User login

Advanced-Practice Providers Have More to Offer Hospital Medicine Groups

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

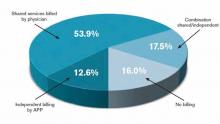

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

We Welcome the Newest SHM Members

- E. Canady, PA, Alabama

- D. Fico, MD, Alabama

- M. Hazin, DO, Arizona

- K. Ota, DO, Arizona

- T. Phan, Arizona

- M. Poquette, RN, Arizona

- T. Imran, MD, Arkansas

- S. Wooden, MD, Arkansas

- E. Agonafer, California

- S. Badger, MHA, California

- G. Buenaflor, DO, California

- H. Cao, California

- P. Cho, California

- N. Chua, MD, California

- W. Daines, California

- B. Gavi, MD, California

- R. Grant, MD, California

- R. Greysen, MD, California

- V. Hsiao, DO, California

- M. Karube, NP, California

- A. King, MD, California

- M. La, MD, California

- M. Lam, MD, California

- T. Moinizandi, MD, California

- C. Sather, MD, California

- K. Steinberg, MD, California

- S. Woo, MHA, California

- D. Abosh, Canada

- N. Cabilio, MD, Canada

- T. Gepraegs, MD, Canada

- G. Jeffries, CCFP, Canada

- W. Mayhew, MD, Canada

- W. Wilkins, Canada

- M. Braun, ACNP, Colorado

- E. Chu, MD, Colorado

- D. Katz, Colorado

- R. Kumar, Colorado

- A. Maclennan, MD, Colorado

- P. Ryan, Colorado

- O. Akande, MD, Connecticut

- L. Colabelli, Connecticut

- S. Green, ACNP, Connecticut

- S. Lin, Connecticut

- P. Patel, MD, Connecticut

- D. Sewell, MD, Connecticut

- R. Brogan, DO, Florida

- N. Dawson, MD, FACP, Florida

- P. Dhatt, MD, Florida

- N. Griffith, MBA, Florida

- S. Hanson, MD, Florida

- M. Hernandez, MD, Florida

- J. Mennie, MD, Florida

- M. Mohiuddin, MD, Florida

- A. Moynihan, ARNP, Florida

- Y. Patel, MD, Florida

- D. Reto, Florida

- C. Reyes, ARNP, Florida

- B. Fisher, PA-C, Georgia

- S. Fleming, ANP, Georgia

- J. Gilbert, MD, Georgia

- M. Holbrook, FNP, Georgia

- S. Hung, ANP, Georgia

- N. Maignan, MD, Georgia

- P. Nanda, MD, Georgia

- H. Pei, MD, Georgia

- K. Rangnow, NP, Georgia

- S. Shams, MD, Georgia

- L. Wilson, Georgia

- E. Allen, DO, Idaho

- E. Brennan, Illinois

- K. Gul, Illinois

- L. Hansen, MD, Illinois

- D. Nguyen, MD, Illinois

- F. Porter, MD,FACP, Illinois

- A. Ranadive, Illinois

- L. Shahani, MD, Illinois

- J. Tallcott, Illinois

- K. Tulla, Illinois

- N. Wiegley, Illinois

- R. Young, MD, MS, Illinois

- D. Yu, MD, Illinois

- Z. Alba, MD, Indiana

- G. Alcorn, MD, Indiana

- K. Dorairaj, MD, Indiana

- W. Harbin, DO, Indiana

- A. Patel, MD, Indiana

- J. Shamoun, MD, Indiana

- N. Wells, MD, Indiana

- J. Wynn, USA, Indiana

- N. Hartog, MD, Iowa

- K. Emoto, Japan

- M. Sakai, MD, Japan

- P. Poddutoori, MBBS, Kansas

- T. Stofferson, ACMPE, Kansas

- B. Huneycutt, MD, Kentucky

- S. Muldoon, MD, Kentucky

- W. Travis, MD, Kentucky

- B. Molbert, NP, Louisiana

- M. Jacquet, MD, Maine

- P. Pahel, FNP, Maine

- S. Albanez, Maryland

- A. Anigbo, MBBS, Maryland

- A. Antar, PhD, Maryland

- E. Bice, DO, Maryland

- J. Clark, Maryland

- T. Hall, Maryland

- B. Huntley, PA, Maryland

- J. Kaka, Maryland

- D. Kidd, Maryland

- R. Landis, BA, Maryland

- T. Lawgaw, PA-C, Maryland

- M. Singh, Maryland

- M. Baggett, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Barkoudah, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bortinger, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bukli, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Dhand, MD, Massachusetts

- L. DiPompo, Massachusetts

- J. Donze, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Ganatra, Massachusetts

- R. Goldberg, MD, Massachusetts

- R. Gumber, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Lawrason, MD, Massachusetts

- N. Lebaka, MD, Massachusetts

- M. Mahmoud, MD, Massachusetts

- G. Mills, Massachusetts

- M. Mohamed, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Parr, MPH, Massachusetts

