User login

New atopic dermatitis agents expand treatment options

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

REPORTING FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Case report: Longstanding actinic keratosis responds to kanuka honey

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Not all honeys are created equal, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It seems that kanuka is the new manuka,” said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. These lesser-known New Zealand bush honeys may be something to watch because research and case reports continue to provide intriguing hints of how these honeys exert their immunomodulatory effects on skin, he commented, describing a recent case report describing the elimination of a large, long-standing actinic keratosis (AK) with application of kanuka honey.

Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) is a large bush native to both Australia and New Zealand. Kanuka (Kunzea ericoides) is quite similar in size and appearance, but native only to New Zealand. Honey made from the flowers of these bushes possesses some unique properties that make it an attractive addition to wound healing regimens, according to a 2014 study (Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:149-58).

The study examined samples of manuka, kanuka, a manuka/kanuka blend, and clover honey. The investigators found that kanuka honey, and to a lesser extent manuka honey, exerted a potent anti-inflammatory effect in human embryonic kidney cells. The honeys interfered with toll-like receptor 1 and 2 signaling, which would reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Kanuka’s potency seems directly related to its unusually high level of arabinogalactan, according to Saras Mane, MD, primary author of the AK case report (Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018 May 31;2018:4628971). Dr. Mane is with the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand in Wellington.

“The immunomodulatory properties of kanuka honey in particular are thought to be more potent than other New Zealand honeys due to the relatively high concentrations of arabinogalactan proteins present,” Dr. Mane and his coauthors wrote in the case report. “These proteins have been shown to stimulate release of TNF-alpha from monocytic cell lines in vitro.”

The report involved a 66-year-old man who was enrolled in a randomized trial of a commercialized medical-grade kanuka honey ointment (Honevo, 90% kanuka honey, 10% glycerin; Honeylab NZ) for rosacea.

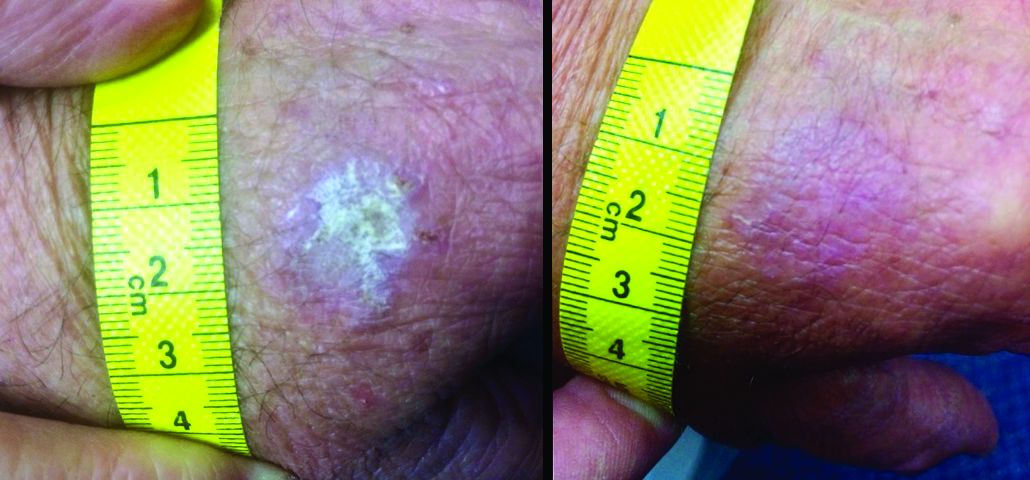

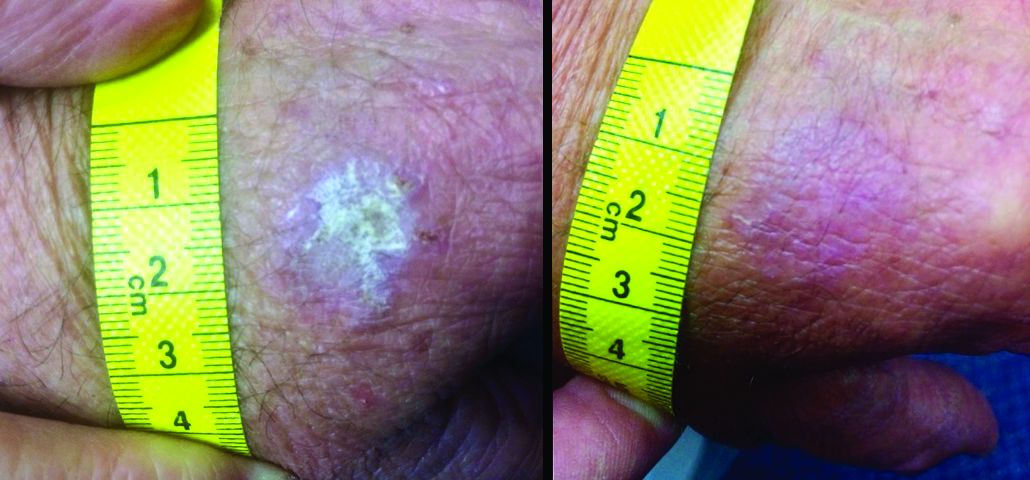

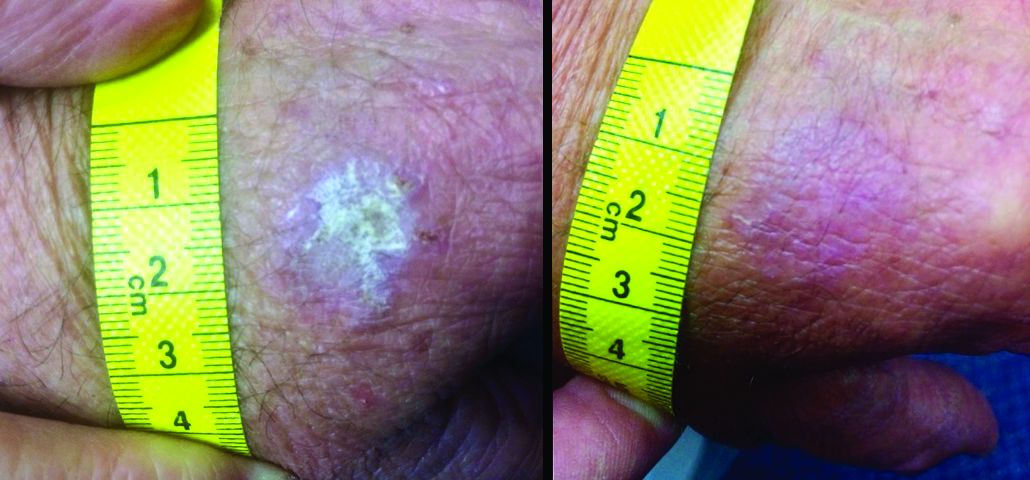

The patient also had multiple AKs, including a raised, crusted, scaly lesion measuring 20 mm by 21 mm with marginal erythema on the back of one hand. The lesion had been present and dormant for a number of years, but it had recently begun to grow.

