User login

What is your diagnosis?

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

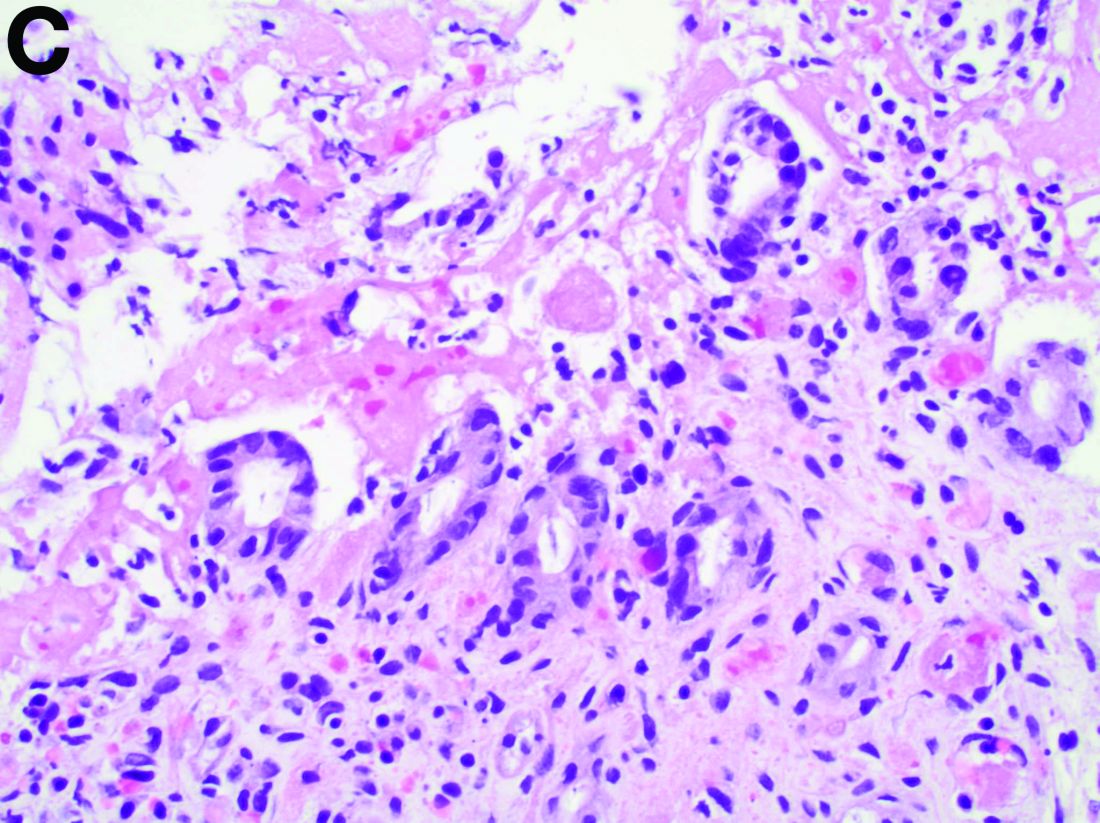

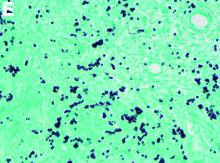

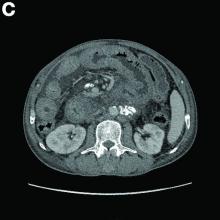

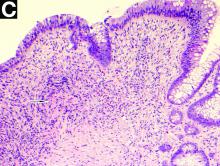

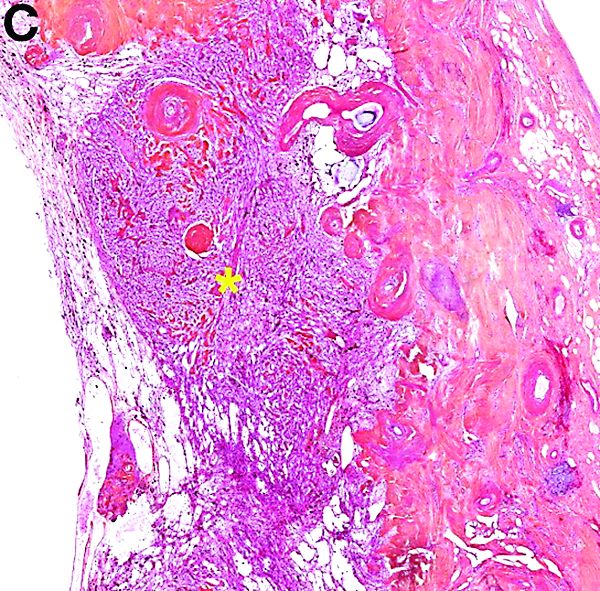

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

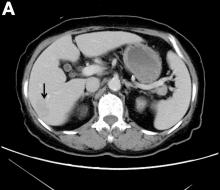

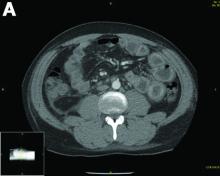

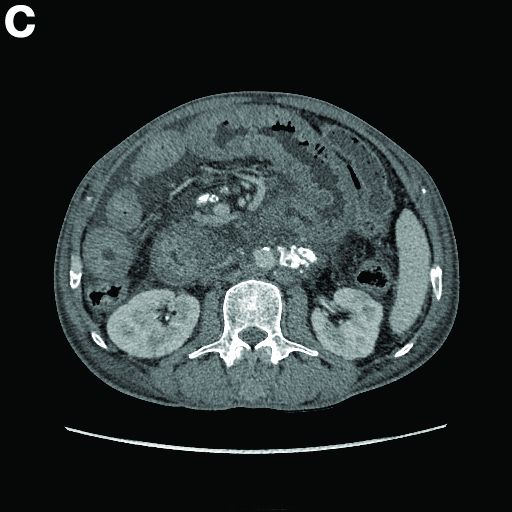

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

What was the diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis?

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

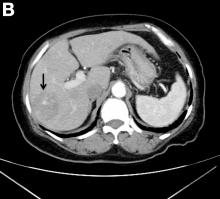

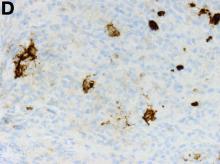

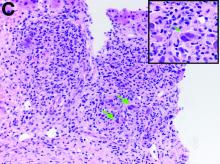

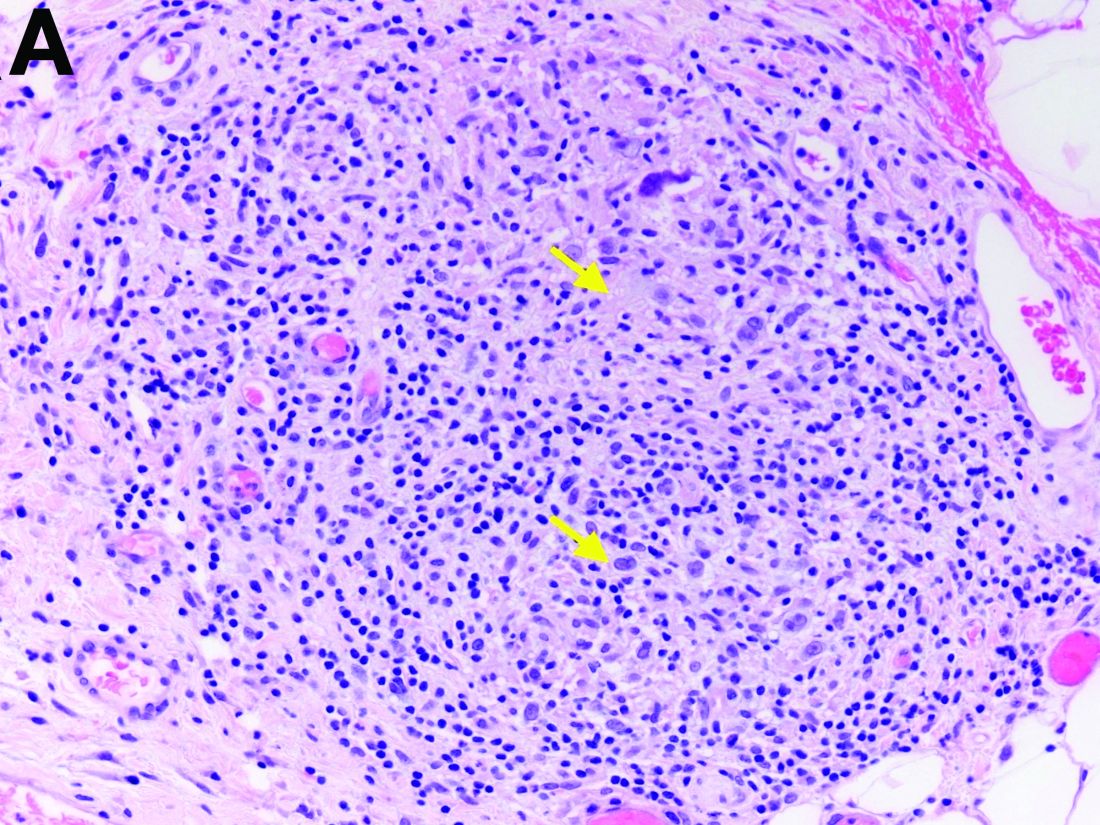

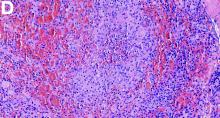

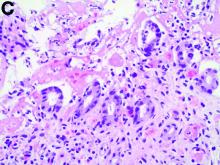

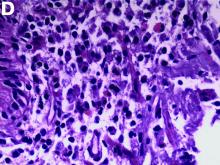

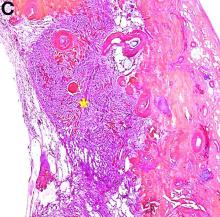

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

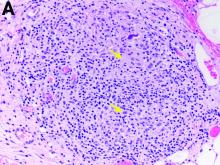

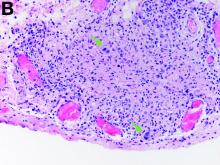

Two months later, repeat laboratory tests showed aspartate aminotransferase of 213 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 93 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 1,472 U/L, and total bilirubin of 6.0 mg/dL. The initial ultrasound scan was normal. On further assessment, she complained of malaise, weight loss, shortness of breath, dry eyes, dry mouth, and insomnia. She denied any significant alcohol use. No new medications or supplements were started recently. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination was unremarkable. Viral hepatitis serologies were negative. Antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and antimitochondrial antibody were negative. She had a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which showed splenomegaly but was otherwise unremarkable. She had a liver biopsy (Figure A), which showed non-necrotizing granulomas (yellow arrows) with a chronic inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate.

Given these findings, prednisone was increased to 20 mg. In the interim, the patient was admitted with acute acalculous cholecystitis. She had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and an intraoperative liver biopsy. She developed respiratory failure postoperatively and was transferred to intensive care. Stress dose steroids and antibiotics were initiated. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 13.8 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL, platelets at 223 × 109/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 97 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 63 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 1,607 U/L, total bilirubin of 5.8 mg/dL (direct 3.3), and albumin of 2.4 g/dL. Pathology from the gallbladder (Figure B) and the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C) showed cells pathognomonic for the condition (green arrows).

On the basis of these findings, what is the final diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - November 2019

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

An 18-year-old man presented with feverish cervical swelling that had developed over a few weeks.

He had a prior history of severe Crohn's disease with perianal manifestation with spontaneous perforation and had required an ileocecal and jejunal resection 3 years before. Clinical remission was achieved after 1 year of combination therapy by infliximab and azathioprine, followed by infliximab alone.

Physical examination showed an elevated body temperature of 38.5°C, and cervical palpation identified 3 painful erythematous nodes (3 cm in the left level IIb; 1 cm in the right IIb; 1 cm right supraclavicular space; Figure A). The rest of the examination was normal, and he did not complain about his bowel movements. He stated that he had not been traveling recently, nor had he been in contact with any sick person.

Laboratory tests spotted elevated levels of C-reactive protein (95.5 mg/L). Interferon-gamma release assays QuantiFERON-TB Gold was normal. Fine-needle aspiration showed a purulent content with repeated bacteriologic culture and gram stain culture, both of which were negative. Specific culture and polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative as well.

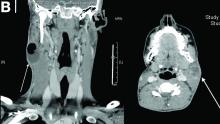

On computed tomography scan, the lymphadenitis showed liquid content with peripheral enhancement. One had an air-fluid level because of a spontaneous fistulization (Figure B). There were neither pulmonary abnormalities, mediastinal adenopathy, nor signs of Crohn's disease activity.

Histologic analysis of a lymph node excision showed epithelioid cell granuloma with noncaseous necrosis (Figure C, D).

Because the patient underwent anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy and despite the negative specific testing for tuberculosis, he was treated with probabilistic antituberculosis drugs for 6 months. Treatment proved ineffective and the patient's condition evolved with further fistulization and node size increase.

Considering the patient's medical history and evolution, what treatment should we consider, and what is the diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - October 2019

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

A 28-year-old woman with a history of mild iron-deficiency anemia presented with acute onset of lower abdominal pain and bloody bowel movements. The patient reported actively training for a marathon and on the day of presentation she ran approximately 20 miles before developing acute sharp, crampy lower abdominal pain. This discomfort forced her to stop her run early and she subsequently had several loose bowel movements streaked with bright red blood that prompted evaluation.

In the emergency department, she was afebrile and hemodynamically stable with physical examination revealing slight tenderness to palpation in the left upper quadrant of her abdomen. Laboratory results were significant for mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.1 × 103/microL), anemia (hemoglobin, 10.3 g/dL), and iron deficiency (ferritin, 14 ng/mL; iron, 11 microg/dL; and iron saturation, 2%). Of note, lactate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels were all within normal limits.

What is your diagnosis? - September 2019

Erosive protein-losing enteropathy secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis

This patient was treated with amphotericin B and transitioned to oral itraconazole with frequent blood level monitoring to ensure absorption. His symptoms improved gradually. Small-bowel enteroscopy 3 weeks after presentation showed a normal duodenum and healing, superficial ulcers in the proximal jejunum (Figure F, G). Blood albumin levels had recovered to 3.1 g/dL (normal, 3.5–5.0 g/dL).

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome characterized by loss of serum proteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in significant hypoproteinemia and consequent edema.1 PLE can also result in ascites, pleural and pericardial effusions, and, in prolonged cases, malnutrition. There are a variety of causes of PLE that can be broadly grouped into erosive GI disorders, disorders of increased GI mucosal permeability, and disorders of increased interstitial pressure. The clinical presentation depends on the underlying etiology, but commonly includes generalized edema owing to hypoproteinemia and resulting reduced oncotic pressure. GI symptoms are not frequently observed. The initial step in evaluating a patient with symptoms concerning for PLE is to rule out more common causes of hypoproteinemia, such as renal or hepatic disease, and malnutrition. To confirm enteric protein loss, alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance with a 24-hour stool collection is commonly and reliably used. Treatment of PLE is centered on treating the underlying cause while monitoring and treating malnutrition, including micronutrient deficiencies.

Fungal infections are a rare cause of PLE, but important to recognize as a potential complication of tumor necrosis factor–therapy, because these medications are commonly used for a variety of autoimmune diseases.2 Although histoplasmosis is an uncommon cause of GI inflammation, disseminated histoplasmosis causing PLE has been previously reported.3 In our patient, Histoplasma capsulatum infection caused diffuse GI ulcers, which allowed protein loss in the GI tract (erosive PLE). Antifungal treatment resulted in healing of intestinal ulcers and correction of hypoalbuminemia, thereby confirming the diagnosis of PLE and obviating the need for a confirmatory alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance study.

References

1. Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:43-9.

2. Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT. et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-94.

3. Kok J, Chen SC, Anderson L, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy and hypogammaglobulinaemia as first manifestations of disseminated histoplasmosis coincident with Nocardia infection. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:610-3.

Erosive protein-losing enteropathy secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis

This patient was treated with amphotericin B and transitioned to oral itraconazole with frequent blood level monitoring to ensure absorption. His symptoms improved gradually. Small-bowel enteroscopy 3 weeks after presentation showed a normal duodenum and healing, superficial ulcers in the proximal jejunum (Figure F, G). Blood albumin levels had recovered to 3.1 g/dL (normal, 3.5–5.0 g/dL).

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome characterized by loss of serum proteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in significant hypoproteinemia and consequent edema.1 PLE can also result in ascites, pleural and pericardial effusions, and, in prolonged cases, malnutrition. There are a variety of causes of PLE that can be broadly grouped into erosive GI disorders, disorders of increased GI mucosal permeability, and disorders of increased interstitial pressure. The clinical presentation depends on the underlying etiology, but commonly includes generalized edema owing to hypoproteinemia and resulting reduced oncotic pressure. GI symptoms are not frequently observed. The initial step in evaluating a patient with symptoms concerning for PLE is to rule out more common causes of hypoproteinemia, such as renal or hepatic disease, and malnutrition. To confirm enteric protein loss, alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance with a 24-hour stool collection is commonly and reliably used. Treatment of PLE is centered on treating the underlying cause while monitoring and treating malnutrition, including micronutrient deficiencies.

Fungal infections are a rare cause of PLE, but important to recognize as a potential complication of tumor necrosis factor–therapy, because these medications are commonly used for a variety of autoimmune diseases.2 Although histoplasmosis is an uncommon cause of GI inflammation, disseminated histoplasmosis causing PLE has been previously reported.3 In our patient, Histoplasma capsulatum infection caused diffuse GI ulcers, which allowed protein loss in the GI tract (erosive PLE). Antifungal treatment resulted in healing of intestinal ulcers and correction of hypoalbuminemia, thereby confirming the diagnosis of PLE and obviating the need for a confirmatory alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance study.

References

1. Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:43-9.

2. Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT. et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-94.

3. Kok J, Chen SC, Anderson L, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy and hypogammaglobulinaemia as first manifestations of disseminated histoplasmosis coincident with Nocardia infection. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:610-3.

Erosive protein-losing enteropathy secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis

This patient was treated with amphotericin B and transitioned to oral itraconazole with frequent blood level monitoring to ensure absorption. His symptoms improved gradually. Small-bowel enteroscopy 3 weeks after presentation showed a normal duodenum and healing, superficial ulcers in the proximal jejunum (Figure F, G). Blood albumin levels had recovered to 3.1 g/dL (normal, 3.5–5.0 g/dL).