- D. Ramirez, PA-C, Massachusetts

- L. Solis-Cohen, MD, Massachusetts

- C. Yu, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Bazan, Michigan

- J. Bedore, PA-C, Michigan

- P. Bradley, MD, Michigan

- L. Butz, MD, Michigan

- S. Chase, PharmD, Michigan

- A. Funk, MD, Michigan

- N. Khalid, MD, Michigan

- R. Patel, MD, Michigan

- I. Patsias, MD, Michigan

- P. Sanchez, Michigan

- D. Bowman, Minnesota

- M. Buchner, MD, Minnesota

- S. Mehmood, MD, Minnesota

- J. Ratelle, Minnesota

- M. Werpy, DO, Minnesota

- M. White, MD, Minnesota

- T. Willson, Minnesota

- H. Wood, MD, Minnesota

- S. Altmiller, Mississippi

- R. Andersson, Missouri

- K. Chuu, MD, Missouri

- M. Mullick, MD, Missouri

- C. Obi, MBBS, Missouri

- M. O’Dell, MD, Missouri

- D. Smith, MBA, Missouri

- J. Tyler, DO, Missouri

- S. Riggs, NP, Nebraska

- A. Bose, MD, New Hampshire

- F. Gaffney Comeau, New Hampshire

- C. Raymond, MSN, New Hampshire

- M. Balac, New Jersey

- A. Boa Hocbo, MD, New Jersey

- C. DeLuca, New Jersey

- P. Jadhav, MD, New Jersey

- S. Kishore, MBBS, New Jersey

- P. Krishnamoorthy, MD, New Jersey

- B. LaMotte, PharmD, New Jersey

- C. Maloy, PA-C, New Jersey

- A. Oakley, New Jersey

- K. Pratt, MD, New Jersey

- J. Yacco, New Jersey

- A. Zeff, New Jersey

- K. Caudell, PhD, New Mexico

- G. Ghuneim, MD, New Mexico

- J. Marley, DO, New Mexico

- B. Stricks, New Mexico

- L. Ahmed, New York

- G. Arora, MD, New York

- N. Bangiyeva, MD, New York

- A. Bansal, MD, New York

- L. Belletti, FACP, New York

- N. Bhatt, MPH, New York

- A. Blatt, MD, New York

- T. Chau, New York

- N. Chaudhry, MD, New York

- S. Collins, MD, New York

- L. Coryat, ANP, New York

- R. Dachs, MD, New York

- G. DeCastro, MD, New York

- J. Duffy, ANP, New York

- F. Farzan, MD, New York

- A. Gopal, MD, New York

- S. Hameed, New York

- A. Hanif, MD, New York

- A. Hassan, MD, New York

- A. Howe, New York

- M. Ip, New York

- M. Kelly, MD, New York

- S. Kovtunova, MD, New York

- J. Liu, MD, MPH, New York

- A. Maritato, MD, New York

- K. Mayer, MD, New York

- S. Mehra, New York

- K. Noshiro, MD, New York

- M. Panichas, New York

- V. Rakhvalchuk, DO, New York

- R. Ramkeesoon, New York

- M. Saluja, MD, New York

- P. Shanmugathasan, MD, New York

- S. Sherazi, MD, New York

- J. Shin, MD, New York

- S. Veeramachaneni, MD, New York

- S. Yang, MD, New York

- M. Ardison, MHS, North Carolina

- M. Banks, PA, North Carolina

- W. Brooks, MD, North Carolina

- M. Chadwick, MD, North Carolina

- J. Cowen, DO, North Carolina

- S. Hewitt, North Carolina

- S. Irvin, North Carolina

- J. Kornegay, MD, North Carolina

- K. Larbi-siaw, MD, North Carolina

- J. Pavon, MD, North Carolina

- D. Warner, PA-C, North Carolina

- S. Wells, PA, North Carolina

- S. Abdel-Ghani, MD, Ohio

- D. Abhyankar, Ohio

- A. Alahmar, MD, Ohio

- A. Andreadis, MD, Ohio

- M. Bajwa, Ohio

- A. Blankenship, RN, Ohio

- M. Constantiner, RPh, Ohio

- D. Djigbenou, MD, Ohio

- S. Evans, MD, Ohio

- J. Girard, Ohio

- J. Held, MD, Ohio

- K. Hilder, MD, Ohio

- R. Kanuru, MD, Ohio

- H. Mount, Ohio

- B. Pachmayer, MD, Ohio

- C. Rodehaver, RN, MS, Ohio

- C. Schelzig, MD, FAAP, Ohio

- M. Mathews, Oklahoma

- F. Escaro, Oregon

- S. Hale, MD, Oregon

- E. Meihoff, MD, Oregon

- B. Rainka, Oregon

- A. Behura, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Bussler, Pennsylvania

- J. Chintanaboina, Pennsylvania

- I. Cirilo, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Doomra, Pennsylvania

- G. Gabasan, MD, Pennsylvania

- J. Gengaro, DO, Pennsylvania

- D. Gondek, DO, Pennsylvania

- K. Gonzalez, NP, Pennsylvania

- A. Hellyer, Pennsylvania

- J. Julian, MD, MPH, Pennsylvania

- A. Kainz, Pennsylvania

- S. Kaur, MD, Pennsylvania

- P. Lange, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Leslie, MD, Pennsylvania

- D. McBryan, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Miller, CRNP, Pennsylvania

- S. Nichuls, PA-C, Pennsylvania

- T. Pellegrino, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- K. Reed, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- A. Seasock, PA-C, BS, Pennsylvania

- S. Soenen, Pennsylvania

- V. Subbiah, MD, Pennsylvania

- N. Thingalaya, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Tuttle, PA, Pennsylvania

- G. Vadlamudi, MPH, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Verma, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Wannebo, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Wesoly, PA, Pennsylvania

- L. Eddy, FNP, Rhode Island

- M. Antonatos, MD, South Carolina

- S. Connelly, South Carolina

- D. O’Briant, MD, South Carolina

- R. Agarwal, MD, MBA, Tennessee

- A. Aird, MD, Tennessee

- F. Dragila, MD, Tennessee

- S. Duncan, MD, Tennessee

- M. Flint, MPH, Tennessee

- A. Goldfeld, Tennessee

- R. Gusso, MD, Tennessee

- S. Lane, M.H.A., Tennessee

- C. Long, MD, Tennessee

- M. Naeem, MD, PhD, Tennessee

- C. Aiken, RN, Texas

- D. Berhane, Texas

- M. Cabello, MD, Texas

- A. Caruso, MD, Texas

- P. Desai, Texas

- J. Haygood, Texas

- R. Henderson, MD, Texas

- C. Inniss, Texas

- W. Mirza, DO, Texas

- C. Moreland, MD, Texas

- N. Mulukutla, MD, Texas

- G. Neil, MD, Texas

- I. Nwabude, MD, Texas

- T. Onishi, MD, Texas

- K. Patel, MD, Texas

- B. Pomeroy, MD, Texas

- S. Ray, Texas

- J. Tau, MD, Texas

- M. Blankenship, MD, Utah

- L. Porter, RN, Utah

- J. Strong, MD, Utah

- J. Van Blarcom, MD, Utah

- A. Wood, RN, Utah

- M. Wren, Utah

- M. Anawati, MD, Vermont

- S. Lee, Vermont

- C. Cook, MD, Virginia

- E. Deungwe Yonga, MD, Virginia

- F. Dieter, PA, Virginia

- P. Gill, MD, Virginia

- S. Goldwater, PharmD, Virginia

- R. Martin, MD, Virginia

- T. Masterson, Virginia

- P. Ouellette, MD, Virginia

- M. Plazarte, DO, Virginia

- C. Salamanca, NP, Virginia

- B. Seagroves, MD, Virginia

- G. Slitt, MD, Virginia

- F. Williams, MD, Virginia

- S. Won, NP, MSN, Virginia

- L. Alberts, MD, Washington

- E. Lopez, PA-C, Washington

- L. Lubinski, MD, Washington

- J. Oconer, MD, Washington

- K. Shulman, Washington

- S. Carpenter, MD, West Virginia

- Y. Jones, FAAP, West Virginia

- P. Cartier-Neely, PA, Wisconsin

- D. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

- R. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

- E. Canady, PA, Alabama

- D. Fico, MD, Alabama

- M. Hazin, DO, Arizona

- K. Ota, DO, Arizona

- T. Phan, Arizona

- M. Poquette, RN, Arizona

- T. Imran, MD, Arkansas

- S. Wooden, MD, Arkansas

- E. Agonafer, California

- S. Badger, MHA, California

- G. Buenaflor, DO, California

- H. Cao, California

- P. Cho, California

- N. Chua, MD, California

- W. Daines, California

- B. Gavi, MD, California

- R. Grant, MD, California

- R. Greysen, MD, California

- V. Hsiao, DO, California

- M. Karube, NP, California

- A. King, MD, California

- M. La, MD, California

- M. Lam, MD, California

- T. Moinizandi, MD, California

- C. Sather, MD, California

- K. Steinberg, MD, California

- S. Woo, MHA, California

- D. Abosh, Canada

- N. Cabilio, MD, Canada

- T. Gepraegs, MD, Canada

- G. Jeffries, CCFP, Canada

- W. Mayhew, MD, Canada

- W. Wilkins, Canada

- M. Braun, ACNP, Colorado

- E. Chu, MD, Colorado

- D. Katz, Colorado

- R. Kumar, Colorado

- A. Maclennan, MD, Colorado

- P. Ryan, Colorado

- O. Akande, MD, Connecticut

- L. Colabelli, Connecticut

- S. Green, ACNP, Connecticut

- S. Lin, Connecticut

- P. Patel, MD, Connecticut

- D. Sewell, MD, Connecticut

- R. Brogan, DO, Florida

- N. Dawson, MD, FACP, Florida

- P. Dhatt, MD, Florida

- N. Griffith, MBA, Florida

- S. Hanson, MD, Florida

- M. Hernandez, MD, Florida

- J. Mennie, MD, Florida

- M. Mohiuddin, MD, Florida

- A. Moynihan, ARNP, Florida

- Y. Patel, MD, Florida

- D. Reto, Florida

- C. Reyes, ARNP, Florida

- B. Fisher, PA-C, Georgia

- S. Fleming, ANP, Georgia

- J. Gilbert, MD, Georgia

- M. Holbrook, FNP, Georgia

- S. Hung, ANP, Georgia

- N. Maignan, MD, Georgia

- P. Nanda, MD, Georgia

- H. Pei, MD, Georgia

- K. Rangnow, NP, Georgia

- S. Shams, MD, Georgia

- L. Wilson, Georgia

- E. Allen, DO, Idaho

- E. Brennan, Illinois

- K. Gul, Illinois

- L. Hansen, MD, Illinois

- D. Nguyen, MD, Illinois

- F. Porter, MD,FACP, Illinois

- A. Ranadive, Illinois

- L. Shahani, MD, Illinois

- J. Tallcott, Illinois

- K. Tulla, Illinois

- N. Wiegley, Illinois

- R. Young, MD, MS, Illinois

- D. Yu, MD, Illinois

- Z. Alba, MD, Indiana

- G. Alcorn, MD, Indiana

- K. Dorairaj, MD, Indiana

- W. Harbin, DO, Indiana

- A. Patel, MD, Indiana

- J. Shamoun, MD, Indiana

- N. Wells, MD, Indiana

- J. Wynn, USA, Indiana

- N. Hartog, MD, Iowa

- K. Emoto, Japan

- M. Sakai, MD, Japan

- P. Poddutoori, MBBS, Kansas

- T. Stofferson, ACMPE, Kansas

- B. Huneycutt, MD, Kentucky

- S. Muldoon, MD, Kentucky

- W. Travis, MD, Kentucky

- B. Molbert, NP, Louisiana

- M. Jacquet, MD, Maine

- P. Pahel, FNP, Maine

- S. Albanez, Maryland

- A. Anigbo, MBBS, Maryland

- A. Antar, PhD, Maryland

- E. Bice, DO, Maryland

- J. Clark, Maryland

- T. Hall, Maryland

- B. Huntley, PA, Maryland

- J. Kaka, Maryland

- D. Kidd, Maryland

- R. Landis, BA, Maryland

- T. Lawgaw, PA-C, Maryland

- M. Singh, Maryland

- M. Baggett, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Barkoudah, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bortinger, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bukli, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Dhand, MD, Massachusetts

- L. DiPompo, Massachusetts

- J. Donze, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Ganatra, Massachusetts

- R. Goldberg, MD, Massachusetts

- R. Gumber, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Lawrason, MD, Massachusetts

- N. Lebaka, MD, Massachusetts

- M. Mahmoud, MD, Massachusetts

- G. Mills, Massachusetts

- M. Mohamed, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Parr, MPH, Massachusetts

- D. Ramirez, PA-C, Massachusetts

- L. Solis-Cohen, MD, Massachusetts

- C. Yu, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Bazan, Michigan

- J. Bedore, PA-C, Michigan

- P. Bradley, MD, Michigan

- L. Butz, MD, Michigan

- S. Chase, PharmD, Michigan

- A. Funk, MD, Michigan

- N. Khalid, MD, Michigan

- R. Patel, MD, Michigan

- I. Patsias, MD, Michigan

- P. Sanchez, Michigan

- D. Bowman, Minnesota

- M. Buchner, MD, Minnesota

- S. Mehmood, MD, Minnesota

- J. Ratelle, Minnesota

- M. Werpy, DO, Minnesota

- M. White, MD, Minnesota

- T. Willson, Minnesota

- H. Wood, MD, Minnesota

- S. Altmiller, Mississippi

- R. Andersson, Missouri

- K. Chuu, MD, Missouri

- M. Mullick, MD, Missouri

- C. Obi, MBBS, Missouri

- M. O’Dell, MD, Missouri

- D. Smith, MBA, Missouri

- J. Tyler, DO, Missouri

- S. Riggs, NP, Nebraska

- A. Bose, MD, New Hampshire

- F. Gaffney Comeau, New Hampshire

- C. Raymond, MSN, New Hampshire

- M. Balac, New Jersey

- A. Boa Hocbo, MD, New Jersey

- C. DeLuca, New Jersey

- P. Jadhav, MD, New Jersey

- S. Kishore, MBBS, New Jersey

- P. Krishnamoorthy, MD, New Jersey

- B. LaMotte, PharmD, New Jersey

- C. Maloy, PA-C, New Jersey

- A. Oakley, New Jersey

- K. Pratt, MD, New Jersey

- J. Yacco, New Jersey

- A. Zeff, New Jersey

- K. Caudell, PhD, New Mexico

- G. Ghuneim, MD, New Mexico

- J. Marley, DO, New Mexico

- B. Stricks, New Mexico

- L. Ahmed, New York

- G. Arora, MD, New York

- N. Bangiyeva, MD, New York

- A. Bansal, MD, New York

- L. Belletti, FACP, New York

- N. Bhatt, MPH, New York

- A. Blatt, MD, New York

- T. Chau, New York

- N. Chaudhry, MD, New York

- S. Collins, MD, New York

- L. Coryat, ANP, New York

- R. Dachs, MD, New York

- G. DeCastro, MD, New York

- J. Duffy, ANP, New York

- F. Farzan, MD, New York

- A. Gopal, MD, New York

- S. Hameed, New York

- A. Hanif, MD, New York

- A. Hassan, MD, New York

- A. Howe, New York

- M. Ip, New York

- M. Kelly, MD, New York

- S. Kovtunova, MD, New York

- J. Liu, MD, MPH, New York

- A. Maritato, MD, New York

- K. Mayer, MD, New York

- S. Mehra, New York

- K. Noshiro, MD, New York

- M. Panichas, New York

- V. Rakhvalchuk, DO, New York

- R. Ramkeesoon, New York

- M. Saluja, MD, New York

- P. Shanmugathasan, MD, New York

- S. Sherazi, MD, New York

- J. Shin, MD, New York

- S. Veeramachaneni, MD, New York

- S. Yang, MD, New York

- M. Ardison, MHS, North Carolina

- M. Banks, PA, North Carolina

- W. Brooks, MD, North Carolina

- M. Chadwick, MD, North Carolina

- J. Cowen, DO, North Carolina

- S. Hewitt, North Carolina

- S. Irvin, North Carolina

- J. Kornegay, MD, North Carolina

- K. Larbi-siaw, MD, North Carolina

- J. Pavon, MD, North Carolina

- D. Warner, PA-C, North Carolina

- S. Wells, PA, North Carolina

- S. Abdel-Ghani, MD, Ohio

- D. Abhyankar, Ohio

- A. Alahmar, MD, Ohio

- A. Andreadis, MD, Ohio

- M. Bajwa, Ohio

- A. Blankenship, RN, Ohio

- M. Constantiner, RPh, Ohio

- D. Djigbenou, MD, Ohio

- S. Evans, MD, Ohio

- J. Girard, Ohio

- J. Held, MD, Ohio

- K. Hilder, MD, Ohio

- R. Kanuru, MD, Ohio

- H. Mount, Ohio

- B. Pachmayer, MD, Ohio

- C. Rodehaver, RN, MS, Ohio

- C. Schelzig, MD, FAAP, Ohio

- M. Mathews, Oklahoma

- F. Escaro, Oregon

- S. Hale, MD, Oregon

- E. Meihoff, MD, Oregon

- B. Rainka, Oregon

- A. Behura, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Bussler, Pennsylvania

- J. Chintanaboina, Pennsylvania

- I. Cirilo, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Doomra, Pennsylvania

- G. Gabasan, MD, Pennsylvania

- J. Gengaro, DO, Pennsylvania

- D. Gondek, DO, Pennsylvania

- K. Gonzalez, NP, Pennsylvania

- A. Hellyer, Pennsylvania

- J. Julian, MD, MPH, Pennsylvania

- A. Kainz, Pennsylvania

- S. Kaur, MD, Pennsylvania

- P. Lange, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Leslie, MD, Pennsylvania

- D. McBryan, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Miller, CRNP, Pennsylvania

- S. Nichuls, PA-C, Pennsylvania

- T. Pellegrino, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- K. Reed, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- A. Seasock, PA-C, BS, Pennsylvania

- S. Soenen, Pennsylvania

- V. Subbiah, MD, Pennsylvania

- N. Thingalaya, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Tuttle, PA, Pennsylvania

- G. Vadlamudi, MPH, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Verma, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Wannebo, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Wesoly, PA, Pennsylvania

- L. Eddy, FNP, Rhode Island

- M. Antonatos, MD, South Carolina

- S. Connelly, South Carolina

- D. O’Briant, MD, South Carolina

- R. Agarwal, MD, MBA, Tennessee

- A. Aird, MD, Tennessee

- F. Dragila, MD, Tennessee

- S. Duncan, MD, Tennessee

- M. Flint, MPH, Tennessee

- A. Goldfeld, Tennessee

- R. Gusso, MD, Tennessee

- S. Lane, M.H.A., Tennessee

- C. Long, MD, Tennessee

- M. Naeem, MD, PhD, Tennessee

- C. Aiken, RN, Texas

- D. Berhane, Texas

- M. Cabello, MD, Texas

- A. Caruso, MD, Texas

- P. Desai, Texas

- J. Haygood, Texas

- R. Henderson, MD, Texas

- C. Inniss, Texas

- W. Mirza, DO, Texas

- C. Moreland, MD, Texas

- N. Mulukutla, MD, Texas

- G. Neil, MD, Texas

- I. Nwabude, MD, Texas

- T. Onishi, MD, Texas

- K. Patel, MD, Texas

- B. Pomeroy, MD, Texas

- S. Ray, Texas

- J. Tau, MD, Texas

- M. Blankenship, MD, Utah

- L. Porter, RN, Utah

- J. Strong, MD, Utah

- J. Van Blarcom, MD, Utah

- A. Wood, RN, Utah

- M. Wren, Utah

- M. Anawati, MD, Vermont

- S. Lee, Vermont

- C. Cook, MD, Virginia

- E. Deungwe Yonga, MD, Virginia

- F. Dieter, PA, Virginia

- P. Gill, MD, Virginia

- S. Goldwater, PharmD, Virginia

- R. Martin, MD, Virginia

- T. Masterson, Virginia

- P. Ouellette, MD, Virginia

- M. Plazarte, DO, Virginia

- C. Salamanca, NP, Virginia

- B. Seagroves, MD, Virginia

- G. Slitt, MD, Virginia

- F. Williams, MD, Virginia

- S. Won, NP, MSN, Virginia

- L. Alberts, MD, Washington

- E. Lopez, PA-C, Washington

- L. Lubinski, MD, Washington

- J. Oconer, MD, Washington

- K. Shulman, Washington

- S. Carpenter, MD, West Virginia

- Y. Jones, FAAP, West Virginia

- P. Cartier-Neely, PA, Wisconsin

- D. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

- R. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

- E. Canady, PA, Alabama

- D. Fico, MD, Alabama

- M. Hazin, DO, Arizona

- K. Ota, DO, Arizona

- T. Phan, Arizona

- M. Poquette, RN, Arizona

- T. Imran, MD, Arkansas

- S. Wooden, MD, Arkansas

- E. Agonafer, California

- S. Badger, MHA, California

- G. Buenaflor, DO, California

- H. Cao, California

- P. Cho, California

- N. Chua, MD, California

- W. Daines, California

- B. Gavi, MD, California

- R. Grant, MD, California

- R. Greysen, MD, California

- V. Hsiao, DO, California

- M. Karube, NP, California

- A. King, MD, California

- M. La, MD, California

- M. Lam, MD, California

- T. Moinizandi, MD, California

- C. Sather, MD, California

- K. Steinberg, MD, California

- S. Woo, MHA, California

- D. Abosh, Canada

- N. Cabilio, MD, Canada

- T. Gepraegs, MD, Canada

- G. Jeffries, CCFP, Canada

- W. Mayhew, MD, Canada

- W. Wilkins, Canada

- M. Braun, ACNP, Colorado

- E. Chu, MD, Colorado

- D. Katz, Colorado

- R. Kumar, Colorado

- A. Maclennan, MD, Colorado

- P. Ryan, Colorado

- O. Akande, MD, Connecticut

- L. Colabelli, Connecticut

- S. Green, ACNP, Connecticut

- S. Lin, Connecticut

- P. Patel, MD, Connecticut

- D. Sewell, MD, Connecticut

- R. Brogan, DO, Florida

- N. Dawson, MD, FACP, Florida

- P. Dhatt, MD, Florida

- N. Griffith, MBA, Florida

- S. Hanson, MD, Florida

- M. Hernandez, MD, Florida

- J. Mennie, MD, Florida

- M. Mohiuddin, MD, Florida

- A. Moynihan, ARNP, Florida

- Y. Patel, MD, Florida

- D. Reto, Florida

- C. Reyes, ARNP, Florida

- B. Fisher, PA-C, Georgia

- S. Fleming, ANP, Georgia

- J. Gilbert, MD, Georgia

- M. Holbrook, FNP, Georgia

- S. Hung, ANP, Georgia

- N. Maignan, MD, Georgia

- P. Nanda, MD, Georgia

- H. Pei, MD, Georgia

- K. Rangnow, NP, Georgia

- S. Shams, MD, Georgia

- L. Wilson, Georgia

- E. Allen, DO, Idaho

- E. Brennan, Illinois

- K. Gul, Illinois

- L. Hansen, MD, Illinois

- D. Nguyen, MD, Illinois

- F. Porter, MD,FACP, Illinois

- A. Ranadive, Illinois

- L. Shahani, MD, Illinois

- J. Tallcott, Illinois

- K. Tulla, Illinois

- N. Wiegley, Illinois

- R. Young, MD, MS, Illinois

- D. Yu, MD, Illinois

- Z. Alba, MD, Indiana

- G. Alcorn, MD, Indiana

- K. Dorairaj, MD, Indiana

- W. Harbin, DO, Indiana

- A. Patel, MD, Indiana

- J. Shamoun, MD, Indiana

- N. Wells, MD, Indiana

- J. Wynn, USA, Indiana

- N. Hartog, MD, Iowa

- K. Emoto, Japan

- M. Sakai, MD, Japan

- P. Poddutoori, MBBS, Kansas

- T. Stofferson, ACMPE, Kansas

- B. Huneycutt, MD, Kentucky

- S. Muldoon, MD, Kentucky

- W. Travis, MD, Kentucky

- B. Molbert, NP, Louisiana

- M. Jacquet, MD, Maine

- P. Pahel, FNP, Maine

- S. Albanez, Maryland

- A. Anigbo, MBBS, Maryland

- A. Antar, PhD, Maryland

- E. Bice, DO, Maryland

- J. Clark, Maryland

- T. Hall, Maryland

- B. Huntley, PA, Maryland

- J. Kaka, Maryland

- D. Kidd, Maryland

- R. Landis, BA, Maryland

- T. Lawgaw, PA-C, Maryland

- M. Singh, Maryland

- M. Baggett, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Barkoudah, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bortinger, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Bukli, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Dhand, MD, Massachusetts

- L. DiPompo, Massachusetts

- J. Donze, MD, Massachusetts

- S. Ganatra, Massachusetts

- R. Goldberg, MD, Massachusetts

- R. Gumber, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Lawrason, MD, Massachusetts

