User login

Hospitalist Pay Shifts from Volume to Value with Global Payment System

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

Society of Hospital Medicine's CODE-H Helps Hospitalists Avoid Coding Issues

Use SHM’s CODE-H Interactive to Avoid Coding Issues

Coding is a part of every hospitalist’s life, but tips from the experts can make that life easier, more efficient, and more compliant. That’s why SHM’s CODE-H program teaches hospitalists and hospitalist group managers and administrators how to stay up to date with the latest in the best

practices of coding and documentation.

On March 20, coding expert Barbara Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, will present an online session on some of the most important coding topics for hospitalists, including:

- Critical care;

- Prolonged services;

- Documentation when working with NPs and PAs;

- Teaching physician rules; and

- Tips to avoid billing issues and potential denials.

This session is the third in a series of seven that cover the full range of coding topics, from developing a compliance plan and internal auditing process to ICD-10, PQRS, and Medicare’s Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier.

CME credits are offered through post-tests following each webinar, and each participant is eligible for up to seven credits throughout the series. Up to 10 individuals in a group can sign up through a single registration.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Use SHM’s CODE-H Interactive to Avoid Coding Issues

Coding is a part of every hospitalist’s life, but tips from the experts can make that life easier, more efficient, and more compliant. That’s why SHM’s CODE-H program teaches hospitalists and hospitalist group managers and administrators how to stay up to date with the latest in the best

practices of coding and documentation.

On March 20, coding expert Barbara Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, will present an online session on some of the most important coding topics for hospitalists, including:

- Critical care;

- Prolonged services;

- Documentation when working with NPs and PAs;

- Teaching physician rules; and

- Tips to avoid billing issues and potential denials.

This session is the third in a series of seven that cover the full range of coding topics, from developing a compliance plan and internal auditing process to ICD-10, PQRS, and Medicare’s Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier.

CME credits are offered through post-tests following each webinar, and each participant is eligible for up to seven credits throughout the series. Up to 10 individuals in a group can sign up through a single registration.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Use SHM’s CODE-H Interactive to Avoid Coding Issues

Coding is a part of every hospitalist’s life, but tips from the experts can make that life easier, more efficient, and more compliant. That’s why SHM’s CODE-H program teaches hospitalists and hospitalist group managers and administrators how to stay up to date with the latest in the best

practices of coding and documentation.

On March 20, coding expert Barbara Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, will present an online session on some of the most important coding topics for hospitalists, including:

- Critical care;

- Prolonged services;

- Documentation when working with NPs and PAs;

- Teaching physician rules; and

- Tips to avoid billing issues and potential denials.

This session is the third in a series of seven that cover the full range of coding topics, from developing a compliance plan and internal auditing process to ICD-10, PQRS, and Medicare’s Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier.

CME credits are offered through post-tests following each webinar, and each participant is eligible for up to seven credits throughout the series. Up to 10 individuals in a group can sign up through a single registration.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Get Ready for Transition to ICD-10 Medical Coding

By now, I’m sure you’re knowledgeable about things like healthcare exchanges and other parts of the Accountable Care Act, the increasing number of metrics within hospital value-based purchasing, the physician value-based payment modifier, the physician quality reporting system (PQRS), how to use your hospital’s new EHR efficiently, the new “two-midnight rule” to determine inpatient vs. observation status, and so on.

You’re to be commended if you’re staying on top of all these things and have effective plans in place to ensure good performance on each. And if you haven’t already, you should add at least one more important issue to this list—the transition to ICD-10 coding on Oct. 1, 2014.

An Overview

ICD stands for International Classification of Diseases, and the U.S. has been using the 9th revision (ICD-9) since 1978. ICD-9 is now significantly out of step with current medical knowledge and has run out of codes in some disease sections (“chapters”). This might mean, for example, that new codes for heart diseases would be assigned to the chapter for eye disease, because the former is full.

ICD-10 provides a way to fix these problems and, through more specific coding of diseases, should be able to yield more useful “big data” to measure things like safety and efficacy of care and more accurately identify diagnosis trends and epidemics. And, in theory, it could reduce the number of rejected billing claims, though I’m waiting to see if that happens. I worry that even after fixing all the initial bugs related to the ICD-10 transition, we will see more claim rejections than we experience today.

ICD codes can be thought of as diagnosis codes. CPT codes (Current Procedural Terminology) are an entirely separate set of codes that we use to report the work we do for the purposes of billing. We need to be familiar with both, but it is the ICD codes that are changing.

ICD-10 Basics and Trivia

The World Health Organization issued the ICD-10 in 1994, and it is already in use in many countries. Like some other countries, the U.S. made modifications to the WHO’s original code set, so we refer to ICD-10-CM (Clinical Modification), which contains diagnosis codes. The National Center for Health Statistics, a department of the CDC, is responsible for these modifications.

The WHO version of ICD-10 doesn’t have any procedure codes, so CMS developed ICD-10-PCS (Procedure Coding System) to report procedures, such as surgeries, done in U.S. hospitals. Most hospitalists won’t use these procedure codes often.

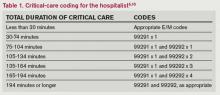

Table 1 (left) compares ICD-10-CM to ICD-9-CM. Most of the additional codes in the new version simply add information regarding whether the diagnosis is on the left or right of the body, acute or chronic, or an initial or subsequent visit for the condition. But the standard structure for each code had to be modified significantly to capture this additional information. Some highlights of the seven-character code structure are:

- Characters 1–3: category; first digit always a letter, second digit always a number, all other digits can be either; not case sensitive;

- Characters 4–6: etiology, anatomic site, severity, or other clinical detail; for example, 1=right, 2=left, 3-bilateral, and 0 or 9=unspecified; and

- Character 7: extension (i.e., A=initial encounter, D=subsequent encounter, S=sequelae).

