User login

Ataxia due to alcohol abuse

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Sanofi Gets $43 M U.S. Funding to Spur Zika Vaccine Development

(Reuters) - Sanofi SA said on Monday the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) approved $43.18 million in funding to accelerate the development of a Zika vaccine, as efforts to prevent the infection gather momentum.

The funding from the HHS' Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) will be used for mid-stage trials, expected to begin in the first half of 2018, and for manufacturing, the French drugmaker said.

The contract runs through June 2022, but if the data is positive, the contract includes an option for up to additional $130.45 million for late-stage trials necessary for eventual approval.

Work on the vaccine began in March as a collaborative effort between the U.S. Department Of Defense's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), BARDA and the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi in July teamed up with WRAIR to co-develop the vaccine.

Earlier this month, BARDA gave Japanese drugmaker Takeda Pharmaceutical Co nearly $20 million in initial funding to develop a Zika vaccine.

Sanofi is one of the many companies around the world looking to develop a vaccine against the virus that has spread rapidly since the current outbreak was first detected last year in Brazil.

Hundreds of thousands of people are estimated to have been infected with Zika in the Americas and parts of Asia. Most have no symptoms or experience only a mild illness.

The virus can penetrate the womb in pregnant women, causing a rare but crippling birth defect known as microcephaly. In adults, it has been linked to Guillain-Barre syndrome, a form of temporary paralysis.

Zika, a member of the flavivirus species that includes dengue, yellow fever and West Nile virus, is typically spread by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

It can be also passed on through sex, a unique characteristic among mosquito-borne viruses.

Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccine unit of Sanofi, already has several vaccines approved for others flaviviruses, such as yellow fever, dengue and Japanese encephalitis.

As of September, the HHS has awarded at least $433 million in repurposed funds to support Zika response and preparedness activities.

(Reuters) - Sanofi SA said on Monday the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) approved $43.18 million in funding to accelerate the development of a Zika vaccine, as efforts to prevent the infection gather momentum.

The funding from the HHS' Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) will be used for mid-stage trials, expected to begin in the first half of 2018, and for manufacturing, the French drugmaker said.

The contract runs through June 2022, but if the data is positive, the contract includes an option for up to additional $130.45 million for late-stage trials necessary for eventual approval.

Work on the vaccine began in March as a collaborative effort between the U.S. Department Of Defense's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), BARDA and the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi in July teamed up with WRAIR to co-develop the vaccine.

Earlier this month, BARDA gave Japanese drugmaker Takeda Pharmaceutical Co nearly $20 million in initial funding to develop a Zika vaccine.

Sanofi is one of the many companies around the world looking to develop a vaccine against the virus that has spread rapidly since the current outbreak was first detected last year in Brazil.

Hundreds of thousands of people are estimated to have been infected with Zika in the Americas and parts of Asia. Most have no symptoms or experience only a mild illness.

The virus can penetrate the womb in pregnant women, causing a rare but crippling birth defect known as microcephaly. In adults, it has been linked to Guillain-Barre syndrome, a form of temporary paralysis.

Zika, a member of the flavivirus species that includes dengue, yellow fever and West Nile virus, is typically spread by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

It can be also passed on through sex, a unique characteristic among mosquito-borne viruses.

Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccine unit of Sanofi, already has several vaccines approved for others flaviviruses, such as yellow fever, dengue and Japanese encephalitis.

As of September, the HHS has awarded at least $433 million in repurposed funds to support Zika response and preparedness activities.

(Reuters) - Sanofi SA said on Monday the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) approved $43.18 million in funding to accelerate the development of a Zika vaccine, as efforts to prevent the infection gather momentum.

The funding from the HHS' Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) will be used for mid-stage trials, expected to begin in the first half of 2018, and for manufacturing, the French drugmaker said.

The contract runs through June 2022, but if the data is positive, the contract includes an option for up to additional $130.45 million for late-stage trials necessary for eventual approval.

Work on the vaccine began in March as a collaborative effort between the U.S. Department Of Defense's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), BARDA and the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi in July teamed up with WRAIR to co-develop the vaccine.

Earlier this month, BARDA gave Japanese drugmaker Takeda Pharmaceutical Co nearly $20 million in initial funding to develop a Zika vaccine.

Sanofi is one of the many companies around the world looking to develop a vaccine against the virus that has spread rapidly since the current outbreak was first detected last year in Brazil.

Hundreds of thousands of people are estimated to have been infected with Zika in the Americas and parts of Asia. Most have no symptoms or experience only a mild illness.

The virus can penetrate the womb in pregnant women, causing a rare but crippling birth defect known as microcephaly. In adults, it has been linked to Guillain-Barre syndrome, a form of temporary paralysis.

Zika, a member of the flavivirus species that includes dengue, yellow fever and West Nile virus, is typically spread by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

It can be also passed on through sex, a unique characteristic among mosquito-borne viruses.

Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccine unit of Sanofi, already has several vaccines approved for others flaviviruses, such as yellow fever, dengue and Japanese encephalitis.

As of September, the HHS has awarded at least $433 million in repurposed funds to support Zika response and preparedness activities.

Coordinating Better Care for Opioid-Addicted Women and Their Children

Caring for a woman who is addicted to opioids—and who is a mother or about to be—can be challenging. But child welfare systems are reporting heavier caseloads, primarily among infants and young children. Moreover, hospitals are reporting increasing numbers of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

As part of HHS’s overall initiative to address the many public health problems posed by the opioid disorder crisis, SAMHSA, with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, is releasing A Collaborative Approach to the Treatment of Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorders.

The guide is aimed at promoting a coordinated multisystemic approach among agencies and providers, including child welfare, medical, and substance abuse treatment, grounded in early identification and interventions to support families.

The publication covers the extent of opioid use by pregnant women and its effects on their fetus. It offers evidence-based recommendations for treatment approaches, along with recommendations for collaborative planning and tools to conduct a needs-and-gap analysis to develop a collaborative action plan.

SAMHSA also publishes Advancing the Care of Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants: A Foundation for Clinical Guidance. This report summarizes the evidence review and rating processes SAMHSA used to establish appropriate interventions.

Caring for a woman who is addicted to opioids—and who is a mother or about to be—can be challenging. But child welfare systems are reporting heavier caseloads, primarily among infants and young children. Moreover, hospitals are reporting increasing numbers of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

As part of HHS’s overall initiative to address the many public health problems posed by the opioid disorder crisis, SAMHSA, with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, is releasing A Collaborative Approach to the Treatment of Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorders.

The guide is aimed at promoting a coordinated multisystemic approach among agencies and providers, including child welfare, medical, and substance abuse treatment, grounded in early identification and interventions to support families.

The publication covers the extent of opioid use by pregnant women and its effects on their fetus. It offers evidence-based recommendations for treatment approaches, along with recommendations for collaborative planning and tools to conduct a needs-and-gap analysis to develop a collaborative action plan.

SAMHSA also publishes Advancing the Care of Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants: A Foundation for Clinical Guidance. This report summarizes the evidence review and rating processes SAMHSA used to establish appropriate interventions.

Caring for a woman who is addicted to opioids—and who is a mother or about to be—can be challenging. But child welfare systems are reporting heavier caseloads, primarily among infants and young children. Moreover, hospitals are reporting increasing numbers of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

As part of HHS’s overall initiative to address the many public health problems posed by the opioid disorder crisis, SAMHSA, with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, is releasing A Collaborative Approach to the Treatment of Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorders.

The guide is aimed at promoting a coordinated multisystemic approach among agencies and providers, including child welfare, medical, and substance abuse treatment, grounded in early identification and interventions to support families.

The publication covers the extent of opioid use by pregnant women and its effects on their fetus. It offers evidence-based recommendations for treatment approaches, along with recommendations for collaborative planning and tools to conduct a needs-and-gap analysis to develop a collaborative action plan.

SAMHSA also publishes Advancing the Care of Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants: A Foundation for Clinical Guidance. This report summarizes the evidence review and rating processes SAMHSA used to establish appropriate interventions.

An Atypical Angiomyomatous Hamartoma With Unexplained Hepatosplenomegaly

Angiomyomatous hamartoma (AMH) of the lymph node is an extremely uncommon vascular disorder of unknown etiology, first described by Chan and colleagues in 1992.1-3 Angiomyomatous hamartoma particularly involves inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, with few cases reported in the cervical, popliteal, and submandibular lymph nodes.1 Angiomyomatous hamartoma can occasionally be associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb. To the authors’ knowledge, to date only 18 cases of AMH have been reported.4

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white man started to have a left inguinal and scrotal pain along with left thigh swelling at age 22 while serving in the U.S. Army.

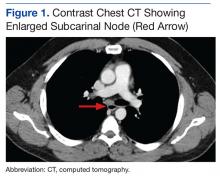

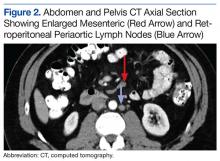

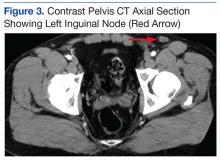

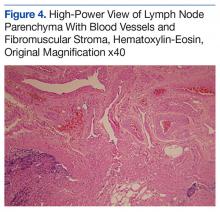

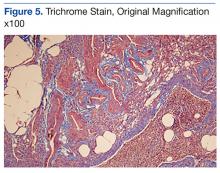

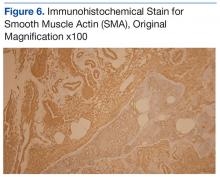

An abdominal Doppler ultrasound did not show any evidence of portal hypertension. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral axillary, subcarinal (Figure 1), mesenteric and retroperitoneal (Figure 2), and left inguinal (Figure 3) lymphadenopathy. Excisional biopsy of a 3.5 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm left inguinal lymph node was performed, and histopathology showed extensive smooth muscle and vascular proliferation replacing most of the lymph node (Figure 4), a finding consistent with AMH. A trichrome staining (Figure 5) and immunohistochemical study for smooth muscle actin (Figure 6) were performed and supported the diagnosis. Due to persistent pain in the scrotal area, the patient underwent a left spermatic cord denervation. Currently, the patient has persistent left thigh swelling. His condition remains stable with a regular follow-up CT scan showing unchanged lymphadenopathy.

Discussion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma is a rare, primary vascular tumor of the lymph nodes occurring almost exclusively in the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes and occasionally associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb.1 A few cases with popliteal and cervical lymph node involvement have been reported.1 There are no prior reports of cases with either generalized adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

The histopathogenesis of AMH remains unclear. Chan and colleagues first reported this distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1992 as a primary vascular tumor of the lymph node.1-3 The hamartomatous nature of the disease was postulated by the authors on the basis of a disorganized growth pattern of smooth muscle cells and blood vessels noted on pathology.2,3 The AMH could represent a localized malformation in a congenitally damaged lymphatic vessel system.5 Other hypothesis suggests lymphedema as a possible etiology of AMH through continuous stimulation of lymphatic vessels, which triggers vasoproliferation and eventually the vascular transformation of the lymph nodes.5

Differential diagnoses of AMH include nodal lymphangiomyomatosis, which is most prevalent in women, particularly presenting with thoracic and intra-abdominal lymph nodes and plumper HMB45 (human melanoma black 45) -positive tumor cells6; leiomyomato

Treatment is either conservative or surgical, depending on clinical judgment. This is only the 19th case of AMH reported so far in the literature and the fifth reported case in which the patient presented with ipsilateral lymphedema of the limb. Importantly, it is the first reported case with generalized (axillary, subcarinal, mesenteric, inguinal and retroperitoneal) lymphadenopathy and unexplained hepatosplenomegaly.

Conclusion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph nodes is an exceedingly rare diagnosis but should be considered when evaluating patients with lymphatic tumors. This patient remains relatively asymptomatic and on observation at this time and seems to have more extensive disease than prior reports in the literature.

1. Mridha AR, Ranjan R, Kinra P, Ray R, Khan SA, Shivanand G. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of popliteal lymph node: an unusual entity. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49(2):156-158.

2. Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Verdebout JM, Bourgeois P, Munck D. Glomeruloid microvascular proliferation in angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph node. Virchows Arch. 2004;445(3):320-322.

3. Chan JK, Frizzera G, Fletcher CD, Rosai J. Primary vascular tumors of lymph nodes other than Kaposi’s sarcoma. Analysis of 39 cases and delineation of two new entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(4):335-350.

4. Ram M, Alsanjari N, Ansari N. Angiomyomatous hamartoma: a rare case report with review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1(2):e25.

5. Piedimonte A, De Nictolis M, Lorenzini P, Sperti V, Bertani A. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of inguinal lymph nodes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):714-716.

6. Lee CH, Chang TC, Ku JW. Angiomyomatous hamartoma in an inguinal lymph node with proliferating pericytes/smooth muscle cells, plexiform vessel tangles, and ectopic calcification. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58(2):226-228.

Angiomyomatous hamartoma (AMH) of the lymph node is an extremely uncommon vascular disorder of unknown etiology, first described by Chan and colleagues in 1992.1-3 Angiomyomatous hamartoma particularly involves inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, with few cases reported in the cervical, popliteal, and submandibular lymph nodes.1 Angiomyomatous hamartoma can occasionally be associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb. To the authors’ knowledge, to date only 18 cases of AMH have been reported.4

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white man started to have a left inguinal and scrotal pain along with left thigh swelling at age 22 while serving in the U.S. Army.

An abdominal Doppler ultrasound did not show any evidence of portal hypertension. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral axillary, subcarinal (Figure 1), mesenteric and retroperitoneal (Figure 2), and left inguinal (Figure 3) lymphadenopathy. Excisional biopsy of a 3.5 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm left inguinal lymph node was performed, and histopathology showed extensive smooth muscle and vascular proliferation replacing most of the lymph node (Figure 4), a finding consistent with AMH. A trichrome staining (Figure 5) and immunohistochemical study for smooth muscle actin (Figure 6) were performed and supported the diagnosis. Due to persistent pain in the scrotal area, the patient underwent a left spermatic cord denervation. Currently, the patient has persistent left thigh swelling. His condition remains stable with a regular follow-up CT scan showing unchanged lymphadenopathy.

Discussion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma is a rare, primary vascular tumor of the lymph nodes occurring almost exclusively in the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes and occasionally associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb.1 A few cases with popliteal and cervical lymph node involvement have been reported.1 There are no prior reports of cases with either generalized adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

The histopathogenesis of AMH remains unclear. Chan and colleagues first reported this distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1992 as a primary vascular tumor of the lymph node.1-3 The hamartomatous nature of the disease was postulated by the authors on the basis of a disorganized growth pattern of smooth muscle cells and blood vessels noted on pathology.2,3 The AMH could represent a localized malformation in a congenitally damaged lymphatic vessel system.5 Other hypothesis suggests lymphedema as a possible etiology of AMH through continuous stimulation of lymphatic vessels, which triggers vasoproliferation and eventually the vascular transformation of the lymph nodes.5

Differential diagnoses of AMH include nodal lymphangiomyomatosis, which is most prevalent in women, particularly presenting with thoracic and intra-abdominal lymph nodes and plumper HMB45 (human melanoma black 45) -positive tumor cells6; leiomyomato

Treatment is either conservative or surgical, depending on clinical judgment. This is only the 19th case of AMH reported so far in the literature and the fifth reported case in which the patient presented with ipsilateral lymphedema of the limb. Importantly, it is the first reported case with generalized (axillary, subcarinal, mesenteric, inguinal and retroperitoneal) lymphadenopathy and unexplained hepatosplenomegaly.

Conclusion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph nodes is an exceedingly rare diagnosis but should be considered when evaluating patients with lymphatic tumors. This patient remains relatively asymptomatic and on observation at this time and seems to have more extensive disease than prior reports in the literature.

Angiomyomatous hamartoma (AMH) of the lymph node is an extremely uncommon vascular disorder of unknown etiology, first described by Chan and colleagues in 1992.1-3 Angiomyomatous hamartoma particularly involves inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, with few cases reported in the cervical, popliteal, and submandibular lymph nodes.1 Angiomyomatous hamartoma can occasionally be associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb. To the authors’ knowledge, to date only 18 cases of AMH have been reported.4

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white man started to have a left inguinal and scrotal pain along with left thigh swelling at age 22 while serving in the U.S. Army.

An abdominal Doppler ultrasound did not show any evidence of portal hypertension. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral axillary, subcarinal (Figure 1), mesenteric and retroperitoneal (Figure 2), and left inguinal (Figure 3) lymphadenopathy. Excisional biopsy of a 3.5 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm left inguinal lymph node was performed, and histopathology showed extensive smooth muscle and vascular proliferation replacing most of the lymph node (Figure 4), a finding consistent with AMH. A trichrome staining (Figure 5) and immunohistochemical study for smooth muscle actin (Figure 6) were performed and supported the diagnosis. Due to persistent pain in the scrotal area, the patient underwent a left spermatic cord denervation. Currently, the patient has persistent left thigh swelling. His condition remains stable with a regular follow-up CT scan showing unchanged lymphadenopathy.

Discussion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma is a rare, primary vascular tumor of the lymph nodes occurring almost exclusively in the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes and occasionally associated with edema of the ipsilateral limb.1 A few cases with popliteal and cervical lymph node involvement have been reported.1 There are no prior reports of cases with either generalized adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

The histopathogenesis of AMH remains unclear. Chan and colleagues first reported this distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1992 as a primary vascular tumor of the lymph node.1-3 The hamartomatous nature of the disease was postulated by the authors on the basis of a disorganized growth pattern of smooth muscle cells and blood vessels noted on pathology.2,3 The AMH could represent a localized malformation in a congenitally damaged lymphatic vessel system.5 Other hypothesis suggests lymphedema as a possible etiology of AMH through continuous stimulation of lymphatic vessels, which triggers vasoproliferation and eventually the vascular transformation of the lymph nodes.5

Differential diagnoses of AMH include nodal lymphangiomyomatosis, which is most prevalent in women, particularly presenting with thoracic and intra-abdominal lymph nodes and plumper HMB45 (human melanoma black 45) -positive tumor cells6; leiomyomato

Treatment is either conservative or surgical, depending on clinical judgment. This is only the 19th case of AMH reported so far in the literature and the fifth reported case in which the patient presented with ipsilateral lymphedema of the limb. Importantly, it is the first reported case with generalized (axillary, subcarinal, mesenteric, inguinal and retroperitoneal) lymphadenopathy and unexplained hepatosplenomegaly.

Conclusion

Angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph nodes is an exceedingly rare diagnosis but should be considered when evaluating patients with lymphatic tumors. This patient remains relatively asymptomatic and on observation at this time and seems to have more extensive disease than prior reports in the literature.

1. Mridha AR, Ranjan R, Kinra P, Ray R, Khan SA, Shivanand G. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of popliteal lymph node: an unusual entity. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49(2):156-158.

2. Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Verdebout JM, Bourgeois P, Munck D. Glomeruloid microvascular proliferation in angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph node. Virchows Arch. 2004;445(3):320-322.

3. Chan JK, Frizzera G, Fletcher CD, Rosai J. Primary vascular tumors of lymph nodes other than Kaposi’s sarcoma. Analysis of 39 cases and delineation of two new entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(4):335-350.

4. Ram M, Alsanjari N, Ansari N. Angiomyomatous hamartoma: a rare case report with review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1(2):e25.

5. Piedimonte A, De Nictolis M, Lorenzini P, Sperti V, Bertani A. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of inguinal lymph nodes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):714-716.

6. Lee CH, Chang TC, Ku JW. Angiomyomatous hamartoma in an inguinal lymph node with proliferating pericytes/smooth muscle cells, plexiform vessel tangles, and ectopic calcification. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58(2):226-228.

1. Mridha AR, Ranjan R, Kinra P, Ray R, Khan SA, Shivanand G. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of popliteal lymph node: an unusual entity. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49(2):156-158.

2. Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Verdebout JM, Bourgeois P, Munck D. Glomeruloid microvascular proliferation in angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph node. Virchows Arch. 2004;445(3):320-322.

3. Chan JK, Frizzera G, Fletcher CD, Rosai J. Primary vascular tumors of lymph nodes other than Kaposi’s sarcoma. Analysis of 39 cases and delineation of two new entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(4):335-350.

4. Ram M, Alsanjari N, Ansari N. Angiomyomatous hamartoma: a rare case report with review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1(2):e25.

5. Piedimonte A, De Nictolis M, Lorenzini P, Sperti V, Bertani A. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of inguinal lymph nodes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):714-716.

6. Lee CH, Chang TC, Ku JW. Angiomyomatous hamartoma in an inguinal lymph node with proliferating pericytes/smooth muscle cells, plexiform vessel tangles, and ectopic calcification. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58(2):226-228.

Companies withheld info related to rivaroxaban trial, BMJ says

The pharmaceutical companies developing the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) withheld information about the system used to measure international normalized ratios (INRs) in the ROCKET AF trial, according to an investigation published in The BMJ.

ROCKET AF was used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the US and European Union, and the Alere INRatio Monitor System was used to measure INRs in the warfarin arm of the trial.

The system was later recalled because it was shown to provide falsely low test results.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer, the companies developing rivaroxaban, knew about concerns regarding the accuracy of the INRatio system while ROCKET AF was underway but allowed the system to be used in the trial anyway.

The companies also neglected to mention these concerns to regulatory authorities prior to rivaroxaban’s approval and later failed to notify regulators about the recall of the INRatio system and its potential impact on ROCKET AF.

In addition, Janssen, which was responsible for conducting ROCKET AF, did not tell regulators about a safety program the company launched during the trial to address concerns about the INRatio system.

In fact, The BMJ’s investigation suggests Janssen kept this program a secret from ROCKET AF investigators, the trial’s data and safety monitoring board, and Bayer.

How the events unfolded

ROCKET AF, which was launched in February 2007, was a comparison of rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

Results from the trial, published in NEJM in August 2011, suggested rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke or systemic embolism. And there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to major or nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding.

These results were used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the European Union in September 2011 and in the US in November 2011.

A number of critics, including The BMJ, have questioned the results of ROCKET AF because the INRatio system (INRatio Monitor or INRatio2 Monitor and INRatio Test Strips) has been shown to give falsely low test results.

The system was recalled for certain patients in December 2014 and was withdrawn from the market in July 2016.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer did not inform regulatory authorities about the December 2014 recall—and how issues with the INRatio system may have affected ROCKET AF—until The BMJ probed them in September 2015.

Once the authorities knew, they launched investigations. In February 2016, the European Medicine’s Agency (EMA) released a statement saying the defect with the INRatio system does not change the overall conclusions of ROCKET AF.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is still conducting its investigation but has not changed its recommendations regarding rivaroxaban.

The BMJ also reported that ROCKET AF’s executive committee and trial investigators raised concerns about the INRatio system shortly after the trial began.

Both Janssen and Bayer were aware of these concerns but did not disclose them to the FDA or EMA before rivaroxaban was approved.

Instead, Janssen launched the Covance recheck program in early 2008. This safety program involved an unblinded monitor checking INRatio readings against lab results if an investigator had concerns about the INRatio system.

Janssen did not inform ROCKET AF investigators or the trial’s data and safety monitoring board of the program. Bayer said it did not know about the program until this year, and the FDA and EMA have said the same. ![]()

The pharmaceutical companies developing the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) withheld information about the system used to measure international normalized ratios (INRs) in the ROCKET AF trial, according to an investigation published in The BMJ.

ROCKET AF was used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the US and European Union, and the Alere INRatio Monitor System was used to measure INRs in the warfarin arm of the trial.

The system was later recalled because it was shown to provide falsely low test results.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer, the companies developing rivaroxaban, knew about concerns regarding the accuracy of the INRatio system while ROCKET AF was underway but allowed the system to be used in the trial anyway.

The companies also neglected to mention these concerns to regulatory authorities prior to rivaroxaban’s approval and later failed to notify regulators about the recall of the INRatio system and its potential impact on ROCKET AF.

In addition, Janssen, which was responsible for conducting ROCKET AF, did not tell regulators about a safety program the company launched during the trial to address concerns about the INRatio system.

In fact, The BMJ’s investigation suggests Janssen kept this program a secret from ROCKET AF investigators, the trial’s data and safety monitoring board, and Bayer.

How the events unfolded

ROCKET AF, which was launched in February 2007, was a comparison of rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

Results from the trial, published in NEJM in August 2011, suggested rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke or systemic embolism. And there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to major or nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding.

These results were used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the European Union in September 2011 and in the US in November 2011.

A number of critics, including The BMJ, have questioned the results of ROCKET AF because the INRatio system (INRatio Monitor or INRatio2 Monitor and INRatio Test Strips) has been shown to give falsely low test results.

The system was recalled for certain patients in December 2014 and was withdrawn from the market in July 2016.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer did not inform regulatory authorities about the December 2014 recall—and how issues with the INRatio system may have affected ROCKET AF—until The BMJ probed them in September 2015.

Once the authorities knew, they launched investigations. In February 2016, the European Medicine’s Agency (EMA) released a statement saying the defect with the INRatio system does not change the overall conclusions of ROCKET AF.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is still conducting its investigation but has not changed its recommendations regarding rivaroxaban.

The BMJ also reported that ROCKET AF’s executive committee and trial investigators raised concerns about the INRatio system shortly after the trial began.

Both Janssen and Bayer were aware of these concerns but did not disclose them to the FDA or EMA before rivaroxaban was approved.

Instead, Janssen launched the Covance recheck program in early 2008. This safety program involved an unblinded monitor checking INRatio readings against lab results if an investigator had concerns about the INRatio system.

Janssen did not inform ROCKET AF investigators or the trial’s data and safety monitoring board of the program. Bayer said it did not know about the program until this year, and the FDA and EMA have said the same. ![]()

The pharmaceutical companies developing the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) withheld information about the system used to measure international normalized ratios (INRs) in the ROCKET AF trial, according to an investigation published in The BMJ.

ROCKET AF was used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the US and European Union, and the Alere INRatio Monitor System was used to measure INRs in the warfarin arm of the trial.

The system was later recalled because it was shown to provide falsely low test results.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer, the companies developing rivaroxaban, knew about concerns regarding the accuracy of the INRatio system while ROCKET AF was underway but allowed the system to be used in the trial anyway.

The companies also neglected to mention these concerns to regulatory authorities prior to rivaroxaban’s approval and later failed to notify regulators about the recall of the INRatio system and its potential impact on ROCKET AF.

In addition, Janssen, which was responsible for conducting ROCKET AF, did not tell regulators about a safety program the company launched during the trial to address concerns about the INRatio system.

In fact, The BMJ’s investigation suggests Janssen kept this program a secret from ROCKET AF investigators, the trial’s data and safety monitoring board, and Bayer.

How the events unfolded

ROCKET AF, which was launched in February 2007, was a comparison of rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

Results from the trial, published in NEJM in August 2011, suggested rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke or systemic embolism. And there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to major or nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding.

These results were used to support the approval of rivaroxaban in the European Union in September 2011 and in the US in November 2011.

A number of critics, including The BMJ, have questioned the results of ROCKET AF because the INRatio system (INRatio Monitor or INRatio2 Monitor and INRatio Test Strips) has been shown to give falsely low test results.

The system was recalled for certain patients in December 2014 and was withdrawn from the market in July 2016.

The BMJ said Janssen and Bayer did not inform regulatory authorities about the December 2014 recall—and how issues with the INRatio system may have affected ROCKET AF—until The BMJ probed them in September 2015.

Once the authorities knew, they launched investigations. In February 2016, the European Medicine’s Agency (EMA) released a statement saying the defect with the INRatio system does not change the overall conclusions of ROCKET AF.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is still conducting its investigation but has not changed its recommendations regarding rivaroxaban.

The BMJ also reported that ROCKET AF’s executive committee and trial investigators raised concerns about the INRatio system shortly after the trial began.

Both Janssen and Bayer were aware of these concerns but did not disclose them to the FDA or EMA before rivaroxaban was approved.

Instead, Janssen launched the Covance recheck program in early 2008. This safety program involved an unblinded monitor checking INRatio readings against lab results if an investigator had concerns about the INRatio system.

Janssen did not inform ROCKET AF investigators or the trial’s data and safety monitoring board of the program. Bayer said it did not know about the program until this year, and the FDA and EMA have said the same. ![]()

Ponatinib approved to treat CML, ALL in Japan

Image from UCSD

The Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) has approved 2 uses of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) ponatinib (Iclusig®).

The drug is now approved to treat recurrent or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that was resistant to or intolerant of prior treatment.

Ponatinib will be manufactured and sold by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Due to the limited existing treatment options for patients in Japan, Otsuka said it will provide access to ponatinib free of charge as soon as procedures are in place from an ethical standpoint.

This program will be offered at medical institutions where clinical trials of ponatinib were performed and which are amenable to accepting the drug access program until the product is listed on the Japan National Health Insurance price list.

About ponatinib

Ponatinib is a TKI discovered by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The drug has demonstrated activity against native and mutated BCR-ABL and other kinases.

The PMDA’s approval of ponatinib for CML and Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 1/2 trial of Japanese patients, a phase 1 trial, and the phase 2 PACE trial.

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the TKI were placed on partial hold while the US Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

Ponatinib was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of the TKI. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided its benefits outweigh its risks.

In addition to the European Union and the US, ponatinib has been approved in Australia, Canada, Israel, and Switzerland. ![]()

Image from UCSD

The Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) has approved 2 uses of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) ponatinib (Iclusig®).

The drug is now approved to treat recurrent or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that was resistant to or intolerant of prior treatment.

Ponatinib will be manufactured and sold by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Due to the limited existing treatment options for patients in Japan, Otsuka said it will provide access to ponatinib free of charge as soon as procedures are in place from an ethical standpoint.

This program will be offered at medical institutions where clinical trials of ponatinib were performed and which are amenable to accepting the drug access program until the product is listed on the Japan National Health Insurance price list.

About ponatinib

Ponatinib is a TKI discovered by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The drug has demonstrated activity against native and mutated BCR-ABL and other kinases.

The PMDA’s approval of ponatinib for CML and Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 1/2 trial of Japanese patients, a phase 1 trial, and the phase 2 PACE trial.

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the TKI were placed on partial hold while the US Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

Ponatinib was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of the TKI. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided its benefits outweigh its risks.

In addition to the European Union and the US, ponatinib has been approved in Australia, Canada, Israel, and Switzerland. ![]()

Image from UCSD

The Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) has approved 2 uses of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) ponatinib (Iclusig®).

The drug is now approved to treat recurrent or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that was resistant to or intolerant of prior treatment.

Ponatinib will be manufactured and sold by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Due to the limited existing treatment options for patients in Japan, Otsuka said it will provide access to ponatinib free of charge as soon as procedures are in place from an ethical standpoint.

This program will be offered at medical institutions where clinical trials of ponatinib were performed and which are amenable to accepting the drug access program until the product is listed on the Japan National Health Insurance price list.

About ponatinib

Ponatinib is a TKI discovered by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The drug has demonstrated activity against native and mutated BCR-ABL and other kinases.

The PMDA’s approval of ponatinib for CML and Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 1/2 trial of Japanese patients, a phase 1 trial, and the phase 2 PACE trial.

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the TKI were placed on partial hold while the US Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

Ponatinib was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of the TKI. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided its benefits outweigh its risks.

In addition to the European Union and the US, ponatinib has been approved in Australia, Canada, Israel, and Switzerland. ![]()

Study sheds light on platelet disorders

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research has unearthed additional information about how platelets respond to shear stress, answering a 20-year-old question.

Investigators said this research provides new insights regarding platelet activation and clearance as well as insights into the pathophysiology of von Willebrand disease and related thrombocytopenic disorders.

The team described this work in Nature Communications.

Past research suggested that platelets respond to shear stress through a protein complex called GPIb-IX located on the platelet surface, but how this complex senses and responds to shear stress has remained a mystery for the past 20 years.

With the current study, investigators found that, contrary to popular belief, a certain region within GPIb-IX is structured.

This so-called mechanosensory domain (MSD) becomes unfolded on the platelet surface when von Willebrand factor binds to the GPIbα subunit of GPIb–IX under shear stress and imposes a pulling force on it.

The unfolding of MSD sets off a complex chain of events and sends an intracellular signal into the platelet that results in rapid platelet clearance.

“Every day, your bone marrow generates more than a billion platelets, and, every day, you clear the same number,” said study author Renhao Li, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“It’s critical that your platelet count stays constant. Too few platelets can lead to . . . thrombocytopenia and may cause spontaneous bleeding or stroke. Thus, identifying the molecular ‘switch’ that triggers platelet clearance is important for designing new therapies to treat thrombocytopenia.”

The mechanism behind MSD-unfolding-induced platelet clearance is still unclear, but Dr Li said this research provides a good starting point for further inquiry into the phenomenon. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research has unearthed additional information about how platelets respond to shear stress, answering a 20-year-old question.

Investigators said this research provides new insights regarding platelet activation and clearance as well as insights into the pathophysiology of von Willebrand disease and related thrombocytopenic disorders.

The team described this work in Nature Communications.

Past research suggested that platelets respond to shear stress through a protein complex called GPIb-IX located on the platelet surface, but how this complex senses and responds to shear stress has remained a mystery for the past 20 years.

With the current study, investigators found that, contrary to popular belief, a certain region within GPIb-IX is structured.

This so-called mechanosensory domain (MSD) becomes unfolded on the platelet surface when von Willebrand factor binds to the GPIbα subunit of GPIb–IX under shear stress and imposes a pulling force on it.

The unfolding of MSD sets off a complex chain of events and sends an intracellular signal into the platelet that results in rapid platelet clearance.

“Every day, your bone marrow generates more than a billion platelets, and, every day, you clear the same number,” said study author Renhao Li, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“It’s critical that your platelet count stays constant. Too few platelets can lead to . . . thrombocytopenia and may cause spontaneous bleeding or stroke. Thus, identifying the molecular ‘switch’ that triggers platelet clearance is important for designing new therapies to treat thrombocytopenia.”

The mechanism behind MSD-unfolding-induced platelet clearance is still unclear, but Dr Li said this research provides a good starting point for further inquiry into the phenomenon. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research has unearthed additional information about how platelets respond to shear stress, answering a 20-year-old question.

Investigators said this research provides new insights regarding platelet activation and clearance as well as insights into the pathophysiology of von Willebrand disease and related thrombocytopenic disorders.

The team described this work in Nature Communications.

Past research suggested that platelets respond to shear stress through a protein complex called GPIb-IX located on the platelet surface, but how this complex senses and responds to shear stress has remained a mystery for the past 20 years.

With the current study, investigators found that, contrary to popular belief, a certain region within GPIb-IX is structured.

This so-called mechanosensory domain (MSD) becomes unfolded on the platelet surface when von Willebrand factor binds to the GPIbα subunit of GPIb–IX under shear stress and imposes a pulling force on it.

The unfolding of MSD sets off a complex chain of events and sends an intracellular signal into the platelet that results in rapid platelet clearance.

“Every day, your bone marrow generates more than a billion platelets, and, every day, you clear the same number,” said study author Renhao Li, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“It’s critical that your platelet count stays constant. Too few platelets can lead to . . . thrombocytopenia and may cause spontaneous bleeding or stroke. Thus, identifying the molecular ‘switch’ that triggers platelet clearance is important for designing new therapies to treat thrombocytopenia.”

The mechanism behind MSD-unfolding-induced platelet clearance is still unclear, but Dr Li said this research provides a good starting point for further inquiry into the phenomenon. ![]()

Fungus makes mosquitoes more susceptible to malaria

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have identified a fungus that compromises mosquitoes’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to infection with malaria parasites.

Malaria researchers have, in the past, identified microbes that prevent the Anopheles mosquito from being infected by malaria parasites, but this is the first time they have found a microorganism that appears to make the mosquito more likely to become infected with—and then spread—malaria.

The finding was published in Scientific Reports.

“This very common, naturally occurring fungus may have a significant impact on malaria transmission,” said study author George Dimopoulos, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“It doesn’t kill the mosquitoes. It doesn’t make them sick. It just makes them more likely to become infected and thereby to spread the disease. While this fungus is unlikely to be helpful as part of a malaria control strategy, our finding significantly advances our knowledge of the different factors that influence the transmission of malaria.”

For this study, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues isolated the Penicillium chrysogenum fungus from the gut of field-caught Anopheles mosquitoes. The team found this fungus made the mosquitoes more susceptible to being infected by Plasmodium parasites through a secreted heat-stable factor.

The researchers said the mechanism behind this increased susceptibility involves upregulation of the mosquitoes’ ornithine decarboxylase gene, which sequesters arginine for polyamine biosynthesis.

They noted that arginine plays an important role in the mosquitoes’ anti-Plasmodium defense as a substrate of nitric oxide production, so the availability of arginine has a direct impact on susceptibility to infection with Plasmodium parasites.

Dr Dimopoulos said Penicillium chrysogenum had not previously been studied in terms of mosquito biology, and he and his team had hoped the fungus would act like several other bacteria that researchers have identified, which prevent mosquitoes from becoming infected with malaria parasites.

Even though Penicillium chrysogenum actually appears to worsen infections, the team believes the fungus can still help researchers in their fight against malaria.

“We have questions we hope this finding will help us to answer, including, ‘Why do we have increased transmission of malaria in some areas and not others when the presence of mosquitoes is the same?’” Dr Dimopoulos said. “This gives us another piece of the complicated malaria puzzle.”

Because environmental microorganisms can vary greatly from region to region, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues believe their finding may help explain variations in the prevalence of malaria in different geographic areas. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have identified a fungus that compromises mosquitoes’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to infection with malaria parasites.

Malaria researchers have, in the past, identified microbes that prevent the Anopheles mosquito from being infected by malaria parasites, but this is the first time they have found a microorganism that appears to make the mosquito more likely to become infected with—and then spread—malaria.

The finding was published in Scientific Reports.

“This very common, naturally occurring fungus may have a significant impact on malaria transmission,” said study author George Dimopoulos, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“It doesn’t kill the mosquitoes. It doesn’t make them sick. It just makes them more likely to become infected and thereby to spread the disease. While this fungus is unlikely to be helpful as part of a malaria control strategy, our finding significantly advances our knowledge of the different factors that influence the transmission of malaria.”

For this study, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues isolated the Penicillium chrysogenum fungus from the gut of field-caught Anopheles mosquitoes. The team found this fungus made the mosquitoes more susceptible to being infected by Plasmodium parasites through a secreted heat-stable factor.

The researchers said the mechanism behind this increased susceptibility involves upregulation of the mosquitoes’ ornithine decarboxylase gene, which sequesters arginine for polyamine biosynthesis.

They noted that arginine plays an important role in the mosquitoes’ anti-Plasmodium defense as a substrate of nitric oxide production, so the availability of arginine has a direct impact on susceptibility to infection with Plasmodium parasites.

Dr Dimopoulos said Penicillium chrysogenum had not previously been studied in terms of mosquito biology, and he and his team had hoped the fungus would act like several other bacteria that researchers have identified, which prevent mosquitoes from becoming infected with malaria parasites.

Even though Penicillium chrysogenum actually appears to worsen infections, the team believes the fungus can still help researchers in their fight against malaria.

“We have questions we hope this finding will help us to answer, including, ‘Why do we have increased transmission of malaria in some areas and not others when the presence of mosquitoes is the same?’” Dr Dimopoulos said. “This gives us another piece of the complicated malaria puzzle.”

Because environmental microorganisms can vary greatly from region to region, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues believe their finding may help explain variations in the prevalence of malaria in different geographic areas. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have identified a fungus that compromises mosquitoes’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to infection with malaria parasites.

Malaria researchers have, in the past, identified microbes that prevent the Anopheles mosquito from being infected by malaria parasites, but this is the first time they have found a microorganism that appears to make the mosquito more likely to become infected with—and then spread—malaria.

The finding was published in Scientific Reports.

“This very common, naturally occurring fungus may have a significant impact on malaria transmission,” said study author George Dimopoulos, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“It doesn’t kill the mosquitoes. It doesn’t make them sick. It just makes them more likely to become infected and thereby to spread the disease. While this fungus is unlikely to be helpful as part of a malaria control strategy, our finding significantly advances our knowledge of the different factors that influence the transmission of malaria.”

For this study, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues isolated the Penicillium chrysogenum fungus from the gut of field-caught Anopheles mosquitoes. The team found this fungus made the mosquitoes more susceptible to being infected by Plasmodium parasites through a secreted heat-stable factor.

The researchers said the mechanism behind this increased susceptibility involves upregulation of the mosquitoes’ ornithine decarboxylase gene, which sequesters arginine for polyamine biosynthesis.

They noted that arginine plays an important role in the mosquitoes’ anti-Plasmodium defense as a substrate of nitric oxide production, so the availability of arginine has a direct impact on susceptibility to infection with Plasmodium parasites.

Dr Dimopoulos said Penicillium chrysogenum had not previously been studied in terms of mosquito biology, and he and his team had hoped the fungus would act like several other bacteria that researchers have identified, which prevent mosquitoes from becoming infected with malaria parasites.

Even though Penicillium chrysogenum actually appears to worsen infections, the team believes the fungus can still help researchers in their fight against malaria.

“We have questions we hope this finding will help us to answer, including, ‘Why do we have increased transmission of malaria in some areas and not others when the presence of mosquitoes is the same?’” Dr Dimopoulos said. “This gives us another piece of the complicated malaria puzzle.”

Because environmental microorganisms can vary greatly from region to region, Dr Dimopoulos and his colleagues believe their finding may help explain variations in the prevalence of malaria in different geographic areas. ![]()

Novel Method Reveals New Genetic Information on Depression

In a modern twist on clinical data gathering, crowd-sourcing has helped researchers identify “weak genetic signals” of depression. By combining data from the genetic information website 23andMe.com and previous genetic research, researchers identified for the first time 15 regions of the genome that may be associated with depression in people of European ancestry. Their findings should help “make clear that this is a brain disease,” said Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, a lead investigator and associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, “which we hope will decrease the stigma still associated with these kinds of illnesses.”

Other studies have, of course, investigated genetic components of depression. But they may have been too small to uncover the subtle effects of the many genes influencing the risk of depression, these researchers say.

In their first analysis, using data from > 300,000 people of European ancestry who had purchased genetic profiles on 23andMe.com (and who consented to share their information with researchers), the researchers identified 2 genomic regions significantly associated with depression risk, including 1 previously associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability.

They then combined that information with data from genomewide association studies of 9,200 people with a history of depression and 9,500 controls, along with another group of 151,800 people with and without depression. That analysis revealed 15 genomic regions, including 17 specific sites, significantly associated with a diagnosis of depression. Several of the sites are located in or near genes known to be involved in brain development.

“The neurotransmitter-based models we are currently using to treat depression are more than 40 years old,” says Dr. Perlis. “We really need new treatment targets. We hope that finding these genes will point us toward novel treatment strategies. “[T]he traditional way of doing genetic studies is not the only way that works. Using existing large datasets or biobanks may be far more efficient.”

In a modern twist on clinical data gathering, crowd-sourcing has helped researchers identify “weak genetic signals” of depression. By combining data from the genetic information website 23andMe.com and previous genetic research, researchers identified for the first time 15 regions of the genome that may be associated with depression in people of European ancestry. Their findings should help “make clear that this is a brain disease,” said Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, a lead investigator and associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, “which we hope will decrease the stigma still associated with these kinds of illnesses.”

Other studies have, of course, investigated genetic components of depression. But they may have been too small to uncover the subtle effects of the many genes influencing the risk of depression, these researchers say.

In their first analysis, using data from > 300,000 people of European ancestry who had purchased genetic profiles on 23andMe.com (and who consented to share their information with researchers), the researchers identified 2 genomic regions significantly associated with depression risk, including 1 previously associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability.

They then combined that information with data from genomewide association studies of 9,200 people with a history of depression and 9,500 controls, along with another group of 151,800 people with and without depression. That analysis revealed 15 genomic regions, including 17 specific sites, significantly associated with a diagnosis of depression. Several of the sites are located in or near genes known to be involved in brain development.

“The neurotransmitter-based models we are currently using to treat depression are more than 40 years old,” says Dr. Perlis. “We really need new treatment targets. We hope that finding these genes will point us toward novel treatment strategies. “[T]he traditional way of doing genetic studies is not the only way that works. Using existing large datasets or biobanks may be far more efficient.”

In a modern twist on clinical data gathering, crowd-sourcing has helped researchers identify “weak genetic signals” of depression. By combining data from the genetic information website 23andMe.com and previous genetic research, researchers identified for the first time 15 regions of the genome that may be associated with depression in people of European ancestry. Their findings should help “make clear that this is a brain disease,” said Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, a lead investigator and associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, “which we hope will decrease the stigma still associated with these kinds of illnesses.”

Other studies have, of course, investigated genetic components of depression. But they may have been too small to uncover the subtle effects of the many genes influencing the risk of depression, these researchers say.

In their first analysis, using data from > 300,000 people of European ancestry who had purchased genetic profiles on 23andMe.com (and who consented to share their information with researchers), the researchers identified 2 genomic regions significantly associated with depression risk, including 1 previously associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability.

They then combined that information with data from genomewide association studies of 9,200 people with a history of depression and 9,500 controls, along with another group of 151,800 people with and without depression. That analysis revealed 15 genomic regions, including 17 specific sites, significantly associated with a diagnosis of depression. Several of the sites are located in or near genes known to be involved in brain development.

“The neurotransmitter-based models we are currently using to treat depression are more than 40 years old,” says Dr. Perlis. “We really need new treatment targets. We hope that finding these genes will point us toward novel treatment strategies. “[T]he traditional way of doing genetic studies is not the only way that works. Using existing large datasets or biobanks may be far more efficient.”

Resident SBML for Thoracentesis

There has been a nationwide shift away from general internists performing bedside thoracenteses and toward referring them to pulmonology and interventional radiology services.[1] Aligning with this trend, the American Board of Internal Medicine now only requires that internal medicine (IM)trained physicians understand the indications, complications, and management of bedside procedures.[2]

However, thoracentesis is still considered a core competency of practicing hospitalists, the fastest growing field within general IM.[3] Furthermore, evidence suggests that thoracenteses done by general internists have high patient satisfaction, reduce hospital length of stay, are more cost‐effective, and are as safe as those done by consultants.[4, 5, 6] It is thus important to understand the reasons for referrals to specialty services and to investigate potential interventions that increase performance of procedures by internists.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Barsuk and colleagues present a prospective, single‐center study assessing the impact of simulation‐based mastery learning (SBML) on thoracentesis among a randomly selected group of IM residents.[7] They studied how their program influenced simulated skills, procedural self‐confidence, frequency of real‐world performance, and rate and reasons for referral to consultants. The authors compared the latter outcomes to traditionally trained residents and hospitalists, finding that SBML improved skills, self‐confidence, and the relative frequency of general internistperformed procedures. Low confidence and limited time were the primary reasons for referral.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that SBML can lead to a clinically and statistically significant change in thoracentesis referral patterns, which may have important implications for hospitalists. Given the inconsistent amount and quality of procedural training across IM residency programs, hospitalists may be increasingly ill prepared to perform thoracentesis and train future generations in its best practices.[2, 8, 9] This study demonstrates that SBML can provide trainees with essential hands‐on skills development and experience that is often missing from traditional training models.

Yet, although SBML seems to affect resident referral patterns, its potential impact on practicing hospitalists is less clear. Hospitalists provide the majority of care for general medicine inpatients around the country, and in this study had a dramatically lower rate of bedside procedure performance than even traditionally trained residents (0.7% vs 14.2$), which makes them vital to any strategy to increase bedside thoracentesis rates.[9] Yet the results by Barsuk et al. suggest that the effect size of SBML on hospitalists may be much smaller than on trainees. First, the primary driver of resident practice change appeared to be increased confidence, but baseline hospitalist confidence was significantly greater than that of traditionally trained residents. Second, it is unclear what, if any, effect SBML would have on the time needed to perform a thoracentesis, which was a major factor for hospitalists referring to consult services. Lastly, given the known decrement in procedural skills over time, the durability and associated costs of longitudinal SBML training are unknown.[10, 11, 12]

The fact that general internistperformed thoracenteses are as safe and more cost‐effective than those performed by consultants is a compelling argument to shift procedures back to the bedside. However, these cost analyses do not account for the opportunity cost for hospitalists, either in lost time spent caring for additional patients or in longer shift lengths. It is important to understand whether and how it can be feasible for general internists to perform more bedside thoracenteses so physician training and resource utilization can be optimized. Whereas confidence and time are likely limiting factors for all general internists, this study suggests that their relative importance may markedly differ between residents and hospitalists, and it is unclear how much the change in confidence resulting from SBML would affect the rates of thoracentesis by generalists beyond practice settings involving trainees. The feasibility, cost, and efficacy of SBML deserve more study in multiple clinical environments to understand its true impact. Ultimately, we suspect that only an intervention addressing procedural time demands will lead to meaningful, sustained increases in general internistperformed thoracenteses.

- , . The declining number and variety of procedures done by general internists: a resurvey of members of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):355–360.

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Internal medicine policies. Available at: http://www.abim.org/certification/policies/internal‐medicine‐subspecialty‐policies/internal‐medicine.aspx. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. SHM core competencies. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Education/Core_Competencies/Web/Education/Core_Competencies.aspx. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- , , , . Patient satisfaction with a hospitalist procedure service: is bedside procedure teaching reassuring to patients? J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):219–224.

- , , , , . Factors associated with inpatient thoracentesis procedure quality at university hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(1):34–40.

- , , , , . Thoracentesis outcomes: a 12‐year experience. Thorax. 2015;70(2):127–132.

- , , , et al. The effect of simulation‐based mastery learning on thoracentesis referral patterns. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):792–795.

- . What we know about hospitalists. Innovative Thinking website. Available at: http://innovativesolutions.org/innovative‐thinking/what‐we‐know‐about‐hospitalists. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- , , , . Procedural skills training in internal medicine residencies. A survey of program directors. Ann intern Med. 1989;111(11):932–938.

- , , , et al. Beyond the comfort zone: residents assess their comfort performing inpatient medical procedures. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71:e17–e24.

- . Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 suppl):S70–S81

- , , , et al. Simulation training and its effect on long‐term resident performance in central venous catheterization. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(3):146–151.

There has been a nationwide shift away from general internists performing bedside thoracenteses and toward referring them to pulmonology and interventional radiology services.[1] Aligning with this trend, the American Board of Internal Medicine now only requires that internal medicine (IM)trained physicians understand the indications, complications, and management of bedside procedures.[2]

However, thoracentesis is still considered a core competency of practicing hospitalists, the fastest growing field within general IM.[3] Furthermore, evidence suggests that thoracenteses done by general internists have high patient satisfaction, reduce hospital length of stay, are more cost‐effective, and are as safe as those done by consultants.[4, 5, 6] It is thus important to understand the reasons for referrals to specialty services and to investigate potential interventions that increase performance of procedures by internists.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Barsuk and colleagues present a prospective, single‐center study assessing the impact of simulation‐based mastery learning (SBML) on thoracentesis among a randomly selected group of IM residents.[7] They studied how their program influenced simulated skills, procedural self‐confidence, frequency of real‐world performance, and rate and reasons for referral to consultants. The authors compared the latter outcomes to traditionally trained residents and hospitalists, finding that SBML improved skills, self‐confidence, and the relative frequency of general internistperformed procedures. Low confidence and limited time were the primary reasons for referral.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that SBML can lead to a clinically and statistically significant change in thoracentesis referral patterns, which may have important implications for hospitalists. Given the inconsistent amount and quality of procedural training across IM residency programs, hospitalists may be increasingly ill prepared to perform thoracentesis and train future generations in its best practices.[2, 8, 9] This study demonstrates that SBML can provide trainees with essential hands‐on skills development and experience that is often missing from traditional training models.

Yet, although SBML seems to affect resident referral patterns, its potential impact on practicing hospitalists is less clear. Hospitalists provide the majority of care for general medicine inpatients around the country, and in this study had a dramatically lower rate of bedside procedure performance than even traditionally trained residents (0.7% vs 14.2$), which makes them vital to any strategy to increase bedside thoracentesis rates.[9] Yet the results by Barsuk et al. suggest that the effect size of SBML on hospitalists may be much smaller than on trainees. First, the primary driver of resident practice change appeared to be increased confidence, but baseline hospitalist confidence was significantly greater than that of traditionally trained residents. Second, it is unclear what, if any, effect SBML would have on the time needed to perform a thoracentesis, which was a major factor for hospitalists referring to consult services. Lastly, given the known decrement in procedural skills over time, the durability and associated costs of longitudinal SBML training are unknown.[10, 11, 12]

The fact that general internistperformed thoracenteses are as safe and more cost‐effective than those performed by consultants is a compelling argument to shift procedures back to the bedside. However, these cost analyses do not account for the opportunity cost for hospitalists, either in lost time spent caring for additional patients or in longer shift lengths. It is important to understand whether and how it can be feasible for general internists to perform more bedside thoracenteses so physician training and resource utilization can be optimized. Whereas confidence and time are likely limiting factors for all general internists, this study suggests that their relative importance may markedly differ between residents and hospitalists, and it is unclear how much the change in confidence resulting from SBML would affect the rates of thoracentesis by generalists beyond practice settings involving trainees. The feasibility, cost, and efficacy of SBML deserve more study in multiple clinical environments to understand its true impact. Ultimately, we suspect that only an intervention addressing procedural time demands will lead to meaningful, sustained increases in general internistperformed thoracenteses.

There has been a nationwide shift away from general internists performing bedside thoracenteses and toward referring them to pulmonology and interventional radiology services.[1] Aligning with this trend, the American Board of Internal Medicine now only requires that internal medicine (IM)trained physicians understand the indications, complications, and management of bedside procedures.[2]

However, thoracentesis is still considered a core competency of practicing hospitalists, the fastest growing field within general IM.[3] Furthermore, evidence suggests that thoracenteses done by general internists have high patient satisfaction, reduce hospital length of stay, are more cost‐effective, and are as safe as those done by consultants.[4, 5, 6] It is thus important to understand the reasons for referrals to specialty services and to investigate potential interventions that increase performance of procedures by internists.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Barsuk and colleagues present a prospective, single‐center study assessing the impact of simulation‐based mastery learning (SBML) on thoracentesis among a randomly selected group of IM residents.[7] They studied how their program influenced simulated skills, procedural self‐confidence, frequency of real‐world performance, and rate and reasons for referral to consultants. The authors compared the latter outcomes to traditionally trained residents and hospitalists, finding that SBML improved skills, self‐confidence, and the relative frequency of general internistperformed procedures. Low confidence and limited time were the primary reasons for referral.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that SBML can lead to a clinically and statistically significant change in thoracentesis referral patterns, which may have important implications for hospitalists. Given the inconsistent amount and quality of procedural training across IM residency programs, hospitalists may be increasingly ill prepared to perform thoracentesis and train future generations in its best practices.[2, 8, 9] This study demonstrates that SBML can provide trainees with essential hands‐on skills development and experience that is often missing from traditional training models.

Yet, although SBML seems to affect resident referral patterns, its potential impact on practicing hospitalists is less clear. Hospitalists provide the majority of care for general medicine inpatients around the country, and in this study had a dramatically lower rate of bedside procedure performance than even traditionally trained residents (0.7% vs 14.2$), which makes them vital to any strategy to increase bedside thoracentesis rates.[9] Yet the results by Barsuk et al. suggest that the effect size of SBML on hospitalists may be much smaller than on trainees. First, the primary driver of resident practice change appeared to be increased confidence, but baseline hospitalist confidence was significantly greater than that of traditionally trained residents. Second, it is unclear what, if any, effect SBML would have on the time needed to perform a thoracentesis, which was a major factor for hospitalists referring to consult services. Lastly, given the known decrement in procedural skills over time, the durability and associated costs of longitudinal SBML training are unknown.[10, 11, 12]