User login

Decision rule identifies unprovoked VTE patients who can halt anticoagulation

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

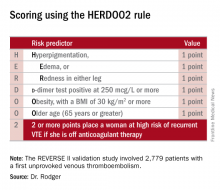

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Half of women who have a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule.

Major finding: Women with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism identified as being at low risk of recurrence on the basis of the HERDOO2 decision rule had a 3% recurrence rate in the year after stopping anticoagulation therapy, while those identified as high risk had an 8.1% recurrence rate if they discontinued anticoagulants.

Data source: This was a prospective, multinational, observational study involving 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study.

First-generation DES looking good at 10 years

ROME – There’s good news for the millions of patients living with a first-generation metallic drug-eluting stent for coronary revascularization implanted in years past: The devices perform reassuringly well a full decade after implantation, Lorenz Räber, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

That’s the key message of the SIRTAX VERY LATE study, the only randomized trial of first-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) that didn’t turn out the lights at a maximum of 5 years of follow-up. In fact, at the 10-year mark, SIRTAX VERY LATE shows that regardless of whether the first-generation DES was paclitaxel- or sirolimus-eluting, the risk of major adverse cardiac events due to device failure was substantially lower in the second half-decade than in the first 5 years after deployment, according to Dr. Räber of Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

More specifically, the cumulative risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization was 14.6% at 5 years and 17.7% at 10 years, while the 5- and 10-year cumulative risks of definite stent thrombosis were 4.5% and 5.6%, respectively.

The annual risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization dropped by 64%, from 1.8%/year during years 1-5 to 0.7% during years 6-10. Similarly, the annual risk of definite stent thrombosis fell from 0.67%/year to 0.23%/year after year 5, a 69% relative risk reduction. And importantly, these attenuations in risk occurred independent of age.

“The lower risk of late clinical events suggests stabilization of delayed arterial healing over time after first-generation DES implantation, with reduced chronic inflammation and neoatherosclerosis,” he said.

This is reassuring in light of the stormy history of the first-generation DES. Three years after the devices came on the U.S. market, the so-called ESC firestorm erupted. At the 2006 ESC congress, investigators presented meta-analyses suggesting the devices carried a possible late increased thrombotic risk beyond the then-recommended 3-6 months of prescribed dual-antiplatelet therapy. The use of these devices declined sharply in response, even though a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel charged with looking at the totality of evidence concluded that concerns about thrombosis didn’t outweigh the benefits of the first-generation DES over bare-metal stents.

The reductions in very late stent thrombosis and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization beyond 5 years seen in the SIRTAX VERY LATE trial occurred despite the fact that only 15% of patients were on dual-antiplatelet therapy throughout the first 5 years and 11% were on dual-antiplatelet therapy afterwards, Dr. Räber noted.

“Our findings may have implications for secondary prevention after PCI with a first-generation DES, including the need for long-term antiplatelet therapy,” the cardiologist added.

The previously reported 5-year results of SIRTAX (the Sirolimus-Eluting Versus Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization trial) showed a steady increase over time in late lumen loss and an ongoing risk of very late stent thrombosis (Circulation. 2011 Jun 21;123(24):2819-28). Much the same was seen at the 5-year mark in the other major trials of first-generation DES, including RAVEL, SIRIUS, and TAXUS.

However, all those studies ended at 5 years, leaving unanswered the key question of what happens later. Cardiologists have wondered if the first-generation DES they put in their patients years ago were associated with a continued steady climb in the risk of device-related adverse events, or if the risk plateaued or even dropped off. The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was conducted in order to provide answers.

SIRTAX included 1,012 Swiss patients randomized to coronary revascularization using a first-generation sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stent in 2003-2004. Roughly half had stable coronary artery disease and half presented with acute coronary syndromes. The 10-year follow-up conducted in the SIRTAX VERY LATE study captured 895 (88%) of the original 1,012 subjects.

The cumulative incidence of major cardiac adverse events – a composite of cardiac death, MI, and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization – was 20.8% at 5 years and 33.8% at 10 years. The rate was similar between years 1-5 and 6-10.

The cumulative all-cause mortality rate was 10.4% at 5 years and 24.2% at 10 years. The rate was 2.0%/year during years 1-5 and accelerated significantly to 3.1%/year in years 6-10. However, this increase appears to be largely due to the background impact of advancing age rather than to any effect of having a first-generation DES. The 5- and 10-year all-cause mortality rates in the age- and sex-matched general Swiss population are similar to those seen in SIRTAX VERY LATE, at 9.6% and 22.1%, respectively, the cardiologist observed.

The cumulative incidence of MI in the study population was 7% at 5 years and 9.7% at 10 years. Between years 1-5 the rate was 0.9%/year, dropping to 0.6%/year during years 6-10.

One of the useful potential purposes for the new SIRTAX VERY LATE follow-up data beyond 5 years is that the results could serve as a benchmark in evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of the much newer drug-eluting fully bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, since the potential benefits of these new devices may not appear until relatively late, after the devices themselves have disappeared. SIRTAX VERY LATE sets the bar for stent-related adverse events 5 years or more after device implantation at an annual risk of less than 0.3%/year for stent thrombosis and less than 1%/year for ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization.

Session co-chair Hector Bueno, MD, drew attention to the fact that no significant differences in clinical outcomes were seen at either 5 or 10 years between the sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stent recipients. That’s noteworthy because more than a decade ago when the primary endpoint of SIRTAX was reported, much was made of the finding that the 9-month rate of major adverse cardiac events was significantly lower in the sirolimus-eluting stent group (N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 18;353[7]:653-62). Over time, any outcome differences between the two devices were erased, observed Dr. Bueno of Complutense University of Madrid.

The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was funded by grants from Bern University Hospital. Dr. Räber reported having no relevant financial interests.

Simultaneously with his presentation in Rome at ESC 2016, the study results were published online (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw343).

ROME – There’s good news for the millions of patients living with a first-generation metallic drug-eluting stent for coronary revascularization implanted in years past: The devices perform reassuringly well a full decade after implantation, Lorenz Räber, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

That’s the key message of the SIRTAX VERY LATE study, the only randomized trial of first-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) that didn’t turn out the lights at a maximum of 5 years of follow-up. In fact, at the 10-year mark, SIRTAX VERY LATE shows that regardless of whether the first-generation DES was paclitaxel- or sirolimus-eluting, the risk of major adverse cardiac events due to device failure was substantially lower in the second half-decade than in the first 5 years after deployment, according to Dr. Räber of Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

More specifically, the cumulative risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization was 14.6% at 5 years and 17.7% at 10 years, while the 5- and 10-year cumulative risks of definite stent thrombosis were 4.5% and 5.6%, respectively.

The annual risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization dropped by 64%, from 1.8%/year during years 1-5 to 0.7% during years 6-10. Similarly, the annual risk of definite stent thrombosis fell from 0.67%/year to 0.23%/year after year 5, a 69% relative risk reduction. And importantly, these attenuations in risk occurred independent of age.

“The lower risk of late clinical events suggests stabilization of delayed arterial healing over time after first-generation DES implantation, with reduced chronic inflammation and neoatherosclerosis,” he said.

This is reassuring in light of the stormy history of the first-generation DES. Three years after the devices came on the U.S. market, the so-called ESC firestorm erupted. At the 2006 ESC congress, investigators presented meta-analyses suggesting the devices carried a possible late increased thrombotic risk beyond the then-recommended 3-6 months of prescribed dual-antiplatelet therapy. The use of these devices declined sharply in response, even though a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel charged with looking at the totality of evidence concluded that concerns about thrombosis didn’t outweigh the benefits of the first-generation DES over bare-metal stents.

The reductions in very late stent thrombosis and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization beyond 5 years seen in the SIRTAX VERY LATE trial occurred despite the fact that only 15% of patients were on dual-antiplatelet therapy throughout the first 5 years and 11% were on dual-antiplatelet therapy afterwards, Dr. Räber noted.

“Our findings may have implications for secondary prevention after PCI with a first-generation DES, including the need for long-term antiplatelet therapy,” the cardiologist added.

The previously reported 5-year results of SIRTAX (the Sirolimus-Eluting Versus Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization trial) showed a steady increase over time in late lumen loss and an ongoing risk of very late stent thrombosis (Circulation. 2011 Jun 21;123(24):2819-28). Much the same was seen at the 5-year mark in the other major trials of first-generation DES, including RAVEL, SIRIUS, and TAXUS.

However, all those studies ended at 5 years, leaving unanswered the key question of what happens later. Cardiologists have wondered if the first-generation DES they put in their patients years ago were associated with a continued steady climb in the risk of device-related adverse events, or if the risk plateaued or even dropped off. The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was conducted in order to provide answers.

SIRTAX included 1,012 Swiss patients randomized to coronary revascularization using a first-generation sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stent in 2003-2004. Roughly half had stable coronary artery disease and half presented with acute coronary syndromes. The 10-year follow-up conducted in the SIRTAX VERY LATE study captured 895 (88%) of the original 1,012 subjects.

The cumulative incidence of major cardiac adverse events – a composite of cardiac death, MI, and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization – was 20.8% at 5 years and 33.8% at 10 years. The rate was similar between years 1-5 and 6-10.

The cumulative all-cause mortality rate was 10.4% at 5 years and 24.2% at 10 years. The rate was 2.0%/year during years 1-5 and accelerated significantly to 3.1%/year in years 6-10. However, this increase appears to be largely due to the background impact of advancing age rather than to any effect of having a first-generation DES. The 5- and 10-year all-cause mortality rates in the age- and sex-matched general Swiss population are similar to those seen in SIRTAX VERY LATE, at 9.6% and 22.1%, respectively, the cardiologist observed.

The cumulative incidence of MI in the study population was 7% at 5 years and 9.7% at 10 years. Between years 1-5 the rate was 0.9%/year, dropping to 0.6%/year during years 6-10.

One of the useful potential purposes for the new SIRTAX VERY LATE follow-up data beyond 5 years is that the results could serve as a benchmark in evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of the much newer drug-eluting fully bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, since the potential benefits of these new devices may not appear until relatively late, after the devices themselves have disappeared. SIRTAX VERY LATE sets the bar for stent-related adverse events 5 years or more after device implantation at an annual risk of less than 0.3%/year for stent thrombosis and less than 1%/year for ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization.

Session co-chair Hector Bueno, MD, drew attention to the fact that no significant differences in clinical outcomes were seen at either 5 or 10 years between the sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stent recipients. That’s noteworthy because more than a decade ago when the primary endpoint of SIRTAX was reported, much was made of the finding that the 9-month rate of major adverse cardiac events was significantly lower in the sirolimus-eluting stent group (N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 18;353[7]:653-62). Over time, any outcome differences between the two devices were erased, observed Dr. Bueno of Complutense University of Madrid.

The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was funded by grants from Bern University Hospital. Dr. Räber reported having no relevant financial interests.

Simultaneously with his presentation in Rome at ESC 2016, the study results were published online (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw343).

ROME – There’s good news for the millions of patients living with a first-generation metallic drug-eluting stent for coronary revascularization implanted in years past: The devices perform reassuringly well a full decade after implantation, Lorenz Räber, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

That’s the key message of the SIRTAX VERY LATE study, the only randomized trial of first-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) that didn’t turn out the lights at a maximum of 5 years of follow-up. In fact, at the 10-year mark, SIRTAX VERY LATE shows that regardless of whether the first-generation DES was paclitaxel- or sirolimus-eluting, the risk of major adverse cardiac events due to device failure was substantially lower in the second half-decade than in the first 5 years after deployment, according to Dr. Räber of Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

More specifically, the cumulative risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization was 14.6% at 5 years and 17.7% at 10 years, while the 5- and 10-year cumulative risks of definite stent thrombosis were 4.5% and 5.6%, respectively.

The annual risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization dropped by 64%, from 1.8%/year during years 1-5 to 0.7% during years 6-10. Similarly, the annual risk of definite stent thrombosis fell from 0.67%/year to 0.23%/year after year 5, a 69% relative risk reduction. And importantly, these attenuations in risk occurred independent of age.

“The lower risk of late clinical events suggests stabilization of delayed arterial healing over time after first-generation DES implantation, with reduced chronic inflammation and neoatherosclerosis,” he said.

This is reassuring in light of the stormy history of the first-generation DES. Three years after the devices came on the U.S. market, the so-called ESC firestorm erupted. At the 2006 ESC congress, investigators presented meta-analyses suggesting the devices carried a possible late increased thrombotic risk beyond the then-recommended 3-6 months of prescribed dual-antiplatelet therapy. The use of these devices declined sharply in response, even though a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel charged with looking at the totality of evidence concluded that concerns about thrombosis didn’t outweigh the benefits of the first-generation DES over bare-metal stents.

The reductions in very late stent thrombosis and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization beyond 5 years seen in the SIRTAX VERY LATE trial occurred despite the fact that only 15% of patients were on dual-antiplatelet therapy throughout the first 5 years and 11% were on dual-antiplatelet therapy afterwards, Dr. Räber noted.

“Our findings may have implications for secondary prevention after PCI with a first-generation DES, including the need for long-term antiplatelet therapy,” the cardiologist added.

The previously reported 5-year results of SIRTAX (the Sirolimus-Eluting Versus Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization trial) showed a steady increase over time in late lumen loss and an ongoing risk of very late stent thrombosis (Circulation. 2011 Jun 21;123(24):2819-28). Much the same was seen at the 5-year mark in the other major trials of first-generation DES, including RAVEL, SIRIUS, and TAXUS.

However, all those studies ended at 5 years, leaving unanswered the key question of what happens later. Cardiologists have wondered if the first-generation DES they put in their patients years ago were associated with a continued steady climb in the risk of device-related adverse events, or if the risk plateaued or even dropped off. The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was conducted in order to provide answers.

SIRTAX included 1,012 Swiss patients randomized to coronary revascularization using a first-generation sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stent in 2003-2004. Roughly half had stable coronary artery disease and half presented with acute coronary syndromes. The 10-year follow-up conducted in the SIRTAX VERY LATE study captured 895 (88%) of the original 1,012 subjects.

The cumulative incidence of major cardiac adverse events – a composite of cardiac death, MI, and ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization – was 20.8% at 5 years and 33.8% at 10 years. The rate was similar between years 1-5 and 6-10.

The cumulative all-cause mortality rate was 10.4% at 5 years and 24.2% at 10 years. The rate was 2.0%/year during years 1-5 and accelerated significantly to 3.1%/year in years 6-10. However, this increase appears to be largely due to the background impact of advancing age rather than to any effect of having a first-generation DES. The 5- and 10-year all-cause mortality rates in the age- and sex-matched general Swiss population are similar to those seen in SIRTAX VERY LATE, at 9.6% and 22.1%, respectively, the cardiologist observed.

The cumulative incidence of MI in the study population was 7% at 5 years and 9.7% at 10 years. Between years 1-5 the rate was 0.9%/year, dropping to 0.6%/year during years 6-10.

One of the useful potential purposes for the new SIRTAX VERY LATE follow-up data beyond 5 years is that the results could serve as a benchmark in evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of the much newer drug-eluting fully bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, since the potential benefits of these new devices may not appear until relatively late, after the devices themselves have disappeared. SIRTAX VERY LATE sets the bar for stent-related adverse events 5 years or more after device implantation at an annual risk of less than 0.3%/year for stent thrombosis and less than 1%/year for ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization.

Session co-chair Hector Bueno, MD, drew attention to the fact that no significant differences in clinical outcomes were seen at either 5 or 10 years between the sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stent recipients. That’s noteworthy because more than a decade ago when the primary endpoint of SIRTAX was reported, much was made of the finding that the 9-month rate of major adverse cardiac events was significantly lower in the sirolimus-eluting stent group (N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 18;353[7]:653-62). Over time, any outcome differences between the two devices were erased, observed Dr. Bueno of Complutense University of Madrid.

The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was funded by grants from Bern University Hospital. Dr. Räber reported having no relevant financial interests.

Simultaneously with his presentation in Rome at ESC 2016, the study results were published online (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw343).

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: The annual risks of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization and stent thrombosis significantly decreased starting 5 years after implantation of a first-generation sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stent.

Major finding: The annual risk of ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization was 1.8%/year between 1 and 5 years after implantation of a first-generation drug-eluting stent, but only 0.7%/year during years 6-10.

Data source: This was a unique extended 10-year follow-up of 88% of the original 1,012 participants in a randomized, assessor-blinded Swiss trial of coronary revascularization using a first-generation sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stent.

Disclosures: The SIRTAX VERY LATE study was funded by grants from Bern University Hospital. The presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

ANTARCTIC results chill enthusiasm for platelet monitoring

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Researchers have just about given up on the notion that monitoring platelet function in order to individualize antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing PCI provides any clinical benefit.

Major finding: Individualized antiplatelet therapy based upon serial measurements of platelet function did not result in improved outcomes in elderly patients undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndrome (27.6% in the platelet monitoring group and 27.8% in conventionally managed patients).

Data source: ANTARCTIC was an open-label, blinded-endpoint randomized trial of tailored versus standard antiplatelet therapy in 877 elderly patients undergoing PCI for ACS.

Disclosures: ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

Ticagrelor slashes first stroke risk after MI

ROME – Adding ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily in patients on low-dose aspirin due to a prior MI reduced their risk of a first stroke by 25% in a secondary analysis of the landmark PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in more than 21,000 stable patients on low-dose aspirin with a history of an acute MI 1-3 years earlier. The significant reduction in secondary cardiovascular events seen in this study during a median 33 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 7;372[19]:1791-800) led to approval of ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 60 mg twice daily for long-term secondary prevention.

But while PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a secondary prevention study in terms of cardiovascular events, it was actually a primary prevention study in terms of stroke, since patients with a history of stroke weren’t eligible for enrollment. And in this trial, recipients of ticagrelor at 50 mg twice daily experienced a 25% reduction in the risk of stroke relative to placebo, from 1.94% at 3 years to 1.47%. This benefit was driven by fewer ischemic strokes, with no increase in hemorrhagic strokes seen with ticagrelor. And therein lies a clinical take home point: “When evaluating the overall benefits and risks of long-term ticagrelor in patients with prior MI, stroke reduction should also be considered,” according to Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

All strokes were adjudicated and subclassified by a blinded central committee. A total of 213 stroke events occurred during follow-up: 81% ischemic, 7% hemorrhagic, 4% ischemic with hemorrhagic conversion, and 8% unknown; 18% of the strokes were fatal. Another 15% resulted in moderate or severe disability at 30 days. All PEGASUS-TIMI 54 participants were on aspirin and more than 90% were on statin therapy.

The strokes that occurred in patients on ticagrelor were generally less severe than in controls. The risk of having a modified Rankin score of 3-6, which encompasses outcomes ranging from moderate disability to death, was reduced by 43% in stroke patients on ticagrelor relative to those on placebo, the cardiologist continued.

To ensure that the stroke benefit with ticagrelor seen in PEGASUS-TIMI 54 wasn’t a fluke, Dr. Bonaca and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of four placebo-controlled randomized trials of more intensive versus less intensive antiplatelet therapy in nearly 45,000 participants with coronary disease in the CHARISMA, DAPT, PEGASUS-TIMI 54, and TRA 2*P-TIMI 50 trials. A total of 532 strokes occurred in this enlarged analysis. More intensive antiplatelet therapy – typically adding a second drug to low-dose aspirin – resulted in a 34% reduction in ischemic stroke, compared with low-dose aspirin and placebo.

Excluding from the meta-analysis the large subgroup of patients in TRA 2*P-TIMI 50 who were on triple-drug antiplatelet therapy, investigators were left with 32,348 participants in the four trials who were randomized to dual-antiplatelet therapy or monotherapy with aspirin. In this population, there was no increase in the risk of hemorrhagic stroke associated with more intensive antiplatelet therapy, according to Dr. Bonaca.

Session co-chair Keith A.A. Fox, MD, of the University of Edinburgh, noted that various studies have shown monotherapy with aspirin or another antiplatelet agent reduces stroke risk by about 15%, and now PEGASUS-TIMI 54 shows that ticagrelor plus aspirin decreases stroke risk by 25%. He posed a direct question: “How much is too much?”

“More and more antiplatelet therapy begets more bleeding, so I think that more than two agents may be approaching too much, although it really depends on what agents you’re using and in what dosages,” Dr. Bonaca replied.

He reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Bayer.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bonaca’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the new report from PEGASUS-TIMI 54 including the four-trial meta-analysis was published online (Circulation. 2016 Aug 30. doi: circulationaha.116.024637).

ROME – Adding ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily in patients on low-dose aspirin due to a prior MI reduced their risk of a first stroke by 25% in a secondary analysis of the landmark PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in more than 21,000 stable patients on low-dose aspirin with a history of an acute MI 1-3 years earlier. The significant reduction in secondary cardiovascular events seen in this study during a median 33 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 7;372[19]:1791-800) led to approval of ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 60 mg twice daily for long-term secondary prevention.

But while PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a secondary prevention study in terms of cardiovascular events, it was actually a primary prevention study in terms of stroke, since patients with a history of stroke weren’t eligible for enrollment. And in this trial, recipients of ticagrelor at 50 mg twice daily experienced a 25% reduction in the risk of stroke relative to placebo, from 1.94% at 3 years to 1.47%. This benefit was driven by fewer ischemic strokes, with no increase in hemorrhagic strokes seen with ticagrelor. And therein lies a clinical take home point: “When evaluating the overall benefits and risks of long-term ticagrelor in patients with prior MI, stroke reduction should also be considered,” according to Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

All strokes were adjudicated and subclassified by a blinded central committee. A total of 213 stroke events occurred during follow-up: 81% ischemic, 7% hemorrhagic, 4% ischemic with hemorrhagic conversion, and 8% unknown; 18% of the strokes were fatal. Another 15% resulted in moderate or severe disability at 30 days. All PEGASUS-TIMI 54 participants were on aspirin and more than 90% were on statin therapy.

The strokes that occurred in patients on ticagrelor were generally less severe than in controls. The risk of having a modified Rankin score of 3-6, which encompasses outcomes ranging from moderate disability to death, was reduced by 43% in stroke patients on ticagrelor relative to those on placebo, the cardiologist continued.

To ensure that the stroke benefit with ticagrelor seen in PEGASUS-TIMI 54 wasn’t a fluke, Dr. Bonaca and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of four placebo-controlled randomized trials of more intensive versus less intensive antiplatelet therapy in nearly 45,000 participants with coronary disease in the CHARISMA, DAPT, PEGASUS-TIMI 54, and TRA 2*P-TIMI 50 trials. A total of 532 strokes occurred in this enlarged analysis. More intensive antiplatelet therapy – typically adding a second drug to low-dose aspirin – resulted in a 34% reduction in ischemic stroke, compared with low-dose aspirin and placebo.

Excluding from the meta-analysis the large subgroup of patients in TRA 2*P-TIMI 50 who were on triple-drug antiplatelet therapy, investigators were left with 32,348 participants in the four trials who were randomized to dual-antiplatelet therapy or monotherapy with aspirin. In this population, there was no increase in the risk of hemorrhagic stroke associated with more intensive antiplatelet therapy, according to Dr. Bonaca.

Session co-chair Keith A.A. Fox, MD, of the University of Edinburgh, noted that various studies have shown monotherapy with aspirin or another antiplatelet agent reduces stroke risk by about 15%, and now PEGASUS-TIMI 54 shows that ticagrelor plus aspirin decreases stroke risk by 25%. He posed a direct question: “How much is too much?”

“More and more antiplatelet therapy begets more bleeding, so I think that more than two agents may be approaching too much, although it really depends on what agents you’re using and in what dosages,” Dr. Bonaca replied.

He reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Bayer.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bonaca’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the new report from PEGASUS-TIMI 54 including the four-trial meta-analysis was published online (Circulation. 2016 Aug 30. doi: circulationaha.116.024637).

ROME – Adding ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily in patients on low-dose aspirin due to a prior MI reduced their risk of a first stroke by 25% in a secondary analysis of the landmark PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in more than 21,000 stable patients on low-dose aspirin with a history of an acute MI 1-3 years earlier. The significant reduction in secondary cardiovascular events seen in this study during a median 33 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 7;372[19]:1791-800) led to approval of ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 60 mg twice daily for long-term secondary prevention.

But while PEGASUS-TIMI 54 was a secondary prevention study in terms of cardiovascular events, it was actually a primary prevention study in terms of stroke, since patients with a history of stroke weren’t eligible for enrollment. And in this trial, recipients of ticagrelor at 50 mg twice daily experienced a 25% reduction in the risk of stroke relative to placebo, from 1.94% at 3 years to 1.47%. This benefit was driven by fewer ischemic strokes, with no increase in hemorrhagic strokes seen with ticagrelor. And therein lies a clinical take home point: “When evaluating the overall benefits and risks of long-term ticagrelor in patients with prior MI, stroke reduction should also be considered,” according to Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

All strokes were adjudicated and subclassified by a blinded central committee. A total of 213 stroke events occurred during follow-up: 81% ischemic, 7% hemorrhagic, 4% ischemic with hemorrhagic conversion, and 8% unknown; 18% of the strokes were fatal. Another 15% resulted in moderate or severe disability at 30 days. All PEGASUS-TIMI 54 participants were on aspirin and more than 90% were on statin therapy.

The strokes that occurred in patients on ticagrelor were generally less severe than in controls. The risk of having a modified Rankin score of 3-6, which encompasses outcomes ranging from moderate disability to death, was reduced by 43% in stroke patients on ticagrelor relative to those on placebo, the cardiologist continued.

To ensure that the stroke benefit with ticagrelor seen in PEGASUS-TIMI 54 wasn’t a fluke, Dr. Bonaca and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of four placebo-controlled randomized trials of more intensive versus less intensive antiplatelet therapy in nearly 45,000 participants with coronary disease in the CHARISMA, DAPT, PEGASUS-TIMI 54, and TRA 2*P-TIMI 50 trials. A total of 532 strokes occurred in this enlarged analysis. More intensive antiplatelet therapy – typically adding a second drug to low-dose aspirin – resulted in a 34% reduction in ischemic stroke, compared with low-dose aspirin and placebo.