User login

Baby’s Rash Causes Family Feud

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Can You Put Your Finger on the Diagnosis?

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

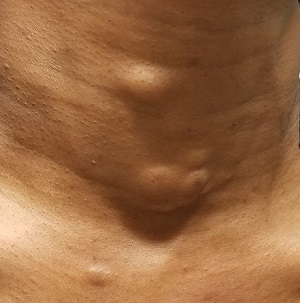

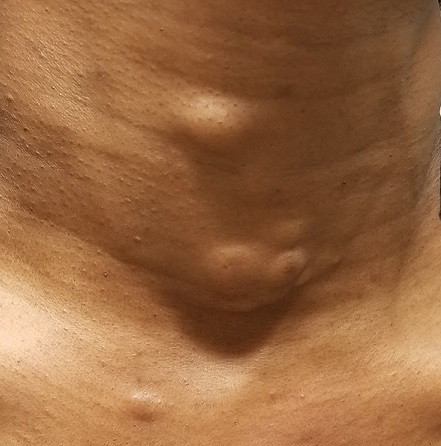

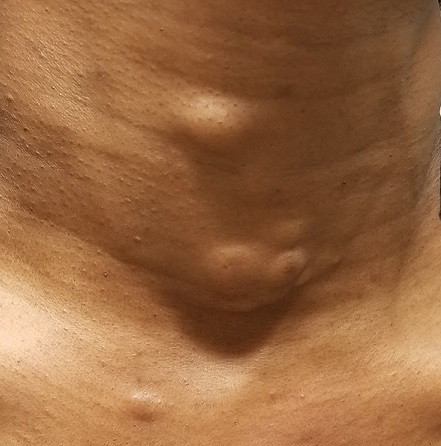

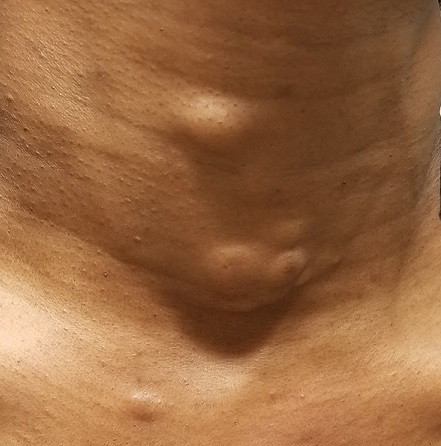

She Needs A-cyst-ance

This woman, now 44, first developed subcutaneous “bumps” on her neck, arms, and chest at puberty. They were initially diagnosed as acne, but treatment for that condition failed to help.

Later, she consulted a dermatologist, who suggested they were cysts and actually removed one to send for pathologic examination. The report indicated “a type of cyst,” the name of which the patient has long since forgotten.

Over the years, she has developed additional lesions, which are not only unsightly but also painful at times. Although the patient is not in distress, she is upset.

The patient has type IV skin and is of African-American ancestry. Further history-taking reveals that she is reasonably healthy, with no other skin problems. She does report that the presenting complaint “runs in the family,” on her father’s side.

EXAMINATION

The lesions—subcutaneous, doughy, cystic-feeling papules and nodules—are widely distributed on the patient’s anterior neck, arms, and chest. They range in size from 5 mm to 3 cm. None are inflamed, and no puncta can be seen on their surfaces. Palpation provokes no reaction of pain or discomfort.

With the patient’s permission, she is anesthetized and one lesion is removed. The sample clearly establishes a cystic nature, although the contents are neither cheesy nor grumous as would be seen with an ordinary epidermal cyst. Rather, they are an oily, odorless, thick liquid surrounded by an organized cyst wall. This is removed as well and sent for pathologic examination.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the lesions to be steatocystoma—in this case, part of an autosomal dominantly inherited condition called steatocystoma multiplex (SM). When these manifest as solitary lesions, they are known as steatocystoma simplex—a true sebaceous cyst, quite different from the common epidermal cyst that contains cheesy, odoriferous material and is frequently misnamed “sebaceous cyst.”

Steatocystoma can develop spontaneously, without any genetic predisposition. SM, however, is quite unusual (if not rare) and results from a defect in keratin 17 that allows the accumulation of sebum at the base of the follicle. It has no other pathologic implication.

However, in a case such as this, SM presents a real problem, because the only effective treatment is complete excision. This not only leaves a scar, but also, in those with skin of color, has the potential to produce hypertrophic scarring or even keloid formation. Worse, in many cases, the patient keeps developing cysts in new locations.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Steatocystoma multiplex (SM) is an autosomal dominant condition in which the patient, usually at puberty, develops sebum-filled cysts.

- These cysts can occur as solitary lesions (steatocystoma simplex) but more often manifest in multiples on the neck, face, chest, and arms.

- SM cysts are full of clear or yellowish sebum, unlike common epidermal cysts, which are filled with cheesy, often odoriferous material.

- The only effective treatment for SM cysts is complete excision.

This woman, now 44, first developed subcutaneous “bumps” on her neck, arms, and chest at puberty. They were initially diagnosed as acne, but treatment for that condition failed to help.

Later, she consulted a dermatologist, who suggested they were cysts and actually removed one to send for pathologic examination. The report indicated “a type of cyst,” the name of which the patient has long since forgotten.

Over the years, she has developed additional lesions, which are not only unsightly but also painful at times. Although the patient is not in distress, she is upset.

The patient has type IV skin and is of African-American ancestry. Further history-taking reveals that she is reasonably healthy, with no other skin problems. She does report that the presenting complaint “runs in the family,” on her father’s side.

EXAMINATION

The lesions—subcutaneous, doughy, cystic-feeling papules and nodules—are widely distributed on the patient’s anterior neck, arms, and chest. They range in size from 5 mm to 3 cm. None are inflamed, and no puncta can be seen on their surfaces. Palpation provokes no reaction of pain or discomfort.

With the patient’s permission, she is anesthetized and one lesion is removed. The sample clearly establishes a cystic nature, although the contents are neither cheesy nor grumous as would be seen with an ordinary epidermal cyst. Rather, they are an oily, odorless, thick liquid surrounded by an organized cyst wall. This is removed as well and sent for pathologic examination.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the lesions to be steatocystoma—in this case, part of an autosomal dominantly inherited condition called steatocystoma multiplex (SM). When these manifest as solitary lesions, they are known as steatocystoma simplex—a true sebaceous cyst, quite different from the common epidermal cyst that contains cheesy, odoriferous material and is frequently misnamed “sebaceous cyst.”

Steatocystoma can develop spontaneously, without any genetic predisposition. SM, however, is quite unusual (if not rare) and results from a defect in keratin 17 that allows the accumulation of sebum at the base of the follicle. It has no other pathologic implication.

However, in a case such as this, SM presents a real problem, because the only effective treatment is complete excision. This not only leaves a scar, but also, in those with skin of color, has the potential to produce hypertrophic scarring or even keloid formation. Worse, in many cases, the patient keeps developing cysts in new locations.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Steatocystoma multiplex (SM) is an autosomal dominant condition in which the patient, usually at puberty, develops sebum-filled cysts.

- These cysts can occur as solitary lesions (steatocystoma simplex) but more often manifest in multiples on the neck, face, chest, and arms.

- SM cysts are full of clear or yellowish sebum, unlike common epidermal cysts, which are filled with cheesy, often odoriferous material.

- The only effective treatment for SM cysts is complete excision.

This woman, now 44, first developed subcutaneous “bumps” on her neck, arms, and chest at puberty. They were initially diagnosed as acne, but treatment for that condition failed to help.

Later, she consulted a dermatologist, who suggested they were cysts and actually removed one to send for pathologic examination. The report indicated “a type of cyst,” the name of which the patient has long since forgotten.

Over the years, she has developed additional lesions, which are not only unsightly but also painful at times. Although the patient is not in distress, she is upset.

The patient has type IV skin and is of African-American ancestry. Further history-taking reveals that she is reasonably healthy, with no other skin problems. She does report that the presenting complaint “runs in the family,” on her father’s side.

EXAMINATION

The lesions—subcutaneous, doughy, cystic-feeling papules and nodules—are widely distributed on the patient’s anterior neck, arms, and chest. They range in size from 5 mm to 3 cm. None are inflamed, and no puncta can be seen on their surfaces. Palpation provokes no reaction of pain or discomfort.

With the patient’s permission, she is anesthetized and one lesion is removed. The sample clearly establishes a cystic nature, although the contents are neither cheesy nor grumous as would be seen with an ordinary epidermal cyst. Rather, they are an oily, odorless, thick liquid surrounded by an organized cyst wall. This is removed as well and sent for pathologic examination.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the lesions to be steatocystoma—in this case, part of an autosomal dominantly inherited condition called steatocystoma multiplex (SM). When these manifest as solitary lesions, they are known as steatocystoma simplex—a true sebaceous cyst, quite different from the common epidermal cyst that contains cheesy, odoriferous material and is frequently misnamed “sebaceous cyst.”

Steatocystoma can develop spontaneously, without any genetic predisposition. SM, however, is quite unusual (if not rare) and results from a defect in keratin 17 that allows the accumulation of sebum at the base of the follicle. It has no other pathologic implication.

However, in a case such as this, SM presents a real problem, because the only effective treatment is complete excision. This not only leaves a scar, but also, in those with skin of color, has the potential to produce hypertrophic scarring or even keloid formation. Worse, in many cases, the patient keeps developing cysts in new locations.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Steatocystoma multiplex (SM) is an autosomal dominant condition in which the patient, usually at puberty, develops sebum-filled cysts.

- These cysts can occur as solitary lesions (steatocystoma simplex) but more often manifest in multiples on the neck, face, chest, and arms.

- SM cysts are full of clear or yellowish sebum, unlike common epidermal cysts, which are filled with cheesy, often odoriferous material.

- The only effective treatment for SM cysts is complete excision.

When the Right Medication Has the Wrong Effect

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

Don’t Just Look at the Lesion

A 52-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of an irritated lesion on the posterolateral aspect of his neck. It’s been there for years, waxing and waning but always being irritated by his shirt collar or seat belt.

He has shown the lesion to his primary care provider on several occasions. Various topical preparations, including steroid and antifungal creams, have been prescribed—to no avail.

The patient owns a landscaping business. He has worked outdoors since he was in his teens and acknowledges that in his younger years, he was not careful about sun protection. For the past 20 years or so, however, he has worn a wide-brimmed hat and long-sleeved shirt while working.

His health is good in all other respects.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a pink, scaly, 2-cm ovoid patch on the left side of the patient’s neck. Several areas of scabbing are seen within the bounds of the lesion, the margins of which are very well defined.

There is much evidence of sun damage on his neck and arms, with prominent pilosebaceous units and rhomboidal lining of the neck skin. Elsewhere, on sun-exposed skin, there are numerous actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and poikilodermatous changes.

The lesion is biopsied by shave technique and the sample submitted to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the impression of superficial squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) with focal areas of invasion.

One thinks of skin cancer as being “a thing,” a papule or nodule, and that’s usually true. But there are several types of skin cancer that manifest as a fixed rash—meaning it stays in the same place year after year, unlike other rashes (eg, psoriasis, eczema, or fungal infection). Common examples, besides superficial SCC (also known as Bowen disease), include superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Paget disease (mammary and extramammary), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and even local recurrence of breast cancer.

This patient’s occupation and history of (abundantly evident) sun damage put him at risk for a sun-caused skin cancer. As so often happens, the problem was initially misdiagnosed by a provider who was only looking at the lesion instead of factoring in the context in which it appeared. Who has the lesion is almost as important as the lesion itself.

Without a biopsy, Bowen disease is often indistinguishable from superficial BCC; the latter can take on a variety of appearances, from scar-like (cicatricial) to pigmented (especially in patients with darker skin) to the most common, nodular/noduloulcerative. Another item in the differential is discoid lupus erythematosus, particularly when the lesion manifests in a highly sun-exposed area.

Treatment of this patient’s lesion entailed full excision with 3-mm margins. This option was chosen based on the focal areas of invasion and theoretical potential for metastasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease) presents as a red, scaly rash with a rounded, well-demarcated border, almost always on skin directly overexposed to the sun.

- These cancers grow slowly, are fixed in location, never heal, and—given enough time—often become focally invasive.

- They will often be misdiagnosed as fungal infection, psoriasis, or eczema, because of the misperception that skin cancers are always papular or nodular.

- A history of sun exposure and resulting markers of dermatoheliosis serve to corroborate the putative diagnosis.

A 52-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of an irritated lesion on the posterolateral aspect of his neck. It’s been there for years, waxing and waning but always being irritated by his shirt collar or seat belt.

He has shown the lesion to his primary care provider on several occasions. Various topical preparations, including steroid and antifungal creams, have been prescribed—to no avail.

The patient owns a landscaping business. He has worked outdoors since he was in his teens and acknowledges that in his younger years, he was not careful about sun protection. For the past 20 years or so, however, he has worn a wide-brimmed hat and long-sleeved shirt while working.

His health is good in all other respects.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a pink, scaly, 2-cm ovoid patch on the left side of the patient’s neck. Several areas of scabbing are seen within the bounds of the lesion, the margins of which are very well defined.

There is much evidence of sun damage on his neck and arms, with prominent pilosebaceous units and rhomboidal lining of the neck skin. Elsewhere, on sun-exposed skin, there are numerous actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and poikilodermatous changes.

The lesion is biopsied by shave technique and the sample submitted to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the impression of superficial squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) with focal areas of invasion.

One thinks of skin cancer as being “a thing,” a papule or nodule, and that’s usually true. But there are several types of skin cancer that manifest as a fixed rash—meaning it stays in the same place year after year, unlike other rashes (eg, psoriasis, eczema, or fungal infection). Common examples, besides superficial SCC (also known as Bowen disease), include superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Paget disease (mammary and extramammary), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and even local recurrence of breast cancer.

This patient’s occupation and history of (abundantly evident) sun damage put him at risk for a sun-caused skin cancer. As so often happens, the problem was initially misdiagnosed by a provider who was only looking at the lesion instead of factoring in the context in which it appeared. Who has the lesion is almost as important as the lesion itself.

Without a biopsy, Bowen disease is often indistinguishable from superficial BCC; the latter can take on a variety of appearances, from scar-like (cicatricial) to pigmented (especially in patients with darker skin) to the most common, nodular/noduloulcerative. Another item in the differential is discoid lupus erythematosus, particularly when the lesion manifests in a highly sun-exposed area.

Treatment of this patient’s lesion entailed full excision with 3-mm margins. This option was chosen based on the focal areas of invasion and theoretical potential for metastasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease) presents as a red, scaly rash with a rounded, well-demarcated border, almost always on skin directly overexposed to the sun.

- These cancers grow slowly, are fixed in location, never heal, and—given enough time—often become focally invasive.

- They will often be misdiagnosed as fungal infection, psoriasis, or eczema, because of the misperception that skin cancers are always papular or nodular.

- A history of sun exposure and resulting markers of dermatoheliosis serve to corroborate the putative diagnosis.

A 52-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of an irritated lesion on the posterolateral aspect of his neck. It’s been there for years, waxing and waning but always being irritated by his shirt collar or seat belt.

He has shown the lesion to his primary care provider on several occasions. Various topical preparations, including steroid and antifungal creams, have been prescribed—to no avail.

