User login

High rates of early complications seen in youth with diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: There is a high prevalence of early complications in youth with either type of diabetes.

Major finding: About 32% of youths with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication.

Data source: A cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes who were diagnosed before 20 years of age assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and who were registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

In T1D, quality of life measures fall short

NEW ORLEANS – Quality of life measures are sorely lacking for patients with type 1 diabetes, but researchers are attempting to identify measures of patient well-being that go beyond the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level.

At a symposium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, moderator Kimberly A. Driscoll, PhD, of the University of Colorado, said that “measuring quality of life [should become] a standard part of the routine diabetes clinic visit, just like taking blood pressure.” Parents, partners, and caregivers also need to be involved in deciding what quality of life measures matter, as they are the patients’ sources of support.

Marisa E. Hilliard, PhD, reported on her research team’s efforts to glean from questionnaires the measures that would matter to those with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers. The goal is to create a tool to measure diabetes-related quality of life.

“We want to be able to track quality of life over time and understand how it’s different for different people, and there is not great research on that data,” said Dr. Hilliard of Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Lawrence Fisher, PhD, concurred that a quality of life research gap exists for those with type 1 diabetes. A PubMed search indicates that 1,273 papers were published in 2015 with the key words “diabetes” and “quality of life,” yet few of these papers had designated quality of life as a primary outcome. In type 1 diabetes, quality of life “is comprised of one gigantic bucket into which we have thrown all kinds of things, and it’s mired by dozens of different kinds of measures that are all called ‘quality of life’ but define and measure it in very different ways,” said Dr. Fisher of the Behavioral Diabetes Research Group at the University of California, San Francisco.

Patient management in diabetes is a three-legged stool comprised of equal components of glycemic control, behavioral change, and quality of life. Patients are living longer and have healthier lives, but “I don’t think we’re doing as good a job with the happy” aspect of patients’ lives, he said “We spend far too much time treating glucose numbers and not enough time treating people.”

Without measuring quality of life, “you never evaluate the actual cost to individuals of achieving a gain in improved HbA1c or improved behavioral change.”

“I’m told that today, at this point, there are between 15 and 20 diabetes-specific quality of life scales,” he said. “It’s a real hodgepodge. … and one shouldn’t “just go in and pull the measure off the shelf because it has ‘quality of life’ in the title.” The measure must also take into account factors such as patient age, gender, and ethnicity.

Dr. Hilliard and her team are trying to address the “major lack of developmentally tailored measurement instruments. When you have diabetes, you have it for life, and the issues relevant to your quality of life change from age 8 to 18 to 40 and so on.”

Based on interviews with 81 people with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers, the research team developed 14 different measures specifically designed for seven different age bands of people with diabetes – from age 8 years and younger through age 60 years and older. Each age band, with the exception of age 8 years and younger, involves self-reporting by the patient and either the parent, partner, or caregiver. Only the parent self-reports in the youngest age band.

To validate the measures, the researchers plan to enroll 3,600 participants at six sites from the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange and hope to have results in about 18 months. “Our goal is to get the questionnaire to less than 30 items so it takes less than 5 minutes to complete, and to develop a scoring system,” Dr. Hilliard said.

Besides patient care, the measures could be used for clinical trials across the lifespan of people with type 1 diabetes and quality improvement initiatives, she said. Once established, an expert committee would review the measures every 5 years and update them as needed.

Dr. Fisher disclosed he is a consultant to Abbott, Eli Lilly and Company, and Roche Diagnostics.

Dr. Hilliard had no financial disclosures. The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease have provided funding for her study.

NEW ORLEANS – Quality of life measures are sorely lacking for patients with type 1 diabetes, but researchers are attempting to identify measures of patient well-being that go beyond the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level.

At a symposium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, moderator Kimberly A. Driscoll, PhD, of the University of Colorado, said that “measuring quality of life [should become] a standard part of the routine diabetes clinic visit, just like taking blood pressure.” Parents, partners, and caregivers also need to be involved in deciding what quality of life measures matter, as they are the patients’ sources of support.

Marisa E. Hilliard, PhD, reported on her research team’s efforts to glean from questionnaires the measures that would matter to those with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers. The goal is to create a tool to measure diabetes-related quality of life.

“We want to be able to track quality of life over time and understand how it’s different for different people, and there is not great research on that data,” said Dr. Hilliard of Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Lawrence Fisher, PhD, concurred that a quality of life research gap exists for those with type 1 diabetes. A PubMed search indicates that 1,273 papers were published in 2015 with the key words “diabetes” and “quality of life,” yet few of these papers had designated quality of life as a primary outcome. In type 1 diabetes, quality of life “is comprised of one gigantic bucket into which we have thrown all kinds of things, and it’s mired by dozens of different kinds of measures that are all called ‘quality of life’ but define and measure it in very different ways,” said Dr. Fisher of the Behavioral Diabetes Research Group at the University of California, San Francisco.

Patient management in diabetes is a three-legged stool comprised of equal components of glycemic control, behavioral change, and quality of life. Patients are living longer and have healthier lives, but “I don’t think we’re doing as good a job with the happy” aspect of patients’ lives, he said “We spend far too much time treating glucose numbers and not enough time treating people.”

Without measuring quality of life, “you never evaluate the actual cost to individuals of achieving a gain in improved HbA1c or improved behavioral change.”

“I’m told that today, at this point, there are between 15 and 20 diabetes-specific quality of life scales,” he said. “It’s a real hodgepodge. … and one shouldn’t “just go in and pull the measure off the shelf because it has ‘quality of life’ in the title.” The measure must also take into account factors such as patient age, gender, and ethnicity.

Dr. Hilliard and her team are trying to address the “major lack of developmentally tailored measurement instruments. When you have diabetes, you have it for life, and the issues relevant to your quality of life change from age 8 to 18 to 40 and so on.”

Based on interviews with 81 people with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers, the research team developed 14 different measures specifically designed for seven different age bands of people with diabetes – from age 8 years and younger through age 60 years and older. Each age band, with the exception of age 8 years and younger, involves self-reporting by the patient and either the parent, partner, or caregiver. Only the parent self-reports in the youngest age band.

To validate the measures, the researchers plan to enroll 3,600 participants at six sites from the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange and hope to have results in about 18 months. “Our goal is to get the questionnaire to less than 30 items so it takes less than 5 minutes to complete, and to develop a scoring system,” Dr. Hilliard said.

Besides patient care, the measures could be used for clinical trials across the lifespan of people with type 1 diabetes and quality improvement initiatives, she said. Once established, an expert committee would review the measures every 5 years and update them as needed.

Dr. Fisher disclosed he is a consultant to Abbott, Eli Lilly and Company, and Roche Diagnostics.

Dr. Hilliard had no financial disclosures. The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease have provided funding for her study.

NEW ORLEANS – Quality of life measures are sorely lacking for patients with type 1 diabetes, but researchers are attempting to identify measures of patient well-being that go beyond the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level.

At a symposium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, moderator Kimberly A. Driscoll, PhD, of the University of Colorado, said that “measuring quality of life [should become] a standard part of the routine diabetes clinic visit, just like taking blood pressure.” Parents, partners, and caregivers also need to be involved in deciding what quality of life measures matter, as they are the patients’ sources of support.

Marisa E. Hilliard, PhD, reported on her research team’s efforts to glean from questionnaires the measures that would matter to those with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers. The goal is to create a tool to measure diabetes-related quality of life.

“We want to be able to track quality of life over time and understand how it’s different for different people, and there is not great research on that data,” said Dr. Hilliard of Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Lawrence Fisher, PhD, concurred that a quality of life research gap exists for those with type 1 diabetes. A PubMed search indicates that 1,273 papers were published in 2015 with the key words “diabetes” and “quality of life,” yet few of these papers had designated quality of life as a primary outcome. In type 1 diabetes, quality of life “is comprised of one gigantic bucket into which we have thrown all kinds of things, and it’s mired by dozens of different kinds of measures that are all called ‘quality of life’ but define and measure it in very different ways,” said Dr. Fisher of the Behavioral Diabetes Research Group at the University of California, San Francisco.

Patient management in diabetes is a three-legged stool comprised of equal components of glycemic control, behavioral change, and quality of life. Patients are living longer and have healthier lives, but “I don’t think we’re doing as good a job with the happy” aspect of patients’ lives, he said “We spend far too much time treating glucose numbers and not enough time treating people.”

Without measuring quality of life, “you never evaluate the actual cost to individuals of achieving a gain in improved HbA1c or improved behavioral change.”

“I’m told that today, at this point, there are between 15 and 20 diabetes-specific quality of life scales,” he said. “It’s a real hodgepodge. … and one shouldn’t “just go in and pull the measure off the shelf because it has ‘quality of life’ in the title.” The measure must also take into account factors such as patient age, gender, and ethnicity.

Dr. Hilliard and her team are trying to address the “major lack of developmentally tailored measurement instruments. When you have diabetes, you have it for life, and the issues relevant to your quality of life change from age 8 to 18 to 40 and so on.”

Based on interviews with 81 people with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers, the research team developed 14 different measures specifically designed for seven different age bands of people with diabetes – from age 8 years and younger through age 60 years and older. Each age band, with the exception of age 8 years and younger, involves self-reporting by the patient and either the parent, partner, or caregiver. Only the parent self-reports in the youngest age band.

To validate the measures, the researchers plan to enroll 3,600 participants at six sites from the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange and hope to have results in about 18 months. “Our goal is to get the questionnaire to less than 30 items so it takes less than 5 minutes to complete, and to develop a scoring system,” Dr. Hilliard said.

Besides patient care, the measures could be used for clinical trials across the lifespan of people with type 1 diabetes and quality improvement initiatives, she said. Once established, an expert committee would review the measures every 5 years and update them as needed.

Dr. Fisher disclosed he is a consultant to Abbott, Eli Lilly and Company, and Roche Diagnostics.

Dr. Hilliard had no financial disclosures. The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease have provided funding for her study.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Physicians have inadequate tools for measuring quality of life in people with type 1 diabetes.

Major finding: Very few PubMed citations on “diabetes” and “quality of life” designated “quality of life” as a primary outcome.

Data source: Review of 1,273 PubMed citations, and interviews with 81 people with type 1 diabetes and caregivers to inform involvement of 3,600 participants at six Type 1 Diabetes Exchange sites in the development of a quality of life questionnaire.

Disclosures: Dr. Fisher disclosed he is a consultant to Abbott, Eli Lilly and Company, and Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Hilliard had no financial disclosures. The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease have provided funding for her study.

Novel vaccine scores better hepatitis B seroprotection in type 2 diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Compared with Engerix-B, Heplisav-B protected more subjects with diabetes against hepatitis B.

Major finding: At 28 weeks, 90% of the Heplisav-B group and 65% of the Engerix-B group had anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater.

Data source: A phase III randomized trial in which 321 patients received three doses of Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 (plus placebo at week 24).

Disclosures: Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

Menopause and Cardiovascular Risk Examined in Type 1 Diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Menopause and cardiovascular risk examined in type 1 diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts. Among postmenopausal women, however, those with type 1 diabetes do not have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes, with the exception of those aged 54 and older.

Those are key findings from an analysis of women enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

“In general [premenopausal] women have a better cardiovascular profile than do men, but we don’t see that same effect in diabetic women,” lead author Amena Keshawarz said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “They lose some of that protection. We’re wondering if that has some sort of relationship with menopause, because once women undergo menopause they tend to lose that protective factor.”

Ms. Keshawarz, a doctoral student and research assistant at the University of Colorado Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, Aurora, and her associates used carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and the presence of coronary artery calcification to measure the cardiovascular risk by menopausal status in 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in CACTI. The patients ranged in age from 33-74 years and the data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016. Multivariable linear and logistic regressions were used to examine the differences in cIMT and to estimate the odds ratio for coronary artery calcification (CAC). The models were run for the following ages separately: 42, 42, 48, 51, 54, and 57 years.

