User login

Rest dyspnea dims as acute heart failure treatment target

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM HEART FAILURE 2017

HFrEF mortality halved when treatment matches guidelines

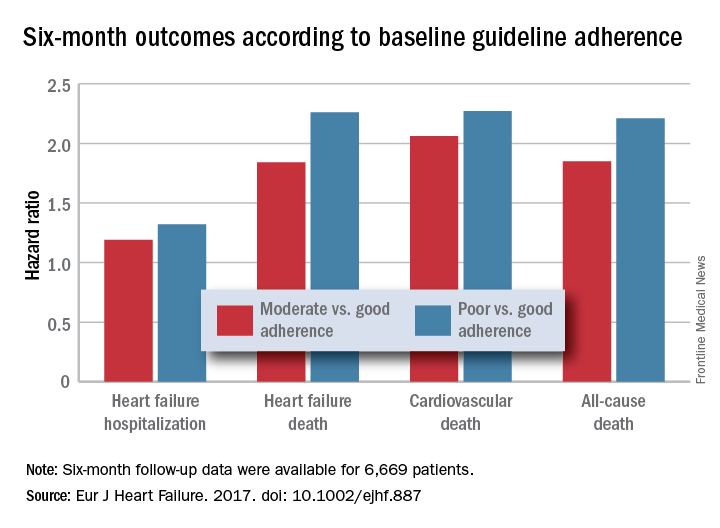

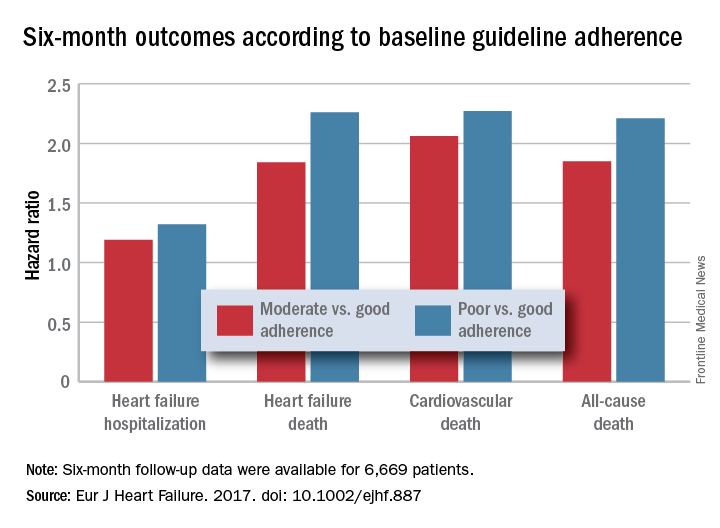

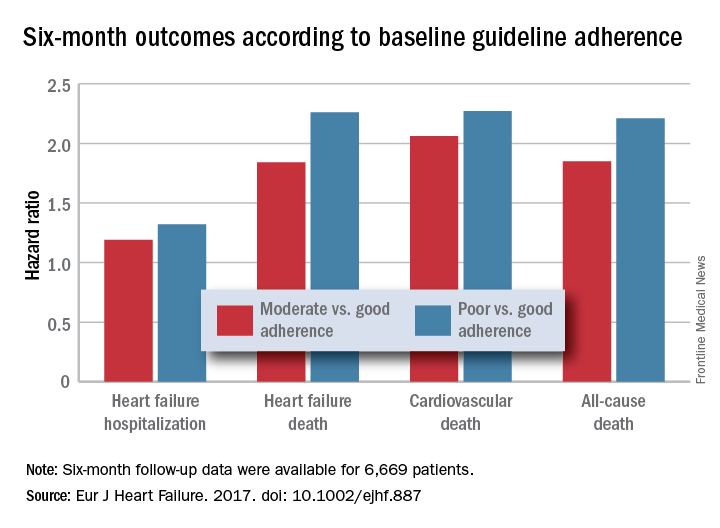

PARIS – Heart failure patients who received guideline-directed pharmacotherapy, at dosages that approached guideline-directed levels, had roughly half the 6-month mortality as did similar patients who did not receive this level of treatment in a real-world, observational study with more than 6,000 patients.

Adherence to pharmacologic treatment guidelines for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “was strongly associated with clinical outcomes during 6-month follow-up,” Michel Komajda, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. The findings highlight the importance of closely following guideline recommendations in routine practice.

[polldaddy:9772629]

The analysis used data collected in the QUALIFY (Quality of Adherence to Guideline Recommendations for Life-Saving Treatment in Heart Failure: an International Survey) registry, which enrolled 7,127 HFrEF patients during September 2013–December 2014 at 547 centers in 36 countries, mostly in Europe, Asia, and Africa but also in Canada, Ecuador, and Australia. All enrolled patients had to have been hospitalized for worsening heart failure at least once during the 1-15 months before they entered QUALIFY.

Dr. Komajda and his associates assessed each enrolled patient at baseline by their treatment with each of four guideline-recommended drug classes: an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; a beta-blocker; an aldosterone receptor antagonist (ARA) if the patient’s functional status was rated as New York Heart Association class II, III, or IV; and ivabradine (Corlanor) if the patient was in NYHA class II, III, or IV, in sinus rhythm, had a heart rate of at least 70 beats per minute, and if the patient was in a country where ivabradine was available. Because patient enrollment occurred in 2013 and 2014, the study couldn’t include the new formulation of sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto) in its analysis.

For each eligible drug class a patient received 1 point if their daily prescribed dosage was at least 50% of the recommended dosage (or 100% for an ARA), 0.5 points if the patient received the recommended drug but at a lower dosage, and no points if the drug wasn’t given. A patient also received 1 point if they were appropriately not given a drug because of a documented contraindication or intolerance. The researchers then calculated each patient’s “adherence score” by dividing their point total by the potentially maximum number of points that each patient could have received (a number that ranged from 2 to 4). They defined a score of 1 (which meant the patients received at least half the recommended dosage of all recommended drugs) as good adherence, a score of 0.51-0.99 as moderate adherence, and a score of 0.5 or less as poor adherence.

Because patient enrollment occurred during 2013 and 2014, the benchmark heart failure treatment guidelines were those issued by the European Society of Cardiology in 2012 (Eur Heart J. 2012 July;33[14]:1787-1847).

Concurrently with Dr. Komajda’s report at the meeting the results appeared in an article online (Eur J Heart Failure. 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.887).

QUANTIFY was sponsored by Servier. Dr. Komajda has received honoraria from Servier and from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This was a wonderful and useful study. It was large, prospective, covered a wide geographic area, and showed that drug dosage matters when treating heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The geographic diversity was a strength, but also a potential weakness because of the resulting differences among the enrolled patients in financial resources, ethnic and genetic makeup, and their tolerance to various drugs. I hope that further research can dissect the role that each of these factors played in the results.

Another limitation is the relatively simplistic approach used for assessing drug dosages to calculate the adherence scores. While it is a very useful step forward to classify patients by the drug dosages they received, there could be some very legitimate variations in dosages based on parameters such as blood pressure. An important question to address in the future is whether it is better to use all the recommended drugs at reduced dosages if necessary, or to use fewer agents at higher dosages.

But these are just quibbles about what is a very important study.

Andrew J.S. Coats, MD , is a cardiologist, professor of medicine, and academic vice-president for the Monash Warwick Alliance of Warwick University in Coventry, England, and Monash University in Melbourne. He has received honoraria from Impulse Dynamics, Menarini, PsiOxus, ResMed, Respicardia, and Servier. He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Komajda’s report.

This was a wonderful and useful study. It was large, prospective, covered a wide geographic area, and showed that drug dosage matters when treating heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The geographic diversity was a strength, but also a potential weakness because of the resulting differences among the enrolled patients in financial resources, ethnic and genetic makeup, and their tolerance to various drugs. I hope that further research can dissect the role that each of these factors played in the results.

Another limitation is the relatively simplistic approach used for assessing drug dosages to calculate the adherence scores. While it is a very useful step forward to classify patients by the drug dosages they received, there could be some very legitimate variations in dosages based on parameters such as blood pressure. An important question to address in the future is whether it is better to use all the recommended drugs at reduced dosages if necessary, or to use fewer agents at higher dosages.

But these are just quibbles about what is a very important study.

Andrew J.S. Coats, MD , is a cardiologist, professor of medicine, and academic vice-president for the Monash Warwick Alliance of Warwick University in Coventry, England, and Monash University in Melbourne. He has received honoraria from Impulse Dynamics, Menarini, PsiOxus, ResMed, Respicardia, and Servier. He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Komajda’s report.

This was a wonderful and useful study. It was large, prospective, covered a wide geographic area, and showed that drug dosage matters when treating heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The geographic diversity was a strength, but also a potential weakness because of the resulting differences among the enrolled patients in financial resources, ethnic and genetic makeup, and their tolerance to various drugs. I hope that further research can dissect the role that each of these factors played in the results.

Another limitation is the relatively simplistic approach used for assessing drug dosages to calculate the adherence scores. While it is a very useful step forward to classify patients by the drug dosages they received, there could be some very legitimate variations in dosages based on parameters such as blood pressure. An important question to address in the future is whether it is better to use all the recommended drugs at reduced dosages if necessary, or to use fewer agents at higher dosages.

But these are just quibbles about what is a very important study.

Andrew J.S. Coats, MD , is a cardiologist, professor of medicine, and academic vice-president for the Monash Warwick Alliance of Warwick University in Coventry, England, and Monash University in Melbourne. He has received honoraria from Impulse Dynamics, Menarini, PsiOxus, ResMed, Respicardia, and Servier. He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Komajda’s report.

PARIS – Heart failure patients who received guideline-directed pharmacotherapy, at dosages that approached guideline-directed levels, had roughly half the 6-month mortality as did similar patients who did not receive this level of treatment in a real-world, observational study with more than 6,000 patients.

Adherence to pharmacologic treatment guidelines for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “was strongly associated with clinical outcomes during 6-month follow-up,” Michel Komajda, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. The findings highlight the importance of closely following guideline recommendations in routine practice.

[polldaddy:9772629]

The analysis used data collected in the QUALIFY (Quality of Adherence to Guideline Recommendations for Life-Saving Treatment in Heart Failure: an International Survey) registry, which enrolled 7,127 HFrEF patients during September 2013–December 2014 at 547 centers in 36 countries, mostly in Europe, Asia, and Africa but also in Canada, Ecuador, and Australia. All enrolled patients had to have been hospitalized for worsening heart failure at least once during the 1-15 months before they entered QUALIFY.

Dr. Komajda and his associates assessed each enrolled patient at baseline by their treatment with each of four guideline-recommended drug classes: an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; a beta-blocker; an aldosterone receptor antagonist (ARA) if the patient’s functional status was rated as New York Heart Association class II, III, or IV; and ivabradine (Corlanor) if the patient was in NYHA class II, III, or IV, in sinus rhythm, had a heart rate of at least 70 beats per minute, and if the patient was in a country where ivabradine was available. Because patient enrollment occurred in 2013 and 2014, the study couldn’t include the new formulation of sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto) in its analysis.

For each eligible drug class a patient received 1 point if their daily prescribed dosage was at least 50% of the recommended dosage (or 100% for an ARA), 0.5 points if the patient received the recommended drug but at a lower dosage, and no points if the drug wasn’t given. A patient also received 1 point if they were appropriately not given a drug because of a documented contraindication or intolerance. The researchers then calculated each patient’s “adherence score” by dividing their point total by the potentially maximum number of points that each patient could have received (a number that ranged from 2 to 4). They defined a score of 1 (which meant the patients received at least half the recommended dosage of all recommended drugs) as good adherence, a score of 0.51-0.99 as moderate adherence, and a score of 0.5 or less as poor adherence.

Because patient enrollment occurred during 2013 and 2014, the benchmark heart failure treatment guidelines were those issued by the European Society of Cardiology in 2012 (Eur Heart J. 2012 July;33[14]:1787-1847).

Concurrently with Dr. Komajda’s report at the meeting the results appeared in an article online (Eur J Heart Failure. 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.887).

QUANTIFY was sponsored by Servier. Dr. Komajda has received honoraria from Servier and from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Heart failure patients who received guideline-directed pharmacotherapy, at dosages that approached guideline-directed levels, had roughly half the 6-month mortality as did similar patients who did not receive this level of treatment in a real-world, observational study with more than 6,000 patients.

Adherence to pharmacologic treatment guidelines for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “was strongly associated with clinical outcomes during 6-month follow-up,” Michel Komajda, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. The findings highlight the importance of closely following guideline recommendations in routine practice.

[polldaddy:9772629]

The analysis used data collected in the QUALIFY (Quality of Adherence to Guideline Recommendations for Life-Saving Treatment in Heart Failure: an International Survey) registry, which enrolled 7,127 HFrEF patients during September 2013–December 2014 at 547 centers in 36 countries, mostly in Europe, Asia, and Africa but also in Canada, Ecuador, and Australia. All enrolled patients had to have been hospitalized for worsening heart failure at least once during the 1-15 months before they entered QUALIFY.

Dr. Komajda and his associates assessed each enrolled patient at baseline by their treatment with each of four guideline-recommended drug classes: an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; a beta-blocker; an aldosterone receptor antagonist (ARA) if the patient’s functional status was rated as New York Heart Association class II, III, or IV; and ivabradine (Corlanor) if the patient was in NYHA class II, III, or IV, in sinus rhythm, had a heart rate of at least 70 beats per minute, and if the patient was in a country where ivabradine was available. Because patient enrollment occurred in 2013 and 2014, the study couldn’t include the new formulation of sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto) in its analysis.

For each eligible drug class a patient received 1 point if their daily prescribed dosage was at least 50% of the recommended dosage (or 100% for an ARA), 0.5 points if the patient received the recommended drug but at a lower dosage, and no points if the drug wasn’t given. A patient also received 1 point if they were appropriately not given a drug because of a documented contraindication or intolerance. The researchers then calculated each patient’s “adherence score” by dividing their point total by the potentially maximum number of points that each patient could have received (a number that ranged from 2 to 4). They defined a score of 1 (which meant the patients received at least half the recommended dosage of all recommended drugs) as good adherence, a score of 0.51-0.99 as moderate adherence, and a score of 0.5 or less as poor adherence.

Because patient enrollment occurred during 2013 and 2014, the benchmark heart failure treatment guidelines were those issued by the European Society of Cardiology in 2012 (Eur Heart J. 2012 July;33[14]:1787-1847).

Concurrently with Dr. Komajda’s report at the meeting the results appeared in an article online (Eur J Heart Failure. 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.887).

