User login

Hair loss on scalp

The FP noted patchy alopecia with scaling of the scalp and made the presumptive diagnosis of tinea capitis. A woods lamp examination did not demonstrate fluorescence. The child was very cooperative and the doctor was able to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation by scraping the areas of alopecia with the edge of one glass slide while catching the scale on another slide. Microscopic examination revealed branching hyphae and some broken hairs with fungal elements within the hair shaft. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) This microscopic picture was consistent with Trichophyton tonsurans, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the United States. The reason that the infected area did not fluoresce was that the dermatophyte was within the hair shaft (endothrix) rather than external to the hair (exothrix).

Topical antifungal therapy is not adequate for tinea capitis; oral treatment is needed. Oral antifungal choices include griseofulvin, terbinafine, and fluconazole. Griseofulvin comes in an oral suspension making it a desirable option for children who can’t swallow pills. However, at least 6 to 8 weeks of treatment (20 mg/kg/d) is required. Oral terbinafine tablets are less expensive and shorter courses of therapy may be used. Tablets of 250 mg terbinafine (most affordable of all the choices) can be broken in half for younger children and the dose should always be calculated based on weight. Fluconazole comes in various tablets, strengths, and liquid formulations and can be prescribed for 3 to 6 weeks, as needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Yao C. Tinea capitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:782-787.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted patchy alopecia with scaling of the scalp and made the presumptive diagnosis of tinea capitis. A woods lamp examination did not demonstrate fluorescence. The child was very cooperative and the doctor was able to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation by scraping the areas of alopecia with the edge of one glass slide while catching the scale on another slide. Microscopic examination revealed branching hyphae and some broken hairs with fungal elements within the hair shaft. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) This microscopic picture was consistent with Trichophyton tonsurans, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the United States. The reason that the infected area did not fluoresce was that the dermatophyte was within the hair shaft (endothrix) rather than external to the hair (exothrix).

Topical antifungal therapy is not adequate for tinea capitis; oral treatment is needed. Oral antifungal choices include griseofulvin, terbinafine, and fluconazole. Griseofulvin comes in an oral suspension making it a desirable option for children who can’t swallow pills. However, at least 6 to 8 weeks of treatment (20 mg/kg/d) is required. Oral terbinafine tablets are less expensive and shorter courses of therapy may be used. Tablets of 250 mg terbinafine (most affordable of all the choices) can be broken in half for younger children and the dose should always be calculated based on weight. Fluconazole comes in various tablets, strengths, and liquid formulations and can be prescribed for 3 to 6 weeks, as needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Yao C. Tinea capitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:782-787.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted patchy alopecia with scaling of the scalp and made the presumptive diagnosis of tinea capitis. A woods lamp examination did not demonstrate fluorescence. The child was very cooperative and the doctor was able to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation by scraping the areas of alopecia with the edge of one glass slide while catching the scale on another slide. Microscopic examination revealed branching hyphae and some broken hairs with fungal elements within the hair shaft. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) This microscopic picture was consistent with Trichophyton tonsurans, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the United States. The reason that the infected area did not fluoresce was that the dermatophyte was within the hair shaft (endothrix) rather than external to the hair (exothrix).

Topical antifungal therapy is not adequate for tinea capitis; oral treatment is needed. Oral antifungal choices include griseofulvin, terbinafine, and fluconazole. Griseofulvin comes in an oral suspension making it a desirable option for children who can’t swallow pills. However, at least 6 to 8 weeks of treatment (20 mg/kg/d) is required. Oral terbinafine tablets are less expensive and shorter courses of therapy may be used. Tablets of 250 mg terbinafine (most affordable of all the choices) can be broken in half for younger children and the dose should always be calculated based on weight. Fluconazole comes in various tablets, strengths, and liquid formulations and can be prescribed for 3 to 6 weeks, as needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Yao C. Tinea capitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:782-787.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Heart failure risk with individual NSAIDs examined in study

Nine popular painkillers – including traditional NSAIDs and cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors – are associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure in adults, based on data from a case-control study of approximately 92,000 hospital admissions. The findings were published online Sept. 28 in BMJ.

Although data from previous large studies suggest that high doses of NSAIDs as well as COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, “there is still limited information on the risk of heart failure associated with the use of individual NSAIDs in clinical practice,” wrote Andrea Arfè of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i4857 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4857).

The researchers reviewed data from five electronic health databases in the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom as part of the SOS (Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) project and conducted a nested, case-control study including 92,163 hospital admissions for heart failure and 8,246,403 controls matched for age, sex, and year of study entry. The study included 23 traditional NSAIDs and four selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Overall, individual use of any of nine different NSAIDs within 14 days was associated with a nearly 20% higher likelihood of hospital admission for heart failure, compared with NSAID use more than 183 days in the past (odds ratio, 1.19). For seven traditional NSAIDS (diclofenac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nimesulide, and piroxicam) and the COX-2 inhibitors etoricoxib and rofecoxib, the odds ratios for heart failure with current use ranged from 1.16 for naproxen to 1.83 for ketorolac, compared with past use.

In addition, the odds of hospitalization for heart failure doubled for diclofenac, etoricoxib, indomethacin, piroxicam, and rofecoxib when dosed at two or more daily dose equivalents, the researchers noted. There was no increase in the odds of hospitalization for heart failure with celecoxib when dosed at standard levels, but “indomethacin and etoricoxib seemed to increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, even if used at medium doses,” they said. Other lesser-used NSAIDs were associated with an increased risk, but it was not statistically significant.

“The effect of individual NSAIDs could depend on a complex interaction of pharmacological properties, including duration and extent of platelet inhibition, extent of blood pressure increase, and properties possibly unique to the molecule,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including misclassification of outcomes and the observational nature of the study, which prevents conclusions about cause and effect, the researchers noted. However, “Because any potential increased risk could have a considerable impact on public health, the risk effect estimates provided by this study may help inform both clinical practice and regulatory activities,” they said.

The study was funded in part by the European Community’s seventh Framework Programme. Mr. Arfè had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Schwabe, and Novartis.

This report provides additional weight backing the association between increased risk of heart failure with NSAID use and gives better insight on the dose-response relationship between individual NSAIDs and heart failure. However, beyond that, its clinical impact is hurt by the lack of data on the magnitude of excess absolute risk of heart failure with NSAID use, which varies according to baseline cardiovascular risk.

Even though the risk of heart failure associated with NSAID use in the study occurred independent of a history of heart failure, it still is prudent to restrict NSAID use in patients with heart failure because of the high risk noted in this group in other studies.

The widespread use and ease of access to NSAIDs fuels the common misconception that NSAIDs are harmless drugs that are safe for everyone, and this warrants a more restrictive policy by regulatory authorities on the availability of NSAIDs and requirements for health care professionals providing advice on their use.

Gunnar H. Gislason, MD, PhD, is a professor of cardiology at Copenhagen University Hospital Herlev and Gentofte, Denmark, and Christian Torp-Pedersen, MD, is a professor of cardiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University. Dr. Gislason had no disclosures and Dr. Torp-Pedersen advises Bayer on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Their remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying the study by Mr. Arfè and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i5163 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5163).

This report provides additional weight backing the association between increased risk of heart failure with NSAID use and gives better insight on the dose-response relationship between individual NSAIDs and heart failure. However, beyond that, its clinical impact is hurt by the lack of data on the magnitude of excess absolute risk of heart failure with NSAID use, which varies according to baseline cardiovascular risk.

Even though the risk of heart failure associated with NSAID use in the study occurred independent of a history of heart failure, it still is prudent to restrict NSAID use in patients with heart failure because of the high risk noted in this group in other studies.

The widespread use and ease of access to NSAIDs fuels the common misconception that NSAIDs are harmless drugs that are safe for everyone, and this warrants a more restrictive policy by regulatory authorities on the availability of NSAIDs and requirements for health care professionals providing advice on their use.

Gunnar H. Gislason, MD, PhD, is a professor of cardiology at Copenhagen University Hospital Herlev and Gentofte, Denmark, and Christian Torp-Pedersen, MD, is a professor of cardiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University. Dr. Gislason had no disclosures and Dr. Torp-Pedersen advises Bayer on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Their remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying the study by Mr. Arfè and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i5163 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5163).

This report provides additional weight backing the association between increased risk of heart failure with NSAID use and gives better insight on the dose-response relationship between individual NSAIDs and heart failure. However, beyond that, its clinical impact is hurt by the lack of data on the magnitude of excess absolute risk of heart failure with NSAID use, which varies according to baseline cardiovascular risk.

Even though the risk of heart failure associated with NSAID use in the study occurred independent of a history of heart failure, it still is prudent to restrict NSAID use in patients with heart failure because of the high risk noted in this group in other studies.

The widespread use and ease of access to NSAIDs fuels the common misconception that NSAIDs are harmless drugs that are safe for everyone, and this warrants a more restrictive policy by regulatory authorities on the availability of NSAIDs and requirements for health care professionals providing advice on their use.

Gunnar H. Gislason, MD, PhD, is a professor of cardiology at Copenhagen University Hospital Herlev and Gentofte, Denmark, and Christian Torp-Pedersen, MD, is a professor of cardiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University. Dr. Gislason had no disclosures and Dr. Torp-Pedersen advises Bayer on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Their remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying the study by Mr. Arfè and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i5163 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5163).

Nine popular painkillers – including traditional NSAIDs and cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors – are associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure in adults, based on data from a case-control study of approximately 92,000 hospital admissions. The findings were published online Sept. 28 in BMJ.

Although data from previous large studies suggest that high doses of NSAIDs as well as COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, “there is still limited information on the risk of heart failure associated with the use of individual NSAIDs in clinical practice,” wrote Andrea Arfè of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i4857 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4857).

The researchers reviewed data from five electronic health databases in the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom as part of the SOS (Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) project and conducted a nested, case-control study including 92,163 hospital admissions for heart failure and 8,246,403 controls matched for age, sex, and year of study entry. The study included 23 traditional NSAIDs and four selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Overall, individual use of any of nine different NSAIDs within 14 days was associated with a nearly 20% higher likelihood of hospital admission for heart failure, compared with NSAID use more than 183 days in the past (odds ratio, 1.19). For seven traditional NSAIDS (diclofenac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nimesulide, and piroxicam) and the COX-2 inhibitors etoricoxib and rofecoxib, the odds ratios for heart failure with current use ranged from 1.16 for naproxen to 1.83 for ketorolac, compared with past use.

In addition, the odds of hospitalization for heart failure doubled for diclofenac, etoricoxib, indomethacin, piroxicam, and rofecoxib when dosed at two or more daily dose equivalents, the researchers noted. There was no increase in the odds of hospitalization for heart failure with celecoxib when dosed at standard levels, but “indomethacin and etoricoxib seemed to increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, even if used at medium doses,” they said. Other lesser-used NSAIDs were associated with an increased risk, but it was not statistically significant.

“The effect of individual NSAIDs could depend on a complex interaction of pharmacological properties, including duration and extent of platelet inhibition, extent of blood pressure increase, and properties possibly unique to the molecule,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including misclassification of outcomes and the observational nature of the study, which prevents conclusions about cause and effect, the researchers noted. However, “Because any potential increased risk could have a considerable impact on public health, the risk effect estimates provided by this study may help inform both clinical practice and regulatory activities,” they said.