The patient owns a landscaping business. He has worked outdoors since he was in his teens and acknowledges that in his younger years, he was not careful about sun protection. For the past 20 years or so, however, he has worn a wide-brimmed hat and long-sleeved shirt while working.

His health is good in all other respects.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a pink, scaly, 2-cm ovoid patch on the left side of the patient’s neck. Several areas of scabbing are seen within the bounds of the lesion, the margins of which are very well defined.

There is much evidence of sun damage on his neck and arms, with prominent pilosebaceous units and rhomboidal lining of the neck skin. Elsewhere, on sun-exposed skin, there are numerous actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and poikilodermatous changes.

The lesion is biopsied by shave technique and the sample submitted to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the impression of superficial squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) with focal areas of invasion.

One thinks of skin cancer as being “a thing,” a papule or nodule, and that’s usually true. But there are several types of skin cancer that manifest as a fixed rash—meaning it stays in the same place year after year, unlike other rashes (eg, psoriasis, eczema, or fungal infection). Common examples, besides superficial SCC (also known as Bowen disease), include superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Paget disease (mammary and extramammary), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and even local recurrence of breast cancer.

This patient’s occupation and history of (abundantly evident) sun damage put him at risk for a sun-caused skin cancer. As so often happens, the problem was initially misdiagnosed by a provider who was only looking at the lesion instead of factoring in the context in which it appeared. Who has the lesion is almost as important as the lesion itself.

Without a biopsy, Bowen disease is often indistinguishable from superficial BCC; the latter can take on a variety of appearances, from scar-like (cicatricial) to pigmented (especially in patients with darker skin) to the most common, nodular/noduloulcerative. Another item in the differential is discoid lupus erythematosus, particularly when the lesion manifests in a highly sun-exposed area.

Treatment of this patient’s lesion entailed full excision with 3-mm margins. This option was chosen based on the focal areas of invasion and theoretical potential for metastasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease) presents as a red, scaly rash with a rounded, well-demarcated border, almost always on skin directly overexposed to the sun.

- These cancers grow slowly, are fixed in location, never heal, and—given enough time—often become focally invasive.

- They will often be misdiagnosed as fungal infection, psoriasis, or eczema, because of the misperception that skin cancers are always papular or nodular.

- A history of sun exposure and resulting markers of dermatoheliosis serve to corroborate the putative diagnosis.

A Literally Massive Problem

A 60-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a longstanding complaint of a tender, irritated mass hanging from her lower abdomen. The patient says it started as a large fold in her lower abdomen but over the years has grown and become more pendulous. It is now large enough to interfere with normal activity, including walking.

Numerous providers, dermatologists included, have rendered diagnoses—most recently, hidradenitis suppurativa. The antibiotics prescribed for that diagnosis have not helped, however. Similarly, cultures performed on samples from draining sores on the mass’s posterior have failed to illuminate the situation, showing only mixed normal flora.

The patient’s primary care provider referred her to surgery for consideration of removal, or at least reduction, of the mass. The surgeon offered a presumptive diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the pannus and agreed to perform the surgery. But the patient’s primary care provider requested a second opinion from dermatology.

EXAMINATION

The edematous, pendulous mass is the size of a soccer ball and hangs down from its abdominal base. When the patient stands, the mass stretches almost to the level of her knees. The anterior surface is edematous but otherwise normal in appearance. The intertriginous surfaces of the lesion look entirely different, with multiple small, draining puncta and a few open comedones.

The body of the mass is quite indurated but is neither hot nor tender. There are no comedones or cysts in other intertriginous locations, as might be seen in hidradenitis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case involves a rare entity: vast lymphedema of the pannus leading to the formation of a pendulous mass so large that it filled the space between the patient’s legs, causing pain and discomfort. These findings are analogous to those seen in advanced venous insufficiency. Both manifestations share a name: elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. (Neither has anything to do with the more notorious cases of filarial elephantiasis seen in tropical locations.)

