User login

Surgery vs radiofrequency ablation: Achieving better recurrence-free survival in small HCC

Key clinical point: Patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) show a comparable improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) after undergoing surgery or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Main finding: The median RFS of patients who had undergone surgery was not significantly different from that of patients receiving RFA (3.46 years vs 3.04 years; hazard ratio, 0.92; P = .58).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 SURF-trial including 301 patients aged between 20 and 80 years with the largest HCC diameter ≤3 cm and ≤3 HCC nodules who were randomly assigned (1:1) to undergo either surgery (n=150) or RFA (n=151).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer and the Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Clinical Cancer Research. Some of the authors declared receiving lecture fees or research funds from or serving as an advisor for various companies. A few authors reported being on the editorial team/board of Liver Cancer.

Source: Takayama T et al. Liver Cancer. 2021 Dec 29. doi: 10.1159/000521665.

Key clinical point: Patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) show a comparable improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) after undergoing surgery or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Main finding: The median RFS of patients who had undergone surgery was not significantly different from that of patients receiving RFA (3.46 years vs 3.04 years; hazard ratio, 0.92; P = .58).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 SURF-trial including 301 patients aged between 20 and 80 years with the largest HCC diameter ≤3 cm and ≤3 HCC nodules who were randomly assigned (1:1) to undergo either surgery (n=150) or RFA (n=151).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer and the Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Clinical Cancer Research. Some of the authors declared receiving lecture fees or research funds from or serving as an advisor for various companies. A few authors reported being on the editorial team/board of Liver Cancer.

Source: Takayama T et al. Liver Cancer. 2021 Dec 29. doi: 10.1159/000521665.

Key clinical point: Patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) show a comparable improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) after undergoing surgery or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Main finding: The median RFS of patients who had undergone surgery was not significantly different from that of patients receiving RFA (3.46 years vs 3.04 years; hazard ratio, 0.92; P = .58).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 SURF-trial including 301 patients aged between 20 and 80 years with the largest HCC diameter ≤3 cm and ≤3 HCC nodules who were randomly assigned (1:1) to undergo either surgery (n=150) or RFA (n=151).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer and the Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Clinical Cancer Research. Some of the authors declared receiving lecture fees or research funds from or serving as an advisor for various companies. A few authors reported being on the editorial team/board of Liver Cancer.

Source: Takayama T et al. Liver Cancer. 2021 Dec 29. doi: 10.1159/000521665.

ABO blood group system may dictate the outcome of liver transplantation in HCC

Key clinical point: The oncological outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver transplantation (LT) is strongly affected by the ABO blood group system.

Main finding: Blood group A showed an independent association with increased tumor recurrence risk (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.574; P = .034) with group A vs non-A recipients having higher 5-year tumor recurrence rates (20.1% vs 13.2%; aHR, 1.66; P = .011) and lower 5-year recurrence-free survival rates (66.8% vs 71.3%; aHR, 1.38; P = .045).

Study details: The data are derived from a multicentric retrospective observational study including 925 adult patients with HCC who underwent LT, of whom 406, 94, 380, and 45 had blood group A, B, O, and AB, respectively.

Disclosures: The authors reported no funding source or conflict of interests.

Source: Kayvan M et al. Transplantation. 2021 Dec 27. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004004.

Key clinical point: The oncological outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver transplantation (LT) is strongly affected by the ABO blood group system.

Main finding: Blood group A showed an independent association with increased tumor recurrence risk (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.574; P = .034) with group A vs non-A recipients having higher 5-year tumor recurrence rates (20.1% vs 13.2%; aHR, 1.66; P = .011) and lower 5-year recurrence-free survival rates (66.8% vs 71.3%; aHR, 1.38; P = .045).

Study details: The data are derived from a multicentric retrospective observational study including 925 adult patients with HCC who underwent LT, of whom 406, 94, 380, and 45 had blood group A, B, O, and AB, respectively.

Disclosures: The authors reported no funding source or conflict of interests.

Source: Kayvan M et al. Transplantation. 2021 Dec 27. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004004.

Key clinical point: The oncological outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent liver transplantation (LT) is strongly affected by the ABO blood group system.

Main finding: Blood group A showed an independent association with increased tumor recurrence risk (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.574; P = .034) with group A vs non-A recipients having higher 5-year tumor recurrence rates (20.1% vs 13.2%; aHR, 1.66; P = .011) and lower 5-year recurrence-free survival rates (66.8% vs 71.3%; aHR, 1.38; P = .045).

Study details: The data are derived from a multicentric retrospective observational study including 925 adult patients with HCC who underwent LT, of whom 406, 94, 380, and 45 had blood group A, B, O, and AB, respectively.

Disclosures: The authors reported no funding source or conflict of interests.

Source: Kayvan M et al. Transplantation. 2021 Dec 27. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004004.

Ketamine nasal spray provides slow-acting relief for cluster headache attacks

, a pilot study has found, though it did not reduce pain intensity as quickly as initially anticipated.

“In clinical practice, intranasal ketamine might be a valuable tool for severely affected patients with insufficient response or intolerance to current first-line treatment,” wrote Anja S. Petersen, MD, of the Danish Headache Center at Rigshospitalet-Glostrup (Denmark) and her coauthors. The study was published online ahead of print in Headache.

To assess ketamine’s safety and efficacy in treating cluster headache attacks, the researchers launched a single-center, open-label, proof-of-concept study of 23 Danish patients with chronic cluster headache. Their average age was 51, 70% were males, and their mean disease duration was 18 years. Twenty of the participants suffered a spontaneous attack while under in-hospital observation and were treated with 15 mg of intranasal ketamine every 6 minutes to a maximum of five times.

Fifteen minutes after ketamine was administered, mean pain intensity (±SD) was reduced from 7.2 (±1.3) to 6.1 (±3.1) on an 11-point numeric rating scale, equivalent to a 15% reduction and well below the primary endpoint of a 50% or greater reduction. Only 4 of the 20 participants had a reduction of 50% or more, and 4 patients chose rescue medication at 15 minutes. However, at 30 minutes pain intensity was reduced by 59% (mean difference 4.3, 95% confidence interval, 2.4-6.2, P > 0.001), with 11 out of 16 participants scoring a 4 or below.

Eight of the 20 participants reported feeling complete relief from the ketamine nasal spray, while 6 participants reported feeling no effects. Half of the patients said they preferred ketamine to oxygen and/or sumatriptan injection. Seventeen patients (83%) reported side effects, but 12 of them classified their side effects as “few.” No serious adverse events were identified, with the most common adverse events being dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea/vomiting, and paresthesia.

Debating ketamine’s potential for cluster headache patients

“I’m not crazy about the prospects,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., in an interview. “It was an admirable proof-of-concept trial, and well worth doing. These are desperate patients. But if the aim was to decrease pain intensity within 15 minutes for cluster patients without side effects, this clearly did not do that,” Dr. Tepper said.

“In a sense, this study was to evaluate whether glutamate might be a target for chronic cluster headache, to determine if blocking NMDA glutamate receptors by ketamine would be effective,” Dr. Tepper said. “And I must say, I’m not very impressed.”

He noted his concerns about the study – including 30 minutes being an “unacceptable” wait for patients undergoing a cluster attack, the 20% of patients who required a rescue at 15 minutes, and the various side effects that come with ketamine in nasal form – and said the results did not sway him to consider ketamine a practical option for cluster headache patients.

“You add all of that up, and I would say this was an equivocal study,” he said. “There might be enough there to be worth studying in episodic cluster rather than chronic cluster; there might be enough to consider a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. But it’s not something that I would ring the bell at Wall Street about.”

“The acute treatment of a patient with chronic cluster headache is a real problem for us headache specialists,” added Alan Rapoport, MD, professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the International Headache Society, in an interview. “Cluster headache is probably the worst pain we deal with; women who’ve gone through childbirth say that cluster headache is worse. So it’s very reasonable to have tried.”

“It’s not an impressive finding,” he said, “but it does indicate that there’s some value here. Maybe they need to change the dose; maybe they need to get it in faster by doing something tricky like combining the drug with another substance that will make it attach to the nasal mucosa better. I urge them to study it again, and I hope that they come up with better results the next time, because what they attempted to study is absolutely vital.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a homogeneous patient population and the lack of placebo-controlled verification of effect after 30 minutes. They added, however, that a pilot study like this provides “critical information and paves the way for subsequent placebo-controlled studies.” They also admitted that “daily usage [of ketamine] seems suboptimal” because of the potential of patients becoming addicted.

The study was funded by CCH Pharmaceuticals. Several authors reported receiving speaker’s fees and being subinvestigators in trials run by various pharmaceutical companies, including CCH Pharmaceuticals.

, a pilot study has found, though it did not reduce pain intensity as quickly as initially anticipated.

“In clinical practice, intranasal ketamine might be a valuable tool for severely affected patients with insufficient response or intolerance to current first-line treatment,” wrote Anja S. Petersen, MD, of the Danish Headache Center at Rigshospitalet-Glostrup (Denmark) and her coauthors. The study was published online ahead of print in Headache.

To assess ketamine’s safety and efficacy in treating cluster headache attacks, the researchers launched a single-center, open-label, proof-of-concept study of 23 Danish patients with chronic cluster headache. Their average age was 51, 70% were males, and their mean disease duration was 18 years. Twenty of the participants suffered a spontaneous attack while under in-hospital observation and were treated with 15 mg of intranasal ketamine every 6 minutes to a maximum of five times.

Fifteen minutes after ketamine was administered, mean pain intensity (±SD) was reduced from 7.2 (±1.3) to 6.1 (±3.1) on an 11-point numeric rating scale, equivalent to a 15% reduction and well below the primary endpoint of a 50% or greater reduction. Only 4 of the 20 participants had a reduction of 50% or more, and 4 patients chose rescue medication at 15 minutes. However, at 30 minutes pain intensity was reduced by 59% (mean difference 4.3, 95% confidence interval, 2.4-6.2, P > 0.001), with 11 out of 16 participants scoring a 4 or below.

Eight of the 20 participants reported feeling complete relief from the ketamine nasal spray, while 6 participants reported feeling no effects. Half of the patients said they preferred ketamine to oxygen and/or sumatriptan injection. Seventeen patients (83%) reported side effects, but 12 of them classified their side effects as “few.” No serious adverse events were identified, with the most common adverse events being dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea/vomiting, and paresthesia.

Debating ketamine’s potential for cluster headache patients

“I’m not crazy about the prospects,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., in an interview. “It was an admirable proof-of-concept trial, and well worth doing. These are desperate patients. But if the aim was to decrease pain intensity within 15 minutes for cluster patients without side effects, this clearly did not do that,” Dr. Tepper said.

“In a sense, this study was to evaluate whether glutamate might be a target for chronic cluster headache, to determine if blocking NMDA glutamate receptors by ketamine would be effective,” Dr. Tepper said. “And I must say, I’m not very impressed.”

He noted his concerns about the study – including 30 minutes being an “unacceptable” wait for patients undergoing a cluster attack, the 20% of patients who required a rescue at 15 minutes, and the various side effects that come with ketamine in nasal form – and said the results did not sway him to consider ketamine a practical option for cluster headache patients.

“You add all of that up, and I would say this was an equivocal study,” he said. “There might be enough there to be worth studying in episodic cluster rather than chronic cluster; there might be enough to consider a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. But it’s not something that I would ring the bell at Wall Street about.”

“The acute treatment of a patient with chronic cluster headache is a real problem for us headache specialists,” added Alan Rapoport, MD, professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the International Headache Society, in an interview. “Cluster headache is probably the worst pain we deal with; women who’ve gone through childbirth say that cluster headache is worse. So it’s very reasonable to have tried.”

“It’s not an impressive finding,” he said, “but it does indicate that there’s some value here. Maybe they need to change the dose; maybe they need to get it in faster by doing something tricky like combining the drug with another substance that will make it attach to the nasal mucosa better. I urge them to study it again, and I hope that they come up with better results the next time, because what they attempted to study is absolutely vital.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a homogeneous patient population and the lack of placebo-controlled verification of effect after 30 minutes. They added, however, that a pilot study like this provides “critical information and paves the way for subsequent placebo-controlled studies.” They also admitted that “daily usage [of ketamine] seems suboptimal” because of the potential of patients becoming addicted.

The study was funded by CCH Pharmaceuticals. Several authors reported receiving speaker’s fees and being subinvestigators in trials run by various pharmaceutical companies, including CCH Pharmaceuticals.

, a pilot study has found, though it did not reduce pain intensity as quickly as initially anticipated.

“In clinical practice, intranasal ketamine might be a valuable tool for severely affected patients with insufficient response or intolerance to current first-line treatment,” wrote Anja S. Petersen, MD, of the Danish Headache Center at Rigshospitalet-Glostrup (Denmark) and her coauthors. The study was published online ahead of print in Headache.

To assess ketamine’s safety and efficacy in treating cluster headache attacks, the researchers launched a single-center, open-label, proof-of-concept study of 23 Danish patients with chronic cluster headache. Their average age was 51, 70% were males, and their mean disease duration was 18 years. Twenty of the participants suffered a spontaneous attack while under in-hospital observation and were treated with 15 mg of intranasal ketamine every 6 minutes to a maximum of five times.

Fifteen minutes after ketamine was administered, mean pain intensity (±SD) was reduced from 7.2 (±1.3) to 6.1 (±3.1) on an 11-point numeric rating scale, equivalent to a 15% reduction and well below the primary endpoint of a 50% or greater reduction. Only 4 of the 20 participants had a reduction of 50% or more, and 4 patients chose rescue medication at 15 minutes. However, at 30 minutes pain intensity was reduced by 59% (mean difference 4.3, 95% confidence interval, 2.4-6.2, P > 0.001), with 11 out of 16 participants scoring a 4 or below.

Eight of the 20 participants reported feeling complete relief from the ketamine nasal spray, while 6 participants reported feeling no effects. Half of the patients said they preferred ketamine to oxygen and/or sumatriptan injection. Seventeen patients (83%) reported side effects, but 12 of them classified their side effects as “few.” No serious adverse events were identified, with the most common adverse events being dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea/vomiting, and paresthesia.