The study was funded in part by the European Community’s seventh Framework Programme. Mr. Arfè had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Schwabe, and Novartis.

Nine popular painkillers – including traditional NSAIDs and cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors – are associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure in adults, based on data from a case-control study of approximately 92,000 hospital admissions. The findings were published online Sept. 28 in BMJ.

Although data from previous large studies suggest that high doses of NSAIDs as well as COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, “there is still limited information on the risk of heart failure associated with the use of individual NSAIDs in clinical practice,” wrote Andrea Arfè of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, and his colleagues (BMJ. 2016 Sep;354:i4857 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4857).

The researchers reviewed data from five electronic health databases in the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom as part of the SOS (Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) project and conducted a nested, case-control study including 92,163 hospital admissions for heart failure and 8,246,403 controls matched for age, sex, and year of study entry. The study included 23 traditional NSAIDs and four selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Overall, individual use of any of nine different NSAIDs within 14 days was associated with a nearly 20% higher likelihood of hospital admission for heart failure, compared with NSAID use more than 183 days in the past (odds ratio, 1.19). For seven traditional NSAIDS (diclofenac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nimesulide, and piroxicam) and the COX-2 inhibitors etoricoxib and rofecoxib, the odds ratios for heart failure with current use ranged from 1.16 for naproxen to 1.83 for ketorolac, compared with past use.

In addition, the odds of hospitalization for heart failure doubled for diclofenac, etoricoxib, indomethacin, piroxicam, and rofecoxib when dosed at two or more daily dose equivalents, the researchers noted. There was no increase in the odds of hospitalization for heart failure with celecoxib when dosed at standard levels, but “indomethacin and etoricoxib seemed to increase the risk of hospital admission for heart failure, even if used at medium doses,” they said. Other lesser-used NSAIDs were associated with an increased risk, but it was not statistically significant.

“The effect of individual NSAIDs could depend on a complex interaction of pharmacological properties, including duration and extent of platelet inhibition, extent of blood pressure increase, and properties possibly unique to the molecule,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including misclassification of outcomes and the observational nature of the study, which prevents conclusions about cause and effect, the researchers noted. However, “Because any potential increased risk could have a considerable impact on public health, the risk effect estimates provided by this study may help inform both clinical practice and regulatory activities,” they said.

The study was funded in part by the European Community’s seventh Framework Programme. Mr. Arfè had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Schwabe, and Novartis.

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Patients taking high doses of certain NSAIDS had significantly higher odds of hospital admission for heart failure, compared with controls not currently taking the medications.

Major finding: The odds of hospitalization for heart failure increased by 19% overall for adults currently using certain NSAIDS and doubled for users of certain NSAIDs at high doses.

Data source: The data come from approximately 10 million hospital admissions taken from databases in the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the European Community’s seventh Framework Programme. Mr. Arfè had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Schwabe, and Novartis.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Eases Postconcussive Symptoms in Teens

Adolescents who underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as part of postconcussion care reported significantly lower levels of postconcussive and depressive symptoms, according to the results of a randomized trial published online ahead of print September 12 in Pediatrics.

“Affective symptoms, including depression and anxiety, commonly co-occur with cognitive and somatic symptoms and may prolong recovery from postconcussive symptoms, wrote Carolyn A. McCarty, PhD, Research Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Adjunct Research Associate Professor of Psychology at Seattle Children’s Hospital Center for Child Health Behavior and Development in Seattle, and her colleagues.

“The complexities of managing persistent postconcussive symptoms in conjunction with comorbid psychological symptoms create a significant burden for injured children and adolescents, their families, and schools.”

To determine the impact of CBT on persistent symptoms in adolescents with concussions, the researchers randomized 49 patients, ages 11 to 17, to usual care or a collaborative care plan that included usual care plus CBT.

Concussions were diagnosed by sports medicine or rehabilitative medicine specialists. The patients assigned to CBT received usual care management, CBT, and possible psychopharmacologic consultation. Control patients received usual concussion care, generally defined as an initial visit with a sports medicine physician and assessments at one, three, and six months. Usual care also could include MRI, sleep medication, and subthreshold exercise, depending on the patient. No serious adverse events were reported. The average age of the patients was 15, approximately 65% were girls, and 76% were white.

After six months, approximately 13% of the teens in the CBT group reported high levels of postconcussive symptoms, compared with 42% of controls. In addition, 78% of patients receiving CBT reported a depressive symptom reduction of more than 50%, compared with 46% of controls.

Overall, 83% of the patients receiving CBT and 87% of their parents were “very satisfied” with their care, compared with 46% of patients and 29% of parents in the control group.

“Although patients in both groups showed symptom reduction in the first three months, only those who received collaborative care demonstrated sustained improvements through six months of follow-up,” Dr. McCarty and her colleagues wrote.

The results were limited by several factors, including the small size of the study, the researchers said. However, the findings “prompt more investigation into the role of affective symptoms in perpetuating physical symptoms secondary to prolonged recovery from sports-related concussion” and also suggest that collaborative care can help improve persistent postconcussive symptoms in teens.The Seattle Sports Concussion Research Collaborative supported the study.

—Heidi Splete

Suggested Reading

McCarty CA, Zatzick D, Stein E, et al. Collaborative care for adolescents with persistent postconcussive symptoms: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2016 Sept 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Cordingley D, Girardin R, Reimer K, et al. Graded aerobic treadmill testing in pediatric sports-related concussion: safety, clinical use, and patient outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016 September 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Adolescents who underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as part of postconcussion care reported significantly lower levels of postconcussive and depressive symptoms, according to the results of a randomized trial published online ahead of print September 12 in Pediatrics.

“Affective symptoms, including depression and anxiety, commonly co-occur with cognitive and somatic symptoms and may prolong recovery from postconcussive symptoms, wrote Carolyn A. McCarty, PhD, Research Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Adjunct Research Associate Professor of Psychology at Seattle Children’s Hospital Center for Child Health Behavior and Development in Seattle, and her colleagues.

“The complexities of managing persistent postconcussive symptoms in conjunction with comorbid psychological symptoms create a significant burden for injured children and adolescents, their families, and schools.”

To determine the impact of CBT on persistent symptoms in adolescents with concussions, the researchers randomized 49 patients, ages 11 to 17, to usual care or a collaborative care plan that included usual care plus CBT.

Concussions were diagnosed by sports medicine or rehabilitative medicine specialists. The patients assigned to CBT received usual care management, CBT, and possible psychopharmacologic consultation. Control patients received usual concussion care, generally defined as an initial visit with a sports medicine physician and assessments at one, three, and six months. Usual care also could include MRI, sleep medication, and subthreshold exercise, depending on the patient. No serious adverse events were reported. The average age of the patients was 15, approximately 65% were girls, and 76% were white.

After six months, approximately 13% of the teens in the CBT group reported high levels of postconcussive symptoms, compared with 42% of controls. In addition, 78% of patients receiving CBT reported a depressive symptom reduction of more than 50%, compared with 46% of controls.

Overall, 83% of the patients receiving CBT and 87% of their parents were “very satisfied” with their care, compared with 46% of patients and 29% of parents in the control group.

“Although patients in both groups showed symptom reduction in the first three months, only those who received collaborative care demonstrated sustained improvements through six months of follow-up,” Dr. McCarty and her colleagues wrote.

The results were limited by several factors, including the small size of the study, the researchers said. However, the findings “prompt more investigation into the role of affective symptoms in perpetuating physical symptoms secondary to prolonged recovery from sports-related concussion” and also suggest that collaborative care can help improve persistent postconcussive symptoms in teens.The Seattle Sports Concussion Research Collaborative supported the study.

—Heidi Splete

Suggested Reading

McCarty CA, Zatzick D, Stein E, et al. Collaborative care for adolescents with persistent postconcussive symptoms: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2016 Sept 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Cordingley D, Girardin R, Reimer K, et al. Graded aerobic treadmill testing in pediatric sports-related concussion: safety, clinical use, and patient outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016 September 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Adolescents who underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as part of postconcussion care reported significantly lower levels of postconcussive and depressive symptoms, according to the results of a randomized trial published online ahead of print September 12 in Pediatrics.

“Affective symptoms, including depression and anxiety, commonly co-occur with cognitive and somatic symptoms and may prolong recovery from postconcussive symptoms, wrote Carolyn A. McCarty, PhD, Research Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Adjunct Research Associate Professor of Psychology at Seattle Children’s Hospital Center for Child Health Behavior and Development in Seattle, and her colleagues.

“The complexities of managing persistent postconcussive symptoms in conjunction with comorbid psychological symptoms create a significant burden for injured children and adolescents, their families, and schools.”

To determine the impact of CBT on persistent symptoms in adolescents with concussions, the researchers randomized 49 patients, ages 11 to 17, to usual care or a collaborative care plan that included usual care plus CBT.

Concussions were diagnosed by sports medicine or rehabilitative medicine specialists. The patients assigned to CBT received usual care management, CBT, and possible psychopharmacologic consultation. Control patients received usual concussion care, generally defined as an initial visit with a sports medicine physician and assessments at one, three, and six months. Usual care also could include MRI, sleep medication, and subthreshold exercise, depending on the patient. No serious adverse events were reported. The average age of the patients was 15, approximately 65% were girls, and 76% were white.

After six months, approximately 13% of the teens in the CBT group reported high levels of postconcussive symptoms, compared with 42% of controls. In addition, 78% of patients receiving CBT reported a depressive symptom reduction of more than 50%, compared with 46% of controls.

Overall, 83% of the patients receiving CBT and 87% of their parents were “very satisfied” with their care, compared with 46% of patients and 29% of parents in the control group.

“Although patients in both groups showed symptom reduction in the first three months, only those who received collaborative care demonstrated sustained improvements through six months of follow-up,” Dr. McCarty and her colleagues wrote.

The results were limited by several factors, including the small size of the study, the researchers said. However, the findings “prompt more investigation into the role of affective symptoms in perpetuating physical symptoms secondary to prolonged recovery from sports-related concussion” and also suggest that collaborative care can help improve persistent postconcussive symptoms in teens.The Seattle Sports Concussion Research Collaborative supported the study.

—Heidi Splete

Suggested Reading

McCarty CA, Zatzick D, Stein E, et al. Collaborative care for adolescents with persistent postconcussive symptoms: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2016 Sept 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Cordingley D, Girardin R, Reimer K, et al. Graded aerobic treadmill testing in pediatric sports-related concussion: safety, clinical use, and patient outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016 September 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Adjunctive azithromycin cuts postcesarean infection

Adding a single intravenous dose of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis further reduces maternal infections without increasing neonatal adverse outcomes after nonelective cesarean delivery, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The adjunctive azithromycin also significantly decreased rates of postpartum fever and of readmission or unscheduled office visits, wrote Alan T.N. Tita, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues.

Recent studies have suggested that extended-spectrum prophylaxis using azithromycin, when added to standard cephalosporin prophylaxis, would further reduce the incidence of post-cesarean infection, chiefly because of azithromycin’s coverage of ureaplasma species that are frequently associated with these infections. The C/SOAP (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis) trial tested this hypothesis in 2,013 women who underwent nonelective cesarean delivery of singleton neonates at 14 U.S. hospitals during a 3.5-year period.

