User login

The Year Ahead

Rising pressure to contain healthcare costs, increasing demands for safety and quality improvement, more focus on institutional accountability: In 2010, healthcare experts expect several dominant themes to continue converging and moving hospitalists even more to the center of key policy debates.

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director of the Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care and director of the Quality and Safety Research Group at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, sees three big themes moving to the fore. One is a greater focus on outcome measurements and accountability for performance, and he expects both carrots and sticks to be wielded. “So, both payment reform and social humiliation, or making things public,” Dr. Pronovost says. “Two, I see a lot more focus on measures that are population-based rather than hospital-based, so looking more at episodes of care.” The shift will force hospitalists to expand their purview beyond the hospital and, he says, partner more with community physicians to develop and monitor performance in such areas as transitions of care and general benchmarks of care.

Dr. Pronovost also expects “significant pressure on both the provider organization and individual clinician being paid less for what they do.” Finding ways to minimize costs will be a priority as payors increase scrutiny on expenses like unnecessary hospital readmissions. But hospitalists, he says, are better positioned than many other physicians to play a key role in the drive toward efficiency while also improving healthcare quality and safety. “I think hospitalists’ roles are going to go up dramatically,” Dr. Pronovost adds, “and I hope the field responds by making sure they put out people who have the skills to lead.”

End-of-Life Issues

Nancy Berlinger, PhD, deputy director and research scholar at The Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., cites end-of-life care as another theme likely to gain traction in 2010. As project director of the center’s revised ethical guidelines for end-of-life care, Dr. Berlinger notes how often clinicians in her working group have invoked the hospitalist profession. It’s no accident. “Hospitalists are increasingly associated with the care of patients on Medicare,” she says, adding Medicare beneficiaries are far more likely to be nearing the end of life.

Demographics suggest that connection will continue to grow in 2010 and beyond. Dr. Berlinger points to a 2009 New England Journal of Medicine study showing that the odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient receiving care from a hospitalist increased at a brisk 29.2% annual clip from 1997 through 2006.1 And while the U.S. faces a shortage of geriatricians, HM is growing rapidly as a medical profession. “By default, whether or not hospitalists self-identify as caring for older Americans,” Dr. Berlinger says, “this is their area of practical specialization.”

With that specialization comes added responsibility to assist with advanced-care planning and helping patients to document their wishes. Similarly, she says, it means acknowledging that these patients are more likely to have comorbid conditions and identify with goals of care. “I don’t think there’s any way around this,” she says. “Medicare and hospitalists, whether by accident or design, are increasingly joined at the hip. That is something that hospitalists, as a profession, will always need to keep their eye on.”

A parallel trend is that other doctors increasingly view hospitalists as hospital specialists. “The hospitalist’s responsibilities are not just in terms of the patients they care for, but also in terms of the institution itself,” Dr. Berlinger says. Non-staff physicians, for example, expect hospitalists to know how a hospital’s in-patient care system works. Practically speaking, as electronic medical records (EMR) become more commonplace, hospitalists will be increasingly relied upon to understand a hospital’s information technology.

—Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director, Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

New Economy, New Hospital Landscape

Douglas Wood, MD, chair of the Division of Health Care Policy and Research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., points to language in the federal healthcare reform legislation as evidence that hospitals and hospitalists will need to be in sync in other ways to avoid future penalties. One provision, for example, would increase the penalties for hospital-acquired infections. Other language seeks to reduce unnecessary readmissions.

Likewise, Dr. Wood says, addressing geographical variations in healthcare payments driven largely by unnecessary overutilization—including excessive use of ICU care, in-patient care, imaging, and specialist services—might mean asking hospitalists to take on more aspects of patient care.

Meanwhile, increased interest in demonstration projects that might achieve savings (e.g., accountable care organizations and bundled payments) suggests that proactive hospitals should again look to hospitalists. The flurry of new proposals won’t fundamentally change hospitalists’ responsibilities to provide effective and efficient care, “but it will put more emphasis on what they’re doing,” Dr. Wood says, “to the degree that hospitalists could take a lead in demonstrating how you can provide better outcomes at a lower overall utilization of resources.”

Regardless of how slowly or quickly these initiatives proceed at the national level, he says, hospitalists should be mindful that several states are well ahead of the curve and are likely to be more aggressive in instituting policy changes.

The Bottom Line

If there’s a single, overriding theme for 2010, Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, FHM, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says it might be that of dealing with the unknown. Squeezing healthcare costs and more tightly regulating inflation will have a greater effect on a hospital’s bottom line and thus impact what’s required of hospitalists. Even so, the profession will have to wait and see whether and how various proposals are codified and implemented. “We don’t know exactly what things are going to look like,” he says.

Nor is there a good sense of how new standards for transparency, quality, and accountability might be measured. “While people want more measurement and they want more report-card-type information, the data that we can acquire right now and how we analyze that data are still fairly primitive,” Dr. Flansbaum says. Even current benchmarks are lacking in how to determine who’s doing a good job and who isn’t, he says.

One big question that must be answered, then: Are we even looking at the right measurements? “Or, do the right measurements exist, or do we have the databases, the registries, the sources, to make the decisions we need to make?” he says.

Any new proposals will require another round of such questions and filling-in of blanks to add workable details to vague and potentially confusing language.

“I think we know that change is afoot, and most smart hospitalists know that the system needs to run leaner,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “But how each one of us is going to function in our hospital, and the kinds of demands that will be placed on us, and what we’re going to need to do with the doctors in the community and the other nonphysician colleagues that we work with, is all really unknown.” TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11): 1102-1112.

Image Source: PAGADESIGN, OVERSNAP/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Rising pressure to contain healthcare costs, increasing demands for safety and quality improvement, more focus on institutional accountability: In 2010, healthcare experts expect several dominant themes to continue converging and moving hospitalists even more to the center of key policy debates.

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director of the Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care and director of the Quality and Safety Research Group at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, sees three big themes moving to the fore. One is a greater focus on outcome measurements and accountability for performance, and he expects both carrots and sticks to be wielded. “So, both payment reform and social humiliation, or making things public,” Dr. Pronovost says. “Two, I see a lot more focus on measures that are population-based rather than hospital-based, so looking more at episodes of care.” The shift will force hospitalists to expand their purview beyond the hospital and, he says, partner more with community physicians to develop and monitor performance in such areas as transitions of care and general benchmarks of care.

Dr. Pronovost also expects “significant pressure on both the provider organization and individual clinician being paid less for what they do.” Finding ways to minimize costs will be a priority as payors increase scrutiny on expenses like unnecessary hospital readmissions. But hospitalists, he says, are better positioned than many other physicians to play a key role in the drive toward efficiency while also improving healthcare quality and safety. “I think hospitalists’ roles are going to go up dramatically,” Dr. Pronovost adds, “and I hope the field responds by making sure they put out people who have the skills to lead.”

End-of-Life Issues

Nancy Berlinger, PhD, deputy director and research scholar at The Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., cites end-of-life care as another theme likely to gain traction in 2010. As project director of the center’s revised ethical guidelines for end-of-life care, Dr. Berlinger notes how often clinicians in her working group have invoked the hospitalist profession. It’s no accident. “Hospitalists are increasingly associated with the care of patients on Medicare,” she says, adding Medicare beneficiaries are far more likely to be nearing the end of life.

Demographics suggest that connection will continue to grow in 2010 and beyond. Dr. Berlinger points to a 2009 New England Journal of Medicine study showing that the odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient receiving care from a hospitalist increased at a brisk 29.2% annual clip from 1997 through 2006.1 And while the U.S. faces a shortage of geriatricians, HM is growing rapidly as a medical profession. “By default, whether or not hospitalists self-identify as caring for older Americans,” Dr. Berlinger says, “this is their area of practical specialization.”

With that specialization comes added responsibility to assist with advanced-care planning and helping patients to document their wishes. Similarly, she says, it means acknowledging that these patients are more likely to have comorbid conditions and identify with goals of care. “I don’t think there’s any way around this,” she says. “Medicare and hospitalists, whether by accident or design, are increasingly joined at the hip. That is something that hospitalists, as a profession, will always need to keep their eye on.”

A parallel trend is that other doctors increasingly view hospitalists as hospital specialists. “The hospitalist’s responsibilities are not just in terms of the patients they care for, but also in terms of the institution itself,” Dr. Berlinger says. Non-staff physicians, for example, expect hospitalists to know how a hospital’s in-patient care system works. Practically speaking, as electronic medical records (EMR) become more commonplace, hospitalists will be increasingly relied upon to understand a hospital’s information technology.

—Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director, Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

New Economy, New Hospital Landscape

Douglas Wood, MD, chair of the Division of Health Care Policy and Research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., points to language in the federal healthcare reform legislation as evidence that hospitals and hospitalists will need to be in sync in other ways to avoid future penalties. One provision, for example, would increase the penalties for hospital-acquired infections. Other language seeks to reduce unnecessary readmissions.

Likewise, Dr. Wood says, addressing geographical variations in healthcare payments driven largely by unnecessary overutilization—including excessive use of ICU care, in-patient care, imaging, and specialist services—might mean asking hospitalists to take on more aspects of patient care.

Meanwhile, increased interest in demonstration projects that might achieve savings (e.g., accountable care organizations and bundled payments) suggests that proactive hospitals should again look to hospitalists. The flurry of new proposals won’t fundamentally change hospitalists’ responsibilities to provide effective and efficient care, “but it will put more emphasis on what they’re doing,” Dr. Wood says, “to the degree that hospitalists could take a lead in demonstrating how you can provide better outcomes at a lower overall utilization of resources.”

Regardless of how slowly or quickly these initiatives proceed at the national level, he says, hospitalists should be mindful that several states are well ahead of the curve and are likely to be more aggressive in instituting policy changes.

The Bottom Line

If there’s a single, overriding theme for 2010, Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, FHM, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says it might be that of dealing with the unknown. Squeezing healthcare costs and more tightly regulating inflation will have a greater effect on a hospital’s bottom line and thus impact what’s required of hospitalists. Even so, the profession will have to wait and see whether and how various proposals are codified and implemented. “We don’t know exactly what things are going to look like,” he says.

Nor is there a good sense of how new standards for transparency, quality, and accountability might be measured. “While people want more measurement and they want more report-card-type information, the data that we can acquire right now and how we analyze that data are still fairly primitive,” Dr. Flansbaum says. Even current benchmarks are lacking in how to determine who’s doing a good job and who isn’t, he says.

One big question that must be answered, then: Are we even looking at the right measurements? “Or, do the right measurements exist, or do we have the databases, the registries, the sources, to make the decisions we need to make?” he says.

Any new proposals will require another round of such questions and filling-in of blanks to add workable details to vague and potentially confusing language.

“I think we know that change is afoot, and most smart hospitalists know that the system needs to run leaner,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “But how each one of us is going to function in our hospital, and the kinds of demands that will be placed on us, and what we’re going to need to do with the doctors in the community and the other nonphysician colleagues that we work with, is all really unknown.” TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11): 1102-1112.

Image Source: PAGADESIGN, OVERSNAP/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Rising pressure to contain healthcare costs, increasing demands for safety and quality improvement, more focus on institutional accountability: In 2010, healthcare experts expect several dominant themes to continue converging and moving hospitalists even more to the center of key policy debates.

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director of the Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care and director of the Quality and Safety Research Group at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, sees three big themes moving to the fore. One is a greater focus on outcome measurements and accountability for performance, and he expects both carrots and sticks to be wielded. “So, both payment reform and social humiliation, or making things public,” Dr. Pronovost says. “Two, I see a lot more focus on measures that are population-based rather than hospital-based, so looking more at episodes of care.” The shift will force hospitalists to expand their purview beyond the hospital and, he says, partner more with community physicians to develop and monitor performance in such areas as transitions of care and general benchmarks of care.

Dr. Pronovost also expects “significant pressure on both the provider organization and individual clinician being paid less for what they do.” Finding ways to minimize costs will be a priority as payors increase scrutiny on expenses like unnecessary hospital readmissions. But hospitalists, he says, are better positioned than many other physicians to play a key role in the drive toward efficiency while also improving healthcare quality and safety. “I think hospitalists’ roles are going to go up dramatically,” Dr. Pronovost adds, “and I hope the field responds by making sure they put out people who have the skills to lead.”

End-of-Life Issues

Nancy Berlinger, PhD, deputy director and research scholar at The Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., cites end-of-life care as another theme likely to gain traction in 2010. As project director of the center’s revised ethical guidelines for end-of-life care, Dr. Berlinger notes how often clinicians in her working group have invoked the hospitalist profession. It’s no accident. “Hospitalists are increasingly associated with the care of patients on Medicare,” she says, adding Medicare beneficiaries are far more likely to be nearing the end of life.

Demographics suggest that connection will continue to grow in 2010 and beyond. Dr. Berlinger points to a 2009 New England Journal of Medicine study showing that the odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient receiving care from a hospitalist increased at a brisk 29.2% annual clip from 1997 through 2006.1 And while the U.S. faces a shortage of geriatricians, HM is growing rapidly as a medical profession. “By default, whether or not hospitalists self-identify as caring for older Americans,” Dr. Berlinger says, “this is their area of practical specialization.”

With that specialization comes added responsibility to assist with advanced-care planning and helping patients to document their wishes. Similarly, she says, it means acknowledging that these patients are more likely to have comorbid conditions and identify with goals of care. “I don’t think there’s any way around this,” she says. “Medicare and hospitalists, whether by accident or design, are increasingly joined at the hip. That is something that hospitalists, as a profession, will always need to keep their eye on.”

A parallel trend is that other doctors increasingly view hospitalists as hospital specialists. “The hospitalist’s responsibilities are not just in terms of the patients they care for, but also in terms of the institution itself,” Dr. Berlinger says. Non-staff physicians, for example, expect hospitalists to know how a hospital’s in-patient care system works. Practically speaking, as electronic medical records (EMR) become more commonplace, hospitalists will be increasingly relied upon to understand a hospital’s information technology.

—Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, medical director, Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

New Economy, New Hospital Landscape

Douglas Wood, MD, chair of the Division of Health Care Policy and Research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., points to language in the federal healthcare reform legislation as evidence that hospitals and hospitalists will need to be in sync in other ways to avoid future penalties. One provision, for example, would increase the penalties for hospital-acquired infections. Other language seeks to reduce unnecessary readmissions.

Likewise, Dr. Wood says, addressing geographical variations in healthcare payments driven largely by unnecessary overutilization—including excessive use of ICU care, in-patient care, imaging, and specialist services—might mean asking hospitalists to take on more aspects of patient care.

Meanwhile, increased interest in demonstration projects that might achieve savings (e.g., accountable care organizations and bundled payments) suggests that proactive hospitals should again look to hospitalists. The flurry of new proposals won’t fundamentally change hospitalists’ responsibilities to provide effective and efficient care, “but it will put more emphasis on what they’re doing,” Dr. Wood says, “to the degree that hospitalists could take a lead in demonstrating how you can provide better outcomes at a lower overall utilization of resources.”

Regardless of how slowly or quickly these initiatives proceed at the national level, he says, hospitalists should be mindful that several states are well ahead of the curve and are likely to be more aggressive in instituting policy changes.

The Bottom Line

If there’s a single, overriding theme for 2010, Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, FHM, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says it might be that of dealing with the unknown. Squeezing healthcare costs and more tightly regulating inflation will have a greater effect on a hospital’s bottom line and thus impact what’s required of hospitalists. Even so, the profession will have to wait and see whether and how various proposals are codified and implemented. “We don’t know exactly what things are going to look like,” he says.

Nor is there a good sense of how new standards for transparency, quality, and accountability might be measured. “While people want more measurement and they want more report-card-type information, the data that we can acquire right now and how we analyze that data are still fairly primitive,” Dr. Flansbaum says. Even current benchmarks are lacking in how to determine who’s doing a good job and who isn’t, he says.

One big question that must be answered, then: Are we even looking at the right measurements? “Or, do the right measurements exist, or do we have the databases, the registries, the sources, to make the decisions we need to make?” he says.

Any new proposals will require another round of such questions and filling-in of blanks to add workable details to vague and potentially confusing language.

“I think we know that change is afoot, and most smart hospitalists know that the system needs to run leaner,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “But how each one of us is going to function in our hospital, and the kinds of demands that will be placed on us, and what we’re going to need to do with the doctors in the community and the other nonphysician colleagues that we work with, is all really unknown.” TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11): 1102-1112.

Image Source: PAGADESIGN, OVERSNAP/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

A Pain in the Bone

A 71‐year‐old man presented to a hospital with a one week history of fatigue, polyuria, and polydipsia. He also reported pain in his back, hips, and ribs, in addition to frequent falls, intermittent confusion, constipation, and a weight loss of 10 pounds over the last 2 weeks. He denied cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, fever, night sweats, headache, and focal weakness.

Polyuria, which is often associated with polydipsia, can be arbitrarily defined as a urine output exceeding 3 L per day. After excluding osmotic diuresis due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, the 3 major causes of polyuria are primary polydipsia, central diabetes insipidus, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Approximately 30% to 50% of cases of central diabetes insipidus are idiopathic; however, primary or secondary brain tumors or infiltrative diseases involving the hypothalamic‐pituitary region need to be considered in this 71‐year‐old man. The most common causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults are chronic lithium ingestion, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia. The patient describes symptoms that can result from severe hypercalcemia, including fatigue, confusion, constipation, polyuria, and polydipsia.

The patient's past medical history included long‐standing, insulin‐requiring type 2 diabetes with associated complications including coronary artery disease, transient ischemic attacks, proliferative retinopathy, peripheral diabetic neuropathy, and nephropathy. Seven years prior to presentation, he received a cadaveric renal transplant that was complicated by BK virus (polyomavirus) nephropathy and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Three years after his transplant surgery, he developed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, which was treated with local surgical resection. Two years after that, he developed stage I laryngeal cancer of the glottis and received laser surgery, and since then he had been considered disease‐free. He also had a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, osteoporosis, and depression. His medications included aspirin, amlodipine, metoprolol succinate, valsartan, furosemide, simvastatin, insulin, prednisone, sirolimus, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. He was a married psychiatrist. He denied tobacco use and reported occasional alcohol use.

The prolonged immunosuppressive therapy that is required following organ transplantation carries a markedly increased risk of the subsequent development of malignant tumors, including cancers of the lips and skin, lymphoproliferative disorders, and bronchogenic carcinoma. Primary brain lymphoma resulting in central diabetes insipidus would be unlikely in the absence of headache or focal weakness. An increased risk of lung cancer occurs in recipients of heart and lung transplants, and to a much lesser degree, recipients of kidney transplants. However, metastatic lung cancer is less likely in the absence of respiratory symptoms and smoking history (present in approximately 90% of all lung cancers). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, in its mild form, is relatively common in elderly patients with acute or chronic renal insufficiency because of a reduction in maximum urinary concentrating ability. On the other hand, this alone does not explain his remaining symptoms. The instinctive diagnosis in this case is tertiary hyperparathyroidism due to progression of untreated secondary hyperparathyroidism. This causes hypercalcemia, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and significant bone pain related to renal osteodystrophy.

On physical exam, the patient appeared chronically ill, but was in no acute distress. He weighed 197.6 pounds and his height was 70.5 inches. He was afebrile with a blood pressure of 146/82 mm Hg, a heart rate of 76 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 97% while breathing room air. He had no generalized lymphadenopathy. Thyroid examination was unremarkable. Examination of the lungs, heart, abdomen, and lower extremities was normal. The rectal examination revealed no masses or prostate nodules; a test for fecal occult blood was negative. He had loss of sensation to light touch and vibration in the feet with absent Achilles deep tendon reflexes. He had a poorly healing surgical wound on his forehead at the site of his prior skin cancer, but no rash or other lesions. There was no joint swelling or erythema. There were tender points over the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine; on multiple ribs; and on the pelvic rims.

Perhaps of greatest importance is the lack of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or other findings suggestive of diffuse lymphoproliferative disease. His multifocal bone tenderness is concerning for renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, or primary or metastatic bone disease. Cancers in men that metastasize to the bone usually originate from the prostate, lung, kidney, or thyroid gland. In any case, his physical examination did not reveal an enlarged, asymmetric, or nodular prostate or thyroid gland. I recommend a chest film to rule out primary lung malignancy and a basic laboratory evaluation to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

A complete blood count showed a normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL and a hematocrit of 25%. Other laboratory tests revealed the following values: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.1 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen, 70 mg/dL; creatinine, 3.5 mg/dL (most recent value 2 months ago was 1.9 mg/dL); total calcium, 13.2 mg/dL (normal range, 8.5‐10.5 mg/dL); phosphate, 5.3 mg/dL; magnesium, 2.5 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 0.5 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 130 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 28 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 19 U/L; albumin, 3.5 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 1258 IU/L (normal range, 105‐333 IU/L). A chest radiograph was normal.

The most important laboratory findings are severe hypercalcemia, acute on chronic renal failure, and anemia. Hypercalcemia most commonly results from malignancy or hyperparathyroidism. Less frequently, hypercalcemia may result from sarcoidosis, vitamin D intoxication, or hyperthyroidism. The degree of hypercalcemia is useful diagnostically as hyperparathyroidism commonly results in mild hypercalcemia (serum calcium concentration often below 11 mg/dL). Values above 13 mg/dL are unusual in hyperparathyroidism and are most often due to malignancy. Malignancy is often evident clinically by the time it causes hypercalcemia, and patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy are more often symptomatic than those with hyperparathyroidism. Additionally, localized bone pain and weight loss do not result from hypercalcemia itself and their presence also raises concern for malignancy.

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer occurring after transplantation but does not cause hypercalcemia. Squamous cancers of the head and neck can rarely cause hypercalcemia due to secretion of parathyroid hormone‐related peptide; however, his early‐stage laryngeal cancer and the expected high likelihood of cure argue against this possibility. Osteolytic metastases account for approximately 20% of cases of hypercalcemia of malignancy (Table 1). Prostate cancer rarely results in hypercalcemia since bone metastases are predominantly osteoblastic, whereas metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer, thyroid cancer, and kidney cancer more commonly cause hypercalcemia due to osteolytic bone lesions. The total alkaline phosphatase has been traditionally used to assess the osteoblastic component of bone remodeling. Its normal level tends to predict a negative bone scan and supports the likelihood of lytic lesions. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders, which include a wide range of syndromes, can rarely result in hypercalcemia. I am also worried about the possibility of multiple myeloma as he has the classic triad of hypercalcemia, bone pain, and subacute kidney injury.

|

| Osteolytic metastases |

| Breast cancer |

| Multiple myeloma |

| Lymphoma |

| Leukemia |

| Humoral hypercalcemia (PTH‐related protein) |

| Squamous cell carcinomas |

| Renal carcinomas |

| Bladder carcinoma |

| Breast cancer |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Leukemia |

| Lymphoma |

| 1,25‐Dihydroxyvitamin D secretion |

| Lymphoma |

| Ovarian dysgerminomas |

| Ectopic PTH secretion (rare) |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Lung carcinomas |

| Neuroectodermal tumor |

| Thyroid papillary carcinoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Pancreatic cancer |

The first purpose of the laboratory evaluation is to differentiate parathyroid hormone (PTH)‐mediated hypercalcemia (primary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism) from non‐PTH‐mediated hypercalcemia (primarily malignancy, hyperthyroidism, vitamin D intoxication, and granulomatous disease). The production of vitamin D metabolites, PTH‐related protein, or hypercalcemia from osteolysis in these latter cases results in suppressed PTH levels.

In severe elevations of calcium, the initial goals of treatment are directed toward fluid resuscitation with normal saline and, unless contraindicated, the immediate institution of bisphosphonate therapy. A loop diuretic such as furosemide is often used, but a recent review concluded that there is little evidence to support its use in this setting.

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous saline and furosemide. Additional laboratory evaluation revealed normal levels of prostate‐specific antigen and thyroid‐stimulating hormone. PTH was 44 pg/mL (the most recent value was 906 pg/mL eight years ago; normal range, 15‐65 pg/mL) and beta‐2 microglobulin (B2M) was 8 mg/L (normal range, 0.8‐2.2 mg/L).

The normal PTH level makes tertiary hyperparathyroidism unlikely and points toward non‐PTH‐related hypercalcemia. An elevated B2M level may occur in patients with chronic graft rejection, renal tubular dysfunction, dialysis‐related amyloidosis, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. LDH is often elevated in patients with multiple myeloma and lymphoma, but this is not a specific finding. The next laboratory test would be measurement of PTH‐related protein and vitamin D metabolites, as these tests can differentiate between the causes of non‐PTH‐mediated hypercalcemia.

Serum concentrations of the vitamin D metabolites, 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (calcidiol) and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), were low‐normal. PTH‐related protein was not detected.

The marked elevation of serum LDH and B2M, the relatively suppressed PTH level, combined with undetectable PTH‐related protein suggest multiple myeloma or lymphoma as the likely cause of the patient's clinical presentation. The combination of hypercalcemia and multifocal bone pain makes multiple myeloma the leading diagnosis as hypercalcemia is uncommon in patients with lymphoma, especially at the time of initial clinical presentation.

I would proceed with serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP, respectively) and a skeletal survey. If these tests do not confirm the diagnosis of multiple myeloma, I would order a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine. In addition, I would like to monitor his response to the intravenous saline and furosemide.

Forty‐eight hours after presentation, repeat serum calcium and creatinine levels were 11.3 mg/dL and 2.9 mg/dL, respectively. He received salmon calcitonin 4 U/kg every 12 hours. Pamidronate was avoided because of his kidney disease. His confusion resolved. He received intravenous morphine intermittently to alleviate his bone pain.

