User login

Crucial Contact

If the secret to successful real estate investing is “location, location, location,” the key to maintaining good relationships with referring physicians is “communication, communication, communication.” While this may seem simplistic, the complexities of interpersonal communications can pose challenges even in the most straightforward of physician interchanges.

Recent studies and hospitalists consulted for this report maintain that hospitalists’ communications with referring physicians must be examined, practiced, and fine-tuned continually to ensure satisfaction for doctors—and their patients.

“It’s all about the communication,” says Bruce Becker, MD, chief medical officer at Medical Center Hospital in Odessa, Texas, and a family physician and professor of medicine for more than 20 years. “It’s sometimes not what you say, but how you say it.”

According to John Nelson, MD, medical director of the Hospitalist Practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., a consultant for hospital medicine groups with Nelson/Flores Associates and a columnist for The Hospitalist (“Practice Management”), it is key for hospitalists to examine and revise oral and written communication processes—especially at critical points during patient handoffs—rather than to assume that good communication will just happen naturally.

Gaining Acceptance

Some primary care physicians (PCPs) are more willing than others to refer patients to a hospitalist. Initially, new programs may have to work hard to gain acceptance with referring physicians. Some referring physicians may not be ready to give up hospital visits and may want to maintain collegiality and control. On the other hand, some family physicians are “ready to step away from hospital practice,” says Dr. Becker, citing diminishing reimbursements due to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and managed care.

John A. Bolinger, DO, FACP, medical director of the Hospitalist Program at Terre Haute (Ind.) Regional Hospital, believes that one way to promote a hospitalist program to PCPs is to emphasize hospitalists’ levels of training and efficiency.

“I try to make them aware of how [our hospitalist program] can be advantageous to them,” he explains. “Even if they have only one patient in the hospital, by the time they drive there, get the chart, make the rounds, make their notes, and do the required paperwork, it may take them an hour to see one patient. It makes good economic sense for them to stay in their offices, where they can see a minimum of four patients in the same amount of time for equal or better reimbursements.”

When primary care physicians voice resistance to using a hospitalist program, Dr. Bolinger says he tries to impress upon them the fact that hospitalists do not have outside practices, they will “never try to steal patients,” they stay within referral patterns, and they will make sure that PCPs get pertinent records as soon as possible. Dr. Bolinger believes referring physicians’ biggest concern when dealing with hospitalists is that they “don’t want to lose control.” The way to address those fears is to make sure referring physicians are always kept in the communications loop regarding their patients’ progress.

The policy for Dr. Bolinger’s hospitalist program is to make sure all dictated reports are transcribed and faxed immediately to the referring physician’s office. All scheduled follow-up appointments and medication changes are included in discharge summaries. “If need be,” says Dr. Bolinger, “we will even hand deliver information to physicians’ offices, which we have done multiple times.”

Become User-Friendly

The methods Dr. Bolinger describes often result in referring physicians’ satisfaction with hospitalist services, followed by increased referrals. Hospitalists can ensure continued referrals from their PCPs if they remember hospital medicine’s cardinal rules of availability and prompt, thorough reporting, says Dr. Nelson. It can help to view the interface with the hospitalist service from the PCP’s point of view.

For instance, how can physicians quickly reach the hospitalist service? “If you’re a referring doctor and you’ve got a patient in your office whom you think should be admitted today, who do you call? This can actually be a little tricky for most practices,” says Dr. Nelson. “Every practice should give some thought to making that contact as easy for the referring doctors as possible.”

Some important questions to ask: When trying to reach a hospitalist, is it best to call the group’s main number? Will a voicemail message be returned within an hour? Two hours? Is it better to call the hospital operator and have the hospitalist paged? Or do PCPs have access to hospitalists’ cell phone numbers?

Dr. Nelson suggests that hospitalist groups also give thought to standardizing admission and discharge reports, as well as other forms. Often, individual members of a hospitalist group use slightly different formats for reporting to referring physicians. He points out that this can be less user friendly for the reader, who may have a harder time scanning the document quickly to find a particular piece of important information. Other useful suggestions for making reports user friendly: Use similar headings on all reports; avoid dense text; list pending tests in a prominent place in the report document; and consider highlighting or underlining key words.

Preference for In-Person Contact

For a new hospitalist practice, telephone communication between the hospitalist and the primary physician is valuable, and the hospitalist should “pick up the phone liberally,” says Dr. Nelson.

Dr. Becker believes the best way for physicians to communicate is one on one—in person. “Too often,” he says, “we get used to communicating through a third party—usually a unit clerk, a nurse, or a resident. I believe that physician-to-physician communication is the ideal. If the attending physician and the consultant [hospitalist or subspecialist] speak in person, they can explain their thinking to each other, and “within one minute of precious time, figure out which way to go.”

In this way, without wasting time, the physician gives the consultant guidance as to the appropriate track to take and can also listen to the consultant’s suggestions.

“I feel that medicine has perhaps gotten a little bit away from that communication link,” continues Dr. Becker. “When we get further away from that direct communication—whether it is between doctors and consultants, nurses and doctors, or doctors and family members—you take that little bit of risk that there will be a missed step, either on the part of the communicator or on the receiving end as the listener.”

In a study exploring barriers to effective patient handoffs, Solet and colleagues focused on the communication between physicians as a vital link in patient care continuity. The authors concluded that, regardless of the method of managing patient handoffs (e.g., computer-assisted or paper-based), the best way to ensure effective handoffs of hospitalized patients was “precise, unambiguous, face-to-face communication.”1

In a 2001 study by Hruby, Pantilat, and colleagues at UCSF, the authors found that, for the most part, hospitalized patients with PCPs wanted contact with their primary physicians even while in the hospital. Approximately half of the surveyed patients also believed that the PCP, rather than an inpatient physician, should be the first to discuss with them serious diagnoses or disease management choices.2 Preferences such as those expressed in this study may play into referring physicians’ reluctance to make use of hospitalist services, says Dr. Bolinger. They may fear that patients will feel abandoned by the primary physician. Dr. Bolinger’s response to those sentiments: “Initially, some patients [in our hospital] were a little guarded and were not sure what to expect. But after a day or two of having us there, they are generally very, very pleased to have us on board. We are part of their medical team now.”

A Need for Marketing?

Dr. Becker has been actively developing a hospital medicine program at Medical Center Hospital for the past two years and joined SHM as part of that effort. Familiarizing himself with the tenets of hospital medicine, he discovered that, as a family doctor, “unknowingly, I was actually practicing hospital medicine for 20 years!”

As part of the hospital medicine program development process, he has solicited input from local physicians as well as patients. A simple survey to assess interest in a hospitalist program asked potential referring physicians, Would you use a hospitalist? Would you use a hospitalist after waiting a while to see how the process goes? Or, would you not consider using a hospitalist?

In two years, says Dr. Becker, response from the referring physician community has changed from “bah, humbug” to one of readiness for the program.

