User login

Epilepsy

High infantile spasm risk should contraindicate sodium channel blocker antiepileptics

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Study delineates spectrum of Dravet syndrome phenotypes

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Reduction in convulsive seizure frequency is associated with improved executive function in Dravet syndrome

BALTIMORE – according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Large reductions in convulsive seizure frequency for prolonged periods may improve everyday deficits in executive function in these patients, according to the investigators.

Dravet syndrome often entails cognitive impairment, including deficits in executive function. The frequency and severity of convulsive seizures are believed to worsen cognitive impairment over time, but few researchers have conducted long-term studies to test this hypothesis. Adjunctive fenfluramine significantly reduced the frequency of convulsive seizures and improved executive function after 14 weeks in a phase 3 study of patients with Dravet syndrome.

An open-label extension of a phase 3 study

In an open-label extension of this study, Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, and colleagues analyzed the relationship between changes in convulsive seizure frequency and executive function. The investigators also examined the effect of reducing convulsive seizure frequency by comparing patients with profound reductions (greater than 75%) versus patients with minimal reductions (less than 25%).

Patients aged 2-18 years entered the open-label study and received adjunctive fenfluramine for 1 year. At the beginning of the open-label phase, the dose was titrated to effect. The dose ranged from 0.2 mg/kg per day to 0.7 mg/kg per day and was administered as 2.5 mg/mL of fenfluramine. The maximum dose was 17 mg with stiripentol or 26 mg without.

The investigators calculated the percent difference in convulsive seizure frequency per 28 days from baseline to the end of the open-label study. They evaluated executive function using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), which caregivers completed at baseline and year 1 for patients aged 5-18 years. Scores on the BRIEF were updated to the newer version: BRIEF2. Dr. Sullivan and colleagues calculated Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients to evaluate the association between BRIEF2 Behavior Regulation Index, Emotion Regulation Index, Cognitive Regulation Index, and Global Executive Composite scores. Lower scores on the BRIEF2 indexes and composite indicate better executive functioning. In addition, the researchers compared clinically meaningful change in BRIEF2 indexes and composite scores from baseline to year 1 between patients with minimal and profound reductions in convulsive seizure frequency using Fisher’s exact test. They defined a clinically meaningful change as an improvement in the Reliable Change Index of greater than 95%.

Profound reduction in seizure frequency was common

At the time of analysis, 53 patients had completed at least 1 year of open-label fenfluramine and had baseline and year 1 BRIEF2 data. Patients’ median age was 10 years, and 57% of patients were male. The median reduction from prerandomization baseline in convulsive seizure frequency was 71%. The reduction ranged from 99.7% to 55.0%.

Twenty-four (45%) patients had a reduction in convulsive seizure frequency of greater than 75%, and 11 (21%) had a reduction of less than 25%. Change in convulsive seizure frequency correlated significantly with Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite. Change in seizure frequency tended to correlate with Cognitive Regulation Index, but the result was not statistically significant. Change in convulsive seizure frequency was not significantly associated with Behavior Regulation Index. A significantly higher percentage of patients in the profound responder group had significant, clinically meaningful improvements on Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite, compared with minimal responders.

Zogenix, the company that is developing fenfluramine as a treatment for Dravet syndrome, funded the study. Several investigators are employees of Zogenix.

SOURCE: Bishop KI et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.438.

BALTIMORE – according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Large reductions in convulsive seizure frequency for prolonged periods may improve everyday deficits in executive function in these patients, according to the investigators.

Dravet syndrome often entails cognitive impairment, including deficits in executive function. The frequency and severity of convulsive seizures are believed to worsen cognitive impairment over time, but few researchers have conducted long-term studies to test this hypothesis. Adjunctive fenfluramine significantly reduced the frequency of convulsive seizures and improved executive function after 14 weeks in a phase 3 study of patients with Dravet syndrome.

An open-label extension of a phase 3 study

In an open-label extension of this study, Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, and colleagues analyzed the relationship between changes in convulsive seizure frequency and executive function. The investigators also examined the effect of reducing convulsive seizure frequency by comparing patients with profound reductions (greater than 75%) versus patients with minimal reductions (less than 25%).

Patients aged 2-18 years entered the open-label study and received adjunctive fenfluramine for 1 year. At the beginning of the open-label phase, the dose was titrated to effect. The dose ranged from 0.2 mg/kg per day to 0.7 mg/kg per day and was administered as 2.5 mg/mL of fenfluramine. The maximum dose was 17 mg with stiripentol or 26 mg without.

The investigators calculated the percent difference in convulsive seizure frequency per 28 days from baseline to the end of the open-label study. They evaluated executive function using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), which caregivers completed at baseline and year 1 for patients aged 5-18 years. Scores on the BRIEF were updated to the newer version: BRIEF2. Dr. Sullivan and colleagues calculated Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients to evaluate the association between BRIEF2 Behavior Regulation Index, Emotion Regulation Index, Cognitive Regulation Index, and Global Executive Composite scores. Lower scores on the BRIEF2 indexes and composite indicate better executive functioning. In addition, the researchers compared clinically meaningful change in BRIEF2 indexes and composite scores from baseline to year 1 between patients with minimal and profound reductions in convulsive seizure frequency using Fisher’s exact test. They defined a clinically meaningful change as an improvement in the Reliable Change Index of greater than 95%.

Profound reduction in seizure frequency was common

At the time of analysis, 53 patients had completed at least 1 year of open-label fenfluramine and had baseline and year 1 BRIEF2 data. Patients’ median age was 10 years, and 57% of patients were male. The median reduction from prerandomization baseline in convulsive seizure frequency was 71%. The reduction ranged from 99.7% to 55.0%.

Twenty-four (45%) patients had a reduction in convulsive seizure frequency of greater than 75%, and 11 (21%) had a reduction of less than 25%. Change in convulsive seizure frequency correlated significantly with Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite. Change in seizure frequency tended to correlate with Cognitive Regulation Index, but the result was not statistically significant. Change in convulsive seizure frequency was not significantly associated with Behavior Regulation Index. A significantly higher percentage of patients in the profound responder group had significant, clinically meaningful improvements on Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite, compared with minimal responders.

Zogenix, the company that is developing fenfluramine as a treatment for Dravet syndrome, funded the study. Several investigators are employees of Zogenix.

SOURCE: Bishop KI et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.438.

BALTIMORE – according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Large reductions in convulsive seizure frequency for prolonged periods may improve everyday deficits in executive function in these patients, according to the investigators.

Dravet syndrome often entails cognitive impairment, including deficits in executive function. The frequency and severity of convulsive seizures are believed to worsen cognitive impairment over time, but few researchers have conducted long-term studies to test this hypothesis. Adjunctive fenfluramine significantly reduced the frequency of convulsive seizures and improved executive function after 14 weeks in a phase 3 study of patients with Dravet syndrome.

An open-label extension of a phase 3 study

In an open-label extension of this study, Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, and colleagues analyzed the relationship between changes in convulsive seizure frequency and executive function. The investigators also examined the effect of reducing convulsive seizure frequency by comparing patients with profound reductions (greater than 75%) versus patients with minimal reductions (less than 25%).

Patients aged 2-18 years entered the open-label study and received adjunctive fenfluramine for 1 year. At the beginning of the open-label phase, the dose was titrated to effect. The dose ranged from 0.2 mg/kg per day to 0.7 mg/kg per day and was administered as 2.5 mg/mL of fenfluramine. The maximum dose was 17 mg with stiripentol or 26 mg without.

The investigators calculated the percent difference in convulsive seizure frequency per 28 days from baseline to the end of the open-label study. They evaluated executive function using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), which caregivers completed at baseline and year 1 for patients aged 5-18 years. Scores on the BRIEF were updated to the newer version: BRIEF2. Dr. Sullivan and colleagues calculated Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients to evaluate the association between BRIEF2 Behavior Regulation Index, Emotion Regulation Index, Cognitive Regulation Index, and Global Executive Composite scores. Lower scores on the BRIEF2 indexes and composite indicate better executive functioning. In addition, the researchers compared clinically meaningful change in BRIEF2 indexes and composite scores from baseline to year 1 between patients with minimal and profound reductions in convulsive seizure frequency using Fisher’s exact test. They defined a clinically meaningful change as an improvement in the Reliable Change Index of greater than 95%.

Profound reduction in seizure frequency was common

At the time of analysis, 53 patients had completed at least 1 year of open-label fenfluramine and had baseline and year 1 BRIEF2 data. Patients’ median age was 10 years, and 57% of patients were male. The median reduction from prerandomization baseline in convulsive seizure frequency was 71%. The reduction ranged from 99.7% to 55.0%.

Twenty-four (45%) patients had a reduction in convulsive seizure frequency of greater than 75%, and 11 (21%) had a reduction of less than 25%. Change in convulsive seizure frequency correlated significantly with Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite. Change in seizure frequency tended to correlate with Cognitive Regulation Index, but the result was not statistically significant. Change in convulsive seizure frequency was not significantly associated with Behavior Regulation Index. A significantly higher percentage of patients in the profound responder group had significant, clinically meaningful improvements on Emotion Regulation Index and Global Executive Composite, compared with minimal responders.

Zogenix, the company that is developing fenfluramine as a treatment for Dravet syndrome, funded the study. Several investigators are employees of Zogenix.

SOURCE: Bishop KI et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.438.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Scalp EEG predicts temporal lobe resection success

BALTIMORE – In a review of 43 temporal lobe epilepsy patients at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., anteromedial temporal resection (AMTR) failed in every case in which initial ictal rhythm on scalp EEG spread beyond the medial temporal lobe to other brain regions within 10 seconds.

Among the 33 patients who had no spread on preoperative scalp EEG or who spread in 10 or more seconds, 31 (94%) had a good outcome, meaning they were seizure free or had only auras after AMTR. The findings could mean that scalp EEG can predict surgery outcome.

AMTR works in the majority of patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy, but about 10-20% continue to have seizures. Senior investigator Pue Farooque, DO, from Yale University wanted to find a way to identify patients likely to fail surgery beforehand to help counsel patients on what to expect and also to know when other treatment options might be a better bet.

“If you see seizures are spreading quickly to another area, like the frontal lobe or the temporal neocortex, you could implant RNS [responsive neurostimulation]” instead of doing an ATMR, “and that might improve your outcomes,” she said at the American Epilepsy Society’s annual meeting.

The findings are essentially the same as when the group used intracranial EEG to detect fast spread in a previous report, but scalp EEG is noninvasive and allows for easy preoperative assessment (JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:462-9).

The team also found in their new study that diffuse hypometabolism in the entire temporal lobe on quantitative PET also predicted poor ATMR outcomes (P less than .001), but Dr. Farooque said more work is needed to quantify the finding. The investigators also plan to assess the predictive value of resting functional MRI.

The take home, she said, is that “we can do better” with epilepsy surgery, and “there are noninvasive markers we can use to help guide us.”

It’s unclear why more rapid seizure spread would predict AMTR failure. In the earlier study with intracranial EEG, the investigators said “the results are best explained by attributing epileptogenic potential to sites of early seizure spread that were not included in resection. This mechanism of failure implies that a distributed epileptogenic network rather than a single epileptogenic focus may underlie surgically refractory epilepsy.”

Patients in the new report had epilepsy for a mean of 24.4 years, and 25 (58%) were women; 30 cases (69%) were lesional, and follow-up was at least a year. The contralateral or lateralized seizure spread ranged from 1 to 63 seconds, with a mean of 18.5 seconds. Among patients who failed AMTR, seizure spread occurred at a mean of 7.1 seconds.

Electrographic pattern at onset and location of interictal epileptiform discharges did not predict outcome

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Farooque didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chiari J et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.36.

BALTIMORE – In a review of 43 temporal lobe epilepsy patients at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., anteromedial temporal resection (AMTR) failed in every case in which initial ictal rhythm on scalp EEG spread beyond the medial temporal lobe to other brain regions within 10 seconds.

Among the 33 patients who had no spread on preoperative scalp EEG or who spread in 10 or more seconds, 31 (94%) had a good outcome, meaning they were seizure free or had only auras after AMTR. The findings could mean that scalp EEG can predict surgery outcome.

AMTR works in the majority of patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy, but about 10-20% continue to have seizures. Senior investigator Pue Farooque, DO, from Yale University wanted to find a way to identify patients likely to fail surgery beforehand to help counsel patients on what to expect and also to know when other treatment options might be a better bet.

“If you see seizures are spreading quickly to another area, like the frontal lobe or the temporal neocortex, you could implant RNS [responsive neurostimulation]” instead of doing an ATMR, “and that might improve your outcomes,” she said at the American Epilepsy Society’s annual meeting.

The findings are essentially the same as when the group used intracranial EEG to detect fast spread in a previous report, but scalp EEG is noninvasive and allows for easy preoperative assessment (JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:462-9).

The team also found in their new study that diffuse hypometabolism in the entire temporal lobe on quantitative PET also predicted poor ATMR outcomes (P less than .001), but Dr. Farooque said more work is needed to quantify the finding. The investigators also plan to assess the predictive value of resting functional MRI.

The take home, she said, is that “we can do better” with epilepsy surgery, and “there are noninvasive markers we can use to help guide us.”

It’s unclear why more rapid seizure spread would predict AMTR failure. In the earlier study with intracranial EEG, the investigators said “the results are best explained by attributing epileptogenic potential to sites of early seizure spread that were not included in resection. This mechanism of failure implies that a distributed epileptogenic network rather than a single epileptogenic focus may underlie surgically refractory epilepsy.”

Patients in the new report had epilepsy for a mean of 24.4 years, and 25 (58%) were women; 30 cases (69%) were lesional, and follow-up was at least a year. The contralateral or lateralized seizure spread ranged from 1 to 63 seconds, with a mean of 18.5 seconds. Among patients who failed AMTR, seizure spread occurred at a mean of 7.1 seconds.

Electrographic pattern at onset and location of interictal epileptiform discharges did not predict outcome

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Farooque didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chiari J et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.36.

BALTIMORE – In a review of 43 temporal lobe epilepsy patients at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., anteromedial temporal resection (AMTR) failed in every case in which initial ictal rhythm on scalp EEG spread beyond the medial temporal lobe to other brain regions within 10 seconds.

Among the 33 patients who had no spread on preoperative scalp EEG or who spread in 10 or more seconds, 31 (94%) had a good outcome, meaning they were seizure free or had only auras after AMTR. The findings could mean that scalp EEG can predict surgery outcome.

AMTR works in the majority of patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy, but about 10-20% continue to have seizures. Senior investigator Pue Farooque, DO, from Yale University wanted to find a way to identify patients likely to fail surgery beforehand to help counsel patients on what to expect and also to know when other treatment options might be a better bet.

“If you see seizures are spreading quickly to another area, like the frontal lobe or the temporal neocortex, you could implant RNS [responsive neurostimulation]” instead of doing an ATMR, “and that might improve your outcomes,” she said at the American Epilepsy Society’s annual meeting.

The findings are essentially the same as when the group used intracranial EEG to detect fast spread in a previous report, but scalp EEG is noninvasive and allows for easy preoperative assessment (JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:462-9).

The team also found in their new study that diffuse hypometabolism in the entire temporal lobe on quantitative PET also predicted poor ATMR outcomes (P less than .001), but Dr. Farooque said more work is needed to quantify the finding. The investigators also plan to assess the predictive value of resting functional MRI.

The take home, she said, is that “we can do better” with epilepsy surgery, and “there are noninvasive markers we can use to help guide us.”

It’s unclear why more rapid seizure spread would predict AMTR failure. In the earlier study with intracranial EEG, the investigators said “the results are best explained by attributing epileptogenic potential to sites of early seizure spread that were not included in resection. This mechanism of failure implies that a distributed epileptogenic network rather than a single epileptogenic focus may underlie surgically refractory epilepsy.”

Patients in the new report had epilepsy for a mean of 24.4 years, and 25 (58%) were women; 30 cases (69%) were lesional, and follow-up was at least a year. The contralateral or lateralized seizure spread ranged from 1 to 63 seconds, with a mean of 18.5 seconds. Among patients who failed AMTR, seizure spread occurred at a mean of 7.1 seconds.

Electrographic pattern at onset and location of interictal epileptiform discharges did not predict outcome

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Farooque didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chiari J et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.36.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Outcomes of epilepsy surgery at 1 year may be better among older patients

BALTIMORE – Older patients may have better outcomes at 1 year after resective surgery for epilepsy than the general population does, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. A tendency toward greater prevalence of lesional epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in the older patients in the study population could explain this difference in outcomes. Although surgery might entail greater risks in older patients, the decision to operate should be based on the patient’s inherent risk, and not on his or her age, said Juan S. Bottan, MD, neurosurgery resident at Hospital Pedro De Elizalde in Buenos Aires, and colleagues.

Epilepsy surgery as a treatment for elderly patients is controversial. These patients generally are not considered to be surgical candidates because of concerns about long disease duration and increased surgical risk. Recent literature, however, suggests that elderly patients can benefit from surgery. Lang et al. found that epilepsy surgery success rates can be higher in selected older patients than in younger patients, although older patients may be at greater risk for postoperative hygroma and memory deficits.

Dr. Bottan and colleagues sought to analyze the role of resective surgery in patients older than age 60 years by evaluating surgical outcomes and safety. The investigators retrospectively analyzed 595 patients who underwent resective epilepsy surgery at Western University in London, Ontario, during 1999-2019. Eligible participants had drug-resistant epilepsy that had failed the best medical management. The researchers identified 31 patients aged 60 years or older and randomly selected 60 patients aged 59 years or younger as a control group. Dr. Bottan and colleagues analyzed the population’s characteristics, presurgical evaluations, postoperative outcome, and complications.

The investigators found no significant differences between groups in terms of hemisphere dominance, side of surgery, the ratio of patients with lesional epilepsy to patients with nonlesional epilepsy, and incidence of TLE over extratemporal epilepsy.

Nevertheless, extratemporal epilepsy was more frequent in older patients. Age and duration of epilepsy were significantly greater in older patients, and invasive recording was significantly more common in younger patients.

The most common pathology results in older patients were mesial temporal sclerosis (39%), gliosis (19%), and other (19%). Among younger patients, the most common pathology results were mesial temporal sclerosis (25%), gliosis (25%), and focal cortical dysplasia (15%).

The rates of Engel Class I outcome at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 92.9%, 88.5%, and 94.7% among older patients and 75%, 63.5%, and 75.8% among younger patients, respectively. The difference between groups in Engel Class I outcome at 1 year was statistically significant. Patients with TLE had a better seizure outcome, regardless of age group, but the rate of good outcome was higher among older patients. The rate of complications was higher among older patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bottan JS et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.343.

BALTIMORE – Older patients may have better outcomes at 1 year after resective surgery for epilepsy than the general population does, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. A tendency toward greater prevalence of lesional epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in the older patients in the study population could explain this difference in outcomes. Although surgery might entail greater risks in older patients, the decision to operate should be based on the patient’s inherent risk, and not on his or her age, said Juan S. Bottan, MD, neurosurgery resident at Hospital Pedro De Elizalde in Buenos Aires, and colleagues.

Epilepsy surgery as a treatment for elderly patients is controversial. These patients generally are not considered to be surgical candidates because of concerns about long disease duration and increased surgical risk. Recent literature, however, suggests that elderly patients can benefit from surgery. Lang et al. found that epilepsy surgery success rates can be higher in selected older patients than in younger patients, although older patients may be at greater risk for postoperative hygroma and memory deficits.

Dr. Bottan and colleagues sought to analyze the role of resective surgery in patients older than age 60 years by evaluating surgical outcomes and safety. The investigators retrospectively analyzed 595 patients who underwent resective epilepsy surgery at Western University in London, Ontario, during 1999-2019. Eligible participants had drug-resistant epilepsy that had failed the best medical management. The researchers identified 31 patients aged 60 years or older and randomly selected 60 patients aged 59 years or younger as a control group. Dr. Bottan and colleagues analyzed the population’s characteristics, presurgical evaluations, postoperative outcome, and complications.

The investigators found no significant differences between groups in terms of hemisphere dominance, side of surgery, the ratio of patients with lesional epilepsy to patients with nonlesional epilepsy, and incidence of TLE over extratemporal epilepsy.

Nevertheless, extratemporal epilepsy was more frequent in older patients. Age and duration of epilepsy were significantly greater in older patients, and invasive recording was significantly more common in younger patients.

The most common pathology results in older patients were mesial temporal sclerosis (39%), gliosis (19%), and other (19%). Among younger patients, the most common pathology results were mesial temporal sclerosis (25%), gliosis (25%), and focal cortical dysplasia (15%).

The rates of Engel Class I outcome at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 92.9%, 88.5%, and 94.7% among older patients and 75%, 63.5%, and 75.8% among younger patients, respectively. The difference between groups in Engel Class I outcome at 1 year was statistically significant. Patients with TLE had a better seizure outcome, regardless of age group, but the rate of good outcome was higher among older patients. The rate of complications was higher among older patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bottan JS et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.343.

BALTIMORE – Older patients may have better outcomes at 1 year after resective surgery for epilepsy than the general population does, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. A tendency toward greater prevalence of lesional epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in the older patients in the study population could explain this difference in outcomes. Although surgery might entail greater risks in older patients, the decision to operate should be based on the patient’s inherent risk, and not on his or her age, said Juan S. Bottan, MD, neurosurgery resident at Hospital Pedro De Elizalde in Buenos Aires, and colleagues.

Epilepsy surgery as a treatment for elderly patients is controversial. These patients generally are not considered to be surgical candidates because of concerns about long disease duration and increased surgical risk. Recent literature, however, suggests that elderly patients can benefit from surgery. Lang et al. found that epilepsy surgery success rates can be higher in selected older patients than in younger patients, although older patients may be at greater risk for postoperative hygroma and memory deficits.

Dr. Bottan and colleagues sought to analyze the role of resective surgery in patients older than age 60 years by evaluating surgical outcomes and safety. The investigators retrospectively analyzed 595 patients who underwent resective epilepsy surgery at Western University in London, Ontario, during 1999-2019. Eligible participants had drug-resistant epilepsy that had failed the best medical management. The researchers identified 31 patients aged 60 years or older and randomly selected 60 patients aged 59 years or younger as a control group. Dr. Bottan and colleagues analyzed the population’s characteristics, presurgical evaluations, postoperative outcome, and complications.

The investigators found no significant differences between groups in terms of hemisphere dominance, side of surgery, the ratio of patients with lesional epilepsy to patients with nonlesional epilepsy, and incidence of TLE over extratemporal epilepsy.

Nevertheless, extratemporal epilepsy was more frequent in older patients. Age and duration of epilepsy were significantly greater in older patients, and invasive recording was significantly more common in younger patients.

The most common pathology results in older patients were mesial temporal sclerosis (39%), gliosis (19%), and other (19%). Among younger patients, the most common pathology results were mesial temporal sclerosis (25%), gliosis (25%), and focal cortical dysplasia (15%).

The rates of Engel Class I outcome at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 92.9%, 88.5%, and 94.7% among older patients and 75%, 63.5%, and 75.8% among younger patients, respectively. The difference between groups in Engel Class I outcome at 1 year was statistically significant. Patients with TLE had a better seizure outcome, regardless of age group, but the rate of good outcome was higher among older patients. The rate of complications was higher among older patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bottan JS et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.343.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

