User login

American College of Cardiology (ACC): Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass

Myocardial fibrosis assessment fine-tunes ICD selection

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Detection of myocardial midwall fibrosis via cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy provides prognostic information independent of left ventricular ejection fraction.

"Low LVEF and fibrosis uniquely identify the need for an ICD [implantable cardioverter-defibrillator]. This is new information that helps refine our understanding of whom it is that’s uniquely at risk. We’ve always had these troublesome questions in patients with nonischemic heart failure," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

He highlighted what he called "very provocative data" in a recent study led by Dr. Sanjay K. Prasad of Royal Brompton Hospital in London. The investigators evaluated 472 consecutive patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy using late gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Thirty percent of them were found to have midwall fibrosis. Their all-cause mortality rate during a median 5.3 years of prospective follow-up was 26.8%, compared with 10.6% in the 330 patients without fibrosis. An arrhythmic composite event comprising sudden cardiac death (SCD), aborted SCD, or sustained ventricular tachycardia occurred in 29.6% of the group with fibrosis vs. 7% of patients without fibrosis.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for LVEF and other prognostic factors, the presence of midwall fibrosis was independently associated with a 2.43-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 3.2-fold greater risk of cardiovascular mortality or heart transplantation, a 4.6-fold increase in SCD or aborted SCD, and a 1.6-fold increased likelihood of a composite of heart failure hospitalization, mortality from heart failure, or cardiac transplantation (JAMA 2013;309:896-908).

Dr. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure, noted that the guidelines grant a strong Class I/Level of Evidence B recommendation for implantation of an ICD for primary prevention in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients who are in New York Heart Association functional class II or III and have an LVEF of 35% or less. But there is a pressing need for refined implantation criteria. Basing the ICD decision on only these criteria results in a low rate of appropriate shocks, a high frequency of inappropriate shocks, and exclusion from device therapy of a group of patients with a high relative risk of SCD.

The British study provides reason for optimism in this regard. Using a greater than 15% estimated SCD risk based upon LVEF plus midwall fibrosis as a proposed indication for ICD implantation, the investigators found that an additional 12 patients in their cohort would receive an ICD and 43 others would now avoid ICD implantation, noted Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Detection of myocardial midwall fibrosis via cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy provides prognostic information independent of left ventricular ejection fraction.

"Low LVEF and fibrosis uniquely identify the need for an ICD [implantable cardioverter-defibrillator]. This is new information that helps refine our understanding of whom it is that’s uniquely at risk. We’ve always had these troublesome questions in patients with nonischemic heart failure," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

He highlighted what he called "very provocative data" in a recent study led by Dr. Sanjay K. Prasad of Royal Brompton Hospital in London. The investigators evaluated 472 consecutive patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy using late gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Thirty percent of them were found to have midwall fibrosis. Their all-cause mortality rate during a median 5.3 years of prospective follow-up was 26.8%, compared with 10.6% in the 330 patients without fibrosis. An arrhythmic composite event comprising sudden cardiac death (SCD), aborted SCD, or sustained ventricular tachycardia occurred in 29.6% of the group with fibrosis vs. 7% of patients without fibrosis.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for LVEF and other prognostic factors, the presence of midwall fibrosis was independently associated with a 2.43-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 3.2-fold greater risk of cardiovascular mortality or heart transplantation, a 4.6-fold increase in SCD or aborted SCD, and a 1.6-fold increased likelihood of a composite of heart failure hospitalization, mortality from heart failure, or cardiac transplantation (JAMA 2013;309:896-908).

Dr. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure, noted that the guidelines grant a strong Class I/Level of Evidence B recommendation for implantation of an ICD for primary prevention in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients who are in New York Heart Association functional class II or III and have an LVEF of 35% or less. But there is a pressing need for refined implantation criteria. Basing the ICD decision on only these criteria results in a low rate of appropriate shocks, a high frequency of inappropriate shocks, and exclusion from device therapy of a group of patients with a high relative risk of SCD.

The British study provides reason for optimism in this regard. Using a greater than 15% estimated SCD risk based upon LVEF plus midwall fibrosis as a proposed indication for ICD implantation, the investigators found that an additional 12 patients in their cohort would receive an ICD and 43 others would now avoid ICD implantation, noted Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Detection of myocardial midwall fibrosis via cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy provides prognostic information independent of left ventricular ejection fraction.

"Low LVEF and fibrosis uniquely identify the need for an ICD [implantable cardioverter-defibrillator]. This is new information that helps refine our understanding of whom it is that’s uniquely at risk. We’ve always had these troublesome questions in patients with nonischemic heart failure," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

He highlighted what he called "very provocative data" in a recent study led by Dr. Sanjay K. Prasad of Royal Brompton Hospital in London. The investigators evaluated 472 consecutive patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy using late gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Thirty percent of them were found to have midwall fibrosis. Their all-cause mortality rate during a median 5.3 years of prospective follow-up was 26.8%, compared with 10.6% in the 330 patients without fibrosis. An arrhythmic composite event comprising sudden cardiac death (SCD), aborted SCD, or sustained ventricular tachycardia occurred in 29.6% of the group with fibrosis vs. 7% of patients without fibrosis.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for LVEF and other prognostic factors, the presence of midwall fibrosis was independently associated with a 2.43-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 3.2-fold greater risk of cardiovascular mortality or heart transplantation, a 4.6-fold increase in SCD or aborted SCD, and a 1.6-fold increased likelihood of a composite of heart failure hospitalization, mortality from heart failure, or cardiac transplantation (JAMA 2013;309:896-908).

Dr. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure, noted that the guidelines grant a strong Class I/Level of Evidence B recommendation for implantation of an ICD for primary prevention in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients who are in New York Heart Association functional class II or III and have an LVEF of 35% or less. But there is a pressing need for refined implantation criteria. Basing the ICD decision on only these criteria results in a low rate of appropriate shocks, a high frequency of inappropriate shocks, and exclusion from device therapy of a group of patients with a high relative risk of SCD.

The British study provides reason for optimism in this regard. Using a greater than 15% estimated SCD risk based upon LVEF plus midwall fibrosis as a proposed indication for ICD implantation, the investigators found that an additional 12 patients in their cohort would receive an ICD and 43 others would now avoid ICD implantation, noted Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Mini-VADs could transform heart failure therapy

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Survival in patients with advanced heart failure who receive a left ventricular assist device as destination therapy or as a bridge to transplant has increased dramatically in recent years – and the best may be yet to come.

"There is a robust pipeline of mini-VADs [mini–ventricular assist devices] providing partial circulatory support that should allow wider applicability," Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This new generation of smaller, ever-more-high-tech VADs now entering clinical trials is made up of devices designed for implantation via a shorter, less invasive, off-pump hybrid surgical procedure, which should reduce operative morbidity and mortality. The rechargeable battery will also be implanted. Some of the devices are even earmarked for implantation nonsurgically in the cath lab, explained Dr. Mack, a cardiothoracic surgeon who is medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

The ease of implantation of these next-gen mini-VADs makes them suitable for use at an earlier stage in the development of heart failure than the two left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) now approved for long-term use in the United States. The expectation is that this earlier mechanical intervention might further improve patient outcomes, he added.

Two-year survival following implantation of the HeartMate II, the current workhorse LVAD, is 65%, the same as with heart transplantation. To put that in perspective, in the REMATCH trial, which more than a decade ago led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first LVAD as long-term therapy, 2-year survival with device therapy was just 25%.

Today at many top institutions, Dr. Mack said, the number of LVADs implanted as destination therapy – that is, as an alternative to heart transplantation – now dwarfs the number of heart transplants done. This reflects a widespread recognition that the organ donor pool is unlikely to grow larger despite many efforts. Indeed, the number of heart transplants performed in North America has remained constant at roughly 2,300 per year for the past 20 years.

The other LVAD approved as destination therapy or bridge to transplant is the HeartWare VAD. The FDA granted approval based upon the results of the 30-center, prospective ADVANCE trial, which demonstrated that the HeartWare VAD’s performance was noninferior to that of the HeartMate II (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200).

Both LVADs are small continuous-flow devices with only a single moving part. They are quiet and energy efficient. Their simplicity of design makes them less susceptible to mechanical wear and much more reliable than earlier-generation LVADs. Three-year device replacement rates are now less than 10%, according to Dr. Mack.

But the current LVADs have significant shortcomings. In a worldwide series of close to 6,000 patients who have received a device as destination therapy or bridge to transplant, the 3-year combined rate of bleeding, stroke, infection, device malfunction, or death was 86%. The 3-year stroke incidence was 19% (J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2013;32:141-56).

Bleeding is a major problem with these devices for three reasons. Virtually all LVAD recipients develop acquired von Willebrand’s disease. Moreover, patients are on warfarin because of their high stroke risk. And gastrointestinal bleeding is a significant problem due to the angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformations that result from the nonpulsatile continuous blood flow.

Among the mini-VADs well along in the developmental pipeline are the MicroMed HeartAssist 5, which is 71 x 30 mm in size and weighs only 92 g. Also in development are the HeartWare Miniaturized VAD (MVAD), which is about the size of a golf ball, and the HeartMate III.

The device drawing the most interest from cardiac surgeons, however, is the CircuLite Synergy mini-VAD, which is the size of an AA battery. It’s implanted off-pump with a small right thoracotomy for left atrial access. The device sits in a pocket in the right deltoid-pectoral groove for axillary artery access. The inflow is from the left atrium, with outflow into the right subclavian artery.

This device will undergo further modification to a totally endovascular concept that avoids the right thoracotomy. Inflow will be through the subclavian vein via a transseptal puncture approach, with outflow into the subclavian artery.

"The idea is that this will become a cath lab procedure. The device will sit in a pocket similar to a pacemaker," Dr. Mack explained.

Although the future looks bright for mini-VADs, plenty of key questions about them still await answers, the surgeon noted. Among them: Will partial circulatory support be sufficient for all patients with advanced heart failure? Will it be possible to predict which patients with New York Heart Association class III heart failure are destined to progress to advanced disease, and if so, will early implantation of a partial support device in these less-sick patients have a favorable effect on their quality of life? Might it slow progression of heart failure, and perhaps even induce remission?

The answers are expected to come from ongoing and planned clinical trials of these investigational devices.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-239), noted that the guidelines endorse LVADs as destination therapy or bridge to transplant or recovery in carefully selected patients with advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with a class IIa/level of evidence B recommendation.

"Mechanical circulatory support is no longer a Hail Mary pass. This is no longer an experimental intervention. This really should be incorporated in our usual thought processes in advanced heart failure," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He noted that the guidelines list a number of clinical events and other findings that are useful in identifying patients who have progressed to advanced heart failure, at which point he said it’s time to communicate with a center that can evaluate the patient for a possible LVAD or heart transplantation. These indicators include two or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits for heart failure in the past year, progressive deterioration in renal function, intolerance to beta-blocker therapy, unexplained weight loss, or inability to walk one block on level ground because of fatigue or shortness of breath.

Dr. Mack and Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Survival in patients with advanced heart failure who receive a left ventricular assist device as destination therapy or as a bridge to transplant has increased dramatically in recent years – and the best may be yet to come.

"There is a robust pipeline of mini-VADs [mini–ventricular assist devices] providing partial circulatory support that should allow wider applicability," Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This new generation of smaller, ever-more-high-tech VADs now entering clinical trials is made up of devices designed for implantation via a shorter, less invasive, off-pump hybrid surgical procedure, which should reduce operative morbidity and mortality. The rechargeable battery will also be implanted. Some of the devices are even earmarked for implantation nonsurgically in the cath lab, explained Dr. Mack, a cardiothoracic surgeon who is medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

The ease of implantation of these next-gen mini-VADs makes them suitable for use at an earlier stage in the development of heart failure than the two left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) now approved for long-term use in the United States. The expectation is that this earlier mechanical intervention might further improve patient outcomes, he added.

Two-year survival following implantation of the HeartMate II, the current workhorse LVAD, is 65%, the same as with heart transplantation. To put that in perspective, in the REMATCH trial, which more than a decade ago led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first LVAD as long-term therapy, 2-year survival with device therapy was just 25%.

Today at many top institutions, Dr. Mack said, the number of LVADs implanted as destination therapy – that is, as an alternative to heart transplantation – now dwarfs the number of heart transplants done. This reflects a widespread recognition that the organ donor pool is unlikely to grow larger despite many efforts. Indeed, the number of heart transplants performed in North America has remained constant at roughly 2,300 per year for the past 20 years.

The other LVAD approved as destination therapy or bridge to transplant is the HeartWare VAD. The FDA granted approval based upon the results of the 30-center, prospective ADVANCE trial, which demonstrated that the HeartWare VAD’s performance was noninferior to that of the HeartMate II (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200).

Both LVADs are small continuous-flow devices with only a single moving part. They are quiet and energy efficient. Their simplicity of design makes them less susceptible to mechanical wear and much more reliable than earlier-generation LVADs. Three-year device replacement rates are now less than 10%, according to Dr. Mack.

But the current LVADs have significant shortcomings. In a worldwide series of close to 6,000 patients who have received a device as destination therapy or bridge to transplant, the 3-year combined rate of bleeding, stroke, infection, device malfunction, or death was 86%. The 3-year stroke incidence was 19% (J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2013;32:141-56).

Bleeding is a major problem with these devices for three reasons. Virtually all LVAD recipients develop acquired von Willebrand’s disease. Moreover, patients are on warfarin because of their high stroke risk. And gastrointestinal bleeding is a significant problem due to the angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformations that result from the nonpulsatile continuous blood flow.

Among the mini-VADs well along in the developmental pipeline are the MicroMed HeartAssist 5, which is 71 x 30 mm in size and weighs only 92 g. Also in development are the HeartWare Miniaturized VAD (MVAD), which is about the size of a golf ball, and the HeartMate III.

The device drawing the most interest from cardiac surgeons, however, is the CircuLite Synergy mini-VAD, which is the size of an AA battery. It’s implanted off-pump with a small right thoracotomy for left atrial access. The device sits in a pocket in the right deltoid-pectoral groove for axillary artery access. The inflow is from the left atrium, with outflow into the right subclavian artery.

