User login

How Organizations Can Build a Successful and Sustainable Social Media Presence

Horwitz and Detsky1 provide readers with a personal, experientially based primer on how healthcare professionals can more effectively engage on Twitter. As experienced physicians, researchers, and active social media users, the authors outline pragmatic and specific recommendations on how to engage misinformation and add value to social media discourse. We applaud the authors for offering best-practice approaches that are valuable to newcomers as well as seasoned social media users. In highlighting that social media is merely a modern tool for engagement and discussion, the authors underscore the time-held idea that only when a tool is used effectively will it yield the desired outcome. As a medical journal that regularly uses social media as a tool for outreach and dissemination, we could not agree more with the authors’ assertion.

Since 2015, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has used social media to engage its readership and extend the impact of the work published in its pages. Like Horwitz and Detsky, JHM has developed insights and experience in how medical journals, organizations, institutions, and other academic programs can use social media effectively. Because of our experience in this area, we are often asked how to build a successful and sustainable social media presence. Here, we share five primary lessons on how to use social media as a tool to disseminate, connect, and engage.

ESTABLISH YOUR GOALS

As the flagship journal for the field of hospital medicine, we seek to disseminate the ideas and research that will inform health policy, optimize healthcare delivery, and improve patient outcomes while also building and sustaining an online community for professional engagement and growth. Our social media goals provide direction on how to interact, allow us to focus attention on what is important, and motivate our growth in this area. Simply put, we believe that using social media without defined goals would be like sailing a ship without a rudder.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

As your organization establishes its goals, it is important to consider with whom you want to connect. Knowing your audience will allow you to better tailor the content you deliver through social media. For instance, we understand that as a journal focused on hospital medicine, our audience consists of busy clinicians, researchers, and medical educators who are trying to efficiently gather the most up-to-date information in our field. Recognizing this, we produce (and make available for download) Visual Abstracts and publish them on Twitter to help our followers assimilate information from new studies quickly and easily.2 Moreover, we recognize that our followers are interested in how to use social media in their professional lives and have published several articles in this topic area.3-5

BUILD YOUR TEAM

We have found that having multiple individuals on our social media team has led to greater creativity and thoughtfulness on how we engage our readership. Our teams span generations, clinical experience, institutions, and cultural backgrounds. This intentional approach has allowed for diversity in thoughts and opinions and has helped shape the JHM social media message. Additionally, we have not only formalized editorial roles through the creation of Digital Media Editor positions, but we have also created the JHM Digital Media Fellowship, a training program and development pipeline for those interested in cultivating organization-based social media experiences and skill sets.6

ENGAGE CONSISTENTLY

Many organizations believe that successful social media outreach means creating an account and posting content when convenient. Experience has taught us that daily postings and regular engagement will build your brand as a regular and reliable source of information for your followers. Additionally, while many academic journals and organizations only occasionally post material and rarely interact with their followers, we have found that engaging and facilitating conversations through our monthly Twitter discussion (#JHMChat) has established a community, created opportunities for professional networking, and further disseminated the work published in JHM.7 As an academic journal or organization entering this field, recognize the product for which people follow you and deliver that product on a consistent basis.

OWN YOUR MISTAKES

It will only be a matter of time before your organization makes a misstep on social media. Instead of hiding, we recommend stepping into that tension and owning the mistake. For example, we recently published an article that contained a culturally offensive term. As a journal, we reflected on our error and took concrete steps to correct it. Further, we shared our thoughts with our followers to ensure transparency.8 Moving forward, we have inserted specific stopgaps in our editorial review process to avoid such missteps in the future.

Although every organization will have different goals and reasons for engaging on social media, we believe these central tenets will help optimize the use of this platform. Although we have established specific objectives for our engagement on social media, we believe Horwitz and Detsky1 put it best when they note that, at the end of the day, our ultimate goal is in “…promoting knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives."

1. Horwitz LI, Detsky AS. Tweeting into the void: effective use of social media for healthcare professionals. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):581-582. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3684

2. 2021 Visual Abstracts. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/2021-visual-abstracts

3. Kumar A, Chen N, Singh A. #ConsentObtained - patient privacy in the age of social media. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):702-704. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3416

4. Minter DJ, Patel A, Ganeshan S, Nematollahi S. Medical communities go virtual. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):378-380. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3532

5. Marcelin JR, Cawcutt KA, Shapiro M, Varghese T, O’Glasser A. Moment vs movement: mission-based tweeting for physician advocacy. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3636

6. Editorial Fellowships (Digital Media and Editorial). Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/content/editorial-fellowships-digital-media-and-editorial

