User login

Scheduling Strategies

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

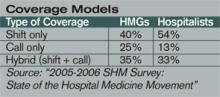

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.

Dying Wish

Most Americans surveyed about their preferred place of death say they want to die at home.1 Nevertheless, many dying people are not able to realize this wish. One 2003 study found that nearly 90% of terminally ill cancer patients asked to choose where they would prefer to die cited their homes. Only one-third of those patients were able to make this desire a reality.2

The reasons behind the divergence between preference and actual place of death are complicated, says Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, and a palliative care specialist with the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center Hospitalist Service. “I think most people envision … [dying] at home, but sometimes that’s just not feasible, for multiple reasons. When the reality sets in, there has to be a good plan in place at home—meaning, enough people and resources to keep that person at home.”

Is Death Imminent?

Dr. Bernacki points out that many studies on dying preferences are conducted when the patient is not ill or actively dying. The scenario becomes much more complex when patients are in crisis or on an end-of-life trajectory. In initial assessments, hospitalists should try not only to ascertain the patient’s health status but also to ask respectfully about their goals for care.

“It might not be appropriate [to ask] every patient, ‘Where do you want to die?’ ” suggests Dr. Bernacki. It can be appropriate, though, to ask patients about their experiences with their current illness and to talk about some of the goals they hope to achieve in the next week or month.

Although it is not possible to predict exactly how long a person will survive, the signs of critical illness can provide an appropriate window in which the physician can ask a patient, “If you were to die, where would you want to be, and what is most important to you?”

—Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, UCSF Medical Center Hospitalist Service

Practitioners skilled in end-of-life care cite several attributes characteristic of patients who are actively dying, such as:

- Refusal of food and liquids;

- Decreased level of awareness;

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath), including erratic breathing patterns;

- Mottled skin that is colder to the touch, along with blue toes; and

- Abnormal breathing sounds due to secretions in the lungs.

Honor Their Choices

Researchers cite many factors that determine whether a terminally ill cancer patient dies in the home or in an institution, including gender, race, marital status, income level, and available health system resources. In a Yale (New Haven, Conn.) epidemiological study, men, unmarried people, and those living in low-income areas were at higher risk for institutionalized deaths.3

Dr. Bernacki has found that the two most important determinants of whether a patient will go home to die are the patient’s condition and their resources at home. Sometimes transporting a patient is not practical because the patient may be so close to dying that there is a risk of death en route. Or the patient’s symptoms may not be controlled with oral pain medications and may require frequent IV dosing, in which case discharge is not feasible. Barriers at the home site include the lack of an identified primary caregiver and the unavailability of qualified hospice personnel and/or medical supplies.

For in-depth learning about palliative care topics, be sure to visit these sessions at the upcoming SHM Annual Meeting in Dallas, May 23-25:

- Palliative Pain Management: Thurs., May 24, 10:35-11:50;

- Non-Pain Symptom Management: Thurs., May 24, 1:10-2:25;

- Ethical and Legal Considerations of Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: Thurs., May 24, 2:45-4:00;

- Prognostication and PC Management of the Non-Cancer Diagnosis: Fri., May 25, 10:15-11:35; and

- Communication Skills and How to Conduct Family/Care Conferences: Fri., May 25, 1:35-2:55.

When the Hospital Is Preferred

In some situations, says Dr. Bernacki, “some family members feel very uncomfortable with the thought of their loved one dying at home.” Sometimes the disease process advances so quickly that the palliative care team cannot titrate the pain medicines to the right amount to allow discharge. Family members can become alarmed and may feel ill-prepared to handle difficult symptoms of the dying patient, such as uncontrolled nausea or dyspnea.

“So we have to just make an educated guess as to how long we think they have and how important it is to that patient or that family to be at home.” Often, the care team and family realize that it makes more sense not to move the patient but rather to try and make everything as comfortable as possible in the hospital.

The UCSF Palliative Care Service team, established by Steve Pantilat, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, has access to two in-hospital comfort care suites, where family members can stay with their loved ones at all times.4 Dr. Pantilat is also the past-president of SHM and the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care at UCSF.