This device will undergo further modification to a totally endovascular concept that avoids the right thoracotomy. Inflow will be through the subclavian vein via a transseptal puncture approach, with outflow into the subclavian artery.

"The idea is that this will become a cath lab procedure. The device will sit in a pocket similar to a pacemaker," Dr. Mack explained.

Although the future looks bright for mini-VADs, plenty of key questions about them still await answers, the surgeon noted. Among them: Will partial circulatory support be sufficient for all patients with advanced heart failure? Will it be possible to predict which patients with New York Heart Association class III heart failure are destined to progress to advanced disease, and if so, will early implantation of a partial support device in these less-sick patients have a favorable effect on their quality of life? Might it slow progression of heart failure, and perhaps even induce remission?

The answers are expected to come from ongoing and planned clinical trials of these investigational devices.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-239), noted that the guidelines endorse LVADs as destination therapy or bridge to transplant or recovery in carefully selected patients with advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with a class IIa/level of evidence B recommendation.

"Mechanical circulatory support is no longer a Hail Mary pass. This is no longer an experimental intervention. This really should be incorporated in our usual thought processes in advanced heart failure," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He noted that the guidelines list a number of clinical events and other findings that are useful in identifying patients who have progressed to advanced heart failure, at which point he said it’s time to communicate with a center that can evaluate the patient for a possible LVAD or heart transplantation. These indicators include two or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits for heart failure in the past year, progressive deterioration in renal function, intolerance to beta-blocker therapy, unexplained weight loss, or inability to walk one block on level ground because of fatigue or shortness of breath.

Dr. Mack and Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Survival in patients with advanced heart failure who receive a left ventricular assist device as destination therapy or as a bridge to transplant has increased dramatically in recent years – and the best may be yet to come.

"There is a robust pipeline of mini-VADs [mini–ventricular assist devices] providing partial circulatory support that should allow wider applicability," Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This new generation of smaller, ever-more-high-tech VADs now entering clinical trials is made up of devices designed for implantation via a shorter, less invasive, off-pump hybrid surgical procedure, which should reduce operative morbidity and mortality. The rechargeable battery will also be implanted. Some of the devices are even earmarked for implantation nonsurgically in the cath lab, explained Dr. Mack, a cardiothoracic surgeon who is medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

The ease of implantation of these next-gen mini-VADs makes them suitable for use at an earlier stage in the development of heart failure than the two left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) now approved for long-term use in the United States. The expectation is that this earlier mechanical intervention might further improve patient outcomes, he added.

Two-year survival following implantation of the HeartMate II, the current workhorse LVAD, is 65%, the same as with heart transplantation. To put that in perspective, in the REMATCH trial, which more than a decade ago led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first LVAD as long-term therapy, 2-year survival with device therapy was just 25%.

Today at many top institutions, Dr. Mack said, the number of LVADs implanted as destination therapy – that is, as an alternative to heart transplantation – now dwarfs the number of heart transplants done. This reflects a widespread recognition that the organ donor pool is unlikely to grow larger despite many efforts. Indeed, the number of heart transplants performed in North America has remained constant at roughly 2,300 per year for the past 20 years.

The other LVAD approved as destination therapy or bridge to transplant is the HeartWare VAD. The FDA granted approval based upon the results of the 30-center, prospective ADVANCE trial, which demonstrated that the HeartWare VAD’s performance was noninferior to that of the HeartMate II (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200).

Both LVADs are small continuous-flow devices with only a single moving part. They are quiet and energy efficient. Their simplicity of design makes them less susceptible to mechanical wear and much more reliable than earlier-generation LVADs. Three-year device replacement rates are now less than 10%, according to Dr. Mack.

But the current LVADs have significant shortcomings. In a worldwide series of close to 6,000 patients who have received a device as destination therapy or bridge to transplant, the 3-year combined rate of bleeding, stroke, infection, device malfunction, or death was 86%. The 3-year stroke incidence was 19% (J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2013;32:141-56).

Bleeding is a major problem with these devices for three reasons. Virtually all LVAD recipients develop acquired von Willebrand’s disease. Moreover, patients are on warfarin because of their high stroke risk. And gastrointestinal bleeding is a significant problem due to the angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformations that result from the nonpulsatile continuous blood flow.

Among the mini-VADs well along in the developmental pipeline are the MicroMed HeartAssist 5, which is 71 x 30 mm in size and weighs only 92 g. Also in development are the HeartWare Miniaturized VAD (MVAD), which is about the size of a golf ball, and the HeartMate III.

The device drawing the most interest from cardiac surgeons, however, is the CircuLite Synergy mini-VAD, which is the size of an AA battery. It’s implanted off-pump with a small right thoracotomy for left atrial access. The device sits in a pocket in the right deltoid-pectoral groove for axillary artery access. The inflow is from the left atrium, with outflow into the right subclavian artery.

This device will undergo further modification to a totally endovascular concept that avoids the right thoracotomy. Inflow will be through the subclavian vein via a transseptal puncture approach, with outflow into the subclavian artery.

"The idea is that this will become a cath lab procedure. The device will sit in a pocket similar to a pacemaker," Dr. Mack explained.

Although the future looks bright for mini-VADs, plenty of key questions about them still await answers, the surgeon noted. Among them: Will partial circulatory support be sufficient for all patients with advanced heart failure? Will it be possible to predict which patients with New York Heart Association class III heart failure are destined to progress to advanced disease, and if so, will early implantation of a partial support device in these less-sick patients have a favorable effect on their quality of life? Might it slow progression of heart failure, and perhaps even induce remission?

The answers are expected to come from ongoing and planned clinical trials of these investigational devices.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, who chaired the writing committee for the 2013 ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-239), noted that the guidelines endorse LVADs as destination therapy or bridge to transplant or recovery in carefully selected patients with advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with a class IIa/level of evidence B recommendation.

"Mechanical circulatory support is no longer a Hail Mary pass. This is no longer an experimental intervention. This really should be incorporated in our usual thought processes in advanced heart failure," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

He noted that the guidelines list a number of clinical events and other findings that are useful in identifying patients who have progressed to advanced heart failure, at which point he said it’s time to communicate with a center that can evaluate the patient for a possible LVAD or heart transplantation. These indicators include two or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits for heart failure in the past year, progressive deterioration in renal function, intolerance to beta-blocker therapy, unexplained weight loss, or inability to walk one block on level ground because of fatigue or shortness of breath.

Dr. Mack and Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Recent data support preventive multivessel PCI in STEMI patients

SNOWMASS, COLO. – ST-elevation MI guidelines released just last year by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association are already in need of revision in light of important new evidence about the benefits of complete rather than culprit vessel–only revascularization at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

"The guidelines need a facelift," Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines deem PCI of a noninfarct artery at the time of primary PCI in STEMI patients without hemodynamic compromise to be harmful. This practice is categorized as class IIIB, meaning "don’t do it" (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;e78-140). Similarly, the 2012 European Society of Cardiology STEMI guidelines state, "Primary PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel with the exception of cardiogenic shock and persistent ischemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion" (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2569-619).

But the recently published PRAMI (Preventive Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction) trial is a game changer in this regard. Investigators at five U.K. centers randomized 465 acute STEMI patients to infarct artery–only primary PCI or to preventive primary PCI of both the culprit vessel and noninfarct coronary arteries with major stenoses.

"I like the concept of prevention through intervention. It makes sense, I think," commented Dr. Holmes, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The tricky part will be to craft the revised guideline recommendations so as to encourage preventive PCI while avoiding the all-too-human temptation to overestimate lesion severity and engage the well-known oculostenotic reflex, he added.

During a mean follow-up of 23 months in the PRAMI study, the primary outcome – a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or refractory angina – occurred in 21 patients assigned to preventive PCI, compared with 53 randomized to infarct artery–only PCI, for a highly significant 65% relative risk reduction (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

"Do the STEMI guidelines need a facelift?" Dr. Holmes asked the next speaker at the conference, who just happened to be ACC President-elect Patrick T. O’Gara, M.D., chair of the ACC/AHA STEMI Guideline Writing Committee.

"I think, actually, there are several areas in the STEMI guidelines that require revision within the year of their publication," responded Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

"I think this preventive PCI concept is one – and we need to get good minds together to hit the right mark. Another is routine use of thrombus aspiration at the time of primary PCI. A third area might be the logistics around hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors: Are we trying to achieve a certain temperature or achieve some other outcome? We anticipate that the writing committee will be re-impaneled, probably in the next 3 months, to take these on," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. Holmes welcomed PRAMI because it sheds new light on what has been a cloudy area of research. For example, a new Canadian meta-analysis of 26 published studies totaling 38,438 STEMI patients who underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI and 7,886 others with multivessel primary PCI concluded there was no difference between the two strategies in terms of hospital mortality; in other words, multivessel primary PCI provided no added benefit. However, among the three randomized studies included in the meta-analysis, there was a highly significant 76% reduction in hospital mortality with multivessel primary PCI (Am. J. Heart J. 2014;167:1-14.e2). With PRAMI, that makes a total of four positive and no negative randomized trials.

In other developments pertaining to multivessel primary PCI in STEMI, Dr. Holmes noted that this intervention recently received support when applied in the setting of the STEMI patient with multivessel disease who presents with cardiogenic shock and resuscitated cardiac arrest. French investigators published a prospective observational study involving 169 such patients, 66 of whom received multivessel primary PCI while the other 109 underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI. The primary endpoint, a 6-month composite of recurrent cardiac arrest and death due to cardiogenic shock, occurred in 50% of those who got multivessel PCI, compared with 68% of those with culprit vessel-only PCI (JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:115-25).

"The conclusion is, if somebody comes in with STEMI and cardiogenic shock and they’ve arrested, you should treat everything you can. Go for it." Dr. Holmes said.

A couple of noteworthy recent studies looked at the effect of chronic total occlusion (CTO) in a non–infarct-related artery in STEMI patients. Dutch investigators reported on 5,018 consecutive unselected STEMI patients. Twelve percent had cardiogenic shock, 64% had single-vessel disease, 23% had multivessel disease with CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 13% had multivessel disease without a CTO. Thirty-day mortality was 11% in STEMI patients with multivessel disease and a CTO, 4.3% in those with multivessel disease without a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 3% in those with single-vessel disease. In the group with cardiogenic shock, 30-day mortality was 61% in patients with a CTO, 42% in those with multivessel disease but no CTO, and 26% with single-vessel disease (Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013;15:425-32).

Investigators from the HORIZONS-AMI trial also recently evaluated the effect of a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery. The study population included 3,283 patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI. The 283 patients with multivessel disease and a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery had an adjusted 2.88-fold greater 30-day mortality and 2.27-fold greater 3-year mortality than those with single-vessel disease. The 1,477 patients with multivessel disease but no CTO had a 1.75-fold greater 30-day mortality than those with single-vessel disease, but no increased risk through 3 years (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:768-75).

"Does this mean you should bring patients back to do the CTO? Probably. We don’t do that enough, but probably that’s indeed the case," Dr. Holmes commented.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – ST-elevation MI guidelines released just last year by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association are already in need of revision in light of important new evidence about the benefits of complete rather than culprit vessel–only revascularization at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

"The guidelines need a facelift," Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines deem PCI of a noninfarct artery at the time of primary PCI in STEMI patients without hemodynamic compromise to be harmful. This practice is categorized as class IIIB, meaning "don’t do it" (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;e78-140). Similarly, the 2012 European Society of Cardiology STEMI guidelines state, "Primary PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel with the exception of cardiogenic shock and persistent ischemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion" (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2569-619).

But the recently published PRAMI (Preventive Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction) trial is a game changer in this regard. Investigators at five U.K. centers randomized 465 acute STEMI patients to infarct artery–only primary PCI or to preventive primary PCI of both the culprit vessel and noninfarct coronary arteries with major stenoses.

"I like the concept of prevention through intervention. It makes sense, I think," commented Dr. Holmes, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The tricky part will be to craft the revised guideline recommendations so as to encourage preventive PCI while avoiding the all-too-human temptation to overestimate lesion severity and engage the well-known oculostenotic reflex, he added.

During a mean follow-up of 23 months in the PRAMI study, the primary outcome – a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or refractory angina – occurred in 21 patients assigned to preventive PCI, compared with 53 randomized to infarct artery–only PCI, for a highly significant 65% relative risk reduction (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

"Do the STEMI guidelines need a facelift?" Dr. Holmes asked the next speaker at the conference, who just happened to be ACC President-elect Patrick T. O’Gara, M.D., chair of the ACC/AHA STEMI Guideline Writing Committee.

"I think, actually, there are several areas in the STEMI guidelines that require revision within the year of their publication," responded Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

"I think this preventive PCI concept is one – and we need to get good minds together to hit the right mark. Another is routine use of thrombus aspiration at the time of primary PCI. A third area might be the logistics around hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors: Are we trying to achieve a certain temperature or achieve some other outcome? We anticipate that the writing committee will be re-impaneled, probably in the next 3 months, to take these on," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. Holmes welcomed PRAMI because it sheds new light on what has been a cloudy area of research. For example, a new Canadian meta-analysis of 26 published studies totaling 38,438 STEMI patients who underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI and 7,886 others with multivessel primary PCI concluded there was no difference between the two strategies in terms of hospital mortality; in other words, multivessel primary PCI provided no added benefit. However, among the three randomized studies included in the meta-analysis, there was a highly significant 76% reduction in hospital mortality with multivessel primary PCI (Am. J. Heart J. 2014;167:1-14.e2). With PRAMI, that makes a total of four positive and no negative randomized trials.

In other developments pertaining to multivessel primary PCI in STEMI, Dr. Holmes noted that this intervention recently received support when applied in the setting of the STEMI patient with multivessel disease who presents with cardiogenic shock and resuscitated cardiac arrest. French investigators published a prospective observational study involving 169 such patients, 66 of whom received multivessel primary PCI while the other 109 underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI. The primary endpoint, a 6-month composite of recurrent cardiac arrest and death due to cardiogenic shock, occurred in 50% of those who got multivessel PCI, compared with 68% of those with culprit vessel-only PCI (JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:115-25).