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome characterized by loss of serum proteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in significant hypoproteinemia and consequent edema.1 PLE can also result in ascites, pleural and pericardial effusions, and, in prolonged cases, malnutrition. There are a variety of causes of PLE that can be broadly grouped into erosive GI disorders, disorders of increased GI mucosal permeability, and disorders of increased interstitial pressure. The clinical presentation depends on the underlying etiology, but commonly includes generalized edema owing to hypoproteinemia and resulting reduced oncotic pressure. GI symptoms are not frequently observed. The initial step in evaluating a patient with symptoms concerning for PLE is to rule out more common causes of hypoproteinemia, such as renal or hepatic disease, and malnutrition. To confirm enteric protein loss, alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance with a 24-hour stool collection is commonly and reliably used. Treatment of PLE is centered on treating the underlying cause while monitoring and treating malnutrition, including micronutrient deficiencies.

Fungal infections are a rare cause of PLE, but important to recognize as a potential complication of tumor necrosis factor–therapy, because these medications are commonly used for a variety of autoimmune diseases.2 Although histoplasmosis is an uncommon cause of GI inflammation, disseminated histoplasmosis causing PLE has been previously reported.3 In our patient, Histoplasma capsulatum infection caused diffuse GI ulcers, which allowed protein loss in the GI tract (erosive PLE). Antifungal treatment resulted in healing of intestinal ulcers and correction of hypoalbuminemia, thereby confirming the diagnosis of PLE and obviating the need for a confirmatory alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance study.

References

1. Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:43-9.

2. Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT. et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-94.

3. Kok J, Chen SC, Anderson L, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy and hypogammaglobulinaemia as first manifestations of disseminated histoplasmosis coincident with Nocardia infection. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:610-3.

A 34-year-old man with a medical history of psoriasis, on adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of progressively worsening abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, melenic diarrhea, subjective fevers, and generalized weakness. One week into the illness, he developed progressive bilateral extremity and scrotal swelling.

His vital signs included a temperature of 36.8°C, heart rate of 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and a blood pressure of 114/71 mm Hg. The physical examination was notable for a well-nourished appearance, diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without distension, organomegaly, or rigidity, and pitting lower extremity edema.

Laboratory evaluation showed hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL (normal, 13.5–17.5 g/dL), leukocytes 10 × 109/L (normal, 3.5–10.5 × 109/L), platelets 212 × 109/L (normal, 150–450 × 109/L), sodium 131 mmol/L (normal, 135–145 mmol/L), creatinine 1 mg/dL (normal, 0.8–1.3 mg/dL), albumin 1.8 g/dL (normal, 3.5–5.0 g/dL), and C-reactive protein 53 mg/L (normal, less than 8 mg/L). Liver chemistries were all normal.

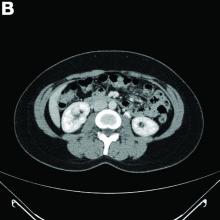

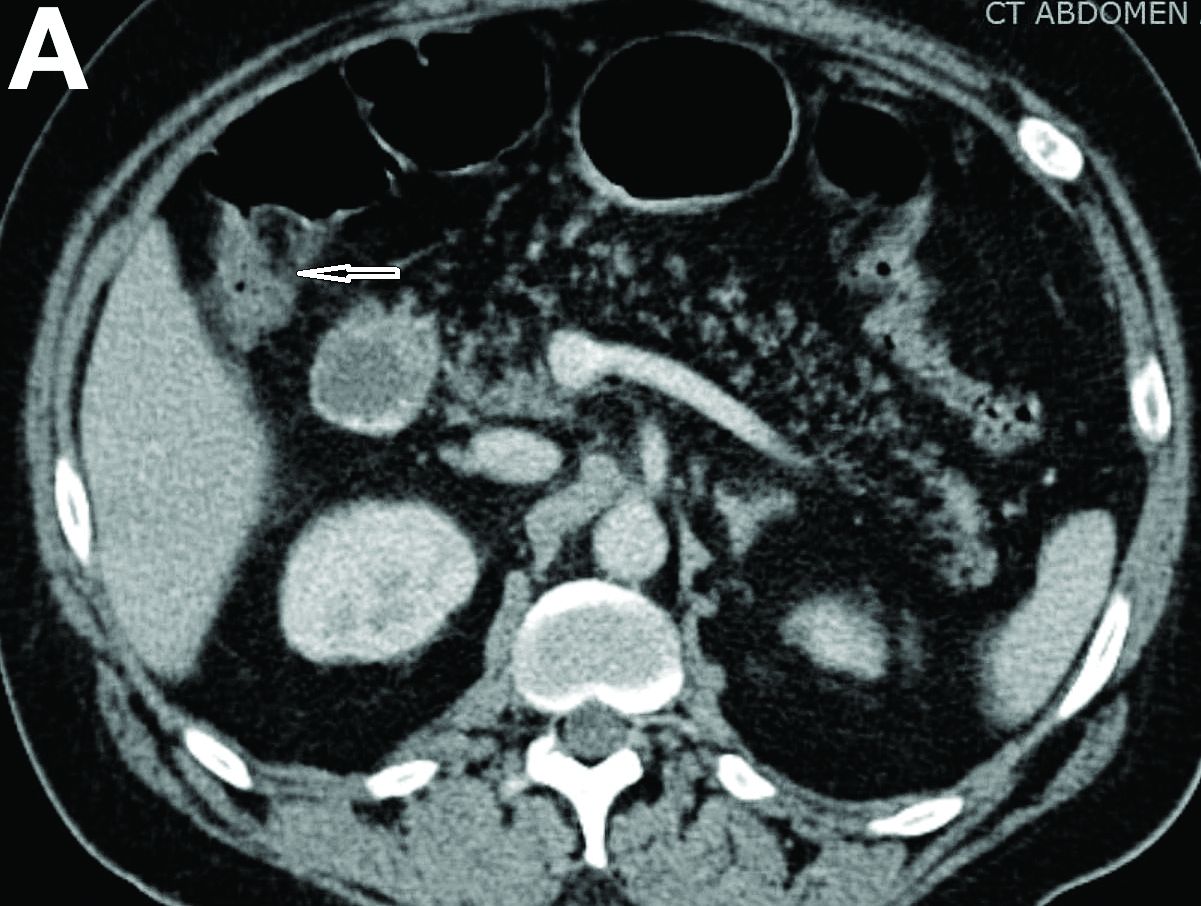

Urinalysis was unremarkable with normal urine protein levels. The enteric pathogen panel by polymerase chain reaction was negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed marked circumferential wall thickening with mural enhancement of multiple loops of jejunum (Figure A).