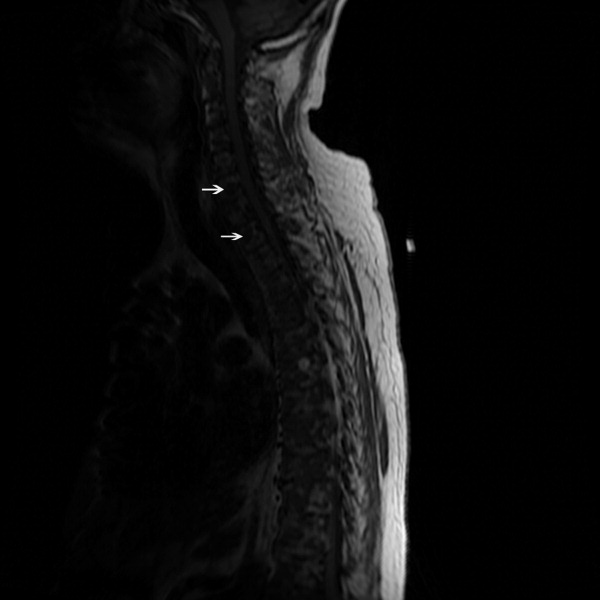

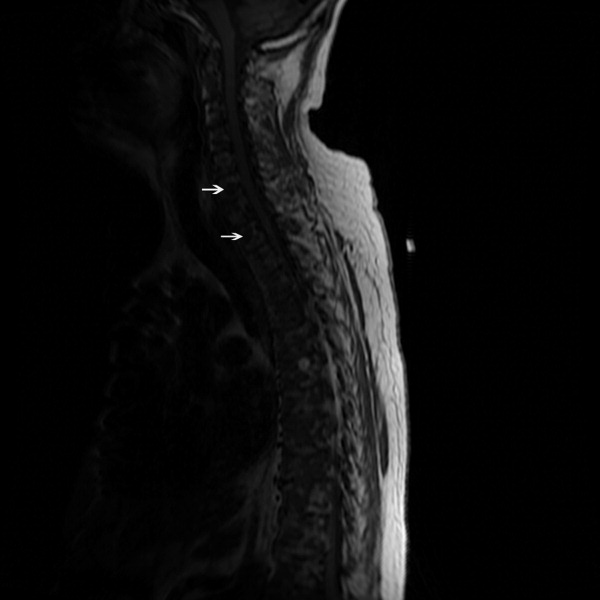

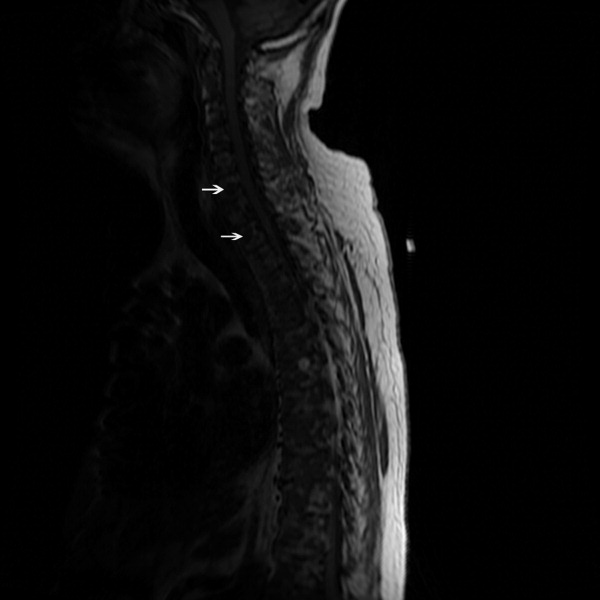

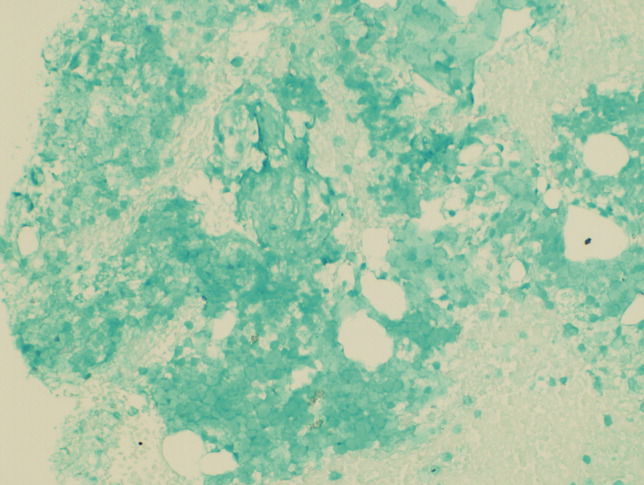

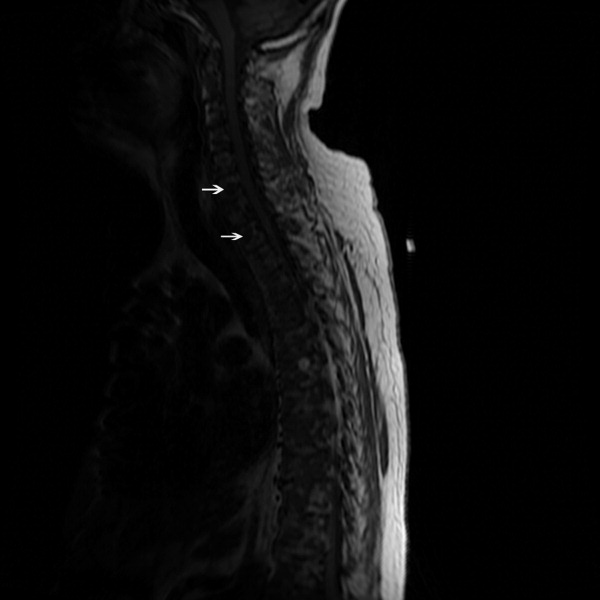

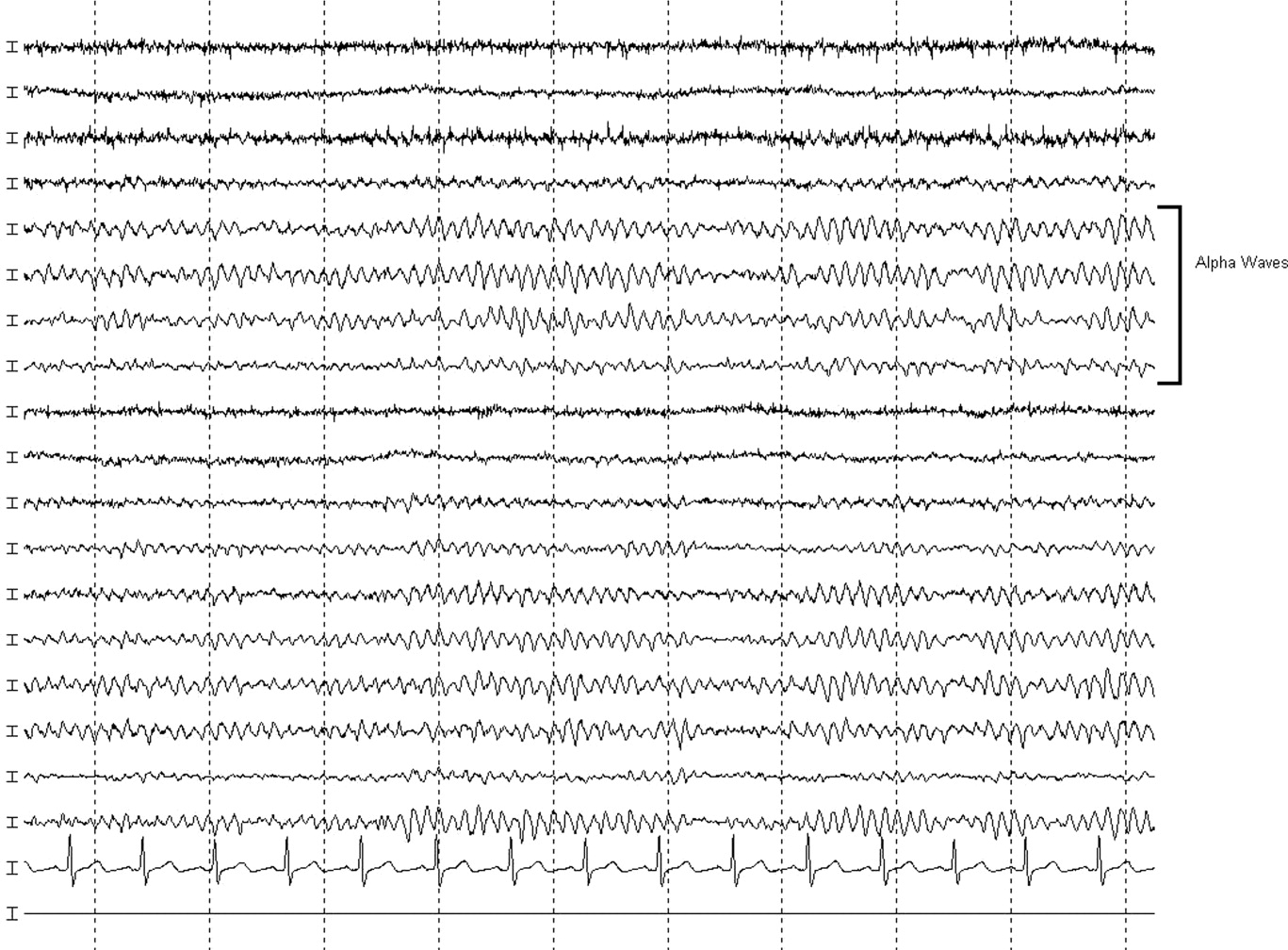

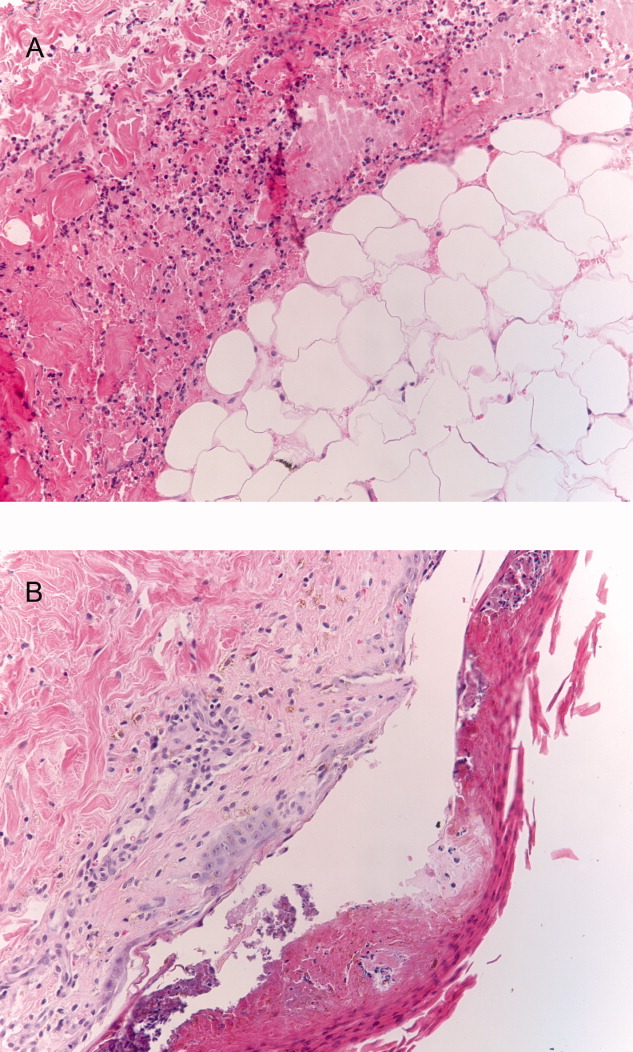

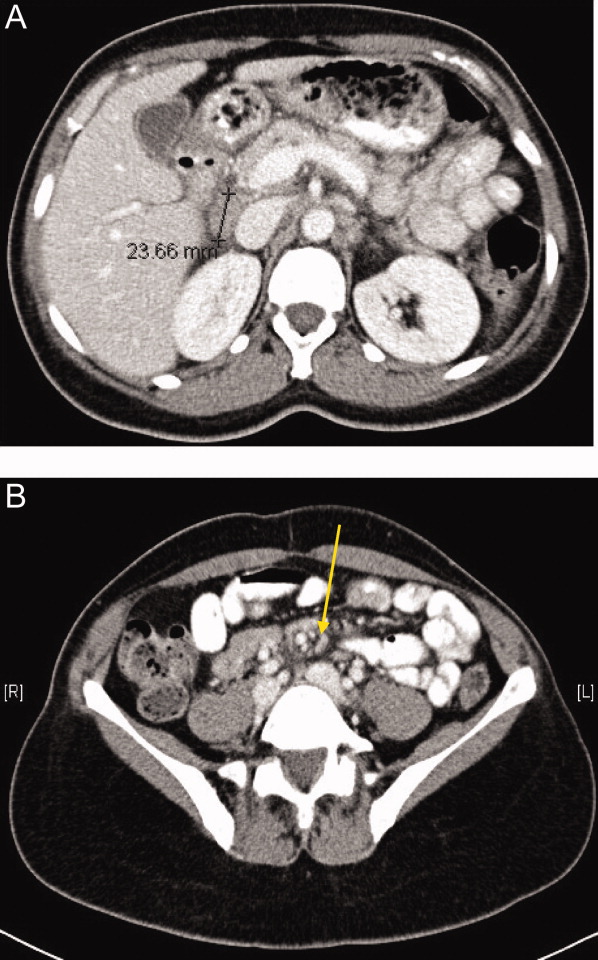

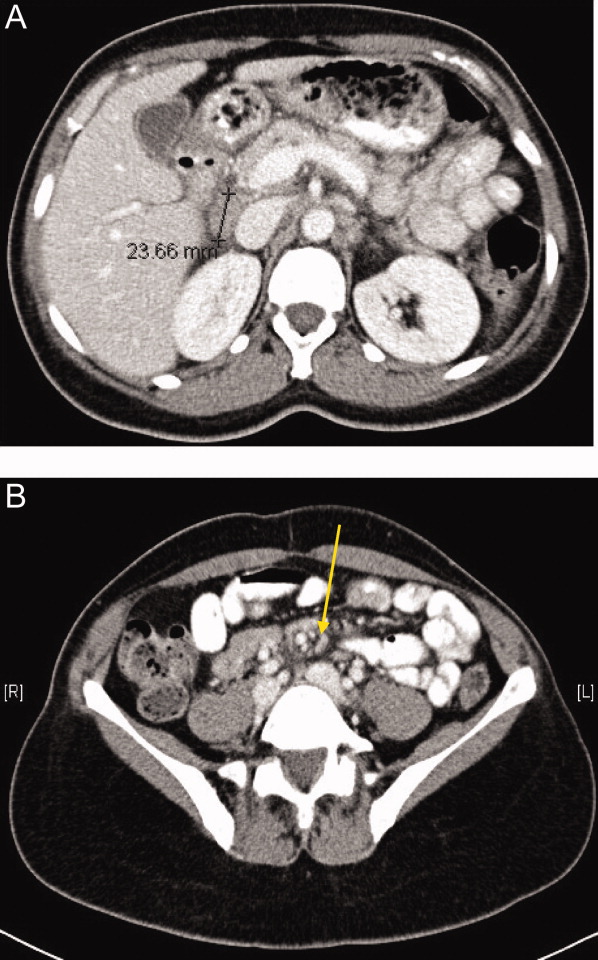

The SPEP revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) lambda (light chain) spike representing roughly 3% (200 mg/dL) of total protein. His serum Ig levels were normal. The UPEP was negative for monoclonal immunoglobulin and Bence‐Jones protein. The skeletal survey revealed marked osteopenia, and the bone scan was normal. An MRI of the spine showed multiple round lesions in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine (Figure 1). A CT of the chest showed similar bone lesions in the ribs and pelvis. A CT of the abdomen and chest did not suggest any primary malignancy nor did it show thoracic or abdominal lymphadenopathy.

The lack of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or a visceral mass by CT imaging and physical examination, along with the normal PSA level, exclude most common forms of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma and bone metastasis from solid tumors. In multiple myeloma, cytokines secreted by plasma cells suppress osteoblast activity; therefore, while discrete lytic bone lesions are apparent on skeletal survey, the bone scan is typically normal. The absence of lytic lesions, normal serum immunoglobulin levels, and unremarkable UPEP make multiple myeloma or light‐chain deposition disease a less likely diagnosis.

Typically, primary lymphoma of the bone produces increased uptake with bone scanning. However, because primary lymphoma of the bone is one of the least common primary skeletal malignancies and varies widely in appearance on imaging, confident diagnosis based on imaging alone usually is not possible.

Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) refers to a syndrome that ranges from a self‐limited form of lymphoproliferation to an aggressive disseminated disease. Although the patient is at risk for PTLD, isolated bone involvement has only rarely been reported.

Primary lymphoma of the bone and PTLD are my leading diagnoses in this patient. At this point, I recommend a bone marrow biopsy and biopsy of an easily accessible representative bone lesion with special staining for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) (EBV‐encoded RNA [EBER] and latent membrane protein 1 [LMP1]). I expect this test to provide a definitive diagnosis. As 95% of PTLD cases are induced by infection with EBV, information regarding pretransplantation EBV status of the patient and the donor, current EBV status of the patient, and type and intensity of immunosuppression at the time of transplantation would be very helpful to determine their likelihood.

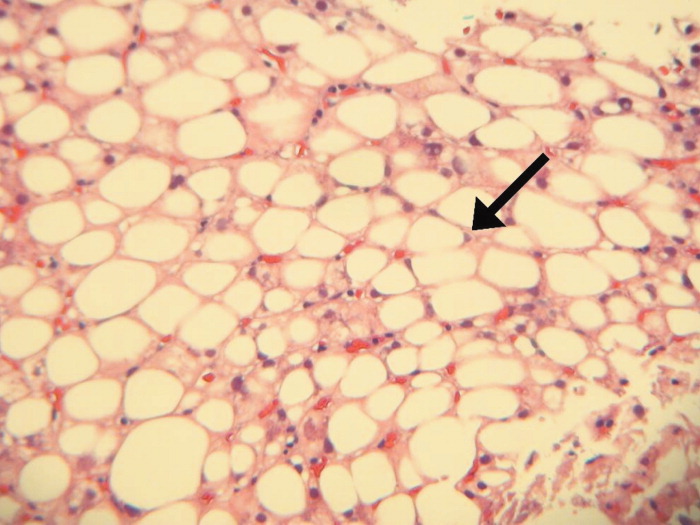

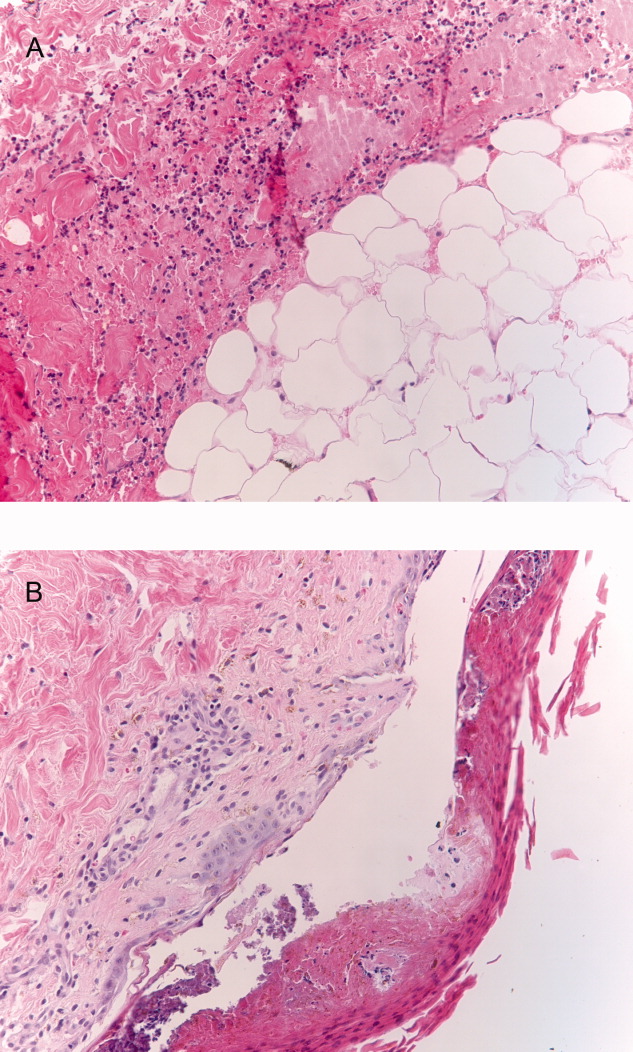

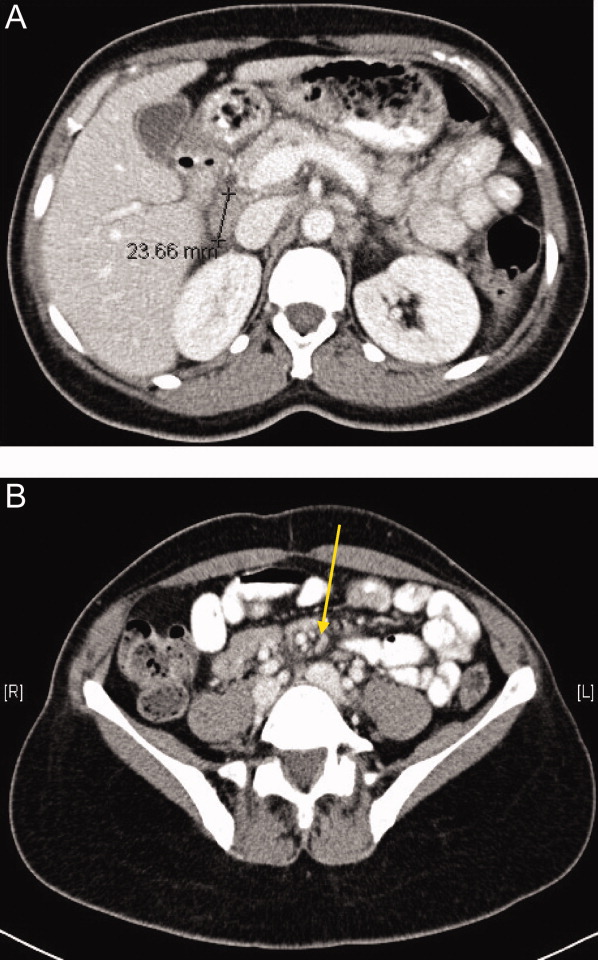

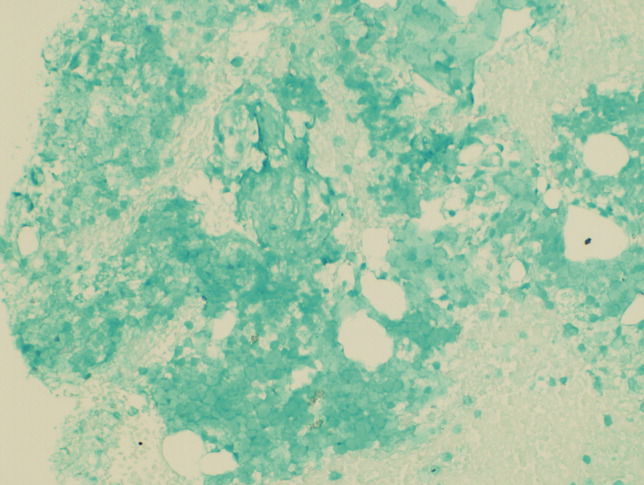

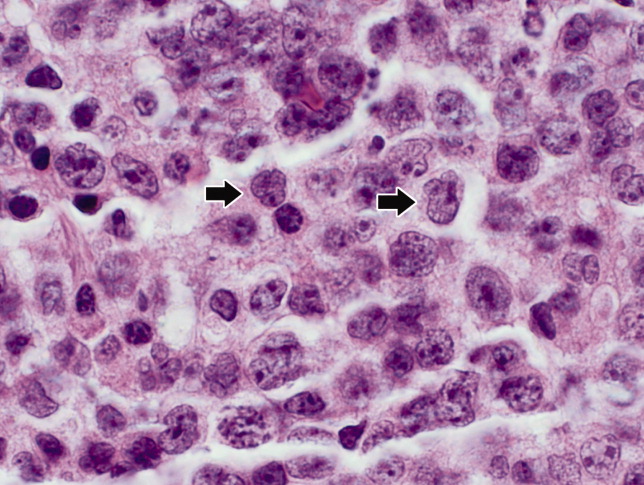

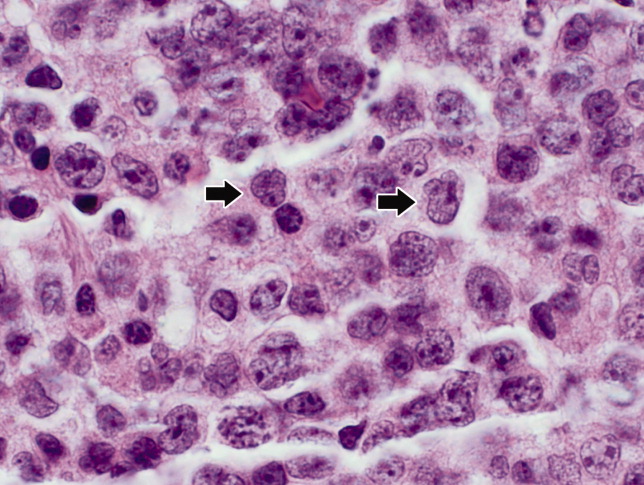

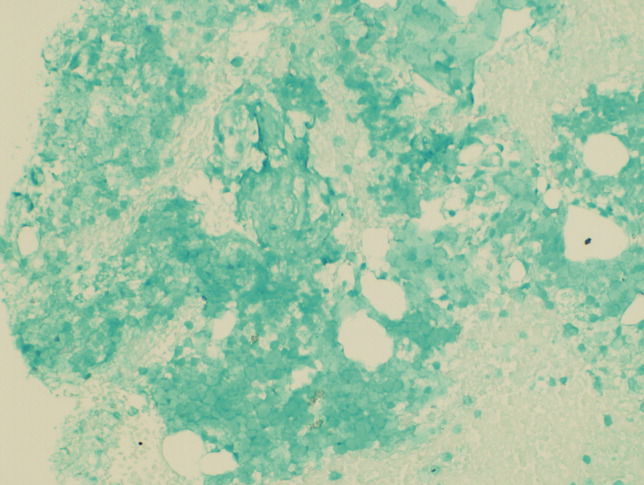

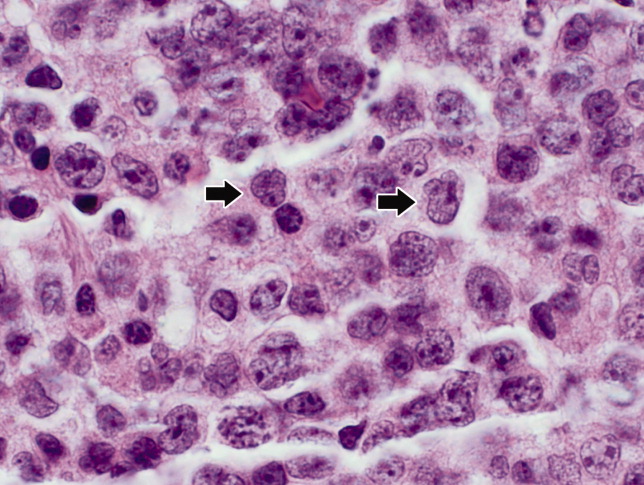

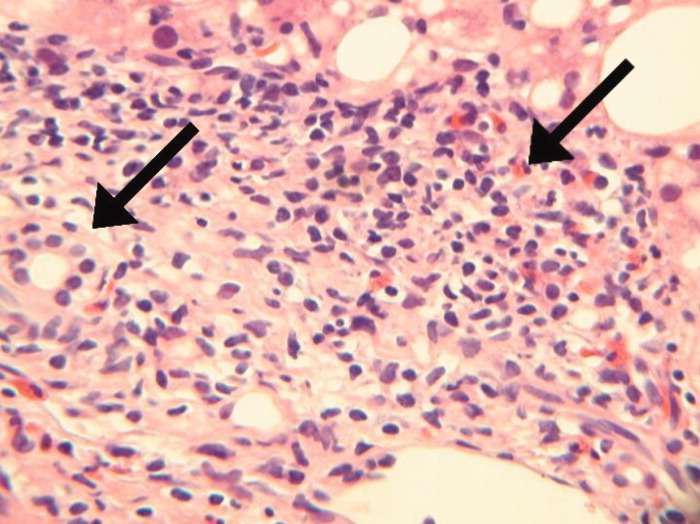

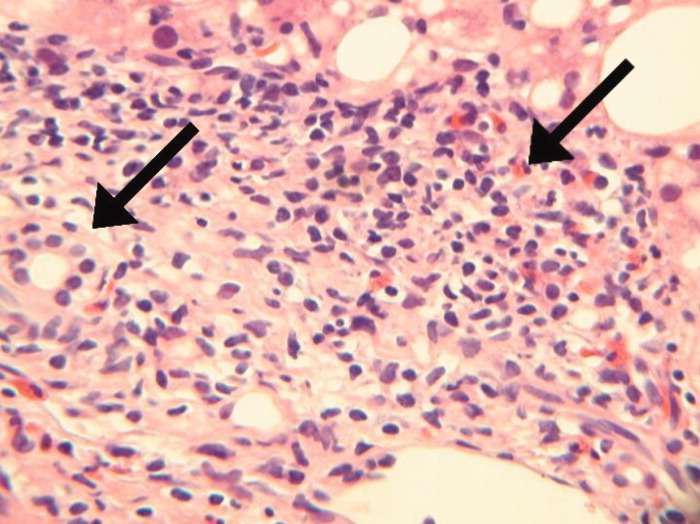

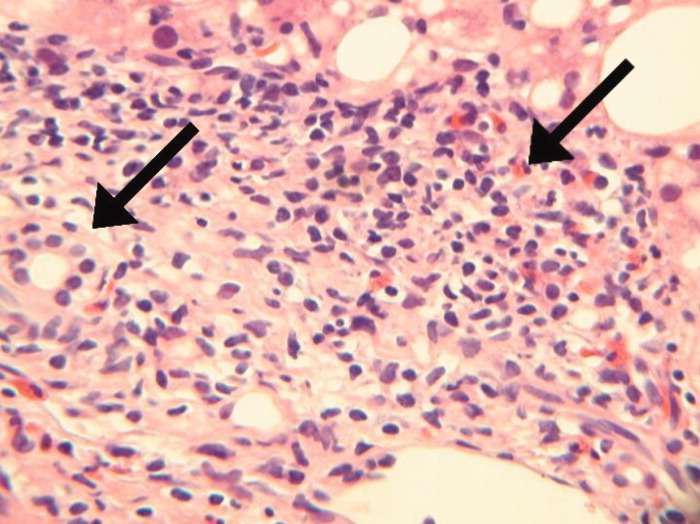

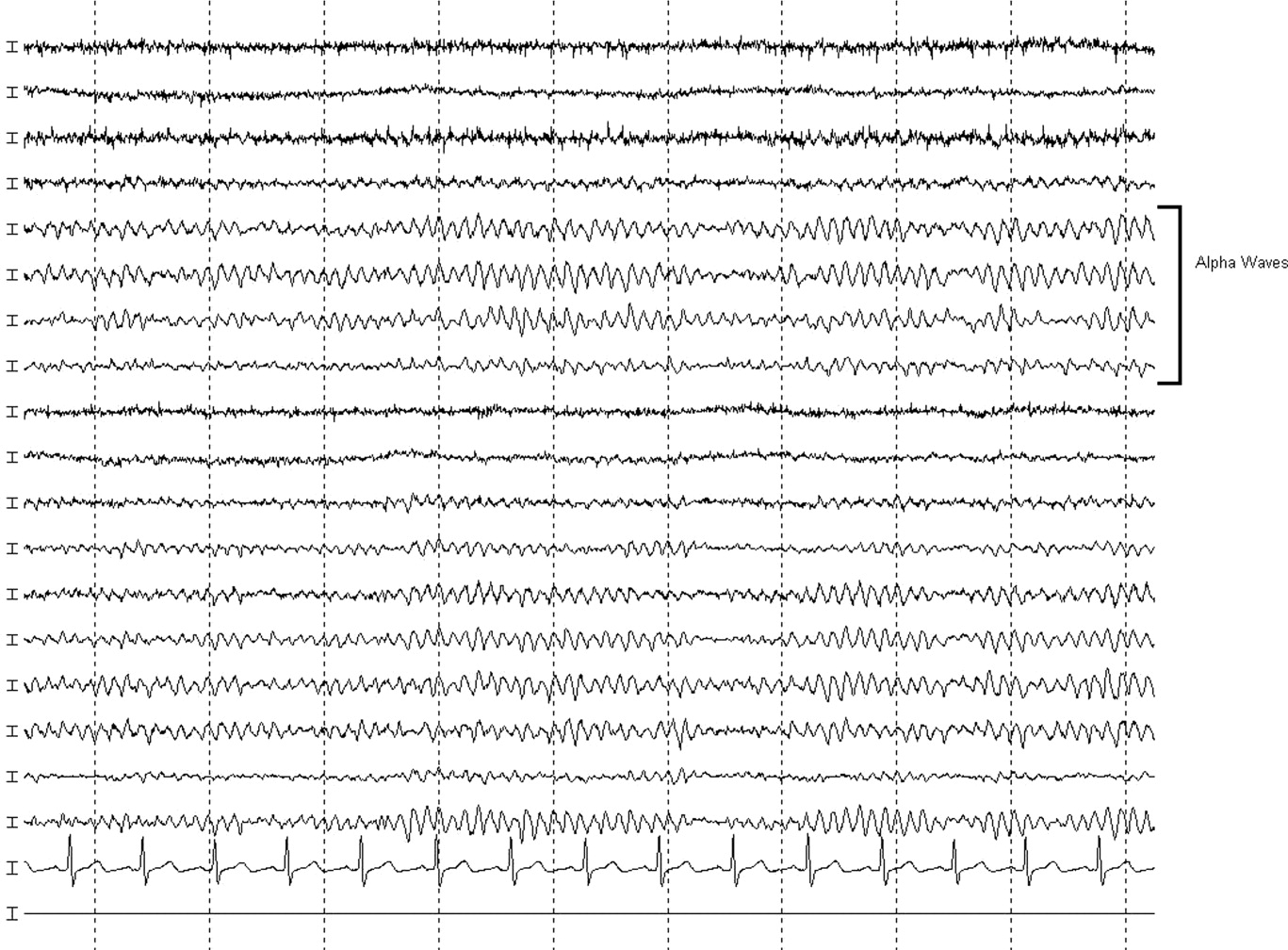

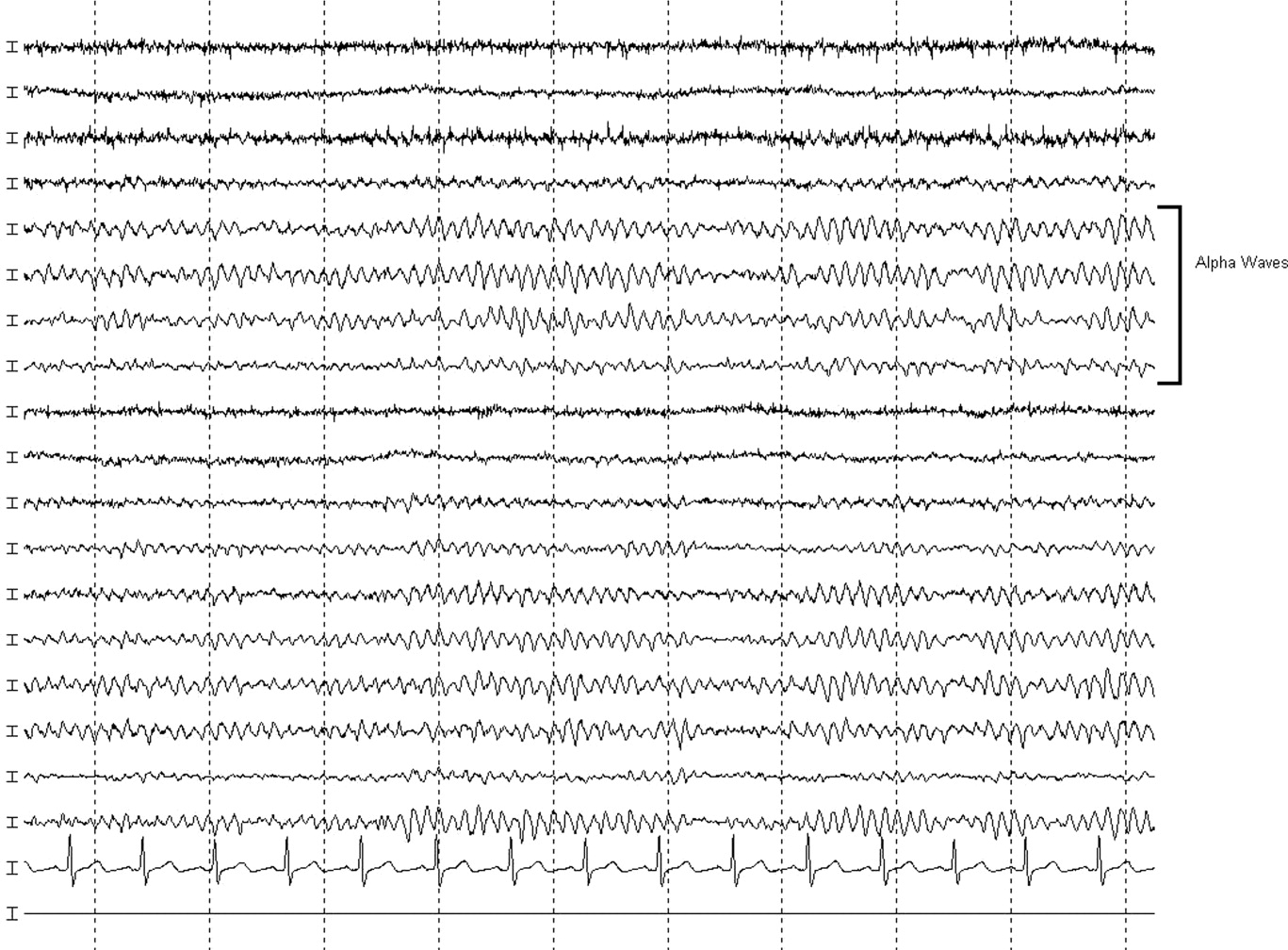

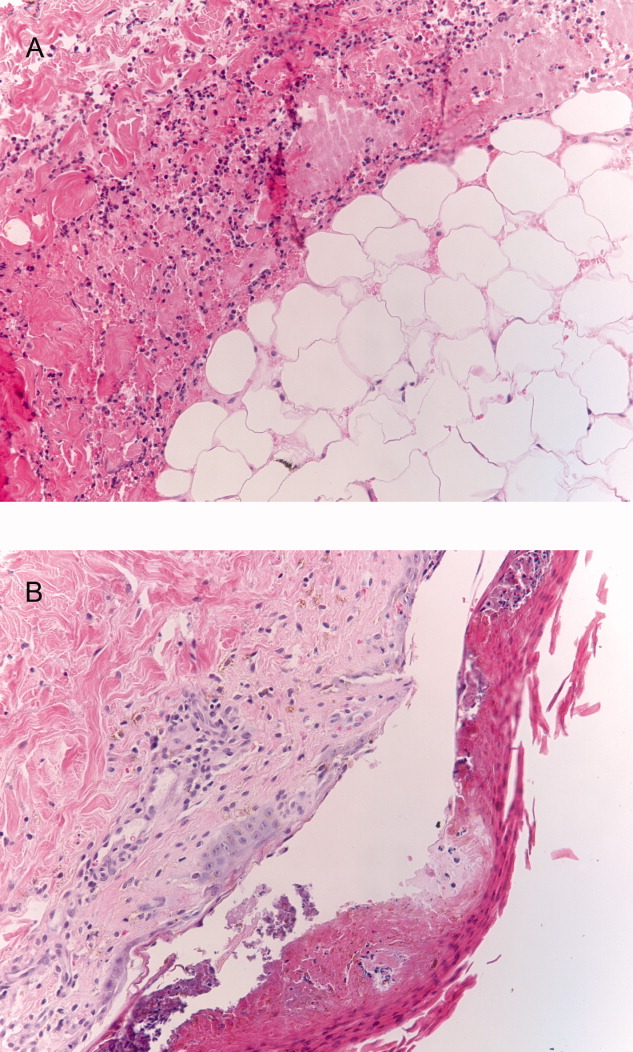

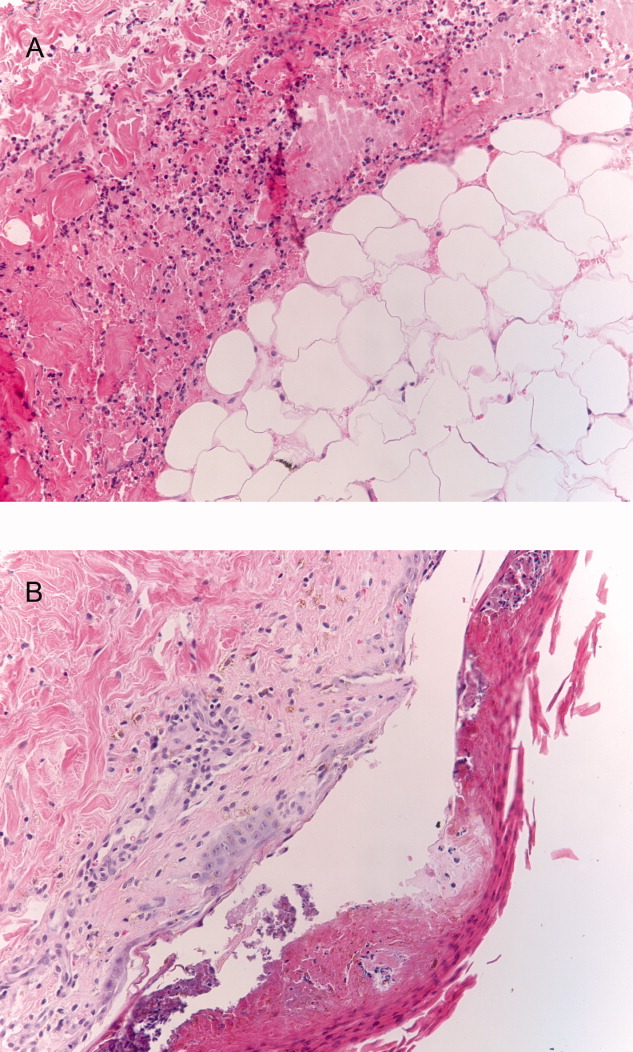

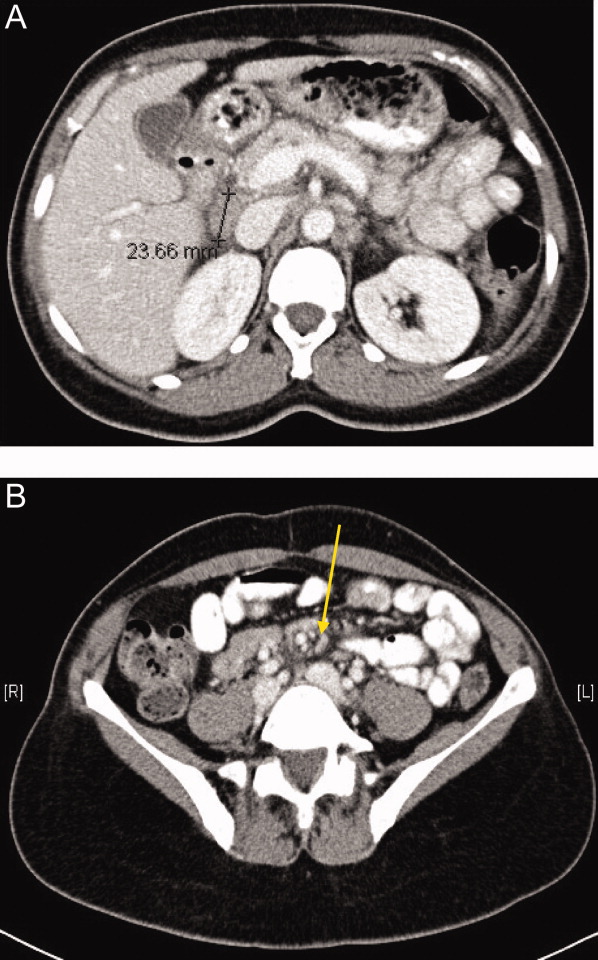

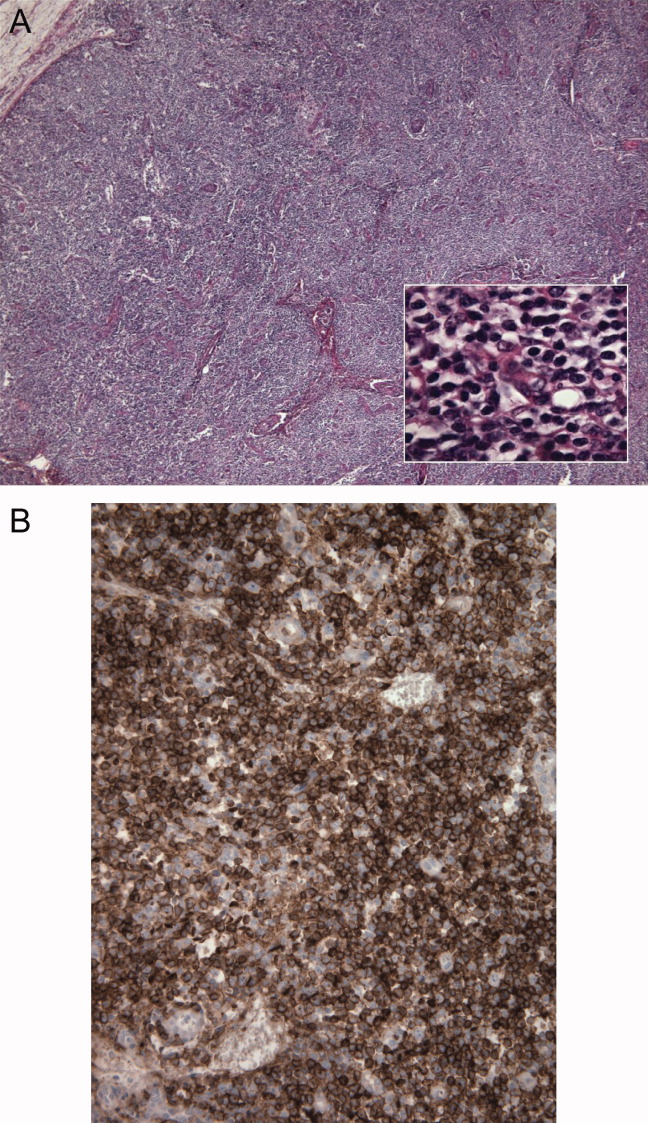

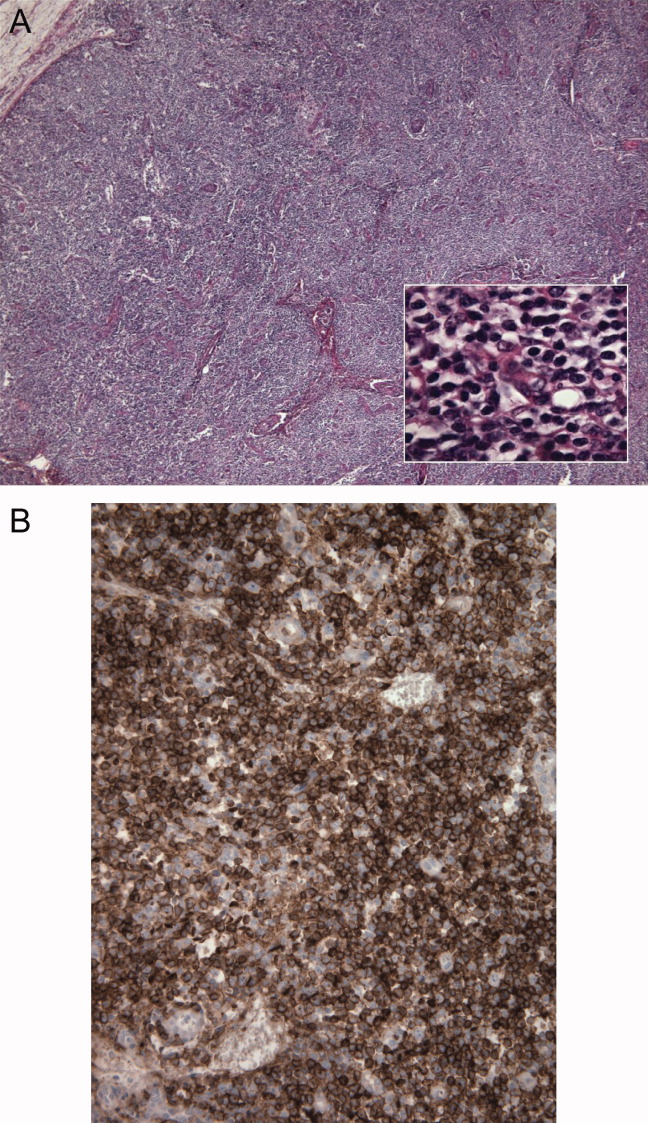

Seventy‐two hours after presentation, his serum calcium level normalized and most of his symptoms improved. Calcitonin was discontinued, and he was maintained on oral hydration. On hospital day number 5, he underwent CT‐guided bone biopsy of the L4 vertebral body, which showed large aggregates of atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2). These cells were predominantly B‐cells interspersed with small reactive T‐cells. The cells did not express EBV LMP1 or EBER (Figure 3). On hospital day 7, he underwent a bone marrow biopsy, which revealed similar large atypical lymphoid cells that comprised the majority of marrow space (Figure 4). By immunohistochemistry, these cells brightly expressed the pan B cell marker, CD20, and coexpressed bcl‐2. EBER and LMP1 were also negative. A flow cytometry of the bone marrow demonstrated a lambda light chain restriction within the B lymphocytes.

The medical records indicated that the patient had positive pretransplantation EBV serologies. He received a regimen based on sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone, and did not receive high doses of induction or maintenance immunosuppressive therapy.

The biopsy results establish a diagnosis of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma of the bone. PTLD is unlikely given his positive pretransplantation EBV status, the late onset of his disease (6 years after transplantation), the isolated bone involvement, and the negative EBER and LMP1 tests.

The patient was discharged and was readmitted 1 week later for induction chemotherapy with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone [EPOCH]Rituxan (rituximab). Over the next several months, he received 6 cycles of chemotherapy, his hypercalcemia resolved, and his back pain improved.

Commentary

Hypercalcemia is among the most common causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults.1 A urinary concentrating defect usually becomes clinically apparent if the plasma calcium concentration is persistently above 11 mg/dL.1 This defect is generally reversible with correction of the hypercalcemia but may persist in patients in whom interstitial nephritis has induced permanent medullary damage. The mechanism by which the concentrating defect occurs is incompletely understood but may be related to impairments in sodium chloride reabsorption in the thick ascending limb and in the ability of antidiuretic hormone to increase water permeability in the collecting tubules.1

Although hypercalcemia in otherwise healthy outpatients is usually due to primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy is more often responsible for hypercalcemia in hospitalized patients.2 While the signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia are similar regardless of the cause, several clinical features may help distinguish the etiology of hypercalcemia. For instance, the presence of tachycardia, warm skin, thinning of the hair, stare and lid lag, and widened pulse pressure points toward hypercalcemia related to hyperthyroidism. In addition, risk factors and comorbidities guide the diagnostic process. For example, low‐level hypercalcemia in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with a normal physical examination suggests primary hyperparathyroidism. In contrast, hypercalcemia in a transplant patient raises concern of malignancy including PTLDs.3, 4

PTLDs are uncommon causes of hypercalcemia but are among the most serious and potentially fatal complications of chronic immunosuppression in transplant recipients.5 They occur in 1.9% of patients after kidney transplantation. The lymphoproliferative disorders occurring after transplantation have different characteristics from those that occur in the general population. Non‐Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for 65% of lymphomas in the general population, compared to 93% in transplant recipients.5, 6 The pathogenesis of PTLD appears to be related to B cell proliferation induced by infection with EBV in the setting of chronic immunosuppression.6 Therefore, there is an increased frequency of PTLD among transplant recipients who are EBV seronegative at the time of operation. These patients, who have no preoperative immunity to EBV, usually acquire the infection from the donor. The level of immunosuppression (intensity and type) influences PTLD rates as well. The disease typically occurs within 12 months after transplantation and in two‐thirds of cases involves extranodal sites. Among these sites, the gastrointestinal tract is involved in about 26% of cases and central nervous system in about 27%. Isolated bone involvement is exceedingly rare.5, 6

Primary lymphoma of the bone is another rare cause of hypercalcemia and accounts for less than 5% of all primary bone tumors.7 The majority of cases are of the non‐Hodgkin's type, characterized as diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas, with peak occurrence in the sixth to seventh decades of life.8 The classic imaging findings of primary lymphoma of the bone are a solitary metadiaphyseal lesion with a layered periosteal reaction on plain radiographs, and corresponding surrounding soft‐tissue mass on MRI.9 Less commonly, primary lymphoma of the bone can be multifocal with diffuse osseous involvement and variable radiographic appearances, as in this case. Most series have reported that the long bones are affected most frequently (especially the femur), although a large series showed equal numbers of cases presenting in the long bones and the spine.712

In order to diagnose primary lymphoma of the bone, it is necessary to exclude nodal or disseminated disease by physical examination and imaging. As plain films are often normal, bone scan or MRI of clinically affected areas is necessary to establish disease extent.9 Distinguishing primary bone lymphomas (PLB) from other bone tumors is important because PLB has a better response to therapy and a better prognosis.10, 11

Randomized trials addressing treatment options for primary lymphoma of bone are not available. Historically, PLB was treated with radiotherapy alone with good local control. However, the rate of distant relapses was relatively high. Currently, chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy is preferred; 5‐year survival is approximately 70% after combined therapy.10, 11

In this case, symptomatic hypercalcemia, a history of transplantation, marked elevation of both LDH and B2M, and a normal PTH level all pointed toward the correct diagnosis of malignancy. Low or normal levels of vitamin D metabolites and PTH‐related protein occur in 20% of patients with hypercalcemia caused by malignancy.13, 14 Diffuse osteopenia on skeletal survey is a prominent feature of renal osteodystrophy or osteoporosis related to chronic corticosteroid use. However, in a patient with diffuse osteopenia and hypercalcemia, clinicians must consider multiple myeloma and other lymphoproliferative disorders; the absence of osteoblastic or osteolytic lesions and a normal alkaline phosphatase do not rule out these diagnoses. When the results of serum and urine protein electrophoresis exclude multiple myeloma, the next investigation should be a bone biopsy to exclude PLB, an uncommon cause of anemia, hypercalcemia, and osteopenic, painful bones.

