User login

Progress of the AGA Equity Project

In May 2022, the Digestive Disease Week (DDW) conference was held in person again for the first time in 3 years. Two years prior in July 2020 AGA launched the Equity Project, a six-point strategic plan to achieve equity and eradicate health disparities in digestive diseases.

President John Inadomi elected to focus his AGA Presidential Plenary session on updates in gastrointestinal and hepatic health disparities, and opened with a powerful testimony on his personal experiences encountering racism, and recognizing the need to translate spoken intentions into action.

This served as the perfect segue to the second plenary presentation in which an update was given on the progress of the Equity Project by co-chairs Byron Cryer, MD, and Sandra Quezada, MD, MS. Dr. Cryer described the vision of the Equity Project, including: a just world, free of inequities in access and health care delivery; state-of-the-art and well-funded research of multicultural populations; a diverse physician and scientist workforce and leadership; recognition of achievements of people of color; membership and staff committed to self-awareness and eliminating unconscious bias; and an engaged, large, diverse, vocal, and culturally- and socially aware early career membership.

Concrete action items were identified by a coalition of AGA members with diverse representation across specialties, practice settings, and identities. AGA staff and constituency programs have been critical in the execution of each action item. Key performance indicators were selected to gauge progress and hold the organization accountable in implementation of project tactics. These metrics demonstrate that the first 2 years of the Equity Project have been very productive. Salient accomplishments include three congressional briefings on health disparities topics, increased education and dialogue on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) through podcasts, career development workshops and DDW sessions, fundraising of over $300,000 to support health disparities research, dedicated DEI sections and section editors for Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and the creation of a guide for GI fellowship program directors to promote equity and mitigate bias in the fellowship selection process.

Although the Equity Project is entering its third and final implementation year, the spirit and values of the Equity Project will live on. Excellence in equity requires ongoing, focused dedication – AGA is committed to ensuring that equity, diversity, and inclusion are inherently embedded through the fabric of the organization, and continuously integrated and assessed in all of the organization’s future strategic initiatives.

Dr. Quezada is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She reports being on the People of Color Advisory Board for Janssen. Dr. Cryer is chief of internal medicine and the Ralph Tompsett Endowed Chair in Medicine at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M School of Medicine. He has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during the AGA Presidential Plenary at DDW 2022.

In May 2022, the Digestive Disease Week (DDW) conference was held in person again for the first time in 3 years. Two years prior in July 2020 AGA launched the Equity Project, a six-point strategic plan to achieve equity and eradicate health disparities in digestive diseases.

President John Inadomi elected to focus his AGA Presidential Plenary session on updates in gastrointestinal and hepatic health disparities, and opened with a powerful testimony on his personal experiences encountering racism, and recognizing the need to translate spoken intentions into action.

This served as the perfect segue to the second plenary presentation in which an update was given on the progress of the Equity Project by co-chairs Byron Cryer, MD, and Sandra Quezada, MD, MS. Dr. Cryer described the vision of the Equity Project, including: a just world, free of inequities in access and health care delivery; state-of-the-art and well-funded research of multicultural populations; a diverse physician and scientist workforce and leadership; recognition of achievements of people of color; membership and staff committed to self-awareness and eliminating unconscious bias; and an engaged, large, diverse, vocal, and culturally- and socially aware early career membership.

Concrete action items were identified by a coalition of AGA members with diverse representation across specialties, practice settings, and identities. AGA staff and constituency programs have been critical in the execution of each action item. Key performance indicators were selected to gauge progress and hold the organization accountable in implementation of project tactics. These metrics demonstrate that the first 2 years of the Equity Project have been very productive. Salient accomplishments include three congressional briefings on health disparities topics, increased education and dialogue on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) through podcasts, career development workshops and DDW sessions, fundraising of over $300,000 to support health disparities research, dedicated DEI sections and section editors for Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and the creation of a guide for GI fellowship program directors to promote equity and mitigate bias in the fellowship selection process.

Although the Equity Project is entering its third and final implementation year, the spirit and values of the Equity Project will live on. Excellence in equity requires ongoing, focused dedication – AGA is committed to ensuring that equity, diversity, and inclusion are inherently embedded through the fabric of the organization, and continuously integrated and assessed in all of the organization’s future strategic initiatives.

Dr. Quezada is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She reports being on the People of Color Advisory Board for Janssen. Dr. Cryer is chief of internal medicine and the Ralph Tompsett Endowed Chair in Medicine at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M School of Medicine. He has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during the AGA Presidential Plenary at DDW 2022.

In May 2022, the Digestive Disease Week (DDW) conference was held in person again for the first time in 3 years. Two years prior in July 2020 AGA launched the Equity Project, a six-point strategic plan to achieve equity and eradicate health disparities in digestive diseases.

President John Inadomi elected to focus his AGA Presidential Plenary session on updates in gastrointestinal and hepatic health disparities, and opened with a powerful testimony on his personal experiences encountering racism, and recognizing the need to translate spoken intentions into action.

This served as the perfect segue to the second plenary presentation in which an update was given on the progress of the Equity Project by co-chairs Byron Cryer, MD, and Sandra Quezada, MD, MS. Dr. Cryer described the vision of the Equity Project, including: a just world, free of inequities in access and health care delivery; state-of-the-art and well-funded research of multicultural populations; a diverse physician and scientist workforce and leadership; recognition of achievements of people of color; membership and staff committed to self-awareness and eliminating unconscious bias; and an engaged, large, diverse, vocal, and culturally- and socially aware early career membership.

Concrete action items were identified by a coalition of AGA members with diverse representation across specialties, practice settings, and identities. AGA staff and constituency programs have been critical in the execution of each action item. Key performance indicators were selected to gauge progress and hold the organization accountable in implementation of project tactics. These metrics demonstrate that the first 2 years of the Equity Project have been very productive. Salient accomplishments include three congressional briefings on health disparities topics, increased education and dialogue on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) through podcasts, career development workshops and DDW sessions, fundraising of over $300,000 to support health disparities research, dedicated DEI sections and section editors for Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and the creation of a guide for GI fellowship program directors to promote equity and mitigate bias in the fellowship selection process.

Although the Equity Project is entering its third and final implementation year, the spirit and values of the Equity Project will live on. Excellence in equity requires ongoing, focused dedication – AGA is committed to ensuring that equity, diversity, and inclusion are inherently embedded through the fabric of the organization, and continuously integrated and assessed in all of the organization’s future strategic initiatives.

Dr. Quezada is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She reports being on the People of Color Advisory Board for Janssen. Dr. Cryer is chief of internal medicine and the Ralph Tompsett Endowed Chair in Medicine at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M School of Medicine. He has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during the AGA Presidential Plenary at DDW 2022.

Updates in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) are characterized by GI signs or symptoms occurring along with tissue eosinophilia. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is the more commonly recognized EGID as endoscopic and histopathologic diagnostic criteria have long been established. Because of a lack of consensus on biopsy protocols, poorly understood histopathologic diagnostic criteria, and vague, nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints, patients with non-EoE EGIDs go unrecognized for years. Because of this, there is increasing emphasis on better defining rare, distal eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis, enteritis, and colitis).

EGID nomenclature was standardized in 2022 in part to minimize vague terminology (i.e., eosinophilic gastroenteritis) and to provide more specific information about the location of eosinophilic disease. The 2022 nomenclature suggest that EGID be used as the umbrella term for all GI luminal eosinophilia (without a known cause) but with emphasis on the site of specific eosinophilic involvement (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic gastritis and colitis). Importantly, there is much work to be done to adequately identify patients suffering from EGIDs. Symptoms are variable, ranging from abdominal pain, bloating, and nausea seen in proximal disease to loose stools and hematochezia in more distal involvement. Signs of disease, such as iron or other nutrient deficiencies and protein loss, may also occur. Endoscopic findings can vary from erythema, granularity, erosions, ulcerations, and blunting to even normal-appearing tissue. In eosinophilic gastritis, Ikuo Hirano, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that increasing endoscopic inflammatory findings in the stomach correlate with assessment of disease severity. Regardless of endoscopic findings, numerous biopsies are needed for the diagnosis of EGIDs because, as already established in EoE, eosinophil involvement is patchy. Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, found that a minimum of four biopsies each in the gastric antrum, gastric body, and small bowel are needed to detect disease. Optimal biopsy patterns have not yet been determined for eosinophilic ileitis or colitis.

Despite these advances, there is more work to be performed. Although these disease states are termed “eosinophilic,” the immunopathology driving these diseases is multifactorial, involving lymphocytes and mast cells and creating different phenotypes of disease in a similar fashion to inflammatory bowel disease. Current therapies being studied include eosinophil-depleting medications along with others targeting T2 immune pathways. Patients may need multiple therapeutic options, and personalized medicine will soon play a larger role in defining treatments. For now, researchers are fervently working on improved methods to identify, phenotype, and treat these morbid disorders.

Dr. Peterson is associate professor of gastroenterology at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City. She has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) are characterized by GI signs or symptoms occurring along with tissue eosinophilia. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is the more commonly recognized EGID as endoscopic and histopathologic diagnostic criteria have long been established. Because of a lack of consensus on biopsy protocols, poorly understood histopathologic diagnostic criteria, and vague, nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints, patients with non-EoE EGIDs go unrecognized for years. Because of this, there is increasing emphasis on better defining rare, distal eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis, enteritis, and colitis).

EGID nomenclature was standardized in 2022 in part to minimize vague terminology (i.e., eosinophilic gastroenteritis) and to provide more specific information about the location of eosinophilic disease. The 2022 nomenclature suggest that EGID be used as the umbrella term for all GI luminal eosinophilia (without a known cause) but with emphasis on the site of specific eosinophilic involvement (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic gastritis and colitis). Importantly, there is much work to be done to adequately identify patients suffering from EGIDs. Symptoms are variable, ranging from abdominal pain, bloating, and nausea seen in proximal disease to loose stools and hematochezia in more distal involvement. Signs of disease, such as iron or other nutrient deficiencies and protein loss, may also occur. Endoscopic findings can vary from erythema, granularity, erosions, ulcerations, and blunting to even normal-appearing tissue. In eosinophilic gastritis, Ikuo Hirano, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that increasing endoscopic inflammatory findings in the stomach correlate with assessment of disease severity. Regardless of endoscopic findings, numerous biopsies are needed for the diagnosis of EGIDs because, as already established in EoE, eosinophil involvement is patchy. Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, found that a minimum of four biopsies each in the gastric antrum, gastric body, and small bowel are needed to detect disease. Optimal biopsy patterns have not yet been determined for eosinophilic ileitis or colitis.

Despite these advances, there is more work to be performed. Although these disease states are termed “eosinophilic,” the immunopathology driving these diseases is multifactorial, involving lymphocytes and mast cells and creating different phenotypes of disease in a similar fashion to inflammatory bowel disease. Current therapies being studied include eosinophil-depleting medications along with others targeting T2 immune pathways. Patients may need multiple therapeutic options, and personalized medicine will soon play a larger role in defining treatments. For now, researchers are fervently working on improved methods to identify, phenotype, and treat these morbid disorders.

Dr. Peterson is associate professor of gastroenterology at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City. She has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) are characterized by GI signs or symptoms occurring along with tissue eosinophilia. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is the more commonly recognized EGID as endoscopic and histopathologic diagnostic criteria have long been established. Because of a lack of consensus on biopsy protocols, poorly understood histopathologic diagnostic criteria, and vague, nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints, patients with non-EoE EGIDs go unrecognized for years. Because of this, there is increasing emphasis on better defining rare, distal eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis, enteritis, and colitis).

EGID nomenclature was standardized in 2022 in part to minimize vague terminology (i.e., eosinophilic gastroenteritis) and to provide more specific information about the location of eosinophilic disease. The 2022 nomenclature suggest that EGID be used as the umbrella term for all GI luminal eosinophilia (without a known cause) but with emphasis on the site of specific eosinophilic involvement (i.e., eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic gastritis and colitis). Importantly, there is much work to be done to adequately identify patients suffering from EGIDs. Symptoms are variable, ranging from abdominal pain, bloating, and nausea seen in proximal disease to loose stools and hematochezia in more distal involvement. Signs of disease, such as iron or other nutrient deficiencies and protein loss, may also occur. Endoscopic findings can vary from erythema, granularity, erosions, ulcerations, and blunting to even normal-appearing tissue. In eosinophilic gastritis, Ikuo Hirano, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that increasing endoscopic inflammatory findings in the stomach correlate with assessment of disease severity. Regardless of endoscopic findings, numerous biopsies are needed for the diagnosis of EGIDs because, as already established in EoE, eosinophil involvement is patchy. Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, found that a minimum of four biopsies each in the gastric antrum, gastric body, and small bowel are needed to detect disease. Optimal biopsy patterns have not yet been determined for eosinophilic ileitis or colitis.

Despite these advances, there is more work to be performed. Although these disease states are termed “eosinophilic,” the immunopathology driving these diseases is multifactorial, involving lymphocytes and mast cells and creating different phenotypes of disease in a similar fashion to inflammatory bowel disease. Current therapies being studied include eosinophil-depleting medications along with others targeting T2 immune pathways. Patients may need multiple therapeutic options, and personalized medicine will soon play a larger role in defining treatments. For now, researchers are fervently working on improved methods to identify, phenotype, and treat these morbid disorders.

Dr. Peterson is associate professor of gastroenterology at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City. She has no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Understanding GERD phenotypes

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

AT DDW 2022

EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PT-GBD) is the most common, nonoperative method for gallbladder decompression in patients unfit for cholecystectomy. However, drain-related complications (20%-75%), including tube changes, dyscosmesis, discomfort, and recurrent cholecystitis (up to 15%), limit its long-term use. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ET-GBD) and now, endoscopic ultrasound–guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD), have emerged as options.

ET-GBD is performed at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) by cannulating the cystic duct, allowing placement of a pigtail plastic stent into the gallbladder. However, obstructing pathology (stone, stricture, metal stent or mass) may result in lower technical and clinical success when compared with EUS-GBD (84% vs. 98% and 91% vs. 97%, respectively). Furthermore, it does not allow for treatment of gallstones, and may require stent exchanges.

EUS-GBD involves placing a stent from the duodenum/stomach into the gallbladder under EUS guidance. Initial use of pigtail plastic stents and biliary self-expandable metal stents were not ideal, because of their risk of leakage, longer length (contralateral wall injury, occlusions), and migration (lack of flanges). Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) overcame these limitations because of their short length and large flanges, and their large diameters (up to 20 mm) aid passage of gallstones or cholecystoscopy. Several case series and comparative trials have been published on EUS-GBD including a randomized prospective trial of EUS-GBD vs. PT-GBD demonstrating its superiority. Adverse events are uncommon and include misdeployments, bleeding, perforation, bile leaks, occlusion (commonly with food, prompting some endoscopists to place pigtails stents through the LAMS and avoiding the stomach as a target), and migration.

EUS-GBD should be avoided in patients who have a perforated gallbladder, have large volume ascites, or are too sick to tolerate anesthesia. Although there are patients who have subsequently undergone cholecystectomy post EUS-GBD, a discussion with one’s surgeon must be had prior to choosing this approach over ET-GBD.

In conclusion, determining the ideal method for endoscopic GBD in high-surgical-risk patients requires consideration of comorbidities, anatomy (GB position, cystic duct characteristics), presence of ascites, future surgical candidacy, and local expertise. ET-GBD should be prioritized for patients requiring ERCP for alternative reasons, large volume ascites, and as a bridge to cholecystectomy. Conversely, EUS-GBD is preferred with indwelling metal biliary stents covering the cystic duct and/or high-volume cholelithiasis. LAMS can be left long term; however, in patients willing to undergo an additional procedure, exchanging the LAMS for plastic stents can be undertaken at 4-6 weeks. Ultimately, more randomized and prospective data are needed to compare ET- and EUS-GBD outcomes, including a formal cost analysis.

Dr. Irani is with Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. He reports being a consultant for Boston Scientific and Gore, as well as remittance to his clinic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PT-GBD) is the most common, nonoperative method for gallbladder decompression in patients unfit for cholecystectomy. However, drain-related complications (20%-75%), including tube changes, dyscosmesis, discomfort, and recurrent cholecystitis (up to 15%), limit its long-term use. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ET-GBD) and now, endoscopic ultrasound–guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD), have emerged as options.

ET-GBD is performed at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) by cannulating the cystic duct, allowing placement of a pigtail plastic stent into the gallbladder. However, obstructing pathology (stone, stricture, metal stent or mass) may result in lower technical and clinical success when compared with EUS-GBD (84% vs. 98% and 91% vs. 97%, respectively). Furthermore, it does not allow for treatment of gallstones, and may require stent exchanges.

EUS-GBD involves placing a stent from the duodenum/stomach into the gallbladder under EUS guidance. Initial use of pigtail plastic stents and biliary self-expandable metal stents were not ideal, because of their risk of leakage, longer length (contralateral wall injury, occlusions), and migration (lack of flanges). Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) overcame these limitations because of their short length and large flanges, and their large diameters (up to 20 mm) aid passage of gallstones or cholecystoscopy. Several case series and comparative trials have been published on EUS-GBD including a randomized prospective trial of EUS-GBD vs. PT-GBD demonstrating its superiority. Adverse events are uncommon and include misdeployments, bleeding, perforation, bile leaks, occlusion (commonly with food, prompting some endoscopists to place pigtails stents through the LAMS and avoiding the stomach as a target), and migration.

EUS-GBD should be avoided in patients who have a perforated gallbladder, have large volume ascites, or are too sick to tolerate anesthesia. Although there are patients who have subsequently undergone cholecystectomy post EUS-GBD, a discussion with one’s surgeon must be had prior to choosing this approach over ET-GBD.

In conclusion, determining the ideal method for endoscopic GBD in high-surgical-risk patients requires consideration of comorbidities, anatomy (GB position, cystic duct characteristics), presence of ascites, future surgical candidacy, and local expertise. ET-GBD should be prioritized for patients requiring ERCP for alternative reasons, large volume ascites, and as a bridge to cholecystectomy. Conversely, EUS-GBD is preferred with indwelling metal biliary stents covering the cystic duct and/or high-volume cholelithiasis. LAMS can be left long term; however, in patients willing to undergo an additional procedure, exchanging the LAMS for plastic stents can be undertaken at 4-6 weeks. Ultimately, more randomized and prospective data are needed to compare ET- and EUS-GBD outcomes, including a formal cost analysis.

Dr. Irani is with Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. He reports being a consultant for Boston Scientific and Gore, as well as remittance to his clinic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PT-GBD) is the most common, nonoperative method for gallbladder decompression in patients unfit for cholecystectomy. However, drain-related complications (20%-75%), including tube changes, dyscosmesis, discomfort, and recurrent cholecystitis (up to 15%), limit its long-term use. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ET-GBD) and now, endoscopic ultrasound–guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD), have emerged as options.

ET-GBD is performed at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) by cannulating the cystic duct, allowing placement of a pigtail plastic stent into the gallbladder. However, obstructing pathology (stone, stricture, metal stent or mass) may result in lower technical and clinical success when compared with EUS-GBD (84% vs. 98% and 91% vs. 97%, respectively). Furthermore, it does not allow for treatment of gallstones, and may require stent exchanges.

EUS-GBD involves placing a stent from the duodenum/stomach into the gallbladder under EUS guidance. Initial use of pigtail plastic stents and biliary self-expandable metal stents were not ideal, because of their risk of leakage, longer length (contralateral wall injury, occlusions), and migration (lack of flanges). Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) overcame these limitations because of their short length and large flanges, and their large diameters (up to 20 mm) aid passage of gallstones or cholecystoscopy. Several case series and comparative trials have been published on EUS-GBD including a randomized prospective trial of EUS-GBD vs. PT-GBD demonstrating its superiority. Adverse events are uncommon and include misdeployments, bleeding, perforation, bile leaks, occlusion (commonly with food, prompting some endoscopists to place pigtails stents through the LAMS and avoiding the stomach as a target), and migration.

EUS-GBD should be avoided in patients who have a perforated gallbladder, have large volume ascites, or are too sick to tolerate anesthesia. Although there are patients who have subsequently undergone cholecystectomy post EUS-GBD, a discussion with one’s surgeon must be had prior to choosing this approach over ET-GBD.

In conclusion, determining the ideal method for endoscopic GBD in high-surgical-risk patients requires consideration of comorbidities, anatomy (GB position, cystic duct characteristics), presence of ascites, future surgical candidacy, and local expertise. ET-GBD should be prioritized for patients requiring ERCP for alternative reasons, large volume ascites, and as a bridge to cholecystectomy. Conversely, EUS-GBD is preferred with indwelling metal biliary stents covering the cystic duct and/or high-volume cholelithiasis. LAMS can be left long term; however, in patients willing to undergo an additional procedure, exchanging the LAMS for plastic stents can be undertaken at 4-6 weeks. Ultimately, more randomized and prospective data are needed to compare ET- and EUS-GBD outcomes, including a formal cost analysis.

Dr. Irani is with Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. He reports being a consultant for Boston Scientific and Gore, as well as remittance to his clinic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

AT DDW 2022

An approach to germline genetic testing in your practice

Traditionally, a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome (HCCS) was suspected in individuals with an obvious personal and/or family cancer phenotype informed by a three-generation family cancer history. Family history is still required to inform cancer risk. Documentation of age at cancer diagnosis, age of relatives’ deaths, and key intestinal and extraintestinal features of a HCCS (for example, macrocephaly, café au lait spots, polyp number, size, and histology) are requisite. Historically, Sanger sequencing was used to determine the presence of a suspected single pathogenic germline variant (PGV). If no PGV was detected, another PGV would be sought. This old “single gene/single syndrome” testing was expensive, time consuming, and inefficient, and has been supplanted by multigene cancer panel testing (MGPT). MGPT-driven low-cost, high-throughput testing has widespread insurance coverage in eligible patients. Since considerable clinical phenotypic overlap exists between HCCSs, casting a broader net for determining PGV, compared with a more limited approach, allows for greater identification of carriers of PGV as well as variants of uncertain significance.

The frequency of PGV detection by MGPT in individuals with CRC is dependent on age at diagnosis and presence of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency in the tumor. According to one review, PGVs on MGPT are detected in approximately 10% and 34% of individuals aged more than 50 and more than 35 years, respectively.1 Pearlman and colleagues performed MGPT in 450 patients with CRC less than 50 years.2 PGV were found in 8% and 83.3% of cases with MMR-proficient and -deficient tumors, respectively. Overall, 33.3% of patients did not meet genetic testing criteria for the gene in which a PGV was detected, raising the impetus to consider MGPT in all patients with CRC. The Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer and National Comprehensive Cancer Network provide guidance on who warrants PGV testing.3,4

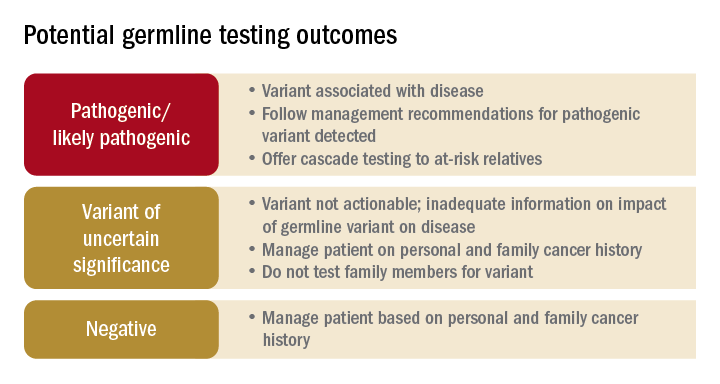

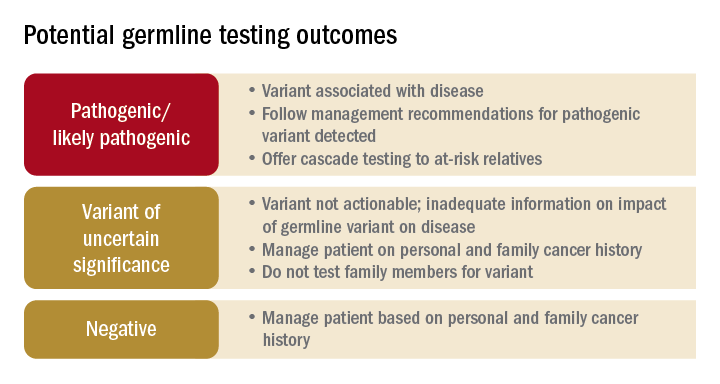

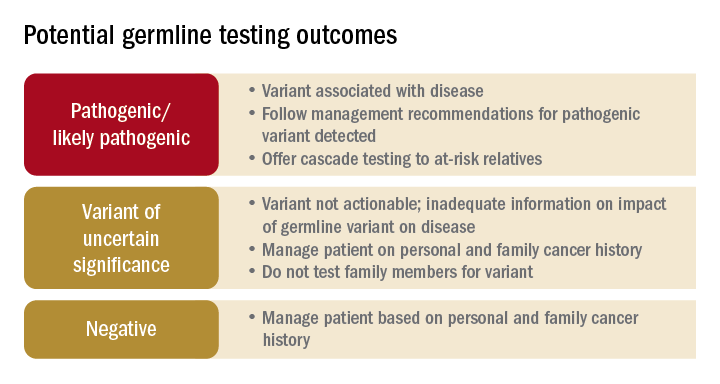

Germline testing outcomes and general approaches to patient management are provided in the graphic. HCCS are common and MGPT has broadened the identification of carriers of PGVs. In spite of advances in genetic testing technology, family history remains crucial to deploying risk-mitigation measures, regardless of the results of genetic testing.

Dr. Burke is in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic. She disclosed ties to Janssen Pharma, Emtora Biosciences, Freenome, SLA Pharma, and Ambry Genetics. Dr. Burke is a member of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline on Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Stoffel E and Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan;158(2):341-353.

2. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Apr 1;3(4):464-471.

3. Heald B et al. Fam Cancer. 2020 Jul;19(3):223-239.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 1.2022. 2022 Jun 8.

Traditionally, a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome (HCCS) was suspected in individuals with an obvious personal and/or family cancer phenotype informed by a three-generation family cancer history. Family history is still required to inform cancer risk. Documentation of age at cancer diagnosis, age of relatives’ deaths, and key intestinal and extraintestinal features of a HCCS (for example, macrocephaly, café au lait spots, polyp number, size, and histology) are requisite. Historically, Sanger sequencing was used to determine the presence of a suspected single pathogenic germline variant (PGV). If no PGV was detected, another PGV would be sought. This old “single gene/single syndrome” testing was expensive, time consuming, and inefficient, and has been supplanted by multigene cancer panel testing (MGPT). MGPT-driven low-cost, high-throughput testing has widespread insurance coverage in eligible patients. Since considerable clinical phenotypic overlap exists between HCCSs, casting a broader net for determining PGV, compared with a more limited approach, allows for greater identification of carriers of PGV as well as variants of uncertain significance.

The frequency of PGV detection by MGPT in individuals with CRC is dependent on age at diagnosis and presence of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency in the tumor. According to one review, PGVs on MGPT are detected in approximately 10% and 34% of individuals aged more than 50 and more than 35 years, respectively.1 Pearlman and colleagues performed MGPT in 450 patients with CRC less than 50 years.2 PGV were found in 8% and 83.3% of cases with MMR-proficient and -deficient tumors, respectively. Overall, 33.3% of patients did not meet genetic testing criteria for the gene in which a PGV was detected, raising the impetus to consider MGPT in all patients with CRC. The Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer and National Comprehensive Cancer Network provide guidance on who warrants PGV testing.3,4

Germline testing outcomes and general approaches to patient management are provided in the graphic. HCCS are common and MGPT has broadened the identification of carriers of PGVs. In spite of advances in genetic testing technology, family history remains crucial to deploying risk-mitigation measures, regardless of the results of genetic testing.

Dr. Burke is in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic. She disclosed ties to Janssen Pharma, Emtora Biosciences, Freenome, SLA Pharma, and Ambry Genetics. Dr. Burke is a member of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline on Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Stoffel E and Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan;158(2):341-353.

2. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Apr 1;3(4):464-471.

3. Heald B et al. Fam Cancer. 2020 Jul;19(3):223-239.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 1.2022. 2022 Jun 8.

Traditionally, a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome (HCCS) was suspected in individuals with an obvious personal and/or family cancer phenotype informed by a three-generation family cancer history. Family history is still required to inform cancer risk. Documentation of age at cancer diagnosis, age of relatives’ deaths, and key intestinal and extraintestinal features of a HCCS (for example, macrocephaly, café au lait spots, polyp number, size, and histology) are requisite. Historically, Sanger sequencing was used to determine the presence of a suspected single pathogenic germline variant (PGV). If no PGV was detected, another PGV would be sought. This old “single gene/single syndrome” testing was expensive, time consuming, and inefficient, and has been supplanted by multigene cancer panel testing (MGPT). MGPT-driven low-cost, high-throughput testing has widespread insurance coverage in eligible patients. Since considerable clinical phenotypic overlap exists between HCCSs, casting a broader net for determining PGV, compared with a more limited approach, allows for greater identification of carriers of PGV as well as variants of uncertain significance.

The frequency of PGV detection by MGPT in individuals with CRC is dependent on age at diagnosis and presence of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency in the tumor. According to one review, PGVs on MGPT are detected in approximately 10% and 34% of individuals aged more than 50 and more than 35 years, respectively.1 Pearlman and colleagues performed MGPT in 450 patients with CRC less than 50 years.2 PGV were found in 8% and 83.3% of cases with MMR-proficient and -deficient tumors, respectively. Overall, 33.3% of patients did not meet genetic testing criteria for the gene in which a PGV was detected, raising the impetus to consider MGPT in all patients with CRC. The Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer and National Comprehensive Cancer Network provide guidance on who warrants PGV testing.3,4

Germline testing outcomes and general approaches to patient management are provided in the graphic. HCCS are common and MGPT has broadened the identification of carriers of PGVs. In spite of advances in genetic testing technology, family history remains crucial to deploying risk-mitigation measures, regardless of the results of genetic testing.

Dr. Burke is in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic. She disclosed ties to Janssen Pharma, Emtora Biosciences, Freenome, SLA Pharma, and Ambry Genetics. Dr. Burke is a member of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline on Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Stoffel E and Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan;158(2):341-353.

2. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Apr 1;3(4):464-471.

3. Heald B et al. Fam Cancer. 2020 Jul;19(3):223-239.

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 1.2022. 2022 Jun 8.

AT DDW 2022

What is new in cirrhosis management? From frailty to palliative care

There is a rich science around the management of the cirrhotic liver itself – for example, pragmatic prognostic markers such as MELDNa, data-driven strategies to prevent variceal bleeding, and well-utilized algorithms to manage ascites.

But what is new in cirrhosis management is an emerging science around the management of the person living with cirrhosis – a science that seeks to understand how these individuals function in their day-to-day lives, how they feel, and how they can best prepare for their future. What is so exciting is that the field is moving beyond simply understanding those complex aspects of the patient, which is important in and of itself, toward developing practical tools to help clinicians assess their patients’ symptoms and strategies to help improve their patients’ lived experience. Although terms such as “frailty,” “palliative care,” and “advance care planning” are not new in cirrhosis per se, they are now recognized as distinct patient-centered constructs that are highly relevant to the management of patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, these constructs have been codified through two recent guidance statements sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.1,2 Pragmatic tools are emerging to facilitate the integration of these patient-centered constructs into routine clinical practice, tools such as the Liver Frailty Index, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System adapted for patients with cirrhosis, and structured frameworks for guiding goals-of-care discussions. The incorporation of these tools allows for new management strategies directed toward improving the patient’s experience such as timely initiation of nutrition and activity-based interventions, algorithms for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies for symptom management, and online/video-guided approaches to articulating one’s goals of care.

So, what is new in cirrhosis management is that we are moving beyond managing the cirrhotic liver itself to considering how cirrhosis and its complications impact the patient as a whole. In doing so, we are turning the art of hepatology care into science that can be applied systematically at the bedside for every patient, with the goal of improving care for all patients living with cirrhosis.

Dr. Lai holds the Endowed Professorship of Liver Health and Transplantation at the University of California, San Francisco. She reports having no conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Lai JC et al. Hepatology. 2021 Sep;74(3):1611-44.

2. Rogal S et al. Hepatology. 2022 Feb 1. doi: 10.1002/hep.32378.

There is a rich science around the management of the cirrhotic liver itself – for example, pragmatic prognostic markers such as MELDNa, data-driven strategies to prevent variceal bleeding, and well-utilized algorithms to manage ascites.

But what is new in cirrhosis management is an emerging science around the management of the person living with cirrhosis – a science that seeks to understand how these individuals function in their day-to-day lives, how they feel, and how they can best prepare for their future. What is so exciting is that the field is moving beyond simply understanding those complex aspects of the patient, which is important in and of itself, toward developing practical tools to help clinicians assess their patients’ symptoms and strategies to help improve their patients’ lived experience. Although terms such as “frailty,” “palliative care,” and “advance care planning” are not new in cirrhosis per se, they are now recognized as distinct patient-centered constructs that are highly relevant to the management of patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, these constructs have been codified through two recent guidance statements sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.1,2 Pragmatic tools are emerging to facilitate the integration of these patient-centered constructs into routine clinical practice, tools such as the Liver Frailty Index, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System adapted for patients with cirrhosis, and structured frameworks for guiding goals-of-care discussions. The incorporation of these tools allows for new management strategies directed toward improving the patient’s experience such as timely initiation of nutrition and activity-based interventions, algorithms for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies for symptom management, and online/video-guided approaches to articulating one’s goals of care.

So, what is new in cirrhosis management is that we are moving beyond managing the cirrhotic liver itself to considering how cirrhosis and its complications impact the patient as a whole. In doing so, we are turning the art of hepatology care into science that can be applied systematically at the bedside for every patient, with the goal of improving care for all patients living with cirrhosis.

Dr. Lai holds the Endowed Professorship of Liver Health and Transplantation at the University of California, San Francisco. She reports having no conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Lai JC et al. Hepatology. 2021 Sep;74(3):1611-44.

2. Rogal S et al. Hepatology. 2022 Feb 1. doi: 10.1002/hep.32378.

There is a rich science around the management of the cirrhotic liver itself – for example, pragmatic prognostic markers such as MELDNa, data-driven strategies to prevent variceal bleeding, and well-utilized algorithms to manage ascites.

But what is new in cirrhosis management is an emerging science around the management of the person living with cirrhosis – a science that seeks to understand how these individuals function in their day-to-day lives, how they feel, and how they can best prepare for their future. What is so exciting is that the field is moving beyond simply understanding those complex aspects of the patient, which is important in and of itself, toward developing practical tools to help clinicians assess their patients’ symptoms and strategies to help improve their patients’ lived experience. Although terms such as “frailty,” “palliative care,” and “advance care planning” are not new in cirrhosis per se, they are now recognized as distinct patient-centered constructs that are highly relevant to the management of patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, these constructs have been codified through two recent guidance statements sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.1,2 Pragmatic tools are emerging to facilitate the integration of these patient-centered constructs into routine clinical practice, tools such as the Liver Frailty Index, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System adapted for patients with cirrhosis, and structured frameworks for guiding goals-of-care discussions. The incorporation of these tools allows for new management strategies directed toward improving the patient’s experience such as timely initiation of nutrition and activity-based interventions, algorithms for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies for symptom management, and online/video-guided approaches to articulating one’s goals of care.

So, what is new in cirrhosis management is that we are moving beyond managing the cirrhotic liver itself to considering how cirrhosis and its complications impact the patient as a whole. In doing so, we are turning the art of hepatology care into science that can be applied systematically at the bedside for every patient, with the goal of improving care for all patients living with cirrhosis.

Dr. Lai holds the Endowed Professorship of Liver Health and Transplantation at the University of California, San Francisco. She reports having no conflicts of interest. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

References

1. Lai JC et al. Hepatology. 2021 Sep;74(3):1611-44.

2. Rogal S et al. Hepatology. 2022 Feb 1. doi: 10.1002/hep.32378.

AT DDW 2022

Barrett’s esophagus: Key new concepts

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). The rationale for early detection of BE rests on the premise that, after the diagnosis of BE, patients can be placed under endoscopic surveillance to detect prevalent and incident dysplasia and EAC. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) can reduce progression to EAC. Guidelines support endoscopic screening for BE in those with multiple (three or more) risk factors.

However, endoscopy is expensive, invasive, and not widely utilized (less than 10% of those eligible are screened). Most patients with BE are unaware of their diagnosis and hence not under surveillance. Nonendoscopic techniques of BE detection – swallowed cell collection devices providing rich esophageal cytology specimens combined with biomarkers – are being developed. Case-control studies have shown promising accuracy and a recent UK pragmatic primary care study showed the ability of this technology to increase BE detection safely.

Detection of dysplasia in endoscopic surveillance is critical and the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) has been recently proposed as a quality marker. The NDR is the ratio of HGD+EAC detected to all patients with BE undergoing their first surveillance endoscopy. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed an inverse association between NDR and postendoscopy BE neoplasia. Additional and prospective studies are required to further correlate NDR values to clinically relevant outcomes similar to the association between adenoma detection rate and postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer.

Detection of dysplasia with endoscopic surveillance is challenging because of sampling error inherent in the Seattle protocol. A recent technology, Wide Area Transepithelial Sampling–3D (WATS), combines the concept of increased sampling of the BE mucosa by using a stiff endoscopic brush followed by use of artificial intelligence neural network enabled selection of abnormal cells, which are presented to a pathologist. This technology has been shown to increase dysplasia and HGD detection, compared to endoscopic surveillance, in a systematic review and meta-analysis. However, WATS is negative in a substantial proportion of cases in which endoscopic Seattle protocol reveals dysplasia. In addition, only limited data are available on the natural history of WATS LGD or HGD. Confirmation of WATS-only dysplasia (LGD, HGD, or EAC) by endoscopic histology is also recommended before the institution of EET. Finally, assessment of progression risk in those with BE is critical to enable more personalized follow up recommendations. Clinical risk scores integrating age, sex, smoking history, and LGD have been proposed and validated. A recent tissue systems pathology test has been shown in multiple case-control studies to identify a subset of BE patients who are at higher risk of progression, independent of LGD. This test is highly specific but only modestly sensitive in identifying progressors.

Dr. Iyer is professor of medicine, director of the Esophageal Interest Group, and codirector of the Advanced Esophageal Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minn. He reports relationships with Exact Sciences, Pentax Medical, and others. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). The rationale for early detection of BE rests on the premise that, after the diagnosis of BE, patients can be placed under endoscopic surveillance to detect prevalent and incident dysplasia and EAC. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) can reduce progression to EAC. Guidelines support endoscopic screening for BE in those with multiple (three or more) risk factors.

However, endoscopy is expensive, invasive, and not widely utilized (less than 10% of those eligible are screened). Most patients with BE are unaware of their diagnosis and hence not under surveillance. Nonendoscopic techniques of BE detection – swallowed cell collection devices providing rich esophageal cytology specimens combined with biomarkers – are being developed. Case-control studies have shown promising accuracy and a recent UK pragmatic primary care study showed the ability of this technology to increase BE detection safely.

Detection of dysplasia in endoscopic surveillance is critical and the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) has been recently proposed as a quality marker. The NDR is the ratio of HGD+EAC detected to all patients with BE undergoing their first surveillance endoscopy. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed an inverse association between NDR and postendoscopy BE neoplasia. Additional and prospective studies are required to further correlate NDR values to clinically relevant outcomes similar to the association between adenoma detection rate and postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer.

Detection of dysplasia with endoscopic surveillance is challenging because of sampling error inherent in the Seattle protocol. A recent technology, Wide Area Transepithelial Sampling–3D (WATS), combines the concept of increased sampling of the BE mucosa by using a stiff endoscopic brush followed by use of artificial intelligence neural network enabled selection of abnormal cells, which are presented to a pathologist. This technology has been shown to increase dysplasia and HGD detection, compared to endoscopic surveillance, in a systematic review and meta-analysis. However, WATS is negative in a substantial proportion of cases in which endoscopic Seattle protocol reveals dysplasia. In addition, only limited data are available on the natural history of WATS LGD or HGD. Confirmation of WATS-only dysplasia (LGD, HGD, or EAC) by endoscopic histology is also recommended before the institution of EET. Finally, assessment of progression risk in those with BE is critical to enable more personalized follow up recommendations. Clinical risk scores integrating age, sex, smoking history, and LGD have been proposed and validated. A recent tissue systems pathology test has been shown in multiple case-control studies to identify a subset of BE patients who are at higher risk of progression, independent of LGD. This test is highly specific but only modestly sensitive in identifying progressors.

Dr. Iyer is professor of medicine, director of the Esophageal Interest Group, and codirector of the Advanced Esophageal Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minn. He reports relationships with Exact Sciences, Pentax Medical, and others. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). The rationale for early detection of BE rests on the premise that, after the diagnosis of BE, patients can be placed under endoscopic surveillance to detect prevalent and incident dysplasia and EAC. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) can reduce progression to EAC. Guidelines support endoscopic screening for BE in those with multiple (three or more) risk factors.

However, endoscopy is expensive, invasive, and not widely utilized (less than 10% of those eligible are screened). Most patients with BE are unaware of their diagnosis and hence not under surveillance. Nonendoscopic techniques of BE detection – swallowed cell collection devices providing rich esophageal cytology specimens combined with biomarkers – are being developed. Case-control studies have shown promising accuracy and a recent UK pragmatic primary care study showed the ability of this technology to increase BE detection safely.

Detection of dysplasia in endoscopic surveillance is critical and the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) has been recently proposed as a quality marker. The NDR is the ratio of HGD+EAC detected to all patients with BE undergoing their first surveillance endoscopy. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed an inverse association between NDR and postendoscopy BE neoplasia. Additional and prospective studies are required to further correlate NDR values to clinically relevant outcomes similar to the association between adenoma detection rate and postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer.

Detection of dysplasia with endoscopic surveillance is challenging because of sampling error inherent in the Seattle protocol. A recent technology, Wide Area Transepithelial Sampling–3D (WATS), combines the concept of increased sampling of the BE mucosa by using a stiff endoscopic brush followed by use of artificial intelligence neural network enabled selection of abnormal cells, which are presented to a pathologist. This technology has been shown to increase dysplasia and HGD detection, compared to endoscopic surveillance, in a systematic review and meta-analysis. However, WATS is negative in a substantial proportion of cases in which endoscopic Seattle protocol reveals dysplasia. In addition, only limited data are available on the natural history of WATS LGD or HGD. Confirmation of WATS-only dysplasia (LGD, HGD, or EAC) by endoscopic histology is also recommended before the institution of EET. Finally, assessment of progression risk in those with BE is critical to enable more personalized follow up recommendations. Clinical risk scores integrating age, sex, smoking history, and LGD have been proposed and validated. A recent tissue systems pathology test has been shown in multiple case-control studies to identify a subset of BE patients who are at higher risk of progression, independent of LGD. This test is highly specific but only modestly sensitive in identifying progressors.

Dr. Iyer is professor of medicine, director of the Esophageal Interest Group, and codirector of the Advanced Esophageal Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minn. He reports relationships with Exact Sciences, Pentax Medical, and others. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

AT DDW 2022

The Best of DDW 2022: Feel the history

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.

Uri Ladabaum, MD, MS, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reports serving on the advisory board for UniversalDx and Lean Medical and as a consultant for Medtronic, Clinical Genomics, Guardant Health, and Freenome. Dr. Ladabaum made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):1855-7.

2. Ladabaum U. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):938-9.

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.

Uri Ladabaum, MD, MS, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reports serving on the advisory board for UniversalDx and Lean Medical and as a consultant for Medtronic, Clinical Genomics, Guardant Health, and Freenome. Dr. Ladabaum made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):1855-7.

2. Ladabaum U. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):938-9.

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.