A mass mailing can serve to introduce a hospital medicine program in a community. Dr. Bolinger’s group used this method and, in his experience, local subspecialists—orthopedists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists—have proved the biggest source of referrals to their program. But PCPs are starting to use the hospitalist service for vacations and call-coverage issues and are beginning to value hospitalists’ services. “Physicians like coming to the hospital, but they’re starting to realize that the hospitalist program is a better system,” says Dr. Bolinger.

Dr. Nelson has been a hospitalist for 18 years. For most of that time he has had no shortage of referred patients. In fact, the bigger problem has been finding enough doctors to join the group and handle the existing referral volume. In that situation, it has not made sense to undertake marketing with the goal of increasing referrals. However, he advises, “It is always worth spending time and energy trying to maintain good relationships with physicians with whom you regularly share patients, and perhaps this could be called ‘marketing.’”

To maintain good relationships with referring physicians, his group conducts a survey on a yearly basis. A survey, he suggests, should be very short, consisting of only a few key questions, such as:

- Do we send reports promptly to your practice?

- Are your patients satisfied with the care they receive from us?

- Do you have any comments or feedback for our group?

Although his group gains information from these surveys, Dr. Nelson notes that the greater value of conducting such surveys may be in building public relations capital. By conducting a survey, hospitalists demonstrate that they care enough to ask for their referring physicians’ input.

Another good marketing tool is a patient education brochure, given to referring physicians, that explains hospitalists and hospitalist care. These brochures can help referring physicians prepare their patients for seeing a hospitalist in the inpatient setting, thus easing the initial reluctance patients sometimes experience when encountering a new physician.

Conclusion

On the cusp of launching his medical center’s hospital medicine program, Dr. Becker sees that good communication between referring physicians and hospitalists will ensure the program’s success. He advises physicians to remember their classes in communication as third-year medical students, when most participate in videotaped patient encounters. It’s always instructive, he says, to see how we come across to others in conversation.

Both verbal and nonverbal cues play a part in good communication. A 2003 study by Griffith and colleagues concluded that better nonverbal communication skills are associated with greater patient satisfaction, and that formal instruction in nonverbal communication can be a good addition to residency training.3

“I find that doctors talk to each other, in general, very easily,” says Dr. Becker. Sometimes [good communication] is just a matter of opening that door and essentially keeping the former attending, the PCP, apprised of what is going on.”

When hospitalists attend to thorough communication and promptly deliver complete discharge summaries, family physicians can report to their patients that they know what happened in the hospital and poll their patients about their experiences in the hospital. In this way, hospitalists and referring physicians can cement their relationship as team members for the patient. The success of any hospitalist program, Dr. Becker believes, lies in “making sure you fulfill the promise of what hospital medicine generates, and that is a continuity of care … , obtaining front-end communication so that patients get the best care throughout their [hospital] stay, and then follow up with discharge summaries to the primary physician’s office.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a regular contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, et al. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2005 Dec;80(12): 1094-1099.

- Hruby M, Pantilat SZ, Lo B. How do patients view the role of the primary care physician in inpatient care? Am J Med. 2001;21;111(9B):21S-25S.

- Griffith CH III, Wilson JF, Langer S, et al. House staff nonverbal communication skills and standardized patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Mar;18(3):170-174.

If the secret to successful real estate investing is “location, location, location,” the key to maintaining good relationships with referring physicians is “communication, communication, communication.” While this may seem simplistic, the complexities of interpersonal communications can pose challenges even in the most straightforward of physician interchanges.

Recent studies and hospitalists consulted for this report maintain that hospitalists’ communications with referring physicians must be examined, practiced, and fine-tuned continually to ensure satisfaction for doctors—and their patients.

“It’s all about the communication,” says Bruce Becker, MD, chief medical officer at Medical Center Hospital in Odessa, Texas, and a family physician and professor of medicine for more than 20 years. “It’s sometimes not what you say, but how you say it.”

According to John Nelson, MD, medical director of the Hospitalist Practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., a consultant for hospital medicine groups with Nelson/Flores Associates and a columnist for The Hospitalist (“Practice Management”), it is key for hospitalists to examine and revise oral and written communication processes—especially at critical points during patient handoffs—rather than to assume that good communication will just happen naturally.

Gaining Acceptance

Some primary care physicians (PCPs) are more willing than others to refer patients to a hospitalist. Initially, new programs may have to work hard to gain acceptance with referring physicians. Some referring physicians may not be ready to give up hospital visits and may want to maintain collegiality and control. On the other hand, some family physicians are “ready to step away from hospital practice,” says Dr. Becker, citing diminishing reimbursements due to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and managed care.

John A. Bolinger, DO, FACP, medical director of the Hospitalist Program at Terre Haute (Ind.) Regional Hospital, believes that one way to promote a hospitalist program to PCPs is to emphasize hospitalists’ levels of training and efficiency.

“I try to make them aware of how [our hospitalist program] can be advantageous to them,” he explains. “Even if they have only one patient in the hospital, by the time they drive there, get the chart, make the rounds, make their notes, and do the required paperwork, it may take them an hour to see one patient. It makes good economic sense for them to stay in their offices, where they can see a minimum of four patients in the same amount of time for equal or better reimbursements.”

When primary care physicians voice resistance to using a hospitalist program, Dr. Bolinger says he tries to impress upon them the fact that hospitalists do not have outside practices, they will “never try to steal patients,” they stay within referral patterns, and they will make sure that PCPs get pertinent records as soon as possible. Dr. Bolinger believes referring physicians’ biggest concern when dealing with hospitalists is that they “don’t want to lose control.” The way to address those fears is to make sure referring physicians are always kept in the communications loop regarding their patients’ progress.

The policy for Dr. Bolinger’s hospitalist program is to make sure all dictated reports are transcribed and faxed immediately to the referring physician’s office. All scheduled follow-up appointments and medication changes are included in discharge summaries. “If need be,” says Dr. Bolinger, “we will even hand deliver information to physicians’ offices, which we have done multiple times.”

Become User-Friendly

The methods Dr. Bolinger describes often result in referring physicians’ satisfaction with hospitalist services, followed by increased referrals. Hospitalists can ensure continued referrals from their PCPs if they remember hospital medicine’s cardinal rules of availability and prompt, thorough reporting, says Dr. Nelson. It can help to view the interface with the hospitalist service from the PCP’s point of view.

For instance, how can physicians quickly reach the hospitalist service? “If you’re a referring doctor and you’ve got a patient in your office whom you think should be admitted today, who do you call? This can actually be a little tricky for most practices,” says Dr. Nelson. “Every practice should give some thought to making that contact as easy for the referring doctors as possible.”

Some important questions to ask: When trying to reach a hospitalist, is it best to call the group’s main number? Will a voicemail message be returned within an hour? Two hours? Is it better to call the hospital operator and have the hospitalist paged? Or do PCPs have access to hospitalists’ cell phone numbers?

Dr. Nelson suggests that hospitalist groups also give thought to standardizing admission and discharge reports, as well as other forms. Often, individual members of a hospitalist group use slightly different formats for reporting to referring physicians. He points out that this can be less user friendly for the reader, who may have a harder time scanning the document quickly to find a particular piece of important information. Other useful suggestions for making reports user friendly: Use similar headings on all reports; avoid dense text; list pending tests in a prominent place in the report document; and consider highlighting or underlining key words.

Preference for In-Person Contact

For a new hospitalist practice, telephone communication between the hospitalist and the primary physician is valuable, and the hospitalist should “pick up the phone liberally,” says Dr. Nelson.

Dr. Becker believes the best way for physicians to communicate is one on one—in person. “Too often,” he says, “we get used to communicating through a third party—usually a unit clerk, a nurse, or a resident. I believe that physician-to-physician communication is the ideal. If the attending physician and the consultant [hospitalist or subspecialist] speak in person, they can explain their thinking to each other, and “within one minute of precious time, figure out which way to go.”

In this way, without wasting time, the physician gives the consultant guidance as to the appropriate track to take and can also listen to the consultant’s suggestions.

“I feel that medicine has perhaps gotten a little bit away from that communication link,” continues Dr. Becker. “When we get further away from that direct communication—whether it is between doctors and consultants, nurses and doctors, or doctors and family members—you take that little bit of risk that there will be a missed step, either on the part of the communicator or on the receiving end as the listener.”

In a study exploring barriers to effective patient handoffs, Solet and colleagues focused on the communication between physicians as a vital link in patient care continuity. The authors concluded that, regardless of the method of managing patient handoffs (e.g., computer-assisted or paper-based), the best way to ensure effective handoffs of hospitalized patients was “precise, unambiguous, face-to-face communication.”1

In a 2001 study by Hruby, Pantilat, and colleagues at UCSF, the authors found that, for the most part, hospitalized patients with PCPs wanted contact with their primary physicians even while in the hospital. Approximately half of the surveyed patients also believed that the PCP, rather than an inpatient physician, should be the first to discuss with them serious diagnoses or disease management choices.2 Preferences such as those expressed in this study may play into referring physicians’ reluctance to make use of hospitalist services, says Dr. Bolinger. They may fear that patients will feel abandoned by the primary physician. Dr. Bolinger’s response to those sentiments: “Initially, some patients [in our hospital] were a little guarded and were not sure what to expect. But after a day or two of having us there, they are generally very, very pleased to have us on board. We are part of their medical team now.”

A Need for Marketing?

Dr. Becker has been actively developing a hospital medicine program at Medical Center Hospital for the past two years and joined SHM as part of that effort. Familiarizing himself with the tenets of hospital medicine, he discovered that, as a family doctor, “unknowingly, I was actually practicing hospital medicine for 20 years!”

As part of the hospital medicine program development process, he has solicited input from local physicians as well as patients. A simple survey to assess interest in a hospitalist program asked potential referring physicians, Would you use a hospitalist? Would you use a hospitalist after waiting a while to see how the process goes? Or, would you not consider using a hospitalist?

In two years, says Dr. Becker, response from the referring physician community has changed from “bah, humbug” to one of readiness for the program.

A mass mailing can serve to introduce a hospital medicine program in a community. Dr. Bolinger’s group used this method and, in his experience, local subspecialists—orthopedists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists—have proved the biggest source of referrals to their program. But PCPs are starting to use the hospitalist service for vacations and call-coverage issues and are beginning to value hospitalists’ services. “Physicians like coming to the hospital, but they’re starting to realize that the hospitalist program is a better system,” says Dr. Bolinger.

Dr. Nelson has been a hospitalist for 18 years. For most of that time he has had no shortage of referred patients. In fact, the bigger problem has been finding enough doctors to join the group and handle the existing referral volume. In that situation, it has not made sense to undertake marketing with the goal of increasing referrals. However, he advises, “It is always worth spending time and energy trying to maintain good relationships with physicians with whom you regularly share patients, and perhaps this could be called ‘marketing.’”

To maintain good relationships with referring physicians, his group conducts a survey on a yearly basis. A survey, he suggests, should be very short, consisting of only a few key questions, such as:

- Do we send reports promptly to your practice?

- Are your patients satisfied with the care they receive from us?

- Do you have any comments or feedback for our group?

Although his group gains information from these surveys, Dr. Nelson notes that the greater value of conducting such surveys may be in building public relations capital. By conducting a survey, hospitalists demonstrate that they care enough to ask for their referring physicians’ input.

Another good marketing tool is a patient education brochure, given to referring physicians, that explains hospitalists and hospitalist care. These brochures can help referring physicians prepare their patients for seeing a hospitalist in the inpatient setting, thus easing the initial reluctance patients sometimes experience when encountering a new physician.

Conclusion

On the cusp of launching his medical center’s hospital medicine program, Dr. Becker sees that good communication between referring physicians and hospitalists will ensure the program’s success. He advises physicians to remember their classes in communication as third-year medical students, when most participate in videotaped patient encounters. It’s always instructive, he says, to see how we come across to others in conversation.

Both verbal and nonverbal cues play a part in good communication. A 2003 study by Griffith and colleagues concluded that better nonverbal communication skills are associated with greater patient satisfaction, and that formal instruction in nonverbal communication can be a good addition to residency training.3

“I find that doctors talk to each other, in general, very easily,” says Dr. Becker. Sometimes [good communication] is just a matter of opening that door and essentially keeping the former attending, the PCP, apprised of what is going on.”

When hospitalists attend to thorough communication and promptly deliver complete discharge summaries, family physicians can report to their patients that they know what happened in the hospital and poll their patients about their experiences in the hospital. In this way, hospitalists and referring physicians can cement their relationship as team members for the patient. The success of any hospitalist program, Dr. Becker believes, lies in “making sure you fulfill the promise of what hospital medicine generates, and that is a continuity of care … , obtaining front-end communication so that patients get the best care throughout their [hospital] stay, and then follow up with discharge summaries to the primary physician’s office.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a regular contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, et al. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2005 Dec;80(12): 1094-1099.

- Hruby M, Pantilat SZ, Lo B. How do patients view the role of the primary care physician in inpatient care? Am J Med. 2001;21;111(9B):21S-25S.

- Griffith CH III, Wilson JF, Langer S, et al. House staff nonverbal communication skills and standardized patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Mar;18(3):170-174.

If the secret to successful real estate investing is “location, location, location,” the key to maintaining good relationships with referring physicians is “communication, communication, communication.” While this may seem simplistic, the complexities of interpersonal communications can pose challenges even in the most straightforward of physician interchanges.

Recent studies and hospitalists consulted for this report maintain that hospitalists’ communications with referring physicians must be examined, practiced, and fine-tuned continually to ensure satisfaction for doctors—and their patients.

“It’s all about the communication,” says Bruce Becker, MD, chief medical officer at Medical Center Hospital in Odessa, Texas, and a family physician and professor of medicine for more than 20 years. “It’s sometimes not what you say, but how you say it.”

According to John Nelson, MD, medical director of the Hospitalist Practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., a consultant for hospital medicine groups with Nelson/Flores Associates and a columnist for The Hospitalist (“Practice Management”), it is key for hospitalists to examine and revise oral and written communication processes—especially at critical points during patient handoffs—rather than to assume that good communication will just happen naturally.

Gaining Acceptance

Some primary care physicians (PCPs) are more willing than others to refer patients to a hospitalist. Initially, new programs may have to work hard to gain acceptance with referring physicians. Some referring physicians may not be ready to give up hospital visits and may want to maintain collegiality and control. On the other hand, some family physicians are “ready to step away from hospital practice,” says Dr. Becker, citing diminishing reimbursements due to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and managed care.

John A. Bolinger, DO, FACP, medical director of the Hospitalist Program at Terre Haute (Ind.) Regional Hospital, believes that one way to promote a hospitalist program to PCPs is to emphasize hospitalists’ levels of training and efficiency.

“I try to make them aware of how [our hospitalist program] can be advantageous to them,” he explains. “Even if they have only one patient in the hospital, by the time they drive there, get the chart, make the rounds, make their notes, and do the required paperwork, it may take them an hour to see one patient. It makes good economic sense for them to stay in their offices, where they can see a minimum of four patients in the same amount of time for equal or better reimbursements.”

When primary care physicians voice resistance to using a hospitalist program, Dr. Bolinger says he tries to impress upon them the fact that hospitalists do not have outside practices, they will “never try to steal patients,” they stay within referral patterns, and they will make sure that PCPs get pertinent records as soon as possible. Dr. Bolinger believes referring physicians’ biggest concern when dealing with hospitalists is that they “don’t want to lose control.” The way to address those fears is to make sure referring physicians are always kept in the communications loop regarding their patients’ progress.

The policy for Dr. Bolinger’s hospitalist program is to make sure all dictated reports are transcribed and faxed immediately to the referring physician’s office. All scheduled follow-up appointments and medication changes are included in discharge summaries. “If need be,” says Dr. Bolinger, “we will even hand deliver information to physicians’ offices, which we have done multiple times.”

Become User-Friendly

The methods Dr. Bolinger describes often result in referring physicians’ satisfaction with hospitalist services, followed by increased referrals. Hospitalists can ensure continued referrals from their PCPs if they remember hospital medicine’s cardinal rules of availability and prompt, thorough reporting, says Dr. Nelson. It can help to view the interface with the hospitalist service from the PCP’s point of view.

For instance, how can physicians quickly reach the hospitalist service? “If you’re a referring doctor and you’ve got a patient in your office whom you think should be admitted today, who do you call? This can actually be a little tricky for most practices,” says Dr. Nelson. “Every practice should give some thought to making that contact as easy for the referring doctors as possible.”

Some important questions to ask: When trying to reach a hospitalist, is it best to call the group’s main number? Will a voicemail message be returned within an hour? Two hours? Is it better to call the hospital operator and have the hospitalist paged? Or do PCPs have access to hospitalists’ cell phone numbers?

Dr. Nelson suggests that hospitalist groups also give thought to standardizing admission and discharge reports, as well as other forms. Often, individual members of a hospitalist group use slightly different formats for reporting to referring physicians. He points out that this can be less user friendly for the reader, who may have a harder time scanning the document quickly to find a particular piece of important information. Other useful suggestions for making reports user friendly: Use similar headings on all reports; avoid dense text; list pending tests in a prominent place in the report document; and consider highlighting or underlining key words.

Preference for In-Person Contact

For a new hospitalist practice, telephone communication between the hospitalist and the primary physician is valuable, and the hospitalist should “pick up the phone liberally,” says Dr. Nelson.

Dr. Becker believes the best way for physicians to communicate is one on one—in person. “Too often,” he says, “we get used to communicating through a third party—usually a unit clerk, a nurse, or a resident. I believe that physician-to-physician communication is the ideal. If the attending physician and the consultant [hospitalist or subspecialist] speak in person, they can explain their thinking to each other, and “within one minute of precious time, figure out which way to go.”

In this way, without wasting time, the physician gives the consultant guidance as to the appropriate track to take and can also listen to the consultant’s suggestions.

“I feel that medicine has perhaps gotten a little bit away from that communication link,” continues Dr. Becker. “When we get further away from that direct communication—whether it is between doctors and consultants, nurses and doctors, or doctors and family members—you take that little bit of risk that there will be a missed step, either on the part of the communicator or on the receiving end as the listener.”

In a study exploring barriers to effective patient handoffs, Solet and colleagues focused on the communication between physicians as a vital link in patient care continuity. The authors concluded that, regardless of the method of managing patient handoffs (e.g., computer-assisted or paper-based), the best way to ensure effective handoffs of hospitalized patients was “precise, unambiguous, face-to-face communication.”1

In a 2001 study by Hruby, Pantilat, and colleagues at UCSF, the authors found that, for the most part, hospitalized patients with PCPs wanted contact with their primary physicians even while in the hospital. Approximately half of the surveyed patients also believed that the PCP, rather than an inpatient physician, should be the first to discuss with them serious diagnoses or disease management choices.2 Preferences such as those expressed in this study may play into referring physicians’ reluctance to make use of hospitalist services, says Dr. Bolinger. They may fear that patients will feel abandoned by the primary physician. Dr. Bolinger’s response to those sentiments: “Initially, some patients [in our hospital] were a little guarded and were not sure what to expect. But after a day or two of having us there, they are generally very, very pleased to have us on board. We are part of their medical team now.”

A Need for Marketing?

Dr. Becker has been actively developing a hospital medicine program at Medical Center Hospital for the past two years and joined SHM as part of that effort. Familiarizing himself with the tenets of hospital medicine, he discovered that, as a family doctor, “unknowingly, I was actually practicing hospital medicine for 20 years!”

As part of the hospital medicine program development process, he has solicited input from local physicians as well as patients. A simple survey to assess interest in a hospitalist program asked potential referring physicians, Would you use a hospitalist? Would you use a hospitalist after waiting a while to see how the process goes? Or, would you not consider using a hospitalist?

In two years, says Dr. Becker, response from the referring physician community has changed from “bah, humbug” to one of readiness for the program.

A mass mailing can serve to introduce a hospital medicine program in a community. Dr. Bolinger’s group used this method and, in his experience, local subspecialists—orthopedists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists—have proved the biggest source of referrals to their program. But PCPs are starting to use the hospitalist service for vacations and call-coverage issues and are beginning to value hospitalists’ services. “Physicians like coming to the hospital, but they’re starting to realize that the hospitalist program is a better system,” says Dr. Bolinger.

Dr. Nelson has been a hospitalist for 18 years. For most of that time he has had no shortage of referred patients. In fact, the bigger problem has been finding enough doctors to join the group and handle the existing referral volume. In that situation, it has not made sense to undertake marketing with the goal of increasing referrals. However, he advises, “It is always worth spending time and energy trying to maintain good relationships with physicians with whom you regularly share patients, and perhaps this could be called ‘marketing.’”

To maintain good relationships with referring physicians, his group conducts a survey on a yearly basis. A survey, he suggests, should be very short, consisting of only a few key questions, such as:

- Do we send reports promptly to your practice?

- Are your patients satisfied with the care they receive from us?

- Do you have any comments or feedback for our group?

Although his group gains information from these surveys, Dr. Nelson notes that the greater value of conducting such surveys may be in building public relations capital. By conducting a survey, hospitalists demonstrate that they care enough to ask for their referring physicians’ input.

Another good marketing tool is a patient education brochure, given to referring physicians, that explains hospitalists and hospitalist care. These brochures can help referring physicians prepare their patients for seeing a hospitalist in the inpatient setting, thus easing the initial reluctance patients sometimes experience when encountering a new physician.

Conclusion

On the cusp of launching his medical center’s hospital medicine program, Dr. Becker sees that good communication between referring physicians and hospitalists will ensure the program’s success. He advises physicians to remember their classes in communication as third-year medical students, when most participate in videotaped patient encounters. It’s always instructive, he says, to see how we come across to others in conversation.

Both verbal and nonverbal cues play a part in good communication. A 2003 study by Griffith and colleagues concluded that better nonverbal communication skills are associated with greater patient satisfaction, and that formal instruction in nonverbal communication can be a good addition to residency training.3

“I find that doctors talk to each other, in general, very easily,” says Dr. Becker. Sometimes [good communication] is just a matter of opening that door and essentially keeping the former attending, the PCP, apprised of what is going on.”

When hospitalists attend to thorough communication and promptly deliver complete discharge summaries, family physicians can report to their patients that they know what happened in the hospital and poll their patients about their experiences in the hospital. In this way, hospitalists and referring physicians can cement their relationship as team members for the patient. The success of any hospitalist program, Dr. Becker believes, lies in “making sure you fulfill the promise of what hospital medicine generates, and that is a continuity of care … , obtaining front-end communication so that patients get the best care throughout their [hospital] stay, and then follow up with discharge summaries to the primary physician’s office.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a regular contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, et al. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2005 Dec;80(12): 1094-1099.

- Hruby M, Pantilat SZ, Lo B. How do patients view the role of the primary care physician in inpatient care? Am J Med. 2001;21;111(9B):21S-25S.

- Griffith CH III, Wilson JF, Langer S, et al. House staff nonverbal communication skills and standardized patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Mar;18(3):170-174.

Pregnancy Perils

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and

- Gestational hypertension: either transient mild hypertension during the third trimester or mild hypertension detected during the third trimester that does not resolve by 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosing Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Of these hypertensive entities, this article focuses on the most common and potentially serious one: preeclampsia/eclampsia. Preeclampsia is characterized by blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg—measured on two separate occasions, and proteinuria greater than 300 mg/24 hours, occurring after 20 weeks gestation. Severe preeclampsia includes the same criteria, as well as proteinuria greater than 5,000 mg/24 hours; blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg; or end-organ damage such as headaches, visual changes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, or thrombocytopenia.

Historically, the term eclampsia has been reserved to describe the symptoms of preeclampsia combined with the occurrence of seizure activity. HELLP syndrome is a severe variant of preeclampsia that affects up to 1% of pregnancies and includes the constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count.

Given the potential risks for these disorders during pregnancy, it seems logical to target primarily those individuals at risk and attempt to prevent the disorder. Traditionally, the higher risk populations include patients experiencing primagravida pregnancies, those with a history of hypertension or renal disease, women who have had prior episodes of preeclampsia, and multiparous individuals with different paternal partners. Other less helpful or more expensive screening procedures include evaluation for inherited thrombophilias.

Recommended Treatment

Several trials have attempted to prevent the development of preeclampsia using calcium supplementation or aspirin therapy, but current evidence demonstrates no benefit from these interventions except in selected populations.3,4 For the past several decades, the treatment for hypertension during pregnancy has consisted of either delivery of the fetus or bed rest combined with therapies involving alpha-methyl-DOPA, hydralazine, and intravenous magnesium sulfate, depending on the level of the patient’s blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as the stage of the pregnancy.

Because of the potential risks to the health of the infant (as well as that of the mother) generic interventional trials extrapolated from other hypertensive populations that may offer equivalent or more effective therapies have not been readily accomplished. In spite of this lack of clinical and outcomes studies, the following generalizations regarding care are currently advocated:

1. Continue anti-hypertensive therapy for chronic hypertension with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Though the risks of SGA infants and preeclampsia were not affected by therapy, the incidence of premature delivery was reduced. Nearly all anti-hypertensive drugs have been used in treating chronic hypertension in pregnancy, but angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated because of teratogenecity. Diuretics and hydralazine may also have adverse outcomes on fetal and/or maternal health, respectively.

Though diuretics may reduce an already compromised placental blood flow by reducing intravascular volume, a number of randomized trials using diuretics have been reported. The population studied in these trials totaled approximately 7,000 individuals, and the results show no demonstrable adverse effects.5 Centrally acting alpha 2 adrenergic agonists (alpha-methyl-DOPA, clonidine), long-acting dihydropyridines (calcium channel blockers), and beta-adrenergic blockers with or without alpha-adrenergic blockade have been used successfully during pregnancy.6 Infants born to mothers receiving beta-blockers have a higher incidence of transient heart block and bradycardia. Newer agents, as opposed to alpha-methyl-DOPA and hydralazine, have not been shown to be more effective in controlling blood pressure but have demonstrated fewer adverse effects or events.

2. Mild preeclampsia may be treated using late-term delivery or bed rest before the pregnancy reaches 36 weeks. Close observation in a hospital is warranted until lack of progression to severe eclampsia is ensured.

3. Severe preeclampsia must be treated using either delivery or interventions to control blood pressure and prevent seizures while delivery is temporarily delayed to allow for fetal maturation. Intravenous magnesium sulfate (Mg2SO4), titrated to therapeutic concentrations of magnesium (4.5-8.5 mg/dl) along with suppression of deep tendon reflexes, has significantly lowered blood pressure and reduced the incidence of seizure activity. In direct comparison with intravenous phenytoin, there were no episodes of eclampsia in patients treated with magnesium (zero of 1,049 patients treated), while 10 of 1,089 individuals treated with phenytoin developed eclampsia.7 Similarly, Mg2SO4 decreased the incidence of eclampsia to 0.8% compared with 2.6% of individuals treated with nimodipine.8 Likewise, Mg2SO4 significantly reduced recurrent seizures compared to diazepam and phenytoin. In patients with renal insufficiency or other relative contraindications to Mg2SO4 therapy, the physician may treat the blood pressure with labetalol or a calcium channel antagonist and provide prophylaxis from seizures using phenytoin.

Because of the lack of a more complete understanding of the etiology (or etiologies) of preeclampsia/eclampsia, we are not fully able to identify individuals who are at risk. With further investigation, we will be able to provide more selective and effective interventions.

Nitrous Oxide’s Vital Role in Pregnancy

In this regard, considerable investigation has been directed toward a better understanding of eclampsia/preeclampsia in the past 20 years. The current discussion will highlight three promising lines of inquiry. Before commenting on these three areas of investigation, we feel it is important to illustrate the fundamental defect observed in all models of preeclampsia. This unifying abnormality is the presence of a placenta with inadequate uterine blood flow.

In a normal pregnancy, after implantation in the uterine wall, cytotrophoblasts invade the uterine wall, undergo a transformation of cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression characteristics, and induce the deep invasion of the placenta by the spiral arteries, creating large vascular sinuses in the decidua (pseudovasculogenesis). Finally, beta human chorionic gonadotropin production by the placenta stimulates the release of relaxin from the corpus luteum. Many cytokines and growth factors contribute to this normal placental development, but vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) appear to be the most important.

VEGF and PlGF play an integral role in the inducement of conversion of the cytotrophoblast cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression, particularly integrins and cadherins. In models of preeclampsia, there is insufficient invasion of the spiral arteries and inadequate uterine blood flow, as well as a lack of alteration in adhesion molecules of cytotrophoblasts and failed pseudovasculogenesis.9

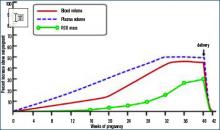

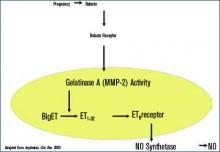

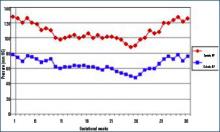

During normal pregnancy, intravascular volume increases, peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) decreases, and renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increase. (See Figure 1, above left.) Concomitant with the increased plasma volume, the reduction of PVR (vasodilation) not only mitigates the effect of plasma volume on systemic blood pressure, but actually reduces the systemic blood pressure during normal pregnancy. (See Figure 2, below.) Based on seminal studies by Jeyabalan and colleagues, one explanation for the decline in PVR and blood pressure, along with the increased renal plasma flow and GFR, is the production and action of relaxin on vascular smooth muscle to stimulate gelatinase-A (matrix metalloproteinase-2), which cleaves bigET (endothelin precursor) to form ET1-32. (See Figure 3, above.) ET1-32 binds to the ETB receptor and increases nitrous oxide (NO) synthetase activity and NO production, leading to vasodilation.10

The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia

Based on this observation of normal pregnancy, the following three lines of investigation have furthered our understanding of the potential pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

1. Because NO appears to play an important role in the normal vasodilation of pregnancy, abnormalities in this vascular regulatory pathway may be critical to the development of hypertension. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) competitively inhibits NO production from arginine by nitric oxide synthetase (NOS). Savvidou and colleagues showed that women with ultrasound evidence of low uterine blood flow were more likely to develop preeclampsia and exhibited higher ADMA levels.11 There was a strong inverse relationship between ADMA levels and flow-mediated vasodilation in women who developed preeclampsia.

Similarly, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH II), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, is strongly expressed in placental tissue. In states of placental insufficiency, one might speculate that levels of DDAH II would be reduced, while ADMA levels would increase. Along this same line of investigation, Noris and colleagues have shown increased arginase II activity in placental tissue from preeclamptic individuals and subsequently reduced levels of L-arginine, a substrate for NO production.12

2. A second line of promising research involves the production of a circulating inhibitor of VEGF. The growth factors VEGF and PlGF are produced by the placenta and affect vascular function by binding to two high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases: kinase insert domain-containing region (KDR) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (Flt-1). Alternative splicing results in the production of an endogenously secreted protein, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sFlt-1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region of the VEGF receptor and cannot become membrane bound, but that binds VEGF and PlGF. Once VEGF has bound to sFlt-1, normal binding to the membrane-bound receptor is inhibited; thus the effects of VEGF are inhibited.

Studies have found that infusion of sFlt-1 to nonpregnant animals causes glomerular endotheliosis and hypertension similar to those found in preeclampsia; these findings support the possibility that sFlt-1 contributes to preeclampsia. Further, Levine and colleagues have shown that plasma sFlt-1 levels increase more in women with preeclampsia and precede clinical findings compared with individuals with normal pregnancies.13 In addition, PlGF levels were decreased in women with preeclampsia compared with the levels found in those experiencing normal pregnancies.

The supposition from these studies is that increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 competitively inhibit VEGF binding to VEGF receptors on vascular tissue. This inhibition causes a lack of vasodilation and increased blood pressure, with the normal fluid retention and volume expansion of pregnancy. VEGF is difficult to accurately determine in plasma, but PlGF levels, which are affected similarly, are reduced in individuals suffering from or destined to develop preeclampsia. Furthermore, since VEGF is an important determinant of normal placental development, decreased cellular binding due to competitive inhibition could contribute to abnormal placental pseudovasculogenesis.

3. Finally, Vu and colleagues have shown that pregnant animals made hypertensive by a high salt diet and deoxycorticosterone administration exhibit a higher circulating level of the Na, K-ATPase inhibitor, marinobufagenin.14 Further, blood pressure is reduced by the administration of the inhibitor of this cardenolide compound, resibufogenin. Though this is not a model of spontaneous preeclampsia, many features are similar, including reduced placental blood flow in spite of volume expansion and proteinuria.

Treatment Recommendations

1. In individuals with hypertension prior to pregnancy, the physician may continue the same anti-hypertensive therapy used pre-pregnancy, with or without diuretics—except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. The goal is to maintain the blood pressure at or below a level of 140/90 mm Hg. The pregnancy should be monitored as a high-risk pregnancy, and urine protein excretion, blood pressure, and fetal health should be monitored frequently, particularly after the 24th week of gestation. Urine protein excretion is most easily monitored using a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A value of less than 0.3 is equivalent to a 24-hour urine excretion of less than 300 mg.

2. Monitor individuals who develop mild preeclampsia for 24-72 hours to assess for progression. If they remain stable, the decision analysis depends on the stage of pregnancy. After 32 weeks gestation, the physician can elect to continue the pregnancy while prescribing reduced activity or bed rest with or without anti-hypertensive therapy. If anti-hypertensive therapy is elected, optimal choices include the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel antagonists, centrally acting alpha 2 agonists such as clonidine, or beta-blockers.

Though diuretics appear safe, most obstetricians do not advocate their use. Most physicians choose to initiate pharmacologic therapy if preeclampsia occurs prior to 32 weeks, in order to allow further fetal development prior to delivery. Many obstetricians will induce labor if the pregnancy is beyond 36 weeks to avoid the complications of preeclampsia/eclampsia. Delivery usually resolves the syndrome of preeclampsia within a period of time that ranges from hours to days.

3. In patients with severe preeclampsia, the risks are greater. In these circumstances, physicians are more likely to induce delivery if gestation is greater than 32 weeks. However, in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks, a physician may choose to delay delivery in order to allow fetal lung maturation, using steroids while controlling blood pressure and preventing seizures with intravenous Mg2SO4. Other options include the use of intravenous labetalol, hydralazine, or even nitroprusside, while also treating the patient with phenytoin to prevent seizures.

4. The presence of the HELLP syndrome usually necessitates urgent delivery and may have prolonged effects on blood pressure, liver function, and compromised renal function after the pregnancy has ended.

As a better understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia develops in the future, more selective and definitive preventive or interventional therapy is likely. As further investigation moves toward that goal, this serious health problem in an otherwise young and healthy population should be mitigated. TH

Dr. Beach is the Paul R. Stalnaker Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine, director, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, and scholar, John McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine.

References

- Longo SA, Dola CP, Pridjian G. Preeclampsia and eclampsia revisited. South Med J. 2003 Sep;96(9): 891-899.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Nov 24;323(7323):1213-1217.

- CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. Lancet. 1994;343:619-629.

- Hofmeyer GJ, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2000;3:CD001059.

- Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985 Jan 5;290 (6461):17-23.

- Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999 May 15;318 (7194):1332-1336.

- Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333 (4):201-205.

- Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, et al. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 23;348 (4):304-311.

- Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;48(2):372-386.

- Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, et al. Essential role for vascular gelatinase activity in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res. 2003 Dec 12;93(12):1249-1257. Epub 2003 Oct 30.

- Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1511-1517.

- Noris M, Todeschini M, Cassis P, et al. L-arginine depletion in preeclampsia orients nitric oxide synthase toward oxidant species. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):614-622. Epub 2004 Jan 26.

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350 (7):672-683. Epub 2004 Feb 5.

- Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, et al. Resibufogenin corrects hypertension in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2006 Feb;231(2):215-220.

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and

- Gestational hypertension: either transient mild hypertension during the third trimester or mild hypertension detected during the third trimester that does not resolve by 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosing Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Of these hypertensive entities, this article focuses on the most common and potentially serious one: preeclampsia/eclampsia. Preeclampsia is characterized by blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg—measured on two separate occasions, and proteinuria greater than 300 mg/24 hours, occurring after 20 weeks gestation. Severe preeclampsia includes the same criteria, as well as proteinuria greater than 5,000 mg/24 hours; blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg; or end-organ damage such as headaches, visual changes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, or thrombocytopenia.

Historically, the term eclampsia has been reserved to describe the symptoms of preeclampsia combined with the occurrence of seizure activity. HELLP syndrome is a severe variant of preeclampsia that affects up to 1% of pregnancies and includes the constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count.

Given the potential risks for these disorders during pregnancy, it seems logical to target primarily those individuals at risk and attempt to prevent the disorder. Traditionally, the higher risk populations include patients experiencing primagravida pregnancies, those with a history of hypertension or renal disease, women who have had prior episodes of preeclampsia, and multiparous individuals with different paternal partners. Other less helpful or more expensive screening procedures include evaluation for inherited thrombophilias.

Recommended Treatment

Several trials have attempted to prevent the development of preeclampsia using calcium supplementation or aspirin therapy, but current evidence demonstrates no benefit from these interventions except in selected populations.3,4 For the past several decades, the treatment for hypertension during pregnancy has consisted of either delivery of the fetus or bed rest combined with therapies involving alpha-methyl-DOPA, hydralazine, and intravenous magnesium sulfate, depending on the level of the patient’s blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as the stage of the pregnancy.

Because of the potential risks to the health of the infant (as well as that of the mother) generic interventional trials extrapolated from other hypertensive populations that may offer equivalent or more effective therapies have not been readily accomplished. In spite of this lack of clinical and outcomes studies, the following generalizations regarding care are currently advocated:

1. Continue anti-hypertensive therapy for chronic hypertension with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Though the risks of SGA infants and preeclampsia were not affected by therapy, the incidence of premature delivery was reduced. Nearly all anti-hypertensive drugs have been used in treating chronic hypertension in pregnancy, but angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated because of teratogenecity. Diuretics and hydralazine may also have adverse outcomes on fetal and/or maternal health, respectively.

Though diuretics may reduce an already compromised placental blood flow by reducing intravascular volume, a number of randomized trials using diuretics have been reported. The population studied in these trials totaled approximately 7,000 individuals, and the results show no demonstrable adverse effects.5 Centrally acting alpha 2 adrenergic agonists (alpha-methyl-DOPA, clonidine), long-acting dihydropyridines (calcium channel blockers), and beta-adrenergic blockers with or without alpha-adrenergic blockade have been used successfully during pregnancy.6 Infants born to mothers receiving beta-blockers have a higher incidence of transient heart block and bradycardia. Newer agents, as opposed to alpha-methyl-DOPA and hydralazine, have not been shown to be more effective in controlling blood pressure but have demonstrated fewer adverse effects or events.

2. Mild preeclampsia may be treated using late-term delivery or bed rest before the pregnancy reaches 36 weeks. Close observation in a hospital is warranted until lack of progression to severe eclampsia is ensured.

3. Severe preeclampsia must be treated using either delivery or interventions to control blood pressure and prevent seizures while delivery is temporarily delayed to allow for fetal maturation. Intravenous magnesium sulfate (Mg2SO4), titrated to therapeutic concentrations of magnesium (4.5-8.5 mg/dl) along with suppression of deep tendon reflexes, has significantly lowered blood pressure and reduced the incidence of seizure activity. In direct comparison with intravenous phenytoin, there were no episodes of eclampsia in patients treated with magnesium (zero of 1,049 patients treated), while 10 of 1,089 individuals treated with phenytoin developed eclampsia.7 Similarly, Mg2SO4 decreased the incidence of eclampsia to 0.8% compared with 2.6% of individuals treated with nimodipine.8 Likewise, Mg2SO4 significantly reduced recurrent seizures compared to diazepam and phenytoin. In patients with renal insufficiency or other relative contraindications to Mg2SO4 therapy, the physician may treat the blood pressure with labetalol or a calcium channel antagonist and provide prophylaxis from seizures using phenytoin.

Because of the lack of a more complete understanding of the etiology (or etiologies) of preeclampsia/eclampsia, we are not fully able to identify individuals who are at risk. With further investigation, we will be able to provide more selective and effective interventions.

Nitrous Oxide’s Vital Role in Pregnancy

In this regard, considerable investigation has been directed toward a better understanding of eclampsia/preeclampsia in the past 20 years. The current discussion will highlight three promising lines of inquiry. Before commenting on these three areas of investigation, we feel it is important to illustrate the fundamental defect observed in all models of preeclampsia. This unifying abnormality is the presence of a placenta with inadequate uterine blood flow.

In a normal pregnancy, after implantation in the uterine wall, cytotrophoblasts invade the uterine wall, undergo a transformation of cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression characteristics, and induce the deep invasion of the placenta by the spiral arteries, creating large vascular sinuses in the decidua (pseudovasculogenesis). Finally, beta human chorionic gonadotropin production by the placenta stimulates the release of relaxin from the corpus luteum. Many cytokines and growth factors contribute to this normal placental development, but vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) appear to be the most important.

VEGF and PlGF play an integral role in the inducement of conversion of the cytotrophoblast cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression, particularly integrins and cadherins. In models of preeclampsia, there is insufficient invasion of the spiral arteries and inadequate uterine blood flow, as well as a lack of alteration in adhesion molecules of cytotrophoblasts and failed pseudovasculogenesis.9

During normal pregnancy, intravascular volume increases, peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) decreases, and renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increase. (See Figure 1, above left.) Concomitant with the increased plasma volume, the reduction of PVR (vasodilation) not only mitigates the effect of plasma volume on systemic blood pressure, but actually reduces the systemic blood pressure during normal pregnancy. (See Figure 2, below.) Based on seminal studies by Jeyabalan and colleagues, one explanation for the decline in PVR and blood pressure, along with the increased renal plasma flow and GFR, is the production and action of relaxin on vascular smooth muscle to stimulate gelatinase-A (matrix metalloproteinase-2), which cleaves bigET (endothelin precursor) to form ET1-32. (See Figure 3, above.) ET1-32 binds to the ETB receptor and increases nitrous oxide (NO) synthetase activity and NO production, leading to vasodilation.10

The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia

Based on this observation of normal pregnancy, the following three lines of investigation have furthered our understanding of the potential pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

1. Because NO appears to play an important role in the normal vasodilation of pregnancy, abnormalities in this vascular regulatory pathway may be critical to the development of hypertension. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) competitively inhibits NO production from arginine by nitric oxide synthetase (NOS). Savvidou and colleagues showed that women with ultrasound evidence of low uterine blood flow were more likely to develop preeclampsia and exhibited higher ADMA levels.11 There was a strong inverse relationship between ADMA levels and flow-mediated vasodilation in women who developed preeclampsia.

Similarly, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH II), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, is strongly expressed in placental tissue. In states of placental insufficiency, one might speculate that levels of DDAH II would be reduced, while ADMA levels would increase. Along this same line of investigation, Noris and colleagues have shown increased arginase II activity in placental tissue from preeclamptic individuals and subsequently reduced levels of L-arginine, a substrate for NO production.12

2. A second line of promising research involves the production of a circulating inhibitor of VEGF. The growth factors VEGF and PlGF are produced by the placenta and affect vascular function by binding to two high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases: kinase insert domain-containing region (KDR) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (Flt-1). Alternative splicing results in the production of an endogenously secreted protein, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sFlt-1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region of the VEGF receptor and cannot become membrane bound, but that binds VEGF and PlGF. Once VEGF has bound to sFlt-1, normal binding to the membrane-bound receptor is inhibited; thus the effects of VEGF are inhibited.

Studies have found that infusion of sFlt-1 to nonpregnant animals causes glomerular endotheliosis and hypertension similar to those found in preeclampsia; these findings support the possibility that sFlt-1 contributes to preeclampsia. Further, Levine and colleagues have shown that plasma sFlt-1 levels increase more in women with preeclampsia and precede clinical findings compared with individuals with normal pregnancies.13 In addition, PlGF levels were decreased in women with preeclampsia compared with the levels found in those experiencing normal pregnancies.

The supposition from these studies is that increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 competitively inhibit VEGF binding to VEGF receptors on vascular tissue. This inhibition causes a lack of vasodilation and increased blood pressure, with the normal fluid retention and volume expansion of pregnancy. VEGF is difficult to accurately determine in plasma, but PlGF levels, which are affected similarly, are reduced in individuals suffering from or destined to develop preeclampsia. Furthermore, since VEGF is an important determinant of normal placental development, decreased cellular binding due to competitive inhibition could contribute to abnormal placental pseudovasculogenesis.

3. Finally, Vu and colleagues have shown that pregnant animals made hypertensive by a high salt diet and deoxycorticosterone administration exhibit a higher circulating level of the Na, K-ATPase inhibitor, marinobufagenin.14 Further, blood pressure is reduced by the administration of the inhibitor of this cardenolide compound, resibufogenin. Though this is not a model of spontaneous preeclampsia, many features are similar, including reduced placental blood flow in spite of volume expansion and proteinuria.

Treatment Recommendations

1. In individuals with hypertension prior to pregnancy, the physician may continue the same anti-hypertensive therapy used pre-pregnancy, with or without diuretics—except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. The goal is to maintain the blood pressure at or below a level of 140/90 mm Hg. The pregnancy should be monitored as a high-risk pregnancy, and urine protein excretion, blood pressure, and fetal health should be monitored frequently, particularly after the 24th week of gestation. Urine protein excretion is most easily monitored using a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A value of less than 0.3 is equivalent to a 24-hour urine excretion of less than 300 mg.

2. Monitor individuals who develop mild preeclampsia for 24-72 hours to assess for progression. If they remain stable, the decision analysis depends on the stage of pregnancy. After 32 weeks gestation, the physician can elect to continue the pregnancy while prescribing reduced activity or bed rest with or without anti-hypertensive therapy. If anti-hypertensive therapy is elected, optimal choices include the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel antagonists, centrally acting alpha 2 agonists such as clonidine, or beta-blockers.

Though diuretics appear safe, most obstetricians do not advocate their use. Most physicians choose to initiate pharmacologic therapy if preeclampsia occurs prior to 32 weeks, in order to allow further fetal development prior to delivery. Many obstetricians will induce labor if the pregnancy is beyond 36 weeks to avoid the complications of preeclampsia/eclampsia. Delivery usually resolves the syndrome of preeclampsia within a period of time that ranges from hours to days.

3. In patients with severe preeclampsia, the risks are greater. In these circumstances, physicians are more likely to induce delivery if gestation is greater than 32 weeks. However, in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks, a physician may choose to delay delivery in order to allow fetal lung maturation, using steroids while controlling blood pressure and preventing seizures with intravenous Mg2SO4. Other options include the use of intravenous labetalol, hydralazine, or even nitroprusside, while also treating the patient with phenytoin to prevent seizures.

4. The presence of the HELLP syndrome usually necessitates urgent delivery and may have prolonged effects on blood pressure, liver function, and compromised renal function after the pregnancy has ended.

As a better understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia develops in the future, more selective and definitive preventive or interventional therapy is likely. As further investigation moves toward that goal, this serious health problem in an otherwise young and healthy population should be mitigated. TH

Dr. Beach is the Paul R. Stalnaker Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine, director, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, and scholar, John McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine.

References

- Longo SA, Dola CP, Pridjian G. Preeclampsia and eclampsia revisited. South Med J. 2003 Sep;96(9): 891-899.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Nov 24;323(7323):1213-1217.

- CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. Lancet. 1994;343:619-629.

- Hofmeyer GJ, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2000;3:CD001059.

- Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985 Jan 5;290 (6461):17-23.

- Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999 May 15;318 (7194):1332-1336.

- Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333 (4):201-205.

- Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, et al. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 23;348 (4):304-311.

- Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;48(2):372-386.

- Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, et al. Essential role for vascular gelatinase activity in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res. 2003 Dec 12;93(12):1249-1257. Epub 2003 Oct 30.

- Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1511-1517.

- Noris M, Todeschini M, Cassis P, et al. L-arginine depletion in preeclampsia orients nitric oxide synthase toward oxidant species. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):614-622. Epub 2004 Jan 26.

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350 (7):672-683. Epub 2004 Feb 5.

- Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, et al. Resibufogenin corrects hypertension in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2006 Feb;231(2):215-220.

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and