Small-bowel enteroscopy showed diffuse erosions in the entire duodenum and many oozing superficial ulcers with edematous and erythematous mucosa in the proximal jejunum (Figures B, C).

CT scan of the chest showed right lower lobe consolidation associated with a large right pleural effusion, and mediastinal, bilateral, hilar and abdominal lymphadenopathy (Figure D). Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy of lymph nodes was positive for oval-shaped organisms exhibiting narrow-based budding on GMS stain (Figure E).

Based on the clinical scenario and images, what is the most likely diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - July 2019

The diagnosis

von Hippel-Lindau disease

The diagnosis is von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL). Subsequent brain and renal magnetic resonance imaging showed features suggestive of a 5-mm right cerebellar hemangioblastoma and right renal cell carcinoma (RCC), respectively. Fundoscopy showed bilateral small retinal angiomas. Plasma and 24-hour urinary metenephrine levels were normal. Genetic testing confirmed a germline VHL mutation.

VHL is a rare autosomal-dominant hereditary multicancer condition characterized by germline mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene, with an incidence of 1 in 36,000 live births. The commonest associated tumors are retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas, RCC, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic islet cell tumors, and endolymphatic sac tumors.1 Cystic lesions may also be seen in other viscera such as the liver and ovaries. Clinical diagnostic criteria require the presence of any of these tumors in a patient with a positive family history, or alternatively, at least 2 retinal or cerebellar hemangioblastomas, or 1 hemangioblastoma plus 1 visceral tumor.2

Pancreatic involvement occurs in 65%–77% of patients with VHL, and may be the sole manifestation in 7.6%. Findings include multiple true cysts (91%), microcystic serous cystadenomas (12%), solid pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (5%–10%), or a combination (11.5%). Most lesions are asymptomatic, but may present with vague symptoms of epigastric pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, obstructive jaundice, or endocrine and/or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Surgery is required for symptomatic cysts or large pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The main causes of death are RCC and central nervous system hemangioblastomas.3 Our patient underwent laser therapy for her retinal angiomas, and is currently undergoing close regular surveillance. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for diagnosing VHL in patients with multiple pancreatic cysts. Because EUS is now widely used for the evaluation of pancreatic cysts, gastroenterologists may be first in making the diagnosis, as in this patient.

References

1. Lonser R.R., Glenn G.M., Walther M. et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059-67.

2. Melmon K., Rosen S. Lindau’s disease. Am J Med. 1964;36:595-617

3. Hammel P.R., Vilgrain V., Terris B. et al. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d’Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1087-95.

The diagnosis

von Hippel-Lindau disease

The diagnosis is von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL). Subsequent brain and renal magnetic resonance imaging showed features suggestive of a 5-mm right cerebellar hemangioblastoma and right renal cell carcinoma (RCC), respectively. Fundoscopy showed bilateral small retinal angiomas. Plasma and 24-hour urinary metenephrine levels were normal. Genetic testing confirmed a germline VHL mutation.

VHL is a rare autosomal-dominant hereditary multicancer condition characterized by germline mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene, with an incidence of 1 in 36,000 live births. The commonest associated tumors are retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas, RCC, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic islet cell tumors, and endolymphatic sac tumors.1 Cystic lesions may also be seen in other viscera such as the liver and ovaries. Clinical diagnostic criteria require the presence of any of these tumors in a patient with a positive family history, or alternatively, at least 2 retinal or cerebellar hemangioblastomas, or 1 hemangioblastoma plus 1 visceral tumor.2

Pancreatic involvement occurs in 65%–77% of patients with VHL, and may be the sole manifestation in 7.6%. Findings include multiple true cysts (91%), microcystic serous cystadenomas (12%), solid pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (5%–10%), or a combination (11.5%). Most lesions are asymptomatic, but may present with vague symptoms of epigastric pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, obstructive jaundice, or endocrine and/or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Surgery is required for symptomatic cysts or large pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The main causes of death are RCC and central nervous system hemangioblastomas.3 Our patient underwent laser therapy for her retinal angiomas, and is currently undergoing close regular surveillance. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for diagnosing VHL in patients with multiple pancreatic cysts. Because EUS is now widely used for the evaluation of pancreatic cysts, gastroenterologists may be first in making the diagnosis, as in this patient.

References

1. Lonser R.R., Glenn G.M., Walther M. et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059-67.

2. Melmon K., Rosen S. Lindau’s disease. Am J Med. 1964;36:595-617

3. Hammel P.R., Vilgrain V., Terris B. et al. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d’Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1087-95.

The diagnosis

von Hippel-Lindau disease

The diagnosis is von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL). Subsequent brain and renal magnetic resonance imaging showed features suggestive of a 5-mm right cerebellar hemangioblastoma and right renal cell carcinoma (RCC), respectively. Fundoscopy showed bilateral small retinal angiomas. Plasma and 24-hour urinary metenephrine levels were normal. Genetic testing confirmed a germline VHL mutation.

VHL is a rare autosomal-dominant hereditary multicancer condition characterized by germline mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene, with an incidence of 1 in 36,000 live births. The commonest associated tumors are retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas, RCC, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic islet cell tumors, and endolymphatic sac tumors.1 Cystic lesions may also be seen in other viscera such as the liver and ovaries. Clinical diagnostic criteria require the presence of any of these tumors in a patient with a positive family history, or alternatively, at least 2 retinal or cerebellar hemangioblastomas, or 1 hemangioblastoma plus 1 visceral tumor.2

Pancreatic involvement occurs in 65%–77% of patients with VHL, and may be the sole manifestation in 7.6%. Findings include multiple true cysts (91%), microcystic serous cystadenomas (12%), solid pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (5%–10%), or a combination (11.5%). Most lesions are asymptomatic, but may present with vague symptoms of epigastric pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, obstructive jaundice, or endocrine and/or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Surgery is required for symptomatic cysts or large pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The main causes of death are RCC and central nervous system hemangioblastomas.3 Our patient underwent laser therapy for her retinal angiomas, and is currently undergoing close regular surveillance. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for diagnosing VHL in patients with multiple pancreatic cysts. Because EUS is now widely used for the evaluation of pancreatic cysts, gastroenterologists may be first in making the diagnosis, as in this patient.

