User login

First clinical evidence of neuroprotection in acute stroke?

LOS ANGELES – A new potential neuroprotectant agent has been found to be beneficial for patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular thrombectomy in a large placebo-controlled trial, but only for those patients who did not also receive thrombolysis.

There was no difference between groups on the primary outcome in the main analysis of the trial, lead author Michael Hill, MD, reported.

However, “In our study, we found a dramatic interaction of nerinetide with alteplase. There was a large benefit of nerinetide in patients not given thrombolysis, but in patients who received alteplase, this benefit was completely obliterated,” Dr. Hill said in an interview.

“In patients not treated with thrombolysis, we found a large effect size with a 9.5% absolute improvement in patients having an independent outcome (modified Rankin Score [mRS] 0-2) and a number need to treat of 10 to 11,” he said. “We also found a mortality benefit and a reduction in the size of strokes, with all other secondary outcomes going in the right direction.

“The drug works really well in patients who do not get thrombolysis, but it doesn’t work at all in patients who have had thrombolysis. The thrombolytic appears to break the peptide down so it is inactive,” he added.

“This is the first evidence that neuroprotection is possible in human stroke. This has never been shown before,” Dr. Hill noted. “Many previous clinical trials of potential neuroprotectants have been negative. We think this is a major breakthrough. This is pretty exciting stuff with really tantalizing results.”

Dr. Hill, professor of neurology at the University of Calgary (Alta.), presented results of the ESCAPE-NA1 trial on Feb. 20 at the International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020. The trial was also simultaneously published online (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30258-0).

Endogenous nitric oxide

The new agent – known as NA1 or nerinetide – is a 20-amino-acid peptide with a novel mechanism of action; it inhibits signaling that leads to neuronal excitotoxicity. “It reduces endogenous nitric oxide generated inside the cell during ischemia, which is one of the main biochemical processes contributing to cell death,” Dr. Hill explained. In a primate model of ischemia reperfusion that was published in Nature in 2012, it was highly protective, he added.

The drug is given just once at the time of thrombectomy. It is short lived in the blood but detectable in the brain for up to 24 hours, he said.

The trial included 1,105 patients who had experienced acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion within a 12-hour treatment window and for whom imaging results suitable for thrombectomy were available. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous nerinetide in a single dose of 2.6 mg/kg or saline placebo at the time of thrombectomy.

Patients were stratified by intravenous alteplase treatment and by declared endovascular device choice.

The primary outcome was a favorable functional outcome 90 days after randomization, defined as an mRS score of 0-2. In the main analysis of the whole population, this favorable outcome was achieved for 61.4% of the group that received nerinetide and for 59.2% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. Secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups.

But an exploratory analysis showed evidence that nerinetide’s treatment effect was modified by alteplase treatment. Among the patients who did not receive alteplase, use of nerinetide was associated with improved outcomes, whereas no benefit was found in the alteplase stratum. The difference in absolute risk slightly but not significantly favored placebo.

In the stratum that did not receive alteplase (40% of the trial population), the favorable mRS outcome was achieved by 59.3% of patients who received nerinetide, compared with 49.8% of those given placebo – a significant difference (adjusted risk ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38).

There was also a 7.5% absolute risk reduction in mortality at 90 days post treatment with nerinetide for the patients who did not receive thrombolysis. This resulted in an approximate halving of the hazard of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.56).

In addition, infarct size was reduced in those patients who received nerinetide but not thrombolysis.

Among the patients who received alteplase, the proportion of patients who achieved an mRS of 0-2 was similar between groups, as were median infarct volumes.

The observed treatment effect modification by alteplase was supported by reductions in peak plasma nerinetide concentrations in the alteplase stratum, the researchers reported.

They said that the combination of the clinical results in the no-thrombolytic stratum and subsequent tests documenting that nerinetide is broken down by plasmin (which is generated by alteplase) “provide evidence that the clinical observation of effect modification is not a chance finding.” But they added: “This novel observation will require additional confirmation, and we cannot draw a definitive conclusion on treatment effect in this study.”

“Shaking up the field”

There is still more work to do, Dr. Hill said. “We don’t fully understand the pharmacology, and we will certainly have to do another trial, but we believe this agent is going to shake the field up. This is a totally new drug, and we have to think carefully about where it could fit in.”

“The obvious first group is those patients who do not receive thrombolysis. This is a large group, as most patients do not present in time for thrombolysis. Then we can work on the biochemistry and see if we can develop a version of nerinetide that is resistant to breakdown by thrombolysis,” he said.

Another possibility would be to withhold thrombolysis and give nerinetide instead. “It may be that thrombolysis is not needed if patients are receiving thrombectomy – this is being suggested now in initial studies,” Hill stated.

They also chose a very select group of patients – those undergoing thrombectomy, who represent only 10% to 15% of stroke patients. “We have to work out how to expand that population,” he said.

Hill noted that there have been many examples in the past of potential neuroprotectant agents that have worked in animal models of ischemia-reperfusion but that failed in humans with acute stroke.

“Until recently, we have not had a reliable ischemia-reperfusion model in humans, but now with endovascular therapy, we have a situation where the blood flow is reliably restored, which is an ideal situation to test new neuroprotectant agents. That may be another factor that has contributed to our positive findings,” he said.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, Graeme J. Hankey, MD, of the University of Western Australia, Perth, noted that although endovascular thrombectomy after use of intravenous alteplase improves reperfusion and clinical outcomes for a fifth of patients with ischemic stroke caused by large-artery occlusion, half of patients do not recover an independent lifestyle. Cytoprotection aims to augment the resilience of neurons, neurovascular units, and white matter during ischemia until perfusion is restored (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30316-0).

Dr. Hankey also pointed out that numerous cytoprotection strategies have been reported to reduce brain infarction in preclinical models of ischemic stroke but have not been found to improve clinical outcomes in clinical trials involving patients with ischemic stroke.

The advent of thrombectomy provides an opportunity to reassess cytoprotection as an adjunctive therapy for patients with types of temporary brain ischemia that align more closely with successful preclinical models of ischemia, cytoprotection, and reperfusion, he added.

On the results of the current study and the benefit in the no-thrombolysis group, Dr. Hankey stated: “Although this result might be a chance finding or confounded by the indication for alteplase, complementary pharmacokinetic data in a small number of patients treated with nerinetide showed that alteplase lowered plasma concentrations of nerinetide, probably by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which cleaves peptide bonds not only in fibrin but also in the eicosapeptide nerinetide.”

He said the ESCAPE-NA1 trial “informs the study of cytoprotection as an adjunct therapy to reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke” and suggested that researchers who have reported encouraging results of other cytoprotective therapies for ischemic stroke should test their compounds for interactions with concurrent thrombolytic therapies.

The ESCAPE-NA1 trial was sponsored by NoNO, the company developing nerinetide. Dr. Hill has received grants from NoNO for the conduct of the study, is named on a U.S. patent for systems and methods for assisting in decision making and triaging for acute stroke patients, and owns stock in Calgary Scientific. Other coauthors are employees of NoNO or have stock options in the company. Dr. Hankey has received personal honoraria from the American Heart Association, AC Immune, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Medscape outside the area of work that he commented on.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – A new potential neuroprotectant agent has been found to be beneficial for patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular thrombectomy in a large placebo-controlled trial, but only for those patients who did not also receive thrombolysis.

There was no difference between groups on the primary outcome in the main analysis of the trial, lead author Michael Hill, MD, reported.

However, “In our study, we found a dramatic interaction of nerinetide with alteplase. There was a large benefit of nerinetide in patients not given thrombolysis, but in patients who received alteplase, this benefit was completely obliterated,” Dr. Hill said in an interview.

“In patients not treated with thrombolysis, we found a large effect size with a 9.5% absolute improvement in patients having an independent outcome (modified Rankin Score [mRS] 0-2) and a number need to treat of 10 to 11,” he said. “We also found a mortality benefit and a reduction in the size of strokes, with all other secondary outcomes going in the right direction.

“The drug works really well in patients who do not get thrombolysis, but it doesn’t work at all in patients who have had thrombolysis. The thrombolytic appears to break the peptide down so it is inactive,” he added.

“This is the first evidence that neuroprotection is possible in human stroke. This has never been shown before,” Dr. Hill noted. “Many previous clinical trials of potential neuroprotectants have been negative. We think this is a major breakthrough. This is pretty exciting stuff with really tantalizing results.”

Dr. Hill, professor of neurology at the University of Calgary (Alta.), presented results of the ESCAPE-NA1 trial on Feb. 20 at the International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020. The trial was also simultaneously published online (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30258-0).

Endogenous nitric oxide

The new agent – known as NA1 or nerinetide – is a 20-amino-acid peptide with a novel mechanism of action; it inhibits signaling that leads to neuronal excitotoxicity. “It reduces endogenous nitric oxide generated inside the cell during ischemia, which is one of the main biochemical processes contributing to cell death,” Dr. Hill explained. In a primate model of ischemia reperfusion that was published in Nature in 2012, it was highly protective, he added.

The drug is given just once at the time of thrombectomy. It is short lived in the blood but detectable in the brain for up to 24 hours, he said.

The trial included 1,105 patients who had experienced acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion within a 12-hour treatment window and for whom imaging results suitable for thrombectomy were available. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous nerinetide in a single dose of 2.6 mg/kg or saline placebo at the time of thrombectomy.

Patients were stratified by intravenous alteplase treatment and by declared endovascular device choice.

The primary outcome was a favorable functional outcome 90 days after randomization, defined as an mRS score of 0-2. In the main analysis of the whole population, this favorable outcome was achieved for 61.4% of the group that received nerinetide and for 59.2% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. Secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups.

But an exploratory analysis showed evidence that nerinetide’s treatment effect was modified by alteplase treatment. Among the patients who did not receive alteplase, use of nerinetide was associated with improved outcomes, whereas no benefit was found in the alteplase stratum. The difference in absolute risk slightly but not significantly favored placebo.

In the stratum that did not receive alteplase (40% of the trial population), the favorable mRS outcome was achieved by 59.3% of patients who received nerinetide, compared with 49.8% of those given placebo – a significant difference (adjusted risk ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38).

There was also a 7.5% absolute risk reduction in mortality at 90 days post treatment with nerinetide for the patients who did not receive thrombolysis. This resulted in an approximate halving of the hazard of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.56).

In addition, infarct size was reduced in those patients who received nerinetide but not thrombolysis.

Among the patients who received alteplase, the proportion of patients who achieved an mRS of 0-2 was similar between groups, as were median infarct volumes.

The observed treatment effect modification by alteplase was supported by reductions in peak plasma nerinetide concentrations in the alteplase stratum, the researchers reported.

They said that the combination of the clinical results in the no-thrombolytic stratum and subsequent tests documenting that nerinetide is broken down by plasmin (which is generated by alteplase) “provide evidence that the clinical observation of effect modification is not a chance finding.” But they added: “This novel observation will require additional confirmation, and we cannot draw a definitive conclusion on treatment effect in this study.”

“Shaking up the field”

There is still more work to do, Dr. Hill said. “We don’t fully understand the pharmacology, and we will certainly have to do another trial, but we believe this agent is going to shake the field up. This is a totally new drug, and we have to think carefully about where it could fit in.”

“The obvious first group is those patients who do not receive thrombolysis. This is a large group, as most patients do not present in time for thrombolysis. Then we can work on the biochemistry and see if we can develop a version of nerinetide that is resistant to breakdown by thrombolysis,” he said.

Another possibility would be to withhold thrombolysis and give nerinetide instead. “It may be that thrombolysis is not needed if patients are receiving thrombectomy – this is being suggested now in initial studies,” Hill stated.

They also chose a very select group of patients – those undergoing thrombectomy, who represent only 10% to 15% of stroke patients. “We have to work out how to expand that population,” he said.

Hill noted that there have been many examples in the past of potential neuroprotectant agents that have worked in animal models of ischemia-reperfusion but that failed in humans with acute stroke.

“Until recently, we have not had a reliable ischemia-reperfusion model in humans, but now with endovascular therapy, we have a situation where the blood flow is reliably restored, which is an ideal situation to test new neuroprotectant agents. That may be another factor that has contributed to our positive findings,” he said.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, Graeme J. Hankey, MD, of the University of Western Australia, Perth, noted that although endovascular thrombectomy after use of intravenous alteplase improves reperfusion and clinical outcomes for a fifth of patients with ischemic stroke caused by large-artery occlusion, half of patients do not recover an independent lifestyle. Cytoprotection aims to augment the resilience of neurons, neurovascular units, and white matter during ischemia until perfusion is restored (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30316-0).

Dr. Hankey also pointed out that numerous cytoprotection strategies have been reported to reduce brain infarction in preclinical models of ischemic stroke but have not been found to improve clinical outcomes in clinical trials involving patients with ischemic stroke.

The advent of thrombectomy provides an opportunity to reassess cytoprotection as an adjunctive therapy for patients with types of temporary brain ischemia that align more closely with successful preclinical models of ischemia, cytoprotection, and reperfusion, he added.

On the results of the current study and the benefit in the no-thrombolysis group, Dr. Hankey stated: “Although this result might be a chance finding or confounded by the indication for alteplase, complementary pharmacokinetic data in a small number of patients treated with nerinetide showed that alteplase lowered plasma concentrations of nerinetide, probably by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which cleaves peptide bonds not only in fibrin but also in the eicosapeptide nerinetide.”

He said the ESCAPE-NA1 trial “informs the study of cytoprotection as an adjunct therapy to reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke” and suggested that researchers who have reported encouraging results of other cytoprotective therapies for ischemic stroke should test their compounds for interactions with concurrent thrombolytic therapies.

The ESCAPE-NA1 trial was sponsored by NoNO, the company developing nerinetide. Dr. Hill has received grants from NoNO for the conduct of the study, is named on a U.S. patent for systems and methods for assisting in decision making and triaging for acute stroke patients, and owns stock in Calgary Scientific. Other coauthors are employees of NoNO or have stock options in the company. Dr. Hankey has received personal honoraria from the American Heart Association, AC Immune, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Medscape outside the area of work that he commented on.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – A new potential neuroprotectant agent has been found to be beneficial for patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular thrombectomy in a large placebo-controlled trial, but only for those patients who did not also receive thrombolysis.

There was no difference between groups on the primary outcome in the main analysis of the trial, lead author Michael Hill, MD, reported.

However, “In our study, we found a dramatic interaction of nerinetide with alteplase. There was a large benefit of nerinetide in patients not given thrombolysis, but in patients who received alteplase, this benefit was completely obliterated,” Dr. Hill said in an interview.

“In patients not treated with thrombolysis, we found a large effect size with a 9.5% absolute improvement in patients having an independent outcome (modified Rankin Score [mRS] 0-2) and a number need to treat of 10 to 11,” he said. “We also found a mortality benefit and a reduction in the size of strokes, with all other secondary outcomes going in the right direction.

“The drug works really well in patients who do not get thrombolysis, but it doesn’t work at all in patients who have had thrombolysis. The thrombolytic appears to break the peptide down so it is inactive,” he added.

“This is the first evidence that neuroprotection is possible in human stroke. This has never been shown before,” Dr. Hill noted. “Many previous clinical trials of potential neuroprotectants have been negative. We think this is a major breakthrough. This is pretty exciting stuff with really tantalizing results.”

Dr. Hill, professor of neurology at the University of Calgary (Alta.), presented results of the ESCAPE-NA1 trial on Feb. 20 at the International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020. The trial was also simultaneously published online (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30258-0).

Endogenous nitric oxide

The new agent – known as NA1 or nerinetide – is a 20-amino-acid peptide with a novel mechanism of action; it inhibits signaling that leads to neuronal excitotoxicity. “It reduces endogenous nitric oxide generated inside the cell during ischemia, which is one of the main biochemical processes contributing to cell death,” Dr. Hill explained. In a primate model of ischemia reperfusion that was published in Nature in 2012, it was highly protective, he added.

The drug is given just once at the time of thrombectomy. It is short lived in the blood but detectable in the brain for up to 24 hours, he said.

The trial included 1,105 patients who had experienced acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion within a 12-hour treatment window and for whom imaging results suitable for thrombectomy were available. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous nerinetide in a single dose of 2.6 mg/kg or saline placebo at the time of thrombectomy.

Patients were stratified by intravenous alteplase treatment and by declared endovascular device choice.

The primary outcome was a favorable functional outcome 90 days after randomization, defined as an mRS score of 0-2. In the main analysis of the whole population, this favorable outcome was achieved for 61.4% of the group that received nerinetide and for 59.2% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. Secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups.

But an exploratory analysis showed evidence that nerinetide’s treatment effect was modified by alteplase treatment. Among the patients who did not receive alteplase, use of nerinetide was associated with improved outcomes, whereas no benefit was found in the alteplase stratum. The difference in absolute risk slightly but not significantly favored placebo.

In the stratum that did not receive alteplase (40% of the trial population), the favorable mRS outcome was achieved by 59.3% of patients who received nerinetide, compared with 49.8% of those given placebo – a significant difference (adjusted risk ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38).

There was also a 7.5% absolute risk reduction in mortality at 90 days post treatment with nerinetide for the patients who did not receive thrombolysis. This resulted in an approximate halving of the hazard of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.56).

In addition, infarct size was reduced in those patients who received nerinetide but not thrombolysis.

Among the patients who received alteplase, the proportion of patients who achieved an mRS of 0-2 was similar between groups, as were median infarct volumes.

The observed treatment effect modification by alteplase was supported by reductions in peak plasma nerinetide concentrations in the alteplase stratum, the researchers reported.

They said that the combination of the clinical results in the no-thrombolytic stratum and subsequent tests documenting that nerinetide is broken down by plasmin (which is generated by alteplase) “provide evidence that the clinical observation of effect modification is not a chance finding.” But they added: “This novel observation will require additional confirmation, and we cannot draw a definitive conclusion on treatment effect in this study.”

“Shaking up the field”

There is still more work to do, Dr. Hill said. “We don’t fully understand the pharmacology, and we will certainly have to do another trial, but we believe this agent is going to shake the field up. This is a totally new drug, and we have to think carefully about where it could fit in.”

“The obvious first group is those patients who do not receive thrombolysis. This is a large group, as most patients do not present in time for thrombolysis. Then we can work on the biochemistry and see if we can develop a version of nerinetide that is resistant to breakdown by thrombolysis,” he said.

Another possibility would be to withhold thrombolysis and give nerinetide instead. “It may be that thrombolysis is not needed if patients are receiving thrombectomy – this is being suggested now in initial studies,” Hill stated.

They also chose a very select group of patients – those undergoing thrombectomy, who represent only 10% to 15% of stroke patients. “We have to work out how to expand that population,” he said.

Hill noted that there have been many examples in the past of potential neuroprotectant agents that have worked in animal models of ischemia-reperfusion but that failed in humans with acute stroke.

“Until recently, we have not had a reliable ischemia-reperfusion model in humans, but now with endovascular therapy, we have a situation where the blood flow is reliably restored, which is an ideal situation to test new neuroprotectant agents. That may be another factor that has contributed to our positive findings,” he said.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, Graeme J. Hankey, MD, of the University of Western Australia, Perth, noted that although endovascular thrombectomy after use of intravenous alteplase improves reperfusion and clinical outcomes for a fifth of patients with ischemic stroke caused by large-artery occlusion, half of patients do not recover an independent lifestyle. Cytoprotection aims to augment the resilience of neurons, neurovascular units, and white matter during ischemia until perfusion is restored (Lancet. 2020 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30316-0).

Dr. Hankey also pointed out that numerous cytoprotection strategies have been reported to reduce brain infarction in preclinical models of ischemic stroke but have not been found to improve clinical outcomes in clinical trials involving patients with ischemic stroke.

The advent of thrombectomy provides an opportunity to reassess cytoprotection as an adjunctive therapy for patients with types of temporary brain ischemia that align more closely with successful preclinical models of ischemia, cytoprotection, and reperfusion, he added.

On the results of the current study and the benefit in the no-thrombolysis group, Dr. Hankey stated: “Although this result might be a chance finding or confounded by the indication for alteplase, complementary pharmacokinetic data in a small number of patients treated with nerinetide showed that alteplase lowered plasma concentrations of nerinetide, probably by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which cleaves peptide bonds not only in fibrin but also in the eicosapeptide nerinetide.”

He said the ESCAPE-NA1 trial “informs the study of cytoprotection as an adjunct therapy to reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke” and suggested that researchers who have reported encouraging results of other cytoprotective therapies for ischemic stroke should test their compounds for interactions with concurrent thrombolytic therapies.

The ESCAPE-NA1 trial was sponsored by NoNO, the company developing nerinetide. Dr. Hill has received grants from NoNO for the conduct of the study, is named on a U.S. patent for systems and methods for assisting in decision making and triaging for acute stroke patients, and owns stock in Calgary Scientific. Other coauthors are employees of NoNO or have stock options in the company. Dr. Hankey has received personal honoraria from the American Heart Association, AC Immune, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Medscape outside the area of work that he commented on.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher endovascular thrombectomy volumes yield better stroke outcomes

LOS ANGELES – Higher case volumes matter for getting better outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with endovascular thrombectomy, according to data from more than 13,000 Medicare patients treated during 2016 and 2017.

That’s hardly surprising, given that it’s consistent with what’s already been reported for several other types of endovascular and transcatheter procedures: The more cases a center or individual proceduralist performs, the better their patients do. Routine use of endovascular thrombectomy to treat selected acute ischemic stroke patients is a new-enough paradigm that until now few reports have come out that looked at this issue (Stroke. 2019 May;50[5]:1178-83).

The new analysis of Medicare data “is one of the first contemporary studies of the volume-outcome relationship in endovascular thrombectomy,” Laura K. Stein, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. The analysis showed that, when the researchers adjusted the Medicare data to better reflect overall case volumes (Medicare patients represent just 59% of all endovascular thrombectomies performed on U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients), the minimum case number for a stroke center to have statistically better in-hospital survival than lower volume centers was 24 cases/year, and 29 cases/year to have a statistically significant higher rate of “good” outcomes than lower-volume centers, reported Dr. Stein, a stroke neurologist with the Mount Sinai Health System in New York. For individual proceduralists, the minimum, adjusted case number to have statistically better acute patient survival was 4 cases/year, and 19 cases/year to have a statistically better rate of good outcomes.

For this analysis, good outcomes were defined as cases when patients left the hospital following their acute care and returned home with either self care or a home health care service, and also patients discharged to rehabilitation. “Bad” outcomes for this analysis were discharges to a skilled nursing facility or hospice, as well as patients who died during their acute hospitalization.

The analyses also showed no plateau to the volume effect for any of the four parameters examined: in-hospital mortality by center and by proceduralist, and the rates of good outcomes by center and by proceduralist. For each of these measures, as case volume increased above the minimum number needed to produce statistically better outcomes, the rate of good outcomes continued to steadily rise and acute mortality continued to steadily fall.

The study run by Dr. Stein and associates used data collected by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services on 13,311 Medicare patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at any of 641 U.S. hospitals and received treatment from any of 2,754 thrombectomy proceduralists. Outcomes rated as good occurred in 56% of the patients. The statistical adjustments that the researchers applied to calculate the incremental effect of increasing case volume took into account the variables of patient age, sex, and comorbidities measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

The analysis also showed that, during this 2-year period, the average number of endovascular thrombectomy cases among Medicare patients was just under 21 cases per center, with a range of 1-160 cases; for individual proceduralists, the average was just under 5 cases, with a range of 1-82 cases.

The 19 case/year volume minimum that the analysis identified for an individual proceduralist to have a statistically significant higher rate of good outcomes, compared with lower-volume proceduralists, came close to the 15 cases/year minimum set by the Joint Commission in 2019 for individual operators at centers seeking accreditation from the Joint Commission as either a Thrombectomy-Capable Stroke Center or a Comprehensive Stroke Center. The CMS has not yet set thrombectomy case-load requirements for centers or operators to qualify for Medicare reimbursements, although CMS has set such standards for other endovascular procedures, such as transcatheter aortic valve replacement. When setting such standards, CMS has cited its need to balance the better outcomes produced by higher-volume centers against a societal interest in facilitating access to vital medical services, a balance that Dr. Stein also highlighted in her talk.

“We want to optimize access as well as outcomes for every patient,” she said. “These data support certification volume standards,” but they are “in no way an argument for limiting access based on volume.”

Dr. Stein had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein LK et al. ISC 2020, Abstract LB11.

The results reported by Dr. Stein raise issues about balancing the access to certain therapies with the outcomes of those therapies. Having procedures like endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke done primarily at high-volume centers might improve procedural outcomes, but having more centers offering this treatment across wider geographical areas would make this treatment more broadly available to more people.

For endovascular thrombectomy, center volume and experience may be much more important than proceduralist volume because having a smoothly functioning system in place is so important for rapid stroke assessment and treatment. It’s also important for programs to provide experienced and comprehensive postthrombectomy care. Success in endovascular thrombectomy involves much more than just taking a clot out. It means quickly and smoothly moving patients through the steps that precede thrombectomy and then following the intervention with a range of services that optimize recovery.

Ashutosh P. Jadhav, MD, PhD , is director of the comprehensive stroke center at the University of Pittsburgh. He had no relevant disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

The results reported by Dr. Stein raise issues about balancing the access to certain therapies with the outcomes of those therapies. Having procedures like endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke done primarily at high-volume centers might improve procedural outcomes, but having more centers offering this treatment across wider geographical areas would make this treatment more broadly available to more people.

For endovascular thrombectomy, center volume and experience may be much more important than proceduralist volume because having a smoothly functioning system in place is so important for rapid stroke assessment and treatment. It’s also important for programs to provide experienced and comprehensive postthrombectomy care. Success in endovascular thrombectomy involves much more than just taking a clot out. It means quickly and smoothly moving patients through the steps that precede thrombectomy and then following the intervention with a range of services that optimize recovery.

Ashutosh P. Jadhav, MD, PhD , is director of the comprehensive stroke center at the University of Pittsburgh. He had no relevant disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

The results reported by Dr. Stein raise issues about balancing the access to certain therapies with the outcomes of those therapies. Having procedures like endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke done primarily at high-volume centers might improve procedural outcomes, but having more centers offering this treatment across wider geographical areas would make this treatment more broadly available to more people.

For endovascular thrombectomy, center volume and experience may be much more important than proceduralist volume because having a smoothly functioning system in place is so important for rapid stroke assessment and treatment. It’s also important for programs to provide experienced and comprehensive postthrombectomy care. Success in endovascular thrombectomy involves much more than just taking a clot out. It means quickly and smoothly moving patients through the steps that precede thrombectomy and then following the intervention with a range of services that optimize recovery.

Ashutosh P. Jadhav, MD, PhD , is director of the comprehensive stroke center at the University of Pittsburgh. He had no relevant disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

LOS ANGELES – Higher case volumes matter for getting better outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with endovascular thrombectomy, according to data from more than 13,000 Medicare patients treated during 2016 and 2017.

That’s hardly surprising, given that it’s consistent with what’s already been reported for several other types of endovascular and transcatheter procedures: The more cases a center or individual proceduralist performs, the better their patients do. Routine use of endovascular thrombectomy to treat selected acute ischemic stroke patients is a new-enough paradigm that until now few reports have come out that looked at this issue (Stroke. 2019 May;50[5]:1178-83).

The new analysis of Medicare data “is one of the first contemporary studies of the volume-outcome relationship in endovascular thrombectomy,” Laura K. Stein, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. The analysis showed that, when the researchers adjusted the Medicare data to better reflect overall case volumes (Medicare patients represent just 59% of all endovascular thrombectomies performed on U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients), the minimum case number for a stroke center to have statistically better in-hospital survival than lower volume centers was 24 cases/year, and 29 cases/year to have a statistically significant higher rate of “good” outcomes than lower-volume centers, reported Dr. Stein, a stroke neurologist with the Mount Sinai Health System in New York. For individual proceduralists, the minimum, adjusted case number to have statistically better acute patient survival was 4 cases/year, and 19 cases/year to have a statistically better rate of good outcomes.

For this analysis, good outcomes were defined as cases when patients left the hospital following their acute care and returned home with either self care or a home health care service, and also patients discharged to rehabilitation. “Bad” outcomes for this analysis were discharges to a skilled nursing facility or hospice, as well as patients who died during their acute hospitalization.

The analyses also showed no plateau to the volume effect for any of the four parameters examined: in-hospital mortality by center and by proceduralist, and the rates of good outcomes by center and by proceduralist. For each of these measures, as case volume increased above the minimum number needed to produce statistically better outcomes, the rate of good outcomes continued to steadily rise and acute mortality continued to steadily fall.

The study run by Dr. Stein and associates used data collected by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services on 13,311 Medicare patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at any of 641 U.S. hospitals and received treatment from any of 2,754 thrombectomy proceduralists. Outcomes rated as good occurred in 56% of the patients. The statistical adjustments that the researchers applied to calculate the incremental effect of increasing case volume took into account the variables of patient age, sex, and comorbidities measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

The analysis also showed that, during this 2-year period, the average number of endovascular thrombectomy cases among Medicare patients was just under 21 cases per center, with a range of 1-160 cases; for individual proceduralists, the average was just under 5 cases, with a range of 1-82 cases.

The 19 case/year volume minimum that the analysis identified for an individual proceduralist to have a statistically significant higher rate of good outcomes, compared with lower-volume proceduralists, came close to the 15 cases/year minimum set by the Joint Commission in 2019 for individual operators at centers seeking accreditation from the Joint Commission as either a Thrombectomy-Capable Stroke Center or a Comprehensive Stroke Center. The CMS has not yet set thrombectomy case-load requirements for centers or operators to qualify for Medicare reimbursements, although CMS has set such standards for other endovascular procedures, such as transcatheter aortic valve replacement. When setting such standards, CMS has cited its need to balance the better outcomes produced by higher-volume centers against a societal interest in facilitating access to vital medical services, a balance that Dr. Stein also highlighted in her talk.

“We want to optimize access as well as outcomes for every patient,” she said. “These data support certification volume standards,” but they are “in no way an argument for limiting access based on volume.”

Dr. Stein had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein LK et al. ISC 2020, Abstract LB11.

LOS ANGELES – Higher case volumes matter for getting better outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with endovascular thrombectomy, according to data from more than 13,000 Medicare patients treated during 2016 and 2017.

That’s hardly surprising, given that it’s consistent with what’s already been reported for several other types of endovascular and transcatheter procedures: The more cases a center or individual proceduralist performs, the better their patients do. Routine use of endovascular thrombectomy to treat selected acute ischemic stroke patients is a new-enough paradigm that until now few reports have come out that looked at this issue (Stroke. 2019 May;50[5]:1178-83).

The new analysis of Medicare data “is one of the first contemporary studies of the volume-outcome relationship in endovascular thrombectomy,” Laura K. Stein, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. The analysis showed that, when the researchers adjusted the Medicare data to better reflect overall case volumes (Medicare patients represent just 59% of all endovascular thrombectomies performed on U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients), the minimum case number for a stroke center to have statistically better in-hospital survival than lower volume centers was 24 cases/year, and 29 cases/year to have a statistically significant higher rate of “good” outcomes than lower-volume centers, reported Dr. Stein, a stroke neurologist with the Mount Sinai Health System in New York. For individual proceduralists, the minimum, adjusted case number to have statistically better acute patient survival was 4 cases/year, and 19 cases/year to have a statistically better rate of good outcomes.

For this analysis, good outcomes were defined as cases when patients left the hospital following their acute care and returned home with either self care or a home health care service, and also patients discharged to rehabilitation. “Bad” outcomes for this analysis were discharges to a skilled nursing facility or hospice, as well as patients who died during their acute hospitalization.

The analyses also showed no plateau to the volume effect for any of the four parameters examined: in-hospital mortality by center and by proceduralist, and the rates of good outcomes by center and by proceduralist. For each of these measures, as case volume increased above the minimum number needed to produce statistically better outcomes, the rate of good outcomes continued to steadily rise and acute mortality continued to steadily fall.

The study run by Dr. Stein and associates used data collected by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services on 13,311 Medicare patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at any of 641 U.S. hospitals and received treatment from any of 2,754 thrombectomy proceduralists. Outcomes rated as good occurred in 56% of the patients. The statistical adjustments that the researchers applied to calculate the incremental effect of increasing case volume took into account the variables of patient age, sex, and comorbidities measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

The analysis also showed that, during this 2-year period, the average number of endovascular thrombectomy cases among Medicare patients was just under 21 cases per center, with a range of 1-160 cases; for individual proceduralists, the average was just under 5 cases, with a range of 1-82 cases.

The 19 case/year volume minimum that the analysis identified for an individual proceduralist to have a statistically significant higher rate of good outcomes, compared with lower-volume proceduralists, came close to the 15 cases/year minimum set by the Joint Commission in 2019 for individual operators at centers seeking accreditation from the Joint Commission as either a Thrombectomy-Capable Stroke Center or a Comprehensive Stroke Center. The CMS has not yet set thrombectomy case-load requirements for centers or operators to qualify for Medicare reimbursements, although CMS has set such standards for other endovascular procedures, such as transcatheter aortic valve replacement. When setting such standards, CMS has cited its need to balance the better outcomes produced by higher-volume centers against a societal interest in facilitating access to vital medical services, a balance that Dr. Stein also highlighted in her talk.

“We want to optimize access as well as outcomes for every patient,” she said. “These data support certification volume standards,” but they are “in no way an argument for limiting access based on volume.”

Dr. Stein had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein LK et al. ISC 2020, Abstract LB11.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

TNK dose in large-vessel stroke: 0.25 mg/kg is sufficient

A new study suggests that the 0.25-mg/kg dose of the thrombolytic tenecteplase (TNK) is just as good at facilitating reperfusion of the blocked artery in patients with ischemic large-vessel stroke prior to planned thrombectomy as the higher 0.4-mg/kg dose.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was presented today at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020 in Los Angeles and was published online simultaneously (JAMA. 2020 Feb 20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1511).

“We found the 0.4-mg/kg dose was no better than 0.25 mg/kg. There was absolutely no perceptible difference, so it appears that 0.25 mg/kg is enough,” lead investigator Bruce Campbell, MBBS, PhD, said in an interview.

“Our study was conducted in patients with large-vessel occlusions heading for thrombectomy, but I think the results can be extrapolated to patients with smaller occlusions too,” he added.

The study also showed that one-fifth of patients given tenecteplase experienced reperfusion before thrombectomy was performed. The percentage rose to one-third among patients from rural areas, whose longer times in transport led to an increase in the time between thrombolysis and thrombectomy.

“I think these data are as good as we’re going to get on the optimal dose of TNK. Our endpoint was reperfusion rates – a good, solid biological marker of benefit – but if a difference in clinical outcomes is wanted, that would take a trial of several thousand patients, which is never likely to be done,” said Dr. Campbell, who is from the Department of Neurology at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

The researchers note that tenecteplase has a practical advantage over alteplase in that it is given as a bolus injection, whereas alteplase is given as bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion.

Results from the first EXTEND-IA TNK study suggested that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg produced higher reperfusion rates than alteplase (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1573-82). However, the larger NOR-TEST study found no difference in efficacy or safety between a 0.4-mg/kg dose of tenecteplase and alteplase in patients with mild stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017 Oct;16[10]:781-8).

TNK use in stroke varies around the world. The drug is not licensed for use in stroke anywhere, which Dr. Campbell attributes to a lack of incentive for the manufacturer, Genentech/Boehringer Ingelheim. That company also markets alteplase, the main thrombolytic used in stroke.

But many countries have now included TNK in their stroke guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted. “This has only recently occurred in the U.S., where it has a 2b recommendation, and the dose recommendations are somewhat confusing, advocating 0.25 mg/kg in large-vessel occlusions [as was used in the first EXTEND IA study] and 0.4 mg/kg in non–large vessel occlusions [from the NOR-TEST trial].

“This makes no biological sense whatsoever, recommending a higher dose for smaller occlusions, but that is just a literal translation of the design of the two major studies. I’m hoping our current results will help clarify the dosage issue and that might encourage more use of TNK altogether,” he commented.

For the current study, conducted in Australia and New Zealand, 300 patients who had experienced ischemic large-vessel stroke within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and who were scheduled for endovascular thrombectomy were randomly assigned to receive open-label thrombolysis with tenecteplase 0.4 mg/kg or 0.25 mg/kg.

The primary outcome, reperfusion of greater than 50% of the involved ischemic territory prior to thrombectomy, occurred in 19.3% of both groups. There was also no difference in any of the functional-outcome secondary endpoints or all-cause mortality between the two doses.

“While we didn’t find any extra benefit of the 0.4-mg/kg dose over the 0.25-mg/kg dose, we also didn’t find any extra harm, and this gives us reassurance in the emergency situation if the weight of the patient is overestimated; then we have a window of safety,” Dr. Campbell commented. “While there was a nonsignificant numerical increase in intracranial hemorrhage in the 0.4-mg/kg group, the excess bleeds were caused by puncturing of the vessels during thrombectomy, so I don’t think we can blame the TNK dose for that.

Better reperfusion than with alteplase?

Noting that the original EXTEND-IA TNK study showed higher reperfusion rates with tenecteplase vs alteplase and a trend toward better outcomes on the mRS scale, Campbell reported that a pooled analysis of the TNK results from the current study with those from the first study confirmed these findings.

“We found a doubling in the rate of reperfusion with TNK vs. alteplase, and the [modified Rankin Scale] shift analysis remained positive,” he said.

“I think we say with confidence that TNK is at least as good as alteplase and probably better, but further studies comparing the two agents are ongoing,” he added.

Of note, for the 41 patients from rural areas in the current study, in whom the time from thrombolysis to thrombectomy was longer (152 min vs. 41 min for patients from urban areas), reperfusion rates were higher (34% vs 17%), and there was no difference in dosage between the two groups.

Commenting on these latest results in an interview, Nicola Logallo, MD, of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, who was part of the NOR-TEST trial, said: “There is some evidence supporting the use of TNK 0.4 mg/kg in mild stroke patients, based mainly on the results from the NOR-TEST trial, and the use of TNK 0.25 mg/kg in patients undergoing thrombectomy, based on Dr. Campbell’s previous EXTEND-TNK trial. Dr. Campbell’s new study confirms that probably the higher dose of TNK does not add any advantages in terms of clinical outcome.”

Hemorrhagic complications appear to be similar in the two groups, Dr. Logallo said. “Overall, the 0.25-mg/kg TNK dose could therefore be considered as the most convenient and sensible, at least in patients undergoing thrombectomy. When it comes to the remaining stroke patients receiving thrombolysis, it remains unclear which is the best dose, but studies such as TASTE, NOR-TEST 2, AcT, and ATTEST-2 will hopefully answer this question within the next years.”

Also commenting on the study, Michael Hill, MD, professor of neurology at University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said the results “confirm that a good proportion of patients given TNK reperfuse before the angiogram and clarifies the dose. This is useful information.”

Dr. Hill said TNK is used routinely in some countries – mainly in Australia and Norway, where the studies have been conducted – but there is now a movement toward use of TNK in North America, too.

“Studies so far suggest that it could be more effective than alteplase, and as it is more fibrin specific, it could be safer. It is also easier to give with a bolus dose, but perhaps the biggest driver might be that it is cheaper than alteplase. Momentum is building, and many leading investigators are now conducting new studies with TNK with several more studies coming out in the next year or so,” Dr. Hill added.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Campbell reports receiving grants from both institutions during the conduct of the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study suggests that the 0.25-mg/kg dose of the thrombolytic tenecteplase (TNK) is just as good at facilitating reperfusion of the blocked artery in patients with ischemic large-vessel stroke prior to planned thrombectomy as the higher 0.4-mg/kg dose.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was presented today at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020 in Los Angeles and was published online simultaneously (JAMA. 2020 Feb 20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1511).

“We found the 0.4-mg/kg dose was no better than 0.25 mg/kg. There was absolutely no perceptible difference, so it appears that 0.25 mg/kg is enough,” lead investigator Bruce Campbell, MBBS, PhD, said in an interview.

“Our study was conducted in patients with large-vessel occlusions heading for thrombectomy, but I think the results can be extrapolated to patients with smaller occlusions too,” he added.

The study also showed that one-fifth of patients given tenecteplase experienced reperfusion before thrombectomy was performed. The percentage rose to one-third among patients from rural areas, whose longer times in transport led to an increase in the time between thrombolysis and thrombectomy.

“I think these data are as good as we’re going to get on the optimal dose of TNK. Our endpoint was reperfusion rates – a good, solid biological marker of benefit – but if a difference in clinical outcomes is wanted, that would take a trial of several thousand patients, which is never likely to be done,” said Dr. Campbell, who is from the Department of Neurology at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

The researchers note that tenecteplase has a practical advantage over alteplase in that it is given as a bolus injection, whereas alteplase is given as bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion.

Results from the first EXTEND-IA TNK study suggested that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg produced higher reperfusion rates than alteplase (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1573-82). However, the larger NOR-TEST study found no difference in efficacy or safety between a 0.4-mg/kg dose of tenecteplase and alteplase in patients with mild stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017 Oct;16[10]:781-8).

TNK use in stroke varies around the world. The drug is not licensed for use in stroke anywhere, which Dr. Campbell attributes to a lack of incentive for the manufacturer, Genentech/Boehringer Ingelheim. That company also markets alteplase, the main thrombolytic used in stroke.

But many countries have now included TNK in their stroke guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted. “This has only recently occurred in the U.S., where it has a 2b recommendation, and the dose recommendations are somewhat confusing, advocating 0.25 mg/kg in large-vessel occlusions [as was used in the first EXTEND IA study] and 0.4 mg/kg in non–large vessel occlusions [from the NOR-TEST trial].

“This makes no biological sense whatsoever, recommending a higher dose for smaller occlusions, but that is just a literal translation of the design of the two major studies. I’m hoping our current results will help clarify the dosage issue and that might encourage more use of TNK altogether,” he commented.

For the current study, conducted in Australia and New Zealand, 300 patients who had experienced ischemic large-vessel stroke within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and who were scheduled for endovascular thrombectomy were randomly assigned to receive open-label thrombolysis with tenecteplase 0.4 mg/kg or 0.25 mg/kg.

The primary outcome, reperfusion of greater than 50% of the involved ischemic territory prior to thrombectomy, occurred in 19.3% of both groups. There was also no difference in any of the functional-outcome secondary endpoints or all-cause mortality between the two doses.

“While we didn’t find any extra benefit of the 0.4-mg/kg dose over the 0.25-mg/kg dose, we also didn’t find any extra harm, and this gives us reassurance in the emergency situation if the weight of the patient is overestimated; then we have a window of safety,” Dr. Campbell commented. “While there was a nonsignificant numerical increase in intracranial hemorrhage in the 0.4-mg/kg group, the excess bleeds were caused by puncturing of the vessels during thrombectomy, so I don’t think we can blame the TNK dose for that.

Better reperfusion than with alteplase?

Noting that the original EXTEND-IA TNK study showed higher reperfusion rates with tenecteplase vs alteplase and a trend toward better outcomes on the mRS scale, Campbell reported that a pooled analysis of the TNK results from the current study with those from the first study confirmed these findings.

“We found a doubling in the rate of reperfusion with TNK vs. alteplase, and the [modified Rankin Scale] shift analysis remained positive,” he said.

“I think we say with confidence that TNK is at least as good as alteplase and probably better, but further studies comparing the two agents are ongoing,” he added.

Of note, for the 41 patients from rural areas in the current study, in whom the time from thrombolysis to thrombectomy was longer (152 min vs. 41 min for patients from urban areas), reperfusion rates were higher (34% vs 17%), and there was no difference in dosage between the two groups.

Commenting on these latest results in an interview, Nicola Logallo, MD, of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, who was part of the NOR-TEST trial, said: “There is some evidence supporting the use of TNK 0.4 mg/kg in mild stroke patients, based mainly on the results from the NOR-TEST trial, and the use of TNK 0.25 mg/kg in patients undergoing thrombectomy, based on Dr. Campbell’s previous EXTEND-TNK trial. Dr. Campbell’s new study confirms that probably the higher dose of TNK does not add any advantages in terms of clinical outcome.”

Hemorrhagic complications appear to be similar in the two groups, Dr. Logallo said. “Overall, the 0.25-mg/kg TNK dose could therefore be considered as the most convenient and sensible, at least in patients undergoing thrombectomy. When it comes to the remaining stroke patients receiving thrombolysis, it remains unclear which is the best dose, but studies such as TASTE, NOR-TEST 2, AcT, and ATTEST-2 will hopefully answer this question within the next years.”

Also commenting on the study, Michael Hill, MD, professor of neurology at University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said the results “confirm that a good proportion of patients given TNK reperfuse before the angiogram and clarifies the dose. This is useful information.”

Dr. Hill said TNK is used routinely in some countries – mainly in Australia and Norway, where the studies have been conducted – but there is now a movement toward use of TNK in North America, too.

“Studies so far suggest that it could be more effective than alteplase, and as it is more fibrin specific, it could be safer. It is also easier to give with a bolus dose, but perhaps the biggest driver might be that it is cheaper than alteplase. Momentum is building, and many leading investigators are now conducting new studies with TNK with several more studies coming out in the next year or so,” Dr. Hill added.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Campbell reports receiving grants from both institutions during the conduct of the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study suggests that the 0.25-mg/kg dose of the thrombolytic tenecteplase (TNK) is just as good at facilitating reperfusion of the blocked artery in patients with ischemic large-vessel stroke prior to planned thrombectomy as the higher 0.4-mg/kg dose.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was presented today at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference (ISC) 2020 in Los Angeles and was published online simultaneously (JAMA. 2020 Feb 20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1511).

“We found the 0.4-mg/kg dose was no better than 0.25 mg/kg. There was absolutely no perceptible difference, so it appears that 0.25 mg/kg is enough,” lead investigator Bruce Campbell, MBBS, PhD, said in an interview.

“Our study was conducted in patients with large-vessel occlusions heading for thrombectomy, but I think the results can be extrapolated to patients with smaller occlusions too,” he added.

The study also showed that one-fifth of patients given tenecteplase experienced reperfusion before thrombectomy was performed. The percentage rose to one-third among patients from rural areas, whose longer times in transport led to an increase in the time between thrombolysis and thrombectomy.

“I think these data are as good as we’re going to get on the optimal dose of TNK. Our endpoint was reperfusion rates – a good, solid biological marker of benefit – but if a difference in clinical outcomes is wanted, that would take a trial of several thousand patients, which is never likely to be done,” said Dr. Campbell, who is from the Department of Neurology at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

The researchers note that tenecteplase has a practical advantage over alteplase in that it is given as a bolus injection, whereas alteplase is given as bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion.

Results from the first EXTEND-IA TNK study suggested that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg produced higher reperfusion rates than alteplase (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1573-82). However, the larger NOR-TEST study found no difference in efficacy or safety between a 0.4-mg/kg dose of tenecteplase and alteplase in patients with mild stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017 Oct;16[10]:781-8).

TNK use in stroke varies around the world. The drug is not licensed for use in stroke anywhere, which Dr. Campbell attributes to a lack of incentive for the manufacturer, Genentech/Boehringer Ingelheim. That company also markets alteplase, the main thrombolytic used in stroke.

But many countries have now included TNK in their stroke guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted. “This has only recently occurred in the U.S., where it has a 2b recommendation, and the dose recommendations are somewhat confusing, advocating 0.25 mg/kg in large-vessel occlusions [as was used in the first EXTEND IA study] and 0.4 mg/kg in non–large vessel occlusions [from the NOR-TEST trial].

“This makes no biological sense whatsoever, recommending a higher dose for smaller occlusions, but that is just a literal translation of the design of the two major studies. I’m hoping our current results will help clarify the dosage issue and that might encourage more use of TNK altogether,” he commented.

For the current study, conducted in Australia and New Zealand, 300 patients who had experienced ischemic large-vessel stroke within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and who were scheduled for endovascular thrombectomy were randomly assigned to receive open-label thrombolysis with tenecteplase 0.4 mg/kg or 0.25 mg/kg.

The primary outcome, reperfusion of greater than 50% of the involved ischemic territory prior to thrombectomy, occurred in 19.3% of both groups. There was also no difference in any of the functional-outcome secondary endpoints or all-cause mortality between the two doses.

“While we didn’t find any extra benefit of the 0.4-mg/kg dose over the 0.25-mg/kg dose, we also didn’t find any extra harm, and this gives us reassurance in the emergency situation if the weight of the patient is overestimated; then we have a window of safety,” Dr. Campbell commented. “While there was a nonsignificant numerical increase in intracranial hemorrhage in the 0.4-mg/kg group, the excess bleeds were caused by puncturing of the vessels during thrombectomy, so I don’t think we can blame the TNK dose for that.

Better reperfusion than with alteplase?

Noting that the original EXTEND-IA TNK study showed higher reperfusion rates with tenecteplase vs alteplase and a trend toward better outcomes on the mRS scale, Campbell reported that a pooled analysis of the TNK results from the current study with those from the first study confirmed these findings.

“We found a doubling in the rate of reperfusion with TNK vs. alteplase, and the [modified Rankin Scale] shift analysis remained positive,” he said.

“I think we say with confidence that TNK is at least as good as alteplase and probably better, but further studies comparing the two agents are ongoing,” he added.

Of note, for the 41 patients from rural areas in the current study, in whom the time from thrombolysis to thrombectomy was longer (152 min vs. 41 min for patients from urban areas), reperfusion rates were higher (34% vs 17%), and there was no difference in dosage between the two groups.

Commenting on these latest results in an interview, Nicola Logallo, MD, of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, who was part of the NOR-TEST trial, said: “There is some evidence supporting the use of TNK 0.4 mg/kg in mild stroke patients, based mainly on the results from the NOR-TEST trial, and the use of TNK 0.25 mg/kg in patients undergoing thrombectomy, based on Dr. Campbell’s previous EXTEND-TNK trial. Dr. Campbell’s new study confirms that probably the higher dose of TNK does not add any advantages in terms of clinical outcome.”

Hemorrhagic complications appear to be similar in the two groups, Dr. Logallo said. “Overall, the 0.25-mg/kg TNK dose could therefore be considered as the most convenient and sensible, at least in patients undergoing thrombectomy. When it comes to the remaining stroke patients receiving thrombolysis, it remains unclear which is the best dose, but studies such as TASTE, NOR-TEST 2, AcT, and ATTEST-2 will hopefully answer this question within the next years.”

Also commenting on the study, Michael Hill, MD, professor of neurology at University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said the results “confirm that a good proportion of patients given TNK reperfuse before the angiogram and clarifies the dose. This is useful information.”

Dr. Hill said TNK is used routinely in some countries – mainly in Australia and Norway, where the studies have been conducted – but there is now a movement toward use of TNK in North America, too.

“Studies so far suggest that it could be more effective than alteplase, and as it is more fibrin specific, it could be safer. It is also easier to give with a bolus dose, but perhaps the biggest driver might be that it is cheaper than alteplase. Momentum is building, and many leading investigators are now conducting new studies with TNK with several more studies coming out in the next year or so,” Dr. Hill added.

The EXTEND-IA TNK Part 2 trial was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Campbell reports receiving grants from both institutions during the conduct of the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ARCADIA: Predicting risk of atrial cardiopathy poststroke

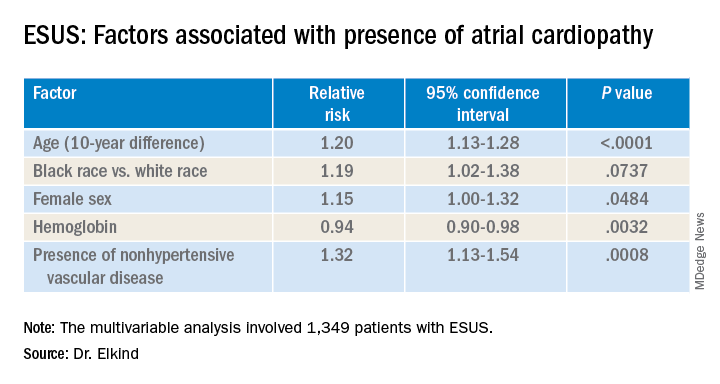

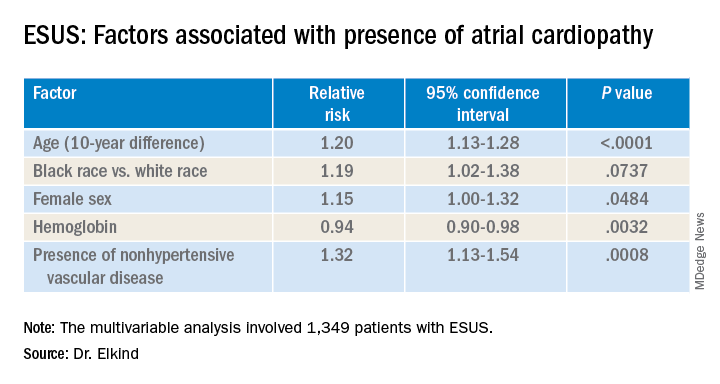

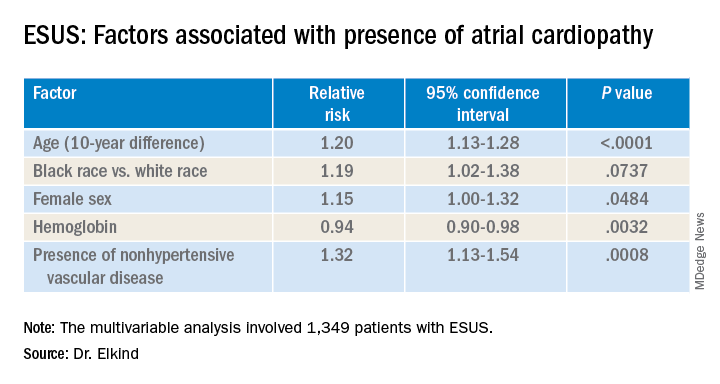

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.