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the lower extremities involves striking skin changes: edema, along with extreme thickening, papularity, and roughness of the skin. These typically manifest downward from just below the knee. The condition represents the effects of late-stage chronic venous insufficiency, often worsened by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. Other causes of dependent lymphedema, such as congestive heart failure, can also contribute to the problem.

This same pathophysiologic process can affect other areas as well—including the pannus, as seen in this case. Since I had only ever encountered this problem in legs, I did a literature search. I found several references, all of which indicated that surgical removal (panniculectomy) was the best treatment. I could not find any information on the success rate of this surgery, but I did refer the patient back to the surgeon, who had made the correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a consequence of uncontrolled venous insufficiency that commonly manifests on lower extremities.

- ENV is a distinctly rare (though not unknown) problem when areas other than legs are affected.

- This patient’s condition is, in my opinion, beyond the reach of medical treatment. But in milder cases, approaches such as weight loss and use of diuretics have been tried with mixed success.

- The best treatment appears to be surgical removal, which is not without potential complications: risk for infection, pain, prolonged recovery time, and wound dehiscence; these issues were discussed thoroughly with the case patient.

A 60-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a longstanding complaint of a tender, irritated mass hanging from her lower abdomen. The patient says it started as a large fold in her lower abdomen but over the years has grown and become more pendulous. It is now large enough to interfere with normal activity, including walking.

Numerous providers, dermatologists included, have rendered diagnoses—most recently, hidradenitis suppurativa. The antibiotics prescribed for that diagnosis have not helped, however. Similarly, cultures performed on samples from draining sores on the mass’s posterior have failed to illuminate the situation, showing only mixed normal flora.

The patient’s primary care provider referred her to surgery for consideration of removal, or at least reduction, of the mass. The surgeon offered a presumptive diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the pannus and agreed to perform the surgery. But the patient’s primary care provider requested a second opinion from dermatology.

EXAMINATION

The edematous, pendulous mass is the size of a soccer ball and hangs down from its abdominal base. When the patient stands, the mass stretches almost to the level of her knees. The anterior surface is edematous but otherwise normal in appearance. The intertriginous surfaces of the lesion look entirely different, with multiple small, draining puncta and a few open comedones.

The body of the mass is quite indurated but is neither hot nor tender. There are no comedones or cysts in other intertriginous locations, as might be seen in hidradenitis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case involves a rare entity: vast lymphedema of the pannus leading to the formation of a pendulous mass so large that it filled the space between the patient’s legs, causing pain and discomfort. These findings are analogous to those seen in advanced venous insufficiency. Both manifestations share a name: elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. (Neither has anything to do with the more notorious cases of filarial elephantiasis seen in tropical locations.)

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the lower extremities involves striking skin changes: edema, along with extreme thickening, papularity, and roughness of the skin. These typically manifest downward from just below the knee. The condition represents the effects of late-stage chronic venous insufficiency, often worsened by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. Other causes of dependent lymphedema, such as congestive heart failure, can also contribute to the problem.

This same pathophysiologic process can affect other areas as well—including the pannus, as seen in this case. Since I had only ever encountered this problem in legs, I did a literature search. I found several references, all of which indicated that surgical removal (panniculectomy) was the best treatment. I could not find any information on the success rate of this surgery, but I did refer the patient back to the surgeon, who had made the correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a consequence of uncontrolled venous insufficiency that commonly manifests on lower extremities.

- ENV is a distinctly rare (though not unknown) problem when areas other than legs are affected.

- This patient’s condition is, in my opinion, beyond the reach of medical treatment. But in milder cases, approaches such as weight loss and use of diuretics have been tried with mixed success.

- The best treatment appears to be surgical removal, which is not without potential complications: risk for infection, pain, prolonged recovery time, and wound dehiscence; these issues were discussed thoroughly with the case patient.

A 60-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a longstanding complaint of a tender, irritated mass hanging from her lower abdomen. The patient says it started as a large fold in her lower abdomen but over the years has grown and become more pendulous. It is now large enough to interfere with normal activity, including walking.

Numerous providers, dermatologists included, have rendered diagnoses—most recently, hidradenitis suppurativa. The antibiotics prescribed for that diagnosis have not helped, however. Similarly, cultures performed on samples from draining sores on the mass’s posterior have failed to illuminate the situation, showing only mixed normal flora.

The patient’s primary care provider referred her to surgery for consideration of removal, or at least reduction, of the mass. The surgeon offered a presumptive diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the pannus and agreed to perform the surgery. But the patient’s primary care provider requested a second opinion from dermatology.

EXAMINATION

The edematous, pendulous mass is the size of a soccer ball and hangs down from its abdominal base. When the patient stands, the mass stretches almost to the level of her knees. The anterior surface is edematous but otherwise normal in appearance. The intertriginous surfaces of the lesion look entirely different, with multiple small, draining puncta and a few open comedones.

The body of the mass is quite indurated but is neither hot nor tender. There are no comedones or cysts in other intertriginous locations, as might be seen in hidradenitis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case involves a rare entity: vast lymphedema of the pannus leading to the formation of a pendulous mass so large that it filled the space between the patient’s legs, causing pain and discomfort. These findings are analogous to those seen in advanced venous insufficiency. Both manifestations share a name: elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. (Neither has anything to do with the more notorious cases of filarial elephantiasis seen in tropical locations.)

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the lower extremities involves striking skin changes: edema, along with extreme thickening, papularity, and roughness of the skin. These typically manifest downward from just below the knee. The condition represents the effects of late-stage chronic venous insufficiency, often worsened by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. Other causes of dependent lymphedema, such as congestive heart failure, can also contribute to the problem.

This same pathophysiologic process can affect other areas as well—including the pannus, as seen in this case. Since I had only ever encountered this problem in legs, I did a literature search. I found several references, all of which indicated that surgical removal (panniculectomy) was the best treatment. I could not find any information on the success rate of this surgery, but I did refer the patient back to the surgeon, who had made the correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a consequence of uncontrolled venous insufficiency that commonly manifests on lower extremities.

- ENV is a distinctly rare (though not unknown) problem when areas other than legs are affected.

- This patient’s condition is, in my opinion, beyond the reach of medical treatment. But in milder cases, approaches such as weight loss and use of diuretics have been tried with mixed success.

- The best treatment appears to be surgical removal, which is not without potential complications: risk for infection, pain, prolonged recovery time, and wound dehiscence; these issues were discussed thoroughly with the case patient.

Was Declining Treatment a Bad Idea?

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

Recognizing the Scale of the Problem

For more than 2 years, this 36-year-old woman has had a slightly itchy rash that waxes and wanes on her posterior neck. She has consulted several primary care providers and received multiple diagnoses, the most consistent of which has been fungal infection. However, despite use of a variety of antifungal creams (nystatin, clotrimazole, and combination clotrimazole/betamethasone), a 1-month course of oral terbinafine, and OTC tolnaftate, no improvement has occurred.

The patient asserts that she is otherwise in good health, with no joint pain or fever and no history of recent health crises. Family history is free of dermatologic complaints except for psoriasis in her father.

EXAMINATION

A pink plaque with white, fairly adherent scale covers most of the patient’s posterior neck/upper midline back. When a 3-mm section of scaling is peeled away, 2 tiny dots of pinpoint bleeding are immediately noted.

The rest of her scalp is free of any such changes, as are her elbows and knees. But a similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area, and 3 of 10 fingernails are mildly pitted.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis vulgaris (common psoriasis) affects around 3% of the white population in this country. That incidence almost doubles in northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Psoriasis is so common that you should expect to see it regularly; the important question is not “Will you see it?” but rather “Will you know it when you see it?” Sometimes the various clinical elements of psoriasis must be sought, and those dots connected, as this case demonstrates effectively.

For one thing, the nape of the neck is commonly affected, especially in women. It is pure speculation, but one imagines that the heat and sweat associated with longer hair might contribute to this predilection.

The pink color, whitish scale, and pinpoint bleeding (termed the Auspitz sign) all corroborate the diagnosis, as does the positive family history and nail pitting. The intergluteal involvement was the icing on the cake; this is seen in only 2 common conditions: psoriasis and seborrhea.

The lesson? Even though psoriasis is supposed to appear on elbows, knees, and other extensor surfaces, sometimes it breaks the rules. The posterior neck was the primary area of involvement in this case, but sometimes psoriasis is completely confined to the scalp or the palms. And, of course, there are different types of psoriasis, some of which bear scant resemblance to psoriasis vulgaris. That’s where biopsies and/or referrals prove to be useful.

It is true that this patient’s rash could have had a fungal origin. When in doubt, however, a punch or shave biopsy would most likely settle the matter, since the histologic picture is usually pathognomic.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is often be easy to diagnose—but just as often, it takes a bit of detective work.

- This “investigation” consists of looking for and asking about findings that could corroborate the diagnosis.

- The morphology of the neck lesion, as well as the Auspitz sign, nail pitting, intergluteal involvement, and family history in this case all served quite well to establish the diagnosis of psoriasis.

- It is helpful to remember how utterly common psoriasis is, affecting around 10,000,000 Americans.

For more than 2 years, this 36-year-old woman has had a slightly itchy rash that waxes and wanes on her posterior neck. She has consulted several primary care providers and received multiple diagnoses, the most consistent of which has been fungal infection. However, despite use of a variety of antifungal creams (nystatin, clotrimazole, and combination clotrimazole/betamethasone), a 1-month course of oral terbinafine, and OTC tolnaftate, no improvement has occurred.

The patient asserts that she is otherwise in good health, with no joint pain or fever and no history of recent health crises. Family history is free of dermatologic complaints except for psoriasis in her father.

EXAMINATION

A pink plaque with white, fairly adherent scale covers most of the patient’s posterior neck/upper midline back. When a 3-mm section of scaling is peeled away, 2 tiny dots of pinpoint bleeding are immediately noted.

The rest of her scalp is free of any such changes, as are her elbows and knees. But a similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area, and 3 of 10 fingernails are mildly pitted.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis vulgaris (common psoriasis) affects around 3% of the white population in this country. That incidence almost doubles in northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Psoriasis is so common that you should expect to see it regularly; the important question is not “Will you see it?” but rather “Will you know it when you see it?” Sometimes the various clinical elements of psoriasis must be sought, and those dots connected, as this case demonstrates effectively.

For one thing, the nape of the neck is commonly affected, especially in women. It is pure speculation, but one imagines that the heat and sweat associated with longer hair might contribute to this predilection.

The pink color, whitish scale, and pinpoint bleeding (termed the Auspitz sign) all corroborate the diagnosis, as does the positive family history and nail pitting. The intergluteal involvement was the icing on the cake; this is seen in only 2 common conditions: psoriasis and seborrhea.

The lesson? Even though psoriasis is supposed to appear on elbows, knees, and other extensor surfaces, sometimes it breaks the rules. The posterior neck was the primary area of involvement in this case, but sometimes psoriasis is completely confined to the scalp or the palms. And, of course, there are different types of psoriasis, some of which bear scant resemblance to psoriasis vulgaris. That’s where biopsies and/or referrals prove to be useful.

It is true that this patient’s rash could have had a fungal origin. When in doubt, however, a punch or shave biopsy would most likely settle the matter, since the histologic picture is usually pathognomic.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is often be easy to diagnose—but just as often, it takes a bit of detective work.

- This “investigation” consists of looking for and asking about findings that could corroborate the diagnosis.

- The morphology of the neck lesion, as well as the Auspitz sign, nail pitting, intergluteal involvement, and family history in this case all served quite well to establish the diagnosis of psoriasis.

- It is helpful to remember how utterly common psoriasis is, affecting around 10,000,000 Americans.