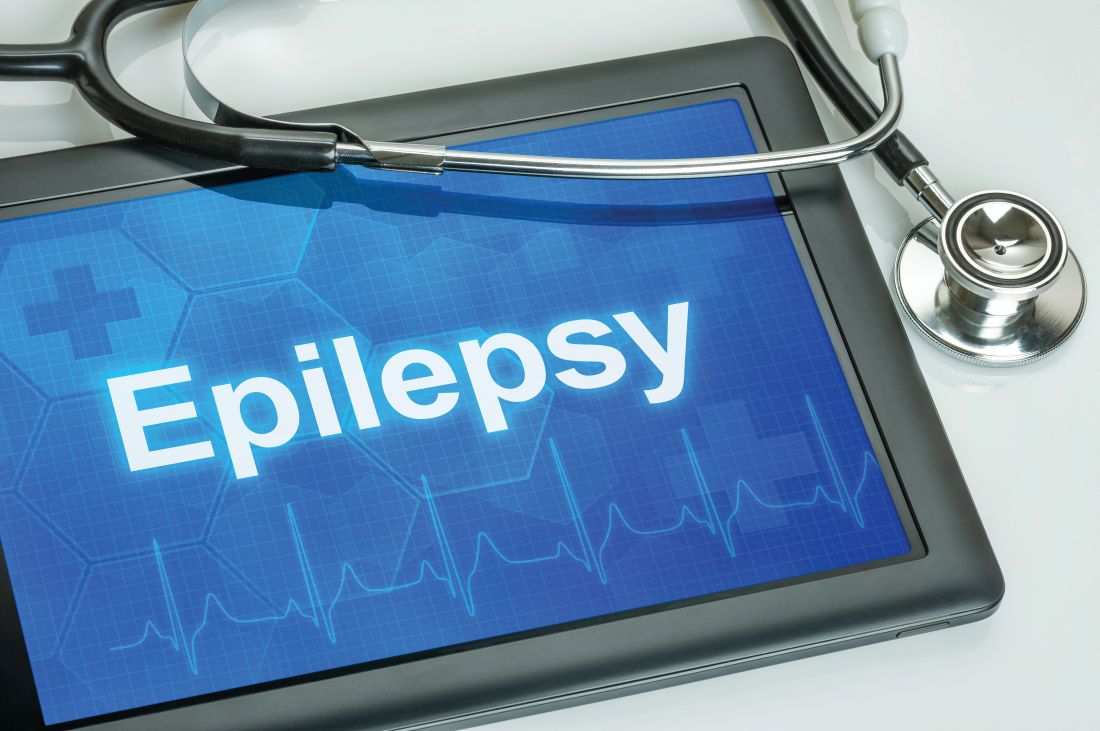

Researchers mine free-text diary entries for seizure cluster insights

BALTIMORE – Free-text diary entries by patients with epilepsy are a “largely untapped” source of information about the frequency and treatment of seizure clusters, researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, patients may describe other clinically relevant concerns such as tiredness, depression, head injury, or seizures while driving, researchers said.

To examine how seizure clusters are reflected in the electronic diaries of patients with epilepsy, Joyce A. Cramer, a clinical research consultant and colleagues examined data from EpiDiary, a set of mobile and Web-based apps designed to help patients with epilepsy manage their medications and record their symptoms. EpiDiary prompts patients to indicate whether they were seizure free, had a seizure, or had a seizure cluster on a given day. Patients also have the ability to enter free-text notes.

“This was the first-ever review of the unstructured, free-text notes,” Ms. Cramer said.

Investigators used lexical analysis to identify free-text comments that potentially were about seizure clusters, based on the use of words such as “lots,” “many,” or “repeat.” Researchers reviewed every flagged comment to confirm whether it pertained to a seizure cluster. They defined a cluster as two or more seizures on a calendar day.

An algorithm flagged 5,955 entries by 1,839 users. Clinician review confirmed that 2,645 of the flagged comments (44.4%) pertained to seizure clusters. Of the confirmed clusters, 512 (19.4%) were found only through the free-text notes and had not been documented through structured data elements such as seizure cluster check-boxes or seizure counts.

“Extra medicine was taken for clusters by 553 users on 3,818 days,” the researchers reported. “This was 30.1% of all users and 56.5% of those commenting on clusters.” In some instances, patients named specific medications, including lorazepam, clonazepam, midazolam, clobazam, rectal diazepam, other diazepam, and clorazepate.

Free-text diary entries could help researchers study various topics. The authors highlighted examples of entries that “contained other clinically relevant information,” including the following:

- Massive ongoing cluster with about 20% apneic events.

- My constant question seems to be: HOW can I function in life when just small outings bring about this incessant tiredness?

- Started feeling like I was having an aura and pulled over.

- Thought about suicide for the first time in a while.

Interpretations of the seizure cluster data are limited, the researchers noted. The algorithm might have missed some free-text comments that were about seizure clusters. And in some instances, researchers used words such as “puffs” to identify seizures when a connection to seizures was not entirely clear. In addition, patients may have used a definition of cluster that was different from the definition used by the investigators.

UCB Pharma and Irody, the company that owns EpiDiary, funded the study. Irody’s founder and president was a coauthor, and another author holds stock or options in Irody. Ms. Cramer consults for Irody, UCB, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Fisher RS et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.424.

BALTIMORE – Free-text diary entries by patients with epilepsy are a “largely untapped” source of information about the frequency and treatment of seizure clusters, researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, patients may describe other clinically relevant concerns such as tiredness, depression, head injury, or seizures while driving, researchers said.

To examine how seizure clusters are reflected in the electronic diaries of patients with epilepsy, Joyce A. Cramer, a clinical research consultant and colleagues examined data from EpiDiary, a set of mobile and Web-based apps designed to help patients with epilepsy manage their medications and record their symptoms. EpiDiary prompts patients to indicate whether they were seizure free, had a seizure, or had a seizure cluster on a given day. Patients also have the ability to enter free-text notes.

“This was the first-ever review of the unstructured, free-text notes,” Ms. Cramer said.

Investigators used lexical analysis to identify free-text comments that potentially were about seizure clusters, based on the use of words such as “lots,” “many,” or “repeat.” Researchers reviewed every flagged comment to confirm whether it pertained to a seizure cluster. They defined a cluster as two or more seizures on a calendar day.

An algorithm flagged 5,955 entries by 1,839 users. Clinician review confirmed that 2,645 of the flagged comments (44.4%) pertained to seizure clusters. Of the confirmed clusters, 512 (19.4%) were found only through the free-text notes and had not been documented through structured data elements such as seizure cluster check-boxes or seizure counts.

“Extra medicine was taken for clusters by 553 users on 3,818 days,” the researchers reported. “This was 30.1% of all users and 56.5% of those commenting on clusters.” In some instances, patients named specific medications, including lorazepam, clonazepam, midazolam, clobazam, rectal diazepam, other diazepam, and clorazepate.

Free-text diary entries could help researchers study various topics. The authors highlighted examples of entries that “contained other clinically relevant information,” including the following:

- Massive ongoing cluster with about 20% apneic events.

- My constant question seems to be: HOW can I function in life when just small outings bring about this incessant tiredness?

- Started feeling like I was having an aura and pulled over.

- Thought about suicide for the first time in a while.

Interpretations of the seizure cluster data are limited, the researchers noted. The algorithm might have missed some free-text comments that were about seizure clusters. And in some instances, researchers used words such as “puffs” to identify seizures when a connection to seizures was not entirely clear. In addition, patients may have used a definition of cluster that was different from the definition used by the investigators.

UCB Pharma and Irody, the company that owns EpiDiary, funded the study. Irody’s founder and president was a coauthor, and another author holds stock or options in Irody. Ms. Cramer consults for Irody, UCB, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Fisher RS et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.424.

BALTIMORE – Free-text diary entries by patients with epilepsy are a “largely untapped” source of information about the frequency and treatment of seizure clusters, researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, patients may describe other clinically relevant concerns such as tiredness, depression, head injury, or seizures while driving, researchers said.

To examine how seizure clusters are reflected in the electronic diaries of patients with epilepsy, Joyce A. Cramer, a clinical research consultant and colleagues examined data from EpiDiary, a set of mobile and Web-based apps designed to help patients with epilepsy manage their medications and record their symptoms. EpiDiary prompts patients to indicate whether they were seizure free, had a seizure, or had a seizure cluster on a given day. Patients also have the ability to enter free-text notes.

“This was the first-ever review of the unstructured, free-text notes,” Ms. Cramer said.

Investigators used lexical analysis to identify free-text comments that potentially were about seizure clusters, based on the use of words such as “lots,” “many,” or “repeat.” Researchers reviewed every flagged comment to confirm whether it pertained to a seizure cluster. They defined a cluster as two or more seizures on a calendar day.

An algorithm flagged 5,955 entries by 1,839 users. Clinician review confirmed that 2,645 of the flagged comments (44.4%) pertained to seizure clusters. Of the confirmed clusters, 512 (19.4%) were found only through the free-text notes and had not been documented through structured data elements such as seizure cluster check-boxes or seizure counts.

“Extra medicine was taken for clusters by 553 users on 3,818 days,” the researchers reported. “This was 30.1% of all users and 56.5% of those commenting on clusters.” In some instances, patients named specific medications, including lorazepam, clonazepam, midazolam, clobazam, rectal diazepam, other diazepam, and clorazepate.

Free-text diary entries could help researchers study various topics. The authors highlighted examples of entries that “contained other clinically relevant information,” including the following:

- Massive ongoing cluster with about 20% apneic events.

- My constant question seems to be: HOW can I function in life when just small outings bring about this incessant tiredness?

- Started feeling like I was having an aura and pulled over.

- Thought about suicide for the first time in a while.

Interpretations of the seizure cluster data are limited, the researchers noted. The algorithm might have missed some free-text comments that were about seizure clusters. And in some instances, researchers used words such as “puffs” to identify seizures when a connection to seizures was not entirely clear. In addition, patients may have used a definition of cluster that was different from the definition used by the investigators.

UCB Pharma and Irody, the company that owns EpiDiary, funded the study. Irody’s founder and president was a coauthor, and another author holds stock or options in Irody. Ms. Cramer consults for Irody, UCB, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Fisher RS et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.424.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Skip CTs for breakthrough seizures in chronic epilepsy

BALTIMORE – Head CTs for breakthrough seizures in chronic epilepsy are useful for known structural triggers such as brain tumors, but they don’t change management for most patients, according to a review from the SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., emergency department.

“Nonselective use of ED neuroimaging in patients with no new neurological findings” and no known structural problem, is “very low yield, and increases the use of hospital resources and radiation exposure without impacting the immediate care,” concluded investigators led by Shahram Izadyar, MD, an epileptologist and associate professor of neurology at the university.

In short, CTs for breakthrough seizures – routine in many EDs – usually are a waste of time and money. Absent a known structural cause, “there really isn’t a reason to do imaging,” he said at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

Dr. Izadyar wanted to look into the issue after noticing how common CTs were among his breakthrough patients. He and his team reviewed 90 adults with an established diagnosis of epilepsy and on at least one antiepileptic who presented to the university ED for breakthrough seizures during 2017-2018; 39 (43.3%) had head CTs, 51 (56.7%) did not.

CT changed management in three of the four patients (4.4%) who had a known brain tumor, leading, for instance, to steroids for increased tumor edema. The rest of the patients had nonfocal exams, and imaging had no impact on management.

There was no rhyme or reason why some people got CTs and others didn’t; it seemed to be dependent on the provider. Defensive medicine probably had something to do with it, as well as saving time by ordering a CT instead of doing a neurologic exam, Dr. Izadyar said.

People aren’t going to stop doing defensive medicine, but even a small reduction in unnecessary CTs would “be a positive change.” There’s the cost issue, but also the radiation exposure, which is considerable when people end up in the ED every few months for breakthrough seizures, he said.

There were no differences between the CT and no-CT groups in the suspected causes of breakthroughs (P = .93). About half the cases were probably because of noncompliance, about a quarter from sleep deprivation, and the rest from a change in seizure medication or some other issue.

Dr. Izadyar said the next step is taking the findings to his ED colleagues, and perhaps calculating how much money the university would save by skipping CTs in chronic epilepsy patients with no known structural problem.

There were slightly more men than women in the study, and the mean age was 38 years.

There was no industry funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.213.

BALTIMORE – Head CTs for breakthrough seizures in chronic epilepsy are useful for known structural triggers such as brain tumors, but they don’t change management for most patients, according to a review from the SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., emergency department.

“Nonselective use of ED neuroimaging in patients with no new neurological findings” and no known structural problem, is “very low yield, and increases the use of hospital resources and radiation exposure without impacting the immediate care,” concluded investigators led by Shahram Izadyar, MD, an epileptologist and associate professor of neurology at the university.

