User login

Promoting Gender Equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

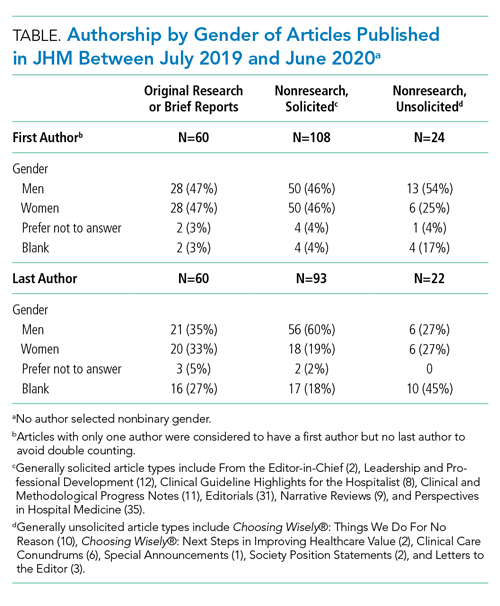

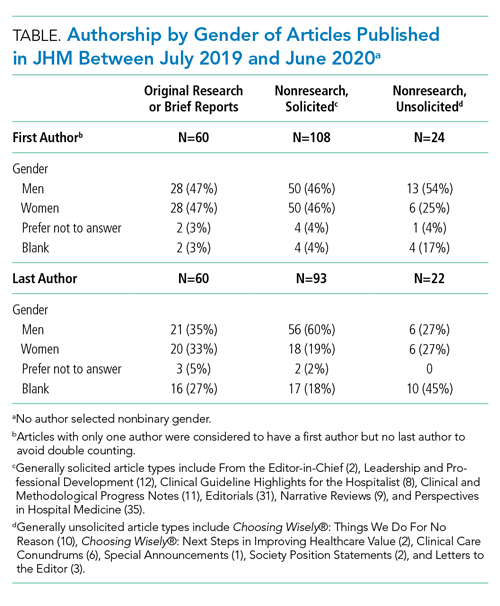

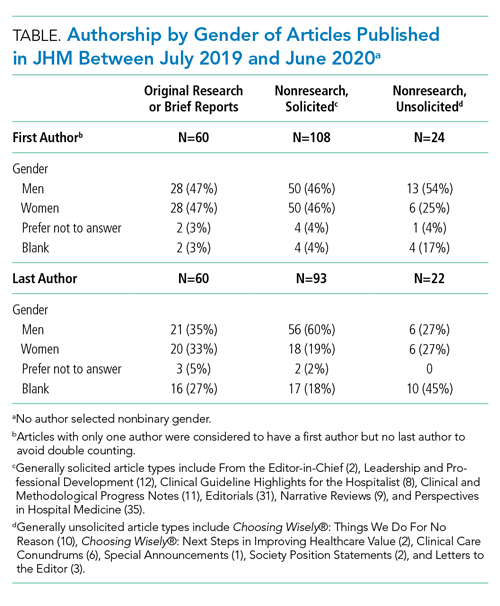

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Rapid Publication, Knowledge Sharing, and Our Responsibility During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Next Steps for Next Steps: The Intersection of Health Policy with Clinical Decision-Making

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to [email protected].

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to [email protected].

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to [email protected].

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine