User login

Testosterone supplementation in women: When, why, and how

There are no currently US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for testosterone use in women. Its use by clinicians is through dose modification of FDA-approved therapies for men, or preparations created by compounding pharmacies. Recently, several professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), North American Menopause Society, International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health, and the International Society for Sexual Medicine, convened an expert panel to develop a global position statement on testosterone therapy for women.1 In this roundtable for OBG Management, moderated by Mickey Karram, MD, several experts discuss this position statement as well as the overall clinical advantages and drawbacks of using testosterone in women.

Testosterone indications

Mickey Karram, MD: For which indications do you prescribe testosterone supplementation in women?

Lauren Streicher, MD: I offer systemic testosterone therapy to postmenopausal women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and low serum testosterone levels, with one caveat—it is important that the patient’s reported distressing lack of libido is not explained by another condition or circumstance. Many women present reporting low libido but, on further questioning, it is typically revealed that dyspareunia precipitated their loss of interest in sex. It is normal to not want to do something that is painful. In addition, low libido can often be explained by chronic disease, such as diabetes, cancer, or clinical depression.

Some medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), frequently cause a decline in sexual interest. Finally, psychosocial and partner issues may be the culprit.

James Simon, MD, CCP, NCMP, IF: Much of the beneficial data for testosterone’s use is for sexual function in postmenopausal women.2 Female sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent among women during the postmenopause.3 Androgen levels progressively decrease throughout adult life in all women, so the postmenopausal additional lack of estrogen has a recognized effect on genitourinary health. There is evidence that the insufficiency of androgens as well as estrogens after menopause can lead to genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM).4

Testosterone also is used for increasing strength, lean muscle mass, bone mineral density, and sense of well-being.5

Rebecca Glaser, MD: I consider testosterone supplementation in my clinical practice in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women for symptoms of androgen/hormone deficiency, including diminished sense of well-being; dysphoric mood; anxiety; irritability; fatigue; decreased libido, sexual activity, or pleasure; vasomotor instability; bone loss; decreased muscle strength; insomnia; changes in cognition; memory loss; urinary symptoms; incontinence; vaginal atrophy and dryness; and joint and muscular pain. We also have shown through preliminary and short-term data and case studies that testosterone therapy has a potential beneficial effect on migraine headaches, as well as active breast cancers in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.6-10

Continue to: What is appropriate bloodwork?...

What is appropriate bloodwork?

Dr. Karram: Do you obtain blood work before initiating testosterone treatment? If so, what tests do you order and what testosterone levels are considered to be normal for premenopausal and postmenopausal women?

Dr. Streicher: Unlike estrogen, which is predictably low in a postmenopausal woman, serum testosterone (T) levels are highly variable because of the adrenal component. Ovarian testosterone production does not cease at the same time as estrogen production. So I do obtain total and free T levels, prior to initiating treatment. Having said that, it has been well established that T levels correlate poorly with level of sexual interest, and there is no specific blood level that can be used to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction. We all have patients who have nonexistent T levels and have a very healthy libido, and other women with sky-high levels who have no libido. But it is useful to know levels prior to initiating therapy to be able to monitor levels throughout treatment. Also, if levels are in the premenopausal physiologic range, not only is she unlikely to respond but she is also at risk for developing androgenic adverse effects, such as acne and hair growth. In general, a low free T level (even if it is in the normal postmenopausal range) in a clinical setting of HSDD supports supplementation.

The assessment and interpretation of T levels can be challenging, particularly as the majority of testosterone is protein-bound and biologically inactive. Free T levels (the biologically active testosterone) in many labs are unreliable and need to be calculated.

In addition to total and free T, I check levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), the protein that binds testosterone and renders it biologically inactive. If someone has high SHBG levels and is taking an oral estrogen, simply switching to a transdermal estrogen will result in decreased SHBG and increased free T.

Levels of total and free T vary from lab to lab, so it is best to be familiar with those ranges and then be consistent in which lab you choose.

Dr. Glaser: Although I personally do order blood work on most patients (T, free T, estradiol, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone), after 15 years of research and publishing data on testosterone implants, I do not believe that T levels are absolutely necessary or even beneficial in most cases. It rarely changes management in my patients.

As Lauren said, it is well known that T levels do not correlate with androgen deficiency symptoms or clinical conditions caused by androgen deficiency. If a patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency, a trial of testosterone therapy should be given.

T levels are not a valid marker of tissue exposure in women, reflecting less than 20% of total androgen activity. The major source of testosterone in pre and postmenopausal women is the local intracrine production of testosterone from the adrenal precursor steroids dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, which would not be reflected in T levels.

In our study involving 300 women, we found no relationship between baseline T levels, presenting symptoms, or response to therapy.6 Premenopausal and postmenopausal women had similar baseline T levels and similar response to therapy. Even women with baseline T levels in the mid-range responded to therapy.

Some of the most controversial topics in treating women with testosterone are related to dosing and T levels throughout therapy. Guideline authors often use the terms ‘physiologic dosing’ and ‘physiologic ranges’ when making recommendations for therapy. Although “physiologic” sounds appropriate/ scientific, these rigid opinions/recommendations are not evidence based. There are no data supporting the use of endogenous T ranges to guide dosing or monitor testosterone therapy.

The decision to initiate testosterone therapy is a clinical decision between the doctor and the patient based on the patient’s symptomatology, which is the therapeutic endpoint. Testosterone therapy must be done with adequate doses determined by clinical effect (benefits) versus side effects or adverse events (risks). T levels may be helpful, along with clinical evaluation when troubleshooting.

Utilizing data from thousands of patients, we have developed serum ranges for testosterone implants.11 Even so, no two patients are the same, nor do they respond to therapy the same. It is always a clinical decision.

Continue to: Dr. Simon...

Dr. Simon: In the recent global consensus statement on testosterone use,1 the experts were in agreement that “no cut-off blood level can be used for any measured circulating androgen to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction.” They give their recommendation a C, and I agree that testosterone supplementation, with specific dosage levels, are a clinical decision.

Before initiating testosterone therapy, it is recommended that liver function and fasting lipids are assessed, as liver disease and hyperlipidemia are contraindications to treatment. These levels should be monitored twice in the first year and annually thereafter while the patient is taking testosterone. Breast and pelvic examinations, mammography, and evaluation for abnormal bleeding should be performed as well as the blood tests.12 These recommendations are focused on safety not efficacy.

Administration route

Dr. Karram: How do you administer testosterone, and why?

Dr. Streicher: As there are no FDA approved testosterone products for women, clinicians must determine the dosage and route of delivery based on published clinical trials.

Dr. Glaser: I treat patients with subcutaneous pellet implants. The implants provide consistent and continuous delivery of therapeutic amounts of testosterone. There is a reason testosterone pellets have been used for more than 80 years and are more popular now than ever—they work. The insertion procedure is simple and takes about 2 minutes. The treatment is cost-effective, avoids first pass, has no adverse effect on the liver or clotting factors, and there is no transference. Decades of data support both the efficacy and safety of testosterone implants.6 However, testosterone implants are not regulated by the FDA and all patients are required to sign a consent informing them of off-label use, benefits, and risks of testosterone implant therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the consent is important, as there is no package labeling to warn of possible side effects.

Dr. Streicher: Oral testosterone therapy, because of its first pass through the liver and association with adverse lipid profiles with negative effects on high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, is not recommended. I prefer a transdermal approach. Pellets, implants, and injections have the potential to result in supraphysiologic blood concentrations. It must be emphasized that the goal of treatment is to approximate premenopausal physiologic levels. More is not better; excessive levels do not demonstrate a greater sexual response and are in fact more likely to have a negative impact due to androgenic side effects.

In most clinical trials, a 300 mg/d testosterone patch was effective, but these patches are not commercially available so I rely on transdermal gel from a compounding pharmacy. The typical dose needed to raise levels into the high to normal range for most women is 2.5 mg up to 5 mg per day of testosterone 1%, which translates to roughly 1 mL. Many pharmacies provide a dispenser, which allots the appropriate dose. Alternatively, I instruct the patient to place a dollop on her thigh (roughly in size of a single M&M candy).

I always tell my patients that the response is not immediate, typically taking 8 to 12 weeks for the effect to become clinically significant. I generally see a patient back 8 weeks after initiation of treatment to check T levels and evaluate response.

Dr. Simon: There are some data demonstrating that intravaginal testosterone can be a potential treatment for GSM. Intravaginal testosterone coupled with aromatase inhibitor therapy used for breast cancer treatment resulted in supraphysiologic T levels and reportedly improved vaginal maturation index and reduced dyspareunia. More study is needed.13

Dr. Streicher: Agreed. The lower third of the vagina and the vestibule is rich in testosterone receptors. Like Dr. Simon, in some cases of vaginal atrophy I prescribe a compounded local vaginal testosterone.

Continue to: Testosterone and premenopausal women...

Testosterone and premenopausal women

Dr. Karram: Is there a role for testosterone supplementation in premenopausal women with normal estrogen production?

Dr. Glaser: Yes. In fact, in our study, more than one-third of the patients were premenopausal, which makes sense.6 There is a marked decline of T levels and the adrenal precursor steroids (DHEA and androstenedione) in women between the ages of 20–30 years and around age 50. As we said, symptoms of androgen deficiency often occur prior to menopause and are not related to estrogen levels. In our study, testosterone implant therapy relieved symptoms of hormone (androgen) deficiency, including vasomotor symptoms, sleep problems, depressive mood, irritability, anxiety, physical and mental exhaustion (fatigue, memory issues), sexual problems, bladder problems (incontinence, frequency), vaginal dryness, and joint and muscular pain. Premenopausal and postmenopausal patients reported similar hormone deficiency symptoms. Premenopausal women did report a higher incidence of psychological complaints (depressive mood, anxiety, and irritability), while postmenopausal women reported more hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and urologic symptoms. Both groups demonstrated similar improvement in symptoms.

In addition, we have seen relief of severe migraine headache in premenopausal (as well as postmenopausal) women treated with testosterone implant therapy.6,7

Dr. Streicher: The goal of testosterone supplementation is to approximate physiological testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women. While testosterone may improve well-being and sexual function in premenopausal women, the data are limited and really inconclusive. More study is needed given that there is likely a wide therapeutic range with many variables. Having said that, there are some data that indicate that testosterone in premenopausal women may enhance general sense of well-being.14

Why is there no FDA-approved agent?

Dr. Karram: Why do you think the FDA has been reluctant to approve a testosterone agent for women?

Dr. Simon: Three potential testosterone drugs for use in women have been unsuccessfully brought to market after the FDA did not approve them. There are 31 approved products for men, each of which were approved because they safely restored normal testosterone concentrations in men with reduced levels and an associated medical condition. Unlike this scenario for men, for women, the FDA has required products to show clinical effectiveness in trials. For instance, Estratest, a combination estrogen-testosterone product, was in use in the 1960s—approved for women with estrogen-resistant hot flushes, and used in practice for sexual dysfunction. After the FDA implemented its Drug Efficacy Study and Implementation regulation system after 2000, which required safety and efficacy trial(s) before drug approval, the manufacturer removed the drug from market when presented efficacy study data for the added testosterone in the drug were deemed inadequate.15

Dr. Streicher: We have yet another example of the disparity between the FDA approval processes for sexual function drugs for men versus women. Take Intrinsia as another example. It was a 300-mg testosterone patch that underwent clinical trials in women who were post-oophorectomy with HSDD. The patch had demonstrated efficacy with minimal adverse effects and no statistically significant dangerous effects. However, the FDA declined approval, citing “safety considerations” and requested longer-term clinical trials to evaluate potential cardiovascular or breast problems. Given that Intrinsia supplementation simply restored normal physiologic testosterone levels, and there was no such requirement in men who received supplementation post-orchiectomy, this requirement was nonsensical and unjustified.

Compounded formulations

Dr. Karram: Are compounding pharmacies appropriately regulated, and how can you be assured that the source of your testosterone is appropriate?

Dr. Glaser: Compounding pharmacies are regulated by the State Boards of Pharmacy, Drug Enforcement Agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, State Bureaus of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and Departments of Health (in some states).

Compounding is a highly regulated profession that is constantly under scrutiny by agencies, patients, and physicians. Any additional regulations could adversely impact the accessibility of patients to individually compounded medications including intravenous and oncology medications. Over the past 20 years, I have treated hundreds of patients with breast cancer with compounded vaginal testosterone (with or without estriol) and subcutaneous testosterone (with or without anastrozole), greatly improving quality of life in women suffering from severe symptoms. Without the availability of compounded medications, there would have been no or limited alternatives for adequate and much needed therapy. Notably, there have been no adverse events or safety-related issues in more than 20 years.

Regarding whether or not “the source of your testosterone is appropriate,” pharmacists can only use United States Pharmacopeia (USP) grades of testosterone. Testosterone used in compounding is required by the FDA to be of USP grade from an FDA registered and compliant facility. In addition, compounding support companies run additional USP tests to confirm their products meet USP standards prior to being delivered to individual compounding pharmacies.

Dr. Streicher: However, there potentially can be substantial variability between formulations and batches. Product purity can also be an issue. It is reassuring if the compounding pharmacy is compliant with purity of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Good Manufacturing Practice rules and guidelines that assure the minimum requirements to assure high quality and batch-to-batch consistency. I find it helpful to always work with the same pharmacy once you have established uniformity and reliability. If there is concern, it is appropriate to check a patient’s serum level 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the problem with some compounding pharmacies is that there may be incentives back and forth with the clinician to use a certain outlet, whereby the patient’s best interest may not be served. I do believe that there is a role for compounding pharmacies, however. We also use them because some women may have strange reactions or be allergic to the preservatives, formulating agents, or even lactose, in various pills and patches, gels, and creams.

Continue to: Testosterone for aging and cognition?...

Testosterone for aging and cognition?

Dr. Karram: Do you think that testosterone supplementation in the elderly can have a positive impact on aging, Alzheimer disease, and dementia?

Dr. Streicher: The jury is still out on the cognitive effects of postmenopausal androgen supplementation. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of testosterone to enhance cognitive performance, or to delay cognitive decline. I prescribe testosterone only to treat HSDD, but I do tell my patient that she may possibly also benefit in terms of cognitive function, musculoskeletal parameters, and well-being. Large RCTs are needed in those areas to justify prescribing for those benefits alone.

Dr. Simon: I would say this is the place for future development, but where there is very likely to be a benefit is on sarcopenia.

Dr. Glaser: There is some evidence that testosterone is neuroprotective.16 In my clinical practice I have seen “self-reported” memory issues improved on therapy, often returning toward the end of the testosterone implant cycle. Adequate amounts of bioavailable testosterone at the androgen receptor are critical for optimal health, immune function, and disease prevention.

Dr. Karram: In conclusion, this expert panel agrees that testosterone supplementation is beneficial for sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women, with also many other potential benefits that require further investigation. Route of administration preferred by Dr. Simon and Dr. Streicher is transdermal or a transvaginal cream. Dr. Glaser uses a subcutaneous pellet approach. Thank you all for an engaging and informative discussion. ●

Dr. Karram: How would you treat the following patient? She is 56, postmenopausal, and taking estrogen. She reports decreased libido, fatigue, lack of sleep, and lack of focus. Would you consider testosterone supplementation?

Dr. Simon: For her libido, yes. I would not give it to her for the fatigue if it were simply lack of sleep and without an associated medical condition. For her lack of focus, the testosterone could be beneficial. The central nervous system effects of testosterone are thought to be related to the conversion of testosterone to estrogen in the brain; if a person’s getting enough estrogen, they shouldn’t have lack of focus. Since some women may not want more estrogen, administering a little testosterone for libido also offers focus because it adds to the estrogen in the brain. If after giving her adequate amounts of testosterone her libido is not better in 8 weeks, it wasn’t a testosterone problem. If she does report improvement, however, I would keep her on the agent as long as she is healthy. But most 56-year-old women who already met the criteria for going on estrogen should be fine with testosterone.

If this same patient were not reporting low libido but did report lack of strength, energy, or well-being I also would say, “Sure, give testosterone a try.”

Dr. Glaser: I also would treat her with testosterone—with pellet implants. The dose would depend on her body weight. I usually start with an approximate dose of 1 mg of testosterone per pound of body weight. This amount of testosterone delivered continuously from the implant also supplies estradiol (via aromatization) locally at the cellular level.

I would treat her for as long as she chooses to continue testosterone therapy. There is no end- or stop-date where a person no longer benefits from therapy or adverse events occur. Testosterone does not increase the risk of breast cancer and it has a positive effect on many of the adverse signs and symptoms of aging, including mental and physical deterioration.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women. Climacteric. 2019;22:429-434.

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Green S, et al. Safety and efficacy of testosterone for women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trial data. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;S2213-8587:30189-30195.

- Simon JA, Davis SR, Althof SE, et al. Sexual well-being after menopause: an International Menopause Society White Paper. Climacteric. 2018;21:415-427.

- Traish AM, Vignozzi L, Simon JA, et al. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:558-571.

- Panay N. British Menopause Society tools for clinicians: testosterone replacement in menopause. Post Reprod Health. 2019;25:40-42.

- Glaser R, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Beneficial effects of testosterone therapy in women measured by the validated Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Maturitas. 2011;68:355-361.

- Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C, Trimble N, et al. Testosterone pellet implants and migraine headaches: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2012;71:385-388.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Efficacy of subcutaneous testosterone on menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):109-109.

- Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C. Rapid response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant intramammary testosterone-anastrozole therapy: neoadjuvant hormone therapy in breast cancer. Menopause. 2014;21:673.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Subcutaneous testosterone-letrozole therapy before and concurrent with neoadjuvant breast chemotherapy: clinical response and therapeutic implications. Menopause. 2017;24:859-864.

- Glaser R, Kalantaridou S, Dimitrakakis C, et al. Testosterone implants in women: pharmacological dosing for a physiologic effect. Maturitas. 2013;74:179-184.

- International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. In press.

- Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, et al. The role of androgens in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM): International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Menopause. 2018;25:837-847.

- Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, et al. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves well-being, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:390-398.

- Simon JA, Kapner MD. The saga of testosterone for menopausal women at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). J Sex Med. 2020;17:826-829.

- Davis SR, Wahlin-Jacobsen S. Testosterone in women—the clinical significance. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3: 980-992.

There are no currently US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for testosterone use in women. Its use by clinicians is through dose modification of FDA-approved therapies for men, or preparations created by compounding pharmacies. Recently, several professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), North American Menopause Society, International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health, and the International Society for Sexual Medicine, convened an expert panel to develop a global position statement on testosterone therapy for women.1 In this roundtable for OBG Management, moderated by Mickey Karram, MD, several experts discuss this position statement as well as the overall clinical advantages and drawbacks of using testosterone in women.

Testosterone indications

Mickey Karram, MD: For which indications do you prescribe testosterone supplementation in women?

Lauren Streicher, MD: I offer systemic testosterone therapy to postmenopausal women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and low serum testosterone levels, with one caveat—it is important that the patient’s reported distressing lack of libido is not explained by another condition or circumstance. Many women present reporting low libido but, on further questioning, it is typically revealed that dyspareunia precipitated their loss of interest in sex. It is normal to not want to do something that is painful. In addition, low libido can often be explained by chronic disease, such as diabetes, cancer, or clinical depression.

Some medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), frequently cause a decline in sexual interest. Finally, psychosocial and partner issues may be the culprit.

James Simon, MD, CCP, NCMP, IF: Much of the beneficial data for testosterone’s use is for sexual function in postmenopausal women.2 Female sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent among women during the postmenopause.3 Androgen levels progressively decrease throughout adult life in all women, so the postmenopausal additional lack of estrogen has a recognized effect on genitourinary health. There is evidence that the insufficiency of androgens as well as estrogens after menopause can lead to genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM).4

Testosterone also is used for increasing strength, lean muscle mass, bone mineral density, and sense of well-being.5

Rebecca Glaser, MD: I consider testosterone supplementation in my clinical practice in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women for symptoms of androgen/hormone deficiency, including diminished sense of well-being; dysphoric mood; anxiety; irritability; fatigue; decreased libido, sexual activity, or pleasure; vasomotor instability; bone loss; decreased muscle strength; insomnia; changes in cognition; memory loss; urinary symptoms; incontinence; vaginal atrophy and dryness; and joint and muscular pain. We also have shown through preliminary and short-term data and case studies that testosterone therapy has a potential beneficial effect on migraine headaches, as well as active breast cancers in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.6-10

Continue to: What is appropriate bloodwork?...

What is appropriate bloodwork?

Dr. Karram: Do you obtain blood work before initiating testosterone treatment? If so, what tests do you order and what testosterone levels are considered to be normal for premenopausal and postmenopausal women?

Dr. Streicher: Unlike estrogen, which is predictably low in a postmenopausal woman, serum testosterone (T) levels are highly variable because of the adrenal component. Ovarian testosterone production does not cease at the same time as estrogen production. So I do obtain total and free T levels, prior to initiating treatment. Having said that, it has been well established that T levels correlate poorly with level of sexual interest, and there is no specific blood level that can be used to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction. We all have patients who have nonexistent T levels and have a very healthy libido, and other women with sky-high levels who have no libido. But it is useful to know levels prior to initiating therapy to be able to monitor levels throughout treatment. Also, if levels are in the premenopausal physiologic range, not only is she unlikely to respond but she is also at risk for developing androgenic adverse effects, such as acne and hair growth. In general, a low free T level (even if it is in the normal postmenopausal range) in a clinical setting of HSDD supports supplementation.

The assessment and interpretation of T levels can be challenging, particularly as the majority of testosterone is protein-bound and biologically inactive. Free T levels (the biologically active testosterone) in many labs are unreliable and need to be calculated.

In addition to total and free T, I check levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), the protein that binds testosterone and renders it biologically inactive. If someone has high SHBG levels and is taking an oral estrogen, simply switching to a transdermal estrogen will result in decreased SHBG and increased free T.

Levels of total and free T vary from lab to lab, so it is best to be familiar with those ranges and then be consistent in which lab you choose.

Dr. Glaser: Although I personally do order blood work on most patients (T, free T, estradiol, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone), after 15 years of research and publishing data on testosterone implants, I do not believe that T levels are absolutely necessary or even beneficial in most cases. It rarely changes management in my patients.

As Lauren said, it is well known that T levels do not correlate with androgen deficiency symptoms or clinical conditions caused by androgen deficiency. If a patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency, a trial of testosterone therapy should be given.

T levels are not a valid marker of tissue exposure in women, reflecting less than 20% of total androgen activity. The major source of testosterone in pre and postmenopausal women is the local intracrine production of testosterone from the adrenal precursor steroids dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, which would not be reflected in T levels.

In our study involving 300 women, we found no relationship between baseline T levels, presenting symptoms, or response to therapy.6 Premenopausal and postmenopausal women had similar baseline T levels and similar response to therapy. Even women with baseline T levels in the mid-range responded to therapy.

Some of the most controversial topics in treating women with testosterone are related to dosing and T levels throughout therapy. Guideline authors often use the terms ‘physiologic dosing’ and ‘physiologic ranges’ when making recommendations for therapy. Although “physiologic” sounds appropriate/ scientific, these rigid opinions/recommendations are not evidence based. There are no data supporting the use of endogenous T ranges to guide dosing or monitor testosterone therapy.

The decision to initiate testosterone therapy is a clinical decision between the doctor and the patient based on the patient’s symptomatology, which is the therapeutic endpoint. Testosterone therapy must be done with adequate doses determined by clinical effect (benefits) versus side effects or adverse events (risks). T levels may be helpful, along with clinical evaluation when troubleshooting.

Utilizing data from thousands of patients, we have developed serum ranges for testosterone implants.11 Even so, no two patients are the same, nor do they respond to therapy the same. It is always a clinical decision.

Continue to: Dr. Simon...

Dr. Simon: In the recent global consensus statement on testosterone use,1 the experts were in agreement that “no cut-off blood level can be used for any measured circulating androgen to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction.” They give their recommendation a C, and I agree that testosterone supplementation, with specific dosage levels, are a clinical decision.

Before initiating testosterone therapy, it is recommended that liver function and fasting lipids are assessed, as liver disease and hyperlipidemia are contraindications to treatment. These levels should be monitored twice in the first year and annually thereafter while the patient is taking testosterone. Breast and pelvic examinations, mammography, and evaluation for abnormal bleeding should be performed as well as the blood tests.12 These recommendations are focused on safety not efficacy.

Administration route

Dr. Karram: How do you administer testosterone, and why?

Dr. Streicher: As there are no FDA approved testosterone products for women, clinicians must determine the dosage and route of delivery based on published clinical trials.

Dr. Glaser: I treat patients with subcutaneous pellet implants. The implants provide consistent and continuous delivery of therapeutic amounts of testosterone. There is a reason testosterone pellets have been used for more than 80 years and are more popular now than ever—they work. The insertion procedure is simple and takes about 2 minutes. The treatment is cost-effective, avoids first pass, has no adverse effect on the liver or clotting factors, and there is no transference. Decades of data support both the efficacy and safety of testosterone implants.6 However, testosterone implants are not regulated by the FDA and all patients are required to sign a consent informing them of off-label use, benefits, and risks of testosterone implant therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the consent is important, as there is no package labeling to warn of possible side effects.

Dr. Streicher: Oral testosterone therapy, because of its first pass through the liver and association with adverse lipid profiles with negative effects on high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, is not recommended. I prefer a transdermal approach. Pellets, implants, and injections have the potential to result in supraphysiologic blood concentrations. It must be emphasized that the goal of treatment is to approximate premenopausal physiologic levels. More is not better; excessive levels do not demonstrate a greater sexual response and are in fact more likely to have a negative impact due to androgenic side effects.

In most clinical trials, a 300 mg/d testosterone patch was effective, but these patches are not commercially available so I rely on transdermal gel from a compounding pharmacy. The typical dose needed to raise levels into the high to normal range for most women is 2.5 mg up to 5 mg per day of testosterone 1%, which translates to roughly 1 mL. Many pharmacies provide a dispenser, which allots the appropriate dose. Alternatively, I instruct the patient to place a dollop on her thigh (roughly in size of a single M&M candy).

I always tell my patients that the response is not immediate, typically taking 8 to 12 weeks for the effect to become clinically significant. I generally see a patient back 8 weeks after initiation of treatment to check T levels and evaluate response.

Dr. Simon: There are some data demonstrating that intravaginal testosterone can be a potential treatment for GSM. Intravaginal testosterone coupled with aromatase inhibitor therapy used for breast cancer treatment resulted in supraphysiologic T levels and reportedly improved vaginal maturation index and reduced dyspareunia. More study is needed.13

Dr. Streicher: Agreed. The lower third of the vagina and the vestibule is rich in testosterone receptors. Like Dr. Simon, in some cases of vaginal atrophy I prescribe a compounded local vaginal testosterone.

Continue to: Testosterone and premenopausal women...

Testosterone and premenopausal women

Dr. Karram: Is there a role for testosterone supplementation in premenopausal women with normal estrogen production?

Dr. Glaser: Yes. In fact, in our study, more than one-third of the patients were premenopausal, which makes sense.6 There is a marked decline of T levels and the adrenal precursor steroids (DHEA and androstenedione) in women between the ages of 20–30 years and around age 50. As we said, symptoms of androgen deficiency often occur prior to menopause and are not related to estrogen levels. In our study, testosterone implant therapy relieved symptoms of hormone (androgen) deficiency, including vasomotor symptoms, sleep problems, depressive mood, irritability, anxiety, physical and mental exhaustion (fatigue, memory issues), sexual problems, bladder problems (incontinence, frequency), vaginal dryness, and joint and muscular pain. Premenopausal and postmenopausal patients reported similar hormone deficiency symptoms. Premenopausal women did report a higher incidence of psychological complaints (depressive mood, anxiety, and irritability), while postmenopausal women reported more hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and urologic symptoms. Both groups demonstrated similar improvement in symptoms.

In addition, we have seen relief of severe migraine headache in premenopausal (as well as postmenopausal) women treated with testosterone implant therapy.6,7

Dr. Streicher: The goal of testosterone supplementation is to approximate physiological testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women. While testosterone may improve well-being and sexual function in premenopausal women, the data are limited and really inconclusive. More study is needed given that there is likely a wide therapeutic range with many variables. Having said that, there are some data that indicate that testosterone in premenopausal women may enhance general sense of well-being.14

Why is there no FDA-approved agent?

Dr. Karram: Why do you think the FDA has been reluctant to approve a testosterone agent for women?

Dr. Simon: Three potential testosterone drugs for use in women have been unsuccessfully brought to market after the FDA did not approve them. There are 31 approved products for men, each of which were approved because they safely restored normal testosterone concentrations in men with reduced levels and an associated medical condition. Unlike this scenario for men, for women, the FDA has required products to show clinical effectiveness in trials. For instance, Estratest, a combination estrogen-testosterone product, was in use in the 1960s—approved for women with estrogen-resistant hot flushes, and used in practice for sexual dysfunction. After the FDA implemented its Drug Efficacy Study and Implementation regulation system after 2000, which required safety and efficacy trial(s) before drug approval, the manufacturer removed the drug from market when presented efficacy study data for the added testosterone in the drug were deemed inadequate.15

Dr. Streicher: We have yet another example of the disparity between the FDA approval processes for sexual function drugs for men versus women. Take Intrinsia as another example. It was a 300-mg testosterone patch that underwent clinical trials in women who were post-oophorectomy with HSDD. The patch had demonstrated efficacy with minimal adverse effects and no statistically significant dangerous effects. However, the FDA declined approval, citing “safety considerations” and requested longer-term clinical trials to evaluate potential cardiovascular or breast problems. Given that Intrinsia supplementation simply restored normal physiologic testosterone levels, and there was no such requirement in men who received supplementation post-orchiectomy, this requirement was nonsensical and unjustified.

Compounded formulations

Dr. Karram: Are compounding pharmacies appropriately regulated, and how can you be assured that the source of your testosterone is appropriate?

Dr. Glaser: Compounding pharmacies are regulated by the State Boards of Pharmacy, Drug Enforcement Agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, State Bureaus of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and Departments of Health (in some states).

Compounding is a highly regulated profession that is constantly under scrutiny by agencies, patients, and physicians. Any additional regulations could adversely impact the accessibility of patients to individually compounded medications including intravenous and oncology medications. Over the past 20 years, I have treated hundreds of patients with breast cancer with compounded vaginal testosterone (with or without estriol) and subcutaneous testosterone (with or without anastrozole), greatly improving quality of life in women suffering from severe symptoms. Without the availability of compounded medications, there would have been no or limited alternatives for adequate and much needed therapy. Notably, there have been no adverse events or safety-related issues in more than 20 years.

Regarding whether or not “the source of your testosterone is appropriate,” pharmacists can only use United States Pharmacopeia (USP) grades of testosterone. Testosterone used in compounding is required by the FDA to be of USP grade from an FDA registered and compliant facility. In addition, compounding support companies run additional USP tests to confirm their products meet USP standards prior to being delivered to individual compounding pharmacies.

Dr. Streicher: However, there potentially can be substantial variability between formulations and batches. Product purity can also be an issue. It is reassuring if the compounding pharmacy is compliant with purity of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Good Manufacturing Practice rules and guidelines that assure the minimum requirements to assure high quality and batch-to-batch consistency. I find it helpful to always work with the same pharmacy once you have established uniformity and reliability. If there is concern, it is appropriate to check a patient’s serum level 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the problem with some compounding pharmacies is that there may be incentives back and forth with the clinician to use a certain outlet, whereby the patient’s best interest may not be served. I do believe that there is a role for compounding pharmacies, however. We also use them because some women may have strange reactions or be allergic to the preservatives, formulating agents, or even lactose, in various pills and patches, gels, and creams.

Continue to: Testosterone for aging and cognition?...

Testosterone for aging and cognition?

Dr. Karram: Do you think that testosterone supplementation in the elderly can have a positive impact on aging, Alzheimer disease, and dementia?

Dr. Streicher: The jury is still out on the cognitive effects of postmenopausal androgen supplementation. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of testosterone to enhance cognitive performance, or to delay cognitive decline. I prescribe testosterone only to treat HSDD, but I do tell my patient that she may possibly also benefit in terms of cognitive function, musculoskeletal parameters, and well-being. Large RCTs are needed in those areas to justify prescribing for those benefits alone.

Dr. Simon: I would say this is the place for future development, but where there is very likely to be a benefit is on sarcopenia.

Dr. Glaser: There is some evidence that testosterone is neuroprotective.16 In my clinical practice I have seen “self-reported” memory issues improved on therapy, often returning toward the end of the testosterone implant cycle. Adequate amounts of bioavailable testosterone at the androgen receptor are critical for optimal health, immune function, and disease prevention.

Dr. Karram: In conclusion, this expert panel agrees that testosterone supplementation is beneficial for sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women, with also many other potential benefits that require further investigation. Route of administration preferred by Dr. Simon and Dr. Streicher is transdermal or a transvaginal cream. Dr. Glaser uses a subcutaneous pellet approach. Thank you all for an engaging and informative discussion. ●

Dr. Karram: How would you treat the following patient? She is 56, postmenopausal, and taking estrogen. She reports decreased libido, fatigue, lack of sleep, and lack of focus. Would you consider testosterone supplementation?

Dr. Simon: For her libido, yes. I would not give it to her for the fatigue if it were simply lack of sleep and without an associated medical condition. For her lack of focus, the testosterone could be beneficial. The central nervous system effects of testosterone are thought to be related to the conversion of testosterone to estrogen in the brain; if a person’s getting enough estrogen, they shouldn’t have lack of focus. Since some women may not want more estrogen, administering a little testosterone for libido also offers focus because it adds to the estrogen in the brain. If after giving her adequate amounts of testosterone her libido is not better in 8 weeks, it wasn’t a testosterone problem. If she does report improvement, however, I would keep her on the agent as long as she is healthy. But most 56-year-old women who already met the criteria for going on estrogen should be fine with testosterone.

If this same patient were not reporting low libido but did report lack of strength, energy, or well-being I also would say, “Sure, give testosterone a try.”

Dr. Glaser: I also would treat her with testosterone—with pellet implants. The dose would depend on her body weight. I usually start with an approximate dose of 1 mg of testosterone per pound of body weight. This amount of testosterone delivered continuously from the implant also supplies estradiol (via aromatization) locally at the cellular level.

I would treat her for as long as she chooses to continue testosterone therapy. There is no end- or stop-date where a person no longer benefits from therapy or adverse events occur. Testosterone does not increase the risk of breast cancer and it has a positive effect on many of the adverse signs and symptoms of aging, including mental and physical deterioration.

There are no currently US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for testosterone use in women. Its use by clinicians is through dose modification of FDA-approved therapies for men, or preparations created by compounding pharmacies. Recently, several professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), North American Menopause Society, International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health, and the International Society for Sexual Medicine, convened an expert panel to develop a global position statement on testosterone therapy for women.1 In this roundtable for OBG Management, moderated by Mickey Karram, MD, several experts discuss this position statement as well as the overall clinical advantages and drawbacks of using testosterone in women.

Testosterone indications

Mickey Karram, MD: For which indications do you prescribe testosterone supplementation in women?

Lauren Streicher, MD: I offer systemic testosterone therapy to postmenopausal women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and low serum testosterone levels, with one caveat—it is important that the patient’s reported distressing lack of libido is not explained by another condition or circumstance. Many women present reporting low libido but, on further questioning, it is typically revealed that dyspareunia precipitated their loss of interest in sex. It is normal to not want to do something that is painful. In addition, low libido can often be explained by chronic disease, such as diabetes, cancer, or clinical depression.

Some medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), frequently cause a decline in sexual interest. Finally, psychosocial and partner issues may be the culprit.

James Simon, MD, CCP, NCMP, IF: Much of the beneficial data for testosterone’s use is for sexual function in postmenopausal women.2 Female sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent among women during the postmenopause.3 Androgen levels progressively decrease throughout adult life in all women, so the postmenopausal additional lack of estrogen has a recognized effect on genitourinary health. There is evidence that the insufficiency of androgens as well as estrogens after menopause can lead to genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM).4

Testosterone also is used for increasing strength, lean muscle mass, bone mineral density, and sense of well-being.5

Rebecca Glaser, MD: I consider testosterone supplementation in my clinical practice in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women for symptoms of androgen/hormone deficiency, including diminished sense of well-being; dysphoric mood; anxiety; irritability; fatigue; decreased libido, sexual activity, or pleasure; vasomotor instability; bone loss; decreased muscle strength; insomnia; changes in cognition; memory loss; urinary symptoms; incontinence; vaginal atrophy and dryness; and joint and muscular pain. We also have shown through preliminary and short-term data and case studies that testosterone therapy has a potential beneficial effect on migraine headaches, as well as active breast cancers in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.6-10

Continue to: What is appropriate bloodwork?...

What is appropriate bloodwork?

Dr. Karram: Do you obtain blood work before initiating testosterone treatment? If so, what tests do you order and what testosterone levels are considered to be normal for premenopausal and postmenopausal women?

Dr. Streicher: Unlike estrogen, which is predictably low in a postmenopausal woman, serum testosterone (T) levels are highly variable because of the adrenal component. Ovarian testosterone production does not cease at the same time as estrogen production. So I do obtain total and free T levels, prior to initiating treatment. Having said that, it has been well established that T levels correlate poorly with level of sexual interest, and there is no specific blood level that can be used to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction. We all have patients who have nonexistent T levels and have a very healthy libido, and other women with sky-high levels who have no libido. But it is useful to know levels prior to initiating therapy to be able to monitor levels throughout treatment. Also, if levels are in the premenopausal physiologic range, not only is she unlikely to respond but she is also at risk for developing androgenic adverse effects, such as acne and hair growth. In general, a low free T level (even if it is in the normal postmenopausal range) in a clinical setting of HSDD supports supplementation.

The assessment and interpretation of T levels can be challenging, particularly as the majority of testosterone is protein-bound and biologically inactive. Free T levels (the biologically active testosterone) in many labs are unreliable and need to be calculated.

In addition to total and free T, I check levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), the protein that binds testosterone and renders it biologically inactive. If someone has high SHBG levels and is taking an oral estrogen, simply switching to a transdermal estrogen will result in decreased SHBG and increased free T.

Levels of total and free T vary from lab to lab, so it is best to be familiar with those ranges and then be consistent in which lab you choose.

Dr. Glaser: Although I personally do order blood work on most patients (T, free T, estradiol, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone), after 15 years of research and publishing data on testosterone implants, I do not believe that T levels are absolutely necessary or even beneficial in most cases. It rarely changes management in my patients.

As Lauren said, it is well known that T levels do not correlate with androgen deficiency symptoms or clinical conditions caused by androgen deficiency. If a patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency, a trial of testosterone therapy should be given.

T levels are not a valid marker of tissue exposure in women, reflecting less than 20% of total androgen activity. The major source of testosterone in pre and postmenopausal women is the local intracrine production of testosterone from the adrenal precursor steroids dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, which would not be reflected in T levels.

In our study involving 300 women, we found no relationship between baseline T levels, presenting symptoms, or response to therapy.6 Premenopausal and postmenopausal women had similar baseline T levels and similar response to therapy. Even women with baseline T levels in the mid-range responded to therapy.

Some of the most controversial topics in treating women with testosterone are related to dosing and T levels throughout therapy. Guideline authors often use the terms ‘physiologic dosing’ and ‘physiologic ranges’ when making recommendations for therapy. Although “physiologic” sounds appropriate/ scientific, these rigid opinions/recommendations are not evidence based. There are no data supporting the use of endogenous T ranges to guide dosing or monitor testosterone therapy.

The decision to initiate testosterone therapy is a clinical decision between the doctor and the patient based on the patient’s symptomatology, which is the therapeutic endpoint. Testosterone therapy must be done with adequate doses determined by clinical effect (benefits) versus side effects or adverse events (risks). T levels may be helpful, along with clinical evaluation when troubleshooting.

Utilizing data from thousands of patients, we have developed serum ranges for testosterone implants.11 Even so, no two patients are the same, nor do they respond to therapy the same. It is always a clinical decision.

Continue to: Dr. Simon...

Dr. Simon: In the recent global consensus statement on testosterone use,1 the experts were in agreement that “no cut-off blood level can be used for any measured circulating androgen to differentiate women with and without sexual dysfunction.” They give their recommendation a C, and I agree that testosterone supplementation, with specific dosage levels, are a clinical decision.

Before initiating testosterone therapy, it is recommended that liver function and fasting lipids are assessed, as liver disease and hyperlipidemia are contraindications to treatment. These levels should be monitored twice in the first year and annually thereafter while the patient is taking testosterone. Breast and pelvic examinations, mammography, and evaluation for abnormal bleeding should be performed as well as the blood tests.12 These recommendations are focused on safety not efficacy.

Administration route

Dr. Karram: How do you administer testosterone, and why?

Dr. Streicher: As there are no FDA approved testosterone products for women, clinicians must determine the dosage and route of delivery based on published clinical trials.

Dr. Glaser: I treat patients with subcutaneous pellet implants. The implants provide consistent and continuous delivery of therapeutic amounts of testosterone. There is a reason testosterone pellets have been used for more than 80 years and are more popular now than ever—they work. The insertion procedure is simple and takes about 2 minutes. The treatment is cost-effective, avoids first pass, has no adverse effect on the liver or clotting factors, and there is no transference. Decades of data support both the efficacy and safety of testosterone implants.6 However, testosterone implants are not regulated by the FDA and all patients are required to sign a consent informing them of off-label use, benefits, and risks of testosterone implant therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the consent is important, as there is no package labeling to warn of possible side effects.

Dr. Streicher: Oral testosterone therapy, because of its first pass through the liver and association with adverse lipid profiles with negative effects on high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, is not recommended. I prefer a transdermal approach. Pellets, implants, and injections have the potential to result in supraphysiologic blood concentrations. It must be emphasized that the goal of treatment is to approximate premenopausal physiologic levels. More is not better; excessive levels do not demonstrate a greater sexual response and are in fact more likely to have a negative impact due to androgenic side effects.

In most clinical trials, a 300 mg/d testosterone patch was effective, but these patches are not commercially available so I rely on transdermal gel from a compounding pharmacy. The typical dose needed to raise levels into the high to normal range for most women is 2.5 mg up to 5 mg per day of testosterone 1%, which translates to roughly 1 mL. Many pharmacies provide a dispenser, which allots the appropriate dose. Alternatively, I instruct the patient to place a dollop on her thigh (roughly in size of a single M&M candy).

I always tell my patients that the response is not immediate, typically taking 8 to 12 weeks for the effect to become clinically significant. I generally see a patient back 8 weeks after initiation of treatment to check T levels and evaluate response.

Dr. Simon: There are some data demonstrating that intravaginal testosterone can be a potential treatment for GSM. Intravaginal testosterone coupled with aromatase inhibitor therapy used for breast cancer treatment resulted in supraphysiologic T levels and reportedly improved vaginal maturation index and reduced dyspareunia. More study is needed.13

Dr. Streicher: Agreed. The lower third of the vagina and the vestibule is rich in testosterone receptors. Like Dr. Simon, in some cases of vaginal atrophy I prescribe a compounded local vaginal testosterone.

Continue to: Testosterone and premenopausal women...

Testosterone and premenopausal women

Dr. Karram: Is there a role for testosterone supplementation in premenopausal women with normal estrogen production?

Dr. Glaser: Yes. In fact, in our study, more than one-third of the patients were premenopausal, which makes sense.6 There is a marked decline of T levels and the adrenal precursor steroids (DHEA and androstenedione) in women between the ages of 20–30 years and around age 50. As we said, symptoms of androgen deficiency often occur prior to menopause and are not related to estrogen levels. In our study, testosterone implant therapy relieved symptoms of hormone (androgen) deficiency, including vasomotor symptoms, sleep problems, depressive mood, irritability, anxiety, physical and mental exhaustion (fatigue, memory issues), sexual problems, bladder problems (incontinence, frequency), vaginal dryness, and joint and muscular pain. Premenopausal and postmenopausal patients reported similar hormone deficiency symptoms. Premenopausal women did report a higher incidence of psychological complaints (depressive mood, anxiety, and irritability), while postmenopausal women reported more hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and urologic symptoms. Both groups demonstrated similar improvement in symptoms.

In addition, we have seen relief of severe migraine headache in premenopausal (as well as postmenopausal) women treated with testosterone implant therapy.6,7

Dr. Streicher: The goal of testosterone supplementation is to approximate physiological testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women. While testosterone may improve well-being and sexual function in premenopausal women, the data are limited and really inconclusive. More study is needed given that there is likely a wide therapeutic range with many variables. Having said that, there are some data that indicate that testosterone in premenopausal women may enhance general sense of well-being.14

Why is there no FDA-approved agent?

Dr. Karram: Why do you think the FDA has been reluctant to approve a testosterone agent for women?

Dr. Simon: Three potential testosterone drugs for use in women have been unsuccessfully brought to market after the FDA did not approve them. There are 31 approved products for men, each of which were approved because they safely restored normal testosterone concentrations in men with reduced levels and an associated medical condition. Unlike this scenario for men, for women, the FDA has required products to show clinical effectiveness in trials. For instance, Estratest, a combination estrogen-testosterone product, was in use in the 1960s—approved for women with estrogen-resistant hot flushes, and used in practice for sexual dysfunction. After the FDA implemented its Drug Efficacy Study and Implementation regulation system after 2000, which required safety and efficacy trial(s) before drug approval, the manufacturer removed the drug from market when presented efficacy study data for the added testosterone in the drug were deemed inadequate.15

Dr. Streicher: We have yet another example of the disparity between the FDA approval processes for sexual function drugs for men versus women. Take Intrinsia as another example. It was a 300-mg testosterone patch that underwent clinical trials in women who were post-oophorectomy with HSDD. The patch had demonstrated efficacy with minimal adverse effects and no statistically significant dangerous effects. However, the FDA declined approval, citing “safety considerations” and requested longer-term clinical trials to evaluate potential cardiovascular or breast problems. Given that Intrinsia supplementation simply restored normal physiologic testosterone levels, and there was no such requirement in men who received supplementation post-orchiectomy, this requirement was nonsensical and unjustified.

Compounded formulations

Dr. Karram: Are compounding pharmacies appropriately regulated, and how can you be assured that the source of your testosterone is appropriate?

Dr. Glaser: Compounding pharmacies are regulated by the State Boards of Pharmacy, Drug Enforcement Agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, State Bureaus of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and Departments of Health (in some states).

Compounding is a highly regulated profession that is constantly under scrutiny by agencies, patients, and physicians. Any additional regulations could adversely impact the accessibility of patients to individually compounded medications including intravenous and oncology medications. Over the past 20 years, I have treated hundreds of patients with breast cancer with compounded vaginal testosterone (with or without estriol) and subcutaneous testosterone (with or without anastrozole), greatly improving quality of life in women suffering from severe symptoms. Without the availability of compounded medications, there would have been no or limited alternatives for adequate and much needed therapy. Notably, there have been no adverse events or safety-related issues in more than 20 years.

Regarding whether or not “the source of your testosterone is appropriate,” pharmacists can only use United States Pharmacopeia (USP) grades of testosterone. Testosterone used in compounding is required by the FDA to be of USP grade from an FDA registered and compliant facility. In addition, compounding support companies run additional USP tests to confirm their products meet USP standards prior to being delivered to individual compounding pharmacies.

Dr. Streicher: However, there potentially can be substantial variability between formulations and batches. Product purity can also be an issue. It is reassuring if the compounding pharmacy is compliant with purity of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Good Manufacturing Practice rules and guidelines that assure the minimum requirements to assure high quality and batch-to-batch consistency. I find it helpful to always work with the same pharmacy once you have established uniformity and reliability. If there is concern, it is appropriate to check a patient’s serum level 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Dr. Simon: I think the problem with some compounding pharmacies is that there may be incentives back and forth with the clinician to use a certain outlet, whereby the patient’s best interest may not be served. I do believe that there is a role for compounding pharmacies, however. We also use them because some women may have strange reactions or be allergic to the preservatives, formulating agents, or even lactose, in various pills and patches, gels, and creams.

Continue to: Testosterone for aging and cognition?...

Testosterone for aging and cognition?

Dr. Karram: Do you think that testosterone supplementation in the elderly can have a positive impact on aging, Alzheimer disease, and dementia?

Dr. Streicher: The jury is still out on the cognitive effects of postmenopausal androgen supplementation. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of testosterone to enhance cognitive performance, or to delay cognitive decline. I prescribe testosterone only to treat HSDD, but I do tell my patient that she may possibly also benefit in terms of cognitive function, musculoskeletal parameters, and well-being. Large RCTs are needed in those areas to justify prescribing for those benefits alone.

Dr. Simon: I would say this is the place for future development, but where there is very likely to be a benefit is on sarcopenia.

Dr. Glaser: There is some evidence that testosterone is neuroprotective.16 In my clinical practice I have seen “self-reported” memory issues improved on therapy, often returning toward the end of the testosterone implant cycle. Adequate amounts of bioavailable testosterone at the androgen receptor are critical for optimal health, immune function, and disease prevention.

Dr. Karram: In conclusion, this expert panel agrees that testosterone supplementation is beneficial for sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women, with also many other potential benefits that require further investigation. Route of administration preferred by Dr. Simon and Dr. Streicher is transdermal or a transvaginal cream. Dr. Glaser uses a subcutaneous pellet approach. Thank you all for an engaging and informative discussion. ●

Dr. Karram: How would you treat the following patient? She is 56, postmenopausal, and taking estrogen. She reports decreased libido, fatigue, lack of sleep, and lack of focus. Would you consider testosterone supplementation?

Dr. Simon: For her libido, yes. I would not give it to her for the fatigue if it were simply lack of sleep and without an associated medical condition. For her lack of focus, the testosterone could be beneficial. The central nervous system effects of testosterone are thought to be related to the conversion of testosterone to estrogen in the brain; if a person’s getting enough estrogen, they shouldn’t have lack of focus. Since some women may not want more estrogen, administering a little testosterone for libido also offers focus because it adds to the estrogen in the brain. If after giving her adequate amounts of testosterone her libido is not better in 8 weeks, it wasn’t a testosterone problem. If she does report improvement, however, I would keep her on the agent as long as she is healthy. But most 56-year-old women who already met the criteria for going on estrogen should be fine with testosterone.

If this same patient were not reporting low libido but did report lack of strength, energy, or well-being I also would say, “Sure, give testosterone a try.”

Dr. Glaser: I also would treat her with testosterone—with pellet implants. The dose would depend on her body weight. I usually start with an approximate dose of 1 mg of testosterone per pound of body weight. This amount of testosterone delivered continuously from the implant also supplies estradiol (via aromatization) locally at the cellular level.

I would treat her for as long as she chooses to continue testosterone therapy. There is no end- or stop-date where a person no longer benefits from therapy or adverse events occur. Testosterone does not increase the risk of breast cancer and it has a positive effect on many of the adverse signs and symptoms of aging, including mental and physical deterioration.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women. Climacteric. 2019;22:429-434.

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Green S, et al. Safety and efficacy of testosterone for women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trial data. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;S2213-8587:30189-30195.

- Simon JA, Davis SR, Althof SE, et al. Sexual well-being after menopause: an International Menopause Society White Paper. Climacteric. 2018;21:415-427.

- Traish AM, Vignozzi L, Simon JA, et al. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:558-571.

- Panay N. British Menopause Society tools for clinicians: testosterone replacement in menopause. Post Reprod Health. 2019;25:40-42.

- Glaser R, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Beneficial effects of testosterone therapy in women measured by the validated Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Maturitas. 2011;68:355-361.

- Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C, Trimble N, et al. Testosterone pellet implants and migraine headaches: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2012;71:385-388.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Efficacy of subcutaneous testosterone on menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):109-109.

- Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C. Rapid response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant intramammary testosterone-anastrozole therapy: neoadjuvant hormone therapy in breast cancer. Menopause. 2014;21:673.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Subcutaneous testosterone-letrozole therapy before and concurrent with neoadjuvant breast chemotherapy: clinical response and therapeutic implications. Menopause. 2017;24:859-864.

- Glaser R, Kalantaridou S, Dimitrakakis C, et al. Testosterone implants in women: pharmacological dosing for a physiologic effect. Maturitas. 2013;74:179-184.

- International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. In press.

- Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, et al. The role of androgens in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM): International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Menopause. 2018;25:837-847.

- Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, et al. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves well-being, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:390-398.

- Simon JA, Kapner MD. The saga of testosterone for menopausal women at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). J Sex Med. 2020;17:826-829.

- Davis SR, Wahlin-Jacobsen S. Testosterone in women—the clinical significance. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3: 980-992.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women. Climacteric. 2019;22:429-434.

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Green S, et al. Safety and efficacy of testosterone for women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trial data. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;S2213-8587:30189-30195.

- Simon JA, Davis SR, Althof SE, et al. Sexual well-being after menopause: an International Menopause Society White Paper. Climacteric. 2018;21:415-427.

- Traish AM, Vignozzi L, Simon JA, et al. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:558-571.

- Panay N. British Menopause Society tools for clinicians: testosterone replacement in menopause. Post Reprod Health. 2019;25:40-42.

- Glaser R, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Beneficial effects of testosterone therapy in women measured by the validated Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Maturitas. 2011;68:355-361.

- Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C, Trimble N, et al. Testosterone pellet implants and migraine headaches: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2012;71:385-388.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Efficacy of subcutaneous testosterone on menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):109-109.

- Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C. Rapid response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant intramammary testosterone-anastrozole therapy: neoadjuvant hormone therapy in breast cancer. Menopause. 2014;21:673.

- Glaser RL, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Subcutaneous testosterone-letrozole therapy before and concurrent with neoadjuvant breast chemotherapy: clinical response and therapeutic implications. Menopause. 2017;24:859-864.

- Glaser R, Kalantaridou S, Dimitrakakis C, et al. Testosterone implants in women: pharmacological dosing for a physiologic effect. Maturitas. 2013;74:179-184.

- International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. In press.

- Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, et al. The role of androgens in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM): International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Menopause. 2018;25:837-847.

- Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, et al. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves well-being, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:390-398.

- Simon JA, Kapner MD. The saga of testosterone for menopausal women at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). J Sex Med. 2020;17:826-829.

- Davis SR, Wahlin-Jacobsen S. Testosterone in women—the clinical significance. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3: 980-992.

For which patients is maternal oxygen supplementation of value?

Raghuraman N, Temming LA, Doering MM, et al. Maternal oxygen supplementation compared with room air for intrauterine resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. January 4, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5351.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Maternal oxygen supplementation is widely used in labor for nonreassuring fetal heart rate (FHR) tracings, although its efficacy is uncertain for preventing fetal acidosis, operative intervention, or sequelae of neonatal encephalopathy. Recently, Raghuraman and colleagues reported the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 16 randomized controlled trials. A total of 1,078 women were included in the oxygen group and 974 in the room air group. The primary outcome was umbilical artery pH; 14 trials reported on this outcome.

After analyzing the pooled and stratified results of the effect of maternal oxygen supplementation versus room air on umbilical artery gas measures, the authors concluded that peripartum oxygen supplementation is not associated with clinically relevant improvement in umbilical artery pH. They acknowledged, however, that the published studies were heterogeneous, lacked data on the association of oxygen supplementation with neonatal outcome, and did not assess oxygen use for abnormal FHR tracings, except for one trial with category II FHR tracings.

Effects of O2 supplementation

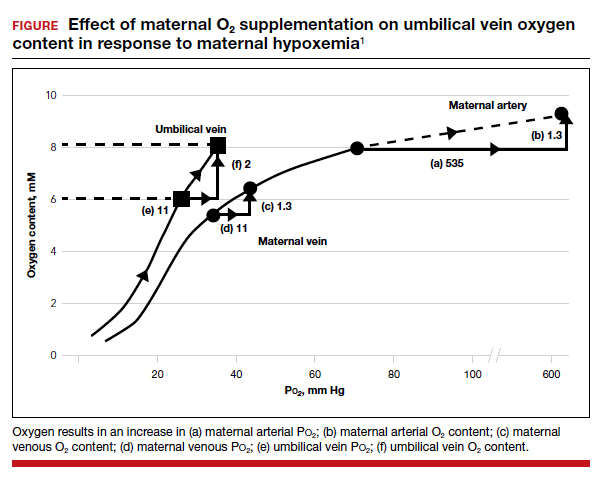

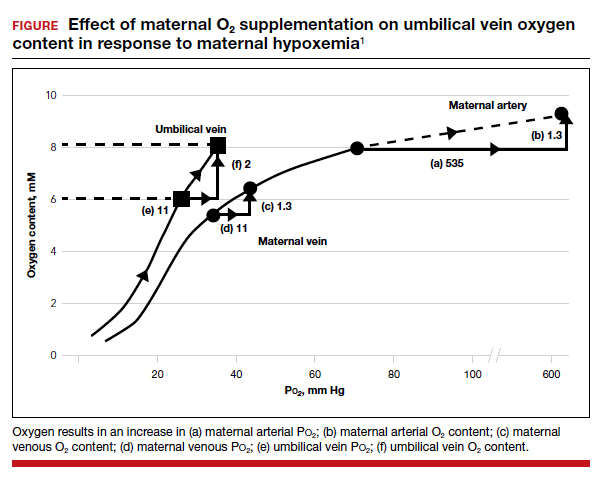

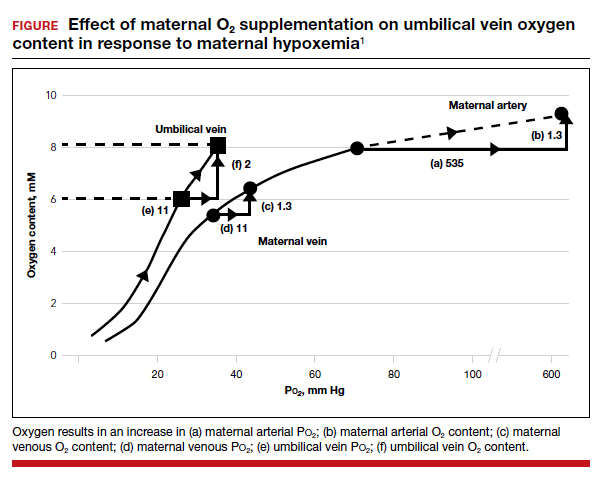

As maternal arterial hemoglobin is nearly saturated under normal conditions, maternal hyperoxia produces only modest increases in umbilical vein P

Fetal hypoxemia and acidosis can result from an interruption or an impairment of the mother-to-placenta-to-fetus oxygen pathway. With some interruptions of the oxygen pathway, such as placental abruption and complete cord occlusion–induced bradycardia, there would be less impact of maternal hyperoxia. By contrast, with other oxygen pathway impairments, such as reduced oxygen transfer with placental insufficiency, maternal hyperoxia can be of greater value by increasing maternal uterine artery and vein P

Continue to: Circumstances that may benefit from O2 supplementation...

Circumstances that may benefit from O2 supplementation

Late FHR decelerations reflect impairment of oxygen transfer and thus represent the heart rate pattern that is most likely to benefit from maternal hyperoxia. However, recurrent late decelerations occur in less than 2% of low-risk patients in labor,3 and severe levels of acidosis (umbilical artery pH <7.0 or base deficit [BD] ≥12 mmol/L) occur in only 1% to 2% of near-term or term deliveries.4,5

Variable decelerations also reflect fetal hypoxia and are much more common than late decelerations, so they also may benefit from O2 supplementation. Regardless, O2 supplementation should be seen only as a temporizing strategy while other resuscitative actions are initiated, including preparation for operative delivery, if indicated.

In a prior study by Raghuraman and colleagues (1 of only 4 studies that met selection criteria of oxygen supplementation for patients in labor), newborns of patients not receiving oxygen demonstrated 95% confidence limits of umbilical artery pH (7.24–7.28) and BD (2.9–4.3) well within the normal range.6 Thus, the low prevalence of cases in which a benefit might be anticipated and the low incidence of severe acidosis challenges the design of prospective studies to detect statistically and clinically significant changes in blood gas measures and newborn outcomes.