“This gentleman decided he’d just try the honey on his AK, too,” Dr. Rosen said. The man reported applying a small amount to the lesion and erythematous area once a day, leaving it on for about 30 to 60 minutes. After 5 days, he stopped because the lesion became tender. During the next two days, the patient reported “picking at” the lesion, which was softening. He repeated this cycle of treatment for 3 months with no other therapy to the lesion.

“The lesion gradually reduced in size with an initial rapid reduction in its dry, crusted nature,” the authors reported. “After 3 months, residual appearance of the lesion was a 20 mm by 17 mm area of pink skin with no elements of hypertrophy, crusting, or loss of skin integrity,” they noted. “At 6 months, there were no signs of recurrence. At 9 months, the appearance of the skin had fully returned to normal. A telephone follow-up was conducted at 2 years after treatment, and the patient reported that his skin in the area was still completely normal and that there were no signs of recurrence.”

Dr. Mane noted that they had only clinical evidence, and no histology of the lesion either before or after its change. “The AK was diagnosed and treated in primary care, where it is not usual for AKs to be biopsied, and the decision to write up the case was made after the course of treatment had finished,” they said.

“Immunomodulatory topical agents are already widely used in the treatment of AK as an immune component is evident in its etiology,” they wrote. “Immunocompromised patients have 250 times the risk of developing an AK than the general population.”

Dr. Rosen said that kanuka honey is also being investigated in psoriasis, eczema, acne, herpes simplex virus, and diaper dermatitis. It is also being studied for rosacea.

Dr. Mane declared no conflicts of interest. Some coauthors disclosed that they have previously received funding from HoneyLab NZ. Dr. Rosen has no commercial interest in HoneyLab.

The meeting was sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education; Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Not all honeys are created equal, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It seems that kanuka is the new manuka,” said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. These lesser-known New Zealand bush honeys may be something to watch because research and case reports continue to provide intriguing hints of how these honeys exert their immunomodulatory effects on skin, he commented, describing a recent case report describing the elimination of a large, long-standing actinic keratosis (AK) with application of kanuka honey.

Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) is a large bush native to both Australia and New Zealand. Kanuka (Kunzea ericoides) is quite similar in size and appearance, but native only to New Zealand. Honey made from the flowers of these bushes possesses some unique properties that make it an attractive addition to wound healing regimens, according to a 2014 study (Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:149-58).

The study examined samples of manuka, kanuka, a manuka/kanuka blend, and clover honey. The investigators found that kanuka honey, and to a lesser extent manuka honey, exerted a potent anti-inflammatory effect in human embryonic kidney cells. The honeys interfered with toll-like receptor 1 and 2 signaling, which would reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Kanuka’s potency seems directly related to its unusually high level of arabinogalactan, according to Saras Mane, MD, primary author of the AK case report (Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018 May 31;2018:4628971). Dr. Mane is with the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand in Wellington.

“The immunomodulatory properties of kanuka honey in particular are thought to be more potent than other New Zealand honeys due to the relatively high concentrations of arabinogalactan proteins present,” Dr. Mane and his coauthors wrote in the case report. “These proteins have been shown to stimulate release of TNF-alpha from monocytic cell lines in vitro.”

The report involved a 66-year-old man who was enrolled in a randomized trial of a commercialized medical-grade kanuka honey ointment (Honevo, 90% kanuka honey, 10% glycerin; Honeylab NZ) for rosacea.

The patient also had multiple AKs, including a raised, crusted, scaly lesion measuring 20 mm by 21 mm with marginal erythema on the back of one hand. The lesion had been present and dormant for a number of years, but it had recently begun to grow.

“This gentleman decided he’d just try the honey on his AK, too,” Dr. Rosen said. The man reported applying a small amount to the lesion and erythematous area once a day, leaving it on for about 30 to 60 minutes. After 5 days, he stopped because the lesion became tender. During the next two days, the patient reported “picking at” the lesion, which was softening. He repeated this cycle of treatment for 3 months with no other therapy to the lesion.

“The lesion gradually reduced in size with an initial rapid reduction in its dry, crusted nature,” the authors reported. “After 3 months, residual appearance of the lesion was a 20 mm by 17 mm area of pink skin with no elements of hypertrophy, crusting, or loss of skin integrity,” they noted. “At 6 months, there were no signs of recurrence. At 9 months, the appearance of the skin had fully returned to normal. A telephone follow-up was conducted at 2 years after treatment, and the patient reported that his skin in the area was still completely normal and that there were no signs of recurrence.”

Dr. Mane noted that they had only clinical evidence, and no histology of the lesion either before or after its change. “The AK was diagnosed and treated in primary care, where it is not usual for AKs to be biopsied, and the decision to write up the case was made after the course of treatment had finished,” they said.

“Immunomodulatory topical agents are already widely used in the treatment of AK as an immune component is evident in its etiology,” they wrote. “Immunocompromised patients have 250 times the risk of developing an AK than the general population.”

Dr. Rosen said that kanuka honey is also being investigated in psoriasis, eczema, acne, herpes simplex virus, and diaper dermatitis. It is also being studied for rosacea.

Dr. Mane declared no conflicts of interest. Some coauthors disclosed that they have previously received funding from HoneyLab NZ. Dr. Rosen has no commercial interest in HoneyLab.

The meeting was sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education; Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Not all honeys are created equal, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It seems that kanuka is the new manuka,” said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. These lesser-known New Zealand bush honeys may be something to watch because research and case reports continue to provide intriguing hints of how these honeys exert their immunomodulatory effects on skin, he commented, describing a recent case report describing the elimination of a large, long-standing actinic keratosis (AK) with application of kanuka honey.

Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) is a large bush native to both Australia and New Zealand. Kanuka (Kunzea ericoides) is quite similar in size and appearance, but native only to New Zealand. Honey made from the flowers of these bushes possesses some unique properties that make it an attractive addition to wound healing regimens, according to a 2014 study (Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:149-58).

The study examined samples of manuka, kanuka, a manuka/kanuka blend, and clover honey. The investigators found that kanuka honey, and to a lesser extent manuka honey, exerted a potent anti-inflammatory effect in human embryonic kidney cells. The honeys interfered with toll-like receptor 1 and 2 signaling, which would reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Kanuka’s potency seems directly related to its unusually high level of arabinogalactan, according to Saras Mane, MD, primary author of the AK case report (Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018 May 31;2018:4628971). Dr. Mane is with the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand in Wellington.

“The immunomodulatory properties of kanuka honey in particular are thought to be more potent than other New Zealand honeys due to the relatively high concentrations of arabinogalactan proteins present,” Dr. Mane and his coauthors wrote in the case report. “These proteins have been shown to stimulate release of TNF-alpha from monocytic cell lines in vitro.”

The report involved a 66-year-old man who was enrolled in a randomized trial of a commercialized medical-grade kanuka honey ointment (Honevo, 90% kanuka honey, 10% glycerin; Honeylab NZ) for rosacea.

The patient also had multiple AKs, including a raised, crusted, scaly lesion measuring 20 mm by 21 mm with marginal erythema on the back of one hand. The lesion had been present and dormant for a number of years, but it had recently begun to grow.

“This gentleman decided he’d just try the honey on his AK, too,” Dr. Rosen said. The man reported applying a small amount to the lesion and erythematous area once a day, leaving it on for about 30 to 60 minutes. After 5 days, he stopped because the lesion became tender. During the next two days, the patient reported “picking at” the lesion, which was softening. He repeated this cycle of treatment for 3 months with no other therapy to the lesion.

“The lesion gradually reduced in size with an initial rapid reduction in its dry, crusted nature,” the authors reported. “After 3 months, residual appearance of the lesion was a 20 mm by 17 mm area of pink skin with no elements of hypertrophy, crusting, or loss of skin integrity,” they noted. “At 6 months, there were no signs of recurrence. At 9 months, the appearance of the skin had fully returned to normal. A telephone follow-up was conducted at 2 years after treatment, and the patient reported that his skin in the area was still completely normal and that there were no signs of recurrence.”

Dr. Mane noted that they had only clinical evidence, and no histology of the lesion either before or after its change. “The AK was diagnosed and treated in primary care, where it is not usual for AKs to be biopsied, and the decision to write up the case was made after the course of treatment had finished,” they said.

“Immunomodulatory topical agents are already widely used in the treatment of AK as an immune component is evident in its etiology,” they wrote. “Immunocompromised patients have 250 times the risk of developing an AK than the general population.”

Dr. Rosen said that kanuka honey is also being investigated in psoriasis, eczema, acne, herpes simplex virus, and diaper dermatitis. It is also being studied for rosacea.

Dr. Mane declared no conflicts of interest. Some coauthors disclosed that they have previously received funding from HoneyLab NZ. Dr. Rosen has no commercial interest in HoneyLab.

The meeting was sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education; Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM THE ANNUAL CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Guselkumab tops secukinumab over 48 weeks for plaque psoriasis

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Guselkumab bested secukinumab in a 48-week-long study of plaque psoriasis, with 84.5% of patients on the interleukin (IL)-23 blocker hitting at least a 90% improvement in their Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), compared with 70% of those taking secukinumab, which blocks IL-17.

The drug was numerically, but not significantly, better than secukinumab in the PASI 75 response at weeks 12 and 48 (84.6% for guselkumab at both time points vs. 80.2% for secukinumab at both time points). This finding on the primary secondary endpoint knocked the P values of the other five into “nominally significant” ranges. But the responses were still good enough for researchers to tag guselkumab as noninferior to its competitor, Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The difference also speaks to the difference in the drugs’ onset of action and its peak efficacy, said Dr. Sobell, of the department of dermatology at Tufts University, Boston.

“In both groups, the PASI 90 increased similarly in the first month,” to about 20%, he commented. “But at week 12 and after, it was consistently higher in guselkumab, peaking around week 28. Secukinumab peaked around weeks 16 to 20 and then slowly declined.”

Despite not being statistically significant, the other secondary efficacy endpoints were certainly enough to pique the audience’s attention. At week 48, guselkumab topped secukinumab in both PASI 100 (58.2% vs. 48.4%, respectively) and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 0 (62.2% vs. 50.4%) and 0-1 (85% vs. 74.9%).

ECLIPSE randomized 1,048 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis to 100-mg subcutaneous guselkumab at weeks 0, 4, and 12, followed by dosing every 8 weeks, or to 300-mg subcutaneous secukinumab administered by two subcutaneous injections of 150 mg at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, followed by dosing every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 90 response at week 48. Secondary endpoints were assessed at weeks 12 and 48, with safety monitoring through week 56.

The mean baseline Body Surface Area score was 24, and the mean PASI score was 20. Patients had already been treated with phototherapy (51.8%), nonbiologic systemic medications (53.7%), and biologics (29%). About 37% were naive to both nonbiologics and biologics.

Both drugs were well tolerated, with no unanticipated adverse events. Through week 44, the discontinuation rates were 5% for guselkumab and 9% for secukinumab. Adverse events were common in both arms (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively). Serious adverse events occurred in 6.2% and 7.2%, respectively. These included serious infections in six patients taking guselkumab and five taking secukinumab. Superficial Candida infections occurred in 2% of the guselkumab group and 5.7% of the secukinumab group; Tinea infections occurred in 1.7% and 4.5%, respectively.

The session was sponsored by Janssen, the manufacturer of guselkumab (Tremfya). Dr. Sobell is a consultant for Janssen and also disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma. Secukinumab is marketed as Cosentyx.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Guselkumab bested secukinumab in a 48-week-long study of plaque psoriasis, with 84.5% of patients on the interleukin (IL)-23 blocker hitting at least a 90% improvement in their Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), compared with 70% of those taking secukinumab, which blocks IL-17.

The drug was numerically, but not significantly, better than secukinumab in the PASI 75 response at weeks 12 and 48 (84.6% for guselkumab at both time points vs. 80.2% for secukinumab at both time points). This finding on the primary secondary endpoint knocked the P values of the other five into “nominally significant” ranges. But the responses were still good enough for researchers to tag guselkumab as noninferior to its competitor, Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The difference also speaks to the difference in the drugs’ onset of action and its peak efficacy, said Dr. Sobell, of the department of dermatology at Tufts University, Boston.

“In both groups, the PASI 90 increased similarly in the first month,” to about 20%, he commented. “But at week 12 and after, it was consistently higher in guselkumab, peaking around week 28. Secukinumab peaked around weeks 16 to 20 and then slowly declined.”