"The conclusion is, if somebody comes in with STEMI and cardiogenic shock and they’ve arrested, you should treat everything you can. Go for it." Dr. Holmes said.

A couple of noteworthy recent studies looked at the effect of chronic total occlusion (CTO) in a non–infarct-related artery in STEMI patients. Dutch investigators reported on 5,018 consecutive unselected STEMI patients. Twelve percent had cardiogenic shock, 64% had single-vessel disease, 23% had multivessel disease with CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 13% had multivessel disease without a CTO. Thirty-day mortality was 11% in STEMI patients with multivessel disease and a CTO, 4.3% in those with multivessel disease without a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 3% in those with single-vessel disease. In the group with cardiogenic shock, 30-day mortality was 61% in patients with a CTO, 42% in those with multivessel disease but no CTO, and 26% with single-vessel disease (Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013;15:425-32).

Investigators from the HORIZONS-AMI trial also recently evaluated the effect of a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery. The study population included 3,283 patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI. The 283 patients with multivessel disease and a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery had an adjusted 2.88-fold greater 30-day mortality and 2.27-fold greater 3-year mortality than those with single-vessel disease. The 1,477 patients with multivessel disease but no CTO had a 1.75-fold greater 30-day mortality than those with single-vessel disease, but no increased risk through 3 years (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:768-75).

"Does this mean you should bring patients back to do the CTO? Probably. We don’t do that enough, but probably that’s indeed the case," Dr. Holmes commented.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – ST-elevation MI guidelines released just last year by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association are already in need of revision in light of important new evidence about the benefits of complete rather than culprit vessel–only revascularization at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

"The guidelines need a facelift," Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines deem PCI of a noninfarct artery at the time of primary PCI in STEMI patients without hemodynamic compromise to be harmful. This practice is categorized as class IIIB, meaning "don’t do it" (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;e78-140). Similarly, the 2012 European Society of Cardiology STEMI guidelines state, "Primary PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel with the exception of cardiogenic shock and persistent ischemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion" (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2569-619).

But the recently published PRAMI (Preventive Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction) trial is a game changer in this regard. Investigators at five U.K. centers randomized 465 acute STEMI patients to infarct artery–only primary PCI or to preventive primary PCI of both the culprit vessel and noninfarct coronary arteries with major stenoses.

"I like the concept of prevention through intervention. It makes sense, I think," commented Dr. Holmes, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The tricky part will be to craft the revised guideline recommendations so as to encourage preventive PCI while avoiding the all-too-human temptation to overestimate lesion severity and engage the well-known oculostenotic reflex, he added.

During a mean follow-up of 23 months in the PRAMI study, the primary outcome – a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or refractory angina – occurred in 21 patients assigned to preventive PCI, compared with 53 randomized to infarct artery–only PCI, for a highly significant 65% relative risk reduction (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

"Do the STEMI guidelines need a facelift?" Dr. Holmes asked the next speaker at the conference, who just happened to be ACC President-elect Patrick T. O’Gara, M.D., chair of the ACC/AHA STEMI Guideline Writing Committee.

"I think, actually, there are several areas in the STEMI guidelines that require revision within the year of their publication," responded Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

"I think this preventive PCI concept is one – and we need to get good minds together to hit the right mark. Another is routine use of thrombus aspiration at the time of primary PCI. A third area might be the logistics around hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors: Are we trying to achieve a certain temperature or achieve some other outcome? We anticipate that the writing committee will be re-impaneled, probably in the next 3 months, to take these on," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. Holmes welcomed PRAMI because it sheds new light on what has been a cloudy area of research. For example, a new Canadian meta-analysis of 26 published studies totaling 38,438 STEMI patients who underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI and 7,886 others with multivessel primary PCI concluded there was no difference between the two strategies in terms of hospital mortality; in other words, multivessel primary PCI provided no added benefit. However, among the three randomized studies included in the meta-analysis, there was a highly significant 76% reduction in hospital mortality with multivessel primary PCI (Am. J. Heart J. 2014;167:1-14.e2). With PRAMI, that makes a total of four positive and no negative randomized trials.

In other developments pertaining to multivessel primary PCI in STEMI, Dr. Holmes noted that this intervention recently received support when applied in the setting of the STEMI patient with multivessel disease who presents with cardiogenic shock and resuscitated cardiac arrest. French investigators published a prospective observational study involving 169 such patients, 66 of whom received multivessel primary PCI while the other 109 underwent culprit vessel–only primary PCI. The primary endpoint, a 6-month composite of recurrent cardiac arrest and death due to cardiogenic shock, occurred in 50% of those who got multivessel PCI, compared with 68% of those with culprit vessel-only PCI (JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:115-25).

"The conclusion is, if somebody comes in with STEMI and cardiogenic shock and they’ve arrested, you should treat everything you can. Go for it." Dr. Holmes said.

A couple of noteworthy recent studies looked at the effect of chronic total occlusion (CTO) in a non–infarct-related artery in STEMI patients. Dutch investigators reported on 5,018 consecutive unselected STEMI patients. Twelve percent had cardiogenic shock, 64% had single-vessel disease, 23% had multivessel disease with CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 13% had multivessel disease without a CTO. Thirty-day mortality was 11% in STEMI patients with multivessel disease and a CTO, 4.3% in those with multivessel disease without a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery, and 3% in those with single-vessel disease. In the group with cardiogenic shock, 30-day mortality was 61% in patients with a CTO, 42% in those with multivessel disease but no CTO, and 26% with single-vessel disease (Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013;15:425-32).

Investigators from the HORIZONS-AMI trial also recently evaluated the effect of a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery. The study population included 3,283 patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI. The 283 patients with multivessel disease and a CTO in a non–infarct-related artery had an adjusted 2.88-fold greater 30-day mortality and 2.27-fold greater 3-year mortality than those with single-vessel disease. The 1,477 patients with multivessel disease but no CTO had a 1.75-fold greater 30-day mortality than those with single-vessel disease, but no increased risk through 3 years (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:768-75).

"Does this mean you should bring patients back to do the CTO? Probably. We don’t do that enough, but probably that’s indeed the case," Dr. Holmes commented.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

New tools for stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation

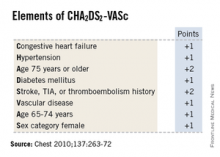

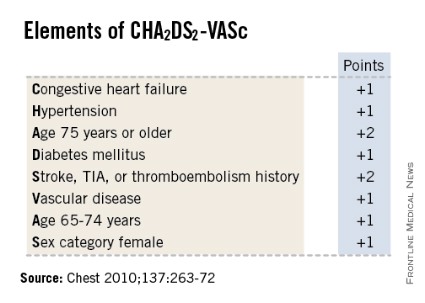

SNOWMASS, COLO. – High-sensitivity troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide levels are better predictors of stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation than the CHA2DS2-VASc score that will replace the CHADS2 score in the forthcoming revised American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.

Recent evidence indicates the biomarkers may be novel tools for improved stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation (AF), with prognostic value above and beyond that provided by the CHA2DS2-VASc scores.