QUANTIFY was sponsored by Servier. Dr. Komajda has received honoraria from Servier and from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT HEART FAILURE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Six-month all-cause, cardiovascular, and heart failure mortalities were doubled in patients not on guideline-adherent therapy and dosages.

Data source: QUANTIFY, an international registry with 6,669 HFrEF patients followed for 6 months.

Disclosures: QUANTIFY was sponsored by Servier. Dr. Komajda has received honoraria from Servier and from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Atrial fibrillation blunts beta-blockers for HFrEF

PARIS – Maximal beta-blocker treatment and lower heart rates are effective at cutting all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who are also in sinus rhythm, but it’s a totally different story for patients with similar heart failure plus atrial fibrillation. In the atrial fibrillation subgroup, treatment with a beta-blocker linked with no mortality benefit, and lower heart rates – below 70 beats per minute – appeared to actually link with worse patient survival, based on a meta-analysis of data from 11 beta-blocker trials with a total of more than 17,000 patients.

“Beta blockers may be doing good in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation, but they also are doing harm that neutralizes any good they do.” In patients with HFrEF and atrial fibrillation, “I don’t like to see the heart rate below 80 beats per minute,” John G.F. Cleland, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“We’ve perhaps been too aggressive with heart-rate control in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation,” he added in an interview. In these patients “in the range of 60-100 bpm it doesn’t seem to make a lot of difference what the heart rate is, and, if it is less than 70 bpm, patients seem to do a little worse. When we treat these patients with a beta-blocker we don’t see benefit in any way that we’ve looked at the data.”

In contrast, among HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm “beta-blocker treatment is similarly effective regardless of what the baseline heart rate was. The benefit was as great when the baseline rate was 70 bpm or 90 bpm, so heart rate is not a great predictor of beta-blocker benefit in these patients. Patients who tolerated the full beta-blocker dosage had the greatest benefit, and patients who achieved the slowest heart rates also had the greatest benefit.”

In the multivariate models that Dr. Cleland and his associates tested in their meta-analysis, in HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm, the relationship between reduced heart rate and mortality benefit was stronger statistically than between beta-blocker dosage and reduced mortality, he said. “This suggests to me that, while we should use the targeted beta-blocker dosages when we can, it’s more important to achieve a target heart rate in these patients of 55-65 bpm.”

Dr. Cleland hypothesized, based on a report presented at the same meeting by a different research group, that reduced heart rate is not beneficial in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation because in this subgroup slower heart rates linked with an increased number of brief pauses in left ventricular pumping. These pauses may result in ventricular arrhythmias, he speculated. “It may be that beta-blockers are equally effective at slowing heart rate in patients with or without atrial fibrillation, but there is also harm from beta-blockers because they’re causing pauses in patients with atrial fibrillation,” he said.

These days, if he has a HFrEF patient with atrial fibrillation whose heart rate slows to 60 bpm, he will stop digoxin treatment if the patient is on that drug, and he will also reduce the beta-blocker dosage but not discontinue it.

The findings came from the Collaborative Systematic Overview of Randomized Controlled Trials of Beta-Blockers in the Treatment of Heart Failure (BB-META-HF), which included data from 11 large beta-blocker randomized trials in heart failure that had been published during 1993-2005. The analysis included data from 17,378 HFrEF patients, with 14,313 (82%) in sinus rhythm and 3,065 (18%) with atrial fibrillation. Follow-up data of patients on treatment was available for 15,007 of these patients.

Dr. Cleland and his associates showed in multivariate analyses that, when they controlled for several baseline demographic and clinical variables among patients in sinus rhythm who received a beta-blocker, the follow-up all-cause mortality fell by 36%, compared with placebo, in patients with a resting baseline heart rate of less than 70 bpm; by 21%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of 70-90 bpm; and by 38%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of more than 90 bpm. All three reductions were statistically significant. In contrast, among patients who also had atrial fibrillation beta-blocker treatment linked with no significant mortality reduction, compared with placebo, for patients with any baseline heart rate. Concurrently with Dr. Cleland’s report at the meeting the results appeared online (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.001).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The findings from this analysis have several implications. First, the association of reduced mortality with reduced heart rate occurred only in patients in sinus rhythm. The irregular heart rhythms in patients with atrial fibrillation may counterbalance any reverse remodeling effects that come from reducing heart rate.

Also, the beneficial effect of beta-blocker treatment was roughly similar regardless of whether baseline heart rate was high or low. This distinguishes beta-blockers from ivabradine, a drug that only reduces heart rate. The magnitude of benefit from ivabradine treatment depends on a patient’s baseline heart rate. The observation that beta-blockers do not have the same limitation suggests that the mechanism of action of beta-blockers may go beyond their heart rate effect. It may also result from the effect of beta-blockers on antagonizing toxic effects from beta-adrenergic stimulation.

The pooled analysis also showed that many patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm continued to have a high heart rate despite beta-blocker treatment. These patients may get additional benefit from further treatment to reduce their heart rate, with an agent like ivabradine.

But we must be cautious in interpreting the findings because they represent a secondary analysis, and the endpoint studied does not take into account quality of life, exercise tolerance, heart rate control, and tachyarrhythmias. We need prospective, randomized trials of HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm and with atrial fibrillation to better understand how to optimally treat these different types of patients.

The findings highlight that beta-blockers remain a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm, and that we have more limited treatment options for HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation.

Michael Böhm, MD, is professor and director of the cardiology clinic at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany. He has received honoraria from Bayer, Medtronic, Servier, and Pfizer, and he was a coauthor on the report presented by Dr. Cleland. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study.

The findings from this analysis have several implications. First, the association of reduced mortality with reduced heart rate occurred only in patients in sinus rhythm. The irregular heart rhythms in patients with atrial fibrillation may counterbalance any reverse remodeling effects that come from reducing heart rate.

Also, the beneficial effect of beta-blocker treatment was roughly similar regardless of whether baseline heart rate was high or low. This distinguishes beta-blockers from ivabradine, a drug that only reduces heart rate. The magnitude of benefit from ivabradine treatment depends on a patient’s baseline heart rate. The observation that beta-blockers do not have the same limitation suggests that the mechanism of action of beta-blockers may go beyond their heart rate effect. It may also result from the effect of beta-blockers on antagonizing toxic effects from beta-adrenergic stimulation.

The pooled analysis also showed that many patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm continued to have a high heart rate despite beta-blocker treatment. These patients may get additional benefit from further treatment to reduce their heart rate, with an agent like ivabradine.

But we must be cautious in interpreting the findings because they represent a secondary analysis, and the endpoint studied does not take into account quality of life, exercise tolerance, heart rate control, and tachyarrhythmias. We need prospective, randomized trials of HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm and with atrial fibrillation to better understand how to optimally treat these different types of patients.

The findings highlight that beta-blockers remain a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm, and that we have more limited treatment options for HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation.

Michael Böhm, MD, is professor and director of the cardiology clinic at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany. He has received honoraria from Bayer, Medtronic, Servier, and Pfizer, and he was a coauthor on the report presented by Dr. Cleland. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study.

The findings from this analysis have several implications. First, the association of reduced mortality with reduced heart rate occurred only in patients in sinus rhythm. The irregular heart rhythms in patients with atrial fibrillation may counterbalance any reverse remodeling effects that come from reducing heart rate.

Also, the beneficial effect of beta-blocker treatment was roughly similar regardless of whether baseline heart rate was high or low. This distinguishes beta-blockers from ivabradine, a drug that only reduces heart rate. The magnitude of benefit from ivabradine treatment depends on a patient’s baseline heart rate. The observation that beta-blockers do not have the same limitation suggests that the mechanism of action of beta-blockers may go beyond their heart rate effect. It may also result from the effect of beta-blockers on antagonizing toxic effects from beta-adrenergic stimulation.

The pooled analysis also showed that many patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm continued to have a high heart rate despite beta-blocker treatment. These patients may get additional benefit from further treatment to reduce their heart rate, with an agent like ivabradine.

But we must be cautious in interpreting the findings because they represent a secondary analysis, and the endpoint studied does not take into account quality of life, exercise tolerance, heart rate control, and tachyarrhythmias. We need prospective, randomized trials of HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm and with atrial fibrillation to better understand how to optimally treat these different types of patients.

The findings highlight that beta-blockers remain a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm, and that we have more limited treatment options for HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation.

Michael Böhm, MD, is professor and director of the cardiology clinic at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany. He has received honoraria from Bayer, Medtronic, Servier, and Pfizer, and he was a coauthor on the report presented by Dr. Cleland. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study.

PARIS – Maximal beta-blocker treatment and lower heart rates are effective at cutting all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who are also in sinus rhythm, but it’s a totally different story for patients with similar heart failure plus atrial fibrillation. In the atrial fibrillation subgroup, treatment with a beta-blocker linked with no mortality benefit, and lower heart rates – below 70 beats per minute – appeared to actually link with worse patient survival, based on a meta-analysis of data from 11 beta-blocker trials with a total of more than 17,000 patients.

“Beta blockers may be doing good in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation, but they also are doing harm that neutralizes any good they do.” In patients with HFrEF and atrial fibrillation, “I don’t like to see the heart rate below 80 beats per minute,” John G.F. Cleland, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“We’ve perhaps been too aggressive with heart-rate control in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation,” he added in an interview. In these patients “in the range of 60-100 bpm it doesn’t seem to make a lot of difference what the heart rate is, and, if it is less than 70 bpm, patients seem to do a little worse. When we treat these patients with a beta-blocker we don’t see benefit in any way that we’ve looked at the data.”

