User login

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Richard P. Usatine, MD

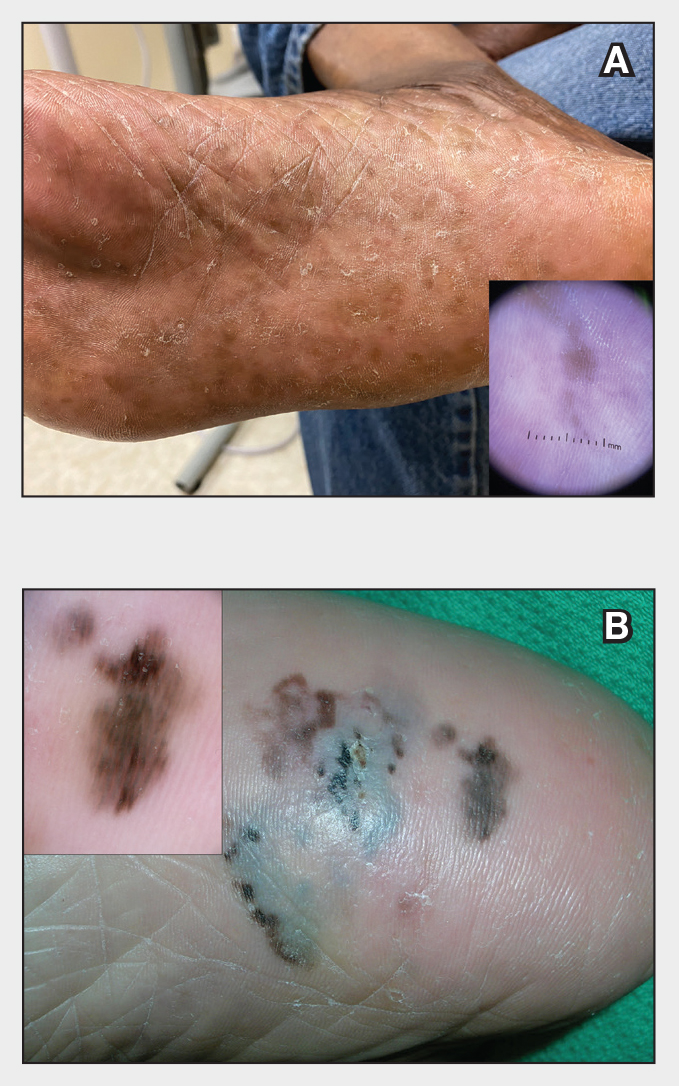

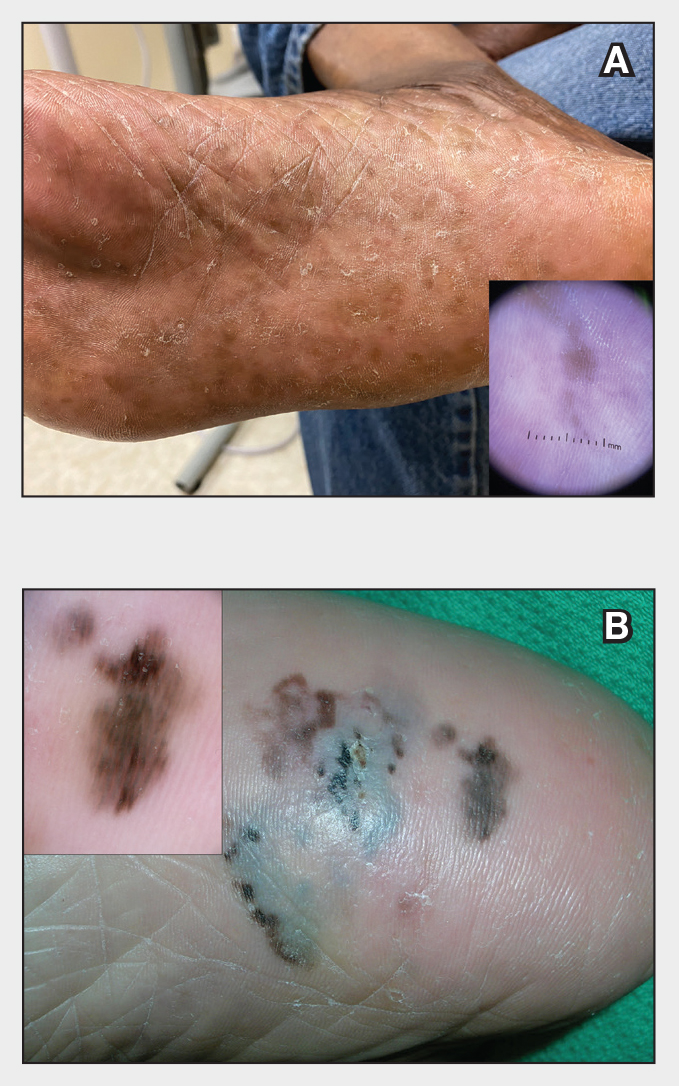

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

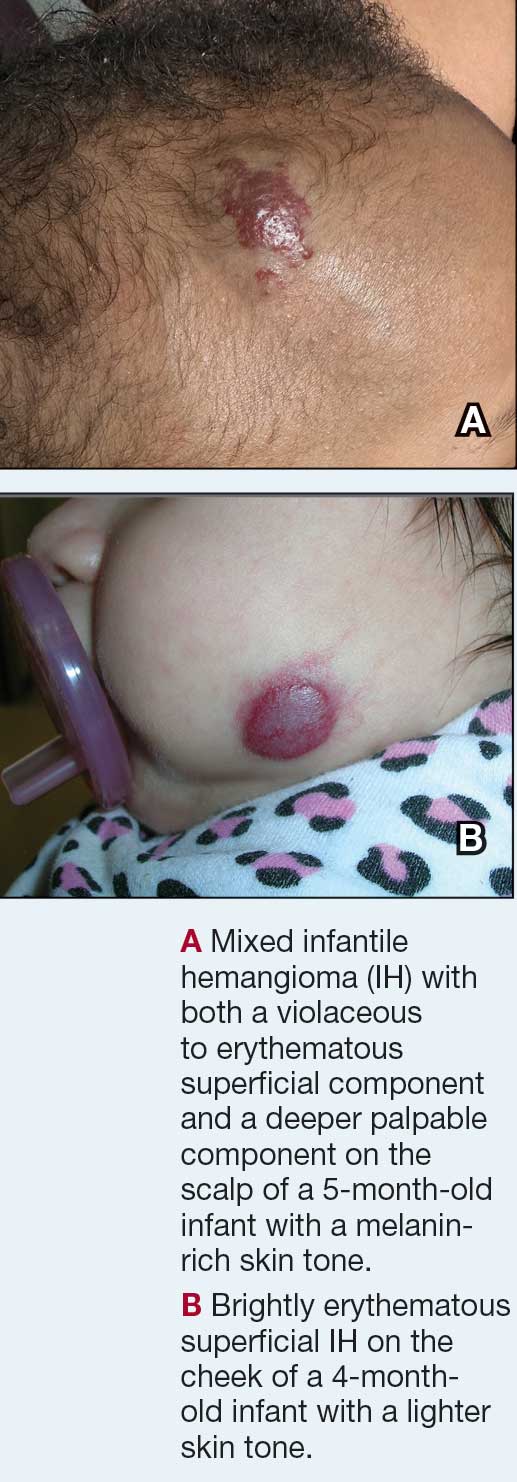

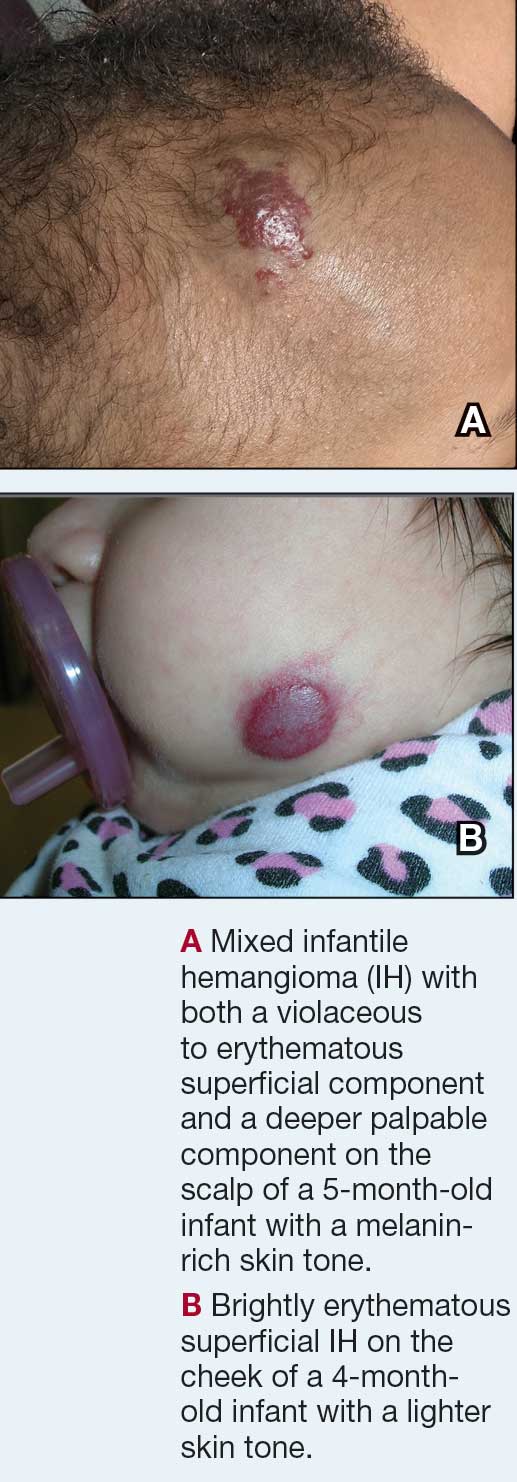

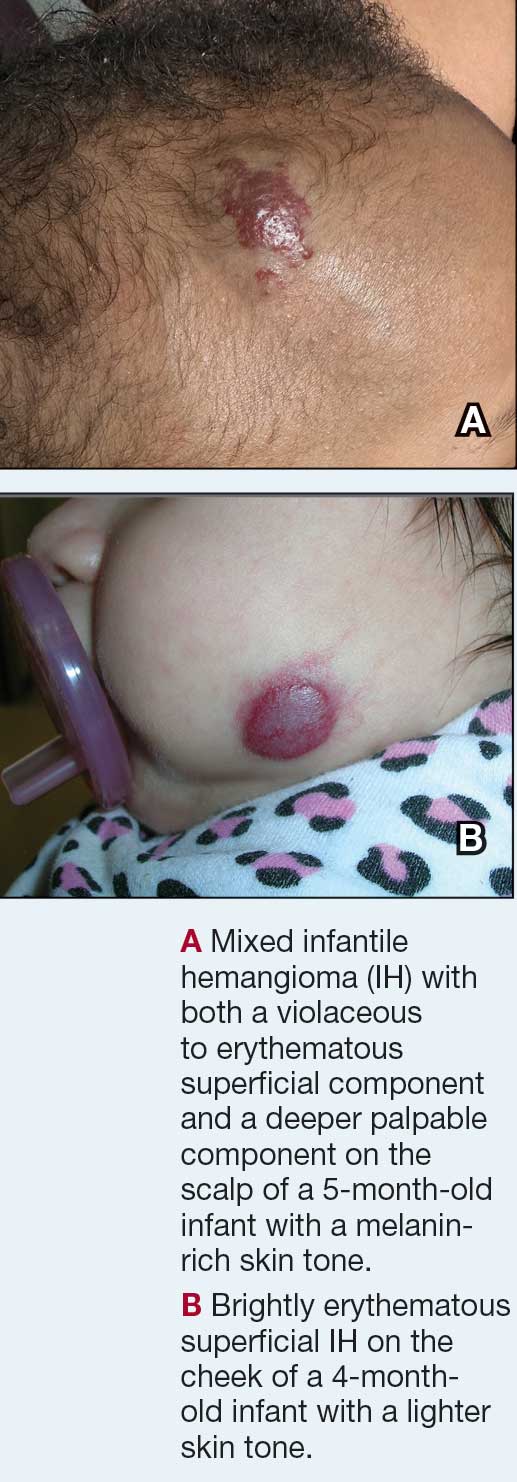

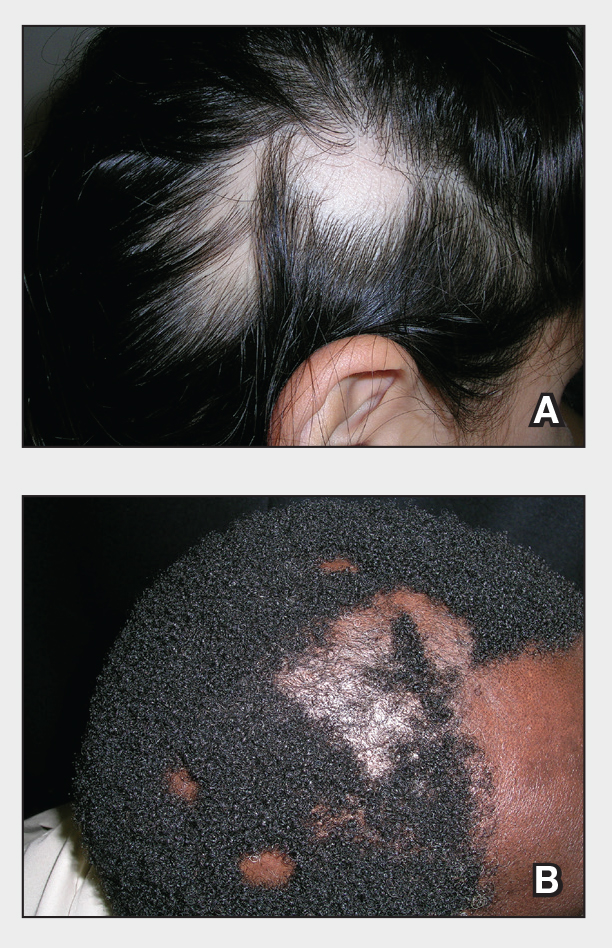

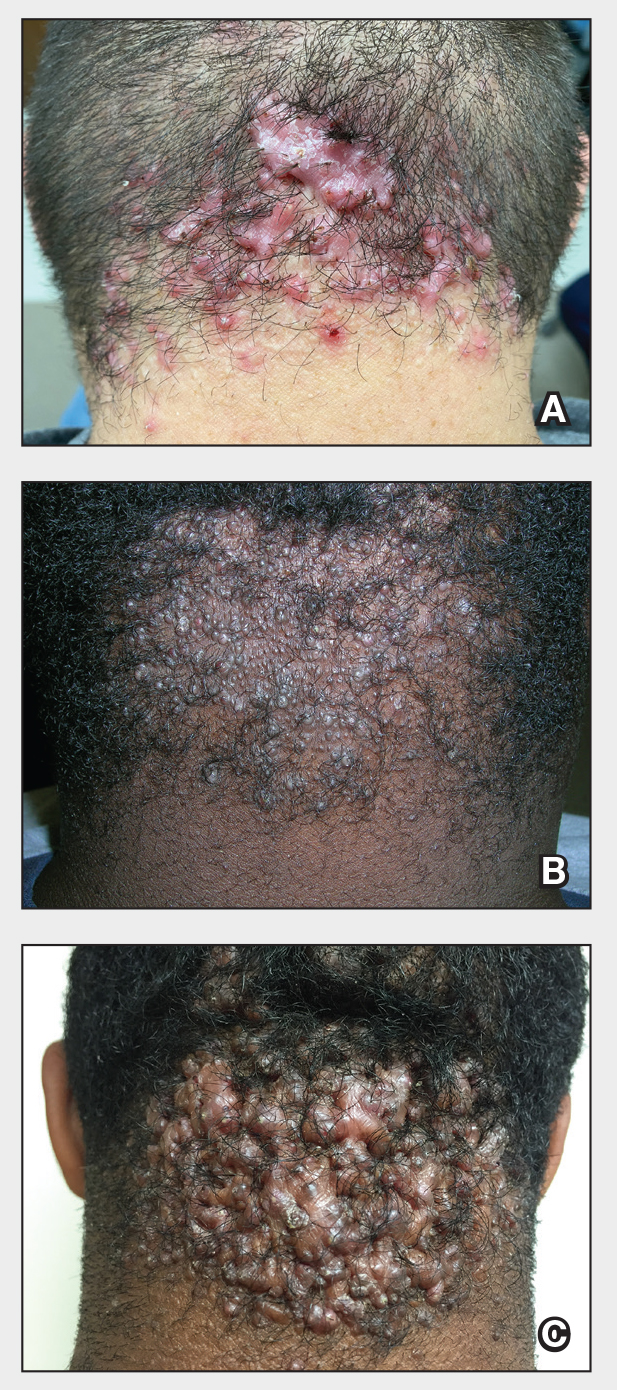

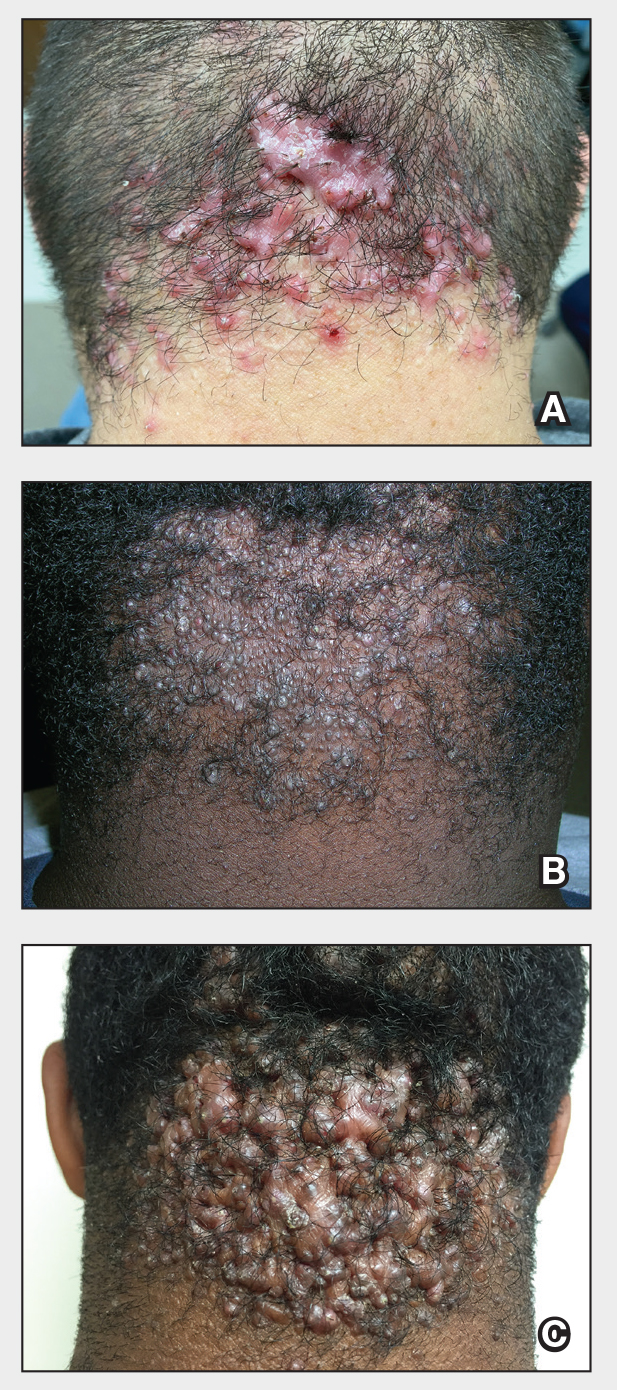

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Richard P. Usatine, MD

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

Richard P. Usatine, MD

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

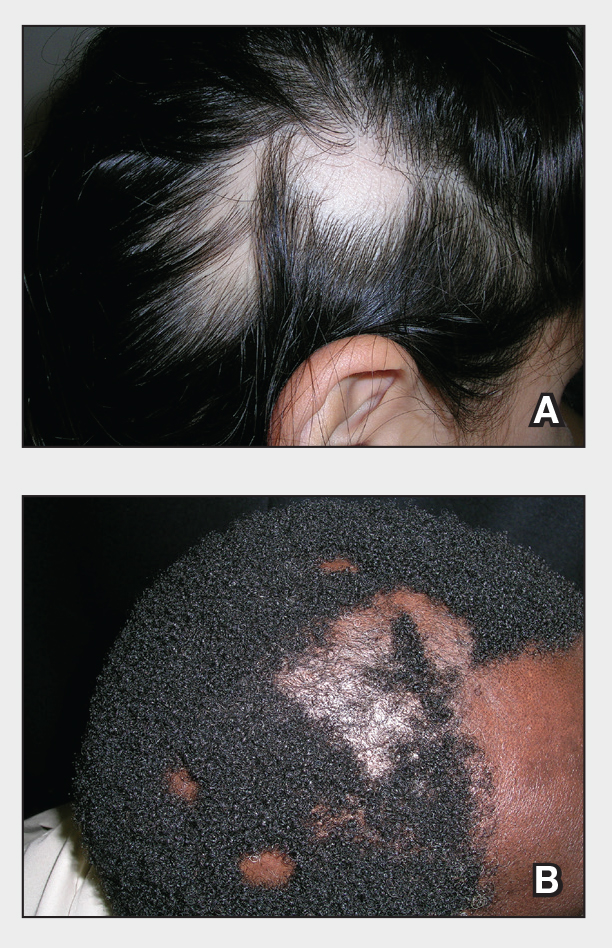

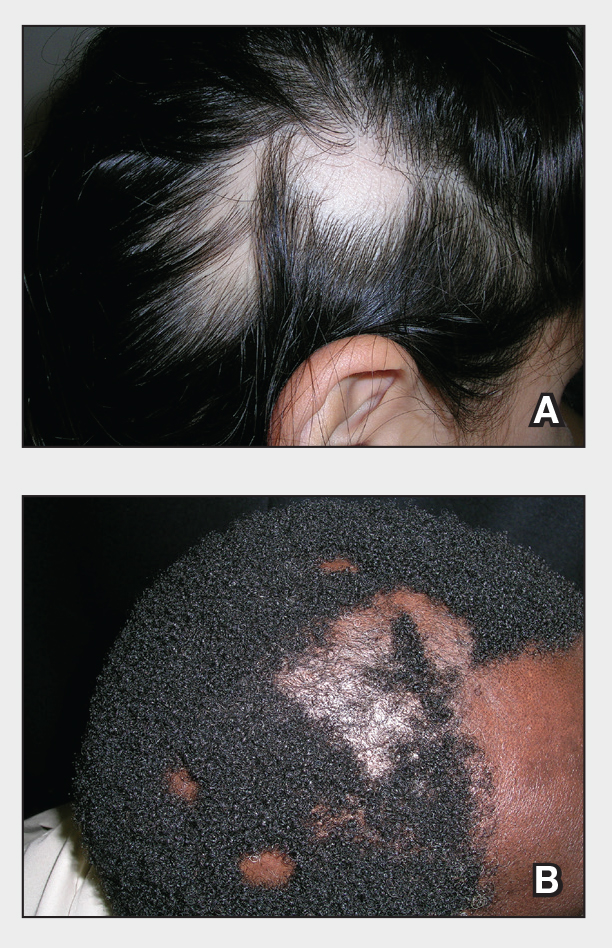

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

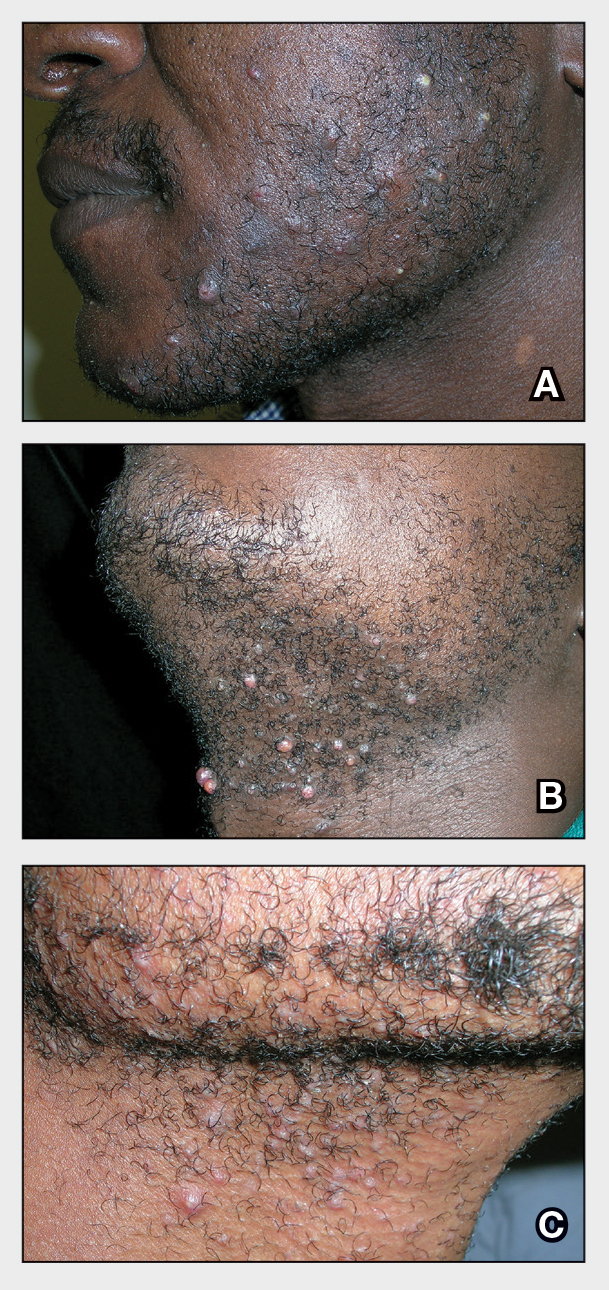

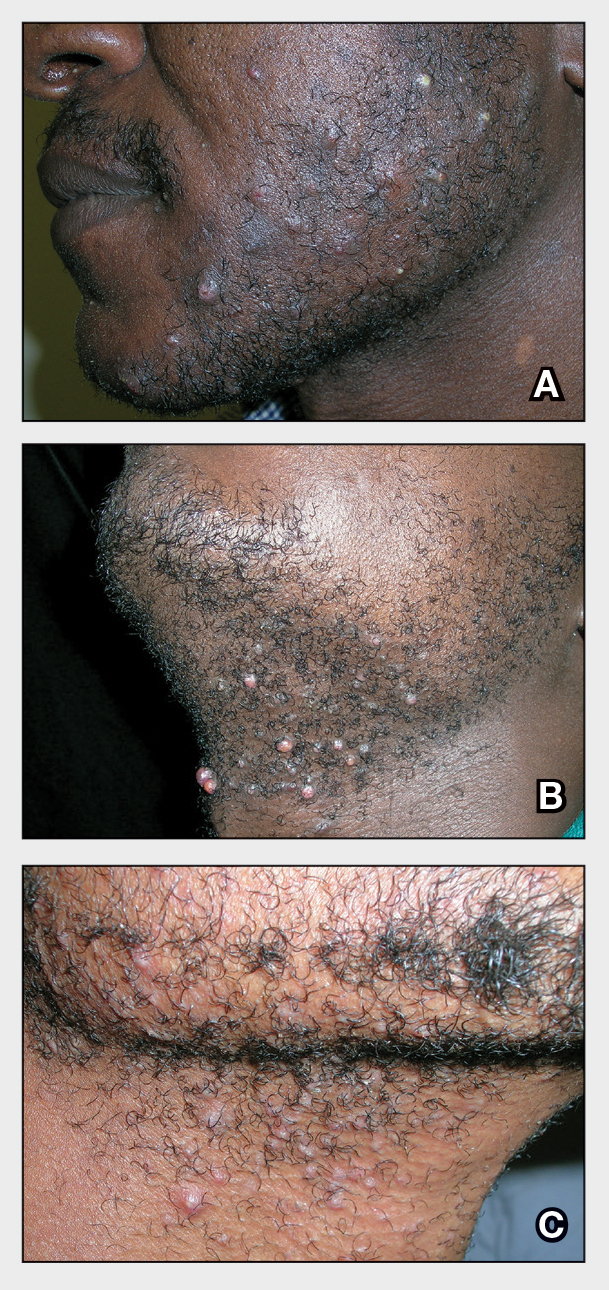

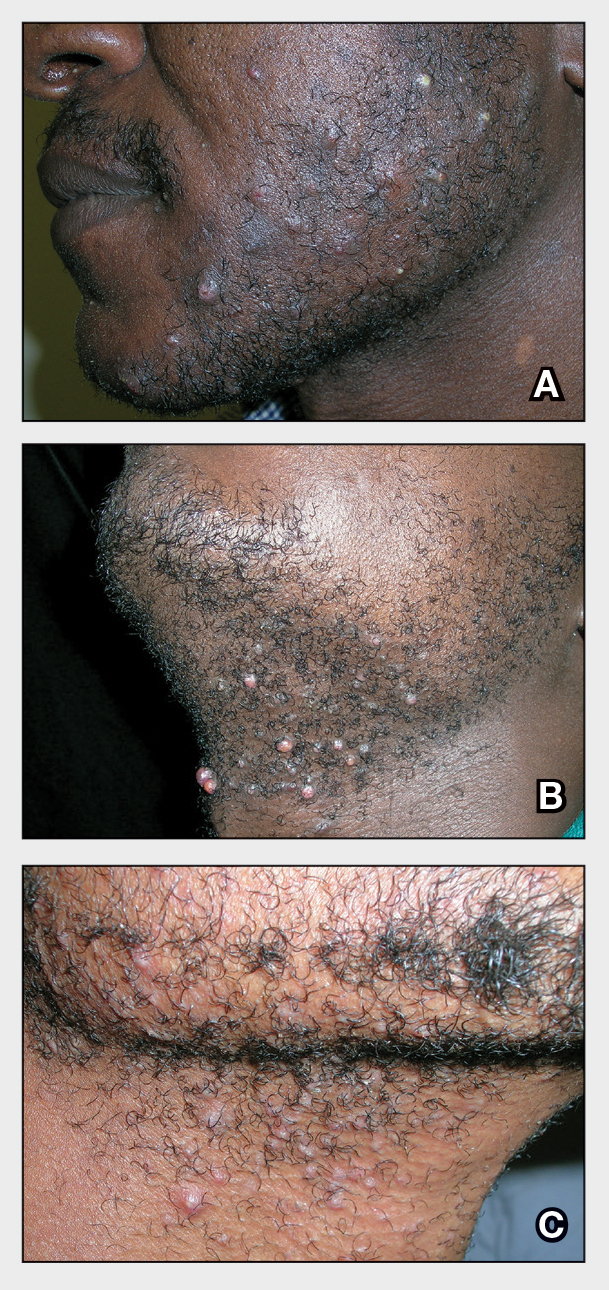

THE COMPARISON:

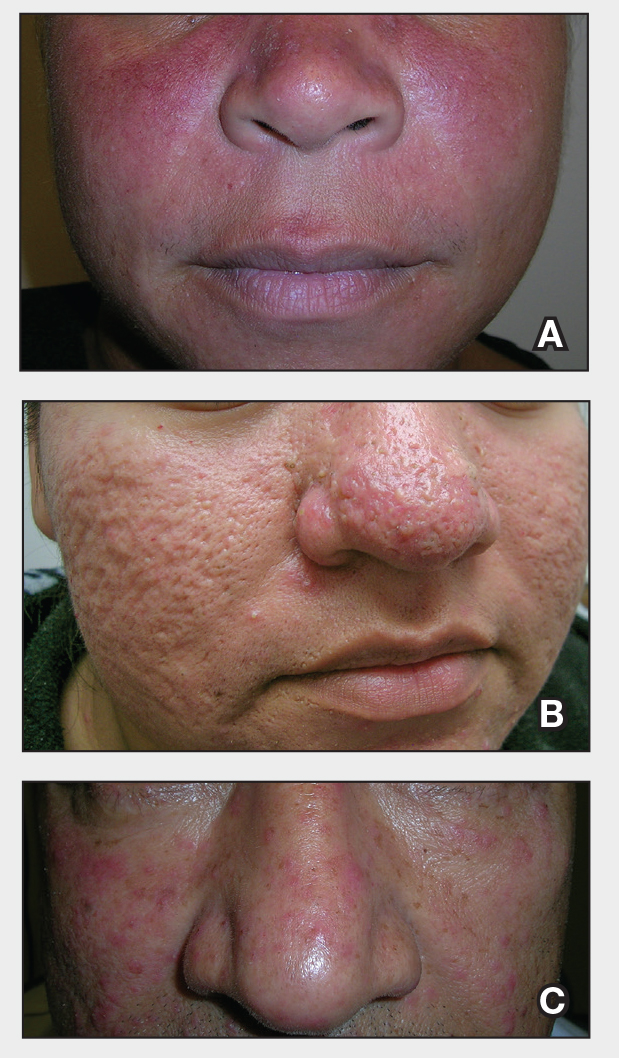

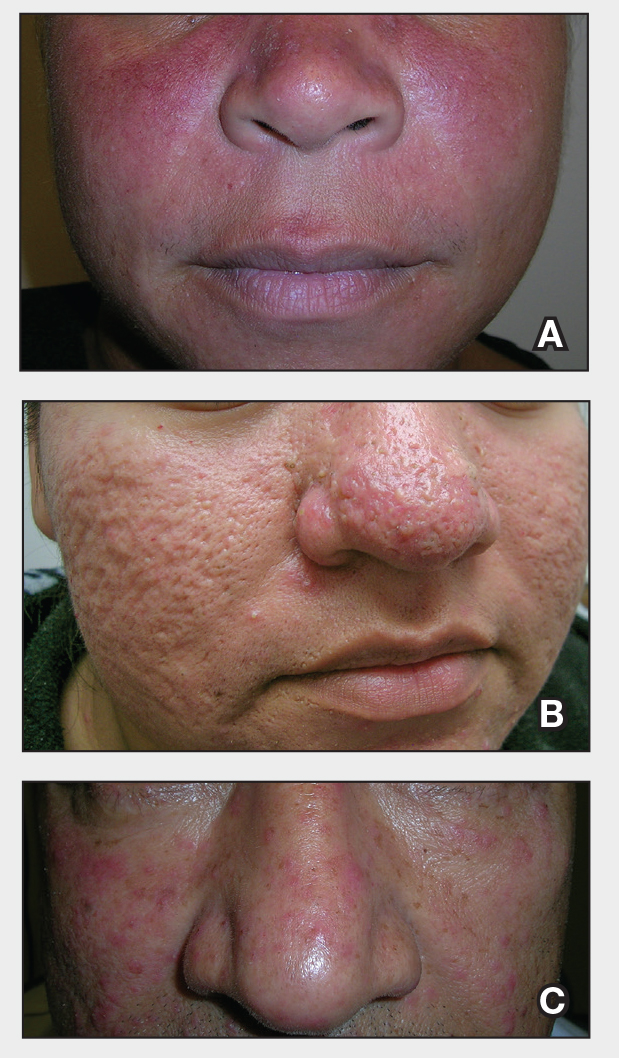

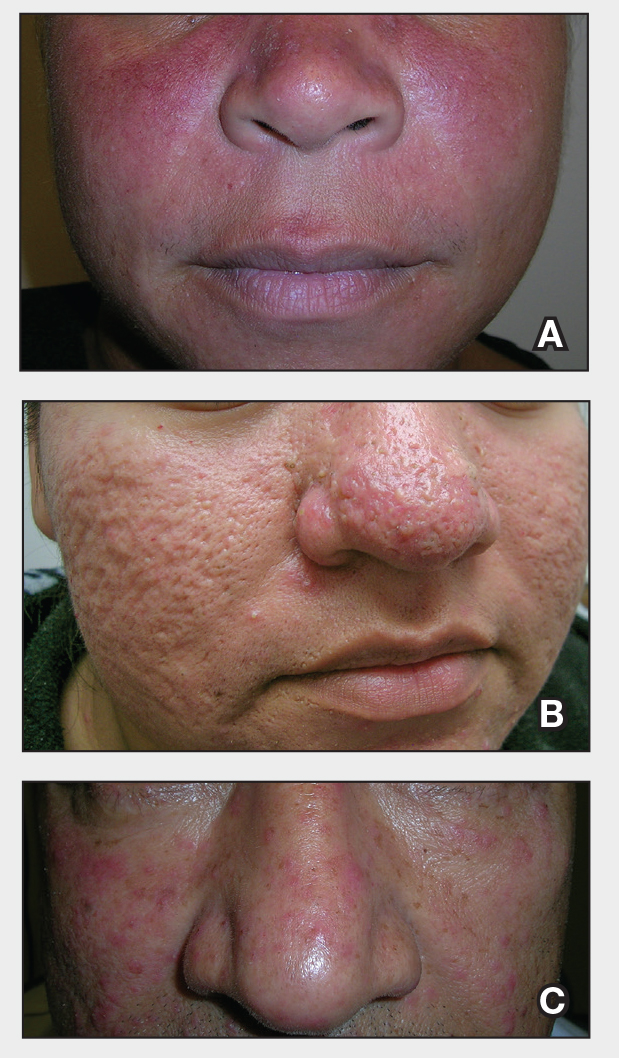

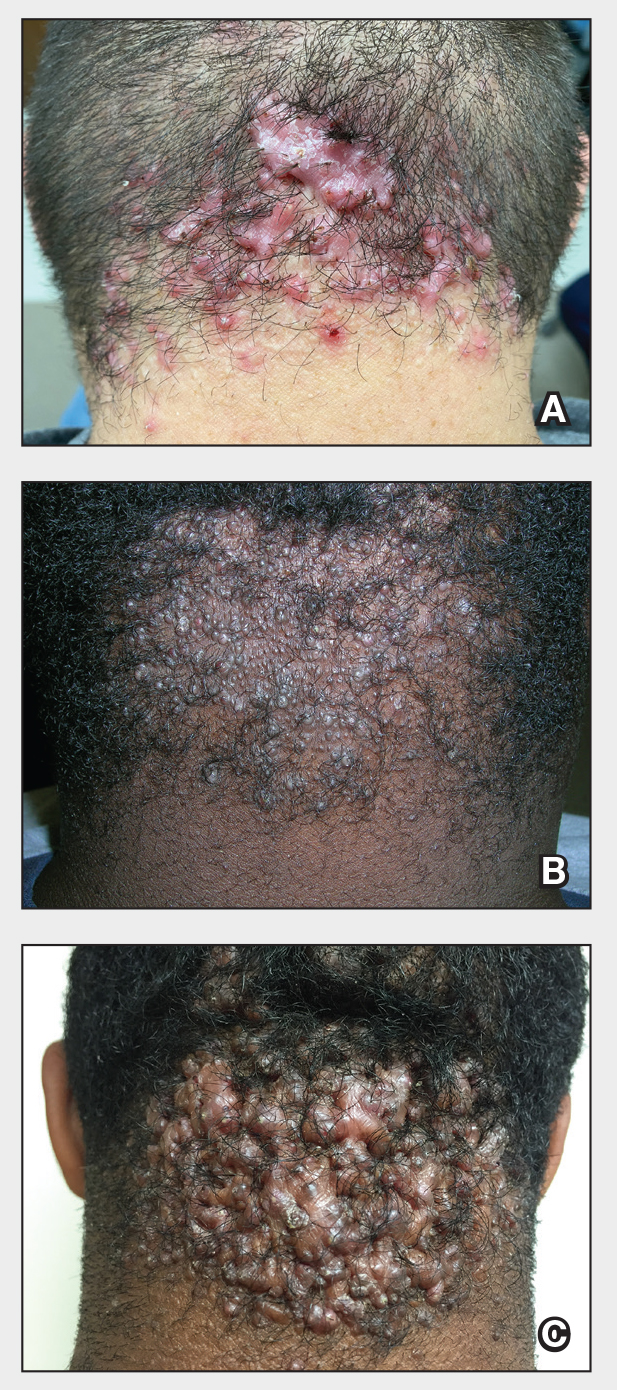

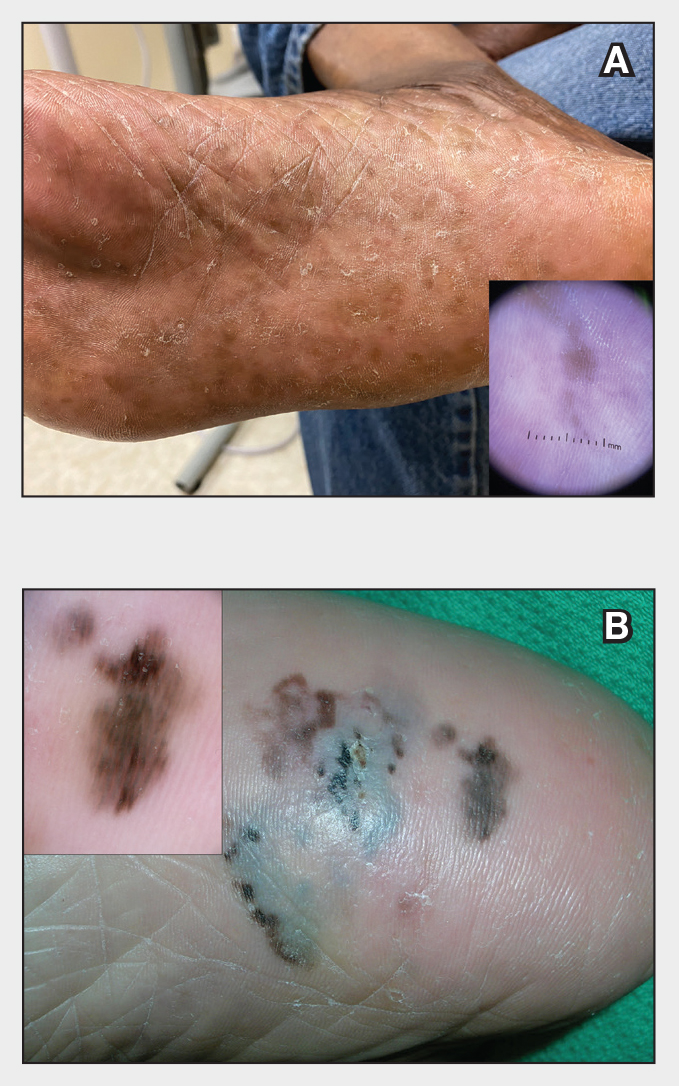

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.