All the women received standard antibiotic prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) and were randomly assigned to receive either a 500-mg dose of azithromycin (1,019 participants) or a matching placebo (994 participants) before surgical incision.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of endometritis; wound infection; or other infections such as abdominopelvic abscess, maternal sepsis, pelvic septic thrombophlebitis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, or meningitis occurring up to 6 weeks after surgery – developed in half as many women in the azithromycin group (6.1%) as in the placebo group (12.0%). The relative risk (RR) was 0.51 (P less than .001).

Azithromycin, in particular, was associated with significantly lower rates of endometritis (3.8% vs. 6.1%; RR, 0.62; P = .02) and wound infection (2.4% vs. 6.6%; RR, 0.35; P less than .001). This benefit extended across all subgroups of patients regardless of study site, maternal obesity status, the presence or absence of membrane rupture at randomization, preterm or term delivery, or maternal diabetes status.

The number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one study outcome was 17 for the primary outcome, 43 for endometritis, and 24 for wound infections, the researchers reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375:1231-41).

Serious maternal adverse events also were less common with azithromycin (1.5%) than with placebo (2.9%). Neonatal outcomes did not differ between the study groups. The rate of combined neonatal death or complications was 14.3% with azithromycin and 13.6% with placebo, a nonsignificant difference.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pfizer donated the azithromycin used in the trial. Dr. Tita reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his colleagues reported ties to numerous industry sources.

This well-designed, pragmatic, multicenter trial shows that a single adjunctive dose of azithromycin likely would reduce the number of infectious complications for women undergoing nonelective cesarean section.

The addition of azithromycin may have been particularly effective for the 73% of this study population who had a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more. Obesity is known to double the risk of infectious complications, and previous studies have suggested that cefazolin may be underdosed in women with increased BMI values. It appears that azithromycin improved outcomes on the basis of the additive effects of the two drugs against common surgical pathogens, such as staphylococcus species. Information provided in the Supplementary Appendix accompanying the article indicates that routine bacterial cultures, when done, were much-less-frequently positive in the azithromycin group.

Robert A. Weinstein, MD, and Kenneth M. Boyer, MD, are at Rush University Medical Center and Cook County Health and Hospital System, both in Chicago. Dr. Weinstein reported receiving support from Merck outside of this work, and Dr. Boyer reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1610010).

This well-designed, pragmatic, multicenter trial shows that a single adjunctive dose of azithromycin likely would reduce the number of infectious complications for women undergoing nonelective cesarean section.

The addition of azithromycin may have been particularly effective for the 73% of this study population who had a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more. Obesity is known to double the risk of infectious complications, and previous studies have suggested that cefazolin may be underdosed in women with increased BMI values. It appears that azithromycin improved outcomes on the basis of the additive effects of the two drugs against common surgical pathogens, such as staphylococcus species. Information provided in the Supplementary Appendix accompanying the article indicates that routine bacterial cultures, when done, were much-less-frequently positive in the azithromycin group.

Robert A. Weinstein, MD, and Kenneth M. Boyer, MD, are at Rush University Medical Center and Cook County Health and Hospital System, both in Chicago. Dr. Weinstein reported receiving support from Merck outside of this work, and Dr. Boyer reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1610010).

This well-designed, pragmatic, multicenter trial shows that a single adjunctive dose of azithromycin likely would reduce the number of infectious complications for women undergoing nonelective cesarean section.

The addition of azithromycin may have been particularly effective for the 73% of this study population who had a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more. Obesity is known to double the risk of infectious complications, and previous studies have suggested that cefazolin may be underdosed in women with increased BMI values. It appears that azithromycin improved outcomes on the basis of the additive effects of the two drugs against common surgical pathogens, such as staphylococcus species. Information provided in the Supplementary Appendix accompanying the article indicates that routine bacterial cultures, when done, were much-less-frequently positive in the azithromycin group.

Robert A. Weinstein, MD, and Kenneth M. Boyer, MD, are at Rush University Medical Center and Cook County Health and Hospital System, both in Chicago. Dr. Weinstein reported receiving support from Merck outside of this work, and Dr. Boyer reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1610010).

Adding a single intravenous dose of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis further reduces maternal infections without increasing neonatal adverse outcomes after nonelective cesarean delivery, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The adjunctive azithromycin also significantly decreased rates of postpartum fever and of readmission or unscheduled office visits, wrote Alan T.N. Tita, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues.

Recent studies have suggested that extended-spectrum prophylaxis using azithromycin, when added to standard cephalosporin prophylaxis, would further reduce the incidence of post-cesarean infection, chiefly because of azithromycin’s coverage of ureaplasma species that are frequently associated with these infections. The C/SOAP (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis) trial tested this hypothesis in 2,013 women who underwent nonelective cesarean delivery of singleton neonates at 14 U.S. hospitals during a 3.5-year period.

All the women received standard antibiotic prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) and were randomly assigned to receive either a 500-mg dose of azithromycin (1,019 participants) or a matching placebo (994 participants) before surgical incision.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of endometritis; wound infection; or other infections such as abdominopelvic abscess, maternal sepsis, pelvic septic thrombophlebitis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, or meningitis occurring up to 6 weeks after surgery – developed in half as many women in the azithromycin group (6.1%) as in the placebo group (12.0%). The relative risk (RR) was 0.51 (P less than .001).

Azithromycin, in particular, was associated with significantly lower rates of endometritis (3.8% vs. 6.1%; RR, 0.62; P = .02) and wound infection (2.4% vs. 6.6%; RR, 0.35; P less than .001). This benefit extended across all subgroups of patients regardless of study site, maternal obesity status, the presence or absence of membrane rupture at randomization, preterm or term delivery, or maternal diabetes status.

The number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one study outcome was 17 for the primary outcome, 43 for endometritis, and 24 for wound infections, the researchers reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375:1231-41).

Serious maternal adverse events also were less common with azithromycin (1.5%) than with placebo (2.9%). Neonatal outcomes did not differ between the study groups. The rate of combined neonatal death or complications was 14.3% with azithromycin and 13.6% with placebo, a nonsignificant difference.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pfizer donated the azithromycin used in the trial. Dr. Tita reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his colleagues reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adding a single intravenous dose of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis further reduces maternal infections without increasing neonatal adverse outcomes after nonelective cesarean delivery, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The adjunctive azithromycin also significantly decreased rates of postpartum fever and of readmission or unscheduled office visits, wrote Alan T.N. Tita, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues.

Recent studies have suggested that extended-spectrum prophylaxis using azithromycin, when added to standard cephalosporin prophylaxis, would further reduce the incidence of post-cesarean infection, chiefly because of azithromycin’s coverage of ureaplasma species that are frequently associated with these infections. The C/SOAP (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis) trial tested this hypothesis in 2,013 women who underwent nonelective cesarean delivery of singleton neonates at 14 U.S. hospitals during a 3.5-year period.

All the women received standard antibiotic prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) and were randomly assigned to receive either a 500-mg dose of azithromycin (1,019 participants) or a matching placebo (994 participants) before surgical incision.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of endometritis; wound infection; or other infections such as abdominopelvic abscess, maternal sepsis, pelvic septic thrombophlebitis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, or meningitis occurring up to 6 weeks after surgery – developed in half as many women in the azithromycin group (6.1%) as in the placebo group (12.0%). The relative risk (RR) was 0.51 (P less than .001).

Azithromycin, in particular, was associated with significantly lower rates of endometritis (3.8% vs. 6.1%; RR, 0.62; P = .02) and wound infection (2.4% vs. 6.6%; RR, 0.35; P less than .001). This benefit extended across all subgroups of patients regardless of study site, maternal obesity status, the presence or absence of membrane rupture at randomization, preterm or term delivery, or maternal diabetes status.

The number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one study outcome was 17 for the primary outcome, 43 for endometritis, and 24 for wound infections, the researchers reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375:1231-41).

Serious maternal adverse events also were less common with azithromycin (1.5%) than with placebo (2.9%). Neonatal outcomes did not differ between the study groups. The rate of combined neonatal death or complications was 14.3% with azithromycin and 13.6% with placebo, a nonsignificant difference.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pfizer donated the azithromycin used in the trial. Dr. Tita reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his colleagues reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Strategies for maintaining resilience to the burnout threat

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

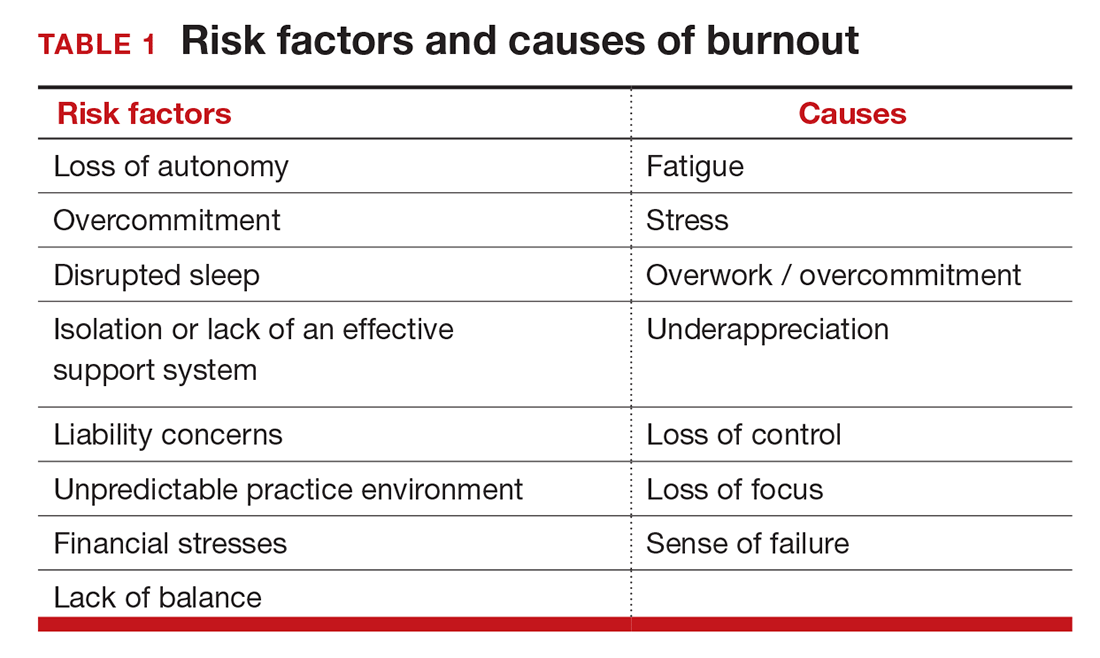

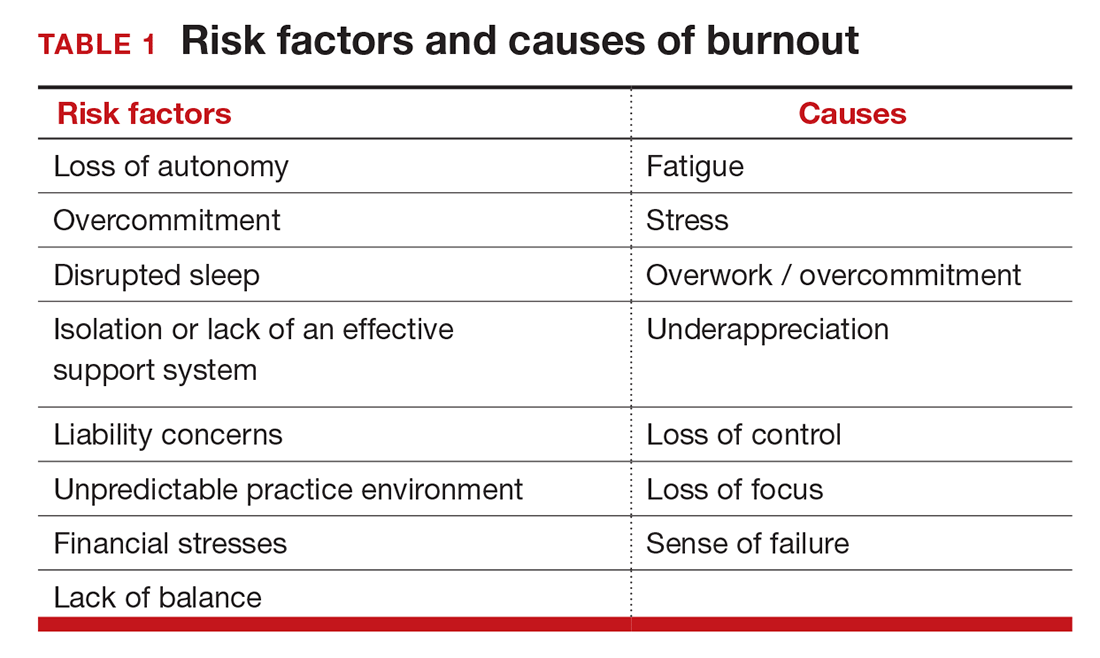

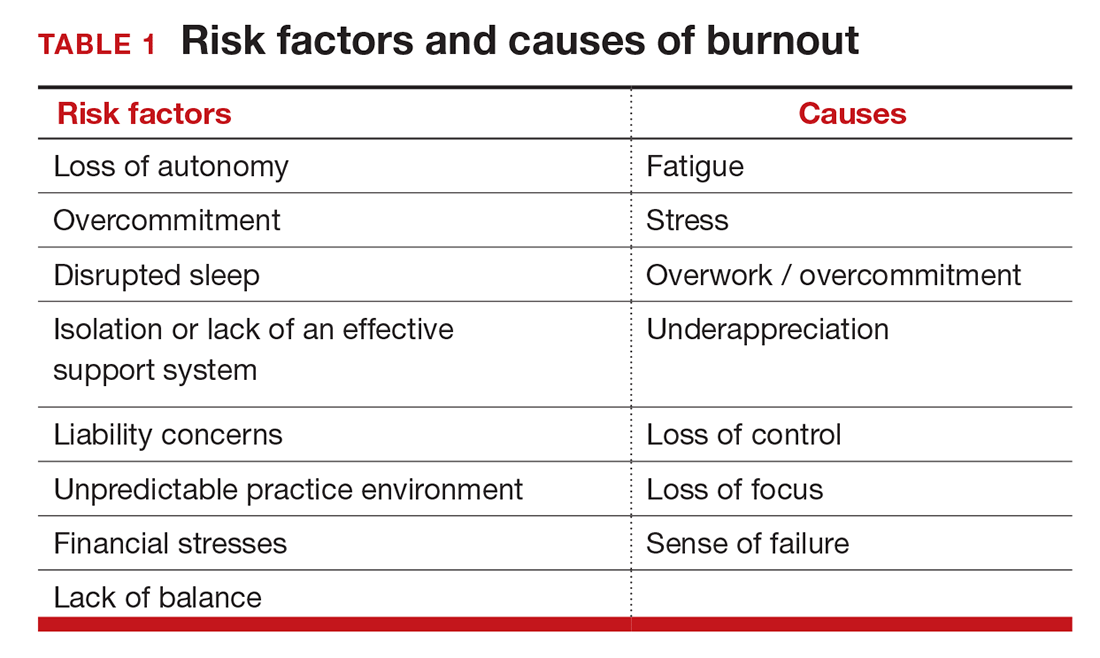

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

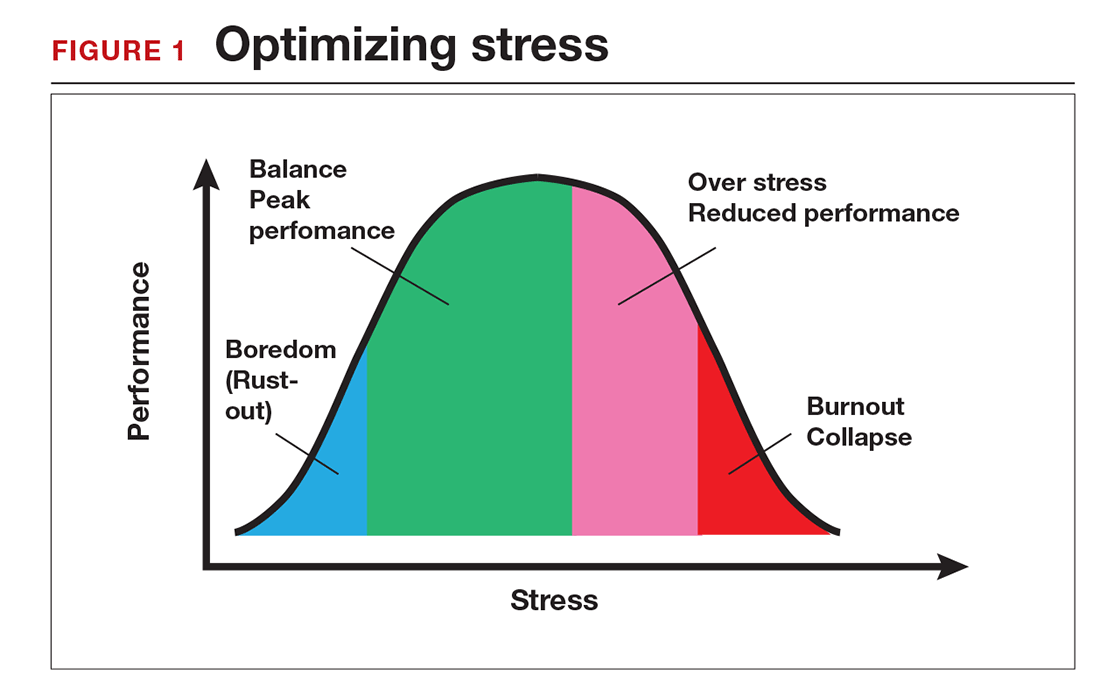

Does stress cause burnout?

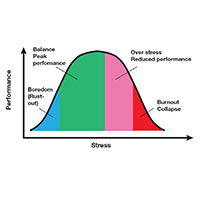

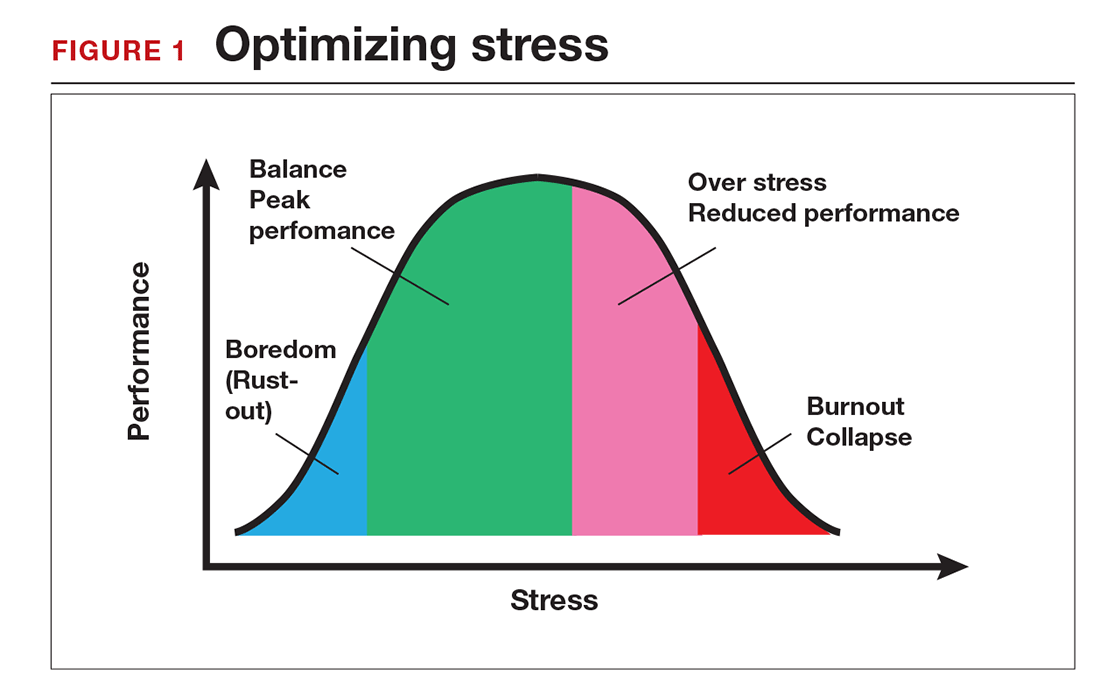

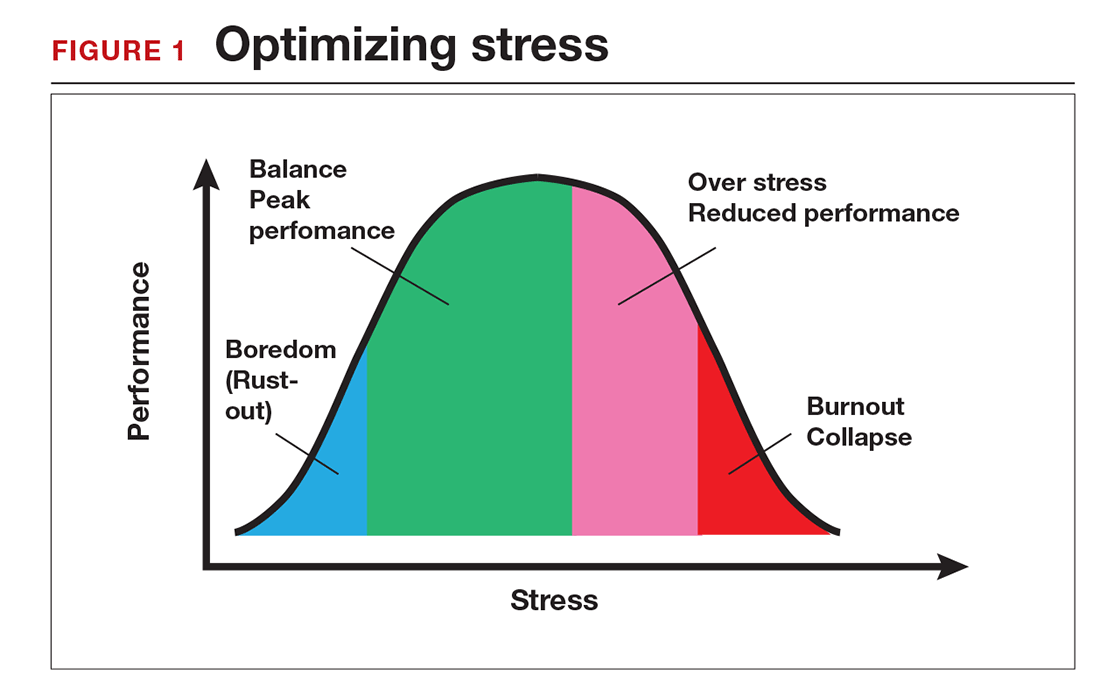

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

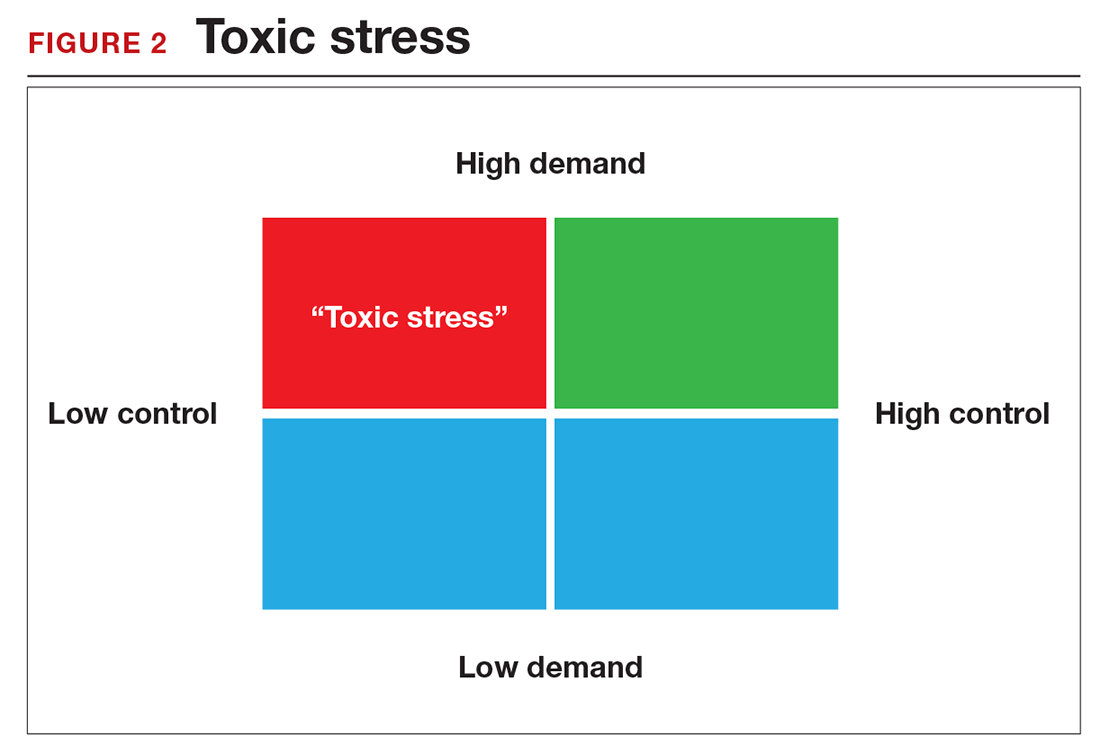

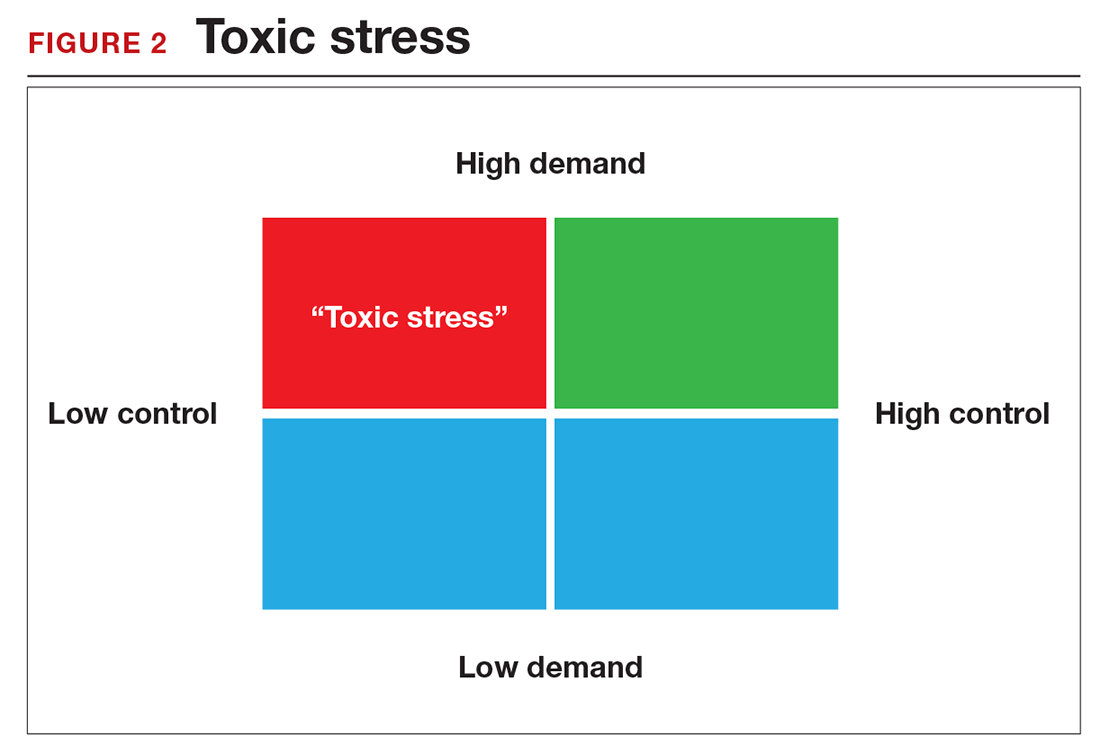

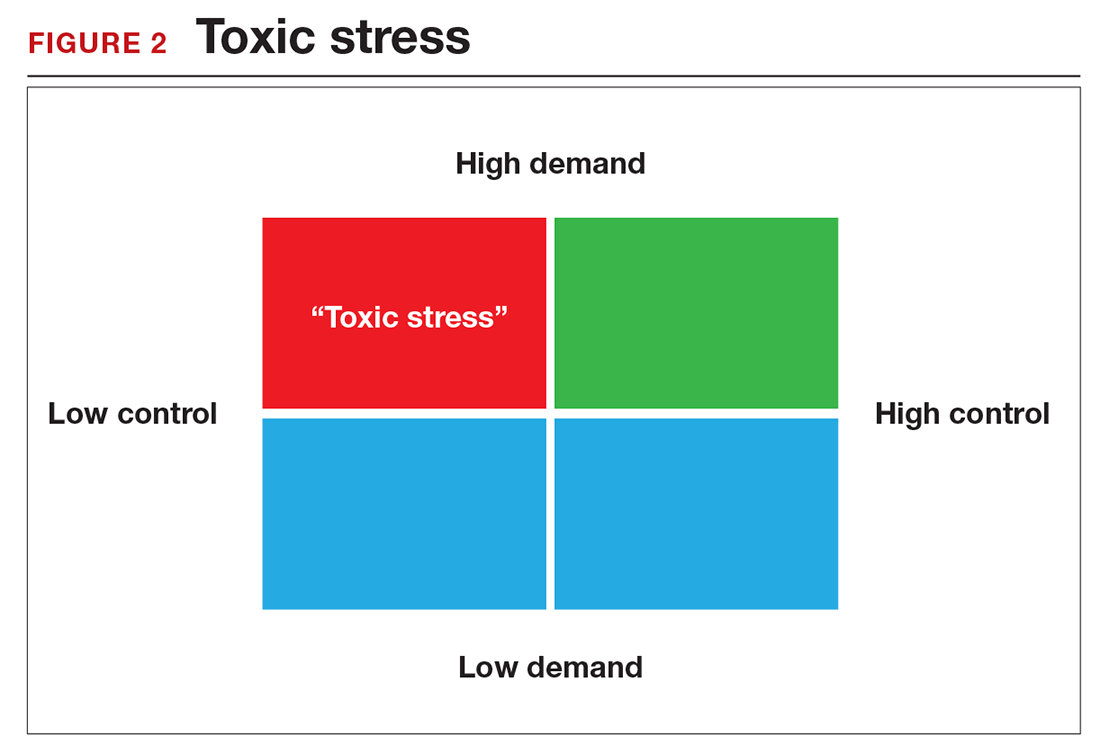

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

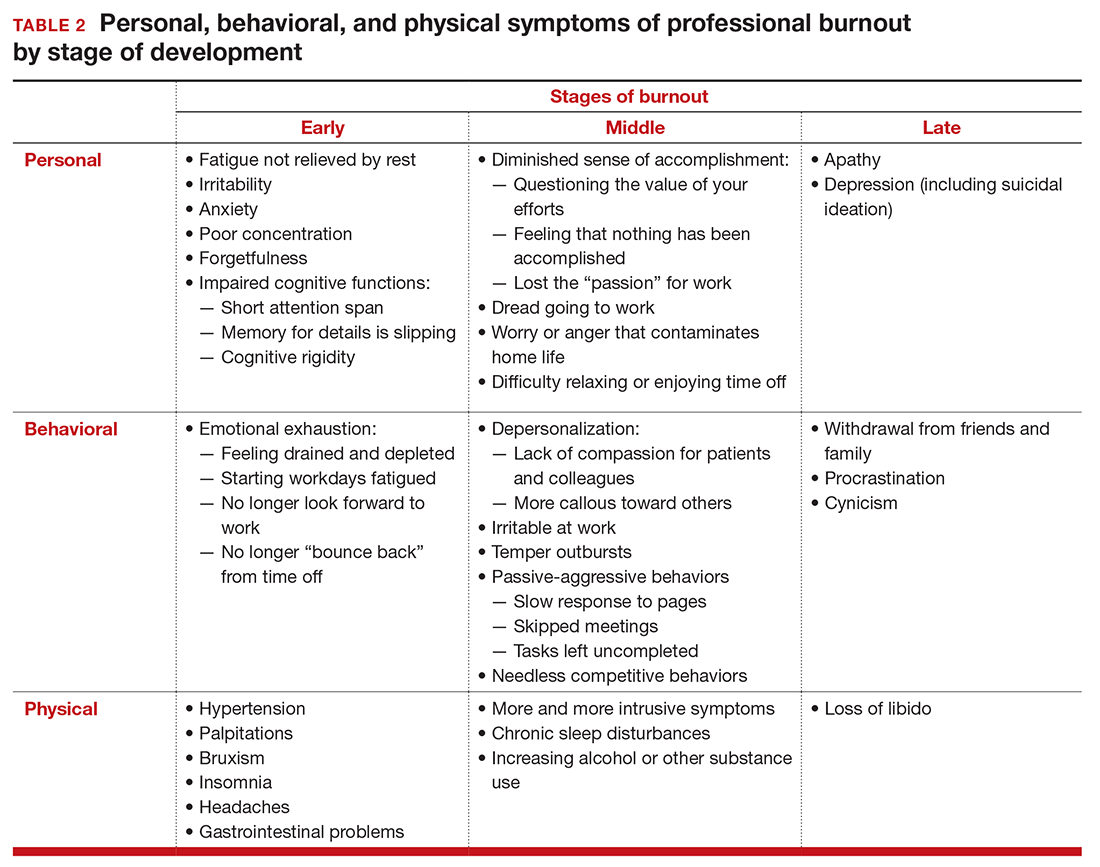

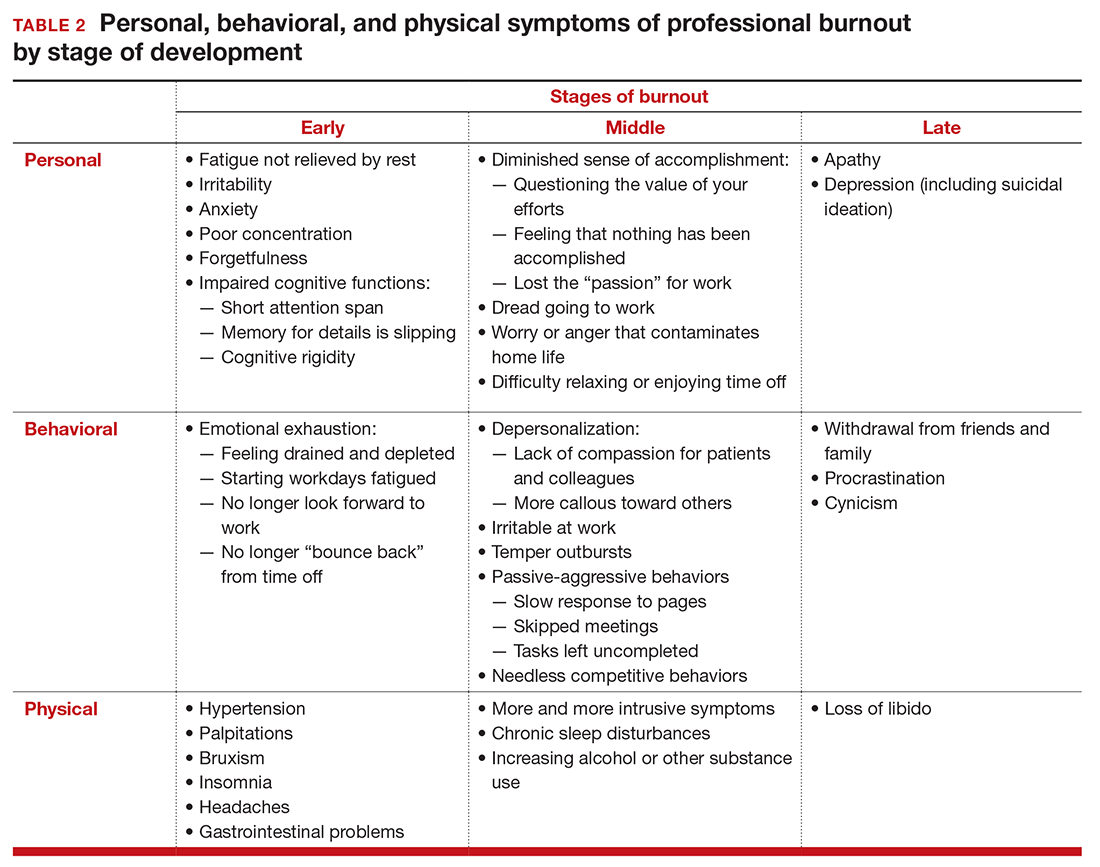

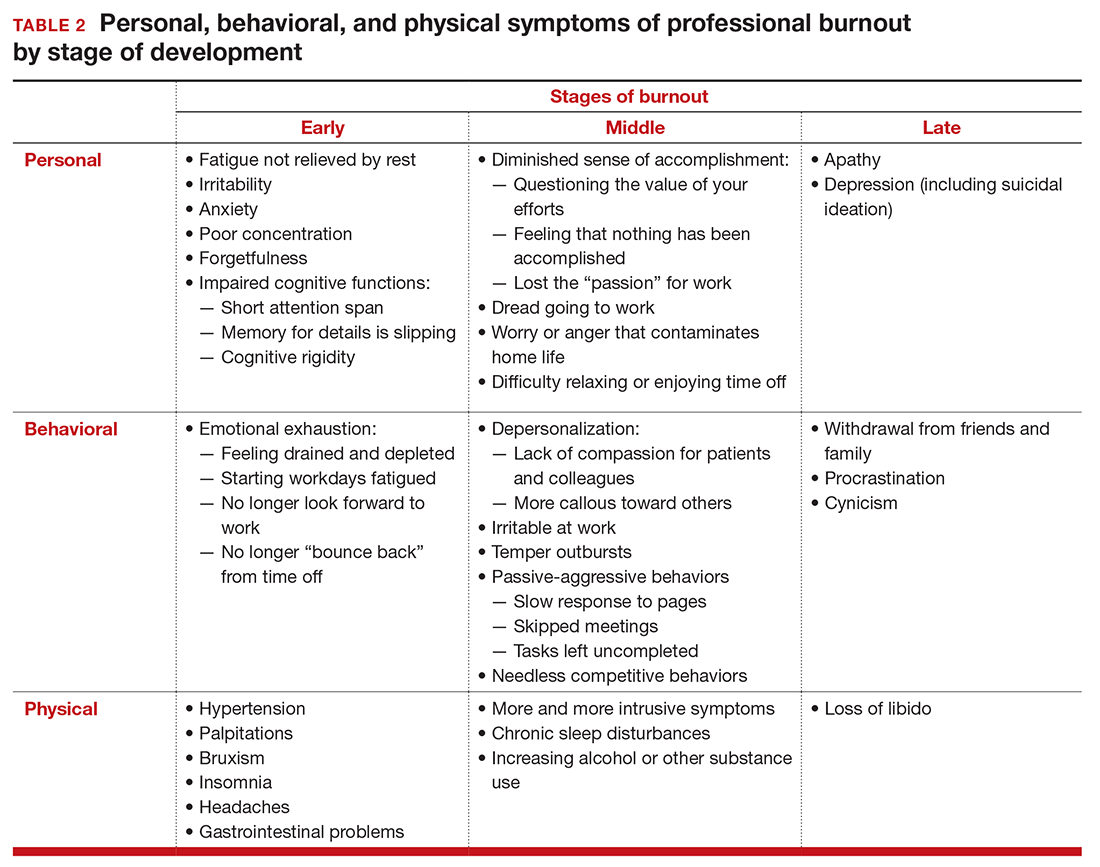

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

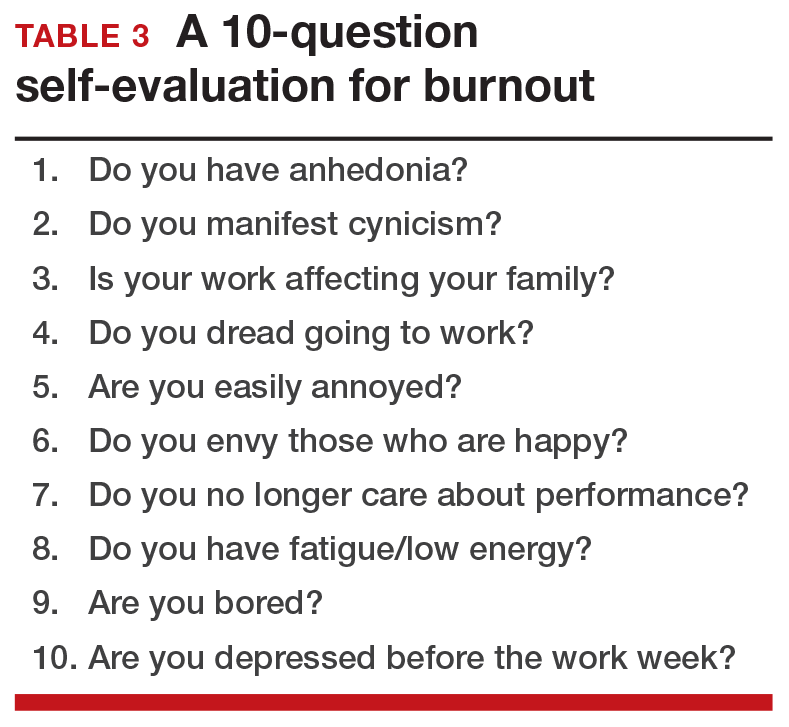

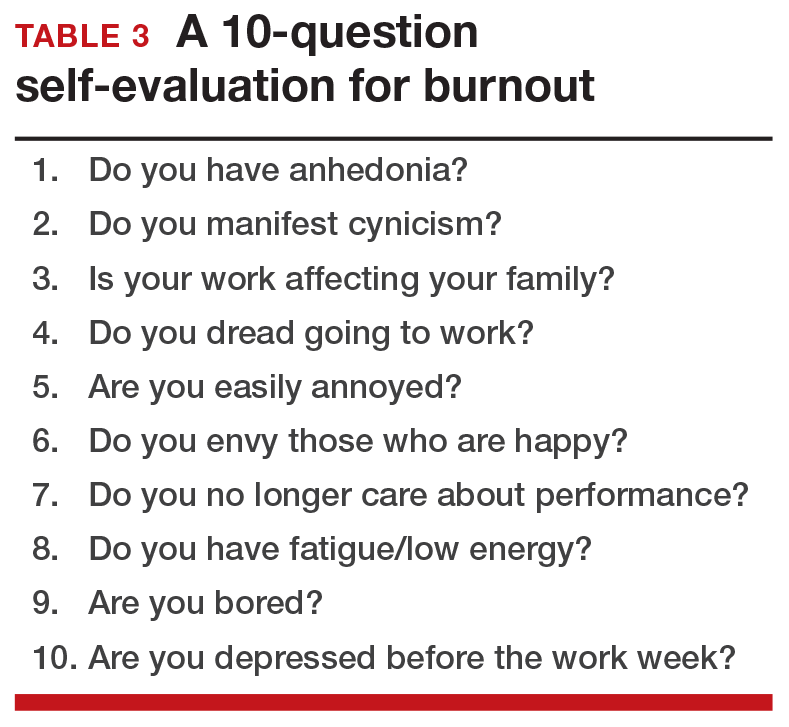

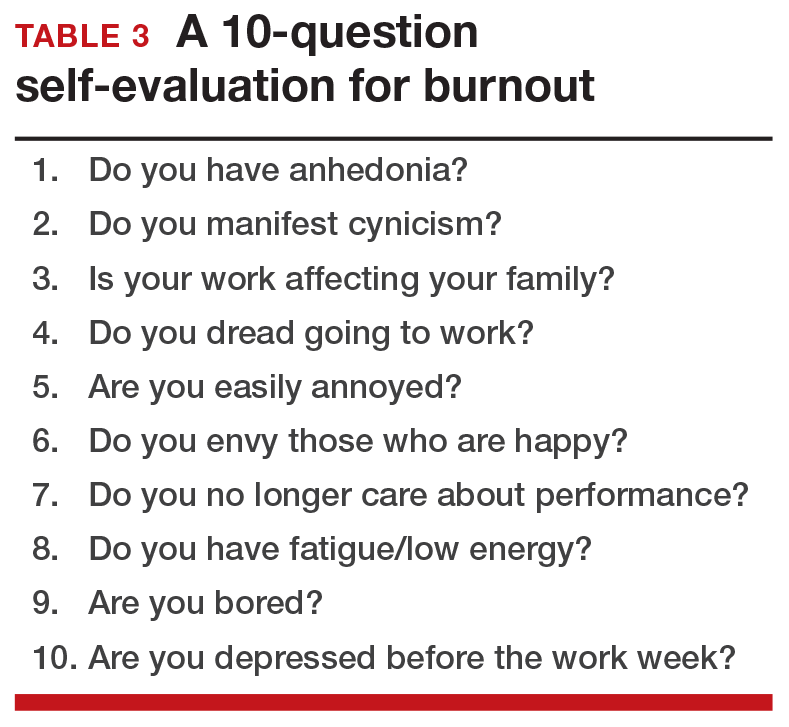

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)