7. Wray CM, Auerbach AD, Arora VM. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):764-769. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2987

8. Shah SS, Manning KD, Wray CM, Castellanos A, Jerardi KE. Microaggressions, accountability, and our commitment to doing better [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):325. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3646

Horwitz and Detsky1 provide readers with a personal, experientially based primer on how healthcare professionals can more effectively engage on Twitter. As experienced physicians, researchers, and active social media users, the authors outline pragmatic and specific recommendations on how to engage misinformation and add value to social media discourse. We applaud the authors for offering best-practice approaches that are valuable to newcomers as well as seasoned social media users. In highlighting that social media is merely a modern tool for engagement and discussion, the authors underscore the time-held idea that only when a tool is used effectively will it yield the desired outcome. As a medical journal that regularly uses social media as a tool for outreach and dissemination, we could not agree more with the authors’ assertion.

Since 2015, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has used social media to engage its readership and extend the impact of the work published in its pages. Like Horwitz and Detsky, JHM has developed insights and experience in how medical journals, organizations, institutions, and other academic programs can use social media effectively. Because of our experience in this area, we are often asked how to build a successful and sustainable social media presence. Here, we share five primary lessons on how to use social media as a tool to disseminate, connect, and engage.

ESTABLISH YOUR GOALS

As the flagship journal for the field of hospital medicine, we seek to disseminate the ideas and research that will inform health policy, optimize healthcare delivery, and improve patient outcomes while also building and sustaining an online community for professional engagement and growth. Our social media goals provide direction on how to interact, allow us to focus attention on what is important, and motivate our growth in this area. Simply put, we believe that using social media without defined goals would be like sailing a ship without a rudder.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

As your organization establishes its goals, it is important to consider with whom you want to connect. Knowing your audience will allow you to better tailor the content you deliver through social media. For instance, we understand that as a journal focused on hospital medicine, our audience consists of busy clinicians, researchers, and medical educators who are trying to efficiently gather the most up-to-date information in our field. Recognizing this, we produce (and make available for download) Visual Abstracts and publish them on Twitter to help our followers assimilate information from new studies quickly and easily.2 Moreover, we recognize that our followers are interested in how to use social media in their professional lives and have published several articles in this topic area.3-5

BUILD YOUR TEAM

We have found that having multiple individuals on our social media team has led to greater creativity and thoughtfulness on how we engage our readership. Our teams span generations, clinical experience, institutions, and cultural backgrounds. This intentional approach has allowed for diversity in thoughts and opinions and has helped shape the JHM social media message. Additionally, we have not only formalized editorial roles through the creation of Digital Media Editor positions, but we have also created the JHM Digital Media Fellowship, a training program and development pipeline for those interested in cultivating organization-based social media experiences and skill sets.6

ENGAGE CONSISTENTLY

Many organizations believe that successful social media outreach means creating an account and posting content when convenient. Experience has taught us that daily postings and regular engagement will build your brand as a regular and reliable source of information for your followers. Additionally, while many academic journals and organizations only occasionally post material and rarely interact with their followers, we have found that engaging and facilitating conversations through our monthly Twitter discussion (#JHMChat) has established a community, created opportunities for professional networking, and further disseminated the work published in JHM.7 As an academic journal or organization entering this field, recognize the product for which people follow you and deliver that product on a consistent basis.

OWN YOUR MISTAKES

It will only be a matter of time before your organization makes a misstep on social media. Instead of hiding, we recommend stepping into that tension and owning the mistake. For example, we recently published an article that contained a culturally offensive term. As a journal, we reflected on our error and took concrete steps to correct it. Further, we shared our thoughts with our followers to ensure transparency.8 Moving forward, we have inserted specific stopgaps in our editorial review process to avoid such missteps in the future.

Although every organization will have different goals and reasons for engaging on social media, we believe these central tenets will help optimize the use of this platform. Although we have established specific objectives for our engagement on social media, we believe Horwitz and Detsky1 put it best when they note that, at the end of the day, our ultimate goal is in “…promoting knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives."

Horwitz and Detsky1 provide readers with a personal, experientially based primer on how healthcare professionals can more effectively engage on Twitter. As experienced physicians, researchers, and active social media users, the authors outline pragmatic and specific recommendations on how to engage misinformation and add value to social media discourse. We applaud the authors for offering best-practice approaches that are valuable to newcomers as well as seasoned social media users. In highlighting that social media is merely a modern tool for engagement and discussion, the authors underscore the time-held idea that only when a tool is used effectively will it yield the desired outcome. As a medical journal that regularly uses social media as a tool for outreach and dissemination, we could not agree more with the authors’ assertion.

Since 2015, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has used social media to engage its readership and extend the impact of the work published in its pages. Like Horwitz and Detsky, JHM has developed insights and experience in how medical journals, organizations, institutions, and other academic programs can use social media effectively. Because of our experience in this area, we are often asked how to build a successful and sustainable social media presence. Here, we share five primary lessons on how to use social media as a tool to disseminate, connect, and engage.

ESTABLISH YOUR GOALS

As the flagship journal for the field of hospital medicine, we seek to disseminate the ideas and research that will inform health policy, optimize healthcare delivery, and improve patient outcomes while also building and sustaining an online community for professional engagement and growth. Our social media goals provide direction on how to interact, allow us to focus attention on what is important, and motivate our growth in this area. Simply put, we believe that using social media without defined goals would be like sailing a ship without a rudder.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

As your organization establishes its goals, it is important to consider with whom you want to connect. Knowing your audience will allow you to better tailor the content you deliver through social media. For instance, we understand that as a journal focused on hospital medicine, our audience consists of busy clinicians, researchers, and medical educators who are trying to efficiently gather the most up-to-date information in our field. Recognizing this, we produce (and make available for download) Visual Abstracts and publish them on Twitter to help our followers assimilate information from new studies quickly and easily.2 Moreover, we recognize that our followers are interested in how to use social media in their professional lives and have published several articles in this topic area.3-5

BUILD YOUR TEAM

We have found that having multiple individuals on our social media team has led to greater creativity and thoughtfulness on how we engage our readership. Our teams span generations, clinical experience, institutions, and cultural backgrounds. This intentional approach has allowed for diversity in thoughts and opinions and has helped shape the JHM social media message. Additionally, we have not only formalized editorial roles through the creation of Digital Media Editor positions, but we have also created the JHM Digital Media Fellowship, a training program and development pipeline for those interested in cultivating organization-based social media experiences and skill sets.6

ENGAGE CONSISTENTLY

Many organizations believe that successful social media outreach means creating an account and posting content when convenient. Experience has taught us that daily postings and regular engagement will build your brand as a regular and reliable source of information for your followers. Additionally, while many academic journals and organizations only occasionally post material and rarely interact with their followers, we have found that engaging and facilitating conversations through our monthly Twitter discussion (#JHMChat) has established a community, created opportunities for professional networking, and further disseminated the work published in JHM.7 As an academic journal or organization entering this field, recognize the product for which people follow you and deliver that product on a consistent basis.

OWN YOUR MISTAKES

It will only be a matter of time before your organization makes a misstep on social media. Instead of hiding, we recommend stepping into that tension and owning the mistake. For example, we recently published an article that contained a culturally offensive term. As a journal, we reflected on our error and took concrete steps to correct it. Further, we shared our thoughts with our followers to ensure transparency.8 Moving forward, we have inserted specific stopgaps in our editorial review process to avoid such missteps in the future.

Although every organization will have different goals and reasons for engaging on social media, we believe these central tenets will help optimize the use of this platform. Although we have established specific objectives for our engagement on social media, we believe Horwitz and Detsky1 put it best when they note that, at the end of the day, our ultimate goal is in “…promoting knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives."

1. Horwitz LI, Detsky AS. Tweeting into the void: effective use of social media for healthcare professionals. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):581-582. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3684

2. 2021 Visual Abstracts. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/2021-visual-abstracts

3. Kumar A, Chen N, Singh A. #ConsentObtained - patient privacy in the age of social media. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):702-704. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3416

4. Minter DJ, Patel A, Ganeshan S, Nematollahi S. Medical communities go virtual. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):378-380. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3532

5. Marcelin JR, Cawcutt KA, Shapiro M, Varghese T, O’Glasser A. Moment vs movement: mission-based tweeting for physician advocacy. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3636

6. Editorial Fellowships (Digital Media and Editorial). Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/content/editorial-fellowships-digital-media-and-editorial

7. Wray CM, Auerbach AD, Arora VM. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):764-769. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2987

8. Shah SS, Manning KD, Wray CM, Castellanos A, Jerardi KE. Microaggressions, accountability, and our commitment to doing better [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):325. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3646

1. Horwitz LI, Detsky AS. Tweeting into the void: effective use of social media for healthcare professionals. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):581-582. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3684

2. 2021 Visual Abstracts. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/2021-visual-abstracts

3. Kumar A, Chen N, Singh A. #ConsentObtained - patient privacy in the age of social media. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):702-704. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3416

4. Minter DJ, Patel A, Ganeshan S, Nematollahi S. Medical communities go virtual. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):378-380. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3532