- A placeholder “x” is used as needed to fill in empty characters to ensure that the seventh character stays in the seventh position. For example, T79.1xxA equates to “fat embolism, initial encounter.” (Note that the “dummy” characters could create problems for some IT systems.)

An example of more information contained in additional characters:

- S52=fracture of forearm.

- S52.5=fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.52=torus fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.521=torus fracture of lower end of right radius.

- S52.521A=torus fracture of lower end of right radius, initial encounter for closed fracture.

Compared to its predecessor, ICD-10 expands use of combination codes. These are single codes that can be used to classify either two diagnoses, a diagnosis with an associated secondary process, or a diagnosis with an associated complication. For example, rather than reporting acute cor pulmonale and septic pulmonary embolism separately, ICD-10 allows use of the code I26.01: septic pulmonary embolism with acute cor pulmonale.

Resources

In addition to resources on the SHM website, both the American Medical Association (www.ama-assn.org, search “ICD-10”) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.gov/icd10) have very informative microsites offering detailed ICD-10 information. Much of the information in this column, including the examples above, comes from those sites.

What to Expect

Your hospital and your employer are probably already working in earnest to prepare for the change. In some cases, hospitalists are actively involved in these preparations, but in most cases they will simply wait for an organization to notify them that they should begin training to understand the new coding system. Experts say that most physicians will need two to four hours of training on ICD-10, but because we use a universe of diagnosis codes that is much larger than many specialties, I wonder if hospitalists may need additional training.

Like nearly all the programs I listed at the beginning, the transition to ICD-10 has me concerned. Managing it poorly could mean significant loss in hospital and physician professional fee revenue, as well as lots of tedious and time-consuming work. So, doing it right is important. But, it is also important to do well on all the programs I listed at the beginning of this column, and many others, and there is a limit to just how much we can do effectively as individuals.

Collectively, these programs risk taking too much time and too many brain cells away from keeping up with clinical medicine. So, I wonder if, for many of us, ICD-10 will serve as a tipping point that results in physicians hiring professional coders to choose our diagnosis codes and CPT codes rather than doing it ourselves.

As with EHRs, ICD-10 is said to have many benefits. But the introduction of EHRs in many hospitals had the unintended effect of significantly reducing the number of doctors who were willing to serve as admitting and attending physicians; instead, many chose to refer to hospitalists. In a similar way, ICD-10 might lead many organizations to relieve physicians of the responsibility of looking up and entering codes for each patient, leaving them with more time and energy to be clinicians. We’ll have to wait and see.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

By now, I’m sure you’re knowledgeable about things like healthcare exchanges and other parts of the Accountable Care Act, the increasing number of metrics within hospital value-based purchasing, the physician value-based payment modifier, the physician quality reporting system (PQRS), how to use your hospital’s new EHR efficiently, the new “two-midnight rule” to determine inpatient vs. observation status, and so on.

You’re to be commended if you’re staying on top of all these things and have effective plans in place to ensure good performance on each. And if you haven’t already, you should add at least one more important issue to this list—the transition to ICD-10 coding on Oct. 1, 2014.

An Overview

ICD stands for International Classification of Diseases, and the U.S. has been using the 9th revision (ICD-9) since 1978. ICD-9 is now significantly out of step with current medical knowledge and has run out of codes in some disease sections (“chapters”). This might mean, for example, that new codes for heart diseases would be assigned to the chapter for eye disease, because the former is full.

ICD-10 provides a way to fix these problems and, through more specific coding of diseases, should be able to yield more useful “big data” to measure things like safety and efficacy of care and more accurately identify diagnosis trends and epidemics. And, in theory, it could reduce the number of rejected billing claims, though I’m waiting to see if that happens. I worry that even after fixing all the initial bugs related to the ICD-10 transition, we will see more claim rejections than we experience today.

ICD codes can be thought of as diagnosis codes. CPT codes (Current Procedural Terminology) are an entirely separate set of codes that we use to report the work we do for the purposes of billing. We need to be familiar with both, but it is the ICD codes that are changing.

ICD-10 Basics and Trivia

The World Health Organization issued the ICD-10 in 1994, and it is already in use in many countries. Like some other countries, the U.S. made modifications to the WHO’s original code set, so we refer to ICD-10-CM (Clinical Modification), which contains diagnosis codes. The National Center for Health Statistics, a department of the CDC, is responsible for these modifications.

The WHO version of ICD-10 doesn’t have any procedure codes, so CMS developed ICD-10-PCS (Procedure Coding System) to report procedures, such as surgeries, done in U.S. hospitals. Most hospitalists won’t use these procedure codes often.

Table 1 (left) compares ICD-10-CM to ICD-9-CM. Most of the additional codes in the new version simply add information regarding whether the diagnosis is on the left or right of the body, acute or chronic, or an initial or subsequent visit for the condition. But the standard structure for each code had to be modified significantly to capture this additional information. Some highlights of the seven-character code structure are:

- Characters 1–3: category; first digit always a letter, second digit always a number, all other digits can be either; not case sensitive;

- Characters 4–6: etiology, anatomic site, severity, or other clinical detail; for example, 1=right, 2=left, 3-bilateral, and 0 or 9=unspecified; and

- Character 7: extension (i.e., A=initial encounter, D=subsequent encounter, S=sequelae).

- A placeholder “x” is used as needed to fill in empty characters to ensure that the seventh character stays in the seventh position. For example, T79.1xxA equates to “fat embolism, initial encounter.” (Note that the “dummy” characters could create problems for some IT systems.)

An example of more information contained in additional characters:

- S52=fracture of forearm.

- S52.5=fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.52=torus fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.521=torus fracture of lower end of right radius.

- S52.521A=torus fracture of lower end of right radius, initial encounter for closed fracture.

Compared to its predecessor, ICD-10 expands use of combination codes. These are single codes that can be used to classify either two diagnoses, a diagnosis with an associated secondary process, or a diagnosis with an associated complication. For example, rather than reporting acute cor pulmonale and septic pulmonary embolism separately, ICD-10 allows use of the code I26.01: septic pulmonary embolism with acute cor pulmonale.

Resources

In addition to resources on the SHM website, both the American Medical Association (www.ama-assn.org, search “ICD-10”) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.gov/icd10) have very informative microsites offering detailed ICD-10 information. Much of the information in this column, including the examples above, comes from those sites.

What to Expect

Your hospital and your employer are probably already working in earnest to prepare for the change. In some cases, hospitalists are actively involved in these preparations, but in most cases they will simply wait for an organization to notify them that they should begin training to understand the new coding system. Experts say that most physicians will need two to four hours of training on ICD-10, but because we use a universe of diagnosis codes that is much larger than many specialties, I wonder if hospitalists may need additional training.

Like nearly all the programs I listed at the beginning, the transition to ICD-10 has me concerned. Managing it poorly could mean significant loss in hospital and physician professional fee revenue, as well as lots of tedious and time-consuming work. So, doing it right is important. But, it is also important to do well on all the programs I listed at the beginning of this column, and many others, and there is a limit to just how much we can do effectively as individuals.

Collectively, these programs risk taking too much time and too many brain cells away from keeping up with clinical medicine. So, I wonder if, for many of us, ICD-10 will serve as a tipping point that results in physicians hiring professional coders to choose our diagnosis codes and CPT codes rather than doing it ourselves.

As with EHRs, ICD-10 is said to have many benefits. But the introduction of EHRs in many hospitals had the unintended effect of significantly reducing the number of doctors who were willing to serve as admitting and attending physicians; instead, many chose to refer to hospitalists. In a similar way, ICD-10 might lead many organizations to relieve physicians of the responsibility of looking up and entering codes for each patient, leaving them with more time and energy to be clinicians. We’ll have to wait and see.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

By now, I’m sure you’re knowledgeable about things like healthcare exchanges and other parts of the Accountable Care Act, the increasing number of metrics within hospital value-based purchasing, the physician value-based payment modifier, the physician quality reporting system (PQRS), how to use your hospital’s new EHR efficiently, the new “two-midnight rule” to determine inpatient vs. observation status, and so on.

You’re to be commended if you’re staying on top of all these things and have effective plans in place to ensure good performance on each. And if you haven’t already, you should add at least one more important issue to this list—the transition to ICD-10 coding on Oct. 1, 2014.

An Overview

ICD stands for International Classification of Diseases, and the U.S. has been using the 9th revision (ICD-9) since 1978. ICD-9 is now significantly out of step with current medical knowledge and has run out of codes in some disease sections (“chapters”). This might mean, for example, that new codes for heart diseases would be assigned to the chapter for eye disease, because the former is full.

ICD-10 provides a way to fix these problems and, through more specific coding of diseases, should be able to yield more useful “big data” to measure things like safety and efficacy of care and more accurately identify diagnosis trends and epidemics. And, in theory, it could reduce the number of rejected billing claims, though I’m waiting to see if that happens. I worry that even after fixing all the initial bugs related to the ICD-10 transition, we will see more claim rejections than we experience today.

ICD codes can be thought of as diagnosis codes. CPT codes (Current Procedural Terminology) are an entirely separate set of codes that we use to report the work we do for the purposes of billing. We need to be familiar with both, but it is the ICD codes that are changing.

ICD-10 Basics and Trivia

The World Health Organization issued the ICD-10 in 1994, and it is already in use in many countries. Like some other countries, the U.S. made modifications to the WHO’s original code set, so we refer to ICD-10-CM (Clinical Modification), which contains diagnosis codes. The National Center for Health Statistics, a department of the CDC, is responsible for these modifications.

The WHO version of ICD-10 doesn’t have any procedure codes, so CMS developed ICD-10-PCS (Procedure Coding System) to report procedures, such as surgeries, done in U.S. hospitals. Most hospitalists won’t use these procedure codes often.

Table 1 (left) compares ICD-10-CM to ICD-9-CM. Most of the additional codes in the new version simply add information regarding whether the diagnosis is on the left or right of the body, acute or chronic, or an initial or subsequent visit for the condition. But the standard structure for each code had to be modified significantly to capture this additional information. Some highlights of the seven-character code structure are:

- Characters 1–3: category; first digit always a letter, second digit always a number, all other digits can be either; not case sensitive;

- Characters 4–6: etiology, anatomic site, severity, or other clinical detail; for example, 1=right, 2=left, 3-bilateral, and 0 or 9=unspecified; and

- Character 7: extension (i.e., A=initial encounter, D=subsequent encounter, S=sequelae).

- A placeholder “x” is used as needed to fill in empty characters to ensure that the seventh character stays in the seventh position. For example, T79.1xxA equates to “fat embolism, initial encounter.” (Note that the “dummy” characters could create problems for some IT systems.)

An example of more information contained in additional characters:

- S52=fracture of forearm.

- S52.5=fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.52=torus fracture of lower end of radius.

- S52.521=torus fracture of lower end of right radius.

- S52.521A=torus fracture of lower end of right radius, initial encounter for closed fracture.

Compared to its predecessor, ICD-10 expands use of combination codes. These are single codes that can be used to classify either two diagnoses, a diagnosis with an associated secondary process, or a diagnosis with an associated complication. For example, rather than reporting acute cor pulmonale and septic pulmonary embolism separately, ICD-10 allows use of the code I26.01: septic pulmonary embolism with acute cor pulmonale.

Resources

In addition to resources on the SHM website, both the American Medical Association (www.ama-assn.org, search “ICD-10”) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.gov/icd10) have very informative microsites offering detailed ICD-10 information. Much of the information in this column, including the examples above, comes from those sites.

What to Expect

Your hospital and your employer are probably already working in earnest to prepare for the change. In some cases, hospitalists are actively involved in these preparations, but in most cases they will simply wait for an organization to notify them that they should begin training to understand the new coding system. Experts say that most physicians will need two to four hours of training on ICD-10, but because we use a universe of diagnosis codes that is much larger than many specialties, I wonder if hospitalists may need additional training.

Like nearly all the programs I listed at the beginning, the transition to ICD-10 has me concerned. Managing it poorly could mean significant loss in hospital and physician professional fee revenue, as well as lots of tedious and time-consuming work. So, doing it right is important. But, it is also important to do well on all the programs I listed at the beginning of this column, and many others, and there is a limit to just how much we can do effectively as individuals.

Collectively, these programs risk taking too much time and too many brain cells away from keeping up with clinical medicine. So, I wonder if, for many of us, ICD-10 will serve as a tipping point that results in physicians hiring professional coders to choose our diagnosis codes and CPT codes rather than doing it ourselves.

As with EHRs, ICD-10 is said to have many benefits. But the introduction of EHRs in many hospitals had the unintended effect of significantly reducing the number of doctors who were willing to serve as admitting and attending physicians; instead, many chose to refer to hospitalists. In a similar way, ICD-10 might lead many organizations to relieve physicians of the responsibility of looking up and entering codes for each patient, leaving them with more time and energy to be clinicians. We’ll have to wait and see.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Large Hospital Systems, Physician Groups Most Likely to Form Accountable Care Organizations

The environment that breeds the formation of accountable care organizations (ACOs) includes large integrated hospital systems, primary care physicians (PCPs) practicing in large groups, and a greater fraction of hospital risk sharing, according to a Health Affairs report (http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/10/1781.abstract).

In other words, institutions and areas that have begun embracing risk-based or population-based payment models are more likely to spur the formation of ACOs, which have similar risk-reward payment structures.

For hospitalists, knowing the conditions that help foster ACOs may be an important first step in pushing for development and continued growth, says Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM Public Policy Committee chair and chief medical officer of Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn.

It’s a shift in mindset for sure, says the report’s lead author.

“The traditional model is pretty much fill your beds with high-paying patients. An ACO is really a different kind of concept,” says David Auerbach, MS, PhD, of Boston-based RAND Corporation. “A hospital that doesn’t have any experience thinking in a different way is going to find it hard to accommodate the ACO payment model. But hospitals that do…probably have staff that have thought about this and already started to move down the path to thinking about ways to reduce their costs.”

Regional Variance

Dr. Auerbach, a policy researcher and affiliate faculty member at Pardee RAND Graduate School, says further work needs to be done to identify “key regional factors” that induce certain physicians and hospitals to launch ACOs. His paper, “Accountable Care Organization Formation Is Associated with Integrated Systems but Not High Medical Spending,” found wide disparities in ACO formation; the model is popular in the Northeast and Midwest regions but scarcely found in the Northwest.

—Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM’s Public Policy Committee chair, chief medical officer, Cogent HMG, Brentwood, Tenn.

The authors reviewed 32 Medicare Pioneer ACOs, 116 Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and 77 private-market entities very similar to ACOs. The study’s multiple-regression analysis found that in the 31 regions with at least 20% of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in an ACO, more than half of hospitals had a joint venture with doctors or physician groups and were affiliated with a health system. In so-called “low-ACO areas,” that percentage hovered around 30% to 40%.

And while much of the policy discussion focuses on whether ACOs can rein in healthcare spending in some of the markets where care costs the most, the study reported “no strong pattern in the relationship between ACO penetration and Medicare spending or spending growth.”

Uncertain Upside

Dr. Auerbach says that while the results of his paper did not surprise him, he hopes hospitalists and others use them educationally.

“We might think about there being demand from people in other areas that might say, ‘I want to be a part of that too. Why aren’t there any ACOs that I can be in?’” he adds. “And so a study like this says, ‘Here are some of the things that seem to be important.’ If there’s not this kind of infrastructure in your area, as a policy maker, you could go and say, ‘Let’s try and give a boost to some of these factors or proxies for these things.’”

Part of that review would include looking at those areas that saw higher rates of physician-institution consolidation and figuring out what the motivations were. Typically, the impetus of forming larger groups is partly explained by a desire to negotiate with insurers and get better deals, Dr. Auerbach says. But with more coordinated care comes a more efficient system that can offset those lower rates.

“I think right now most policymakers are not sure if the upside is better than the downside,” he adds. “I think the answer, personally, is not to try to break up providers and do a lot of anti-trust activity. We need to understand whether, and how much, integrated groups are able to use market power to charge higher prices. And, if they do, there may be other ways to combat that problem while keeping the groups intact.”

Rethinking Reimbursement

Dr. Greeno says growing pains are inevitable along the way, particularly because the move to the ACO payment model is a seismic shift for a healthcare industry that has traditionally been based on a fee-for-service model.

“How we pay for healthcare in this country is going to be completely flipped on its head,” he says. “Part of the goal, of course, is better outcomes for patients. But it’s also cost efficiency. In the meantime, the entire system for 100 years has been paying for production.”

Dr. Greeno compares it to the shift that was the managed-care movement. Moving forward, the shift will create winners and losers and most likely will result in massive consolidation of healthcare organizations—from nearly 700 today to what Dr. Greeno believes may be 50 to 70 mega-providers.

“It’s basically what happened when HMOs started paying capitated payments to physician groups,” he says. “The groups then had X amount of dollars to care for their patient population, and if they couldn’t make that work, they went out of business or were acquired by more successful groups. If they could make it work, then they survived. It’s the exact same thing. It’s not quite as dramatic, as it is not going to happen overnight, but that’s where it’s heading.

“And instead of occurring in pockets around the country like in Southern California and Minneapolis, it’s going to be nationwide, and the world’s largest insurance company, which is Medicare, is driving it.”

Dr. Auerbach notes that while the disruption already has caused some groups to drop out of the ACO programs, he does not see that as a precursor to more organizations turning away from the program, particularly as it is among the key planks of the general healthcare reform movement.

“It is part of a larger wave that really is changing the way we do healthcare,” he says. “I think that as [ACOs] grow...people are going to say that this is becoming something like the dominant form of delivering healthcare.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The environment that breeds the formation of accountable care organizations (ACOs) includes large integrated hospital systems, primary care physicians (PCPs) practicing in large groups, and a greater fraction of hospital risk sharing, according to a Health Affairs report (http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/10/1781.abstract).

In other words, institutions and areas that have begun embracing risk-based or population-based payment models are more likely to spur the formation of ACOs, which have similar risk-reward payment structures.

For hospitalists, knowing the conditions that help foster ACOs may be an important first step in pushing for development and continued growth, says Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM Public Policy Committee chair and chief medical officer of Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn.

It’s a shift in mindset for sure, says the report’s lead author.

“The traditional model is pretty much fill your beds with high-paying patients. An ACO is really a different kind of concept,” says David Auerbach, MS, PhD, of Boston-based RAND Corporation. “A hospital that doesn’t have any experience thinking in a different way is going to find it hard to accommodate the ACO payment model. But hospitals that do…probably have staff that have thought about this and already started to move down the path to thinking about ways to reduce their costs.”

Regional Variance

Dr. Auerbach, a policy researcher and affiliate faculty member at Pardee RAND Graduate School, says further work needs to be done to identify “key regional factors” that induce certain physicians and hospitals to launch ACOs. His paper, “Accountable Care Organization Formation Is Associated with Integrated Systems but Not High Medical Spending,” found wide disparities in ACO formation; the model is popular in the Northeast and Midwest regions but scarcely found in the Northwest.

—Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM’s Public Policy Committee chair, chief medical officer, Cogent HMG, Brentwood, Tenn.

The authors reviewed 32 Medicare Pioneer ACOs, 116 Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and 77 private-market entities very similar to ACOs. The study’s multiple-regression analysis found that in the 31 regions with at least 20% of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in an ACO, more than half of hospitals had a joint venture with doctors or physician groups and were affiliated with a health system. In so-called “low-ACO areas,” that percentage hovered around 30% to 40%.

And while much of the policy discussion focuses on whether ACOs can rein in healthcare spending in some of the markets where care costs the most, the study reported “no strong pattern in the relationship between ACO penetration and Medicare spending or spending growth.”

Uncertain Upside

Dr. Auerbach says that while the results of his paper did not surprise him, he hopes hospitalists and others use them educationally.

“We might think about there being demand from people in other areas that might say, ‘I want to be a part of that too. Why aren’t there any ACOs that I can be in?’” he adds. “And so a study like this says, ‘Here are some of the things that seem to be important.’ If there’s not this kind of infrastructure in your area, as a policy maker, you could go and say, ‘Let’s try and give a boost to some of these factors or proxies for these things.’”

Part of that review would include looking at those areas that saw higher rates of physician-institution consolidation and figuring out what the motivations were. Typically, the impetus of forming larger groups is partly explained by a desire to negotiate with insurers and get better deals, Dr. Auerbach says. But with more coordinated care comes a more efficient system that can offset those lower rates.

“I think right now most policymakers are not sure if the upside is better than the downside,” he adds. “I think the answer, personally, is not to try to break up providers and do a lot of anti-trust activity. We need to understand whether, and how much, integrated groups are able to use market power to charge higher prices. And, if they do, there may be other ways to combat that problem while keeping the groups intact.”

Rethinking Reimbursement

Dr. Greeno says growing pains are inevitable along the way, particularly because the move to the ACO payment model is a seismic shift for a healthcare industry that has traditionally been based on a fee-for-service model.

“How we pay for healthcare in this country is going to be completely flipped on its head,” he says. “Part of the goal, of course, is better outcomes for patients. But it’s also cost efficiency. In the meantime, the entire system for 100 years has been paying for production.”

Dr. Greeno compares it to the shift that was the managed-care movement. Moving forward, the shift will create winners and losers and most likely will result in massive consolidation of healthcare organizations—from nearly 700 today to what Dr. Greeno believes may be 50 to 70 mega-providers.

“It’s basically what happened when HMOs started paying capitated payments to physician groups,” he says. “The groups then had X amount of dollars to care for their patient population, and if they couldn’t make that work, they went out of business or were acquired by more successful groups. If they could make it work, then they survived. It’s the exact same thing. It’s not quite as dramatic, as it is not going to happen overnight, but that’s where it’s heading.

“And instead of occurring in pockets around the country like in Southern California and Minneapolis, it’s going to be nationwide, and the world’s largest insurance company, which is Medicare, is driving it.”

Dr. Auerbach notes that while the disruption already has caused some groups to drop out of the ACO programs, he does not see that as a precursor to more organizations turning away from the program, particularly as it is among the key planks of the general healthcare reform movement.

“It is part of a larger wave that really is changing the way we do healthcare,” he says. “I think that as [ACOs] grow...people are going to say that this is becoming something like the dominant form of delivering healthcare.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The environment that breeds the formation of accountable care organizations (ACOs) includes large integrated hospital systems, primary care physicians (PCPs) practicing in large groups, and a greater fraction of hospital risk sharing, according to a Health Affairs report (http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/10/1781.abstract).

In other words, institutions and areas that have begun embracing risk-based or population-based payment models are more likely to spur the formation of ACOs, which have similar risk-reward payment structures.

For hospitalists, knowing the conditions that help foster ACOs may be an important first step in pushing for development and continued growth, says Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM Public Policy Committee chair and chief medical officer of Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn.

It’s a shift in mindset for sure, says the report’s lead author.

“The traditional model is pretty much fill your beds with high-paying patients. An ACO is really a different kind of concept,” says David Auerbach, MS, PhD, of Boston-based RAND Corporation. “A hospital that doesn’t have any experience thinking in a different way is going to find it hard to accommodate the ACO payment model. But hospitals that do…probably have staff that have thought about this and already started to move down the path to thinking about ways to reduce their costs.”

Regional Variance

Dr. Auerbach, a policy researcher and affiliate faculty member at Pardee RAND Graduate School, says further work needs to be done to identify “key regional factors” that induce certain physicians and hospitals to launch ACOs. His paper, “Accountable Care Organization Formation Is Associated with Integrated Systems but Not High Medical Spending,” found wide disparities in ACO formation; the model is popular in the Northeast and Midwest regions but scarcely found in the Northwest.

—Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, SHM’s Public Policy Committee chair, chief medical officer, Cogent HMG, Brentwood, Tenn.

The authors reviewed 32 Medicare Pioneer ACOs, 116 Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and 77 private-market entities very similar to ACOs. The study’s multiple-regression analysis found that in the 31 regions with at least 20% of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in an ACO, more than half of hospitals had a joint venture with doctors or physician groups and were affiliated with a health system. In so-called “low-ACO areas,” that percentage hovered around 30% to 40%.

And while much of the policy discussion focuses on whether ACOs can rein in healthcare spending in some of the markets where care costs the most, the study reported “no strong pattern in the relationship between ACO penetration and Medicare spending or spending growth.”

Uncertain Upside

Dr. Auerbach says that while the results of his paper did not surprise him, he hopes hospitalists and others use them educationally.

“We might think about there being demand from people in other areas that might say, ‘I want to be a part of that too. Why aren’t there any ACOs that I can be in?’” he adds. “And so a study like this says, ‘Here are some of the things that seem to be important.’ If there’s not this kind of infrastructure in your area, as a policy maker, you could go and say, ‘Let’s try and give a boost to some of these factors or proxies for these things.’”

Part of that review would include looking at those areas that saw higher rates of physician-institution consolidation and figuring out what the motivations were. Typically, the impetus of forming larger groups is partly explained by a desire to negotiate with insurers and get better deals, Dr. Auerbach says. But with more coordinated care comes a more efficient system that can offset those lower rates.

“I think right now most policymakers are not sure if the upside is better than the downside,” he adds. “I think the answer, personally, is not to try to break up providers and do a lot of anti-trust activity. We need to understand whether, and how much, integrated groups are able to use market power to charge higher prices. And, if they do, there may be other ways to combat that problem while keeping the groups intact.”

Rethinking Reimbursement

Dr. Greeno says growing pains are inevitable along the way, particularly because the move to the ACO payment model is a seismic shift for a healthcare industry that has traditionally been based on a fee-for-service model.

“How we pay for healthcare in this country is going to be completely flipped on its head,” he says. “Part of the goal, of course, is better outcomes for patients. But it’s also cost efficiency. In the meantime, the entire system for 100 years has been paying for production.”

Dr. Greeno compares it to the shift that was the managed-care movement. Moving forward, the shift will create winners and losers and most likely will result in massive consolidation of healthcare organizations—from nearly 700 today to what Dr. Greeno believes may be 50 to 70 mega-providers.

“It’s basically what happened when HMOs started paying capitated payments to physician groups,” he says. “The groups then had X amount of dollars to care for their patient population, and if they couldn’t make that work, they went out of business or were acquired by more successful groups. If they could make it work, then they survived. It’s the exact same thing. It’s not quite as dramatic, as it is not going to happen overnight, but that’s where it’s heading.

“And instead of occurring in pockets around the country like in Southern California and Minneapolis, it’s going to be nationwide, and the world’s largest insurance company, which is Medicare, is driving it.”

Dr. Auerbach notes that while the disruption already has caused some groups to drop out of the ACO programs, he does not see that as a precursor to more organizations turning away from the program, particularly as it is among the key planks of the general healthcare reform movement.

“It is part of a larger wave that really is changing the way we do healthcare,” he says. “I think that as [ACOs] grow...people are going to say that this is becoming something like the dominant form of delivering healthcare.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hospital Costs for Inpatients with Septicemia Total $20.3 Billion in 2011

Total annual cost of hospital care for septicemia (excluding patients in labor) in U.S. hospitals in 2011.

The figure represents 1.094 million discharges. It’s the first among 20 big-ticket medical conditions listed in an August 2013 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical Brief, highlighted in Becker’s Hospital Review.3,4

Other high-cost conditions on the list were osteoarthritis ($14.8 billion; 964,000 discharges); complications of device, implement, or graft (12.9 billion; 699,000 discharges); and general childbirth (12.4 billion; 3,819,000).

References

- Chang W, Maynard G, Clay B. Implementation of a computerized COPD inpatient pathway and transition pathway [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8 Suppl 1:709.

- Schmitt S, McQuillen DP, Nahass R, et al. Infectious diseases specialty intervention is associated with decreased mortality and lower healthcare costs [published online ahead of print September 25, 2013]. Clin Infect Dis.

- Torio CM, Andrews RM. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2011. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #160. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb160.jsp. Accessed October 26, 2013.

- Herman B. Top 20 most expensive inpatient conditions. Becker’s Hospital Review. Oct. 9, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/racs-/-icd-9-/-icd-10/top-20-most-expensive-inpatient-conditions.html. Accessed October 26, 2013.

Total annual cost of hospital care for septicemia (excluding patients in labor) in U.S. hospitals in 2011.

The figure represents 1.094 million discharges. It’s the first among 20 big-ticket medical conditions listed in an August 2013 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical Brief, highlighted in Becker’s Hospital Review.3,4

Other high-cost conditions on the list were osteoarthritis ($14.8 billion; 964,000 discharges); complications of device, implement, or graft (12.9 billion; 699,000 discharges); and general childbirth (12.4 billion; 3,819,000).

References

- Chang W, Maynard G, Clay B. Implementation of a computerized COPD inpatient pathway and transition pathway [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8 Suppl 1:709.

- Schmitt S, McQuillen DP, Nahass R, et al. Infectious diseases specialty intervention is associated with decreased mortality and lower healthcare costs [published online ahead of print September 25, 2013]. Clin Infect Dis.

- Torio CM, Andrews RM. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2011. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #160. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb160.jsp. Accessed October 26, 2013.

- Herman B. Top 20 most expensive inpatient conditions. Becker’s Hospital Review. Oct. 9, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/racs-/-icd-9-/-icd-10/top-20-most-expensive-inpatient-conditions.html. Accessed October 26, 2013.

Total annual cost of hospital care for septicemia (excluding patients in labor) in U.S. hospitals in 2011.

The figure represents 1.094 million discharges. It’s the first among 20 big-ticket medical conditions listed in an August 2013 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical Brief, highlighted in Becker’s Hospital Review.3,4

Other high-cost conditions on the list were osteoarthritis ($14.8 billion; 964,000 discharges); complications of device, implement, or graft (12.9 billion; 699,000 discharges); and general childbirth (12.4 billion; 3,819,000).

References

- Chang W, Maynard G, Clay B. Implementation of a computerized COPD inpatient pathway and transition pathway [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8 Suppl 1:709.

- Schmitt S, McQuillen DP, Nahass R, et al. Infectious diseases specialty intervention is associated with decreased mortality and lower healthcare costs [published online ahead of print September 25, 2013]. Clin Infect Dis.

- Torio CM, Andrews RM. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2011. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #160. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb160.jsp. Accessed October 26, 2013.

- Herman B. Top 20 most expensive inpatient conditions. Becker’s Hospital Review. Oct. 9, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/racs-/-icd-9-/-icd-10/top-20-most-expensive-inpatient-conditions.html. Accessed October 26, 2013.

How to Handle Medicare Documentation Audits

The recent announcement of a settlement by a physician firm should cause the HM community to pause and take inventory. The settlement “addressed allegations that, between 2004 and 2012, [the firm] knowingly submitted to federal health benefits programs inflated claims on behalf of its hospitalist employees for higher and more expensive levels of service than were documented by hospitalists in patient medical records.”1

This civil settlement highlights the vigilance being exercised against healthcare fraud and demonstrates the coordinated efforts in place to tackle the issue. To put the weight of this case in perspective, consider the breadth of legal entities involved: the U.S. Department of Justice; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management; the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; and the TRICARE Management Activity Office of General Counsel.1

The underlying factor in the settlement is a common issue routinely identified by Medicare-initiated review programs such as CERT (Comprehensive Error Rate Testing). CERT selects a stratified, random sample of approximately 40,000 claims submitted to Part A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and Durable Medical Equipment MACs (DME MACs) during each reporting period and allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to calculate a national improper payment rate and contractor- and service-specific improper payment rates.2 The CERT-determined improper payment rate identifies services that have not satisfied Medicare requirements, but it cannot label a claim fraudulent.2

Incorrect coding errors involving hospitalists are related to inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services that do not adequately reflect the documentation in the medical record. For example, WPS Medicare identified the following error rates for claims submitted 7/1/11 to 6/30/12: 45% of 99223 (initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires these three key components: a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity); and 34% of 99233 (subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, and medical decision-making of high complexity).3,4 More recent WPS Medicare data in first quarter of FY2013 reveals a continuing problem but an improved error rate.5 Novitas Solutions offers additional support of these findings.6

Based on efforts that identify improper payments, MACs are encouraged to initiate targeted service-specific prepayment review to prevent improper payments for services identified by CERT or recovery audit contractors (RACs) as problem areas, as well as problem areas identified by their own data analysis.7 For this reason, hospitalists may see prepayment requests for documentation by Medicare for services that are most “problematic” (e.g., 99223 and 99233). This occurs when a claim involving these services is submitted to Medicare. The MAC suspends all or part of a claim so that a trained clinician or claims analyst can review the claim and associated documentation in order to make determinations about coverage and payment.7 Responding to these requests in a timely manner is crucial in preventing claim denials.

Responding to Requests

When documentation is requested by the payor, take note of the date and the provider for whom the service is requested. Be certain to include all pertinent information in support of the claim. The payor request letter will typically include a generic list of items that should be submitted with the documentation request. Consider these particular items when submitting documentation for targeted services typically provided by hospitalists:

- Initial Hospital Care (99223)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify any referenced sources of information (e.g., physician referencing a family history documented in the ED record);

- Dictations, when performed;

- Admitting orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on admission.

- Subsequent Hospital Care (99233)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify multiple encounters/entries recorded on a given date;

- Physician orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on the requested date.

Documentation Tips

Because it is the primary communication tool for providers involved in the patient’s care, documentation must be entered in a timely manner and must be decipherable to members of the healthcare team as well as other individuals who may need to review the information (e.g., auditors). Proper credit cannot be given for documentation that is difficult to read.

Information should include historical review of past/interim events, a physical exam, medical decision-making as related to the patient’s progress/response to intervention, and modification of the care plan (as necessary). The reason for the encounter should be evident to support the medical necessity of the service. Because various specialists may participate in patient care, documentation for each provider’s encounter should demonstrate personalized and non-duplicative care.

Each individual provider must exhibit a personal contribution to the case to prevent payors from viewing the documentation as overlapping and indistinguishable from care already provided by another physician. Each entry should be dated and signed with a legible identifier (i.e., signature with a printed name).

The next several articles will address each of the key components (history, exam, and decision-making) and serve as a “documentation refresher” for providers who wish to compare their documentation to current standards.

References

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. Tacoma, Wash., Medical Firm to Pay $14.5 Million to Settle Overbilling Allegations. Available at: www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/July/13-civ-758.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT). Available at: www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/CERT/index.html?redirect=/cert. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. Are you billing these evaluation and management (e/m) services correctly? Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2011-0912-billemservices.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis, L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012:15-17.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. 1st Qtr. 2013 (Jan. - Mar.) - CERT Error Summary. Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2013-1st-quarter-summary.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Novitas Solutions. Analysis of JL Part B Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) Data - January thru March 2013. Available at: https://www.novitas-solutions.com/cert/errors/2013/b-jan-mar-j12.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program Integrity Manual, Chapter 3, Section 3.2. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/pim83c03.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 11, Section 40.1.2 Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c11.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

The recent announcement of a settlement by a physician firm should cause the HM community to pause and take inventory. The settlement “addressed allegations that, between 2004 and 2012, [the firm] knowingly submitted to federal health benefits programs inflated claims on behalf of its hospitalist employees for higher and more expensive levels of service than were documented by hospitalists in patient medical records.”1

This civil settlement highlights the vigilance being exercised against healthcare fraud and demonstrates the coordinated efforts in place to tackle the issue. To put the weight of this case in perspective, consider the breadth of legal entities involved: the U.S. Department of Justice; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management; the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; and the TRICARE Management Activity Office of General Counsel.1

The underlying factor in the settlement is a common issue routinely identified by Medicare-initiated review programs such as CERT (Comprehensive Error Rate Testing). CERT selects a stratified, random sample of approximately 40,000 claims submitted to Part A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and Durable Medical Equipment MACs (DME MACs) during each reporting period and allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to calculate a national improper payment rate and contractor- and service-specific improper payment rates.2 The CERT-determined improper payment rate identifies services that have not satisfied Medicare requirements, but it cannot label a claim fraudulent.2

Incorrect coding errors involving hospitalists are related to inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services that do not adequately reflect the documentation in the medical record. For example, WPS Medicare identified the following error rates for claims submitted 7/1/11 to 6/30/12: 45% of 99223 (initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires these three key components: a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity); and 34% of 99233 (subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, and medical decision-making of high complexity).3,4 More recent WPS Medicare data in first quarter of FY2013 reveals a continuing problem but an improved error rate.5 Novitas Solutions offers additional support of these findings.6

Based on efforts that identify improper payments, MACs are encouraged to initiate targeted service-specific prepayment review to prevent improper payments for services identified by CERT or recovery audit contractors (RACs) as problem areas, as well as problem areas identified by their own data analysis.7 For this reason, hospitalists may see prepayment requests for documentation by Medicare for services that are most “problematic” (e.g., 99223 and 99233). This occurs when a claim involving these services is submitted to Medicare. The MAC suspends all or part of a claim so that a trained clinician or claims analyst can review the claim and associated documentation in order to make determinations about coverage and payment.7 Responding to these requests in a timely manner is crucial in preventing claim denials.

Responding to Requests

When documentation is requested by the payor, take note of the date and the provider for whom the service is requested. Be certain to include all pertinent information in support of the claim. The payor request letter will typically include a generic list of items that should be submitted with the documentation request. Consider these particular items when submitting documentation for targeted services typically provided by hospitalists:

- Initial Hospital Care (99223)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify any referenced sources of information (e.g., physician referencing a family history documented in the ED record);

- Dictations, when performed;

- Admitting orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on admission.

- Subsequent Hospital Care (99233)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify multiple encounters/entries recorded on a given date;

- Physician orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on the requested date.

Documentation Tips

Because it is the primary communication tool for providers involved in the patient’s care, documentation must be entered in a timely manner and must be decipherable to members of the healthcare team as well as other individuals who may need to review the information (e.g., auditors). Proper credit cannot be given for documentation that is difficult to read.

Information should include historical review of past/interim events, a physical exam, medical decision-making as related to the patient’s progress/response to intervention, and modification of the care plan (as necessary). The reason for the encounter should be evident to support the medical necessity of the service. Because various specialists may participate in patient care, documentation for each provider’s encounter should demonstrate personalized and non-duplicative care.

Each individual provider must exhibit a personal contribution to the case to prevent payors from viewing the documentation as overlapping and indistinguishable from care already provided by another physician. Each entry should be dated and signed with a legible identifier (i.e., signature with a printed name).

The next several articles will address each of the key components (history, exam, and decision-making) and serve as a “documentation refresher” for providers who wish to compare their documentation to current standards.

References

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. Tacoma, Wash., Medical Firm to Pay $14.5 Million to Settle Overbilling Allegations. Available at: www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/July/13-civ-758.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.