User login

AATS Mitral Conclave Call for Abstracts & Videos

AATS welcomes you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

AATS welcomes you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

AATS welcomes you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

The choice in November could not be more important

Editor’s note: For the last five presidential elections, this news organization has offered the Republican and Democrat presidential candidate the opportunity to present their ideas directly to U.S. physicians via side-by-side Guest Editorials. The candidates – or their proxies – have used these pages to reach out to you, our readers, with their views on medicine, health care, and other issues. We have taken pride in the ability to offer you a balanced view in the weeks leading up to the general election. This year, we cannot provide you with that balanced view. Despite repeated efforts via every medium at our disposal – telephone calls, emails, Twitter, LinkedIn, and more – the Donald J. Trump for President organization has not responded to our request for a contribution. Here we present the contribution from Secretary Hillary Clinton’s proxy.

Guest Editorial

As physicians, we have the unique privilege of serving patients, often at their most vulnerable moments. We also bear witness to how our health care system works – and too often, where it falls short – through our patients’ eyes.

That view could change dramatically depending on the outcome of this year’s presidential election. Hillary Clinton has a long track record of expanding affordable health care, and wants to accelerate the march toward universal access to high-quality care. Her opponent, Donald Trump, wants to roll back the progress we’ve made, with a plan that takes health insurance away from more than 20 million Americans.

Secretary Clinton’s career demonstrates her commitment to the ideal of health care as a human right. For example, she was instrumental in the bipartisan effort to pass the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Despite recent gains in health coverage, too many Americans still struggle to access the care they need – where and when they need it. Secretary Clinton’s plan for health care would expand access to care by building on the Affordable Care Act – with more relief for high premiums and out-of-pocket costs, particularly for prescription drugs; by working with states to expand Medicaid and give people the choice of a “public option” health plan. She also worked with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) on a plan to double funding for community health centers and substantially expand our commitment to the National Health Service Corps – so that millions more Americans have access to primary care, especially in rural and medically underserved urban areas, and so that we can offer more loan repayment and scholarships to early-career physicians.

Anyone taking care of patients today knows that improving access to care is only the first step. We must improve the way we deliver care, refocusing around the patient-doctor relationship. Too often there are barriers – regulations, paperwork, or insurance restrictions – to taking care of patients in the way that they deserve. Secretary Clinton wants to ensure an advanced and coordinated health care system that supports patient-doctor relationships instead of getting in the way. She wants to spur delivery system reform to reward value and quality. She was one of the first elected officials to call for modernizing health information technology, reaching across the aisle to work with physician and then-Sen. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.). And she’s offered plans to address major contemporary challenges, such as preventing and better treating Alzheimer’s disease, destigmatizing mental illness, and improving care for substance use disorders.

In addition to improving our health care system, Secretary Clinton believes we must take a number of proactive steps so that all Americans – regardless of location, income, or history – have the opportunity to live full, healthy lives. She believes we must invest in our public health infrastructure to ensure preparedness for emerging threats like Zika at home and abroad; to prevent illness and injury in communities; and to promote health equity. Of course, some of the most important determinants of well-being lie outside the walls of our clinics and hospitals. Secretary Clinton also will move us forward on these fundamental issues, such as women’s rights, criminal justice reform, and climate change.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump offers a very different vision for health care in the United States. His proposals would repeal the Affordable Care Act, instantly stripping millions of people of lifesaving health insurance. He would cut Medicaid through block grants, leaving millions of the poorest Americans without a safety net. And he would once again allow insurers to discriminate, based on preexisting conditions.

The choice in November could not be more important, for our patients and for the practice of medicine. Secretary Clinton’s long track record of fighting for universal, high-quality, affordable health care speaks for itself. With so much more left to do to improve health in our country, she brings the thoughtful leadership and steely determination needed to get the job done.

Dr. Chokshi practices internal medicine at Bellevue Hospital in New York and is a health policy adviser to Hillary for America.

Editor’s note: For the last five presidential elections, this news organization has offered the Republican and Democrat presidential candidate the opportunity to present their ideas directly to U.S. physicians via side-by-side Guest Editorials. The candidates – or their proxies – have used these pages to reach out to you, our readers, with their views on medicine, health care, and other issues. We have taken pride in the ability to offer you a balanced view in the weeks leading up to the general election. This year, we cannot provide you with that balanced view. Despite repeated efforts via every medium at our disposal – telephone calls, emails, Twitter, LinkedIn, and more – the Donald J. Trump for President organization has not responded to our request for a contribution. Here we present the contribution from Secretary Hillary Clinton’s proxy.

Guest Editorial

As physicians, we have the unique privilege of serving patients, often at their most vulnerable moments. We also bear witness to how our health care system works – and too often, where it falls short – through our patients’ eyes.

That view could change dramatically depending on the outcome of this year’s presidential election. Hillary Clinton has a long track record of expanding affordable health care, and wants to accelerate the march toward universal access to high-quality care. Her opponent, Donald Trump, wants to roll back the progress we’ve made, with a plan that takes health insurance away from more than 20 million Americans.

Secretary Clinton’s career demonstrates her commitment to the ideal of health care as a human right. For example, she was instrumental in the bipartisan effort to pass the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Despite recent gains in health coverage, too many Americans still struggle to access the care they need – where and when they need it. Secretary Clinton’s plan for health care would expand access to care by building on the Affordable Care Act – with more relief for high premiums and out-of-pocket costs, particularly for prescription drugs; by working with states to expand Medicaid and give people the choice of a “public option” health plan. She also worked with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) on a plan to double funding for community health centers and substantially expand our commitment to the National Health Service Corps – so that millions more Americans have access to primary care, especially in rural and medically underserved urban areas, and so that we can offer more loan repayment and scholarships to early-career physicians.

Anyone taking care of patients today knows that improving access to care is only the first step. We must improve the way we deliver care, refocusing around the patient-doctor relationship. Too often there are barriers – regulations, paperwork, or insurance restrictions – to taking care of patients in the way that they deserve. Secretary Clinton wants to ensure an advanced and coordinated health care system that supports patient-doctor relationships instead of getting in the way. She wants to spur delivery system reform to reward value and quality. She was one of the first elected officials to call for modernizing health information technology, reaching across the aisle to work with physician and then-Sen. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.). And she’s offered plans to address major contemporary challenges, such as preventing and better treating Alzheimer’s disease, destigmatizing mental illness, and improving care for substance use disorders.

In addition to improving our health care system, Secretary Clinton believes we must take a number of proactive steps so that all Americans – regardless of location, income, or history – have the opportunity to live full, healthy lives. She believes we must invest in our public health infrastructure to ensure preparedness for emerging threats like Zika at home and abroad; to prevent illness and injury in communities; and to promote health equity. Of course, some of the most important determinants of well-being lie outside the walls of our clinics and hospitals. Secretary Clinton also will move us forward on these fundamental issues, such as women’s rights, criminal justice reform, and climate change.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump offers a very different vision for health care in the United States. His proposals would repeal the Affordable Care Act, instantly stripping millions of people of lifesaving health insurance. He would cut Medicaid through block grants, leaving millions of the poorest Americans without a safety net. And he would once again allow insurers to discriminate, based on preexisting conditions.

The choice in November could not be more important, for our patients and for the practice of medicine. Secretary Clinton’s long track record of fighting for universal, high-quality, affordable health care speaks for itself. With so much more left to do to improve health in our country, she brings the thoughtful leadership and steely determination needed to get the job done.

Dr. Chokshi practices internal medicine at Bellevue Hospital in New York and is a health policy adviser to Hillary for America.

Editor’s note: For the last five presidential elections, this news organization has offered the Republican and Democrat presidential candidate the opportunity to present their ideas directly to U.S. physicians via side-by-side Guest Editorials. The candidates – or their proxies – have used these pages to reach out to you, our readers, with their views on medicine, health care, and other issues. We have taken pride in the ability to offer you a balanced view in the weeks leading up to the general election. This year, we cannot provide you with that balanced view. Despite repeated efforts via every medium at our disposal – telephone calls, emails, Twitter, LinkedIn, and more – the Donald J. Trump for President organization has not responded to our request for a contribution. Here we present the contribution from Secretary Hillary Clinton’s proxy.

Guest Editorial

As physicians, we have the unique privilege of serving patients, often at their most vulnerable moments. We also bear witness to how our health care system works – and too often, where it falls short – through our patients’ eyes.

That view could change dramatically depending on the outcome of this year’s presidential election. Hillary Clinton has a long track record of expanding affordable health care, and wants to accelerate the march toward universal access to high-quality care. Her opponent, Donald Trump, wants to roll back the progress we’ve made, with a plan that takes health insurance away from more than 20 million Americans.

Secretary Clinton’s career demonstrates her commitment to the ideal of health care as a human right. For example, she was instrumental in the bipartisan effort to pass the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Despite recent gains in health coverage, too many Americans still struggle to access the care they need – where and when they need it. Secretary Clinton’s plan for health care would expand access to care by building on the Affordable Care Act – with more relief for high premiums and out-of-pocket costs, particularly for prescription drugs; by working with states to expand Medicaid and give people the choice of a “public option” health plan. She also worked with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) on a plan to double funding for community health centers and substantially expand our commitment to the National Health Service Corps – so that millions more Americans have access to primary care, especially in rural and medically underserved urban areas, and so that we can offer more loan repayment and scholarships to early-career physicians.

Anyone taking care of patients today knows that improving access to care is only the first step. We must improve the way we deliver care, refocusing around the patient-doctor relationship. Too often there are barriers – regulations, paperwork, or insurance restrictions – to taking care of patients in the way that they deserve. Secretary Clinton wants to ensure an advanced and coordinated health care system that supports patient-doctor relationships instead of getting in the way. She wants to spur delivery system reform to reward value and quality. She was one of the first elected officials to call for modernizing health information technology, reaching across the aisle to work with physician and then-Sen. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.). And she’s offered plans to address major contemporary challenges, such as preventing and better treating Alzheimer’s disease, destigmatizing mental illness, and improving care for substance use disorders.

In addition to improving our health care system, Secretary Clinton believes we must take a number of proactive steps so that all Americans – regardless of location, income, or history – have the opportunity to live full, healthy lives. She believes we must invest in our public health infrastructure to ensure preparedness for emerging threats like Zika at home and abroad; to prevent illness and injury in communities; and to promote health equity. Of course, some of the most important determinants of well-being lie outside the walls of our clinics and hospitals. Secretary Clinton also will move us forward on these fundamental issues, such as women’s rights, criminal justice reform, and climate change.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump offers a very different vision for health care in the United States. His proposals would repeal the Affordable Care Act, instantly stripping millions of people of lifesaving health insurance. He would cut Medicaid through block grants, leaving millions of the poorest Americans without a safety net. And he would once again allow insurers to discriminate, based on preexisting conditions.

The choice in November could not be more important, for our patients and for the practice of medicine. Secretary Clinton’s long track record of fighting for universal, high-quality, affordable health care speaks for itself. With so much more left to do to improve health in our country, she brings the thoughtful leadership and steely determination needed to get the job done.

Dr. Chokshi practices internal medicine at Bellevue Hospital in New York and is a health policy adviser to Hillary for America.

Applications Open for AATS Leadership Academy

Current and future CT surgery division chiefs/department chairs are invited to apply for the AATS Leadership Academy Program.

Friday, April 28, 2017

AATS Centennial

Boston, MA

This intensive, didactic and interactive program brings together up to 20 international surgeons who have demonstrated significant promise as potential future division chiefs or have recent assumed that role. The program provides participants with administrative, interpersonal, mentoring and negotiating skills, as well as the opportunity to network with well-known thoracic surgeon leaders and potential mentors.

Deadline: November 30, 2016

Current and future CT surgery division chiefs/department chairs are invited to apply for the AATS Leadership Academy Program.

Friday, April 28, 2017

AATS Centennial

Boston, MA

This intensive, didactic and interactive program brings together up to 20 international surgeons who have demonstrated significant promise as potential future division chiefs or have recent assumed that role. The program provides participants with administrative, interpersonal, mentoring and negotiating skills, as well as the opportunity to network with well-known thoracic surgeon leaders and potential mentors.

Deadline: November 30, 2016

Current and future CT surgery division chiefs/department chairs are invited to apply for the AATS Leadership Academy Program.

Friday, April 28, 2017

AATS Centennial

Boston, MA

This intensive, didactic and interactive program brings together up to 20 international surgeons who have demonstrated significant promise as potential future division chiefs or have recent assumed that role. The program provides participants with administrative, interpersonal, mentoring and negotiating skills, as well as the opportunity to network with well-known thoracic surgeon leaders and potential mentors.

Deadline: November 30, 2016

Nonsexual secondary Zika virus case confirmed in Utah

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Rise in HPV vaccination spurs CIN drop

As human papillomavirus vaccination rates climbed in New Mexico, all grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia declined in females aged 15-19 years, and grade 2 neoplasia fell among those who were aged 20-24 years, according to an analysis published online Sept. 29 in JAMA Oncology.

In the 15- to 19-year-old group, the annual incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1 dropped from 3,468 cases per 100,000 individuals screened in 2007 to 1,591 in 2014, an annual percentage change (APC) of –9.0.

CIN2 cases fell from 896 to 415 (APC, –10.5), and CIN3 from 240 to 0 (APC, –41.3). Among women aged 20-24 years, CIN2 annual incidence fell from 1,028 to 627 cases per 100,000 women screened (APC, –6.3).