Despite not being statistically significant, the other secondary efficacy endpoints were certainly enough to pique the audience’s attention. At week 48, guselkumab topped secukinumab in both PASI 100 (58.2% vs. 48.4%, respectively) and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 0 (62.2% vs. 50.4%) and 0-1 (85% vs. 74.9%).

ECLIPSE randomized 1,048 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis to 100-mg subcutaneous guselkumab at weeks 0, 4, and 12, followed by dosing every 8 weeks, or to 300-mg subcutaneous secukinumab administered by two subcutaneous injections of 150 mg at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, followed by dosing every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 90 response at week 48. Secondary endpoints were assessed at weeks 12 and 48, with safety monitoring through week 56.

The mean baseline Body Surface Area score was 24, and the mean PASI score was 20. Patients had already been treated with phototherapy (51.8%), nonbiologic systemic medications (53.7%), and biologics (29%). About 37% were naive to both nonbiologics and biologics.

Both drugs were well tolerated, with no unanticipated adverse events. Through week 44, the discontinuation rates were 5% for guselkumab and 9% for secukinumab. Adverse events were common in both arms (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively). Serious adverse events occurred in 6.2% and 7.2%, respectively. These included serious infections in six patients taking guselkumab and five taking secukinumab. Superficial Candida infections occurred in 2% of the guselkumab group and 5.7% of the secukinumab group; Tinea infections occurred in 1.7% and 4.5%, respectively.

The session was sponsored by Janssen, the manufacturer of guselkumab (Tremfya). Dr. Sobell is a consultant for Janssen and also disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma. Secukinumab is marketed as Cosentyx.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Guselkumab bested secukinumab in a 48-week-long study of plaque psoriasis, with 84.5% of patients on the interleukin (IL)-23 blocker hitting at least a 90% improvement in their Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), compared with 70% of those taking secukinumab, which blocks IL-17.

The drug was numerically, but not significantly, better than secukinumab in the PASI 75 response at weeks 12 and 48 (84.6% for guselkumab at both time points vs. 80.2% for secukinumab at both time points). This finding on the primary secondary endpoint knocked the P values of the other five into “nominally significant” ranges. But the responses were still good enough for researchers to tag guselkumab as noninferior to its competitor, Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The difference also speaks to the difference in the drugs’ onset of action and its peak efficacy, said Dr. Sobell, of the department of dermatology at Tufts University, Boston.

“In both groups, the PASI 90 increased similarly in the first month,” to about 20%, he commented. “But at week 12 and after, it was consistently higher in guselkumab, peaking around week 28. Secukinumab peaked around weeks 16 to 20 and then slowly declined.”

Despite not being statistically significant, the other secondary efficacy endpoints were certainly enough to pique the audience’s attention. At week 48, guselkumab topped secukinumab in both PASI 100 (58.2% vs. 48.4%, respectively) and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 0 (62.2% vs. 50.4%) and 0-1 (85% vs. 74.9%).

ECLIPSE randomized 1,048 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis to 100-mg subcutaneous guselkumab at weeks 0, 4, and 12, followed by dosing every 8 weeks, or to 300-mg subcutaneous secukinumab administered by two subcutaneous injections of 150 mg at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, followed by dosing every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 90 response at week 48. Secondary endpoints were assessed at weeks 12 and 48, with safety monitoring through week 56.

The mean baseline Body Surface Area score was 24, and the mean PASI score was 20. Patients had already been treated with phototherapy (51.8%), nonbiologic systemic medications (53.7%), and biologics (29%). About 37% were naive to both nonbiologics and biologics.

Both drugs were well tolerated, with no unanticipated adverse events. Through week 44, the discontinuation rates were 5% for guselkumab and 9% for secukinumab. Adverse events were common in both arms (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively). Serious adverse events occurred in 6.2% and 7.2%, respectively. These included serious infections in six patients taking guselkumab and five taking secukinumab. Superficial Candida infections occurred in 2% of the guselkumab group and 5.7% of the secukinumab group; Tinea infections occurred in 1.7% and 4.5%, respectively.

The session was sponsored by Janssen, the manufacturer of guselkumab (Tremfya). Dr. Sobell is a consultant for Janssen and also disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma. Secukinumab is marketed as Cosentyx.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

REPORTING FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Guselkumab outperformed secukinumab for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Major finding: PASI 90 was achieved in 84.5% of patients on guselkumab and 70% on secukinumab.

Study details: The phase 3 study randomized 1,048 patients to guselkumab or secukinumab.

Disclosures: The session was sponsored by Janssen, the manufacturer of guselkumab (Tremfya). Dr. Sobell is a consultant for Janssen and also disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

Isotretinoin treatment reorganizes dermal microbiome in acne patients

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Isotretinoin, the go-to guy for severe acne, may not be so much a local cop as a community organizer, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It now appears that with and that the microbial community is replenished with the types associated with healthy skin,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. When these new bacteria move in, they push pathogenic species out of the neighborhood “and create a new skin microbial community. Maybe this is the real reason our patients tend to stay better, once we get them better with isotretinoin.”

Dr. Gordon discussed new data published last October in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology (J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.023). In a letter to the editor, William H. McCoy, IV, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and his associates suggest that isotretinoin induces a “sebaceous drought,” which shifts the skin microbiome from pathogenic to normophysiological.

Isotretinoin is the gold standard treatment for severe acne, but its method of action has never been fully elucidated, Dr. Gordon said. It clearly targets the sebaceous gland – decreasing sebocyte proliferation and suppressing sebum production – but an emerging body of research suggests that the drug also markedly affects dermal microbial colonization.

The entire concept of a skin microbiome is nearly as new as this new concept of isotretinoin’s effect upon it. Only in the last few years have researchers begun to characterize the complex microbial film that keeps skin healthy and resistant to infection. Dermal dysbiosis has now been associated with acne, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and atopic dermatitis.

The 2-year pilot study compared the dermal microbiome of isotretinoin-treated acne patients with that of patients with untreated acne and normal skin. Skin samples underwent genomic analysis before isotretinoin treatment, at several periods during treatment, and about 5 months after treatment stopped. Untreated controls were evaluated at baseline and at 2, 5, and 10 months.

Not surprisingly, before treatment the microbiome was similar in both acne groups, but markedly different from that seen in normal skin. As isotretinoin’s “oil drought” dragged on, levels of Cutibacterium acnes (the new appellation for P. acnes) declined. Staphylococcus species initially increased, but then declined as well. Simultaneously, four new taxa (Rothia, Flavobacterium, Enterobacter, and Micrococcus) increased. Most patients had a restructuring of their Propionibacterium community, populated largely by the less-pathogenic strains found on normal skin.

“We suggest that isotretinoin creates a Propionibacterium ‘population bottleneck’ that selects for ‘healthy’ Propionibacterium communities and other sebaceous skin taxa that persist after treatment, resulting in long-term acne remission [i.e., normal skin],” the investigators wrote.

This is a new and very exciting finding, Dr. Gordon commented. “It appears that the reason our isotretinoin patients stay better once they get better is not from targeting the sebaceous gland itself, but by repairing the skin’s microbiome and getting it back to normal.”

Dr. Gordon reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Isotretinoin, the go-to guy for severe acne, may not be so much a local cop as a community organizer, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It now appears that with and that the microbial community is replenished with the types associated with healthy skin,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. When these new bacteria move in, they push pathogenic species out of the neighborhood “and create a new skin microbial community. Maybe this is the real reason our patients tend to stay better, once we get them better with isotretinoin.”

Dr. Gordon discussed new data published last October in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology (J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.023). In a letter to the editor, William H. McCoy, IV, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and his associates suggest that isotretinoin induces a “sebaceous drought,” which shifts the skin microbiome from pathogenic to normophysiological.

Isotretinoin is the gold standard treatment for severe acne, but its method of action has never been fully elucidated, Dr. Gordon said. It clearly targets the sebaceous gland – decreasing sebocyte proliferation and suppressing sebum production – but an emerging body of research suggests that the drug also markedly affects dermal microbial colonization.

The entire concept of a skin microbiome is nearly as new as this new concept of isotretinoin’s effect upon it. Only in the last few years have researchers begun to characterize the complex microbial film that keeps skin healthy and resistant to infection. Dermal dysbiosis has now been associated with acne, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and atopic dermatitis.

The 2-year pilot study compared the dermal microbiome of isotretinoin-treated acne patients with that of patients with untreated acne and normal skin. Skin samples underwent genomic analysis before isotretinoin treatment, at several periods during treatment, and about 5 months after treatment stopped. Untreated controls were evaluated at baseline and at 2, 5, and 10 months.

Not surprisingly, before treatment the microbiome was similar in both acne groups, but markedly different from that seen in normal skin. As isotretinoin’s “oil drought” dragged on, levels of Cutibacterium acnes (the new appellation for P. acnes) declined. Staphylococcus species initially increased, but then declined as well. Simultaneously, four new taxa (Rothia, Flavobacterium, Enterobacter, and Micrococcus) increased. Most patients had a restructuring of their Propionibacterium community, populated largely by the less-pathogenic strains found on normal skin.

“We suggest that isotretinoin creates a Propionibacterium ‘population bottleneck’ that selects for ‘healthy’ Propionibacterium communities and other sebaceous skin taxa that persist after treatment, resulting in long-term acne remission [i.e., normal skin],” the investigators wrote.

This is a new and very exciting finding, Dr. Gordon commented. “It appears that the reason our isotretinoin patients stay better once they get better is not from targeting the sebaceous gland itself, but by repairing the skin’s microbiome and getting it back to normal.”

Dr. Gordon reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – Isotretinoin, the go-to guy for severe acne, may not be so much a local cop as a community organizer, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It now appears that with and that the microbial community is replenished with the types associated with healthy skin,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. When these new bacteria move in, they push pathogenic species out of the neighborhood “and create a new skin microbial community. Maybe this is the real reason our patients tend to stay better, once we get them better with isotretinoin.”

Dr. Gordon discussed new data published last October in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology (J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.023). In a letter to the editor, William H. McCoy, IV, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and his associates suggest that isotretinoin induces a “sebaceous drought,” which shifts the skin microbiome from pathogenic to normophysiological.

Isotretinoin is the gold standard treatment for severe acne, but its method of action has never been fully elucidated, Dr. Gordon said. It clearly targets the sebaceous gland – decreasing sebocyte proliferation and suppressing sebum production – but an emerging body of research suggests that the drug also markedly affects dermal microbial colonization.

The entire concept of a skin microbiome is nearly as new as this new concept of isotretinoin’s effect upon it. Only in the last few years have researchers begun to characterize the complex microbial film that keeps skin healthy and resistant to infection. Dermal dysbiosis has now been associated with acne, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and atopic dermatitis.

The 2-year pilot study compared the dermal microbiome of isotretinoin-treated acne patients with that of patients with untreated acne and normal skin. Skin samples underwent genomic analysis before isotretinoin treatment, at several periods during treatment, and about 5 months after treatment stopped. Untreated controls were evaluated at baseline and at 2, 5, and 10 months.

Not surprisingly, before treatment the microbiome was similar in both acne groups, but markedly different from that seen in normal skin. As isotretinoin’s “oil drought” dragged on, levels of Cutibacterium acnes (the new appellation for P. acnes) declined. Staphylococcus species initially increased, but then declined as well. Simultaneously, four new taxa (Rothia, Flavobacterium, Enterobacter, and Micrococcus) increased. Most patients had a restructuring of their Propionibacterium community, populated largely by the less-pathogenic strains found on normal skin.

“We suggest that isotretinoin creates a Propionibacterium ‘population bottleneck’ that selects for ‘healthy’ Propionibacterium communities and other sebaceous skin taxa that persist after treatment, resulting in long-term acne remission [i.e., normal skin],” the investigators wrote.

This is a new and very exciting finding, Dr. Gordon commented. “It appears that the reason our isotretinoin patients stay better once they get better is not from targeting the sebaceous gland itself, but by repairing the skin’s microbiome and getting it back to normal.”

Dr. Gordon reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

REPORTING FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Products being developed for AKs therapy may appeal to patients

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – It’s unanimous: Patients with actinic keratoses (AKs) want them to go away quickly, painlessly, and pretty much invisibly. In fact, they’d rather risk developing cancer than deal with weeks of painful, red, oozing crusts.

But unless Ronco comes up with the AK-Away Wand, dermatologists and patients have to face facts, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Some AKs are going to just go away, and some are going to just sit there unchanging. Not all AKs are going to turn into squamous cell cancer. But you can’t tell which ones will, and because you can’t predict, they should all be treated. It’s our job to make patients care about this.”

That job starts with the very first conversation, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology, Baylor University, Houston. “The way you frame the information at the very beginning is so important. You have to get the word ‘cancer’ in there.”

Most patients don’t fully grasp the serious threat that a transformed AK can pose, as illustrated by a survey of patients at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa.. The survey also highlighted the importance of the first discussion with the physician. Almost 550 dermatology clinic patients completed the survey, which presented five AK treatment decision scenarios, asking patients how likely they would be to pursue treatment in each situation (JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153[5]:421-6). Each scenario was factual, but the emphasis on facts varied. The first four questions characterized the lesions as sun damage and stressed the low incidence of malignant transformation (0.5%), and the large percentage that remain unchanged (75%) and spontaneously disappear (25%).

The last question was much simpler and more direct: “Actinic keratoses are precancers. Based on this statement, how likely are you to want treatment?”

“When AK was presented without the word ‘cancer’ in the description, there were lower proportions of individuals who said they would want to receive treatment [about 60%],” Dr. Rosen said. “Presenting AK as a precancer had the highest proportion of patients saying they would prefer treatment – about 92%.”

But current treatments aren’t ideal, at least from the standpoint of patients who prefer fast results with a minimum of erythema, oozing, crusting, and pain. Dr. Rosen looked into his crystal ball and saw a few encouraging treatment options coming down the drug development pike. To make it past regulatory hurdles, though, any new treatment has to hit the sweet spot of approximately 80% lesion clearance, with less than 40% recurrence at 1 year. Whether these investigational protocols can complete that journey remains to be seen.

VDA-1102

VDA-1102, in an ointment formulation, is based on a stress response chemical found in the jasmine plant. It contains a synthetic derivative of methyl jasmonate, a plant stress hormone found in jasmine. According to the patent record for VDA-1102, jasmonates are released in extreme ultraviolet radiation, osmotic shock, heat shock, and pathogen attack to initiate injury response and repair cascades.

The drug stops tumor growth by inhibiting glycolysis; it removes hexokinase 2 (HK2) from mitochondria. HK2 is found only in malignant cells; normal cells have the hexokinase 1 variant. Hexokinase is a key modulator of the transformation of adenosine triphosphate to adenosine diphosphate. As an HK2 modulator, VDA-1102 should, therefore, only induce apoptosis in the malignant cells, Dr. Rosen said.

“In preclinical studies in a hairless mouse model, they were approaching that 80% mark with lesion regression.” But the drug doesn’t induce necrosis or inflammation – a huge plus for patients. “There’s almost nothing in terms of redness, scaling, inflammation, or pain. This could be a really attractive addition to the AK toolkit. Improved aesthetics during treatment translates into improved patient willingness to undergo recurrent treatments. It may also be useful for treating large fields of AK, and in immunosuppressed patients.”

An Israeli company, Vidac Pharma, is conducting a phase 2b study of 150 patients with AK. The big question? Duration of effect – something that can’t be determined in the 21-week study. The company is aiming to launch a phase 3 trial next year.

KX-01

KX-01 (formerly KX2-391), being developed by Athenex, is a dual-action anticancer agent compounded into a 1% ointment. It inhibits both Src kinase and tubulin polymerization. Src regulates several signaling pathways in tumor cells, including proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis. Tubulin formation is critical for cell replication: Without tubulin polymerization, mitotic spindles can’t form.

The drug passed two phase 3 studies (NCT03285477 and NCT03285490) with flying colors last year, clearing 100% of AK lesions by day 57 when used as field therapy on the head and neck. The studies comprised 702 subjects who applied the active ointment or vehicle once daily for 5 days.

“Local skin reactions were very low and resolved very quickly,” Dr. Rosen said. “But we don’t have any longterm data yet ... we need the 1-year clearance rate to see if it falls in that 40% sweet spot.”

Dr. Rosen disclosed being a consultant for Valeant (Ortho) and Cutanea Life Sciences.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – It’s unanimous: Patients with actinic keratoses (AKs) want them to go away quickly, painlessly, and pretty much invisibly. In fact, they’d rather risk developing cancer than deal with weeks of painful, red, oozing crusts.

But unless Ronco comes up with the AK-Away Wand, dermatologists and patients have to face facts, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Some AKs are going to just go away, and some are going to just sit there unchanging. Not all AKs are going to turn into squamous cell cancer. But you can’t tell which ones will, and because you can’t predict, they should all be treated. It’s our job to make patients care about this.”

That job starts with the very first conversation, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology, Baylor University, Houston. “The way you frame the information at the very beginning is so important. You have to get the word ‘cancer’ in there.”

Most patients don’t fully grasp the serious threat that a transformed AK can pose, as illustrated by a survey of patients at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa.. The survey also highlighted the importance of the first discussion with the physician. Almost 550 dermatology clinic patients completed the survey, which presented five AK treatment decision scenarios, asking patients how likely they would be to pursue treatment in each situation (JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153[5]:421-6). Each scenario was factual, but the emphasis on facts varied. The first four questions characterized the lesions as sun damage and stressed the low incidence of malignant transformation (0.5%), and the large percentage that remain unchanged (75%) and spontaneously disappear (25%).

The last question was much simpler and more direct: “Actinic keratoses are precancers. Based on this statement, how likely are you to want treatment?”

“When AK was presented without the word ‘cancer’ in the description, there were lower proportions of individuals who said they would want to receive treatment [about 60%],” Dr. Rosen said. “Presenting AK as a precancer had the highest proportion of patients saying they would prefer treatment – about 92%.”

But current treatments aren’t ideal, at least from the standpoint of patients who prefer fast results with a minimum of erythema, oozing, crusting, and pain. Dr. Rosen looked into his crystal ball and saw a few encouraging treatment options coming down the drug development pike. To make it past regulatory hurdles, though, any new treatment has to hit the sweet spot of approximately 80% lesion clearance, with less than 40% recurrence at 1 year. Whether these investigational protocols can complete that journey remains to be seen.

VDA-1102

VDA-1102, in an ointment formulation, is based on a stress response chemical found in the jasmine plant. It contains a synthetic derivative of methyl jasmonate, a plant stress hormone found in jasmine. According to the patent record for VDA-1102, jasmonates are released in extreme ultraviolet radiation, osmotic shock, heat shock, and pathogen attack to initiate injury response and repair cascades.

The drug stops tumor growth by inhibiting glycolysis; it removes hexokinase 2 (HK2) from mitochondria. HK2 is found only in malignant cells; normal cells have the hexokinase 1 variant. Hexokinase is a key modulator of the transformation of adenosine triphosphate to adenosine diphosphate. As an HK2 modulator, VDA-1102 should, therefore, only induce apoptosis in the malignant cells, Dr. Rosen said.

“In preclinical studies in a hairless mouse model, they were approaching that 80% mark with lesion regression.” But the drug doesn’t induce necrosis or inflammation – a huge plus for patients. “There’s almost nothing in terms of redness, scaling, inflammation, or pain. This could be a really attractive addition to the AK toolkit. Improved aesthetics during treatment translates into improved patient willingness to undergo recurrent treatments. It may also be useful for treating large fields of AK, and in immunosuppressed patients.”

An Israeli company, Vidac Pharma, is conducting a phase 2b study of 150 patients with AK. The big question? Duration of effect – something that can’t be determined in the 21-week study. The company is aiming to launch a phase 3 trial next year.

KX-01

KX-01 (formerly KX2-391), being developed by Athenex, is a dual-action anticancer agent compounded into a 1% ointment. It inhibits both Src kinase and tubulin polymerization. Src regulates several signaling pathways in tumor cells, including proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis. Tubulin formation is critical for cell replication: Without tubulin polymerization, mitotic spindles can’t form.

The drug passed two phase 3 studies (NCT03285477 and NCT03285490) with flying colors last year, clearing 100% of AK lesions by day 57 when used as field therapy on the head and neck. The studies comprised 702 subjects who applied the active ointment or vehicle once daily for 5 days.

“Local skin reactions were very low and resolved very quickly,” Dr. Rosen said. “But we don’t have any longterm data yet ... we need the 1-year clearance rate to see if it falls in that 40% sweet spot.”

Dr. Rosen disclosed being a consultant for Valeant (Ortho) and Cutanea Life Sciences.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – It’s unanimous: Patients with actinic keratoses (AKs) want them to go away quickly, painlessly, and pretty much invisibly. In fact, they’d rather risk developing cancer than deal with weeks of painful, red, oozing crusts.

But unless Ronco comes up with the AK-Away Wand, dermatologists and patients have to face facts, Theodore Rosen, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Some AKs are going to just go away, and some are going to just sit there unchanging. Not all AKs are going to turn into squamous cell cancer. But you can’t tell which ones will, and because you can’t predict, they should all be treated. It’s our job to make patients care about this.”

That job starts with the very first conversation, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology, Baylor University, Houston. “The way you frame the information at the very beginning is so important. You have to get the word ‘cancer’ in there.”

Most patients don’t fully grasp the serious threat that a transformed AK can pose, as illustrated by a survey of patients at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa.. The survey also highlighted the importance of the first discussion with the physician. Almost 550 dermatology clinic patients completed the survey, which presented five AK treatment decision scenarios, asking patients how likely they would be to pursue treatment in each situation (JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153[5]:421-6). Each scenario was factual, but the emphasis on facts varied. The first four questions characterized the lesions as sun damage and stressed the low incidence of malignant transformation (0.5%), and the large percentage that remain unchanged (75%) and spontaneously disappear (25%).

The last question was much simpler and more direct: “Actinic keratoses are precancers. Based on this statement, how likely are you to want treatment?”

“When AK was presented without the word ‘cancer’ in the description, there were lower proportions of individuals who said they would want to receive treatment [about 60%],” Dr. Rosen said. “Presenting AK as a precancer had the highest proportion of patients saying they would prefer treatment – about 92%.”

But current treatments aren’t ideal, at least from the standpoint of patients who prefer fast results with a minimum of erythema, oozing, crusting, and pain. Dr. Rosen looked into his crystal ball and saw a few encouraging treatment options coming down the drug development pike. To make it past regulatory hurdles, though, any new treatment has to hit the sweet spot of approximately 80% lesion clearance, with less than 40% recurrence at 1 year. Whether these investigational protocols can complete that journey remains to be seen.

VDA-1102

VDA-1102, in an ointment formulation, is based on a stress response chemical found in the jasmine plant. It contains a synthetic derivative of methyl jasmonate, a plant stress hormone found in jasmine. According to the patent record for VDA-1102, jasmonates are released in extreme ultraviolet radiation, osmotic shock, heat shock, and pathogen attack to initiate injury response and repair cascades.

The drug stops tumor growth by inhibiting glycolysis; it removes hexokinase 2 (HK2) from mitochondria. HK2 is found only in malignant cells; normal cells have the hexokinase 1 variant. Hexokinase is a key modulator of the transformation of adenosine triphosphate to adenosine diphosphate. As an HK2 modulator, VDA-1102 should, therefore, only induce apoptosis in the malignant cells, Dr. Rosen said.

“In preclinical studies in a hairless mouse model, they were approaching that 80% mark with lesion regression.” But the drug doesn’t induce necrosis or inflammation – a huge plus for patients. “There’s almost nothing in terms of redness, scaling, inflammation, or pain. This could be a really attractive addition to the AK toolkit. Improved aesthetics during treatment translates into improved patient willingness to undergo recurrent treatments. It may also be useful for treating large fields of AK, and in immunosuppressed patients.”

An Israeli company, Vidac Pharma, is conducting a phase 2b study of 150 patients with AK. The big question? Duration of effect – something that can’t be determined in the 21-week study. The company is aiming to launch a phase 3 trial next year.

KX-01

KX-01 (formerly KX2-391), being developed by Athenex, is a dual-action anticancer agent compounded into a 1% ointment. It inhibits both Src kinase and tubulin polymerization. Src regulates several signaling pathways in tumor cells, including proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis. Tubulin formation is critical for cell replication: Without tubulin polymerization, mitotic spindles can’t form.

The drug passed two phase 3 studies (NCT03285477 and NCT03285490) with flying colors last year, clearing 100% of AK lesions by day 57 when used as field therapy on the head and neck. The studies comprised 702 subjects who applied the active ointment or vehicle once daily for 5 days.

“Local skin reactions were very low and resolved very quickly,” Dr. Rosen said. “But we don’t have any longterm data yet ... we need the 1-year clearance rate to see if it falls in that 40% sweet spot.”

Dr. Rosen disclosed being a consultant for Valeant (Ortho) and Cutanea Life Sciences.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Choose your steps for treating chronic spontaneous urticaria

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”

Drug choice is largely physician preference. A 2014 Cochrane review examined 73 studies of H1-histamine blockers in 9,759 participants and found little difference between any of the drugs. “No single H1‐antihistamine stands out as most effective,” the authors concluded. “Cetirizine at 10 mg once daily in the short term and in the intermediate term was found to be effective in completely suppressing urticaria. Evidence is limited for desloratadine given at 5 mg once daily in the intermediate term and at 20 mg in the short term. Levocetirizine at 5 mg in the intermediate but not short term was effective for complete suppression. Levocetirizine 20 mg was effective in the short term, but 10 mg was not,” the study noted (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 14;[11]:CD006137).

“In my practice, we use cetirizine,” Dr. Baker said. “But if a patient is on fexofenadine, for example, and doing well, I wouldn’t change that.”

The treatment guidelines agree on the next step for unresponsive patients: Updosing the antihistamine. “You may have to jump up to four times the recommended dose,” she said. “Sometimes we do this gradually, but sometimes I go right ahead to that dose just to get the patient under control. And there’s good evidence that 50%-75% of our patients will be controlled on an updosing regimen. Just keep them on it until they are symptom free, and then you can try reducing it to see how they do.”

But even this can leave up to half of patients still itching. The next treatment step is where the guidelines diverge, Dr. Baker said. The U.S. document suggests trying several other options, including adding another second-generation antihistamine, adding an H2 agonist, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, or a sedating first-generation antihistamine.

“The European recommendation is to go straight to omalizumab,” Dr. Baker said. “They based this recommendation on the finding of insufficient evidence in the literature for any of these other things.”

Instead of recommending omalizumab to antihistamine-resistant patients, the U.S. guidelines suggest a dose-advancement trial of hydroxyzine or doxepin.

But there’s no arguing that omalizumab is highly effective for chronic urticaria, Dr. Baker noted. The 2015 ASTERIA trial perfectly illustrated the drug’s benefit for patients who were still symptomatic on optimal antihistamine treatment (J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jan;135[1]:67-75).

The 40-week, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study enrolled 319 patients, who received the injections as a monthly add-on therapy for 24 weeks in doses of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg or placebo. This was followed by 16 weeks of observation. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in weekly Itch Severity Score (ISS) at week 12.

The omalizumab 300-mg group had the best ISS scores at the end of the study. This group also met nine secondary endpoints, including a decreased time to reach the clinically important response of at least a 5-point ISS decrease.

The drug carries a low risk of adverse events, with just four patients (5%) in the omalizumab 300-mg group developing a serious side effect; none of these were judged to be related to the study drug. There is a very low risk of anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab – about 0.1% in clinical trials and 0.2% in postmarketing observational studies. A 2017 review of three omalizumab studies determined that asthma is the biggest risk factor for such a reaction.

The review found 132 patients with potential anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab. Asthma was the indication for omalizumab therapy in 80%; 43% of patients who provided an anaphylaxis history said that they had experienced a prior non–omalizumab-related reaction.

The U.S. guidelines don’t bring omalizumab into the picture until the final step, which recommends it, cyclosporine, or other unspecified biologics or immunosuppressive agents. At this point, however, the European guidelines move to a cyclosporine recommendation for the very small number of patients who were unresponsive to omalizumab.

Pivotal trials of omalizumab in urticaria used a once-monthly injection schedule, but more recent data suggest that patients who get the drug every 2 weeks may do better, Dr. Baker added. A chart review published in 2016 found a 100% response rate in patients who received twice monthly doses of 300 mg (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74[6]:1274-6).

Dr. Baker disclosed that she has been a clinical trial investigator for Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”

Drug choice is largely physician preference. A 2014 Cochrane review examined 73 studies of H1-histamine blockers in 9,759 participants and found little difference between any of the drugs. “No single H1‐antihistamine stands out as most effective,” the authors concluded. “Cetirizine at 10 mg once daily in the short term and in the intermediate term was found to be effective in completely suppressing urticaria. Evidence is limited for desloratadine given at 5 mg once daily in the intermediate term and at 20 mg in the short term. Levocetirizine at 5 mg in the intermediate but not short term was effective for complete suppression. Levocetirizine 20 mg was effective in the short term, but 10 mg was not,” the study noted (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 14;[11]:CD006137).

“In my practice, we use cetirizine,” Dr. Baker said. “But if a patient is on fexofenadine, for example, and doing well, I wouldn’t change that.”

The treatment guidelines agree on the next step for unresponsive patients: Updosing the antihistamine. “You may have to jump up to four times the recommended dose,” she said. “Sometimes we do this gradually, but sometimes I go right ahead to that dose just to get the patient under control. And there’s good evidence that 50%-75% of our patients will be controlled on an updosing regimen. Just keep them on it until they are symptom free, and then you can try reducing it to see how they do.”

But even this can leave up to half of patients still itching. The next treatment step is where the guidelines diverge, Dr. Baker said. The U.S. document suggests trying several other options, including adding another second-generation antihistamine, adding an H2 agonist, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, or a sedating first-generation antihistamine.

“The European recommendation is to go straight to omalizumab,” Dr. Baker said. “They based this recommendation on the finding of insufficient evidence in the literature for any of these other things.”

Instead of recommending omalizumab to antihistamine-resistant patients, the U.S. guidelines suggest a dose-advancement trial of hydroxyzine or doxepin.

But there’s no arguing that omalizumab is highly effective for chronic urticaria, Dr. Baker noted. The 2015 ASTERIA trial perfectly illustrated the drug’s benefit for patients who were still symptomatic on optimal antihistamine treatment (J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jan;135[1]:67-75).

The 40-week, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study enrolled 319 patients, who received the injections as a monthly add-on therapy for 24 weeks in doses of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg or placebo. This was followed by 16 weeks of observation. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in weekly Itch Severity Score (ISS) at week 12.

The omalizumab 300-mg group had the best ISS scores at the end of the study. This group also met nine secondary endpoints, including a decreased time to reach the clinically important response of at least a 5-point ISS decrease.

The drug carries a low risk of adverse events, with just four patients (5%) in the omalizumab 300-mg group developing a serious side effect; none of these were judged to be related to the study drug. There is a very low risk of anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab – about 0.1% in clinical trials and 0.2% in postmarketing observational studies. A 2017 review of three omalizumab studies determined that asthma is the biggest risk factor for such a reaction.

The review found 132 patients with potential anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab. Asthma was the indication for omalizumab therapy in 80%; 43% of patients who provided an anaphylaxis history said that they had experienced a prior non–omalizumab-related reaction.

The U.S. guidelines don’t bring omalizumab into the picture until the final step, which recommends it, cyclosporine, or other unspecified biologics or immunosuppressive agents. At this point, however, the European guidelines move to a cyclosporine recommendation for the very small number of patients who were unresponsive to omalizumab.

Pivotal trials of omalizumab in urticaria used a once-monthly injection schedule, but more recent data suggest that patients who get the drug every 2 weeks may do better, Dr. Baker added. A chart review published in 2016 found a 100% response rate in patients who received twice monthly doses of 300 mg (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74[6]:1274-6).

Dr. Baker disclosed that she has been a clinical trial investigator for Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”