User login

Dementia, bizarre creatures, and a white knight to the rescue

CASE Strange creatures

Ms. L, age 78, is admitted to the inpatient unit for treatment of psychosis and behavioral changes. In the months before this admission, she had visited the emergency room several times for recurrent falls. CT scans of the head show no acute changes; brain and spinal MRI reveal evidence of chronic white matter disease and degenerative changes of the spine. Medical workup is unremarkable and includes evaluation for syncope and ambulation impairments related to degenerative disease of the hip joints.

Ms. L and her family are instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician and a neurologist for neuromuscular workup.

She next presents to her primary care physician, describing hallucinations of strangers walking around her house. Over a few weeks, hallucinations expand to include a fixed hallucination of creatures that she describes as having qualities of insects and plants, “piling up” around her. She describes tactile hallucinations of these creatures crawling on her skin, and she tracks their movements around her. She complains of vivid visual hallucinations of these creatures spinning webs across the room and she says she keeps the lights on at night. Ms. L becomes anxious and depressed, and her insomnia becomes worse.

She is referred for outpatient psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Ms. L’s family notes lapses of short-term memory, disorganization, and difficulty with tasks such as cooking because she has trouble following steps. These deficits come and go, with periods when she is functional and others during which she experiences considerable confusion. The family is uncertain when these signs and symptoms first appeared, but are clear that these deficits are having an impact on her day-to-day life. She can conduct activities of daily living, but with increasing difficulty—and only with help from her husband for tasks that require complex order and movement.

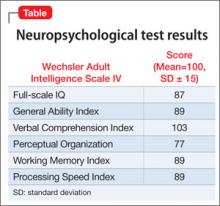

Over several months, Ms. L’s gait stability decreases and she begins to rely on a walker to keep from falling. On the Montreal Cognitive Assessment screening for cognitive dysfunction, she scores 19 out of 30 (normal range >25). This suggests cognitive impairment greater than expected for her age, compared with normal controls, and, when coupled with her functional impairment, raises the possibility of a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

a) donepezil

b) memantine

c) quetiapine

d) low-dose clozapine

The authors’ observations

Limited literature exists of placebo-controlled, large-scale studies on DLB treatment. Cholinesterase inhibitors have shown some symptomatic benefit, including for hallucinations.1-3 Memantine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blocker, shows mixed results.4 Many studies explore the use of neuroleptics for treating hallucinations in psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) but, in DLB, the literature primarily consists of case reports.2 Much of DLB treatment is inferred and intermixed with studies on PDD.5,6

Low-dose clozapine has become a standard treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease based on the findings of several trials.6 Despite its side-effect profile, clozapine has been shown to ameliorate hallucinations in PDD without exacerbating parkinsonian symptoms,7,8 and is the only medication with proven efficacy in PDD.2 The French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group demonstrated relief of psychotic symptoms of Parkinson’s disease with clozapine, 6.25 mg/d.9 The Clozapine Study Group found complete resolution of hallucinations in some patients within 1 day of initiating clozapine. Among patients in this study who did not see immediate benefit, most showed significant improvement of psychotic symptoms in 1 or 2 weeks.10

TREATMENT Few options

Ms. L’s psychiatrist and primary care physician start her on a series of medications. Donepezil is initiated for suspected dementia. We begin a trial of quetiapine to address the hallucinations, but the drug makes her movement symptoms worse. Risperidone also is tried but, again, the drugs make movement symptoms, particularly gait instability, tremor, and rigidity worse without alleviating the hallucinations. Neuroleptics seem to exacerbate confusion. Because of worsening depressive symptoms and our concern over possible pseudodementia, we try several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and mirtazapine. Antidepressants have little effect on her depressive symptoms and do not improve hallucinations or insomnia.

Ms. L’s signs and symptoms become worse over the next few months, with more severe hallucinations, agitation, insomnia, and gait instability. Her agitation over the hallucinations increases and she begins pouring bleach around herself in bed and spraying her house with toxic bug spray. Ms. L’s family brings her to the hospital after they observe her scratching the hallucinatory creatures off of her skin with a razor blade and trying to pry them out of her mouth with a piece of metal.

In the hospital, medical and neurologic workups rule out organic causes for her symptoms and signs. MRI is consistent with imaging from 6 months earlier. Focal neurologic signs are absent. Blood work is within normal limits, failing to reveal any pathology that would suggest a cause for her symptoms and signs, such as syphilis, vitamin deficiency, and Lyme disease.

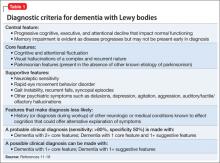

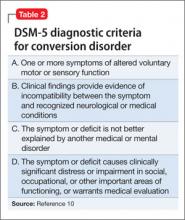

Ms. L’s symptoms were consistent with consensus guideline criteria for a clinical diagnosis of DLB (Table 1).11-18

She is started on low-dose quetiapine, which she tolerates poorly with worsening confusion, rigidity, tremor, and gait instability. Because other agents failed, Ms. L’s providers and family decide on a trial of clozapine.

Within 24 hours after the first dose of clozapine, 25 mg, sleep improves, the tactile component of hallucinations diminish, and she begins to spend increasing periods of time “observing the creatures” rather than fighting with them.

Over the next few days, Ms. L’s attitude towards the creatures changes. Now, as she sits observing them intently, the hallucinations evolve: rather than tormenting her and causing distress, the plant-creatures burst apart and a miniature knight on horseback charges out. The rest of the creatures then gather into a rank and file and the knight leads them to the nearest exit.

Clozapine is titrated to 50 mg/d, which she tolerates well without exacerbation of cognitive symptoms or movement disorder. The only notable adverse effect at the time of her discharge is sialorrhea.

with an antipsychotic?

a) start low and go slow

b) monitor her heart rate and blood pressure

c) readminister the Montreal Cognitive Assessment

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Ideally, in psychosis, antipsychotics eliminate positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. In DLB, the aim is to alleviate the agitation and suffering brought on by the psychotic symptoms without exacerbating other motor and cognitive symptoms. The hallucinations are obstinate, and it is a well-known quality of this disorder that patients are exceptionally susceptible to a range of antipsychotic side effects including cognitive impairment, fatigue, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and parkinsonism.19

Treatment in DLB requires trial and error, and medications with fewer associated risks should be administered first. Patients with DLB treated with neuroleptics have an increased risk of death compared with those who are not treated.19 Moreover, prescribing information for clozapine includes a black-box warning that the drug:

- is not approved for dementia-related psychosis and

- is associated with an increased risk of death in elderly patients with these conditions, similar to what is seen with other neuroleptics.20

Despite these well-known concerns, it remains difficult for clinicians not to try to treat the distress caused by these symptoms.

