User login

Clinical Session

ELIZABETH BARLOW, MD, MPP, wants all hospitalists to know that upper-extremity DVT (UEDVT) is on the rise. Although most think of it “as a lesser entity,” Dr. Barlow told a jam-packed clinical-track session at HM10 the data show a higher rate of pulmonary em-bolism [PE] occurrence in UEDVT than was first thought. “So I think treating it seriously is important,” she said.

Dr. Barlow, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, outlined the case for greater attention to UEDVT during “Controversies in Anticoagu-lation and Thrombosis. “UEDVTs make up 1% to 4% of all DVTs in the U.S., and nearly 80% of UEDVT cases are provoked.

Much of the rise in—and controversy—UEDVT is due to the increased use of in-dwelling catheters, primarily how long to leave the catheter in place and when to remove it. “Judicious use of catheters is necessary. You should leave it in, if you need it,” Dr. Barlow said, adding that hospitalists should weigh the benefits and risks of PICC lines.

Some of Dr. Barlow’s key take-home points:

- Treat UEDVT seriously;

- Understand there is a higher rate of PE than previously thought;

- Insert central-vein catheters judiciously, and keep them in if you still need them;

- Manage the duration of therapy parallel to that of lower extremity DVT; and

- Routine thrombolytics use isn’t indicated at this time. HM10

ELIZABETH BARLOW, MD, MPP, wants all hospitalists to know that upper-extremity DVT (UEDVT) is on the rise. Although most think of it “as a lesser entity,” Dr. Barlow told a jam-packed clinical-track session at HM10 the data show a higher rate of pulmonary em-bolism [PE] occurrence in UEDVT than was first thought. “So I think treating it seriously is important,” she said.

Dr. Barlow, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, outlined the case for greater attention to UEDVT during “Controversies in Anticoagu-lation and Thrombosis. “UEDVTs make up 1% to 4% of all DVTs in the U.S., and nearly 80% of UEDVT cases are provoked.

Much of the rise in—and controversy—UEDVT is due to the increased use of in-dwelling catheters, primarily how long to leave the catheter in place and when to remove it. “Judicious use of catheters is necessary. You should leave it in, if you need it,” Dr. Barlow said, adding that hospitalists should weigh the benefits and risks of PICC lines.

Some of Dr. Barlow’s key take-home points:

- Treat UEDVT seriously;

- Understand there is a higher rate of PE than previously thought;

- Insert central-vein catheters judiciously, and keep them in if you still need them;

- Manage the duration of therapy parallel to that of lower extremity DVT; and

- Routine thrombolytics use isn’t indicated at this time. HM10

ELIZABETH BARLOW, MD, MPP, wants all hospitalists to know that upper-extremity DVT (UEDVT) is on the rise. Although most think of it “as a lesser entity,” Dr. Barlow told a jam-packed clinical-track session at HM10 the data show a higher rate of pulmonary em-bolism [PE] occurrence in UEDVT than was first thought. “So I think treating it seriously is important,” she said.

Dr. Barlow, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, outlined the case for greater attention to UEDVT during “Controversies in Anticoagu-lation and Thrombosis. “UEDVTs make up 1% to 4% of all DVTs in the U.S., and nearly 80% of UEDVT cases are provoked.

Much of the rise in—and controversy—UEDVT is due to the increased use of in-dwelling catheters, primarily how long to leave the catheter in place and when to remove it. “Judicious use of catheters is necessary. You should leave it in, if you need it,” Dr. Barlow said, adding that hospitalists should weigh the benefits and risks of PICC lines.

Some of Dr. Barlow’s key take-home points:

- Treat UEDVT seriously;

- Understand there is a higher rate of PE than previously thought;

- Insert central-vein catheters judiciously, and keep them in if you still need them;

- Manage the duration of therapy parallel to that of lower extremity DVT; and

- Routine thrombolytics use isn’t indicated at this time. HM10

What Is the Best Therapy for Acute Hepatic Encephalopathy?

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

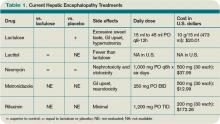

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.

Pediatric In the Literature

Clinical question: What is the incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis?

Background: Apnea is a known and reported complication of RSV infection in infants. In clinical practice, this relationship could be the basis for admission despite a lack of symptoms that would otherwise necessitate hospitalization. The exact nature of this association remains unclear, specifically with respect to incidence and risk factors for apnea.

Study design: Systematic chart review.

Synopsis: A literature search was conducted using a combination of the terms “apnea” (or “apnoea”), “bronchiolitis,” “respiratory syncytial virus” and/or “lower respiratory tract infection.” Studies were included if they reported apnea rates for a consecutive cohort of hospitalized infants. Thirteen studies involving 5,575 patients were reviewed.

Rates of apnea ranged from 1.2% to 23.8%. Infants of younger, postconceptional age (≤44 weeks) and pre-term infants were at greater risk for apnea. Term infants without serious underlying illness appeared to have a <1% risk of apnea, based on the most recent studies.

A consistent finding of this review was the heterogeneity of the data in the included studies. Definitions of apnea varied, were broad, and included subjective criteria. Age stratification was infrequent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were variable with respect to age cutoffs and relevant comorbidities. Future research will need to carefully delineate all of these potential confounding variables.

Bottom line: While rates of apnea in RSV bronchiolitis are difficult to quantify, there appears to be an association with younger, postconceptional age and pre-term birth.

Citation: Ralston S, Hill V. Incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):728-733.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis?

Background: Apnea is a known and reported complication of RSV infection in infants. In clinical practice, this relationship could be the basis for admission despite a lack of symptoms that would otherwise necessitate hospitalization. The exact nature of this association remains unclear, specifically with respect to incidence and risk factors for apnea.

Study design: Systematic chart review.

Synopsis: A literature search was conducted using a combination of the terms “apnea” (or “apnoea”), “bronchiolitis,” “respiratory syncytial virus” and/or “lower respiratory tract infection.” Studies were included if they reported apnea rates for a consecutive cohort of hospitalized infants. Thirteen studies involving 5,575 patients were reviewed.

Rates of apnea ranged from 1.2% to 23.8%. Infants of younger, postconceptional age (≤44 weeks) and pre-term infants were at greater risk for apnea. Term infants without serious underlying illness appeared to have a <1% risk of apnea, based on the most recent studies.

A consistent finding of this review was the heterogeneity of the data in the included studies. Definitions of apnea varied, were broad, and included subjective criteria. Age stratification was infrequent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were variable with respect to age cutoffs and relevant comorbidities. Future research will need to carefully delineate all of these potential confounding variables.

Bottom line: While rates of apnea in RSV bronchiolitis are difficult to quantify, there appears to be an association with younger, postconceptional age and pre-term birth.

Citation: Ralston S, Hill V. Incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):728-733.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis?

Background: Apnea is a known and reported complication of RSV infection in infants. In clinical practice, this relationship could be the basis for admission despite a lack of symptoms that would otherwise necessitate hospitalization. The exact nature of this association remains unclear, specifically with respect to incidence and risk factors for apnea.

Study design: Systematic chart review.

Synopsis: A literature search was conducted using a combination of the terms “apnea” (or “apnoea”), “bronchiolitis,” “respiratory syncytial virus” and/or “lower respiratory tract infection.” Studies were included if they reported apnea rates for a consecutive cohort of hospitalized infants. Thirteen studies involving 5,575 patients were reviewed.

Rates of apnea ranged from 1.2% to 23.8%. Infants of younger, postconceptional age (≤44 weeks) and pre-term infants were at greater risk for apnea. Term infants without serious underlying illness appeared to have a <1% risk of apnea, based on the most recent studies.

A consistent finding of this review was the heterogeneity of the data in the included studies. Definitions of apnea varied, were broad, and included subjective criteria. Age stratification was infrequent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were variable with respect to age cutoffs and relevant comorbidities. Future research will need to carefully delineate all of these potential confounding variables.

Bottom line: While rates of apnea in RSV bronchiolitis are difficult to quantify, there appears to be an association with younger, postconceptional age and pre-term birth.

Citation: Ralston S, Hill V. Incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):728-733.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

In the Literature

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Predictors of readmission for patients with CAP.

- High-dose statins vs. lipid-lowering therapy combinations

- Catheter retention and risks of reinfection in patients with coagulase-negative staph

- Stenting vs. medical management of renal-artery stenosis

- Dabigatran for VTE

- Surgical mask vs. N95 respirator for influenza prevention

- Hospitalization and the risk of long-term cognitive decline

- Maturation of rapid-response teams and outcomes

Commonly Available Clinical Variables Predict 30-Day Readmissions for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: What are the risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: CAP is a common admission diagnosis associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization. While prior data suggested that patients who survive a hospitalization for CAP are particularly vulnerable to readmission, few studies have examined the risk factors for readmission in this population.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: A 400-bed teaching hospital in northern Spain.

Synopsis: From 2003 to 2005, this study consecutively enrolled 1,117 patients who were discharged after hospitalization for CAP. Eighty-one patients (7.2%) were readmitted within 30 days of discharge; 29 (35.8%) of these patients were rehospitalized for pneumonia-related causes.

Variables associated with pneumonia-related rehospitalization were treatment failure (HR 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2-6.8) and one or more instability factors at hospital discharge—for example, vital-sign abnormalities or inability to take food or medications by mouth (HR 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.2). Variables associated with readmission unrelated to pneumonia were age greater than 65 years (HR 4.5; 95% CI, 1.4-14.7), Charlson comorbidity index greater than 2 (HR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.0-3.4), and decompensated comorbidities during index hospitalization.

Patients with at least two of the above risk factors were at a significantly higher risk for 30-day hospital readmission (HR 3.37; 95% CI, 2.08-5.46).

Bottom line: The risk factors for readmission after hospitalization for CAP differed between the groups with readmissions related to pneumonia versus other causes. Patients at high risk for readmission can be identified using easily available clinical variables.

Citation: Capelastegui A, España Yandiola PP, Quintana JM, et al. Predictors of short-term rehospitalization following discharge of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136(4): 1079-1085.

Combinations of Lipid-Lowering Agents No More Effective than High-Dose Statin Monotherapy

Clinical question: Is high-dose statin monotherapy better than combinations of lipid-lowering agents for dyslipidemia in adults at high risk for coronary artery disease?

Background: While current guidelines support the benefits of aggressive lipid targets, there is little to guide physicians as to the optimal strategy for attaining target lipid levels.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: North America, Europe, and Asia.

Synopsis: Very-low-strength evidence showed that statin-ezetimibe (two trials; N=439) and statin-fibrate (one trial; N=166) combinations did not reduce mortality more than high-dose statin monotherapy. No trial data were found comparing the effect of these two strategies on secondary endpoints, including myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization.

Two trials (N=295) suggested lower-target lipid levels were more often achieved with statin-ezetimibe combination therapy than with high-dose statin monotherapy (OR 7.21; 95% CI, 4.30-12.08).

Limitations of this systematic review include the small number of studies directly comparing the two strategies, the short duration of most of the studies included, the focus on surrogate outcomes, and the heterogeneity of the study populations’ risk for coronary artery disease. Few studies were available comparing combination therapies other than statin-ezetimibe.

Bottom line: Limited evidence suggests that the combination of a statin with another lipid-lowering agent does not improve clinical outcomes when compared with high-dose statin monotherapy. Low-quality evidence suggests that lower-target lipid levels were more often reached with statin-ezetimibe combination therapy than with high-dose statin monotherapy.

Citation: Sharma M, Ansari MT, Abou-Setta AM, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of combination therapy and monotherapy for dyslipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(9):622-630.

Catheter Retention in Catheter-Related Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcal Bacteremia Is a Significant Risk Factor for Recurrent Infection

Clinical question: Should central venous catheters (CVC) be removed in patients with coagulase-negative staphylococcal catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI)?

Background: Current guidelines for the management of coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI do not recommend routine removal of the CVC, but are based on studies that did not use a strict definition of coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI. Additionally, the studies did not look explicitly at the risk of recurrent infection.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: The study retrospectively evaluated 188 patients with coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI. Immediate resolution of the infection was not influenced by the management of the CVC (retention vs. removal or exchange). However, using the multiple logistic regression technique, patients with catheter retention were found to be 6.6 times (95% CI, 1.8-23.9 times) more likely to have recurrence compared with those patients whose catheter was removed or exchanged.

Bottom line: While CVC management does not appear to have an impact on the acute resolution of infection, catheter retention is a significant risk factor for recurrent bacteremia.

Citation: Raad I, Kassar R, Ghannam D, Chaftari AM, Hachem R, Jiang Y. Management of the catheter in documented catheter-related coagulase-negative staphylococcal bacteremia: remove or retain? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1187-1194.

Revascularization Offers No Benefit over Medical Therapy for Renal-Artery Stenosis

Clinical question: Does revascularization plus medical therapy compared with medical therapy alone improve outcomes in patients with renal-artery stenosis?

Background: Renal-artery stenosis is associated with significant hypertension and renal dysfunction. Revascularization for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis can improve artery patency, but it remains unclear if it provides clinical benefit in terms of preserving renal function or reducing overall mortality.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-seven outpatient sites in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.

Synopsis: The study randomized 806 patients with renal-artery stenosis to receive either medical therapy alone (N=403) or medical management plus endovascular revascularization (N=403).

The majority of the patients who underwent revascularization (95%) received a stent.

The data show no significant difference between the two groups in the rate of progression of renal dysfunction, systolic blood pressure, rates of adverse renal and cardiovascular events, and overall survival. Of the 359 patients who underwent revascularization, 23 (6%) experienced serious complications from the procedure, including two deaths and three cases of amputated toes or limbs.

The primary limitation of this trial is the population studied. The trial only included subjects for whom revascularization offered uncertain clinical benefits, according to their doctor. Those subjects for whom revascularization offered certain clinical benefits, as noted by their primary-care physician (PCP), were excluded from the study. Examples include patients presenting with rapidly progressive renal dysfunction or pulmonary edema thought to be a result of renal-artery stenosis.

Bottom line: Revascularization provides no benefit to most patients with renal-artery stenosis, and is associated with some risk.

Citation: ASTRAL investigators, Wheatley K, Ives N, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Eng J Med. 2009;361(20):1953-1962.

Dabigatran as Effective as Warfarin in Treatment of Acute VTE

Clinical question: Is dabigatran a safe and effective alternative to warfarin for treatment of acute VTE?

Background: Parenteral anticoagulation followed by warfarin is the standard of care for acute VTE. Warfarin requires frequent monitoring and has numerous drug and food interactions. Dabigatran, which the FDA has yet to approve for use in the U.S., is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor that does not require laboratory monitoring. The role of dabigatran in acute VTE has not been evaluated.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two hundred twenty-two clinical centers in 29 countries.

Synopsis: This study randomized 2,564 patients with documented VTE (either DVT or pulmonary embolism [PE]) to receive dabigatran 150mg twice daily or warfarin after at least five days of a parenteral anticoagulant. Warfarin was dose-adjusted to an INR goal of 2.0-3.0. The primary outcome was incidence of recurrent VTE and related deaths at six months.

A total of 2.4% of patients assigned to dabigatran and 2.1% of patients assigned to warfarin had recurrent VTE (HR 1.10; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5), which met criteria for noninferiority. Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% of patients assigned to dabigatran and 1.9% assigned to warfarin (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.45-1.48). There was no difference between groups in overall adverse effects. Discontinuation due to adverse events was 9% with dabigatran compared with 6.8% with warfarin (P=0.05). Dyspepsia was more common with dabigatran (P<0.001).

Bottom line: Following parenteral anticoagulation, dabigatran is a safe and effective alternative to warfarin for the treatment of acute VTE and does not require therapeutic monitoring.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2342-2352.

Surgical Masks as Effective as N95 Respirators for Preventing Influenza

Clinical question: How effective are surgical masks compared with N95 respirators in protecting healthcare workers against influenza?

Background: Evidence surrounding the effectiveness of the surgical mask compared with the N95 respirator for protecting healthcare workers against influenza is sparse.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Eight hospitals in Ontario.

Synopsis: The study looked at 446 nurses working in EDs, medical units, and pediatric units randomized to use either a fit-tested N95 respirator or a surgical mask when caring for patients with febrile respiratory illness during the 2008-2009 flu season. The primary outcome measured was laboratory-confirmed influenza. Only a minority of the study participants (30% in the surgical mask group; 28% in the respirator group) received the influenza vaccine during the study year.

Influenza infection occurred with similar incidence in both the surgical-mask and N95 respirator groups (23.6% vs. 22.9%). A two-week audit period demonstrated solid adherence to the assigned respiratory protection device in both groups (11 out of 11 nurses were compliant in the surgical-mask group; six out of seven nurses were compliant in the respirator group).

The major limitation of this study is that it cannot be extrapolated to other settings where there is a high risk for aerosolization, such as intubation or bronchoscopy, where N95 respirators may be more effective than surgical masks.

Bottom line: Surgical masks are as effective as fit-tested N95 respirators in protecting healthcare workers against influenza in most settings.

Citation: Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs. N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302 (17):1865-1871.

Neither Major Illness Nor Noncardiac Surgery Associated with Long-Term Cognitive Decline in Older Patients

Clinical question: Is there a measurable and lasting cognitive decline in older adults following noncardiac surgery or major illness?

Background: Despite limited evidence, there is some concern that elderly patients are susceptible to significant, long-term deterioration in mental function following surgery or a major illness. Prior studies often have been limited by lack of information about the trajectory of surgical patients’ cognitive status before surgery and lack of relevant control groups.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Single outpatient research center.

Synopsis: The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at the University of Washington in St. Louis continually enrolls research subjects without regard to their baseline cognitive function and provides annual assessment of cognitive functioning.

From the ADRC database, 575 eligible research participants were identified. Of these, 361 had very mild or mild dementia at enrollment, and 214 had no dementia. Participants were then categorized into three groups: those who had undergone noncardiac surgery (N=180); those who had been admitted to the hospital with a major illness (N=119); and those who had experienced neither surgery nor major illness (N=276).

Cognitive trajectory did not differ between the three groups, although participants with baseline dementia declined more rapidly than participants without dementia. Although 23% of patients without dementia developed detectable evidence of dementia during the study period, this outcome was not more common following surgery or major illness.

As participants were assessed annually, this study does not address the issue of post-operative delirium or early cognitive impairment following surgery.

Bottom line: There is no evidence for a long-term effect on cognitive function independently attributable to noncardiac surgery or major illness.

Citation: Avidan MS, Searleman AC, Storandt M, et al. Long-term cognitive decline in older subjects was not attributable to noncardiac surgery or major illness. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(5):964-970.

Rapid-Response System Maturation Decreases Delays in Emergency Team Activation

Clinical question: Does the maturation of a rapid-response system (RRS) improve performance by decreasing delays in medical emergency team (MET) activation?

Background: RRSs have been widely embraced as a possible means to reduce inpatient cardiopulmonary arrests and unplanned ICU admissions. Assessment of RRSs early in their implementation might underestimate their long-term efficacy. Whether the use and performance of RRSs improve as they mature is currently unknown.

Study design: Observational, cohort study.

Setting: Single tertiary-care hospital.

Synopsis: A recent cohort of 200 patients receiving MET review was prospectively compared with a control cohort of 400 patients receiving an MET review five years earlier, at the start of RRS implementation. Information obtained on the two cohorts included demographics, timing of MET activation in relation to the first documented MET review criterion (activation delay), and patient outcomes.

Fewer patients in the recent cohort had delayed MET activation (22.0% vs. 40.3%). The recent cohort also was independently associated with a decreased risk of delayed activation (OR 0.45; 95% C.I., 0.30-0.67) and ICU admission (OR 0.5; 95% C.I., 0.32-0.78). Delayed MET activation independently was associated with greater risk of unplanned ICU admission (OR 1.79; 95% C.I., 1.33-2.93) and hospital mortality (OR 2.18; 95% C.I., 1.42-3.33).

The study is limited by its observational nature, and thus the association between greater delay and unfavorable outcomes should not infer causality.

Bottom line: The maturation of a RRS decreases delays in MET activation. RRSs might need to mature before their full impact is felt.

Citation: Calzavacca P, Licari E, Tee A, et al. The impact of Rapid Response System on delayed emergency team activation patient characteristics and outcomes—a follow-up study. Resuscitation. 2010;81(1):31-35. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Predictors of readmission for patients with CAP.

- High-dose statins vs. lipid-lowering therapy combinations

- Catheter retention and risks of reinfection in patients with coagulase-negative staph

- Stenting vs. medical management of renal-artery stenosis

- Dabigatran for VTE

- Surgical mask vs. N95 respirator for influenza prevention

- Hospitalization and the risk of long-term cognitive decline

- Maturation of rapid-response teams and outcomes

Commonly Available Clinical Variables Predict 30-Day Readmissions for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: What are the risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: CAP is a common admission diagnosis associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization. While prior data suggested that patients who survive a hospitalization for CAP are particularly vulnerable to readmission, few studies have examined the risk factors for readmission in this population.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: A 400-bed teaching hospital in northern Spain.

Synopsis: From 2003 to 2005, this study consecutively enrolled 1,117 patients who were discharged after hospitalization for CAP. Eighty-one patients (7.2%) were readmitted within 30 days of discharge; 29 (35.8%) of these patients were rehospitalized for pneumonia-related causes.

Variables associated with pneumonia-related rehospitalization were treatment failure (HR 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2-6.8) and one or more instability factors at hospital discharge—for example, vital-sign abnormalities or inability to take food or medications by mouth (HR 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.2). Variables associated with readmission unrelated to pneumonia were age greater than 65 years (HR 4.5; 95% CI, 1.4-14.7), Charlson comorbidity index greater than 2 (HR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.0-3.4), and decompensated comorbidities during index hospitalization.

Patients with at least two of the above risk factors were at a significantly higher risk for 30-day hospital readmission (HR 3.37; 95% CI, 2.08-5.46).

Bottom line: The risk factors for readmission after hospitalization for CAP differed between the groups with readmissions related to pneumonia versus other causes. Patients at high risk for readmission can be identified using easily available clinical variables.

Citation: Capelastegui A, España Yandiola PP, Quintana JM, et al. Predictors of short-term rehospitalization following discharge of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136(4): 1079-1085.

Combinations of Lipid-Lowering Agents No More Effective than High-Dose Statin Monotherapy

Clinical question: Is high-dose statin monotherapy better than combinations of lipid-lowering agents for dyslipidemia in adults at high risk for coronary artery disease?

Background: While current guidelines support the benefits of aggressive lipid targets, there is little to guide physicians as to the optimal strategy for attaining target lipid levels.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: North America, Europe, and Asia.

Synopsis: Very-low-strength evidence showed that statin-ezetimibe (two trials; N=439) and statin-fibrate (one trial; N=166) combinations did not reduce mortality more than high-dose statin monotherapy. No trial data were found comparing the effect of these two strategies on secondary endpoints, including myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization.

Two trials (N=295) suggested lower-target lipid levels were more often achieved with statin-ezetimibe combination therapy than with high-dose statin monotherapy (OR 7.21; 95% CI, 4.30-12.08).

Limitations of this systematic review include the small number of studies directly comparing the two strategies, the short duration of most of the studies included, the focus on surrogate outcomes, and the heterogeneity of the study populations’ risk for coronary artery disease. Few studies were available comparing combination therapies other than statin-ezetimibe.

Bottom line: Limited evidence suggests that the combination of a statin with another lipid-lowering agent does not improve clinical outcomes when compared with high-dose statin monotherapy. Low-quality evidence suggests that lower-target lipid levels were more often reached with statin-ezetimibe combination therapy than with high-dose statin monotherapy.

Citation: Sharma M, Ansari MT, Abou-Setta AM, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of combination therapy and monotherapy for dyslipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(9):622-630.

Catheter Retention in Catheter-Related Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcal Bacteremia Is a Significant Risk Factor for Recurrent Infection

Clinical question: Should central venous catheters (CVC) be removed in patients with coagulase-negative staphylococcal catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI)?

Background: Current guidelines for the management of coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI do not recommend routine removal of the CVC, but are based on studies that did not use a strict definition of coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI. Additionally, the studies did not look explicitly at the risk of recurrent infection.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: The study retrospectively evaluated 188 patients with coagulase-negative staphylococcal CRBSI. Immediate resolution of the infection was not influenced by the management of the CVC (retention vs. removal or exchange). However, using the multiple logistic regression technique, patients with catheter retention were found to be 6.6 times (95% CI, 1.8-23.9 times) more likely to have recurrence compared with those patients whose catheter was removed or exchanged.

Bottom line: While CVC management does not appear to have an impact on the acute resolution of infection, catheter retention is a significant risk factor for recurrent bacteremia.

Citation: Raad I, Kassar R, Ghannam D, Chaftari AM, Hachem R, Jiang Y. Management of the catheter in documented catheter-related coagulase-negative staphylococcal bacteremia: remove or retain? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1187-1194.

Revascularization Offers No Benefit over Medical Therapy for Renal-Artery Stenosis

Clinical question: Does revascularization plus medical therapy compared with medical therapy alone improve outcomes in patients with renal-artery stenosis?

Background: Renal-artery stenosis is associated with significant hypertension and renal dysfunction. Revascularization for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis can improve artery patency, but it remains unclear if it provides clinical benefit in terms of preserving renal function or reducing overall mortality.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-seven outpatient sites in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.

Synopsis: The study randomized 806 patients with renal-artery stenosis to receive either medical therapy alone (N=403) or medical management plus endovascular revascularization (N=403).

The majority of the patients who underwent revascularization (95%) received a stent.

The data show no significant difference between the two groups in the rate of progression of renal dysfunction, systolic blood pressure, rates of adverse renal and cardiovascular events, and overall survival. Of the 359 patients who underwent revascularization, 23 (6%) experienced serious complications from the procedure, including two deaths and three cases of amputated toes or limbs.

The primary limitation of this trial is the population studied. The trial only included subjects for whom revascularization offered uncertain clinical benefits, according to their doctor. Those subjects for whom revascularization offered certain clinical benefits, as noted by their primary-care physician (PCP), were excluded from the study. Examples include patients presenting with rapidly progressive renal dysfunction or pulmonary edema thought to be a result of renal-artery stenosis.

Bottom line: Revascularization provides no benefit to most patients with renal-artery stenosis, and is associated with some risk.

Citation: ASTRAL investigators, Wheatley K, Ives N, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Eng J Med. 2009;361(20):1953-1962.

Dabigatran as Effective as Warfarin in Treatment of Acute VTE

Clinical question: Is dabigatran a safe and effective alternative to warfarin for treatment of acute VTE?

Background: Parenteral anticoagulation followed by warfarin is the standard of care for acute VTE. Warfarin requires frequent monitoring and has numerous drug and food interactions. Dabigatran, which the FDA has yet to approve for use in the U.S., is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor that does not require laboratory monitoring. The role of dabigatran in acute VTE has not been evaluated.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two hundred twenty-two clinical centers in 29 countries.

Synopsis: This study randomized 2,564 patients with documented VTE (either DVT or pulmonary embolism [PE]) to receive dabigatran 150mg twice daily or warfarin after at least five days of a parenteral anticoagulant. Warfarin was dose-adjusted to an INR goal of 2.0-3.0. The primary outcome was incidence of recurrent VTE and related deaths at six months.

A total of 2.4% of patients assigned to dabigatran and 2.1% of patients assigned to warfarin had recurrent VTE (HR 1.10; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5), which met criteria for noninferiority. Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% of patients assigned to dabigatran and 1.9% assigned to warfarin (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.45-1.48). There was no difference between groups in overall adverse effects. Discontinuation due to adverse events was 9% with dabigatran compared with 6.8% with warfarin (P=0.05). Dyspepsia was more common with dabigatran (P<0.001).

Bottom line: Following parenteral anticoagulation, dabigatran is a safe and effective alternative to warfarin for the treatment of acute VTE and does not require therapeutic monitoring.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2342-2352.

Surgical Masks as Effective as N95 Respirators for Preventing Influenza

Clinical question: How effective are surgical masks compared with N95 respirators in protecting healthcare workers against influenza?

Background: Evidence surrounding the effectiveness of the surgical mask compared with the N95 respirator for protecting healthcare workers against influenza is sparse.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Eight hospitals in Ontario.

Synopsis: The study looked at 446 nurses working in EDs, medical units, and pediatric units randomized to use either a fit-tested N95 respirator or a surgical mask when caring for patients with febrile respiratory illness during the 2008-2009 flu season. The primary outcome measured was laboratory-confirmed influenza. Only a minority of the study participants (30% in the surgical mask group; 28% in the respirator group) received the influenza vaccine during the study year.

Influenza infection occurred with similar incidence in both the surgical-mask and N95 respirator groups (23.6% vs. 22.9%). A two-week audit period demonstrated solid adherence to the assigned respiratory protection device in both groups (11 out of 11 nurses were compliant in the surgical-mask group; six out of seven nurses were compliant in the respirator group).

The major limitation of this study is that it cannot be extrapolated to other settings where there is a high risk for aerosolization, such as intubation or bronchoscopy, where N95 respirators may be more effective than surgical masks.

Bottom line: Surgical masks are as effective as fit-tested N95 respirators in protecting healthcare workers against influenza in most settings.

Citation: Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs. N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302 (17):1865-1871.

Neither Major Illness Nor Noncardiac Surgery Associated with Long-Term Cognitive Decline in Older Patients

Clinical question: Is there a measurable and lasting cognitive decline in older adults following noncardiac surgery or major illness?

Background: Despite limited evidence, there is some concern that elderly patients are susceptible to significant, long-term deterioration in mental function following surgery or a major illness. Prior studies often have been limited by lack of information about the trajectory of surgical patients’ cognitive status before surgery and lack of relevant control groups.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Single outpatient research center.

Synopsis: The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at the University of Washington in St. Louis continually enrolls research subjects without regard to their baseline cognitive function and provides annual assessment of cognitive functioning.

From the ADRC database, 575 eligible research participants were identified. Of these, 361 had very mild or mild dementia at enrollment, and 214 had no dementia. Participants were then categorized into three groups: those who had undergone noncardiac surgery (N=180); those who had been admitted to the hospital with a major illness (N=119); and those who had experienced neither surgery nor major illness (N=276).

Cognitive trajectory did not differ between the three groups, although participants with baseline dementia declined more rapidly than participants without dementia. Although 23% of patients without dementia developed detectable evidence of dementia during the study period, this outcome was not more common following surgery or major illness.

As participants were assessed annually, this study does not address the issue of post-operative delirium or early cognitive impairment following surgery.

Bottom line: There is no evidence for a long-term effect on cognitive function independently attributable to noncardiac surgery or major illness.

Citation: Avidan MS, Searleman AC, Storandt M, et al. Long-term cognitive decline in older subjects was not attributable to noncardiac surgery or major illness. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(5):964-970.

Rapid-Response System Maturation Decreases Delays in Emergency Team Activation

Clinical question: Does the maturation of a rapid-response system (RRS) improve performance by decreasing delays in medical emergency team (MET) activation?

Background: RRSs have been widely embraced as a possible means to reduce inpatient cardiopulmonary arrests and unplanned ICU admissions. Assessment of RRSs early in their implementation might underestimate their long-term efficacy. Whether the use and performance of RRSs improve as they mature is currently unknown.