dermatopathologist-run session – appropriately titled “Help Me Help You” – by asking, “How can the clinician provide the optimal biopsy?”

It’s always helpful to have as much clinical information as possible, said Dr. Phelps, whose discussion focused on tips for neoplastic lesions. This might include prior history of malignancy, autoimmune disease, pathergy, or other relevant medical history, but clinical pictures can also be a big help, although there can be technical and patient privacy issues to overcome, he noted. If, for example, a larger lesion or rash is being biopsied rather than excised, it can be very helpful to see the larger field and full area of distribution of the lesion in question. Submitting multiple specimens for rashes and larger lesions is always a good idea too, he added.

Although curettage can be a great way to biopsy – and perhaps even definitively treat some lesions – problems can arise on the dermatopathologist’s side when melanocytic lesions are curetted for biopsy, according to Dr. Phelps, a practicing dermatologist and a dermatopathologist. “By virtue of the force of the biopsy, the specimen is often fragmented, and histology can be distorted,” he said. One element of that distortion can be that melanocytes can appear to be free floating, which is a problem. “Dyshesion of melanocytes is usually an indication of atypia … It is an important histologic clue as to the possibility of a malignancy supervening.”

These factors can make it tough for a dermatopathologist to make an accurate call. “If there are free-floating melanocytes from a curetted specimen, I can’t rule out invasive melanoma,” explained Dr. Phelps, since he can’t tell if he is seeing true atypia or disruption that’s an artifact of the collection technique.

In this instance, he said, a dermatopathologist would be “obligated to overcall, because one couldn’t really determine the pathology.” The bottom line? “Don’t curette biopsies of melanocytic lesions.”

Another technique that can interfere with the ability to read a tissue specimen accurately is electrodesiccation. Although it’s often performed in conjunction with curettage, electrodesiccation can cause changes in tissue consistent with thermal injury. “Essentially, the tissue has been burned,” Dr. Phelps pointed out. This can result in a characteristic streaming pattern of nuclei, and the dermis can acquire a “peculiar homogenized appearance,” he said.

Although electrodesiccation can be a useful technique to make sure margins are controlled, “when you do this, just be aware that the interpretation is difficult,” he noted. “It’s difficult to tell where the margins are and if they are the appropriate and correct margins,” he said.

When possible, try to avoid squeezing the tumor, Dr. Phelps advised. Excessive pressure on the specimen can distort cell architecture and make pathological diagnosis really challenging, particularly in lymphoid tumors, he said.

“Often, the tumor is not recognizable,” he added. Crush artifact can result in an appearance of small bluish clumps and smearing of collagen fibers. The effect, he said, can be particularly pronounced with small cell carcinoma and lymphoma, and with rapidly proliferating tumors.

Dr. Phelps said that during his training, he was taught not to use forceps to extract a stubborn punch biopsy specimen; rather, he was trained to use a needle to tease out the specimen. Fear of a self-inflicted needle stick with this technique may be a deterrent, he acknowledged. If forceps are used, he suggested being as gentle as possible and using the finest forceps available.

When pathologists receive an intact excised lesion – one not obtained using a Mohs technique, “delineation of the margin is essential,” Dr. Phelps said. Further, accurate mapping is critical to helping the examiner understand the anatomic orientation of the specimen, a key prerequisite that enables accurate communication from the dermatopathologist back to the clinician if there’s a question regarding the need for retreatment, he added.

For an elliptical excision, ideally, both poles of the ellipse would be suture-tagged, and at least one tag is essential, he said. Then superior and inferior borders can be inked with contrasting colors, and the epidermal borders of the lesion should be marked as well. When the specimen is submitted, it should be accompanied by an accurate map that clearly indicates the coding for medial, lateral, inferior, and superior aspects of the specimen. “Always prepare a specimen diagram for oriented specimens,” Dr. Phelps noted.

Don’t forget to make sure that the left-right orientation on the diagram corresponds to the specimen’s orientation on the patient, he added. Some facilities use a clock face system to indicate orientation and positioning, which may be the clearest method of all.

Sometimes, it’s difficult for the dermatopathologist to visualize whether the specimen is aligned in true medial-lateral fashion, or along skin tension lines, which tend to run diagonally, so “the more clinical information, the better,” he said. “With good mapping, precise retreatment can be optimal,” he said.