As a group, women with type 1 diabetes were younger than their counterparts without diabetes (a mean age of 51 vs. 55 years, respectively; P = .002), but menopause age did not differ by diabetes status. Ms. Keshawarz reported that women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of significant CAC and higher cIMT, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status. For example, among premenopausal women, type 1 diabetes increased the odds of CAC at all ages, and cIMT was higher in women with type 1 diabetes, compared with those in the nondiabetic group at age 45 years and older. Among postmenopausal women, type 1 diabetes was associated with only higher CAC at age 54 years and older and with higher cIMT at age 57 years.

“Type 1 diabetic women face unique problems in their health that are not just endocrinology-related,” Ms. Keshawarz said. “If they haven’t undergone menopause yet, that needs to be taken into account when you’re proposing interventions and lifestyle and behavioral changes, because there is an increased possibility that they’re going to be at higher risk of coronary artery calcification and thicker [coronary] artery walls.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes have a higher cardiovascular risk, compared with their peers who do not have diabetes.

Major finding: Women with type 1 diabetes had significantly higher age-adjusted odds of higher coronary artery calcification and higher carotid intima-media thickness, compared with those in the nondiabetic group, but these relationships differed by age and menopause status.

Data source: An analysis of 106 women with type 1 diabetes and 140 nondiabetic women who were enrolled in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Keshawarz reported having no financial disclosures.

Who are the ‘no-shows’ to diabetes education classes?

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Endoscopic ablation follows gastric bypass principles

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

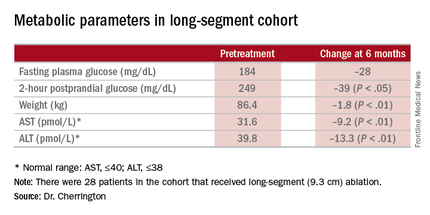

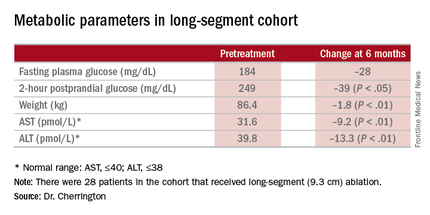

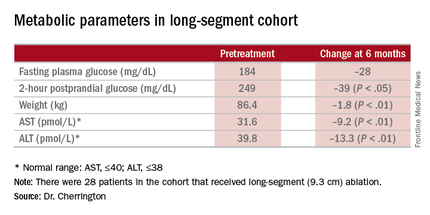

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

AT THE ADA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Duodenal mucosal resurfacing is an investigational procedure to achieve improvement in metabolic parameters in type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: A cohort that has HbA1c as high as 11% before the procedure had average HbA1c of 7.5% afterward.

Data source: Investigational study of 39 patients who had the procedure at a single center in Chile.

Disclosures: Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

Body weight of U.S. veterans increased significantly from 2000 to 2014

NEW ORLEANS – United States veterans born since 1950 have gained weight faster than a comparable cohort of older veterans, results from a large analysis demonstrated. In fact, they’re starting out about 10 kg heavier than previous generations.

“There is a tremendous need for an intervention to prevent or reverse weight gain in this population to prevent the development of diabetes,” lead author Margery J. Tamas said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In an effort to examine age-related trends in body weight and diabetes prevalence in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system, Ms. Tamas and her associates used the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to examine trends in diabetes among 4,680,735 patients born between 1915 and 1984 who had at least one outpatient visit per year within any consecutive 4-year interval between 2000 and 2014. More than one-third (36%) had diabetes, 92% were male, 78% were white, and their mean age was 69 years. The researchers defined the birth cohorts by 5-year intervals.

Ms. Tamas, who conducted the research as part of her master’s thesis at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, reported that diabetes was more prevalent among men, compared with women (38% vs. 24%, respectively). Diabetes prevalence was highest among patients born between 1940 and 1944 (44%) and lowest among those born between 1980 and 1984 (4%).