User login

Code Correctly

A hospitalist who scrutinizes claims might notice a payment denial related to “unbundling” issues. Line-item rejections might state the service is “mutually exclusive,” “incidental to another procedure,” or “payment was received as part of another service/procedure.” Unbundling refers to the practice of reporting each component of a service or procedure instead of reporting the single, comprehensive code. Two types of practices lead to unbundling: unintentional reporting resulting from a basic misunderstanding of correct coding, and intentional reporting to improperly maximize payment of otherwise bundled Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.1

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) for implementation and application to physician claims (e.g., Medicare Part B) with dates of service on or after Jan. 1, 1996. The rationale for these edits is a culmination of:

- Coding standards identified in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) CPT manual;

- National and local coverage determinations developed by CMS and local Medicare contractors;

- Coding standards set forth by national medical organizations and specialty societies;

- Appropriate standards of medical and surgical care; and

- Current coding practices identified through claim analysis, pre- and post-payment documentation reviews, and other forms of payor-initiated audit.

The initial NCCI goal was to promote correct coding methodologies and to control improper coding, which led to inappropriate payment in Part B claims.2 It later expanded to include corresponding NCCI edits in the outpatient code editor (OCE) for both outpatient hospital providers and therapy providers. Therapy providers encompass skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities (CORFs), outpatient physical therapy (OPTs) and speech-language pathology providers, and home health agencies (HHAs).

Fact-Check

The NCCI recognizes two edit types: Column One/Column Two Correct Coding edits and Mutually Exclusive edits. Each of these edit categories lists code pairs that should not be reported together on the same date by either a single physician or physicians of the same specialty within a provider group.

When applying Column One/Column Two editing logic to physician claims, the Column One code represents the more comprehensive code of the pair being reported. The Column Two code (the component service that is bundled into the comprehensive service) will be denied. This is not to say a code that appears in Column Two of the NCCI cannot be paid when reported by itself on any given date. The denial occurs only when the component service is reported on the same date as the more comprehensive service.

For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) is considered comprehensive to codes 36000 (introduction of needle or intracatheter, vein) and 36410 (venipuncture, age 3 years or older, necessitating physician’s skill [separate procedure], for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). These code combinations should not be reported together on the same date when performed as part of the same procedure by the same physician or physicians of the same practice group. If this occurs, the payor will reimburse the initial service and deny the subsequent service. As a result, the first code received by the payor, on the same or separate claims, is reimbursed, even if that code represents the lesser of the two services.

Mutually Exclusive edits occur with less frequency than Column One/Column Two edits. Mutually Exclusive edits prevent reporting of two services or procedures that are highly unlikely to be performed together on the same patient, at the same session or encounter, by the same physician or physicians of the same specialty in a provider group. For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) would not be reported on the same day as 36555 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, younger than 5 years of age).

CMS publishes the National Correct Coding Initiative Coding Policy Manual for Medicare Services (www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd) and encourages local Medicare contractors and fiscal intermediaries to use it as a reference for claims-processing edits. The manual is updated annually, and the NCCI edits are updated quarterly. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- National correct coding initiative edits. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Medicare claims processing manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2008;477-481.

- Modifier 59 article. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/Downloads/modifier59.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- French K. Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians. 2008;283-287.

A hospitalist who scrutinizes claims might notice a payment denial related to “unbundling” issues. Line-item rejections might state the service is “mutually exclusive,” “incidental to another procedure,” or “payment was received as part of another service/procedure.” Unbundling refers to the practice of reporting each component of a service or procedure instead of reporting the single, comprehensive code. Two types of practices lead to unbundling: unintentional reporting resulting from a basic misunderstanding of correct coding, and intentional reporting to improperly maximize payment of otherwise bundled Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.1

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) for implementation and application to physician claims (e.g., Medicare Part B) with dates of service on or after Jan. 1, 1996. The rationale for these edits is a culmination of:

- Coding standards identified in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) CPT manual;

- National and local coverage determinations developed by CMS and local Medicare contractors;

- Coding standards set forth by national medical organizations and specialty societies;

- Appropriate standards of medical and surgical care; and

- Current coding practices identified through claim analysis, pre- and post-payment documentation reviews, and other forms of payor-initiated audit.

The initial NCCI goal was to promote correct coding methodologies and to control improper coding, which led to inappropriate payment in Part B claims.2 It later expanded to include corresponding NCCI edits in the outpatient code editor (OCE) for both outpatient hospital providers and therapy providers. Therapy providers encompass skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities (CORFs), outpatient physical therapy (OPTs) and speech-language pathology providers, and home health agencies (HHAs).

Fact-Check

The NCCI recognizes two edit types: Column One/Column Two Correct Coding edits and Mutually Exclusive edits. Each of these edit categories lists code pairs that should not be reported together on the same date by either a single physician or physicians of the same specialty within a provider group.

When applying Column One/Column Two editing logic to physician claims, the Column One code represents the more comprehensive code of the pair being reported. The Column Two code (the component service that is bundled into the comprehensive service) will be denied. This is not to say a code that appears in Column Two of the NCCI cannot be paid when reported by itself on any given date. The denial occurs only when the component service is reported on the same date as the more comprehensive service.

For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) is considered comprehensive to codes 36000 (introduction of needle or intracatheter, vein) and 36410 (venipuncture, age 3 years or older, necessitating physician’s skill [separate procedure], for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). These code combinations should not be reported together on the same date when performed as part of the same procedure by the same physician or physicians of the same practice group. If this occurs, the payor will reimburse the initial service and deny the subsequent service. As a result, the first code received by the payor, on the same or separate claims, is reimbursed, even if that code represents the lesser of the two services.

Mutually Exclusive edits occur with less frequency than Column One/Column Two edits. Mutually Exclusive edits prevent reporting of two services or procedures that are highly unlikely to be performed together on the same patient, at the same session or encounter, by the same physician or physicians of the same specialty in a provider group. For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) would not be reported on the same day as 36555 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, younger than 5 years of age).

CMS publishes the National Correct Coding Initiative Coding Policy Manual for Medicare Services (www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd) and encourages local Medicare contractors and fiscal intermediaries to use it as a reference for claims-processing edits. The manual is updated annually, and the NCCI edits are updated quarterly. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- National correct coding initiative edits. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Medicare claims processing manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2008;477-481.

- Modifier 59 article. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/Downloads/modifier59.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- French K. Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians. 2008;283-287.

A hospitalist who scrutinizes claims might notice a payment denial related to “unbundling” issues. Line-item rejections might state the service is “mutually exclusive,” “incidental to another procedure,” or “payment was received as part of another service/procedure.” Unbundling refers to the practice of reporting each component of a service or procedure instead of reporting the single, comprehensive code. Two types of practices lead to unbundling: unintentional reporting resulting from a basic misunderstanding of correct coding, and intentional reporting to improperly maximize payment of otherwise bundled Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.1

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) for implementation and application to physician claims (e.g., Medicare Part B) with dates of service on or after Jan. 1, 1996. The rationale for these edits is a culmination of:

- Coding standards identified in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) CPT manual;

- National and local coverage determinations developed by CMS and local Medicare contractors;

- Coding standards set forth by national medical organizations and specialty societies;

- Appropriate standards of medical and surgical care; and

- Current coding practices identified through claim analysis, pre- and post-payment documentation reviews, and other forms of payor-initiated audit.

The initial NCCI goal was to promote correct coding methodologies and to control improper coding, which led to inappropriate payment in Part B claims.2 It later expanded to include corresponding NCCI edits in the outpatient code editor (OCE) for both outpatient hospital providers and therapy providers. Therapy providers encompass skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities (CORFs), outpatient physical therapy (OPTs) and speech-language pathology providers, and home health agencies (HHAs).

Fact-Check

The NCCI recognizes two edit types: Column One/Column Two Correct Coding edits and Mutually Exclusive edits. Each of these edit categories lists code pairs that should not be reported together on the same date by either a single physician or physicians of the same specialty within a provider group.

When applying Column One/Column Two editing logic to physician claims, the Column One code represents the more comprehensive code of the pair being reported. The Column Two code (the component service that is bundled into the comprehensive service) will be denied. This is not to say a code that appears in Column Two of the NCCI cannot be paid when reported by itself on any given date. The denial occurs only when the component service is reported on the same date as the more comprehensive service.

For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) is considered comprehensive to codes 36000 (introduction of needle or intracatheter, vein) and 36410 (venipuncture, age 3 years or older, necessitating physician’s skill [separate procedure], for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). These code combinations should not be reported together on the same date when performed as part of the same procedure by the same physician or physicians of the same practice group. If this occurs, the payor will reimburse the initial service and deny the subsequent service. As a result, the first code received by the payor, on the same or separate claims, is reimbursed, even if that code represents the lesser of the two services.

Mutually Exclusive edits occur with less frequency than Column One/Column Two edits. Mutually Exclusive edits prevent reporting of two services or procedures that are highly unlikely to be performed together on the same patient, at the same session or encounter, by the same physician or physicians of the same specialty in a provider group. For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) would not be reported on the same day as 36555 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, younger than 5 years of age).

CMS publishes the National Correct Coding Initiative Coding Policy Manual for Medicare Services (www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd) and encourages local Medicare contractors and fiscal intermediaries to use it as a reference for claims-processing edits. The manual is updated annually, and the NCCI edits are updated quarterly. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- National correct coding initiative edits. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Medicare claims processing manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2008;477-481.

- Modifier 59 article. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/Downloads/modifier59.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- French K. Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians. 2008;283-287.

Palliative-Care Payment

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.

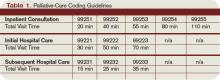

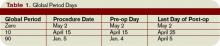

As a reminder, document the total time, the amount of time spent counseling, and the details of discussion and coordination. The physician may count the time spent counseling the patient’s family regarding the treatment and care, as long as the focus is not emotional support for the family, the meeting takes place in the patient’s unit or floor, and the patient is present, unless there is medically supported reason for which the patient is unable to participate (e.g., cognitive impairment). The palliative-care specialist can then select the visit level based on time.5 (See Table 1, above.) TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26, Section 10.8. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

5. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2008.

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.

As a reminder, document the total time, the amount of time spent counseling, and the details of discussion and coordination. The physician may count the time spent counseling the patient’s family regarding the treatment and care, as long as the focus is not emotional support for the family, the meeting takes place in the patient’s unit or floor, and the patient is present, unless there is medically supported reason for which the patient is unable to participate (e.g., cognitive impairment). The palliative-care specialist can then select the visit level based on time.5 (See Table 1, above.) TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26, Section 10.8. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

5. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2008.

Many hospitalists provide palliative-care services to patients at the request of physicians within their own groups or from other specialists. Varying factors affect how hospitalists report these services—namely, the nature of the request and the type of service provided. Palliative-care programs can be quite costly as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives is pertinent.

Nature of the Request

Members of a palliative-care team often are called on to provide management options to assist in reducing pain and suffering associated with both terminal and nonterminal disease, thereby improving a patient’s quality of life. When a palliative-care specialist is asked to provide an opinion or advice, the initial service could qualify as a consultation. However, all requirements must be met in order to report the service as an inpatient consultation (codes 99251-99255).

There must be a written request from a qualified healthcare provider involved in the patient’s care (e.g., a physician, resident, or nurse practitioner). In the inpatient setting, this request can be documented as a physician order or in the assessment of the requesting provider’s progress note. Standing orders for consultation are not permitted. Ideally, the requesting provider should identify the reason for a consult to support the medical necessity of the service.

Additionally, the palliative-care physician renders and documents the service, then reports findings to the requesting physician. The consultant’s required written report does not have to be sent separately to the requesting physician. Because the requesting physician and the consultant share a common medical record in an inpatient setting, the consultant’s inpatient progress note suffices the “written report” requirement.

One concern about billing consultations involves the nature of the request. If the requesting physician documents the need for an opinion or advice from the palliative-care specialist, the service can be reported as a consultation. If, however, the request states consult for “medical management” or “palliative management,” it’s less likely that payors will consider the service a consultation. In the latter situation, it appears as if the requesting physician is not seeking an opinion or advice from the consultant to incorporate into his own plan of care for the patient and would rather the consultant take over that portion of patient care.

Recently revised billing policies prevent the consultant from billing consults under these circumstances. Without a sufficient request for consultation, the palliative-care specialist can only report “subsequent” hospital care services.1 Language that better supports the consultative nature of the request is:

- Consult for an opinion or advice on palliative measures;

- Consult for evaluation of palliative options; and

- Consult palliative care for treatment options.

Proper Documentation

The requesting physician can be in the same or different provider group as the consultant. The consultant must possess expertise in an area beyond that of the requesting provider. Because the specialty designation for most hospitalists is internal medicine, palliative-care claims could be scrutinized more closely. This does not necessarily occur when the requesting provider has a different two-digit specialty designation (e.g., internal medicine and gastroenterology).2 Scrutiny is more likely to occur when the requesting provider has the same internal-medicine designation as the palliative-care consultant, even if they are in different provider groups.

Payor concern escalates when physicians of the same designated specialty submit claims for the same patient on the same date. Having different primary diagnosis codes attached to each visit level does not necessarily help. The payor is likely to deny the second claim received, pending a review of documentation. If this happens, the provider who received the denial should submit a copy of both progress notes for the date in question. Hopefully, the distinction between the services is demonstrated in the documentation.

Service Type

Palliative services might involve obtaining and documenting the standard key components for visit-level selection: history, exam, and medical decision-making.3 However, the palliative-care specialist might spend more time providing counseling or coordination of care for a patient and family. When this occurs, the palliative-care specialist should not forget about the guidelines for reporting time-based services.4 Inpatient services may be reported on the basis of time, as long as a face-to-face service between the provider and the patient occurs. Consider the total time spent face to face with the patient, and the time spent obtaining, discussing, and coordinating patient care, while you are in the patient’s unit or floor.

As a reminder, document the total time, the amount of time spent counseling, and the details of discussion and coordination. The physician may count the time spent counseling the patient’s family regarding the treatment and care, as long as the focus is not emotional support for the family, the meeting takes place in the patient’s unit or floor, and the patient is present, unless there is medically supported reason for which the patient is unable to participate (e.g., cognitive impairment). The palliative-care specialist can then select the visit level based on time.5 (See Table 1, above.) TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26, Section 10.8. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 30, 2009.

5. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2008.

Misunderstood Modifiers

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Eagle-Eye Your Payors

Protection of the Medicare program has reached new heights in recent years. One of the most important ways hospitalist groups can protect their Medicare funding is the discovery and recovery of improper contractor payments of Medicare claims.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reviews various types of contractors—Medicare administrative contractors (MACs), carriers, durable medical equipment regional carriers (DMERCs), fiscal intermediaries (FIs), and quality improvement organizations (QIOs)—through its protection efforts as part of the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program and Hospital Payment Monitoring Program (HPMP). The CERT program’s contractors review physician (i.e., professional) claims processed by MACs and carriers.

The primary goal of a contractor is to “pay it right”—that is, pay the correct amount to the right provider for covered and correctly coded services.1 During the 12-month reporting period ending Sept. 30, 2007, the CERT program sampled 129,875 claims from carriers, DMERCs, FIs, and MACs.

The CERT contractor randomly and electronically selects about 172 claims each month from each type of claims-processing contractor. Since some of these contractors were transitioning to MACs, the target Part B (i.e., professional) sample size for the May 2008 report was approximately 2,000 reviewable claims per MAC cluster. However, this might have varied if a MAC was not processing claims during the entire sampling period.

Document Requests

Physicians need to be mindful of CERT requests for documentation. When possible, every attempt is made to benefit the physician. Initial CERT requests are attempted by way of a letter. If the physician does not respond within 30 days, the CERT contractor attempts one to three more contacts with correspondence and phone calls. If documentation is received after 75 days, it is considered “late.” It then will be reviewed, unless the reporting period has expired.

However, this should not be considered a prudent approach, and timely responses are ideal. If the physician offers no response, and documentation is not received, it is counted as a “no documentation” error.

Physicians often worry about accusations of fraud. The purpose of the CERT program is not to assume or accuse physicians of fraud, although it may serve as a deterrent. It does not, and cannot, label a claim fraudulent.

One scenario of potential fraud the CERT program is able to identify occurs when a CERT documentation contractor is unable to locate a provider or supplier when requesting medical record documentation.2

Outcomes

Individual contractors are notified of improper payments. These include overpayments and underpayments. Unfortunately, contractors do not have to resolve CERT issues involving underpayments, although they are encouraged to do so by CMS.

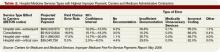

The CERT program identified overpayments totaling $875,005 during the 12-month reporting period, but collected only $650,418 in overpayments after consideration of appeals that overturned a CERT decision or the provider discontinued business operations. (See Table 1, p. 18, for error rates and Table 2, p. 18, for highest rates of improper payment)

To improve billing compliance and prevent repetitive errors, contractors must implement provider education regarding erroneously paid claims. A contractor may determine the best education method to distribute information about Medicare rules and effectively answer coverage and coding questions.

Some contractors have designed Web-based training modules, Web pages with frequently-asked-questions sections, or local coverage analyses to address contractor-specific errors. Detailed CERT contractor information can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/ mcd/indexes.asp?from2=indexes.asp&

Due to its successful outcomes, future CMS goals include the continuation of the CERT program. MACs will look more closely at service types based on identified error rates.

Apart from CERT requests, prepayment contractor reviews already exist for most of the services included in Table 2 (p. 18). Timely response is crucial to justify and receive appropriate reimbursement. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Improper Medicare fee-for-service payments report: May 2008. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/er_report/preview_er_report.asp?from=public&which=long&reportID=9. Accessed Dec. 20, 2008.

2. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008.

Protection of the Medicare program has reached new heights in recent years. One of the most important ways hospitalist groups can protect their Medicare funding is the discovery and recovery of improper contractor payments of Medicare claims.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reviews various types of contractors—Medicare administrative contractors (MACs), carriers, durable medical equipment regional carriers (DMERCs), fiscal intermediaries (FIs), and quality improvement organizations (QIOs)—through its protection efforts as part of the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program and Hospital Payment Monitoring Program (HPMP). The CERT program’s contractors review physician (i.e., professional) claims processed by MACs and carriers.

The primary goal of a contractor is to “pay it right”—that is, pay the correct amount to the right provider for covered and correctly coded services.1 During the 12-month reporting period ending Sept. 30, 2007, the CERT program sampled 129,875 claims from carriers, DMERCs, FIs, and MACs.

The CERT contractor randomly and electronically selects about 172 claims each month from each type of claims-processing contractor. Since some of these contractors were transitioning to MACs, the target Part B (i.e., professional) sample size for the May 2008 report was approximately 2,000 reviewable claims per MAC cluster. However, this might have varied if a MAC was not processing claims during the entire sampling period.

Document Requests

Physicians need to be mindful of CERT requests for documentation. When possible, every attempt is made to benefit the physician. Initial CERT requests are attempted by way of a letter. If the physician does not respond within 30 days, the CERT contractor attempts one to three more contacts with correspondence and phone calls. If documentation is received after 75 days, it is considered “late.” It then will be reviewed, unless the reporting period has expired.

However, this should not be considered a prudent approach, and timely responses are ideal. If the physician offers no response, and documentation is not received, it is counted as a “no documentation” error.

Physicians often worry about accusations of fraud. The purpose of the CERT program is not to assume or accuse physicians of fraud, although it may serve as a deterrent. It does not, and cannot, label a claim fraudulent.

One scenario of potential fraud the CERT program is able to identify occurs when a CERT documentation contractor is unable to locate a provider or supplier when requesting medical record documentation.2

Outcomes

Individual contractors are notified of improper payments. These include overpayments and underpayments. Unfortunately, contractors do not have to resolve CERT issues involving underpayments, although they are encouraged to do so by CMS.

The CERT program identified overpayments totaling $875,005 during the 12-month reporting period, but collected only $650,418 in overpayments after consideration of appeals that overturned a CERT decision or the provider discontinued business operations. (See Table 1, p. 18, for error rates and Table 2, p. 18, for highest rates of improper payment)

To improve billing compliance and prevent repetitive errors, contractors must implement provider education regarding erroneously paid claims. A contractor may determine the best education method to distribute information about Medicare rules and effectively answer coverage and coding questions.

Some contractors have designed Web-based training modules, Web pages with frequently-asked-questions sections, or local coverage analyses to address contractor-specific errors. Detailed CERT contractor information can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/ mcd/indexes.asp?from2=indexes.asp&

Due to its successful outcomes, future CMS goals include the continuation of the CERT program. MACs will look more closely at service types based on identified error rates.

Apart from CERT requests, prepayment contractor reviews already exist for most of the services included in Table 2 (p. 18). Timely response is crucial to justify and receive appropriate reimbursement. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Improper Medicare fee-for-service payments report: May 2008. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/er_report/preview_er_report.asp?from=public&which=long&reportID=9. Accessed Dec. 20, 2008.

2. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008.

Protection of the Medicare program has reached new heights in recent years. One of the most important ways hospitalist groups can protect their Medicare funding is the discovery and recovery of improper contractor payments of Medicare claims.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reviews various types of contractors—Medicare administrative contractors (MACs), carriers, durable medical equipment regional carriers (DMERCs), fiscal intermediaries (FIs), and quality improvement organizations (QIOs)—through its protection efforts as part of the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program and Hospital Payment Monitoring Program (HPMP). The CERT program’s contractors review physician (i.e., professional) claims processed by MACs and carriers.

The primary goal of a contractor is to “pay it right”—that is, pay the correct amount to the right provider for covered and correctly coded services.1 During the 12-month reporting period ending Sept. 30, 2007, the CERT program sampled 129,875 claims from carriers, DMERCs, FIs, and MACs.

The CERT contractor randomly and electronically selects about 172 claims each month from each type of claims-processing contractor. Since some of these contractors were transitioning to MACs, the target Part B (i.e., professional) sample size for the May 2008 report was approximately 2,000 reviewable claims per MAC cluster. However, this might have varied if a MAC was not processing claims during the entire sampling period.

Document Requests

Physicians need to be mindful of CERT requests for documentation. When possible, every attempt is made to benefit the physician. Initial CERT requests are attempted by way of a letter. If the physician does not respond within 30 days, the CERT contractor attempts one to three more contacts with correspondence and phone calls. If documentation is received after 75 days, it is considered “late.” It then will be reviewed, unless the reporting period has expired.

However, this should not be considered a prudent approach, and timely responses are ideal. If the physician offers no response, and documentation is not received, it is counted as a “no documentation” error.

Physicians often worry about accusations of fraud. The purpose of the CERT program is not to assume or accuse physicians of fraud, although it may serve as a deterrent. It does not, and cannot, label a claim fraudulent.

One scenario of potential fraud the CERT program is able to identify occurs when a CERT documentation contractor is unable to locate a provider or supplier when requesting medical record documentation.2

Outcomes

Individual contractors are notified of improper payments. These include overpayments and underpayments. Unfortunately, contractors do not have to resolve CERT issues involving underpayments, although they are encouraged to do so by CMS.

The CERT program identified overpayments totaling $875,005 during the 12-month reporting period, but collected only $650,418 in overpayments after consideration of appeals that overturned a CERT decision or the provider discontinued business operations. (See Table 1, p. 18, for error rates and Table 2, p. 18, for highest rates of improper payment)

To improve billing compliance and prevent repetitive errors, contractors must implement provider education regarding erroneously paid claims. A contractor may determine the best education method to distribute information about Medicare rules and effectively answer coverage and coding questions.

Some contractors have designed Web-based training modules, Web pages with frequently-asked-questions sections, or local coverage analyses to address contractor-specific errors. Detailed CERT contractor information can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/ mcd/indexes.asp?from2=indexes.asp&

Due to its successful outcomes, future CMS goals include the continuation of the CERT program. MACs will look more closely at service types based on identified error rates.

Apart from CERT requests, prepayment contractor reviews already exist for most of the services included in Table 2 (p. 18). Timely response is crucial to justify and receive appropriate reimbursement. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Improper Medicare fee-for-service payments report: May 2008. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/er_report/preview_er_report.asp?from=public&which=long&reportID=9. Accessed Dec. 20, 2008.

2. Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008.

Face-to-Face Improvement

The American Medical Association recently released Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) 2009. New, deleted, and revised codes went into effect Jan. 1. The biggest change to hospitalist billing involves prolonged care codes (99354-99357). CPT 2009 descriptor revisions make it possible for physicians to contribute non-face-to-face time toward prolonged care services.

Inpatient Prolonged Care

Previous versions of CPT defined code 99356 as the first hour of prolonged physician [inpatient] services requiring direct (face-to-face) patient contact beyond the usual services (reportable after the initial 30 minutes); and 99357 for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged [inpatient] care beyond the first hour (reportable after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment). CPT 2009 has changed prolonged care guidelines to be more consistent with other time-based services: all unit/floor time spent by the physician is considered when reporting 99356 and 99357.1

As with most other evaluation and management services, a face-to-face encounter still must occur. In addition to the time associated with the face-to-face encounter, count the time associated with all other physician activities occurring on the unit/floor (e.g., reviewing images, obtaining information involving overnight events, discussing management options with the family) directed toward an individual patient. The cumulative time spent by the billing provider on a single calendar day is considered for billing. Time spent by someone other than the billing provider cannot be credited toward prolonged care.

As example, a physician cares for a 65-year-old male with uncontrolled diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and congestive heart failure. Early in the day, the physician rounds, spending a total of 20 minutes reviewing the overnight course of events on the unit, re-confirming the patient history, and performing an exam with the patient. Anticipating the patient’s needs, the physician discusses post-discharge options and care with the patient and his family for 45 minutes. After the discussion, the physician spends an additional 30 minutes relaying information to the team and coordinating care. Merely reporting the highest-level subsequent hospital care service (99233), does not capture the physician’s cumulative effort. It only would account for 40 of the 95 minutes spent throughout the day. In order to capture the remaining 55 minutes, the physician reports 99356 on the same claim form as 99233.

Do not report prolonged care codes on a separate claim form. Prolonged care codes do not represent an independent service. These codes are reported along with a primary service. They must appear as a separate line item on the claim form, which includes a code representing the primary service. For prolonged care in the inpatient setting, the primary service must be initial hospital care (99221-99223), subsequent hospital care (99231-99233), inpatient consultations (99251-99255), or nursing facility services (99304-99318). Additional examples of billable prolonged care services are in Section 30.6.15.1I of the Medicare manual, available at www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/ downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

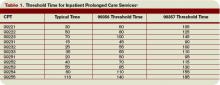

Threshold Time

Prolonged care guidelines refer to “threshold” time. Threshold time requires the physician to exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes before reporting prolonged care. Table 1 identifies the typical times associated with inpatient services qualifying for prolonged care. The physician must exceed the typical time by a minimum of 30 minutes. (For example, 99232 + 99356 = 25 minutes + 30 minutes = 55 total minutes). Additionally, the physician must document the total time spent during the face-to-face portion of the encounter, and the additional unit or floor time in one cumulative note or in separate notes representing the physician services provided to the patient throughout the day.

Prolonged Outpatient Services

Prolonged care (99354-99355) provided to outpatients remains unchanged. Physicians only report personally provided face-to-face time with the patient. Time spent by other staff members does not count toward prolonged care.

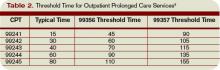

As with prolonged inpatient care, report 99354 and 99355 in addition to a primary service code. The companion outpatient codes are outpatient/office visits (99201-99205 or 99212–99215), outpatient consultation (99241–99245), domiciliary/custodial care (99324–99328 or 99334–99337), and home services (99341-99350). Hospitalists more often use outpatient prolonged care with office consultation codes for services provided in the emergency department, as appropriate.

Do not report 99354 or 99355 with observation care (99217-99220) or emergency department visits (99281-99288), since these service categories typically require prolonged periods of physician monitoring, thereby prohibiting use of prolonged care codes. As with inpatient-prolonged care, the concept of threshold time exists. Refer to Table 2 (pg. 25) for the typical threshold times associated with office consultation codes.

Medicare Consideration

Although CPT has offered revisions to this code, Medicare guidelines remain unchanged. The Medicare Claims Processing Manual still states: “In the case of prolonged hospital services, time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff and not with direct face-to-face contact with the patient, or waiting for test results, for changes in the patient’s condition, for end of a therapy, or for use of facilities, cannot be billed as prolonged services.”4 It is yet to be determined if the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will issue a transmittal to revise the current description in the processing manual. Physicians and staff may access past and present transmittal information at www.cms.hhs.gov/ Transmittals/.