Dr. Phelps reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

When – and how – to do a full-thickness graft repair

NEW YORK – Though flap reconstruction can provide elegant solutions with very good cosmesis after Mohs surgery and other excisional procedures, skin grafts provide another set of options.

Both split and full thickness grafts have a place in the dermatologist’s repertoire, but some tips and tricks can make a full thickness graft an attractive option in many instances, according to Marc Brown, MD, professor of dermatology and oncology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Brown said that retrospective studies have shown that patients are highly satisfied with the cosmesis of full thickness skin grafting for reconstruction post Mohs surgery – if they’re asked after enough time has passed for the graft to mature and the dermatologist to perform some of the tweaks that are occasionally necessary. “It takes time to get to that point, but the overall satisfaction improves over time,” he said.

Full thickness skin grafts may be a good option when flap coverage is suboptimal or infeasible, he said. Some other pros of opting for a full thickness graft are that better cosmesis can be achieved in certain cases, and the donor site can be sutured, allowing for quicker healing with less downtime. However, a full thickness graft is a thicker graft, with resulting high metabolic demand. To ensure good “take,” dermatologists must be mindful that the graft site has a good vascular supply. Also, he added, full thickness grafts often need thinning, and physicians shouldn’t be afraid of being aggressive.

Both to reduce unwanted bulk and to help with better graft take, subcutaneous fat should be stripped completely from the graft, Dr. Brown noted. “You should see nothing that looks yellow,” he said. Fine serrated scissors are an excellent defatting tool, and while expensive, “they’re worth the cost,” he added.

Areas to be considered for full thickness grafts include the nasal ala, the medial canthus of the eye, the upper eyelid, fingers, and the ear. Larger defects on the scalp or forehead may also be good candidates, and full thickness grafts can work well on the lower leg.

For smaller grafts – those less than 1 or 2 cm diameter – Dr. Brown said that the preauricular area can work well as a donor site for facial grafts, since there’s often extra tissue with little tension there. Patients who are worried about donor site cosmesis may prefer the postauricular area, though the result is usually very good in either case, he said. Other potential donor sites are the glabella, nasolabial area, and the eyelid.

When grafts of more than 2 cm diameter are needed, Dr. Brown said the lateral neck, the supraclavicular area, or the lateral chest area can provide a good match in color and texture to facial skin.

Other tips for surgical technique are to use an appropriately-sized nonadherent gauze pad as a template for exact graft sizing. Precision counts, said Dr. Brown: “Measure twice, cut once.”

A central basting suture can be used to hold the graft in place while getting started, and Dr. Brown often uses a bolster for grafts of less than 1 cm. “Bolsters are helpful to prevent bleeding and improve contact in larger grafts,” he added.

Sutures should be placed graft to skin – “up and under,” Dr. Brown noted. He uses rapid-absorbing chromic suture material, with silk on the outside for the tie-over bolster. It’s also important to avoid tension on the wound edge, and he advised always using a pressure bandage for 48-72 hours.

If there’s concern about blood supply when grafting over cartilage, Dr. Brown advises making a few 2-mm punch defects in the cartilage to boost blood supply and help with engraftment.

For larger grafts where hematoma formation might result in graft failure, he will place a few parallel incisions through the graft as a means of escape should there be significant bleeding. At about 1 week post procedure, the graft should be purplish-pink in color, and patients should be counseled about the appearance of the graft as healing progresses, he said.

Physicians can manage patient expectations by letting them know not to expect the best cosmesis right away. However, said Dr. Brown, if the graft remains thickened, there are lots of options. Intralesional triamcinolone injections can help with thinning, and can be used beginning about 3 months after the graft. Dermabrasion is another good option, but he likes to wait 4-6 months before performing this procedure.

With appropriate site selection, meticulous technique, and good patient communication, dermatologists can keep full thickness skin grafting in the repertoire of viable options for excellent cosmesis, and a valuable tool in their own right. “Skin grafts are not a failure of reconstruction,” Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no conflicts to disclose.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Though flap reconstruction can provide elegant solutions with very good cosmesis after Mohs surgery and other excisional procedures, skin grafts provide another set of options.

Both split and full thickness grafts have a place in the dermatologist’s repertoire, but some tips and tricks can make a full thickness graft an attractive option in many instances, according to Marc Brown, MD, professor of dermatology and oncology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Brown said that retrospective studies have shown that patients are highly satisfied with the cosmesis of full thickness skin grafting for reconstruction post Mohs surgery – if they’re asked after enough time has passed for the graft to mature and the dermatologist to perform some of the tweaks that are occasionally necessary. “It takes time to get to that point, but the overall satisfaction improves over time,” he said.

Full thickness skin grafts may be a good option when flap coverage is suboptimal or infeasible, he said. Some other pros of opting for a full thickness graft are that better cosmesis can be achieved in certain cases, and the donor site can be sutured, allowing for quicker healing with less downtime. However, a full thickness graft is a thicker graft, with resulting high metabolic demand. To ensure good “take,” dermatologists must be mindful that the graft site has a good vascular supply. Also, he added, full thickness grafts often need thinning, and physicians shouldn’t be afraid of being aggressive.

Both to reduce unwanted bulk and to help with better graft take, subcutaneous fat should be stripped completely from the graft, Dr. Brown noted. “You should see nothing that looks yellow,” he said. Fine serrated scissors are an excellent defatting tool, and while expensive, “they’re worth the cost,” he added.

Areas to be considered for full thickness grafts include the nasal ala, the medial canthus of the eye, the upper eyelid, fingers, and the ear. Larger defects on the scalp or forehead may also be good candidates, and full thickness grafts can work well on the lower leg.

For smaller grafts – those less than 1 or 2 cm diameter – Dr. Brown said that the preauricular area can work well as a donor site for facial grafts, since there’s often extra tissue with little tension there. Patients who are worried about donor site cosmesis may prefer the postauricular area, though the result is usually very good in either case, he said. Other potential donor sites are the glabella, nasolabial area, and the eyelid.

When grafts of more than 2 cm diameter are needed, Dr. Brown said the lateral neck, the supraclavicular area, or the lateral chest area can provide a good match in color and texture to facial skin.

Other tips for surgical technique are to use an appropriately-sized nonadherent gauze pad as a template for exact graft sizing. Precision counts, said Dr. Brown: “Measure twice, cut once.”

A central basting suture can be used to hold the graft in place while getting started, and Dr. Brown often uses a bolster for grafts of less than 1 cm. “Bolsters are helpful to prevent bleeding and improve contact in larger grafts,” he added.

Sutures should be placed graft to skin – “up and under,” Dr. Brown noted. He uses rapid-absorbing chromic suture material, with silk on the outside for the tie-over bolster. It’s also important to avoid tension on the wound edge, and he advised always using a pressure bandage for 48-72 hours.

If there’s concern about blood supply when grafting over cartilage, Dr. Brown advises making a few 2-mm punch defects in the cartilage to boost blood supply and help with engraftment.

For larger grafts where hematoma formation might result in graft failure, he will place a few parallel incisions through the graft as a means of escape should there be significant bleeding. At about 1 week post procedure, the graft should be purplish-pink in color, and patients should be counseled about the appearance of the graft as healing progresses, he said.

Physicians can manage patient expectations by letting them know not to expect the best cosmesis right away. However, said Dr. Brown, if the graft remains thickened, there are lots of options. Intralesional triamcinolone injections can help with thinning, and can be used beginning about 3 months after the graft. Dermabrasion is another good option, but he likes to wait 4-6 months before performing this procedure.

With appropriate site selection, meticulous technique, and good patient communication, dermatologists can keep full thickness skin grafting in the repertoire of viable options for excellent cosmesis, and a valuable tool in their own right. “Skin grafts are not a failure of reconstruction,” Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no conflicts to disclose.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Though flap reconstruction can provide elegant solutions with very good cosmesis after Mohs surgery and other excisional procedures, skin grafts provide another set of options.

Both split and full thickness grafts have a place in the dermatologist’s repertoire, but some tips and tricks can make a full thickness graft an attractive option in many instances, according to Marc Brown, MD, professor of dermatology and oncology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Brown said that retrospective studies have shown that patients are highly satisfied with the cosmesis of full thickness skin grafting for reconstruction post Mohs surgery – if they’re asked after enough time has passed for the graft to mature and the dermatologist to perform some of the tweaks that are occasionally necessary. “It takes time to get to that point, but the overall satisfaction improves over time,” he said.

