User login

Pediatric vitiligo primarily affects those aged 10-17

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Among children and adolescents, vitiligo appears to predominately affect nonwhite boys and girls between the ages of 10 and 17 years, results from a large cross-sectional analysis demonstrated.

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Jessica Haber, MD, said that, while it’s known vitiligo can have its onset in childhood, there have been no population-based analyses in the United States specific to children and adolescents with the condition.

“We wanted to examine disease burden in the U.S. specifically, because we have such a diverse population,” said Dr. Haber, a second-year resident in the department of dermatology at Northwell Health, New York.

For the study, she and her associates used IBM’s Explorys research analytics platform to conduct a cross-sectional analysis of more than 55 million unique patients across all census regions of the United States. There were 1,630 vitiligo cases identified from a total of 4,242,400 pediatric patients, for an overall standard prevalence of 0.04%, or 40.1 per 100,000 children and adolescents. The proportion of female and male patients with vitiligo was similar (49.1% and 50.9%, respectively), and nearly three-fourths (72.3%) were 10 years of age or older.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the prevalence of vitiligo between males and females (40.2 per 100,000 vs. 40 per 100,000, respectively). The standardized prevalence of vitiligo was greatest in pediatric patients who were of “other” races and ethnicities (including Asian, Hispanic, multiracial, and other; 69.1 per 100,000), followed by African Americans (51.5 per 100,000) and whites (37.9 per 100,000). There were too few vitiligo cases among biracial patients to determine standardized estimates, but the crude prevalence was greatest in this group (68.7 per 100,000).

Two factors could contribute to the increased prevalence of vitiligo observed in nonwhite children and adolescents, Dr. Haber said. One is selection bias.

“It has been reported that both children and adults with higher Fitzpatrick skin types tend to have increased morbidity of their vitiligo, so it may be a selection bias that these patients are seeking out treatment for their disease,” she said. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[1]:1-13). That might explain some of our findings, as well.”

While the study findings “don’t necessarily change clinical practice, it is good for us to have a sense of the burden of disease in the pediatric patient population of vitiligo, and to be aware that this is a disease that predominately affects non-Caucasian children and adolescents,” Dr. Haber concluded.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Among children and adolescents, vitiligo appears to predominately affect nonwhite boys and girls between the ages of 10 and 17 years, results from a large cross-sectional analysis demonstrated.

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Jessica Haber, MD, said that, while it’s known vitiligo can have its onset in childhood, there have been no population-based analyses in the United States specific to children and adolescents with the condition.

“We wanted to examine disease burden in the U.S. specifically, because we have such a diverse population,” said Dr. Haber, a second-year resident in the department of dermatology at Northwell Health, New York.

For the study, she and her associates used IBM’s Explorys research analytics platform to conduct a cross-sectional analysis of more than 55 million unique patients across all census regions of the United States. There were 1,630 vitiligo cases identified from a total of 4,242,400 pediatric patients, for an overall standard prevalence of 0.04%, or 40.1 per 100,000 children and adolescents. The proportion of female and male patients with vitiligo was similar (49.1% and 50.9%, respectively), and nearly three-fourths (72.3%) were 10 years of age or older.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the prevalence of vitiligo between males and females (40.2 per 100,000 vs. 40 per 100,000, respectively). The standardized prevalence of vitiligo was greatest in pediatric patients who were of “other” races and ethnicities (including Asian, Hispanic, multiracial, and other; 69.1 per 100,000), followed by African Americans (51.5 per 100,000) and whites (37.9 per 100,000). There were too few vitiligo cases among biracial patients to determine standardized estimates, but the crude prevalence was greatest in this group (68.7 per 100,000).

Two factors could contribute to the increased prevalence of vitiligo observed in nonwhite children and adolescents, Dr. Haber said. One is selection bias.

“It has been reported that both children and adults with higher Fitzpatrick skin types tend to have increased morbidity of their vitiligo, so it may be a selection bias that these patients are seeking out treatment for their disease,” she said. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[1]:1-13). That might explain some of our findings, as well.”

While the study findings “don’t necessarily change clinical practice, it is good for us to have a sense of the burden of disease in the pediatric patient population of vitiligo, and to be aware that this is a disease that predominately affects non-Caucasian children and adolescents,” Dr. Haber concluded.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Among children and adolescents, vitiligo appears to predominately affect nonwhite boys and girls between the ages of 10 and 17 years, results from a large cross-sectional analysis demonstrated.

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Jessica Haber, MD, said that, while it’s known vitiligo can have its onset in childhood, there have been no population-based analyses in the United States specific to children and adolescents with the condition.

“We wanted to examine disease burden in the U.S. specifically, because we have such a diverse population,” said Dr. Haber, a second-year resident in the department of dermatology at Northwell Health, New York.

For the study, she and her associates used IBM’s Explorys research analytics platform to conduct a cross-sectional analysis of more than 55 million unique patients across all census regions of the United States. There were 1,630 vitiligo cases identified from a total of 4,242,400 pediatric patients, for an overall standard prevalence of 0.04%, or 40.1 per 100,000 children and adolescents. The proportion of female and male patients with vitiligo was similar (49.1% and 50.9%, respectively), and nearly three-fourths (72.3%) were 10 years of age or older.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the prevalence of vitiligo between males and females (40.2 per 100,000 vs. 40 per 100,000, respectively). The standardized prevalence of vitiligo was greatest in pediatric patients who were of “other” races and ethnicities (including Asian, Hispanic, multiracial, and other; 69.1 per 100,000), followed by African Americans (51.5 per 100,000) and whites (37.9 per 100,000). There were too few vitiligo cases among biracial patients to determine standardized estimates, but the crude prevalence was greatest in this group (68.7 per 100,000).

Two factors could contribute to the increased prevalence of vitiligo observed in nonwhite children and adolescents, Dr. Haber said. One is selection bias.

“It has been reported that both children and adults with higher Fitzpatrick skin types tend to have increased morbidity of their vitiligo, so it may be a selection bias that these patients are seeking out treatment for their disease,” she said. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[1]:1-13). That might explain some of our findings, as well.”

While the study findings “don’t necessarily change clinical practice, it is good for us to have a sense of the burden of disease in the pediatric patient population of vitiligo, and to be aware that this is a disease that predominately affects non-Caucasian children and adolescents,” Dr. Haber concluded.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Vitiligo appears to predominately affect nonwhite boys and girls 10 years of age and older in the pediatric population.

Major finding: Of pediatric patients with vitiligo, 72.3% were 10 years of age or older.

Study details: A cross-sectional analysis of 1,630 vitiligo cases identified from a total of 4,242,400 pediatric patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Study explores adolescents’ views on their skin tone, pressure to tan

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Shivani Patel, MD, said that prior research on skin color had focused mainly on adults and its impact on self-esteem and perceived attractiveness, yet little data are available on perceptions of skin color among adolescents.

“During puberty, adolescents receive pressure from friends, family, and social media to conform to a certain acceptable standard of skin tone,” said Dr. Patel, a chief resident in the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “They will often engage in risky behaviors such as tanning bed use, suntanning, and use of skin lightening creams.”

In an effort to characterize the attitudes of adolescents about their skin tone, she and her associates recruited 50 patients aged 12-19 years who were seen at the Johns Hopkins dermatology clinics. Slightly more than half (56%) were female. They were asked to complete surveys on their use of sunscreen, tanning beds, and skin-lightening creams, as well as to report any family or friends who have used these interventions.

Next, the researchers used Pantone’s Capsure device to record each subject’s skin tone according to a palate of 110 skin colors available from Pantone’s SkinTone Guide, which is intended to match and reproduce lifelike skin tones in a variety of industries. The adolescents were then given the palette and asked which skin tone they felt best represented their skin and which skin tone they wished they had. These differences were compared with their objective measurement by the study team.

Of all respondents, 20% indicated that they felt pressure to have tan skin and were likely to engage in suntanning (P less than .001), a feeling they said started around the age of 12 years and stemmed from perceived pressure from friends and celebrity figures. Those who suntanned were more likely to wear sunscreen (P less than .01), a finding “that was reassuring and showed that they are aware of sunscreen and sun safety,” Dr. Patel said. However, about half of the respondents reported never wearing sunscreen and only two reported wearing sunscreen daily. No one reported using tanning beds, but 8% reported that a family member used them. One adolescent reported using skin lightening creams, and three reported that their mothers used them.

The researchers also found that black and Asian study participants were significantly more likely to desire a skin tone lighter than what they perceived their skin tone to be, while white participants were significantly more likely to desire a darker skin tone (P less than .011 for both associations).

The findings suggest that sun safety initiatives should target prepubertal patients before they engage in risky behaviors, Dr. Patel said. She acknowledged that the small sample size is a limitation of the study, but said that she and her associates hope to conduct a larger-scale analysis.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Shivani Patel, MD, said that prior research on skin color had focused mainly on adults and its impact on self-esteem and perceived attractiveness, yet little data are available on perceptions of skin color among adolescents.

“During puberty, adolescents receive pressure from friends, family, and social media to conform to a certain acceptable standard of skin tone,” said Dr. Patel, a chief resident in the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “They will often engage in risky behaviors such as tanning bed use, suntanning, and use of skin lightening creams.”

In an effort to characterize the attitudes of adolescents about their skin tone, she and her associates recruited 50 patients aged 12-19 years who were seen at the Johns Hopkins dermatology clinics. Slightly more than half (56%) were female. They were asked to complete surveys on their use of sunscreen, tanning beds, and skin-lightening creams, as well as to report any family or friends who have used these interventions.

Next, the researchers used Pantone’s Capsure device to record each subject’s skin tone according to a palate of 110 skin colors available from Pantone’s SkinTone Guide, which is intended to match and reproduce lifelike skin tones in a variety of industries. The adolescents were then given the palette and asked which skin tone they felt best represented their skin and which skin tone they wished they had. These differences were compared with their objective measurement by the study team.

Of all respondents, 20% indicated that they felt pressure to have tan skin and were likely to engage in suntanning (P less than .001), a feeling they said started around the age of 12 years and stemmed from perceived pressure from friends and celebrity figures. Those who suntanned were more likely to wear sunscreen (P less than .01), a finding “that was reassuring and showed that they are aware of sunscreen and sun safety,” Dr. Patel said. However, about half of the respondents reported never wearing sunscreen and only two reported wearing sunscreen daily. No one reported using tanning beds, but 8% reported that a family member used them. One adolescent reported using skin lightening creams, and three reported that their mothers used them.

The researchers also found that black and Asian study participants were significantly more likely to desire a skin tone lighter than what they perceived their skin tone to be, while white participants were significantly more likely to desire a darker skin tone (P less than .011 for both associations).

The findings suggest that sun safety initiatives should target prepubertal patients before they engage in risky behaviors, Dr. Patel said. She acknowledged that the small sample size is a limitation of the study, but said that she and her associates hope to conduct a larger-scale analysis.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

During an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, lead study author Shivani Patel, MD, said that prior research on skin color had focused mainly on adults and its impact on self-esteem and perceived attractiveness, yet little data are available on perceptions of skin color among adolescents.

“During puberty, adolescents receive pressure from friends, family, and social media to conform to a certain acceptable standard of skin tone,” said Dr. Patel, a chief resident in the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “They will often engage in risky behaviors such as tanning bed use, suntanning, and use of skin lightening creams.”

In an effort to characterize the attitudes of adolescents about their skin tone, she and her associates recruited 50 patients aged 12-19 years who were seen at the Johns Hopkins dermatology clinics. Slightly more than half (56%) were female. They were asked to complete surveys on their use of sunscreen, tanning beds, and skin-lightening creams, as well as to report any family or friends who have used these interventions.

Next, the researchers used Pantone’s Capsure device to record each subject’s skin tone according to a palate of 110 skin colors available from Pantone’s SkinTone Guide, which is intended to match and reproduce lifelike skin tones in a variety of industries. The adolescents were then given the palette and asked which skin tone they felt best represented their skin and which skin tone they wished they had. These differences were compared with their objective measurement by the study team.

Of all respondents, 20% indicated that they felt pressure to have tan skin and were likely to engage in suntanning (P less than .001), a feeling they said started around the age of 12 years and stemmed from perceived pressure from friends and celebrity figures. Those who suntanned were more likely to wear sunscreen (P less than .01), a finding “that was reassuring and showed that they are aware of sunscreen and sun safety,” Dr. Patel said. However, about half of the respondents reported never wearing sunscreen and only two reported wearing sunscreen daily. No one reported using tanning beds, but 8% reported that a family member used them. One adolescent reported using skin lightening creams, and three reported that their mothers used them.

The researchers also found that black and Asian study participants were significantly more likely to desire a skin tone lighter than what they perceived their skin tone to be, while white participants were significantly more likely to desire a darker skin tone (P less than .011 for both associations).

The findings suggest that sun safety initiatives should target prepubertal patients before they engage in risky behaviors, Dr. Patel said. She acknowledged that the small sample size is a limitation of the study, but said that she and her associates hope to conduct a larger-scale analysis.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Sun safety initiatives should target prepubertal patients before they engage in risky behaviors.

Major finding: One in five adolescents indicated that they felt pressure to have tan skin and were likely to engage in suntanning (P less than .001).

Study details: A survey of 50 patients aged 12-19 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures.

Early-onset atopic dermatitis linked to elevated risk for seasonal allergies and asthma

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

AT SPD 2018

Site of morphea lesions predicts risk of extracutaneous manifestations

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Extracutaneous involvement is more likely when morphea lesions are present on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head.

Major finding: Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement.

Study details: A multicenter retrospective study of 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

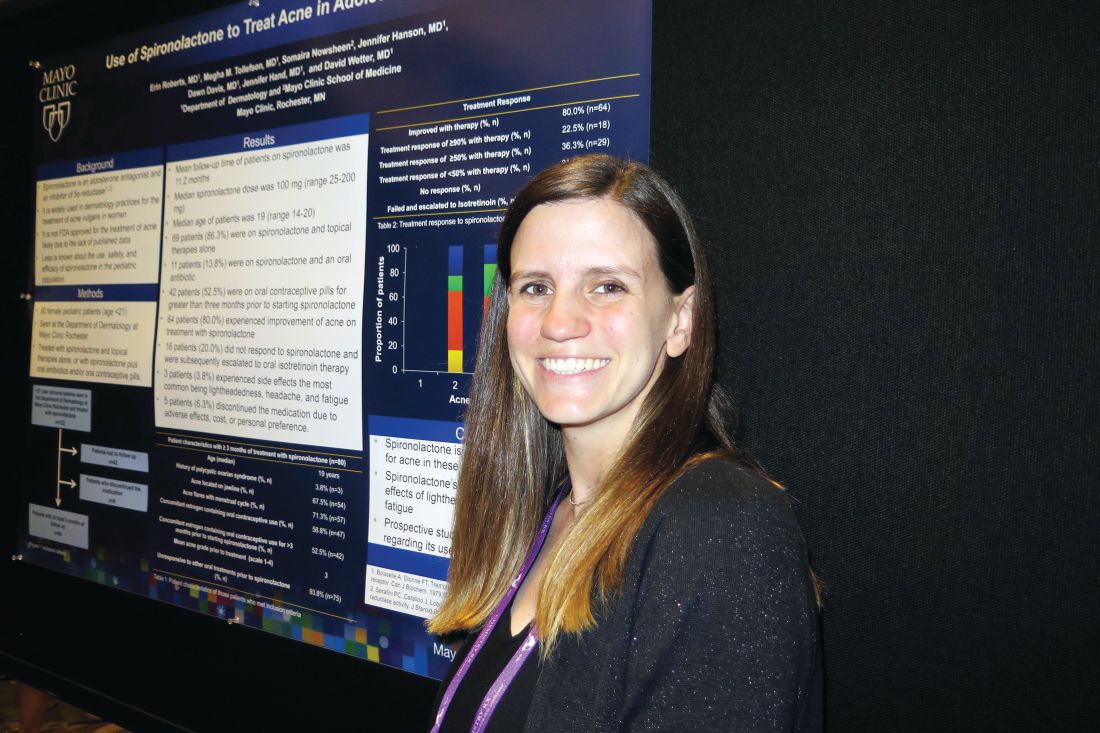

Spironolactone effectively treats acne in adolescent females

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Use of spironolactone for acne may be limited by side effects of lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue.

Major finding: Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone.

Study details: A retrospective review of 80 adolescent females who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills.

Disclosures: Dr. Roberts reported having no financial disclosures.

New analysis improves understanding of PHACE syndrome

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Children with large, high-risk facial hemangiomas should be prioritized for PHACE syndrome work-up.

Major finding: On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25 cm2 (PPV, 44.8%; P less than .05 for all associations).

Study details: A retrospective evaluation of 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Association. Dr. Cotton reported having no financial disclosures.