User login

Match Day 2020: Online announcements replace celebrations, champagne

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

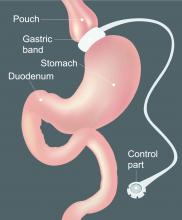

The hospitalized postbariatric surgery patient

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

What every hospitalist should know

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

Feds tout drug candidates to treat COVID-19

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

20% of U.S. COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

Real-world shortages not addressed in new COVID-19 guidance

Newly updated guidance on treating patients with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has been published by the World Health Organization.

While it can’t replace clinical judgment or specialist consultation, the new guidance may help strengthen the clinical management of patients when COVID-19 is suspected, according to its authors.

The guidance, adapted from an earlier edition focused on the management of suspected Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), covers best practices for triage, infection prevention and control, and optimized supportive care for mild, severe, or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

“This guidance should serve as a foundation for optimized supportive care to ensure the best possible chance for survival,” the authors wrote in the guidance.

While the WHO guidance does provide solid facts to support best practices for managing COVID-19, providers will also need to look beyond the document to tackle real-world issues, said David M. Ferraro, MD, FCCP, a pulmonary and critical care physician and associate professor of medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

For example, while the guidelines address the importance of screening and triage, limited COVID-19 testing may be a barrier to timely diagnoses that might compel more individuals to comply with social distancing recommendations, according to Dr. Ferraro, vice chair of the Fundamental Disaster Management Committee for the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM).

“If we’re not providing people with confirmation that they have the virus, they may potentially continue to be spreaders of the disease, because they don’t have that absolute proof,” Dr. Ferraro said in an interview. “I think that’s where we are limited right now, because often we’re not able to tell the mild symptomatic people – or even the asymptomatic people – that they really need to play a role in preventing further spread.”