User login

Who Should Run Our Hospitals?

Over the past century, the management of American hospitals has changed dramatically. These changes have occurred as a result of major shifts in the social and financial environment and have had a major effect on how medicine was practiced in the past and how it will be practiced in the future.

The American hospital as we know it today was established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries largely by the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish communities to provide care for the elderly and chronically ill patients who otherwise would not be cared for at home.

With the development of surgical techniques from tonsillectomies to cholecystectomies in the mid-20th century, they became the workshop of general surgeons, who largely controlled the hospitals. With the subsequent development of antibiotics and medical treatment for cardiovascular disease, the internal medicine specialties demanded a larger role in institutional management.

The increased complexity and expense of medical care led to concerns about how to provide a financial base for medical care and led to the establishment of private medical insurance programs, and ultimately, to Medicare and Medicaid. Hospitals were no longer concerned about being a health resource but suddenly became a profit center. Community hospitals expanded in order to meet the needs of new technologies with the support of grants and loans from the federal government.

With this growth, the management of the hospital of the 20th century required the creation of a new breed of hospital staff: the hospital administrator. They were hired to manage the financial and administrative aspects of these new and growing organizations. Although the hospital administration was structured to provide equipoise between the medical and financial priorities of the hospital, that balance was not easily maintained, and as the financial aspects became central, the hospital administrator became supreme and physicians lost control.

Today, the American hospital has become central to the support of nonprofit and for-profit regional and national health care conglomerates, and control has become the province of boards of directors with little medical input and larger community control. As a consequence, the physician has now become a real or quasi-employee of the hospital.

In a recent perspective paper, Dr. Richard Gunderson (Acad. Med. 2009;84:1348-51) emphasizes the need to train physicians to provide leadership for the future management of the hospital. He points out that in 1935, physicians were in charge of 35% of the nation's hospitals, but that number has shrunk to 4% of our current 6,500 U.S. hospitals. The academic medical community has largely ignored its role in preparing medical students for administrative leadership as it focused on the clinical knowledge required for the medical competence.

Dr. Gunderson, of Indiana University in Indianapolis, advocates the identification of student leaders in the selection of medical students and proposes the inclusion of courses in medical finance and social issues in the medical school curriculum in order to prepare them for a leadership role in redefining the future of medical care and hospital management.

Amanda Goodall, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn, Germany, provides an even more challenging analysis of the importance of medical leadership at the hospital (Social Science Med. 2011;73:535-9). She notes that these changes in leadership are not unique to the United States but also have taken place in European hospitals. Using a quality scoring system, she analyzed the quality performance of 100 of the U.S. News and World Report's Best Hospitals 2009 in the fields of cancer, digestive disorders, and heart and heart surgery. She found a positive correlation between hospital quality ranking and physician CEO leadership.

Those of us who have grown up through this management evolution have seen its real impact on the care of hospital patients. Some of the changes have been positive, while others have proved frustrating for both patients and physicians who practice in the new environment.

The need for leadership by those of us who have direct patient care responsibilities is essential for an inclusive decision-making process. When patient care comes to discussion at the board meeting, physicians and nurses bring to the process a perspective that only they can provide. It is essential that their voices be heard.

Over the past century, the management of American hospitals has changed dramatically. These changes have occurred as a result of major shifts in the social and financial environment and have had a major effect on how medicine was practiced in the past and how it will be practiced in the future.

The American hospital as we know it today was established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries largely by the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish communities to provide care for the elderly and chronically ill patients who otherwise would not be cared for at home.

With the development of surgical techniques from tonsillectomies to cholecystectomies in the mid-20th century, they became the workshop of general surgeons, who largely controlled the hospitals. With the subsequent development of antibiotics and medical treatment for cardiovascular disease, the internal medicine specialties demanded a larger role in institutional management.

The increased complexity and expense of medical care led to concerns about how to provide a financial base for medical care and led to the establishment of private medical insurance programs, and ultimately, to Medicare and Medicaid. Hospitals were no longer concerned about being a health resource but suddenly became a profit center. Community hospitals expanded in order to meet the needs of new technologies with the support of grants and loans from the federal government.

