User login

The estimated glomerular filtration rate as a test for chronic kidney disease: Problems and solutions

At the American Society of Nephrology Renal Week 2010, one of the authors (A.D.R.) presented the following question at an In-Depth Nephrology Course on Geriatric Nephrology:

A 65-year-old woman donated a kidney to her son. Before donation, her serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL, her estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 56 mL/min/1.73 m2, and her measured GFR was 82 mL/min/1.73 m2, which was below the 2.5th percentile for 20-year-old potential kidney donors. The patient had no albuminuria or hypertension and was otherwise healthy. The kidney was biopsied during the transplant surgery. The biopsy revealed 2 of 20 glomeruli as globally sclerosed, a focus of tubular atrophy, and mild arteriosclerosis (findings present in less than 2.5% of 20-year-old donors).

Choose one. Prior to donation, this woman had:

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD), and she should not have donated her kidney

- CKD, but kidney donation was reasonable

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, and should not have donated her kidney

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, but kidney donation was reasonable

Using an electronic response system, 36 (82%) of 44 physicians in the audience chose the last option, even though this patient meets the current definition of CKD (an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and has chronic parenchymal damage documented by a kidney biopsy.

PROBLEMS WITH THE GFR AND CKD CLASSIFICATION

This question highlights several key problems with the GFR and CKD classification.

First, in low-risk populations such as potential kidney donors, serum-creatinine-based equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Study (CKD-EPI) equation substantially underestimate the GFR.1

Second, many healthy older adults with normal serum creatinine levels have an estimated GFR and a measured GFR below the normal range for young adults.2

Third, many healthy older adults have evidence of chronic parenchymal damage on renal biopsy, unlike healthy young adults.3

Finally, many health care providers did not previously recognize that people with a normal serum creatinine level could have a reduced GFR, and widespread use of the estimated GFR has addressed this problem. However, many physicians remain skeptical about efforts this past decade to classify age-related changes in kidney function as a “disease” in the absence of a clear benefit to older patients.4

TWO POINTS ABOUT THE ESTIMATED GFR

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Simon and colleagues5 provide a balanced assessment of the benefits and pitfalls of using the estimated GFR in clinical practice. Two points they make deserve further discussion:

Bigger people make more creatinine. GFR can be reported in units of milliliters per minute, or in units normalized to body surface area (mL/min/1.73 m2). Contemporary equations for identifying and classifying CKD use the latter, because the GFR is considered inappropriately low when metabolic waste is not being adequately cleared. It is intuitive that smaller people require less absolute GFR than larger people, who generate more metabolic waste. Indexing GFR to 1.73 m2 assumes that body surface area is a good surrogate for metabolic waste generation. However, whether body surface area is the best surrogate for the rate of metabolic waste generation has long been a subject of debate.6

The relationship between GFR and serum creatinine is not linear. Due to the inverse relationship between serum creatinine and GFR, a small change in serum creatinine from 0.9 to 1.2 mg/dL will represent a relatively large change in GFR (eg, 85 to 65 mL/min/1.73 m2), whereas a large change in serum creatinine from 5 to 9 mg/dL will represent a smaller change in GFR (eg, 10 to 5 mL/min/1.73 m2). The latter may be of great concern since it represents a fall in GFR to levels at which dialysis is likely needed. With the former, subtle changes in serum creatinine represent large changes in GFR, but there is also much more day-to-day variability in GFR in the normal or near-normal range than in the advanced range of kidney disease. This is one of the reasons the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations were developed, using logarithmic models that emphasize percentage instead of absolute differences in GFR.

BEYOND CREATININE?

As Simon and colleagues point out,5 although serum creatinine is a flawed surrogate for GFR, there are many problems with determining GFR by other means.

Direct GFR measurement relies on the use of an exogenous marker such as inulin or iothalamate that is infused or injected, followed by timed urine and plasma measurements to calculate GFR by the urinary clearance method (UV/P, where U is the concentration of the marker in the urine, V is the urine volume, and P is the concentration of the marker in the plasma). Alternatively, timed plasma measurements of the marker alone can be used to determine GFR by the plasma clearance method. The problem is that direct GFR measurement is costly, invasive, imprecise, time-consuming, and impractical in most clinical settings.

Exogenous markers for determining GFR are chosen because they are metabolically inert, are cleared by glomerular filtration without tubular secretion or reabsorption, and have no extrarenal clearance via the liver or intestines. Endogenous markers such as serum creatinine do not fulfill all of these ideal criteria.

Simon and colleagues highlight the problem of using the estimated GFR to screen for CKD in populations of ostensibly healthy persons.5 The MDRD and CKD-EPI equations contain demographic variables to approximate the creatinine generation rate. The primary source of creatinine generation is muscle, and the coefficients in these equations reflect the higher muscle mass of younger individuals, males, and African Americans. However, any creatinine-based equation is fundamentally flawed because overall health also affects muscle mass: healthy people have greater muscle mass than people with chronic illness, including those with CKD. Therefore, at the same serum creatinine level, a healthy person has a higher GFR than a patient with CKD.1,7 This problem leads to circular reasoning, since you need to know whether the patient has CKD or is healthy in order to accurately estimate GFR, but estimated GFR is being used to determine whether the patient is healthy or has CKD.

Therefore, other endogenous markers that are also eliminated via glomerular filtration, such as cystatin C, have been used to construct equations that estimate GFR. Unfortunately, factors other than GFR, such as inflammation, can also influence blood cystatin C levels. This in turn impairs the accuracy of equations that use cystatin C to estimate GFR in the general population.8 No known endogenous marker of GFR can be used in all patients without any confounding factors.

To rectify this problem, recent studies have investigated the use of a confirmatory test to determine which patients with a creatinine-based estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 actually have kidney disease or have a false-positive result due to higher-than-average creatinine generation. Both albuminuria and elevated serum cystatin C are examples of useful confirmatory tests that substantially decrease the misdiagnosis of CKD in healthy adults with an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.9,10

Imagine if we identified and staged systemic lupus erythematosus on the basis of antinuclear antibody levels alone: this would parallel the current approach that largely uses serum creatinine alone to classify CKD. Confirmatory tests and considering patient-specific risk factors could avoid potential harm to healthy individuals and yet retain gains that have been made to improve the interpretation of serum creatinine levels in CKD patients.

- Tent H, Rook M, Stevens LA, et a.l Renal function equations before and after living kidney donation: a within-individual comparison of performance at different levels of renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1960–1968.

- Poggio ED, Rule AD, Tanchanco R, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with glomerular filtration rates in living kidney donors. Kidney Int 2009; 75:1079–1087.

- Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:561–567.

- Spence D. Bad medicine: chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2010; 340:c3188.

- Simon J, Amde M, Poggio E. Interpreting the estimated glomerular filtration rate in the primary care setting: benefits and pitfalls. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:189–195.

- Daugirdas JT, Meyer K, Greene T, Butler RS, Poggio ED. Scaling of measured glomerular filtration rate in kidney donor candidates by anthropometric estimates of body surface area, body water, metabolic rate, or liver size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4:1575–1583.

- Rule AD, Larson TS, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ, Cosio FG. Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:929–937.

- Eriksen BO, Mathisen UD, Melsom T, et al. Cystatin C is not a better estimator of GFR than plasma creatinine in the general population. Kidney Int 2010; 78:1305–1311.

- Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:12–21.

- Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Cystatin C identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:147–155.

At the American Society of Nephrology Renal Week 2010, one of the authors (A.D.R.) presented the following question at an In-Depth Nephrology Course on Geriatric Nephrology:

A 65-year-old woman donated a kidney to her son. Before donation, her serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL, her estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 56 mL/min/1.73 m2, and her measured GFR was 82 mL/min/1.73 m2, which was below the 2.5th percentile for 20-year-old potential kidney donors. The patient had no albuminuria or hypertension and was otherwise healthy. The kidney was biopsied during the transplant surgery. The biopsy revealed 2 of 20 glomeruli as globally sclerosed, a focus of tubular atrophy, and mild arteriosclerosis (findings present in less than 2.5% of 20-year-old donors).

Choose one. Prior to donation, this woman had:

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD), and she should not have donated her kidney

- CKD, but kidney donation was reasonable

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, and should not have donated her kidney

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, but kidney donation was reasonable

Using an electronic response system, 36 (82%) of 44 physicians in the audience chose the last option, even though this patient meets the current definition of CKD (an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and has chronic parenchymal damage documented by a kidney biopsy.

PROBLEMS WITH THE GFR AND CKD CLASSIFICATION

This question highlights several key problems with the GFR and CKD classification.

First, in low-risk populations such as potential kidney donors, serum-creatinine-based equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Study (CKD-EPI) equation substantially underestimate the GFR.1

Second, many healthy older adults with normal serum creatinine levels have an estimated GFR and a measured GFR below the normal range for young adults.2

Third, many healthy older adults have evidence of chronic parenchymal damage on renal biopsy, unlike healthy young adults.3

Finally, many health care providers did not previously recognize that people with a normal serum creatinine level could have a reduced GFR, and widespread use of the estimated GFR has addressed this problem. However, many physicians remain skeptical about efforts this past decade to classify age-related changes in kidney function as a “disease” in the absence of a clear benefit to older patients.4

TWO POINTS ABOUT THE ESTIMATED GFR

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Simon and colleagues5 provide a balanced assessment of the benefits and pitfalls of using the estimated GFR in clinical practice. Two points they make deserve further discussion:

Bigger people make more creatinine. GFR can be reported in units of milliliters per minute, or in units normalized to body surface area (mL/min/1.73 m2). Contemporary equations for identifying and classifying CKD use the latter, because the GFR is considered inappropriately low when metabolic waste is not being adequately cleared. It is intuitive that smaller people require less absolute GFR than larger people, who generate more metabolic waste. Indexing GFR to 1.73 m2 assumes that body surface area is a good surrogate for metabolic waste generation. However, whether body surface area is the best surrogate for the rate of metabolic waste generation has long been a subject of debate.6

The relationship between GFR and serum creatinine is not linear. Due to the inverse relationship between serum creatinine and GFR, a small change in serum creatinine from 0.9 to 1.2 mg/dL will represent a relatively large change in GFR (eg, 85 to 65 mL/min/1.73 m2), whereas a large change in serum creatinine from 5 to 9 mg/dL will represent a smaller change in GFR (eg, 10 to 5 mL/min/1.73 m2). The latter may be of great concern since it represents a fall in GFR to levels at which dialysis is likely needed. With the former, subtle changes in serum creatinine represent large changes in GFR, but there is also much more day-to-day variability in GFR in the normal or near-normal range than in the advanced range of kidney disease. This is one of the reasons the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations were developed, using logarithmic models that emphasize percentage instead of absolute differences in GFR.

BEYOND CREATININE?

As Simon and colleagues point out,5 although serum creatinine is a flawed surrogate for GFR, there are many problems with determining GFR by other means.

Direct GFR measurement relies on the use of an exogenous marker such as inulin or iothalamate that is infused or injected, followed by timed urine and plasma measurements to calculate GFR by the urinary clearance method (UV/P, where U is the concentration of the marker in the urine, V is the urine volume, and P is the concentration of the marker in the plasma). Alternatively, timed plasma measurements of the marker alone can be used to determine GFR by the plasma clearance method. The problem is that direct GFR measurement is costly, invasive, imprecise, time-consuming, and impractical in most clinical settings.

Exogenous markers for determining GFR are chosen because they are metabolically inert, are cleared by glomerular filtration without tubular secretion or reabsorption, and have no extrarenal clearance via the liver or intestines. Endogenous markers such as serum creatinine do not fulfill all of these ideal criteria.

Simon and colleagues highlight the problem of using the estimated GFR to screen for CKD in populations of ostensibly healthy persons.5 The MDRD and CKD-EPI equations contain demographic variables to approximate the creatinine generation rate. The primary source of creatinine generation is muscle, and the coefficients in these equations reflect the higher muscle mass of younger individuals, males, and African Americans. However, any creatinine-based equation is fundamentally flawed because overall health also affects muscle mass: healthy people have greater muscle mass than people with chronic illness, including those with CKD. Therefore, at the same serum creatinine level, a healthy person has a higher GFR than a patient with CKD.1,7 This problem leads to circular reasoning, since you need to know whether the patient has CKD or is healthy in order to accurately estimate GFR, but estimated GFR is being used to determine whether the patient is healthy or has CKD.

Therefore, other endogenous markers that are also eliminated via glomerular filtration, such as cystatin C, have been used to construct equations that estimate GFR. Unfortunately, factors other than GFR, such as inflammation, can also influence blood cystatin C levels. This in turn impairs the accuracy of equations that use cystatin C to estimate GFR in the general population.8 No known endogenous marker of GFR can be used in all patients without any confounding factors.

To rectify this problem, recent studies have investigated the use of a confirmatory test to determine which patients with a creatinine-based estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 actually have kidney disease or have a false-positive result due to higher-than-average creatinine generation. Both albuminuria and elevated serum cystatin C are examples of useful confirmatory tests that substantially decrease the misdiagnosis of CKD in healthy adults with an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.9,10

Imagine if we identified and staged systemic lupus erythematosus on the basis of antinuclear antibody levels alone: this would parallel the current approach that largely uses serum creatinine alone to classify CKD. Confirmatory tests and considering patient-specific risk factors could avoid potential harm to healthy individuals and yet retain gains that have been made to improve the interpretation of serum creatinine levels in CKD patients.

At the American Society of Nephrology Renal Week 2010, one of the authors (A.D.R.) presented the following question at an In-Depth Nephrology Course on Geriatric Nephrology:

A 65-year-old woman donated a kidney to her son. Before donation, her serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL, her estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 56 mL/min/1.73 m2, and her measured GFR was 82 mL/min/1.73 m2, which was below the 2.5th percentile for 20-year-old potential kidney donors. The patient had no albuminuria or hypertension and was otherwise healthy. The kidney was biopsied during the transplant surgery. The biopsy revealed 2 of 20 glomeruli as globally sclerosed, a focus of tubular atrophy, and mild arteriosclerosis (findings present in less than 2.5% of 20-year-old donors).

Choose one. Prior to donation, this woman had:

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD), and she should not have donated her kidney

- CKD, but kidney donation was reasonable

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, and should not have donated her kidney

- Age-related (senescent) changes in her kidneys, but kidney donation was reasonable

Using an electronic response system, 36 (82%) of 44 physicians in the audience chose the last option, even though this patient meets the current definition of CKD (an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and has chronic parenchymal damage documented by a kidney biopsy.

PROBLEMS WITH THE GFR AND CKD CLASSIFICATION

This question highlights several key problems with the GFR and CKD classification.

First, in low-risk populations such as potential kidney donors, serum-creatinine-based equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Study (CKD-EPI) equation substantially underestimate the GFR.1

Second, many healthy older adults with normal serum creatinine levels have an estimated GFR and a measured GFR below the normal range for young adults.2

Third, many healthy older adults have evidence of chronic parenchymal damage on renal biopsy, unlike healthy young adults.3

Finally, many health care providers did not previously recognize that people with a normal serum creatinine level could have a reduced GFR, and widespread use of the estimated GFR has addressed this problem. However, many physicians remain skeptical about efforts this past decade to classify age-related changes in kidney function as a “disease” in the absence of a clear benefit to older patients.4

TWO POINTS ABOUT THE ESTIMATED GFR

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Simon and colleagues5 provide a balanced assessment of the benefits and pitfalls of using the estimated GFR in clinical practice. Two points they make deserve further discussion:

Bigger people make more creatinine. GFR can be reported in units of milliliters per minute, or in units normalized to body surface area (mL/min/1.73 m2). Contemporary equations for identifying and classifying CKD use the latter, because the GFR is considered inappropriately low when metabolic waste is not being adequately cleared. It is intuitive that smaller people require less absolute GFR than larger people, who generate more metabolic waste. Indexing GFR to 1.73 m2 assumes that body surface area is a good surrogate for metabolic waste generation. However, whether body surface area is the best surrogate for the rate of metabolic waste generation has long been a subject of debate.6

The relationship between GFR and serum creatinine is not linear. Due to the inverse relationship between serum creatinine and GFR, a small change in serum creatinine from 0.9 to 1.2 mg/dL will represent a relatively large change in GFR (eg, 85 to 65 mL/min/1.73 m2), whereas a large change in serum creatinine from 5 to 9 mg/dL will represent a smaller change in GFR (eg, 10 to 5 mL/min/1.73 m2). The latter may be of great concern since it represents a fall in GFR to levels at which dialysis is likely needed. With the former, subtle changes in serum creatinine represent large changes in GFR, but there is also much more day-to-day variability in GFR in the normal or near-normal range than in the advanced range of kidney disease. This is one of the reasons the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations were developed, using logarithmic models that emphasize percentage instead of absolute differences in GFR.

BEYOND CREATININE?

As Simon and colleagues point out,5 although serum creatinine is a flawed surrogate for GFR, there are many problems with determining GFR by other means.

Direct GFR measurement relies on the use of an exogenous marker such as inulin or iothalamate that is infused or injected, followed by timed urine and plasma measurements to calculate GFR by the urinary clearance method (UV/P, where U is the concentration of the marker in the urine, V is the urine volume, and P is the concentration of the marker in the plasma). Alternatively, timed plasma measurements of the marker alone can be used to determine GFR by the plasma clearance method. The problem is that direct GFR measurement is costly, invasive, imprecise, time-consuming, and impractical in most clinical settings.

Exogenous markers for determining GFR are chosen because they are metabolically inert, are cleared by glomerular filtration without tubular secretion or reabsorption, and have no extrarenal clearance via the liver or intestines. Endogenous markers such as serum creatinine do not fulfill all of these ideal criteria.

Simon and colleagues highlight the problem of using the estimated GFR to screen for CKD in populations of ostensibly healthy persons.5 The MDRD and CKD-EPI equations contain demographic variables to approximate the creatinine generation rate. The primary source of creatinine generation is muscle, and the coefficients in these equations reflect the higher muscle mass of younger individuals, males, and African Americans. However, any creatinine-based equation is fundamentally flawed because overall health also affects muscle mass: healthy people have greater muscle mass than people with chronic illness, including those with CKD. Therefore, at the same serum creatinine level, a healthy person has a higher GFR than a patient with CKD.1,7 This problem leads to circular reasoning, since you need to know whether the patient has CKD or is healthy in order to accurately estimate GFR, but estimated GFR is being used to determine whether the patient is healthy or has CKD.

Therefore, other endogenous markers that are also eliminated via glomerular filtration, such as cystatin C, have been used to construct equations that estimate GFR. Unfortunately, factors other than GFR, such as inflammation, can also influence blood cystatin C levels. This in turn impairs the accuracy of equations that use cystatin C to estimate GFR in the general population.8 No known endogenous marker of GFR can be used in all patients without any confounding factors.

To rectify this problem, recent studies have investigated the use of a confirmatory test to determine which patients with a creatinine-based estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 actually have kidney disease or have a false-positive result due to higher-than-average creatinine generation. Both albuminuria and elevated serum cystatin C are examples of useful confirmatory tests that substantially decrease the misdiagnosis of CKD in healthy adults with an estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.9,10

Imagine if we identified and staged systemic lupus erythematosus on the basis of antinuclear antibody levels alone: this would parallel the current approach that largely uses serum creatinine alone to classify CKD. Confirmatory tests and considering patient-specific risk factors could avoid potential harm to healthy individuals and yet retain gains that have been made to improve the interpretation of serum creatinine levels in CKD patients.

- Tent H, Rook M, Stevens LA, et a.l Renal function equations before and after living kidney donation: a within-individual comparison of performance at different levels of renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1960–1968.

- Poggio ED, Rule AD, Tanchanco R, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with glomerular filtration rates in living kidney donors. Kidney Int 2009; 75:1079–1087.

- Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:561–567.

- Spence D. Bad medicine: chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2010; 340:c3188.

- Simon J, Amde M, Poggio E. Interpreting the estimated glomerular filtration rate in the primary care setting: benefits and pitfalls. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:189–195.

- Daugirdas JT, Meyer K, Greene T, Butler RS, Poggio ED. Scaling of measured glomerular filtration rate in kidney donor candidates by anthropometric estimates of body surface area, body water, metabolic rate, or liver size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4:1575–1583.

- Rule AD, Larson TS, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ, Cosio FG. Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:929–937.

- Eriksen BO, Mathisen UD, Melsom T, et al. Cystatin C is not a better estimator of GFR than plasma creatinine in the general population. Kidney Int 2010; 78:1305–1311.

- Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:12–21.

- Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Cystatin C identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:147–155.

- Tent H, Rook M, Stevens LA, et a.l Renal function equations before and after living kidney donation: a within-individual comparison of performance at different levels of renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1960–1968.

- Poggio ED, Rule AD, Tanchanco R, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with glomerular filtration rates in living kidney donors. Kidney Int 2009; 75:1079–1087.

- Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:561–567.

- Spence D. Bad medicine: chronic kidney disease. BMJ 2010; 340:c3188.

- Simon J, Amde M, Poggio E. Interpreting the estimated glomerular filtration rate in the primary care setting: benefits and pitfalls. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:189–195.

- Daugirdas JT, Meyer K, Greene T, Butler RS, Poggio ED. Scaling of measured glomerular filtration rate in kidney donor candidates by anthropometric estimates of body surface area, body water, metabolic rate, or liver size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4:1575–1583.

- Rule AD, Larson TS, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ, Cosio FG. Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:929–937.

- Eriksen BO, Mathisen UD, Melsom T, et al. Cystatin C is not a better estimator of GFR than plasma creatinine in the general population. Kidney Int 2010; 78:1305–1311.

- Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:12–21.

- Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Cystatin C identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:147–155.

Hospitalists in Disaster Response

In the last decade, natural disasters such as the Indonesian tsunami of 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2004, and the Pakistani earthquake of 2005 have brought attention to the importance of diverse but complementary medical professional roles in humanitarian medical aid.14 Natural disasters that cause significant physical trauma to large populations often necessitate initial multidisciplinary responder teams comprised of surgeons, anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, surgical technologists, nurses, psychiatrists, and public health specialists. Their roles are to manage life‐threatening injuries, provide immediate triage, help affected individuals deal with intense psychological shock, and address critical population‐based needs such as water, food, and sanitation. Meanwhile, general medical, pediatric, rehabilitative, and long‐term psychiatric services often constitute a secondary tier of disaster response, providing postsurgical care, managing acute medical illnesses, mitigating psychological trauma, rehabilitating injuries, and providing vaccinations to at‐risk individuals. Hospitalists can play an important role in postcatastrophe recovery services as experts in acute care, stewards of care transitions, and drivers of systems improvement.

The earthquake that occurred January 12, 2010 in Haiti is a dramatic illustration of the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to disaster relief. The 7.0‐magnitude earthquake near Port‐au‐Prince ravaged an already crippled health care system, severely damaging the country's primary academic medical center, and killed the entire class of second‐year nursing students. The death toll has been estimated to be nearly one‐quarter of a million people.5 Victims awaiting surgery, recovering from surgery, or in need of other immediate medical attention quickly inundated any existing health facilities. The following stories describe the authors' respective experiences in Haiti after the earthquake.

JC: I arrived 4 days after the earthquake to a hospital outside of Port‐au‐Prince, spared from destruction, but filled with hundreds of patients with crush injuries and severe fractures. On rounds with the surgical team, I observed that venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis had not yet been initiated, and I was concerned that patients might die from pulmonary embolism. In the overwhelming urgency of providing life‐saving surgery to as many patients as possible, this simple measure had been overlooked. After discussion with our team and our Haitian medical colleagues, we initiated subcutaneous heparin on all eligible patients and made arrangements to receive further shipments of heparin to accommodate the influx of patients.

A nearby school and church had been annexed into makeshift extensions of the hospital wards. The volume and pace of incoming injuries was such that as soon as a patient was taken to surgery, another patient would often take his or her place in the bed. The rapid movement of patients to and from x‐ray, surgery, and postsurgical care created challenges around effective and accurate communication among multiple care providers. We decided that nonsurgical personnel would triage newly arriving patients and round on patients daily. Each nonsurgical physician was responsible for staffing a particular location. This zone‐defense approach ensured that the surgeons maximized their time in the operating rooms. We also instituted a basic system of portable medical records kept with each patient at all times, allowing personnel to easily and quickly assess care given to date, and to write notes and orders.

Presurgical and postsurgical wound infections became a common event, with the risk of ensuing sepsis. Antibiotic use was dependent on the preferences of individual surgeons and also on the available supply. As a result, antimicrobial treatments were highly variable and sometimes inadequate. The internists on the team proposed standard antibiotic guidelines for open fractures, for contaminated wounds, and for postoperative wounds; these regimens were approved and implemented by Haitian staff and the rest of the team.

Internists recognized the first complications of rhabdomyolysis from crush injuries and delays in receiving medical attention. Malaise, oliguria, and volume overload were often the only clues we had for severe renal failure. We had a functional lab capable of checking complete blood counts, urinalysis and creatinine, but we had a limited supply of serum potassium assays. We only used the latter in confirmed cases of rhabdomyolysis, and on several occasions we diagnosed severe hyperkalemia. Using bedside automated electrical defibrillation devices for monitoring, we sustained these patients on calcium gluconate until they could be transferred to an external dialysis unit run by Mdecins Sans Frontires in Port‐au‐Prince.6 As the number of rhabdomyolysis cases increased, we instigated creatinine rounds on patients arriving with large crush injuries, and we evaluated urine output daily until patients were clinically stable from this threat. We also helped the Haitian staff treat the omnipresent problem of pain and advised renal dosing of medications in renal failure and elderly patients.

GH: The situation 3 months after the earthquake was medically less dire but highlights the evolving importance of generalists in the aftermath of the quake.710 For many Haitian patients, the earthquake had become a universal point of reference for their symptomatology. Anorexia, amenorrhea, headaches, epigastric pain, even fungating soft tissue masses, were all reported to be depi tranbleman t a (since the earthquake) and were often somatic manifestations of a psychologically devastating event. At a hospital in Carrefour, I cared for patients presenting with dramatic sequelae of chronic diseases that had been undertreated due to the destruction of the Haitian medical infrastructurehypertensive coma, diabetic ketoacidosis, cerebral malaria, decompensated liver disease, and severe chronic anemia (including a patient with a hemoglobin of 3 mg/dL). I encountered many patients with infections exacerbated by excessive crowding in tent communities, such as typhoid and tuberculosis. At this particular hospital, priorities appropriately placed on surgical and postsurgical care required the team to devise creative solutions for the care and placement of medical patients, such as restructuring the emergency department and creating a rehabilitation tent on the hospital grounds. While few Haitian internists were present, a number of Haitian obstetricians were on site and helped manage medical conditions within the scope of their experience, such as hypertension, abdominal pain, and genitourinary infections. The expatriate orthopedic surgeons on site sought the consultative skills of hospitalists for preoperative management, postoperative complications, and comorbid conditions.

This hospital was largely sustained by rotating teams of volunteers, which underscored the importance of establishing a flexible system that would accommodate the turnover of personnel and fluctuating levels of professional expertise. The team used a tiered model for acute care delivery designating responsibilities based on the number of nurses, physicians, and other providers available. We collaborated with Haitian physicians to establish a routine of handoff rounds. Finally, we created and centralized documentation such as clinical protocols, contact numbers, and helpful tips for our successors.

Hospitalists have valuable skills to offer in medical responses to natural catastrophes.5 Our fluency with acute care environments becomes a pluripotent asset in disaster relief. Our experiences in assessing acuity are vital in assisting with inpatient triage. Our familiarity with the comanagement model facilitates partnership with other disciplines to optimize the distribution of skill sets without neglecting the overall well‐being of patients. Our clinical expertise in treating the vulnerable elderly, VTE, renal failure, pain management, postoperative infections, sepsis, and many other conditions can bolster medical relief efforts, even when the foremost need is surgical. The hospitalist's core competencies in healthcare systems11 can support recovery initiatives in medical facilities, particularly in the domains of drug safety, resource allocation, information management, team‐based methods, and care transitions. Our respective experiences also suggest the potential value of hospitalists in domestic, in addition to international, disaster response initiatives. Since large‐scale calamities may result in the hospitalization of overwhelming numbers of victims,12 hospitalists may be well‐positioned to assist our emergency medicine and public health colleagues, who currently (and fittingly) lead domestic efforts in disaster relief.

Tragedies like the earthquake in Haiti serve as a sobering reminder that a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach is required as medical disaster relief shifts from a life‐saving focus to one of life‐preserving care.13, 14 Hospitalists can play a vital role in these restorative efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their hospitalist colleagues at Beth Israel Deaconess who generously covered our shifts and encouraged us to write about our experiences.

- ,.Health impact of the 2004 Andaman Nicobar earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia.Prehosp Disaster Med.2009;24(6):493–499.

- ,,,.Medical response to hurricanes Katrina and Rita: local public health preparedness in action.J Public Health Manag Pract.2007;13(5):441–446.

- .Nephrology in earthquakes: sharing experiences and information.Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.2007;2(4):803–808.

- The Hospitalist. November2005. Hurricane Katrina: tragedy and hope. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/255673/Hurricane_Katrina_Tragedy_and_Hope.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Washington Post. February 10,2010. Haiti raises earthquake toll to 230,000. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp‐dyn/content/article/2010/02/09/AR2010020904447.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Médecins sans Frontiéres. About us. Available at: http://www.msf.org/msfinternational/aboutmsf/. Accessed August 2010.

- ,,, et al.Practicing internal medicine onboard the USNS COMFORT in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(11):733–737.

- Minnesota Medicine. April2010. Help for Haiti. Available at: http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/PastIssues/April2010/CoverstoryApril2010/tabid/3370/Default.aspx. Accessed August 2010.

- The Hospitalist. April2010. Hospitalists in Haiti. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/590287/Hospitalists_in_Haiti.html. Accessed August 2010.

- .Haiti earthquake relief, phase two–long‐term needs and local resources.N Engl J Med.2010;362(20):1858–1861.

- ,,,,.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med.2006;(1 Suppl 1):2–95.

- ,,, et al.The impact of the Tsunami on hospitalizations at the tertiary care hospital in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka.Am J Disaster Med.2008;3(3):147–155.

- ,,.Short communication: patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters ‐ a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.Trop Med Int Health.2007;12(11):1338–1341.

- ,,.Characterisation of patients treated at the Red Cross field hospital in Kashmir during the first three weeks of operation.Emerg Med J.2006;23(8):654–656.

In the last decade, natural disasters such as the Indonesian tsunami of 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2004, and the Pakistani earthquake of 2005 have brought attention to the importance of diverse but complementary medical professional roles in humanitarian medical aid.14 Natural disasters that cause significant physical trauma to large populations often necessitate initial multidisciplinary responder teams comprised of surgeons, anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, surgical technologists, nurses, psychiatrists, and public health specialists. Their roles are to manage life‐threatening injuries, provide immediate triage, help affected individuals deal with intense psychological shock, and address critical population‐based needs such as water, food, and sanitation. Meanwhile, general medical, pediatric, rehabilitative, and long‐term psychiatric services often constitute a secondary tier of disaster response, providing postsurgical care, managing acute medical illnesses, mitigating psychological trauma, rehabilitating injuries, and providing vaccinations to at‐risk individuals. Hospitalists can play an important role in postcatastrophe recovery services as experts in acute care, stewards of care transitions, and drivers of systems improvement.

The earthquake that occurred January 12, 2010 in Haiti is a dramatic illustration of the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to disaster relief. The 7.0‐magnitude earthquake near Port‐au‐Prince ravaged an already crippled health care system, severely damaging the country's primary academic medical center, and killed the entire class of second‐year nursing students. The death toll has been estimated to be nearly one‐quarter of a million people.5 Victims awaiting surgery, recovering from surgery, or in need of other immediate medical attention quickly inundated any existing health facilities. The following stories describe the authors' respective experiences in Haiti after the earthquake.

JC: I arrived 4 days after the earthquake to a hospital outside of Port‐au‐Prince, spared from destruction, but filled with hundreds of patients with crush injuries and severe fractures. On rounds with the surgical team, I observed that venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis had not yet been initiated, and I was concerned that patients might die from pulmonary embolism. In the overwhelming urgency of providing life‐saving surgery to as many patients as possible, this simple measure had been overlooked. After discussion with our team and our Haitian medical colleagues, we initiated subcutaneous heparin on all eligible patients and made arrangements to receive further shipments of heparin to accommodate the influx of patients.

A nearby school and church had been annexed into makeshift extensions of the hospital wards. The volume and pace of incoming injuries was such that as soon as a patient was taken to surgery, another patient would often take his or her place in the bed. The rapid movement of patients to and from x‐ray, surgery, and postsurgical care created challenges around effective and accurate communication among multiple care providers. We decided that nonsurgical personnel would triage newly arriving patients and round on patients daily. Each nonsurgical physician was responsible for staffing a particular location. This zone‐defense approach ensured that the surgeons maximized their time in the operating rooms. We also instituted a basic system of portable medical records kept with each patient at all times, allowing personnel to easily and quickly assess care given to date, and to write notes and orders.

Presurgical and postsurgical wound infections became a common event, with the risk of ensuing sepsis. Antibiotic use was dependent on the preferences of individual surgeons and also on the available supply. As a result, antimicrobial treatments were highly variable and sometimes inadequate. The internists on the team proposed standard antibiotic guidelines for open fractures, for contaminated wounds, and for postoperative wounds; these regimens were approved and implemented by Haitian staff and the rest of the team.

Internists recognized the first complications of rhabdomyolysis from crush injuries and delays in receiving medical attention. Malaise, oliguria, and volume overload were often the only clues we had for severe renal failure. We had a functional lab capable of checking complete blood counts, urinalysis and creatinine, but we had a limited supply of serum potassium assays. We only used the latter in confirmed cases of rhabdomyolysis, and on several occasions we diagnosed severe hyperkalemia. Using bedside automated electrical defibrillation devices for monitoring, we sustained these patients on calcium gluconate until they could be transferred to an external dialysis unit run by Mdecins Sans Frontires in Port‐au‐Prince.6 As the number of rhabdomyolysis cases increased, we instigated creatinine rounds on patients arriving with large crush injuries, and we evaluated urine output daily until patients were clinically stable from this threat. We also helped the Haitian staff treat the omnipresent problem of pain and advised renal dosing of medications in renal failure and elderly patients.

GH: The situation 3 months after the earthquake was medically less dire but highlights the evolving importance of generalists in the aftermath of the quake.710 For many Haitian patients, the earthquake had become a universal point of reference for their symptomatology. Anorexia, amenorrhea, headaches, epigastric pain, even fungating soft tissue masses, were all reported to be depi tranbleman t a (since the earthquake) and were often somatic manifestations of a psychologically devastating event. At a hospital in Carrefour, I cared for patients presenting with dramatic sequelae of chronic diseases that had been undertreated due to the destruction of the Haitian medical infrastructurehypertensive coma, diabetic ketoacidosis, cerebral malaria, decompensated liver disease, and severe chronic anemia (including a patient with a hemoglobin of 3 mg/dL). I encountered many patients with infections exacerbated by excessive crowding in tent communities, such as typhoid and tuberculosis. At this particular hospital, priorities appropriately placed on surgical and postsurgical care required the team to devise creative solutions for the care and placement of medical patients, such as restructuring the emergency department and creating a rehabilitation tent on the hospital grounds. While few Haitian internists were present, a number of Haitian obstetricians were on site and helped manage medical conditions within the scope of their experience, such as hypertension, abdominal pain, and genitourinary infections. The expatriate orthopedic surgeons on site sought the consultative skills of hospitalists for preoperative management, postoperative complications, and comorbid conditions.

This hospital was largely sustained by rotating teams of volunteers, which underscored the importance of establishing a flexible system that would accommodate the turnover of personnel and fluctuating levels of professional expertise. The team used a tiered model for acute care delivery designating responsibilities based on the number of nurses, physicians, and other providers available. We collaborated with Haitian physicians to establish a routine of handoff rounds. Finally, we created and centralized documentation such as clinical protocols, contact numbers, and helpful tips for our successors.

Hospitalists have valuable skills to offer in medical responses to natural catastrophes.5 Our fluency with acute care environments becomes a pluripotent asset in disaster relief. Our experiences in assessing acuity are vital in assisting with inpatient triage. Our familiarity with the comanagement model facilitates partnership with other disciplines to optimize the distribution of skill sets without neglecting the overall well‐being of patients. Our clinical expertise in treating the vulnerable elderly, VTE, renal failure, pain management, postoperative infections, sepsis, and many other conditions can bolster medical relief efforts, even when the foremost need is surgical. The hospitalist's core competencies in healthcare systems11 can support recovery initiatives in medical facilities, particularly in the domains of drug safety, resource allocation, information management, team‐based methods, and care transitions. Our respective experiences also suggest the potential value of hospitalists in domestic, in addition to international, disaster response initiatives. Since large‐scale calamities may result in the hospitalization of overwhelming numbers of victims,12 hospitalists may be well‐positioned to assist our emergency medicine and public health colleagues, who currently (and fittingly) lead domestic efforts in disaster relief.

Tragedies like the earthquake in Haiti serve as a sobering reminder that a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach is required as medical disaster relief shifts from a life‐saving focus to one of life‐preserving care.13, 14 Hospitalists can play a vital role in these restorative efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their hospitalist colleagues at Beth Israel Deaconess who generously covered our shifts and encouraged us to write about our experiences.

In the last decade, natural disasters such as the Indonesian tsunami of 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2004, and the Pakistani earthquake of 2005 have brought attention to the importance of diverse but complementary medical professional roles in humanitarian medical aid.14 Natural disasters that cause significant physical trauma to large populations often necessitate initial multidisciplinary responder teams comprised of surgeons, anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, surgical technologists, nurses, psychiatrists, and public health specialists. Their roles are to manage life‐threatening injuries, provide immediate triage, help affected individuals deal with intense psychological shock, and address critical population‐based needs such as water, food, and sanitation. Meanwhile, general medical, pediatric, rehabilitative, and long‐term psychiatric services often constitute a secondary tier of disaster response, providing postsurgical care, managing acute medical illnesses, mitigating psychological trauma, rehabilitating injuries, and providing vaccinations to at‐risk individuals. Hospitalists can play an important role in postcatastrophe recovery services as experts in acute care, stewards of care transitions, and drivers of systems improvement.

The earthquake that occurred January 12, 2010 in Haiti is a dramatic illustration of the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to disaster relief. The 7.0‐magnitude earthquake near Port‐au‐Prince ravaged an already crippled health care system, severely damaging the country's primary academic medical center, and killed the entire class of second‐year nursing students. The death toll has been estimated to be nearly one‐quarter of a million people.5 Victims awaiting surgery, recovering from surgery, or in need of other immediate medical attention quickly inundated any existing health facilities. The following stories describe the authors' respective experiences in Haiti after the earthquake.

JC: I arrived 4 days after the earthquake to a hospital outside of Port‐au‐Prince, spared from destruction, but filled with hundreds of patients with crush injuries and severe fractures. On rounds with the surgical team, I observed that venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis had not yet been initiated, and I was concerned that patients might die from pulmonary embolism. In the overwhelming urgency of providing life‐saving surgery to as many patients as possible, this simple measure had been overlooked. After discussion with our team and our Haitian medical colleagues, we initiated subcutaneous heparin on all eligible patients and made arrangements to receive further shipments of heparin to accommodate the influx of patients.

A nearby school and church had been annexed into makeshift extensions of the hospital wards. The volume and pace of incoming injuries was such that as soon as a patient was taken to surgery, another patient would often take his or her place in the bed. The rapid movement of patients to and from x‐ray, surgery, and postsurgical care created challenges around effective and accurate communication among multiple care providers. We decided that nonsurgical personnel would triage newly arriving patients and round on patients daily. Each nonsurgical physician was responsible for staffing a particular location. This zone‐defense approach ensured that the surgeons maximized their time in the operating rooms. We also instituted a basic system of portable medical records kept with each patient at all times, allowing personnel to easily and quickly assess care given to date, and to write notes and orders.

Presurgical and postsurgical wound infections became a common event, with the risk of ensuing sepsis. Antibiotic use was dependent on the preferences of individual surgeons and also on the available supply. As a result, antimicrobial treatments were highly variable and sometimes inadequate. The internists on the team proposed standard antibiotic guidelines for open fractures, for contaminated wounds, and for postoperative wounds; these regimens were approved and implemented by Haitian staff and the rest of the team.

Internists recognized the first complications of rhabdomyolysis from crush injuries and delays in receiving medical attention. Malaise, oliguria, and volume overload were often the only clues we had for severe renal failure. We had a functional lab capable of checking complete blood counts, urinalysis and creatinine, but we had a limited supply of serum potassium assays. We only used the latter in confirmed cases of rhabdomyolysis, and on several occasions we diagnosed severe hyperkalemia. Using bedside automated electrical defibrillation devices for monitoring, we sustained these patients on calcium gluconate until they could be transferred to an external dialysis unit run by Mdecins Sans Frontires in Port‐au‐Prince.6 As the number of rhabdomyolysis cases increased, we instigated creatinine rounds on patients arriving with large crush injuries, and we evaluated urine output daily until patients were clinically stable from this threat. We also helped the Haitian staff treat the omnipresent problem of pain and advised renal dosing of medications in renal failure and elderly patients.

GH: The situation 3 months after the earthquake was medically less dire but highlights the evolving importance of generalists in the aftermath of the quake.710 For many Haitian patients, the earthquake had become a universal point of reference for their symptomatology. Anorexia, amenorrhea, headaches, epigastric pain, even fungating soft tissue masses, were all reported to be depi tranbleman t a (since the earthquake) and were often somatic manifestations of a psychologically devastating event. At a hospital in Carrefour, I cared for patients presenting with dramatic sequelae of chronic diseases that had been undertreated due to the destruction of the Haitian medical infrastructurehypertensive coma, diabetic ketoacidosis, cerebral malaria, decompensated liver disease, and severe chronic anemia (including a patient with a hemoglobin of 3 mg/dL). I encountered many patients with infections exacerbated by excessive crowding in tent communities, such as typhoid and tuberculosis. At this particular hospital, priorities appropriately placed on surgical and postsurgical care required the team to devise creative solutions for the care and placement of medical patients, such as restructuring the emergency department and creating a rehabilitation tent on the hospital grounds. While few Haitian internists were present, a number of Haitian obstetricians were on site and helped manage medical conditions within the scope of their experience, such as hypertension, abdominal pain, and genitourinary infections. The expatriate orthopedic surgeons on site sought the consultative skills of hospitalists for preoperative management, postoperative complications, and comorbid conditions.

This hospital was largely sustained by rotating teams of volunteers, which underscored the importance of establishing a flexible system that would accommodate the turnover of personnel and fluctuating levels of professional expertise. The team used a tiered model for acute care delivery designating responsibilities based on the number of nurses, physicians, and other providers available. We collaborated with Haitian physicians to establish a routine of handoff rounds. Finally, we created and centralized documentation such as clinical protocols, contact numbers, and helpful tips for our successors.

Hospitalists have valuable skills to offer in medical responses to natural catastrophes.5 Our fluency with acute care environments becomes a pluripotent asset in disaster relief. Our experiences in assessing acuity are vital in assisting with inpatient triage. Our familiarity with the comanagement model facilitates partnership with other disciplines to optimize the distribution of skill sets without neglecting the overall well‐being of patients. Our clinical expertise in treating the vulnerable elderly, VTE, renal failure, pain management, postoperative infections, sepsis, and many other conditions can bolster medical relief efforts, even when the foremost need is surgical. The hospitalist's core competencies in healthcare systems11 can support recovery initiatives in medical facilities, particularly in the domains of drug safety, resource allocation, information management, team‐based methods, and care transitions. Our respective experiences also suggest the potential value of hospitalists in domestic, in addition to international, disaster response initiatives. Since large‐scale calamities may result in the hospitalization of overwhelming numbers of victims,12 hospitalists may be well‐positioned to assist our emergency medicine and public health colleagues, who currently (and fittingly) lead domestic efforts in disaster relief.

Tragedies like the earthquake in Haiti serve as a sobering reminder that a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach is required as medical disaster relief shifts from a life‐saving focus to one of life‐preserving care.13, 14 Hospitalists can play a vital role in these restorative efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their hospitalist colleagues at Beth Israel Deaconess who generously covered our shifts and encouraged us to write about our experiences.

- ,.Health impact of the 2004 Andaman Nicobar earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia.Prehosp Disaster Med.2009;24(6):493–499.

- ,,,.Medical response to hurricanes Katrina and Rita: local public health preparedness in action.J Public Health Manag Pract.2007;13(5):441–446.

- .Nephrology in earthquakes: sharing experiences and information.Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.2007;2(4):803–808.

- The Hospitalist. November2005. Hurricane Katrina: tragedy and hope. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/255673/Hurricane_Katrina_Tragedy_and_Hope.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Washington Post. February 10,2010. Haiti raises earthquake toll to 230,000. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp‐dyn/content/article/2010/02/09/AR2010020904447.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Médecins sans Frontiéres. About us. Available at: http://www.msf.org/msfinternational/aboutmsf/. Accessed August 2010.

- ,,, et al.Practicing internal medicine onboard the USNS COMFORT in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(11):733–737.

- Minnesota Medicine. April2010. Help for Haiti. Available at: http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/PastIssues/April2010/CoverstoryApril2010/tabid/3370/Default.aspx. Accessed August 2010.

- The Hospitalist. April2010. Hospitalists in Haiti. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/590287/Hospitalists_in_Haiti.html. Accessed August 2010.

- .Haiti earthquake relief, phase two–long‐term needs and local resources.N Engl J Med.2010;362(20):1858–1861.

- ,,,,.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med.2006;(1 Suppl 1):2–95.

- ,,, et al.The impact of the Tsunami on hospitalizations at the tertiary care hospital in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka.Am J Disaster Med.2008;3(3):147–155.

- ,,.Short communication: patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters ‐ a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.Trop Med Int Health.2007;12(11):1338–1341.

- ,,.Characterisation of patients treated at the Red Cross field hospital in Kashmir during the first three weeks of operation.Emerg Med J.2006;23(8):654–656.

- ,.Health impact of the 2004 Andaman Nicobar earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia.Prehosp Disaster Med.2009;24(6):493–499.

- ,,,.Medical response to hurricanes Katrina and Rita: local public health preparedness in action.J Public Health Manag Pract.2007;13(5):441–446.

- .Nephrology in earthquakes: sharing experiences and information.Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.2007;2(4):803–808.

- The Hospitalist. November2005. Hurricane Katrina: tragedy and hope. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/255673/Hurricane_Katrina_Tragedy_and_Hope.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Washington Post. February 10,2010. Haiti raises earthquake toll to 230,000. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp‐dyn/content/article/2010/02/09/AR2010020904447.html. Accessed August 2010.

- Médecins sans Frontiéres. About us. Available at: http://www.msf.org/msfinternational/aboutmsf/. Accessed August 2010.

- ,,, et al.Practicing internal medicine onboard the USNS COMFORT in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake.Ann Intern Med.2010;152(11):733–737.

- Minnesota Medicine. April2010. Help for Haiti. Available at: http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/PastIssues/April2010/CoverstoryApril2010/tabid/3370/Default.aspx. Accessed August 2010.

- The Hospitalist. April2010. Hospitalists in Haiti. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/590287/Hospitalists_in_Haiti.html. Accessed August 2010.

- .Haiti earthquake relief, phase two–long‐term needs and local resources.N Engl J Med.2010;362(20):1858–1861.

- ,,,,.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med.2006;(1 Suppl 1):2–95.

- ,,, et al.The impact of the Tsunami on hospitalizations at the tertiary care hospital in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka.Am J Disaster Med.2008;3(3):147–155.

- ,,.Short communication: patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters ‐ a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.Trop Med Int Health.2007;12(11):1338–1341.

- ,,.Characterisation of patients treated at the Red Cross field hospital in Kashmir during the first three weeks of operation.Emerg Med J.2006;23(8):654–656.

Understanding Hospital Readmissions

Hospital readmissions pose a major problem both to the patient and the fiscal stability of our health care system.1 Many interventions have attempted to tackle this problem. Interventions exist that utilize transition coaches working intensively with hospitalized patients or nurses performing postdischarge home visits or phoning patients.2, 3 Although beneficial, these strategies are costly and require additional, highly trained personnel. Consequently, they have been difficult to sustain financially in a fee‐for‐service environment, and difficult to generalize at other locales. Recent policies to decrease hospital payments for readmissions will incentivize hospitals to implement discharge programs.4 However, all hospital systems will still want to do this in the most efficient manner possible.

One important way to maximize benefits and minimize costs is to target the most intensive, expensive interventions to the highest risk patients who are most likely to be rehospitalized. By targeting the highest risk patients, we could significantly reduce costs. However, models predicting rehospitalization have had limited accuracy, even for condition‐specific models such as heart failure. Two studies in this issue work to better identify high‐risk patients. Mudge and colleagues5 prospectively examined risk factors for recurrent readmissions in an Australian hospital and found that chronic disease, depression, and underweight were independent risk factors for repeat readmission. Allaudeen6 examined risk factors for readmission to their own institution among general medicine patients. In a retrospective analysis of administrative data, they found that several variables predicted hospital readmission, including black race, insurance coverage through Medicaid, prescription of steroids or narcotics, and diagnoses of heart failure, renal disease, cancer, anemia, and weight loss.

These studies raise two questions that are critical if we are to develop better predictive modeling of who will benefit most from intensive interventions to reduce readmissions. First, what are the risk factors for preventable hospitalizations? People with multiple readmissions seem an obvious target on which to focus. However, it may be that these individuals are just very sick with multiple comorbidities, and many of their readmissions may not be preventable. Rich and colleagues reported that a multidisciplinary discharge intervention reduced readmissions for heart failure by 56%.7 What is often forgotten is that in their pilot study they were not able to reduce admissions for the most severely ill, and their final study population excluded the sickest patients. By targeting moderate‐risk patients, they were able to reduce readmissions significantly.8 In the studies by Mudge et al.5 and Allaudeen,6 the fact that chronic diseases predicted rehospitalization is only moderately helpful. It is possible, perhaps likely, that many of the readmissions for heart failure were preventable while many of the readmissions for cancer were not. The challenge for researchers is to develop methods for classifying admissions/readmissions as preventable.9 Using a defined set of diagnostic categories to classify readmissions (eg, ambulatory care sensitive conditions) may misclassify many cases.10 Determining preventable hospitalizations through detailed chart review is expensive and may have limited interobserver reliability. Nevertheless, physician review and classification may be necessary for future research to advance the field.

Second, what predictor variables are causally related to preventable hospitalizations (and presumably actionable), and which are merely markers of true causal factors and therefore harder to interpret and more difficult to act upon? In addition to chronic disease, Mudge et al.5 found that depression and low body mass index were independent risk factors for readmission. These conditions often go hand in hand. Patients who are burdened with chronic disease may be depressed and not eat. Conversely, patients who are depressed may not eat and allow their chronic disease to worsen. But it seems that depression is the more likely of the two to be causal. Depression is an important predictor of medication nonadherence and worsening illness.11, 12 Screening hospitalized patients for depression could provide valuable information on which patients may need treatment or more rigorous postdischarge follow‐up. In contrast, being underweight may not truly cause readmissions, but could be a marker of frailty and difficulty in meeting activities of daily living.

Similarly, Allaudeen6 found that black race, Medicaid use, steroid use, and narcotic use were independently associated with hospital readmission (in addition to chronic diseases and weight loss). Can being on steroids or narcotics cause readmissions? Does enrollment in Medicaid or being of black race cause one to be readmitted? While these may be markers which are statistically significant, they are unlikely to be true causes of rehospitalization. It is more likely that these variables are markers for true causal factors, such as financial barriers to medications or access barriers to primary care. Many other studies have used administrative databases to examine variables linked to readmission. We need to drill deeper to determine what is actually causing readmissions. Did the patient misinterpret how to take their steroid taper or were they so sick that they needed to return to the hospital? Perhaps they decided to wait on taking the steroids until they spoke with their primary care physician. This deeper level of understanding cannot be ascertained through third party administrative data sets. Primary data collection is needed to correctly determine who to target and the specific foci of interventions.

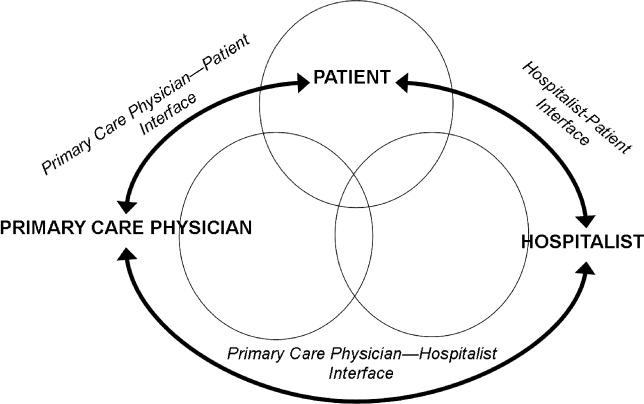

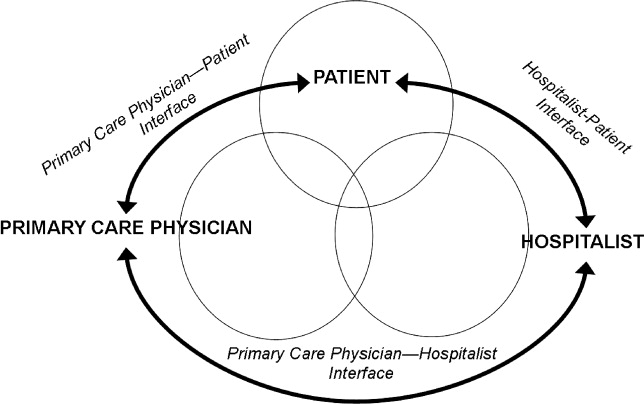

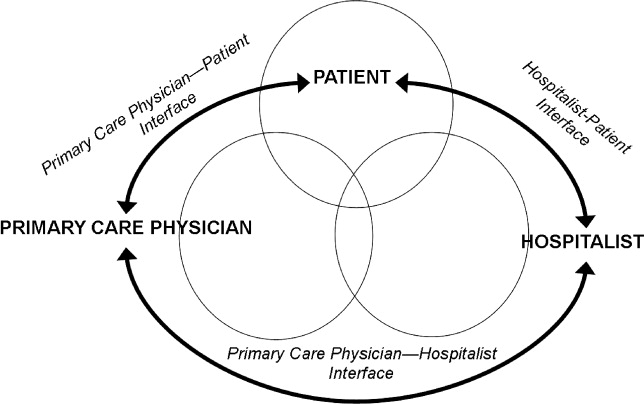

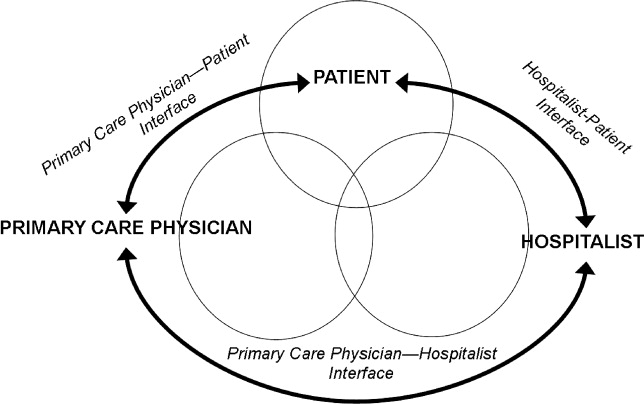

Future research on risk factors for readmissions (and interventions to decrease readmissions) should begin with a theoretical framework that addresses the patient, the hospital, and the receiving outpatient primary care physician or specialist, and the interfaces between each pair that could lead to preventable readmissions (see Figure 1).

With every potential variable affecting readmission, we need to systematically evaluate whether they are causal and preventable. When a variable is both causal and modifiable, we can then develop interventions to target these variables. We designed Table 1 as a framework to consider when moving forward in creating and implementing interventions.

| Factor | Potential Intervention |

|---|---|

| |

| Patient | |

| Cognition | Screening for cognition at discharge. Increase support at home. Inclusion of surrogate or caregiver in explaining discharge instructions. Additional use of a surrogate in explaining discharge instructions. |

| Depression | Screening for depression during the hospitalization and at discharge. Treatment of depression. Increased outpatient support to monitor depression. |

| Health literacy | Screening for health literacy. Involvement of hospital staff, social support network, and outpatient primary care physician to reinforce discharge instructions. |

| Support at home | Assess home support for patient. Increase phone call and home aid support following discharge for those with inadequate support. |

| Functional ability | Assess physical function throughout hospitalization and at discharge. Involve physical therapy early in the hospitalization and postdischarge. |

| Financial assets | Assess ability to pay for medications and transportation to follow‐up appointments. Work with social work on improving access. |

| Chronic disease (ie, congestive heart failure) | Improve patient education of disease and medications. Increase home support to monitor health status. Increase frequency of outpatient visits as needed. |

| Primary care physician | |

| PatientPCP interface | Via phone call to patient at discharge, reinforce so the patient understands disease process (eg, heart failure exacerbation triggers), will take medications started during hospitalization, and recognizes early precipitants of hospitalization. |

| PCPHospitalist interface | Encourage adequate communication about past medical problems and individualized issues pertinent to care plans. |

| Quality of outpatient primary care | Adhere to guidelines of care recommended by advisory standards. Ensure patients receive optimal outpatient care. |

| Medication reconciliation | Ensure that admission and discharge medication reconciliation is perfect. Update outpatient medication list with inpatient medication changes. |

| Follow‐up of pending tests | Create trigger system of pending tests for recently discharged patients. |

| Access to rapid follow‐up appointments | Incentivize physicians of recently discharged patients to offer follow‐up appointments in 1 week or less. |

| Hospitalist | |

| PatientHospitalist interface | Improve communication with patient on how to access physicians if residual postdischarge questions. |

| HospitalistPCP interface | Encourage adequate communication of hospital course and postdischarge plan. |

| Quality of inpatient hospital care | Ensure patients receive optimal inpatient care. Assess patient clinical stability and determine optimal time for discharge. |

| Written discharge instructions | Create easily understandable discharge instructions. Install checks to limit human errors. Ensure patient has copy on discharge. |

| Verbal discharge instructions | Learn to use teach‐back methodology to assess patient understanding of discharge instructions. Work to eliminate multiple sources (eg, consulting physicians, nurses, therapists) giving conflicting verbal discharge information. |

| Medication reconciliation | Utilize outpatient physician notes and pharmacy records to corroborate patient lists. Ensure that admission and discharge medication reconciliation is perfect. |

| Pending tests | Ensure discharge summary includes information and is communicated to PCP for follow‐up in timely manner. |

| Home services | Arrange for home support and nursing services to assist with patients needs postdischarge. Assess whether the patient knows of pending home services and means of contacting services if they do not occur. |

To advance this area, we need to be stringent about how we perform research and interpret findings. Studies that examine risk factors for readmission to a single hospital may be biased; for example, in the study by Allaudeen,6 it is possible that patients with Medicaid may have been equally likely to be readmitted to any hospital but more likely to be readmitted to the hospital that was the sole source of admission data. Even if findings from a single site are valid, they may not be generalizable. Ideally, studies of risk factors (and interventions to reduce readmissions) should be conducted in multiple sites that can track all hospitalizations and examine differences in risk factors for rehospitalization across hospitals. We have learned a tremendous amount over the last few years about risk markers for all‐cause readmission, and interventions to improve safety and quality of transitions in care. To advance further, multicenter studies are needed that focus on plausible causal variables of preventable readmissions and risk factors beyond the walls of the hospital (eg, access and quality of outpatient care for newly discharged patients). Only then will we better understand which patients can have their readmissions prevented and how to improve upon current strategies to improve outcomes.

- ,,. Nationwide Frequency and Costs of Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations,2006. April 2009. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb72.jsp. Accessed December 8, 2010.

- ,,,,,.Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the care transitions intervention.J Am Geriatr Soc.2004;52(11):1817–1825.

- ,,, et al.A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial.Ann Int Med.2009;150(3):178–187.

- Sec. 3025.Hospital readmissions reduction program. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. HR 3590. Acts of Congress, 111th second session. January 5,2010.

- ,,,,,,.Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study.J Hosp Med.2011;6 (this issue).

- ,,,.Redefining identifiable readmission risk factors for general medicine patients.J Hosp Med.2011;6 (this issue).

- ,,,,,.A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure.N Engl J Med.1995;333(18):1190–1195.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of readmission in elderly patients with congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, randomized pilot study.J Gen Intern Med.1993;8(11):585–590.

- ,,,,,.Hospital readmissions and quality of care.Med Care.1999;37(5):490–501.

- ,,,.Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians.Public Health.2009;123(2):169–173.

- ,,,,.Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients.Kidney Int.2009;75(11):1223–1229.

- ,,, et al.Depression, medication adherence, and service utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus.Arthritis Rheum.2009;61(2):240–246.

Hospital readmissions pose a major problem both to the patient and the fiscal stability of our health care system.1 Many interventions have attempted to tackle this problem. Interventions exist that utilize transition coaches working intensively with hospitalized patients or nurses performing postdischarge home visits or phoning patients.2, 3 Although beneficial, these strategies are costly and require additional, highly trained personnel. Consequently, they have been difficult to sustain financially in a fee‐for‐service environment, and difficult to generalize at other locales. Recent policies to decrease hospital payments for readmissions will incentivize hospitals to implement discharge programs.4 However, all hospital systems will still want to do this in the most efficient manner possible.