The reductions were greater than expected, given that only 40% of females aged 13-17 years had received all three doses in 2014, up from 17% in 2008. It’s likely that herd immunity, benefit from even partial vaccination, and cross-protection against HPV strains not in vaccines contributed to the success, reported Vicki B. Benard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Sept. 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609).

The investigators adjusted their findings to account for trends towards longer intervals between cervical screenings and later initiation of screening. Otherwise, the effect of the vaccine would have been overestimated.

The ultimate goal “is a rational integration of HPV vaccination and cervical screening,” they wrote. Current cervical cancer screening guidelines do not differentiate between women who have been vaccinated and those who have not, but this should be reevaluated in light of the study findings, the researchers noted.

“Our data demonstrate that clinical outcomes of CIN will be reduced among cohorts [even] partially vaccinated for HPV,” which will reduce the cost-effectiveness of screening. “A later starting age for cervical screening among partially vaccinated populations of young women ... may be prudent given the already infrequent incidence of invasive cervical cancer for women younger than 25 years” even before the HPV vaccine was introduced in 2007, the investigators wrote.

The study focuses on data from New Mexico because it is the only state that has captured population-based estimates of both screening prevalence and CIN since the introduction of the vaccine.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the work. Dr. Benard reported having no financial disclosures, but other investigators reported ties with HPV vaccine makers Merck and GSK, among other companies.

As human papillomavirus vaccination rates climbed in New Mexico, all grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia declined in females aged 15-19 years, and grade 2 neoplasia fell among those who were aged 20-24 years, according to an analysis published online Sept. 29 in JAMA Oncology.

In the 15- to 19-year-old group, the annual incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1 dropped from 3,468 cases per 100,000 individuals screened in 2007 to 1,591 in 2014, an annual percentage change (APC) of –9.0.

CIN2 cases fell from 896 to 415 (APC, –10.5), and CIN3 from 240 to 0 (APC, –41.3). Among women aged 20-24 years, CIN2 annual incidence fell from 1,028 to 627 cases per 100,000 women screened (APC, –6.3).

The reductions were greater than expected, given that only 40% of females aged 13-17 years had received all three doses in 2014, up from 17% in 2008. It’s likely that herd immunity, benefit from even partial vaccination, and cross-protection against HPV strains not in vaccines contributed to the success, reported Vicki B. Benard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Sept. 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609).

The investigators adjusted their findings to account for trends towards longer intervals between cervical screenings and later initiation of screening. Otherwise, the effect of the vaccine would have been overestimated.

The ultimate goal “is a rational integration of HPV vaccination and cervical screening,” they wrote. Current cervical cancer screening guidelines do not differentiate between women who have been vaccinated and those who have not, but this should be reevaluated in light of the study findings, the researchers noted.

“Our data demonstrate that clinical outcomes of CIN will be reduced among cohorts [even] partially vaccinated for HPV,” which will reduce the cost-effectiveness of screening. “A later starting age for cervical screening among partially vaccinated populations of young women ... may be prudent given the already infrequent incidence of invasive cervical cancer for women younger than 25 years” even before the HPV vaccine was introduced in 2007, the investigators wrote.

The study focuses on data from New Mexico because it is the only state that has captured population-based estimates of both screening prevalence and CIN since the introduction of the vaccine.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the work. Dr. Benard reported having no financial disclosures, but other investigators reported ties with HPV vaccine makers Merck and GSK, among other companies.

As human papillomavirus vaccination rates climbed in New Mexico, all grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia declined in females aged 15-19 years, and grade 2 neoplasia fell among those who were aged 20-24 years, according to an analysis published online Sept. 29 in JAMA Oncology.

In the 15- to 19-year-old group, the annual incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1 dropped from 3,468 cases per 100,000 individuals screened in 2007 to 1,591 in 2014, an annual percentage change (APC) of –9.0.

CIN2 cases fell from 896 to 415 (APC, –10.5), and CIN3 from 240 to 0 (APC, –41.3). Among women aged 20-24 years, CIN2 annual incidence fell from 1,028 to 627 cases per 100,000 women screened (APC, –6.3).

The reductions were greater than expected, given that only 40% of females aged 13-17 years had received all three doses in 2014, up from 17% in 2008. It’s likely that herd immunity, benefit from even partial vaccination, and cross-protection against HPV strains not in vaccines contributed to the success, reported Vicki B. Benard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Sept. 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609).

The investigators adjusted their findings to account for trends towards longer intervals between cervical screenings and later initiation of screening. Otherwise, the effect of the vaccine would have been overestimated.

The ultimate goal “is a rational integration of HPV vaccination and cervical screening,” they wrote. Current cervical cancer screening guidelines do not differentiate between women who have been vaccinated and those who have not, but this should be reevaluated in light of the study findings, the researchers noted.

“Our data demonstrate that clinical outcomes of CIN will be reduced among cohorts [even] partially vaccinated for HPV,” which will reduce the cost-effectiveness of screening. “A later starting age for cervical screening among partially vaccinated populations of young women ... may be prudent given the already infrequent incidence of invasive cervical cancer for women younger than 25 years” even before the HPV vaccine was introduced in 2007, the investigators wrote.

The study focuses on data from New Mexico because it is the only state that has captured population-based estimates of both screening prevalence and CIN since the introduction of the vaccine.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the work. Dr. Benard reported having no financial disclosures, but other investigators reported ties with HPV vaccine makers Merck and GSK, among other companies.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Future cervical cancer screening guidelines may need to differentiate between those who have been vaccinated against HPV and those who have not.

Major finding: As HPV vaccination rates increased in New Mexico, the annual incidence of CIN1 among 15- to 19-year-old females dropped from 3,468 cases per 100,000 individuals screened in 2007 to 1,591 in 2014, an annual percentage change of –9.0.

Data source: An analysis of the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry of 2007-2014.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the work. The lead investigator had no financial disclosures, but others reported ties with HPV vaccine makers Merck and GSK, among other companies.

A different Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is at least one time when families sit down and focus on the meal. While the turkey may be the centerpiece, at least in our family we are presented with a variety of vegetables, salads, baked goods, and desserts. Some of the dishes remain on the traditional menu because “Aunt Martha always brings her molded salad,” although if the truth be known, she had fallen out of love with making it years ago. Other selections survive as memorials to long-departed family members: “Remember how much Grampy Stevens loved that pickled watermelon rind” that no one has touched since he died 10 years ago?

And although Thanksgiving may be all about the food, it’s really about sitting down together and celebrating each other over a meal. It should really be a happy meal but not one that comes in a box with a plastic toy. But for the parents of a picky eater, Thanksgiving is often destined to be another stressful dining experience. They know that despite the bountiful spread of food, there isn’t going to be anything on the table their child is going to eat.

They can cope with the situation in one of two ways. They can bring something they know he will eat, such as a can of corn or a microwaveable macaroni and cheese so he won’t “starve.” Or they can cast a pall on the festivities by attempting to badger, coax, and coerce him to eat something, as they do every night at home.

Parents may be assisted in their efforts by other family members who will bring something from the picky eater’s “might eat list.” Or, more likely, they will join in a chorus of old favorites such as “Don’t you want to grow up to be big and strong?” Or “You won’t be able to have any of Grandma’s cookies if you don’t eat some dinner.”

Either approach will be another step toward solidifying the child’s reputation in the family as a picky eater. Rachel is the cousin who plays the piano, and everyone knows that Brandon is going to be a great soccer player. Bobby is the one who won’t eat anything but mac and cheese.

A few years ago I had the thought that instead of allowing Thanksgiving to become an event that highlights and perpetuates the picky eater’s unfortunate habits, why not use the holiday as an opportunity to turn the page and begin a more sensible approach to selective eating?

So for some parents of picky eaters, I have begun to recommend the following: Tell everyone who will be coming to Thanksgiving that the pediatrician says everyone should agree that the event will be all about having a good time and not about who eats or doesn’t eat what’s on the table. And there will be no discussion about the picky eater’s habits – positive or negative.

It might be nice to include on the menu a dish or dessert that the picky eater has eaten in the past. But this is done without ceremony, comment, or preconditions such as “You have to eat some of this to get that.” This silent gesture of kindness also may reassure nervous grandparents who are worried that the child will starve if he doesn’t eat anything for a day despite your reassurance to them that the pediatrician said it was okay.

While I admit that one Thanksgiving with these new rules is unlikely to convert a 6-year-old picky eater into a voracious omnivore, it can be a first step toward helping a family adopt a sensible approach to the child’s eating habits. At least it won’t make things worse and is likely to turn unhappy meals at home into mini feasts that celebrate togetherness.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Thanksgiving is at least one time when families sit down and focus on the meal. While the turkey may be the centerpiece, at least in our family we are presented with a variety of vegetables, salads, baked goods, and desserts. Some of the dishes remain on the traditional menu because “Aunt Martha always brings her molded salad,” although if the truth be known, she had fallen out of love with making it years ago. Other selections survive as memorials to long-departed family members: “Remember how much Grampy Stevens loved that pickled watermelon rind” that no one has touched since he died 10 years ago?

And although Thanksgiving may be all about the food, it’s really about sitting down together and celebrating each other over a meal. It should really be a happy meal but not one that comes in a box with a plastic toy. But for the parents of a picky eater, Thanksgiving is often destined to be another stressful dining experience. They know that despite the bountiful spread of food, there isn’t going to be anything on the table their child is going to eat.

They can cope with the situation in one of two ways. They can bring something they know he will eat, such as a can of corn or a microwaveable macaroni and cheese so he won’t “starve.” Or they can cast a pall on the festivities by attempting to badger, coax, and coerce him to eat something, as they do every night at home.

Parents may be assisted in their efforts by other family members who will bring something from the picky eater’s “might eat list.” Or, more likely, they will join in a chorus of old favorites such as “Don’t you want to grow up to be big and strong?” Or “You won’t be able to have any of Grandma’s cookies if you don’t eat some dinner.”

Either approach will be another step toward solidifying the child’s reputation in the family as a picky eater. Rachel is the cousin who plays the piano, and everyone knows that Brandon is going to be a great soccer player. Bobby is the one who won’t eat anything but mac and cheese.

A few years ago I had the thought that instead of allowing Thanksgiving to become an event that highlights and perpetuates the picky eater’s unfortunate habits, why not use the holiday as an opportunity to turn the page and begin a more sensible approach to selective eating?

So for some parents of picky eaters, I have begun to recommend the following: Tell everyone who will be coming to Thanksgiving that the pediatrician says everyone should agree that the event will be all about having a good time and not about who eats or doesn’t eat what’s on the table. And there will be no discussion about the picky eater’s habits – positive or negative.

It might be nice to include on the menu a dish or dessert that the picky eater has eaten in the past. But this is done without ceremony, comment, or preconditions such as “You have to eat some of this to get that.” This silent gesture of kindness also may reassure nervous grandparents who are worried that the child will starve if he doesn’t eat anything for a day despite your reassurance to them that the pediatrician said it was okay.

While I admit that one Thanksgiving with these new rules is unlikely to convert a 6-year-old picky eater into a voracious omnivore, it can be a first step toward helping a family adopt a sensible approach to the child’s eating habits. At least it won’t make things worse and is likely to turn unhappy meals at home into mini feasts that celebrate togetherness.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Thanksgiving is at least one time when families sit down and focus on the meal. While the turkey may be the centerpiece, at least in our family we are presented with a variety of vegetables, salads, baked goods, and desserts. Some of the dishes remain on the traditional menu because “Aunt Martha always brings her molded salad,” although if the truth be known, she had fallen out of love with making it years ago. Other selections survive as memorials to long-departed family members: “Remember how much Grampy Stevens loved that pickled watermelon rind” that no one has touched since he died 10 years ago?

And although Thanksgiving may be all about the food, it’s really about sitting down together and celebrating each other over a meal. It should really be a happy meal but not one that comes in a box with a plastic toy. But for the parents of a picky eater, Thanksgiving is often destined to be another stressful dining experience. They know that despite the bountiful spread of food, there isn’t going to be anything on the table their child is going to eat.

They can cope with the situation in one of two ways. They can bring something they know he will eat, such as a can of corn or a microwaveable macaroni and cheese so he won’t “starve.” Or they can cast a pall on the festivities by attempting to badger, coax, and coerce him to eat something, as they do every night at home.

Parents may be assisted in their efforts by other family members who will bring something from the picky eater’s “might eat list.” Or, more likely, they will join in a chorus of old favorites such as “Don’t you want to grow up to be big and strong?” Or “You won’t be able to have any of Grandma’s cookies if you don’t eat some dinner.”

Either approach will be another step toward solidifying the child’s reputation in the family as a picky eater. Rachel is the cousin who plays the piano, and everyone knows that Brandon is going to be a great soccer player. Bobby is the one who won’t eat anything but mac and cheese.

A few years ago I had the thought that instead of allowing Thanksgiving to become an event that highlights and perpetuates the picky eater’s unfortunate habits, why not use the holiday as an opportunity to turn the page and begin a more sensible approach to selective eating?

So for some parents of picky eaters, I have begun to recommend the following: Tell everyone who will be coming to Thanksgiving that the pediatrician says everyone should agree that the event will be all about having a good time and not about who eats or doesn’t eat what’s on the table. And there will be no discussion about the picky eater’s habits – positive or negative.

It might be nice to include on the menu a dish or dessert that the picky eater has eaten in the past. But this is done without ceremony, comment, or preconditions such as “You have to eat some of this to get that.” This silent gesture of kindness also may reassure nervous grandparents who are worried that the child will starve if he doesn’t eat anything for a day despite your reassurance to them that the pediatrician said it was okay.

While I admit that one Thanksgiving with these new rules is unlikely to convert a 6-year-old picky eater into a voracious omnivore, it can be a first step toward helping a family adopt a sensible approach to the child’s eating habits. At least it won’t make things worse and is likely to turn unhappy meals at home into mini feasts that celebrate togetherness.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Experts attempt first treat-to-target recommendations in gout

The first treat-to-target recommendations for gout emphasize keeping serum uric acid levels below 6 mg/dL (less than 360 mmol/L), but base this and other guidance on expert opinion because no published trials have compared gout treatments head to head.

“[We] considered dissolution of crystals and prevention of flares to be fundamental; patient education, ensuring adherence to medications, and monitoring serum urate levels were also considered to be of major importance,” wrote Uta Kiltz, MD, of Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet and Ruhr University Bochum in Herne, Germany, and her coauthors (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-20946).

Treating to a therapeutic target is becoming the norm in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. But despite some recent progress in gout – including updated recommendations (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jul 25 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707) and Food and Drug Administration approval of the first selective urate transporter inhibitor – it is lagging behind, said Kenneth Saag, MD, a guideline coauthor and rheumatologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“This is partly because gout has been a dramatically understudied disease,” Dr. Saag said in an interview. Indeed, although it affects at least 8 million people in the United States, is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in men, and is rising in prevalence with population aging and the obesity epidemic, gout has received much less research funding than rheumatoid arthritis, he noted.

Gout’s insidious nature may be one reason. “Gout affects people in an intermittent way before it becomes a chronic arthritis, and during that initial phase, it is not viewed by many as more than a nuisance,” Dr. Saag said. “The challenge is that gout really is a disease that ultimately causes a lot of morbidity. If serum urate levels are not controlled, hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease can all accompany gout.”

Accordingly, the No. 1 goal in gout is to meet the serum urate target, and it “doesn’t really matter” what clinicians use to get there, Dr. Saag said. Both allopurinol and febuxostat can effectively lower serum uric acid levels, thereby reducing flares. If patients do not reach target on a xanthine oxidase inhibitor alone, lesinurad (Zurampic) can be added.

But treatment compliance is a problem in gout, and so the guidelines also emphasize patient education. “Just like with managing diabetes, patients need to understand that you have to get to a level,” Dr. Saag said. “Patients with diabetes are now tuned into the idea of measuring hemoglobin A1c, but it turns out that uric acid is even easier to measure. We have a really good target in gout – if you can get serum uric acid below a certain level for enough time, you won’t have gout anymore. This is one condition in rheumatology that you can actually get rid of with aggressive therapy.”

To create the guidelines, the authors systematically searched Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane database for trials of gout in which clinicians used prespecified timelines and endpoints to guide therapy. Fifty-five papers met criteria for full review, but none reported on randomized trials of treat-to-target approaches, so the authors based their guidance on expert opinion. Although most recommendations reflect a “very high level of agreement,” the authors underscore the yawning research gap in gout by listing questions to guide future studies. These begin with the most fundamental – “What is the optimal target serum urate level to manage gout?” and “How often should the serum urate level be measured to optimally control disease?”

At least some answers may be forthcoming, Dr. Saag said. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Office of Research and Development is planning a first-in-kind randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial comparing allopurinol and febuxostat in 950 patients with gout, including those with comorbid stage 3 (moderate) chronic kidney disease. Researchers will titrate doses based on a treat-to-target approach. Recruitment will occur over 2 years, the trial will run for 4 years, and participants will be followed for 72 weeks.

Novartis, Berlin-Chemie Menarini, AstraZeneca, and Ardea Biosciences provided funding for the creation of the recommendations. Dr. Kiltz disclosed research support and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Chugai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Saag disclosed ties to Ardea/AstraZeneca, Crealta, and Takeda. Seven other guidelines authors disclosed ties to industry. The remaining six had no conflicts of interest.

The first treat-to-target recommendations for gout emphasize keeping serum uric acid levels below 6 mg/dL (less than 360 mmol/L), but base this and other guidance on expert opinion because no published trials have compared gout treatments head to head.

“[We] considered dissolution of crystals and prevention of flares to be fundamental; patient education, ensuring adherence to medications, and monitoring serum urate levels were also considered to be of major importance,” wrote Uta Kiltz, MD, of Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet and Ruhr University Bochum in Herne, Germany, and her coauthors (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-20946).

Treating to a therapeutic target is becoming the norm in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. But despite some recent progress in gout – including updated recommendations (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jul 25 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707) and Food and Drug Administration approval of the first selective urate transporter inhibitor – it is lagging behind, said Kenneth Saag, MD, a guideline coauthor and rheumatologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“This is partly because gout has been a dramatically understudied disease,” Dr. Saag said in an interview. Indeed, although it affects at least 8 million people in the United States, is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in men, and is rising in prevalence with population aging and the obesity epidemic, gout has received much less research funding than rheumatoid arthritis, he noted.

Gout’s insidious nature may be one reason. “Gout affects people in an intermittent way before it becomes a chronic arthritis, and during that initial phase, it is not viewed by many as more than a nuisance,” Dr. Saag said. “The challenge is that gout really is a disease that ultimately causes a lot of morbidity. If serum urate levels are not controlled, hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease can all accompany gout.”

Accordingly, the No. 1 goal in gout is to meet the serum urate target, and it “doesn’t really matter” what clinicians use to get there, Dr. Saag said. Both allopurinol and febuxostat can effectively lower serum uric acid levels, thereby reducing flares. If patients do not reach target on a xanthine oxidase inhibitor alone, lesinurad (Zurampic) can be added.

But treatment compliance is a problem in gout, and so the guidelines also emphasize patient education. “Just like with managing diabetes, patients need to understand that you have to get to a level,” Dr. Saag said. “Patients with diabetes are now tuned into the idea of measuring hemoglobin A1c, but it turns out that uric acid is even easier to measure. We have a really good target in gout – if you can get serum uric acid below a certain level for enough time, you won’t have gout anymore. This is one condition in rheumatology that you can actually get rid of with aggressive therapy.”

To create the guidelines, the authors systematically searched Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane database for trials of gout in which clinicians used prespecified timelines and endpoints to guide therapy. Fifty-five papers met criteria for full review, but none reported on randomized trials of treat-to-target approaches, so the authors based their guidance on expert opinion. Although most recommendations reflect a “very high level of agreement,” the authors underscore the yawning research gap in gout by listing questions to guide future studies. These begin with the most fundamental – “What is the optimal target serum urate level to manage gout?” and “How often should the serum urate level be measured to optimally control disease?”

At least some answers may be forthcoming, Dr. Saag said. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Office of Research and Development is planning a first-in-kind randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial comparing allopurinol and febuxostat in 950 patients with gout, including those with comorbid stage 3 (moderate) chronic kidney disease. Researchers will titrate doses based on a treat-to-target approach. Recruitment will occur over 2 years, the trial will run for 4 years, and participants will be followed for 72 weeks.

Novartis, Berlin-Chemie Menarini, AstraZeneca, and Ardea Biosciences provided funding for the creation of the recommendations. Dr. Kiltz disclosed research support and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Chugai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Saag disclosed ties to Ardea/AstraZeneca, Crealta, and Takeda. Seven other guidelines authors disclosed ties to industry. The remaining six had no conflicts of interest.

The first treat-to-target recommendations for gout emphasize keeping serum uric acid levels below 6 mg/dL (less than 360 mmol/L), but base this and other guidance on expert opinion because no published trials have compared gout treatments head to head.

“[We] considered dissolution of crystals and prevention of flares to be fundamental; patient education, ensuring adherence to medications, and monitoring serum urate levels were also considered to be of major importance,” wrote Uta Kiltz, MD, of Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet and Ruhr University Bochum in Herne, Germany, and her coauthors (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-20946).

Treating to a therapeutic target is becoming the norm in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. But despite some recent progress in gout – including updated recommendations (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jul 25 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707) and Food and Drug Administration approval of the first selective urate transporter inhibitor – it is lagging behind, said Kenneth Saag, MD, a guideline coauthor and rheumatologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“This is partly because gout has been a dramatically understudied disease,” Dr. Saag said in an interview. Indeed, although it affects at least 8 million people in the United States, is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in men, and is rising in prevalence with population aging and the obesity epidemic, gout has received much less research funding than rheumatoid arthritis, he noted.

Gout’s insidious nature may be one reason. “Gout affects people in an intermittent way before it becomes a chronic arthritis, and during that initial phase, it is not viewed by many as more than a nuisance,” Dr. Saag said. “The challenge is that gout really is a disease that ultimately causes a lot of morbidity. If serum urate levels are not controlled, hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease can all accompany gout.”

Accordingly, the No. 1 goal in gout is to meet the serum urate target, and it “doesn’t really matter” what clinicians use to get there, Dr. Saag said. Both allopurinol and febuxostat can effectively lower serum uric acid levels, thereby reducing flares. If patients do not reach target on a xanthine oxidase inhibitor alone, lesinurad (Zurampic) can be added.

But treatment compliance is a problem in gout, and so the guidelines also emphasize patient education. “Just like with managing diabetes, patients need to understand that you have to get to a level,” Dr. Saag said. “Patients with diabetes are now tuned into the idea of measuring hemoglobin A1c, but it turns out that uric acid is even easier to measure. We have a really good target in gout – if you can get serum uric acid below a certain level for enough time, you won’t have gout anymore. This is one condition in rheumatology that you can actually get rid of with aggressive therapy.”

To create the guidelines, the authors systematically searched Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane database for trials of gout in which clinicians used prespecified timelines and endpoints to guide therapy. Fifty-five papers met criteria for full review, but none reported on randomized trials of treat-to-target approaches, so the authors based their guidance on expert opinion. Although most recommendations reflect a “very high level of agreement,” the authors underscore the yawning research gap in gout by listing questions to guide future studies. These begin with the most fundamental – “What is the optimal target serum urate level to manage gout?” and “How often should the serum urate level be measured to optimally control disease?”

At least some answers may be forthcoming, Dr. Saag said. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Office of Research and Development is planning a first-in-kind randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial comparing allopurinol and febuxostat in 950 patients with gout, including those with comorbid stage 3 (moderate) chronic kidney disease. Researchers will titrate doses based on a treat-to-target approach. Recruitment will occur over 2 years, the trial will run for 4 years, and participants will be followed for 72 weeks.

Novartis, Berlin-Chemie Menarini, AstraZeneca, and Ardea Biosciences provided funding for the creation of the recommendations. Dr. Kiltz disclosed research support and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Chugai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Saag disclosed ties to Ardea/AstraZeneca, Crealta, and Takeda. Seven other guidelines authors disclosed ties to industry. The remaining six had no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Highlights From the 2016 ECTRIMS Meeting

Modern breast surgery: What you should know

In a striking trend, the rate of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) has risen by 30% over the last 10 years in the United States.1 Many women undergo CPM because of the fear and anxiety of cancer recurrence and their perceived risk of contralateral breast cancer; however, few women have a medical condition that necessitates removal of the contralateral breast. The medical indications for CPM include having a pathogenic genetic mutation (eg, BRCA1 and BRCA2), a strong family history of breast cancer, or prior mediastina chest radiation.

The actual risk of contralateral breast cancer is much lower than perceived. In women without a genetic mutation, the 10-year risk of contralateral breast cancer is only 3% to 5%.1 Also, CPM does not prevent the development of metastatic disease and offers no survival benefit over breast conservation or unilateral mastectomy.2 Furthermore, compared with unilateral therapeutic mastectomy, the “upgrade” to a CPM carries a 2.7-fold risk of a major surgical complication.3 It is therefore important that patients receive appropriate counseling regarding CPM, and that this counseling include cancer stage at diagnosis, family history and genetic risk, and cancer versus surgical risk (see “Counseling patients on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy” for key points to cover in patient discussions).

Counseling patients on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

Commonly, patients diagnosed with breast cancer consider having their contralateral healthy breast removed as part of a bilateral mastectomy. They often experience severe anxiety about the cancer coming back and believe that removing both breasts will enable them to live longer. Keep the following key facts in mind when discussing treatment options with breast cancer patients.

Cancer stage at diagnosis. How long a patient lives from the time of her breast cancer diagnosis depends on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis, not the type of surgery performed. A woman with early stage I or stage II breast cancer has an 80% to 90% chance of being cancer free in 5 years.1 The chance of cancer recurring in the bones, liver, or lungs (metastatic breast cancer) will not be changed by removing the healthy breast. The risk of metastatic recurrence can be reduced, however, with chemotherapy and/or with hormone-blocker therapy.

Family history and genetic risk. Few women have a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian and other cancers, and this issue should be addressed with genetic counseling and testing prior to surgery. Those who carry a cancer-causing gene, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2, are at increased risk (40% to 60%) for a second or third breast cancer, especially if they are diagnosed at a young age (<50 years).2,3 In women who have a genetic mutation, removing both breasts and sometimes the ovaries can prevent development of another breast cancer. But this will not prevent spread of the cancer that is already present. Only chemotherapy and hormone blockers can prevent the spread of cancer.

Cancer risk versus surgical risk. For women with no family history of breast cancer, no genetic mutation, and no prior chest wall radiation, the risk of developing a new breast cancer in their other breast is only 3% to 5% every 10 years.3,4 This means that they have a 95% chance of not developing a new breast cancer in their healthy breast. Notably, removing the healthy breast can double the risk of postsurgical complications, including bleeding, infection, and loss of tissue and implant. The mastectomy site will be numb and the skin and nipple areola will not have any function other than cosmetic. Finally, wound complications from surgery could delay the start of important cancer treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiation.