We chose clozapine for Ms. L because:

- other neuroleptics failed

- acetylcholinesterase inhibitors did not alleviate Ms. L’s psychosis and associated behavioral disturbance

- there is substantial evidence that the drug can be effective in Parkinson’s disease with psychosis.

There is controversy regarding use of clozapine in DLB. In one case series, clozapine trigger extreme neuroleptic reactions in some patients, similar to what occurs with other second-generation antipsychotics.21 Another case series provides examples of the drug’s efficacy in treating hallucinations and delusions with minimal adverse effects.22

It is important to emphasize that Ms. L’s hallucinations did not go away; rather, they changed to a more benign presentation that she could manage and, occasionally, found pleasant. Ultimately, her agitation—the primary target of treatment—improved markedly with the arrival of the knight in shining armor.

Treatment recommendations

If neuropsychiatric symptoms in DLB are the primary concern of the patient and family, we recommend the following:

- Begin treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor. The best evidence exists for rivastigmine and donepezil. These drugs have a low risk of side effects, which are primarily gastrointestinal effects with some reports of worsening extrapyramidal symptoms.23-25

- If the patient obtains minimal benefit or develops a significant adverse effect from cholinesterase inhibitors, consider memantine. Its efficacy is under examination and results are mixed; it can be used in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors.26-28

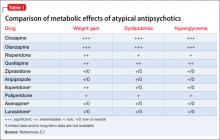

- If psychotic symptoms are upsetting and refractory to other therapies, consider antipsychotics. Avoid first-generation antipsychotics. The American Psychiatric Association recommends aripiprazole or quetiapine initially, although there is little evidence comparing neuroleptics in DLB.29 Because of its risks, reserve clozapine for refractory cases. An exception might be made for patients sensitive to extrapyramidal effects, in whom clozapine could be considered earlier.

There are no formal neuroleptic dosing guidelines beyond a general urging towards minimalism. Mosimann and McKeith30 recommend clozapine, 12.5 mg/d; olanzapine, 2.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.25 mg/d; or quetiapine, 12.5 mg/d. Such dosages might be effective while producing only minimal side effects.9,31

SSRIs and other antidepressants have not been shown to improve neuropsychiatric symptoms, and often are poorly tolerated.32

One study found efficacy with electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant patients.33

In addition to these treatments, nonpharmaceutical interventions should be employed from the earliest stages of diagnosis and treatment (Table 2). See the Figure for an algorithm for treating DLB. These include educational and behavioral interventions, social support, psychological interventions, and environmental therapies and modifications.

OUTCOME New friends

The creatures return from time to time, Ms. L reports, but are no longer upsetting because the white knight (a sort of mental deus ex machina) leads the once-terrifying things away. She describes the hallucination as a kind of zoological observation, refers to the creatures that once horrified her as “her friends,” and chuckles as she observes their natural history. This new, far more benign hallucination becomes a mainstay of her symptoms, and she is discharged to the care of her husband and family.

Soon after her discharge, her hallucinations resolved completely, but returned briefly when Ms. L resumed smoking cigarettes because smoking is known to lower clozapine serum levels.34

Bottom Line

Consider a low dosage of a neuroleptic when a patient suffers significant distress and behavioral disturbance related to psychotic symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and those problems are not relieved by other agents. Low-dose clozapine is an option for refractory psychotic symptoms or in patients with severe extrapyramidal sensitivity. Start low, and go slow.

Related Resources

- Bishnoi RJ, Grossberg GT, Manepalli J. Differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(11):22-27.

- McKeith I, Emre M. Management of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. In: Emre M, ed. Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2010:245-256.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Clozapine • Clozaril Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Donepezil • Aricept Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Memantine • Namenda Rivastigmine • Exelon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wesnes KA, McKeith IG, Ferrara R, et al. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised placebo-controlled international study using the Cognitive Drug Research computerized assessment system. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002; 13(3):183-192.

2. Weintraub D, Hurtig HI. Presentation and management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1491-1498.

3. McKeith IG, Wesnes KA, Perry E, et al. Hallucinations predict attentional improvements with rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(1):94-100.

4. Emre M, Tsolaki , Bonuccelli U, et al. Memantine for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):969-977.

5. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Clinical trials of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(5):492-501.

6. Drach LM. Drug treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia--common features and differences [in German]. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2011; 34(2):47-52.

7. Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Ziegenbein M, et al. Treating dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: Structured review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):165-171.

8. Marti MJ, Tolosa E, de la Cerda A. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2007;254(suppl 5):41-48.

9. French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group. Clozapine in drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9169):2041-2042.

10. Friedman JH, Factor SA. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(2):201-211.

11. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113-1124.

12. McKeith IG, Ballard CG, Perry RH et al. Prospective validation of consensus criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1050-1058.

13. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863-1872.

14. McKeith IG. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(suppl 3):417-423.

15. Geser F, Wenning GK, Poewe W, et al. How to diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies: state of the art. Mov Disord. 2005;20(suppl 12):S11-20.

16. Latoo J, Jan F. Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical review. British Journal of Medical Practioners. 2008;1(1):10-14.

17. McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(3):333-341.

18. Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, et al; Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee. SIC Task Force Appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18(5):467-486.

19. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305(6855):673-678.

20. Clozapine Monitoring Guidelines. 2008. http://www.clozapineregistry.com/resuming_treatment_after_interruption.pdf.ashx. Accessed October 31, 2013.

21. Burke WJ, Pfeiffer RF, McComb RD. Neuroleptic sensitivity to clozapine in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10(2):227-229.

22. Chacko RC, Hurley RA, Jankovic J. Clozapine use in diffuse Lewy body disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5(2):206-208.

23. McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031-2036

24. Mori E, Ikeda M, Kosaka K; Donepezil-DLB Study Investiagors. Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2012; 72(1):41-52.

25. Ukai K, Aleksic B, Ishihara R, et al. Efficacy of donepezil for the treatment of visual and multiple sensory hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies. Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and Therapeutics. 2011;2:56-58.

26. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Memantine in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):613-618.

27. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ. Melatonin for treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder in neurologic disorders: results in 14 patients. Sleep Med. 2003;4(4):281-284.

28. Mathys ML, McCarrell J, Sleeper RB, et al. Visual hallucinations treated with the reinitiation of memantine in a patient with Lewy body dementia. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(2):e10.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pdfaccess.ashx?ResourceID=243205&PDFSource=6. Accessed November 1, 2013.

30. Mosimann U, McKeith IG. Dementia with lewy bodies—diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:131-142.

31. Baskys A, Davis P Atypical antipsychotic quetiapine in the treatment of the psychosis associated with Lewy body dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:S63.

32. Culo S, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Treating neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized controlled-trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(4):306-364.

33. Takahashi S, Mizukami K, Yasuno F, et al. Depression associated with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and the effect of somatotherapy. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):56-61.