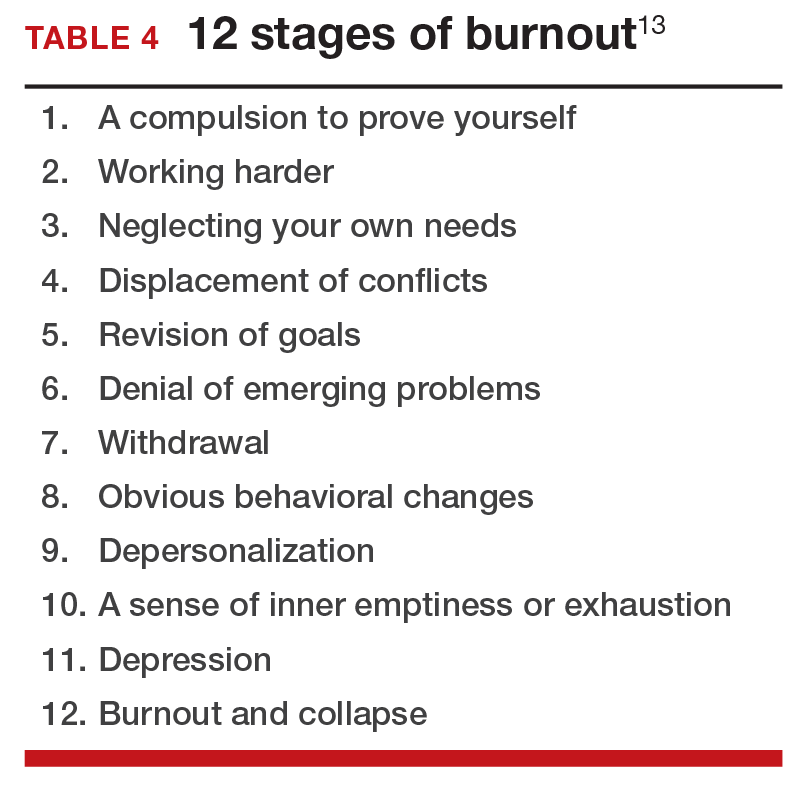

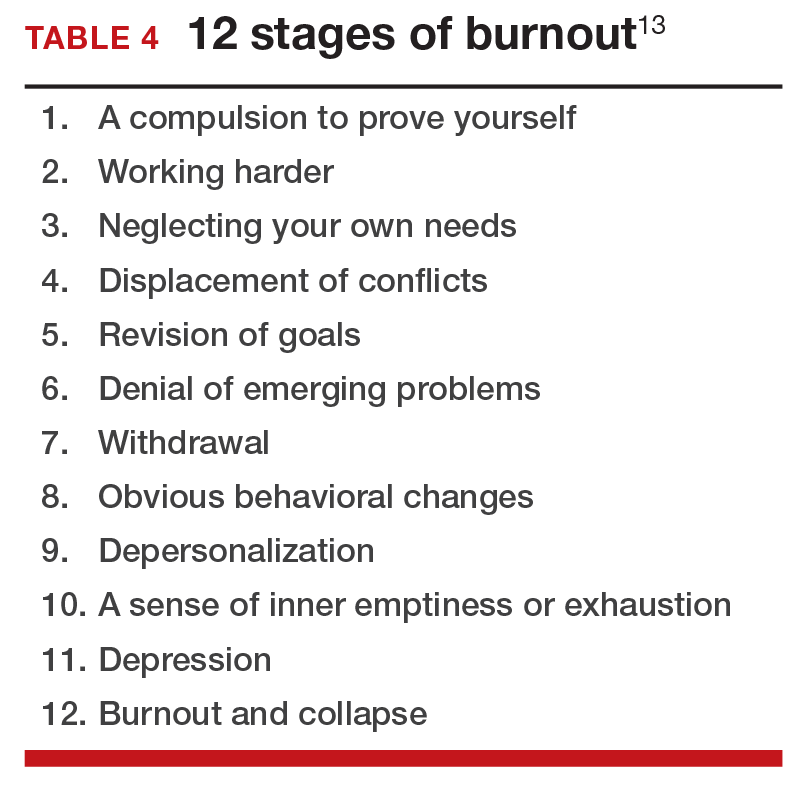

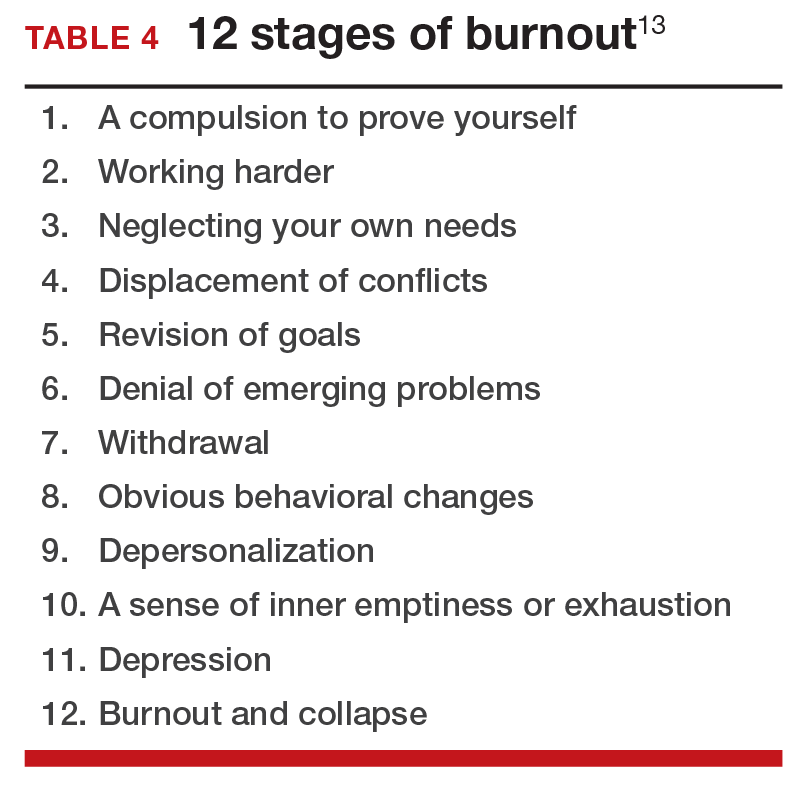

12 stages of burnout. Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North have theorized that the burnout process can be divided into 12 phases (TABLE 4).13 These stages are not necessarily sequential—some may be absent and others may present simultaneously. It is easy to see how these can represent stages in a potentially spiraling series of behaviors and changes that result in complete dysfunction. It is also easy to understand that the characteristics that are associated with success in medical school, clinical training, and practice, such as high expectations, placing the needs of others above our own, and a desire to prove oneself, virtually define the first 3 stages.

Approaches for burnout control and prevention

There are some simple steps we can take to reduce the risk of burnout or to reverse its effects. Because fatigue and stress are 2 of the greatest risk factors, reducing these is a good place to start.

Prioritize sleep. When it comes to fatigue, that one is easy: get some sleep. Physicians tend to sleep fewer hours than the general population and what we get is often not the type that is restful and restorative.14 Just reducing the number of hours worked is not enough, as a number of studies have found.15 The rest must result in relaxation.

e Stress reduction may seem a more difficult goal than getting more sleep. In reality, there are several simple approaches to use to reduce stress:

- Even though we all have busy clinical schedules, take short breaks to rest, sing, laugh, and exercise. Even breaks as short as 10 minutes can be effective.16

- Separate work from private life by taking a short break to resolve issues before heading home. Avoiding “baggage” or homework will go a long way to giving you the perspective you need from your time off. This may also mean that you have to delegate tasks, share chores, or get carry-out for dinner.

- Set meaningful and realistic goals for yourself professionally and personally. Do not expect or demand more than is possible. This will mean setting priorities and recognizing that some tasks may have to wait.

- Finally, do not forget to pay yourself with hobbies and activities that you enjoy.