In all cases, says Dr. Bernacki, hospitalists dealing with dying patients should remain cognizant that they are treating not only the patients but the family members as well. “Part of palliative care is making sure that the daughters, sons, and spouses are all well cared for,” she emphasizes. Ascertaining goals and negotiating what’s possible are the keys to good palliative care. TH

Gretchen Henkel writes frequently for The Hospitalist.

References

- Tang ST, McCorkle R, Bradley EH. Determinants of death in an inpatient hospice for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2004 Dec;2(4):361-370.

- Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:230-237.

- Gallo WT, Baker MJ, Bradley EH. Factors associated with home versus institutional death among cancer patients in Connecticut. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun;49(6):771-777. Comment in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun; 49(6):831-832.

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

Most Americans surveyed about their preferred place of death say they want to die at home.1 Nevertheless, many dying people are not able to realize this wish. One 2003 study found that nearly 90% of terminally ill cancer patients asked to choose where they would prefer to die cited their homes. Only one-third of those patients were able to make this desire a reality.2

The reasons behind the divergence between preference and actual place of death are complicated, says Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, and a palliative care specialist with the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center Hospitalist Service. “I think most people envision … [dying] at home, but sometimes that’s just not feasible, for multiple reasons. When the reality sets in, there has to be a good plan in place at home—meaning, enough people and resources to keep that person at home.”

Is Death Imminent?

Dr. Bernacki points out that many studies on dying preferences are conducted when the patient is not ill or actively dying. The scenario becomes much more complex when patients are in crisis or on an end-of-life trajectory. In initial assessments, hospitalists should try not only to ascertain the patient’s health status but also to ask respectfully about their goals for care.

“It might not be appropriate [to ask] every patient, ‘Where do you want to die?’ ” suggests Dr. Bernacki. It can be appropriate, though, to ask patients about their experiences with their current illness and to talk about some of the goals they hope to achieve in the next week or month.

Although it is not possible to predict exactly how long a person will survive, the signs of critical illness can provide an appropriate window in which the physician can ask a patient, “If you were to die, where would you want to be, and what is most important to you?”

—Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, UCSF Medical Center Hospitalist Service

Practitioners skilled in end-of-life care cite several attributes characteristic of patients who are actively dying, such as:

- Refusal of food and liquids;

- Decreased level of awareness;

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath), including erratic breathing patterns;

- Mottled skin that is colder to the touch, along with blue toes; and

- Abnormal breathing sounds due to secretions in the lungs.

Honor Their Choices

Researchers cite many factors that determine whether a terminally ill cancer patient dies in the home or in an institution, including gender, race, marital status, income level, and available health system resources. In a Yale (New Haven, Conn.) epidemiological study, men, unmarried people, and those living in low-income areas were at higher risk for institutionalized deaths.3

Dr. Bernacki has found that the two most important determinants of whether a patient will go home to die are the patient’s condition and their resources at home. Sometimes transporting a patient is not practical because the patient may be so close to dying that there is a risk of death en route. Or the patient’s symptoms may not be controlled with oral pain medications and may require frequent IV dosing, in which case discharge is not feasible. Barriers at the home site include the lack of an identified primary caregiver and the unavailability of qualified hospice personnel and/or medical supplies.

For in-depth learning about palliative care topics, be sure to visit these sessions at the upcoming SHM Annual Meeting in Dallas, May 23-25:

- Palliative Pain Management: Thurs., May 24, 10:35-11:50;

- Non-Pain Symptom Management: Thurs., May 24, 1:10-2:25;

- Ethical and Legal Considerations of Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: Thurs., May 24, 2:45-4:00;

- Prognostication and PC Management of the Non-Cancer Diagnosis: Fri., May 25, 10:15-11:35; and

- Communication Skills and How to Conduct Family/Care Conferences: Fri., May 25, 1:35-2:55.

When the Hospital Is Preferred

In some situations, says Dr. Bernacki, “some family members feel very uncomfortable with the thought of their loved one dying at home.” Sometimes the disease process advances so quickly that the palliative care team cannot titrate the pain medicines to the right amount to allow discharge. Family members can become alarmed and may feel ill-prepared to handle difficult symptoms of the dying patient, such as uncontrolled nausea or dyspnea.