34. van der Weide J, Steijns LS, van Weelden MJ. The effect of smoking and cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 genetic polymorphism on clozapine clearance and dose requirement. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(3):169-172.

CASE Strange creatures

Ms. L, age 78, is admitted to the inpatient unit for treatment of psychosis and behavioral changes. In the months before this admission, she had visited the emergency room several times for recurrent falls. CT scans of the head show no acute changes; brain and spinal MRI reveal evidence of chronic white matter disease and degenerative changes of the spine. Medical workup is unremarkable and includes evaluation for syncope and ambulation impairments related to degenerative disease of the hip joints.

Ms. L and her family are instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician and a neurologist for neuromuscular workup.

She next presents to her primary care physician, describing hallucinations of strangers walking around her house. Over a few weeks, hallucinations expand to include a fixed hallucination of creatures that she describes as having qualities of insects and plants, “piling up” around her. She describes tactile hallucinations of these creatures crawling on her skin, and she tracks their movements around her. She complains of vivid visual hallucinations of these creatures spinning webs across the room and she says she keeps the lights on at night. Ms. L becomes anxious and depressed, and her insomnia becomes worse.

She is referred for outpatient psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Ms. L’s family notes lapses of short-term memory, disorganization, and difficulty with tasks such as cooking because she has trouble following steps. These deficits come and go, with periods when she is functional and others during which she experiences considerable confusion. The family is uncertain when these signs and symptoms first appeared, but are clear that these deficits are having an impact on her day-to-day life. She can conduct activities of daily living, but with increasing difficulty—and only with help from her husband for tasks that require complex order and movement.

Over several months, Ms. L’s gait stability decreases and she begins to rely on a walker to keep from falling. On the Montreal Cognitive Assessment screening for cognitive dysfunction, she scores 19 out of 30 (normal range >25). This suggests cognitive impairment greater than expected for her age, compared with normal controls, and, when coupled with her functional impairment, raises the possibility of a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

a) donepezil

b) memantine

c) quetiapine

d) low-dose clozapine

The authors’ observations

Limited literature exists of placebo-controlled, large-scale studies on DLB treatment. Cholinesterase inhibitors have shown some symptomatic benefit, including for hallucinations.1-3 Memantine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blocker, shows mixed results.4 Many studies explore the use of neuroleptics for treating hallucinations in psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) but, in DLB, the literature primarily consists of case reports.2 Much of DLB treatment is inferred and intermixed with studies on PDD.5,6

Low-dose clozapine has become a standard treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease based on the findings of several trials.6 Despite its side-effect profile, clozapine has been shown to ameliorate hallucinations in PDD without exacerbating parkinsonian symptoms,7,8 and is the only medication with proven efficacy in PDD.2 The French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group demonstrated relief of psychotic symptoms of Parkinson’s disease with clozapine, 6.25 mg/d.9 The Clozapine Study Group found complete resolution of hallucinations in some patients within 1 day of initiating clozapine. Among patients in this study who did not see immediate benefit, most showed significant improvement of psychotic symptoms in 1 or 2 weeks.10

TREATMENT Few options

Ms. L’s psychiatrist and primary care physician start her on a series of medications. Donepezil is initiated for suspected dementia. We begin a trial of quetiapine to address the hallucinations, but the drug makes her movement symptoms worse. Risperidone also is tried but, again, the drugs make movement symptoms, particularly gait instability, tremor, and rigidity worse without alleviating the hallucinations. Neuroleptics seem to exacerbate confusion. Because of worsening depressive symptoms and our concern over possible pseudodementia, we try several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and mirtazapine. Antidepressants have little effect on her depressive symptoms and do not improve hallucinations or insomnia.

Ms. L’s signs and symptoms become worse over the next few months, with more severe hallucinations, agitation, insomnia, and gait instability. Her agitation over the hallucinations increases and she begins pouring bleach around herself in bed and spraying her house with toxic bug spray. Ms. L’s family brings her to the hospital after they observe her scratching the hallucinatory creatures off of her skin with a razor blade and trying to pry them out of her mouth with a piece of metal.

In the hospital, medical and neurologic workups rule out organic causes for her symptoms and signs. MRI is consistent with imaging from 6 months earlier. Focal neurologic signs are absent. Blood work is within normal limits, failing to reveal any pathology that would suggest a cause for her symptoms and signs, such as syphilis, vitamin deficiency, and Lyme disease.

Ms. L’s symptoms were consistent with consensus guideline criteria for a clinical diagnosis of DLB (Table 1).11-18

She is started on low-dose quetiapine, which she tolerates poorly with worsening confusion, rigidity, tremor, and gait instability. Because other agents failed, Ms. L’s providers and family decide on a trial of clozapine.

Within 24 hours after the first dose of clozapine, 25 mg, sleep improves, the tactile component of hallucinations diminish, and she begins to spend increasing periods of time “observing the creatures” rather than fighting with them.

Over the next few days, Ms. L’s attitude towards the creatures changes. Now, as she sits observing them intently, the hallucinations evolve: rather than tormenting her and causing distress, the plant-creatures burst apart and a miniature knight on horseback charges out. The rest of the creatures then gather into a rank and file and the knight leads them to the nearest exit.

Clozapine is titrated to 50 mg/d, which she tolerates well without exacerbation of cognitive symptoms or movement disorder. The only notable adverse effect at the time of her discharge is sialorrhea.

with an antipsychotic?

a) start low and go slow

b) monitor her heart rate and blood pressure

c) readminister the Montreal Cognitive Assessment

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Ideally, in psychosis, antipsychotics eliminate positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. In DLB, the aim is to alleviate the agitation and suffering brought on by the psychotic symptoms without exacerbating other motor and cognitive symptoms. The hallucinations are obstinate, and it is a well-known quality of this disorder that patients are exceptionally susceptible to a range of antipsychotic side effects including cognitive impairment, fatigue, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and parkinsonism.19

Treatment in DLB requires trial and error, and medications with fewer associated risks should be administered first. Patients with DLB treated with neuroleptics have an increased risk of death compared with those who are not treated.19 Moreover, prescribing information for clozapine includes a black-box warning that the drug:

- is not approved for dementia-related psychosis and

- is associated with an increased risk of death in elderly patients with these conditions, similar to what is seen with other neuroleptics.20

Despite these well-known concerns, it remains difficult for clinicians not to try to treat the distress caused by these symptoms.

We chose clozapine for Ms. L because:

- other neuroleptics failed

- acetylcholinesterase inhibitors did not alleviate Ms. L’s psychosis and associated behavioral disturbance

- there is substantial evidence that the drug can be effective in Parkinson’s disease with psychosis.

There is controversy regarding use of clozapine in DLB. In one case series, clozapine trigger extreme neuroleptic reactions in some patients, similar to what occurs with other second-generation antipsychotics.21 Another case series provides examples of the drug’s efficacy in treating hallucinations and delusions with minimal adverse effects.22

It is important to emphasize that Ms. L’s hallucinations did not go away; rather, they changed to a more benign presentation that she could manage and, occasionally, found pleasant. Ultimately, her agitation—the primary target of treatment—improved markedly with the arrival of the knight in shining armor.

Treatment recommendations

If neuropsychiatric symptoms in DLB are the primary concern of the patient and family, we recommend the following:

- Begin treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor. The best evidence exists for rivastigmine and donepezil. These drugs have a low risk of side effects, which are primarily gastrointestinal effects with some reports of worsening extrapyramidal symptoms.23-25

- If the patient obtains minimal benefit or develops a significant adverse effect from cholinesterase inhibitors, consider memantine. Its efficacy is under examination and results are mixed; it can be used in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors.26-28

- If psychotic symptoms are upsetting and refractory to other therapies, consider antipsychotics. Avoid first-generation antipsychotics. The American Psychiatric Association recommends aripiprazole or quetiapine initially, although there is little evidence comparing neuroleptics in DLB.29 Because of its risks, reserve clozapine for refractory cases. An exception might be made for patients sensitive to extrapyramidal effects, in whom clozapine could be considered earlier.

There are no formal neuroleptic dosing guidelines beyond a general urging towards minimalism. Mosimann and McKeith30 recommend clozapine, 12.5 mg/d; olanzapine, 2.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.25 mg/d; or quetiapine, 12.5 mg/d. Such dosages might be effective while producing only minimal side effects.9,31

SSRIs and other antidepressants have not been shown to improve neuropsychiatric symptoms, and often are poorly tolerated.32

One study found efficacy with electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant patients.33

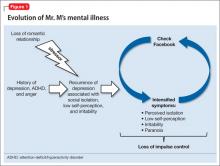

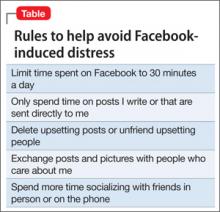

In addition to these treatments, nonpharmaceutical interventions should be employed from the earliest stages of diagnosis and treatment (Table 2). See the Figure for an algorithm for treating DLB. These include educational and behavioral interventions, social support, psychological interventions, and environmental therapies and modifications.

OUTCOME New friends

The creatures return from time to time, Ms. L reports, but are no longer upsetting because the white knight (a sort of mental deus ex machina) leads the once-terrifying things away. She describes the hallucination as a kind of zoological observation, refers to the creatures that once horrified her as “her friends,” and chuckles as she observes their natural history. This new, far more benign hallucination becomes a mainstay of her symptoms, and she is discharged to the care of her husband and family.

Soon after her discharge, her hallucinations resolved completely, but returned briefly when Ms. L resumed smoking cigarettes because smoking is known to lower clozapine serum levels.34

Bottom Line

Consider a low dosage of a neuroleptic when a patient suffers significant distress and behavioral disturbance related to psychotic symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and those problems are not relieved by other agents. Low-dose clozapine is an option for refractory psychotic symptoms or in patients with severe extrapyramidal sensitivity. Start low, and go slow.

Related Resources

- Bishnoi RJ, Grossberg GT, Manepalli J. Differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(11):22-27.

- McKeith I, Emre M. Management of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. In: Emre M, ed. Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2010:245-256.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Clozapine • Clozaril Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Donepezil • Aricept Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Memantine • Namenda Rivastigmine • Exelon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Strange creatures

Ms. L, age 78, is admitted to the inpatient unit for treatment of psychosis and behavioral changes. In the months before this admission, she had visited the emergency room several times for recurrent falls. CT scans of the head show no acute changes; brain and spinal MRI reveal evidence of chronic white matter disease and degenerative changes of the spine. Medical workup is unremarkable and includes evaluation for syncope and ambulation impairments related to degenerative disease of the hip joints.

Ms. L and her family are instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician and a neurologist for neuromuscular workup.

She next presents to her primary care physician, describing hallucinations of strangers walking around her house. Over a few weeks, hallucinations expand to include a fixed hallucination of creatures that she describes as having qualities of insects and plants, “piling up” around her. She describes tactile hallucinations of these creatures crawling on her skin, and she tracks their movements around her. She complains of vivid visual hallucinations of these creatures spinning webs across the room and she says she keeps the lights on at night. Ms. L becomes anxious and depressed, and her insomnia becomes worse.

She is referred for outpatient psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Ms. L’s family notes lapses of short-term memory, disorganization, and difficulty with tasks such as cooking because she has trouble following steps. These deficits come and go, with periods when she is functional and others during which she experiences considerable confusion. The family is uncertain when these signs and symptoms first appeared, but are clear that these deficits are having an impact on her day-to-day life. She can conduct activities of daily living, but with increasing difficulty—and only with help from her husband for tasks that require complex order and movement.

Over several months, Ms. L’s gait stability decreases and she begins to rely on a walker to keep from falling. On the Montreal Cognitive Assessment screening for cognitive dysfunction, she scores 19 out of 30 (normal range >25). This suggests cognitive impairment greater than expected for her age, compared with normal controls, and, when coupled with her functional impairment, raises the possibility of a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

a) donepezil

b) memantine

c) quetiapine

d) low-dose clozapine

The authors’ observations

Limited literature exists of placebo-controlled, large-scale studies on DLB treatment. Cholinesterase inhibitors have shown some symptomatic benefit, including for hallucinations.1-3 Memantine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blocker, shows mixed results.4 Many studies explore the use of neuroleptics for treating hallucinations in psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) but, in DLB, the literature primarily consists of case reports.2 Much of DLB treatment is inferred and intermixed with studies on PDD.5,6

Low-dose clozapine has become a standard treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease based on the findings of several trials.6 Despite its side-effect profile, clozapine has been shown to ameliorate hallucinations in PDD without exacerbating parkinsonian symptoms,7,8 and is the only medication with proven efficacy in PDD.2 The French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group demonstrated relief of psychotic symptoms of Parkinson’s disease with clozapine, 6.25 mg/d.9 The Clozapine Study Group found complete resolution of hallucinations in some patients within 1 day of initiating clozapine. Among patients in this study who did not see immediate benefit, most showed significant improvement of psychotic symptoms in 1 or 2 weeks.10

TREATMENT Few options

Ms. L’s psychiatrist and primary care physician start her on a series of medications. Donepezil is initiated for suspected dementia. We begin a trial of quetiapine to address the hallucinations, but the drug makes her movement symptoms worse. Risperidone also is tried but, again, the drugs make movement symptoms, particularly gait instability, tremor, and rigidity worse without alleviating the hallucinations. Neuroleptics seem to exacerbate confusion. Because of worsening depressive symptoms and our concern over possible pseudodementia, we try several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and mirtazapine. Antidepressants have little effect on her depressive symptoms and do not improve hallucinations or insomnia.

Ms. L’s signs and symptoms become worse over the next few months, with more severe hallucinations, agitation, insomnia, and gait instability. Her agitation over the hallucinations increases and she begins pouring bleach around herself in bed and spraying her house with toxic bug spray. Ms. L’s family brings her to the hospital after they observe her scratching the hallucinatory creatures off of her skin with a razor blade and trying to pry them out of her mouth with a piece of metal.

In the hospital, medical and neurologic workups rule out organic causes for her symptoms and signs. MRI is consistent with imaging from 6 months earlier. Focal neurologic signs are absent. Blood work is within normal limits, failing to reveal any pathology that would suggest a cause for her symptoms and signs, such as syphilis, vitamin deficiency, and Lyme disease.

Ms. L’s symptoms were consistent with consensus guideline criteria for a clinical diagnosis of DLB (Table 1).11-18

She is started on low-dose quetiapine, which she tolerates poorly with worsening confusion, rigidity, tremor, and gait instability. Because other agents failed, Ms. L’s providers and family decide on a trial of clozapine.

Within 24 hours after the first dose of clozapine, 25 mg, sleep improves, the tactile component of hallucinations diminish, and she begins to spend increasing periods of time “observing the creatures” rather than fighting with them.

Over the next few days, Ms. L’s attitude towards the creatures changes. Now, as she sits observing them intently, the hallucinations evolve: rather than tormenting her and causing distress, the plant-creatures burst apart and a miniature knight on horseback charges out. The rest of the creatures then gather into a rank and file and the knight leads them to the nearest exit.

Clozapine is titrated to 50 mg/d, which she tolerates well without exacerbation of cognitive symptoms or movement disorder. The only notable adverse effect at the time of her discharge is sialorrhea.

with an antipsychotic?

a) start low and go slow

b) monitor her heart rate and blood pressure

c) readminister the Montreal Cognitive Assessment

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Ideally, in psychosis, antipsychotics eliminate positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. In DLB, the aim is to alleviate the agitation and suffering brought on by the psychotic symptoms without exacerbating other motor and cognitive symptoms. The hallucinations are obstinate, and it is a well-known quality of this disorder that patients are exceptionally susceptible to a range of antipsychotic side effects including cognitive impairment, fatigue, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and parkinsonism.19

Treatment in DLB requires trial and error, and medications with fewer associated risks should be administered first. Patients with DLB treated with neuroleptics have an increased risk of death compared with those who are not treated.19 Moreover, prescribing information for clozapine includes a black-box warning that the drug:

- is not approved for dementia-related psychosis and

- is associated with an increased risk of death in elderly patients with these conditions, similar to what is seen with other neuroleptics.20

Despite these well-known concerns, it remains difficult for clinicians not to try to treat the distress caused by these symptoms.

We chose clozapine for Ms. L because:

- other neuroleptics failed

- acetylcholinesterase inhibitors did not alleviate Ms. L’s psychosis and associated behavioral disturbance

- there is substantial evidence that the drug can be effective in Parkinson’s disease with psychosis.

There is controversy regarding use of clozapine in DLB. In one case series, clozapine trigger extreme neuroleptic reactions in some patients, similar to what occurs with other second-generation antipsychotics.21 Another case series provides examples of the drug’s efficacy in treating hallucinations and delusions with minimal adverse effects.22

It is important to emphasize that Ms. L’s hallucinations did not go away; rather, they changed to a more benign presentation that she could manage and, occasionally, found pleasant. Ultimately, her agitation—the primary target of treatment—improved markedly with the arrival of the knight in shining armor.

Treatment recommendations

If neuropsychiatric symptoms in DLB are the primary concern of the patient and family, we recommend the following:

- Begin treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor. The best evidence exists for rivastigmine and donepezil. These drugs have a low risk of side effects, which are primarily gastrointestinal effects with some reports of worsening extrapyramidal symptoms.23-25

- If the patient obtains minimal benefit or develops a significant adverse effect from cholinesterase inhibitors, consider memantine. Its efficacy is under examination and results are mixed; it can be used in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors.26-28

- If psychotic symptoms are upsetting and refractory to other therapies, consider antipsychotics. Avoid first-generation antipsychotics. The American Psychiatric Association recommends aripiprazole or quetiapine initially, although there is little evidence comparing neuroleptics in DLB.29 Because of its risks, reserve clozapine for refractory cases. An exception might be made for patients sensitive to extrapyramidal effects, in whom clozapine could be considered earlier.

There are no formal neuroleptic dosing guidelines beyond a general urging towards minimalism. Mosimann and McKeith30 recommend clozapine, 12.5 mg/d; olanzapine, 2.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.25 mg/d; or quetiapine, 12.5 mg/d. Such dosages might be effective while producing only minimal side effects.9,31

SSRIs and other antidepressants have not been shown to improve neuropsychiatric symptoms, and often are poorly tolerated.32

One study found efficacy with electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant patients.33

In addition to these treatments, nonpharmaceutical interventions should be employed from the earliest stages of diagnosis and treatment (Table 2). See the Figure for an algorithm for treating DLB. These include educational and behavioral interventions, social support, psychological interventions, and environmental therapies and modifications.

OUTCOME New friends

The creatures return from time to time, Ms. L reports, but are no longer upsetting because the white knight (a sort of mental deus ex machina) leads the once-terrifying things away. She describes the hallucination as a kind of zoological observation, refers to the creatures that once horrified her as “her friends,” and chuckles as she observes their natural history. This new, far more benign hallucination becomes a mainstay of her symptoms, and she is discharged to the care of her husband and family.

Soon after her discharge, her hallucinations resolved completely, but returned briefly when Ms. L resumed smoking cigarettes because smoking is known to lower clozapine serum levels.34

Bottom Line

Consider a low dosage of a neuroleptic when a patient suffers significant distress and behavioral disturbance related to psychotic symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and those problems are not relieved by other agents. Low-dose clozapine is an option for refractory psychotic symptoms or in patients with severe extrapyramidal sensitivity. Start low, and go slow.

Related Resources

- Bishnoi RJ, Grossberg GT, Manepalli J. Differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(11):22-27.

- McKeith I, Emre M. Management of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. In: Emre M, ed. Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2010:245-256.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Clozapine • Clozaril Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Donepezil • Aricept Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Memantine • Namenda Rivastigmine • Exelon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wesnes KA, McKeith IG, Ferrara R, et al. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised placebo-controlled international study using the Cognitive Drug Research computerized assessment system. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002; 13(3):183-192.

2. Weintraub D, Hurtig HI. Presentation and management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1491-1498.

3. McKeith IG, Wesnes KA, Perry E, et al. Hallucinations predict attentional improvements with rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(1):94-100.

4. Emre M, Tsolaki , Bonuccelli U, et al. Memantine for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):969-977.

5. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Clinical trials of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(5):492-501.

6. Drach LM. Drug treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia--common features and differences [in German]. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2011; 34(2):47-52.

7. Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Ziegenbein M, et al. Treating dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: Structured review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):165-171.

8. Marti MJ, Tolosa E, de la Cerda A. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2007;254(suppl 5):41-48.

9. French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group. Clozapine in drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9169):2041-2042.

10. Friedman JH, Factor SA. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(2):201-211.

11. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113-1124.

12. McKeith IG, Ballard CG, Perry RH et al. Prospective validation of consensus criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1050-1058.

13. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863-1872.

14. McKeith IG. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(suppl 3):417-423.

15. Geser F, Wenning GK, Poewe W, et al. How to diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies: state of the art. Mov Disord. 2005;20(suppl 12):S11-20.

16. Latoo J, Jan F. Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical review. British Journal of Medical Practioners. 2008;1(1):10-14.

17. McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(3):333-341.

18. Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, et al; Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee. SIC Task Force Appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18(5):467-486.

19. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305(6855):673-678.

20. Clozapine Monitoring Guidelines. 2008. http://www.clozapineregistry.com/resuming_treatment_after_interruption.pdf.ashx. Accessed October 31, 2013.

21. Burke WJ, Pfeiffer RF, McComb RD. Neuroleptic sensitivity to clozapine in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10(2):227-229.

22. Chacko RC, Hurley RA, Jankovic J. Clozapine use in diffuse Lewy body disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5(2):206-208.

23. McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031-2036

24. Mori E, Ikeda M, Kosaka K; Donepezil-DLB Study Investiagors. Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2012; 72(1):41-52.

25. Ukai K, Aleksic B, Ishihara R, et al. Efficacy of donepezil for the treatment of visual and multiple sensory hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies. Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and Therapeutics. 2011;2:56-58.

26. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Memantine in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):613-618.

27. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ. Melatonin for treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder in neurologic disorders: results in 14 patients. Sleep Med. 2003;4(4):281-284.

28. Mathys ML, McCarrell J, Sleeper RB, et al. Visual hallucinations treated with the reinitiation of memantine in a patient with Lewy body dementia. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(2):e10.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pdfaccess.ashx?ResourceID=243205&PDFSource=6. Accessed November 1, 2013.

30. Mosimann U, McKeith IG. Dementia with lewy bodies—diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:131-142.

31. Baskys A, Davis P Atypical antipsychotic quetiapine in the treatment of the psychosis associated with Lewy body dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:S63.

32. Culo S, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Treating neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized controlled-trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(4):306-364.

33. Takahashi S, Mizukami K, Yasuno F, et al. Depression associated with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and the effect of somatotherapy. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):56-61.

34. van der Weide J, Steijns LS, van Weelden MJ. The effect of smoking and cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 genetic polymorphism on clozapine clearance and dose requirement. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(3):169-172.

1. Wesnes KA, McKeith IG, Ferrara R, et al. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised placebo-controlled international study using the Cognitive Drug Research computerized assessment system. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002; 13(3):183-192.

2. Weintraub D, Hurtig HI. Presentation and management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1491-1498.

3. McKeith IG, Wesnes KA, Perry E, et al. Hallucinations predict attentional improvements with rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(1):94-100.

4. Emre M, Tsolaki , Bonuccelli U, et al. Memantine for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):969-977.

5. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Clinical trials of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(5):492-501.

6. Drach LM. Drug treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia--common features and differences [in German]. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2011; 34(2):47-52.

7. Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Ziegenbein M, et al. Treating dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: Structured review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):165-171.

8. Marti MJ, Tolosa E, de la Cerda A. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2007;254(suppl 5):41-48.

9. French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group. Clozapine in drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9169):2041-2042.

10. Friedman JH, Factor SA. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(2):201-211.

11. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113-1124.

12. McKeith IG, Ballard CG, Perry RH et al. Prospective validation of consensus criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1050-1058.

13. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863-1872.

14. McKeith IG. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(suppl 3):417-423.

15. Geser F, Wenning GK, Poewe W, et al. How to diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies: state of the art. Mov Disord. 2005;20(suppl 12):S11-20.

16. Latoo J, Jan F. Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical review. British Journal of Medical Practioners. 2008;1(1):10-14.

17. McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(3):333-341.

18. Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, et al; Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee. SIC Task Force Appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18(5):467-486.

19. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305(6855):673-678.

20. Clozapine Monitoring Guidelines. 2008. http://www.clozapineregistry.com/resuming_treatment_after_interruption.pdf.ashx. Accessed October 31, 2013.

21. Burke WJ, Pfeiffer RF, McComb RD. Neuroleptic sensitivity to clozapine in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10(2):227-229.

22. Chacko RC, Hurley RA, Jankovic J. Clozapine use in diffuse Lewy body disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5(2):206-208.

23. McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031-2036

24. Mori E, Ikeda M, Kosaka K; Donepezil-DLB Study Investiagors. Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2012; 72(1):41-52.

25. Ukai K, Aleksic B, Ishihara R, et al. Efficacy of donepezil for the treatment of visual and multiple sensory hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies. Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and Therapeutics. 2011;2:56-58.

26. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Memantine in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):613-618.

27. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ. Melatonin for treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder in neurologic disorders: results in 14 patients. Sleep Med. 2003;4(4):281-284.

28. Mathys ML, McCarrell J, Sleeper RB, et al. Visual hallucinations treated with the reinitiation of memantine in a patient with Lewy body dementia. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(2):e10.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pdfaccess.ashx?ResourceID=243205&PDFSource=6. Accessed November 1, 2013.

30. Mosimann U, McKeith IG. Dementia with lewy bodies—diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:131-142.

31. Baskys A, Davis P Atypical antipsychotic quetiapine in the treatment of the psychosis associated with Lewy body dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:S63.

32. Culo S, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Treating neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized controlled-trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(4):306-364.

33. Takahashi S, Mizukami K, Yasuno F, et al. Depression associated with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and the effect of somatotherapy. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):56-61.

34. van der Weide J, Steijns LS, van Weelden MJ. The effect of smoking and cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 genetic polymorphism on clozapine clearance and dose requirement. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(3):169-172.

SSRIs in pregnancy: What should you tell your depressed patient?

Mrs. D is a 28-year-old married woman who became depressed after her first pregnancy. The depression was treated successfully with paroxetine, 20 mg/d. Before beginning treatment, she reported low mood, spent most of the day in bed, was unable to care for herself, and confessed to thoughts of harming her child.

Mrs. D presents to your clinic asking whether she should continue her selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because she and her husband are thinking about having a second child. Recently, she tells you, she saw a news article suggesting that antidepressants show little benefit, and she is concerned that her baby might have a heart defect if she continues paroxetine.

Mrs. D wants to discontinue her medication, but her husband thought she should discuss doing so with you first. During this visit she takes a pregnancy test, which is positive. She wants to know what to do.

women experience depression; 3.8% of pregnant women receive an SSRI.1 SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy, but their use remains controversial. There is disagreement about the maternal and neonatal risks of untreated depression and SSRI exposure.2-10 Media reports of studies demonstrating adverse effects associated with SSRIs may generate fear among women, possibly prompting them to self-discontinue medication.

Evidence of risks and benefits

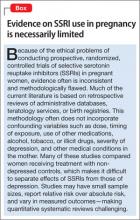

Clinicians should be aware of possible adverse effects of SSRI use and untreated depression (Table).2-10 The available data precludes definitive associations between untreated depression and poor outcomes (Box). Studies of SSRI use during pregnancy have shown conflicting results for all potential outcomes. Absolute risk, with the exception of neonatal adaptation syndrome, is estimated to be small. Neonatal adaptation syndrome—which is characterized by jitteriness, poor muscle tone, weak cries, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, low Apgar scores, and seizures—occurs in 15% to 30% of infants born to mothers taking SSRIs, but it is transient and resolves during the first weeks of life.

Treatment recommendations

Given the conflicting nature of the evidence, treatment plans should be individualized, weighing the risks and benefits of treatment and the patient’s beliefs and psychiatric history. Consider severity of symptoms and history, including effective therapy and history of relapse. For women with mild or moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy might be an appropriate first-line therapy. However, non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions might not relieve severe depression or be available to all women. When discontinuing an SSRI before pregnancy, counsel the patient to not discontinue the medication abruptly and provide an appropriate taper schedule. See Related Resources for detailed recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Reviewing the SSRI literature regarding pregnancy

Sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and fluoxetine are the most studied SSRIs during pregnancy; little information is available on escitalopram and fluvoxamine.11 Prescribing preference generally is given to the medications with the most evidence; paroxetine may be an exception. In 2005, the FDA requested a change in paroxetine’s pregnancy category from C to D, indicating that adequate studies demonstrated a risk of congenital cardiac malformations.11 Additional studies have been conducted, and the teratogenicity of paroxetine is debatable. A recent review reports 8 studies that suggest a malformation risk, compared with 15 studies that show no risk.12

The American Academy of Pediatrics considers SSRIs to be compatible with breast-feeding.13 The best-studied drugs include sertraline and paroxetine. Fluoxetine should be avoided when possible because a long elimination half-life can cause the drug to accumulate in the newborn, increasing the risk of irritability, hypertonia, sedation, and poor suckle.7

There is no best SSRI for all pregnant women. Risks and benefits, including previous treatment success and failure, should be taken into account before starting or switching therapy. Whenever possible, consider monotherapy to avoid compounding the risk of harm.

Related Resources

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:403-413.

- MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. www.womensmentalhealth.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Escitalopram • Lexapro Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosures

Dr. Leino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Ellingrod receives grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

1. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. Patterns of antidepressant medication use among pregnant women in a United States population. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(2):264-270.

2. Domar AD, Moragianni VA, Ryley DA, et al. The risks of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in infertile women: a review of the impact on fertility, pregnancy, neonatal health and beyond. Hum Reprod. 20113;28(1):160-171.

3. Davalos DB, Yadon CA, Tregellas HC. Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):1-14.

4. Spinelli M. Antidepressant treatment during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):121-124.

5. Oyebode F, Rastogi A, Berrisford G, et al. Psychotropics in pregnancy: safety and other considerations. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135(1):71-77.

6. Byatt N, Deligiannidis KM, Freeman MP. Antidepressant use in pregnancy: a critical review focused on risks and controversies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(2):94-114.

7. Sie SD, Wennink JM, van Driel JJ, et al. Maternal use of SSRIs, SNRIs and NaSSAs: practical recommendations during pregnancy and lactation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(6):F472-476.

8. Jimenez-Solem E, Andersen JT, Petersen M, et al. SSRI use during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and neonatal mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):299-304.

9. Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, et al. Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Daru. 2012;20(1):75.

10. Stephansson O, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and infant mortality. JAMA. 2013;309(1):48-54.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: paroxetine. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/Public HealthAdvisories/ucm051731.htm. Published December 8, 2005. Accessed September 27, 2013.

12. Koren G, Nordeng H. Antidepressant use during pregnancy: the benefit-risk ratio. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):157-163.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776-789.

Mrs. D is a 28-year-old married woman who became depressed after her first pregnancy. The depression was treated successfully with paroxetine, 20 mg/d. Before beginning treatment, she reported low mood, spent most of the day in bed, was unable to care for herself, and confessed to thoughts of harming her child.

Mrs. D presents to your clinic asking whether she should continue her selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because she and her husband are thinking about having a second child. Recently, she tells you, she saw a news article suggesting that antidepressants show little benefit, and she is concerned that her baby might have a heart defect if she continues paroxetine.

Mrs. D wants to discontinue her medication, but her husband thought she should discuss doing so with you first. During this visit she takes a pregnancy test, which is positive. She wants to know what to do.

women experience depression; 3.8% of pregnant women receive an SSRI.1 SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy, but their use remains controversial. There is disagreement about the maternal and neonatal risks of untreated depression and SSRI exposure.2-10 Media reports of studies demonstrating adverse effects associated with SSRIs may generate fear among women, possibly prompting them to self-discontinue medication.

Evidence of risks and benefits

Clinicians should be aware of possible adverse effects of SSRI use and untreated depression (Table).2-10 The available data precludes definitive associations between untreated depression and poor outcomes (Box). Studies of SSRI use during pregnancy have shown conflicting results for all potential outcomes. Absolute risk, with the exception of neonatal adaptation syndrome, is estimated to be small. Neonatal adaptation syndrome—which is characterized by jitteriness, poor muscle tone, weak cries, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, low Apgar scores, and seizures—occurs in 15% to 30% of infants born to mothers taking SSRIs, but it is transient and resolves during the first weeks of life.

Treatment recommendations

Given the conflicting nature of the evidence, treatment plans should be individualized, weighing the risks and benefits of treatment and the patient’s beliefs and psychiatric history. Consider severity of symptoms and history, including effective therapy and history of relapse. For women with mild or moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy might be an appropriate first-line therapy. However, non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions might not relieve severe depression or be available to all women. When discontinuing an SSRI before pregnancy, counsel the patient to not discontinue the medication abruptly and provide an appropriate taper schedule. See Related Resources for detailed recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Reviewing the SSRI literature regarding pregnancy

Sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and fluoxetine are the most studied SSRIs during pregnancy; little information is available on escitalopram and fluvoxamine.11 Prescribing preference generally is given to the medications with the most evidence; paroxetine may be an exception. In 2005, the FDA requested a change in paroxetine’s pregnancy category from C to D, indicating that adequate studies demonstrated a risk of congenital cardiac malformations.11 Additional studies have been conducted, and the teratogenicity of paroxetine is debatable. A recent review reports 8 studies that suggest a malformation risk, compared with 15 studies that show no risk.12

The American Academy of Pediatrics considers SSRIs to be compatible with breast-feeding.13 The best-studied drugs include sertraline and paroxetine. Fluoxetine should be avoided when possible because a long elimination half-life can cause the drug to accumulate in the newborn, increasing the risk of irritability, hypertonia, sedation, and poor suckle.7

There is no best SSRI for all pregnant women. Risks and benefits, including previous treatment success and failure, should be taken into account before starting or switching therapy. Whenever possible, consider monotherapy to avoid compounding the risk of harm.

Related Resources

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:403-413.

- MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. www.womensmentalhealth.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Escitalopram • Lexapro Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosures

Dr. Leino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Ellingrod receives grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Mrs. D is a 28-year-old married woman who became depressed after her first pregnancy. The depression was treated successfully with paroxetine, 20 mg/d. Before beginning treatment, she reported low mood, spent most of the day in bed, was unable to care for herself, and confessed to thoughts of harming her child.

Mrs. D presents to your clinic asking whether she should continue her selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because she and her husband are thinking about having a second child. Recently, she tells you, she saw a news article suggesting that antidepressants show little benefit, and she is concerned that her baby might have a heart defect if she continues paroxetine.

Mrs. D wants to discontinue her medication, but her husband thought she should discuss doing so with you first. During this visit she takes a pregnancy test, which is positive. She wants to know what to do.

women experience depression; 3.8% of pregnant women receive an SSRI.1 SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy, but their use remains controversial. There is disagreement about the maternal and neonatal risks of untreated depression and SSRI exposure.2-10 Media reports of studies demonstrating adverse effects associated with SSRIs may generate fear among women, possibly prompting them to self-discontinue medication.

Evidence of risks and benefits

Clinicians should be aware of possible adverse effects of SSRI use and untreated depression (Table).2-10 The available data precludes definitive associations between untreated depression and poor outcomes (Box). Studies of SSRI use during pregnancy have shown conflicting results for all potential outcomes. Absolute risk, with the exception of neonatal adaptation syndrome, is estimated to be small. Neonatal adaptation syndrome—which is characterized by jitteriness, poor muscle tone, weak cries, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, low Apgar scores, and seizures—occurs in 15% to 30% of infants born to mothers taking SSRIs, but it is transient and resolves during the first weeks of life.

Treatment recommendations

Given the conflicting nature of the evidence, treatment plans should be individualized, weighing the risks and benefits of treatment and the patient’s beliefs and psychiatric history. Consider severity of symptoms and history, including effective therapy and history of relapse. For women with mild or moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy might be an appropriate first-line therapy. However, non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions might not relieve severe depression or be available to all women. When discontinuing an SSRI before pregnancy, counsel the patient to not discontinue the medication abruptly and provide an appropriate taper schedule. See Related Resources for detailed recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Reviewing the SSRI literature regarding pregnancy

Sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and fluoxetine are the most studied SSRIs during pregnancy; little information is available on escitalopram and fluvoxamine.11 Prescribing preference generally is given to the medications with the most evidence; paroxetine may be an exception. In 2005, the FDA requested a change in paroxetine’s pregnancy category from C to D, indicating that adequate studies demonstrated a risk of congenital cardiac malformations.11 Additional studies have been conducted, and the teratogenicity of paroxetine is debatable. A recent review reports 8 studies that suggest a malformation risk, compared with 15 studies that show no risk.12

The American Academy of Pediatrics considers SSRIs to be compatible with breast-feeding.13 The best-studied drugs include sertraline and paroxetine. Fluoxetine should be avoided when possible because a long elimination half-life can cause the drug to accumulate in the newborn, increasing the risk of irritability, hypertonia, sedation, and poor suckle.7

There is no best SSRI for all pregnant women. Risks and benefits, including previous treatment success and failure, should be taken into account before starting or switching therapy. Whenever possible, consider monotherapy to avoid compounding the risk of harm.

Related Resources

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:403-413.

- MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. www.womensmentalhealth.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Escitalopram • Lexapro Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosures

Dr. Leino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Ellingrod receives grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

1. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. Patterns of antidepressant medication use among pregnant women in a United States population. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(2):264-270.

2. Domar AD, Moragianni VA, Ryley DA, et al. The risks of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in infertile women: a review of the impact on fertility, pregnancy, neonatal health and beyond. Hum Reprod. 20113;28(1):160-171.

3. Davalos DB, Yadon CA, Tregellas HC. Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):1-14.

4. Spinelli M. Antidepressant treatment during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):121-124.

5. Oyebode F, Rastogi A, Berrisford G, et al. Psychotropics in pregnancy: safety and other considerations. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135(1):71-77.

6. Byatt N, Deligiannidis KM, Freeman MP. Antidepressant use in pregnancy: a critical review focused on risks and controversies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(2):94-114.

7. Sie SD, Wennink JM, van Driel JJ, et al. Maternal use of SSRIs, SNRIs and NaSSAs: practical recommendations during pregnancy and lactation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(6):F472-476.

8. Jimenez-Solem E, Andersen JT, Petersen M, et al. SSRI use during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and neonatal mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):299-304.

9. Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, et al. Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Daru. 2012;20(1):75.

10. Stephansson O, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and infant mortality. JAMA. 2013;309(1):48-54.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: paroxetine. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/Public HealthAdvisories/ucm051731.htm. Published December 8, 2005. Accessed September 27, 2013.

12. Koren G, Nordeng H. Antidepressant use during pregnancy: the benefit-risk ratio. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):157-163.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776-789.

1. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. Patterns of antidepressant medication use among pregnant women in a United States population. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(2):264-270.

2. Domar AD, Moragianni VA, Ryley DA, et al. The risks of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in infertile women: a review of the impact on fertility, pregnancy, neonatal health and beyond. Hum Reprod. 20113;28(1):160-171.

3. Davalos DB, Yadon CA, Tregellas HC. Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):1-14.

4. Spinelli M. Antidepressant treatment during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):121-124.

5. Oyebode F, Rastogi A, Berrisford G, et al. Psychotropics in pregnancy: safety and other considerations. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135(1):71-77.

6. Byatt N, Deligiannidis KM, Freeman MP. Antidepressant use in pregnancy: a critical review focused on risks and controversies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(2):94-114.

7. Sie SD, Wennink JM, van Driel JJ, et al. Maternal use of SSRIs, SNRIs and NaSSAs: practical recommendations during pregnancy and lactation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(6):F472-476.

8. Jimenez-Solem E, Andersen JT, Petersen M, et al. SSRI use during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and neonatal mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):299-304.

9. Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, et al. Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Daru. 2012;20(1):75.

10. Stephansson O, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth and infant mortality. JAMA. 2013;309(1):48-54.