In contrast, among HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm “beta-blocker treatment is similarly effective regardless of what the baseline heart rate was. The benefit was as great when the baseline rate was 70 bpm or 90 bpm, so heart rate is not a great predictor of beta-blocker benefit in these patients. Patients who tolerated the full beta-blocker dosage had the greatest benefit, and patients who achieved the slowest heart rates also had the greatest benefit.”

In the multivariate models that Dr. Cleland and his associates tested in their meta-analysis, in HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm, the relationship between reduced heart rate and mortality benefit was stronger statistically than between beta-blocker dosage and reduced mortality, he said. “This suggests to me that, while we should use the targeted beta-blocker dosages when we can, it’s more important to achieve a target heart rate in these patients of 55-65 bpm.”

Dr. Cleland hypothesized, based on a report presented at the same meeting by a different research group, that reduced heart rate is not beneficial in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation because in this subgroup slower heart rates linked with an increased number of brief pauses in left ventricular pumping. These pauses may result in ventricular arrhythmias, he speculated. “It may be that beta-blockers are equally effective at slowing heart rate in patients with or without atrial fibrillation, but there is also harm from beta-blockers because they’re causing pauses in patients with atrial fibrillation,” he said.

These days, if he has a HFrEF patient with atrial fibrillation whose heart rate slows to 60 bpm, he will stop digoxin treatment if the patient is on that drug, and he will also reduce the beta-blocker dosage but not discontinue it.

The findings came from the Collaborative Systematic Overview of Randomized Controlled Trials of Beta-Blockers in the Treatment of Heart Failure (BB-META-HF), which included data from 11 large beta-blocker randomized trials in heart failure that had been published during 1993-2005. The analysis included data from 17,378 HFrEF patients, with 14,313 (82%) in sinus rhythm and 3,065 (18%) with atrial fibrillation. Follow-up data of patients on treatment was available for 15,007 of these patients.

Dr. Cleland and his associates showed in multivariate analyses that, when they controlled for several baseline demographic and clinical variables among patients in sinus rhythm who received a beta-blocker, the follow-up all-cause mortality fell by 36%, compared with placebo, in patients with a resting baseline heart rate of less than 70 bpm; by 21%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of 70-90 bpm; and by 38%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of more than 90 bpm. All three reductions were statistically significant. In contrast, among patients who also had atrial fibrillation beta-blocker treatment linked with no significant mortality reduction, compared with placebo, for patients with any baseline heart rate. Concurrently with Dr. Cleland’s report at the meeting the results appeared online (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.001).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Maximal beta-blocker treatment and lower heart rates are effective at cutting all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who are also in sinus rhythm, but it’s a totally different story for patients with similar heart failure plus atrial fibrillation. In the atrial fibrillation subgroup, treatment with a beta-blocker linked with no mortality benefit, and lower heart rates – below 70 beats per minute – appeared to actually link with worse patient survival, based on a meta-analysis of data from 11 beta-blocker trials with a total of more than 17,000 patients.

“Beta blockers may be doing good in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation, but they also are doing harm that neutralizes any good they do.” In patients with HFrEF and atrial fibrillation, “I don’t like to see the heart rate below 80 beats per minute,” John G.F. Cleland, MD, said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“We’ve perhaps been too aggressive with heart-rate control in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation,” he added in an interview. In these patients “in the range of 60-100 bpm it doesn’t seem to make a lot of difference what the heart rate is, and, if it is less than 70 bpm, patients seem to do a little worse. When we treat these patients with a beta-blocker we don’t see benefit in any way that we’ve looked at the data.”

In contrast, among HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm “beta-blocker treatment is similarly effective regardless of what the baseline heart rate was. The benefit was as great when the baseline rate was 70 bpm or 90 bpm, so heart rate is not a great predictor of beta-blocker benefit in these patients. Patients who tolerated the full beta-blocker dosage had the greatest benefit, and patients who achieved the slowest heart rates also had the greatest benefit.”

In the multivariate models that Dr. Cleland and his associates tested in their meta-analysis, in HFrEF patients in sinus rhythm, the relationship between reduced heart rate and mortality benefit was stronger statistically than between beta-blocker dosage and reduced mortality, he said. “This suggests to me that, while we should use the targeted beta-blocker dosages when we can, it’s more important to achieve a target heart rate in these patients of 55-65 bpm.”

Dr. Cleland hypothesized, based on a report presented at the same meeting by a different research group, that reduced heart rate is not beneficial in HFrEF patients with atrial fibrillation because in this subgroup slower heart rates linked with an increased number of brief pauses in left ventricular pumping. These pauses may result in ventricular arrhythmias, he speculated. “It may be that beta-blockers are equally effective at slowing heart rate in patients with or without atrial fibrillation, but there is also harm from beta-blockers because they’re causing pauses in patients with atrial fibrillation,” he said.

These days, if he has a HFrEF patient with atrial fibrillation whose heart rate slows to 60 bpm, he will stop digoxin treatment if the patient is on that drug, and he will also reduce the beta-blocker dosage but not discontinue it.

The findings came from the Collaborative Systematic Overview of Randomized Controlled Trials of Beta-Blockers in the Treatment of Heart Failure (BB-META-HF), which included data from 11 large beta-blocker randomized trials in heart failure that had been published during 1993-2005. The analysis included data from 17,378 HFrEF patients, with 14,313 (82%) in sinus rhythm and 3,065 (18%) with atrial fibrillation. Follow-up data of patients on treatment was available for 15,007 of these patients.

Dr. Cleland and his associates showed in multivariate analyses that, when they controlled for several baseline demographic and clinical variables among patients in sinus rhythm who received a beta-blocker, the follow-up all-cause mortality fell by 36%, compared with placebo, in patients with a resting baseline heart rate of less than 70 bpm; by 21%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of 70-90 bpm; and by 38%, compared with placebo, in patients with a baseline heart rate of more than 90 bpm. All three reductions were statistically significant. In contrast, among patients who also had atrial fibrillation beta-blocker treatment linked with no significant mortality reduction, compared with placebo, for patients with any baseline heart rate. Concurrently with Dr. Cleland’s report at the meeting the results appeared online (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.001).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT HEART FAILURE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All-cause mortality was similar in patients with HFrEF and atrial fibrillation regardless of whether they received a beta-blocker or placebo.

Data source: BB-META-HF, a meta-analysis of 11 beta-blocker treatment trials with 17,378 HFrEF patients.

Disclosures: BB-META-HF received funding from Menarini and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Cleland has received research funding and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

A prescription for heart failure success: Change the name

PARIS – Does heart failure’s name doom any progress against the disease?

That was the provocative premise advanced by Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, who suggested that efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease would go better if it could only jettison that unfortunate word “failure,” its hard-wired albatross.

Dr. Stevenson offered several potentially superior alternatives, including cardiac insufficiency, heart dysfunction, and her favorite, cardiomyopathy.

“Is heart failure still the best diagnosis” for the entire spectrum of disease that most patients progress through ,including the many patients in earlier stages of the disease who do not have a truly failing heart? “Perhaps cardiomyopathy is the condition and heart failure is the transition,” she proposed.

To Dr. Stevenson, it’s more than just semantics.

“Words are hugely powerful,” she explained in an interview following her talk. “I think patients do not want to be seen as having heart failure. They don’t want to think of themselves as having heart failure. I think it can make them delay getting care, and it makes them ignore the disease. I worry about that a lot. I also worry that patients don’t provide support to each other that they could. Patients tend to hide that they have heart failure. We need to come up with a term that does not make patients ashamed of their disease.”

Part of the problem, Dr. Stevenson said, is that the name heart failure can be very misleading depending on the stage of the disease that patients have. Patients with stage B (presymptomatic) disease and those with mild stage C disease “don’t see themselves as having heart failure,” as having a heart that has failed them. “We need to be able to convince these patients that they have a disease that we need to treat carefully and aggressively.”

Additionally, labeling tens of millions of people as having stage A heart failure, which is presymptomatic and occurs before the heart shows any sign of damage or dysfunction, is also counterproductive, maintained Dr. Stevenson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“So many people are at risk of developing heart failure,” she noted, including patients with hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease. To label them all as already also having heart failure at that stage “tends to make them ignore the disease that we are trying to get them to pay attention to. Telling patients they have the disease that we are trying to prevent doesn’t help.”

Calling the whole range of the disease heart failure also confuses patients and others. “Patients ask me, ‘How can I have heart failure without any symptoms?’ ‘My ejection fraction improved to almost normal; do I still have heart failure?’ and ‘I don’t understand how my heart muscle is strong but my heart is failing,’ ” she said

For Dr. Stevenson, perhaps the biggest problem is the stigma of failure and the way that word ties a huge weight to the disease that prompts patients and caregivers alike to relegate it to a hidden and neglected place.

“It’s failure. Who is proud to have heart failure? Where are the marches for heart failure? Where are the celebrity champions for heart failure? We have celebrities who are happy to admit that they have Parkinson’s disease, ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis], drug addiction, and even erectile dysfunction, but no one wants to say they have heart failure. We can’t get any traction behind heart failure. It doesn’t sound very inspiring,” an issue that even percolates down to dissuading clinicians from pursuing a career in heart failure care. Young people do not aspire to go into failure, she said.

“We need to call it something else.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Does heart failure’s name doom any progress against the disease?

That was the provocative premise advanced by Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, who suggested that efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease would go better if it could only jettison that unfortunate word “failure,” its hard-wired albatross.

Dr. Stevenson offered several potentially superior alternatives, including cardiac insufficiency, heart dysfunction, and her favorite, cardiomyopathy.

“Is heart failure still the best diagnosis” for the entire spectrum of disease that most patients progress through ,including the many patients in earlier stages of the disease who do not have a truly failing heart? “Perhaps cardiomyopathy is the condition and heart failure is the transition,” she proposed.

To Dr. Stevenson, it’s more than just semantics.

“Words are hugely powerful,” she explained in an interview following her talk. “I think patients do not want to be seen as having heart failure. They don’t want to think of themselves as having heart failure. I think it can make them delay getting care, and it makes them ignore the disease. I worry about that a lot. I also worry that patients don’t provide support to each other that they could. Patients tend to hide that they have heart failure. We need to come up with a term that does not make patients ashamed of their disease.”

Part of the problem, Dr. Stevenson said, is that the name heart failure can be very misleading depending on the stage of the disease that patients have. Patients with stage B (presymptomatic) disease and those with mild stage C disease “don’t see themselves as having heart failure,” as having a heart that has failed them. “We need to be able to convince these patients that they have a disease that we need to treat carefully and aggressively.”

Additionally, labeling tens of millions of people as having stage A heart failure, which is presymptomatic and occurs before the heart shows any sign of damage or dysfunction, is also counterproductive, maintained Dr. Stevenson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“So many people are at risk of developing heart failure,” she noted, including patients with hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease. To label them all as already also having heart failure at that stage “tends to make them ignore the disease that we are trying to get them to pay attention to. Telling patients they have the disease that we are trying to prevent doesn’t help.”

Calling the whole range of the disease heart failure also confuses patients and others. “Patients ask me, ‘How can I have heart failure without any symptoms?’ ‘My ejection fraction improved to almost normal; do I still have heart failure?’ and ‘I don’t understand how my heart muscle is strong but my heart is failing,’ ” she said

For Dr. Stevenson, perhaps the biggest problem is the stigma of failure and the way that word ties a huge weight to the disease that prompts patients and caregivers alike to relegate it to a hidden and neglected place.

“It’s failure. Who is proud to have heart failure? Where are the marches for heart failure? Where are the celebrity champions for heart failure? We have celebrities who are happy to admit that they have Parkinson’s disease, ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis], drug addiction, and even erectile dysfunction, but no one wants to say they have heart failure. We can’t get any traction behind heart failure. It doesn’t sound very inspiring,” an issue that even percolates down to dissuading clinicians from pursuing a career in heart failure care. Young people do not aspire to go into failure, she said.

“We need to call it something else.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Does heart failure’s name doom any progress against the disease?

That was the provocative premise advanced by Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, who suggested that efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease would go better if it could only jettison that unfortunate word “failure,” its hard-wired albatross.

Dr. Stevenson offered several potentially superior alternatives, including cardiac insufficiency, heart dysfunction, and her favorite, cardiomyopathy.

“Is heart failure still the best diagnosis” for the entire spectrum of disease that most patients progress through ,including the many patients in earlier stages of the disease who do not have a truly failing heart? “Perhaps cardiomyopathy is the condition and heart failure is the transition,” she proposed.

To Dr. Stevenson, it’s more than just semantics.

“Words are hugely powerful,” she explained in an interview following her talk. “I think patients do not want to be seen as having heart failure. They don’t want to think of themselves as having heart failure. I think it can make them delay getting care, and it makes them ignore the disease. I worry about that a lot. I also worry that patients don’t provide support to each other that they could. Patients tend to hide that they have heart failure. We need to come up with a term that does not make patients ashamed of their disease.”

Part of the problem, Dr. Stevenson said, is that the name heart failure can be very misleading depending on the stage of the disease that patients have. Patients with stage B (presymptomatic) disease and those with mild stage C disease “don’t see themselves as having heart failure,” as having a heart that has failed them. “We need to be able to convince these patients that they have a disease that we need to treat carefully and aggressively.”

Additionally, labeling tens of millions of people as having stage A heart failure, which is presymptomatic and occurs before the heart shows any sign of damage or dysfunction, is also counterproductive, maintained Dr. Stevenson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“So many people are at risk of developing heart failure,” she noted, including patients with hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease. To label them all as already also having heart failure at that stage “tends to make them ignore the disease that we are trying to get them to pay attention to. Telling patients they have the disease that we are trying to prevent doesn’t help.”

Calling the whole range of the disease heart failure also confuses patients and others. “Patients ask me, ‘How can I have heart failure without any symptoms?’ ‘My ejection fraction improved to almost normal; do I still have heart failure?’ and ‘I don’t understand how my heart muscle is strong but my heart is failing,’ ” she said

For Dr. Stevenson, perhaps the biggest problem is the stigma of failure and the way that word ties a huge weight to the disease that prompts patients and caregivers alike to relegate it to a hidden and neglected place.

“It’s failure. Who is proud to have heart failure? Where are the marches for heart failure? Where are the celebrity champions for heart failure? We have celebrities who are happy to admit that they have Parkinson’s disease, ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis], drug addiction, and even erectile dysfunction, but no one wants to say they have heart failure. We can’t get any traction behind heart failure. It doesn’t sound very inspiring,” an issue that even percolates down to dissuading clinicians from pursuing a career in heart failure care. Young people do not aspire to go into failure, she said.