Take action

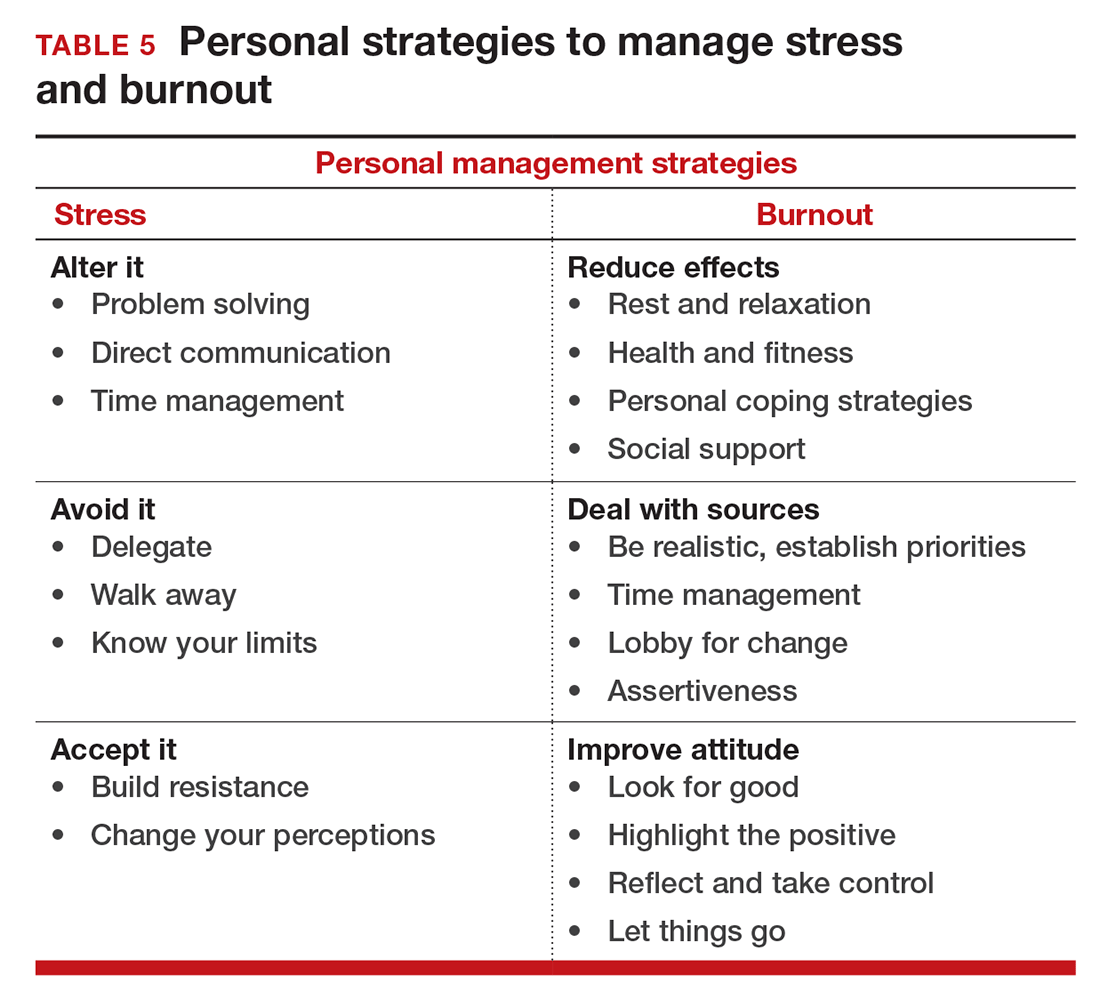

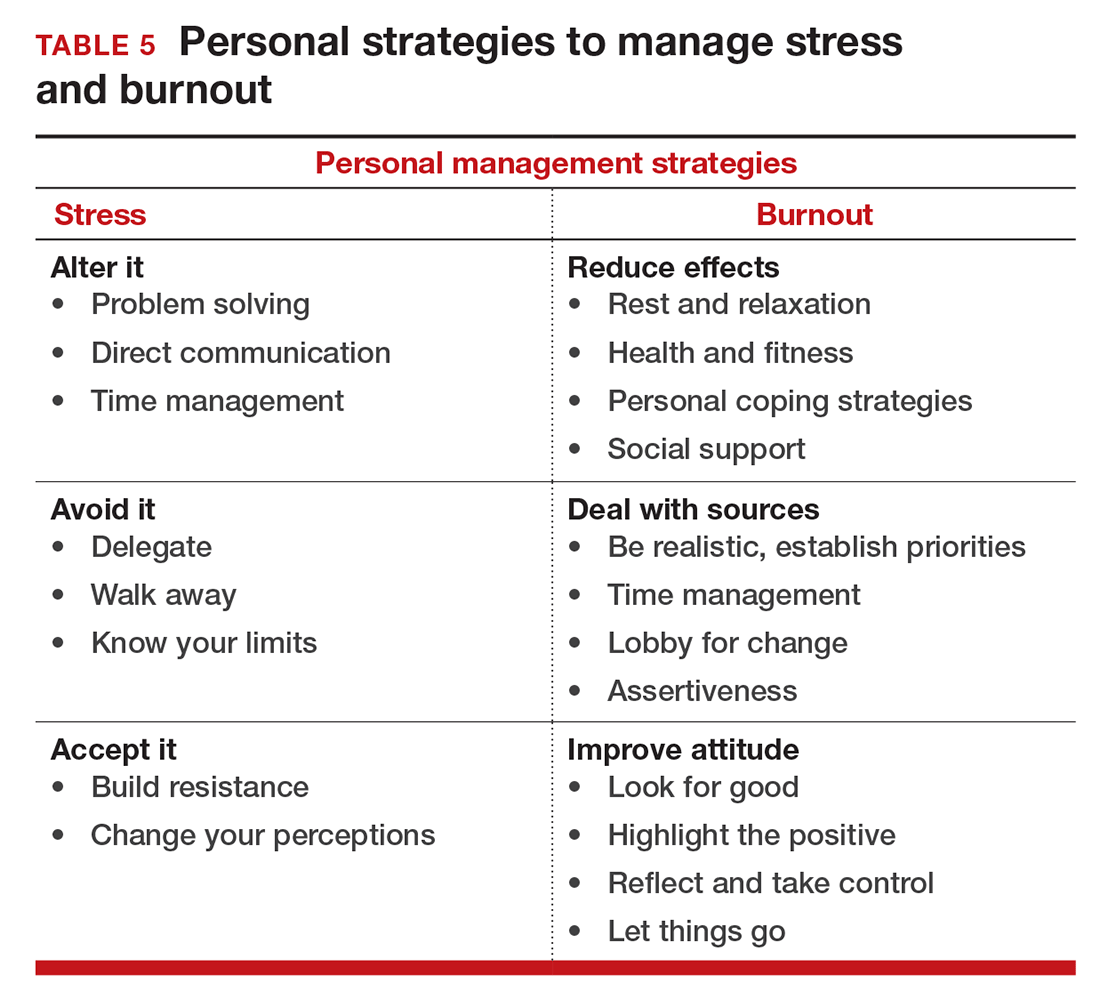

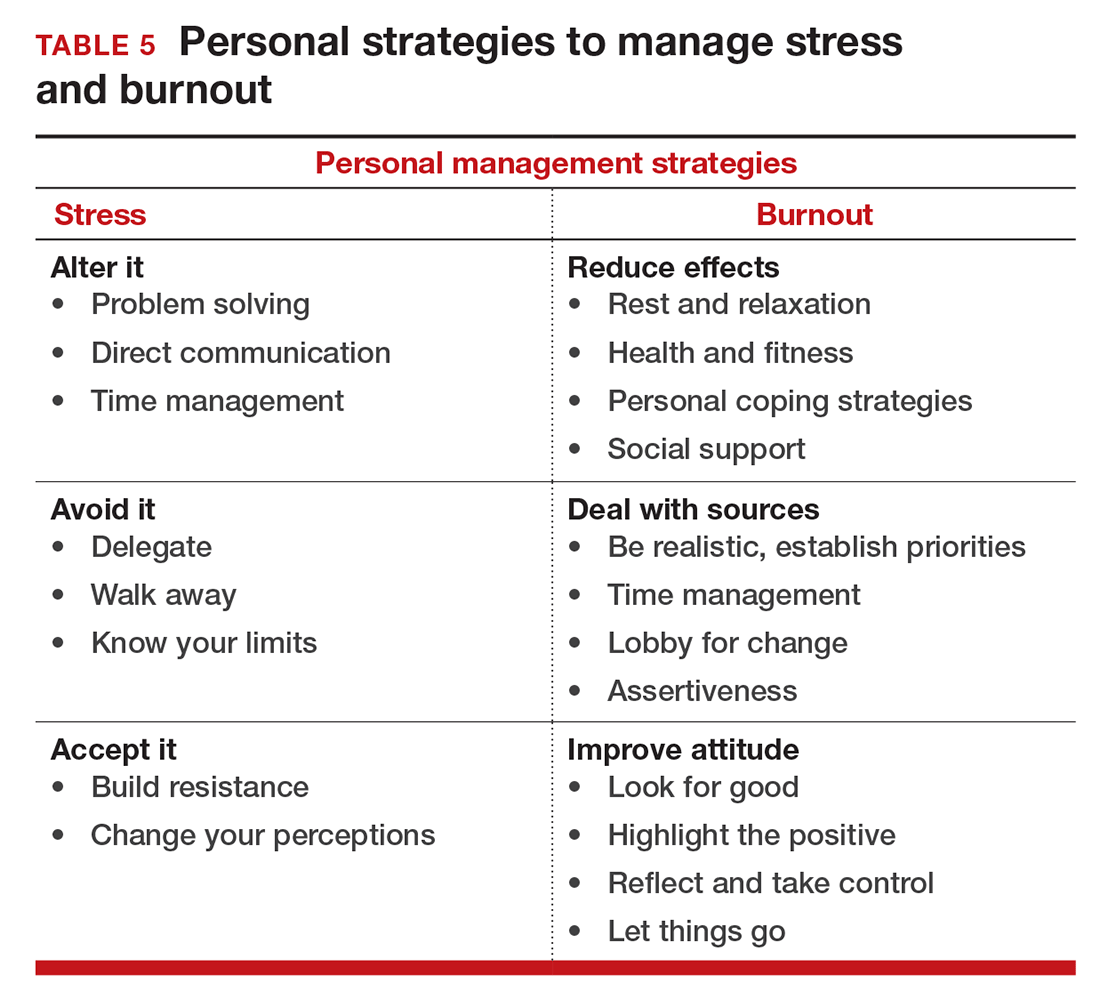

If you feel the effects of burnout tugging at your coattails, you can reduce the effects, deal with the sources, and improve your attitude (TABLE 5). Rest and relaxation will go a long way to helping, but do not forget to take care of your physical well-being with a healthy diet, exercise, and health checkups. Deal with the sources of burnout by identifying the stressors, setting realistic priorities, and practicing good time management.

You also should lobby for changes that will increase your control and reduce unnecessary obstacles to completing your goals. Be your own best advocate. Look for the good and try to identify at least one instance during the day where your presence or acts made a difference. In the end, it is like Smokey the Bear says, “Only you can prevent burnout.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):949-955.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848.

- Gabbe SG, Melville J, Mandel L, Walker E. Burnout in chairs of obstetrics and gynecology: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):601-612.

- Kok BC, Herrell RK, Grossman SH, West JC, Wilk JE. Prevalence of professional burnout among military mental health service providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(1):137-140.

- Humphries N, Morgan K, Conry MC, McGowan Y, Montgomery A, McGee H. Quality of care and health professional burnout: narrative literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(4):293-307.

- Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

- Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population--results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(1):59-66.

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):192-207.

- Bianchi R, Boffy C, Hingray C, Truchot D, Laurent E. Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):782-787.

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld I S, Laurent E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A re-examination with special focus on atypical depression. Intl J Stress Manag. 2014;21(4):307-324.

- Freudenberger HJ, North G. Women's burnout: How to spot it, how to reverse it, and how to prevent it. New York, New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Abrams RM. Sleep deprivation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(3):493-506.

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54.

- Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: The personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

Does stress cause burnout?

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)

12 stages of burnout. Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North have theorized that the burnout process can be divided into 12 phases (TABLE 4).13 These stages are not necessarily sequential—some may be absent and others may present simultaneously. It is easy to see how these can represent stages in a potentially spiraling series of behaviors and changes that result in complete dysfunction. It is also easy to understand that the characteristics that are associated with success in medical school, clinical training, and practice, such as high expectations, placing the needs of others above our own, and a desire to prove oneself, virtually define the first 3 stages.

Approaches for burnout control and prevention

There are some simple steps we can take to reduce the risk of burnout or to reverse its effects. Because fatigue and stress are 2 of the greatest risk factors, reducing these is a good place to start.

Prioritize sleep. When it comes to fatigue, that one is easy: get some sleep. Physicians tend to sleep fewer hours than the general population and what we get is often not the type that is restful and restorative.14 Just reducing the number of hours worked is not enough, as a number of studies have found.15 The rest must result in relaxation.

e Stress reduction may seem a more difficult goal than getting more sleep. In reality, there are several simple approaches to use to reduce stress:

- Even though we all have busy clinical schedules, take short breaks to rest, sing, laugh, and exercise. Even breaks as short as 10 minutes can be effective.16

- Separate work from private life by taking a short break to resolve issues before heading home. Avoiding “baggage” or homework will go a long way to giving you the perspective you need from your time off. This may also mean that you have to delegate tasks, share chores, or get carry-out for dinner.

- Set meaningful and realistic goals for yourself professionally and personally. Do not expect or demand more than is possible. This will mean setting priorities and recognizing that some tasks may have to wait.

- Finally, do not forget to pay yourself with hobbies and activities that you enjoy.

Take action

If you feel the effects of burnout tugging at your coattails, you can reduce the effects, deal with the sources, and improve your attitude (TABLE 5). Rest and relaxation will go a long way to helping, but do not forget to take care of your physical well-being with a healthy diet, exercise, and health checkups. Deal with the sources of burnout by identifying the stressors, setting realistic priorities, and practicing good time management.

You also should lobby for changes that will increase your control and reduce unnecessary obstacles to completing your goals. Be your own best advocate. Look for the good and try to identify at least one instance during the day where your presence or acts made a difference. In the end, it is like Smokey the Bear says, “Only you can prevent burnout.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

Does stress cause burnout?

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)