These findings raise important unanswered questions about the relationship between AF and stroke. Conventional wisdom has held that left atrial thrombus is the cause of most strokes in patients with AF. But it’s not that simple, Dr. Bernard J. Gersh asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"What are we measuring with these biomarkers? This is what we really don’t understand. What has high-sensitivity troponin T got to do with left atrial thrombus?" asked Dr. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It seems increasingly clear that it’s not just the atrial arrhythmia that’s important in stroke risk, it’s also the company AF keeps. In a substantial but still uncertain proportion of patients, AF is a marker of vascular disease burden expressed through atrial and vascular endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, left atrial dilatation and fibrosis, and a hypercoagulable state, the cardiologist continued.

He was a coinvestigator on a couple of recent groundbreaking studies that show the prognostic power of biomarkers in predicting both stroke risk and cardiac death in AF patients.

In one report, the investigators looked at baseline high-sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) levels, clinical risk factors for stroke, and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in 12,892 patients with AF who were randomized to apixaban or warfarin in the prospective, double-blind ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:981-92). During a median 1.9 years of follow-up, patients in the highest quartile for baseline hsTnT had roughly a twofold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than did those in the lowest quartile.

Moreover, patients with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1 but in the top quartile for hsTnT, with a level in excess of 13 ng/L, had a very substantial stroke rate of 2.7% per year despite anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis) or warfarin. The relationship was even stronger for cardiac death, where subjects with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score who were in the top quartile for hsTnT had a 6% annual risk. A higher baseline hsTnT was also independently associated with sharply increased risk of major bleeding in a multivariate regression analysis (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:52-61).

In another recently published study, he and his international coworkers showed in ARISTOTLE participants with baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels that this biomarker also improved stroke prediction in AF, providing added value to CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Subjects in the top quartile for baseline NT-proBNP had an adjusted 2.35-fold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than those in the lowest quartile, irrespective of CHA2DS2-VASc score. They also had a 2.5-fold greater risk of cardiac death (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2274-84).

A study Dr. Gersh highlighted as "extremely interesting" involved the use of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a marker to rule out delayed AF in stroke patients. The study, led by investigators at the University Hospital Center of Nice (France) and known as TARGET-AF, included 300 consecutive acute stroke patients with no history of AF and no AF on their baseline ECG. During a median 6.8 days of in-hospital Holter monitoring, 17% of the stroke patients developed newly diagnosed AF.

The strongest predictor of delayed AF was baseline plasma BNP. It outperformed the CHA2DS2-VASc score and all the other parameters examined, including anterior circulation location of the stroke, P-wave initial force, gender, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, age, left atrial dilatation, and Score for the Targeting of AF (STAF) score. A BNP level greater than 131 pg/mL had a 98.1% sensitivity, 71.4% specificity, and 99.4% negative predictive value for delayed AF.

"Our data indicate that a BNP level of 131 pg/mL or less might rule out delayed AF in stroke survivors and could be included in algorithms for AF detection," the French investigators concluded (J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;22:e103-10).

There is plenty of direct evidence from transesophageal echocardiography studies and other sources that a substantial proportion of thromboemboli are directly the result of AF. However, indirect evidence points to additional causal factors. For example, there is a high incidence of thromboembolic events in AF patients without left atrial appendage thrombus. Plus, in natural history studies patients with AF without additional risk factors have a low incidence of stroke. And CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores predict vascular events but don’t correlate with left atrial appendage thrombus, Dr. Gersh noted.

He said the CHA2DS2-VASc score is clearly an improvement over CHADS2, and its adoption in the forthcoming ACC/AHA guidelines is to be welcomed. The CHA2DS2-VASc score increases the number of patients considered at significant risk of stroke and therefore warranting anticoagulation. For example, in a large Danish registry of nearly 48,000 AF patients with a CHADS2 score of 0-1 not on anticoagulation, patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 but a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 had twice the stroke risk of patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1 (Thromb. Haemost. 2012;107:1172-9).

That being said, neither risk score is all that impressive. The C-statistic, a measure of a test’s predictive power, is 0.56 for CHADS2 and it was 0.62 for CHA2DS2-VASc in the ARISTOTLE analysis. To put those figures in perspective, a coin toss has a C-statistic of 0.50.

"The individual predictive values are not good. We use CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc in practice and in the guidelines, but we should not pretend they are highly predictive. We need new risk stratification schemes," according to Dr. Gersh.

He reported serving as an adviser to Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical.

Evidence indicates that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care, namely the use of the CHADS2, and now the more refined CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification systems which use clinical risk factors to guide the prophylaxis decision. However, a body of evidence is growing that indicates these methods may provide relatively modest overall performance as predictors of stroke.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are three important considerations to these studies. Since the results were extrapolated from the ARISTOTLE trial, all patients were on anticoagulation, making it difficult to translate its findings on stroke risk and cardiac death. Thus, clear validation is needed for these novel biomarkers in settings in which no anticoagulation has been given within the study design before their use is incorporated into current guidelines.

Second, clinical trial settings are not always replicated in real world populations where patient inclusion criteria can differ significantly. For instance the very elderly, who have a higher stroke risk, were not represented in these studies.

Finally, although more robust risk-stratification systems have the potential to improve outcomes, it is important to remember ensuring their use is not guaranteed. Studies indicate that on average, only 50% of patients with AF are on risk appropriate prophylaxis.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Evidence indicates that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care, namely the use of the CHADS2, and now the more refined CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification systems which use clinical risk factors to guide the prophylaxis decision. However, a body of evidence is growing that indicates these methods may provide relatively modest overall performance as predictors of stroke.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are three important considerations to these studies. Since the results were extrapolated from the ARISTOTLE trial, all patients were on anticoagulation, making it difficult to translate its findings on stroke risk and cardiac death. Thus, clear validation is needed for these novel biomarkers in settings in which no anticoagulation has been given within the study design before their use is incorporated into current guidelines.

Second, clinical trial settings are not always replicated in real world populations where patient inclusion criteria can differ significantly. For instance the very elderly, who have a higher stroke risk, were not represented in these studies.

Finally, although more robust risk-stratification systems have the potential to improve outcomes, it is important to remember ensuring their use is not guaranteed. Studies indicate that on average, only 50% of patients with AF are on risk appropriate prophylaxis.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Evidence indicates that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care, namely the use of the CHADS2, and now the more refined CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification systems which use clinical risk factors to guide the prophylaxis decision. However, a body of evidence is growing that indicates these methods may provide relatively modest overall performance as predictors of stroke.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are three important considerations to these studies. Since the results were extrapolated from the ARISTOTLE trial, all patients were on anticoagulation, making it difficult to translate its findings on stroke risk and cardiac death. Thus, clear validation is needed for these novel biomarkers in settings in which no anticoagulation has been given within the study design before their use is incorporated into current guidelines.

Second, clinical trial settings are not always replicated in real world populations where patient inclusion criteria can differ significantly. For instance the very elderly, who have a higher stroke risk, were not represented in these studies.

Finally, although more robust risk-stratification systems have the potential to improve outcomes, it is important to remember ensuring their use is not guaranteed. Studies indicate that on average, only 50% of patients with AF are on risk appropriate prophylaxis.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – High-sensitivity troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide levels are better predictors of stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation than the CHA2DS2-VASc score that will replace the CHADS2 score in the forthcoming revised American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.

Recent evidence indicates the biomarkers may be novel tools for improved stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation (AF), with prognostic value above and beyond that provided by the CHA2DS2-VASc scores.

These findings raise important unanswered questions about the relationship between AF and stroke. Conventional wisdom has held that left atrial thrombus is the cause of most strokes in patients with AF. But it’s not that simple, Dr. Bernard J. Gersh asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"What are we measuring with these biomarkers? This is what we really don’t understand. What has high-sensitivity troponin T got to do with left atrial thrombus?" asked Dr. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It seems increasingly clear that it’s not just the atrial arrhythmia that’s important in stroke risk, it’s also the company AF keeps. In a substantial but still uncertain proportion of patients, AF is a marker of vascular disease burden expressed through atrial and vascular endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, left atrial dilatation and fibrosis, and a hypercoagulable state, the cardiologist continued.

He was a coinvestigator on a couple of recent groundbreaking studies that show the prognostic power of biomarkers in predicting both stroke risk and cardiac death in AF patients.

In one report, the investigators looked at baseline high-sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) levels, clinical risk factors for stroke, and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in 12,892 patients with AF who were randomized to apixaban or warfarin in the prospective, double-blind ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:981-92). During a median 1.9 years of follow-up, patients in the highest quartile for baseline hsTnT had roughly a twofold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than did those in the lowest quartile.

Moreover, patients with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1 but in the top quartile for hsTnT, with a level in excess of 13 ng/L, had a very substantial stroke rate of 2.7% per year despite anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis) or warfarin. The relationship was even stronger for cardiac death, where subjects with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score who were in the top quartile for hsTnT had a 6% annual risk. A higher baseline hsTnT was also independently associated with sharply increased risk of major bleeding in a multivariate regression analysis (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:52-61).

In another recently published study, he and his international coworkers showed in ARISTOTLE participants with baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels that this biomarker also improved stroke prediction in AF, providing added value to CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Subjects in the top quartile for baseline NT-proBNP had an adjusted 2.35-fold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than those in the lowest quartile, irrespective of CHA2DS2-VASc score. They also had a 2.5-fold greater risk of cardiac death (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2274-84).

A study Dr. Gersh highlighted as "extremely interesting" involved the use of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a marker to rule out delayed AF in stroke patients. The study, led by investigators at the University Hospital Center of Nice (France) and known as TARGET-AF, included 300 consecutive acute stroke patients with no history of AF and no AF on their baseline ECG. During a median 6.8 days of in-hospital Holter monitoring, 17% of the stroke patients developed newly diagnosed AF.

The strongest predictor of delayed AF was baseline plasma BNP. It outperformed the CHA2DS2-VASc score and all the other parameters examined, including anterior circulation location of the stroke, P-wave initial force, gender, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, age, left atrial dilatation, and Score for the Targeting of AF (STAF) score. A BNP level greater than 131 pg/mL had a 98.1% sensitivity, 71.4% specificity, and 99.4% negative predictive value for delayed AF.

"Our data indicate that a BNP level of 131 pg/mL or less might rule out delayed AF in stroke survivors and could be included in algorithms for AF detection," the French investigators concluded (J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;22:e103-10).

There is plenty of direct evidence from transesophageal echocardiography studies and other sources that a substantial proportion of thromboemboli are directly the result of AF. However, indirect evidence points to additional causal factors. For example, there is a high incidence of thromboembolic events in AF patients without left atrial appendage thrombus. Plus, in natural history studies patients with AF without additional risk factors have a low incidence of stroke. And CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores predict vascular events but don’t correlate with left atrial appendage thrombus, Dr. Gersh noted.

He said the CHA2DS2-VASc score is clearly an improvement over CHADS2, and its adoption in the forthcoming ACC/AHA guidelines is to be welcomed. The CHA2DS2-VASc score increases the number of patients considered at significant risk of stroke and therefore warranting anticoagulation. For example, in a large Danish registry of nearly 48,000 AF patients with a CHADS2 score of 0-1 not on anticoagulation, patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 but a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 had twice the stroke risk of patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1 (Thromb. Haemost. 2012;107:1172-9).

That being said, neither risk score is all that impressive. The C-statistic, a measure of a test’s predictive power, is 0.56 for CHADS2 and it was 0.62 for CHA2DS2-VASc in the ARISTOTLE analysis. To put those figures in perspective, a coin toss has a C-statistic of 0.50.

"The individual predictive values are not good. We use CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc in practice and in the guidelines, but we should not pretend they are highly predictive. We need new risk stratification schemes," according to Dr. Gersh.

He reported serving as an adviser to Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – High-sensitivity troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide levels are better predictors of stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation than the CHA2DS2-VASc score that will replace the CHADS2 score in the forthcoming revised American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.

Recent evidence indicates the biomarkers may be novel tools for improved stroke prediction in atrial fibrillation (AF), with prognostic value above and beyond that provided by the CHA2DS2-VASc scores.

These findings raise important unanswered questions about the relationship between AF and stroke. Conventional wisdom has held that left atrial thrombus is the cause of most strokes in patients with AF. But it’s not that simple, Dr. Bernard J. Gersh asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"What are we measuring with these biomarkers? This is what we really don’t understand. What has high-sensitivity troponin T got to do with left atrial thrombus?" asked Dr. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It seems increasingly clear that it’s not just the atrial arrhythmia that’s important in stroke risk, it’s also the company AF keeps. In a substantial but still uncertain proportion of patients, AF is a marker of vascular disease burden expressed through atrial and vascular endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, left atrial dilatation and fibrosis, and a hypercoagulable state, the cardiologist continued.

He was a coinvestigator on a couple of recent groundbreaking studies that show the prognostic power of biomarkers in predicting both stroke risk and cardiac death in AF patients.

In one report, the investigators looked at baseline high-sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) levels, clinical risk factors for stroke, and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in 12,892 patients with AF who were randomized to apixaban or warfarin in the prospective, double-blind ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:981-92). During a median 1.9 years of follow-up, patients in the highest quartile for baseline hsTnT had roughly a twofold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than did those in the lowest quartile.

Moreover, patients with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1 but in the top quartile for hsTnT, with a level in excess of 13 ng/L, had a very substantial stroke rate of 2.7% per year despite anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis) or warfarin. The relationship was even stronger for cardiac death, where subjects with a low-risk CHA2DS2-VASc score who were in the top quartile for hsTnT had a 6% annual risk. A higher baseline hsTnT was also independently associated with sharply increased risk of major bleeding in a multivariate regression analysis (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:52-61).

In another recently published study, he and his international coworkers showed in ARISTOTLE participants with baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels that this biomarker also improved stroke prediction in AF, providing added value to CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Subjects in the top quartile for baseline NT-proBNP had an adjusted 2.35-fold greater risk of stroke or systemic embolism than those in the lowest quartile, irrespective of CHA2DS2-VASc score. They also had a 2.5-fold greater risk of cardiac death (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2274-84).

A study Dr. Gersh highlighted as "extremely interesting" involved the use of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a marker to rule out delayed AF in stroke patients. The study, led by investigators at the University Hospital Center of Nice (France) and known as TARGET-AF, included 300 consecutive acute stroke patients with no history of AF and no AF on their baseline ECG. During a median 6.8 days of in-hospital Holter monitoring, 17% of the stroke patients developed newly diagnosed AF.

The strongest predictor of delayed AF was baseline plasma BNP. It outperformed the CHA2DS2-VASc score and all the other parameters examined, including anterior circulation location of the stroke, P-wave initial force, gender, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, age, left atrial dilatation, and Score for the Targeting of AF (STAF) score. A BNP level greater than 131 pg/mL had a 98.1% sensitivity, 71.4% specificity, and 99.4% negative predictive value for delayed AF.

"Our data indicate that a BNP level of 131 pg/mL or less might rule out delayed AF in stroke survivors and could be included in algorithms for AF detection," the French investigators concluded (J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;22:e103-10).

There is plenty of direct evidence from transesophageal echocardiography studies and other sources that a substantial proportion of thromboemboli are directly the result of AF. However, indirect evidence points to additional causal factors. For example, there is a high incidence of thromboembolic events in AF patients without left atrial appendage thrombus. Plus, in natural history studies patients with AF without additional risk factors have a low incidence of stroke. And CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores predict vascular events but don’t correlate with left atrial appendage thrombus, Dr. Gersh noted.

He said the CHA2DS2-VASc score is clearly an improvement over CHADS2, and its adoption in the forthcoming ACC/AHA guidelines is to be welcomed. The CHA2DS2-VASc score increases the number of patients considered at significant risk of stroke and therefore warranting anticoagulation. For example, in a large Danish registry of nearly 48,000 AF patients with a CHADS2 score of 0-1 not on anticoagulation, patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 but a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 had twice the stroke risk of patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1 (Thromb. Haemost. 2012;107:1172-9).

That being said, neither risk score is all that impressive. The C-statistic, a measure of a test’s predictive power, is 0.56 for CHADS2 and it was 0.62 for CHA2DS2-VASc in the ARISTOTLE analysis. To put those figures in perspective, a coin toss has a C-statistic of 0.50.

"The individual predictive values are not good. We use CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc in practice and in the guidelines, but we should not pretend they are highly predictive. We need new risk stratification schemes," according to Dr. Gersh.

He reported serving as an adviser to Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Approaching ventricular arrhythmias in a structurally normal heart

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Two generally benign forms of ventricular arrhythmia identifiable by their characteristic signatures on an electrocardiogram – and readily curable by catheter ablation – are ventricular tachycardia originating in the right ventricular outflow tract and premature ventricular contraction–induced cardiomyopathy, Dr. Samuel J. Asirvatham said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"I think these are two patterns of the ECG that you have to commit to memory. These are two patterns of ventricular tachycardia that are readily treatable, generally benign, and found in structurally normal hearts," said Dr. Asirvatham, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

• Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) ventricular tachycardia (VT): This arrhythmia arises in patients with no coronary artery disease and no valvular disease – in short, no structural heart disease at all. It is often exercise-provoked in males, and can be either exercise-provoked or hormonally cyclic in females. The common symptoms include palpitations and dizziness.

Dr. Asirvatham provided three ECG clues to the diagnosis. One is a negative V1 lead, indicative of delayed left ventricular activation, as seen in left bundle branch block. The second clue is a strong inferior axis, with the II and III aVF leads being positive. The third giveaway is negative leads at I aVR and II aVL, which indicates the impulse originated in the right ventricle and is simultaneously moving away from these two superior leads.

"You can sometimes treat RVOT VT with beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, but very often ablation is a better idea for these patients in order to save them from lifelong medications and breakthroughs. Usually if a single source in the ventricle is identified, ablation is a curative procedure," the cardiologist explained.

A caveat: The presence of a little R wave in V1 is a clue that the anatomic location of that patient’s premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) is likely going to make ablation challenging. The little R wave in V1 suggests the presence of a deep-tissue focus that needs to be targeted for ablation. It means the patient doesn’t have a complete left bundle branch block, perhaps because the origin of the impulse lies in remnants of embryologic conduction tissue located in the outflow tract, or in a sleeve of myocardium extending up the pulmonary artery. Addressing such a focus successfully via catheter ablation requires an advanced skill set.

• PVC-induced cardiomyopathy: This condition features PVCs plus runs of nonsustained VT and a depressed left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

"We have a classic chicken versus egg situation here: We know that when the heart is bad you get ventricular arrhythmias, but now we also understand that when you have ventricular arrhythmias it can make the heart bad. It’s our job to tease out which one is the primary culprit," according to Dr. Asirvatham.

The distinction is critical. If the arrhythmias are secondary to a bad heart, the patient should be directed down the pathway of heart failure management and possibly eventual transplantation. But if the cardiomyopathy is due to PVCs, it’s a condition that’s curable through ablation. In making the distinction, Dr. Asirvatham leans heavily on several factors: PVC morphology and coupling interval on the ECG, and total PVC burden over the course of 24 hours on Holter monitoring.

If the PVC morphology looks exactly the same beat after beat, chances are that the impulses are coming from one potentially ablatable spot, and that the ventricular dysfunction followed from the frequent PVCs. In contrast, if the impulses are multimorphic and arise from numerous locations, the likelihood is that the culprit is primary heart disease.

A VT rate in excess of 200 bpm is generally malignant, as is a coupling interval of less than 200 ms between the VT and the preceding normal QRS. Those, along with poly- or multimorphic VT, are worrisome features. In their absence, the key factor in determining whether PVCs are the cause of the patient’s cardiomyopathy or vice versa is how many PVCs there are.

"There’s no definite number, but in general it’s unusual to get cardiomyopathy in someone who has less than 10,000 PVCs per day. It’s more common when you get beyond 20,000 per day, and certainly beyond 30,000. Those are good numbers to keep in mind. The more PVCs you have per day, the more likely you are to get ventricular dysfunction. The corollary is also true: If ventricular dysfunction has occurred with frequent PVCs, once you get rid of the PVCs, in the vast majority of patients the ventricular function improves," according to the electrophysiologist.

On occasion, and with careful informed consent, it’s helpful to turn to empiric amiodarone to help sort out if a patient truly has PVC-induced cardiomyopathy.

"No one likes to prescribe amiodarone in a young patient with cardiomyopathy because amiodarone can produce bad things even when used for 3-6 months. But amiodarone is like an eraser for PVCs, and if, once the PVCs are gone, the ventricular function is still bad, then don’t waste time and put the patient at risk for the possibility of complications by doing a complex ablation. On the other hand, if, after giving amiodarone and the PVCs are gone the ventricular function normalizes, that’s very good evidence that ablation is worth the risk," he explained.

The results of catheter ablation of PVC-induced cardiomyopathy are often spectacular. Dr. Asirvatham recounted the story of a young adult patient whose LVEF had dropped to as low as 6%-8%. After ablation, it’s now 65%-plus and the patient is now an active surgical resident.

Dr. Asirvatham reported serving as a consultant to close to a dozen pharmaceutical and medical device companies.