The bottom line. Unless a woman has a strong family history of breast cancer, is diagnosed at a very young age, or has a genetic cancer-causing mutation, removing the contralateral healthy breast is not medically necessary and is not routinely recommended.

References

- Hennigs A, Riedel F, Gondos A, et al. Prognosis of breast cancer molecular subtypes in routine clinical care: a large prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):734.

- Graeser MK, Engel C, Rhiem K, et al. Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5887–5992.

- Curtis RE, Ron E, Hankey BF, Hoover RN. New malignancies following breast cancer. In: Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, et al, eds. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. 2006:181–205. http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/publications/mpmono. Accessed September 18, 2016.

- Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1564–1569.

Women should be made aware that there are alternatives to mastectomy that have similar, or even better, outcomes with improved quality of life. Furthermore, a multi‑disciplinary, team-oriented approach with emphasis on minimally invasive biopsy and better cosmetic outcomes has enhanced quality of care. Knowledge of this team approach and of modern breast cancer treatments is essential for general ObGyns as this understanding improves the overall care and guidance—specifically regarding referral to expert, high-volume breast surgeons—provided to those women most in need.

Expanded treatment options for breast cancer

Advancements in breast surgery, better imaging, and targeted therapies are changing the paradigm of breast cancer treatment.

Image-guided biopsy is key in decision making

When an abnormality is found in the breast, surgical excision of an undiagnosed breast lesion is no longer considered an appropriate first step. Use of image-guided biopsy or minimally invasive core needle biopsy allows for accurate diagnosis of a breast lesion while avoiding a potentially breast deforming and expensive surgical operation. It is always better to go into the operating room (OR) with a diagnosis and do the right operation the first time.

A core needle biopsy, results of which demonstrate a benign lesion, helps avoid breast surgery in women who do not need it. If cancer is diagnosed on biopsy, the extent of disease can be better evaluated and decision making can be more informed, with a multidisciplinary approach used to consider the various options, including genetic counseling, plastic surgery consultation, or neoadjuvant therapy. Some lesions, such as those too close to the skin, chest wall, or an implant, may not be amenable to core needle biopsy and therefore require surgical excision for diagnosis.

Benefits of a multidisciplinary tumor conference

It is important for a multidisciplinary group of cancer specialists to review a patient’s case and discuss the ideal treatment plan prior to surgery. Some breast cancer subtypes (such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]–overamplified breast cancer and many triple-negative breast cancers) are very sensitive to chemotherapy, and patients with these tumor types may benefit from receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery. New types of chemotherapy may allow up to 60% of some breast cancers to diminish almost completely, with subsequent improved cosmetic results of breast surgery.4 It may also allow time for genetic counseling and testing prior to surgery. (See “How to code for a multidisciplinary tumor conference” for appropriate coding procedure.)

How to code for a multidisciplinary tumor conference

Melanie Witt, RN, MA

There are two coding choices for team conferences involving physician participation. If the patient and/or family is present, the CPT instruction is to bill a problem E/M service code (99201-99215) based on the time spent during this coordination of care/counseling. Documentation would include details about the conference decisions and implications for care, rather than history or examination.

If the patient is not present, report 99367 (Medical team conference with interdisciplinary team of health care professionals, patient and/or family not present, 30 minutes or more; participation by physician), but note that this code was developed under the assumption that the conference would be performed in a facility setting. Diagnostic coding would be breast cancer.

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This is an excerpt from a companion coding resource for breast cancer–related procedures by Ms. Witt. To read the companion article, “Coding for breast cancer–related procedures: A how-to guide,” in its entirety, click here.

Image-guided lumpectomy

Advances in breast imaging have led to increased identification of nonpalpable breast cancers. Surgical excision of nonpalpable breast lesions requires image guidance, which can be done using a variety of techniques.

Wire-guided localization (WGL) has been used in practice for the past 40 years. The procedure involves placement of a hooked wire under local anesthesia using either mammographic or ultrasound guidance. This procedure is mostly done in the radiology department on the same day as the surgery and requires that the radiologist coordinate with the OR schedule. Besides scheduling conflicts and delays in surgery, this procedure can be complicated by wires becoming dislodged, transected, or migrated, and limits the surgeon’s ability to cosmetically hide the scar in relation to position of the wire. It is uncomfortable for the patient, who must be transported from the radiology department to the OR with a wire extruding from her breast.

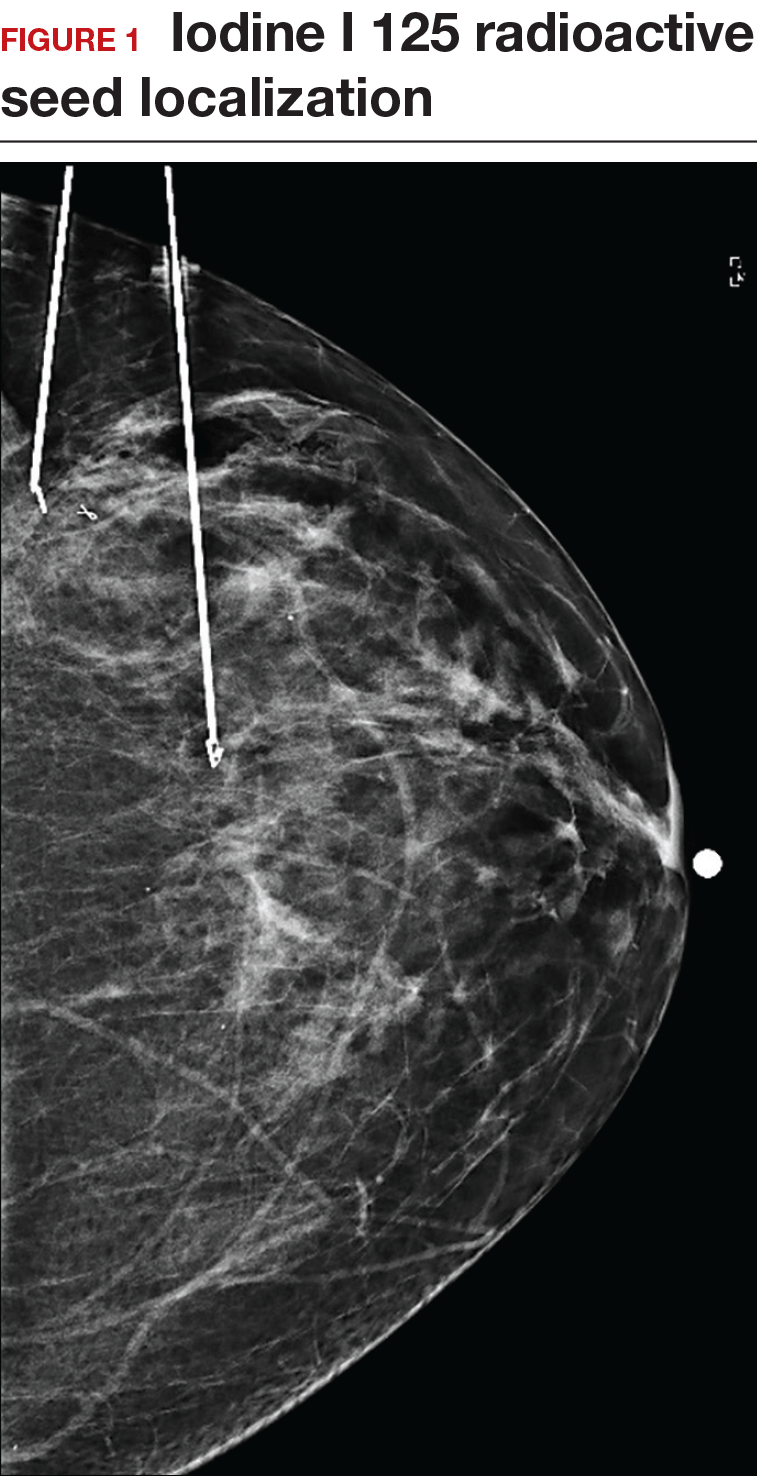

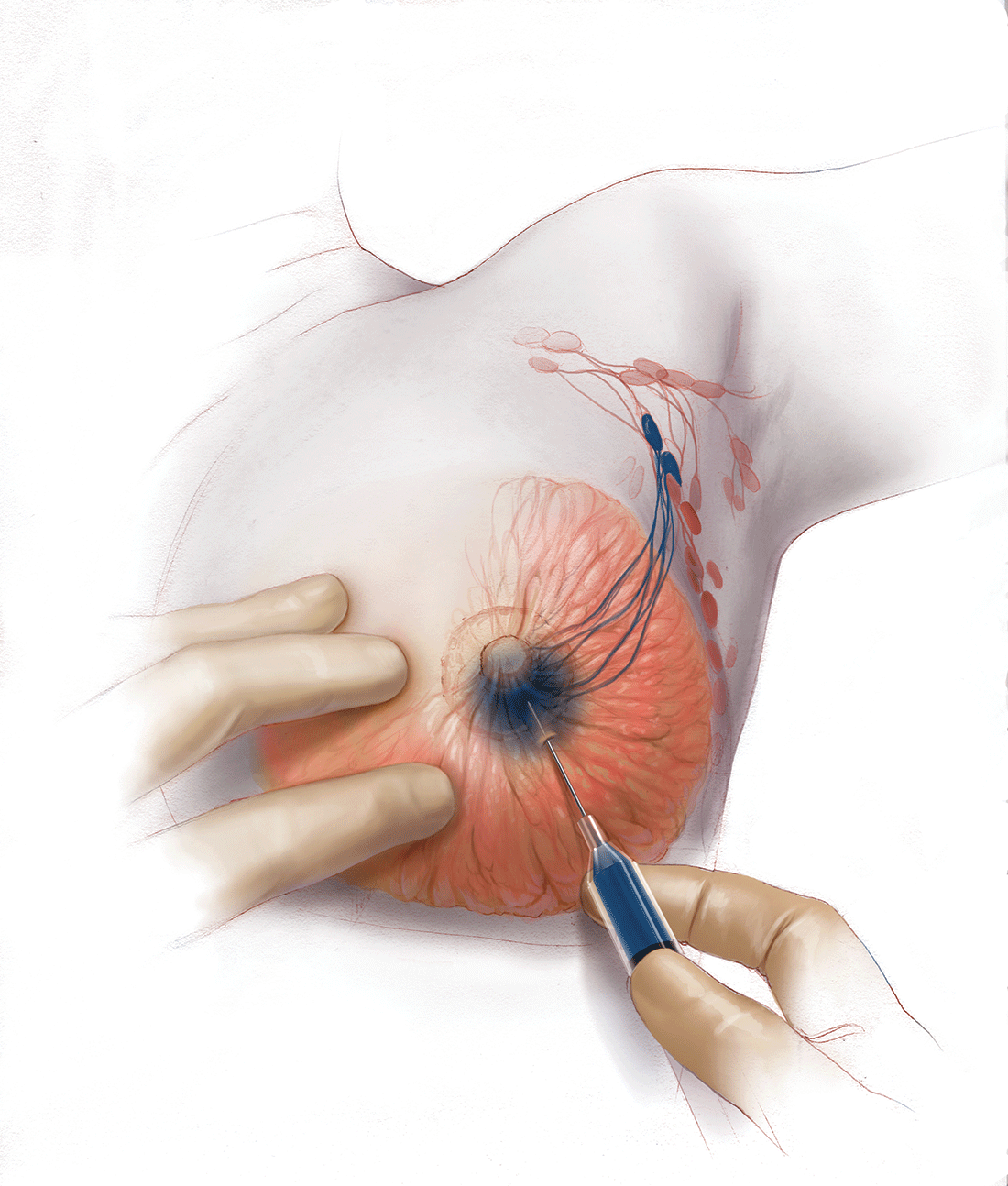

An alternative localization technique is placement of a radioactive source within the tumor, which can then be identified in the OR with a gamma probe.

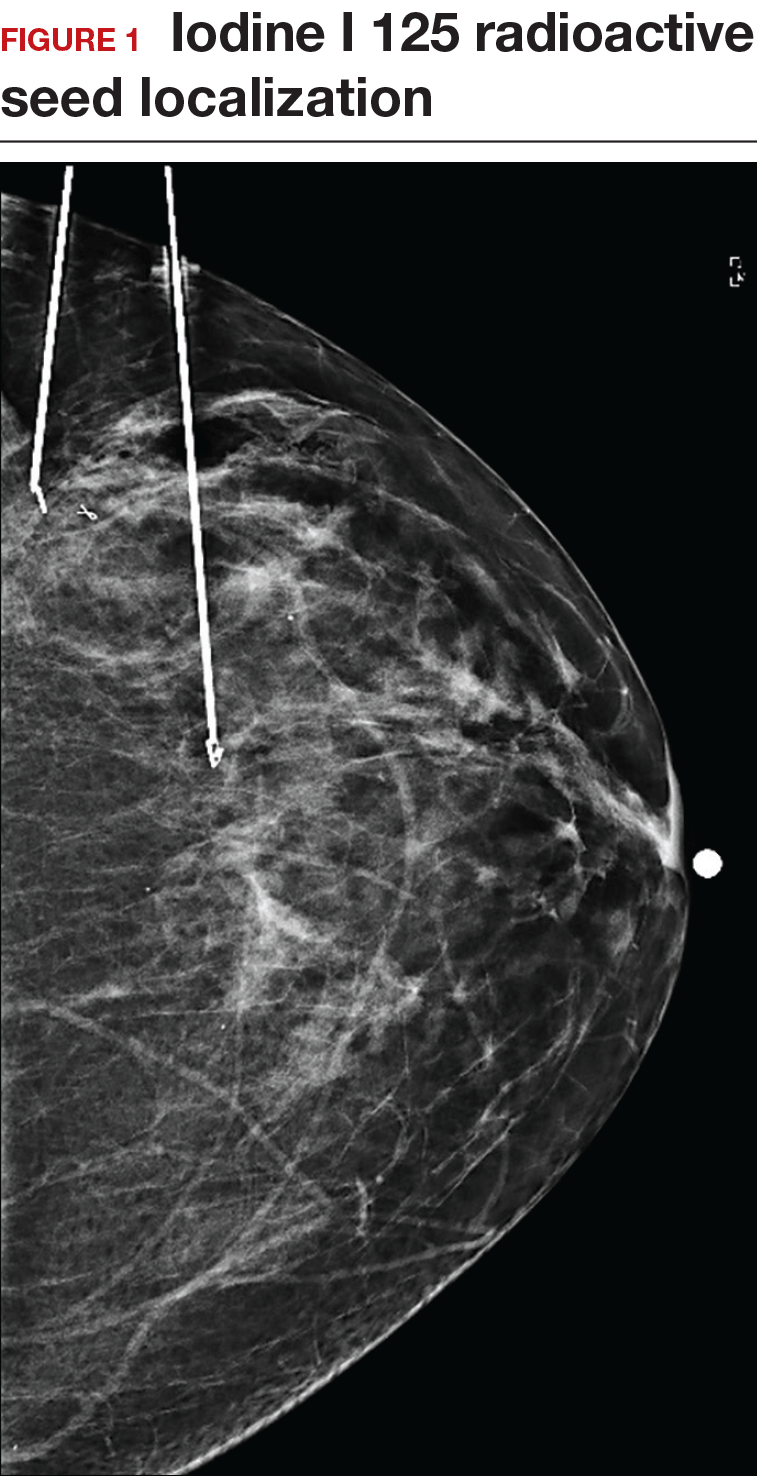

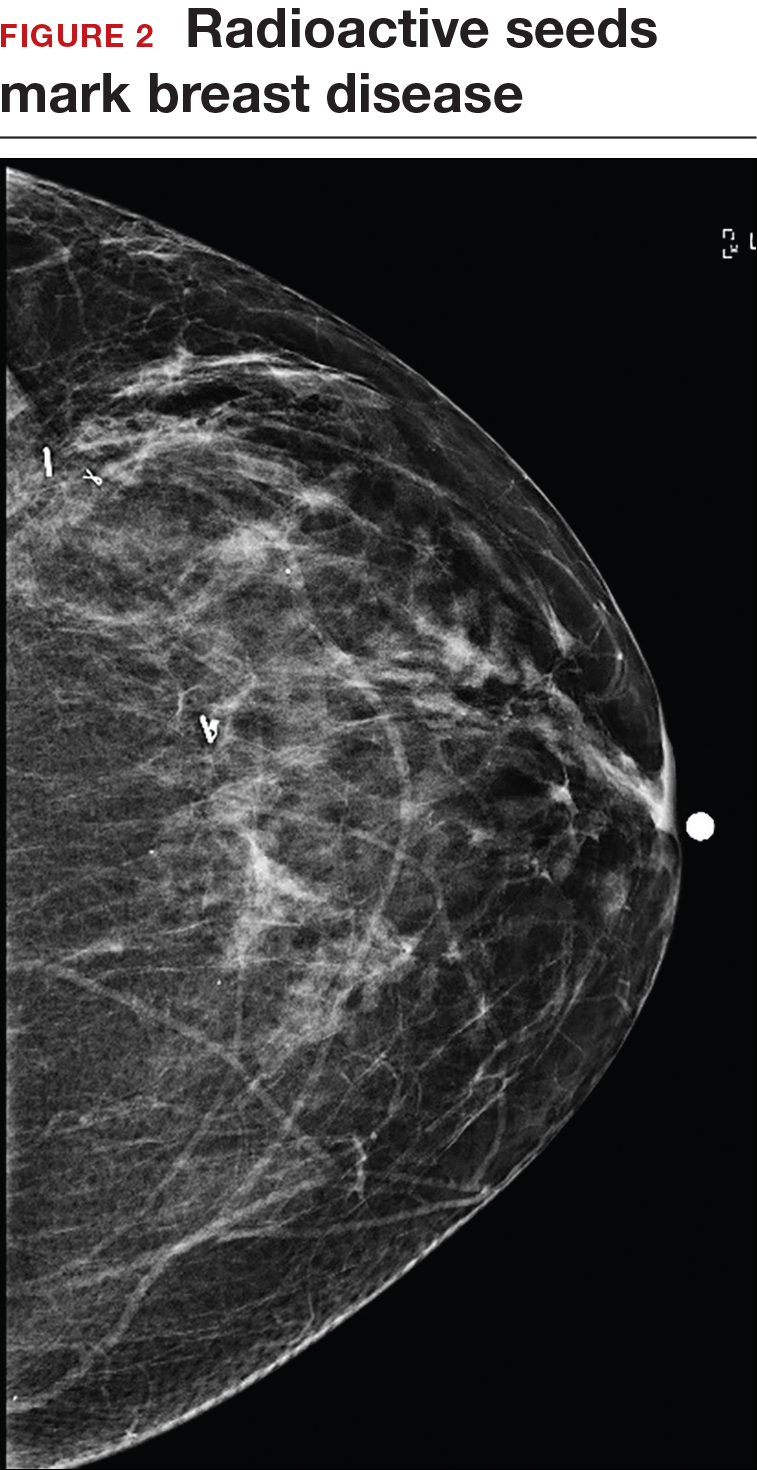

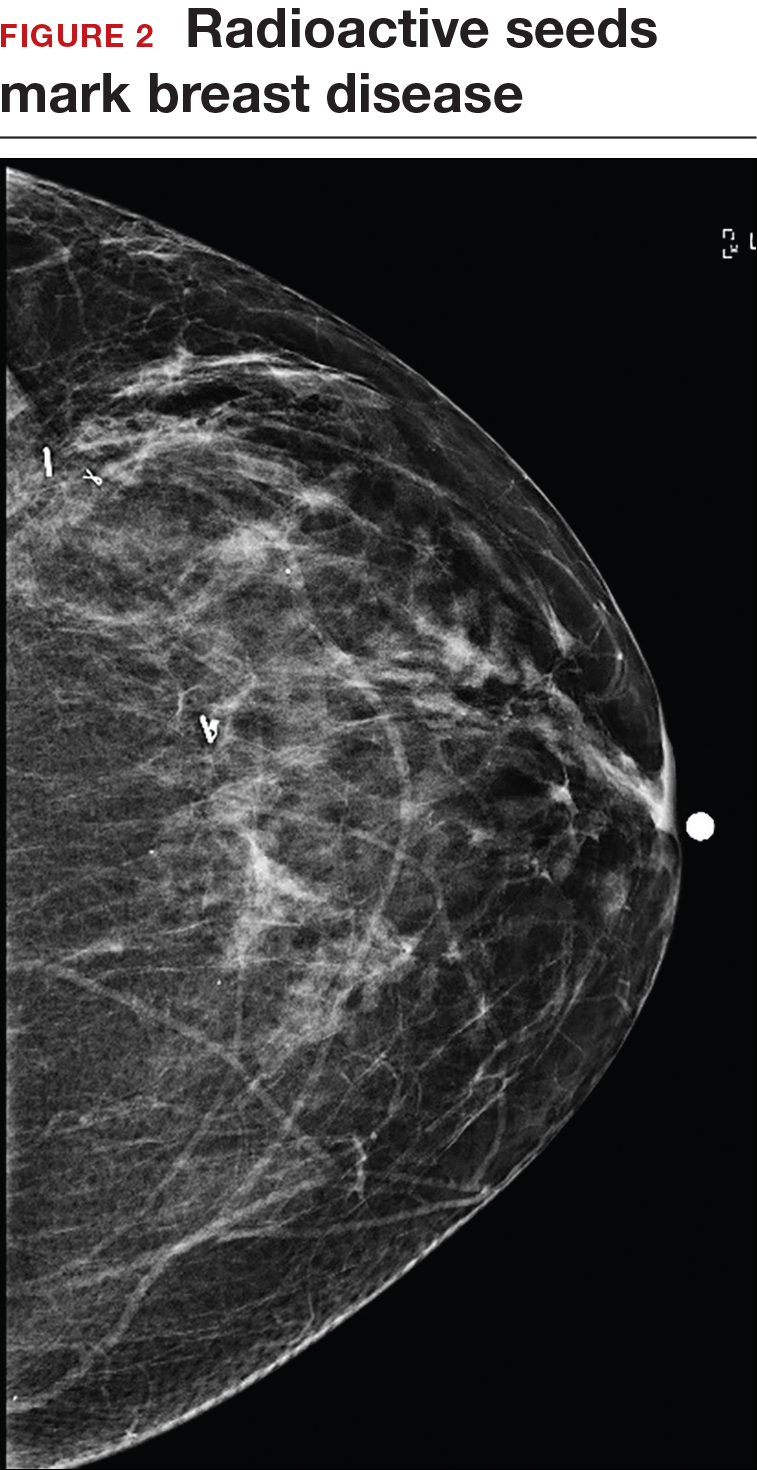

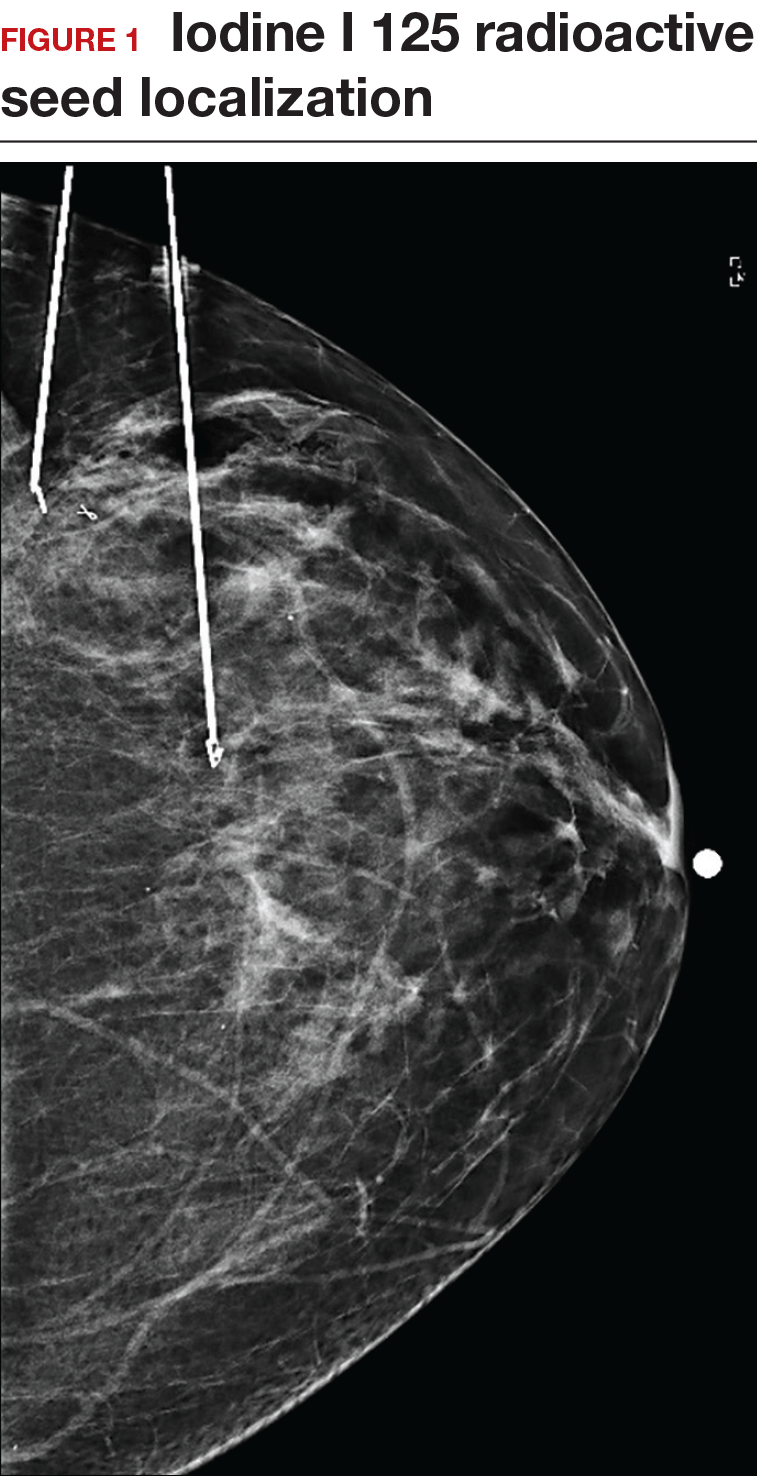

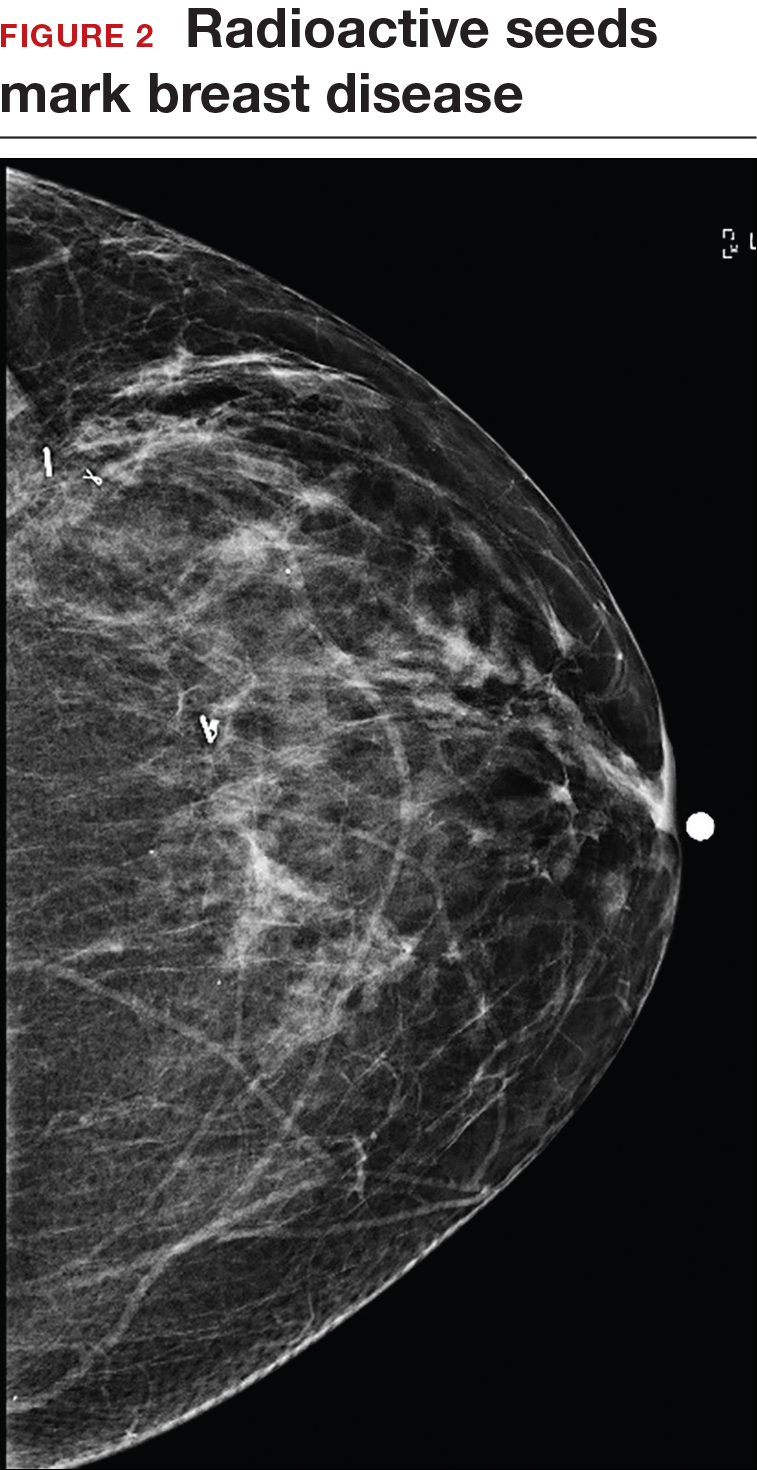

Iodine I 125 Radioactive seed localization (RSL) involves placing a 4-mm titanium radiolabeled seed into the breast lesion under mammographic or ultrasound guidance (FIGURES 1 and 2). The procedure can be performed a few days before surgery in the radiology department, and there is less chance for the seed to become displaced or dislodged. This technique provides scheduling flexibility for the radiologist and reduces OR delays. The surgeon uses the same gamma probe for sentinel node biopsy to find the lesion in the breast, using the setting specific for iodine I 125. Incisions can be tailored anywhere in the breast, and the seed is detected by a focal gamma signal. Once the lumpectomy is performed, the specimen is probed and radiographed to confirm removal of the seed and adequate margins.

Limitations of this procedure include potential loss of the seed during the operation and radiation safety issues regarding handling and disposal of the radioactive isotope. Once the seed has been placed in the patient’s body, it must be removed surgically, as the half-life of iodine I 125 is long (60 days).5 Care must therefore be taken to optimize medical clearance prior to seed placement and to avoid surgery cancellations.

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) allows the surgeon to identify the lesion under general anesthesia in the OR, which is more comfortable for the patient. The surgical incision can be tailored cosmetically and the lumpectomy can be performed with real-time ultrasound visualization of the tumor during dissection. This technique eliminates the need for a separate preoperative seed or wire localization in radiology. However, it can be used only for lesions or clips that are visible by ultrasound. The excised specimen can be evaluated for confirmation of tumor removal and adequate margins via ultrasound and re-excision of close margins can be accomplished immediately if needed.

Results of a meta-analysis of WGL versus IOUS demonstrated a significant reduction of positive margins with the use of IOUS.6 Results of the COBALT trial, in which patients were assigned randomly to excision of palpable breast cancers with either IOUS or palpation, demonstrated a 14% reduction in positive margins in favor of IOUS.7 Surgeon-performed breast ultrasound requires advanced training and accreditation in breast ultrasound through a rigorous certification process offered by the American Society of Breast Surgeons (www.breastsurgeons.org).

Oncoplastic lumpectomy

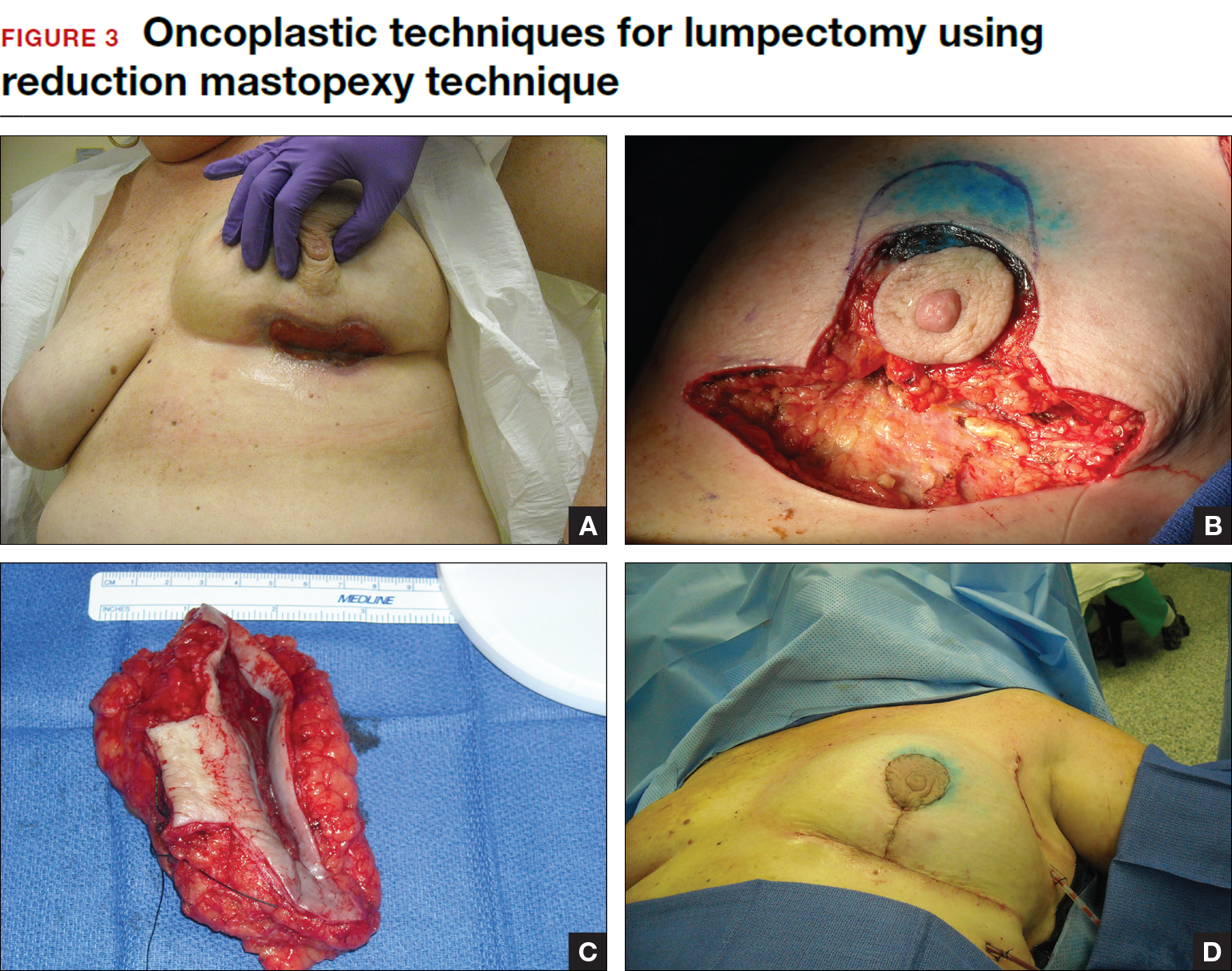

This approach to lumpectomy combines adequate oncologist resection of the breast tumor with plastic surgery techniques to achieve superior cosmesis. This approach allows complete removal of the tumor with negative margins, yet maintains the normal shape and contour of the breast. Two techniques have been described: volume displacement and volume replacement.

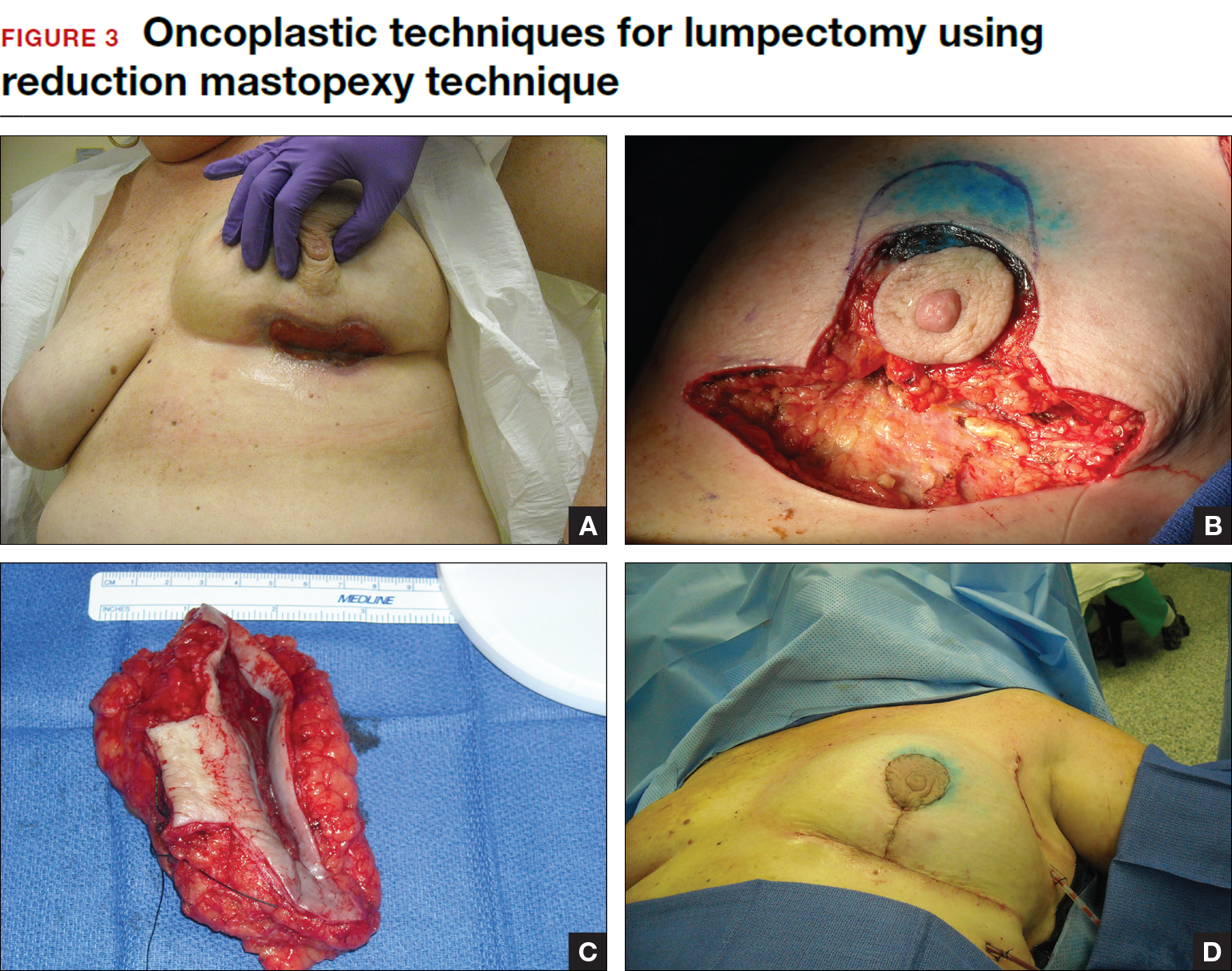

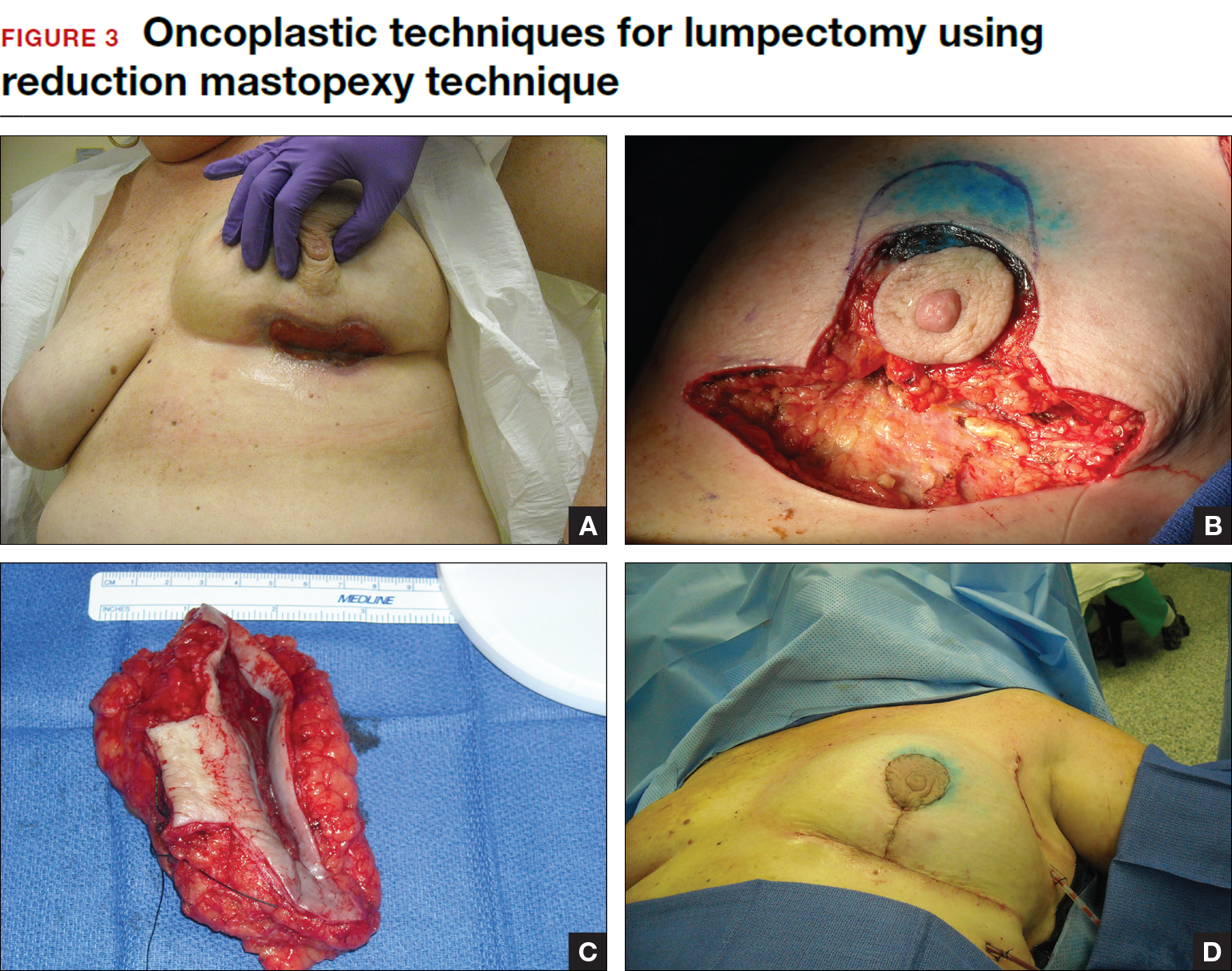

With the volume displacement technique, the surgeon uses adjacent tissue advancement to fill the lumpectomy cavity with the patient’s own surrounding breast tissue (FIGURE 3). The volume replacement technique requires the transposition of autologous tissue from elsewhere in the body.

Oncoplastic lumpectomy allows more women with larger tumors to undergo breast conservation with better cosmetic results. It reduces the number of mastectomies performed without compromising local control and avoids the need for extensive plastic surgery reconstruction and implants. Special effort and attention must be paid to ensure adequate margins utilizing intraoperative specimen radiograph and pathology evaluation.

This procedure requires that the surgeon acquire specialized skills and knowledge of oncologic and plastic surgery techniques, and it is best performed with the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team. Compared with conventional lumpectomy or mastectomy, oncoplastic breast conservation has been shown to reduce re-excision rates, and it has similar rates of local and distant recurrence and similar disease-free survival and overall survival.8,9

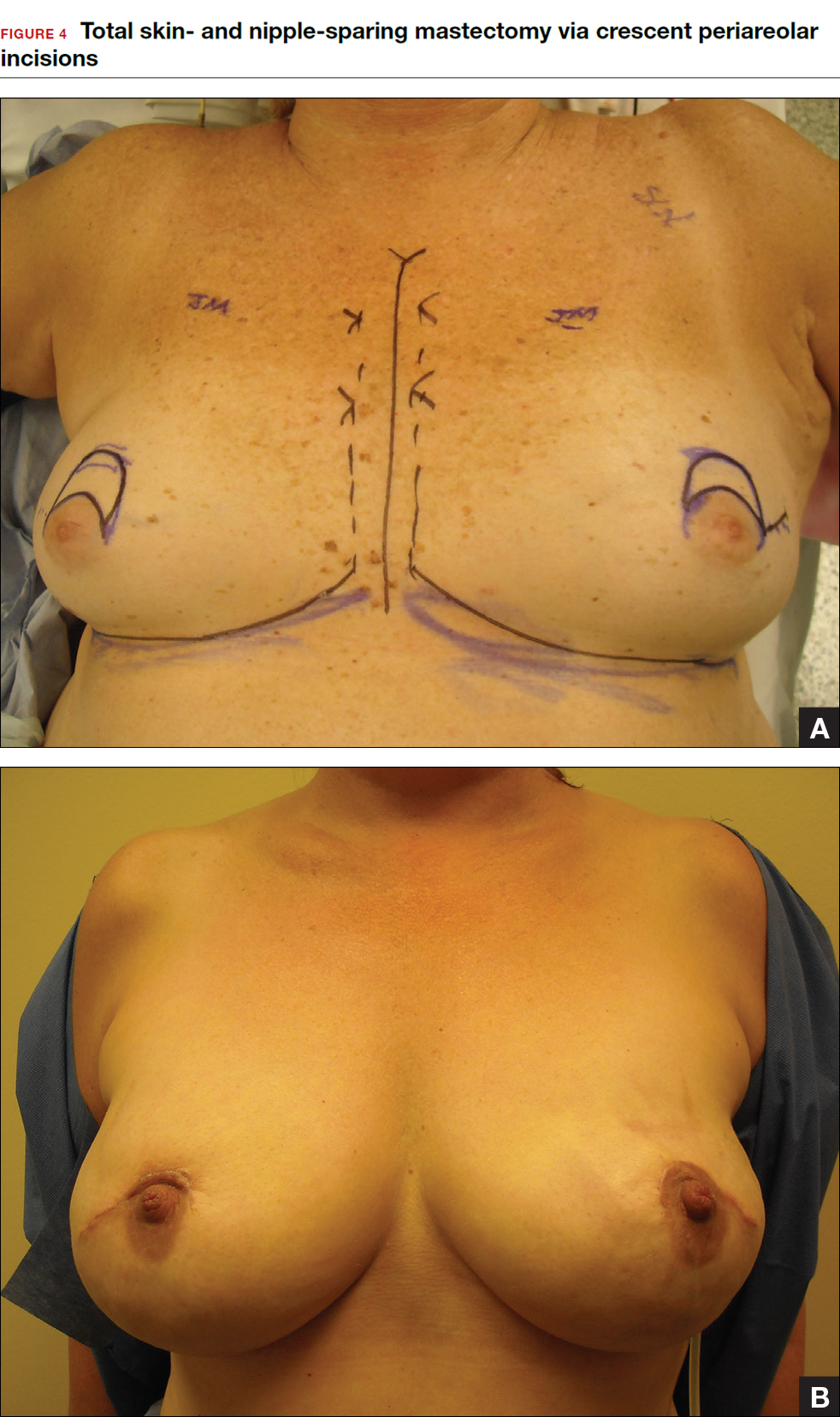

Total skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy

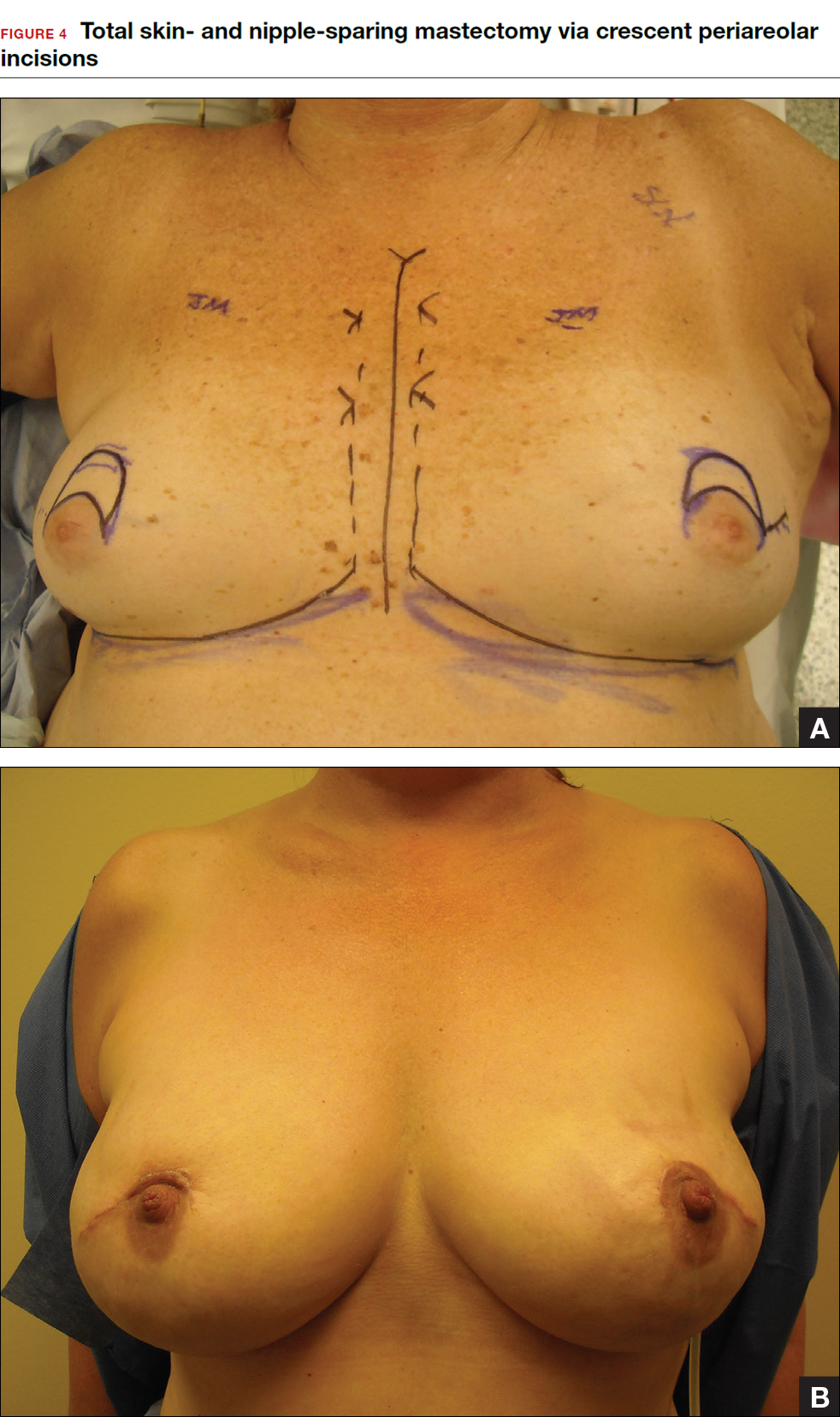

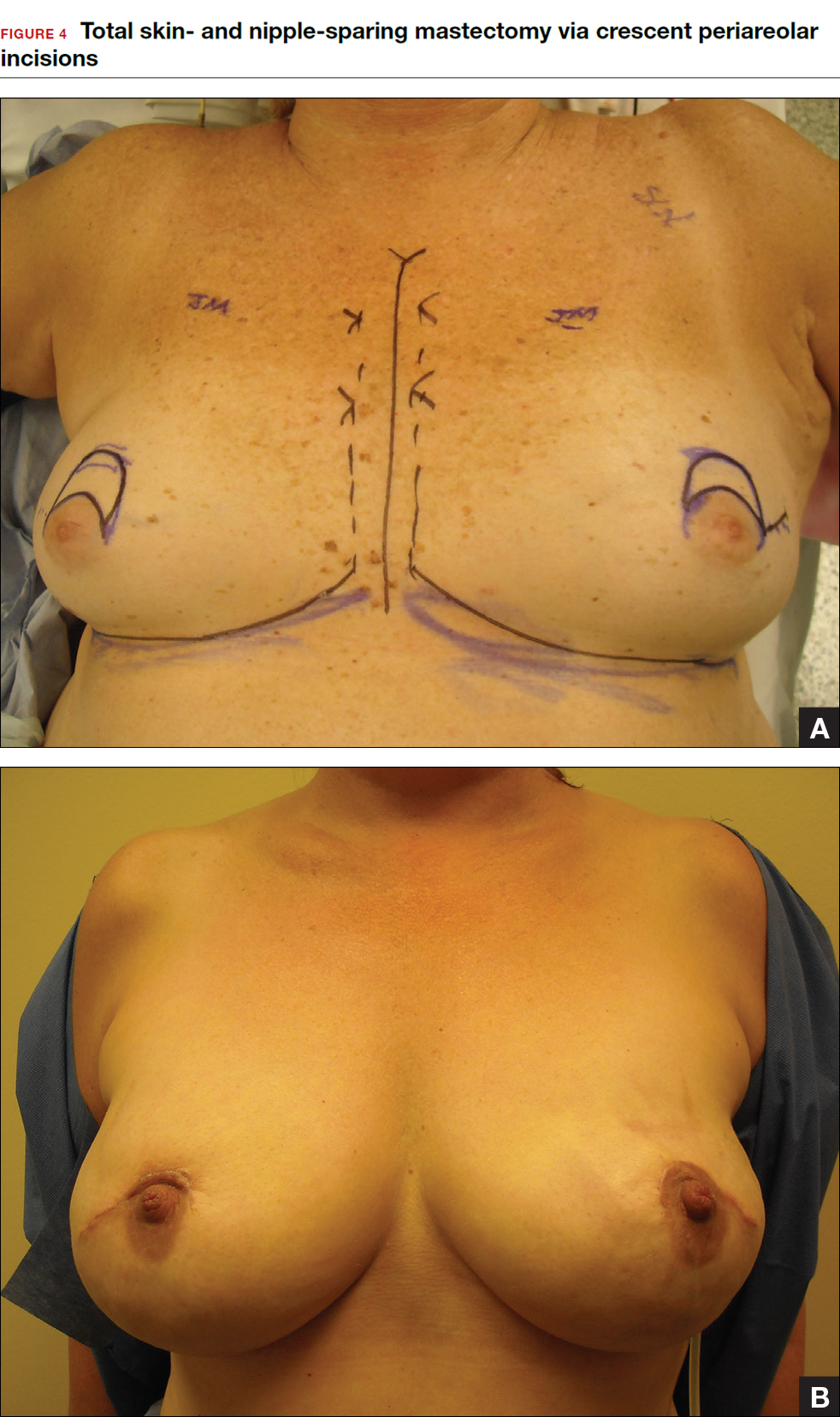

Some patients do not have the option of breast conservation. Women with multicentric breast cancer (more than 1 tumor in different quadrants of the breast) are better served with mastectomy. Surgical techniques for mastectomy have improved and provide women with various options. One option is skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy, which preserves the skin envelope overlying the breast (including the skin of the nipple and areola) while removing the glandular elements of the breast and the majority of ductal tissue beneath the nipple-areola complex (FIGURE 4). This surgery can be performed via hidden scars at the inframammary crease or periareolar and is combined with immediate reconstruction, which provides an excellent cosmetic result.

Surgical considerations include removing glandular breast tissue within its anatomic boundaries while maintaining the blood supply to the skin and nipple-areola complex. Furthermore, there must be close dissection of ductal tissue beneath the nipple-areola complex and intraoperative frozen section of the nipple margin in cancer cases. Nipple-sparing mastectomy is oncologically safe in carefully selected patients who do not have cancer near or within the skin or nipple (eg, Paget disease).10 It is also safe as a prophylactic procedure for patients with genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.11 The procedure is not ideal for smokers or patients with large, pendulous breasts. There is a 3% risk of breast cancer recurrence at the nipple or in the skin or muscle.10 Surgical complications include a 10% to 20% risk of skin or nipple necrosis.12

How do we manage the lymph nodes: Axillary dissection vs sentinel node biopsy?

Evaluation of the axillary nodes is currently part of breast cancer staging and can help the clinician determine the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. It also may assist in assessing the need for extending the radiation field beyond the breast to include the regional lymph nodes. Patients with early stage (stage I and II) breast cancer who do not have abnormal palpable lymph nodes or biopsy-proven metastasis to axillary nodes qualify for sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy.

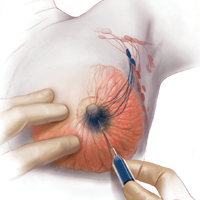

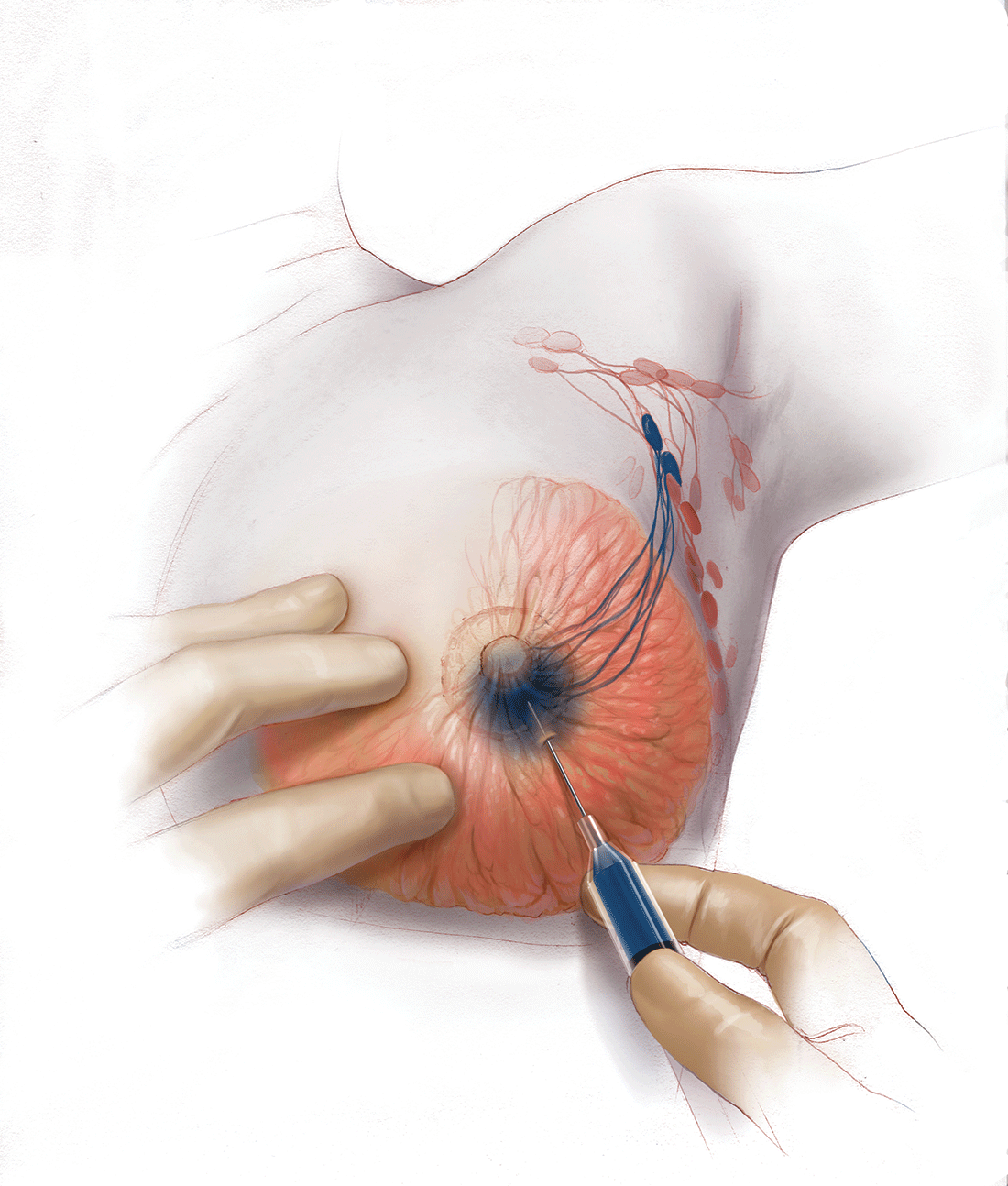

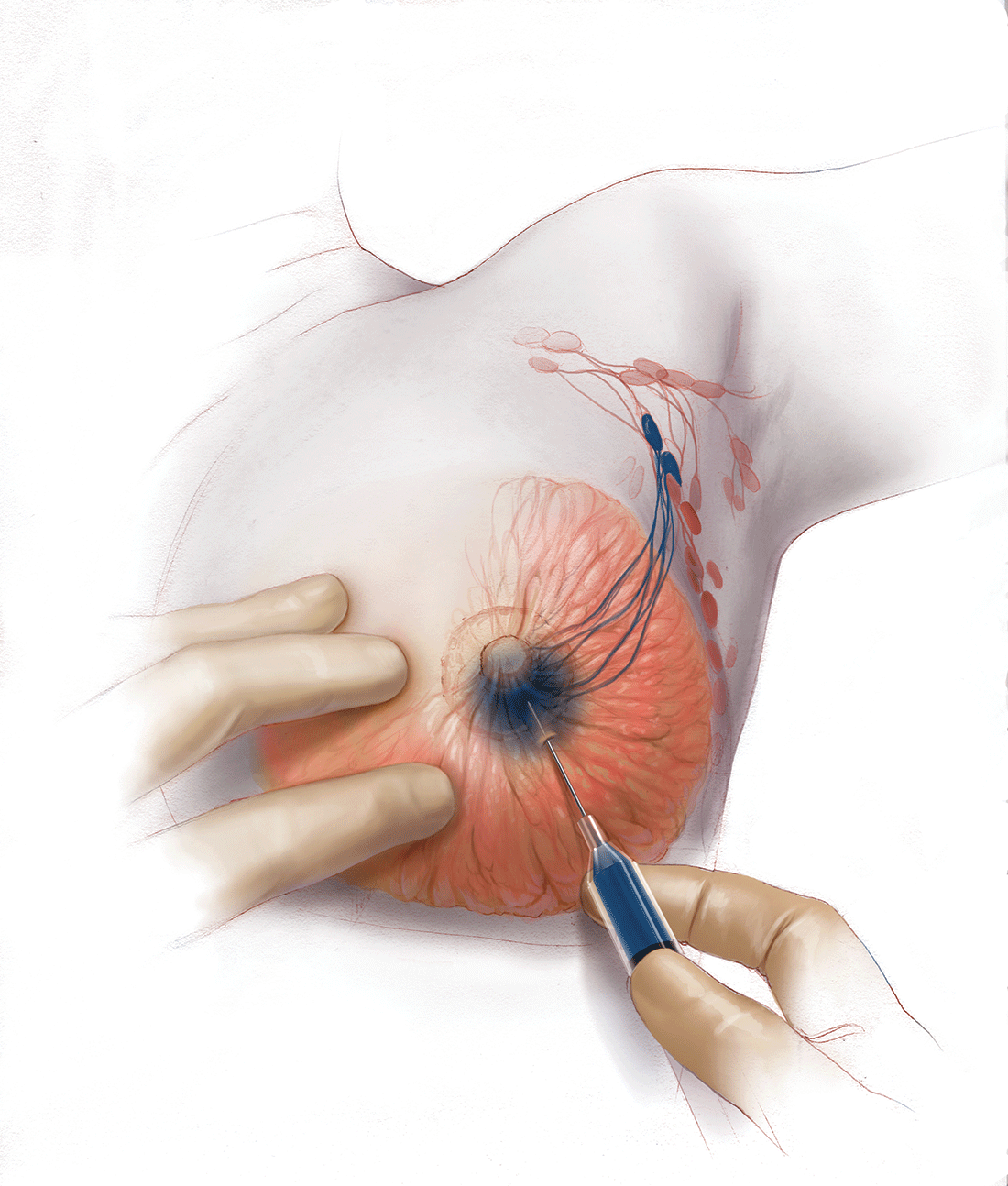

Sentinel node biopsy = less morbidity with no loss of accuracy. Compared with axillary lymph node dissection (ALND; removing all the level I and II nodes in the axilla), SLN biopsy has a 98% accuracy and is associated with less morbidity from lymphedema. The procedure involves injecting the breast with 2 tracers: a radioactive isotope, injected into the breast within 24 hours of the operation, and isosulfan blue dye, injected into the breast in the OR at the time of surgery (see illustration). Both tracers travel through the breast lymphatics and concentrate in the first few lymph nodes that drain the breast. The surgery is performed through a separate axillary incision, and the blue and radioactive lymph nodes are individually dissected and removed for pathologic evaluation. On average, 2 to 4 sentinel nodes are removed, including any suspicious palpable nodes. In experienced hands, this procedure has a false-negative rate of less than 5% to 10%.13

Axillary node dissection no longer standard of care. The indication for a completion ALND has changed based on the results of the randomized trial, ACOSOG Z0011.14 In this trial, patients with early stage breast cancer and 1 to 2 positive SLNs who were undergoing breast conservation therapy with radiation and adjuvant systemic therapy were randomly assigned to ALND or no ALND. (The trial did not include patients who were undergoing mastectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or who had more than 2 metastatic lymph nodes.) The investigators found no difference in overall or disease-free survival or local-regional recurrence between the 2 treatment groups over 9.2 years of follow up.14

Based on this practice-changing trial result, guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network no longer recommend completion ALND for patients who meet the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria. For patients who do not meet ACOSOG Z0011 criteria, we do intraoperative pathologic lymph node assessment with either frozen section or imprint cytology, and we perform immediate ALND when results are positive.

Indications for SLN biopsy include:

- invasive breast cancer with clinically negative axillary nodes

- ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with microinvasion or extensive enough to require mastectomy

- clinically negative axillary nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.