Full thickness skin grafts may be a good option when flap coverage is suboptimal or infeasible, he said. Some other pros of opting for a full thickness graft are that better cosmesis can be achieved in certain cases, and the donor site can be sutured, allowing for quicker healing with less downtime. However, a full thickness graft is a thicker graft, with resulting high metabolic demand. To ensure good “take,” dermatologists must be mindful that the graft site has a good vascular supply. Also, he added, full thickness grafts often need thinning, and physicians shouldn’t be afraid of being aggressive.

Both to reduce unwanted bulk and to help with better graft take, subcutaneous fat should be stripped completely from the graft, Dr. Brown noted. “You should see nothing that looks yellow,” he said. Fine serrated scissors are an excellent defatting tool, and while expensive, “they’re worth the cost,” he added.

Areas to be considered for full thickness grafts include the nasal ala, the medial canthus of the eye, the upper eyelid, fingers, and the ear. Larger defects on the scalp or forehead may also be good candidates, and full thickness grafts can work well on the lower leg.

For smaller grafts – those less than 1 or 2 cm diameter – Dr. Brown said that the preauricular area can work well as a donor site for facial grafts, since there’s often extra tissue with little tension there. Patients who are worried about donor site cosmesis may prefer the postauricular area, though the result is usually very good in either case, he said. Other potential donor sites are the glabella, nasolabial area, and the eyelid.

When grafts of more than 2 cm diameter are needed, Dr. Brown said the lateral neck, the supraclavicular area, or the lateral chest area can provide a good match in color and texture to facial skin.

Other tips for surgical technique are to use an appropriately-sized nonadherent gauze pad as a template for exact graft sizing. Precision counts, said Dr. Brown: “Measure twice, cut once.”

A central basting suture can be used to hold the graft in place while getting started, and Dr. Brown often uses a bolster for grafts of less than 1 cm. “Bolsters are helpful to prevent bleeding and improve contact in larger grafts,” he added.

Sutures should be placed graft to skin – “up and under,” Dr. Brown noted. He uses rapid-absorbing chromic suture material, with silk on the outside for the tie-over bolster. It’s also important to avoid tension on the wound edge, and he advised always using a pressure bandage for 48-72 hours.

If there’s concern about blood supply when grafting over cartilage, Dr. Brown advises making a few 2-mm punch defects in the cartilage to boost blood supply and help with engraftment.

For larger grafts where hematoma formation might result in graft failure, he will place a few parallel incisions through the graft as a means of escape should there be significant bleeding. At about 1 week post procedure, the graft should be purplish-pink in color, and patients should be counseled about the appearance of the graft as healing progresses, he said.

Physicians can manage patient expectations by letting them know not to expect the best cosmesis right away. However, said Dr. Brown, if the graft remains thickened, there are lots of options. Intralesional triamcinolone injections can help with thinning, and can be used beginning about 3 months after the graft. Dermabrasion is another good option, but he likes to wait 4-6 months before performing this procedure.

With appropriate site selection, meticulous technique, and good patient communication, dermatologists can keep full thickness skin grafting in the repertoire of viable options for excellent cosmesis, and a valuable tool in their own right. “Skin grafts are not a failure of reconstruction,” Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no conflicts to disclose.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM the 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

When the painful ‘bumps’ are calciphylaxis, what’s next?

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

NEW YORK – When patients come to the office with painful “bumps” on the legs or elsewhere, panniculitis should be in the differential. And for some patients, said Alina Bridges, DO, the panniculitis may come with the dire diagnosis of calciphylaxis.

Calciphylaxis is an underrecognized crystal deposition disease that’s associated with panniculitis, said Dr. Bridges, speaking at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. When calcium accumulates in small subcutaneous vessels, an occlusive vasculopathy is created within the dermis.

A soft-tissue radiograph of the affected area may also be helpful. Calciphylaxis shows as a fine netlike pattern of calcification, a finding that Dr. Bridges said has 90% specificity for the condition.

However, Dr. Bridges said, patients with panniculitis need a biopsy. “Careful selection of biopsy site and a deep specimen containing abundant fat obtained by incisional or excisional biopsy” is the best approach, allowing the pathologist to see the complete picture. In some cases, she said, a double-punch biopsy could also produce adequate specimens.

In addition to the calcium deposition, other pathologic findings may be lobular fat necrosis, with a pannicular vascular thrombosis. Though extravascular calcification can be seen in the panniculus, it’s not uncommon also to see intravascular calcification, said Dr. Bridges, who is the dermatopathology fellowship program director at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

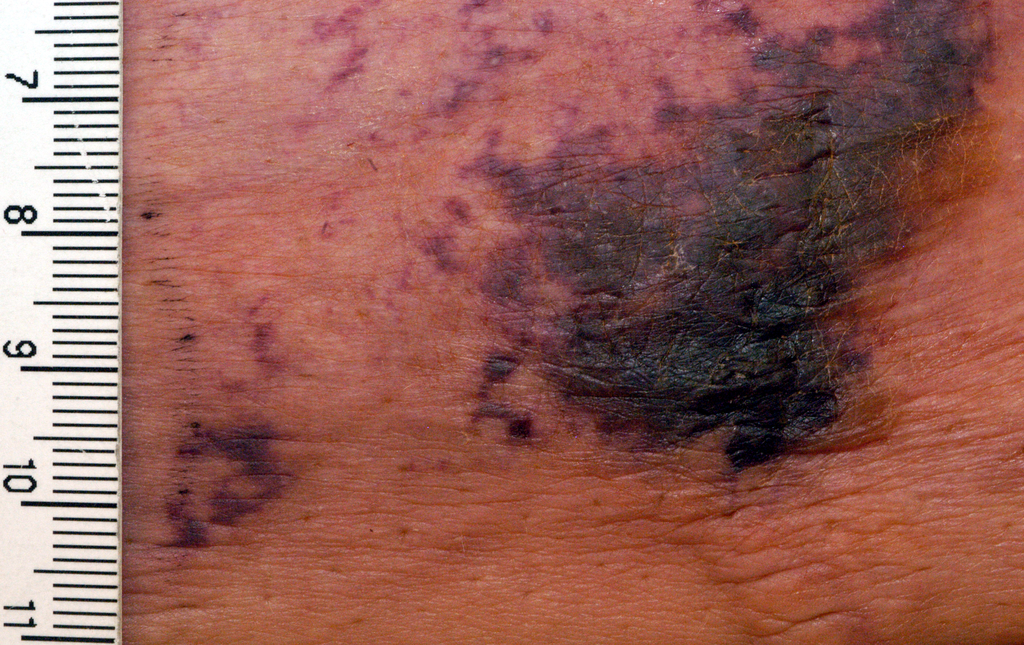

Dr. Bridges said that the patients with calciphylaxis can present with predominant panniculitis or vasculitis, or a mixed picture; patients can also have bullae, ulcers, or livedo reticularis.

The lesions are extremely painful and become increasingly violaceous, with firm subcutaneous nodules. They are variably necrotic, and become more ulcerated over time.

Calciphylaxis is multifactorial and progressive. The prognosis is very poor for individuals with the condition, Dr. Bridges said. The median survival is 10 months, with 1-year survival rates of 46%, and just 20% of individuals with calciphylaxis surviving 2 years after diagnosis.

Gangrene is a frequent complication, and multisystem organ failure often occurs as well, she said.

Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in individuals with chronic kidney disease and is seen in 4% of hemodialysis patients. However, it may also occur in individuals without uremia. In associations that are incompletely understood, calciphylaxis has been associated with warfarin therapy, connective tissue disorders, Crohn’s disease, liver disease, diabetes, hematologic malignancies, factor V Leiden deficiency, and protein C and S deficiency.

There’s a need for clinical suspicion of calciphylaxis when individuals with any of these conditions present with painful erythematous nodules, or with a vasculitic picture, she said.

Other, more common crystal deposition diseases can also be associated with panniculitis and can be in the differential, Dr. Bridges said. In patients with gout, sodium urate crystal deposition can occur in subcutaneous tissues.

