User login

Digestive Disease Week (DDW 2014)

Reoperative Bariatric Surgery Yields Low Complication Rates

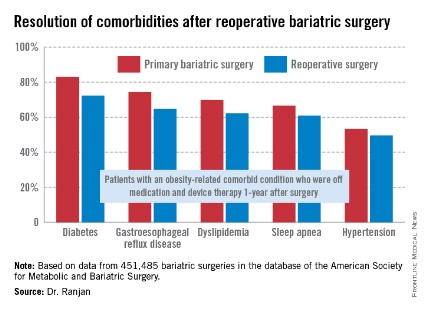

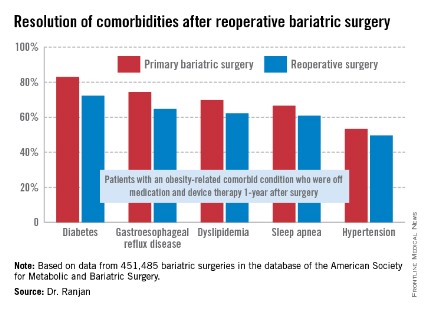

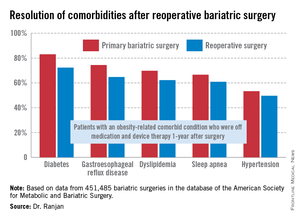

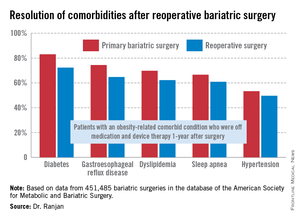

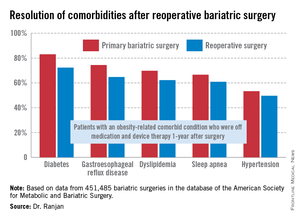

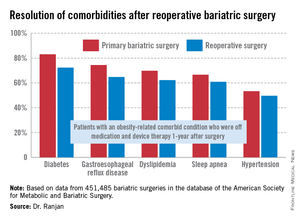

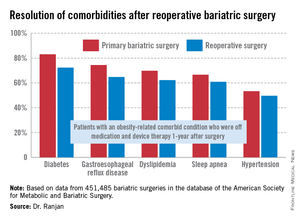

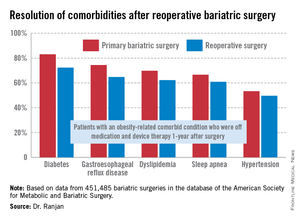

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT DDW 2014

Reoperative bariatric surgery yields low complication rates, substantial weight loss at 1 year

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Reoperative bariatric surgery has impressively low major morbidity and mortality, substantial 1-year weight loss, and a high rate of resolution of the common obesity-linked comorbid conditions, according to an analysis of a large national database.

These data demonstrate that outcomes after contemporary reoperative bariatric surgery are better than believed by insurance carriers, who often deny coverage for these procedures because of a misperception that complication rates are high and benefits uncertain, Dr. Ranjan Sudan said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"I think that these data need to get out there to the stakeholders," added Dr. Sudan, a bariatric surgeon and a digestive disorders specialist who is vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

He presented an analysis of outcomes after reoperative surgery that was carried out by a task force of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. He and his coinvestigators reviewed all 451,485 bariatric surgery operations entered into the society’s prospective database during a 5-year period ending in spring 2012. The procedures were performed by 1,029 participating surgeons at 709 U.S. hospitals.

The focus of this analysis was on the 6.3% of operations that were reoperations. A total of 70% of the reoperations were corrective operations, essentially redos of the same type of procedure performed initially. The other 30% were conversion procedures, as when a patient who had a gastric band procedure on the first go-round subsequently was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve procedure.

The mean length of stay for primary bariatric operations was 1.78 days, compared with 2.04 days for reoperative corrective procedures and 2.86 days for conversion operations.

The 30-day incidence of serious adverse events, such as leaks, bleeding, or pulmonary embolism, was 1.61% for primary procedures, nearly identical at 1.66% for corrective reoperations, and 3.26% for conversion procedures. The 1-year rate of serious adverse events was 1.87% for primary bariatric operations, 1.9% for corrective procedures, and 3.61% for conversions.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing a primary operation was 0.10% at 30 days and 0.17% at 1 year. Among patients who underwent reoperative bariatric surgery, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 0.14% and 0.26%, respectively.

"Most bariatric surgery patients do not need reoperations. It’s gratifying to see that among those who do, the severe complication rates were low and acceptable and comorbidities often resolved [see chart]," Dr. Sudan declared.

The 1-year rate of excess weight loss following reoperative surgery averaged 36%.

Discussant Dr. Alfons Pomp liked what he saw from the registry.

"Your data show just how good we as bariatric surgeons are to operate on these surgically difficult, very obese, and seriously ill patients, mostly laparoscopically, and get pretty amazing results," commented Dr. Pomp, professor of surgery and chief of GI metabolic and bariatric surgery at Cornell University in New York.

The registry study was funded by Covidien. Dr. Sudan reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT DDW 2014

Key clinical point: Reoperative bariatric surgery is considerably safer than previously recognized outside the specialist surgical community. The 1-year excess weight loss is substantial, and common obesity-related comorbidities often resolve.

Major finding: Mortality rates at 30 days and 1-year following reoperative bariatric surgery were just 0.14% and 0. 26%, with an average excess weight loss of 36%at 1 year.

Data source: This was an analysis of more than 450,000 consecutive bariatric surgery operations entered into a prospective national database. Reoperations accounted for 6.3% of the procedures.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Covidien. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Refining prognosis in small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors

CHICAGO – The extent of lymph node involvement provides independent prognostic information in patients with early-stage T1 or T2 small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors, according to a study involving nearly 3,000 lymph node–positive individuals.

This metric, best expressed as the lymph node ratio, or the number of positive nodes divided by the total number of lymph nodes examined, is not included in current European and American Joint Committee on Cancer staging classification guidelines. But it should be, Dr. Michelle K. Kim said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"The lymph node ratio is a readily available marker of disease progression. It’s available as part of usual clinical care; it’s not something extra you have to ask for. It may help identify patients who may require more-aggressive therapy," according to Dr. Kim of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

Current staging guidelines merely make a binary distinction: lymph node–positive or –negative. But previous studies in colon, gastric, and pancreatic cancers indicate the lymph node ratio (LNR) further differentiates outcomes in node-positive patients. The same now appears to be true for small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NETs), which are the most common of the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Indeed, the incidence of SI-NETs has tripled during the last 3 decades, she noted.

Dr. Kim presented an analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which included 2,984 patients with surgically resected lymph node–positive, metastasis-negative SI-NETs diagnosed in 1988-2010. Dr. Kim and coinvestigators classified patients into three LNR groups: 531 were LNR 1, defined as an LNR ratio of 0.2 or less; 1,525 patients were LNR 2, with a ratio of 0.21-0.5; and 928 were LNR 3, with a ratio greater than 0.5. Patients with T1 and T2 disease were overrepresented in the LNR 1 group.

The primary outcome in the study was disease-specific survival. The more-extensive the lymph node involvement in patients with T1 or T2 disease, the poorer their disease-specific survival. For example, LNR 1 patients with T1 or T2 SI-NETs were 1.6-fold more likely to experience disease-specific mortality during 10 years of follow-up than did a reference control group of node-negative T1/T2 patients, an elevation in risk that did not achieve statistical significance. However, the risk of disease-specific mortality was increased 2.29-fold in LNR 2 patients with T1/T2 disease and 4.52-fold in LNR 3 patients with T1/T2 SI-NETs, compared with node-negative controls, and those differences were significant.

In contrast, there was no difference in disease-specific survival according to LNR status in patients with more-advanced T3 or T4 disease.

This study was funded by Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The extent of lymph node involvement provides independent prognostic information in patients with early-stage T1 or T2 small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors, according to a study involving nearly 3,000 lymph node–positive individuals.

This metric, best expressed as the lymph node ratio, or the number of positive nodes divided by the total number of lymph nodes examined, is not included in current European and American Joint Committee on Cancer staging classification guidelines. But it should be, Dr. Michelle K. Kim said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"The lymph node ratio is a readily available marker of disease progression. It’s available as part of usual clinical care; it’s not something extra you have to ask for. It may help identify patients who may require more-aggressive therapy," according to Dr. Kim of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

Current staging guidelines merely make a binary distinction: lymph node–positive or –negative. But previous studies in colon, gastric, and pancreatic cancers indicate the lymph node ratio (LNR) further differentiates outcomes in node-positive patients. The same now appears to be true for small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NETs), which are the most common of the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Indeed, the incidence of SI-NETs has tripled during the last 3 decades, she noted.

Dr. Kim presented an analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which included 2,984 patients with surgically resected lymph node–positive, metastasis-negative SI-NETs diagnosed in 1988-2010. Dr. Kim and coinvestigators classified patients into three LNR groups: 531 were LNR 1, defined as an LNR ratio of 0.2 or less; 1,525 patients were LNR 2, with a ratio of 0.21-0.5; and 928 were LNR 3, with a ratio greater than 0.5. Patients with T1 and T2 disease were overrepresented in the LNR 1 group.

The primary outcome in the study was disease-specific survival. The more-extensive the lymph node involvement in patients with T1 or T2 disease, the poorer their disease-specific survival. For example, LNR 1 patients with T1 or T2 SI-NETs were 1.6-fold more likely to experience disease-specific mortality during 10 years of follow-up than did a reference control group of node-negative T1/T2 patients, an elevation in risk that did not achieve statistical significance. However, the risk of disease-specific mortality was increased 2.29-fold in LNR 2 patients with T1/T2 disease and 4.52-fold in LNR 3 patients with T1/T2 SI-NETs, compared with node-negative controls, and those differences were significant.

In contrast, there was no difference in disease-specific survival according to LNR status in patients with more-advanced T3 or T4 disease.

This study was funded by Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The extent of lymph node involvement provides independent prognostic information in patients with early-stage T1 or T2 small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors, according to a study involving nearly 3,000 lymph node–positive individuals.

This metric, best expressed as the lymph node ratio, or the number of positive nodes divided by the total number of lymph nodes examined, is not included in current European and American Joint Committee on Cancer staging classification guidelines. But it should be, Dr. Michelle K. Kim said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"The lymph node ratio is a readily available marker of disease progression. It’s available as part of usual clinical care; it’s not something extra you have to ask for. It may help identify patients who may require more-aggressive therapy," according to Dr. Kim of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

Current staging guidelines merely make a binary distinction: lymph node–positive or –negative. But previous studies in colon, gastric, and pancreatic cancers indicate the lymph node ratio (LNR) further differentiates outcomes in node-positive patients. The same now appears to be true for small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NETs), which are the most common of the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Indeed, the incidence of SI-NETs has tripled during the last 3 decades, she noted.

Dr. Kim presented an analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which included 2,984 patients with surgically resected lymph node–positive, metastasis-negative SI-NETs diagnosed in 1988-2010. Dr. Kim and coinvestigators classified patients into three LNR groups: 531 were LNR 1, defined as an LNR ratio of 0.2 or less; 1,525 patients were LNR 2, with a ratio of 0.21-0.5; and 928 were LNR 3, with a ratio greater than 0.5. Patients with T1 and T2 disease were overrepresented in the LNR 1 group.

The primary outcome in the study was disease-specific survival. The more-extensive the lymph node involvement in patients with T1 or T2 disease, the poorer their disease-specific survival. For example, LNR 1 patients with T1 or T2 SI-NETs were 1.6-fold more likely to experience disease-specific mortality during 10 years of follow-up than did a reference control group of node-negative T1/T2 patients, an elevation in risk that did not achieve statistical significance. However, the risk of disease-specific mortality was increased 2.29-fold in LNR 2 patients with T1/T2 disease and 4.52-fold in LNR 3 patients with T1/T2 SI-NETs, compared with node-negative controls, and those differences were significant.

In contrast, there was no difference in disease-specific survival according to LNR status in patients with more-advanced T3 or T4 disease.

This study was funded by Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts.

AT DDW 2014

Key clinical point: The extent of lymph node involvement provides important independent prognostic information in patients with early-stage, T1, or T2 small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors.

Major finding: The risk of disease-specific mortality jumped up to 4.5-fold depending on the extent of lymph node involvement in patients with T1 or T2 small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors.

Data source: This study involved retrospective analysis of SEER data on 2,984 patients with surgically resected lymph node-positive, metastasis-negative small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Olmesartan can cause celiac disease mimicker

CHICAGO – The antihypertensive agent olmesartan is associated with increased risk of a severe sprue-like enteropathy, as highlighted in a nationwide French cohort study.

This olmesartan-related illness is characterized by villous atrophy, severe chronic diarrhea, and weight loss, with negative serology for celiac disease.

The hospitalization rate for this disorder is time dependent. The risk doesn’t increase significantly until after the first year on therapy but climbs steeply thereafter, Dr. Myriam Mezzarobba reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Importantly, angiotensin receptor blockers other than olmesartan (Benicar) were not associated with an increased risk of severe intestinal malabsorption in the French study. Neither were ACE inhibitors, added Dr. Mezzarobba of the French National Health Insurance Fund, Paris.

A few prior reports based on relatively limited patient numbers and/or short follow-up have indicated conflicting results regarding a possible association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption. This controversy provided the impetus for Dr. Mezzarobba and coinvestigators to conduct a cohort study harnessing the database of SNIIRAM, the French national health insurance plan covering 50 million residents, with linkage to the country’s centralized hospitalization database.

The investigators zeroed in on 4.5 million patients who started on an angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitor during 2007-2012. During more than 9 million person-years of follow-up, 218 of these individuals were hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of intestinal malabsorption.

The incidence rate for this outcome among patients on olmesartan was 2.6 cases per 100,000 person-years during their first year on the medication, rising to 6.7 per 100,000 person-years during the second year and 8.9 per 100,000 person-years after 2 years on the drug.

In contrast, the rates among patients on other angiotensin receptor blockers were 2.1, 2.0, and 1.5 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, during the same treatment duration periods. And in patients on an ACE inhibitor, the rates were 3.7, 2.0, and 0.9 cases per 100,000 person-years during the first, second, and beyond the second year on therapy.

In a regression analysis controlled for age and sex, the adjusted rate ratio for hospitalization for intestinal malabsorption in patients on olmesartan compared with those on an ACE inhibitor was 0.7 for those on medication for less than a year, 3.3 during years 1-2, and 10.3 for those on olmesartan for longer than 2 years.

The typical pattern of this disorder is clinical and histologic remission following olmesartan discontinuation, Dr. Mezzarobba noted.

Session discussant Dr. Benjamin Lebwohl stressed that the French study holds a key lesson for gastroenterologists everywhere.

"Lest we become very aggressive in our case finding for celiac disease – and many of us are now looking more closely for this disease – we need to remember that villous atrophy is not always due to celiac disease," said Dr. Lebwohl, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University, New York.

He characterized the association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption found in the French national study as "robust," adding: "Importantly, this risk was not an acute risk. It increased over time. This is not an acute drug reaction, this is something that can develop at any point, even years after starting olmesartan."

Dr. Mezzarobba and Dr. Lebwohl reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The antihypertensive agent olmesartan is associated with increased risk of a severe sprue-like enteropathy, as highlighted in a nationwide French cohort study.

This olmesartan-related illness is characterized by villous atrophy, severe chronic diarrhea, and weight loss, with negative serology for celiac disease.

The hospitalization rate for this disorder is time dependent. The risk doesn’t increase significantly until after the first year on therapy but climbs steeply thereafter, Dr. Myriam Mezzarobba reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Importantly, angiotensin receptor blockers other than olmesartan (Benicar) were not associated with an increased risk of severe intestinal malabsorption in the French study. Neither were ACE inhibitors, added Dr. Mezzarobba of the French National Health Insurance Fund, Paris.

A few prior reports based on relatively limited patient numbers and/or short follow-up have indicated conflicting results regarding a possible association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption. This controversy provided the impetus for Dr. Mezzarobba and coinvestigators to conduct a cohort study harnessing the database of SNIIRAM, the French national health insurance plan covering 50 million residents, with linkage to the country’s centralized hospitalization database.

The investigators zeroed in on 4.5 million patients who started on an angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitor during 2007-2012. During more than 9 million person-years of follow-up, 218 of these individuals were hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of intestinal malabsorption.

The incidence rate for this outcome among patients on olmesartan was 2.6 cases per 100,000 person-years during their first year on the medication, rising to 6.7 per 100,000 person-years during the second year and 8.9 per 100,000 person-years after 2 years on the drug.

In contrast, the rates among patients on other angiotensin receptor blockers were 2.1, 2.0, and 1.5 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, during the same treatment duration periods. And in patients on an ACE inhibitor, the rates were 3.7, 2.0, and 0.9 cases per 100,000 person-years during the first, second, and beyond the second year on therapy.

In a regression analysis controlled for age and sex, the adjusted rate ratio for hospitalization for intestinal malabsorption in patients on olmesartan compared with those on an ACE inhibitor was 0.7 for those on medication for less than a year, 3.3 during years 1-2, and 10.3 for those on olmesartan for longer than 2 years.

The typical pattern of this disorder is clinical and histologic remission following olmesartan discontinuation, Dr. Mezzarobba noted.

Session discussant Dr. Benjamin Lebwohl stressed that the French study holds a key lesson for gastroenterologists everywhere.

"Lest we become very aggressive in our case finding for celiac disease – and many of us are now looking more closely for this disease – we need to remember that villous atrophy is not always due to celiac disease," said Dr. Lebwohl, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University, New York.

He characterized the association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption found in the French national study as "robust," adding: "Importantly, this risk was not an acute risk. It increased over time. This is not an acute drug reaction, this is something that can develop at any point, even years after starting olmesartan."

Dr. Mezzarobba and Dr. Lebwohl reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The antihypertensive agent olmesartan is associated with increased risk of a severe sprue-like enteropathy, as highlighted in a nationwide French cohort study.

This olmesartan-related illness is characterized by villous atrophy, severe chronic diarrhea, and weight loss, with negative serology for celiac disease.

The hospitalization rate for this disorder is time dependent. The risk doesn’t increase significantly until after the first year on therapy but climbs steeply thereafter, Dr. Myriam Mezzarobba reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Importantly, angiotensin receptor blockers other than olmesartan (Benicar) were not associated with an increased risk of severe intestinal malabsorption in the French study. Neither were ACE inhibitors, added Dr. Mezzarobba of the French National Health Insurance Fund, Paris.

A few prior reports based on relatively limited patient numbers and/or short follow-up have indicated conflicting results regarding a possible association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption. This controversy provided the impetus for Dr. Mezzarobba and coinvestigators to conduct a cohort study harnessing the database of SNIIRAM, the French national health insurance plan covering 50 million residents, with linkage to the country’s centralized hospitalization database.

The investigators zeroed in on 4.5 million patients who started on an angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitor during 2007-2012. During more than 9 million person-years of follow-up, 218 of these individuals were hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of intestinal malabsorption.

The incidence rate for this outcome among patients on olmesartan was 2.6 cases per 100,000 person-years during their first year on the medication, rising to 6.7 per 100,000 person-years during the second year and 8.9 per 100,000 person-years after 2 years on the drug.

In contrast, the rates among patients on other angiotensin receptor blockers were 2.1, 2.0, and 1.5 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, during the same treatment duration periods. And in patients on an ACE inhibitor, the rates were 3.7, 2.0, and 0.9 cases per 100,000 person-years during the first, second, and beyond the second year on therapy.

In a regression analysis controlled for age and sex, the adjusted rate ratio for hospitalization for intestinal malabsorption in patients on olmesartan compared with those on an ACE inhibitor was 0.7 for those on medication for less than a year, 3.3 during years 1-2, and 10.3 for those on olmesartan for longer than 2 years.

The typical pattern of this disorder is clinical and histologic remission following olmesartan discontinuation, Dr. Mezzarobba noted.

Session discussant Dr. Benjamin Lebwohl stressed that the French study holds a key lesson for gastroenterologists everywhere.

"Lest we become very aggressive in our case finding for celiac disease – and many of us are now looking more closely for this disease – we need to remember that villous atrophy is not always due to celiac disease," said Dr. Lebwohl, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University, New York.

He characterized the association between olmesartan and severe intestinal malabsorption found in the French national study as "robust," adding: "Importantly, this risk was not an acute risk. It increased over time. This is not an acute drug reaction, this is something that can develop at any point, even years after starting olmesartan."

Dr. Mezzarobba and Dr. Lebwohl reported having no financial conflicts.

AT DDW 2014

Key clinical point: When patients on olmesartan develop severe intestinal malabsorption with villous atrophy in the absence of positive serology for celiac disease, think drug side effect, even with onset after years of problem-free medication use.

Major finding: The adjusted risk of hospitalization for intestinal malabsorption in patients on olmesartan was 3.3-fold greater than in individuals on an ACE inhibitor during years 1-2 of treatment and 10.3-fold greater after more than 2 years of treatment.

Data source: A French nationwide cohort study of more than 4.5 million patients on an angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitor with 9 million person-years of follow-up.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the University of Paris and the French National Health Insurance Fund. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Resuming aspirin for cardioprotection after GI bleed tied to 38% cut in CV risk

CHICAGO – New data shine a light on the trade-offs involved in resuming low-dose aspirin therapy for secondary cardiovascular prevention following a lower gastrointestinal bleeding event.

Going back onto daily low-dose aspirin was associated with a 2.7-fold greater risk of recurrent lower GI bleeding than no use of aspirin during 5 years of follow-up. However, the risk of a major cardiovascular event – nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke or death due to a vascular cause – was reduced by 38%. Moreover, the rate of death due to nonvascular causes was 3.2-fold lower among the aspirin-using group, Dr. Francis K.L. Chan reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

He presented a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 295 patients who developed endoscopically confirmed lower GI bleeding while on low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention. A total of 174 subjects in this observational study resumed aspirin and 121 did not.

The two groups were similar in terms of their cardiovascular risk profiles based upon conventional risk factors. However, the aspirin nonusers, with a mean age of 76 years, were on average 3 years older than those who resumed aspirin. The nonusers were also more likely to have had a severe index lower GI bleed requiring transfusion of more than 2 units of blood products, by a margin of 55%-40%. An upper GI bleeding source was excluded by endoscopy in all participants, noted Dr. Chan of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 18.9% among the aspirin users, compared with 6.9% in the nonusers. The incidence of a major cardiovascular event was 22.8% in the aspirin group versus 36.5% among aspirin nonusers. And the 5-year incidence of death due to nonvascular causes was 8.2% in the aspirin users, compared with 26.7% in nonusers.

The nature of the Hong Kong health care system is such that all outcomes of interest were reliably captured. Eighty-four percent of patients in the aspirin user group received prescriptions for aspirin during at least 75% of the follow-up period, while 87% of the nonuser group received aspirin during 10% or less of the study period.

Audience members praised Dr. Chan for providing "clear-cut" and "very significant" findings addressing the previously unanswered but clinically important question of the risks and benefits of aspirin resumption versus nonuse following a lower GI bleed occurring while on therapy.

The study was carried out with institutional funds. Dr. Chan is on speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Takeda, and Eisai.

CHICAGO – New data shine a light on the trade-offs involved in resuming low-dose aspirin therapy for secondary cardiovascular prevention following a lower gastrointestinal bleeding event.

Going back onto daily low-dose aspirin was associated with a 2.7-fold greater risk of recurrent lower GI bleeding than no use of aspirin during 5 years of follow-up. However, the risk of a major cardiovascular event – nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke or death due to a vascular cause – was reduced by 38%. Moreover, the rate of death due to nonvascular causes was 3.2-fold lower among the aspirin-using group, Dr. Francis K.L. Chan reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

He presented a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 295 patients who developed endoscopically confirmed lower GI bleeding while on low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention. A total of 174 subjects in this observational study resumed aspirin and 121 did not.

The two groups were similar in terms of their cardiovascular risk profiles based upon conventional risk factors. However, the aspirin nonusers, with a mean age of 76 years, were on average 3 years older than those who resumed aspirin. The nonusers were also more likely to have had a severe index lower GI bleed requiring transfusion of more than 2 units of blood products, by a margin of 55%-40%. An upper GI bleeding source was excluded by endoscopy in all participants, noted Dr. Chan of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 18.9% among the aspirin users, compared with 6.9% in the nonusers. The incidence of a major cardiovascular event was 22.8% in the aspirin group versus 36.5% among aspirin nonusers. And the 5-year incidence of death due to nonvascular causes was 8.2% in the aspirin users, compared with 26.7% in nonusers.

The nature of the Hong Kong health care system is such that all outcomes of interest were reliably captured. Eighty-four percent of patients in the aspirin user group received prescriptions for aspirin during at least 75% of the follow-up period, while 87% of the nonuser group received aspirin during 10% or less of the study period.

Audience members praised Dr. Chan for providing "clear-cut" and "very significant" findings addressing the previously unanswered but clinically important question of the risks and benefits of aspirin resumption versus nonuse following a lower GI bleed occurring while on therapy.

The study was carried out with institutional funds. Dr. Chan is on speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Takeda, and Eisai.

CHICAGO – New data shine a light on the trade-offs involved in resuming low-dose aspirin therapy for secondary cardiovascular prevention following a lower gastrointestinal bleeding event.

Going back onto daily low-dose aspirin was associated with a 2.7-fold greater risk of recurrent lower GI bleeding than no use of aspirin during 5 years of follow-up. However, the risk of a major cardiovascular event – nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke or death due to a vascular cause – was reduced by 38%. Moreover, the rate of death due to nonvascular causes was 3.2-fold lower among the aspirin-using group, Dr. Francis K.L. Chan reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

He presented a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 295 patients who developed endoscopically confirmed lower GI bleeding while on low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention. A total of 174 subjects in this observational study resumed aspirin and 121 did not.

The two groups were similar in terms of their cardiovascular risk profiles based upon conventional risk factors. However, the aspirin nonusers, with a mean age of 76 years, were on average 3 years older than those who resumed aspirin. The nonusers were also more likely to have had a severe index lower GI bleed requiring transfusion of more than 2 units of blood products, by a margin of 55%-40%. An upper GI bleeding source was excluded by endoscopy in all participants, noted Dr. Chan of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 18.9% among the aspirin users, compared with 6.9% in the nonusers. The incidence of a major cardiovascular event was 22.8% in the aspirin group versus 36.5% among aspirin nonusers. And the 5-year incidence of death due to nonvascular causes was 8.2% in the aspirin users, compared with 26.7% in nonusers.

The nature of the Hong Kong health care system is such that all outcomes of interest were reliably captured. Eighty-four percent of patients in the aspirin user group received prescriptions for aspirin during at least 75% of the follow-up period, while 87% of the nonuser group received aspirin during 10% or less of the study period.

Audience members praised Dr. Chan for providing "clear-cut" and "very significant" findings addressing the previously unanswered but clinically important question of the risks and benefits of aspirin resumption versus nonuse following a lower GI bleed occurring while on therapy.

The study was carried out with institutional funds. Dr. Chan is on speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Takeda, and Eisai.

AT DDW 2014

Key clinical point: What’s the risk/benefit balance in restarting low-dose aspirin for secondary cardioprevention following a lower GI bleed? New data provide the answer to this common clinical dilemma.

Major finding: Resuming low-dose aspirin in patients after a lower GI bleed was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk of a recurrent bleed within 5 years, but a 38% reduction in the risk of a major cardiovascular event, compared with aspirin discontinuation.

Data source: This was a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 295 patients with a history of a lower GI bleed while on low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prophylaxis.

Disclosures: The study was carried out with institutional funds. Dr. Chan is on speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Takeda, and Eisai.

Screen for Barrett’s in All With Central Obesity?

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT DDW 2014

Screen for Barrett’s in all with central obesity?

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – The prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus is comparable in individuals regardless of whether they have gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, according to a population-based study.

"These results directly challenge the established GERD-based Barrett’s esophagus screening paradigm and provide strong rationale for using central obesity in Caucasian males with or without symptomatic GERD as criteria for Barrett’s esophagus screening," Dr. Nicholas R. Crews said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"In this study, waist-hip ratio was our surrogate marker for central obesity. It’s easily obtainable and usable in clinical practice," noted Dr. Crews of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Barrett’s esophagus is the precursor lesion and principal risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a malignancy whose incidence in the United States and other developed nations is increasing at an alarming rate. Improved methods of screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma are sorely needed, he added.

Dr. Crews presented a study in which a representative sample of Olmsted County, Minn., residents over age 50 with no history of endoscopy were randomized to screening for Barrett’s esophagus by one of three methods: sedated endoscopy in the GI suite, unsedated transnasal endoscopy in the clinic, or unsedated transnasal endoscopy in a Mayo mobile research van.

Participants’ mean age was 70 years, 46% were men, 206 of the 209 were white, and only one-third of subjects had GERD symptoms.

The prevalence of esophagitis grades A-C proved to be 32% in the symptomatic GERD group and similar at 29% in those without GERD symptoms. Similarly, Barrett’s esophagus was identified in 8.7% of the symptomatic GERD group and 7.9% of subjects without GERD symptoms. Dysplasia was present in 1.4% of each group. The mean length of the esophageal segment with Barrett’s esophagus was 2.4 cm in patients with GERD symptoms and not significantly different in those who were asymptomatic.

Three risk factors proved significant as predictors of esophageal injury as defined by esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus: male sex, central obesity as defined by a waist-hip ratio greater than 0.9, and consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day. Age, smoking status, and body mass index were not predictive.

The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Audience members expressed skepticism about the notion of routinely screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals with central obesity in an era of an unprecedented obesity epidemic.

For example, Dr. Joel E. Richter, who described himself as "an anti-Barrett’s person," commented that he believes gastroenterologists are already overdiagnosing and overtreating the condition, needlessly alarming many patients.

In women, particularly, it’s increasingly clear that Barrett’s esophagus only rarely develops into esophageal adenocarcinoma, he said.

"Others have said that women with Barrett’s esophagus are as likely to get esophageal cancer as men are to get breast cancer," commented Dr. Richter, professor of internal medicine and director of the center for swallowing disorders at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Another audience member told Dr. Crews, "I totally agree with you that we miss most people with Barrett’s by our current screening process. The problem is, it’s unclear whether it’s important or not to find them. To extrapolate from your study and say that anyone with central obesity ought to be screened for [Barrett’s esophagus] is a little strong, I think."

"It’s very controversial," Dr. Crews agreed. "It’s something we continue to struggle with."

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT DDW 2014

Key clinical point: The current recommended strategy of screening for Barrett’s esophagus on the basis of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux is called into question by a new study showing the esophageal cancer precursor lesion is just as common in screened asymptomatic individuals.

Major finding: The mean waist-to-hip ratio was 0.89 in screened subjects with no esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, 0.91 in those with positive endoscopic findings and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, and 0.95 in those with positive findings who were asymptomatic.

Data source: This was a prospective population-based study in which 209 individuals over age 50 with no history of endoscopy, two-thirds of whom had no gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, underwent screening endoscopy.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Increased intestinal permeability is central to alcoholic hepatitis

CHICAGO – Why is it that only about 20% of individuals who consume 10 or more alcoholic drinks daily for years on end will develop alcoholic hepatitis?

New insight into the mechanism of this disease points to markedly increased intestinal permeability as playing a key role. Increased intestinal permeability is consistently present in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, but not in heavy drinkers without the disease or in normal healthy controls, Dr. George Holman reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

"Our study suggests that intestinal permeability is disrupted in alcoholic hepatitis. We speculate that increased intestinal permeability allows passage of lipopolysaccharides from gut bacteria into the serum. These endotoxins are carried to the liver and cause subsequent hepatic inflammation," according to Dr. Holman of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

Alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by steatohepatitis and rapid clinical decompensation. It is typically seen only in patients who have consumed more than 100 g of alcohol – that’s roughly 10 drinks – daily for years.

Dr. Holman presented a prospective case-control study involving 22 patients hospitalized for severe alcoholic hepatitis and 33 healthy volunteers. The study hypothesis was that patients with alcoholic hepatitis have defective intestinal barrier function which allows gut-derived bacterial endotoxins, known as lipopolysaccharides, to enter the systemic circulation, leading to a resultant inflammatory response in the liver.

To test this hypothesis, the investigators utilized urinary excretion of lactulose and mannitol as intestinal permeability markers. They also measured serum lipopolysaccharide levels as well as circulating levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha.

The alcoholic hepatitis group showed on average an eightfold increase in intestinal permeability as measured by the lactulose/mannitol excretion ratio, compared with controls. Also, a near-perfect linear correlation was found between the degree of intestinal permeability and the magnitude of the elevation in serum lipopolysaccharide levels. Paralleling these increases in intestinal permeability and lipopolysaccharides, serum levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha were also significantly higher in the alcoholic hepatitis patients than in controls. These data, taken as a whole, point to increased intestinal permeability as a pathogenic factor resulting in endotoxemia and immune activation, he said.

Also worthy of note, intestinal permeability tracked with MELD (model for end-stage liver disease) scores such that as intestinal permeability increased, MELD scores climbed nearly exponentially, Dr. Holman continued.

Audience members wondered whether treating alcoholic hepatitis patients, typically with prednisone or pentoxifylline, had a favorable impact upon their abnormal intestinal permeability. Dr. Holman replied that although he and his coinvestigators had planned to look at this issue, follow-up simply wasn’t possible. This was a very sick patient cohort – their mean alcohol consumption was 26 drinks daily for years – and despite treatment, nearly half of them were dead within several months. However, other investigators have previously shown that alcoholic hepatitis patients who respond favorably to treatment and are able to leave the hospital show a decrease in their previously high endotoxin levels, while more severely affected patients do not.