With this growth, the management of the hospital of the 20th century required the creation of a new breed of hospital staff: the hospital administrator. They were hired to manage the financial and administrative aspects of these new and growing organizations. Although the hospital administration was structured to provide equipoise between the medical and financial priorities of the hospital, that balance was not easily maintained, and as the financial aspects became central, the hospital administrator became supreme and physicians lost control.

Today, the American hospital has become central to the support of nonprofit and for-profit regional and national health care conglomerates, and control has become the province of boards of directors with little medical input and larger community control. As a consequence, the physician has now become a real or quasi-employee of the hospital.

In a recent perspective paper, Dr. Richard Gunderson (Acad. Med. 2009;84:1348-51) emphasizes the need to train physicians to provide leadership for the future management of the hospital. He points out that in 1935, physicians were in charge of 35% of the nation's hospitals, but that number has shrunk to 4% of our current 6,500 U.S. hospitals. The academic medical community has largely ignored its role in preparing medical students for administrative leadership as it focused on the clinical knowledge required for the medical competence.

Dr. Gunderson, of Indiana University in Indianapolis, advocates the identification of student leaders in the selection of medical students and proposes the inclusion of courses in medical finance and social issues in the medical school curriculum in order to prepare them for a leadership role in redefining the future of medical care and hospital management.

Amanda Goodall, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn, Germany, provides an even more challenging analysis of the importance of medical leadership at the hospital (Social Science Med. 2011;73:535-9). She notes that these changes in leadership are not unique to the United States but also have taken place in European hospitals. Using a quality scoring system, she analyzed the quality performance of 100 of the U.S. News and World Report's Best Hospitals 2009 in the fields of cancer, digestive disorders, and heart and heart surgery. She found a positive correlation between hospital quality ranking and physician CEO leadership.

Those of us who have grown up through this management evolution have seen its real impact on the care of hospital patients. Some of the changes have been positive, while others have proved frustrating for both patients and physicians who practice in the new environment.

The need for leadership by those of us who have direct patient care responsibilities is essential for an inclusive decision-making process. When patient care comes to discussion at the board meeting, physicians and nurses bring to the process a perspective that only they can provide. It is essential that their voices be heard.

Over the past century, the management of American hospitals has changed dramatically. These changes have occurred as a result of major shifts in the social and financial environment and have had a major effect on how medicine was practiced in the past and how it will be practiced in the future.

The American hospital as we know it today was established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries largely by the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish communities to provide care for the elderly and chronically ill patients who otherwise would not be cared for at home.

With the development of surgical techniques from tonsillectomies to cholecystectomies in the mid-20th century, they became the workshop of general surgeons, who largely controlled the hospitals. With the subsequent development of antibiotics and medical treatment for cardiovascular disease, the internal medicine specialties demanded a larger role in institutional management.

The increased complexity and expense of medical care led to concerns about how to provide a financial base for medical care and led to the establishment of private medical insurance programs, and ultimately, to Medicare and Medicaid. Hospitals were no longer concerned about being a health resource but suddenly became a profit center. Community hospitals expanded in order to meet the needs of new technologies with the support of grants and loans from the federal government.

With this growth, the management of the hospital of the 20th century required the creation of a new breed of hospital staff: the hospital administrator. They were hired to manage the financial and administrative aspects of these new and growing organizations. Although the hospital administration was structured to provide equipoise between the medical and financial priorities of the hospital, that balance was not easily maintained, and as the financial aspects became central, the hospital administrator became supreme and physicians lost control.

Today, the American hospital has become central to the support of nonprofit and for-profit regional and national health care conglomerates, and control has become the province of boards of directors with little medical input and larger community control. As a consequence, the physician has now become a real or quasi-employee of the hospital.

In a recent perspective paper, Dr. Richard Gunderson (Acad. Med. 2009;84:1348-51) emphasizes the need to train physicians to provide leadership for the future management of the hospital. He points out that in 1935, physicians were in charge of 35% of the nation's hospitals, but that number has shrunk to 4% of our current 6,500 U.S. hospitals. The academic medical community has largely ignored its role in preparing medical students for administrative leadership as it focused on the clinical knowledge required for the medical competence.

Dr. Gunderson, of Indiana University in Indianapolis, advocates the identification of student leaders in the selection of medical students and proposes the inclusion of courses in medical finance and social issues in the medical school curriculum in order to prepare them for a leadership role in redefining the future of medical care and hospital management.

Amanda Goodall, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn, Germany, provides an even more challenging analysis of the importance of medical leadership at the hospital (Social Science Med. 2011;73:535-9). She notes that these changes in leadership are not unique to the United States but also have taken place in European hospitals. Using a quality scoring system, she analyzed the quality performance of 100 of the U.S. News and World Report's Best Hospitals 2009 in the fields of cancer, digestive disorders, and heart and heart surgery. She found a positive correlation between hospital quality ranking and physician CEO leadership.

Those of us who have grown up through this management evolution have seen its real impact on the care of hospital patients. Some of the changes have been positive, while others have proved frustrating for both patients and physicians who practice in the new environment.

The need for leadership by those of us who have direct patient care responsibilities is essential for an inclusive decision-making process. When patient care comes to discussion at the board meeting, physicians and nurses bring to the process a perspective that only they can provide. It is essential that their voices be heard.

Team corrects SCD mutation with iPS cells

Credit: James Thomson

Using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, researchers have corrected the genetic alteration that causes sickle cell disease (SCD).

The corrected stem cells were coaxed in vitro into immature red blood cells that then turned on a normal version of the gene.

The researchers caution that the work is years away from clinical use in patients, but it should provide tools for developing gene therapies for SCD and a variety of other hematologic disorders.

“We’re now one step closer to developing a combination cell and gene therapy method that will allow us to use patients’ own cells to treat them,” said lead study author Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Using an adult patient at The Johns Hopkins Hospital as their first case, the researchers isolated the patient’s bone marrow cells. After generating iPS cells from the bone marrow, the team put a normal copy of the hemoglobin gene in place of the defective one using genetic engineering techniques.

The researchers sequenced the DNA from 300 different samples of iPS cells to identify those that contained correct copies of the hemoglobin gene and found 4. Three of these iPS cell lines didn’t pass muster in subsequent tests.

“The beauty of iPS cells is that we can grow a lot of them and then coax them into becoming cells of any kind, including red blood cells,” Dr Cheng said.

In their process, his team converted the corrected iPS cells into immature red blood cells by giving them growth factors. Further testing showed that the normal hemoglobin gene was turned on properly in these cells, although at less than half of normal levels.

“We think these immature red blood cells still behave like embryonic cells and, as a result, are unable to turn on high enough levels of the adult hemoglobin gene,” Dr Cheng said. “We next have to learn how to properly convert these cells into mature red blood cells.”

This research was recently published online in Blood. ![]()

Credit: James Thomson

Using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, researchers have corrected the genetic alteration that causes sickle cell disease (SCD).

The corrected stem cells were coaxed in vitro into immature red blood cells that then turned on a normal version of the gene.

The researchers caution that the work is years away from clinical use in patients, but it should provide tools for developing gene therapies for SCD and a variety of other hematologic disorders.

“We’re now one step closer to developing a combination cell and gene therapy method that will allow us to use patients’ own cells to treat them,” said lead study author Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Using an adult patient at The Johns Hopkins Hospital as their first case, the researchers isolated the patient’s bone marrow cells. After generating iPS cells from the bone marrow, the team put a normal copy of the hemoglobin gene in place of the defective one using genetic engineering techniques.

The researchers sequenced the DNA from 300 different samples of iPS cells to identify those that contained correct copies of the hemoglobin gene and found 4. Three of these iPS cell lines didn’t pass muster in subsequent tests.

“The beauty of iPS cells is that we can grow a lot of them and then coax them into becoming cells of any kind, including red blood cells,” Dr Cheng said.

In their process, his team converted the corrected iPS cells into immature red blood cells by giving them growth factors. Further testing showed that the normal hemoglobin gene was turned on properly in these cells, although at less than half of normal levels.

“We think these immature red blood cells still behave like embryonic cells and, as a result, are unable to turn on high enough levels of the adult hemoglobin gene,” Dr Cheng said. “We next have to learn how to properly convert these cells into mature red blood cells.”

This research was recently published online in Blood. ![]()

Credit: James Thomson

Using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, researchers have corrected the genetic alteration that causes sickle cell disease (SCD).

The corrected stem cells were coaxed in vitro into immature red blood cells that then turned on a normal version of the gene.

The researchers caution that the work is years away from clinical use in patients, but it should provide tools for developing gene therapies for SCD and a variety of other hematologic disorders.

“We’re now one step closer to developing a combination cell and gene therapy method that will allow us to use patients’ own cells to treat them,” said lead study author Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Using an adult patient at The Johns Hopkins Hospital as their first case, the researchers isolated the patient’s bone marrow cells. After generating iPS cells from the bone marrow, the team put a normal copy of the hemoglobin gene in place of the defective one using genetic engineering techniques.

The researchers sequenced the DNA from 300 different samples of iPS cells to identify those that contained correct copies of the hemoglobin gene and found 4. Three of these iPS cell lines didn’t pass muster in subsequent tests.

“The beauty of iPS cells is that we can grow a lot of them and then coax them into becoming cells of any kind, including red blood cells,” Dr Cheng said.

In their process, his team converted the corrected iPS cells into immature red blood cells by giving them growth factors. Further testing showed that the normal hemoglobin gene was turned on properly in these cells, although at less than half of normal levels.

“We think these immature red blood cells still behave like embryonic cells and, as a result, are unable to turn on high enough levels of the adult hemoglobin gene,” Dr Cheng said. “We next have to learn how to properly convert these cells into mature red blood cells.”

This research was recently published online in Blood. ![]()

AD Myths in Healthcare Debate

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

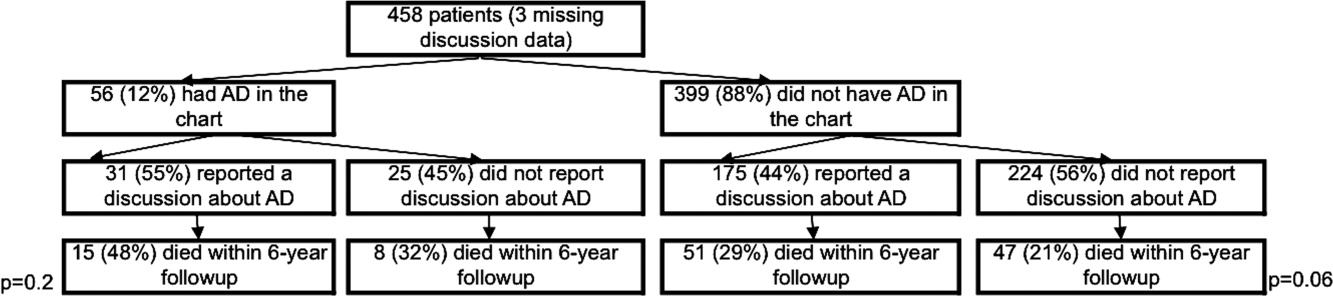

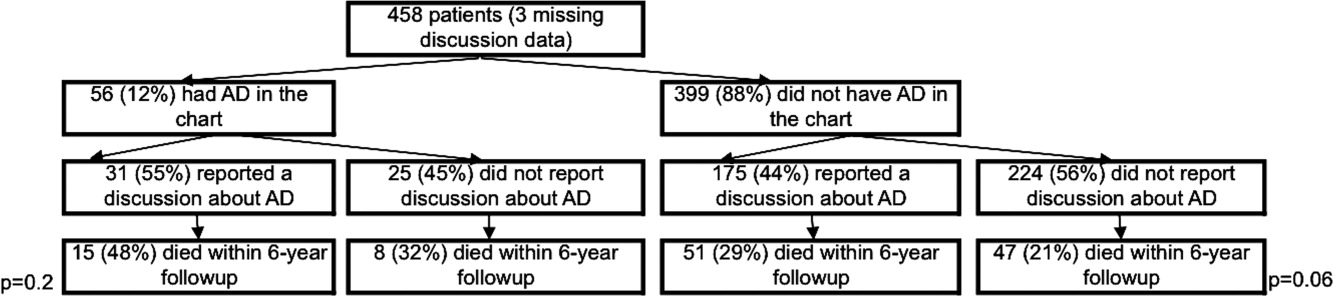

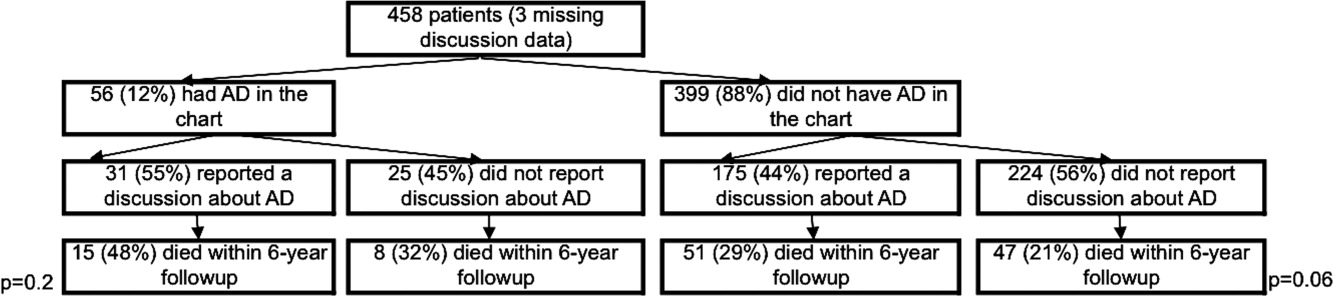

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

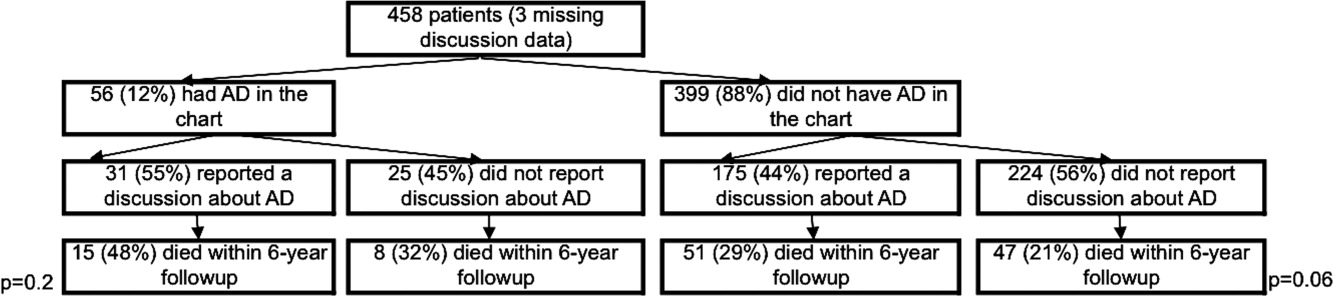

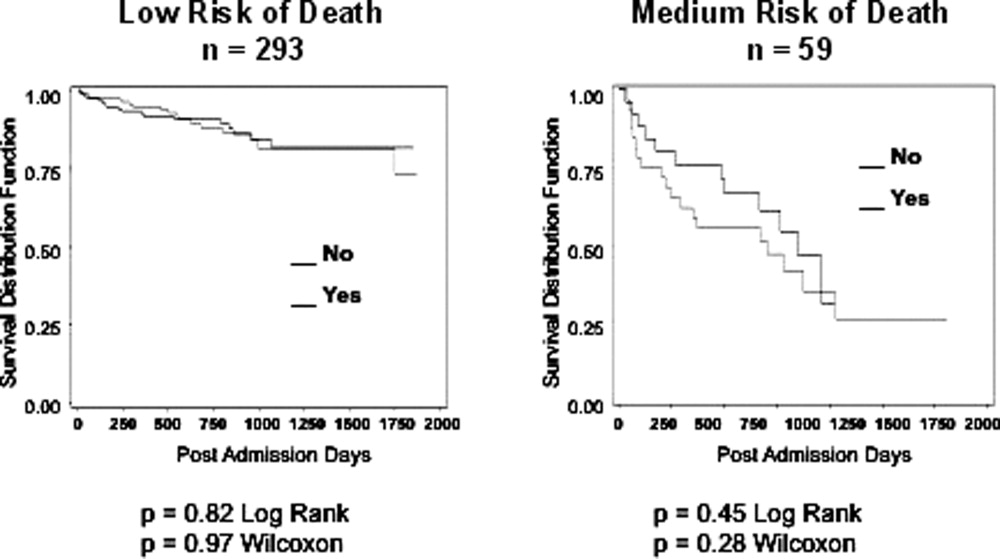

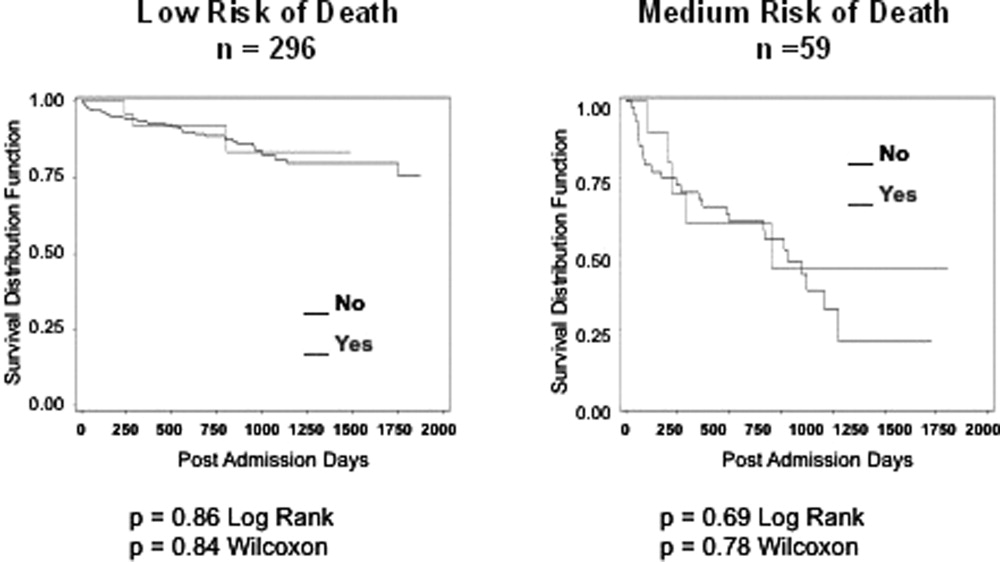

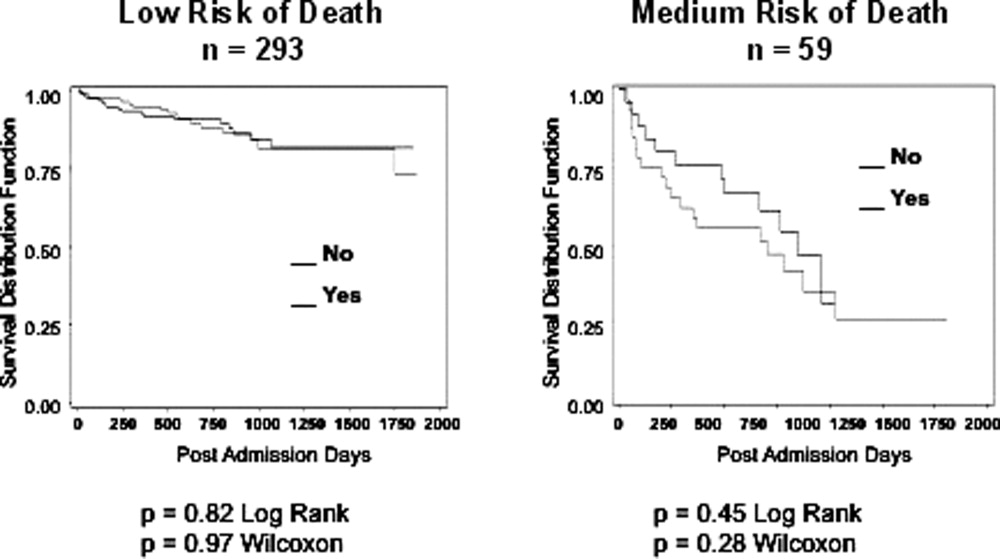

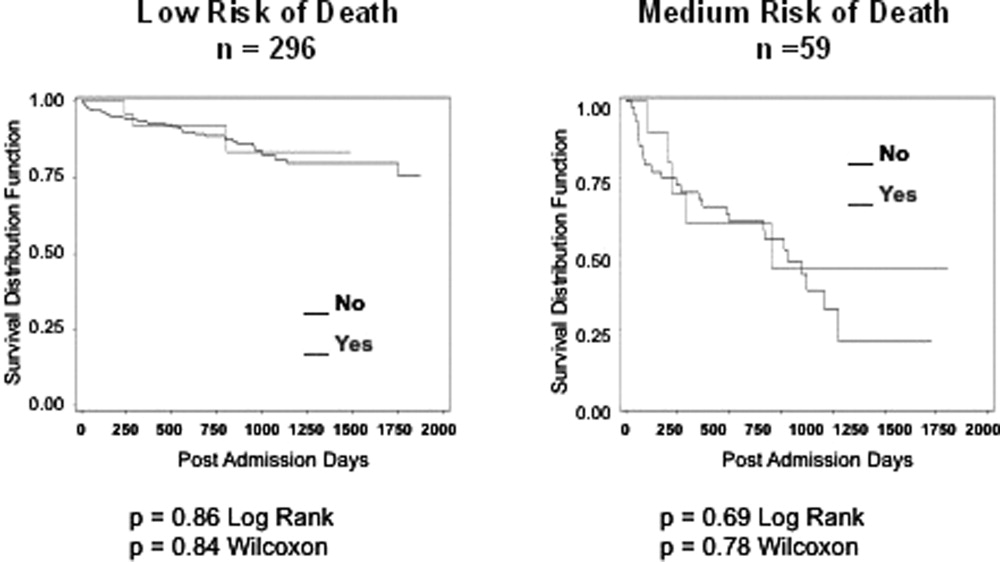

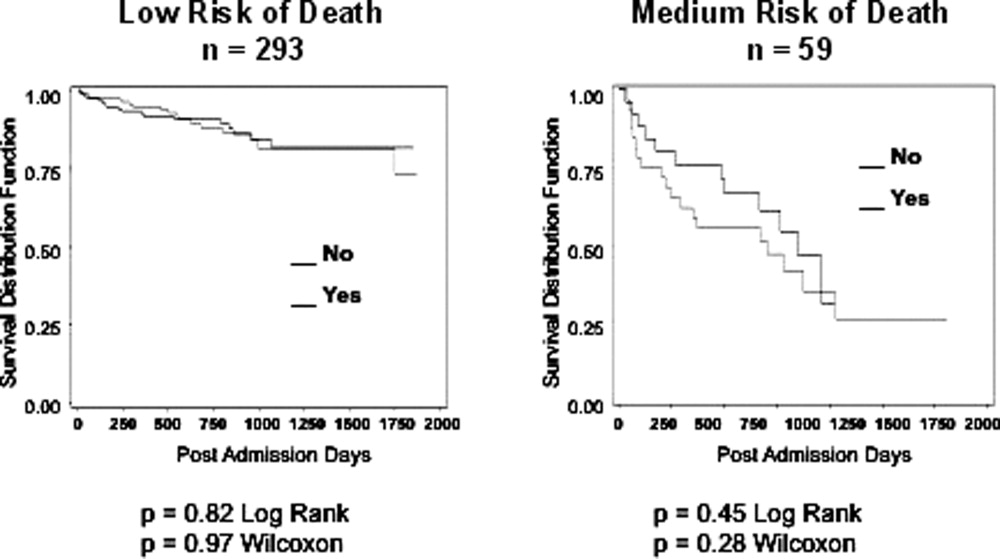

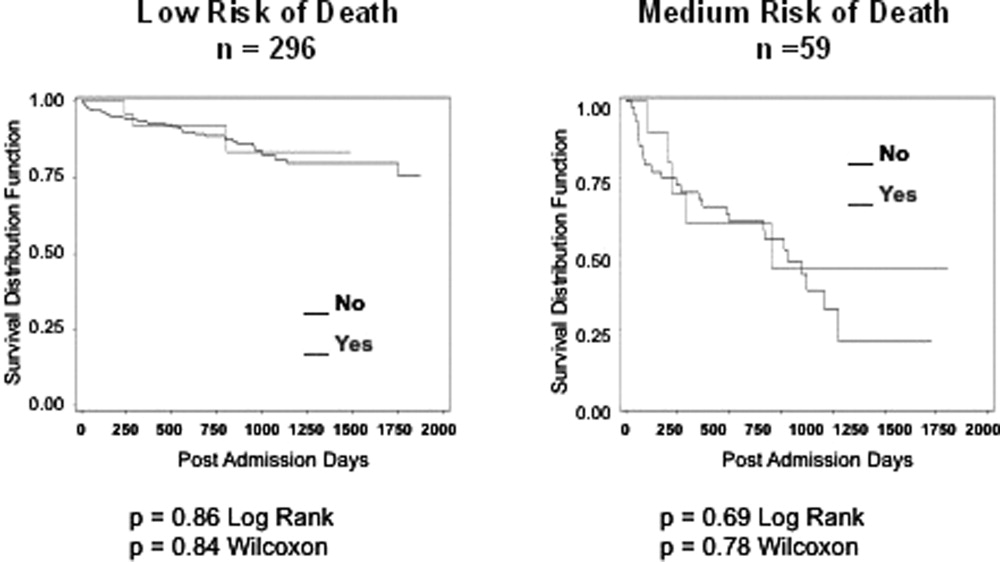

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

Tackling Readmissions Together

A new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine suggests that more than 60% of 30-day readmissions are viewed as potentially preventable by hospitalists.

The study, “Hospitalists Assess the Causes of Early Hospital Readmissions,” found that of 298 cases reviewed, 15% were deemed “preventable” by a team of 17 hospitalist reviewers at Providence Health & Services in Portland, Ore. (DOI: 10.1002/jhm.909). Another 40% were tagged as “possibly preventable,” the authors reported.