Debating ketamine’s potential for cluster headache patients

“I’m not crazy about the prospects,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., in an interview. “It was an admirable proof-of-concept trial, and well worth doing. These are desperate patients. But if the aim was to decrease pain intensity within 15 minutes for cluster patients without side effects, this clearly did not do that,” Dr. Tepper said.

“In a sense, this study was to evaluate whether glutamate might be a target for chronic cluster headache, to determine if blocking NMDA glutamate receptors by ketamine would be effective,” Dr. Tepper said. “And I must say, I’m not very impressed.”

He noted his concerns about the study – including 30 minutes being an “unacceptable” wait for patients undergoing a cluster attack, the 20% of patients who required a rescue at 15 minutes, and the various side effects that come with ketamine in nasal form – and said the results did not sway him to consider ketamine a practical option for cluster headache patients.

“You add all of that up, and I would say this was an equivocal study,” he said. “There might be enough there to be worth studying in episodic cluster rather than chronic cluster; there might be enough to consider a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. But it’s not something that I would ring the bell at Wall Street about.”

“The acute treatment of a patient with chronic cluster headache is a real problem for us headache specialists,” added Alan Rapoport, MD, professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the International Headache Society, in an interview. “Cluster headache is probably the worst pain we deal with; women who’ve gone through childbirth say that cluster headache is worse. So it’s very reasonable to have tried.”

“It’s not an impressive finding,” he said, “but it does indicate that there’s some value here. Maybe they need to change the dose; maybe they need to get it in faster by doing something tricky like combining the drug with another substance that will make it attach to the nasal mucosa better. I urge them to study it again, and I hope that they come up with better results the next time, because what they attempted to study is absolutely vital.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a homogeneous patient population and the lack of placebo-controlled verification of effect after 30 minutes. They added, however, that a pilot study like this provides “critical information and paves the way for subsequent placebo-controlled studies.” They also admitted that “daily usage [of ketamine] seems suboptimal” because of the potential of patients becoming addicted.

The study was funded by CCH Pharmaceuticals. Several authors reported receiving speaker’s fees and being subinvestigators in trials run by various pharmaceutical companies, including CCH Pharmaceuticals.

FROM HEADACHE

CVS Caremark formulary change freezes out apixaban

Patients looking to refill a prescription for apixaban (Eliquis) through CVS Caremark may be in for a surprise following its decision to exclude the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) from its formulary starting Jan. 1.

The move leaves just one DOAC, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), on CVS’ commercial formulary and is being assailed as the latest example of “nonmedical switching” used by health insurers to control costs.

In a letter to CVS Caremark backed by 14 provider and patient organizations, the nonprofit Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health (PACH) calls on the pharmacy chain to reverse its “dangerously disruptive” decision to force stable patients at high risk of cardiovascular events to switch anticoagulation, without an apparent option to be grandfathered into the new plan.

PACH president Dharmesh Patel, MD, Stern Cardiovascular Center, Memphis, called the formulary change “reckless and irresponsible, especially because the decision is not based in science and evidence, but on budgets. Patients and their health care providers, not insurance companies, need to be trusted to determine what medication is best,” he said in a statement.

Craig Beavers, PharmD, vice president of Baptist Health Paducah, Kentucky, said that, as chair of the American College of Cardiology’s Cardiovascular Team Section, he and other organizations have met with CVS Caremark medical leadership to advocate for patients and to understand the company’s perspective.

“The underlying driver is cost,” he told this news organization.

Current guidelines recommend DOACs in general for a variety of indications, including to reduce the risk of stroke and embolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and to prevent deep vein thrombosis, but there are select instances where a particular DOAC might be more appropriate, he observed.

“Apixaban may be better for a patient with a history of GI bleeding because there’s less GI bleeding, but the guidelines don’t necessarily spell those things out,” Dr. Beavers said. “That’s where the clinician should advocate for their patient and, unfortunately, they are making their decision strictly based off the guidelines.”

Requests to speak with medical officers at CVS Caremark went unanswered, but its executive director of communications, Christina Peaslee, told this news organization that the formulary decision “maintains clinically appropriate, cost-effective prescription coverage” for its clients and members.

“Both the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society and 2021 CHEST guidelines recommend DOACs over warfarin for treatment of various cardiology conditions such as atrial fibrillation, but neither list a specific agent as preferred – showing that consensus clinical guidelines do not favor one over the other,” she said in an email. “Further, Xarelto has more FDA-approved indications than Eliquis (e.g., Xarelto is approved for a reduction in risk of major CV events in patients with CAD or PAD) in addition to all the same FDA indications as Eliquis.”

Ms. Peaslee pointed out that all formulary changes are evaluated by an external medical expert specializing in the disease state, followed by review and approval by an independent national Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee.

The decision to exclude apixaban is also limited to a “subset of commercial drug lists,” she said, although specifics on which plans and the number of affected patients were not forthcoming.

The choice of DOAC is a timely question in cardiology, with recent studies suggesting an advantage for apixaban over rivaroxaban in reducing the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism, as well as reducing the risk of major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in atrial fibrillation.

Ms. Peaslee said CVS Caremark closely monitors medical literature for relevant clinical trial data and that most clients allow reasonable formulary exceptions when justified. “This formulary exceptions process has been successfully used for changes of this type and allows patients to get a medication that is safe and effective, as determined by their prescriber.”

The company will also continue to provide “robust, personalized outreach to the small number of members who will need to switch to an alternative medication,” she added.

Dr. Beavers said negotiations with CVS are still in the early stages, but, in the meantime, the ACC is providing health care providers with tools, such as drug copay cards and electronic prior authorizations, to help ensure patients don’t have gaps in coverage.

In a Jan. 14 news release addressing the formulary change, ACC notes that a patient’s pharmacy can also request a one-time override when trying to fill a nonpreferred DOAC in January to buy time if switching medications with their clinician or requesting a formulary exception.

During discussions with CVS Caremark, it says the ACC and the American Society of Hematology “underscored the negative impacts of this decision on patients currently taking one of the nonpreferred DOACs and on those who have previously tried rivaroxaban and changed medications.”

The groups also highlighted difficulties with other prior authorization programs in terms of the need for dedicated staff and time away from direct patient care.

“The ACC and ASH will continue discussions with CVS Caremark regarding the burden on clinicians and the effect of the formulary decision on patient access,” the release says.

In its letter to CVS, PACH argues that the apixaban exclusion will disproportionately affect historically disadvantaged patients, leaving those who can least afford the change with limited options. Notably, no generic is available for either apixaban or rivaroxaban.

The group also highlights a 2019 national poll, in which nearly 40% of patients who had their medication switched were so frustrated that they stopped their medication altogether.

PACH has an online petition against nonmedical switching, which at press time had garnered 2,126 signatures.

One signee, Jan Griffin, who survived bilateral pulmonary embolisms, writes that she has been on Eliquis [apixaban] successfully since her hospital discharge. “Now, as of midnight, Caremark apparently knows better than my hematologist as to what blood thinner is better for me and will no longer cover my Eliquis prescription. This is criminal, immoral, and unethical. #StopTheSwitch.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients looking to refill a prescription for apixaban (Eliquis) through CVS Caremark may be in for a surprise following its decision to exclude the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) from its formulary starting Jan. 1.

The move leaves just one DOAC, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), on CVS’ commercial formulary and is being assailed as the latest example of “nonmedical switching” used by health insurers to control costs.

In a letter to CVS Caremark backed by 14 provider and patient organizations, the nonprofit Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health (PACH) calls on the pharmacy chain to reverse its “dangerously disruptive” decision to force stable patients at high risk of cardiovascular events to switch anticoagulation, without an apparent option to be grandfathered into the new plan.

PACH president Dharmesh Patel, MD, Stern Cardiovascular Center, Memphis, called the formulary change “reckless and irresponsible, especially because the decision is not based in science and evidence, but on budgets. Patients and their health care providers, not insurance companies, need to be trusted to determine what medication is best,” he said in a statement.

Craig Beavers, PharmD, vice president of Baptist Health Paducah, Kentucky, said that, as chair of the American College of Cardiology’s Cardiovascular Team Section, he and other organizations have met with CVS Caremark medical leadership to advocate for patients and to understand the company’s perspective.

“The underlying driver is cost,” he told this news organization.

Current guidelines recommend DOACs in general for a variety of indications, including to reduce the risk of stroke and embolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and to prevent deep vein thrombosis, but there are select instances where a particular DOAC might be more appropriate, he observed.

“Apixaban may be better for a patient with a history of GI bleeding because there’s less GI bleeding, but the guidelines don’t necessarily spell those things out,” Dr. Beavers said. “That’s where the clinician should advocate for their patient and, unfortunately, they are making their decision strictly based off the guidelines.”

Requests to speak with medical officers at CVS Caremark went unanswered, but its executive director of communications, Christina Peaslee, told this news organization that the formulary decision “maintains clinically appropriate, cost-effective prescription coverage” for its clients and members.

“Both the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society and 2021 CHEST guidelines recommend DOACs over warfarin for treatment of various cardiology conditions such as atrial fibrillation, but neither list a specific agent as preferred – showing that consensus clinical guidelines do not favor one over the other,” she said in an email. “Further, Xarelto has more FDA-approved indications than Eliquis (e.g., Xarelto is approved for a reduction in risk of major CV events in patients with CAD or PAD) in addition to all the same FDA indications as Eliquis.”

Ms. Peaslee pointed out that all formulary changes are evaluated by an external medical expert specializing in the disease state, followed by review and approval by an independent national Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee.

The decision to exclude apixaban is also limited to a “subset of commercial drug lists,” she said, although specifics on which plans and the number of affected patients were not forthcoming.

