User login

Strict OR attire policy had no impact on SSI rate

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of strict operating room (OR) attire policies did not reduce the rates of superficial surgical site infections (SSIs), according to an analysis of more than 6,500 patients.

“SSIs are the most common cause of health care–associated infections in the U.S.,” study author Sandra Farach, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “It’s estimated that SSIs occur in 2%-5% of patients undergoing inpatient surgery. They’re associated with significant patient morbidity and mortality and are a significant burden to the health care system, accounting for an estimated $3.5 to $10 billion in health care expenditures.”

In February 2015, the Association for periOperative Registered Nurses published recommendations on operating room attire, providing a guideline for modifying facility policies and regulatory requirements. It included stringent policies designed to minimize the exposed areas of skin and hair of operating room staff. “New attire policies were met with some criticism as there is a paucity of evidence-based data to support these recommendations,” said Dr. Farach, who helped conduct the study during her tenure as chief resident of general surgery at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center.

A total of 6,517 patients were included in the analysis: 3,077 in the preimplementation group and 3,440 patients in the postimplementation group. The postimplementation group tended to be older and had significantly higher rates of hypertension, dialysis treatments, steroid use, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome, as well as higher American Society of Anesthesiologists classification scores. “However, they had a significantly lower BMI, incidence of smoking and COPD, and a higher incidence of clean wounds, which would theoretically leave them less exposed to SSIs,” said Dr. Farach, who is now a pediatric surgical critical care fellow at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis.

Overall, the rate of SSIs by wound class increased between the preimplementation and postimplementation time periods: The percent of change was 0.6%, 0.9%, 2.3%, and 3.8% in the clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty/infected cases, respectively. When the review was limited to clean or clean-contaminated cases, SSI increased slightly, from 0.7% to 0.8% (P = .085). There were no significant differences in the complication rate, 30-day mortality, unplanned return to the OR, or length of stay between preimplementation or postimplementation at either hospital.

When Dr. Farach and her associates examined the overall infection rate, they observed no significant differences preimplementation and postimplementation in the rates of incisional SSI (0.97% vs. 0.96%, respectively; P = .949), organ space SSI (1.20% vs. 0.81%; P = .115), and total SSIs (2.11% vs. 1.77%; P = .321). Multivariate analysis showed that implementation of OR changes was not associated with an increased risk of SSIs. Factors that did predict high SSI rates included preoperative SSI (adjusted odds ratio 23.04), long operative time (AOR 3.4), preoperative open wound (AOR 2.94), contaminated/dirty wound classes (AOR 2.32), and morbid obesity (AOR 1.8).

“A hypothetical analysis revealed that a sample of over 495,000 patients would be required to demonstrate a 10% incisional SSI reduction among patients with clean or clean-contaminated wounds,” Dr. Farach noted. “Nevertheless, the study showed a numerical increase in SSI during the study period. Policies regarding OR attire were universally unpopular. As a result, OR governance is now working to repeal these new policies at both hospitals.”

“Given the rarity of SSI in the population subset which is relevant to the OR attire question (clean and clean-contaminated wounds, 0.7%), designing a study to prove effectiveness of an intervention (i.e., a 10% improvement) is totally impractical to conduct as this would require nearly a half a million cases,” said Jacob Moalem, MD, the lead author of the study who is an endocrine surgeon at the University of Rochester. At the meeting, a discussant suggested that conducting such a study is feasible; however, “I would strongly argue that putting that many people through such a study, when we know that these attire rules have a deleterious effect on surgeon comfort and OR team dynamics and morale, would not be prudent,” Dr. Moalem said. “We know that surgeon comfort, ability to focus on the task at hand, and minimizing distractions in the OR are critically important in reducing errors. In my opinion, by continuing to focus on these unfounded attire restrictions, one would be far more likely to actually cause injury to a patient than to prevent a wound infection.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of strict operating room (OR) attire policies did not reduce the rates of superficial surgical site infections (SSIs), according to an analysis of more than 6,500 patients.

“SSIs are the most common cause of health care–associated infections in the U.S.,” study author Sandra Farach, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “It’s estimated that SSIs occur in 2%-5% of patients undergoing inpatient surgery. They’re associated with significant patient morbidity and mortality and are a significant burden to the health care system, accounting for an estimated $3.5 to $10 billion in health care expenditures.”