References

1. Lonser R.R., Glenn G.M., Walther M. et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059-67.

2. Melmon K., Rosen S. Lindau’s disease. Am J Med. 1964;36:595-617

3. Hammel P.R., Vilgrain V., Terris B. et al. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d’Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1087-95.

A 32-year-old Filipino woman was referred for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) imaging of the pancreas from another hospital where she had presented with a history of intermittent abdominal pain with radiation to the back precipitated by alcohol, and recurrent palpitations. During outpatient review before EUS, she gave a background history of previous laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy, as well as multiple previous admissions with supraventricular tachycardia requiring cardioversion on 1 occasion. One of her brothers had undergone brain surgery to remove a cyst, and another had died of an unspecified brain tumor at 25 years of age. Her mother had died of ovarian cancer.

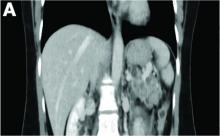

Physical examination was unremarkable, with a normal pulse rate and blood pressure and no anemia, jaundice, or lymphadenopathy. Laboratory investigations including a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, and serum lipase were all normal. Abdominal computed tomography and ultrasound imaging revealed multiple cysts of varying sizes throughout the pancreas (Figure A), as well as multiple small benign-looking cysts in the liver.

In addition, there was a 17-mm hyperdense solid lesion in the midpole of her right kidney visualized on computed tomography scan (Figure B). EUS revealed multiple thinly septated anechoic cysts throughout the pancreas, the largest measuring 36 mm located in the body, with no associated masses (Figure C).

What is the likely diagnosis? What other investigations would you do for confirmation?

What is your diagnosis? - June 2019

Multiple myeloma

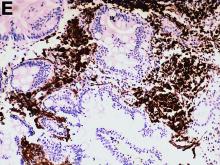

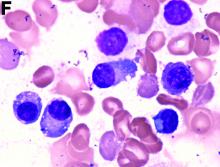

An abdominal CT scan (Figure D) showed gastric and whole intestinal wall thickening of up to 2 cm. Pathology (Figure E) demonstrated that diffuse plasmacytoid cells, eosinophilic granulocytes, and lymphocytes infiltrated into the lamina propria. Immunohistochemically, the plasmacytoid cells were positive for the common plasma cell marker CD38, and in situ hybridization indicated that they were kappa-Ig light-chain restricted (Figure F).

Results of the subsequent bone marrow aspirate revealed 27.5% atypical plasma cells. Serum electrophoresis and immunofixation showed an M spike of IgA-kappa. Together, these findings confirmed a final diagnosis of a multiple myeloma (MM) involving the whole gastrointestinal (GI) duct, which was the cause of his melena.

MM is a malignant hematologic neoplasm, primarily involving the bone marrow, and has a potent tendency to involve other organs and to present with various clinical manifestations.1

The clinical features of MM with GI involvement are uncommon. Patients may present with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, protein loss, malabsorption, intestinal obstruction, and hemorrhage. Endoscopic findings can manifest as four types: a discrete ulcer, ulcerating mass, thickening of the mucosal fold, and mucosal polyp.2

However, GI bleeding in MM has only been reported in a few patients. A biopsy reaching the submucosal layer and bone marrow biopsy is essential. Diagnosis of MM as a cause of the GI duct wall edema and multiple small intestinal polypoid ulcers is challenging. An interdisciplinary approach is mandatory to establish such a diagnosis.

References

1. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;3518:1860-73.

2. Karam AR, Semaan RJ, Buch K, et al. Extramedullary duodenal plasmacytoma presenting with gastric outlet obstruction and painless jaundice. Radiol Cases. 2010;4:22-8.

Multiple myeloma

An abdominal CT scan (Figure D) showed gastric and whole intestinal wall thickening of up to 2 cm. Pathology (Figure E) demonstrated that diffuse plasmacytoid cells, eosinophilic granulocytes, and lymphocytes infiltrated into the lamina propria. Immunohistochemically, the plasmacytoid cells were positive for the common plasma cell marker CD38, and in situ hybridization indicated that they were kappa-Ig light-chain restricted (Figure F).

Results of the subsequent bone marrow aspirate revealed 27.5% atypical plasma cells. Serum electrophoresis and immunofixation showed an M spike of IgA-kappa. Together, these findings confirmed a final diagnosis of a multiple myeloma (MM) involving the whole gastrointestinal (GI) duct, which was the cause of his melena.

MM is a malignant hematologic neoplasm, primarily involving the bone marrow, and has a potent tendency to involve other organs and to present with various clinical manifestations.1

The clinical features of MM with GI involvement are uncommon. Patients may present with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, protein loss, malabsorption, intestinal obstruction, and hemorrhage. Endoscopic findings can manifest as four types: a discrete ulcer, ulcerating mass, thickening of the mucosal fold, and mucosal polyp.2

However, GI bleeding in MM has only been reported in a few patients. A biopsy reaching the submucosal layer and bone marrow biopsy is essential. Diagnosis of MM as a cause of the GI duct wall edema and multiple small intestinal polypoid ulcers is challenging. An interdisciplinary approach is mandatory to establish such a diagnosis.

References

1. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;3518:1860-73.

2. Karam AR, Semaan RJ, Buch K, et al. Extramedullary duodenal plasmacytoma presenting with gastric outlet obstruction and painless jaundice. Radiol Cases. 2010;4:22-8.

Multiple myeloma

An abdominal CT scan (Figure D) showed gastric and whole intestinal wall thickening of up to 2 cm. Pathology (Figure E) demonstrated that diffuse plasmacytoid cells, eosinophilic granulocytes, and lymphocytes infiltrated into the lamina propria. Immunohistochemically, the plasmacytoid cells were positive for the common plasma cell marker CD38, and in situ hybridization indicated that they were kappa-Ig light-chain restricted (Figure F).

