User login

Delayed resolution of concussion symptoms linked to somatization

BALTIMORE – Children whose parents rated them higher on a psychological assessment of somatization were more likely to show persistent postconcussive symptoms, according to a recent study.

Joe Grubenhoff, MD, and his colleagues at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported that 34.2% of children with delayed symptom recovery (DSR) after concussion had abnormal scores on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the Personality Inventory for Children–Version 2 (PIC-2), compared with 12.8% of children with early symptom recovery (ESR, P = .01).

This finding from a prospective longitudinal study of 179 children with concussion extends previous work showing similar findings in adults with concussion. “Children with a pre-injury tendency to somaticize were more likely to report delayed symptom resolution,” said Dr. Grubenhoff, , professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Grubenhoff noted that the study is important because out of the 630,000 annual ED visits for concussion in children, up to 30% may have postconcussive symptoms 3 months after the event. Concussion management guidelines are symptom driven. In practical terms, this means that return to sports is prohibited until symptoms are gone, and academic activities may be modified while children are symptomatic.

This management strategy assumes that a heavier symptom load means a more serious injury, and that symptoms that persist indicate lack of complete recovery from concussion, Dr. Grubenhoff said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“In an ED cohort, initial symptom load was not associated with delayed symptom resolution,” he said, citing previous research. It’s known that persistent postconcussive symptoms in adults are associated with certain pre-injury psychological traits, including somatization, but whether this holds true in a pediatric population was not known, he said.

To characterize which psychological factors might be associated with postconcussion DSR in children, Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues designed a prospective longitudinal cohort study of children presenting to a regional pediatric trauma ED with concussion. To be included, the patients, aged 8-18 years, had to present to the ED within 6 hours of their injury. Children with open head injury or multisystem trauma, those who were intoxicated or who had received narcotics, and those with underlying CNS abnormalities were excluded.

Symptoms were assessed with a 12-symptom graded symptom inventory, with the addition of two additional symptoms, sadness and irritability. Symptoms were graded on a 0- to 2-point scale. At 30 days post injury, patients reported symptom presence and severity; patients were assessed as having DSR if they had at least three symptoms that were worse than the patient’s pre-injury baseline.

Independent psychological variables were assessed by parental assessment of the child’s pre-injury state via the PIC-2. This tool’s subscales measure cognitive impairment, psychological discomfort, and somatic concern. Also, the study administered two postinjury assessments to children: the “state” portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI), and the Children’s Illness Perception Questionnaire (CIPQ). This last measure allowed Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues to explore the children’s own ideas about their concussion.

The study enrolled 234 children, but 55 of them (24%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 179 remaining children, 141 (79%) had ESR, while the remaining 38 (21%) had DSR. Demographics, mechanism of injury, and injury characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. The study included children with intracranial hemorrhages (n = 5, all in the ESR group), and whose Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was less than 15 (n = 12, 11 in the ESR group). Return to GCS of 15 within 24 hours was not documented, but the mean GCS for study patients was 15.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, children who scored higher on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the PIC-2 were more likely to experience DSR (odds ratio [OR] 1.35, P less than .01). There was no significant difference between the groups in the other psychological testing.

Study limitations include the fact that about a quarter of patients were lost to follow-up, although these patients did not differ in their scoring on psychological testing from those who remained. Also, the possibility of misclassification exists, since symptoms may have resolved at a time point just before or after the 30-day follow-up marker. But Dr. Grubenhoff said that the proportion of children with DSR was similar to that seen in other cohorts of children presenting to the ED with concussion.

“Postconcussive symptoms lasting at least 1 month may warrant referral to a neuropsychologist,” said Dr. Grubenhoff.

He reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Children whose parents rated them higher on a psychological assessment of somatization were more likely to show persistent postconcussive symptoms, according to a recent study.

Joe Grubenhoff, MD, and his colleagues at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported that 34.2% of children with delayed symptom recovery (DSR) after concussion had abnormal scores on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the Personality Inventory for Children–Version 2 (PIC-2), compared with 12.8% of children with early symptom recovery (ESR, P = .01).

This finding from a prospective longitudinal study of 179 children with concussion extends previous work showing similar findings in adults with concussion. “Children with a pre-injury tendency to somaticize were more likely to report delayed symptom resolution,” said Dr. Grubenhoff, , professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Grubenhoff noted that the study is important because out of the 630,000 annual ED visits for concussion in children, up to 30% may have postconcussive symptoms 3 months after the event. Concussion management guidelines are symptom driven. In practical terms, this means that return to sports is prohibited until symptoms are gone, and academic activities may be modified while children are symptomatic.

This management strategy assumes that a heavier symptom load means a more serious injury, and that symptoms that persist indicate lack of complete recovery from concussion, Dr. Grubenhoff said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“In an ED cohort, initial symptom load was not associated with delayed symptom resolution,” he said, citing previous research. It’s known that persistent postconcussive symptoms in adults are associated with certain pre-injury psychological traits, including somatization, but whether this holds true in a pediatric population was not known, he said.

To characterize which psychological factors might be associated with postconcussion DSR in children, Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues designed a prospective longitudinal cohort study of children presenting to a regional pediatric trauma ED with concussion. To be included, the patients, aged 8-18 years, had to present to the ED within 6 hours of their injury. Children with open head injury or multisystem trauma, those who were intoxicated or who had received narcotics, and those with underlying CNS abnormalities were excluded.

Symptoms were assessed with a 12-symptom graded symptom inventory, with the addition of two additional symptoms, sadness and irritability. Symptoms were graded on a 0- to 2-point scale. At 30 days post injury, patients reported symptom presence and severity; patients were assessed as having DSR if they had at least three symptoms that were worse than the patient’s pre-injury baseline.

Independent psychological variables were assessed by parental assessment of the child’s pre-injury state via the PIC-2. This tool’s subscales measure cognitive impairment, psychological discomfort, and somatic concern. Also, the study administered two postinjury assessments to children: the “state” portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI), and the Children’s Illness Perception Questionnaire (CIPQ). This last measure allowed Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues to explore the children’s own ideas about their concussion.

The study enrolled 234 children, but 55 of them (24%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 179 remaining children, 141 (79%) had ESR, while the remaining 38 (21%) had DSR. Demographics, mechanism of injury, and injury characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. The study included children with intracranial hemorrhages (n = 5, all in the ESR group), and whose Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was less than 15 (n = 12, 11 in the ESR group). Return to GCS of 15 within 24 hours was not documented, but the mean GCS for study patients was 15.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, children who scored higher on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the PIC-2 were more likely to experience DSR (odds ratio [OR] 1.35, P less than .01). There was no significant difference between the groups in the other psychological testing.

Study limitations include the fact that about a quarter of patients were lost to follow-up, although these patients did not differ in their scoring on psychological testing from those who remained. Also, the possibility of misclassification exists, since symptoms may have resolved at a time point just before or after the 30-day follow-up marker. But Dr. Grubenhoff said that the proportion of children with DSR was similar to that seen in other cohorts of children presenting to the ED with concussion.

“Postconcussive symptoms lasting at least 1 month may warrant referral to a neuropsychologist,” said Dr. Grubenhoff.

He reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Children whose parents rated them higher on a psychological assessment of somatization were more likely to show persistent postconcussive symptoms, according to a recent study.

Joe Grubenhoff, MD, and his colleagues at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported that 34.2% of children with delayed symptom recovery (DSR) after concussion had abnormal scores on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the Personality Inventory for Children–Version 2 (PIC-2), compared with 12.8% of children with early symptom recovery (ESR, P = .01).

This finding from a prospective longitudinal study of 179 children with concussion extends previous work showing similar findings in adults with concussion. “Children with a pre-injury tendency to somaticize were more likely to report delayed symptom resolution,” said Dr. Grubenhoff, , professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Grubenhoff noted that the study is important because out of the 630,000 annual ED visits for concussion in children, up to 30% may have postconcussive symptoms 3 months after the event. Concussion management guidelines are symptom driven. In practical terms, this means that return to sports is prohibited until symptoms are gone, and academic activities may be modified while children are symptomatic.

This management strategy assumes that a heavier symptom load means a more serious injury, and that symptoms that persist indicate lack of complete recovery from concussion, Dr. Grubenhoff said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“In an ED cohort, initial symptom load was not associated with delayed symptom resolution,” he said, citing previous research. It’s known that persistent postconcussive symptoms in adults are associated with certain pre-injury psychological traits, including somatization, but whether this holds true in a pediatric population was not known, he said.

To characterize which psychological factors might be associated with postconcussion DSR in children, Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues designed a prospective longitudinal cohort study of children presenting to a regional pediatric trauma ED with concussion. To be included, the patients, aged 8-18 years, had to present to the ED within 6 hours of their injury. Children with open head injury or multisystem trauma, those who were intoxicated or who had received narcotics, and those with underlying CNS abnormalities were excluded.

Symptoms were assessed with a 12-symptom graded symptom inventory, with the addition of two additional symptoms, sadness and irritability. Symptoms were graded on a 0- to 2-point scale. At 30 days post injury, patients reported symptom presence and severity; patients were assessed as having DSR if they had at least three symptoms that were worse than the patient’s pre-injury baseline.

Independent psychological variables were assessed by parental assessment of the child’s pre-injury state via the PIC-2. This tool’s subscales measure cognitive impairment, psychological discomfort, and somatic concern. Also, the study administered two postinjury assessments to children: the “state” portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI), and the Children’s Illness Perception Questionnaire (CIPQ). This last measure allowed Dr. Grubenhoff and his colleagues to explore the children’s own ideas about their concussion.

The study enrolled 234 children, but 55 of them (24%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 179 remaining children, 141 (79%) had ESR, while the remaining 38 (21%) had DSR. Demographics, mechanism of injury, and injury characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. The study included children with intracranial hemorrhages (n = 5, all in the ESR group), and whose Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was less than 15 (n = 12, 11 in the ESR group). Return to GCS of 15 within 24 hours was not documented, but the mean GCS for study patients was 15.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, children who scored higher on the Somatic Concerns subscale of the PIC-2 were more likely to experience DSR (odds ratio [OR] 1.35, P less than .01). There was no significant difference between the groups in the other psychological testing.

Study limitations include the fact that about a quarter of patients were lost to follow-up, although these patients did not differ in their scoring on psychological testing from those who remained. Also, the possibility of misclassification exists, since symptoms may have resolved at a time point just before or after the 30-day follow-up marker. But Dr. Grubenhoff said that the proportion of children with DSR was similar to that seen in other cohorts of children presenting to the ED with concussion.

“Postconcussive symptoms lasting at least 1 month may warrant referral to a neuropsychologist,” said Dr. Grubenhoff.

He reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Children with higher scores on a somatization scale were more likely to have delayed symptom recovery after concussion (odds ratio [OR] 1.35, P less than .01).

Major finding: Abnormal somatization scores were seen in 34.2% of children with delayed symptom recovery, versus 12.8% of children with early symptom recovery (P = .01).

Data source: Prospective single-center longitudinal study of 179 children presenting to the emergency department with concussion.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no disclosures.

Persistent ADHD in early years linked to worse academic, emotional outcomes

BALTIMORE – Persistent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) through young childhood is associated with both poorer academic outcomes and an increased risk of other mental health problems, according to a longitudinal study of younger children with ADHD.

An Australian study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies found that 67% of children who had ADHD at age 7 years still met the diagnostic criteria 3 years later, when they were 10 years old. Boys were more likely than girls to have retained the diagnosis (74% vs. 50%; odds ratio, 3.4; P = .01).

On average, children with ADHD had lower scores on math and reading tests than their matched peers without ADHD, even after adjustment for socioeconomic variables and comorbidities (mean difference, –7.6 for math and –8.7 for reading, P less than .001 for both).

When Emma Sciberras, Ph.D., and her colleagues examined the longitudinal data, they found that children who had a persistent ADHD diagnosis were more likely to have an externalizing disorder, such as a conduct disorder (57% vs. 33%; OR, 2.8; P = .008). They also were more likely to have a mood disorder (8% vs. 0%; P = .04).

No sex differences were seen, aside from the increased likelihood of a persistent diagnosis.

“Childhood ADHD confers risk for future mental health difficulties,” said Dr. Sciberras, a psychologist at Deakin University, Melbourne. Dr. Sciberras presented preliminary findings from the Children’s Attention Project, a 3-year study of 179 young children with ADHD and 212 children without the diagnosis.

The goal of the Children’s Attention Project, a community-based longitudinal study, was to document the natural history of ADHD. Aspects of the study included assessing the impact of ADHD on the mental health of both children and parents, as well as examining social, academic, and family functioning, and overall quality of life. The study also seeks to tease out both risks and protective factors that can tip outcomes toward the better – or worse – end of the spectrum, said Dr. Sciberras.

The Children’s Attention Project enrolled first graders from 43 primary schools in Melbourne, to compare 3-year outcomes of a sample of children with ADHD with a control group of children who did not have ADHD. In addition to assessing diagnostic stability (the persistence of an ADHD diagnosis), Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators also looked at functional outcomes. Sex differences in outcomes, as well as the effect of ADHD persistence, also were assessed for the community-based sample of children.

Children were enrolled after families and teachers of the first graders completed the Conners 3 ADHD Index. Families of children with positive screens and matched controls were offered enrollment in the study, with intake involving confirmation of the ADHD diagnosis, as well as detailed academic and behavioral assessments and a family survey. Children in the study were assessed at baseline, and then again at 18 and 36 months after enrollment. Longitudinal data were available for 72% of those initially enrolled.

Children in the study averaged 7.3 years old. Of the ADHD group, 124/179 (69%) were male, as were 135/212 (64%) of the control group. For children in the ADHD group, 31 (17%) had previously been diagnosed with ADHD, and 23 children (13%) were on ADHD medication at enrollment; none of the control group had a prior ADHD diagnosis or was taking medication. For 63 (38%) of the children in the ADHD group, their primary caregiver had not completed high school, compared with 39 (19%) in the control group.

“This is really more of a community-based approach to researching ADHD,” Dr. Sciberras said in an interview. Previous longitudinal studies, she said, had a near-exclusive focus on clinical samples, which can “overrepresent boys and children with more severe symptoms,” she said. Age ranges were broad, and follow-up was often infrequent. Most importantly, positive factors that lead to good outcomes for children with ADHD had been understudied, she said, and she and her colleagues are continuing to look for factors, such as resilience, that contribute to better social and emotional functioning.

It’s important to study children with ADHD in a real world manner because “childhood ADHD is associated with poorer academic outcomes, and the risk is evident from the second year of school,” said Dr. Sciberras. “We need to identify which factors lead to improved outcomes over time. The ultimate aim is to map functional impairment and key predictors from age 7 to later adolescence and adulthood.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council and by the Collier Foundation. Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Persistent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) through young childhood is associated with both poorer academic outcomes and an increased risk of other mental health problems, according to a longitudinal study of younger children with ADHD.

An Australian study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies found that 67% of children who had ADHD at age 7 years still met the diagnostic criteria 3 years later, when they were 10 years old. Boys were more likely than girls to have retained the diagnosis (74% vs. 50%; odds ratio, 3.4; P = .01).

On average, children with ADHD had lower scores on math and reading tests than their matched peers without ADHD, even after adjustment for socioeconomic variables and comorbidities (mean difference, –7.6 for math and –8.7 for reading, P less than .001 for both).

When Emma Sciberras, Ph.D., and her colleagues examined the longitudinal data, they found that children who had a persistent ADHD diagnosis were more likely to have an externalizing disorder, such as a conduct disorder (57% vs. 33%; OR, 2.8; P = .008). They also were more likely to have a mood disorder (8% vs. 0%; P = .04).

No sex differences were seen, aside from the increased likelihood of a persistent diagnosis.

“Childhood ADHD confers risk for future mental health difficulties,” said Dr. Sciberras, a psychologist at Deakin University, Melbourne. Dr. Sciberras presented preliminary findings from the Children’s Attention Project, a 3-year study of 179 young children with ADHD and 212 children without the diagnosis.

The goal of the Children’s Attention Project, a community-based longitudinal study, was to document the natural history of ADHD. Aspects of the study included assessing the impact of ADHD on the mental health of both children and parents, as well as examining social, academic, and family functioning, and overall quality of life. The study also seeks to tease out both risks and protective factors that can tip outcomes toward the better – or worse – end of the spectrum, said Dr. Sciberras.

The Children’s Attention Project enrolled first graders from 43 primary schools in Melbourne, to compare 3-year outcomes of a sample of children with ADHD with a control group of children who did not have ADHD. In addition to assessing diagnostic stability (the persistence of an ADHD diagnosis), Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators also looked at functional outcomes. Sex differences in outcomes, as well as the effect of ADHD persistence, also were assessed for the community-based sample of children.

Children were enrolled after families and teachers of the first graders completed the Conners 3 ADHD Index. Families of children with positive screens and matched controls were offered enrollment in the study, with intake involving confirmation of the ADHD diagnosis, as well as detailed academic and behavioral assessments and a family survey. Children in the study were assessed at baseline, and then again at 18 and 36 months after enrollment. Longitudinal data were available for 72% of those initially enrolled.

Children in the study averaged 7.3 years old. Of the ADHD group, 124/179 (69%) were male, as were 135/212 (64%) of the control group. For children in the ADHD group, 31 (17%) had previously been diagnosed with ADHD, and 23 children (13%) were on ADHD medication at enrollment; none of the control group had a prior ADHD diagnosis or was taking medication. For 63 (38%) of the children in the ADHD group, their primary caregiver had not completed high school, compared with 39 (19%) in the control group.

“This is really more of a community-based approach to researching ADHD,” Dr. Sciberras said in an interview. Previous longitudinal studies, she said, had a near-exclusive focus on clinical samples, which can “overrepresent boys and children with more severe symptoms,” she said. Age ranges were broad, and follow-up was often infrequent. Most importantly, positive factors that lead to good outcomes for children with ADHD had been understudied, she said, and she and her colleagues are continuing to look for factors, such as resilience, that contribute to better social and emotional functioning.

It’s important to study children with ADHD in a real world manner because “childhood ADHD is associated with poorer academic outcomes, and the risk is evident from the second year of school,” said Dr. Sciberras. “We need to identify which factors lead to improved outcomes over time. The ultimate aim is to map functional impairment and key predictors from age 7 to later adolescence and adulthood.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council and by the Collier Foundation. Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Persistent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) through young childhood is associated with both poorer academic outcomes and an increased risk of other mental health problems, according to a longitudinal study of younger children with ADHD.

An Australian study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies found that 67% of children who had ADHD at age 7 years still met the diagnostic criteria 3 years later, when they were 10 years old. Boys were more likely than girls to have retained the diagnosis (74% vs. 50%; odds ratio, 3.4; P = .01).

On average, children with ADHD had lower scores on math and reading tests than their matched peers without ADHD, even after adjustment for socioeconomic variables and comorbidities (mean difference, –7.6 for math and –8.7 for reading, P less than .001 for both).

When Emma Sciberras, Ph.D., and her colleagues examined the longitudinal data, they found that children who had a persistent ADHD diagnosis were more likely to have an externalizing disorder, such as a conduct disorder (57% vs. 33%; OR, 2.8; P = .008). They also were more likely to have a mood disorder (8% vs. 0%; P = .04).

No sex differences were seen, aside from the increased likelihood of a persistent diagnosis.

“Childhood ADHD confers risk for future mental health difficulties,” said Dr. Sciberras, a psychologist at Deakin University, Melbourne. Dr. Sciberras presented preliminary findings from the Children’s Attention Project, a 3-year study of 179 young children with ADHD and 212 children without the diagnosis.

The goal of the Children’s Attention Project, a community-based longitudinal study, was to document the natural history of ADHD. Aspects of the study included assessing the impact of ADHD on the mental health of both children and parents, as well as examining social, academic, and family functioning, and overall quality of life. The study also seeks to tease out both risks and protective factors that can tip outcomes toward the better – or worse – end of the spectrum, said Dr. Sciberras.

The Children’s Attention Project enrolled first graders from 43 primary schools in Melbourne, to compare 3-year outcomes of a sample of children with ADHD with a control group of children who did not have ADHD. In addition to assessing diagnostic stability (the persistence of an ADHD diagnosis), Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators also looked at functional outcomes. Sex differences in outcomes, as well as the effect of ADHD persistence, also were assessed for the community-based sample of children.

Children were enrolled after families and teachers of the first graders completed the Conners 3 ADHD Index. Families of children with positive screens and matched controls were offered enrollment in the study, with intake involving confirmation of the ADHD diagnosis, as well as detailed academic and behavioral assessments and a family survey. Children in the study were assessed at baseline, and then again at 18 and 36 months after enrollment. Longitudinal data were available for 72% of those initially enrolled.

Children in the study averaged 7.3 years old. Of the ADHD group, 124/179 (69%) were male, as were 135/212 (64%) of the control group. For children in the ADHD group, 31 (17%) had previously been diagnosed with ADHD, and 23 children (13%) were on ADHD medication at enrollment; none of the control group had a prior ADHD diagnosis or was taking medication. For 63 (38%) of the children in the ADHD group, their primary caregiver had not completed high school, compared with 39 (19%) in the control group.

“This is really more of a community-based approach to researching ADHD,” Dr. Sciberras said in an interview. Previous longitudinal studies, she said, had a near-exclusive focus on clinical samples, which can “overrepresent boys and children with more severe symptoms,” she said. Age ranges were broad, and follow-up was often infrequent. Most importantly, positive factors that lead to good outcomes for children with ADHD had been understudied, she said, and she and her colleagues are continuing to look for factors, such as resilience, that contribute to better social and emotional functioning.

It’s important to study children with ADHD in a real world manner because “childhood ADHD is associated with poorer academic outcomes, and the risk is evident from the second year of school,” said Dr. Sciberras. “We need to identify which factors lead to improved outcomes over time. The ultimate aim is to map functional impairment and key predictors from age 7 to later adolescence and adulthood.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council and by the Collier Foundation. Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Persistent ADHD in early childhood was associated with worse academic and emotional outcomes at age 10 years.

Major finding: Young children with persistent ADHD were almost three times more likely to have an externalizing mental health disorder than peers without ADHD (57% vs. 33%; OR, 2.8; P = .008).

Data source: A 3-year longitudinal study of 179 first graders with ADHD and 212 children without ADHD.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council and by the Collier Foundation. Dr. Sciberras and her collaborators had no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Post legalization, what effect is recreational marijuana use having on children?

BALTIMORE – Experts from Colorado and Washington – two states which have legalized recreational use of the drug – came together at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies to discuss the challenges of treating and preventing short-term and long-term illness brought on by marijuana use.

“In Colorado, a lot of [mothers] use [marijuana] for depression, anxiety, as well as for nausea, and they’re not disclosing that” to their primary care doctors, explained Dr. Maya Bunik of the University of Colorado in Aurora. “Then they’re sort of surprised at birth when we tell them that we don’t know what [marijuana] does in terms of affecting [their] baby.”

In a series of interviews, presenters at the roundtable discussed the importance of talking to parents – particularly pregnant mothers – about the dangers of marijuana use around kids, keeping marijuana and related products away from children, what’s being done on the legislative side to keep marijuana away from children and adolescents, and the long-term ramifications of marijuana use by children and their parents.

Joining Dr. Bunik for this discussion are Dr. George Sam Wang, Ayelet Talmi, Ph.D., Dr. Karen M. Wilson, Dr. Kathryn M. Wells, and Dr. Erica M. Wymore of the University of Colorado at Aurora, and Dr. Leslie R. Walker of the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Wang disclosed receiving a grant from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environments, and royalties from author contributions. The other presenters had no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Experts from Colorado and Washington – two states which have legalized recreational use of the drug – came together at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies to discuss the challenges of treating and preventing short-term and long-term illness brought on by marijuana use.

“In Colorado, a lot of [mothers] use [marijuana] for depression, anxiety, as well as for nausea, and they’re not disclosing that” to their primary care doctors, explained Dr. Maya Bunik of the University of Colorado in Aurora. “Then they’re sort of surprised at birth when we tell them that we don’t know what [marijuana] does in terms of affecting [their] baby.”

In a series of interviews, presenters at the roundtable discussed the importance of talking to parents – particularly pregnant mothers – about the dangers of marijuana use around kids, keeping marijuana and related products away from children, what’s being done on the legislative side to keep marijuana away from children and adolescents, and the long-term ramifications of marijuana use by children and their parents.

Joining Dr. Bunik for this discussion are Dr. George Sam Wang, Ayelet Talmi, Ph.D., Dr. Karen M. Wilson, Dr. Kathryn M. Wells, and Dr. Erica M. Wymore of the University of Colorado at Aurora, and Dr. Leslie R. Walker of the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Wang disclosed receiving a grant from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environments, and royalties from author contributions. The other presenters had no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Experts from Colorado and Washington – two states which have legalized recreational use of the drug – came together at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies to discuss the challenges of treating and preventing short-term and long-term illness brought on by marijuana use.

“In Colorado, a lot of [mothers] use [marijuana] for depression, anxiety, as well as for nausea, and they’re not disclosing that” to their primary care doctors, explained Dr. Maya Bunik of the University of Colorado in Aurora. “Then they’re sort of surprised at birth when we tell them that we don’t know what [marijuana] does in terms of affecting [their] baby.”

In a series of interviews, presenters at the roundtable discussed the importance of talking to parents – particularly pregnant mothers – about the dangers of marijuana use around kids, keeping marijuana and related products away from children, what’s being done on the legislative side to keep marijuana away from children and adolescents, and the long-term ramifications of marijuana use by children and their parents.

Joining Dr. Bunik for this discussion are Dr. George Sam Wang, Ayelet Talmi, Ph.D., Dr. Karen M. Wilson, Dr. Kathryn M. Wells, and Dr. Erica M. Wymore of the University of Colorado at Aurora, and Dr. Leslie R. Walker of the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Wang disclosed receiving a grant from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environments, and royalties from author contributions. The other presenters had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Teens with ADHD likely to stop medications on their own, may not restart

BALTIMORE – Almost all teenagers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) stopped their medication at some point during their teen years, a study showed.

The stoppages happened for a variety of reasons, many of which stemmed from the normal curiosity and independence of adolescence, especially as teens got older.

Further, almost three-quarters of adolescents with ADHD did not restart medication after stopping, a concerning statistic given the often poor outcomes for youth with untreated ADHD, said Dr. William Brinkman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

A better understanding of the reasons why adolescents come off and on ADHD medication may help physicians and families craft smart approaches to keep youth on track during the experimental teenage years, according to Dr. Brinkman, who presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Using data from the National Institute of Mental Health–supported Multimodal Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) trial, Dr. Brinkman and his collaborators collated and analyzed the responses of 394 participants who had ever taken medication for ADHD.

The MTA study was a 14-month randomized clinical trial with a community control group, a behavior therapy group, a medication management group, and a combined treatment group. Naturalistic longitudinal follow-up extended for 12 years. At the end of study follow-up, participants were a mean 21.0 years old; 78% were male, and most (67%) were white.

Using a self-report measure developed in the MTA study, participants reported the age when they last had stopped taking ADHD medication and/or had restarted it. They also used a 6-point Likert scale to endorse how “true” a variety of reasons were for them to have stopped, or restarted, their ADHD medication. Scale responses ranged from 1, “really true,” to 6, “not at all true.”

Dr. Brinkman and his colleagues dichotomized the responses so that responses from 1 to 3 were characterized as “true,” while responses from 4 to 6 were characterized as “not true” when descriptive statistics were used.

Nearly all teenagers – 95% (376/394) – reported stopping their medication at some point. Commonly reported reasons for stopping included “I felt I could manage without it” (81%), “I wanted to find out if I could manage without it,” (68%), and “I was doing so well I no longer needed it” (68%). Dr. Brinkman noted that these stoppage reasons all fell into the broad category of feeling the medicine was not helping, or being curious about what would happen when they stopped taking the medicine.

Another common reason was very simple, but not easily categorized: 69% of respondents who had stopped medication endorsed the statement, “I was tired of taking it.” Almost half (46%) of respondents reported that physical side effects were a contributor to stopping the medication, while others said they stopped for the summer (30%), or that their parents had made the decision to stop the medication (26%).

Only 28% of youth in the MTA study who had stopped their medication restarted it. Of those who did, most reported they did so because the medication helped them: More than 80% of respondents felt that it helped with concentration and focus at school or work, or that it made school or work easier. Some participants felt that ADHD medication helped them organize their thoughts (68%), while 36% felt it helped decrease impulsivity.

The age at which respondents reported they had stopped or restarted their medication was broken down into childhood, aged 5-12; adolescence, aged 13-17; and emerging adulthood, aged 18-22 years. This was done so that trends in the reasons for stopping and restarting could be tracked by age.

“Parent/doctor influence decreases, while teencentric reasons increase” through adolescence, said Dr. Brinkman. The effect of parental or physician decision making about stopping or restarting medication declined significantly over the course of adolescence. The steepest declines were seen in endorsements of the statements, “My parents decided to stop it” and “My parents decided to restart it” (P for both less than .0001). The reason with the steepest increase as adolescents became adults was “I was allowed to decide when to take it” (P less than .0001).

A safer way to get teens through the experimentation and drive for autonomy that are natural parts of growing up may be physician-supervised trials on/off medicine to help curious teens more objectively assess the continued need for medicine.

Study data were drawn from the National Institutes of Mental Health–funded MTA study. Dr. Brinkman reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Almost all teenagers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) stopped their medication at some point during their teen years, a study showed.

The stoppages happened for a variety of reasons, many of which stemmed from the normal curiosity and independence of adolescence, especially as teens got older.

Further, almost three-quarters of adolescents with ADHD did not restart medication after stopping, a concerning statistic given the often poor outcomes for youth with untreated ADHD, said Dr. William Brinkman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

A better understanding of the reasons why adolescents come off and on ADHD medication may help physicians and families craft smart approaches to keep youth on track during the experimental teenage years, according to Dr. Brinkman, who presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Using data from the National Institute of Mental Health–supported Multimodal Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) trial, Dr. Brinkman and his collaborators collated and analyzed the responses of 394 participants who had ever taken medication for ADHD.

The MTA study was a 14-month randomized clinical trial with a community control group, a behavior therapy group, a medication management group, and a combined treatment group. Naturalistic longitudinal follow-up extended for 12 years. At the end of study follow-up, participants were a mean 21.0 years old; 78% were male, and most (67%) were white.

Using a self-report measure developed in the MTA study, participants reported the age when they last had stopped taking ADHD medication and/or had restarted it. They also used a 6-point Likert scale to endorse how “true” a variety of reasons were for them to have stopped, or restarted, their ADHD medication. Scale responses ranged from 1, “really true,” to 6, “not at all true.”

Dr. Brinkman and his colleagues dichotomized the responses so that responses from 1 to 3 were characterized as “true,” while responses from 4 to 6 were characterized as “not true” when descriptive statistics were used.

Nearly all teenagers – 95% (376/394) – reported stopping their medication at some point. Commonly reported reasons for stopping included “I felt I could manage without it” (81%), “I wanted to find out if I could manage without it,” (68%), and “I was doing so well I no longer needed it” (68%). Dr. Brinkman noted that these stoppage reasons all fell into the broad category of feeling the medicine was not helping, or being curious about what would happen when they stopped taking the medicine.

Another common reason was very simple, but not easily categorized: 69% of respondents who had stopped medication endorsed the statement, “I was tired of taking it.” Almost half (46%) of respondents reported that physical side effects were a contributor to stopping the medication, while others said they stopped for the summer (30%), or that their parents had made the decision to stop the medication (26%).

Only 28% of youth in the MTA study who had stopped their medication restarted it. Of those who did, most reported they did so because the medication helped them: More than 80% of respondents felt that it helped with concentration and focus at school or work, or that it made school or work easier. Some participants felt that ADHD medication helped them organize their thoughts (68%), while 36% felt it helped decrease impulsivity.

The age at which respondents reported they had stopped or restarted their medication was broken down into childhood, aged 5-12; adolescence, aged 13-17; and emerging adulthood, aged 18-22 years. This was done so that trends in the reasons for stopping and restarting could be tracked by age.

“Parent/doctor influence decreases, while teencentric reasons increase” through adolescence, said Dr. Brinkman. The effect of parental or physician decision making about stopping or restarting medication declined significantly over the course of adolescence. The steepest declines were seen in endorsements of the statements, “My parents decided to stop it” and “My parents decided to restart it” (P for both less than .0001). The reason with the steepest increase as adolescents became adults was “I was allowed to decide when to take it” (P less than .0001).

A safer way to get teens through the experimentation and drive for autonomy that are natural parts of growing up may be physician-supervised trials on/off medicine to help curious teens more objectively assess the continued need for medicine.

Study data were drawn from the National Institutes of Mental Health–funded MTA study. Dr. Brinkman reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BALTIMORE – Almost all teenagers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) stopped their medication at some point during their teen years, a study showed.

The stoppages happened for a variety of reasons, many of which stemmed from the normal curiosity and independence of adolescence, especially as teens got older.

Further, almost three-quarters of adolescents with ADHD did not restart medication after stopping, a concerning statistic given the often poor outcomes for youth with untreated ADHD, said Dr. William Brinkman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

A better understanding of the reasons why adolescents come off and on ADHD medication may help physicians and families craft smart approaches to keep youth on track during the experimental teenage years, according to Dr. Brinkman, who presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Using data from the National Institute of Mental Health–supported Multimodal Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) trial, Dr. Brinkman and his collaborators collated and analyzed the responses of 394 participants who had ever taken medication for ADHD.

The MTA study was a 14-month randomized clinical trial with a community control group, a behavior therapy group, a medication management group, and a combined treatment group. Naturalistic longitudinal follow-up extended for 12 years. At the end of study follow-up, participants were a mean 21.0 years old; 78% were male, and most (67%) were white.

Using a self-report measure developed in the MTA study, participants reported the age when they last had stopped taking ADHD medication and/or had restarted it. They also used a 6-point Likert scale to endorse how “true” a variety of reasons were for them to have stopped, or restarted, their ADHD medication. Scale responses ranged from 1, “really true,” to 6, “not at all true.”

Dr. Brinkman and his colleagues dichotomized the responses so that responses from 1 to 3 were characterized as “true,” while responses from 4 to 6 were characterized as “not true” when descriptive statistics were used.

Nearly all teenagers – 95% (376/394) – reported stopping their medication at some point. Commonly reported reasons for stopping included “I felt I could manage without it” (81%), “I wanted to find out if I could manage without it,” (68%), and “I was doing so well I no longer needed it” (68%). Dr. Brinkman noted that these stoppage reasons all fell into the broad category of feeling the medicine was not helping, or being curious about what would happen when they stopped taking the medicine.

Another common reason was very simple, but not easily categorized: 69% of respondents who had stopped medication endorsed the statement, “I was tired of taking it.” Almost half (46%) of respondents reported that physical side effects were a contributor to stopping the medication, while others said they stopped for the summer (30%), or that their parents had made the decision to stop the medication (26%).

Only 28% of youth in the MTA study who had stopped their medication restarted it. Of those who did, most reported they did so because the medication helped them: More than 80% of respondents felt that it helped with concentration and focus at school or work, or that it made school or work easier. Some participants felt that ADHD medication helped them organize their thoughts (68%), while 36% felt it helped decrease impulsivity.

The age at which respondents reported they had stopped or restarted their medication was broken down into childhood, aged 5-12; adolescence, aged 13-17; and emerging adulthood, aged 18-22 years. This was done so that trends in the reasons for stopping and restarting could be tracked by age.

“Parent/doctor influence decreases, while teencentric reasons increase” through adolescence, said Dr. Brinkman. The effect of parental or physician decision making about stopping or restarting medication declined significantly over the course of adolescence. The steepest declines were seen in endorsements of the statements, “My parents decided to stop it” and “My parents decided to restart it” (P for both less than .0001). The reason with the steepest increase as adolescents became adults was “I was allowed to decide when to take it” (P less than .0001).

A safer way to get teens through the experimentation and drive for autonomy that are natural parts of growing up may be physician-supervised trials on/off medicine to help curious teens more objectively assess the continued need for medicine.

Study data were drawn from the National Institutes of Mental Health–funded MTA study. Dr. Brinkman reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Teens and young adults with ADHD are likely to stop their medication on their own, and may not restart.

Major finding: Nearly all teenagers – 95% (376/394) – reported stopping their medication at some point. Only 28% of youth who had stopped their medication restarted it.

Data source: Naturalistic longitudinal follow-up of 394 patients with ADHD from the randomized Multimodal Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder clinical trial.

Disclosures: Study data were drawn from the National Institutes of Mental Health–funded MTA study. Dr. Brinkman reported no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Children exposed to marijuana at risk for long-term neurocognitive issues

BALTIMORE – The legalization of recreational marijuana in certain states has brought with it a host of new challenges to health care professionals, particularly ob.gyns. and pediatricians, who may be faced with parents who use the drug but are unaware – or unwilling to recognize – the dangers of marijuana exposure to their children.

“A longitudinal, very good study that [showed] regular use [of marijuana] by adolescents [is] associated with about a 6-8 point reduction in adult IQ, and persistent neurocognitive deficits [that] may not even be fully reversible,” said Dr. Paula D. Riggs of the University of Colorado in Aurora.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Riggs discussed this and other key studies that point to the dangers of marijuana exposure to children, both before and after birth, and how important it is that all health care professionals ask parents the right questions to ensure that children aren’t being put in danger of long-term cognitive repercussions of marijuana use.

Dr. Riggs did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – The legalization of recreational marijuana in certain states has brought with it a host of new challenges to health care professionals, particularly ob.gyns. and pediatricians, who may be faced with parents who use the drug but are unaware – or unwilling to recognize – the dangers of marijuana exposure to their children.

“A longitudinal, very good study that [showed] regular use [of marijuana] by adolescents [is] associated with about a 6-8 point reduction in adult IQ, and persistent neurocognitive deficits [that] may not even be fully reversible,” said Dr. Paula D. Riggs of the University of Colorado in Aurora.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Riggs discussed this and other key studies that point to the dangers of marijuana exposure to children, both before and after birth, and how important it is that all health care professionals ask parents the right questions to ensure that children aren’t being put in danger of long-term cognitive repercussions of marijuana use.

Dr. Riggs did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – The legalization of recreational marijuana in certain states has brought with it a host of new challenges to health care professionals, particularly ob.gyns. and pediatricians, who may be faced with parents who use the drug but are unaware – or unwilling to recognize – the dangers of marijuana exposure to their children.

“A longitudinal, very good study that [showed] regular use [of marijuana] by adolescents [is] associated with about a 6-8 point reduction in adult IQ, and persistent neurocognitive deficits [that] may not even be fully reversible,” said Dr. Paula D. Riggs of the University of Colorado in Aurora.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Riggs discussed this and other key studies that point to the dangers of marijuana exposure to children, both before and after birth, and how important it is that all health care professionals ask parents the right questions to ensure that children aren’t being put in danger of long-term cognitive repercussions of marijuana use.

Dr. Riggs did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

After 2006 Recommendation, More Autism Diagnoses Made at Earlier Age

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

After 2006 recommendation, more autism diagnoses made at earlier age

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder occurred significantly earlier for children born in 2005 or later, compared with children born in prior years, suggesting an impact from the 2006 U.S. recommendation for universal screening at age 18 months.

Major finding: Age at autism diagnosis fell from 45 months in children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months in those born later.

Data source: Review of 512 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at one U.S. center during 2003-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Valicenti-McDermott had no disclosures.

VIDEO: Caring for transgender youth will require care across specialties

BALTIMORE – Training in transgender care needs to be amplified across all specialties, including pediatrics, as the number of transgender individuals, both young and old, continues to climb.

“We all have a gender, we all have a gender identity, we all have a way in which we express that to the world around us, and to ignore that part of a human being [and] a patient would be a real detriment [to] our society,” explained Dr. Kristen Eckstrand a resident in the child psychiatry program at the University of Pittsburgh.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Eckstrand discussed strategies for talking to transgender patients to provide the best care for them, and the importance of working across professions and specialties when the situation calls for it.

Dr. Eckstrand did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Go to LGBT Youth Consult on our site for articles on the nature of sexuality and gender identity and how they affect health, advice on how to talk with your patients about these topics, and how to make your office a safe place for LGBT youth.

BALTIMORE – Training in transgender care needs to be amplified across all specialties, including pediatrics, as the number of transgender individuals, both young and old, continues to climb.

“We all have a gender, we all have a gender identity, we all have a way in which we express that to the world around us, and to ignore that part of a human being [and] a patient would be a real detriment [to] our society,” explained Dr. Kristen Eckstrand a resident in the child psychiatry program at the University of Pittsburgh.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Eckstrand discussed strategies for talking to transgender patients to provide the best care for them, and the importance of working across professions and specialties when the situation calls for it.

Dr. Eckstrand did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Go to LGBT Youth Consult on our site for articles on the nature of sexuality and gender identity and how they affect health, advice on how to talk with your patients about these topics, and how to make your office a safe place for LGBT youth.

BALTIMORE – Training in transgender care needs to be amplified across all specialties, including pediatrics, as the number of transgender individuals, both young and old, continues to climb.

“We all have a gender, we all have a gender identity, we all have a way in which we express that to the world around us, and to ignore that part of a human being [and] a patient would be a real detriment [to] our society,” explained Dr. Kristen Eckstrand a resident in the child psychiatry program at the University of Pittsburgh.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Eckstrand discussed strategies for talking to transgender patients to provide the best care for them, and the importance of working across professions and specialties when the situation calls for it.

Dr. Eckstrand did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Go to LGBT Youth Consult on our site for articles on the nature of sexuality and gender identity and how they affect health, advice on how to talk with your patients about these topics, and how to make your office a safe place for LGBT youth.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

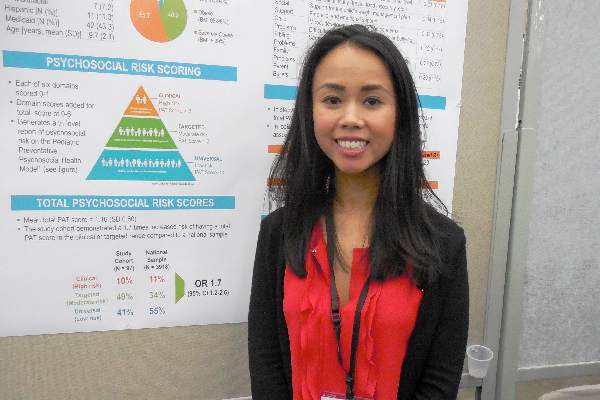

Family’s Psychosocial Problems Complicate Pediatric Obesity

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.