Key Points for Hospitalists

-

Normal total alkaline phosphatase does not exclude primary or metastatic bone malignancy. While a normal level tends to predict a negative bone scan, further diagnostic tests are needed to exclude bone malignancy if high clinical suspicion exists.

-

The degree of hypercalcemia is useful diagnostically; values above 13 mg/dL are most often due to malignancy.

-

Hypercalcemia in transplant patients deserves special attention due to an increased risk of malignancy, including squamous cancers of the lips and skin, lymphoproliferative disorders, and bronchogenic carcinoma.

-

While rare, consider primary lymphoma of the bone in patients with hypercalcemia and bone pain, along with the more common diagnoses of multiple myeloma and metastatic bone disease.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring the patient and the discussant.

- ,.Clinical Physiology of Acid‐Base and Electrolyte Disorders.5th ed.New York:McGraw‐Hill;2001:754–758.

- ,.Hypercalcemia: clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. In: Favus MJ, ed.Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism.5th ed.Washington, DC:American Society for Bone and Mineral Research;2003:225–230.

- ,,, et al.Malignancy after renal transplantation: analysis of incidence and risk factors in 1700 patients followed during a 25‐year period.Transplant Proc.1997;29:831–833.

- ,.Malignancy‐associated hypercalcemia. In: DeGroot L, Jameson LJ, eds.Endocrinology.4th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2001:1093–1100.

- ,.Diagnosis and management of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid‐organ transplant recipients.Clin Infect Dis.2001;33(suppl 1):S38–S46.

- ,,, et al.Epstein‐Barr virus‐induced posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: ASTS/ASTP EBV‐PTLD Task Force and The Mayo Clinic Organized International Consensus Development Meeting.Transplantation.1999;68:1517–1525.

- ,,, et al.Primary bone lymphoma: a new and detailed characterization of 28 patients in a single‐institution study.Jpn J Clin Oncol.2007;37(3):216–223.

- ,,, et al.Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma of bone. An analysis of differentiation‐associated antigens with clinical correlation.Am J Surg Pathol.2003;27:1269–1277.

- ,,,,,.Primary bone lymphoma: radiographic‐MR imaging correlation.Radiographics.2003;23:1371–1383.

- ,,, et al.Primary bone lymphoma in 24 patients treated between 1955 and 1999.Clin Orthop.2002;397:271–280.

- ,,, et al.A clinicopathological retrospective study of 131 patients with primary bone lymphoma: a population‐based study of successively treated cohorts from the British Columbia Cancer Agency.Ann Oncol.2007;18:129.

- ,,, et al.Malignant lymphoma of bone.Cancer.1986;58:2646–2655.

- .Hypercalcemia in malignant lymphoma and leukemia.Ann N Y Acad Sci.1974;230:240–246.

- .Incidence and prognostic significance of hypercalcemia in B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. [Letter]J Clin Pathol.2002;55:637–638.

A 71‐year‐old man presented to a hospital with a one week history of fatigue, polyuria, and polydipsia. He also reported pain in his back, hips, and ribs, in addition to frequent falls, intermittent confusion, constipation, and a weight loss of 10 pounds over the last 2 weeks. He denied cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, fever, night sweats, headache, and focal weakness.

Polyuria, which is often associated with polydipsia, can be arbitrarily defined as a urine output exceeding 3 L per day. After excluding osmotic diuresis due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, the 3 major causes of polyuria are primary polydipsia, central diabetes insipidus, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Approximately 30% to 50% of cases of central diabetes insipidus are idiopathic; however, primary or secondary brain tumors or infiltrative diseases involving the hypothalamic‐pituitary region need to be considered in this 71‐year‐old man. The most common causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults are chronic lithium ingestion, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia. The patient describes symptoms that can result from severe hypercalcemia, including fatigue, confusion, constipation, polyuria, and polydipsia.

The patient's past medical history included long‐standing, insulin‐requiring type 2 diabetes with associated complications including coronary artery disease, transient ischemic attacks, proliferative retinopathy, peripheral diabetic neuropathy, and nephropathy. Seven years prior to presentation, he received a cadaveric renal transplant that was complicated by BK virus (polyomavirus) nephropathy and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Three years after his transplant surgery, he developed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, which was treated with local surgical resection. Two years after that, he developed stage I laryngeal cancer of the glottis and received laser surgery, and since then he had been considered disease‐free. He also had a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, osteoporosis, and depression. His medications included aspirin, amlodipine, metoprolol succinate, valsartan, furosemide, simvastatin, insulin, prednisone, sirolimus, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. He was a married psychiatrist. He denied tobacco use and reported occasional alcohol use.

The prolonged immunosuppressive therapy that is required following organ transplantation carries a markedly increased risk of the subsequent development of malignant tumors, including cancers of the lips and skin, lymphoproliferative disorders, and bronchogenic carcinoma. Primary brain lymphoma resulting in central diabetes insipidus would be unlikely in the absence of headache or focal weakness. An increased risk of lung cancer occurs in recipients of heart and lung transplants, and to a much lesser degree, recipients of kidney transplants. However, metastatic lung cancer is less likely in the absence of respiratory symptoms and smoking history (present in approximately 90% of all lung cancers). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, in its mild form, is relatively common in elderly patients with acute or chronic renal insufficiency because of a reduction in maximum urinary concentrating ability. On the other hand, this alone does not explain his remaining symptoms. The instinctive diagnosis in this case is tertiary hyperparathyroidism due to progression of untreated secondary hyperparathyroidism. This causes hypercalcemia, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and significant bone pain related to renal osteodystrophy.

On physical exam, the patient appeared chronically ill, but was in no acute distress. He weighed 197.6 pounds and his height was 70.5 inches. He was afebrile with a blood pressure of 146/82 mm Hg, a heart rate of 76 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 97% while breathing room air. He had no generalized lymphadenopathy. Thyroid examination was unremarkable. Examination of the lungs, heart, abdomen, and lower extremities was normal. The rectal examination revealed no masses or prostate nodules; a test for fecal occult blood was negative. He had loss of sensation to light touch and vibration in the feet with absent Achilles deep tendon reflexes. He had a poorly healing surgical wound on his forehead at the site of his prior skin cancer, but no rash or other lesions. There was no joint swelling or erythema. There were tender points over the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine; on multiple ribs; and on the pelvic rims.

Perhaps of greatest importance is the lack of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or other findings suggestive of diffuse lymphoproliferative disease. His multifocal bone tenderness is concerning for renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, or primary or metastatic bone disease. Cancers in men that metastasize to the bone usually originate from the prostate, lung, kidney, or thyroid gland. In any case, his physical examination did not reveal an enlarged, asymmetric, or nodular prostate or thyroid gland. I recommend a chest film to rule out primary lung malignancy and a basic laboratory evaluation to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

A complete blood count showed a normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL and a hematocrit of 25%. Other laboratory tests revealed the following values: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.1 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen, 70 mg/dL; creatinine, 3.5 mg/dL (most recent value 2 months ago was 1.9 mg/dL); total calcium, 13.2 mg/dL (normal range, 8.5‐10.5 mg/dL); phosphate, 5.3 mg/dL; magnesium, 2.5 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 0.5 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 130 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 28 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 19 U/L; albumin, 3.5 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 1258 IU/L (normal range, 105‐333 IU/L). A chest radiograph was normal.

The most important laboratory findings are severe hypercalcemia, acute on chronic renal failure, and anemia. Hypercalcemia most commonly results from malignancy or hyperparathyroidism. Less frequently, hypercalcemia may result from sarcoidosis, vitamin D intoxication, or hyperthyroidism. The degree of hypercalcemia is useful diagnostically as hyperparathyroidism commonly results in mild hypercalcemia (serum calcium concentration often below 11 mg/dL). Values above 13 mg/dL are unusual in hyperparathyroidism and are most often due to malignancy. Malignancy is often evident clinically by the time it causes hypercalcemia, and patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy are more often symptomatic than those with hyperparathyroidism. Additionally, localized bone pain and weight loss do not result from hypercalcemia itself and their presence also raises concern for malignancy.

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer occurring after transplantation but does not cause hypercalcemia. Squamous cancers of the head and neck can rarely cause hypercalcemia due to secretion of parathyroid hormone‐related peptide; however, his early‐stage laryngeal cancer and the expected high likelihood of cure argue against this possibility. Osteolytic metastases account for approximately 20% of cases of hypercalcemia of malignancy (Table 1). Prostate cancer rarely results in hypercalcemia since bone metastases are predominantly osteoblastic, whereas metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer, thyroid cancer, and kidney cancer more commonly cause hypercalcemia due to osteolytic bone lesions. The total alkaline phosphatase has been traditionally used to assess the osteoblastic component of bone remodeling. Its normal level tends to predict a negative bone scan and supports the likelihood of lytic lesions. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders, which include a wide range of syndromes, can rarely result in hypercalcemia. I am also worried about the possibility of multiple myeloma as he has the classic triad of hypercalcemia, bone pain, and subacute kidney injury.

|

| Osteolytic metastases |

| Breast cancer |

| Multiple myeloma |

| Lymphoma |

| Leukemia |

| Humoral hypercalcemia (PTH‐related protein) |

| Squamous cell carcinomas |

| Renal carcinomas |

| Bladder carcinoma |

| Breast cancer |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Leukemia |

| Lymphoma |

| 1,25‐Dihydroxyvitamin D secretion |

| Lymphoma |

| Ovarian dysgerminomas |

| Ectopic PTH secretion (rare) |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Lung carcinomas |

| Neuroectodermal tumor |

| Thyroid papillary carcinoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Pancreatic cancer |

The first purpose of the laboratory evaluation is to differentiate parathyroid hormone (PTH)‐mediated hypercalcemia (primary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism) from non‐PTH‐mediated hypercalcemia (primarily malignancy, hyperthyroidism, vitamin D intoxication, and granulomatous disease). The production of vitamin D metabolites, PTH‐related protein, or hypercalcemia from osteolysis in these latter cases results in suppressed PTH levels.

In severe elevations of calcium, the initial goals of treatment are directed toward fluid resuscitation with normal saline and, unless contraindicated, the immediate institution of bisphosphonate therapy. A loop diuretic such as furosemide is often used, but a recent review concluded that there is little evidence to support its use in this setting.

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous saline and furosemide. Additional laboratory evaluation revealed normal levels of prostate‐specific antigen and thyroid‐stimulating hormone. PTH was 44 pg/mL (the most recent value was 906 pg/mL eight years ago; normal range, 15‐65 pg/mL) and beta‐2 microglobulin (B2M) was 8 mg/L (normal range, 0.8‐2.2 mg/L).

The normal PTH level makes tertiary hyperparathyroidism unlikely and points toward non‐PTH‐related hypercalcemia. An elevated B2M level may occur in patients with chronic graft rejection, renal tubular dysfunction, dialysis‐related amyloidosis, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. LDH is often elevated in patients with multiple myeloma and lymphoma, but this is not a specific finding. The next laboratory test would be measurement of PTH‐related protein and vitamin D metabolites, as these tests can differentiate between the causes of non‐PTH‐mediated hypercalcemia.

Serum concentrations of the vitamin D metabolites, 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (calcidiol) and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), were low‐normal. PTH‐related protein was not detected.

The marked elevation of serum LDH and B2M, the relatively suppressed PTH level, combined with undetectable PTH‐related protein suggest multiple myeloma or lymphoma as the likely cause of the patient's clinical presentation. The combination of hypercalcemia and multifocal bone pain makes multiple myeloma the leading diagnosis as hypercalcemia is uncommon in patients with lymphoma, especially at the time of initial clinical presentation.

I would proceed with serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP, respectively) and a skeletal survey. If these tests do not confirm the diagnosis of multiple myeloma, I would order a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine. In addition, I would like to monitor his response to the intravenous saline and furosemide.

Forty‐eight hours after presentation, repeat serum calcium and creatinine levels were 11.3 mg/dL and 2.9 mg/dL, respectively. He received salmon calcitonin 4 U/kg every 12 hours. Pamidronate was avoided because of his kidney disease. His confusion resolved. He received intravenous morphine intermittently to alleviate his bone pain.

The SPEP revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) lambda (light chain) spike representing roughly 3% (200 mg/dL) of total protein. His serum Ig levels were normal. The UPEP was negative for monoclonal immunoglobulin and Bence‐Jones protein. The skeletal survey revealed marked osteopenia, and the bone scan was normal. An MRI of the spine showed multiple round lesions in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine (Figure 1). A CT of the chest showed similar bone lesions in the ribs and pelvis. A CT of the abdomen and chest did not suggest any primary malignancy nor did it show thoracic or abdominal lymphadenopathy.

The lack of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or a visceral mass by CT imaging and physical examination, along with the normal PSA level, exclude most common forms of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma and bone metastasis from solid tumors. In multiple myeloma, cytokines secreted by plasma cells suppress osteoblast activity; therefore, while discrete lytic bone lesions are apparent on skeletal survey, the bone scan is typically normal. The absence of lytic lesions, normal serum immunoglobulin levels, and unremarkable UPEP make multiple myeloma or light‐chain deposition disease a less likely diagnosis.

Typically, primary lymphoma of the bone produces increased uptake with bone scanning. However, because primary lymphoma of the bone is one of the least common primary skeletal malignancies and varies widely in appearance on imaging, confident diagnosis based on imaging alone usually is not possible.

Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) refers to a syndrome that ranges from a self‐limited form of lymphoproliferation to an aggressive disseminated disease. Although the patient is at risk for PTLD, isolated bone involvement has only rarely been reported.

Primary lymphoma of the bone and PTLD are my leading diagnoses in this patient. At this point, I recommend a bone marrow biopsy and biopsy of an easily accessible representative bone lesion with special staining for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) (EBV‐encoded RNA [EBER] and latent membrane protein 1 [LMP1]). I expect this test to provide a definitive diagnosis. As 95% of PTLD cases are induced by infection with EBV, information regarding pretransplantation EBV status of the patient and the donor, current EBV status of the patient, and type and intensity of immunosuppression at the time of transplantation would be very helpful to determine their likelihood.

Seventy‐two hours after presentation, his serum calcium level normalized and most of his symptoms improved. Calcitonin was discontinued, and he was maintained on oral hydration. On hospital day number 5, he underwent CT‐guided bone biopsy of the L4 vertebral body, which showed large aggregates of atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2). These cells were predominantly B‐cells interspersed with small reactive T‐cells. The cells did not express EBV LMP1 or EBER (Figure 3). On hospital day 7, he underwent a bone marrow biopsy, which revealed similar large atypical lymphoid cells that comprised the majority of marrow space (Figure 4). By immunohistochemistry, these cells brightly expressed the pan B cell marker, CD20, and coexpressed bcl‐2. EBER and LMP1 were also negative. A flow cytometry of the bone marrow demonstrated a lambda light chain restriction within the B lymphocytes.

The medical records indicated that the patient had positive pretransplantation EBV serologies. He received a regimen based on sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone, and did not receive high doses of induction or maintenance immunosuppressive therapy.

The biopsy results establish a diagnosis of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma of the bone. PTLD is unlikely given his positive pretransplantation EBV status, the late onset of his disease (6 years after transplantation), the isolated bone involvement, and the negative EBER and LMP1 tests.

The patient was discharged and was readmitted 1 week later for induction chemotherapy with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone [EPOCH]Rituxan (rituximab). Over the next several months, he received 6 cycles of chemotherapy, his hypercalcemia resolved, and his back pain improved.

Commentary

Hypercalcemia is among the most common causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults.1 A urinary concentrating defect usually becomes clinically apparent if the plasma calcium concentration is persistently above 11 mg/dL.1 This defect is generally reversible with correction of the hypercalcemia but may persist in patients in whom interstitial nephritis has induced permanent medullary damage. The mechanism by which the concentrating defect occurs is incompletely understood but may be related to impairments in sodium chloride reabsorption in the thick ascending limb and in the ability of antidiuretic hormone to increase water permeability in the collecting tubules.1

Although hypercalcemia in otherwise healthy outpatients is usually due to primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy is more often responsible for hypercalcemia in hospitalized patients.2 While the signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia are similar regardless of the cause, several clinical features may help distinguish the etiology of hypercalcemia. For instance, the presence of tachycardia, warm skin, thinning of the hair, stare and lid lag, and widened pulse pressure points toward hypercalcemia related to hyperthyroidism. In addition, risk factors and comorbidities guide the diagnostic process. For example, low‐level hypercalcemia in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with a normal physical examination suggests primary hyperparathyroidism. In contrast, hypercalcemia in a transplant patient raises concern of malignancy including PTLDs.3, 4

PTLDs are uncommon causes of hypercalcemia but are among the most serious and potentially fatal complications of chronic immunosuppression in transplant recipients.5 They occur in 1.9% of patients after kidney transplantation. The lymphoproliferative disorders occurring after transplantation have different characteristics from those that occur in the general population. Non‐Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for 65% of lymphomas in the general population, compared to 93% in transplant recipients.5, 6 The pathogenesis of PTLD appears to be related to B cell proliferation induced by infection with EBV in the setting of chronic immunosuppression.6 Therefore, there is an increased frequency of PTLD among transplant recipients who are EBV seronegative at the time of operation. These patients, who have no preoperative immunity to EBV, usually acquire the infection from the donor. The level of immunosuppression (intensity and type) influences PTLD rates as well. The disease typically occurs within 12 months after transplantation and in two‐thirds of cases involves extranodal sites. Among these sites, the gastrointestinal tract is involved in about 26% of cases and central nervous system in about 27%. Isolated bone involvement is exceedingly rare.5, 6

Primary lymphoma of the bone is another rare cause of hypercalcemia and accounts for less than 5% of all primary bone tumors.7 The majority of cases are of the non‐Hodgkin's type, characterized as diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas, with peak occurrence in the sixth to seventh decades of life.8 The classic imaging findings of primary lymphoma of the bone are a solitary metadiaphyseal lesion with a layered periosteal reaction on plain radiographs, and corresponding surrounding soft‐tissue mass on MRI.9 Less commonly, primary lymphoma of the bone can be multifocal with diffuse osseous involvement and variable radiographic appearances, as in this case. Most series have reported that the long bones are affected most frequently (especially the femur), although a large series showed equal numbers of cases presenting in the long bones and the spine.712

In order to diagnose primary lymphoma of the bone, it is necessary to exclude nodal or disseminated disease by physical examination and imaging. As plain films are often normal, bone scan or MRI of clinically affected areas is necessary to establish disease extent.9 Distinguishing primary bone lymphomas (PLB) from other bone tumors is important because PLB has a better response to therapy and a better prognosis.10, 11

Randomized trials addressing treatment options for primary lymphoma of bone are not available. Historically, PLB was treated with radiotherapy alone with good local control. However, the rate of distant relapses was relatively high. Currently, chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy is preferred; 5‐year survival is approximately 70% after combined therapy.10, 11

In this case, symptomatic hypercalcemia, a history of transplantation, marked elevation of both LDH and B2M, and a normal PTH level all pointed toward the correct diagnosis of malignancy. Low or normal levels of vitamin D metabolites and PTH‐related protein occur in 20% of patients with hypercalcemia caused by malignancy.13, 14 Diffuse osteopenia on skeletal survey is a prominent feature of renal osteodystrophy or osteoporosis related to chronic corticosteroid use. However, in a patient with diffuse osteopenia and hypercalcemia, clinicians must consider multiple myeloma and other lymphoproliferative disorders; the absence of osteoblastic or osteolytic lesions and a normal alkaline phosphatase do not rule out these diagnoses. When the results of serum and urine protein electrophoresis exclude multiple myeloma, the next investigation should be a bone biopsy to exclude PLB, an uncommon cause of anemia, hypercalcemia, and osteopenic, painful bones.

Key Points for Hospitalists

-

Normal total alkaline phosphatase does not exclude primary or metastatic bone malignancy. While a normal level tends to predict a negative bone scan, further diagnostic tests are needed to exclude bone malignancy if high clinical suspicion exists.

-

The degree of hypercalcemia is useful diagnostically; values above 13 mg/dL are most often due to malignancy.

-

Hypercalcemia in transplant patients deserves special attention due to an increased risk of malignancy, including squamous cancers of the lips and skin, lymphoproliferative disorders, and bronchogenic carcinoma.

-

While rare, consider primary lymphoma of the bone in patients with hypercalcemia and bone pain, along with the more common diagnoses of multiple myeloma and metastatic bone disease.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring the patient and the discussant.

A 71‐year‐old man presented to a hospital with a one week history of fatigue, polyuria, and polydipsia. He also reported pain in his back, hips, and ribs, in addition to frequent falls, intermittent confusion, constipation, and a weight loss of 10 pounds over the last 2 weeks. He denied cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, fever, night sweats, headache, and focal weakness.

Polyuria, which is often associated with polydipsia, can be arbitrarily defined as a urine output exceeding 3 L per day. After excluding osmotic diuresis due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, the 3 major causes of polyuria are primary polydipsia, central diabetes insipidus, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Approximately 30% to 50% of cases of central diabetes insipidus are idiopathic; however, primary or secondary brain tumors or infiltrative diseases involving the hypothalamic‐pituitary region need to be considered in this 71‐year‐old man. The most common causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in adults are chronic lithium ingestion, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia. The patient describes symptoms that can result from severe hypercalcemia, including fatigue, confusion, constipation, polyuria, and polydipsia.

The patient's past medical history included long‐standing, insulin‐requiring type 2 diabetes with associated complications including coronary artery disease, transient ischemic attacks, proliferative retinopathy, peripheral diabetic neuropathy, and nephropathy. Seven years prior to presentation, he received a cadaveric renal transplant that was complicated by BK virus (polyomavirus) nephropathy and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Three years after his transplant surgery, he developed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, which was treated with local surgical resection. Two years after that, he developed stage I laryngeal cancer of the glottis and received laser surgery, and since then he had been considered disease‐free. He also had a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, osteoporosis, and depression. His medications included aspirin, amlodipine, metoprolol succinate, valsartan, furosemide, simvastatin, insulin, prednisone, sirolimus, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. He was a married psychiatrist. He denied tobacco use and reported occasional alcohol use.

The prolonged immunosuppressive therapy that is required following organ transplantation carries a markedly increased risk of the subsequent development of malignant tumors, including cancers of the lips and skin, lymphoproliferative disorders, and bronchogenic carcinoma. Primary brain lymphoma resulting in central diabetes insipidus would be unlikely in the absence of headache or focal weakness. An increased risk of lung cancer occurs in recipients of heart and lung transplants, and to a much lesser degree, recipients of kidney transplants. However, metastatic lung cancer is less likely in the absence of respiratory symptoms and smoking history (present in approximately 90% of all lung cancers). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, in its mild form, is relatively common in elderly patients with acute or chronic renal insufficiency because of a reduction in maximum urinary concentrating ability. On the other hand, this alone does not explain his remaining symptoms. The instinctive diagnosis in this case is tertiary hyperparathyroidism due to progression of untreated secondary hyperparathyroidism. This causes hypercalcemia, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and significant bone pain related to renal osteodystrophy.

On physical exam, the patient appeared chronically ill, but was in no acute distress. He weighed 197.6 pounds and his height was 70.5 inches. He was afebrile with a blood pressure of 146/82 mm Hg, a heart rate of 76 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 97% while breathing room air. He had no generalized lymphadenopathy. Thyroid examination was unremarkable. Examination of the lungs, heart, abdomen, and lower extremities was normal. The rectal examination revealed no masses or prostate nodules; a test for fecal occult blood was negative. He had loss of sensation to light touch and vibration in the feet with absent Achilles deep tendon reflexes. He had a poorly healing surgical wound on his forehead at the site of his prior skin cancer, but no rash or other lesions. There was no joint swelling or erythema. There were tender points over the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine; on multiple ribs; and on the pelvic rims.

Perhaps of greatest importance is the lack of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or other findings suggestive of diffuse lymphoproliferative disease. His multifocal bone tenderness is concerning for renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, or primary or metastatic bone disease. Cancers in men that metastasize to the bone usually originate from the prostate, lung, kidney, or thyroid gland. In any case, his physical examination did not reveal an enlarged, asymmetric, or nodular prostate or thyroid gland. I recommend a chest film to rule out primary lung malignancy and a basic laboratory evaluation to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

A complete blood count showed a normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL and a hematocrit of 25%. Other laboratory tests revealed the following values: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.1 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen, 70 mg/dL; creatinine, 3.5 mg/dL (most recent value 2 months ago was 1.9 mg/dL); total calcium, 13.2 mg/dL (normal range, 8.5‐10.5 mg/dL); phosphate, 5.3 mg/dL; magnesium, 2.5 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 0.5 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 130 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 28 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 19 U/L; albumin, 3.5 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 1258 IU/L (normal range, 105‐333 IU/L). A chest radiograph was normal.

The most important laboratory findings are severe hypercalcemia, acute on chronic renal failure, and anemia. Hypercalcemia most commonly results from malignancy or hyperparathyroidism. Less frequently, hypercalcemia may result from sarcoidosis, vitamin D intoxication, or hyperthyroidism. The degree of hypercalcemia is useful diagnostically as hyperparathyroidism commonly results in mild hypercalcemia (serum calcium concentration often below 11 mg/dL). Values above 13 mg/dL are unusual in hyperparathyroidism and are most often due to malignancy. Malignancy is often evident clinically by the time it causes hypercalcemia, and patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy are more often symptomatic than those with hyperparathyroidism. Additionally, localized bone pain and weight loss do not result from hypercalcemia itself and their presence also raises concern for malignancy.

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer occurring after transplantation but does not cause hypercalcemia. Squamous cancers of the head and neck can rarely cause hypercalcemia due to secretion of parathyroid hormone‐related peptide; however, his early‐stage laryngeal cancer and the expected high likelihood of cure argue against this possibility. Osteolytic metastases account for approximately 20% of cases of hypercalcemia of malignancy (Table 1). Prostate cancer rarely results in hypercalcemia since bone metastases are predominantly osteoblastic, whereas metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer, thyroid cancer, and kidney cancer more commonly cause hypercalcemia due to osteolytic bone lesions. The total alkaline phosphatase has been traditionally used to assess the osteoblastic component of bone remodeling. Its normal level tends to predict a negative bone scan and supports the likelihood of lytic lesions. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders, which include a wide range of syndromes, can rarely result in hypercalcemia. I am also worried about the possibility of multiple myeloma as he has the classic triad of hypercalcemia, bone pain, and subacute kidney injury.

|

| Osteolytic metastases |

| Breast cancer |

| Multiple myeloma |

| Lymphoma |

| Leukemia |

| Humoral hypercalcemia (PTH‐related protein) |

| Squamous cell carcinomas |

| Renal carcinomas |

| Bladder carcinoma |

| Breast cancer |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Leukemia |

| Lymphoma |

| 1,25‐Dihydroxyvitamin D secretion |

| Lymphoma |

| Ovarian dysgerminomas |

| Ectopic PTH secretion (rare) |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Lung carcinomas |

| Neuroectodermal tumor |

| Thyroid papillary carcinoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Pancreatic cancer |