User login

Poor sleep due to ADHD or ADHD due to poor sleep?

The day wouldn’t be so bad if he would just go to sleep at night! How many times have you heard this plea from parents of your patients with ADHD? Sleep is important for everyone, but getting enough is both more important and more difficult for children with ADHD. About three-quarters of children with ADHD have significant problems with sleep, most even before any medication treatment. And inadequate sleep can exacerbate or even cause ADHD symptoms!

Solving sleep problems for children with ADHD is not always simple. The kinds of sleep issues that are more common in children (and adults) with ADHD, compared with typical children, include behavioral bedtime resistance, circadian rhythm sleep disorder (CRSD), insomnia, morning sleepiness, night waking, periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), restless leg syndrome (RLS), and sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Such a broad differential means a careful history and sometimes even lab studies may be needed.

Both initial and follow-up visits for ADHD should include a sleep history or, ideally, a tool such as BEARS sleep screening tool or Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire and a 2-week sleep diary (http://www.sleepfoundation.org/). These are good ways to collect signs of allergies or apnea (for SDB), limb movements or limb pain (for RLS or PLMD), mouth breathing, night waking, and snoring.

You also need to ask about alcohol, drugs, caffeine, and nicotine; asthma; comorbid conditions such as mental health disorders or their treatments; and enuresis (alone or part of nocturnal seizures).

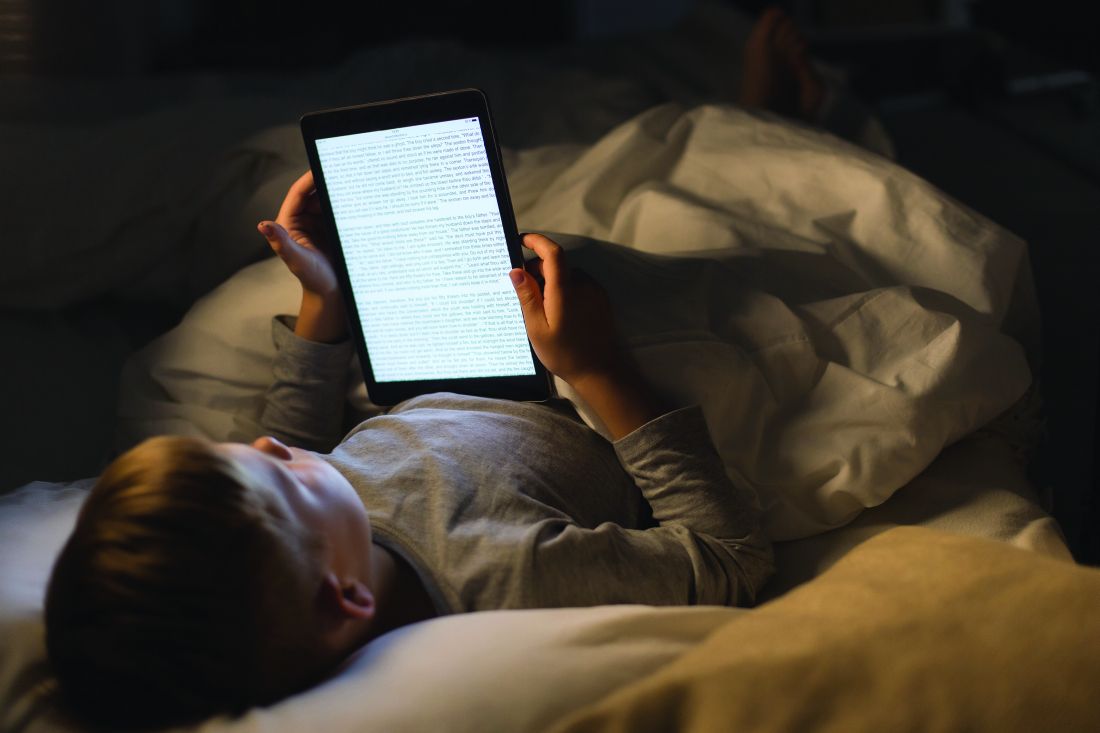

Do I need to remind you to find out about electronics activating the child before bedtime – hidden under the covers, or signaling messages from friends in the middle of the night – and to encourage limits on these? Some sleep disorders warrant polysomnography in a sleep lab or from MyZeo.com (for PLMD and some SDB) or ferritin less than 50 mg/L (for RLS) for diagnosis and to guide treatment. Nasal steroids, antihistamines, or montelukast may help SDB when there are enlarged tonsils or adenoids, but adenotonsillectomy is usually curative.

The first line and most effective treatment for sleep problems in children with or without ADHD is improving sleep hygiene. The key component is establishing habits for the entire sleep cycle: a steady pattern of reduced stimulation in the hour before bedtime (sans electronics); a friendly rather than irritated bedtime routine; and the same bedtime and wake up time, ideally 7 days per week. Bedtime stories read to the child can soothe at any age, not just toddlers! Of course, both children and families want fun and special occasions. For most, varying bedtime by up to 1 hour won’t mess up their biological clock, but for some even this should be avoided. Sleeping alone in a cool, dark, quiet room, nightly in the same bed (not used for other activities), is considered the ideal. Earplugs, white noise generators, and eye masks may be helpful. If sleeping with siblings is a necessity, bedtimes can be staggered to put the child to bed earlier or after others are asleep.

Struggles postponing bedtime may be part of a pattern of oppositionality common in ADHD, but the child may not be tired due to being off schedule (from CRSD), napping on the bus or after school, sleeping in mornings, or unrealistic parent expectations for sleep duration. Parents may want their hyperactive children to give them a break and go to bed at 8 p.m., but children aged 6-10 years need only 10-11 hours and those aged 10-17 years need 8.5-9.25 hours of sleep.

Not tired may instead be “wired” from lingering stimulant effects or even lack of such medication leaving the child overactive or rebounding from earlier medications. Lower afternoon doses or shorter-acting medication may solve lasting medication issues, but sometimes an additional low dose of stimulants actually will help a child with ADHD settle at bedtime. All stimulant medications can prolong sleep onset, often by 30 minutes, but this varies by individual and tends to resolve on its own a few weeks after a new or changed medicine. Switching medication category may allow a child to fall asleep faster. Atomoxetine and alpha agonists are less likely to delay sleep than methylphenidate (MPH).

What if sleep hygiene, behavioral methods, and adjusting ADHD medications is not enough? If sleep issues are causing significant problems, medication for sleep is worth a try. Controlled-release melatonin 1-2 hours before bedtime has data for effectiveness. There is no defined dose, so the lowest effective dose should be used, but 3-6 mg may be needed. Because many families with a child with ADHD are not organized enough to give medicine on this schedule, sublingual melatonin that acts in 15-20 minutes is a good alternative or even first choice. Clonidine 0.05-0.2 mg 1 hour before bedtime speeds sleep onset, lasts 3 hours, and does not carry over to sedation the next day. Stronger psychopharmaceuticals can assist sleep onset, including low dose mirtazapine or trazodone, but have the side effect of daytime sleepiness.

Management of waking in the middle of the night can be more difficult to treat as sleep drive has been dissipated. First, consider whether trips out of bed reflect a sleep association that has not been extinguished. Daytime atomoxetine or, better yet, MPH may improve night waking, and sometimes even a low-dose evening, long-acting medication, such as osmotic release oral system (OROS) extended release methylphenidate HCL (OROS MPH), helps. Short-acting clonidine or melatonin in the middle of the night or bedtime mirtazapine or trazodone also may be worth a try.

When dealing with sleep, keep in mind that 50% or more of children with ADHD have a coexisting mental health disorder. Anxiety, separation anxiety, depression, and dysthymia all often affect sleep onset, night waking, and sometimes early morning waking. The child or teen may need extra reassurance or company at bedtime (siblings or pets may suffice). Reading positive stories or playing soft music may be better at setting a positive mood and sense of safety for sleep, certainly more so than social media, which should be avoided.

Keep in mind that substance use is more common in ADHD as well as with those other mental health conditions and can interfere with restful sleep and make RLS worse. Bipolar disorder can be mistaken for ADHD as it often presents with hyperactivity but also can be comorbid. Sleep problems are increased sixfold when both are present. Prolonged periods awake at night and diminished need for sleep are signs that help differentiate bipolar from ADHD. Medication management for the bipolar disorder with atypicals can reduce sleep latency and reduce REM sleep, but also causes morning fatigue. Medications to treat other mental health problems can help sleep onset (for example, anticonvulsants, atypicals), or prolong it (SSRIs), change REM states (atypicals), and even exacerbate RLS (SSRIs). You can make changes or work with the child’s mental health specialist if medications are causing significant sleep problems.

When we help improve sleep for children with ADHD, it can lessen not only ADHD symptoms but also some symptoms of other mental health disorders, improve learning and behavior, and greatly improve family quality of life!

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

The day wouldn’t be so bad if he would just go to sleep at night! How many times have you heard this plea from parents of your patients with ADHD? Sleep is important for everyone, but getting enough is both more important and more difficult for children with ADHD. About three-quarters of children with ADHD have significant problems with sleep, most even before any medication treatment. And inadequate sleep can exacerbate or even cause ADHD symptoms!

Solving sleep problems for children with ADHD is not always simple. The kinds of sleep issues that are more common in children (and adults) with ADHD, compared with typical children, include behavioral bedtime resistance, circadian rhythm sleep disorder (CRSD), insomnia, morning sleepiness, night waking, periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), restless leg syndrome (RLS), and sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Such a broad differential means a careful history and sometimes even lab studies may be needed.

Both initial and follow-up visits for ADHD should include a sleep history or, ideally, a tool such as BEARS sleep screening tool or Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire and a 2-week sleep diary (http://www.sleepfoundation.org/). These are good ways to collect signs of allergies or apnea (for SDB), limb movements or limb pain (for RLS or PLMD), mouth breathing, night waking, and snoring.

You also need to ask about alcohol, drugs, caffeine, and nicotine; asthma; comorbid conditions such as mental health disorders or their treatments; and enuresis (alone or part of nocturnal seizures).

Do I need to remind you to find out about electronics activating the child before bedtime – hidden under the covers, or signaling messages from friends in the middle of the night – and to encourage limits on these? Some sleep disorders warrant polysomnography in a sleep lab or from MyZeo.com (for PLMD and some SDB) or ferritin less than 50 mg/L (for RLS) for diagnosis and to guide treatment. Nasal steroids, antihistamines, or montelukast may help SDB when there are enlarged tonsils or adenoids, but adenotonsillectomy is usually curative.

The first line and most effective treatment for sleep problems in children with or without ADHD is improving sleep hygiene. The key component is establishing habits for the entire sleep cycle: a steady pattern of reduced stimulation in the hour before bedtime (sans electronics); a friendly rather than irritated bedtime routine; and the same bedtime and wake up time, ideally 7 days per week. Bedtime stories read to the child can soothe at any age, not just toddlers! Of course, both children and families want fun and special occasions. For most, varying bedtime by up to 1 hour won’t mess up their biological clock, but for some even this should be avoided. Sleeping alone in a cool, dark, quiet room, nightly in the same bed (not used for other activities), is considered the ideal. Earplugs, white noise generators, and eye masks may be helpful. If sleeping with siblings is a necessity, bedtimes can be staggered to put the child to bed earlier or after others are asleep.

Struggles postponing bedtime may be part of a pattern of oppositionality common in ADHD, but the child may not be tired due to being off schedule (from CRSD), napping on the bus or after school, sleeping in mornings, or unrealistic parent expectations for sleep duration. Parents may want their hyperactive children to give them a break and go to bed at 8 p.m., but children aged 6-10 years need only 10-11 hours and those aged 10-17 years need 8.5-9.25 hours of sleep.