5. Marcelin JR, Cawcutt KA, Shapiro M, Varghese T, O’Glasser A. Moment vs movement: mission-based tweeting for physician advocacy. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3636

6. Editorial Fellowships (Digital Media and Editorial). Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/content/editorial-fellowships-digital-media-and-editorial

7. Wray CM, Auerbach AD, Arora VM. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):764-769. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2987

8. Shah SS, Manning KD, Wray CM, Castellanos A, Jerardi KE. Microaggressions, accountability, and our commitment to doing better [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):325. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3646

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Trust in a Time of Uncertainty: A Call for Articles

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Microaggressions, Accountability, and Our Commitment to Doing Better

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Introducing Point-Counterpoint Perspectives in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

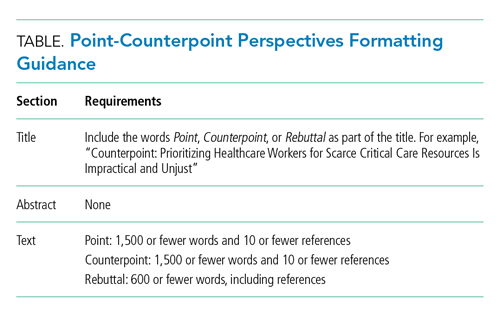

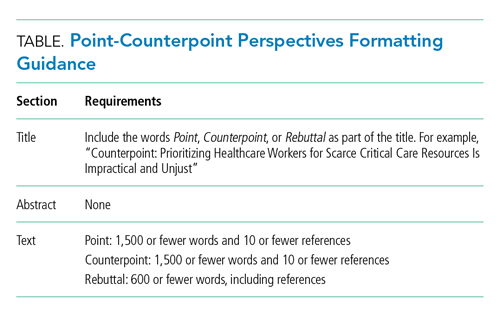

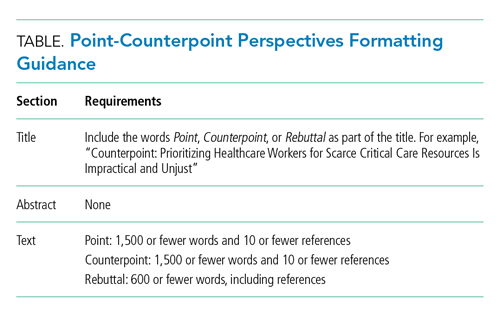

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

New Author Guidelines for Addressing Race and Racism in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Finding Your Bagel

Many of us are interested in developing or refining our skillsets. To do so, we need mentorship, which in the still-young field of hospital medicine can sometimes be challenging to obtain.

As a physician-investigator and editor, I commonly encounter young and even mid-career physicians wrestling with how to develop or refine their academic skills, and they’re usually pondering the challenges in finding someone in their own division or hospitalist group to help them. When this happens, I talk to them about bagels and cream cheese. I ask them two questions: “What’s your cream cheese?” and “Where’s your bagel?” Their natural reaction of puzzlement, perhaps mixed with hunger if they haven’t yet had breakfast, is similar to the one you’ve likely just experienced, so let me explain.

In medical school, I had a friend who absolutely loved cream cheese. If it had been socially acceptable, he would have simply walked around scooping cream cheese from a large tub. Had he done that, people would likely have given him funny looks and taken a few steps away. So, instead, my friend found an acceptable solution, which is that he would eat a lot of bagels. And those bagels would be piled high with cream cheese because what he wanted was the cream cheese and the bagel provided a reasonable means by which to get it.

So now I ask you: What’s your passion? What is the thing that you want to scoop from the tub (of learning and doing) every day for the rest of your life? That’s the cream cheese. Now, all you have to do is to find your bagel, the vehicle that allows you to get there.

Let’s see those principles in action. Say that you’re a hospitalist who wants to learn how to conduct randomized clinical trials, enhance medication reconciliation, or improve transitions of care. You can read about randomization schemes or improvement cycles but that’s clearly not enough. You need someone to help you frame the question, understand how to navigate the system, and avoid potential pitfalls. You need someone with relevant experience and expertise, someone with whom you can discuss nuances such as the trade-offs between different outcome measures or analytic approaches. You need your bagel.

There may not be anyone in your division with such expertise. You may need to branch out to find that bagel. You talk to a few people and they all point you to a cardiologist who runs clinical trials. What other field has such witty study acronyms as MRFIT or MIRACL or PROVE IT? If you’re interested in medication reconciliation, they may direct you to a pharmacist who studies medication errors. If you’re interested in improving care transitions, they may connect you with a critical care physician with expertise in interhospital transfers. You can meet with these folks to learn about their work. If their personality and mentorship style are a good fit, you can offer to assist in some aspect of their ongoing studies and, in return, ask for mentorship. You may have only a limited interest in the clinical content area, but if there is someone willing to invest their time in teaching, mentoring, and sponsoring you, then you’ve found your bagel.

Think about what you’re hoping to accomplish and keep an open mind to unexpected venues for mentorship and skill development. That bagel may be in your division or department, or it may be somewhere else in your institution, or it may not be in your institution at all but elsewhere regionally or nationally. The sequence is important. What’s your cream cheese? Figured it out? Great, now go find that bagel.

Many of us are interested in developing or refining our skillsets. To do so, we need mentorship, which in the still-young field of hospital medicine can sometimes be challenging to obtain.

As a physician-investigator and editor, I commonly encounter young and even mid-career physicians wrestling with how to develop or refine their academic skills, and they’re usually pondering the challenges in finding someone in their own division or hospitalist group to help them. When this happens, I talk to them about bagels and cream cheese. I ask them two questions: “What’s your cream cheese?” and “Where’s your bagel?” Their natural reaction of puzzlement, perhaps mixed with hunger if they haven’t yet had breakfast, is similar to the one you’ve likely just experienced, so let me explain.

In medical school, I had a friend who absolutely loved cream cheese. If it had been socially acceptable, he would have simply walked around scooping cream cheese from a large tub. Had he done that, people would likely have given him funny looks and taken a few steps away. So, instead, my friend found an acceptable solution, which is that he would eat a lot of bagels. And those bagels would be piled high with cream cheese because what he wanted was the cream cheese and the bagel provided a reasonable means by which to get it.

So now I ask you: What’s your passion? What is the thing that you want to scoop from the tub (of learning and doing) every day for the rest of your life? That’s the cream cheese. Now, all you have to do is to find your bagel, the vehicle that allows you to get there.

Let’s see those principles in action. Say that you’re a hospitalist who wants to learn how to conduct randomized clinical trials, enhance medication reconciliation, or improve transitions of care. You can read about randomization schemes or improvement cycles but that’s clearly not enough. You need someone to help you frame the question, understand how to navigate the system, and avoid potential pitfalls. You need someone with relevant experience and expertise, someone with whom you can discuss nuances such as the trade-offs between different outcome measures or analytic approaches. You need your bagel.

There may not be anyone in your division with such expertise. You may need to branch out to find that bagel. You talk to a few people and they all point you to a cardiologist who runs clinical trials. What other field has such witty study acronyms as MRFIT or MIRACL or PROVE IT? If you’re interested in medication reconciliation, they may direct you to a pharmacist who studies medication errors. If you’re interested in improving care transitions, they may connect you with a critical care physician with expertise in interhospital transfers. You can meet with these folks to learn about their work. If their personality and mentorship style are a good fit, you can offer to assist in some aspect of their ongoing studies and, in return, ask for mentorship. You may have only a limited interest in the clinical content area, but if there is someone willing to invest their time in teaching, mentoring, and sponsoring you, then you’ve found your bagel.

Think about what you’re hoping to accomplish and keep an open mind to unexpected venues for mentorship and skill development. That bagel may be in your division or department, or it may be somewhere else in your institution, or it may not be in your institution at all but elsewhere regionally or nationally. The sequence is important. What’s your cream cheese? Figured it out? Great, now go find that bagel.

Many of us are interested in developing or refining our skillsets. To do so, we need mentorship, which in the still-young field of hospital medicine can sometimes be challenging to obtain.

As a physician-investigator and editor, I commonly encounter young and even mid-career physicians wrestling with how to develop or refine their academic skills, and they’re usually pondering the challenges in finding someone in their own division or hospitalist group to help them. When this happens, I talk to them about bagels and cream cheese. I ask them two questions: “What’s your cream cheese?” and “Where’s your bagel?” Their natural reaction of puzzlement, perhaps mixed with hunger if they haven’t yet had breakfast, is similar to the one you’ve likely just experienced, so let me explain.

In medical school, I had a friend who absolutely loved cream cheese. If it had been socially acceptable, he would have simply walked around scooping cream cheese from a large tub. Had he done that, people would likely have given him funny looks and taken a few steps away. So, instead, my friend found an acceptable solution, which is that he would eat a lot of bagels. And those bagels would be piled high with cream cheese because what he wanted was the cream cheese and the bagel provided a reasonable means by which to get it.

So now I ask you: What’s your passion? What is the thing that you want to scoop from the tub (of learning and doing) every day for the rest of your life? That’s the cream cheese. Now, all you have to do is to find your bagel, the vehicle that allows you to get there.