- N. Lebaka, MD, Massachusetts

- M. Mahmoud, MD, Massachusetts

- G. Mills, Massachusetts

- M. Mohamed, MD, Massachusetts

- J. Parr, MPH, Massachusetts

- D. Ramirez, PA-C, Massachusetts

- L. Solis-Cohen, MD, Massachusetts

- C. Yu, MD, Massachusetts

- E. Bazan, Michigan

- J. Bedore, PA-C, Michigan

- P. Bradley, MD, Michigan

- L. Butz, MD, Michigan

- S. Chase, PharmD, Michigan

- A. Funk, MD, Michigan

- N. Khalid, MD, Michigan

- R. Patel, MD, Michigan

- I. Patsias, MD, Michigan

- P. Sanchez, Michigan

- D. Bowman, Minnesota

- M. Buchner, MD, Minnesota

- S. Mehmood, MD, Minnesota

- J. Ratelle, Minnesota

- M. Werpy, DO, Minnesota

- M. White, MD, Minnesota

- T. Willson, Minnesota

- H. Wood, MD, Minnesota

- S. Altmiller, Mississippi

- R. Andersson, Missouri

- K. Chuu, MD, Missouri

- M. Mullick, MD, Missouri

- C. Obi, MBBS, Missouri

- M. O’Dell, MD, Missouri

- D. Smith, MBA, Missouri

- J. Tyler, DO, Missouri

- S. Riggs, NP, Nebraska

- A. Bose, MD, New Hampshire

- F. Gaffney Comeau, New Hampshire

- C. Raymond, MSN, New Hampshire

- M. Balac, New Jersey

- A. Boa Hocbo, MD, New Jersey

- C. DeLuca, New Jersey

- P. Jadhav, MD, New Jersey

- S. Kishore, MBBS, New Jersey

- P. Krishnamoorthy, MD, New Jersey

- B. LaMotte, PharmD, New Jersey

- C. Maloy, PA-C, New Jersey

- A. Oakley, New Jersey

- K. Pratt, MD, New Jersey

- J. Yacco, New Jersey

- A. Zeff, New Jersey

- K. Caudell, PhD, New Mexico

- G. Ghuneim, MD, New Mexico

- J. Marley, DO, New Mexico

- B. Stricks, New Mexico

- L. Ahmed, New York

- G. Arora, MD, New York

- N. Bangiyeva, MD, New York

- A. Bansal, MD, New York

- L. Belletti, FACP, New York

- N. Bhatt, MPH, New York

- A. Blatt, MD, New York

- T. Chau, New York

- N. Chaudhry, MD, New York

- S. Collins, MD, New York

- L. Coryat, ANP, New York

- R. Dachs, MD, New York

- G. DeCastro, MD, New York

- J. Duffy, ANP, New York

- F. Farzan, MD, New York

- A. Gopal, MD, New York

- S. Hameed, New York

- A. Hanif, MD, New York

- A. Hassan, MD, New York

- A. Howe, New York

- M. Ip, New York

- M. Kelly, MD, New York

- S. Kovtunova, MD, New York

- J. Liu, MD, MPH, New York

- A. Maritato, MD, New York

- K. Mayer, MD, New York

- S. Mehra, New York

- K. Noshiro, MD, New York

- M. Panichas, New York

- V. Rakhvalchuk, DO, New York

- R. Ramkeesoon, New York

- M. Saluja, MD, New York

- P. Shanmugathasan, MD, New York

- S. Sherazi, MD, New York

- J. Shin, MD, New York

- S. Veeramachaneni, MD, New York

- S. Yang, MD, New York

- M. Ardison, MHS, North Carolina

- M. Banks, PA, North Carolina

- W. Brooks, MD, North Carolina

- M. Chadwick, MD, North Carolina

- J. Cowen, DO, North Carolina

- S. Hewitt, North Carolina

- S. Irvin, North Carolina

- J. Kornegay, MD, North Carolina

- K. Larbi-siaw, MD, North Carolina

- J. Pavon, MD, North Carolina

- D. Warner, PA-C, North Carolina

- S. Wells, PA, North Carolina

- S. Abdel-Ghani, MD, Ohio

- D. Abhyankar, Ohio

- A. Alahmar, MD, Ohio

- A. Andreadis, MD, Ohio

- M. Bajwa, Ohio

- A. Blankenship, RN, Ohio

- M. Constantiner, RPh, Ohio

- D. Djigbenou, MD, Ohio

- S. Evans, MD, Ohio

- J. Girard, Ohio

- J. Held, MD, Ohio

- K. Hilder, MD, Ohio

- R. Kanuru, MD, Ohio

- H. Mount, Ohio

- B. Pachmayer, MD, Ohio

- C. Rodehaver, RN, MS, Ohio

- C. Schelzig, MD, FAAP, Ohio

- M. Mathews, Oklahoma

- F. Escaro, Oregon

- S. Hale, MD, Oregon

- E. Meihoff, MD, Oregon

- B. Rainka, Oregon

- A. Behura, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Bussler, Pennsylvania

- J. Chintanaboina, Pennsylvania

- I. Cirilo, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Doomra, Pennsylvania

- G. Gabasan, MD, Pennsylvania

- J. Gengaro, DO, Pennsylvania

- D. Gondek, DO, Pennsylvania

- K. Gonzalez, NP, Pennsylvania

- A. Hellyer, Pennsylvania

- J. Julian, MD, MPH, Pennsylvania

- A. Kainz, Pennsylvania

- S. Kaur, MD, Pennsylvania

- P. Lange, MD, Pennsylvania

- S. Leslie, MD, Pennsylvania

- D. McBryan, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Miller, CRNP, Pennsylvania

- S. Nichuls, PA-C, Pennsylvania

- T. Pellegrino, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- K. Reed, PharmD, Pennsylvania

- A. Seasock, PA-C, BS, Pennsylvania

- S. Soenen, Pennsylvania

- V. Subbiah, MD, Pennsylvania

- N. Thingalaya, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Tuttle, PA, Pennsylvania

- G. Vadlamudi, MPH, MD, Pennsylvania

- B. Verma, MD, Pennsylvania

- E. Wannebo, MD, Pennsylvania

- A. Wesoly, PA, Pennsylvania

- L. Eddy, FNP, Rhode Island

- M. Antonatos, MD, South Carolina

- S. Connelly, South Carolina

- D. O’Briant, MD, South Carolina

- R. Agarwal, MD, MBA, Tennessee

- A. Aird, MD, Tennessee

- F. Dragila, MD, Tennessee

- S. Duncan, MD, Tennessee

- M. Flint, MPH, Tennessee

- A. Goldfeld, Tennessee

- R. Gusso, MD, Tennessee

- S. Lane, M.H.A., Tennessee

- C. Long, MD, Tennessee

- M. Naeem, MD, PhD, Tennessee

- C. Aiken, RN, Texas

- D. Berhane, Texas

- M. Cabello, MD, Texas

- A. Caruso, MD, Texas

- P. Desai, Texas

- J. Haygood, Texas

- R. Henderson, MD, Texas

- C. Inniss, Texas

- W. Mirza, DO, Texas

- C. Moreland, MD, Texas

- N. Mulukutla, MD, Texas

- G. Neil, MD, Texas

- I. Nwabude, MD, Texas

- T. Onishi, MD, Texas

- K. Patel, MD, Texas

- B. Pomeroy, MD, Texas

- S. Ray, Texas

- J. Tau, MD, Texas

- M. Blankenship, MD, Utah

- L. Porter, RN, Utah

- J. Strong, MD, Utah

- J. Van Blarcom, MD, Utah

- A. Wood, RN, Utah

- M. Wren, Utah

- M. Anawati, MD, Vermont

- S. Lee, Vermont

- C. Cook, MD, Virginia

- E. Deungwe Yonga, MD, Virginia

- F. Dieter, PA, Virginia

- P. Gill, MD, Virginia

- S. Goldwater, PharmD, Virginia

- R. Martin, MD, Virginia

- T. Masterson, Virginia

- P. Ouellette, MD, Virginia

- M. Plazarte, DO, Virginia

- C. Salamanca, NP, Virginia

- B. Seagroves, MD, Virginia

- G. Slitt, MD, Virginia

- F. Williams, MD, Virginia

- S. Won, NP, MSN, Virginia

- L. Alberts, MD, Washington

- E. Lopez, PA-C, Washington

- L. Lubinski, MD, Washington

- J. Oconer, MD, Washington

- K. Shulman, Washington

- S. Carpenter, MD, West Virginia

- Y. Jones, FAAP, West Virginia

- P. Cartier-Neely, PA, Wisconsin

- D. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

- R. Johnson, MD, Wisconsin

Fellow in Hospital Medicine Spotlight: Rachel Thompson, MD, FHM

Dr. Thompson is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. She is director of the medicine consult service and the medicine operative consult clinic at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. She also is president of SHM’s Pacific Northwest chapter and a member of the National Chapter Support Committee.

Undergraduate education: Amherst College, Amherst, Mass.

Medical school: University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

Notable: Dr. Thompson says one of her greatest career achievements has been the development of collegial services with surgeons and researchers in order to look at surgical outcomes through the lens of a hospitalist. She also developed a glycemic-control center in her hospital to improve insulin ordering, a project for which she has been published and presented locally and nationally. She has served as a resident research project mentor since 2005, helping 13 students achieve their research goals. Dr. Thompson volunteers at the Mathematics Engineering Science Achievement (MESA) Saturday Academy, an inner-city high school program for advancement in math and science, for which she won the 2007 MESA Saturday Academy Outstanding Volunteer Award.

FYI: Dr. Thompson enjoys hiking and takes part in two soccer leagues. Her children are following in her footsteps: Both are on their own soccer teams.

Quotable: “Becoming an SHM fellow shows that you have what it takes to be engaged as a hospitalist. Hospital medicine is not just a job; it’s a career and a dedication.”

Dr. Thompson is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. She is director of the medicine consult service and the medicine operative consult clinic at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. She also is president of SHM’s Pacific Northwest chapter and a member of the National Chapter Support Committee.

Undergraduate education: Amherst College, Amherst, Mass.

Medical school: University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

Notable: Dr. Thompson says one of her greatest career achievements has been the development of collegial services with surgeons and researchers in order to look at surgical outcomes through the lens of a hospitalist. She also developed a glycemic-control center in her hospital to improve insulin ordering, a project for which she has been published and presented locally and nationally. She has served as a resident research project mentor since 2005, helping 13 students achieve their research goals. Dr. Thompson volunteers at the Mathematics Engineering Science Achievement (MESA) Saturday Academy, an inner-city high school program for advancement in math and science, for which she won the 2007 MESA Saturday Academy Outstanding Volunteer Award.

FYI: Dr. Thompson enjoys hiking and takes part in two soccer leagues. Her children are following in her footsteps: Both are on their own soccer teams.

Quotable: “Becoming an SHM fellow shows that you have what it takes to be engaged as a hospitalist. Hospital medicine is not just a job; it’s a career and a dedication.”

Dr. Thompson is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. She is director of the medicine consult service and the medicine operative consult clinic at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. She also is president of SHM’s Pacific Northwest chapter and a member of the National Chapter Support Committee.

Undergraduate education: Amherst College, Amherst, Mass.

Medical school: University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

Notable: Dr. Thompson says one of her greatest career achievements has been the development of collegial services with surgeons and researchers in order to look at surgical outcomes through the lens of a hospitalist. She also developed a glycemic-control center in her hospital to improve insulin ordering, a project for which she has been published and presented locally and nationally. She has served as a resident research project mentor since 2005, helping 13 students achieve their research goals. Dr. Thompson volunteers at the Mathematics Engineering Science Achievement (MESA) Saturday Academy, an inner-city high school program for advancement in math and science, for which she won the 2007 MESA Saturday Academy Outstanding Volunteer Award.

FYI: Dr. Thompson enjoys hiking and takes part in two soccer leagues. Her children are following in her footsteps: Both are on their own soccer teams.

Quotable: “Becoming an SHM fellow shows that you have what it takes to be engaged as a hospitalist. Hospital medicine is not just a job; it’s a career and a dedication.”

Start Planning Now for HM14

Whether you couldn’t make it to HM13 or you’re bringing back all the energy from the conference back to your hospital, now is the time to start planning for the next national conference exclusively designed for the nation’s 40,000 hospitalists.

For newcomers, HM14 will offer unprecedented access, networking, and CME-accredited educational sessions for hospitalists in all career stages. And for veterans of SHM’s annual meeting, 2014 will introduce two new pre-courses: “Cardiology and Evidence-Based Medicine” and “Bending the Cost Curve,” one of the hottest topics in public health, which will have its own dedicated track as well.

In addition to offering the best CME-accredited educational experience, HM14 will also give hospitalists the chance to enjoy an all-new official headquarters for the meeting: Mandalay Bay Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.

Pre-Courses

Enhance the HM14 educational experience, broaden your skills, and earn additional CME credits. Choose from one of the following HM-focused topics:

- Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist;

- Portable Ultrasound for the Hospitalist;

- Perioperative Medicine;

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification;

- Practice Management;

- Neurology;

- Cardiology (new); and

- Evidence-Based Medicine (new).

Content Areas

The educational tracks offered at HM14 enable attendees to take courses in various designated tracks designed to better focus and enrich the annual meeting for attendees.

Tracks focus on the following cutting-edge content areas:

- Clinical;

- Rapid Fire;

- Practice Management;

- Academic/Research;

- Quality;

- Bending the Cost Curve (new);

- Pediatric;

- Potpourri;

- Comanagement; and

- Workshops.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Whether you couldn’t make it to HM13 or you’re bringing back all the energy from the conference back to your hospital, now is the time to start planning for the next national conference exclusively designed for the nation’s 40,000 hospitalists.

For newcomers, HM14 will offer unprecedented access, networking, and CME-accredited educational sessions for hospitalists in all career stages. And for veterans of SHM’s annual meeting, 2014 will introduce two new pre-courses: “Cardiology and Evidence-Based Medicine” and “Bending the Cost Curve,” one of the hottest topics in public health, which will have its own dedicated track as well.

In addition to offering the best CME-accredited educational experience, HM14 will also give hospitalists the chance to enjoy an all-new official headquarters for the meeting: Mandalay Bay Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.

Pre-Courses

Enhance the HM14 educational experience, broaden your skills, and earn additional CME credits. Choose from one of the following HM-focused topics:

- Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist;

- Portable Ultrasound for the Hospitalist;

- Perioperative Medicine;

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification;

- Practice Management;

- Neurology;

- Cardiology (new); and

- Evidence-Based Medicine (new).

Content Areas

The educational tracks offered at HM14 enable attendees to take courses in various designated tracks designed to better focus and enrich the annual meeting for attendees.

Tracks focus on the following cutting-edge content areas:

- Clinical;

- Rapid Fire;

- Practice Management;

- Academic/Research;

- Quality;

- Bending the Cost Curve (new);

- Pediatric;

- Potpourri;

- Comanagement; and

- Workshops.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Whether you couldn’t make it to HM13 or you’re bringing back all the energy from the conference back to your hospital, now is the time to start planning for the next national conference exclusively designed for the nation’s 40,000 hospitalists.

For newcomers, HM14 will offer unprecedented access, networking, and CME-accredited educational sessions for hospitalists in all career stages. And for veterans of SHM’s annual meeting, 2014 will introduce two new pre-courses: “Cardiology and Evidence-Based Medicine” and “Bending the Cost Curve,” one of the hottest topics in public health, which will have its own dedicated track as well.

In addition to offering the best CME-accredited educational experience, HM14 will also give hospitalists the chance to enjoy an all-new official headquarters for the meeting: Mandalay Bay Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.

Pre-Courses

Enhance the HM14 educational experience, broaden your skills, and earn additional CME credits. Choose from one of the following HM-focused topics:

- Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist;

- Portable Ultrasound for the Hospitalist;

- Perioperative Medicine;

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification;

- Practice Management;

- Neurology;

- Cardiology (new); and

- Evidence-Based Medicine (new).

Content Areas

The educational tracks offered at HM14 enable attendees to take courses in various designated tracks designed to better focus and enrich the annual meeting for attendees.

Tracks focus on the following cutting-edge content areas:

- Clinical;

- Rapid Fire;

- Practice Management;

- Academic/Research;

- Quality;

- Bending the Cost Curve (new);

- Pediatric;

- Potpourri;

- Comanagement; and

- Workshops.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

RIV Presenters at HM13 Explore Common Hospitalist Concerns

Two oral research poster presentations at HM13 explored malpractice concerns of hospitalists and the issue of defensive-medicine-related overutilization—popular topics considering how policymakers are attempting to bend the cost curve in the direction of greater efficiency and value.

Hospitalist Alan Kachalia, MD, JD, and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston conducted a randomized national survey of 1,020 hospitalists and analyzed their responses to common clinical scenarios. They found evidence of inappropriate overutilization and deviance from scientific evidence or recognized treatment guidelines, which the research team pegged to the practice of defensive medicine.

Dr. Kachalia’s presentation, “Overutilization and Defensive Medicine in U.S. Hospitals: A Randomized National Survey of Hospitalists,” was named best of the oral presentations in the research category.

“Our survey found substantial overutilization, frequently caused by defensive medicine,” in response to questions about practice patterns for two common clinical scenarios: preoperative evaluation and syncope, Dr. Kachalia said. Physicians who practiced at Veterans Affairs medical centers had less association with defensive medicine, while those who paid for their own liability insurance reported more. Overall, defensive medicine was reported for 37% of preoperative evaluations and 58% of the syncope scenarios.

More than 800 abstracts were submitted for HM13’s Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition. Nearly 600 were accepted, put on display at the annual meeting, and published online (www.shmabstracts.com). More than 100 abstracts were judged, with 15 of the Research and Innovations entries invited to make oral presentations of their projects. Three others gave “Best of RIV” plenary presentations at the conference.

The diversity and richness of HM13’s oral and poster presentations also will be highlighted in the Innovations department of The Hospitalist over the next year.

Asked to suggest policy responses to these findings, Dr. Kachalia said reform of the malpractice system is needed. “What a lot of us argue is that to get physicians to follow treatment guidelines, make them more clear and practical,” he said. “We’d also like to see safe harbors [from lawsuits] for following recognized guidelines.”

Adam Schaffer, MD, also a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues reviewed a medical liability insurance carrier’s database of more than 30,000 closed claims for those in which a hospitalist was the attending of record. Dr. Schaffer’s retrospective, observational analysis, “Medical Malpractice: Causes and Outcomes of Claims Against Hospitalists,” of the claims database from 1997 to 2011 found 272 claims—almost 1%—for which the attending was a hospitalist.

“The claims rate was almost four times lower for hospitalists than for nonhospitalist internal-medicine physicians,” he said.

The average payment for claims against hospitalists also was smaller. He noted that the types of claims were similar and tended to fall in three general categories: errors in medical treatment, missed or delayed diagnoses, and medication-related errors (although claims also tended to have multiple contributing factors).

Research like Dr. Schaffer’s could help to inform patient-safety efforts and reduce legal malpractice risk, he said. If hospitalists have fewer malpractice claims, that information might also be used to argue for lower malpractice premium rates.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Two oral research poster presentations at HM13 explored malpractice concerns of hospitalists and the issue of defensive-medicine-related overutilization—popular topics considering how policymakers are attempting to bend the cost curve in the direction of greater efficiency and value.

Hospitalist Alan Kachalia, MD, JD, and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston conducted a randomized national survey of 1,020 hospitalists and analyzed their responses to common clinical scenarios. They found evidence of inappropriate overutilization and deviance from scientific evidence or recognized treatment guidelines, which the research team pegged to the practice of defensive medicine.

Dr. Kachalia’s presentation, “Overutilization and Defensive Medicine in U.S. Hospitals: A Randomized National Survey of Hospitalists,” was named best of the oral presentations in the research category.

“Our survey found substantial overutilization, frequently caused by defensive medicine,” in response to questions about practice patterns for two common clinical scenarios: preoperative evaluation and syncope, Dr. Kachalia said. Physicians who practiced at Veterans Affairs medical centers had less association with defensive medicine, while those who paid for their own liability insurance reported more. Overall, defensive medicine was reported for 37% of preoperative evaluations and 58% of the syncope scenarios.

More than 800 abstracts were submitted for HM13’s Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition. Nearly 600 were accepted, put on display at the annual meeting, and published online (www.shmabstracts.com). More than 100 abstracts were judged, with 15 of the Research and Innovations entries invited to make oral presentations of their projects. Three others gave “Best of RIV” plenary presentations at the conference.

The diversity and richness of HM13’s oral and poster presentations also will be highlighted in the Innovations department of The Hospitalist over the next year.

Asked to suggest policy responses to these findings, Dr. Kachalia said reform of the malpractice system is needed. “What a lot of us argue is that to get physicians to follow treatment guidelines, make them more clear and practical,” he said. “We’d also like to see safe harbors [from lawsuits] for following recognized guidelines.”

Adam Schaffer, MD, also a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues reviewed a medical liability insurance carrier’s database of more than 30,000 closed claims for those in which a hospitalist was the attending of record. Dr. Schaffer’s retrospective, observational analysis, “Medical Malpractice: Causes and Outcomes of Claims Against Hospitalists,” of the claims database from 1997 to 2011 found 272 claims—almost 1%—for which the attending was a hospitalist.

“The claims rate was almost four times lower for hospitalists than for nonhospitalist internal-medicine physicians,” he said.

The average payment for claims against hospitalists also was smaller. He noted that the types of claims were similar and tended to fall in three general categories: errors in medical treatment, missed or delayed diagnoses, and medication-related errors (although claims also tended to have multiple contributing factors).

Research like Dr. Schaffer’s could help to inform patient-safety efforts and reduce legal malpractice risk, he said. If hospitalists have fewer malpractice claims, that information might also be used to argue for lower malpractice premium rates.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Two oral research poster presentations at HM13 explored malpractice concerns of hospitalists and the issue of defensive-medicine-related overutilization—popular topics considering how policymakers are attempting to bend the cost curve in the direction of greater efficiency and value.

Hospitalist Alan Kachalia, MD, JD, and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston conducted a randomized national survey of 1,020 hospitalists and analyzed their responses to common clinical scenarios. They found evidence of inappropriate overutilization and deviance from scientific evidence or recognized treatment guidelines, which the research team pegged to the practice of defensive medicine.

Dr. Kachalia’s presentation, “Overutilization and Defensive Medicine in U.S. Hospitals: A Randomized National Survey of Hospitalists,” was named best of the oral presentations in the research category.

“Our survey found substantial overutilization, frequently caused by defensive medicine,” in response to questions about practice patterns for two common clinical scenarios: preoperative evaluation and syncope, Dr. Kachalia said. Physicians who practiced at Veterans Affairs medical centers had less association with defensive medicine, while those who paid for their own liability insurance reported more. Overall, defensive medicine was reported for 37% of preoperative evaluations and 58% of the syncope scenarios.

More than 800 abstracts were submitted for HM13’s Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition. Nearly 600 were accepted, put on display at the annual meeting, and published online (www.shmabstracts.com). More than 100 abstracts were judged, with 15 of the Research and Innovations entries invited to make oral presentations of their projects. Three others gave “Best of RIV” plenary presentations at the conference.

The diversity and richness of HM13’s oral and poster presentations also will be highlighted in the Innovations department of The Hospitalist over the next year.

Asked to suggest policy responses to these findings, Dr. Kachalia said reform of the malpractice system is needed. “What a lot of us argue is that to get physicians to follow treatment guidelines, make them more clear and practical,” he said. “We’d also like to see safe harbors [from lawsuits] for following recognized guidelines.”

Adam Schaffer, MD, also a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues reviewed a medical liability insurance carrier’s database of more than 30,000 closed claims for those in which a hospitalist was the attending of record. Dr. Schaffer’s retrospective, observational analysis, “Medical Malpractice: Causes and Outcomes of Claims Against Hospitalists,” of the claims database from 1997 to 2011 found 272 claims—almost 1%—for which the attending was a hospitalist.

“The claims rate was almost four times lower for hospitalists than for nonhospitalist internal-medicine physicians,” he said.

The average payment for claims against hospitalists also was smaller. He noted that the types of claims were similar and tended to fall in three general categories: errors in medical treatment, missed or delayed diagnoses, and medication-related errors (although claims also tended to have multiple contributing factors).

Research like Dr. Schaffer’s could help to inform patient-safety efforts and reduce legal malpractice risk, he said. If hospitalists have fewer malpractice claims, that information might also be used to argue for lower malpractice premium rates.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Hospitalists Share Information, Insights Through RIV Posters at HM13

One of the busiest times of HM13—and, come to think of it, every recent annual meeting—is the poster session for the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition. This year, more than 800 abstracts were submitted and reviewed, with nearly 600 being accepted for presentation at HM13. That meant thousands of hospitalists thumbtacking posters to rows and rows of portable bulletin boards in the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center’s massive exhibit hall.

With all those posters and accompanying oral presentations, it’s impossible for RIV judges to chat with everybody, so they choose finalists based on the abstracts, then listen to quick-hit summaries before choosing a winner on site. And meeting attendees are just as strapped for time, so they do the best they can to see as many posters as they can, taking time to network with old connections and make new ones.

So with all the limitations on how many people will interact with your poster, the small chance of winning Best in Show, and the hundreds of work hours that go into a poster presentation, why do it?

“To share is what I think is really important,” says Todd Hecht, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “If you don’t let other people know what you’re doing, they can’t bring it to their institutions, nor can you learn from others and bring their innovations to your own hospital.”

Dr. Hecht, director of the Anticoagulation Management Center and Anticoagulation Management Program at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, takes the poster sessions very seriously. This year, he entered a poster in both the Innovations and Vignette categories. His Innovations poster, “Impact of a Multidisciplinary Safety Checklist on the Rate of Preventable Hospital Complications and Standardization of Care,” was a finalist.

That meant that, at the very least, he’d be able to explain to at least two judges what motivated his research team’s project. And what was the inspiration? A 90-year-old male patient with metastatic melanoma who, in the fall of 2011, refused to take medication for VTE prophylaxis, as lesions on his skin made the process rather painful. After refusing the doses for a bit, though, the high-risk patient unsurprisingly developed a pulmonary embolism (PE).

The man survived the PE, but Dr. Hecht and his colleagues began to wonder how many patients refuse VTE prophylaxis. So they investigated, and it turned out that from December 2010 to February 2011, 26.4% of the prescribed doses of prophylaxis on the medicine floors they studied were missed. Moreover, nearly 80% of all missed doses on the medicine floors were due to patient refusal.

“It was astonishing to me that it was that high,” Dr. Hecht says. “If there were 1,000 doses in a month, 260 of them were not being given—and 205 of them were not given because they were refused.”

Checklist Integration

So Dr. Hecht and colleagues set out to create a checklist that could be used daily on multidisciplinary rounds to help reduce the risk of VTE. First question on the list: Has prophylaxis been ordered, and if so, is the patient refusing it? Knowing that patients are “refusing” medication can lead to discussions about why that is happening, which in turn can lead to ways to convince the patient that the preventative measure is a good idea.

Dr. Hecht says the team also realized a checklist creates the opportunity to improve other quality metrics, such as hospital-associated infections (HAIs). Two questions on the checklist ask whether indwelling urinary catheters (IUCs) and central venous catheters (CVCs) can be removed. Two questions ask if telemetry can be stopped and whether there are any pain-management concerns. A final query asks whether there are any nursing, social work, or discharge-related questions—a step that, according to Dr. Hecht, loops the entire multidisciplinary team into the care-plan discussion.

“An ongoing challenge is making sure it’s not just questions being asked and being answered by rote,” Dr. Hecht says. “Just pause and think for just a second for each question. You can get through the checklist in 10 seconds, but you can’t go through the checklist in two seconds.”

The project’s results are what made it a finalist. After the checklist intervention, the number of missed doses of VTE prophylaxis plummeted 59% to just 10.9% (P<0.001) from September to November 2012; the number of “patient refused” doses dropped to 6.3% (P<0.001).

Not only was Dr. Hecht caught off guard by his findings, but so were the judges who visited his poster—Mangla Gulati, MD, FHM, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Rachel George, MD, MBA, FHM, of Cogent HMG.

“I wonder if it’s like that in every hospital,” Dr. George says. “I’d like to know.”

The positive reaction and feedback to Dr. Hecht’s poster, however, was not enough to win the Innovations category. That honor went to “SEPTRIS: Improving Sepsis Recognition and Management Through a Mobile Educational Game,” which was developed by a team of researchers at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. The video game

(http://med.stanford.edu/septris/)—a mashup of sepsis and the once-popular Tetris puzzle game—already has been played 17,000 times and is on its way to being shared in other languages.

“Win or lose, it doesn’t matter,” Dr. Hecht says. “The goal is to share your information with other people and learn from them.”

Peter Watson, MD, FACP, FHM, sees it the same way. That’s why this year he was both judge and judged. The division head of hospital medicine for Henry Ford Medical Group in Detroit was part of a group presenting “Feasibility and Efficacy of a Specialized Pilot Training Program to Enhance Inpatient Communication Skills of Hospitalists.” He was a judge for the Research portion of the contest. He says he’s hard-pressed to say which process he enjoyed more, but one trick of the poster trade he passes along is that “judging actually makes you a better presenter on the back end,” especially when it comes to describing in less than five minutes a poster whose work may date back 12 to 18 months.

“In your brain,” he says, “you have a Tolstoy novel of information, but you have to break that down into a paragraph of CliffsNotes, and actually convince the people that are judging you that you have a really cool project that either is going to have a big impact in the field or may lead to other big studies or is going to impress somebody so much that they’re going to go back to their institution and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to do that.’”

Dr. Watson also urges people not to be discouraged by not winning the poster contest. First, all of the accepted abstracts get published online (www.shmabstracts.com) by the Journal of Hospital Medicine, a high point for medical students, residents, and early-career physicians looking to make a mark. Second, presenting information of value to one’s peers is the definition of a specialty that prides itself on collaboration.

“To see a second-year medical student presenting all the way up to a very senior division chief and everything in between is a really good example for our profession,” he says. “That’s really the magic of this meeting.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

One of the busiest times of HM13—and, come to think of it, every recent annual meeting—is the poster session for the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition. This year, more than 800 abstracts were submitted and reviewed, with nearly 600 being accepted for presentation at HM13. That meant thousands of hospitalists thumbtacking posters to rows and rows of portable bulletin boards in the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center’s massive exhibit hall.

With all those posters and accompanying oral presentations, it’s impossible for RIV judges to chat with everybody, so they choose finalists based on the abstracts, then listen to quick-hit summaries before choosing a winner on site. And meeting attendees are just as strapped for time, so they do the best they can to see as many posters as they can, taking time to network with old connections and make new ones.

So with all the limitations on how many people will interact with your poster, the small chance of winning Best in Show, and the hundreds of work hours that go into a poster presentation, why do it?

“To share is what I think is really important,” says Todd Hecht, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “If you don’t let other people know what you’re doing, they can’t bring it to their institutions, nor can you learn from others and bring their innovations to your own hospital.”

Dr. Hecht, director of the Anticoagulation Management Center and Anticoagulation Management Program at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, takes the poster sessions very seriously. This year, he entered a poster in both the Innovations and Vignette categories. His Innovations poster, “Impact of a Multidisciplinary Safety Checklist on the Rate of Preventable Hospital Complications and Standardization of Care,” was a finalist.

That meant that, at the very least, he’d be able to explain to at least two judges what motivated his research team’s project. And what was the inspiration? A 90-year-old male patient with metastatic melanoma who, in the fall of 2011, refused to take medication for VTE prophylaxis, as lesions on his skin made the process rather painful. After refusing the doses for a bit, though, the high-risk patient unsurprisingly developed a pulmonary embolism (PE).

The man survived the PE, but Dr. Hecht and his colleagues began to wonder how many patients refuse VTE prophylaxis. So they investigated, and it turned out that from December 2010 to February 2011, 26.4% of the prescribed doses of prophylaxis on the medicine floors they studied were missed. Moreover, nearly 80% of all missed doses on the medicine floors were due to patient refusal.

“It was astonishing to me that it was that high,” Dr. Hecht says. “If there were 1,000 doses in a month, 260 of them were not being given—and 205 of them were not given because they were refused.”

Checklist Integration

So Dr. Hecht and colleagues set out to create a checklist that could be used daily on multidisciplinary rounds to help reduce the risk of VTE. First question on the list: Has prophylaxis been ordered, and if so, is the patient refusing it? Knowing that patients are “refusing” medication can lead to discussions about why that is happening, which in turn can lead to ways to convince the patient that the preventative measure is a good idea.

Dr. Hecht says the team also realized a checklist creates the opportunity to improve other quality metrics, such as hospital-associated infections (HAIs). Two questions on the checklist ask whether indwelling urinary catheters (IUCs) and central venous catheters (CVCs) can be removed. Two questions ask if telemetry can be stopped and whether there are any pain-management concerns. A final query asks whether there are any nursing, social work, or discharge-related questions—a step that, according to Dr. Hecht, loops the entire multidisciplinary team into the care-plan discussion.

“An ongoing challenge is making sure it’s not just questions being asked and being answered by rote,” Dr. Hecht says. “Just pause and think for just a second for each question. You can get through the checklist in 10 seconds, but you can’t go through the checklist in two seconds.”

The project’s results are what made it a finalist. After the checklist intervention, the number of missed doses of VTE prophylaxis plummeted 59% to just 10.9% (P<0.001) from September to November 2012; the number of “patient refused” doses dropped to 6.3% (P<0.001).

Not only was Dr. Hecht caught off guard by his findings, but so were the judges who visited his poster—Mangla Gulati, MD, FHM, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Rachel George, MD, MBA, FHM, of Cogent HMG.

“I wonder if it’s like that in every hospital,” Dr. George says. “I’d like to know.”

The positive reaction and feedback to Dr. Hecht’s poster, however, was not enough to win the Innovations category. That honor went to “SEPTRIS: Improving Sepsis Recognition and Management Through a Mobile Educational Game,” which was developed by a team of researchers at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. The video game

(http://med.stanford.edu/septris/)—a mashup of sepsis and the once-popular Tetris puzzle game—already has been played 17,000 times and is on its way to being shared in other languages.

“Win or lose, it doesn’t matter,” Dr. Hecht says. “The goal is to share your information with other people and learn from them.”

Peter Watson, MD, FACP, FHM, sees it the same way. That’s why this year he was both judge and judged. The division head of hospital medicine for Henry Ford Medical Group in Detroit was part of a group presenting “Feasibility and Efficacy of a Specialized Pilot Training Program to Enhance Inpatient Communication Skills of Hospitalists.” He was a judge for the Research portion of the contest. He says he’s hard-pressed to say which process he enjoyed more, but one trick of the poster trade he passes along is that “judging actually makes you a better presenter on the back end,” especially when it comes to describing in less than five minutes a poster whose work may date back 12 to 18 months.

“In your brain,” he says, “you have a Tolstoy novel of information, but you have to break that down into a paragraph of CliffsNotes, and actually convince the people that are judging you that you have a really cool project that either is going to have a big impact in the field or may lead to other big studies or is going to impress somebody so much that they’re going to go back to their institution and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to do that.’”

Dr. Watson also urges people not to be discouraged by not winning the poster contest. First, all of the accepted abstracts get published online (www.shmabstracts.com) by the Journal of Hospital Medicine, a high point for medical students, residents, and early-career physicians looking to make a mark. Second, presenting information of value to one’s peers is the definition of a specialty that prides itself on collaboration.

“To see a second-year medical student presenting all the way up to a very senior division chief and everything in between is a really good example for our profession,” he says. “That’s really the magic of this meeting.”