When the reviewers analyzed cases to determine what interventions could have prevented readmissions, team-based approaches were the answer much of the time, says lead author and hospitalist Douglas Koekkoek, MD. Those potential answers included earlier follow-up conversations with primary-care physicians (PCPs), palliative care-consults, and more education about home-care management.

“When a physician looks at just his locus of control, they tend to be a little pessimistic,” Dr. Koekkoek says. “When they take a systems approach ... then they gain that optimism.”

The report found that in 23% of the cases, hospitalists found that extending length of stay by a day or two could have prevented a readmission. Dr. Koekkoek says that inherent conflict?balancing the cost of every hospitalized day against keeping patients long enough to prevent readmission?is “the bread and butter of hospitalist care.”

“There is going to be a natural conflict of ‘I can’t keep people in the hospital forever,’” he adds.

Given that the federal government is likely to start reducing reimbursements for unnecessary readmissions, Dr. Koekkoek says HM groups have to view their work as one front in the battle to keep patients from returning. And that has to include outpatient physicians, patient education, and other techniques.

“The take-home is we are part of a care team,” he adds. “And the team extends beyond the hospital’s walls.”

A new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine suggests that more than 60% of 30-day readmissions are viewed as potentially preventable by hospitalists.

The study, “Hospitalists Assess the Causes of Early Hospital Readmissions,” found that of 298 cases reviewed, 15% were deemed “preventable” by a team of 17 hospitalist reviewers at Providence Health & Services in Portland, Ore. (DOI: 10.1002/jhm.909). Another 40% were tagged as “possibly preventable,” the authors reported.

When the reviewers analyzed cases to determine what interventions could have prevented readmissions, team-based approaches were the answer much of the time, says lead author and hospitalist Douglas Koekkoek, MD. Those potential answers included earlier follow-up conversations with primary-care physicians (PCPs), palliative care-consults, and more education about home-care management.

“When a physician looks at just his locus of control, they tend to be a little pessimistic,” Dr. Koekkoek says. “When they take a systems approach ... then they gain that optimism.”

The report found that in 23% of the cases, hospitalists found that extending length of stay by a day or two could have prevented a readmission. Dr. Koekkoek says that inherent conflict?balancing the cost of every hospitalized day against keeping patients long enough to prevent readmission?is “the bread and butter of hospitalist care.”

“There is going to be a natural conflict of ‘I can’t keep people in the hospital forever,’” he adds.

Given that the federal government is likely to start reducing reimbursements for unnecessary readmissions, Dr. Koekkoek says HM groups have to view their work as one front in the battle to keep patients from returning. And that has to include outpatient physicians, patient education, and other techniques.

“The take-home is we are part of a care team,” he adds. “And the team extends beyond the hospital’s walls.”