“So we have to just make an educated guess as to how long we think they have and how important it is to that patient or that family to be at home.” Often, the care team and family realize that it makes more sense not to move the patient but rather to try and make everything as comfortable as possible in the hospital.

The UCSF Palliative Care Service team, established by Steve Pantilat, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, has access to two in-hospital comfort care suites, where family members can stay with their loved ones at all times.4 Dr. Pantilat is also the past-president of SHM and the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care at UCSF.

In all cases, says Dr. Bernacki, hospitalists dealing with dying patients should remain cognizant that they are treating not only the patients but the family members as well. “Part of palliative care is making sure that the daughters, sons, and spouses are all well cared for,” she emphasizes. Ascertaining goals and negotiating what’s possible are the keys to good palliative care. TH

Gretchen Henkel writes frequently for The Hospitalist.

References

- Tang ST, McCorkle R, Bradley EH. Determinants of death in an inpatient hospice for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2004 Dec;2(4):361-370.

- Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:230-237.

- Gallo WT, Baker MJ, Bradley EH. Factors associated with home versus institutional death among cancer patients in Connecticut. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun;49(6):771-777. Comment in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun; 49(6):831-832.

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

Most Americans surveyed about their preferred place of death say they want to die at home.1 Nevertheless, many dying people are not able to realize this wish. One 2003 study found that nearly 90% of terminally ill cancer patients asked to choose where they would prefer to die cited their homes. Only one-third of those patients were able to make this desire a reality.2

The reasons behind the divergence between preference and actual place of death are complicated, says Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, and a palliative care specialist with the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center Hospitalist Service. “I think most people envision … [dying] at home, but sometimes that’s just not feasible, for multiple reasons. When the reality sets in, there has to be a good plan in place at home—meaning, enough people and resources to keep that person at home.”

Is Death Imminent?

Dr. Bernacki points out that many studies on dying preferences are conducted when the patient is not ill or actively dying. The scenario becomes much more complex when patients are in crisis or on an end-of-life trajectory. In initial assessments, hospitalists should try not only to ascertain the patient’s health status but also to ask respectfully about their goals for care.

“It might not be appropriate [to ask] every patient, ‘Where do you want to die?’ ” suggests Dr. Bernacki. It can be appropriate, though, to ask patients about their experiences with their current illness and to talk about some of the goals they hope to achieve in the next week or month.

Although it is not possible to predict exactly how long a person will survive, the signs of critical illness can provide an appropriate window in which the physician can ask a patient, “If you were to die, where would you want to be, and what is most important to you?”

—Rachelle Bernacki, MD, MS, assistant clinical professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, UCSF Medical Center Hospitalist Service

Practitioners skilled in end-of-life care cite several attributes characteristic of patients who are actively dying, such as:

- Refusal of food and liquids;

- Decreased level of awareness;

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath), including erratic breathing patterns;

- Mottled skin that is colder to the touch, along with blue toes; and

- Abnormal breathing sounds due to secretions in the lungs.

Honor Their Choices

Researchers cite many factors that determine whether a terminally ill cancer patient dies in the home or in an institution, including gender, race, marital status, income level, and available health system resources. In a Yale (New Haven, Conn.) epidemiological study, men, unmarried people, and those living in low-income areas were at higher risk for institutionalized deaths.3

Dr. Bernacki has found that the two most important determinants of whether a patient will go home to die are the patient’s condition and their resources at home. Sometimes transporting a patient is not practical because the patient may be so close to dying that there is a risk of death en route. Or the patient’s symptoms may not be controlled with oral pain medications and may require frequent IV dosing, in which case discharge is not feasible. Barriers at the home site include the lack of an identified primary caregiver and the unavailability of qualified hospice personnel and/or medical supplies.

For in-depth learning about palliative care topics, be sure to visit these sessions at the upcoming SHM Annual Meeting in Dallas, May 23-25:

- Palliative Pain Management: Thurs., May 24, 10:35-11:50;

- Non-Pain Symptom Management: Thurs., May 24, 1:10-2:25;

- Ethical and Legal Considerations of Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: Thurs., May 24, 2:45-4:00;

- Prognostication and PC Management of the Non-Cancer Diagnosis: Fri., May 25, 10:15-11:35; and

- Communication Skills and How to Conduct Family/Care Conferences: Fri., May 25, 1:35-2:55.