Cutaneous oxalosis can occur as a primary disorder, when patients have metabolic errors and lack alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase or D-glycerate dehydrogenase. Oxalosis can also be an acquired syndrome in patients with chronic renal failure who have been on long-term hemodialysis.

Although there is not a clearly effective treatment for calciphylaxis, a multitargeted, multidisciplinary approach is needed to help improve tissue health and patient quality of life. Since the primary mechanism of tissue damage is thrombotic tissue ischemia, strategies are aimed at existing clots and at preventing further clot formation.

To correct the calcium-phosphate balance, several medications have been used, including sodium thiosulfate and cinacalcet. For individuals on hemodialysis, a low-calcium dialysate may be used.

Tissue perfusion and oxygenation can be improved using tissue plasminogen activator, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and the avoidance of warfarin if the patient requires anticoagulation.

To address wounds directly, debridement can begin with whirlpool time for patients. Surgical debridement may be required, and maggots can also help clean up wound beds.

Palliative care for patients should always include optimizing pain control and improving quality of life for patients with this serious and often life-limiting condition, Dr. Bridges said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

NEW YORK – When patients come to the office with painful “bumps” on the legs or elsewhere, panniculitis should be in the differential. And for some patients, said Alina Bridges, DO, the panniculitis may come with the dire diagnosis of calciphylaxis.

Calciphylaxis is an underrecognized crystal deposition disease that’s associated with panniculitis, said Dr. Bridges, speaking at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. When calcium accumulates in small subcutaneous vessels, an occlusive vasculopathy is created within the dermis.

A soft-tissue radiograph of the affected area may also be helpful. Calciphylaxis shows as a fine netlike pattern of calcification, a finding that Dr. Bridges said has 90% specificity for the condition.

However, Dr. Bridges said, patients with panniculitis need a biopsy. “Careful selection of biopsy site and a deep specimen containing abundant fat obtained by incisional or excisional biopsy” is the best approach, allowing the pathologist to see the complete picture. In some cases, she said, a double-punch biopsy could also produce adequate specimens.

In addition to the calcium deposition, other pathologic findings may be lobular fat necrosis, with a pannicular vascular thrombosis. Though extravascular calcification can be seen in the panniculus, it’s not uncommon also to see intravascular calcification, said Dr. Bridges, who is the dermatopathology fellowship program director at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Bridges said that the patients with calciphylaxis can present with predominant panniculitis or vasculitis, or a mixed picture; patients can also have bullae, ulcers, or livedo reticularis.

The lesions are extremely painful and become increasingly violaceous, with firm subcutaneous nodules. They are variably necrotic, and become more ulcerated over time.

Calciphylaxis is multifactorial and progressive. The prognosis is very poor for individuals with the condition, Dr. Bridges said. The median survival is 10 months, with 1-year survival rates of 46%, and just 20% of individuals with calciphylaxis surviving 2 years after diagnosis.

Gangrene is a frequent complication, and multisystem organ failure often occurs as well, she said.

Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in individuals with chronic kidney disease and is seen in 4% of hemodialysis patients. However, it may also occur in individuals without uremia. In associations that are incompletely understood, calciphylaxis has been associated with warfarin therapy, connective tissue disorders, Crohn’s disease, liver disease, diabetes, hematologic malignancies, factor V Leiden deficiency, and protein C and S deficiency.

There’s a need for clinical suspicion of calciphylaxis when individuals with any of these conditions present with painful erythematous nodules, or with a vasculitic picture, she said.

Other, more common crystal deposition diseases can also be associated with panniculitis and can be in the differential, Dr. Bridges said. In patients with gout, sodium urate crystal deposition can occur in subcutaneous tissues.

Cutaneous oxalosis can occur as a primary disorder, when patients have metabolic errors and lack alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase or D-glycerate dehydrogenase. Oxalosis can also be an acquired syndrome in patients with chronic renal failure who have been on long-term hemodialysis.

Although there is not a clearly effective treatment for calciphylaxis, a multitargeted, multidisciplinary approach is needed to help improve tissue health and patient quality of life. Since the primary mechanism of tissue damage is thrombotic tissue ischemia, strategies are aimed at existing clots and at preventing further clot formation.

To correct the calcium-phosphate balance, several medications have been used, including sodium thiosulfate and cinacalcet. For individuals on hemodialysis, a low-calcium dialysate may be used.

Tissue perfusion and oxygenation can be improved using tissue plasminogen activator, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and the avoidance of warfarin if the patient requires anticoagulation.

To address wounds directly, debridement can begin with whirlpool time for patients. Surgical debridement may be required, and maggots can also help clean up wound beds.

Palliative care for patients should always include optimizing pain control and improving quality of life for patients with this serious and often life-limiting condition, Dr. Bridges said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

NEW YORK – When patients come to the office with painful “bumps” on the legs or elsewhere, panniculitis should be in the differential. And for some patients, said Alina Bridges, DO, the panniculitis may come with the dire diagnosis of calciphylaxis.

Calciphylaxis is an underrecognized crystal deposition disease that’s associated with panniculitis, said Dr. Bridges, speaking at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. When calcium accumulates in small subcutaneous vessels, an occlusive vasculopathy is created within the dermis.

A soft-tissue radiograph of the affected area may also be helpful. Calciphylaxis shows as a fine netlike pattern of calcification, a finding that Dr. Bridges said has 90% specificity for the condition.

However, Dr. Bridges said, patients with panniculitis need a biopsy. “Careful selection of biopsy site and a deep specimen containing abundant fat obtained by incisional or excisional biopsy” is the best approach, allowing the pathologist to see the complete picture. In some cases, she said, a double-punch biopsy could also produce adequate specimens.

In addition to the calcium deposition, other pathologic findings may be lobular fat necrosis, with a pannicular vascular thrombosis. Though extravascular calcification can be seen in the panniculus, it’s not uncommon also to see intravascular calcification, said Dr. Bridges, who is the dermatopathology fellowship program director at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Bridges said that the patients with calciphylaxis can present with predominant panniculitis or vasculitis, or a mixed picture; patients can also have bullae, ulcers, or livedo reticularis.

The lesions are extremely painful and become increasingly violaceous, with firm subcutaneous nodules. They are variably necrotic, and become more ulcerated over time.

Calciphylaxis is multifactorial and progressive. The prognosis is very poor for individuals with the condition, Dr. Bridges said. The median survival is 10 months, with 1-year survival rates of 46%, and just 20% of individuals with calciphylaxis surviving 2 years after diagnosis.

Gangrene is a frequent complication, and multisystem organ failure often occurs as well, she said.

Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in individuals with chronic kidney disease and is seen in 4% of hemodialysis patients. However, it may also occur in individuals without uremia. In associations that are incompletely understood, calciphylaxis has been associated with warfarin therapy, connective tissue disorders, Crohn’s disease, liver disease, diabetes, hematologic malignancies, factor V Leiden deficiency, and protein C and S deficiency.

There’s a need for clinical suspicion of calciphylaxis when individuals with any of these conditions present with painful erythematous nodules, or with a vasculitic picture, she said.

Other, more common crystal deposition diseases can also be associated with panniculitis and can be in the differential, Dr. Bridges said. In patients with gout, sodium urate crystal deposition can occur in subcutaneous tissues.

Cutaneous oxalosis can occur as a primary disorder, when patients have metabolic errors and lack alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase or D-glycerate dehydrogenase. Oxalosis can also be an acquired syndrome in patients with chronic renal failure who have been on long-term hemodialysis.

Although there is not a clearly effective treatment for calciphylaxis, a multitargeted, multidisciplinary approach is needed to help improve tissue health and patient quality of life. Since the primary mechanism of tissue damage is thrombotic tissue ischemia, strategies are aimed at existing clots and at preventing further clot formation.

To correct the calcium-phosphate balance, several medications have been used, including sodium thiosulfate and cinacalcet. For individuals on hemodialysis, a low-calcium dialysate may be used.

Tissue perfusion and oxygenation can be improved using tissue plasminogen activator, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and the avoidance of warfarin if the patient requires anticoagulation.

To address wounds directly, debridement can begin with whirlpool time for patients. Surgical debridement may be required, and maggots can also help clean up wound beds.

Palliative care for patients should always include optimizing pain control and improving quality of life for patients with this serious and often life-limiting condition, Dr. Bridges said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes