User login

Surgical Infection Society (SIS): Annual Meeting

For empiric candidemia treatment, echinocandin tops fluconazole

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Of candidemia patients, 25% had C. glabrata, which is resistant to fluconazole and is associated with in-hospital mortality.

Data Source: A retrospective study of 91 candidemia patients

Disclosures: Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Vancomycin, properly dosed, is as safe on the kidneys as linezolid

LAS VEGAS – Vancomycin is as safe on the kidneys of critically ill patients as linezolid, so long as trough levels don’t exceed the recommended upper limit of 20 mcg/mL, according to researchers from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

"When correct dosing is performed, the use of alternative agents to treat Gram-positive infections – specifically to avoid [vancomycin] nephrotoxicity – is unnecessary. Vancomycin use in critically ill patients is no different than linezolid use regarding nephrotoxicity or new-onset need for hemodialysis," said lead investigator Stephen Davies, a resident in the department of surgery, said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The kidney safety of vancomycin has been in doubt, with mixed results from prior studies. To shed light on the issue, Dr. Davies and his team compared renal outcomes in 298 critically ill patients treated with vancomycin for 571 Gram-positive infections with outcomes in 247 patients treated with linezolid for 475 Gram-positive infections.

Infection sites included the lungs, peritoneum, blood stream, and urinary tract, among others, and isolates included Staphylococcus aureus (77 methicillin-resistant S. aureus), Enterococcus faecium (67 vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus), E. faecalis, and Streptococcus species. Vancomycin patients were dosed at 15-20 mg/kg, with serial trough monitoring, and treated for a mean of 16.2 days, vs. 14.3 days for linezolid. Patients were on no other nephrotoxic agents.

In the end, "there were no [statistically significant] differences between the two groups regarding maximum creatinine during treatment, final creatinine after treatment, change in creatinine maximum and initial values, and final and initial creatinine values." There were also no differences "in new-onset hemodialysis or death," Dr. Davies said.

APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scores above 30 and initial creatinine levels above 1.2 mg/dL both predicted the need for new-onset hemodialysis, but antibiotic choice did not.

Those same two variables also predicted an increase in creatinine of more than 1.0 mg/dl during treatment; vancomycin use did, as well (relative risk, vancomycin 0.49; 95% confidence interval: 0.25-0.94). Concerned, the team looked into the issue. "What we found was that a rise in creatinine was typically not encountered until trough levels greater than 20 mg/dL were reached. As long as you stay within the recommended doses, you should be safe," Dr. Davies said.

There were no statistically significant baseline differences between the two groups in renal function, hemodialysis, creatinine levels, or APACHE II scores.

Despite the results, Dr. Philip Barie, who helped moderate Dr. Davies’ talk, said in an interview that he’s still concerned about vancomycin kidney safety.

"We are having to use higher doses to treat tougher bugs, and whereas nephrotoxicity pretty much went away with vancomycin after they purified the drug [decades ago], now we are having to use higher doses more, and nephrotoxicity is beginning to creep back into the picture. You have to dose really carefully, and if you have an organism that is among the more resistant to vancomycin, the safest thing to do with vancomycin is to use linezolid," said Dr. Barie, a professor of surgery and public heath at Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Davies and Dr. Barie reported no relevant disclosures.

Multiple factors must be considered in determining the optimal antibiotic treatment of gram-positive infections including but not limited to clinical and microbiological efficacy, development of resistant microorganisms, adverse effects, and costs. Several recent meta-analyses have reported conflicting results regarding whether linezolid is superior to vancomycin in clinical and/or microbiological efficacy, but all have reported increased nephrotoxicity with vancomycin (PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58240; Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013;41:426-33; Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013).

However, none of these performed metaregression analyses to determine whether there is an association between vancomycin troughs and risk of nephrotoxicity. While the study by Dr. Davies et al. suggests such a relationship, there is inadequate data to determine if the higher vancomycin troughs, which were associated with creatinine elevations above 1.0 mg/dL, were necessary to eradicate the Gram-positive infections. Furthermore, despite the adjustment for severity of illness, there may have been a selection bias in the initial choice of antibiotics. Lastly, treatment selection for Gram-positive infections should also take into account: the costs and resources necessary to monitor vancomycin troughs, and the feasibility of performing timely and appropriate dose adjustments based on troughs to achieve a therapeutic yet nontoxic level.

Lillian S. Kao, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Multiple factors must be considered in determining the optimal antibiotic treatment of gram-positive infections including but not limited to clinical and microbiological efficacy, development of resistant microorganisms, adverse effects, and costs. Several recent meta-analyses have reported conflicting results regarding whether linezolid is superior to vancomycin in clinical and/or microbiological efficacy, but all have reported increased nephrotoxicity with vancomycin (PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58240; Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013;41:426-33; Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013).

However, none of these performed metaregression analyses to determine whether there is an association between vancomycin troughs and risk of nephrotoxicity. While the study by Dr. Davies et al. suggests such a relationship, there is inadequate data to determine if the higher vancomycin troughs, which were associated with creatinine elevations above 1.0 mg/dL, were necessary to eradicate the Gram-positive infections. Furthermore, despite the adjustment for severity of illness, there may have been a selection bias in the initial choice of antibiotics. Lastly, treatment selection for Gram-positive infections should also take into account: the costs and resources necessary to monitor vancomycin troughs, and the feasibility of performing timely and appropriate dose adjustments based on troughs to achieve a therapeutic yet nontoxic level.

Lillian S. Kao, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Multiple factors must be considered in determining the optimal antibiotic treatment of gram-positive infections including but not limited to clinical and microbiological efficacy, development of resistant microorganisms, adverse effects, and costs. Several recent meta-analyses have reported conflicting results regarding whether linezolid is superior to vancomycin in clinical and/or microbiological efficacy, but all have reported increased nephrotoxicity with vancomycin (PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58240; Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013;41:426-33; Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013).

However, none of these performed metaregression analyses to determine whether there is an association between vancomycin troughs and risk of nephrotoxicity. While the study by Dr. Davies et al. suggests such a relationship, there is inadequate data to determine if the higher vancomycin troughs, which were associated with creatinine elevations above 1.0 mg/dL, were necessary to eradicate the Gram-positive infections. Furthermore, despite the adjustment for severity of illness, there may have been a selection bias in the initial choice of antibiotics. Lastly, treatment selection for Gram-positive infections should also take into account: the costs and resources necessary to monitor vancomycin troughs, and the feasibility of performing timely and appropriate dose adjustments based on troughs to achieve a therapeutic yet nontoxic level.

Lillian S. Kao, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

LAS VEGAS – Vancomycin is as safe on the kidneys of critically ill patients as linezolid, so long as trough levels don’t exceed the recommended upper limit of 20 mcg/mL, according to researchers from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

"When correct dosing is performed, the use of alternative agents to treat Gram-positive infections – specifically to avoid [vancomycin] nephrotoxicity – is unnecessary. Vancomycin use in critically ill patients is no different than linezolid use regarding nephrotoxicity or new-onset need for hemodialysis," said lead investigator Stephen Davies, a resident in the department of surgery, said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The kidney safety of vancomycin has been in doubt, with mixed results from prior studies. To shed light on the issue, Dr. Davies and his team compared renal outcomes in 298 critically ill patients treated with vancomycin for 571 Gram-positive infections with outcomes in 247 patients treated with linezolid for 475 Gram-positive infections.

Infection sites included the lungs, peritoneum, blood stream, and urinary tract, among others, and isolates included Staphylococcus aureus (77 methicillin-resistant S. aureus), Enterococcus faecium (67 vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus), E. faecalis, and Streptococcus species. Vancomycin patients were dosed at 15-20 mg/kg, with serial trough monitoring, and treated for a mean of 16.2 days, vs. 14.3 days for linezolid. Patients were on no other nephrotoxic agents.

In the end, "there were no [statistically significant] differences between the two groups regarding maximum creatinine during treatment, final creatinine after treatment, change in creatinine maximum and initial values, and final and initial creatinine values." There were also no differences "in new-onset hemodialysis or death," Dr. Davies said.

APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scores above 30 and initial creatinine levels above 1.2 mg/dL both predicted the need for new-onset hemodialysis, but antibiotic choice did not.

Those same two variables also predicted an increase in creatinine of more than 1.0 mg/dl during treatment; vancomycin use did, as well (relative risk, vancomycin 0.49; 95% confidence interval: 0.25-0.94). Concerned, the team looked into the issue. "What we found was that a rise in creatinine was typically not encountered until trough levels greater than 20 mg/dL were reached. As long as you stay within the recommended doses, you should be safe," Dr. Davies said.

There were no statistically significant baseline differences between the two groups in renal function, hemodialysis, creatinine levels, or APACHE II scores.

Despite the results, Dr. Philip Barie, who helped moderate Dr. Davies’ talk, said in an interview that he’s still concerned about vancomycin kidney safety.

"We are having to use higher doses to treat tougher bugs, and whereas nephrotoxicity pretty much went away with vancomycin after they purified the drug [decades ago], now we are having to use higher doses more, and nephrotoxicity is beginning to creep back into the picture. You have to dose really carefully, and if you have an organism that is among the more resistant to vancomycin, the safest thing to do with vancomycin is to use linezolid," said Dr. Barie, a professor of surgery and public heath at Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Davies and Dr. Barie reported no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Vancomycin is as safe on the kidneys of critically ill patients as linezolid, so long as trough levels don’t exceed the recommended upper limit of 20 mcg/mL, according to researchers from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

"When correct dosing is performed, the use of alternative agents to treat Gram-positive infections – specifically to avoid [vancomycin] nephrotoxicity – is unnecessary. Vancomycin use in critically ill patients is no different than linezolid use regarding nephrotoxicity or new-onset need for hemodialysis," said lead investigator Stephen Davies, a resident in the department of surgery, said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The kidney safety of vancomycin has been in doubt, with mixed results from prior studies. To shed light on the issue, Dr. Davies and his team compared renal outcomes in 298 critically ill patients treated with vancomycin for 571 Gram-positive infections with outcomes in 247 patients treated with linezolid for 475 Gram-positive infections.

Infection sites included the lungs, peritoneum, blood stream, and urinary tract, among others, and isolates included Staphylococcus aureus (77 methicillin-resistant S. aureus), Enterococcus faecium (67 vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus), E. faecalis, and Streptococcus species. Vancomycin patients were dosed at 15-20 mg/kg, with serial trough monitoring, and treated for a mean of 16.2 days, vs. 14.3 days for linezolid. Patients were on no other nephrotoxic agents.

In the end, "there were no [statistically significant] differences between the two groups regarding maximum creatinine during treatment, final creatinine after treatment, change in creatinine maximum and initial values, and final and initial creatinine values." There were also no differences "in new-onset hemodialysis or death," Dr. Davies said.

APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scores above 30 and initial creatinine levels above 1.2 mg/dL both predicted the need for new-onset hemodialysis, but antibiotic choice did not.

Those same two variables also predicted an increase in creatinine of more than 1.0 mg/dl during treatment; vancomycin use did, as well (relative risk, vancomycin 0.49; 95% confidence interval: 0.25-0.94). Concerned, the team looked into the issue. "What we found was that a rise in creatinine was typically not encountered until trough levels greater than 20 mg/dL were reached. As long as you stay within the recommended doses, you should be safe," Dr. Davies said.

There were no statistically significant baseline differences between the two groups in renal function, hemodialysis, creatinine levels, or APACHE II scores.

Despite the results, Dr. Philip Barie, who helped moderate Dr. Davies’ talk, said in an interview that he’s still concerned about vancomycin kidney safety.

"We are having to use higher doses to treat tougher bugs, and whereas nephrotoxicity pretty much went away with vancomycin after they purified the drug [decades ago], now we are having to use higher doses more, and nephrotoxicity is beginning to creep back into the picture. You have to dose really carefully, and if you have an organism that is among the more resistant to vancomycin, the safest thing to do with vancomycin is to use linezolid," said Dr. Barie, a professor of surgery and public heath at Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Davies and Dr. Barie reported no relevant disclosures.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Vancomycin is as safe on the kidneys of critically ill patients as linezolid, so long as trough levels don’t exceed the recommended upper limit of 20 mcg/mL.

Data source: Single-center, retrospective cohort study in 545 critically ill patients

Disclosures: The lead investigator said he has no financial conflicts.

Hypoglycemia linked to increased morbidity risk in pediatric burn patients

LAS VEGAS – Although inpatient glucose levels in critically ill adults are generally kept between 140 and 180 mg/dL, Toronto investigators have found that it might be best to keep pediatric burn patients between 130 and 140 mg/dL.

Morbidity and mortality outcomes were better in that range when 760 children – the majority boys under 10 years old burned over half their bodies, usually by flame – were followed for 2 months after ICU admission.

"We used about 300,000 glucose measurements" during the study "to determine the ideal glucose target. For burn patients, the range of 130-140 mg/dL should be targeted. You avoid hyperglycemia as well as hypoglycemia. [Also,] a major factor to be considered" in burns "is that protein glycosylation starts at around 150 mg/dL; we burn surgeons try to be below that," said lead researcher Dr. Marc Jeschke, director of the burn center at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Dr. Jeschke’s study isn’t the first to suggest that range for critically ill children. "There seems to be a signal [across] studies that this is the range we should target in order to see the benefits of glucose control," he said (e.g., J. Pediatr. 2009;155:734-9).

It’s been known that burns cause a hyperglycemic response, especially those in excess of 40% of the body. When not reined in, "you lose more grafts, you have more infections, and you [are more likely to] die," Dr. Jeschke said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

In its investigation, however, his team also found that, as in critically ill adults, hypoglycemia must also be avoided in pediatric burn patients.

Eighty-five patients had one hypoglycemia episode in the study, defined as blood glucose below 60?mg/dL, and 107 had two or more. The remaining 568 children had no episodes.

Twenty-one percent of patients who had hypoglycemic episodes – versus 6.5% of those who did not – developed sepsis; 47.9%, versus 10%, developed multiple organ failure, and a quarter died. Mortality was 3.3% in the nonhypoglycemic group. The differences were statistically significant.

"We [also] found that hypoglycemic patients are more inflammatory and hypermetabolic," Dr. Jeschke said.

Hypoglycemia was associated with larger burns and more inhalation injuries, so the team did a propensity analysis comparing 166 children who had hypoglycemic episodes to 166 with similar injury severities who did not.

Among those matched patients, children were 2.67 more likely to die (95% confidence interval 1.15-6.20) if they had one hypoglycemic episode, 5.58 more likely to die if they had two (95% CI 2.26-13.81), and 9.25 times more likely if they had three (95% CI 4.30-19.88).

Hypoglycemia during sepsis or at time of death was excluded in the analysis. Even so, "we don’t know" if hypoglycemia was the cause of death or a marker for another fatal process, Dr. Jeschke noted.

Whatever the case, the results indicate that just as in sick adults, "glycemic control in [pediatric] burns is an integral part of good clinical outcomes," he said.

Dr. Jeschke said he has no conflicts of interest.

Glycemic control in critically ill patients, both children and adults, has been extensively studied in the past decade. Despite the evidence for harms associated with hyperglycemia such as increased risk of infection, the optimal glucose range for critically ill patients is a moving target. As noted in Dr. Jeschke's study, the risk of mortality in critically ill pediatric burn patients treated with an insulin protocol increased as the number of hypoglycemic episodes (below 60 mg/dL) increased.

Despite the initial rapid adoption of tight glycemic control in critically ill patients, the benefits have not always outweighed the harms. Thus, in implementing glycemic control regimens, attention needs to be focused not only on the treatment of hyperglycemia but also on the avoidance of hypoglycemia in order to ensure good patient outcomes.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Glycemic control in critically ill patients, both children and adults, has been extensively studied in the past decade. Despite the evidence for harms associated with hyperglycemia such as increased risk of infection, the optimal glucose range for critically ill patients is a moving target. As noted in Dr. Jeschke's study, the risk of mortality in critically ill pediatric burn patients treated with an insulin protocol increased as the number of hypoglycemic episodes (below 60 mg/dL) increased.

Despite the initial rapid adoption of tight glycemic control in critically ill patients, the benefits have not always outweighed the harms. Thus, in implementing glycemic control regimens, attention needs to be focused not only on the treatment of hyperglycemia but also on the avoidance of hypoglycemia in order to ensure good patient outcomes.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Glycemic control in critically ill patients, both children and adults, has been extensively studied in the past decade. Despite the evidence for harms associated with hyperglycemia such as increased risk of infection, the optimal glucose range for critically ill patients is a moving target. As noted in Dr. Jeschke's study, the risk of mortality in critically ill pediatric burn patients treated with an insulin protocol increased as the number of hypoglycemic episodes (below 60 mg/dL) increased.

Despite the initial rapid adoption of tight glycemic control in critically ill patients, the benefits have not always outweighed the harms. Thus, in implementing glycemic control regimens, attention needs to be focused not only on the treatment of hyperglycemia but also on the avoidance of hypoglycemia in order to ensure good patient outcomes.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

LAS VEGAS – Although inpatient glucose levels in critically ill adults are generally kept between 140 and 180 mg/dL, Toronto investigators have found that it might be best to keep pediatric burn patients between 130 and 140 mg/dL.

Morbidity and mortality outcomes were better in that range when 760 children – the majority boys under 10 years old burned over half their bodies, usually by flame – were followed for 2 months after ICU admission.

"We used about 300,000 glucose measurements" during the study "to determine the ideal glucose target. For burn patients, the range of 130-140 mg/dL should be targeted. You avoid hyperglycemia as well as hypoglycemia. [Also,] a major factor to be considered" in burns "is that protein glycosylation starts at around 150 mg/dL; we burn surgeons try to be below that," said lead researcher Dr. Marc Jeschke, director of the burn center at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Dr. Jeschke’s study isn’t the first to suggest that range for critically ill children. "There seems to be a signal [across] studies that this is the range we should target in order to see the benefits of glucose control," he said (e.g., J. Pediatr. 2009;155:734-9).

It’s been known that burns cause a hyperglycemic response, especially those in excess of 40% of the body. When not reined in, "you lose more grafts, you have more infections, and you [are more likely to] die," Dr. Jeschke said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

In its investigation, however, his team also found that, as in critically ill adults, hypoglycemia must also be avoided in pediatric burn patients.

Eighty-five patients had one hypoglycemia episode in the study, defined as blood glucose below 60?mg/dL, and 107 had two or more. The remaining 568 children had no episodes.

Twenty-one percent of patients who had hypoglycemic episodes – versus 6.5% of those who did not – developed sepsis; 47.9%, versus 10%, developed multiple organ failure, and a quarter died. Mortality was 3.3% in the nonhypoglycemic group. The differences were statistically significant.

"We [also] found that hypoglycemic patients are more inflammatory and hypermetabolic," Dr. Jeschke said.

Hypoglycemia was associated with larger burns and more inhalation injuries, so the team did a propensity analysis comparing 166 children who had hypoglycemic episodes to 166 with similar injury severities who did not.

Among those matched patients, children were 2.67 more likely to die (95% confidence interval 1.15-6.20) if they had one hypoglycemic episode, 5.58 more likely to die if they had two (95% CI 2.26-13.81), and 9.25 times more likely if they had three (95% CI 4.30-19.88).

Hypoglycemia during sepsis or at time of death was excluded in the analysis. Even so, "we don’t know" if hypoglycemia was the cause of death or a marker for another fatal process, Dr. Jeschke noted.

Whatever the case, the results indicate that just as in sick adults, "glycemic control in [pediatric] burns is an integral part of good clinical outcomes," he said.

Dr. Jeschke said he has no conflicts of interest.

LAS VEGAS – Although inpatient glucose levels in critically ill adults are generally kept between 140 and 180 mg/dL, Toronto investigators have found that it might be best to keep pediatric burn patients between 130 and 140 mg/dL.

Morbidity and mortality outcomes were better in that range when 760 children – the majority boys under 10 years old burned over half their bodies, usually by flame – were followed for 2 months after ICU admission.

"We used about 300,000 glucose measurements" during the study "to determine the ideal glucose target. For burn patients, the range of 130-140 mg/dL should be targeted. You avoid hyperglycemia as well as hypoglycemia. [Also,] a major factor to be considered" in burns "is that protein glycosylation starts at around 150 mg/dL; we burn surgeons try to be below that," said lead researcher Dr. Marc Jeschke, director of the burn center at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Dr. Jeschke’s study isn’t the first to suggest that range for critically ill children. "There seems to be a signal [across] studies that this is the range we should target in order to see the benefits of glucose control," he said (e.g., J. Pediatr. 2009;155:734-9).

It’s been known that burns cause a hyperglycemic response, especially those in excess of 40% of the body. When not reined in, "you lose more grafts, you have more infections, and you [are more likely to] die," Dr. Jeschke said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

In its investigation, however, his team also found that, as in critically ill adults, hypoglycemia must also be avoided in pediatric burn patients.

Eighty-five patients had one hypoglycemia episode in the study, defined as blood glucose below 60?mg/dL, and 107 had two or more. The remaining 568 children had no episodes.

Twenty-one percent of patients who had hypoglycemic episodes – versus 6.5% of those who did not – developed sepsis; 47.9%, versus 10%, developed multiple organ failure, and a quarter died. Mortality was 3.3% in the nonhypoglycemic group. The differences were statistically significant.

"We [also] found that hypoglycemic patients are more inflammatory and hypermetabolic," Dr. Jeschke said.

Hypoglycemia was associated with larger burns and more inhalation injuries, so the team did a propensity analysis comparing 166 children who had hypoglycemic episodes to 166 with similar injury severities who did not.

Among those matched patients, children were 2.67 more likely to die (95% confidence interval 1.15-6.20) if they had one hypoglycemic episode, 5.58 more likely to die if they had two (95% CI 2.26-13.81), and 9.25 times more likely if they had three (95% CI 4.30-19.88).

Hypoglycemia during sepsis or at time of death was excluded in the analysis. Even so, "we don’t know" if hypoglycemia was the cause of death or a marker for another fatal process, Dr. Jeschke noted.

Whatever the case, the results indicate that just as in sick adults, "glycemic control in [pediatric] burns is an integral part of good clinical outcomes," he said.

Dr. Jeschke said he has no conflicts of interest.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Severely burned children are almost three times more likely to die if they have even one hypoglycemic episode.

Data Source: Retrospective review of 760 pediatric burn patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator said he has no disclosures.

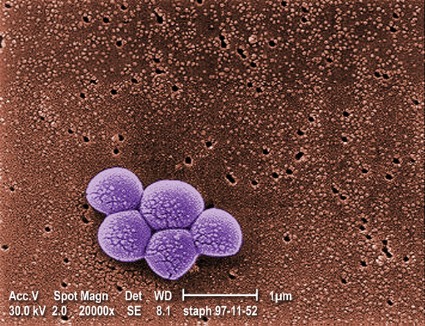

Swab both the nose and throat to catch Staph colonization

LAS VEGAS – It’s a good idea to swab both the throat and nose when looking for Staphylococcus aureus colonization; doing so picks up cases missed by swabbing the nares alone, according to researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

That holds true whether testing is by culture or PCR [polymerase chain reaction], said the lead investigator, Dr. Meredith Knofsky, a surgery resident there.

The team swabbed both areas preoperatively and on the day of surgery in patients undergoing operations involving hardware implants, such as new knees or hips. The 109 samples they obtained were then tested for methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) S. aureus by both MRSA select media culture and the GeneXpert PCR system.

By culture, 7 throat swabs and 18 nares swabs were positive for MRSA; 20 throat and 40 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

By PCR, 7 throat and 21 nares samples were MRSA positive; 33 throat and 51 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

The detection rate differences weren’t surprising; PCR is known to be more accurate and the results confirm its greater sensitivity, Dr. Knofsky said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The bigger finding is that "throat screening identifies additional patients missed by screening the nares alone," she said.

Adding PCR throat testing to PCR nasal screening picked up one additional MRSA and 14 additional MSSA carriers. Similarly, the addition of throat cultures to nares cultures picked up an additional MRSA and eight additional MSSA carriers.

Not infrequently, patients were positive in one location, such as the throat, but not in the other. Although "nasal carrier status of Staphylococcus aureus is an important risk factor for surgical site infections," it’s not known at the moment if that’s also true for carriage limited to the throat, Dr. Knofsky said.

"We have plans to go back and evaluate which of these patients colonized only in the oropharynx actually developed a surgical site infection. It’s important that we invest in evaluating pharyngeal carriage," she said.

In the meantime, session moderator and surgeon Dr. E. Patchen Dellinger of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that MSSA in the study "was two to three times more common than MRSA; an MSSA infection of implanted hardware is just as devastating to the patient as an MRSA infection. I would like to urge that we not focus on MRSA alone, but consider at least in selected surgical populations seeking and suppressing any Staph that colonizes our surgical patients."

PCR could help with that because it "has the advantage of very rapid answers. The logistics of getting [colonization] information in time to do something [before an operation] is very difficult for us. PCR could make that better, [but it] isn’t standard of care mostly because it costs a lot more" than does culture, he said.

Dr. Knofsky and Dr. Dellinger said they have no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – It’s a good idea to swab both the throat and nose when looking for Staphylococcus aureus colonization; doing so picks up cases missed by swabbing the nares alone, according to researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

That holds true whether testing is by culture or PCR [polymerase chain reaction], said the lead investigator, Dr. Meredith Knofsky, a surgery resident there.

The team swabbed both areas preoperatively and on the day of surgery in patients undergoing operations involving hardware implants, such as new knees or hips. The 109 samples they obtained were then tested for methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) S. aureus by both MRSA select media culture and the GeneXpert PCR system.

By culture, 7 throat swabs and 18 nares swabs were positive for MRSA; 20 throat and 40 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

By PCR, 7 throat and 21 nares samples were MRSA positive; 33 throat and 51 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

The detection rate differences weren’t surprising; PCR is known to be more accurate and the results confirm its greater sensitivity, Dr. Knofsky said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The bigger finding is that "throat screening identifies additional patients missed by screening the nares alone," she said.

Adding PCR throat testing to PCR nasal screening picked up one additional MRSA and 14 additional MSSA carriers. Similarly, the addition of throat cultures to nares cultures picked up an additional MRSA and eight additional MSSA carriers.

Not infrequently, patients were positive in one location, such as the throat, but not in the other. Although "nasal carrier status of Staphylococcus aureus is an important risk factor for surgical site infections," it’s not known at the moment if that’s also true for carriage limited to the throat, Dr. Knofsky said.

"We have plans to go back and evaluate which of these patients colonized only in the oropharynx actually developed a surgical site infection. It’s important that we invest in evaluating pharyngeal carriage," she said.

In the meantime, session moderator and surgeon Dr. E. Patchen Dellinger of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that MSSA in the study "was two to three times more common than MRSA; an MSSA infection of implanted hardware is just as devastating to the patient as an MRSA infection. I would like to urge that we not focus on MRSA alone, but consider at least in selected surgical populations seeking and suppressing any Staph that colonizes our surgical patients."

PCR could help with that because it "has the advantage of very rapid answers. The logistics of getting [colonization] information in time to do something [before an operation] is very difficult for us. PCR could make that better, [but it] isn’t standard of care mostly because it costs a lot more" than does culture, he said.

Dr. Knofsky and Dr. Dellinger said they have no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – It’s a good idea to swab both the throat and nose when looking for Staphylococcus aureus colonization; doing so picks up cases missed by swabbing the nares alone, according to researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

That holds true whether testing is by culture or PCR [polymerase chain reaction], said the lead investigator, Dr. Meredith Knofsky, a surgery resident there.

The team swabbed both areas preoperatively and on the day of surgery in patients undergoing operations involving hardware implants, such as new knees or hips. The 109 samples they obtained were then tested for methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) S. aureus by both MRSA select media culture and the GeneXpert PCR system.

By culture, 7 throat swabs and 18 nares swabs were positive for MRSA; 20 throat and 40 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

By PCR, 7 throat and 21 nares samples were MRSA positive; 33 throat and 51 nares swabs were positive for MSSA.

The detection rate differences weren’t surprising; PCR is known to be more accurate and the results confirm its greater sensitivity, Dr. Knofsky said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

The bigger finding is that "throat screening identifies additional patients missed by screening the nares alone," she said.

Adding PCR throat testing to PCR nasal screening picked up one additional MRSA and 14 additional MSSA carriers. Similarly, the addition of throat cultures to nares cultures picked up an additional MRSA and eight additional MSSA carriers.

Not infrequently, patients were positive in one location, such as the throat, but not in the other. Although "nasal carrier status of Staphylococcus aureus is an important risk factor for surgical site infections," it’s not known at the moment if that’s also true for carriage limited to the throat, Dr. Knofsky said.

"We have plans to go back and evaluate which of these patients colonized only in the oropharynx actually developed a surgical site infection. It’s important that we invest in evaluating pharyngeal carriage," she said.

In the meantime, session moderator and surgeon Dr. E. Patchen Dellinger of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that MSSA in the study "was two to three times more common than MRSA; an MSSA infection of implanted hardware is just as devastating to the patient as an MRSA infection. I would like to urge that we not focus on MRSA alone, but consider at least in selected surgical populations seeking and suppressing any Staph that colonizes our surgical patients."

PCR could help with that because it "has the advantage of very rapid answers. The logistics of getting [colonization] information in time to do something [before an operation] is very difficult for us. PCR could make that better, [but it] isn’t standard of care mostly because it costs a lot more" than does culture, he said.

Dr. Knofsky and Dr. Dellinger said they have no relevant disclosures.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: In an analysis of 109 throat and nares swabs, the addition of PCR throat testing to PCR nasal screening picked up one additional MRSA and 14 additional MSSA carriers. Similarly, the addition of throat cultures to nares cultures picked up an additional MRSA and eight additional MSSA carriers.

Data source: Samples from presurgical patients

Disclosures: The lead investigator said she has no disclosures.

Insulin resistance may predict ventilator-associated pneumonia

LAS VEGAS – The development of euglycemic insulin resistance soon after intubation may herald the onset of ventilator-associated pneumonia, a study by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., has shown.

Researchers compared 92 critically injured trauma patients who developed VAP (ventilator-associated pneumonia) 3-4 days after intubation with 2,162 who did not. All the subjects had their blood glucose levels kept mostly between 80 and 150 mg/dL with the help of a computer-assisted protocol that adjusted insulin drip rates as necessary, lead investigator Dr. Kaushik Mukherjee reported at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

There were no differences in baseline demographics between the two groups, but compared with controls, patients who developed VAP needed significantly higher insulin drip rates to stay in that range the day before and the first and third days after they met clinical criteria for VAP diagnosis (maximum difference, 1.1 U/hr [95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P less than .001]).

The M multiplier, a surrogate for insulin resistance calculated from blood glucose levels and insulin drip rates, was significantly higher 2 days before VAP was diagnosed, and remained so for 10 days afterward.

If the findings hold up with further investigation, the Vanderbilt team believes they may one day help predict who’s at risk for VAP so that preventative measures can be taken. Among other things, the model will need to incorporate body mass index, steroid use, tube-feeding schedule, and other confounders that impact insulin requirements, and be put through a prospective trial.

Even so, "these data indicate euglycemic insulin resistance may be an important new indicator for VAP in the era of strict glycemic control. [This] may be valuable moving forward," said Dr. Mukherjee of Vanderbilt’s division of trauma and surgical critical care.

"We believe that critically injured patients with VAP show euglycemic insulin resistance as measured by the multiplier, and we think [that] could be predictive of infection. We are hoping to turn this into an insulin resistance–based screening tool for VAP that would help us decide when we should obtain a [bronchoalveolar lavage]. Earlier detection of pneumonias could result in earlier antibiotic therapy and survival," he said.

Patients in the study were at least 16 years old, and had been ventilated for at least 48 hours.

Both VAP and control patients needed increasing amounts of insulin in the 10 days following intubation, probably "due to added nutrition, but [the VAP group required] a more rapid increase in their insulin infusion rates" starting about 3 days before VAP was diagnosed.

Overall, VAP patients had lower blood glucose levels both before and after diagnosis and were less likely to exceed the target range. "We think it’s because their innate ability to control glucose [was more] impaired, [so] there was less variability from the patient’s own system," Dr. Mukherjee said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – The development of euglycemic insulin resistance soon after intubation may herald the onset of ventilator-associated pneumonia, a study by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., has shown.

Researchers compared 92 critically injured trauma patients who developed VAP (ventilator-associated pneumonia) 3-4 days after intubation with 2,162 who did not. All the subjects had their blood glucose levels kept mostly between 80 and 150 mg/dL with the help of a computer-assisted protocol that adjusted insulin drip rates as necessary, lead investigator Dr. Kaushik Mukherjee reported at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

There were no differences in baseline demographics between the two groups, but compared with controls, patients who developed VAP needed significantly higher insulin drip rates to stay in that range the day before and the first and third days after they met clinical criteria for VAP diagnosis (maximum difference, 1.1 U/hr [95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P less than .001]).

The M multiplier, a surrogate for insulin resistance calculated from blood glucose levels and insulin drip rates, was significantly higher 2 days before VAP was diagnosed, and remained so for 10 days afterward.

If the findings hold up with further investigation, the Vanderbilt team believes they may one day help predict who’s at risk for VAP so that preventative measures can be taken. Among other things, the model will need to incorporate body mass index, steroid use, tube-feeding schedule, and other confounders that impact insulin requirements, and be put through a prospective trial.

Even so, "these data indicate euglycemic insulin resistance may be an important new indicator for VAP in the era of strict glycemic control. [This] may be valuable moving forward," said Dr. Mukherjee of Vanderbilt’s division of trauma and surgical critical care.

"We believe that critically injured patients with VAP show euglycemic insulin resistance as measured by the multiplier, and we think [that] could be predictive of infection. We are hoping to turn this into an insulin resistance–based screening tool for VAP that would help us decide when we should obtain a [bronchoalveolar lavage]. Earlier detection of pneumonias could result in earlier antibiotic therapy and survival," he said.

Patients in the study were at least 16 years old, and had been ventilated for at least 48 hours.

Both VAP and control patients needed increasing amounts of insulin in the 10 days following intubation, probably "due to added nutrition, but [the VAP group required] a more rapid increase in their insulin infusion rates" starting about 3 days before VAP was diagnosed.

Overall, VAP patients had lower blood glucose levels both before and after diagnosis and were less likely to exceed the target range. "We think it’s because their innate ability to control glucose [was more] impaired, [so] there was less variability from the patient’s own system," Dr. Mukherjee said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – The development of euglycemic insulin resistance soon after intubation may herald the onset of ventilator-associated pneumonia, a study by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., has shown.

Researchers compared 92 critically injured trauma patients who developed VAP (ventilator-associated pneumonia) 3-4 days after intubation with 2,162 who did not. All the subjects had their blood glucose levels kept mostly between 80 and 150 mg/dL with the help of a computer-assisted protocol that adjusted insulin drip rates as necessary, lead investigator Dr. Kaushik Mukherjee reported at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

There were no differences in baseline demographics between the two groups, but compared with controls, patients who developed VAP needed significantly higher insulin drip rates to stay in that range the day before and the first and third days after they met clinical criteria for VAP diagnosis (maximum difference, 1.1 U/hr [95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P less than .001]).

The M multiplier, a surrogate for insulin resistance calculated from blood glucose levels and insulin drip rates, was significantly higher 2 days before VAP was diagnosed, and remained so for 10 days afterward.

If the findings hold up with further investigation, the Vanderbilt team believes they may one day help predict who’s at risk for VAP so that preventative measures can be taken. Among other things, the model will need to incorporate body mass index, steroid use, tube-feeding schedule, and other confounders that impact insulin requirements, and be put through a prospective trial.

Even so, "these data indicate euglycemic insulin resistance may be an important new indicator for VAP in the era of strict glycemic control. [This] may be valuable moving forward," said Dr. Mukherjee of Vanderbilt’s division of trauma and surgical critical care.

"We believe that critically injured patients with VAP show euglycemic insulin resistance as measured by the multiplier, and we think [that] could be predictive of infection. We are hoping to turn this into an insulin resistance–based screening tool for VAP that would help us decide when we should obtain a [bronchoalveolar lavage]. Earlier detection of pneumonias could result in earlier antibiotic therapy and survival," he said.

Patients in the study were at least 16 years old, and had been ventilated for at least 48 hours.

Both VAP and control patients needed increasing amounts of insulin in the 10 days following intubation, probably "due to added nutrition, but [the VAP group required] a more rapid increase in their insulin infusion rates" starting about 3 days before VAP was diagnosed.

Overall, VAP patients had lower blood glucose levels both before and after diagnosis and were less likely to exceed the target range. "We think it’s because their innate ability to control glucose [was more] impaired, [so] there was less variability from the patient’s own system," Dr. Mukherjee said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Ninety-two patients had a sharp increase in insulin requirements shortly before they were diagnosed with ventilator-associated pneumonia; 2,162 ventilated controls did not.

Data Source: A retrospective, single-center study.

Disclosures: The lead investigator reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Antibiotics after damage control laparotomy up infection risk

LAS VEGAS – Trauma patients should not get antibiotics after damage control or primarily closed laparotomies because this treatment may increase the risk of postsurgical intra-abdominal infections, according to a study from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, a Level 1 trauma center.

The abdomen is often left open for a while after a damage control laparotomy (DCL), especially when patients are coagulopathic, acidotic, or at risk for an abdominal compartment syndrome. In those cases, "people just automatically assume ‘Open abdomen: Throw on the antibiotics.’ What we are showing here is don’t throw on the antibiotics," said lead investigator Dr. Stephanie Goldberg of the trauma, critical care, and emergency surgery faculty at VCU. The worry is probably the same for primarily closed (PC) laparotomies, when the fascia is closed but skin is sometimes left open.

The findings are important because although – and as the team found – preoperative antibiotics are known to reduce the risk of postsurgical abdominal infections, there’s not much evidence in either direction for their use after trauma laparotomies, so "no one knows what to do." Some surgeons opt for antibiotics, others don’t, Dr. Goldberg said.

To help figure out the right approach, her team analyzed perioperative antibiotic use and infection rates in 28 DCL patients whose abdomens were left open, and 93 PC patients. The PC group had a mean injury severity score of 18; 35.5% (33) had bowel injuries. The DCL group was in worse shape, with a mean severity score of 31.4 and bowel injuries in 53.6% (15).

Everyone should have been dosed with an antibiotic before surgery; 94.6% (88) PC patients, but only 69.2% (19) DCL patients, actually were. "It’s likely," in the DCL cases especially, "that patients were so sick and there was so much chaos in the operating room that giving pre-op antibiotics got missed," Dr. Goldberg said.

Postop antibiotic use differed significantly between the groups; 50.5% (47) of PC patients got no antibiotics, 21.5% (20) got a day’s worth, and 28% (26) were treated for more than a day. In the DCL group, 21.4% (6) got no antibiotics, 25.0% (7) a 1-day course, and 53.6% (15) more than a 1-day course.

As expected, preop antibiotics protected against intra-abdominal infections (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval 0.05-0.91; P = .037). Postoperative antibiotics, however, substantially increased the risk (OR, 6.7; 95% CI 1.33 – 33.8; P= .044).

The longer patients were on antibiotics, the greater that risk became. Among the 6 DCL patients who received no postsurgical antibiotics, 16.7% (1) developed an intra-abdominal infection. Among the 7 treated for a day, 28.6% (2) developed an intra-abdominal infection; 40% (6) did so among the 15 treated for more than a day. The trend was similar for PC patients, although the overall infection rates were lower.

Antimicrobial resistance could be to blame. As normal flora were wiped out, maybe the field was cleared for "bugs to cause problems that otherwise would not have," explained senior investigator Dr. Thèrese Duane of the department of surgery at VCU. Surgeons there tend to favor Zosyn or Cefoxitin.

The project was just the first step toward building a robust evidence base about antibiotic use after trauma laparotomies. Next on the team’s agenda is a multicenter, prospective trial.

"We need more numbers," Dr. Duane said.

Dr. Goldberg has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Duane speaks for Pfizer on behalf of its antibiotic, linezolid.

Antibiotics after damage-control laparotomy up the infection risk. This study by Dr. Goldberg and her colleagues highlights areas for process improvement with antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent organ space surgical site infection (SSI) in trauma patients undergoing damage control or primarily closed laparotomies. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been consistently demonstrated across meta-analyses of randomized trials to be effective in preventing SSIs regardless of the type of surgery; this study supports similar benefits in trauma laparotomy patients. Furthermore, given that only 69% of DCL patients received preoperative antibiotics, there was significant room for improvement.

Antibiotic stewardship has also been at the forefront of recent efforts to improve perioperative care. Level I evidence exists for not continuing postoperative antibiotics beyond 24 hours in patients undergoing trauma laparotomies for penetrating injuries. Although less well studied, there is no evidence to suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis practices after laparotomy for blunt injuries or for damage control should differ. Further studies are necessary to determine optimal methods for delivering appropriate preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and to identify additional perioperative strategies to reduce superficial, deep, and organ space SSIs in these high-risk patients.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao is in the department of surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Dr. Kao has no conflict of interest disclosures.

Antibiotics after damage-control laparotomy up the infection risk. This study by Dr. Goldberg and her colleagues highlights areas for process improvement with antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent organ space surgical site infection (SSI) in trauma patients undergoing damage control or primarily closed laparotomies. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been consistently demonstrated across meta-analyses of randomized trials to be effective in preventing SSIs regardless of the type of surgery; this study supports similar benefits in trauma laparotomy patients. Furthermore, given that only 69% of DCL patients received preoperative antibiotics, there was significant room for improvement.

Antibiotic stewardship has also been at the forefront of recent efforts to improve perioperative care. Level I evidence exists for not continuing postoperative antibiotics beyond 24 hours in patients undergoing trauma laparotomies for penetrating injuries. Although less well studied, there is no evidence to suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis practices after laparotomy for blunt injuries or for damage control should differ. Further studies are necessary to determine optimal methods for delivering appropriate preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and to identify additional perioperative strategies to reduce superficial, deep, and organ space SSIs in these high-risk patients.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao is in the department of surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Dr. Kao has no conflict of interest disclosures.

Antibiotics after damage-control laparotomy up the infection risk. This study by Dr. Goldberg and her colleagues highlights areas for process improvement with antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent organ space surgical site infection (SSI) in trauma patients undergoing damage control or primarily closed laparotomies. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been consistently demonstrated across meta-analyses of randomized trials to be effective in preventing SSIs regardless of the type of surgery; this study supports similar benefits in trauma laparotomy patients. Furthermore, given that only 69% of DCL patients received preoperative antibiotics, there was significant room for improvement.

Antibiotic stewardship has also been at the forefront of recent efforts to improve perioperative care. Level I evidence exists for not continuing postoperative antibiotics beyond 24 hours in patients undergoing trauma laparotomies for penetrating injuries. Although less well studied, there is no evidence to suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis practices after laparotomy for blunt injuries or for damage control should differ. Further studies are necessary to determine optimal methods for delivering appropriate preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and to identify additional perioperative strategies to reduce superficial, deep, and organ space SSIs in these high-risk patients.

Dr. Lillian S. Kao is in the department of surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Dr. Kao has no conflict of interest disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Trauma patients should not get antibiotics after damage control or primarily closed laparotomies because this treatment may increase the risk of postsurgical intra-abdominal infections, according to a study from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, a Level 1 trauma center.

The abdomen is often left open for a while after a damage control laparotomy (DCL), especially when patients are coagulopathic, acidotic, or at risk for an abdominal compartment syndrome. In those cases, "people just automatically assume ‘Open abdomen: Throw on the antibiotics.’ What we are showing here is don’t throw on the antibiotics," said lead investigator Dr. Stephanie Goldberg of the trauma, critical care, and emergency surgery faculty at VCU. The worry is probably the same for primarily closed (PC) laparotomies, when the fascia is closed but skin is sometimes left open.

The findings are important because although – and as the team found – preoperative antibiotics are known to reduce the risk of postsurgical abdominal infections, there’s not much evidence in either direction for their use after trauma laparotomies, so "no one knows what to do." Some surgeons opt for antibiotics, others don’t, Dr. Goldberg said.

To help figure out the right approach, her team analyzed perioperative antibiotic use and infection rates in 28 DCL patients whose abdomens were left open, and 93 PC patients. The PC group had a mean injury severity score of 18; 35.5% (33) had bowel injuries. The DCL group was in worse shape, with a mean severity score of 31.4 and bowel injuries in 53.6% (15).

Everyone should have been dosed with an antibiotic before surgery; 94.6% (88) PC patients, but only 69.2% (19) DCL patients, actually were. "It’s likely," in the DCL cases especially, "that patients were so sick and there was so much chaos in the operating room that giving pre-op antibiotics got missed," Dr. Goldberg said.

Postop antibiotic use differed significantly between the groups; 50.5% (47) of PC patients got no antibiotics, 21.5% (20) got a day’s worth, and 28% (26) were treated for more than a day. In the DCL group, 21.4% (6) got no antibiotics, 25.0% (7) a 1-day course, and 53.6% (15) more than a 1-day course.

As expected, preop antibiotics protected against intra-abdominal infections (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval 0.05-0.91; P = .037). Postoperative antibiotics, however, substantially increased the risk (OR, 6.7; 95% CI 1.33 – 33.8; P= .044).

The longer patients were on antibiotics, the greater that risk became. Among the 6 DCL patients who received no postsurgical antibiotics, 16.7% (1) developed an intra-abdominal infection. Among the 7 treated for a day, 28.6% (2) developed an intra-abdominal infection; 40% (6) did so among the 15 treated for more than a day. The trend was similar for PC patients, although the overall infection rates were lower.

Antimicrobial resistance could be to blame. As normal flora were wiped out, maybe the field was cleared for "bugs to cause problems that otherwise would not have," explained senior investigator Dr. Thèrese Duane of the department of surgery at VCU. Surgeons there tend to favor Zosyn or Cefoxitin.

The project was just the first step toward building a robust evidence base about antibiotic use after trauma laparotomies. Next on the team’s agenda is a multicenter, prospective trial.

"We need more numbers," Dr. Duane said.

Dr. Goldberg has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Duane speaks for Pfizer on behalf of its antibiotic, linezolid.

LAS VEGAS – Trauma patients should not get antibiotics after damage control or primarily closed laparotomies because this treatment may increase the risk of postsurgical intra-abdominal infections, according to a study from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, a Level 1 trauma center.

The abdomen is often left open for a while after a damage control laparotomy (DCL), especially when patients are coagulopathic, acidotic, or at risk for an abdominal compartment syndrome. In those cases, "people just automatically assume ‘Open abdomen: Throw on the antibiotics.’ What we are showing here is don’t throw on the antibiotics," said lead investigator Dr. Stephanie Goldberg of the trauma, critical care, and emergency surgery faculty at VCU. The worry is probably the same for primarily closed (PC) laparotomies, when the fascia is closed but skin is sometimes left open.

The findings are important because although – and as the team found – preoperative antibiotics are known to reduce the risk of postsurgical abdominal infections, there’s not much evidence in either direction for their use after trauma laparotomies, so "no one knows what to do." Some surgeons opt for antibiotics, others don’t, Dr. Goldberg said.

To help figure out the right approach, her team analyzed perioperative antibiotic use and infection rates in 28 DCL patients whose abdomens were left open, and 93 PC patients. The PC group had a mean injury severity score of 18; 35.5% (33) had bowel injuries. The DCL group was in worse shape, with a mean severity score of 31.4 and bowel injuries in 53.6% (15).

Everyone should have been dosed with an antibiotic before surgery; 94.6% (88) PC patients, but only 69.2% (19) DCL patients, actually were. "It’s likely," in the DCL cases especially, "that patients were so sick and there was so much chaos in the operating room that giving pre-op antibiotics got missed," Dr. Goldberg said.

Postop antibiotic use differed significantly between the groups; 50.5% (47) of PC patients got no antibiotics, 21.5% (20) got a day’s worth, and 28% (26) were treated for more than a day. In the DCL group, 21.4% (6) got no antibiotics, 25.0% (7) a 1-day course, and 53.6% (15) more than a 1-day course.

As expected, preop antibiotics protected against intra-abdominal infections (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval 0.05-0.91; P = .037). Postoperative antibiotics, however, substantially increased the risk (OR, 6.7; 95% CI 1.33 – 33.8; P= .044).

The longer patients were on antibiotics, the greater that risk became. Among the 6 DCL patients who received no postsurgical antibiotics, 16.7% (1) developed an intra-abdominal infection. Among the 7 treated for a day, 28.6% (2) developed an intra-abdominal infection; 40% (6) did so among the 15 treated for more than a day. The trend was similar for PC patients, although the overall infection rates were lower.

Antimicrobial resistance could be to blame. As normal flora were wiped out, maybe the field was cleared for "bugs to cause problems that otherwise would not have," explained senior investigator Dr. Thèrese Duane of the department of surgery at VCU. Surgeons there tend to favor Zosyn or Cefoxitin.

The project was just the first step toward building a robust evidence base about antibiotic use after trauma laparotomies. Next on the team’s agenda is a multicenter, prospective trial.

"We need more numbers," Dr. Duane said.

Dr. Goldberg has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Duane speaks for Pfizer on behalf of its antibiotic, linezolid.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SURGICAL INFECTION SOCIETY

Major finding: Patients who were given antibiotics after trauma laparotomies are six times more likely to develop an intra-abdominal infection than were those who are not (OR, 6.7; 95% CI 1.33-33.8; P = .044).

Data Source: Retrospective review of 121 trauma laparotomies

Disclosures: The lead investigator has no relevant disclosures. The senior investigator speaks for Pfizer on behalf of its antibiotic, linezolid.

Fever after c-section may not be endometritis

LAS VEGAS – Until recently, residents and surgeons at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center routinely misdiagnosed normal postoperative fever after cesarean section as endometritis, significantly effecting the deep surgical site infection rates reported on websites such as Hospital Compare, according to an investigation by the medical center’s infectious disease experts.

All it took to fix the problem were a few Power Point presentations to make physicians aware of what was going on. Within months, the hospital’s deep-seated c-section infection rate dropped from 2.32 to 0.84 per 100 patients, according to Dr. Madhuri Sopirala, the center’s medical director of infection control, who led the investigation and subsequent educational efforts.

"I don’t believe this is unique to our institution. I am familiar with a lot of other hospitals and practices. This is not uncommon" or limited to c-sections, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

"Postoperative fevers happen in a majority of patients," resolve in a day or two, and usually have nothing to do with infection, she noted. Even so, they are often diagnosed and treated as infections out of an abundance of caution.

That’s a problem at a time when surgical site infection rates are among the hospital quality measures reported to the public and, increasingly, affecting the bottom line. Also, "giving antibiotics to patients who don’t need them is not a good thing," Dr. Sopirala added.

The investigation began after she and her colleagues noticed that postcesarean endometritis accounted for a significant proportion of the medical center’s deep surgical site infections.

They found that 78 patients were diagnosed with endometritis after vaginal deliveries or c-sections between January 2011 and June 2012. Forty-four patients were sent home after just a day or two of antibiotics; only 8 patients were readmitted within 30 days.

Most of the 20 post c-section endometritis cases diagnosed between July 2011 and June 2012 got just a few antibiotic doses, too; none of them returned to the hospital.

The numbers just didn’t add up, Dr. Sopirala said. Endometritis is a serious infection; if patients sent home after a dose or two of antibiotics truly had endometritis, more would have been back within a month, seriously ill.

They didn’t come back "because they didn’t need to. It wasn’t really endometritis. These patients most likely had postoperative fever," she said.

"Fever is the most common indication for antibiotics in this country. Whenever a patient has a fever, people give them antibiotics just in case, then find some reason to [justify it]. Endometritis is the most common thing that comes to mind in a patient that’s had a c-section," she said.

Residents and faculty were glad to be made aware of the problem. "The data speak for themselves," Dr. Sopirala said.

Instead of diagnosing postcesarean fevers as endometritis, they "started monitoring temperatures, and could see them coming down on their own. Before, when the fever came down, they assumed it was a response to the antibiotics," she said.

Following the educational efforts, there were no c-section endometritis cases diagnosed at the center between July 2012 and March 2013.

Dr. Sopirala said that she has no disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Until recently, residents and surgeons at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center routinely misdiagnosed normal postoperative fever after cesarean section as endometritis, significantly effecting the deep surgical site infection rates reported on websites such as Hospital Compare, according to an investigation by the medical center’s infectious disease experts.

All it took to fix the problem were a few Power Point presentations to make physicians aware of what was going on. Within months, the hospital’s deep-seated c-section infection rate dropped from 2.32 to 0.84 per 100 patients, according to Dr. Madhuri Sopirala, the center’s medical director of infection control, who led the investigation and subsequent educational efforts.

"I don’t believe this is unique to our institution. I am familiar with a lot of other hospitals and practices. This is not uncommon" or limited to c-sections, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

"Postoperative fevers happen in a majority of patients," resolve in a day or two, and usually have nothing to do with infection, she noted. Even so, they are often diagnosed and treated as infections out of an abundance of caution.

That’s a problem at a time when surgical site infection rates are among the hospital quality measures reported to the public and, increasingly, affecting the bottom line. Also, "giving antibiotics to patients who don’t need them is not a good thing," Dr. Sopirala added.

The investigation began after she and her colleagues noticed that postcesarean endometritis accounted for a significant proportion of the medical center’s deep surgical site infections.

They found that 78 patients were diagnosed with endometritis after vaginal deliveries or c-sections between January 2011 and June 2012. Forty-four patients were sent home after just a day or two of antibiotics; only 8 patients were readmitted within 30 days.

Most of the 20 post c-section endometritis cases diagnosed between July 2011 and June 2012 got just a few antibiotic doses, too; none of them returned to the hospital.

The numbers just didn’t add up, Dr. Sopirala said. Endometritis is a serious infection; if patients sent home after a dose or two of antibiotics truly had endometritis, more would have been back within a month, seriously ill.

They didn’t come back "because they didn’t need to. It wasn’t really endometritis. These patients most likely had postoperative fever," she said.

"Fever is the most common indication for antibiotics in this country. Whenever a patient has a fever, people give them antibiotics just in case, then find some reason to [justify it]. Endometritis is the most common thing that comes to mind in a patient that’s had a c-section," she said.

Residents and faculty were glad to be made aware of the problem. "The data speak for themselves," Dr. Sopirala said.