The choice of DOAC is a timely question in cardiology, with recent studies suggesting an advantage for apixaban over rivaroxaban in reducing the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism, as well as reducing the risk of major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in atrial fibrillation.

Ms. Peaslee said CVS Caremark closely monitors medical literature for relevant clinical trial data and that most clients allow reasonable formulary exceptions when justified. “This formulary exceptions process has been successfully used for changes of this type and allows patients to get a medication that is safe and effective, as determined by their prescriber.”

The company will also continue to provide “robust, personalized outreach to the small number of members who will need to switch to an alternative medication,” she added.

Dr. Beavers said negotiations with CVS are still in the early stages, but, in the meantime, the ACC is providing health care providers with tools, such as drug copay cards and electronic prior authorizations, to help ensure patients don’t have gaps in coverage.

In a Jan. 14 news release addressing the formulary change, ACC notes that a patient’s pharmacy can also request a one-time override when trying to fill a nonpreferred DOAC in January to buy time if switching medications with their clinician or requesting a formulary exception.

During discussions with CVS Caremark, it says the ACC and the American Society of Hematology “underscored the negative impacts of this decision on patients currently taking one of the nonpreferred DOACs and on those who have previously tried rivaroxaban and changed medications.”

The groups also highlighted difficulties with other prior authorization programs in terms of the need for dedicated staff and time away from direct patient care.

“The ACC and ASH will continue discussions with CVS Caremark regarding the burden on clinicians and the effect of the formulary decision on patient access,” the release says.

In its letter to CVS, PACH argues that the apixaban exclusion will disproportionately affect historically disadvantaged patients, leaving those who can least afford the change with limited options. Notably, no generic is available for either apixaban or rivaroxaban.

The group also highlights a 2019 national poll, in which nearly 40% of patients who had their medication switched were so frustrated that they stopped their medication altogether.

PACH has an online petition against nonmedical switching, which at press time had garnered 2,126 signatures.

One signee, Jan Griffin, who survived bilateral pulmonary embolisms, writes that she has been on Eliquis [apixaban] successfully since her hospital discharge. “Now, as of midnight, Caremark apparently knows better than my hematologist as to what blood thinner is better for me and will no longer cover my Eliquis prescription. This is criminal, immoral, and unethical. #StopTheSwitch.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients looking to refill a prescription for apixaban (Eliquis) through CVS Caremark may be in for a surprise following its decision to exclude the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) from its formulary starting Jan. 1.

The move leaves just one DOAC, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), on CVS’ commercial formulary and is being assailed as the latest example of “nonmedical switching” used by health insurers to control costs.

In a letter to CVS Caremark backed by 14 provider and patient organizations, the nonprofit Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health (PACH) calls on the pharmacy chain to reverse its “dangerously disruptive” decision to force stable patients at high risk of cardiovascular events to switch anticoagulation, without an apparent option to be grandfathered into the new plan.

PACH president Dharmesh Patel, MD, Stern Cardiovascular Center, Memphis, called the formulary change “reckless and irresponsible, especially because the decision is not based in science and evidence, but on budgets. Patients and their health care providers, not insurance companies, need to be trusted to determine what medication is best,” he said in a statement.

Craig Beavers, PharmD, vice president of Baptist Health Paducah, Kentucky, said that, as chair of the American College of Cardiology’s Cardiovascular Team Section, he and other organizations have met with CVS Caremark medical leadership to advocate for patients and to understand the company’s perspective.

“The underlying driver is cost,” he told this news organization.

Current guidelines recommend DOACs in general for a variety of indications, including to reduce the risk of stroke and embolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and to prevent deep vein thrombosis, but there are select instances where a particular DOAC might be more appropriate, he observed.

“Apixaban may be better for a patient with a history of GI bleeding because there’s less GI bleeding, but the guidelines don’t necessarily spell those things out,” Dr. Beavers said. “That’s where the clinician should advocate for their patient and, unfortunately, they are making their decision strictly based off the guidelines.”

Requests to speak with medical officers at CVS Caremark went unanswered, but its executive director of communications, Christina Peaslee, told this news organization that the formulary decision “maintains clinically appropriate, cost-effective prescription coverage” for its clients and members.

“Both the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society and 2021 CHEST guidelines recommend DOACs over warfarin for treatment of various cardiology conditions such as atrial fibrillation, but neither list a specific agent as preferred – showing that consensus clinical guidelines do not favor one over the other,” she said in an email. “Further, Xarelto has more FDA-approved indications than Eliquis (e.g., Xarelto is approved for a reduction in risk of major CV events in patients with CAD or PAD) in addition to all the same FDA indications as Eliquis.”

Ms. Peaslee pointed out that all formulary changes are evaluated by an external medical expert specializing in the disease state, followed by review and approval by an independent national Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee.

The decision to exclude apixaban is also limited to a “subset of commercial drug lists,” she said, although specifics on which plans and the number of affected patients were not forthcoming.

The choice of DOAC is a timely question in cardiology, with recent studies suggesting an advantage for apixaban over rivaroxaban in reducing the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism, as well as reducing the risk of major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in atrial fibrillation.

Ms. Peaslee said CVS Caremark closely monitors medical literature for relevant clinical trial data and that most clients allow reasonable formulary exceptions when justified. “This formulary exceptions process has been successfully used for changes of this type and allows patients to get a medication that is safe and effective, as determined by their prescriber.”

The company will also continue to provide “robust, personalized outreach to the small number of members who will need to switch to an alternative medication,” she added.

Dr. Beavers said negotiations with CVS are still in the early stages, but, in the meantime, the ACC is providing health care providers with tools, such as drug copay cards and electronic prior authorizations, to help ensure patients don’t have gaps in coverage.

In a Jan. 14 news release addressing the formulary change, ACC notes that a patient’s pharmacy can also request a one-time override when trying to fill a nonpreferred DOAC in January to buy time if switching medications with their clinician or requesting a formulary exception.

During discussions with CVS Caremark, it says the ACC and the American Society of Hematology “underscored the negative impacts of this decision on patients currently taking one of the nonpreferred DOACs and on those who have previously tried rivaroxaban and changed medications.”

The groups also highlighted difficulties with other prior authorization programs in terms of the need for dedicated staff and time away from direct patient care.

“The ACC and ASH will continue discussions with CVS Caremark regarding the burden on clinicians and the effect of the formulary decision on patient access,” the release says.

In its letter to CVS, PACH argues that the apixaban exclusion will disproportionately affect historically disadvantaged patients, leaving those who can least afford the change with limited options. Notably, no generic is available for either apixaban or rivaroxaban.

The group also highlights a 2019 national poll, in which nearly 40% of patients who had their medication switched were so frustrated that they stopped their medication altogether.

PACH has an online petition against nonmedical switching, which at press time had garnered 2,126 signatures.

One signee, Jan Griffin, who survived bilateral pulmonary embolisms, writes that she has been on Eliquis [apixaban] successfully since her hospital discharge. “Now, as of midnight, Caremark apparently knows better than my hematologist as to what blood thinner is better for me and will no longer cover my Eliquis prescription. This is criminal, immoral, and unethical. #StopTheSwitch.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Woman with throbbing unilateral headache

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

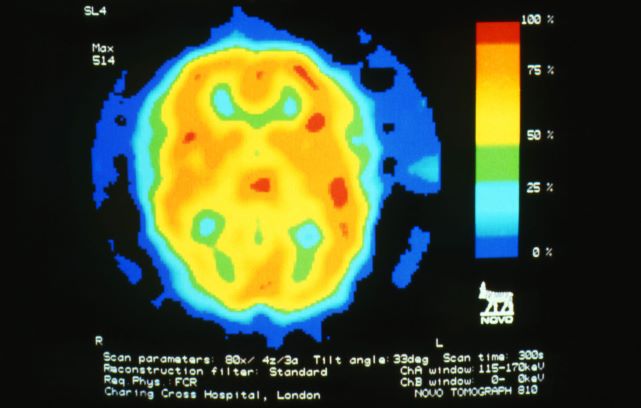

A 28-year-old woman presents with a throbbing unilateral headache (left side) and is very nauseated. She describes a white light in her line of vision. Her headaches are recurring, pulsating, and usually last for about 2 days without relief from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). She has been experiencing these episodes almost every month for the past 8 months and initially attributed them to her menstrual cycle, as she has always experienced moderate to severe headaches during this time. The patient is enrolled in a research trial in which single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging revealed low activity with reduced blood flow. The patient is nonfebrile.

Pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: 5 days of antibiotics better than 10 days

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Appendectomy or antibiotics? Large trial helps decision-making

The presence of mineralized stool, known as appendicolith, was associated with a nearly twofold increased risk of undergoing appendectomy within 30 days of initiating antibiotics, write David Flum, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors in a paper published in JAMA Surgery on Jan. 12, 2021.

But the surprise was the lack of an association between appendectomy and factors often presumed to be consistent with more severe appendicitis.

Physicians have had their own ideas about what factors make a patient more likely to need an appendectomy after an initial round of treatment with antibiotics, such as a high white blood cell count or a perforation seen on CT scan, Dr. Flum said in an interview. But the research didn’t support some of these theories.

“This is why we do the studies,” Dr. Flum said. “Sometimes we find out that our hunches were wrong.”

Dr. Flum and coauthors measured the association between different patient factors and disease severity and the need for appendectomy following a course of antibiotics. They used adjusted odds ratios to describe these relationships while accounting for other differences.

An OR of 1.0 – or when the confidence interval around an OR crosses 1 – signals that there is no association between that factor and appendectomy. Positive ORs with confidence intervals that exclude 1.0 suggest the factor was associated with appendectomy.

The OR was 1.99 for the presence of appendicolith, a finding with a 95% confidence interval of 1.28-3.10. The OR was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.01-2.31) for female sex.

But the OR was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.66-1.98) for perforation, abscess, or fat stranding.

The OR was 1.09 (95% CI, 1.00-1.18) for radiographic finding of a larger appendix, as measured by diameter.

And the OR was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.98-1.09) for having a higher white blood cell count, as measured by a 1,000-cells/mcL increase.

Appy or not?

This paper draws from the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy (CODA) trial (NCT02800785), for which top-line results were published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that paper, Dr. Flum and colleagues reported on results for 1,552 adults (414 with an appendicolith) who were evenly randomized to either antibiotics treatment or appendectomy. After 30 days, antibiotics were found to be noninferior to appendectomy, as reported by this news organization.

The federal Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute funded the CODA research. Dr. Flum said the National Institutes of Health had not appeared interested in funding a look at the different options available to patients experiencing appendicitis. Congress created PCORI as part of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, seeking to encourage researchers to study which treatments best serve patients through direct comparisons. Its support was critical for Dr. Flum and colleagues in seeking to help people weigh their options for treating appendicitis.

The CODA study “models what the patient’s experience is like, and this has not been the focus of NIH as much,” Dr. Flum said.

The CODA team has sought to make it easy for patients to consider what its findings and other research on appendicitis mean for them. They created an online decision-making tool, available at the aptly named http://www.appyornot.org/ website, which has videos in English and Spanish explaining patients’ options in simple terms. The website also asks questions about personal preferences, priorities, and resources to help them choose a treatment based on their individual situation.

Shift away from ‘paternalistic framing’

In the past, surgeons focused on the risk for patients from procedures, making the decisions for them about whether or not to proceed. There’s now a drive to shift away from this “paternalistic framing” toward shared decision-making, Dr. Flum said.

Surgeons need to have conversations with their patients about what’s happening in their lives as well as to assess their fears and concerns about treatment options, he said. These are aspects of patient care that were not covered in medical school or surgical training, but they lead to “less paternalistic” treatment. A patient’s decision about whether to choose surgery or antibiotics for appendicitis may hinge on factors such as insurance coverage, access to childcare, and the ability to miss days of work.

Dr. Flum said his fellow surgeons by and large have reacted well to the CODA team’s work.

“To their credit, the surgical community has embraced a healthy skepticism about the role of surgery,” Dr. Flum said.

The guidelines of the American College of Surgeons state that there is “high-quality evidence” that most patients with appendicitis can be managed with antibiotics instead of appendectomy (69% overall avoid appendectomy by 90 days, 75% of those without appendicolith, and 59% of those with appendicolith).

“Based on the surgeon’s judgment, patient preferences, and local resources (e.g., hospital staff, bed, and PPE supply availability) antibiotics are an acceptable first-line treatment, with appendectomy offered for those with worsening or recurrent symptoms,” the ACS guidelines say.

In an interview, Samir M. Fakhry, MD, vice president of HCA Center for Trauma and Acute Care Surgery Research in Nashville, Tenn., agreed with Dr. Flum about the shift taking place in medicine.

The CODA research, including the new paper in JAMA Surgery, makes it easier for physicians to work with patients and their families to reach decisions about how to treat appendicitis, Dr. Fakhry said.

These important discussions take time, he said, and patients must be allowed that time. Patients might feel misled, for example, if a surgeon pressed for appendectomy without explaining that a course of antibiotics may have served them well. Other patients may opt for surgery right away, especially in cases with appendicoliths, to avoid the potential for repeat episodes of medical care.

“You’ve got people who just want to get it done and over with. You’ve got people who want to avoid surgery no matter what,” Dr. Fakhry said. “It’s not just about the science and the data.”

This study was supported by a grant from PCORI. The authors reported having served as consultants or reviewers or have received fees for work outside of this paper from Stryker, Kerecis, Acera, Medline, Shriner’s Research Fund, UpToDate, and Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals Stryker.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The presence of mineralized stool, known as appendicolith, was associated with a nearly twofold increased risk of undergoing appendectomy within 30 days of initiating antibiotics, write David Flum, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors in a paper published in JAMA Surgery on Jan. 12, 2021.

But the surprise was the lack of an association between appendectomy and factors often presumed to be consistent with more severe appendicitis.

Physicians have had their own ideas about what factors make a patient more likely to need an appendectomy after an initial round of treatment with antibiotics, such as a high white blood cell count or a perforation seen on CT scan, Dr. Flum said in an interview. But the research didn’t support some of these theories.

“This is why we do the studies,” Dr. Flum said. “Sometimes we find out that our hunches were wrong.”