In short, CTs for breakthrough seizures – routine in many EDs – usually are a waste of time and money. Absent a known structural cause, “there really isn’t a reason to do imaging,” he said at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

Dr. Izadyar wanted to look into the issue after noticing how common CTs were among his breakthrough patients. He and his team reviewed 90 adults with an established diagnosis of epilepsy and on at least one antiepileptic who presented to the university ED for breakthrough seizures during 2017-2018; 39 (43.3%) had head CTs, 51 (56.7%) did not.

CT changed management in three of the four patients (4.4%) who had a known brain tumor, leading, for instance, to steroids for increased tumor edema. The rest of the patients had nonfocal exams, and imaging had no impact on management.

There was no rhyme or reason why some people got CTs and others didn’t; it seemed to be dependent on the provider. Defensive medicine probably had something to do with it, as well as saving time by ordering a CT instead of doing a neurologic exam, Dr. Izadyar said.

People aren’t going to stop doing defensive medicine, but even a small reduction in unnecessary CTs would “be a positive change.” There’s the cost issue, but also the radiation exposure, which is considerable when people end up in the ED every few months for breakthrough seizures, he said.

There were no differences between the CT and no-CT groups in the suspected causes of breakthroughs (P = .93). About half the cases were probably because of noncompliance, about a quarter from sleep deprivation, and the rest from a change in seizure medication or some other issue.

Dr. Izadyar said the next step is taking the findings to his ED colleagues, and perhaps calculating how much money the university would save by skipping CTs in chronic epilepsy patients with no known structural problem.

There were slightly more men than women in the study, and the mean age was 38 years.

There was no industry funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.213.

BALTIMORE – Head CTs for breakthrough seizures in chronic epilepsy are useful for known structural triggers such as brain tumors, but they don’t change management for most patients, according to a review from the SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., emergency department.

“Nonselective use of ED neuroimaging in patients with no new neurological findings” and no known structural problem, is “very low yield, and increases the use of hospital resources and radiation exposure without impacting the immediate care,” concluded investigators led by Shahram Izadyar, MD, an epileptologist and associate professor of neurology at the university.

In short, CTs for breakthrough seizures – routine in many EDs – usually are a waste of time and money. Absent a known structural cause, “there really isn’t a reason to do imaging,” he said at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

Dr. Izadyar wanted to look into the issue after noticing how common CTs were among his breakthrough patients. He and his team reviewed 90 adults with an established diagnosis of epilepsy and on at least one antiepileptic who presented to the university ED for breakthrough seizures during 2017-2018; 39 (43.3%) had head CTs, 51 (56.7%) did not.

CT changed management in three of the four patients (4.4%) who had a known brain tumor, leading, for instance, to steroids for increased tumor edema. The rest of the patients had nonfocal exams, and imaging had no impact on management.

There was no rhyme or reason why some people got CTs and others didn’t; it seemed to be dependent on the provider. Defensive medicine probably had something to do with it, as well as saving time by ordering a CT instead of doing a neurologic exam, Dr. Izadyar said.

People aren’t going to stop doing defensive medicine, but even a small reduction in unnecessary CTs would “be a positive change.” There’s the cost issue, but also the radiation exposure, which is considerable when people end up in the ED every few months for breakthrough seizures, he said.

There were no differences between the CT and no-CT groups in the suspected causes of breakthroughs (P = .93). About half the cases were probably because of noncompliance, about a quarter from sleep deprivation, and the rest from a change in seizure medication or some other issue.

Dr. Izadyar said the next step is taking the findings to his ED colleagues, and perhaps calculating how much money the university would save by skipping CTs in chronic epilepsy patients with no known structural problem.

There were slightly more men than women in the study, and the mean age was 38 years.

There was no industry funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.213.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Trial finds three drugs equally effective for established status epilepticus

according to a study published Nov. 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine. The effectiveness and safety of the intravenous medications do not differ significantly, the researchers wrote.

“Having three equally effective second-line intravenous medications means that the clinician may choose a drug that takes into account individual situations,” wrote Phil E.M. Smith, MD, in an accompanying editorial (doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1913775). Clinicians may consider “factors such as the presumed underlying cause of status epilepticus; coexisting conditions, including allergy, liver and renal disease, hypotension, propensity to cardiac arrhythmia, and alcohol and drug dependence; the currently prescribed antiepileptic treatment; the cost of the medication; and governmental agency drug approval,” said Dr. Smith, who is affiliated with University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff.

A gap in guidance

Evidence supports benzodiazepines as the initial treatment for status epilepticus, but these drugs do not work in up to a third of patients, said first study author Jaideep Kapur, MBBS, PhD, and colleagues. “Clinical guidelines emphasize the need for rapid control of benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus but do not provide guidance regarding the choice of medication on the basis of either efficacy or safety,” they wrote. Dr. Kapur is a professor of neurology and the director of UVA Brain Institute at University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate are the three most commonly used medications for benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus. The Food and Drug Administration has labeled fosphenytoin for this indication in adults, and none of the drugs is approved for children. To determine the superiority or inferiority of these medications, the researchers conducted the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT). The blinded, comparative-effectiveness trial enrolled 384 patients at 57 hospital EDs in the United States. Patients were aged 2 years or older, had received a generally accepted cumulative dose of benzodiazepines for generalized convulsive seizures lasting more than 5 minutes and continued to have persistent or recurrent convulsions between 5-30 minutes after the last dose of benzodiazepine.

Patients randomly received one of the three trial drugs, which “were identical in appearance, formulation, packaging, and administration,” the authors said. The primary outcome was absence of clinically apparent seizures and improving responsiveness at 60 minutes after the start of the infusion without administration of additional anticonvulsant medication. ED physicians determined the presence of seizure and improvement in responsiveness.

Trial was stopped for futility

The trial included 400 enrollments of 384 unique patients during 2015-2017. Sixteen patients were enrolled twice, and their second enrollments were not included in the intention-to-treat analysis. A planned interim analysis after 400 enrollments to assess the likelihood of success or futility found that the trial had met the futility criterion. “There was a 1% chance of showing a most effective or least effective treatment if the trial were to continue to the maximum sample size” of 795 patients, Dr. Kapur and coauthors wrote. The researchers continued enrollment in a pediatric subcohort for a planned subgroup analysis by age.

In all, 55% of the patients were male, 43% were black, and 16% were Hispanic. The population was 39% children and adolescents, 48% adults aged 18-65 years, and 13% older than 65 years. Most patients had a final diagnosis of status epilepticus (87%). Other final diagnoses included psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (10%).

At 60 minutes after treatment administration, absence of seizures and improved responsiveness occurred in 47% of patients who received levetiracetam, 45% who received fosphenytoin, and 46% who received valproate.

In 39 patients for whom the researchers had reliable information about time to seizure cessation, median time to seizure cessation numerically favored valproate (7 minutes for valproate vs. 10.5 minutes for levetiracetam vs. 11.7 minutes for fosphenytoin), but the number of patients was limited, the authors noted.

“Hypotension and endotracheal intubation were more frequent with fosphenytoin than with the other two drugs, and deaths were more frequent with levetiracetam, but these differences were not significant,” wrote Dr. Kapur and colleagues. Seven patients who received levetiracetam died, compared with three who received fosphenytoin and two who received valproate. Life-threatening hypotension occurred in 3.2% of patients who received fosphenytoin, compared with 1.6% who received valproate and 0.7% who received levetiracetam. Endotracheal intubation occurred in 26.4% or patients who received fosphenytoin, compared with 20% of patients in the levetiracetam group and 16.8% in the valproate group.

The trial’s limitations include the enrollment of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and the use of clinical instead of electroencephalographic criteria for the primary outcome measure, the investigators wrote.

Dr. Smith noted that third- and fourth-line management of status epilepticus is not supported by high-quality evidence, and further studies are needed. Given the evidence from ESETT, “the practical challenge for the management of status epilepticus remains the same as in the past: ensuring that clinicians are familiar with, and follow, a treatment protocol,” he said.

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Kapur had no financial disclosures. A coauthor holds a patent on intravenous carbamazepine and intellectual property on intravenous topiramate. Other coauthors have ties to pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

Dr. Smith is coeditor of Practical Neurology and a member of the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines committee for epilepsy.

SOURCE: Kapur J et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795.

according to a study published Nov. 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine. The effectiveness and safety of the intravenous medications do not differ significantly, the researchers wrote.

“Having three equally effective second-line intravenous medications means that the clinician may choose a drug that takes into account individual situations,” wrote Phil E.M. Smith, MD, in an accompanying editorial (doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1913775). Clinicians may consider “factors such as the presumed underlying cause of status epilepticus; coexisting conditions, including allergy, liver and renal disease, hypotension, propensity to cardiac arrhythmia, and alcohol and drug dependence; the currently prescribed antiepileptic treatment; the cost of the medication; and governmental agency drug approval,” said Dr. Smith, who is affiliated with University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff.

A gap in guidance

Evidence supports benzodiazepines as the initial treatment for status epilepticus, but these drugs do not work in up to a third of patients, said first study author Jaideep Kapur, MBBS, PhD, and colleagues. “Clinical guidelines emphasize the need for rapid control of benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus but do not provide guidance regarding the choice of medication on the basis of either efficacy or safety,” they wrote. Dr. Kapur is a professor of neurology and the director of UVA Brain Institute at University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate are the three most commonly used medications for benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus. The Food and Drug Administration has labeled fosphenytoin for this indication in adults, and none of the drugs is approved for children. To determine the superiority or inferiority of these medications, the researchers conducted the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT). The blinded, comparative-effectiveness trial enrolled 384 patients at 57 hospital EDs in the United States. Patients were aged 2 years or older, had received a generally accepted cumulative dose of benzodiazepines for generalized convulsive seizures lasting more than 5 minutes and continued to have persistent or recurrent convulsions between 5-30 minutes after the last dose of benzodiazepine.

Patients randomly received one of the three trial drugs, which “were identical in appearance, formulation, packaging, and administration,” the authors said. The primary outcome was absence of clinically apparent seizures and improving responsiveness at 60 minutes after the start of the infusion without administration of additional anticonvulsant medication. ED physicians determined the presence of seizure and improvement in responsiveness.

Trial was stopped for futility

The trial included 400 enrollments of 384 unique patients during 2015-2017. Sixteen patients were enrolled twice, and their second enrollments were not included in the intention-to-treat analysis. A planned interim analysis after 400 enrollments to assess the likelihood of success or futility found that the trial had met the futility criterion. “There was a 1% chance of showing a most effective or least effective treatment if the trial were to continue to the maximum sample size” of 795 patients, Dr. Kapur and coauthors wrote. The researchers continued enrollment in a pediatric subcohort for a planned subgroup analysis by age.

In all, 55% of the patients were male, 43% were black, and 16% were Hispanic. The population was 39% children and adolescents, 48% adults aged 18-65 years, and 13% older than 65 years. Most patients had a final diagnosis of status epilepticus (87%). Other final diagnoses included psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (10%).

At 60 minutes after treatment administration, absence of seizures and improved responsiveness occurred in 47% of patients who received levetiracetam, 45% who received fosphenytoin, and 46% who received valproate.

In 39 patients for whom the researchers had reliable information about time to seizure cessation, median time to seizure cessation numerically favored valproate (7 minutes for valproate vs. 10.5 minutes for levetiracetam vs. 11.7 minutes for fosphenytoin), but the number of patients was limited, the authors noted.

“Hypotension and endotracheal intubation were more frequent with fosphenytoin than with the other two drugs, and deaths were more frequent with levetiracetam, but these differences were not significant,” wrote Dr. Kapur and colleagues. Seven patients who received levetiracetam died, compared with three who received fosphenytoin and two who received valproate. Life-threatening hypotension occurred in 3.2% of patients who received fosphenytoin, compared with 1.6% who received valproate and 0.7% who received levetiracetam. Endotracheal intubation occurred in 26.4% or patients who received fosphenytoin, compared with 20% of patients in the levetiracetam group and 16.8% in the valproate group.

The trial’s limitations include the enrollment of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and the use of clinical instead of electroencephalographic criteria for the primary outcome measure, the investigators wrote.