When the Hospital Is Preferred

In some situations, says Dr. Bernacki, “some family members feel very uncomfortable with the thought of their loved one dying at home.” Sometimes the disease process advances so quickly that the palliative care team cannot titrate the pain medicines to the right amount to allow discharge. Family members can become alarmed and may feel ill-prepared to handle difficult symptoms of the dying patient, such as uncontrolled nausea or dyspnea.

“So we have to just make an educated guess as to how long we think they have and how important it is to that patient or that family to be at home.” Often, the care team and family realize that it makes more sense not to move the patient but rather to try and make everything as comfortable as possible in the hospital.

The UCSF Palliative Care Service team, established by Steve Pantilat, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, has access to two in-hospital comfort care suites, where family members can stay with their loved ones at all times.4 Dr. Pantilat is also the past-president of SHM and the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care at UCSF.

In all cases, says Dr. Bernacki, hospitalists dealing with dying patients should remain cognizant that they are treating not only the patients but the family members as well. “Part of palliative care is making sure that the daughters, sons, and spouses are all well cared for,” she emphasizes. Ascertaining goals and negotiating what’s possible are the keys to good palliative care. TH

Gretchen Henkel writes frequently for The Hospitalist.

References

- Tang ST, McCorkle R, Bradley EH. Determinants of death in an inpatient hospice for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2004 Dec;2(4):361-370.

- Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:230-237.

- Gallo WT, Baker MJ, Bradley EH. Factors associated with home versus institutional death among cancer patients in Connecticut. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun;49(6):771-777. Comment in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun; 49(6):831-832.

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

Palliative Care Patience

As hospital-based palliative care programs continue to grow, palliative care specialists are eager to dispel misconceptions about their work.1 Quality palliative care management at the end of life is often mistakenly perceived as synonymous with adequate pain control, but controlling pain is just one of the facets of effectively moderating the intensity of patients’ and families’ suffering.

The cases narrated here illustrate some of the other common themes of good palliative care management at the end of life: aggressive symptom management, interdisciplinary teamwork, and attention to patients’ and families’ spiritual concerns. Active, respectful listening can help to identify and alleviate obstacles to a more humane end-of-life journey.

Time to Process the Big Picture

State-of-the-art medical therapy does not always address dying patients’ suffering, says Melissa Mahoney, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University and co-director of the Palliative Care Consult Service at Emory Crawford Long Hospital in Atlanta. She experienced this firsthand with a request to consult with a 60-year-old woman who had been in and out of sub-acute rehabilitation facilities seeking pain relief for her spinal stenosis. During a recent rehab facility stay, she had become septic and was transferred to the hospital for dialysis and other treatments. When Dr. Mahoney met the patient, the woman had been saying that she wanted to die, and her family was supportive of her wishes.

During her first conversation with the patient, however, Dr. Mahoney was able to discern that when she said she wanted to die, the patient meant, “I’m in so much pain that I don’t want to live this way.” The first step for the palliative care team was to begin patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with IV hydromorphone hydrochloride in an attempt to control her pain. The PCA worked—dramatically.

“The next day,” recalls Dr. Mahoney, “she was like a new person. She was able to cope with the idea of dialysis and was able to talk with her family and put things in perspective.”

The palliative care team followed the woman for months, as she continued a cycle of readmissions to both the sub-acute facility and the hospital. The difference from the previous scenario, however, was that the team could offer aggressive symptom management while encouraging the patient and her family to revisit quality of life issues. She eventually died in the hospital, but Dr. Mahoney believes that the palliative care team’s interventions and emphasis on communication helped the patient and her family to cope with the situation more effectively.

With pain under control, patients can begin to address such questions as What’s important to me now? How do I want to spend my days? Who would I want to speak for me if I can’t speak for myself? What are my end-of-life wishes?’

“None of those higher-level discussions can take place until someone can physically handle them,” emphasizes Dr. Mahoney. “The palliative care approach puts the focus back on the patient and on the family and away from the disease. It seeks to treat the person and hopefully ease suffering through the illness.”