Results of the subsequent bone marrow aspirate revealed 27.5% atypical plasma cells. Serum electrophoresis and immunofixation showed an M spike of IgA-kappa. Together, these findings confirmed a final diagnosis of a multiple myeloma (MM) involving the whole gastrointestinal (GI) duct, which was the cause of his melena.

MM is a malignant hematologic neoplasm, primarily involving the bone marrow, and has a potent tendency to involve other organs and to present with various clinical manifestations.1

The clinical features of MM with GI involvement are uncommon. Patients may present with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, protein loss, malabsorption, intestinal obstruction, and hemorrhage. Endoscopic findings can manifest as four types: a discrete ulcer, ulcerating mass, thickening of the mucosal fold, and mucosal polyp.2

However, GI bleeding in MM has only been reported in a few patients. A biopsy reaching the submucosal layer and bone marrow biopsy is essential. Diagnosis of MM as a cause of the GI duct wall edema and multiple small intestinal polypoid ulcers is challenging. An interdisciplinary approach is mandatory to establish such a diagnosis.

References

1. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;3518:1860-73.

2. Karam AR, Semaan RJ, Buch K, et al. Extramedullary duodenal plasmacytoma presenting with gastric outlet obstruction and painless jaundice. Radiol Cases. 2010;4:22-8.

He denied experiencing hematemesis, abdominal pain, fever, osteodynia, or arthralgia. His medical history included a 6-year history of alcoholic hepatocirrhosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Colonoscopy found no evidence of hemorrhage.

What is the underlying condition leading to the endoscopic and CT findings?

What is your diagnosis? - May 2019

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

A 57-year-old man presented to our hospital with a week of generalized weakness and abdominal pain.

Relevant medications included diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, aspirin 81 mg, and clopidogrel 75 mg/d. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination showed mild diffuse abdominal tenderness.

Admission blood work revealed a hemoglobin of 8.8 g/dL, decreased from a baseline hemoglobin of 12 g/dL. The patient did not have overt gastrointestinal bleeding, but tested positive for fecal occult blood. A computed tomography scan demonstrated luminal narrowing at the hepatic flexure without bowel wall thickening or obstruction (Figure A). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was normal. Colonoscopy revealed a circumferential stricture in the right colon with an estimated diameter of 8 mm (Figure B).

Biopsies of the stricture showed significant lamina propria fibrosis, eosinophilic infiltration, and mild crypt distortion (Figure C).

What is your diagnosis? - April 2019

Cystic and calcified PEComa of the ligamentum teres

PEComas are tumors derived from epithelioid perivascular cells that typically coexpress smooth muscle and melanocytic markers. The family of PEComas includes angiomyolipoma, clear cell “sugar” tumor, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Some of these tumors may be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. PEComas of the ligamentum teres (also called in this location “clear cell myomelanocytic tumors”) are rare, but the ligamentum teres location is the most classic in children. Thirteen cases have been reported in the literature, within or in the immediate vicinity of falciform ligament/ligamentum teres.1-3 There was a marked female predominance with a mean age of 20 years (range, 3-54 years), a mean size of 8 cm (range, 5-20 cm), and a significant risk of metastasis (3 of 13 cases). Many of the lesions were calcified and had hemorrhagic and cystic alterations.

In the absence of established malignancy criteria, PEComas must be considered to have an uncertain malignant potential, requiring surgical resection and long-term monitoring. A mass of the ligamentum teres should always lead to consideration of the diagnosis of PEComa, even in adults, and even with cystic presentation. Moreover, most frequently, other tumors of the ligamentum teres are malignant (local extension of hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal or gynecological origin). The patient was free of disease at 6 months’ follow-up.

References

1. Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239-46.

2. Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-75.

3. Alaggio R, Cecchetto G, Martignoni G, et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in children: description of a case and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:31-40.

Cystic and calcified PEComa of the ligamentum teres

PEComas are tumors derived from epithelioid perivascular cells that typically coexpress smooth muscle and melanocytic markers. The family of PEComas includes angiomyolipoma, clear cell “sugar” tumor, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Some of these tumors may be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. PEComas of the ligamentum teres (also called in this location “clear cell myomelanocytic tumors”) are rare, but the ligamentum teres location is the most classic in children. Thirteen cases have been reported in the literature, within or in the immediate vicinity of falciform ligament/ligamentum teres.1-3 There was a marked female predominance with a mean age of 20 years (range, 3-54 years), a mean size of 8 cm (range, 5-20 cm), and a significant risk of metastasis (3 of 13 cases). Many of the lesions were calcified and had hemorrhagic and cystic alterations.

In the absence of established malignancy criteria, PEComas must be considered to have an uncertain malignant potential, requiring surgical resection and long-term monitoring. A mass of the ligamentum teres should always lead to consideration of the diagnosis of PEComa, even in adults, and even with cystic presentation. Moreover, most frequently, other tumors of the ligamentum teres are malignant (local extension of hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal or gynecological origin). The patient was free of disease at 6 months’ follow-up.

References

1. Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239-46.

2. Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-75.

3. Alaggio R, Cecchetto G, Martignoni G, et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in children: description of a case and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:31-40.

Cystic and calcified PEComa of the ligamentum teres

PEComas are tumors derived from epithelioid perivascular cells that typically coexpress smooth muscle and melanocytic markers. The family of PEComas includes angiomyolipoma, clear cell “sugar” tumor, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Some of these tumors may be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. PEComas of the ligamentum teres (also called in this location “clear cell myomelanocytic tumors”) are rare, but the ligamentum teres location is the most classic in children. Thirteen cases have been reported in the literature, within or in the immediate vicinity of falciform ligament/ligamentum teres.1-3 There was a marked female predominance with a mean age of 20 years (range, 3-54 years), a mean size of 8 cm (range, 5-20 cm), and a significant risk of metastasis (3 of 13 cases). Many of the lesions were calcified and had hemorrhagic and cystic alterations.