Not tired may instead be “wired” from lingering stimulant effects or even lack of such medication leaving the child overactive or rebounding from earlier medications. Lower afternoon doses or shorter-acting medication may solve lasting medication issues, but sometimes an additional low dose of stimulants actually will help a child with ADHD settle at bedtime. All stimulant medications can prolong sleep onset, often by 30 minutes, but this varies by individual and tends to resolve on its own a few weeks after a new or changed medicine. Switching medication category may allow a child to fall asleep faster. Atomoxetine and alpha agonists are less likely to delay sleep than methylphenidate (MPH).

What if sleep hygiene, behavioral methods, and adjusting ADHD medications is not enough? If sleep issues are causing significant problems, medication for sleep is worth a try. Controlled-release melatonin 1-2 hours before bedtime has data for effectiveness. There is no defined dose, so the lowest effective dose should be used, but 3-6 mg may be needed. Because many families with a child with ADHD are not organized enough to give medicine on this schedule, sublingual melatonin that acts in 15-20 minutes is a good alternative or even first choice. Clonidine 0.05-0.2 mg 1 hour before bedtime speeds sleep onset, lasts 3 hours, and does not carry over to sedation the next day. Stronger psychopharmaceuticals can assist sleep onset, including low dose mirtazapine or trazodone, but have the side effect of daytime sleepiness.

Management of waking in the middle of the night can be more difficult to treat as sleep drive has been dissipated. First, consider whether trips out of bed reflect a sleep association that has not been extinguished. Daytime atomoxetine or, better yet, MPH may improve night waking, and sometimes even a low-dose evening, long-acting medication, such as osmotic release oral system (OROS) extended release methylphenidate HCL (OROS MPH), helps. Short-acting clonidine or melatonin in the middle of the night or bedtime mirtazapine or trazodone also may be worth a try.

When dealing with sleep, keep in mind that 50% or more of children with ADHD have a coexisting mental health disorder. Anxiety, separation anxiety, depression, and dysthymia all often affect sleep onset, night waking, and sometimes early morning waking. The child or teen may need extra reassurance or company at bedtime (siblings or pets may suffice). Reading positive stories or playing soft music may be better at setting a positive mood and sense of safety for sleep, certainly more so than social media, which should be avoided.

Keep in mind that substance use is more common in ADHD as well as with those other mental health conditions and can interfere with restful sleep and make RLS worse. Bipolar disorder can be mistaken for ADHD as it often presents with hyperactivity but also can be comorbid. Sleep problems are increased sixfold when both are present. Prolonged periods awake at night and diminished need for sleep are signs that help differentiate bipolar from ADHD. Medication management for the bipolar disorder with atypicals can reduce sleep latency and reduce REM sleep, but also causes morning fatigue. Medications to treat other mental health problems can help sleep onset (for example, anticonvulsants, atypicals), or prolong it (SSRIs), change REM states (atypicals), and even exacerbate RLS (SSRIs). You can make changes or work with the child’s mental health specialist if medications are causing significant sleep problems.

When we help improve sleep for children with ADHD, it can lessen not only ADHD symptoms but also some symptoms of other mental health disorders, improve learning and behavior, and greatly improve family quality of life!

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

The day wouldn’t be so bad if he would just go to sleep at night! How many times have you heard this plea from parents of your patients with ADHD? Sleep is important for everyone, but getting enough is both more important and more difficult for children with ADHD. About three-quarters of children with ADHD have significant problems with sleep, most even before any medication treatment. And inadequate sleep can exacerbate or even cause ADHD symptoms!

Solving sleep problems for children with ADHD is not always simple. The kinds of sleep issues that are more common in children (and adults) with ADHD, compared with typical children, include behavioral bedtime resistance, circadian rhythm sleep disorder (CRSD), insomnia, morning sleepiness, night waking, periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), restless leg syndrome (RLS), and sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Such a broad differential means a careful history and sometimes even lab studies may be needed.

Both initial and follow-up visits for ADHD should include a sleep history or, ideally, a tool such as BEARS sleep screening tool or Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire and a 2-week sleep diary (http://www.sleepfoundation.org/). These are good ways to collect signs of allergies or apnea (for SDB), limb movements or limb pain (for RLS or PLMD), mouth breathing, night waking, and snoring.

You also need to ask about alcohol, drugs, caffeine, and nicotine; asthma; comorbid conditions such as mental health disorders or their treatments; and enuresis (alone or part of nocturnal seizures).

Do I need to remind you to find out about electronics activating the child before bedtime – hidden under the covers, or signaling messages from friends in the middle of the night – and to encourage limits on these? Some sleep disorders warrant polysomnography in a sleep lab or from MyZeo.com (for PLMD and some SDB) or ferritin less than 50 mg/L (for RLS) for diagnosis and to guide treatment. Nasal steroids, antihistamines, or montelukast may help SDB when there are enlarged tonsils or adenoids, but adenotonsillectomy is usually curative.

The first line and most effective treatment for sleep problems in children with or without ADHD is improving sleep hygiene. The key component is establishing habits for the entire sleep cycle: a steady pattern of reduced stimulation in the hour before bedtime (sans electronics); a friendly rather than irritated bedtime routine; and the same bedtime and wake up time, ideally 7 days per week. Bedtime stories read to the child can soothe at any age, not just toddlers! Of course, both children and families want fun and special occasions. For most, varying bedtime by up to 1 hour won’t mess up their biological clock, but for some even this should be avoided. Sleeping alone in a cool, dark, quiet room, nightly in the same bed (not used for other activities), is considered the ideal. Earplugs, white noise generators, and eye masks may be helpful. If sleeping with siblings is a necessity, bedtimes can be staggered to put the child to bed earlier or after others are asleep.

Struggles postponing bedtime may be part of a pattern of oppositionality common in ADHD, but the child may not be tired due to being off schedule (from CRSD), napping on the bus or after school, sleeping in mornings, or unrealistic parent expectations for sleep duration. Parents may want their hyperactive children to give them a break and go to bed at 8 p.m., but children aged 6-10 years need only 10-11 hours and those aged 10-17 years need 8.5-9.25 hours of sleep.

Not tired may instead be “wired” from lingering stimulant effects or even lack of such medication leaving the child overactive or rebounding from earlier medications. Lower afternoon doses or shorter-acting medication may solve lasting medication issues, but sometimes an additional low dose of stimulants actually will help a child with ADHD settle at bedtime. All stimulant medications can prolong sleep onset, often by 30 minutes, but this varies by individual and tends to resolve on its own a few weeks after a new or changed medicine. Switching medication category may allow a child to fall asleep faster. Atomoxetine and alpha agonists are less likely to delay sleep than methylphenidate (MPH).

What if sleep hygiene, behavioral methods, and adjusting ADHD medications is not enough? If sleep issues are causing significant problems, medication for sleep is worth a try. Controlled-release melatonin 1-2 hours before bedtime has data for effectiveness. There is no defined dose, so the lowest effective dose should be used, but 3-6 mg may be needed. Because many families with a child with ADHD are not organized enough to give medicine on this schedule, sublingual melatonin that acts in 15-20 minutes is a good alternative or even first choice. Clonidine 0.05-0.2 mg 1 hour before bedtime speeds sleep onset, lasts 3 hours, and does not carry over to sedation the next day. Stronger psychopharmaceuticals can assist sleep onset, including low dose mirtazapine or trazodone, but have the side effect of daytime sleepiness.

Management of waking in the middle of the night can be more difficult to treat as sleep drive has been dissipated. First, consider whether trips out of bed reflect a sleep association that has not been extinguished. Daytime atomoxetine or, better yet, MPH may improve night waking, and sometimes even a low-dose evening, long-acting medication, such as osmotic release oral system (OROS) extended release methylphenidate HCL (OROS MPH), helps. Short-acting clonidine or melatonin in the middle of the night or bedtime mirtazapine or trazodone also may be worth a try.

When dealing with sleep, keep in mind that 50% or more of children with ADHD have a coexisting mental health disorder. Anxiety, separation anxiety, depression, and dysthymia all often affect sleep onset, night waking, and sometimes early morning waking. The child or teen may need extra reassurance or company at bedtime (siblings or pets may suffice). Reading positive stories or playing soft music may be better at setting a positive mood and sense of safety for sleep, certainly more so than social media, which should be avoided.

Keep in mind that substance use is more common in ADHD as well as with those other mental health conditions and can interfere with restful sleep and make RLS worse. Bipolar disorder can be mistaken for ADHD as it often presents with hyperactivity but also can be comorbid. Sleep problems are increased sixfold when both are present. Prolonged periods awake at night and diminished need for sleep are signs that help differentiate bipolar from ADHD. Medication management for the bipolar disorder with atypicals can reduce sleep latency and reduce REM sleep, but also causes morning fatigue. Medications to treat other mental health problems can help sleep onset (for example, anticonvulsants, atypicals), or prolong it (SSRIs), change REM states (atypicals), and even exacerbate RLS (SSRIs). You can make changes or work with the child’s mental health specialist if medications are causing significant sleep problems.

When we help improve sleep for children with ADHD, it can lessen not only ADHD symptoms but also some symptoms of other mental health disorders, improve learning and behavior, and greatly improve family quality of life!

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Managing psychosis in youth

Strong feelings – such as intense anxiety, irritability, or depressed mood – may affect every child for brief periods of time during their development. Parents and pediatricians are wise to not treat them as psychiatric disorders unless they persist for weeks, impair functioning, or are dramatically severe. Psychosis – marked by hallucinations, perceptual distortions, or profoundly disorganized thinking and behavior – typically looks dramatically severe. Even when psychotic symptoms are mild or brief, they can cause very serious distress for parents and clinicians. The worry is that they may represent a “first break,” a psychotic episode that requires much work for recovery, or the beginning of a lifelong struggle with schizophrenia or other chronic psychotic illness.

While it is important to recognize schizophrenia early – because early interventions are thought to improve the course of the disease – schizophrenia in childhood is rare. It is not commonly recognized that psychotic or psychoticlike symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia. While it is important to begin a thoughtful evaluation when a child or teenager presents with psychosis, it also is important to know that the majority of young people who experience psychotic symptoms do not have schizophrenia or other psychotic illness.

Psychosis describes symptoms in which there has been some “break with reality,” often in the form of hallucinations (seeing or hearing things which are not objectively present) or of distorted perceptions (such as paranoia or grandiosity). “Subsyndromal psychotic symptoms” occur when a person experiences these perceptual disturbances but has doubt about whether or not they are real. In frank psychosis, patients have a “fixed and firm” belief in the truth or accuracy of their perceptions, no matter the evidence against them. The voices they hear or hallucinations they see are “real” and there is a wholehearted belief that what the voice says or what they are seeing is as true as what you or I see and hear.

Schizophrenia is a diagnosis that requires the presence of both these “positive” psychotic symptoms and “negative” symptoms of flat affect; loss of motivation, social, or motor abilities; and cognitive impairment. These symptoms typically emerge in late adolescence (median age, 18 years) in males and early adulthood (median age, 25 years) in females, with another (smaller) peak in incidence in middle age. Importantly, the negative symptoms often emerge first so there often is a history of subtle cognitive decline and social withdrawal, one of the most common patterns in children, before psychosis emerges. Schizophrenia is quite rare, with a prevalence of slightly under 1% of the global population, an annual incidence of approximately 15 people per 100,000, and 1 in 40,000 in children under 13 years old, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Psychotic symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia, affecting approximately 5% of the adult population at any point in time. They are even more common in children and adolescents. A meta-analysis of population-based studies of psychotic symptoms in youth demonstrated a median prevalence of 17% in children aged 9-12 years and 7.5% in adolescents aged 13-18 years.1 Of course, as with all statistics, much depends on the definitions used to identify this high prevalence rate.

Children and adolescents who report psychotic symptoms are at increased risk for developing schizophrenia, compared with the general population, but most youth with psychotic symptoms will not go on to develop schizophrenia. They are more likely to indicate other, nonpsychotic psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety or mood disorders, including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and PTSD. In younger children, these symptoms may prove to be benign, but in adolescents they usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness. In one study, 57% of children aged 11-13 years with psychotic symptoms were found to have a nonpsychotic psychiatric illness, but the rate jumped to 80% for those aged 13-15 years with psychotic symptoms.2 So while psychosis in teenagers only rarely indicates schizophrenia, these symptoms usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness, and a psychiatric evaluation should be initiated.

If a child in your practice presents with psychotic symptoms, it is appropriate to assess their safety and then start a medical work-up. Find out from your patient or their parents if their behavior has been affected by their perceptual disturbances. Are they frightened and avoiding school? Are they withdrawing from social relationships? Is their sleep disrupted? Have they been more impulsive or unpredictable? If their behavior has been affected, you should refer to a child psychiatrist to perform a full diagnostic evaluation and help with management of these symptoms.

Your medical work-up should include a drug screen, blood count, metabolic panel, and thyroid function test. Medications, particularly stimulants, steroids, and anticholinergics can cause psychotic symptoms in high doses or vulnerable patients (such as those with a developmental disorder or traumatic brain injury). If the physical or neurologic exam are suggestive, further investigation of the many potential medical sources of psychotic symptoms in youth can be pursued to rule out autoimmune illnesses, endocrine disorders, metabolic illnesses, heavy metal poisoning, neurologic diseases, infectious diseases, and nutritional deficits. It is worth noting that childhood sleep disorders also can present with psychosis. Persistent psychotic symptoms in children are very hard to evaluate and may be the harbinger of a serious psychiatric disorder, so even if the medical work-up is negative and the persistent symptoms are mild and not causing a safety concern, a referral to a child psychiatrist for a full mental health evaluation is appropriate.

Psychotic symptoms in an adolescent sometimes are easier to assess, more worrisome for serious mental illness, and are a high-risk category for self-destructive behavior and substance use. Before you begin a medical work-up, you always should assess for safety, including suicide risk, if your adolescent patient presents with psychotic symptoms. Screening for symptoms of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders also can help reveal the nature of their presenting problem. If your adolescent patient is using drugs, that does not rule out the possibility of an underlying mood, anxiety, or thought disorder. While intoxication with many drugs may precipitate psychotic symptoms (including stimulants, hallucinogens, and marijuana), others may precipitate psychosis in withdrawal states (alcohol, benzodiazepines, and other CNS depressants). It also is important to note that adolescents with emerging schizophrenia have very high rates of comorbid substance abuse (as high as 60%), so their drug use may not be the cause of their psychotic symptoms. There also is emerging evidence that use of certain drugs during sensitive developmental periods can significantly increase the likelihood of developing schizophrenia in vulnerable populations, such as with regular marijuana use in adolescents who have a family history of schizophrenia.

For those rare pediatric patients who present with both negative and positive symptoms of emerging schizophrenia, early diagnosis and treatment has shown promise in improving the course of the disease. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis has shown promise in lowering the rates of conversion to schizophrenia in select patient populations. This therapy teaches strategies for improving reality testing, cognitive flexibility, and social skills. The social skills appear to be especially important for improving adaptive function, even in those patients who progress to schizophrenia. Family therapies, focused on improving family cohesion, communication, and adaptive functioning, appear to improve family well-being and the course of the patient’s illness (such as fewer and less severe psychotic episodes and improved mood and adaptive function). Early use of antipsychotic medications also appears to improve the course of the illness.

While schizophrenia is not curable, early detection (perhaps by a pediatrician), referral, and treatment can be powerfully protective for patients and their families.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Psychol Med. 2012 Sep;42(9):1857-63.

2. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;201(1):26-32.

Strong feelings – such as intense anxiety, irritability, or depressed mood – may affect every child for brief periods of time during their development. Parents and pediatricians are wise to not treat them as psychiatric disorders unless they persist for weeks, impair functioning, or are dramatically severe. Psychosis – marked by hallucinations, perceptual distortions, or profoundly disorganized thinking and behavior – typically looks dramatically severe. Even when psychotic symptoms are mild or brief, they can cause very serious distress for parents and clinicians. The worry is that they may represent a “first break,” a psychotic episode that requires much work for recovery, or the beginning of a lifelong struggle with schizophrenia or other chronic psychotic illness.

While it is important to recognize schizophrenia early – because early interventions are thought to improve the course of the disease – schizophrenia in childhood is rare. It is not commonly recognized that psychotic or psychoticlike symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia. While it is important to begin a thoughtful evaluation when a child or teenager presents with psychosis, it also is important to know that the majority of young people who experience psychotic symptoms do not have schizophrenia or other psychotic illness.

Psychosis describes symptoms in which there has been some “break with reality,” often in the form of hallucinations (seeing or hearing things which are not objectively present) or of distorted perceptions (such as paranoia or grandiosity). “Subsyndromal psychotic symptoms” occur when a person experiences these perceptual disturbances but has doubt about whether or not they are real. In frank psychosis, patients have a “fixed and firm” belief in the truth or accuracy of their perceptions, no matter the evidence against them. The voices they hear or hallucinations they see are “real” and there is a wholehearted belief that what the voice says or what they are seeing is as true as what you or I see and hear.

Schizophrenia is a diagnosis that requires the presence of both these “positive” psychotic symptoms and “negative” symptoms of flat affect; loss of motivation, social, or motor abilities; and cognitive impairment. These symptoms typically emerge in late adolescence (median age, 18 years) in males and early adulthood (median age, 25 years) in females, with another (smaller) peak in incidence in middle age. Importantly, the negative symptoms often emerge first so there often is a history of subtle cognitive decline and social withdrawal, one of the most common patterns in children, before psychosis emerges. Schizophrenia is quite rare, with a prevalence of slightly under 1% of the global population, an annual incidence of approximately 15 people per 100,000, and 1 in 40,000 in children under 13 years old, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Psychotic symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia, affecting approximately 5% of the adult population at any point in time. They are even more common in children and adolescents. A meta-analysis of population-based studies of psychotic symptoms in youth demonstrated a median prevalence of 17% in children aged 9-12 years and 7.5% in adolescents aged 13-18 years.1 Of course, as with all statistics, much depends on the definitions used to identify this high prevalence rate.

Children and adolescents who report psychotic symptoms are at increased risk for developing schizophrenia, compared with the general population, but most youth with psychotic symptoms will not go on to develop schizophrenia. They are more likely to indicate other, nonpsychotic psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety or mood disorders, including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and PTSD. In younger children, these symptoms may prove to be benign, but in adolescents they usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness. In one study, 57% of children aged 11-13 years with psychotic symptoms were found to have a nonpsychotic psychiatric illness, but the rate jumped to 80% for those aged 13-15 years with psychotic symptoms.2 So while psychosis in teenagers only rarely indicates schizophrenia, these symptoms usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness, and a psychiatric evaluation should be initiated.

If a child in your practice presents with psychotic symptoms, it is appropriate to assess their safety and then start a medical work-up. Find out from your patient or their parents if their behavior has been affected by their perceptual disturbances. Are they frightened and avoiding school? Are they withdrawing from social relationships? Is their sleep disrupted? Have they been more impulsive or unpredictable? If their behavior has been affected, you should refer to a child psychiatrist to perform a full diagnostic evaluation and help with management of these symptoms.

Your medical work-up should include a drug screen, blood count, metabolic panel, and thyroid function test. Medications, particularly stimulants, steroids, and anticholinergics can cause psychotic symptoms in high doses or vulnerable patients (such as those with a developmental disorder or traumatic brain injury). If the physical or neurologic exam are suggestive, further investigation of the many potential medical sources of psychotic symptoms in youth can be pursued to rule out autoimmune illnesses, endocrine disorders, metabolic illnesses, heavy metal poisoning, neurologic diseases, infectious diseases, and nutritional deficits. It is worth noting that childhood sleep disorders also can present with psychosis. Persistent psychotic symptoms in children are very hard to evaluate and may be the harbinger of a serious psychiatric disorder, so even if the medical work-up is negative and the persistent symptoms are mild and not causing a safety concern, a referral to a child psychiatrist for a full mental health evaluation is appropriate.

Psychotic symptoms in an adolescent sometimes are easier to assess, more worrisome for serious mental illness, and are a high-risk category for self-destructive behavior and substance use. Before you begin a medical work-up, you always should assess for safety, including suicide risk, if your adolescent patient presents with psychotic symptoms. Screening for symptoms of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders also can help reveal the nature of their presenting problem. If your adolescent patient is using drugs, that does not rule out the possibility of an underlying mood, anxiety, or thought disorder. While intoxication with many drugs may precipitate psychotic symptoms (including stimulants, hallucinogens, and marijuana), others may precipitate psychosis in withdrawal states (alcohol, benzodiazepines, and other CNS depressants). It also is important to note that adolescents with emerging schizophrenia have very high rates of comorbid substance abuse (as high as 60%), so their drug use may not be the cause of their psychotic symptoms. There also is emerging evidence that use of certain drugs during sensitive developmental periods can significantly increase the likelihood of developing schizophrenia in vulnerable populations, such as with regular marijuana use in adolescents who have a family history of schizophrenia.

For those rare pediatric patients who present with both negative and positive symptoms of emerging schizophrenia, early diagnosis and treatment has shown promise in improving the course of the disease. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis has shown promise in lowering the rates of conversion to schizophrenia in select patient populations. This therapy teaches strategies for improving reality testing, cognitive flexibility, and social skills. The social skills appear to be especially important for improving adaptive function, even in those patients who progress to schizophrenia. Family therapies, focused on improving family cohesion, communication, and adaptive functioning, appear to improve family well-being and the course of the patient’s illness (such as fewer and less severe psychotic episodes and improved mood and adaptive function). Early use of antipsychotic medications also appears to improve the course of the illness.

While schizophrenia is not curable, early detection (perhaps by a pediatrician), referral, and treatment can be powerfully protective for patients and their families.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Psychol Med. 2012 Sep;42(9):1857-63.

2. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;201(1):26-32.

Strong feelings – such as intense anxiety, irritability, or depressed mood – may affect every child for brief periods of time during their development. Parents and pediatricians are wise to not treat them as psychiatric disorders unless they persist for weeks, impair functioning, or are dramatically severe. Psychosis – marked by hallucinations, perceptual distortions, or profoundly disorganized thinking and behavior – typically looks dramatically severe. Even when psychotic symptoms are mild or brief, they can cause very serious distress for parents and clinicians. The worry is that they may represent a “first break,” a psychotic episode that requires much work for recovery, or the beginning of a lifelong struggle with schizophrenia or other chronic psychotic illness.

While it is important to recognize schizophrenia early – because early interventions are thought to improve the course of the disease – schizophrenia in childhood is rare. It is not commonly recognized that psychotic or psychoticlike symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia. While it is important to begin a thoughtful evaluation when a child or teenager presents with psychosis, it also is important to know that the majority of young people who experience psychotic symptoms do not have schizophrenia or other psychotic illness.

Psychosis describes symptoms in which there has been some “break with reality,” often in the form of hallucinations (seeing or hearing things which are not objectively present) or of distorted perceptions (such as paranoia or grandiosity). “Subsyndromal psychotic symptoms” occur when a person experiences these perceptual disturbances but has doubt about whether or not they are real. In frank psychosis, patients have a “fixed and firm” belief in the truth or accuracy of their perceptions, no matter the evidence against them. The voices they hear or hallucinations they see are “real” and there is a wholehearted belief that what the voice says or what they are seeing is as true as what you or I see and hear.

Schizophrenia is a diagnosis that requires the presence of both these “positive” psychotic symptoms and “negative” symptoms of flat affect; loss of motivation, social, or motor abilities; and cognitive impairment. These symptoms typically emerge in late adolescence (median age, 18 years) in males and early adulthood (median age, 25 years) in females, with another (smaller) peak in incidence in middle age. Importantly, the negative symptoms often emerge first so there often is a history of subtle cognitive decline and social withdrawal, one of the most common patterns in children, before psychosis emerges. Schizophrenia is quite rare, with a prevalence of slightly under 1% of the global population, an annual incidence of approximately 15 people per 100,000, and 1 in 40,000 in children under 13 years old, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Psychotic symptoms are much more common than schizophrenia, affecting approximately 5% of the adult population at any point in time. They are even more common in children and adolescents. A meta-analysis of population-based studies of psychotic symptoms in youth demonstrated a median prevalence of 17% in children aged 9-12 years and 7.5% in adolescents aged 13-18 years.1 Of course, as with all statistics, much depends on the definitions used to identify this high prevalence rate.

Children and adolescents who report psychotic symptoms are at increased risk for developing schizophrenia, compared with the general population, but most youth with psychotic symptoms will not go on to develop schizophrenia. They are more likely to indicate other, nonpsychotic psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety or mood disorders, including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and PTSD. In younger children, these symptoms may prove to be benign, but in adolescents they usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness. In one study, 57% of children aged 11-13 years with psychotic symptoms were found to have a nonpsychotic psychiatric illness, but the rate jumped to 80% for those aged 13-15 years with psychotic symptoms.2 So while psychosis in teenagers only rarely indicates schizophrenia, these symptoms usually indicate the presence of a psychiatric illness, and a psychiatric evaluation should be initiated.

If a child in your practice presents with psychotic symptoms, it is appropriate to assess their safety and then start a medical work-up. Find out from your patient or their parents if their behavior has been affected by their perceptual disturbances. Are they frightened and avoiding school? Are they withdrawing from social relationships? Is their sleep disrupted? Have they been more impulsive or unpredictable? If their behavior has been affected, you should refer to a child psychiatrist to perform a full diagnostic evaluation and help with management of these symptoms.

Your medical work-up should include a drug screen, blood count, metabolic panel, and thyroid function test. Medications, particularly stimulants, steroids, and anticholinergics can cause psychotic symptoms in high doses or vulnerable patients (such as those with a developmental disorder or traumatic brain injury). If the physical or neurologic exam are suggestive, further investigation of the many potential medical sources of psychotic symptoms in youth can be pursued to rule out autoimmune illnesses, endocrine disorders, metabolic illnesses, heavy metal poisoning, neurologic diseases, infectious diseases, and nutritional deficits. It is worth noting that childhood sleep disorders also can present with psychosis. Persistent psychotic symptoms in children are very hard to evaluate and may be the harbinger of a serious psychiatric disorder, so even if the medical work-up is negative and the persistent symptoms are mild and not causing a safety concern, a referral to a child psychiatrist for a full mental health evaluation is appropriate.

Psychotic symptoms in an adolescent sometimes are easier to assess, more worrisome for serious mental illness, and are a high-risk category for self-destructive behavior and substance use. Before you begin a medical work-up, you always should assess for safety, including suicide risk, if your adolescent patient presents with psychotic symptoms. Screening for symptoms of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders also can help reveal the nature of their presenting problem. If your adolescent patient is using drugs, that does not rule out the possibility of an underlying mood, anxiety, or thought disorder. While intoxication with many drugs may precipitate psychotic symptoms (including stimulants, hallucinogens, and marijuana), others may precipitate psychosis in withdrawal states (alcohol, benzodiazepines, and other CNS depressants). It also is important to note that adolescents with emerging schizophrenia have very high rates of comorbid substance abuse (as high as 60%), so their drug use may not be the cause of their psychotic symptoms. There also is emerging evidence that use of certain drugs during sensitive developmental periods can significantly increase the likelihood of developing schizophrenia in vulnerable populations, such as with regular marijuana use in adolescents who have a family history of schizophrenia.

For those rare pediatric patients who present with both negative and positive symptoms of emerging schizophrenia, early diagnosis and treatment has shown promise in improving the course of the disease. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis has shown promise in lowering the rates of conversion to schizophrenia in select patient populations. This therapy teaches strategies for improving reality testing, cognitive flexibility, and social skills. The social skills appear to be especially important for improving adaptive function, even in those patients who progress to schizophrenia. Family therapies, focused on improving family cohesion, communication, and adaptive functioning, appear to improve family well-being and the course of the patient’s illness (such as fewer and less severe psychotic episodes and improved mood and adaptive function). Early use of antipsychotic medications also appears to improve the course of the illness.

While schizophrenia is not curable, early detection (perhaps by a pediatrician), referral, and treatment can be powerfully protective for patients and their families.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Psychol Med. 2012 Sep;42(9):1857-63.

2. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;201(1):26-32.

It’s all in the timing

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

Dr. Barbara J. Howard will receive the 2019 C. Anderson Aldrich Award

The award is given by the AAP Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics to “recognize physicians who have made outstanding contributions to the field of child development,” according to the AAP. Previous recipients of the award include pediatricians such as Benjamin M. Spock, MD, and T. Berry Brazelton, MD, as well as psychoanalyst Anna Freud and child psychologist Erik H. Erickson.

Dr. Howard is a developmental-behavioral pediatrician who is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where she codirected a fellowship program to train developmental and behavioral pediatricians. She is a creator of CHADIS, an innovative online system that provides previsit questionnaires that allows physicians “to collect patient-generated data that can be used to support clinical and shared decisions, track data, and create quality improvement reports,” according to the CHADIS website. She has given free monthly case conferences through a federal grant for 30 years, initially in person and more recently through a national webcast. Over the last 2 decades, Dr. Howard has written about practical approaches to developmental and behavioral problems children experience for this newspaper in her Behavioral Consult column.

Michael S. Jellinek, MD, professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview, “Barbara’s dedication to the emotional health of children has made an enormous difference. In addition to her clinical care and writing, her development of CHADIS has helped pediatricians recognize and treat thousands upon thousands of children. She is most deserving of this high honor.”

The award is given by the AAP Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics to “recognize physicians who have made outstanding contributions to the field of child development,” according to the AAP. Previous recipients of the award include pediatricians such as Benjamin M. Spock, MD, and T. Berry Brazelton, MD, as well as psychoanalyst Anna Freud and child psychologist Erik H. Erickson.

Dr. Howard is a developmental-behavioral pediatrician who is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where she codirected a fellowship program to train developmental and behavioral pediatricians. She is a creator of CHADIS, an innovative online system that provides previsit questionnaires that allows physicians “to collect patient-generated data that can be used to support clinical and shared decisions, track data, and create quality improvement reports,” according to the CHADIS website. She has given free monthly case conferences through a federal grant for 30 years, initially in person and more recently through a national webcast. Over the last 2 decades, Dr. Howard has written about practical approaches to developmental and behavioral problems children experience for this newspaper in her Behavioral Consult column.

Michael S. Jellinek, MD, professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview, “Barbara’s dedication to the emotional health of children has made an enormous difference. In addition to her clinical care and writing, her development of CHADIS has helped pediatricians recognize and treat thousands upon thousands of children. She is most deserving of this high honor.”

The award is given by the AAP Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics to “recognize physicians who have made outstanding contributions to the field of child development,” according to the AAP. Previous recipients of the award include pediatricians such as Benjamin M. Spock, MD, and T. Berry Brazelton, MD, as well as psychoanalyst Anna Freud and child psychologist Erik H. Erickson.

Dr. Howard is a developmental-behavioral pediatrician who is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where she codirected a fellowship program to train developmental and behavioral pediatricians. She is a creator of CHADIS, an innovative online system that provides previsit questionnaires that allows physicians “to collect patient-generated data that can be used to support clinical and shared decisions, track data, and create quality improvement reports,” according to the CHADIS website. She has given free monthly case conferences through a federal grant for 30 years, initially in person and more recently through a national webcast. Over the last 2 decades, Dr. Howard has written about practical approaches to developmental and behavioral problems children experience for this newspaper in her Behavioral Consult column.

Michael S. Jellinek, MD, professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview, “Barbara’s dedication to the emotional health of children has made an enormous difference. In addition to her clinical care and writing, her development of CHADIS has helped pediatricians recognize and treat thousands upon thousands of children. She is most deserving of this high honor.”

Encourage participation in team sports

Participation in sports, competitive team sports in particular, is very good for the physical well-being and emotional development of children and adolescents. Specifically, there is growing evidence that sports promote healthy development socially and emotionally, protecting against drug use, poor body image, and against psychiatric illness in youth.

Sustaining academic productivity and team sports is demanding. By the middle of autumn, the amount of homework can begin to wear on teenagers, and the burden of getting them to practices and games can wear on parents. It can be very tempting for youth and their parents to drop team sports in high school, and turn their time and effort more completely to the serious work of school. But advocating for your patients and their parents to protect the time for team sports participation will pay dividends in the health and well-being of your patients and may even support rather than detract from academic performance.

The benefits of regular exercise for physical health are well established. Most teenagers do not get the recommended 60 minutes daily of moderate to vigorous physical activity. Participating in a team sport enforces this level of activity, in ways that parents typically don’t have to enforce. This level of physical activity typically promotes healthy eating and a healthy weight. Daily exercise promotes adequate, restful sleep, one of the most critical (and usually compromised) components of adolescent health. These exercise habits are easier to maintain into adulthood – when they protect against cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases – if they have been established early.

Beyond physical health, participation in team sports has been shown to promote good mental health and protect against psychiatric illnesses. They generally are less likely to use drugs and more likely to have a healthy body image than are their nonathlete peers. It is worth noting that the mental health benefits of team sports are even more robust than the benefits of solitary exercise in teenagers,1 possibly because of the social connections to peers and adults that grow out of them.

In the Monitoring the Future surveys (biannual national surveys of high school student health and behaviors funded by the National Institutes of Health) from 2010 to 2015, teenagers who participated in team sports were more likely to describe higher self-esteem and lower levels of loneliness. It is important to note that it has been difficult to establish the causal direction of the association between team sports and mental health in youth. We need more prospective randomized controlled trials to assert that the benefit is not simply an artifact of healthier youth choosing to participate in sports, but actually an active consequence of that choice. For now, though, we can say with confidence that physical activity promotes good mental health in youth and may protect against mental illness.

While student athletes benefit from the opportunity to develop deep social connections – ones forged in the intense setting of competition, collaboration, and sustained teamwork – they also benefit from strong mentorship connections with adults, including coaches, trainers, and even the parents of teammates who participate in all of the efforts that go into team sports in youth. While it might seem that all of the mental and physical benefits must be offset by lower academic performance, it turns out that is not the case. It is well established that regular exercise promotes healthy cognitive function, including processing speed, working memory, and even creativity. According to data from the Monitoring the Future survey, adolescents who participated in team sports were more likely to have As and to plan on attending a 4-year college than were their nonathlete peers.

Beyond the physiologic and social benefits of exercise, team sports provide adolescents with a powerful opportunity to get comfortable with failure. Even the best athletes cannot win all the time, and sports are unique in building failure into the work. Practice is almost entirely about failure, gradually getting better at something that is difficult. While everyone aims to win, they also prepare to struggle and lose. Athletes must learn how to persevere through a match that they are losing, and then pick themselves up and prepare again for the next match. When young people get comfortable with facing and managing challenges, managing setbacks and failure, they are ready to face the larger challenges, setbacks, and failures of adult life.

Team sports enable young people to learn what they are actually capable of managing – they build resilience. This promotion of resilience is illustrated in recent research that demonstrated that team sports may be especially protective for young people who have experienced trauma (adverse childhood experiences, or “ACEs”). Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, followed teenagers with and without high ACE scores into their mid 20s. They found that those with high ACE scores who participated in team sports as adolescents were 24% less likely to have depression and 30% less likely to have anxiety diagnoses as adults, compared with their peers who did not participate in team sports.2