In February 2015, the Association for periOperative Registered Nurses published recommendations on operating room attire, providing a guideline for modifying facility policies and regulatory requirements. It included stringent policies designed to minimize the exposed areas of skin and hair of operating room staff. “New attire policies were met with some criticism as there is a paucity of evidence-based data to support these recommendations,” said Dr. Farach, who helped conduct the study during her tenure as chief resident of general surgery at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center.

A total of 6,517 patients were included in the analysis: 3,077 in the preimplementation group and 3,440 patients in the postimplementation group. The postimplementation group tended to be older and had significantly higher rates of hypertension, dialysis treatments, steroid use, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome, as well as higher American Society of Anesthesiologists classification scores. “However, they had a significantly lower BMI, incidence of smoking and COPD, and a higher incidence of clean wounds, which would theoretically leave them less exposed to SSIs,” said Dr. Farach, who is now a pediatric surgical critical care fellow at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis.

Overall, the rate of SSIs by wound class increased between the preimplementation and postimplementation time periods: The percent of change was 0.6%, 0.9%, 2.3%, and 3.8% in the clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty/infected cases, respectively. When the review was limited to clean or clean-contaminated cases, SSI increased slightly, from 0.7% to 0.8% (P = .085). There were no significant differences in the complication rate, 30-day mortality, unplanned return to the OR, or length of stay between preimplementation or postimplementation at either hospital.

When Dr. Farach and her associates examined the overall infection rate, they observed no significant differences preimplementation and postimplementation in the rates of incisional SSI (0.97% vs. 0.96%, respectively; P = .949), organ space SSI (1.20% vs. 0.81%; P = .115), and total SSIs (2.11% vs. 1.77%; P = .321). Multivariate analysis showed that implementation of OR changes was not associated with an increased risk of SSIs. Factors that did predict high SSI rates included preoperative SSI (adjusted odds ratio 23.04), long operative time (AOR 3.4), preoperative open wound (AOR 2.94), contaminated/dirty wound classes (AOR 2.32), and morbid obesity (AOR 1.8).

“A hypothetical analysis revealed that a sample of over 495,000 patients would be required to demonstrate a 10% incisional SSI reduction among patients with clean or clean-contaminated wounds,” Dr. Farach noted. “Nevertheless, the study showed a numerical increase in SSI during the study period. Policies regarding OR attire were universally unpopular. As a result, OR governance is now working to repeal these new policies at both hospitals.”

“Given the rarity of SSI in the population subset which is relevant to the OR attire question (clean and clean-contaminated wounds, 0.7%), designing a study to prove effectiveness of an intervention (i.e., a 10% improvement) is totally impractical to conduct as this would require nearly a half a million cases,” said Jacob Moalem, MD, the lead author of the study who is an endocrine surgeon at the University of Rochester. At the meeting, a discussant suggested that conducting such a study is feasible; however, “I would strongly argue that putting that many people through such a study, when we know that these attire rules have a deleterious effect on surgeon comfort and OR team dynamics and morale, would not be prudent,” Dr. Moalem said. “We know that surgeon comfort, ability to focus on the task at hand, and minimizing distractions in the OR are critically important in reducing errors. In my opinion, by continuing to focus on these unfounded attire restrictions, one would be far more likely to actually cause injury to a patient than to prevent a wound infection.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of strict operating room (OR) attire policies did not reduce the rates of superficial surgical site infections (SSIs), according to an analysis of more than 6,500 patients.

“SSIs are the most common cause of health care–associated infections in the U.S.,” study author Sandra Farach, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “It’s estimated that SSIs occur in 2%-5% of patients undergoing inpatient surgery. They’re associated with significant patient morbidity and mortality and are a significant burden to the health care system, accounting for an estimated $3.5 to $10 billion in health care expenditures.”

In February 2015, the Association for periOperative Registered Nurses published recommendations on operating room attire, providing a guideline for modifying facility policies and regulatory requirements. It included stringent policies designed to minimize the exposed areas of skin and hair of operating room staff. “New attire policies were met with some criticism as there is a paucity of evidence-based data to support these recommendations,” said Dr. Farach, who helped conduct the study during her tenure as chief resident of general surgery at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center.

A total of 6,517 patients were included in the analysis: 3,077 in the preimplementation group and 3,440 patients in the postimplementation group. The postimplementation group tended to be older and had significantly higher rates of hypertension, dialysis treatments, steroid use, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome, as well as higher American Society of Anesthesiologists classification scores. “However, they had a significantly lower BMI, incidence of smoking and COPD, and a higher incidence of clean wounds, which would theoretically leave them less exposed to SSIs,” said Dr. Farach, who is now a pediatric surgical critical care fellow at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis.

Overall, the rate of SSIs by wound class increased between the preimplementation and postimplementation time periods: The percent of change was 0.6%, 0.9%, 2.3%, and 3.8% in the clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty/infected cases, respectively. When the review was limited to clean or clean-contaminated cases, SSI increased slightly, from 0.7% to 0.8% (P = .085). There were no significant differences in the complication rate, 30-day mortality, unplanned return to the OR, or length of stay between preimplementation or postimplementation at either hospital.

When Dr. Farach and her associates examined the overall infection rate, they observed no significant differences preimplementation and postimplementation in the rates of incisional SSI (0.97% vs. 0.96%, respectively; P = .949), organ space SSI (1.20% vs. 0.81%; P = .115), and total SSIs (2.11% vs. 1.77%; P = .321). Multivariate analysis showed that implementation of OR changes was not associated with an increased risk of SSIs. Factors that did predict high SSI rates included preoperative SSI (adjusted odds ratio 23.04), long operative time (AOR 3.4), preoperative open wound (AOR 2.94), contaminated/dirty wound classes (AOR 2.32), and morbid obesity (AOR 1.8).

“A hypothetical analysis revealed that a sample of over 495,000 patients would be required to demonstrate a 10% incisional SSI reduction among patients with clean or clean-contaminated wounds,” Dr. Farach noted. “Nevertheless, the study showed a numerical increase in SSI during the study period. Policies regarding OR attire were universally unpopular. As a result, OR governance is now working to repeal these new policies at both hospitals.”

“Given the rarity of SSI in the population subset which is relevant to the OR attire question (clean and clean-contaminated wounds, 0.7%), designing a study to prove effectiveness of an intervention (i.e., a 10% improvement) is totally impractical to conduct as this would require nearly a half a million cases,” said Jacob Moalem, MD, the lead author of the study who is an endocrine surgeon at the University of Rochester. At the meeting, a discussant suggested that conducting such a study is feasible; however, “I would strongly argue that putting that many people through such a study, when we know that these attire rules have a deleterious effect on surgeon comfort and OR team dynamics and morale, would not be prudent,” Dr. Moalem said. “We know that surgeon comfort, ability to focus on the task at hand, and minimizing distractions in the OR are critically important in reducing errors. In my opinion, by continuing to focus on these unfounded attire restrictions, one would be far more likely to actually cause injury to a patient than to prevent a wound infection.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Implementation of stringent operating room attire policies do not reduce rates superficial surgical site infections (SSIs).

Major finding: The researchers observed no significant differences preimplementation and postimplementation of OR attire policies in the rates of incisional SSI (0.97 vs. 0.96, respectively; P = .949), organ space SSI (1.20 vs 0.81; P = .115), and total SSIs (2.11 vs. 1.77; P = .321).

Study details: A study of 6,517 patients who underwent surgery at two tertiary care teaching hospitals.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Early evidence shows that surgery can alter gut microbiome

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Junior surgical trainees hew closer to surgery risk calculators than do faculty members

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

DiaRem score predicts remission of type 2 diabetes after sleeve gastrectomy

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The DiaRem score is useful in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Major finding: Results of the DiaRem scores indicated that 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 162 patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Disclosures: Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: SBO in bariatric patient can mean internal herniation

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE ACS Clinical Congress

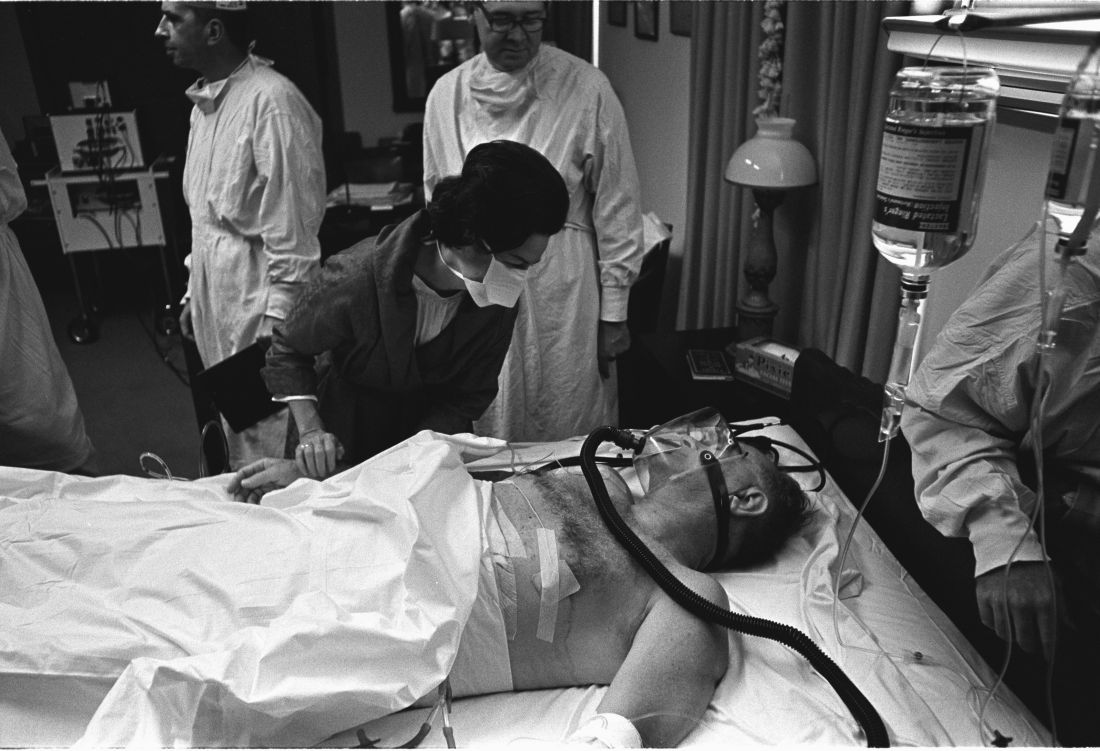

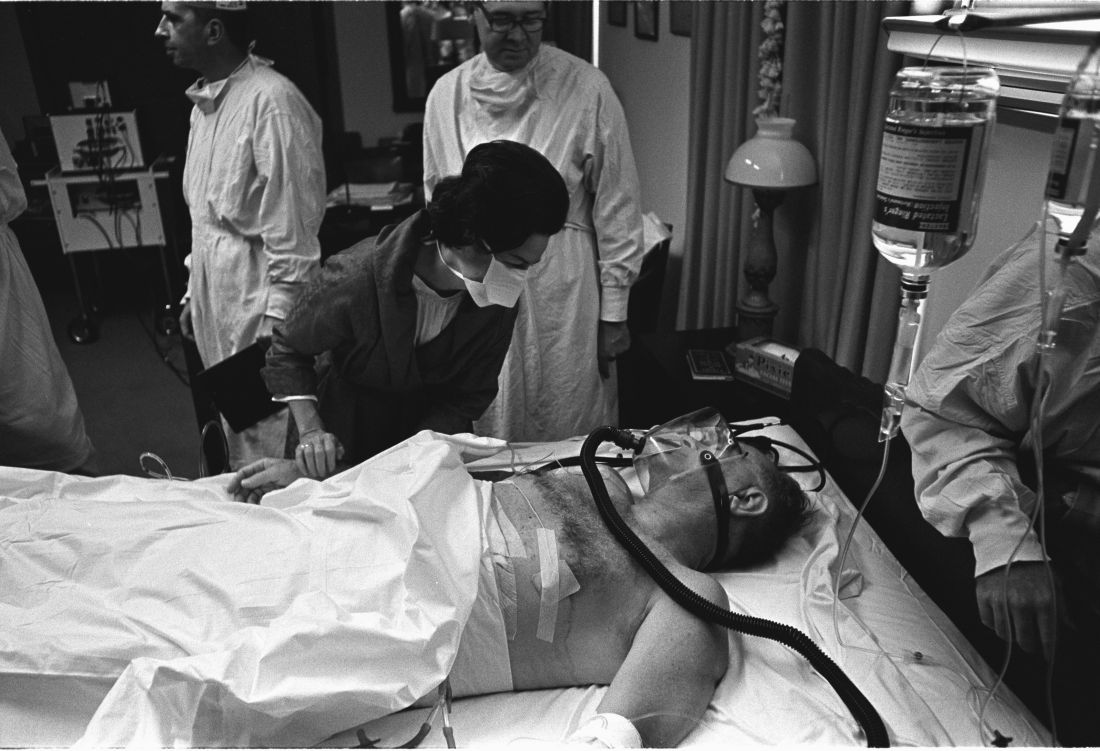

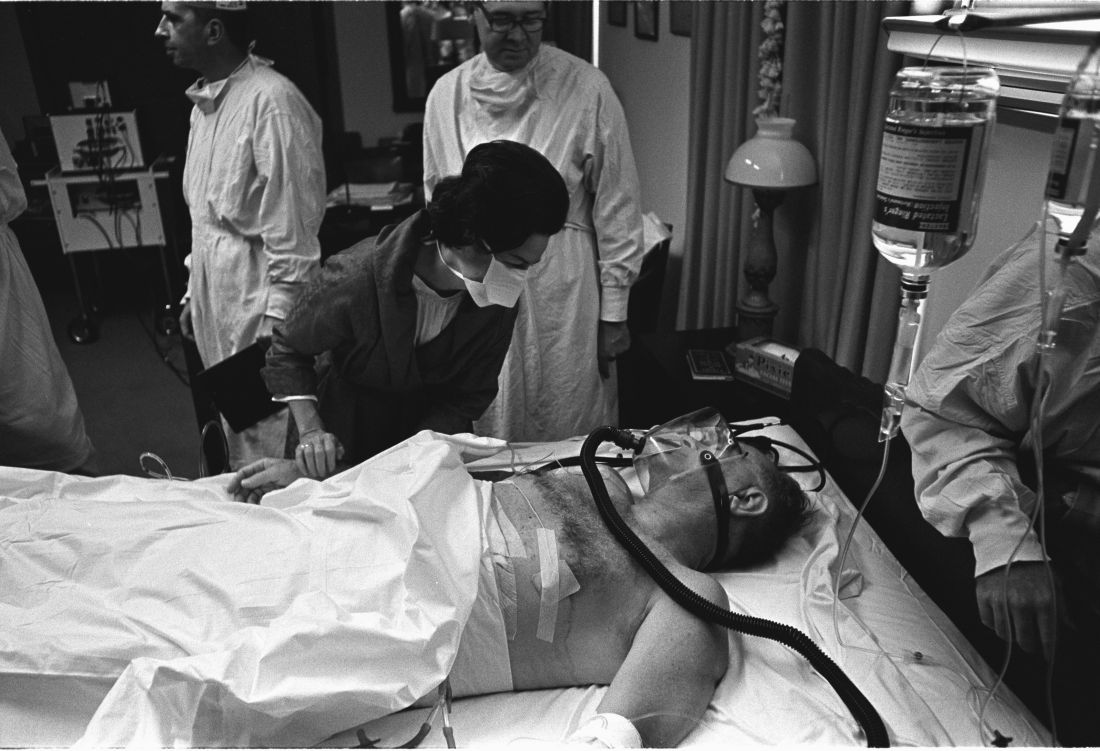

Surgeons paid a price for presidential procedures

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

VIDEO: When surgery hurts the surgeon: Intervening to prevent ergonomic injuries

SAN DIEGO – Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are practically inevitable for surgeons, eventually occurring in more than 90%, no matter what type of surgery they practice.

At the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, this eyebrow-raising fact was presented with a sobering addendum: No one seems to be doing much about it.

“There are some ergonomic guidelines for surgeons out there, but most surgeons don’t know about them,” said Tatiana Catanzarite, MD, who has conducted research on this topic. When she began looking into the problem of work-related injuries among surgeons, she was surprised at the dearth of published research. It’s no wonder then, said Dr. Catanzarite and other panel members, that most surgeons learn proper work posture on the fly and may or may not be using the most efficient and mechanically sound instrumentation angles when performing surgery.

Dr. Catanzarite, a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellow at the University of California, San Diego, has just published a literature review on surgeon ergonomics. But reading about how to stand, how to hold instruments, and even how to sit at a robotic surgical console is no match for having an observer on the ground guiding and reinforcing work posture, she said. Unfortunately, that’s an unrealistic expectation for most surgeons, so Dr. Catanzarite is borrowing video-gaming technology to address the situation, she said in an interview.

She has adapted a popular video game motion-capture system that uses an infrared laser projector and a computer sensor to capture video data in three dimensions. The sensing range of the depth sensor is adjustable, and the software is capable of automatically calibrating the sensor based on the physical environment, accommodating the presence of obstacles and using infrared and depth cameras to capture a subject’s 3-D movements. The system doesn’t require bulky wearable components, “making it an ideal technology for the live operating room setting,” Dr. Catanzarite said. “In order to effectively assess surgical ergonomics, a less intrusive approach is needed, which can deliver precise reports on the body movements of the surgeons, as well as capturing the temporal distribution of different postures and limb angles.”

Dr. Catanzarite is using the system to launch an ergonomics assessment tool she calls Ergo-Kinect. The system will record surgeons’ movements in real time, gathering data about how they stand, move, and operate their instruments.

“Three-D interactive visualizations allow us to rotate and investigate specific motor activities from the collected data,” she said. The technology enables them to capture the movements of the surgeon and assign an ergonomic score for each movement. “Eventually we may be able to develop a system that can warn surgeons in real time if they are performing an activity which may be harmful from an ergonomics standpoint,” Dr. Catanzarite said.

The research is in its earliest phase – Dr. Catanzarite has only scanned a few surgeons. But she will continue to accrue data in order to eventually construct a system that could help surgeons of the future avoid the painful, and sometimes debilitating, physical costs of their career.

Dr. Catanzarite reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SAN DIEGO – Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are practically inevitable for surgeons, eventually occurring in more than 90%, no matter what type of surgery they practice.

At the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, this eyebrow-raising fact was presented with a sobering addendum: No one seems to be doing much about it.

“There are some ergonomic guidelines for surgeons out there, but most surgeons don’t know about them,” said Tatiana Catanzarite, MD, who has conducted research on this topic. When she began looking into the problem of work-related injuries among surgeons, she was surprised at the dearth of published research. It’s no wonder then, said Dr. Catanzarite and other panel members, that most surgeons learn proper work posture on the fly and may or may not be using the most efficient and mechanically sound instrumentation angles when performing surgery.

Dr. Catanzarite, a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellow at the University of California, San Diego, has just published a literature review on surgeon ergonomics. But reading about how to stand, how to hold instruments, and even how to sit at a robotic surgical console is no match for having an observer on the ground guiding and reinforcing work posture, she said. Unfortunately, that’s an unrealistic expectation for most surgeons, so Dr. Catanzarite is borrowing video-gaming technology to address the situation, she said in an interview.

She has adapted a popular video game motion-capture system that uses an infrared laser projector and a computer sensor to capture video data in three dimensions. The sensing range of the depth sensor is adjustable, and the software is capable of automatically calibrating the sensor based on the physical environment, accommodating the presence of obstacles and using infrared and depth cameras to capture a subject’s 3-D movements. The system doesn’t require bulky wearable components, “making it an ideal technology for the live operating room setting,” Dr. Catanzarite said. “In order to effectively assess surgical ergonomics, a less intrusive approach is needed, which can deliver precise reports on the body movements of the surgeons, as well as capturing the temporal distribution of different postures and limb angles.”

Dr. Catanzarite is using the system to launch an ergonomics assessment tool she calls Ergo-Kinect. The system will record surgeons’ movements in real time, gathering data about how they stand, move, and operate their instruments.