In the absence of established malignancy criteria, PEComas must be considered to have an uncertain malignant potential, requiring surgical resection and long-term monitoring. A mass of the ligamentum teres should always lead to consideration of the diagnosis of PEComa, even in adults, and even with cystic presentation. Moreover, most frequently, other tumors of the ligamentum teres are malignant (local extension of hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal or gynecological origin). The patient was free of disease at 6 months’ follow-up.

References

1. Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239-46.

2. Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-75.

3. Alaggio R, Cecchetto G, Martignoni G, et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in children: description of a case and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:31-40.

A laparoscopic resection of this mass was performed because of the risk of spontaneous hemorrhage linked to the dense tumoral vasculature and the lack of formal histologic diagnosis. During the procedure, the surgeon observed a cystic mass attached to the ligamentum teres between the liver and the umbilicus. At pathologic examination (Figure B), a well-circumscribed largely cystic mass, with a fibrous and calcified shell and hemorrhagic modifications (arrow) was observed.

What is your diagnosis? - March 2019

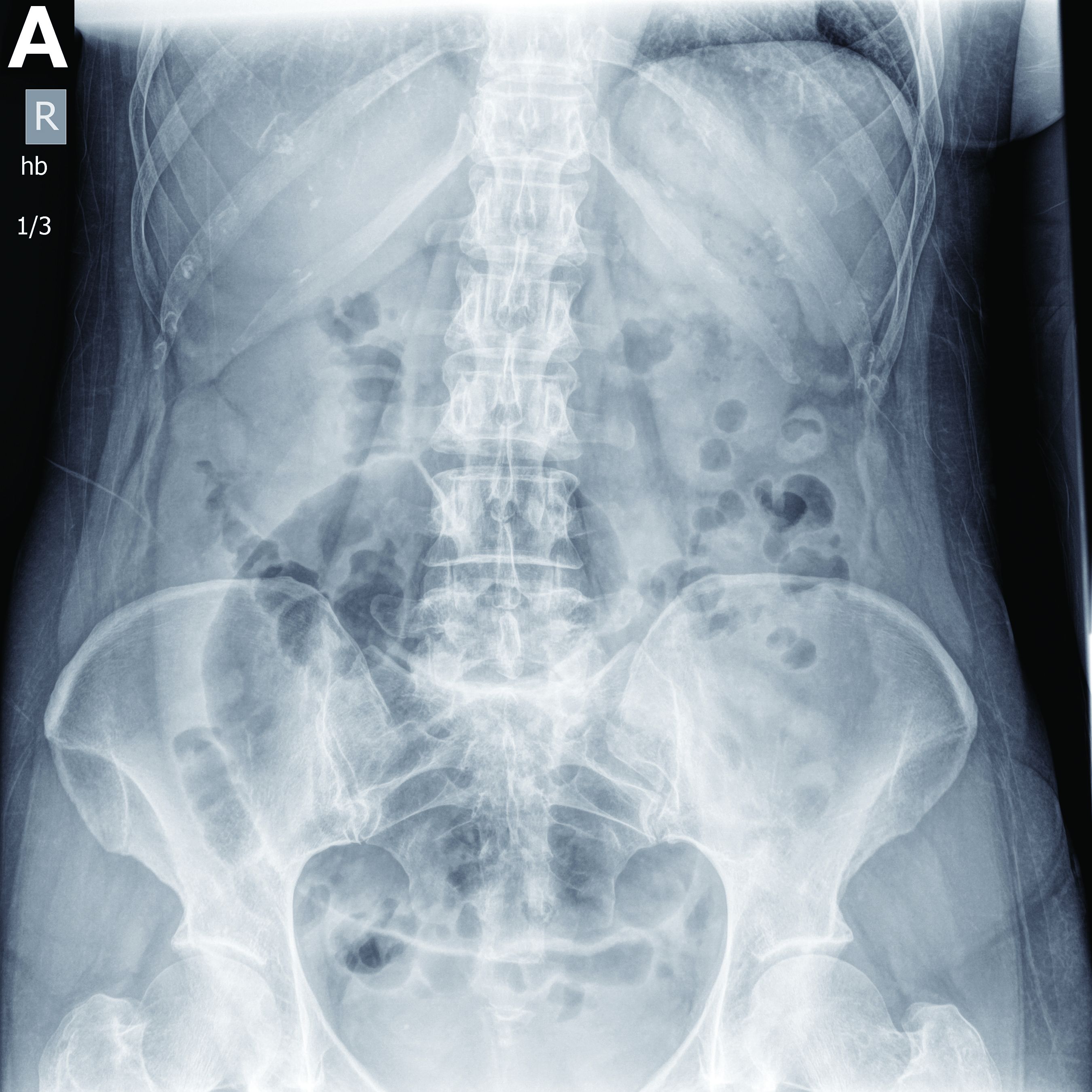

Partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy

The patient presented with partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy, which was confirmed by abdominal computed tomography scan. The patient gave consent and taken urgently to the operating room where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy and right hemicolectomy. Upon entering the abdomen, a mesenteroaxial cecal volvulus was noted immediately. The involved colon segment was dusky without frank necrosis. The distal ascending and proximal transverse colon were tethered to the left abdominal wall, and the ascending colon lacked its usual retroperitoneal attachments, consistent with partial malrotation. The adhesions were lysed, and a right hemicolectomy with primary side-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis was performed. The patient recovered well and was discharged to home on postoperative day 4.

Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer is a commonly performed procedure with an established survival benefit. Up to one-third of patients experience abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating afterward, which may last hours to several days. Fortunately, severe complications including hemorrhage, perforation, and death are rare, with a total incidence of 0.28%.1 Although abdominal pain is common after colonoscopy, severe pain that persists or worsens warrants investigation. Perforation is the most frequently encountered complication in this context, although splenic injury/rupture and intestinal obstruction do occur. Cecal volvulus is a very rare complication with few reports in the literature.2,3 Colonic malrotation, which occurs in up to 0.5% of the population, increases the risk of volvulus owing to a lack of retroperitoneal attachments. This diagnosis should be considered for patients with known risk factors for volvulus.

References

1. Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638-58.

2. Viney R, Fordan SV, Fisher WE, et al. Cecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3211-2.

3. Anderson JR, Spence RA, Wilson BG, et al. Gangrenous caecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:439-40.

Partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy