User login

Tinea capitis

THE COMPARISON

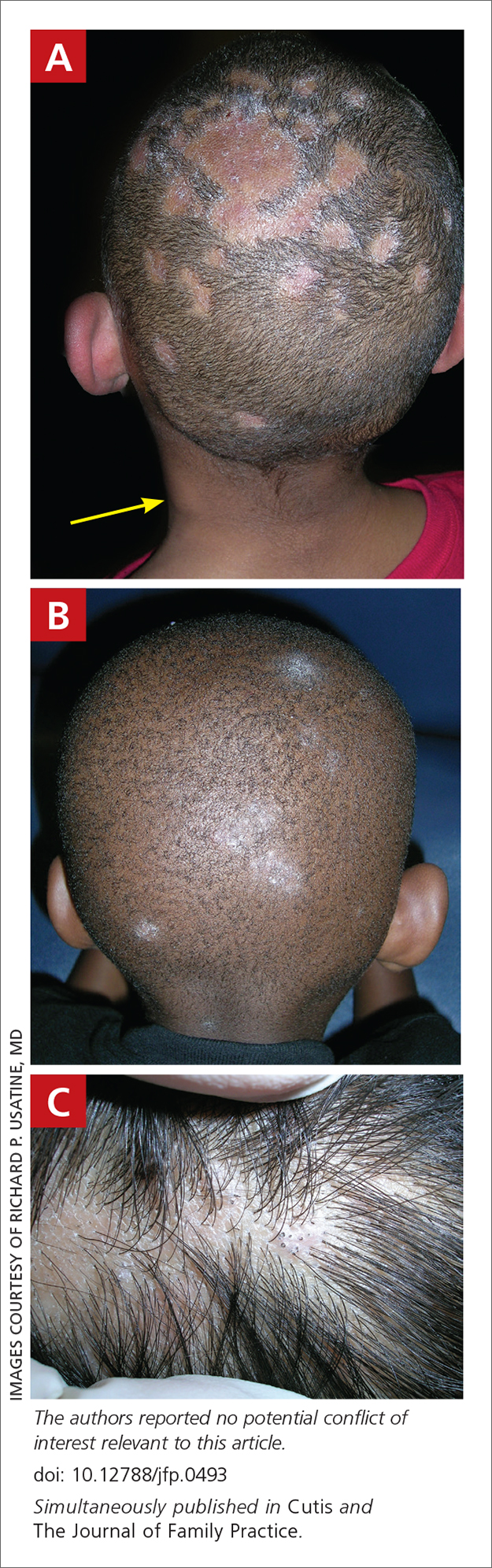

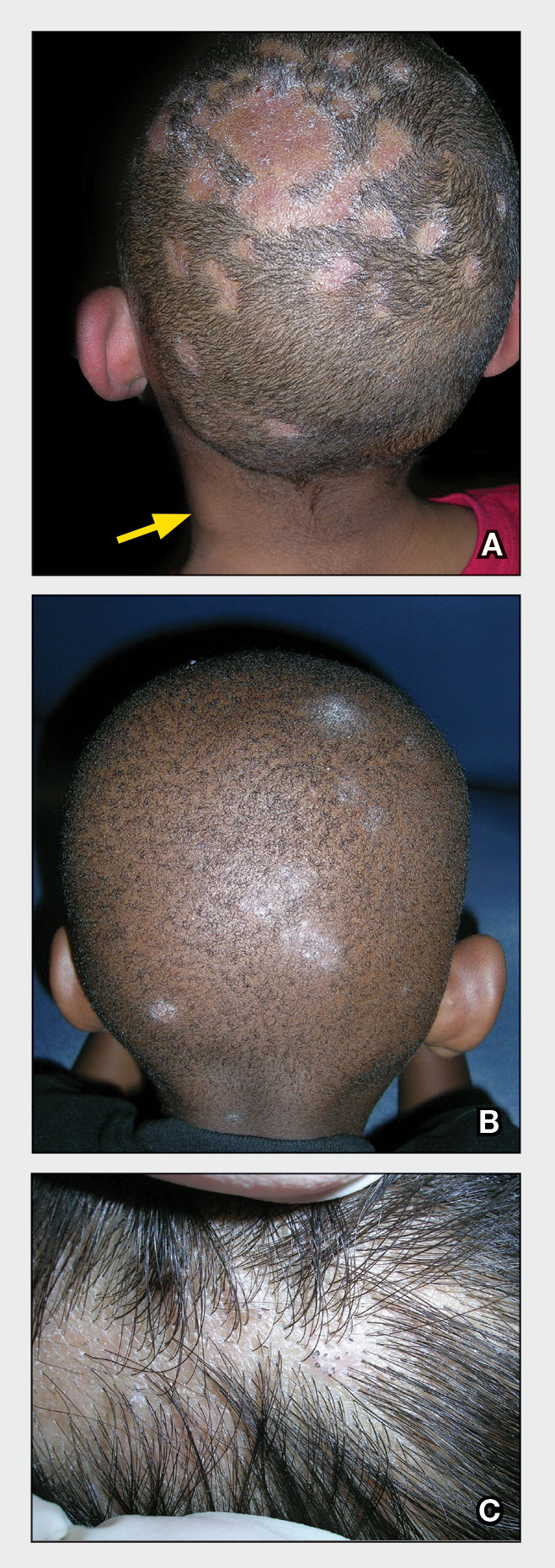

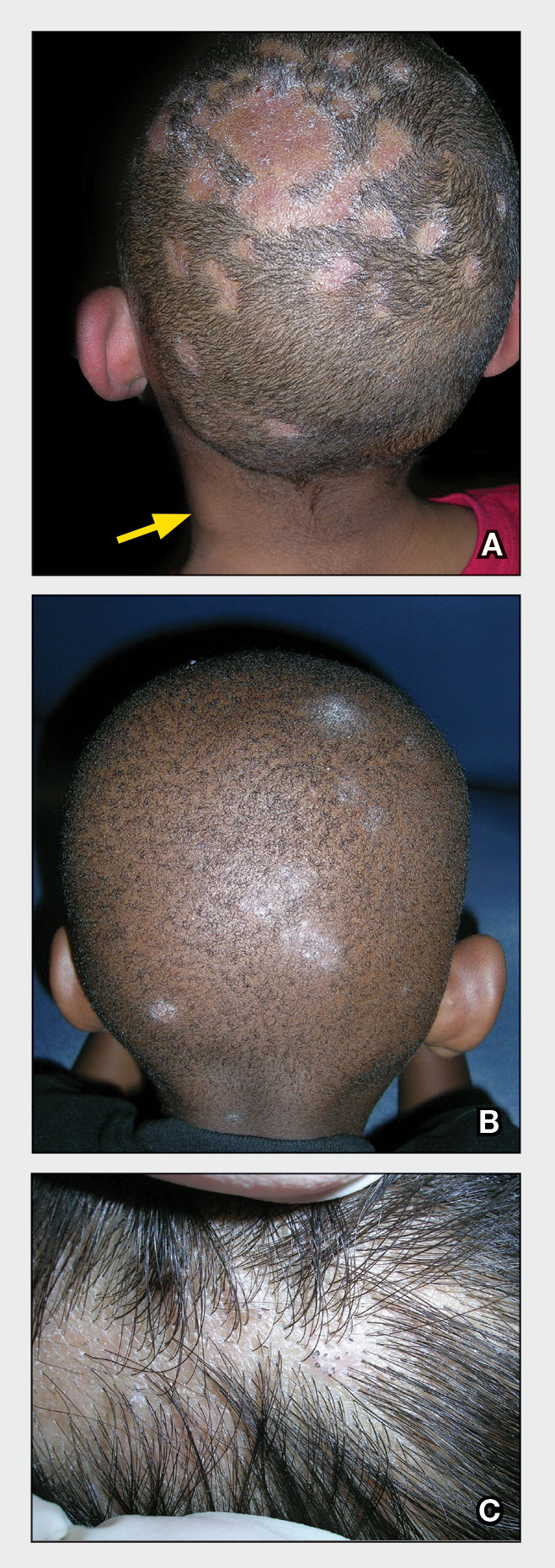

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

THE COMPARISON

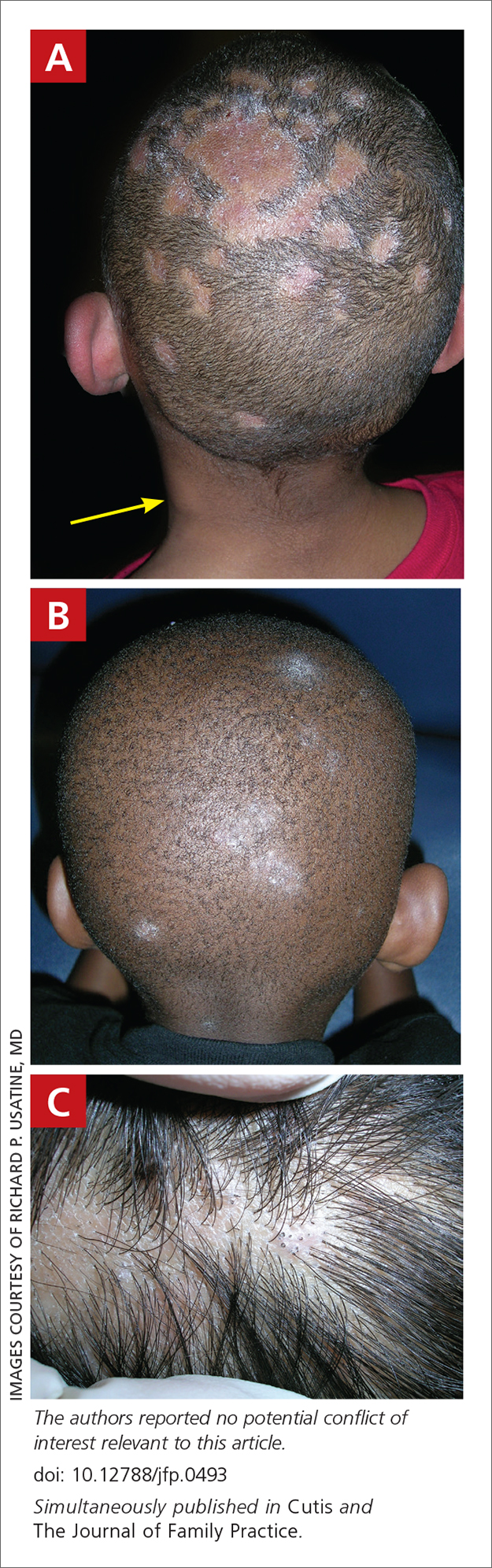

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

Tinea Capitis

THE COMPARISON

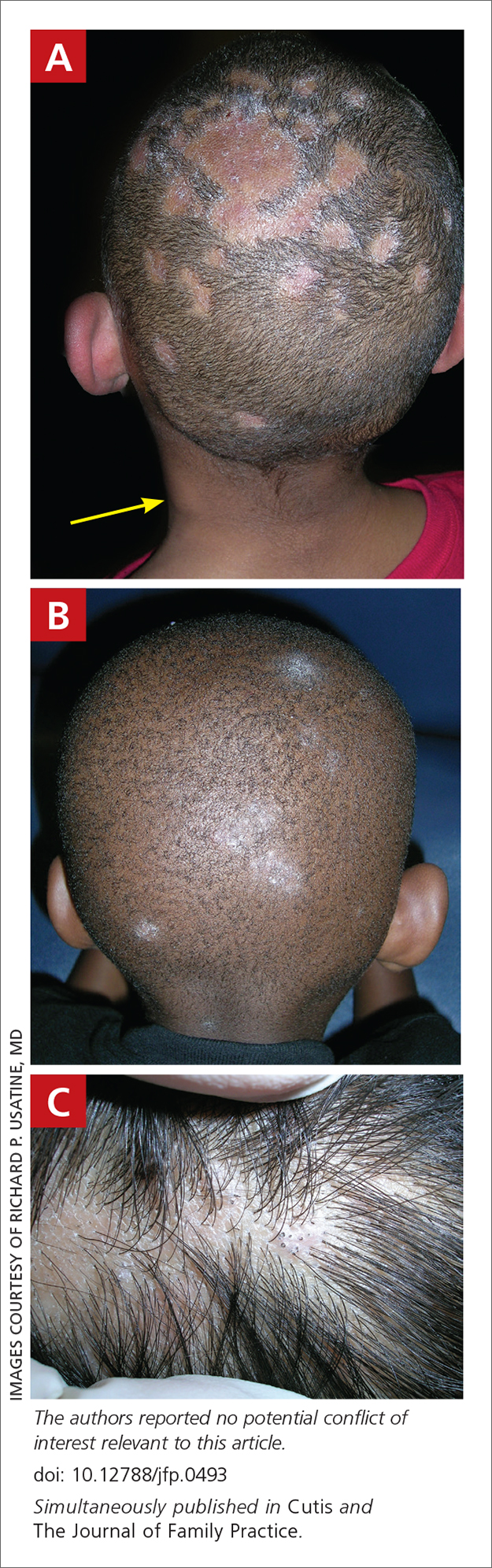

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

THE COMPARISON

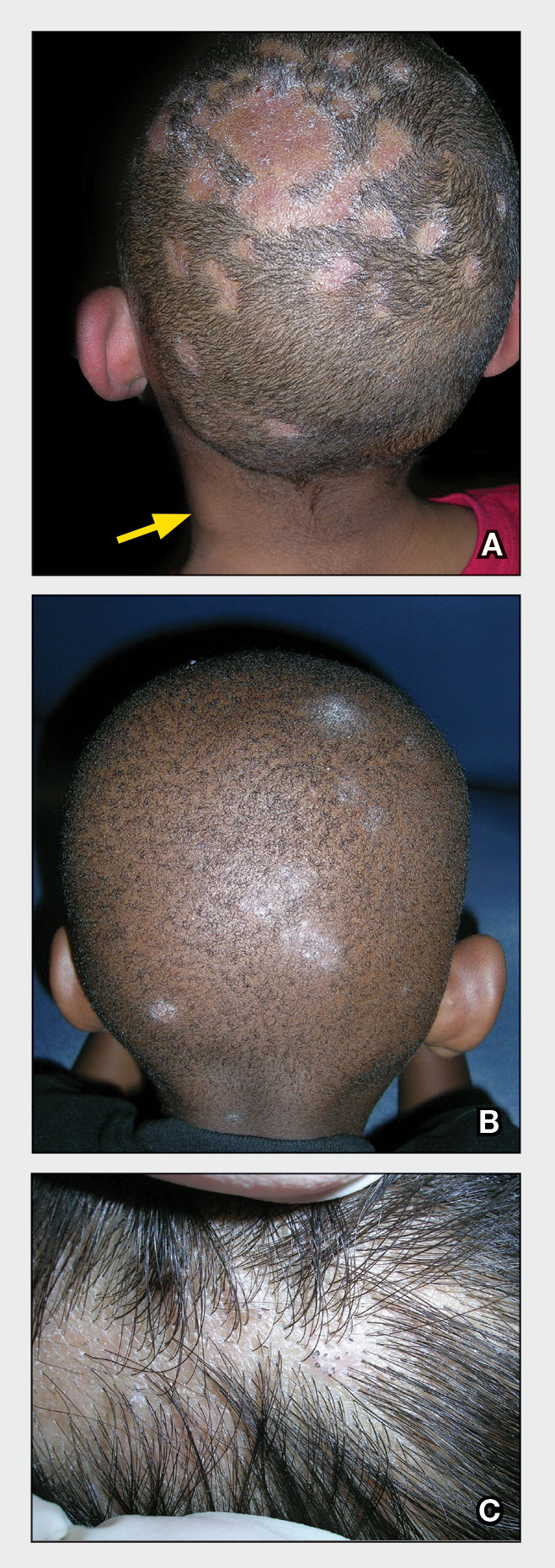

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

Hidradenitis suppurativa

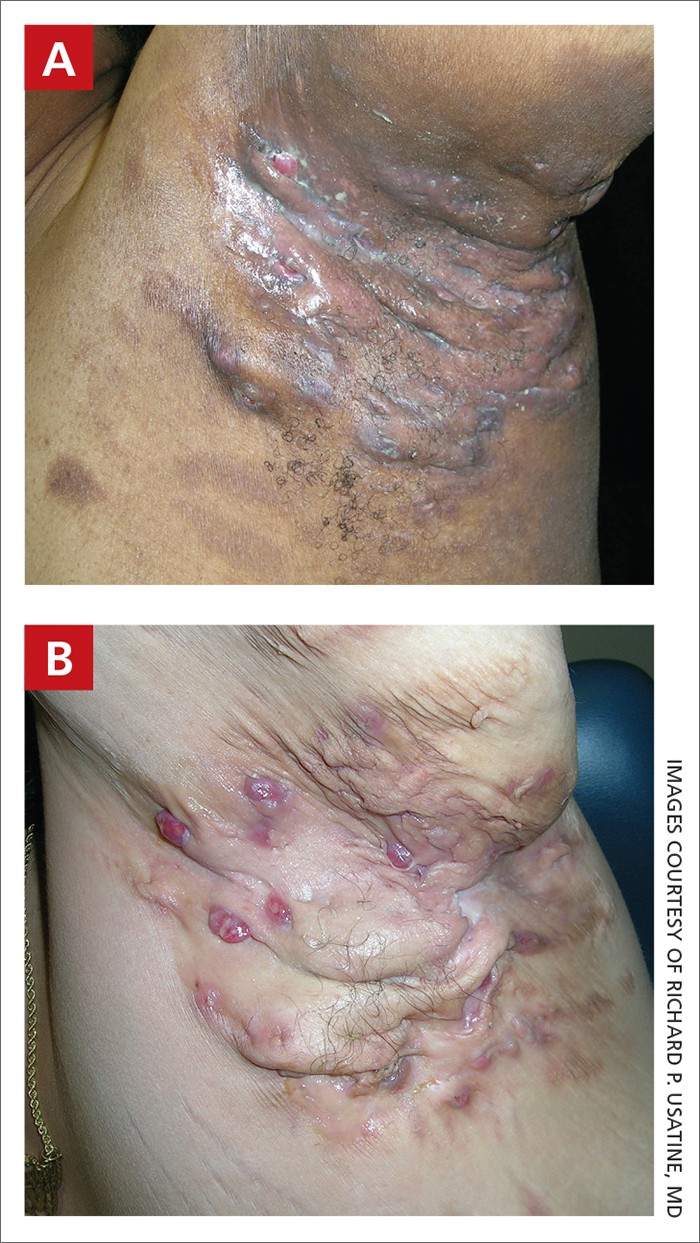

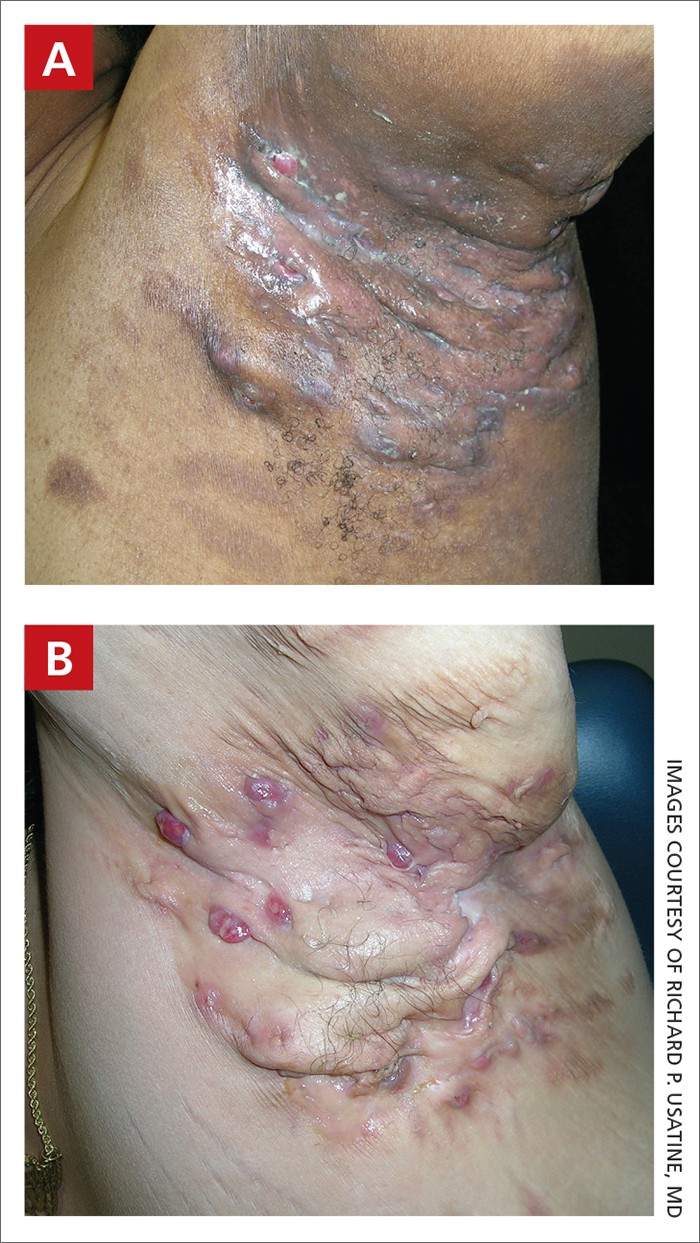

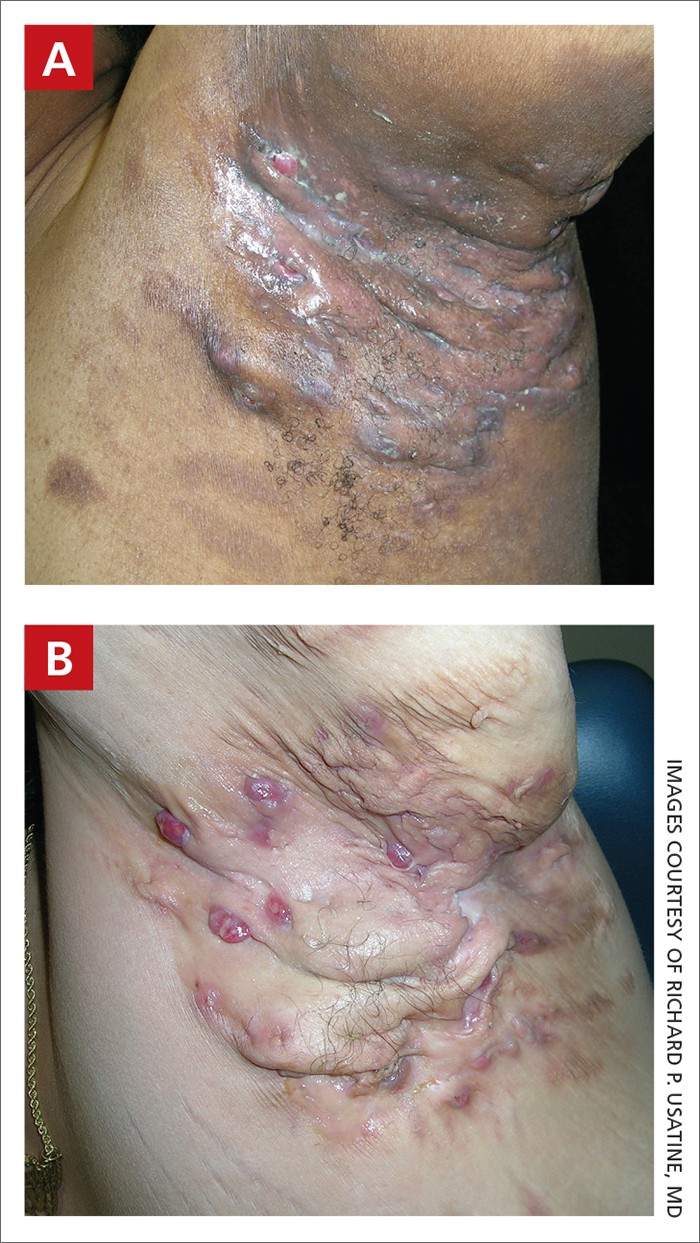

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

THE PRESENTATION

Severe long-standing hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of a 35-year-old Black man (A) and a 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone (B).

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in HS patients:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts (tunnels) and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts (tunnels), abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

Hidradenitis suppurativa is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to lack of HS knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

- Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa [published online November 11, 2020]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

- Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

- Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73 (5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm [published online September 17, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management [published online March 11, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

- Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2021.01.059

THE PRESENTATION

Severe long-standing hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of a 35-year-old Black man (A) and a 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone (B).

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in HS patients:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts (tunnels) and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts (tunnels), abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

Hidradenitis suppurativa is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to lack of HS knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

THE PRESENTATION

Severe long-standing hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of a 35-year-old Black man (A) and a 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone (B).

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in HS patients:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts (tunnels) and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts (tunnels), abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

Hidradenitis suppurativa is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to lack of HS knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

- Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa [published online November 11, 2020]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

- Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

- Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73 (5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm [published online September 17, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management [published online March 11, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

- Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2021.01.059

- Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa [published online November 11, 2020]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

- Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

- Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73 (5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm [published online September 17, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management [published online March 11, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

- Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2021.01.059

Basal cell carcinoma

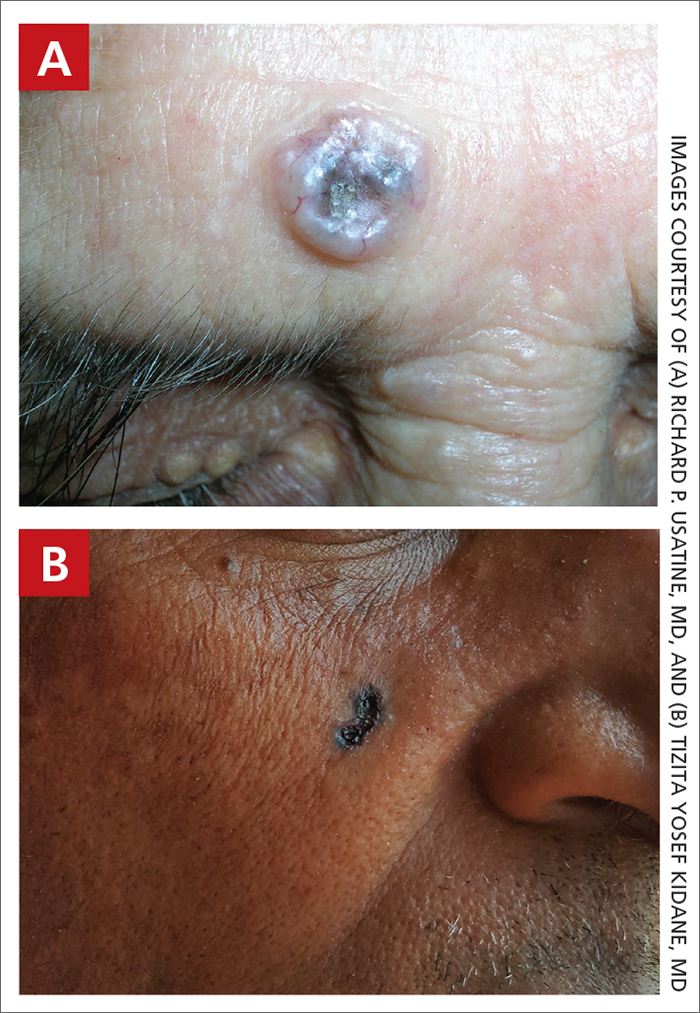

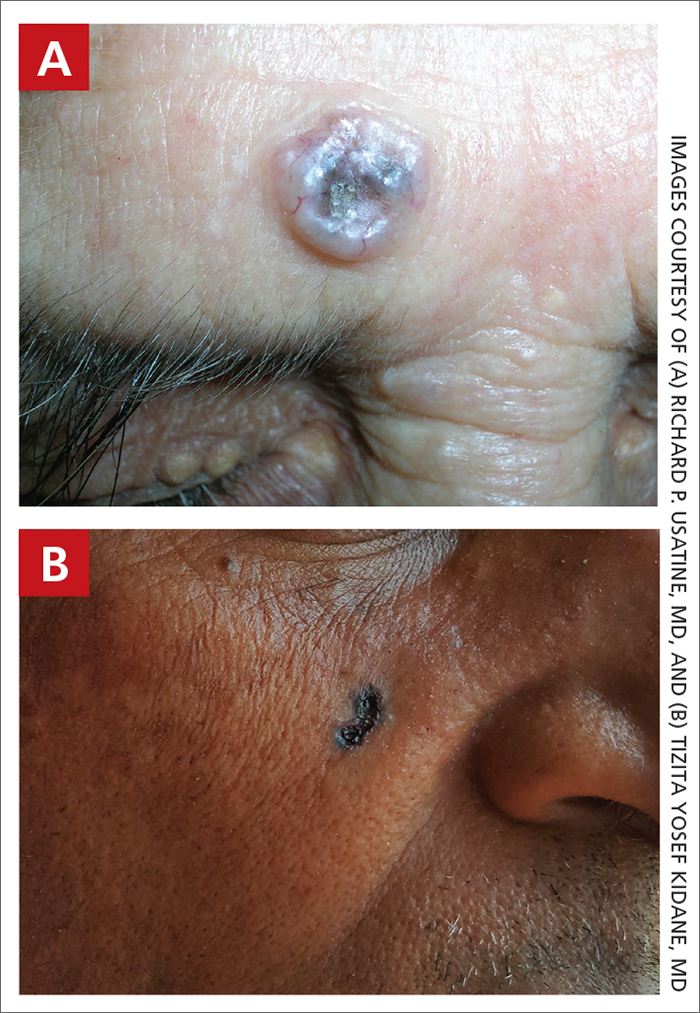

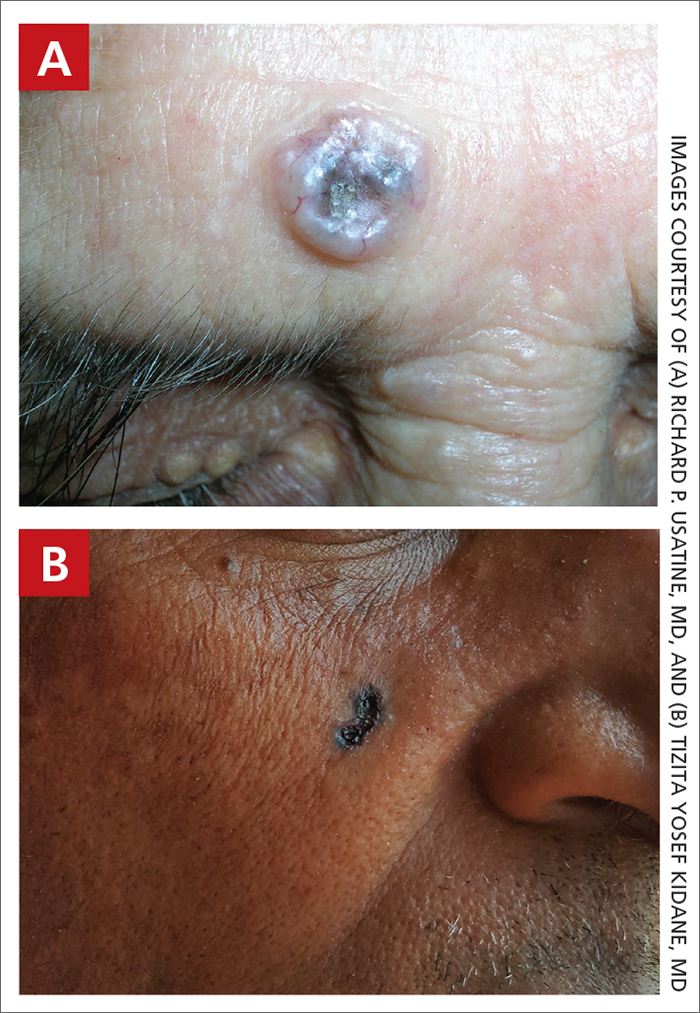

THE COMPARISON

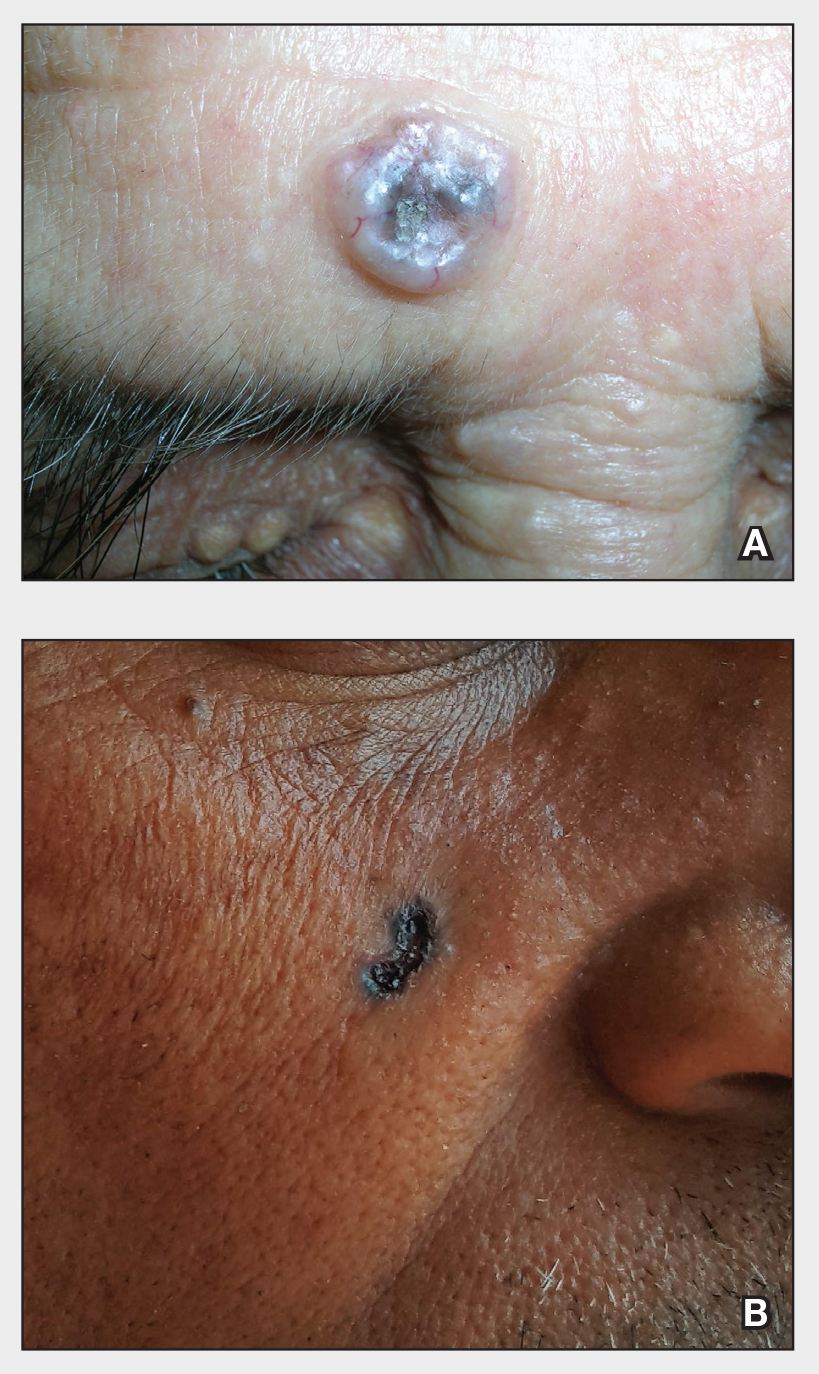

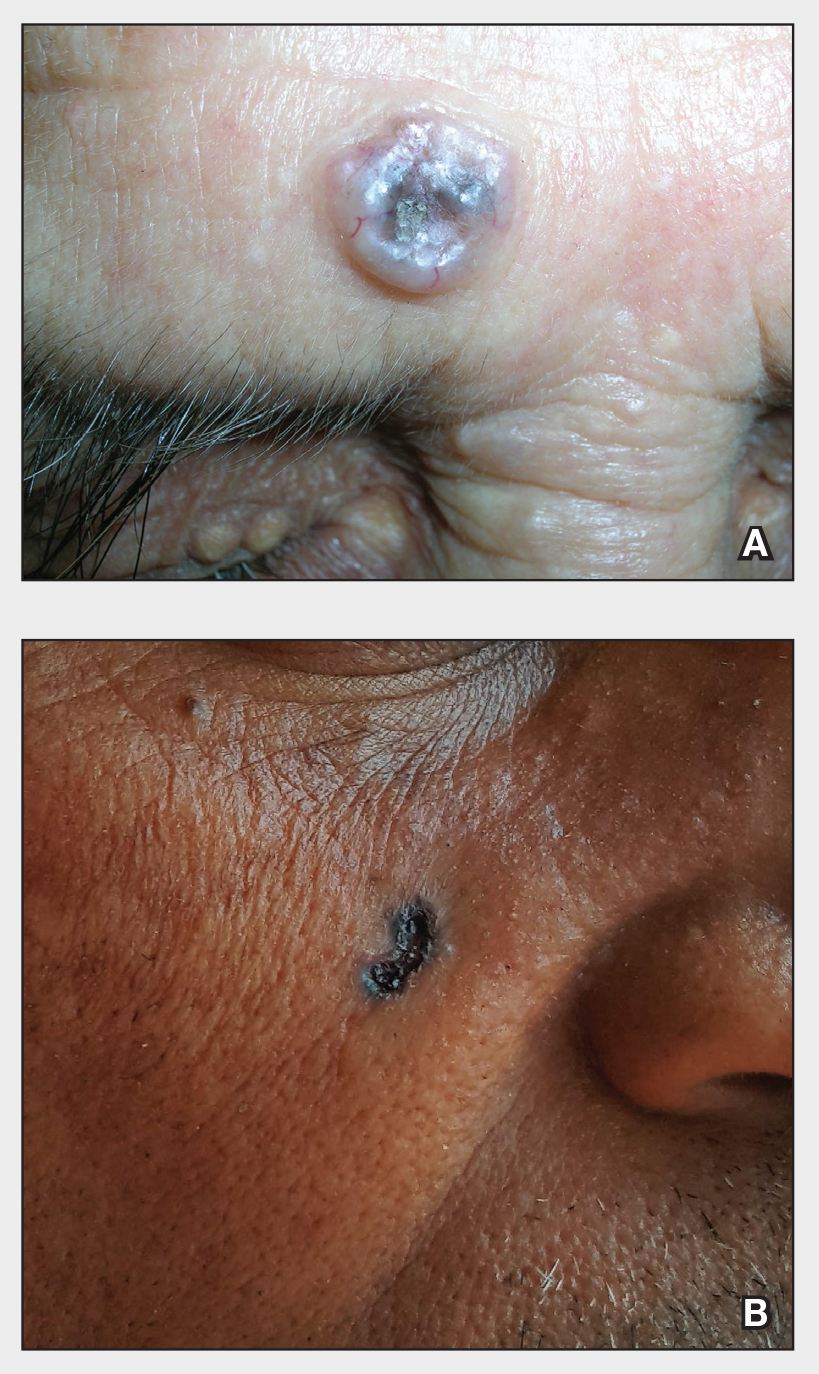

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

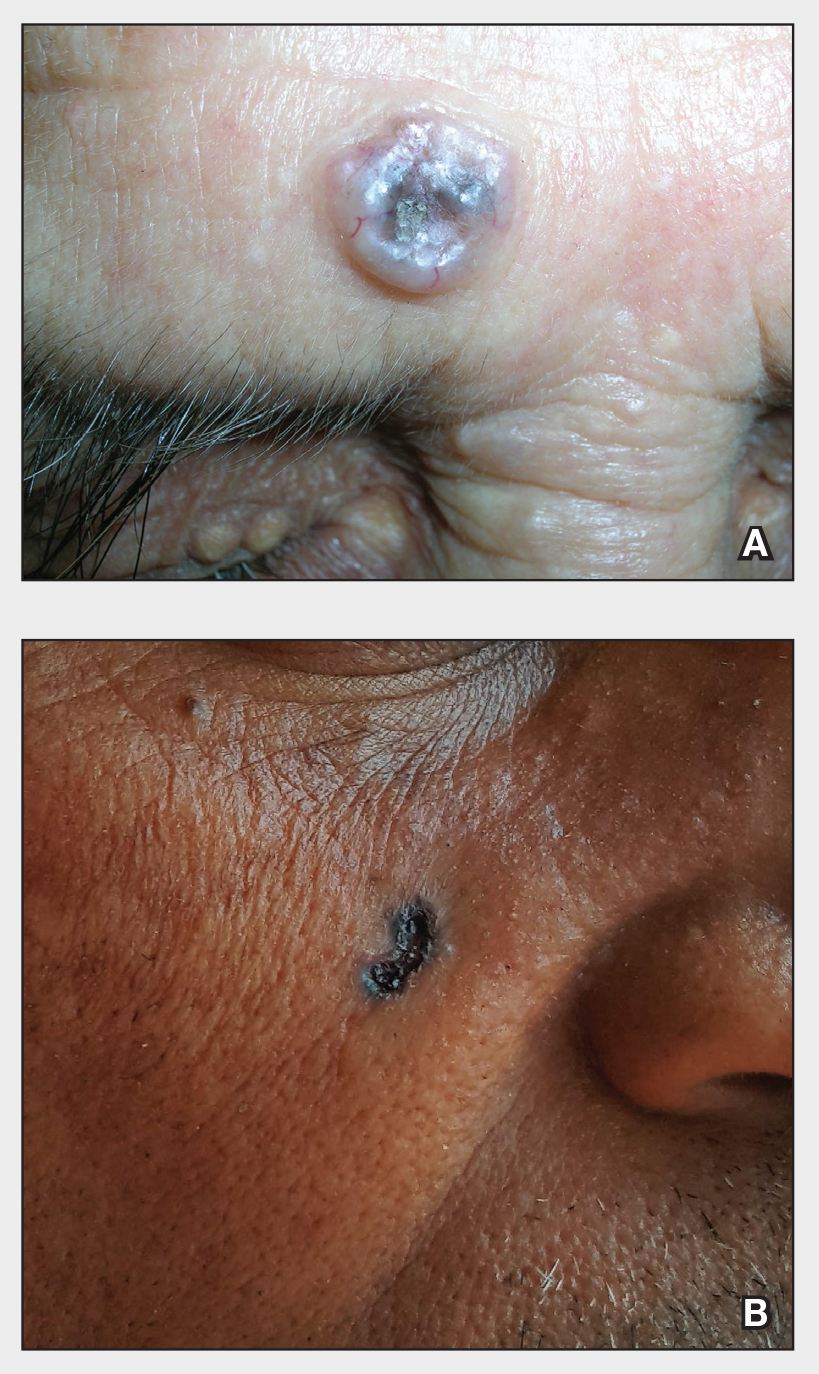

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

Basal Cell Carcinoma

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals.5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (Figure, A) as in non-Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations, so while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (R.P.U.), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (Figure, A). There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes. 1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and SCC found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non- Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (Figure, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer regardless of skin color.

- Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

- Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

- Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

- Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

- Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(81)70067-7

- Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90007-9

- Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study [published online July 9, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals.5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (Figure, A) as in non-Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations, so while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting