User login

Novel score spots high-risk febrile children in ED

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A new age-adjusted quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score designed for use in children presenting to the ED with fever showed good predictive value for admission to critical care within the next 48 hours, Aakash Khanijau, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“In the needle-in-a-haystack scenario that’s seen in pediatric emergency departments, our novel, age-adjusted qSOFA score could potentially improve the rapid identification and treatment of children with suspected sepsis presenting to the ED,” said Dr. Khanijau of the University of Liverpool (England).

He presented an exceptionally large retrospective validation study of the score’s performance in 12,393 children (median age, 2.5 years) who presented to EDs with fever, of whom 1,521 were admitted for suspected sepsis. Of the hospitalized children, 145 were admitted to critical care within the first 48 hours.

The pediatric qSOFA score had 72% sensitivity and 85% specificity for critical care admission within 48 hours, with a positive predictive value of 5.4% and, more importantly, a whopping negative predictive value of 99.6%.

“That very high negative predictive value underlines the powerful discriminatory nature of our tool in the emergency department setting,” Dr. Khanijau observed, adding that the score’s area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.81, which is considered a good predictive value.

The impetus for developing an age-adjusted pediatric qSOFA score stems from the fact that the original qSOFA score was designed for rapid assessment of adults with suspected sepsis and isn’t applicable in children. Other existing scores, including SIRS (the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria), the full SOFA, and PELOD-2 (the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score), take longer to determine than the adapted qSOFA in a setting where speed is of the essence, he explained.

The original qSOFA components are altered mentation, systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate. The novel score developed by Dr. Khanijau and coworkers swaps out systolic BP in favor of capillary refill time and age-adjusted heart rate using the thresholds previously established in a landmark study from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131[4]:e1150-7.)

“Our reasoning here is that arterial hypertension is known to be a much later sign of circulatory compromise in children and may provide less discriminatory value than signs such as delayed capillary refill time and tachycardia early in presentation in the emergency department,” according to Dr. Khanijau.

The novel scoring system features four criteria. One point each is given for a capillary refill time of 3 seconds or longer; anything less than “Alert” on the Alert, Responds to Voice, Respond to Pain, and Unresponsive scale; a heart rate above the 99th percentile on the age-adjusted curves; and a respiratory rate above the age-adjusted 99th percentile. Thus, scores can range from 0 to 4. In the validation study, a score of 2 or more spelled a 890% increased likelihood of being admitted to a critical care setting within 48 hours. It was also associated with a 100-fold increased likelihood of death during the hospitalization, which occurred in 10 children.

Asked how the new predictive score could change clinical management, Dr. Khanijau replied, “I think the key thing it does here is it identifies the children at risk of requiring critical care and should therefore motivate us in the children achieving that threshold to promptly investigate thoroughly for suspected sepsis using the more comprehensive tools, like the full SOFA.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

SOURCE: Khanijau A et al. ESPID 2019, Abstract.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A new age-adjusted quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score designed for use in children presenting to the ED with fever showed good predictive value for admission to critical care within the next 48 hours, Aakash Khanijau, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“In the needle-in-a-haystack scenario that’s seen in pediatric emergency departments, our novel, age-adjusted qSOFA score could potentially improve the rapid identification and treatment of children with suspected sepsis presenting to the ED,” said Dr. Khanijau of the University of Liverpool (England).

He presented an exceptionally large retrospective validation study of the score’s performance in 12,393 children (median age, 2.5 years) who presented to EDs with fever, of whom 1,521 were admitted for suspected sepsis. Of the hospitalized children, 145 were admitted to critical care within the first 48 hours.

The pediatric qSOFA score had 72% sensitivity and 85% specificity for critical care admission within 48 hours, with a positive predictive value of 5.4% and, more importantly, a whopping negative predictive value of 99.6%.

“That very high negative predictive value underlines the powerful discriminatory nature of our tool in the emergency department setting,” Dr. Khanijau observed, adding that the score’s area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.81, which is considered a good predictive value.

The impetus for developing an age-adjusted pediatric qSOFA score stems from the fact that the original qSOFA score was designed for rapid assessment of adults with suspected sepsis and isn’t applicable in children. Other existing scores, including SIRS (the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria), the full SOFA, and PELOD-2 (the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score), take longer to determine than the adapted qSOFA in a setting where speed is of the essence, he explained.

The original qSOFA components are altered mentation, systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate. The novel score developed by Dr. Khanijau and coworkers swaps out systolic BP in favor of capillary refill time and age-adjusted heart rate using the thresholds previously established in a landmark study from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131[4]:e1150-7.)

“Our reasoning here is that arterial hypertension is known to be a much later sign of circulatory compromise in children and may provide less discriminatory value than signs such as delayed capillary refill time and tachycardia early in presentation in the emergency department,” according to Dr. Khanijau.

The novel scoring system features four criteria. One point each is given for a capillary refill time of 3 seconds or longer; anything less than “Alert” on the Alert, Responds to Voice, Respond to Pain, and Unresponsive scale; a heart rate above the 99th percentile on the age-adjusted curves; and a respiratory rate above the age-adjusted 99th percentile. Thus, scores can range from 0 to 4. In the validation study, a score of 2 or more spelled a 890% increased likelihood of being admitted to a critical care setting within 48 hours. It was also associated with a 100-fold increased likelihood of death during the hospitalization, which occurred in 10 children.

Asked how the new predictive score could change clinical management, Dr. Khanijau replied, “I think the key thing it does here is it identifies the children at risk of requiring critical care and should therefore motivate us in the children achieving that threshold to promptly investigate thoroughly for suspected sepsis using the more comprehensive tools, like the full SOFA.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

SOURCE: Khanijau A et al. ESPID 2019, Abstract.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A new age-adjusted quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score designed for use in children presenting to the ED with fever showed good predictive value for admission to critical care within the next 48 hours, Aakash Khanijau, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“In the needle-in-a-haystack scenario that’s seen in pediatric emergency departments, our novel, age-adjusted qSOFA score could potentially improve the rapid identification and treatment of children with suspected sepsis presenting to the ED,” said Dr. Khanijau of the University of Liverpool (England).

He presented an exceptionally large retrospective validation study of the score’s performance in 12,393 children (median age, 2.5 years) who presented to EDs with fever, of whom 1,521 were admitted for suspected sepsis. Of the hospitalized children, 145 were admitted to critical care within the first 48 hours.

The pediatric qSOFA score had 72% sensitivity and 85% specificity for critical care admission within 48 hours, with a positive predictive value of 5.4% and, more importantly, a whopping negative predictive value of 99.6%.

“That very high negative predictive value underlines the powerful discriminatory nature of our tool in the emergency department setting,” Dr. Khanijau observed, adding that the score’s area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.81, which is considered a good predictive value.

The impetus for developing an age-adjusted pediatric qSOFA score stems from the fact that the original qSOFA score was designed for rapid assessment of adults with suspected sepsis and isn’t applicable in children. Other existing scores, including SIRS (the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria), the full SOFA, and PELOD-2 (the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score), take longer to determine than the adapted qSOFA in a setting where speed is of the essence, he explained.

The original qSOFA components are altered mentation, systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate. The novel score developed by Dr. Khanijau and coworkers swaps out systolic BP in favor of capillary refill time and age-adjusted heart rate using the thresholds previously established in a landmark study from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131[4]:e1150-7.)

“Our reasoning here is that arterial hypertension is known to be a much later sign of circulatory compromise in children and may provide less discriminatory value than signs such as delayed capillary refill time and tachycardia early in presentation in the emergency department,” according to Dr. Khanijau.

The novel scoring system features four criteria. One point each is given for a capillary refill time of 3 seconds or longer; anything less than “Alert” on the Alert, Responds to Voice, Respond to Pain, and Unresponsive scale; a heart rate above the 99th percentile on the age-adjusted curves; and a respiratory rate above the age-adjusted 99th percentile. Thus, scores can range from 0 to 4. In the validation study, a score of 2 or more spelled a 890% increased likelihood of being admitted to a critical care setting within 48 hours. It was also associated with a 100-fold increased likelihood of death during the hospitalization, which occurred in 10 children.

Asked how the new predictive score could change clinical management, Dr. Khanijau replied, “I think the key thing it does here is it identifies the children at risk of requiring critical care and should therefore motivate us in the children achieving that threshold to promptly investigate thoroughly for suspected sepsis using the more comprehensive tools, like the full SOFA.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

SOURCE: Khanijau A et al. ESPID 2019, Abstract.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Procalcitonin advocated to help rule out bacterial infections

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PHM 2019

Algorithm boosts MACE prediction in patients with chest pain

Adding electrocardiogram findings and clinical assessment to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements in patients presenting with chest pain could improve predictions of their risk of 30-day major adverse cardiac events, particularly unstable angina, research suggests.

Investigators reported outcomes of a prospective study involving 3,123 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. The findings are in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The aim of the researchers was to validate an extended algorithm that combined the European Society of Cardiology’s high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurement at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm) with clinical assessment and ECG findings to aid prediction of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) within 30 days.

The clinical assessment involved the treating ED physician’s use of a visual analog scale to assess the patient’s pretest probability for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), with a score above 70% qualifying as high likelihood.

The researchers found that the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone triaged significantly more patients toward rule-out for MACE than did the extended algorithm (60% vs. 45%, P less than .001). This resulted in 487 patients being reclassified toward “observe” by the extended algorithm, and among this group the 30-day MACE rate was 1.1%.

However, the 30-day MACE rates were similar in the two groups – 0.6% among those ruled out by the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone and 0.4% in those ruled out by the extended algorithm – resulting in a similar negative predictive value.

“These estimates will help clinicians to appropriately manage patients triaged toward rule-out according to the ESC hs-cTnT 0/1 h algorithm, in whom either the [visual analog scale] for ACS or the ECG still suggests the presence of an ACS,” wrote Thomas Nestelberger, MD, of the Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel (Switzerland) at the University of Basel, and coinvestigators.

The ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm also ruled in fewer patients than did the extended algorithm (16% vs. 26%, P less than .001), giving it a higher positive predictive value.

When the researchers added unstable angina to the major adverse cardiac event outcome, they found the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm had a lower negative predictive value and a higher negative likelihood ratio compared with the extended algorithm for patients ruled out, but a higher positive predictive value and positive likelihood ratio for patients ruled in.

“Our findings corroborate and extend previous research regarding the development and validation of algorithms for the safe and effective rule-out and rule-in of MACE in patients with symptoms suggestive of AMI,” the authors wrote.

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University Hospital Basel, Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Biomerieux, BRAHMS, Roche, Nanosphere, Siemens, Ortho Diagnostics, and Singulex. Several authors reported grants and support from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCE: Nestelberger T et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.025.

In patients presenting at the emergency department with chest pain, it’s important not only to diagnose acute myocardial infarction, but also to predict short-term risk of cardiac events to help guide management. This thoughtful and comprehensive analysis is the largest study assessing the added value of clinical and ECG assessment to the prognostication by high-sensitivity cardiac troponin algorithms in patients evaluated for chest pain. It reinforces the accuracy of hs-cTn at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h) algorithms to predict AMI and 30-day AMI-related events.

It is important to note that if unstable angina had been included as a major adverse cardiac event, the study would have found that the extended algorithm performs better than the hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm in the prediction of this endpoint.

Germán Cediel, MD, is from Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol in Spain, Alfredo Bardají, MD, is from the Joan XXIII University Hospital in Spain, and José A. Barrabés, MD, is from Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Research Institute, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. The comments are adapted from an editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.065). The authors declared support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund, and declared consultancies and educational activities with the pharmaceutical sector.

In patients presenting at the emergency department with chest pain, it’s important not only to diagnose acute myocardial infarction, but also to predict short-term risk of cardiac events to help guide management. This thoughtful and comprehensive analysis is the largest study assessing the added value of clinical and ECG assessment to the prognostication by high-sensitivity cardiac troponin algorithms in patients evaluated for chest pain. It reinforces the accuracy of hs-cTn at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h) algorithms to predict AMI and 30-day AMI-related events.

It is important to note that if unstable angina had been included as a major adverse cardiac event, the study would have found that the extended algorithm performs better than the hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm in the prediction of this endpoint.

Germán Cediel, MD, is from Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol in Spain, Alfredo Bardají, MD, is from the Joan XXIII University Hospital in Spain, and José A. Barrabés, MD, is from Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Research Institute, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. The comments are adapted from an editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.065). The authors declared support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund, and declared consultancies and educational activities with the pharmaceutical sector.

In patients presenting at the emergency department with chest pain, it’s important not only to diagnose acute myocardial infarction, but also to predict short-term risk of cardiac events to help guide management. This thoughtful and comprehensive analysis is the largest study assessing the added value of clinical and ECG assessment to the prognostication by high-sensitivity cardiac troponin algorithms in patients evaluated for chest pain. It reinforces the accuracy of hs-cTn at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h) algorithms to predict AMI and 30-day AMI-related events.

It is important to note that if unstable angina had been included as a major adverse cardiac event, the study would have found that the extended algorithm performs better than the hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm in the prediction of this endpoint.

Germán Cediel, MD, is from Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol in Spain, Alfredo Bardají, MD, is from the Joan XXIII University Hospital in Spain, and José A. Barrabés, MD, is from Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Research Institute, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. The comments are adapted from an editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.065). The authors declared support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund, and declared consultancies and educational activities with the pharmaceutical sector.

Adding electrocardiogram findings and clinical assessment to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements in patients presenting with chest pain could improve predictions of their risk of 30-day major adverse cardiac events, particularly unstable angina, research suggests.

Investigators reported outcomes of a prospective study involving 3,123 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. The findings are in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The aim of the researchers was to validate an extended algorithm that combined the European Society of Cardiology’s high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurement at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm) with clinical assessment and ECG findings to aid prediction of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) within 30 days.

The clinical assessment involved the treating ED physician’s use of a visual analog scale to assess the patient’s pretest probability for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), with a score above 70% qualifying as high likelihood.

The researchers found that the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone triaged significantly more patients toward rule-out for MACE than did the extended algorithm (60% vs. 45%, P less than .001). This resulted in 487 patients being reclassified toward “observe” by the extended algorithm, and among this group the 30-day MACE rate was 1.1%.

However, the 30-day MACE rates were similar in the two groups – 0.6% among those ruled out by the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone and 0.4% in those ruled out by the extended algorithm – resulting in a similar negative predictive value.

“These estimates will help clinicians to appropriately manage patients triaged toward rule-out according to the ESC hs-cTnT 0/1 h algorithm, in whom either the [visual analog scale] for ACS or the ECG still suggests the presence of an ACS,” wrote Thomas Nestelberger, MD, of the Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel (Switzerland) at the University of Basel, and coinvestigators.

The ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm also ruled in fewer patients than did the extended algorithm (16% vs. 26%, P less than .001), giving it a higher positive predictive value.

When the researchers added unstable angina to the major adverse cardiac event outcome, they found the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm had a lower negative predictive value and a higher negative likelihood ratio compared with the extended algorithm for patients ruled out, but a higher positive predictive value and positive likelihood ratio for patients ruled in.

“Our findings corroborate and extend previous research regarding the development and validation of algorithms for the safe and effective rule-out and rule-in of MACE in patients with symptoms suggestive of AMI,” the authors wrote.

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University Hospital Basel, Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Biomerieux, BRAHMS, Roche, Nanosphere, Siemens, Ortho Diagnostics, and Singulex. Several authors reported grants and support from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCE: Nestelberger T et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.025.

Adding electrocardiogram findings and clinical assessment to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements in patients presenting with chest pain could improve predictions of their risk of 30-day major adverse cardiac events, particularly unstable angina, research suggests.

Investigators reported outcomes of a prospective study involving 3,123 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. The findings are in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The aim of the researchers was to validate an extended algorithm that combined the European Society of Cardiology’s high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurement at presentation and after 1 hour (ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm) with clinical assessment and ECG findings to aid prediction of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) within 30 days.

The clinical assessment involved the treating ED physician’s use of a visual analog scale to assess the patient’s pretest probability for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), with a score above 70% qualifying as high likelihood.

The researchers found that the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone triaged significantly more patients toward rule-out for MACE than did the extended algorithm (60% vs. 45%, P less than .001). This resulted in 487 patients being reclassified toward “observe” by the extended algorithm, and among this group the 30-day MACE rate was 1.1%.

However, the 30-day MACE rates were similar in the two groups – 0.6% among those ruled out by the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm alone and 0.4% in those ruled out by the extended algorithm – resulting in a similar negative predictive value.

“These estimates will help clinicians to appropriately manage patients triaged toward rule-out according to the ESC hs-cTnT 0/1 h algorithm, in whom either the [visual analog scale] for ACS or the ECG still suggests the presence of an ACS,” wrote Thomas Nestelberger, MD, of the Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel (Switzerland) at the University of Basel, and coinvestigators.

The ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm also ruled in fewer patients than did the extended algorithm (16% vs. 26%, P less than .001), giving it a higher positive predictive value.

When the researchers added unstable angina to the major adverse cardiac event outcome, they found the ESC hs-cTn 0/1 h algorithm had a lower negative predictive value and a higher negative likelihood ratio compared with the extended algorithm for patients ruled out, but a higher positive predictive value and positive likelihood ratio for patients ruled in.

“Our findings corroborate and extend previous research regarding the development and validation of algorithms for the safe and effective rule-out and rule-in of MACE in patients with symptoms suggestive of AMI,” the authors wrote.

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University Hospital Basel, Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Biomerieux, BRAHMS, Roche, Nanosphere, Siemens, Ortho Diagnostics, and Singulex. Several authors reported grants and support from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCE: Nestelberger T et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.025.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements combined with ECG and clinical assessment can help rule out MACE and unstable angina.

Study details: A prospective study of 3,123 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University Hospital Basel, Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Biomerieux, BRAHMS, Roche, NanoSphere, Siemens, Ortho Diagnostics, and Singulex. Several authors reported grants and support from the pharmaceutical sector.

Source: Nestelberger T et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.025.

PTSD in the inpatient setting

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

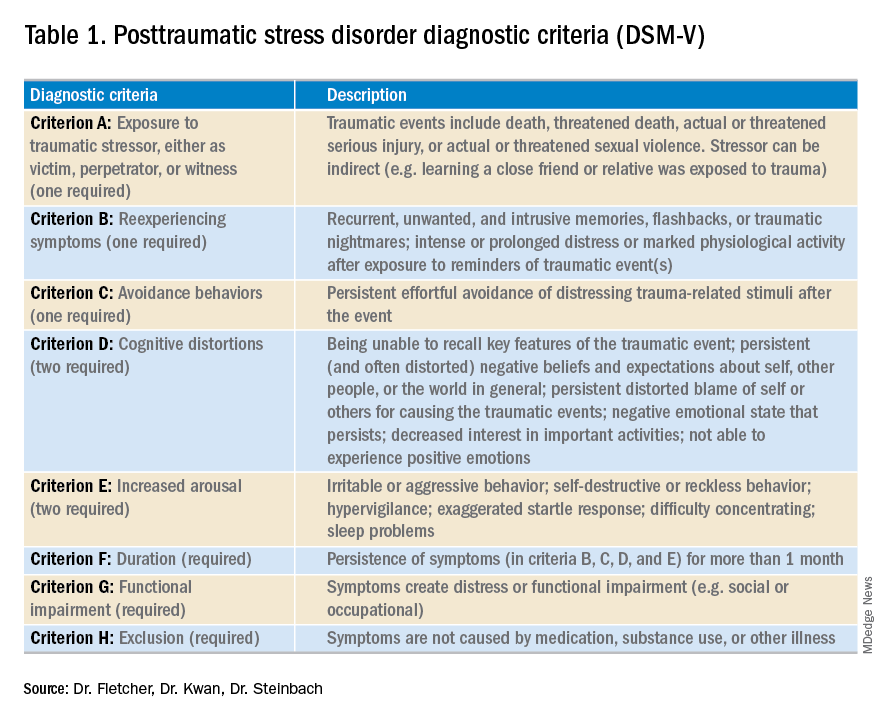

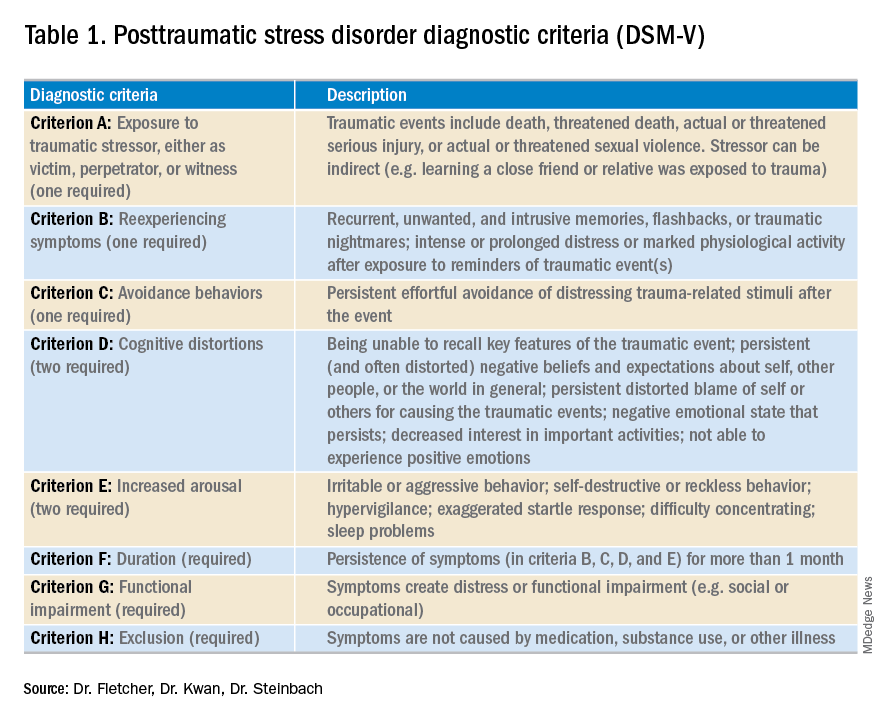

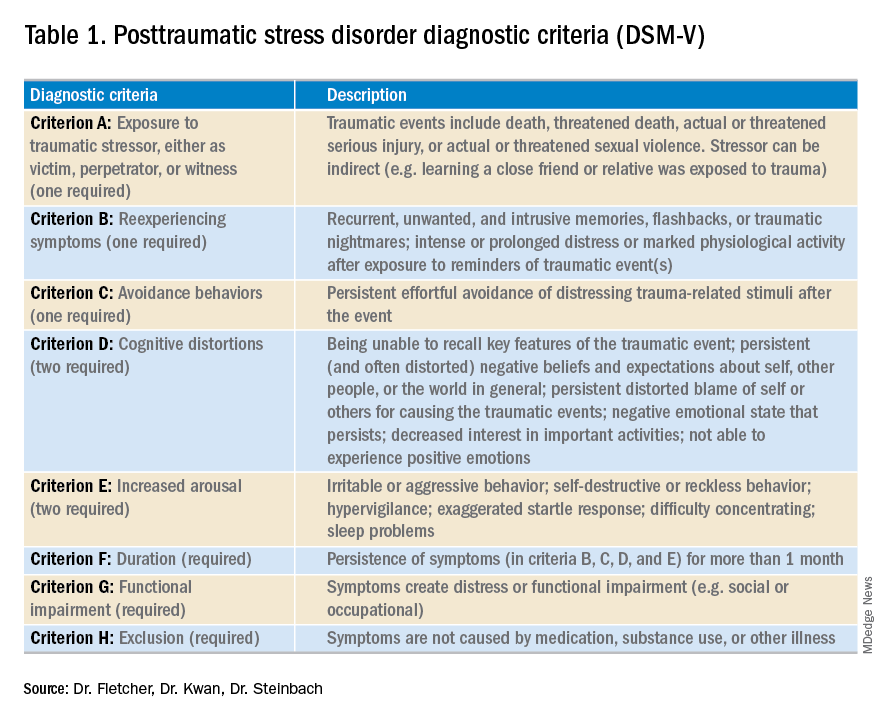

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

A problem hiding in plain sight

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

The changing landscape of medical education

A brave new world

It’s Monday morning, and your intern is presenting an overnight admission. Lost in the details of his disorganized introduction, your mind wanders. “Why doesn’t this intern know how to present? When I trained, all those admissions during long sleepless nights really taught me to do this right.” But can we equate hours worked with competency achieved? And if not, what is the alternative? This article introduces some major changes in medical education and their implications for hospitalists.

Most hospitalists trained in an educational system influenced by Sir William Osler. In the early 1900s, he introduced the natural method of teaching, positing that student exposure to patients and experience over time ensured that physicians in training would become competent doctors.1 His influence led to the current structure of medical education, which includes conventional third-year clerkships and time-limited rotations (such as a 2-week nephrology block).

While familiarity may be comforting, there are signs our current model of medical education is inefficient, inadequate, and obsolete.

For one, the traditional system is failing to adequately prepare physicians to provide safe and complex care. Reports, such as the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) “To Err is Human,”2 describe a high rate of preventable errors, highlighting considerable room for improvement in training the next generation of physicians.3,4

Meanwhile, trainees are still largely being deemed ready for the workforce by length of training completed (for example, completion of four-year medical school) rather than a skill set distinctly achieved. Our system leaves little flexibility to individualize learner goals, which is significant given some students and residents take shorter or longer periods of time to achieve proficiency. In addition, learner outcomes can be quite variable, as we have all experienced.

Even our methods of assessment may not adequately evaluate trainees’ skill sets. For example, most clerkships still rely heavily on the shelf exam5 as a surrogate for medical knowledge. As such, learners may conclude that testing performance trumps development of other professional skills.6 Efforts are being made to revamp evaluation systems to reflect mastery (such as Entrustable Professional Activities, or EPAs) toward competencies.7 Still, many institutions continue to rely on faculty evaluations that often reflect interpersonal dynamics rather than true critical thinking skills.6

Recognizing the above limitations, many educators have called for changing to outcome-based, or competency-based, training (CBME). CBME targets attainment of skills in performing concrete critical clinical activities,8 such as identifying unstable patients, providing initial management, and obtaining help. To be successful, supervisors must directly observe trainees, assess demonstrated skills, and provide feedback about progress.

Unfortunately, this considerable investment of time and effort is often poorly compensated. Additionally, unanswered questions remain. For example, how will residency programs continue to challenge physicians deemed “competent” in a required skill? What happens when a trainee is deficient and not appropriately progressing in a required skill? Is flexible training time part of the future of medical education? While CBME appears to be a more effective method of education, questions like these must be addressed during implementation.

Beyond the fact that hours worked cannot be used as a surrogate for competency, excessive unregulated work hours can be detrimental to learners, their supervisors, and patients. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented a major change in medical education: duty hour limitations. The premise that sleep-deprived providers are more prone to error is well established. However, controversy remains as to whether these regulations translate into improved patient care and provider well-being. Studies published following the ACGME change demonstrate increasing burnout among physicians,9-11 which has led some educators to explore the potential relationship between burnout and duty hour restrictions.

The recent “iCOMPARE” trial, which compared internal medicine (IM) residencies with “standard duty-hour” policies to those with “flexible” policies (that is, they did not specify limits on shift length or mandatory time off between shifts), supported a lack of correlation between hours worked and burnout.12 Researchers administered the Maslach Burnout Inventory to all participants.13 While those in the “flexible hours” arm reported greater dissatisfaction with the effect of the program on their personal lives, both groups reported significant burnout, with interns recording high scores in emotional exhaustion (79% in flexible programs vs. 72% in standard), depersonalization (75% vs. 72%), and lack of personal accomplishment (71% vs. 69%).

Disturbingly, these scores were not restricted to interns but were present in all residents. The good news? Limiting duty hours does not cause burnout. On the other hand, it does not protect from burnout. Trainee burnout appears to transcend the issue of hours worked. Clearly, we need to address the systemic flaws in our work environments that contribute to this epidemic. Nationwide, educators and organizations are continuing to define causes of burnout and test interventions to improve wellness.

A final front of change in medical education worth mentioning is the use of the electronic medical record (EMR). While the EMR has improved many aspects of patient care, its implementation is associated with decreased time spent with patients and parallels the rise in burnout. Another unforeseen consequence has been its disruptive impact on medical student documentation. A national survey of clerkship directors found that, while 64% of programs allowed students to use the EMR, only two-thirds of those programs permitted students to document electronically.14

Many institutions limit student access because of either liability concerns or the fact that student notes cannot be used to support medical billing. Concerning workarounds among preceptors, such as logging in students under their own credentials to write notes, have been identified.15 Yet medical students need to learn how to document a clinical encounter and maintain medical records.7,16 Authoring notes engages students, promotes a sense of patient ownership, and empowers them to feel like essential team members. Participating in the EMR also allows for critical feedback and skill development.