Goals of Care Change with Time

Howard R. Epstein, MD, medical director, Care Management and Palliative Care at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., and a member of the SHM Palliative Care Task Force, notes that good palliative care incorporates ongoing discussions about patients’ and families’ goals of care. “Following diagnosis of a life-threatening illness, the initial goal might be ‘I want to be cured,’ ” he says. “But, if the disease progresses, then you need to have another discussion about goals of care. Hopefully, this is part of the process all along.”

Dr. Epstein participated in a particularly memorable case last fall, consulting with a patient who had metastatic renal cancer. Surgery had left him with an abdominal abscess, which surgeons were proposing to address with another procedure in order to prevent a potentially fatal infection. The palliative care team was called in to help Mr. A, who was only 50, decide on a care plan. During the care conference, says Dr. Epstein, Mr. A was alert and joking with his wife and indicated that he would rather go home with hospice care than undergo another surgery.

The team asked Mr. A about his goals. “He didn’t know how much time he had left,” recalls Dr. Epstein, “although he had a specific goal in mind: One of his four sons was getting married, and he wanted to be there for that. They were a very close-knit family.” Mr. A had been intensely engaged as a father all through his sons’ school years. They ranged in age from 19 to 30, and Mr. A was determined to remain close with them throughout his dying process.

The care team facilitated his return home with a PCA pump for pain and a link with a visiting hospice nurse and social worker. The case was followed by a reporter from the St. Paul Pioneer Press, and it was in those articles that Dr. Epstein learned more of Mr. A’s story. For instance, extended family members were pitching in to remodel the house; Mrs. A would have to sell it to cover her husband’s medical bills after he died. The engaged son later had to tell his father that his fiancée had canceled the wedding. Mr. A was able to allay his son’s guilt and fear about the canceled wedding and to be the kind of supportive father he had always been.

Because his goal of living until the wedding had changed, Mr. A was then able to focus on his other goal: having family with him as he died at home. And, indeed, Mr. A died a peaceful death a few weeks later surrounded by his whole family.

A Ship without a Captain

Pediatric hospitalists who handle palliative care recognize that, unlike adults’ end-of-life trajectories, which are usually a straight line, the trajectories of children with complex medical conditions tend to be more erratic between diagnosis and cure or death. As a result, their families spend a longer time relating to the medical system. The job of the palliative care team is to acknowledge the family’s experience and reframe that experience into a more egalitarian and satisfying one, including a comprehensive plan of care, says Margaret Hood, MD, senior pediatric hospitalist at MultiCare’s Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma, Wash. Thus, the interdisciplinary team at Mary Bridge meets with the family around a round table, where everyone’s input is given equal respect and weight.

Dr. Hood recalls one case that was brought to her attention by a social worker. Amy (not her real name) had been born prematurely and had endured many medical problems in her first four years. Then, at age four, she started walking and talking; by age seven, she was reading at the fifth grade level. From ages seven to 10, Amy had minor problems, but she began deteriorating at age 10, when it was found that she had mitochondrial disease. The family had taken her to many specialists without any resolution to her problem and had been charging medical treatments to their credit cards. The social worker was concerned that the family would be devastated by bankruptcy.

The palliative care team organized a care conference attended by Amy’s primary care physician, palliative care team members, and other specialists. Although the care conference resulted in small adjustments to her care plan—a change in medication and the addition of one diagnostic test—the true change came when Amy’s mother turned to Dr. Hood and said, “You know, I thought you’d given up on us.”

That’s when it occurred to Dr. Hood that families like these, visiting specialist after specialist for their child’s complex medical conditions, are “on ‘a ship without a captain.’ Whether or not their children have life-limiting illnesses, they need a captain of the ship to help them navigate their journey,” she says.

Amy’s mother had been under the impression that the physicians were telling her there was nothing else to hope for. “You don’t give up hope,” asserts Dr. Hood. “You just change what you’re hoping for.”

Amy died three months after the palliative care conference, but took a Make-A-Wish Foundation trip to Disneyland and celebrated Christmas at home with her family. Her last wish, after Christmas, was to avoid re-entering the hospital, and this was honored as well.

There May Be More Time to Live

Attention to nuances embedded in patients’ stated wishes can sometimes result in a reversal of expectations about end of life. Stephanie Grossman, MD, assistant professor of medicine and co-director of the Palliative Care Program for Emory University Hospital and Emory Crawford Long Hospital in Atlanta, was called by the hospitalist service last year to help facilitate transfer of a patient to hospice care.

In her 70s, the active woman had come to the hospital because a tumor mass was eroding through her breast tissue. The woman was avoiding treatment, including a biopsy, and appeared to be resolved to her fate. Based on her conversation with the emergency department (ED) attending, hospice was discussed and recommended; the patient was admitted primarily for IV antibiotics and care of her wound. In discussing goals of care with the patient, however, Dr. Grossman was able to elicit her reasons for refusing treatment. Ten years earlier, the patient had watched her daughter suffer with aggressive chemotherapy and radiation for her breast cancer. She told Dr. Grossman, “I’ve lived my life; I don’t want to go through all that.”

Knowing that breast cancer treatments have evolved in the past decade, Dr. Grossman asked the woman whether she would agree to a consultation with an oncologist to find out about less toxic treatment, including hormonal therapy. Subsequently, the patient decided to undergo a lumpectomy to increase her options. Dr. Grossman also prescribed a mild pain reliever for the woman, who had expressed fears about becoming addicted to pain medication (a common misperception in elderly patients). Upon discharge, the patient was feeling better physically, and she was optimistic about her future.

Despite the perceptions of the ED staff, the patient had not been hospice-appropriate. “No one had ever offered her the alternatives. In her mind, she saw chemotherapy as this terrible thing, and she just didn’t want to have that,” says Dr. Grossman. “So by listening to her we found out why she didn’t want chemotherapy, and we were able to encourage her to talk with the oncologist and the surgeon.”

I’m Afraid of What Comes after This Life

“Sometimes you find that patients and families are making decisions purely in a spiritual context,” notes Dr. Mahoney. “Until you know that, you can deliver clear and concise medical information and opinions and they won’t hear it. They may respect your opinion, but they will not take that into consideration when they’re making the decisions about themselves or a loved one because their spiritual belief system supersedes that factual information.”

Last year, Dr. Mahoney encountered a woman her late 50s with metastatic cancer. Her mother had died young of the same disease. The patient knew her disease was advanced and that she was facing the same thing her mother had faced. She, too, was leaving behind her daughters.

The patient, recalls Dr. Mahoney, had not filled out an advance directive and was having a difficult time talking with her family about her situation. It is Dr. Mahoney’s practice in such settings to ask people about their hopes and their fears, “because you can really gauge how someone sees their illness by asking those questions.”

The woman responded that she was very afraid of dying. “When I hear that answer, my next question is, ‘What do you fear? Do you fear that you might suffer?’ She said, ‘Oh no, no, I’m not afraid of that at all. Actually, I’ve sinned a lot in my life, and I’m afraid of what comes after this life.’ ”

Realizing that the woman was suffering spiritually, Dr. Mahoney called in her team’s chaplain to meet with the patient. During that meeting, the patient revealed to Chaplain Sandra Schaap that she had been the one to remove her mother from life support (her mother had not left an advance directive either). She was plagued by the fear of how she would be judged for that act. The chaplain was able to offer some comfort by sharing a benediction, which stated (among other things) that Christ would complete what we have left undone in this life.

“That conversation helped the patient see that she needed to complete her own advance directive so that her daughters wouldn’t go through the same thing that she had with her own mother,” says Dr. Mahoney.

Although Dr. Mahoney did not see the woman again, “I think we certainly set the framework for her and her family to be able to cope with what was coming. In the traditional medical model of disease treatment, I’m not sure that kind of detail would have come out. This woman would have left the hospital still carrying around that burden and [would have] had a very different life from that point,” she says.

Conclusion

“Every patient and family has a story of their illness and how it has impacted their lives,” Dr. Mahoney emphasizes. “Many times people are in the hospital for an acute problem, but they’ve suffered with an illness for years. There is a real opportunity to allow patients and families to tell their stories. People are often relieved when someone listens and can help put things in perspective. Palliative care specialists, by actively listening to patient and family concerns, can help relieve suffering on a physical, spiritual, and emotional level even when cure is not possible.” TH

In this issue Gretchen Henkel also writes about hospitalists who are overcommitted.

Reference

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. The case for hospital-based palliative care. Available at: www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/case/support-from-capc/capc_publications/making-the-case.pdf. Accessed on February 20, 2007.

As hospital-based palliative care programs continue to grow, palliative care specialists are eager to dispel misconceptions about their work.1 Quality palliative care management at the end of life is often mistakenly perceived as synonymous with adequate pain control, but controlling pain is just one of the facets of effectively moderating the intensity of patients’ and families’ suffering.

The cases narrated here illustrate some of the other common themes of good palliative care management at the end of life: aggressive symptom management, interdisciplinary teamwork, and attention to patients’ and families’ spiritual concerns. Active, respectful listening can help to identify and alleviate obstacles to a more humane end-of-life journey.

Time to Process the Big Picture

State-of-the-art medical therapy does not always address dying patients’ suffering, says Melissa Mahoney, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University and co-director of the Palliative Care Consult Service at Emory Crawford Long Hospital in Atlanta. She experienced this firsthand with a request to consult with a 60-year-old woman who had been in and out of sub-acute rehabilitation facilities seeking pain relief for her spinal stenosis. During a recent rehab facility stay, she had become septic and was transferred to the hospital for dialysis and other treatments. When Dr. Mahoney met the patient, the woman had been saying that she wanted to die, and her family was supportive of her wishes.

During her first conversation with the patient, however, Dr. Mahoney was able to discern that when she said she wanted to die, the patient meant, “I’m in so much pain that I don’t want to live this way.” The first step for the palliative care team was to begin patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with IV hydromorphone hydrochloride in an attempt to control her pain. The PCA worked—dramatically.

“The next day,” recalls Dr. Mahoney, “she was like a new person. She was able to cope with the idea of dialysis and was able to talk with her family and put things in perspective.”

The palliative care team followed the woman for months, as she continued a cycle of readmissions to both the sub-acute facility and the hospital. The difference from the previous scenario, however, was that the team could offer aggressive symptom management while encouraging the patient and her family to revisit quality of life issues. She eventually died in the hospital, but Dr. Mahoney believes that the palliative care team’s interventions and emphasis on communication helped the patient and her family to cope with the situation more effectively.

With pain under control, patients can begin to address such questions as What’s important to me now? How do I want to spend my days? Who would I want to speak for me if I can’t speak for myself? What are my end-of-life wishes?’

“None of those higher-level discussions can take place until someone can physically handle them,” emphasizes Dr. Mahoney. “The palliative care approach puts the focus back on the patient and on the family and away from the disease. It seeks to treat the person and hopefully ease suffering through the illness.”

Goals of Care Change with Time

Howard R. Epstein, MD, medical director, Care Management and Palliative Care at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., and a member of the SHM Palliative Care Task Force, notes that good palliative care incorporates ongoing discussions about patients’ and families’ goals of care. “Following diagnosis of a life-threatening illness, the initial goal might be ‘I want to be cured,’ ” he says. “But, if the disease progresses, then you need to have another discussion about goals of care. Hopefully, this is part of the process all along.”

Dr. Epstein participated in a particularly memorable case last fall, consulting with a patient who had metastatic renal cancer. Surgery had left him with an abdominal abscess, which surgeons were proposing to address with another procedure in order to prevent a potentially fatal infection. The palliative care team was called in to help Mr. A, who was only 50, decide on a care plan. During the care conference, says Dr. Epstein, Mr. A was alert and joking with his wife and indicated that he would rather go home with hospice care than undergo another surgery.

The team asked Mr. A about his goals. “He didn’t know how much time he had left,” recalls Dr. Epstein, “although he had a specific goal in mind: One of his four sons was getting married, and he wanted to be there for that. They were a very close-knit family.” Mr. A had been intensely engaged as a father all through his sons’ school years. They ranged in age from 19 to 30, and Mr. A was determined to remain close with them throughout his dying process.